ABSTRACT

Objective

To generate guidance for detailed uterine niche evaluation by ultrasonography in the non‐pregnant woman, using a modified Delphi procedure amongst European experts.

Methods

Twenty gynecological experts were approached through their membership of the European Niche Taskforce. All experts were physicians with extensive experience in niche evaluation in clinical practice and/or authors of niche publications. By means of a modified Delphi procedure, relevant items for niche measurement were determined based on the results of a literature search and recommendations of a focus group of six Dutch experts. It was predetermined that at least three Delphi rounds would be performed (two online questionnaires completed by the expert panel and one group meeting). For it to be declared that consensus had been reached, a consensus rate for each item of at least 70% was predefined.

Results

Fifteen experts participated in the Delphi procedure. Consensus was reached for all 42 items on niche evaluation, including definitions, relevance, method of measurement and tips for visualization of the niche. A niche was defined as an indentation at the site of a Cesarean section with a depth of at least 2 mm. Basic measurements, including niche length and depth, residual and adjacent myometrial thickness in the sagittal plane, and niche width in the transverse plane, were considered to be essential. If present, branches should be reported and additional measurements should be made. The use of gel or saline contrast sonography was preferred over standard transvaginal sonography but was not considered mandatory if intrauterine fluid was present. Variation in pressure generated by the transvaginal probe can facilitate imaging, and Doppler imaging can be used to differentiate between a niche and other uterine abnormalities, but neither was considered mandatory.

Conclusion

Consensus between niche experts was achieved regarding ultrasonographic niche evaluation. © 2018 The Authors. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Keywords: Cesarean section, cicatrix, Delphi technique, ultrasonography

Short abstract

This article's abstract has been translated into Spanish and Chinese. Follow the links from the abstract to view the translations.

This article has been selected for Journal Club. Click here to view slides and discussion points.

This article has been selected for Journal Club. Click here to view slides and discussion points.

RESUMEN

Examen ecográfico del istmocele en mujeres no embarazadas: un procedimiento Delphi modificado

Objetivos

Generar una guía para la evaluación detallada del istmocele mediante ecografía en mujeres no embarazadas, utilizando un procedimiento Delphi modificado entre expertos europeos.

Métodos

Se contactó a veinte expertos en ginecología entre los miembros del Grupo de Trabajo Europeo de Istmocele (European Niche Taskforce). Todos los expertos eran médicos con amplia experiencia en evaluación de istmocele en la práctica clínica y/o autores de publicaciones sobre istmocele. Se empleó un procedimiento Delphi modificado para determinar los parámetros relevantes para la medición de istmoceles, basándose en los resultados de una búsqueda bibliográfica y en las recomendaciones de un grupo focal de seis expertos holandeses. Se predeterminó que se realizarían al menos tres rondas Delphi (dos cuestionarios en línea cumplimentados por el grupo de expertos y una reunión del grupo). Para declarar que se había alcanzado el consenso, se predefinió una tasa de consenso para cada parámetro de al menos el 70%.

Resultados

Quince expertos participaron en el procedimiento Delphi. Se llegó a un consenso sobre los 42 parámetros relativos a la evaluación de los istmoceles, incluidas sus definiciones, pertinencia, el método de medición y los consejos para la visualización de los istmoceles. Se definió un istmocele como una hendidura en el lugar de una cesárea con una profundidad de al menos 2 mm. Se consideraron esenciales ciertas mediciones básicas como la longitud y la profundidad del istmocele, el espesor del miometrio residual y adyacente en el plano sagital y el ancho del istmocele en el plano transversal. En caso de estar presentes, se deberán notificar las ramificaciones y realizar mediciones adicionales. Se prefirió el uso de la ecografía con gel o por contraste salino a la ecografía transvaginal estándar, pero no se consideró obligatoria si había líquido intrauterino presente. La variación en la presión generada por la sonda transvaginal puede facilitar la obtención de imágenes y las imágenes Doppler se pueden usar para diferenciar entre un istmocele y otras anomalías uterinas, pero no se consideran obligatorias.

Conclusión

Se logró un consenso entre expertos en istmocele con respecto a la evaluación ecográfica de istmocele.

摘要

非妊娠女性中超声检查子宫憩室:一种改良的Delphi法

目的

欧洲专家采用一种改良的Delphi法,建立非妊娠女性中通过超声检查详细评估子宫憩室的指南。

方法

20名妇科专家均为欧洲子宫憩室特别工作组成员。所有专家均是对临床实践中憩室评估具有丰富经验的医生和(或)发表过憩室研究文章的作者。采用一种改良的Delphi法,根据文献检索结果以及6名荷兰专家组成的专题小组提出的建议,确定憩室检测的相关问题。预定进行至少3轮Delphi法(2次由专家组完成在线问卷调查,1次小组会议)。预先规定每个问题的一致率至少达到70%,才能认定达成一致意见。

结果

15名专家参与了Delphi法的实施。对憩室评估的42个问题全部达成一致意见,包括定义、相关性、检测方法以及憩室观察要点。将剖宫产切口处深度至少为2 mm的凹陷定义为子宫憩室。有必要进行基本检查,包括憩室长度和深度、矢状面残余和邻近肌层厚度、横断面憩室宽度。如果发现子宫憩室,应当报告并进行其他检查。与标准的经阴道超声相比,优先采用凝胶或生理盐水对比超声,但如果存在宫腔积液,则不强制采用。经阴道探头产生的压力变化能够促进成像,可以采用多普勒成像鉴别子宫憩室和其他子宫异常,但不强制采用。

