Abstract

Background

Many countries lack sufficient medical doctors to provide safe and affordable surgical and emergency obstetric care. Task‐sharing with associate clinicians (ACs) has been suggested to fill this gap. The aim of this study was to assess maternal and neonatal outcomes of caesarean sections performed by ACs and doctors.

Methods

All nine hospitals in Sierra Leone where both ACs and doctors performed caesarean sections were included in this prospective observational multicentre non‐inferiority study. Patients undergoing caesarean section were followed for 30 days. The primary outcome was maternal mortality, and secondary outcomes were perinatal events and maternal morbidity.

Results

Between October 2016 and May 2017, 1282 patients were enrolled in the study. In total, 1161 patients (90·6 per cent) were followed up with a home visit at 30 days. Data for 1274 caesarean sections were analysed, 443 performed by ACs and 831 by doctors. Twin pregnancies were more frequently treated by ACs, whereas doctors performed a higher proportion of operations outside office hours. There was one maternal death in the AC group and 15 in the doctor group (crude odds ratio (OR) 0·12, 90 per cent confidence interval 0·01 to 0·67). There were fewer stillbirths in the AC group (OR 0·74, 0·56 to 0·98), but patients were readmitted twice as often (OR 2·17, 1·08 to 4·42).

Conclusion

Caesarean sections performed by ACs are not inferior to those undertaken by doctors. Task‐sharing can be a safe strategy to improve access to emergency surgical care in areas where there is a shortage of doctors.

Introduction

Caesarean section is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures worldwide1, 2. Performed in a timely manner, a skilled operator can save the life and well‐being of both mother and child. Together with laparotomies and management of open fractures, the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery3 identified caesarean section as one of the bellwether procedures, an indicator set for access to surgery. This underlines that obstetric surgery, including caesarean section, is an integrated part of the emerging field of global surgery4.

Many countries today lack sufficient medical doctors to provide safe and affordable surgical and emergency obstetric care. The density of specialist surgical workforce per 100 000 population5 is now therefore included by the World Bank in the World Development Indicators6. The 2015 World Health Assembly7 resolution on strengthening emergency surgical care as a component of universal health coverage suggested task‐sharing as a strategy to optimize the efforts of the existing health workforce. Task‐sharing has been particularly recommended for obstetric procedures, including caesarean section, in areas where surgical providers are scarce8. A meta‐analysis9 of observational, mainly retrospective studies comparing in‐hospital outcomes of more than 16 000 caesarean sections by associate clinicians (ACs) and doctors revealed no significant difference in maternal and perinatal mortality rates. However, many are still unwilling to dispense with a medical qualification for the provision of all surgical care, and there is a widespread concern that any access gains from shifting surgical tasks to ACs may come at the expense of quality10.

Sierra Leone has an estimated caesarean section rate of less than 2·5 per cent11; the maternal mortality rate of 1360 per 100 000 live births is considered the highest in the world12. Lack of human resources is one of the main contributing factors, with 2·7 surgical providers per 100 000 population13 including specialist doctors, non‐specialist doctors and ACs. To increase access to emergency obstetric and surgical services, the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation initiated a surgical task‐sharing training programme. ACs are trained to manage basic emergency surgical and obstetric conditions, including surgery such as caesarean section14. Community Health Officers and non‐specialist doctors with a minimum of 2 years of work experience can apply for this 2‐year training. The aim of this study was to compare maternal and neonatal outcomes for caesarean section performed by ACs and doctors in Sierra Leone.

Methods

This was a prospective observational multicentre non‐inferiority study of women who underwent caesarean section, including laparotomy for uterine rupture. All hospitals in Sierra Leone where both ACs trained in surgery and doctors were performing caesarean section at the start of the study interval were invited to participate in the study. Women who had caesarean sections done by either an AC or doctor as the primary surgical provider were eligible for inclusion. Patients were excluded if the fetus weighed less than 500 g or if essential data were missing. After oral explanation of the study, written consent was obtained either before, or as soon as possible after, the procedure. The study protocol (Appendix S1, supporting information) was approved by the Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review Committee and the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics in central Norway (ethical clearance number 2016/1163), and registered at the International Clinical Trial Registry (ISRCTN16157971).

