Abstract

Aim

This case–control study aimed to examine impairments in glucose metabolism in non-diabetic carriers of the mitochondrial mutation m.3243A>G by evaluating insulin secretion capacity and sensitivity.

Methods

Glucose metabolism was investigated in 23 non-diabetic m.3243A>G carriers and age-, sex- and BMI-matched healthy controls with an extended 4-h oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Insulin sensitivity index and acute insulin response were estimated on the basis of the OGTT. This was accompanied by examination of body composition by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), maximum aerobic capacity and a Recent Physical Activity Questionnaire (RPAQ).

Results

Fasting p-glucose, s-insulin and s-c-peptide levels did not differ between m.3243A>G carriers and controls. Insulin sensitivity index (BIGTT-S1) was significantly lower in the m.3243A>G carriers, but there was no difference in the acute insulin response between groups. P-lactate levels were higher in carriers throughout the OGTT. VO2max, but not BMI, waist and hip circumferences, lean and fat body mass%, MET or grip strength, was lower in mutation carriers. BIGTT-S1 remained lower in mutation carriers after adjustment for multiple confounding factors including VO2max in regression analyses.

Conclusions

Glucose metabolism in m.3243A>G carriers was characterized by reduced insulin sensitivity, which could represent the earliest phase in the pathogenesis of m.3243A>G-associated diabetes.

Keywords: monogenic diabetes, mitochondrial DNA point mutation m.3243A>G, mitochondrial dysfunction, insulin resistance

Introduction

Mitochondrial diabetes mellitus may be caused by mutations in nuclear DNA (nDNA) as well as in mitochondrial-encoded genes (mDNA) (1). The most common mitochondrial mutation, m.3243A>G, associates with maternally inherited diabetes and deafness (MIDD) (2, 3), which has a prevalence of 0.2–2% in diabetic populations (4, 5, 6, 7). Nearly 100% of m.3243A>G carriers develop impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) or overt diabetes at age 70 years (7). In addition to diabetes, m.3243A>G carriers may present with highly variable clinical phenotypes including mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) and progressive external ophthalmoplegia (PEO) (3). The variation in the clinical phenotypes is partly explained by different tissue mutation burdens, that is cells and tissues hold a mixture of both mutated (m.3243A>G) and WT genomes (8, 9), also called heteroplasmy (10). The heteroplasmy level contributes significantly to the severity of mitochondrial dysfunction at the cellular level (11, 12). In skeletal muscle, heteroplasmy is inversely correlated to oxidative capacity in patients with mitochondrial myopathy (13). Additionally, the level of heteroplasmy in blood and muscle is inversely correlated to age of diabetes debut (14).

It is debated whether the impaired glucose metabolism in m.3243A>G carriers is characterized by insulin resistance, insulin secretion defect or a combination. The nuclear gene encoded mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) is essential for transcription of mDNA, and mice with knockout of TFAM in pancreatic β-cells have a reduced glucose-stimulated insulin secretion followed by loss of β-cells (15). However, in mice with skeletal muscle-specific TFAM knockout, peripheral glucose disposal was increased and they did not develop diabetes (16). These findings do not support mitochondrial dysfunction in skeletal muscle tissue as a primary phenomenon in the development of insulin resistance.

Studies of the glucose metabolism in human carriers of m.3243A>G have shown conflicting results. Many of these studies were hampered by small numbers of participants due to the rarity of the disease. Insulin secretion defect has been a repeated finding in most of the previous studies of the glucose metabolism. Suzuki et al. (17) studied 10 non-DM and 14 DM m.3243A>G carriers and found a markedly reduced glucose-stimulated insulin secretion during an OGTT and lower 24-h urine c-peptide levels in carriers than in controls. The insulin secretion defect progressed from carriers with normal glucose tolerance (NGT) over carriers with IGT to carriers with DM (17). Two studies of 25 and 12 non-diabetic m.3243A>G carriers reported none or only subtle impairments of insulin response to an OGTT (7, 18). First- and second-phase insulin secretion was reduced in hyperglycemic clamp studies of two and seven m.3243A>G carriers (7, 19).

Fifteen m.3243A>G carriers with different stages of glucose intolerance were studied with both OGTT and hyperinsulinemic clamp. In these patients, both decreased insulin sensitivity and impaired β-cell function was demonstrated prior to development of overt diabetes (20). Insulin sensitivity was equally reduced in all m.3243A>G carriers while the insulin secretion defect progressed from non-diabetic over the newly diagnosed diabetic to the carriers with an average diabetes duration of 9.7 years (20). In the same group of subjects, insulin resistance was found in adipose tissue with decreased insulin-stimulated glucose uptake, blunted suppression of lipolysis and low adiponectin levels (21). Insulin resistance has also been reported in other studies, although only in mutation carriers with manifest diabetes, which suggests that insulin resistance could be caused by glucose toxicity rather than mitochondrial dysfunction (19, 22, 23). This is in contrast to a study of 12 diabetic carriers, which did not detect insulin resistance using the euglycemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamp (24). Increased gluconeogenesis related to elevated lactate levels has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of mitochondrial diabetes (23). In addition, insulin response to arginine showed normal values, indicating a preservation of the β-cell population despite impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (19).