结论

子宫憩室专家就超声评估子宫憩室达成一致意见。

INTRODUCTION

Cesarean section (CS) rates are increasing worldwide, with a corresponding increase in associated complications. The CS scar defect or ‘niche’ has been reported as an important feature that is associated with future complications. Recently, it has been demonstrated that niches may be the causative factor for abnormal uterine bleeding, dysmenorrhea, obstetric complications in subsequent pregnancies and, possibly, subfertility1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. The relationship between various niche features and symptoms has not been elucidated fully, although both niche volume and the ‘healing ratio’ (residual myometrial thickness (RMT)/adjacent myometrial thickness (AMT)) have been reported to be associated with abnormal uterine bleeding3, 4. Therefore, the accurate measurement and description of a niche is becoming increasingly important, for research, for the clinical assessment of gynecological symptoms and for the planning of possible surgical treatment6, 7.

Although many studies have evaluated the development of niches and associated symptoms, there is no standardized guideline for their examination, measurement or description8. A niche can be examined using two‐ (2D) or three‐ (3D) dimensional transvaginal sonography (TVS), with or without saline or gel contrast, magnetic resonance imaging and hysteroscopy4, 9, 10, 11, 12. Naji et al.13 proposed a standardized approach for niche description using ultrasonography in non‐pregnant women, based on definitions and methods described in the literature. However, their proposed approach to document the size of a niche did not take into account variations that occur in scar morphology.

Having identified the need for more detailed practical guidance for clinicians, we decided to develop this, focusing on non‐pregnant women. (It should be borne in mind that there is a considerable difference between measuring a niche in a pregnant woman and doing so in a non‐pregnant one.) We considered a Delphi method to be the most suitable means, as this could achieve consensus amongst international experts in a structured way. This technique has been used widely in healthcare research, in particular within the field of education and training, and in developing clinical practice14, 15. The aim of this study was to generate guidance for detailed uterine niche evaluation using ultrasonography in the non‐pregnant woman, by means of a modified Delphi procedure amongst European experts.

METHODS

Design of a modified Delphi study

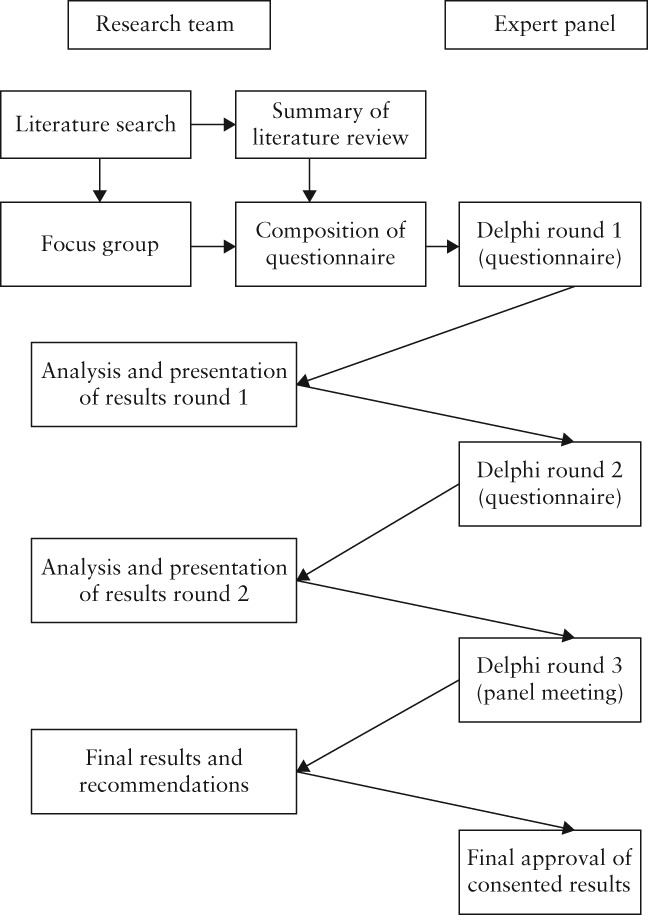

To achieve consensus, we followed a modified Delphi procedure (Figure 1). We carried out a systematic literature search and formed a focus group of Dutch experts to identify relevant items for niche assessment and design a questionnaire on niche measurement, which would be answered online anonymously by the experts participating in the Delphi study. A modified Delphi procedure was applied, with repeated rounds of the questionnaire, to enable the participating experts to reflect on the results of each previous questionnaire round in a structured manner. Thus, in each round, after analysis of the collective opinion of the group, the results of one round were used as the basis for formulating the next. It was predetermined that the process would include at least three rounds (two online questionnaire rounds and one face‐to‐face meeting) and additional rounds if required until data saturation was achieved. The data were collected between May and October 2016.

Figure 1.

Study design: stepwise modified Delphi method used to reach consensus on uterine niche definition and sonographic evaluation.

Literature search to collect data for first Delphi round

A systematic search of the literature up to October 2015 was performed in PubMed and EMBASE databases, with the assistance of a clinical librarian. We searched for all possible methodological items describing ultrasonographic evaluation of uterine scar in non‐pregnant women (see Appendix S1 for search strategy). Duplicate articles were excluded. We included any English or Dutch article that reported on niche measurement by ultrasound and reported on one or more of a set of questions that was predetermined by J.H., R.L. and I.J. The questions concerned: (1) the optimal timing for measuring a niche following CS; (2) the best infusion fluid (gel or saline); (3) whether 2D or 3D ultrasonography should be used; (4) what features of the niche should be measured; (5) the best time in the menstrual cycle for measurement; (6) the relevance of pressure from the transvaginal probe; (7) the relevance of Doppler ultrasound; and (8) the relevance of measuring the distance between the vesicovaginal (VV) fold and the internal os. From all reviewed papers, we extracted all items that could possibly be relevant in a concept questionnaire for the Delphi procedure, and these were presented to the focus group for final selection.