Data collection

In each hospital, anaesthesia team members were trained to enrol patients in the study and to collect the in‐hospital data. The primary investigator collected and reviewed the data by undertaking hospital visits at 1–3‐week intervals, at which time the anaesthesia nurses were also mentored in enrolment and data collection. The data were entered into a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA) database on location. Missing or inconsistent data were supplemented from operation logbooks or patient files. Financial incentives were given to the anaesthesia nurses based on the number of patients included in the study.

Follow‐up home visits were done from 30 days after the caesarean section by one of four trained research nurses, who also assisted the anaesthesia team members with the collection of in‐hospital data. The research nurses were supervised by the primary investigator biweekly. During the home visits, women received an incentive in the form of a health promotion package with basic sanitary items. In‐hospital outcome data were validated during the follow‐up home visits. For patients lost to follow‐up, only the data collected during hospital admission were analysed.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was perioperative maternal mortality, defined as maternal death during caesarean section or within 30 days after the operation. Perioperative maternal mortality was subdivided into intraoperative death, in‐hospital death and death after discharge.

Secondary outcomes were perinatal events and maternal morbidity parameters. Perinatal events included stillbirth, perinatal death and neonatal death. Stillbirth was classified as macerated where the fetus showed skin and soft tissue changes suggesting death occurred before the start of the delivery, and fresh where the fetus lacked such skin changes15. Neonatal deaths were divided into early (within 7 days after delivery) and late (between 8 and 28 days after delivery) deaths. Perinatal deaths were defined as the sum of fresh stillbirths and early neonatal deaths.

Maternal morbidity parameters included: blood loss exceeding 600 ml, reoperation, readmission, wound infection and postoperative pain. Presence of persistent postoperative abdominal pain and readmission were surveyed during home visits. Wound infections and reoperations were either reported during admission or assessed during the home visit. In addition, duration of operation (interval from incision to final closure) and duration of hospital stay (excluding readmission) were recorded.

Statistical analysis

The sample size calculation was based on the non‐inferiority assumption that caesarean sections performed by ACs are non‐inferior to those done by doctors for the primary outcome perioperative maternal mortality. Comparable studies reported a maternal mortality rate after caesarean section between 0·8 and 2·0 per cent16, 17. As Sierra Leone has the world's highest maternal mortality rate, the upper limit of 2·0 per cent was used. In a previous meta‐analysis9, the lower bound of the confidence interval was an odds ratio (OR) of 2·75, which, with an average mortality rate of 2·0 per cent, led to a suggested non‐inferiority margin of 5·5 per cent. By applying a conservative approach and taking into account the importance of the outcome measure mortality, the non‐inferiority margin was set at 2·5 per cent (equivalent to an OR of 2·31 with a 2·0 per cent mortality rate)18. With α = 0·05 and β = 0·10, an expected success rate in both groups of 98 per cent and a non‐inferiority limit of 2·5 per cent, the total required sample size was calculated to be 107619. With an anticipated loss to follow‐up of 10 per cent, inclusion of a total of 1195 patients was required.

Baseline and operative characteristics are presented as numbers with percentages and mean(s.d.) values. Missing data are indicated in the tables. Student's t test was used for comparison of numerical means and Fisher's exact test to compare categorical data. ORs were calculated by exact logistic regression and presented with 90 per cent confidence intervals, corresponding to a significance of 0·05 (α) for testing in a non‐inferiority analysis18. For the primary outcome, perioperative maternal death, both crude ORs and ORs adjusted for clusters using exact logistic regression are presented. P < 0·050 was considered statistically significant for equality tests. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata® 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). The primary data are available from the corresponding author on request.