A defect in insulin secretion is probably a major factor in the development and especially the progression of m.3243A>G-associated diabetes, but evidence also suggests that insulin resistance of skeletal muscle and adipose tissue and increased hepatic gluconeogenesis contribute to the development of diabetes. In most studies, insulin resistance was limited to subjects with manifest diabetes, raising the question of whether insulin resistance is caused by mitochondrial dysfunction or is a consequence of hyperglycemia. The aim of this study was to examine a group of m.3243A>G carriers with presumed NGT to identify early changes in glucose metabolism prior to the development of diabetes and evaluate insulin secretion and sensitivity.

Methods

Design, setting and participants

The participants in the study were recruited between February 2016 and August 2017 from a Danish cohort of m.3243A>G-positive subjects from 26 families. Ninety-five individuals were evaluated and 55 subjects were excluded because of previously diagnosed diabetes mellitus defined by a 2-h plasma glucose ≥11.1 mM after an oral glucose tolerance test (75 g glucose) or hemoglobin 1Ac (HbA1c) ≥48 mM (25). Pregnancy (n = 1) and treatment with medications known to influence the glucose metabolism were also exclusion criteria. The remaining 39 were invited to participate in the study and 23 accepted, while 16 declined participation.

Twenty-three healthy control subjects were recruited by advertising among hospital staff, blood donors and the general population. We received 68 responses and selected subjects that matched the mutation carriers on sex, age and BMI (±20% margin).

Information on lifestyle, comorbidities and treatment was retrieved by interviews and a structured questionnaire. All participants also completed a Recent Physical Activity Questionnaire (26, 27). Body weight was measured with participants wearing casual indoors clothing and barefoot to the nearest 0.1 kg on a Seca model 708 scale (Seca, Hamburg, Germany). Body height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm on a wall-mounted Harpenden stadiometer (Holtain Ltd., Crymich, UK). Examinations and scans were performed at Hospital of Southwest Jutland and Odense University Hospital.

All participants provided informed consent, and the study was performed according to the guidelines from the Declaration of Helsinki. The Regional Scientific Ethical Committees for Southern Denmark approved both investigations (ID S-20100112).

Oral glucose tolerance test

All individuals underwent an extended 75-g frequently sampled OGTT according to the BIGTT protocol, where the estimated insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion capacity were validated against an intravenous glucose tolerance test in non-DM individuals (28). After a 12-h overnight fast, venous blood samples were drawn at −20, −10 and 0 min before the OGTT and at 10, 30, 50, 60, 90, 105, 120, 140, 180 and 240 min from the start of the glucose load and stored at −80°C until analysis of p-glucose, p-lactate, s-insulin levels and s-c-peptide. Plasma glucose and plasma lactate were determined on ABL800 FLEX® (Radiometer Medical, Brønshøj, Denmark) and serum insulin, and c-peptide was measured on Cobas e411® (Roche) by electro-chemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA). Samples from mutations carriers and the matched control subjects were analyzed in pairs.

Biochemical analysis

Fasting venous blood samples taken before the OGTT between 08:15 and 08:40 h were stored at −80°C until measurement of lipids, electrolytes, p-liver enzymes and p-creatinine by Architect C16000 analyzer (Abbott Diagnostics), HbA1c by Tosoh G8 (Tosoh Bioscience, Inc. San Francisco, CA, USA) and hemoglobin by Sysmex XE 5000 (Sysmex Nordic, Copenhagen Denmark).

DXA scan

Whole-body fat mass and lean mass were measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (Hologic Discovery, Waltham, MA, USA).

Muscle strength test

Handgrip muscle strength test was evaluated by a JAMAR hydraulic hand dynamometer (Sammons Preston Rolyan, Bolingbrook, IL, USA), where the individual subject was given three attempts with the dominant hand and the best attempt was noted.

Maximal aerobic capacity

All participants completed a maximal workload bicycle test on an ergomedic exercise cycle (Monark 928e ErgometerCycle) to measure their maximal aerobic capacity (VO2max) (29).

Statistics

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.), median (interquartile range (IQR)), or numbers as appropriate. Normality was evaluated using probability plots. m.3243A>G-positive subjects and controls were compared using chi-square test for categorical variables and unpaired Student’s t test or Mann–Whitney U test for normally distributed or nonparametric data, respectively. Data is presented in tables with mean ± s.d. or median and IQR for normally distributed or nonparametric data, respectively.