Focus group and development of questionnaire used in first Delphi round

The focus group contained six Dutch experts who had participated previously in the Dutch HYSNICHE trial16 (Hysteroscopic resection of uterine Caesaran scar defect (niche) in patients with abnormal bleeding, a randomized controlled trial) and SCAR4 (Sonohysterographic evaluation of Caesarean scar defects and determination of risk factors) or SECURE3 (Scar Evaluation after Caesarean by Ultrasound Registry) studies. In a face‐to‐face meeting, a proposal for the Delphi questionnaire that included the items that we had identified as being potentially relevant for niche measurement (illustrated by ultrasonographic images) was discussed to determine internal validity. We recorded and analyzed all comments and recommendations discussed in this meeting. A summary of the results was sent to the members of the focus group for feedback. Based on these results, an online questionnaire for the first round of the Delphi procedure was designed.

Expert panel recruitment

In order to form an expert panel comprising members with sufficient experience in niche measurement, members of the European Niche Taskforce were invited to participate in the Delphi procedure. These experts were each asked to invite one colleague, from the same institute, who was known to have sufficient experience in the field. For the purpose of this Delphi procedure, an ‘expert’ was predefined as a gynecologist or resident who performed more than 30 niche evaluations a year, or who had published at least one article on niches in a peer‐reviewed journal or given at least one presentation concerning ultrasound and niches at an appropriate conference. In total, 20 experts were invited. After confirmation of their participation, the experts each received an email containing a unique link to the online questionnaire. In the first questionnaire, the experts confirmed the items selected by the focus group.

Delphi rounds and structural consensus method

The answers from all experts were analyzed for each question. Consensus was predefined as a rate of agreement (RoA) > 70%, where RoA = (agreement – disagreement)/ (agreement + disagreement + indifferent) × 100%; this is a commonly used cut‐off value for consensus14, 17, 18. If no consensus was reached, the question was transferred to the second round and the results of the first round were fed back anonymously, including the reasoning of the respondents. Additional questions seeking clarification were added as appropriate. Non‐responders in the first round were not invited to participate in the following rounds. Based on the results of the second round, a draft set of recommendations was designed. These results were presented in a face‐to‐face meeting at the European Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy world congress in Brussels, in October 2016, and the items without consensus were discussed. We recorded all comments and recommendations made in this meeting. The experts could reflect on their reasoning and, if necessary, reconsider their opinion. The final results of the agreed items were sent to all experts who had participated in the first round for final approval.

RESULTS

Literature search

The literature search resulted in 1034 papers after removal of duplicates (Appendix S1). All titles and abstracts were reviewed by two of the authors (I.J. and R.L.) and 908 articles were excluded because their subject was not related to niche measurement. After assessing the full text of the remaining 126 articles, we identified 10 papers that reported on our predefined research questions. The main results of the search are presented in Table 1. In total, six papers reported higher detection rates of niches using saline or gel contrast rather than standard TVS3, 4, 5, 10, 19, 20. Two papers assessed the value of 3D‐TVS21, 22 and two proposed methodology for niche measurement5, 13. Fabres et al.23 reported that the best time during the menstrual cycle to evaluate a niche is during menstruation. No literature was available to address our other research questions. Based on these 10 studies, we formulated 11 main topics and 19 subtopics as being potentially relevant for niche measurement and presented these for discussion to the focus group (Appendix S2). The most relevant and illustrative results of our literature search were also presented to the experts in an evidence table scored according to the GRADE method24 (Appendix S3).

Table 1.

Results of literature search which identified 10 papers3, 4, 5, 10, 13, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 reporting on predefined research questions regarding sonographic measurement of uterine niche

| Predefined research question | Study | Study type | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal timing after CS to measure niche | None | ||

| Best method (TVS or with contrast) for measurement | Allison (2010)19 | Overview of literature | Saline contrast is a useful adjunct to TVS, especially for evaluation of endometrium and adjacent lesions. |

| Baranov (2016)10 | Cohort study | Scar defects in 46.4% of cases seen by both observers on TVS; scar defects in 69.1% of cases seen by both observers on saline contrast. | |

| Vikhareva Osser (2009)20 | Cohort study | 53 scar defects seen on saline contrast; 42 scar defects seen on TVS. | |

| Tower (2013)5 | Overview of literature | Saline contrast has higher sensitivity and specificity for detection of CS scar defects than does TVS. Recommendation based on literature: if CS defect is suspected, evaluation using saline contrast is recommended unless this is unacceptable or contraindicated in the patient, in which case TVS can be used. | |

| Bij de Vaate (2011)3 | Observational prospective cohort study | Prevalence of niche on TVS = 24%; prevalence of niche using gel infusion = 56%. | |

| van der Voet (2014)4 | Prospective cohort study | Prevalence of niche on TVS = 49.6%; prevalence of niche using gel infusion = 64.5%. | |

| Best method (3D‐ or 2D‐TVS) to use for measurement | Bij de Vaate (2015)21 | Prospective cohort study | 3D is a reproducible tool for niche measurement (size and RMT) in sagittal plane. |