Results

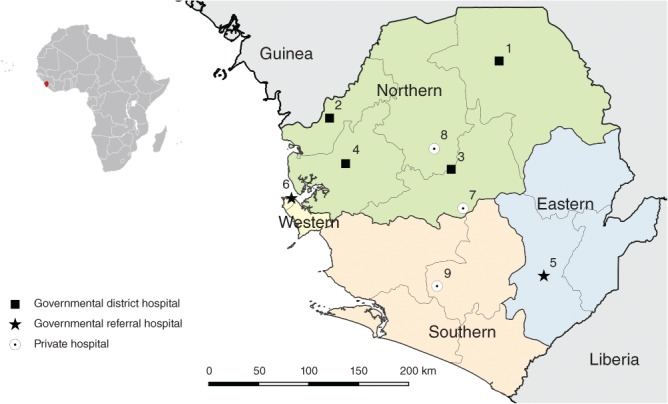

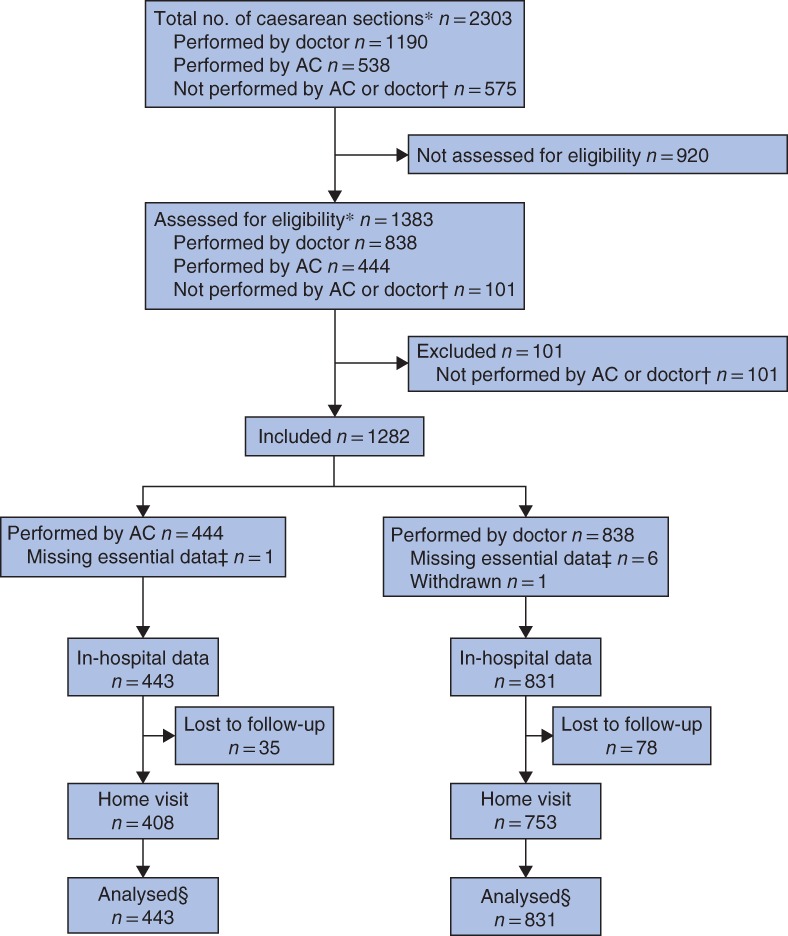

All nine eligible public and private hospitals agreed to participate and took part in the study (Fig. 1, Table 1). Between 1 October 2016 and 5 May 2017, 2303 caesarean sections took place in the study facilities and 1383 were assessed for eligibility to participate in the study. In total, 101 patients were excluded because the caesarean section was not performed by a doctor or AC (Fig. 2). Essential data were not recorded for one patient in the AC group and six in the doctor group; one patient in the doctor group withdrew from the study. Of the 1274 patients for whom data were analysed, 443 caesarean sections were done by an AC and 831 by a doctor as the primary surgical provider.

Figure 1.