The OGTT data are presented in graphs of the time-dependent changes in concentrations of p-glucose, p-lactate, p-insulin and s-c-peptide with confidence intervals (CI). Area under the curve (AUC) was calculated for 0–30 min, 0–180 min and 0–240 min. Insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion capacity were estimated by two methods. We used The Homeostasis Model Assessment (HOMA) to estimate insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and β-cell function (HOMA-β) (30). Furthermore, we used the equations from the BIGTT study (28) to calculate the insulin sensitivity index (BIGTT-S1) and acute insulin response index (BIGTT-AIR). Differences between carriers and controls were compared for each measurement by unpaired Student’s t test or Mann–Whitney U test for normally distributed or nonparametric data, respectively. Multiple regression analyses were performed to assess the association between VO2max and BIGTT-S1, BIGTT-AIR, HOMA-IR and HOMA-β with and without adjustment for potential confounders. The first regression model included mutation status (m.3243A>G vs wild type) and VO2max as independent variables, and the second model included mutation status, VO2max, BMI, age and sex as independent variables. Logarithmic transformation was applied if variables were not normally distributed.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA statistical package version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

General characteristics, body composition, physical activity, muscle strength and aerobic capacity of study participants

Characteristics of m.3243A>G subjects and controls are presented in Table 1. Gender, age, body weight, BMI, blood pressure, waist and hip circumference were similar among mutation carriers and controls. However, mean body height was 7 cm lower in mutation carriers. Furthermore, mean pulse rate was 8/min higher and, mean aerobic capacity was 8.6 mL/kg/min lower in carriers.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics, physical examination, aerobic capacity, muscle strength, Recent Physical Activity Questionnaire, biochemistry and body composition.

| Category | Variables | m.3243A>G | Controls | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic characteristics | Number (no.) | 23 | 23 | |

| Sex (Female/Male) | 10/13 | 10/13 | ||

| Age (years) | 30 (24–43) | 32 (27–46) | 0.67 | |

| Physical examination | Weight (kg) | 70 ± 19 | 77 ± 13 | 0.15 |

| Height (m) | 2 ± 0.1 | 2 ± 0.1 | 0.01 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24 ± 5 | 24 ± 3 | 0.09 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 126 ± 14 | 120 ± 10 | 0.09 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 77 ± 7 | 75 ± 8 | 0.51 | |

| Pulse (1/min) | 74 ± 11 | 66 ± 10 | 0.01 | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 82 (78-98) | 86 (79-91) | 0.58 | |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 99 ± 9 | 103 ± 7 | 0.10 | |

| Aerobic capacity | VO2max (mL/kg/min) | 28 ± 8 | 36 ± 8 | <0.01 |

| Muscle strength | Handgrip muscle strength (kg) | 43 ± 14 | 46 ± 11 | 0.57 |

| Recent Physical Activity Questionnaire (RPAQ) | Total reported duration (hours) of activity times intensity (MET) (METhrs/day) | 20 (15–23) | 19 (14–26) | 0.62 |

| Total reported plus unaccounted duration hours) times intensity (MET) (METhrs/day) | 27 (23–32) | 27 (24–34) | 0.52 | |

| Total activity energy expenditure discounting resting (net METhrs/day) | 10 (6–15) | 10 (7–18) | 0.56 | |

| Sedentary behavior energy expenditure (METhrs/day) | 4.3 (2.8–9.1) | 4.0 (2.0–9.4) | 0.68 | |

| Light intensity energy expenditure (METhrs/day) | 0.0 (0.0–1.4) | 0.1 (0.0–8.5) | 0.24 | |

| Moderate intensity energy expenditure (METhrs/day) | 4.9 (2.2–9.7) | 4.2 (2.6–9.8) | 0.99 | |

| Vigorous intensity energy expenditure (METhrs/day) | 0.2 (0.0–2.9) | 1.3 (0.3–3.9) | 0.17 | |

| Biochemistry | HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 36 ± 4 | 34 ± 3 | 0.08 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.5 ± 1.0 | 4.6 ± 0.8 | 0.80 | |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 0.21 | |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 0.82 | |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.28 | |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 71 (65-84) | 77 (64-86) | 0.58 | |

| DXA | Whole-body fat mass (kg) | 21 ± 8 | 21 ± 7 | 0.99 |

| Whole-body lean mass (kg) | 50 ± 13 | 57 ± 11 | 0.05 | |

| Whole-body mass (kg) | 71 ± 18 | 78 ± 13 | 0.13 | |

| Total fat mass pct. (%) | 30 ± 8 | 27 ± 8 | 0.30 | |

| Total lean mass pct. (%) | 70 ± 8 | 73 ± 8 | 0.30 |

Mean ± s.d.; Median (IQR).

Handgrip muscle strength, all RPAQ variables and all biochemistry variables did not differ between groups. The DXA scans showed lower lean body mass in the m.3243A>G carriers (P value 0.05), but the body composition represented by total body fat and lean body mass percentage did not differ.