| Giral (2015)22 | Retrospective study | Prevalence of niche on 3D‐TVS = 50%; prevalence of niche on 2D saline contrast sonography = 86%. | |

| Niche measurements | Naji (2012)13 | Overview of literature | Length, width, depth of niche and RMT should be measured in both sagittal and transverse planes; see illustration in their paper. |

| Tower (2013)5 | Overview of literature | RMT is measured from apex of defect to outer edge of myometrium. | |

| Best time in menstrual cycle to measure niche | Fabres (2003)23 | Retrospective study | Best time during cycle to identify CS defect with sonography is during bleeding episode, usually a few days after menses. |

| Relevance of pressure from transvaginal probe | None | ||

| Relevance of Doppler ultrasound | None | ||

| Relevance of measurement between VV fold and internal os | None |

Only first author of each study is given.

CS, Cesarean section; RMT, residual myometrial thickness; TVS, unenhanced transvaginal sonography; VV, vesicovaginal.

Focus group participation and Delphi procedure

The focus group discussion took place on 10 January 2016. It was recorded and transcribed, resulting in an analysis of 50 keywords using Atlas.ti.software25. Analyzing these keywords, 40 relevant items comprising 79 questions emerged for inclusion in the first online questionnaire. These questions could be categorized as: definitions and methods of measurement and their relevance, general ultrasound methods (including machine settings), additional tools (including Doppler ultrasound) and the use of gel or saline contrast. Appendix S4 gives an overview of questions of both questionnaires and subjects discussed during the face‐to‐face meeting.

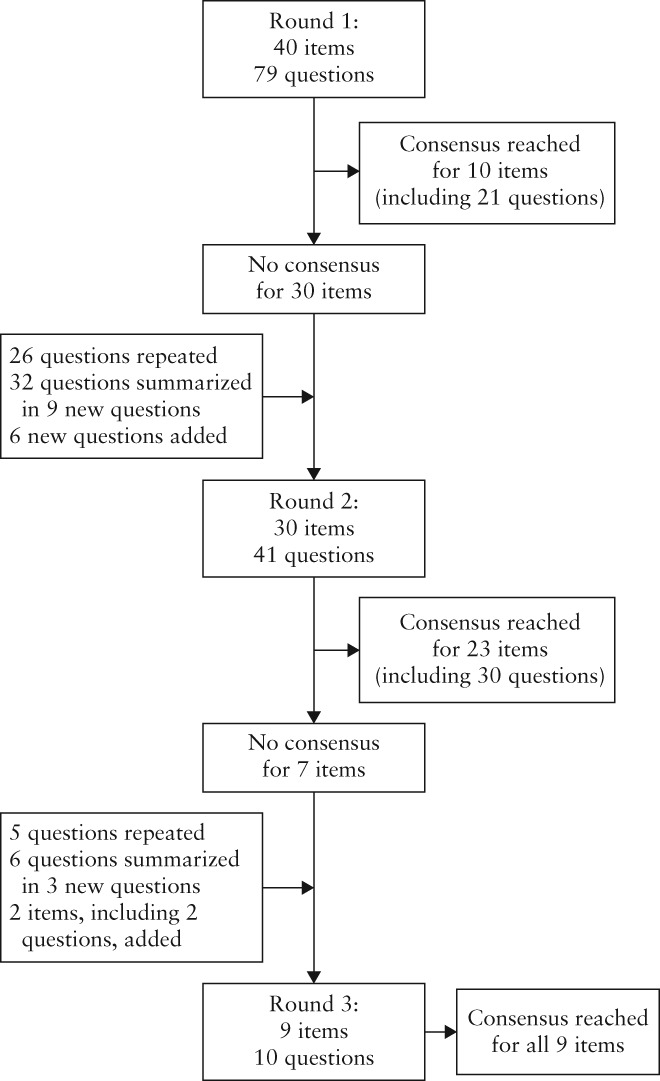

During successive rounds of the procedure, a further two items were added. A total of 15 experts were involved in the first round of the Delphi procedure and completed the first online questionnaire. Of these, 12 (80%) also completed the second round and nine were able to participate in the face‐to‐face meeting. All 15 participants of the first round agreed on the final results, and consensus was reached for all 42 items (Figure 2). Table S1 presents the mean consensus achieved per item in each round of the Delphi procedure.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram summarizing agreement with or rejection of items during Delphi procedure. Items were accepted if consensus agreement of at least 70% was reached.

Agreed recommendations and statements

Definitions and relevance

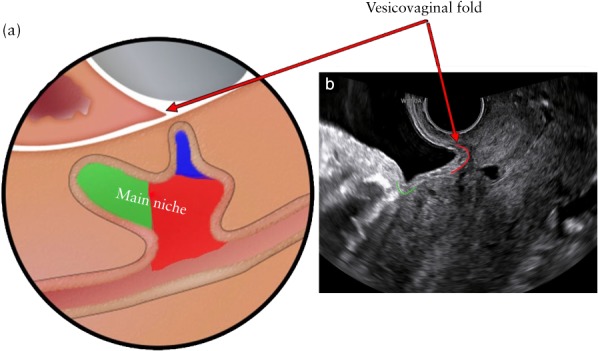

Most (83%) experts agreed that a niche should be defined as an indentation at the site of the CS scar with a depth of at least 2 mm. A niche can be subclassified as follows: (1) simple niche; (2) simple niche with one branch; (3) complex niche (with more than one branch). A branch was agreed to be a thinner part of the main niche, which is directed towards the serosa and has a width smaller than that of the main niche (86% agreement), and should always be recorded. The main niche is illustrated as the green and red area in Figure 3; the blue area illustrates a branch.