Nine hospitals in Sierra Leone where both medical doctors and associate clinicians performed caesarean section and surgery for uterine rupture. 1, Kabala Governmental Hospital; 2, Kambia Governmental Hospital; 3, Magburaka Governmental Hospital; 4, Port Loko Governmental Hospital; 5, Kenema Governmental Hospital; 6, Princess Christian Maternity Hospital, Freetown; 7, Lion Heart Medical Centre; 8, Magbenteh Community Hospital; 9, Serabu Catholic Hospital

Table 1.

Numbers of surgical providers and surgical procedures included in the study at each hospital

| No. of surgical providers | No. of surgical procedures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | AC | Doctor | AC | Doctor | |

| Kabala Governmental Hospital | District | 2 | 6 | 23 | 55 |

| Kambia Governmental Hospital | District | 1 | 3 | 57 | 43 |

| Magburaka Governmental Hospital | District | 1 | 5 | 80 | 115 |

| Port Loko Governmental Hospital | District | 1 | 5 | 8 | 52 |

| Kenema Governmental Hospital | Regional | 1 | 1 | 68 | 52 |

| Princess Christian Maternity Hospital, Freetown | Tertiary | 2 | 19 | 118 | 385 |

| Lion Heart Medical Centre | PNP | 1 | 3 | 6 | 33 |

| Magbenteh Community Hospital | PNP | 2 | 1 | 61 | 27 |

| Serabu Catholic Hospital | PNP | 1 | 7 | 22 | 69 |

| Total | 12 | 50 | 443 | 831 | |

AC, associate clinician; PNP, private non‐profit.

Figure 2.

Study flow chart. *Including laparotomy for uterine rupture. †Procedures performed by trainees and health workers without formal surgical training. ‡Patient identification data required to trace patient file and carry out follow‐up visit. §Analysed data from patients with and without home visit. AC, associate clinician

Of the 1282 enrolled patients, 1161 (90·6 per cent) were visited at home after discharge. During the home visits, three additional maternal and 28 neonatal deaths were identified after discharge from hospital. By validating outcome data collected from the hospitals, 13 additional stillbirths and 11 additional in‐hospital neonatal deaths were identified. One baby recorded in the hospital as a stillbirth and one as a neonatal death were found alive during the home visits. For the primary outcome, perioperative maternal mortality, no recording errors were found.

Table 2 shows the patient and operative characteristics. A significantly higher proportion of caesarean sections for twin pregnancies and on multiparous women were performed by an AC; a significantly higher proportion of operations undertaken by a doctor were done outside office hours, as an emergency, and were more often combined with additional procedures such as hysterectomy, B‐Lynch procedures or tubal ligations. No significant differences between the groups were found in age, level of education, antenatal visits or indications.

Table 2.

Patient, operative and surgical provider characteristics

| Associate clinicians (n = 443) | Doctors (n = 831) | P †† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Age (years)* | 26·3 (6·3) | 26·0 (7·1) | 0·576‡‡ |