Oral glucose tolerance test

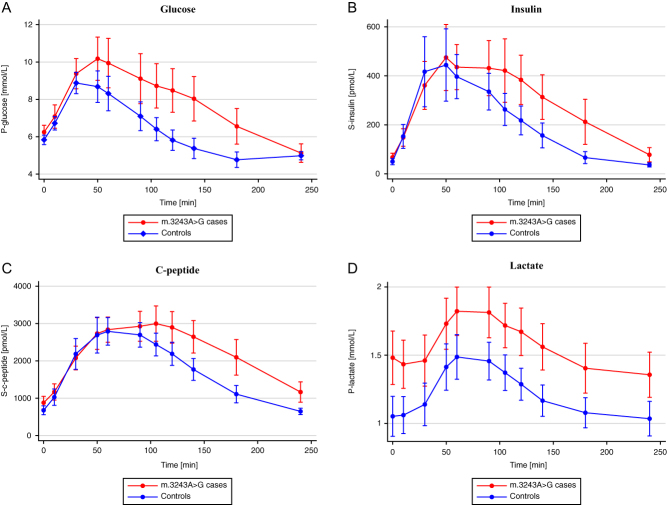

Glucose levels in the m.3243A>G carriers were elevated compared to the control group at 50–180 min and p-insulin and s-c-peptide levels in m.3243A>G carriers at 105–240 min and 120–240 min, respectively (Fig. 1A, B, C and Table 2). Furthermore, we found that p-lactate levels were higher in the m.3243A>G group throughout the test with a parallel, but still significant, increase toward a maximum at 60–90 min (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

(A) Plasma glucose levels (mmol/L) during OGTT. (B) Serum insulin levels (pmol/L) during OGTT. (C) Serum c-peptide levels (pmol/L) during OGTT. (D) Plasma lactate levels (mmol/L) during OGTT. M.3243A>G cases are red and controls are blue.

Table 2.

Oral glucose tolerance test.

| Time (min) | m.3243A>G | Controls | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose (mmol/L) | Insulin (pmol/L) | c-peptide (pmol/L) | Lactate (mmol/L) | Glucose (mmol/L) | Insulin (pmol/L) | c-peptide (pmol/L) | Lactate (mmol/L) | |

| 0 | 6.2 ± 0.9 | 67.3 ± 41.3 | 880.3 ± 416.2 | 1.5a ± 0.5 | 5.8 ± 0.6 | 50.2 ± 31.3 | 667.4 ± 291.0 | 1.1 ± 0.4 |

| 10 | 7.1 ± 1.5 | 148.4 ± 87.0 | 1168.7 ± 530.3 | 1.4a ± 0.4 | 6.7 ± 0.9 | 152.9 ± 119.0 | 1029.0 ± 532.4 | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

| 30 | 9.4 ± 2.0 | 360.9 ± 239.7 | 2078.7 ± 778.2 | 1.5a ± 0.5 | 8.9 ± 1.4 | 416.9 ± 349.6 | 2185.8 ± 1013.5 | 1.1 ± 0.4 |

| 50 | 10.2a ± 2.8 | 474.9 ± 330.1 | 2732.8 ± 1042.1 | 1.7a ± 0.5 | 8.7 ± 2.1 | 444.1 ± 361.0 | 2690.8 ± 1177.1 | 1.4 ± 0.4 |

| 60 | 9.9a ± 3.2 | 435.7 ± 224.7 | 2836.7 ± 824.9 | 1.8a ± 0.4 | 8.3 ± 2.3 | 396.8 ± 220.0 | 2791.0 ± 901.6 | 1.5 ± 0.4 |

| 90 | 9.1a ± 3.3 | 431.5 ± 274.8 | 2926.9 ± 978.6 | 1.8a ± 0.5 | 7.1 ± 1.9 | 335.4 ± 182.8 | 2696.3 ± 800.5 | 1.5 ± 0.3 |

| 105 | 8.7a ± 2.9 | 421.5a ± 316.7 | 2997.9 ± 1157.1 | 1.7a ± 0.4 | 6.4 ± 1.5 | 262.9 ± 160.3 | 2439.3 ± 744.8 | 1.4 ± 0.3 |

| 120 | 8.5a ± 2.9 | 383.8a ± 246.5 | 2897.3a ± 1033.8 | 1.7a ± 0.4 | 5.8 ± 1.3 | 218.0 ± 143.7 | 2189.3 ± 760.2 | 1.3 ± 0.3 |

| 140 | 8.0a ± 2.9 | 313.3a ± 222.3 | 2645.9a ± 1066.6 | 1.6a ± 0.4 | 5.4 ± 1.3 | 156.7 ± 124.2 | 1771.0 ± 718.2 | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| 180 | 6.6a ± 2.3 | 212.4a ± 224.8 | 2096.1a ± 1168.5 | 1.4a ± 0.4 | 4.8 ± 1.0 | 66.4 ± 59.7 | 1110.5 ± 567.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

| 240 | 5.1 ± 1.2 | 78.0a ± 71.0 | 1166.1a ± 665.6 | 1.4a ± 0.4 | 5.0 ± 0.5 | 36.4 ± 20.7 | 648.1 ± 206.9 | 1.0 ± 0.3 |

Mean ± s.d.

aSignificantly difference between m.3243A>G and controls (P < 0.05).

Insulin secretion and sensitivity index

All the insulin secretion indexes of BIGTT-AIR, HOMA-β, ∆II(0-30), ∆II(0-180) and ∆II(0-240) showed no difference between groups. The BIGTT-S1 index showed significantly lower insulin sensitivity in the m.3243A>G group, while HOMA-IR did not differ significantly between the groups.

The participants were classified according to the 2-h glucose level as NGT, IGT or DM and we found that the majority of the m.3243A>G carriers were either IGT (n = 12) or had diabetic 2-h values (n = 3) despite the fact that everyone had HbA1c <48 mmol/mol and normal fasting p-glucose (Tables 1 and 3).