Figure 3.

Main niche and vesicovaginal fold. (a) Red and green areas represent main niche and blue area represents branch. (b) Green line indicates plica vesicouterina or uterovesical fold, while red line indicates vesicovaginal fold.

The VV fold is a triangular‐shaped fold between the bladder, the vagina and the cervix, created by placing the transvaginal probe in the anterior vaginal fornix (Figure 3). The distances between the niche and the VV fold, and the niche and the external os were considered to provide additional value for planning future surgical strategies and for research but not for basic niche evaluation (92% and 75% agreement, respectively). Measurement of the AMT was agreed to be relevant in clinical practice (92% agreement). The internal os was defined as a slight narrowing in the lower uterine segment, between the uterine corpus and the cervix at the lower boundary of the urinary bladder (73% agreement); however, the distance was considered to be irrelevant both in clinical practice and in the research setting (75% agreement)13.

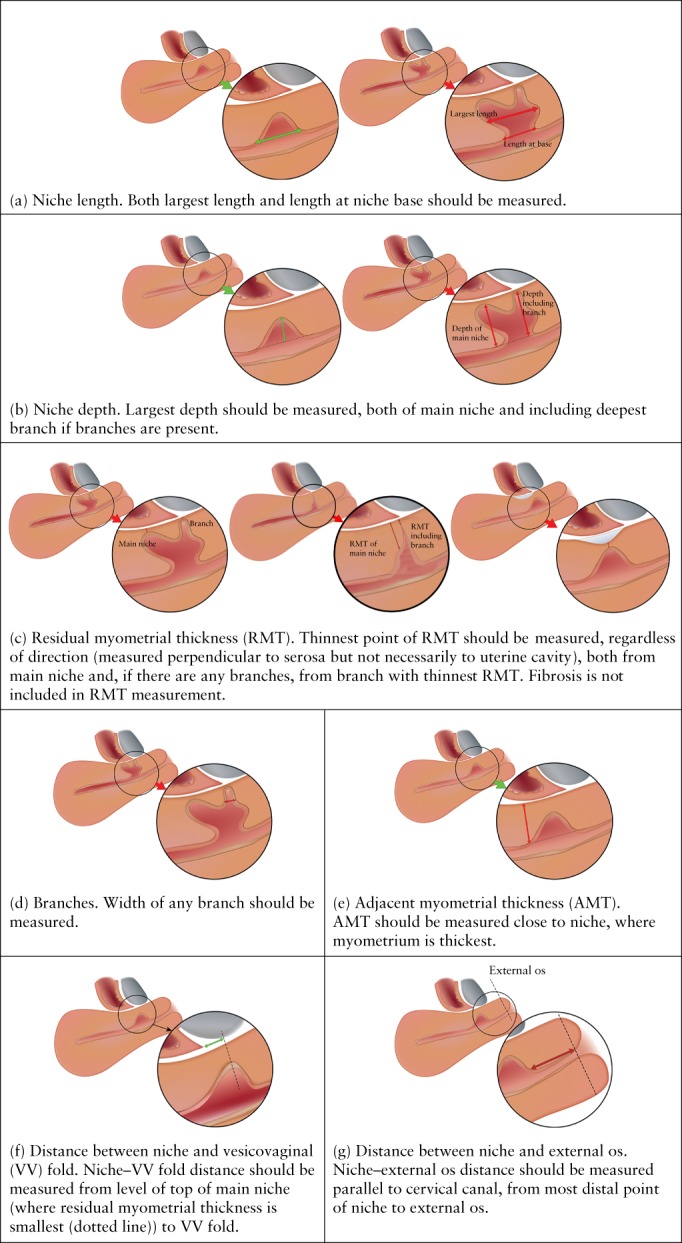

Methods of measurement

The best method to obtain the correct sagittal and transverse planes for niche measurement is described in Table 2. Clinically relevant measurements of the niche include: length, depth, RMT, width, AMT, distance between the niche and the VV fold, and distance between the niche and the external os. It was agreed that the length, depth and RMT should be measured in the sagittal plane (100% agreement). The transverse plane was considered relevant only for measurement of the width of a niche and to identify branches; it was not recommended to repeat depth and RMT measurements in this plane (100% agreement). The length, depth and width of the niche should each be measured in the plane in which it is largest (92–100% agreement); RMT should be measured in the sagittal plane in which the main niche has the smallest RMT (83% agreement). For simple niches, therefore, all measurements can be done in a single plane, while, for complex niches, more than one plane may be necessary, with length and depth being measured in the same sagittal plane, and one or two different sagittal planes being required to measure the thinnest RMT of the main niche and the thinnest RMT of the branch.

Table 2.