| Estimated travel time (h) | 0·261 | ||

| ≤ 2 | 357 (80·6) | 655 (78·8) | |

| > 2 | 85 (19·2) | 167 (20·1) | |

| Missing | 1 (0·2) | 9 (1·1) | |

| Highest educational level | 0·221 | ||

| None | 171 (38·6) | 280 (33·7) | |

| Primary | 43 (9·7) | 109 (13·1) | |

| Secondary | 154 (34·8) | 282 (33·9) | |

| Tertiary | 40 (9·0) | 82 (9·9) | |

| Missing | 35 (7·9) | 78 (9·4) | |

| Single/multiple pregnancy | 0·010 | ||

| Single pregnancy | 391 (88·3) | 769 (92·5) | |

| Twin pregnancy | 52 (11·7) | 60 (7·2) | |

| Triplet pregnancy | 0 (0) | 2 (0·2) | |

| Parity | 0·045 | ||

| Nullipara (p0) | 132 (29·8) | 287 (34·5) | |

| Multipara (p1–4) | 265 (59·8) | 437 (52·6) | |

| Grand multipara (≥ p5) | 46 (10·4) | 107 (12·9) | |

| ≥ 3 antenatal clinic visits | 399 (90·1) | 730 (87·8) | 0·266 |

| Previous CS | 0·238 | ||

| 0 | 349 (78·8) | 679 (81·7) | |

| 1 | 70 (15·8) | 99 (11·9) | |

| ≥ 2 | 19 (4·3) | 44 (5·3) | |

| Yes, unknown number | 5 (1·1) | 9 (1·1) | |

| Indication | 0·44 | ||

| Antepartum haemorrhage† | 48 (10·8) | 102 (12·3) | |

| Obstructed and prolonged labour‡ | 246 (55·5) | 454 (54·6) | |

| Uterine rupture | 15 (3·4) | 40 (4·8) | |

| Fetal indication§ | 29 (6·5) | 60 (7·2) | |

| Previous CS | 67 (15·1) | 97 (11·7) | |

| Other¶ | 38 (8·6) | 78 (9·4) | |

| Emergency CS | 360 (81·3) | 739 (88·9) | < 0·001 |

| Operation out of office hours (16.00 to 08.00 hours) | 168 (37·9) | 420 (50·5) | < 0·001 |

| Operative characteristics | |||

| Duration of operation (min)*# | 33·4(16·7) | 41·0(24·4) | < 0·001‡‡ |

| Midline incision | 39 (8·8) | 87 (10·5) | 0·376 |

| Type of operation | 0·043 | ||

| CS only | 404 (91·2) | 727 (87·5) | |

| CS + hysterectomy | 5 (1·1) | 30 (3·6) | |

| CS + B‐Lynch | 13 (2·9) | 25 (3·0) | |

| CS + tubal ligation | 21 (4·7) | 49 (5·9) | |

| Anaesthesia | 1·000 | ||

| Spinal anaesthesia | 262 (59·1) | 492 (59·2) | |

| General anaesthesia | 181 (40·9) | 339 (40·8) | |

| Surgical provider characteristics | n = 12 | n = 50 | |

| Nationality | 0·001 | ||

| Sierra Leonean | 12 (100) | 25 (50) | |

| Non‐Sierra Leonean | 0 (0) | 25 (50) | |

| Working experience (years)** | 0·001 | ||

| < 1 | 4 (33) | 4 (8) | |

| 1–5 | 7 (58) | 16 (32) | |

| > 5 | 1 (8) | 30 (60) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are mean(s.d.).

Abruptio placentae and placenta praevia.

Malpresentation, retained second twin and failure of induction.

Cord prolapse, fetal distress, oligohydramnion and polyhydramnion, premature rupture of membranes and post‐term.

Poor obstetric history, elderly primigravida.

Total operating time per patient (all types of operation).

As surgical provider after graduation at the start of the study, October 2016. CS, caesarean section.

Fisher's exact test, except

Student's t test.

In total, 12 ACs and 50 doctors contributed to the study. All but one of the ACs were trained in the country. Half of the doctors had a Sierra Leonean nationality. In the group of Sierra Leonean doctors, one of the 25 was a specialist, compared with 13 of the 25 non‐Sierra Leonean doctors. Only one of the 12 ACs had more than 5 years of working experience after graduation, compared with 30 of 50 doctors.

Primary outcome

Among a total of 16 postoperative maternal deaths in the study, one woman was treated by an AC (0·2 per cent) and 15 by a doctor (1·8 per cent); the crude OR was 0·12 (90 per cent c.i. 0·01 to 0·67) and the adjusted OR for clusters (9 hospitals) was 0·11 (0·01 to 0·63). The confidence interval for both the crude and adjusted ORs fell within the predefined inferiority limit of 2·31. Two of the maternal deaths occurred during surgery, 11 between surgery and discharge, and three between discharge and 30 days after surgery (Table S1, supporting information).