Table 3.

Insulin secretion and sensitivity index.

| m.3243A>G | Controls | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BIGTT-S1 | 4.0 (3.0–9.9) | 9.5 (5.7–11.5) | 0.03 |

| BIGTT-AIR-full | 8519.7 (6615.9–13885.7) | 7184.0 (6921.3–10471.6) | 0.41 |

| BIGTT-AIR-0-30-120 | 1498.8 (1013.4–2147.5) | 1561.2 (1207.8–1915.2) | 0.59 |

| BIGTT-AIR-0-60-120 | 1755.1 (1050.0–2456.6) | 1682.1 (1103.7–1929.8) | 0.65 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.2 (1.4–4.0) | 1.5 (1.2–2.1) | 0.08 |

| HOMA-β | 60.6 (37.1–103.8) | 55.5 (38.4–71.1) | 0.55 |

| Matsuda-S | 4.6 ± 2.6 | 5.7 ± 2.2 | 0.14 |

| ∆II (0-30 min) | 1.3 (1.1–2.1) | 1.4 (1.2–1.8) | 0.45 |

| ∆II (0-180 min) | 1.7 (1.4–2.7) | 1.8 (1.6–2.4) | 0.83 |

| ∆II (0-240 min) | 1.8 (1.1–2.5) | 1.6 (1.4–2.1) | 0.89 |

| NGT/IGT/DM | 8/12/3 | 18/5/0 | <0.01 |

Mean ± s.d.; Median (IQR).

Association between VO2max and insulin secretion and sensitivity index

Carrier status was not associated with insulin secretion capacity or sensitivity after adjustment for VO2max, which associated with BIGTT-S1 and HOMA-IR before but not after adjustment for confounders (Table 4). However, BIGTT-S1 remained associated with carrier status after adjustment for both VO2max and measures of confounders.

Table 4.

Regression analysis of insulin sensitivity indices.

| Model 1 – coefficient | Model 2 – coefficient | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Log(BIGTT-S1) | m.3243A>G (+/−) | 0.20 | 0.37a |

| VO2max (+/−) | 0.04a | 0.02 | |

| Log(BIGTT-AIR-full) | m.3243A>G (+/−) | 0.04 | −0.01 |

| VO2max (+/−) | −0.02 | −0.01 | |

| Log(BIGTT-AIR-0-30-120) | m.3243A>G (+/−) | 0.21 | 0.25 |

| VO2max (+/−) | −0.01 | −0.02 | |

| Log(BIGTT-AIR-0-60-120) | m.3243A>G (+/−) | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| VO2max (+/−) | −0.00 | −0.01 | |

| Log(HOMA-IR) | m.3243A>G (+/−) | −0.07 | −0.14 |

| VO2max (+/−) | −0.03a | −0.02 | |

| Log(HOMA-β) | m.3243A>G (+/−) | 0.04 | 0.09 |

| VO2max (+/−) | −0.02 | −0.02 |

Model 1: m.3243A>G status and VO2max as independent variables. Model 2: m.3243A>G status, VO2max, BMI, age and sex as independent variables.

aP < 0.05.

Discussion

The present study was performed to study the glucose metabolism in carriers of m.3243A>G without diagnosed diabetes at the time of recruitment with the aim to identify potential early impairment of glucose metabolism as a pre-stage for diabetes. All mutation carriers had normal fasting p-glucose levels and HbA1c values, but OGTT revealed that 12 participants exhibited IGT and three had diabetic 2-h values. The OGTT examination demonstrated a normal first phase insulin secretion assessed by ∆II (0–30 min) and c-peptide values, but this was followed by elevated levels of both p-glucose and s-insulin in m.3243A>G carriers. Insulin secretion indexes were not affected in the m.3243A>G carriers, but we found lower insulin sensitivity measured by BIGTT-S1 in mutation carriers and the same tendency was seen in HOMA-IR, although not statistically significant (P = 0.077).

The major finding of the OGTT in this study is the combination of elevated p-glucose and s-insulin levels along with lower BIGTT-S1 suggesting that insulin sensitivity and not insulin secretion is reduced in the m.3243A>G carriers prior to development of overt diabetes. In previous studies of non-diabetic m.3243A>G carriers, the existence of insulin resistance has been disputed. In 11 non-diabetic m.3243A>g carriers, the main finding was isolated higher p-glucose levels in an OGTT, while insulin levels were similar to the control group (2). A study of 10 NGT and 2 IGT mutation carriers demonstrated elevated glucose and insulin levels in an OGTT similar to the present study (18). Additionally, there was a non-significant trend toward reduced insulin sensitivity that was compensated by increased glucose effectiveness in an IVGTT (18). Insulin secretion defect has been demonstrated in non-DM m.3243A>G carriers with a progressive pattern from subjects with NGT toward subjects with manifest DM (17). This progression of failing β-cell function was corroborated by Lindroos and colleagues (20) in a study of both DM (n = 10) and non-DM (n = 5) m.3243A>G carriers. However, these investigators also demonstrated insulin resistance in muscle and fat cells (20, 21), suggesting that DM may develop due to both insulin resistance and impaired insulin secretion.