Summary of agreed statements after three Delphi rounds, regarding methods of uterine niche measurement

| Methods of measurement |

| Endometrium should be ignored; niche measurements are based only on myometrium |

| Correct sagittal plane to perform niche measurement depends on the measurement itself (length, depth or RMT) in case of niches with one or more branches (i.e. thinnest RMT including branch may be found in a sagittal plane other than the plane in which the main niche has its largest length and depth and thinnest RMT) |

| Transverse plane is used for only third dimension of the niche (width), not for depth or RMT |

| General ultrasound methods to be used |

| Best method to obtain correct sagittal plane for niche measurement is by starting in midsagittal plane, with good visualization of cervical canal, then moving transvaginal probe laterally to both sides |

| Best method to visualize niche in transverse plane is by starting in sagittal plane, keeping good visualization of niche while rotating transvaginal probe from sagittal to transverse plane |

| Best method to detect possible branches is in transverse plane, screening entire lower uterine segment from cervix to corpus |

| To measure uterine niche, there should be good visualization of lower uterine segment only; this applies to all uterine positions (anteversion, retroversion or stretched) |

| Position of transvaginal probe (in anterior or posterior fornix) affects correct plane for niche measurement |

| Value of additional tools |

| It is useful to vary pressure with transvaginal probe in order to achieve best plane for niche measurement |

| Use of Doppler imaging is not mandatory in standard niche measurement, but can be useful to differentiate between uterine niche and, for example, hematomas, adenomyomas, adenomyosis, fibrotic tissue |

| Gel/saline contrast sonography |

| Contrast sonography has added value in patients with uterine niche |

| There is no preference for either gel or saline |

| There is no preference for catheter used in contrast sonography |

| Best location of catheter used in contrast sonography is just in front of niche (caudal to its most distal part) or, if possible, cranial to its most proximal part, at start of gel/saline contrast infusion, then pulling catheter slowly backwards towards base of niche |

| While performing ultrasound following saline infusion, catheter can be left in front of niche |

| While performing ultrasound following gel infusion, there is no preference whether to remove catheter or leave it in front of the niche (caudal to its most distal part) |

| In case of intrauterine fluid accumulation, gel or saline infusion is not of additional value |

RMT, residual myometrial thickness.

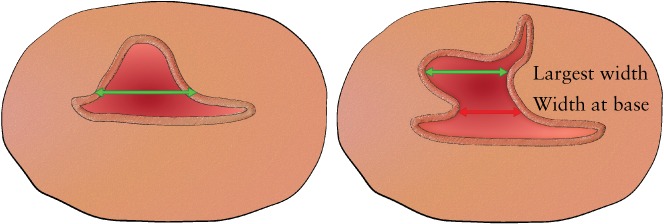

Figures 4 and 5 illustrate the various measurements, showing what should be measured and how the calipers should be positioned. According to all of the experts, if the length or the width of the main niche is larger at any point other than the niche base, two different measurements should be performed: at the base of the niche and at the point of the largest length (Figure 4a) or width (Figure 5). If visible, branches should be measured; measurements of the depth (Figure 4b) and the RMT (Figure 4c) should be made separately for the main niche and including any branch. All experts agreed that documenting features of the endometrium was not relevant to niche measurement; thus, the calipers should be placed on the border of the myometrium (for example, see Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Position of calipers for different sonographic measurements of uterine niche in the sagittal plane.

Figure 5.

Position of calipers for sonographic measurement of width of uterine niche in transverse plane. Both largest width and width at niche base should be measured.

Tips for the visualization of niches

During the Delphi procedure, various tips and tricks to improve visualization of the niche were proposed by individual experts and were added to the questions over the course of the process. It is important to have good visualization of the lower uterine segment (80% agreement). One expert tip was that the operator should be aware that TVS is a dynamic process, in which variation of the position of the probe (anterior or posterior fornix) and application of pressure using the probe can affect (either positively or negatively) visualization of the niche. Visualization of a niche that is located more proximal within the uterus in general requires more pressure, while less pressure is needed for good visualization of niches located more distally or for visualization of the VV fold. A full bladder is not obligatory for visualization of the VV fold. Doppler imaging was felt to be useful to differentiate between a niche and other uterine abnormalities (e.g. hematomas, myomas or adenomyosis), but was not considered mandatory for niche measurement.

Most (75%) experts agreed that niche evaluation with either gel or saline infusion is of additional value compared with using standard 2D ultrasonography, but no preference was expressed of one over the other. The expert panel also concluded that there need be no preference for the type of catheter used for contrast sonography, apart from one catheter for gel infusion that was considered unsuitable since it impairs visualization of the niche due to a thicker intracervical component (the ‘GIS‐Kit’). It was also considered that, if fluid is present in the uterine cavity, there is no need for additional gel or saline instillation (100% agreement).

DISCUSSION

Main findings

The modified Delphi procedure used in this study included two questionnaire rounds and one face‐to‐face meeting, resulting in consensus amongst experts for all items concerning the definition and evaluation with ultrasonography of a uterine niche. Based on the consensus findings, we formulated a definition for uterine niche and produced guidance for its various measurements, keeping these as simple and consistent as possible to facilitate their use in daily clinical practice. Only basic measurements, including niche length and depth, RMT and AMT in the sagittal plane, and niche width in the transverse plane, are considered to be essential. If there are branches, these should be reported and additional measurements are recommended. The use of gel or saline infusion is preferred over standard TVS but is not mandatory if intrauterine fluid is present. Variation in pressure generated with the transvaginal probe can optimize imaging, and Doppler imaging can be used to differentiate between a niche and other uterine abnormalities, but neither is considered mandatory.

The current consensus focused on the basic evaluation, which can be used in daily clinical practice; additional items that may be relevant for presurgical assessment or research purposes were not included.