Secondary outcomes

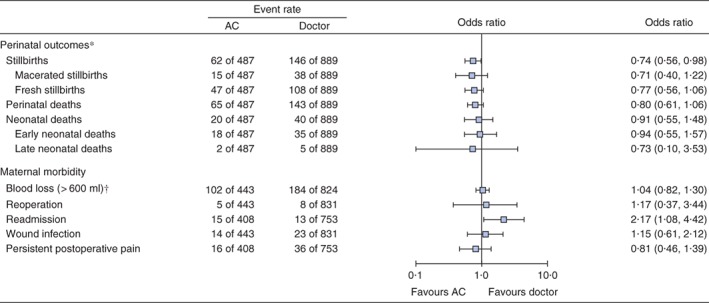

There was a total of 62 stillbirths (12·7 per cent) in the AC‐treated group, compared with 146 (16·4 per cent) in the doctor group (OR 0·74, 90 per cent c.i. 0·56 to 0·98). No other significant differences were found in the number of fresh and macerated stillbirths, perinatal deaths, and early and late neonatal deaths (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Perinatal outcomes and maternal morbidity for caesarean sections performed by associate clinicians compared with medical doctors. *Analyses based on a total of 1376 babies. †Based on visual estimation by the surgical provider. Odds ratios are presented with 90 per cent confidence intervals. AC, associate clinician

Caesarean sections alone done by an AC were 7 min quicker than those done by doctors (31·9 and 38·9 min respectively; P < 0·001), but women treated by an AC were more than twice as likely to be readmitted to hospital (OR 2·17, 1·08 to 4·42) (Fig. 3; Table S2, supporting information). There were no significant differences in blood loss exceeding 600 ml, reoperation, wound infection, persistent postoperative abdominal pain or duration of hospital stay.

Discussion

Access to safe surgical services is necessary to obtain universal health coverage7. In areas where there is a lack of a specialized health workforce, task‐sharing can be an affordable strategy to increase the number of surgical providers20. In this study, caesarean section done by an AC was not associated with a higher perioperative maternal mortality rate after 30 days than caesarean section undertaken by a doctor. The incidence of adverse perinatal outcomes was also similar.

The strength of this study is the prospective design, with a 30‐day follow‐up. Five16, 17, 21, 22, 23 of the seven previously published studies on the same topic were retrospective and the two prospective studies24, 25 followed the patients only until discharge from hospital.

The home visits improved the quality of the collected data. A further three maternal and 28 neonatal deaths were identified after discharge from hospital. Even more important was the role the home visits had in validating data collected in the hospitals. A total of 13 stillbirths and 11 neonatal deaths had not been recorded at the hospitals, and one baby with the birth recorded as stillbirth and one as neonatal death were found alive at the home visits.

The optimal design for comparing standard and alternative treatments is the double‐blind RCT. Randomization was not feasible because of the high proportion of emergency operations, and because both a doctor and an AC were often not available at the same time. Furthermore, blinding the patient to the profession of the surgical provider would not be ethical. The surgical provider category was coded on the case report forms, but the research nurses were not fully blinded because they had both responsibility to review data inside the hospitals and to undertake the home visits. To avoid favouring either group, anaesthesia personnel collected the in‐hospital data and research nurses led the home visits.

Confounding by unequal distribution of women could explain some of the differences in outcomes between the two groups. Statistical adjustment for these confounders was not possible as the total number of events for the primary outcome was low. Doctors performed more operations out of office hours as well as more emergency procedures, whereas caesarean sections for multiple pregnancies were more commonly done by ACs. Selection of surgical providers was based mainly on availability; ACs were less available during out‐of‐office hours, because many did not live in the hospital compound, in contrast to the doctors. However, if doctors positively selected the more complicated cases, this could be seen as a desired distribution of risks where the more competent health workers handle patients with higher risks.