The above-mentioned studies were conducted in different study populations with varying proportions of m.3243A>G subjects with DM, IGT and NGT. In addition, low statistical power could explain the diverging results. Our study provides additional evidence for insulin resistance in the early stages of the development of mitochondrial diabetes. At a cellular level mitochondrial dysfunction might be linked to insulin resistance by increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, especially H2O2 (31, 32), and the m.3243A>G mutation is associated with increased ROS production (33).

Impaired fitness level as observed in mutation carriers could have independent effects on insulin sensitivity. Importantly, previous training studies have not consistently reported a correlation between VO2max and insulin mediated glucose disposal (34). The most important factor determining VO2max is cardiac output, which accounts for 70–85% of the inter-individual difference in VO2max and correlates with height (35, 36). Skeletal muscle oxidative defects may impair exercise capacity in patients with mitochondrial myopathy such as the mt.3243 mutation carriers (13, 37). In addition, mitochondrial dysfunction may impair the function of the heart muscle and subsequently contribute to lower cardiac output mutation carriers (38). In addition, mutation carriers in our study were shorter than the controls, which could lead to lower cardiac output due to presumed smaller heart volume. Accordingly, the difference in VO2max could, at least in part, be explained by difference in height and possibly effects of the m.3243A>G mutation on skeletal and heart muscle.

The elevated lactate level in the m.3243A>G was an expected finding and could be a contributing cause of the insulin resistance as fasting lactate levels have been shown to be inversely correlated with glucose uptake in the left ventricle of the heart during an euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp in m.3243A>G carriers (39).

Furthermore, glycolysis and insulin signaling are suppressed in red fibers of skeletal muscle of rats infused with lactate during a hyperinsulinemic–euglycemic clamp (40). Mice studies show that circulating lactate is the predominant source of fuel for the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, which means that glycolysis and the TCA cycle are essentially uncoupled (41). Under normal conditions, glycolysis consumes nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) and relies on the TCA cycle in the mitochondria to replenish NAD+ (42). Therefore, mitochondrial dysfunction and elevated lactate may inhibit glycolysis by elevated lactate and insufficient NAD+, which may impair glucose uptake and result in insulin resistance. Furthermore, elevated lactate is associated with increased gluconeogenesis in both DM and non-DM m.3243A>G carriers, which adds to the hyperglycemic state (23).

The hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp is considered the gold standard for assessment of insulin sensitivity with the frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test (FSIVGTT) as an alternative (43). The participants in the present study were investigated using the OGTT, which has been shown to correlate with the FSIVGTT (28). Contrary to clamp, the OGTT provides a measure of the insulin response under physiological conditions including the incretin effect and incorporates both peripheral and hepatic insulin resistance (43). The OGTT is less resource demanding than clamp and FSIVGTT, but introduces more variability due to variation in the absorption of glucose from the gastrointestinal tract (43). Muscle biopsies were not collected in the investigation, effectively excluding the possibility to assess insulin signaling and the degree of mitochondrial dysfunction at the cellular level. Furthermore, cases and controls were well matched with regard to BMI but not height, potentially representing a limitation as discussed above. While control subjects and cases reported a similar level of physical activity, the fitness level was lower in cases.

In conclusion, our results indicate that insulin resistance is an early defect prior to development of overt diabetes in m.3243A>G carriers. Furthermore, we found elevated p-lactate levels during the entire OGTT. Whether this could aggravate the insulin resistance in m.3243A>G carriers remains to be determined. Further research into the underlying intracellular mechanisms causing insulin resistance in patients with primary mitochondrial dysfunction is needed and should, if possible, include larger series and longitudinal studies. Such data could also increase the understanding of insulin resistance in type 2 diabetics.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

This research project was supported by grants from Region of Southern Denmark, The A.P. Møller and Chastine Mc-Kinney Møller Foundation for General Purposes and The Karola Jørgensen Research Foundation.