Comparison with other studies

Although the number of published studies on uterine niche has increased over the last few years, there is no uniform, internationally recognized definition and guideline for niche evaluation. In their proposed standardized method for identifying a niche with ultrasonography, Naji et al.13 suggested classifying the appearance of a niche based on its clinical value (mild, moderate or severe scar defect) and performing measurements in three dimensions (length, width and depth) as well as measuring RMT; measurements were not further defined or specified for different niche shapes, for example in the presence of a branch or fibrotic tissue at the site of the uterine scar. Tower et al.5 proposed a classification of niches based on RMT and the RMT/AMT ratio as the only ultrasonographic features5. Our literature search confirmed a lack of detailed guidelines for niche measurement. In most previous niche studies, measurements were not described clearly and reasons for their use were not given for the types of measurement used. Given the lack of studies evaluating the accuracy and validity of various niche measurements, we decided to use a structured consensus method to produce the current recommendations. The usefulness and accuracy of our recommendations need to be confirmed in future studies.

Strengths and limitations

The use of a modified Delphi method is a strength of our study. This procedure allows experts to maintain anonymity during questionnaire rounds, preventing domination by any individual, and to revise their opinion during successive rounds. Furthermore, we composed a focus group prior to commencing the Delphi procedure, in order to optimize the validity of the questionnaire to be used in the first round. The items selected by the focus group were additionally confirmed by the expert panel. Additionally, members of the expert panel were gynecologists from all over Europe potentially with different viewpoints due to their different education and experience.

It is a limitation that the response rate in the second round decreased to 80% and only nine (60%) experts were present during the group meeting. However, consensus on the content of all 42 items concerning niche measurement was achieved in three Delphi rounds, and these items were then approved by all 15 experts who participated in the first round. Validity of the construction and accuracy of the item list used should be determined in future studies.

Future perspectives

These recommendations on detailed uterine niche evaluation are intended as a basic practical guideline for gynecologists, ultrasound examiners and researchers, with the aim of standardizing niche measurement in non‐pregnant women. In order to facilitate its use, we have designed an e‐learning module including these recommendations on which consensus was reached. The value of this e‐learning program (the eNiche study) is being assessed and these findings will be published in the future. During our Delphi procedure we identified several knowledge gaps concerning niche measurement that require future research. These include: the optimal cut‐off value for the depth of a niche to be used in defining different sizes of niche; the optimal cut‐off values of RMT and ratios of RMT/AMT or depth/RMT to define the clinical relevance of a niche; and the relevance of certain measurements that include a branch, the distance between niche and external os and the measurements of width and length if the niche base is not the largest part. The relevance of these parameters in terms of related symptoms, subfertility or problems during fertility treatment, prediction of obstetric complications in a subsequent pregnancy and prediction of treatment risks and success, needs to be elucidated. To determine the optimal timing for niche measurement after a CS, future studies are needed as data are limited. An ongoing trial with this aim is registered in the trial register (NTR6921). A previous study reported a difference in niche measurements using saline contrast sonohysterography between those made at 6–12 weeks and those at 12 months following CS26. Based on the expected duration of the scar healing process, and until future data become available, we advise evaluating a niche at least 3 months after CS. This is in line with a large ongoing study in 2290 patients (NTR5480), in which niches are measured at 3 months follow‐up after double‐ or single‐layer closure of a uterine CS scar. Also, the best timing for niche measurement during a menstrual cycle needs to be elucidated. Since intrauterine fluid is seen most frequently during the midfollicular phase, possibly under the influence of increased estradiol levels27, niche evaluation between cycle days 7 and 14 may prevent the need for any additional infusion of gel or saline. Furthermore, this allows evaluation of the existence of intrauterine fluid during this phase, which may be relevant in women who want to conceive, since this may affect implantation28, 29.

Conclusion

We have developed and describe here a uniform definition and recommendations for evaluating uterine niche in the non‐pregnant woman. Consensus was achieved, using a modified Delphi procedure, amongst European experts for all 42 items regarded as relevant for ultrasonographic niche evaluation. The relationship between the morphological characteristics and measurements of a niche with clinical outcome has yet to be described.

Disclosure

J.H., I.J. and S.S. declare their involvement in the Dutch 2Close study, ‘The cost effectiveness of double layer closure of the caesarean (uterine) scar in the prevention of gynecological symptoms in relation to niche development’. This is a randomized controlled trial funded by ZonMw, an organization for health research and development in The Netherlands.