This study has demonstrated that task‐sharing is a safe strategy to increase access to emergency obstetric care in West Africa. Expansion of the surgical workforce could be quicker and more cost‐effective than traditional training of doctors3. Furthermore, it increases retention in rural areas16, where unmet surgical need is highest26.

The shortage of surgical providers in many low‐income countries and few postgraduate training opportunities for doctors support the need for new strategies5, 27. Redistribution of medical tasks can be complex, and needs surveillance and monitoring. A programme from India where non‐specialist doctors were trained in emergency obstetrics was discontinued because of a lack of comprehensive monitoring, poor supervision and limited incentives and career prospects28.

The use of less trained surgical providers might lead to misdiagnosis and suboptimal decisions on when to operate10. In this study, no significant difference was found between indications for caesarean section between ACs and doctors. This does not eliminate the importance of accurate assessment of the indication for caesarean section to minimize the amount of unnecessary surgery29.

Supporting information

Table S1 Perioperative maternal deaths

Table S2 Supportive information for secondary outcomes

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all mothers and children who took part in the study; all anaesthesia teams, ACs and doctors in the participating hospitals; the research nurses who travelled to all corners of the country for the home visits; the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) for supporting the surgical training programme and the logistics for this study; and M. Rijken and J. Westendorp for their input on the manuscript.

The Liaison Committee between the Central Norway Regional Health Authority and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology funded all parts of the study. The funding source had no role in any aspect of the study. A.J.v.D. and H.A.B. are unpaid board members of CapaCare, the non‐governmental organization responsible for organizing the surgical training programme for doctors and community health officers in Sierra Leone in collaboration with the Ministry of Health and Sanitation. A.P.K. has received an allowance for conducting examinations. M.E. is employed by UNFPA in Sierra Leone, the main funder of the surgical training programme in Sierra Leone.

Disclosure: The authors declare no other conflict of interest.

The study protocol with preliminary findings was presented to the 58th Annual Conference of the West African College of Surgeons, Banjul, Gambia, March 2018

References

- 1. Petroze RT, Mehtsun W, Nzayisenga A, Ntakiyiruta G, Sawyer RG, Calland JF. Ratio of cesarean sections to total procedures as a marker of district hospital trauma capacity. World J Surg 2012; 36: 2074–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hughes CD, McClain CD, Hagander L, Pierre JH, Groen RS, Kushner AL et al Ratio of cesarean deliveries to total operations and surgeon nationality are potential proxies for surgical capacity in central Haiti. World J Surg 2013; 37: 1526–1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L, Alkire BC, Alonso N, Ameh EA et al Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet 2015; 386: 569–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dare AJ, Grimes CE, Gillies R, Greenberg SL, Hagander L, Meara JG et al Global surgery: defining an emerging global health field. Lancet 2014; 384: 2245–2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Holmer H, Shrime MG, Riesel JN, Meara JG, Hagander L. Towards closing the gap of the global surgeon, anaesthesiologist, and obstetrician workforce: thresholds and projections towards 2030. Lancet 2015; 385(Suppl 2): S40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. The World Bank Group . World Bank Open Data; 2018. https://data.worldbank.org [accessed 5 May 2018].

- 7. WHO . WHA 68.15: Strengthening Emergency and Essential Surgical Care and Anaesthesia as a Component of Universal Health Coverage; 2015. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21904en/s21904en.pdf [accessed 18 June 2018].

- 8. WHO . Optimizing Health Worker Roles to Improve Access to Key Maternal and Newborn Health Interventions through Task Shifting; 2012. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/978924504843/en/ [accessed 15 April 2018]. [PubMed]

- 9. Wilson A, Lissauer D, Thangaratinam S, Khan KS, MacArthur C, Coomarasamy A. A comparison of clinical officers with medical doctors on outcomes of caesarean section in the developing world: meta‐analysis of controlled studies. BMJ 2011; 342: d2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Galukande M, Kaggwa S, Sekimpi P, Kakaire O, Katamba A, Munabi I et al Use of surgical task shifting to scale up essential surgical services: a feasibility analysis at facility level in Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res 2013; 13: 292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brolin Ribacke KJ, van Duinen AJ, Nordenstedt H, Höijer J, Molnes R, Froseth TW et al The impact of the West Africa Ebola outbreak on obstetric health care in Sierra Leone. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0150080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Statistics Sierra Leone (SSL) and ICF International. Sierra Leone Demographic and Health Survey 2013 https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR297/FR297.pdf [accessed 15 April 2018].