References

- 1.Schaefer AM, Walker M, Turnbull DM, Taylor RW. Endocrine disorders in mitochondrial disease. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 2013. 379 . ( 10.1016/j.mce.2013.06.004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van den Ouweland JM, Lemkes HH, Ruitenbeek W, Sandkuijl LA, de Vijlder MF, Struyvenberg PA, van de Kamp JJ, Maassen JA. Mutation in mitochondrial tRNA(Leu)(UUR) gene in a large pedigree with maternally transmitted type II diabetes mellitus and deafness. Nature Genetics 1992. 1 . ( 10.1038/ng0892-368) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy R, Turnbull DM, Walker M, Hattersley AT. Clinical features, diagnosis and management of maternally inherited diabetes and deafness (MIDD) associated with the 3243A>G mitochondrial point mutation. Diabetic Medicine 2008. 25 . ( 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02359.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vionnet N, Passa P, Froguel P. Prevalence of mitochondrial gene mutations in families with diabetes mellitus. Lancet 1993. 342 . ( 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92792-R) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katagiri H, Asano T, Ishihara H, Inukai K, Anai M, Yamanouchi T, Tsukuda K, Kikuchi M, Kitaoka H, Ohsawa N. Mitochondrial diabetes mellitus: prevalence and clinical characterization of diabetes due to mitochondrial tRNA(Leu(UUR)) gene mutation in Japanese patients. Diabetologia 1994. 37 . ( 10.1007/s001250050139) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saker PJ, Hattersley AT, Barrow B, Hammersley MS, Horton V, Gillmer MD, Turner RC. UKPDS 21: low prevalence of the mitochondrial transfer RNA gene (tRNA(Leu(UUR))) mutation at position 3243bp in UK Caucasian type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetic Medicine 1997. 14 . () [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maassen JA, ’T Hart LM, Van Essen E, Heine RJ, Nijpels G, Jahangir Tafrechi RS, Raap AK, Janssen GM, Lemkes HH. Mitochondrial diabetes: molecular mechanisms and clinical presentation. Diabetes 2004. 53 (Supplement 1) S103–S109. ( 10.2337/diabetes.53.2007.s103) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robin ED, Wong R. Mitochondrial DNA molecules and virtual number of mitochondria per cell in mammalian cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology 1988. 136 . ( 10.1002/jcp.1041360316) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satoh M, Kuroiwa T. Organization of multiple nucleoids and DNA molecules in mitochondria of a human cell. Experimental Cell Research 1991. 196 . ( 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90467-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holt IJ, Harding AE, Petty RK, Morgan-Hughes JA. A new mitochondrial disease associated with mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy. American Journal of Human Genetics 1990. 46 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunbar DR, Moonie PA, Jacobs HT, Holt IJ. Different cellular backgrounds confer a marked advantage to either mutant or wild-type mitochondrial genomes. PNAS 1995. 92 . ( 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6562) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flierl A, Reichmann H, Seibel P. Pathophysiology of the MELAS 3243 transition mutation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1997. 272 . ( 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27189) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeppesen TD, Schwartz M, Olsen DB, Vissing J. Oxidative capacity correlates with muscle mutation load in mitochondrial myopathy. Annals of Neurology 2003. 54 . ( 10.1002/ana.10594) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frederiksen AL, Jeppesen TD, Vissing J, Schwartz M, Kyvik KO, Schmitz O, Poulsen PL, Andersen PH. High prevalence of impaired glucose homeostasis and myopathy in asymptomatic and oligosymptomatic 3243A>G mitochondrial DNA mutation-positive subjects. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2009. 94 . ( 10.1210/jc.2009-0235) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva JP, Kohler M, Graff C, Oldfors A, Magnuson MA, Berggren PO, Larsson NG. Impaired insulin secretion and beta-cell loss in tissue-specific knockout mice with mitochondrial diabetes. Nature Genetics 2000. 26 . ( 10.1038/81649) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wredenberg A, Freyer C, Sandstrom ME, Katz A, Wibom R, Westerblad H, Larsson NG. Respiratory chain dysfunction in skeletal muscle does not cause insulin resistance. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2006. 350 . ( 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki S, Hinokio Y, Hirai S, Onoda M, Matsumoto M, Ohtomo M, Kawasaki H, Satoh Y, Akai H, Abe K. Pancreatic beta-cell secretory defect associated with mitochondrial point mutation of the tRNA(LEU(UUR)) gene: a study in seven families with mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS). Diabetologia 1994. 37 . ( 10.1007/BF00404339) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmes-Walker DJ, Ward GM, Boyages SC. Insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity are normal in non-diabetic subjects from maternal inheritance diabetes and deafness families. Diabetic Medicine 2001. 18 . ( 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2001.00472.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Velho G, Byrne MM, Clement K, Sturis J, Pueyo ME, Blanche H, Vionnet N, Fiet J, Passa P, Robert JJ, et al. Clinical phenotypes, insulin secretion, and insulin sensitivity in kindreds with maternally inherited diabetes and deafness due to mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) gene mutation. Diabetes 1996. 45 . ( 10.2337/diab.45.4.478) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindroos MM, Majamaa K, Tura A, Mari A, Kalliokoski KK, Taittonen MT, Iozzo P, Nuutila P.m.3243A>G mutation in mitochondrial DNA leads to decreased insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle and to progressive beta-cell dysfunction. Diabetes 2009. 58 . ( 10.2337/db08-0981) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindroos MM, Borra R, Mononen N, Lehtimaki T, Virtanen KA, Lepomaki V, Guiducci L, Iozzo P, Majamaa K, Nuutila P. Mitochondrial diabetes is associated with insulin resistance in subcutaneous adipose tissue but not with increased liver fat content. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 2011. 34 . ( 10.1007/s10545-011-9338-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kishimoto M, Hashiramoto M, Araki S, Ishida Y, Kazumi T, Kanda E, Kasuga M. Diabetes mellitus carrying a mutation in the mitochondrial tRNA(Leu(UUR)) gene. Diabetologia 1995. 38 . ( 10.1007/BF00400094) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Hattab AW, Emrick LT, Hsu JW, Chanprasert S, Jahoor F, Scaglia F, Craigen WJ. Glucose metabolism derangements in adults with the MELAS m.3243A>G mutation. Mitochondrion 2014. 18 . ( 10.1016/j.mito.2014.07.008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki Y, Iizuka T, Kobayashi T, Nishikawa T, Atsumi Y, Kadowaki T, Oka Y, Kadowaki H, Taniyama M, Hosokawa K, et al. Diabetes mellitus associated with the 3243 mitochondrial tRNA(Leu)(UUR) mutation: insulin secretion and sensitivity. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental 1997. 46 . ( 10.1016/S0026-0495(97)90272-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. Definition and Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus and Intermediate Hyperglycemia – Report of a WHO/IDF Consultation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Besson H, Brage S, Jakes RW, Ekelund U, Wareham NJ. Estimating physical activity energy expenditure, sedentary time, and physical activity intensity by self-report in adults. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2010. 91 . ( 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28432) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golubic R, May AM, Benjaminsen Borch K, Overvad K, Charles MA, Diaz MJ, Amiano P, Palli D, Valanou E, Vigl M, et al. Validity of electronically administered recent physical activity questionnaire (RPAQ) in ten European countries. PLoS ONE 2014. 9 e92829 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0092829) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansen T, Drivsholm T, Urhammer SA, Palacios RT, Volund A, Borch-Johnsen K, Pedersen O. The BIGTT test: a novel test for simultaneous measurement of pancreatic beta-cell function, insulin sensitivity, and glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care 2007. 30 . ( 10.2337/dc06-1240) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersen LB. A maximal cycle exercise protocol to predict maximal oxygen uptake. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 1995. 5 . ( 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1995.tb00027.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 1985. 28 . ( 10.1007/BF00280883) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoehn KL, Salmon AB, Hohnen-Behrens C, Turner N, Hoy AJ, Maghzal GJ, Stocker R, Van Remmen H, Kraegen EW, Cooney GJ, et al. Insulin resistance is a cellular antioxidant defense mechanism. PNAS 2009. 106 . ( 10.1073/pnas.0902380106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rudich A, Tirosh A, Potashnik R, Hemi R, Kanety H, Bashan N. Prolonged oxidative stress impairs insulin-induced GLUT4 translocation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Diabetes 1998. 47 . ( 10.2337/diabetes.47.10.1562) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J, Zhou K, Meng X, Wu Q, Li S, Liu Y, Wang J. Increased ROS generation and SOD activity in heteroplasmic tissues of transmitochondrial mice with A3243G mitochondrial DNA mutation. Genetics and Molecular Research 2008. 7 . ( 10.4238/vol7-4gmr480) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dela F. On the influence of physical training on glucose homeostasis. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica: Supplementum 1996. 635 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.di Prampero PE. Metabolic and circulatory limitations to VO2 max at the whole animal level. Journal of Experimental Biology 1985. 115 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rutenfranz J, Macek M, Lange Andersen K, Bell RD, Vavra J, Radvansky J, Klimmer F, Kylian H. The relationship between changing body height and growth related changes in maximal aerobic power. European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology 1990. 60 . ( 10.1007/BF00379397) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taivassalo T, Jensen TD, Kennaway N, DiMauro S, Vissing J, Haller RG. The spectrum of exercise tolerance in mitochondrial myopathies: a study of 40 patients. Brain 2003. 126 . ( 10.1093/brain/awg028) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Majamaa-Voltti K, Peuhkurinen K, Kortelainen ML, Hassinen IE, Majamaa K. Cardiac abnormalities in patients with mitochondrial DNA mutation 3243A>G. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 2002. 2 12 ( 10.1186/1471-2261-2-12) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindroos MM, Parkka JP, Taittonen MT, Iozzo P, Karppa M, Hassinen IE, Knuuti J, Nuutila P, Majamaa K. Myocardial glucose uptake in patients with the m.3243A>G mutation in mitochondrial DNA. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 2015. 39 . ( 10.1007/s10545-015-9865-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi CS, Kim YB, Lee FN, Zabolotny JM, Kahn BB, Youn JH. Lactate induces insulin resistance in skeletal muscle by suppressing glycolysis and impairing insulin signaling. American Journal of Physiology: Endocrinology and Metabolism 2002. 283 E233–E240. ( 10.1152/ajpendo.00557.2001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hui S, Ghergurovich JM, Morscher RJ, Jang C, Teng X, Lu W, Esparza LA, Reya T, Le Zhan, Yanxiang Guo J, et al. Glucose feeds the TCA cycle via circulating lactate. Nature 2017. 551 . ( 10.1038/nature24057) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berhane F, Fite A, Daboul N, Al-Janabi W, Msallaty Z, Caruso M, Lewis MK, Yi Z, Diamond MP, Abou-Samra AB, et al. Plasma lactate levels increase during hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp and oral glucose tolerance test. Journal of Diabetes Research 2015. 2015 102054 ( 10.1155/2015/102054) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borai A, Livingstone C, Kaddam I, Ferns G. Selection of the appropriate method for the assessment of insulin resistance. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2011. 11 158 ( 10.1186/1471-2288-11-158) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a