REFERENCES

- 1. Vikhareva Osser O, Valentin L. Clinical importance of appearance of cesarean hysterotomy scar at transvaginal ultrasonography in nonpregnant women. Obstet Gynecol 2011; 117: 525–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Naji O, Wynants L, Smith A, Abdallah Y, Saso S, Stalder C, Van Huffel S, Ghaem‐Maghami S, Van Calster B, Timmerman D, Bourne T. Does the presence of a Caesarean section scar affect implantation site and early pregnancy outcome in women attending an early pregnancy assessment unit? Hum Reprod 2013; 28: 1489–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bij de Vaate AJ, Brolmann HA, van der Voet LF, van der Slikke JW, Veersema S, Huirne JA. Ultrasound evaluation of the Cesarean scar: relation between a niche and postmenstrual spotting. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011; 37: 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van der Voet LF, Bij de Vaate AM, Veersema S, Brolmann HA, Huirne JA. Long‐term complications of caesarean section. The niche in the scar: a prospective cohort study on niche prevalence and its relation to abnormal uterine bleeding. BJOG 2014; 121: 236–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tower AM, Frishman GN. Cesarean scar defects: an underrecognized cause of abnormal uterine bleeding and other gynecologic complications. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2013; 20: 562–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schepker N, Garcia‐Rocha GJ, von Versen‐Hoynck F, Hillemanns P, Schippert C. Clinical diagnosis and therapy of uterine scar defects after caesarean section in non‐pregnant women. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2015; 291: 1417–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van der Voet LF, Vervoort AJ, Veersema S, BijdeVaate AJ, Brolmann HA, Huirne JA. Minimally invasive therapy for gynaecological symptoms related to a niche in the caesarean scar: a systematic review. BJOG 2014; 121: 145–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bij de Vaate AJ, van der Voet LF, Naji O, Witmer M, Veersema S, Brolmann HA, Bourne T, Huirne JA. Prevalence, potential risk factors for development and symptoms related to the presence of uterine niches following Cesarean section: systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2014; 43: 372–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Glavind J, Madsen LD, Uldbjerg N, Dueholm M. Cesarean section scar measurements in non‐pregnant women using three‐dimensional ultrasound: a repeatability study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2016; 201: 65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baranov A, Gunnarsson G, Salvesen KA, Isberg PE, Vikhareva O. Assessment of Cesarean hysterotomy scar in non‐pregnant women: reliability of transvaginal sonography with and without contrast enhancement. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016; 47: 499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fiocchi F, Petrella E, Nocetti L, Curra S, Ligabue G, Costi T, Torricelli P, Facchinetti F. Transvaginal ultrasound assessment of uterine scar after previous caesarean section: comparison with 3T‐magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging. Radiol Med 2015; 120: 228–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van der Voet LLF, Limperg T, Veersema S, Timmermans A, Bij de Vaate AMJ, Brolmann HAM, Huirne JAF. Niches after cesarean section in a population seeking hysteroscopic sterilization. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2017; 214: 104–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Naji O, Abdallah Y, Bij De Vaate AJ, Smith A, Pexsters A, Stalder C, McIndoe A, Ghaem‐Maghami S, Lees C, Brolmann HA, Huirne JA, Timmerman D, Bourne T. Standardized approach for imaging and measuring Cesarean section scars using ultrasonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2012; 39: 252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs 2000; 32: 1008–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ 1995; 311: 376–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vervoort AJMW, Van der Voet LF, Hehenkamp WJK, Thurkow AL, van Kesteren PJM, Quartero H, Kuchenbecker W, Bongers M, Geomini P, de Vleeschouwer LHM, van Hooff MHA, van Vliet H, Veersema S, Renes WB, Oude Rengerink K, Zwolsman SE, Brölmann HAM, Mol BWJ, Huirne JAF. Hysteroscopic resection of a uterine caesarean scar defect (niche) in women with postmenstrual spotting: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG 2018; 125: 326–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hsu C, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. PARE 2007; 12: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Janssen PF, Brolmann HA, Huirne JA. Recommendations to prevent urinary tract injuries during laparoscopic hysterectomy: a systematic Delphi procedure among experts. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2011; 18: 314–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Allison SJ, Horrow MM, Lev‐Toaff AS. Pearls and pitfalls in sonohysterography. Ultrasound Clinics 2010; 5: 195–207. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vikhareva Osser OV, Jokubkiene L, Valentin L. High prevalence of defects in Cesarean section scars at transvaginal ultrasound examination. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009; 34: 90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bij de Vaate MAJ, Linskens IH, van der Voet LF, Twisk JW, Brolmann HA, Huirne JA. Reproducibility of three‐dimensional ultrasound for the measurement of a niche in a caesarean scar and assessment of its shape. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2015; 188: 39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Giral E, Capmas P, Levaillant JM, Berman A, Fernandez H. Interest of saline contrast sonohysterography for the diagnosis of cesarean scar defects. Gynecol Obstet Fertil 2015; 43: 693–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fabres C, Aviles G, De La Jara C, Escalona J, Muñoz JF, Mackenna A, Fernández C, Zegers‐Hochschild F, Fernández E. The Cesarean delivery scar pouch. J Ultrasound Med 2003; 22: 695–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. GRADE Handbook . http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/app/handbook/handbook.html [Updated October 2013].

- 25.ATLAS.ti Version 8.0 B, 2017. Scientific Sortware Development, GmBH, Berlin.

- 26. van der Voet LF, Jordans IPM, Brolmann HAM, Veersema S, Huirne JAF. Changes in the uterine scar during the first year after a Caesarean section: a prospective longitudinal study. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2018; 83: 164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reed BG, Carr BR. The normal menstrual cycle and the control of ovulation [Updated 2015 May 22] In Endotext [Internet]: Comprehensive FREE Online Endocrinology Book, De Groot LJ, Chrousos G, Dungan K, Feingold KR, Grossman A, Hershman JM, Koch C, Korbonits M, McLachlan R, New M, Purnell J, Rebar R, Singer F, Vinik A, eds). MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth (MA), 2000–2015. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279054/. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vervoort AJ, Uittenbogaard LB, Hehenkamp WJ, Brolmann HA, Mol BW, Huirne JA. Why do niches develop in Caesarean uterine scars? Hypotheses on the aetiology of niche development. Hum Reprod 2015; 30: 2695–2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. He RH, Gao HJ, Li YQ, Zhu XM. The associated factors to endometrial cavity fluid and the relevant impact on the IVF‐ET outcome. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2010; 8: 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Supporting information

Appendices S1–S4 and Table S1 may be found in the online version of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Hans Ket (VUmc) for his assistance in our literature search. We also thank all members of the focus group and the members of the expert panel for their time and effort.

This article has been selected for Journal Club. Click here to view slides and discussion points.

This article has been selected for Journal Club. Click here to view slides and discussion points.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendices S1–S4 and Table S1 may be found in the online version of this article.