- 13. Bolkan HA, Hagander L, von Schreeb J, Bash‐Taqi D, Kamara TB, Salvesen Ø et al The surgical workforce and surgical provider productivity in Sierra Leone: a countrywide inventory. World J Surg 2016; 40: 1344–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bolkan HA, van Duinen A, Waalewijn B, Elhassein M, Kamara TB, Deen GF et al Safety, productivity and predicted contribution of a surgical task‐sharing programme in Sierra Leone. Br J Surg 2017; 104: 1315–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gold KJ, Abdul‐Mumin AR, Boggs ME, Opare‐Addo HS, Lieberman RW. Assessment of ‘fresh’ versus ‘macerated’ as accurate markers of time since intrauterine fetal demise in low‐income countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2014; 125: 223–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pereira C, Bugalho A, Bergström S, Vaz F, Cotiro M. A comparative study of caesarean deliveries by assistant medical officers and obstetricians in Mozambique. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1996; 103: 508–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hounton SH, Newlands D, Meda N, De Brouwere V. A cost‐effectiveness study of caesarean‐section deliveries by clinical officers, general practitioners and obstetricians in Burkina Faso. Hum Resour Health 2009; 7: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schumi J, Wittes JT. Through the looking glass: understanding non‐inferiority. Trials 2011; 12: 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sealed Envelope. Power Calculator for Binary Outcome Non‐inferiority Trial https://www.sealedenvelope.com/power/binary‐noninferior/ [accessed 12 April 2016].

- 20. Bergström S. Training non‐physician mid‐level providers of care (associate clinicians) to perform caesarean sections in low‐income countries. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2015; 29: 1092–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gessessew A, Barnabas GA, Prata N, Weidert K. Task shifting and sharing in Tigray, Ethiopia, to achieve comprehensive emergency obstetric care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011; 113: 28–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. White SM, Thorpe RG, Maine D. Emergency obstetric surgery performed by nurses in Zaïre. Lancet 1987; 2: 612–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chilopora G, Pereira C, Kamwendo F, Chimbiri A, Malunga E, Bergström S. Postoperative outcome of caesarean sections and other major emergency obstetric surgery by clinical officers and medical officers in Malawi. Hum Resour Health 2007; 5: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fenton PM, Whitty CJ, Reynolds F. Caesarean section in Malawi: prospective study of early maternal and perinatal mortality. BMJ 2003; 327: 587–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McCord C, Mbaruku G, Pereira C, Nzabuhakwa C, Bergstrom S. The quality of emergency obstetrical surgery by assistant medical officers in Tanzanian district hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009; 28: w876–w885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bolkan HA, Von Schreeb J, Samai MM, Bash‐Taqi DA, Kamara TB, Salvesen Ø et al Met and unmet needs for surgery in Sierra Leone: a comprehensive, retrospective, countrywide survey from all health care facilities performing operations in 2012. Surgery 2015; 157: 992–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rickard J. Systematic review of postgraduate surgical education in low‐ and middle‐income countries. World J Surg 2016; 40: 1324–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Balsari S, Simon G, Nair R, Saunik S, Phadke M. Task shifting in health care: the risks of integrated medicine in India. Lancet Glob Health 2017; 5: e963–e964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rijken MJ, Meguid T, van den Akker T, van Roosmalen J, Stekelenburg J; Dutch Working Party for International Safe Motherhood and Reproductive Health. Global surgery and the dilemma for obstetricians. Lancet 2015; 386: 1941–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Perioperative maternal deaths

Table S2 Supportive information for secondary outcomes