Abstract

Objective

Bipolar disorder has a wide range of clinical manifestations which may progress over time. The aim of this study was to test the applicability of a clinical staging model for bipolar disorder and to gain insight into the nature of the variables influencing progression through consecutive stages.

Methods

Using retrospectively reported longitudinal life chart data of 99 subjects from the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network Naturalistic Follow‐up Study, the occurrence, duration and timely sequence of stages 2‐4 were determined per month. A multi‐state model was used to calculate progression rates and identify determinants of illness progression. Stages 0, 1 and several other variables were added to the multi‐state model to determine their influence on the progression rates.

Results

Five years after onset of BD (stage 2), 72% reached stage 3 (recurrent episodes) and 21% had reached stage 4 (continuous episodes), of whom 8% recovered back to stage 3. The progression from stage 2 to 3 was increased by a biphasic onset for both the depression‐mania and the mania‐depression course and by male sex.

Conclusions

Staging is a useful model to determine illness progression in longitudinal life chart data. Variables influencing transition rates were successfully identified.

Keywords: biphasic onset, bipolar disorder, male sex, mood disorders, multi‐state model, staging, staging models

1. INTRODUCTION

Bipolar disorder (BD) has a wide range of clinical manifestations with depressive, hypomanic and manic episodes next to euthymic intervals.1 Classification systems such as DSM‐52 and ICD‐103 have led to a more unified definition of criteria for mood disorders. Still, considerable heterogeneity remains in the longitudinal course of BD, ranging from a single manic episode to frequent alternating mood episodes or even chronic illness.

Staging models have the potential to further classify psychiatric disorders in relationship to their differential long‐term course. Fava and Kellner4 were the first to emphasize the importance of staging in psychiatry, which was then further promoted by McGorry et al.5 Based on McGorry's model for psychotic and severe mood disorders, Berk et al6 proposed a staging model for bipolar disorders, largely defined by the occurrence and recurrence of mood episodes. In the staging model by Berk et al, stage 0 (at risk), stage 1 (prodromal), stage 2 (first episode), stage 3 (recurrent episodes), and stage 4 (chronic, unremitting illness) are distinguished. Kapczinski et al7 proposed an alternative staging model, focusing on inter‐episodic functional impairment and potential biomarkers. For this study, we decided to focus on the model by Berk et al6 for which Kupka & Hillegers8 proposed some modifications, defining initial depressive episodes without a history of (hypo)mania as a prodromal stage of bipolar disorder, as was also proposed by Duffy et al.9 For the current study, we further refined this staging model (see Table 2 and Appendix 1).

Table 2.

Staging modela

| Stage 0 | Increased risk (as defined by a 1st degree relative with bipolar disorder); no psychiatric symptoms |

| Stage 1 | Non‐specific psychiatric symptoms or depressive episode(s) |

| A | Increased risk and non‐specific psychiatric symptoms, no history of depressive episode(s) |

| B | Increased risk and bipolar‐specific prodromal symptoms, no history of depressive episode(s) |

| C | Increased risk, with a first major depressive episode |

| D | Increased risk, with recurrent major depressive episodes |

| Stage 2 | First episode that qualifies for diagnosis of bipolar disorder |

| A | First manic episode (diagnosis BP‐I) without previous history of depressive episode(s) and without depression immediately preceding or following the first manic episode |

| B | First hypomanic (diagnosis BP‐II) or manic episode (diagnosis BP‐I) without previous history of depressive episode(s) but with depression immediately preceding or following first (hypo)manic episode |

| C | First hypomanic (diagnosis BP‐II) or manic episode (dx BP‐I) with previous history of depressive episode(s), with or without depression immediately preceding or following first (hypo)manic episode |

| D | First depression after hypomanic episode (diagnosis BP‐II) |

| Stage 3 | Recurrence of any depressive, hypomanic, or manic/mixed episode |

| A | Recurrence of subsyndromal depressive or manic symptoms after the diagnosis of bipolar disorder |

| B | Recurrent bipolar disorder (recurrence of any depressive, hypomanic, or manic/mixed episode) and with full symptomatic and functional recovery between episodes |

| C | Recurrent bipolar disorder (recurrence of any depressive, hypomanic, or manic/mixed episode), with subsyndromal symptoms and/or impaired functioning between episodes |

| Stage 4 | Persistent unremitting illness; chronic (>2 years) depressive, manic or mixed episodes, including rapid cycling |

| A | Chronic depressive, manic or mixed episode(s), without symptomatic and functional recovery for 2 years |

| B | Rapid cycling (≥4 mood episodes/year), without symptomatic and functional recovery for 2 years |

By Kupka & Hillegers (8), based on Berk et al.(6), Kapczinski et al.(33) and Duffy et al. (9).

Unlike other fields of medicine, staging models have not yet been widely implemented in psychiatry. First, the models’ applicability must be assessed. The validity of applying a clinical staging model for unipolar depression has been demonstrated.10 Staging models for bipolar disorder have not yet been validated in longitudinal data sets. Longitudinal illness course data of the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network Naturalistic Follow‐up Study (SFBN‐NFS)11 provided a unique opportunity to apply a staging model on patient data. The main objective of the current study was to assess the applicability of a clinical staging model for BD. The second aim was to gain insight in the natural progression through the stages of BD in the first 5 years after onset of BD (ie, entry of stage 2) and to investigate whether illness progression was influenced by items considered to be of clinical significance, eg age at onset, sex, mono‐ or biphasic initial episode, or a first degree relative with BD.12

2. METHODS

2.1. Study sample

Participants of the Dutch site of the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network Naturalistic Follow‐up Study (SFBN‐NFS) of whom a comprehensive retrospective LifeChart (LCM‐p)13 was available (n = 99) were included in the study. Subjects were recruited from psychiatric outpatient clinics between 1995 and 2001. In order to get a broad coverage of the bipolar spectrum, few restrictions were applied to subjects before entering the SFBN‐NFS. Inclusion criteria were age over 18 years and diagnosis of BD I, II or Not Otherwise Specified according to the DSM‐IV—confirmed by a clinical interview including SCID14 at study entry. Only subjects with active substance abuse requiring additional treatment were excluded. The methodology of the SFBN‐NFS was published elsewhere.11 We received approval for SFBN‐NFS from the IRB of the University Medical Center Utrecht, Netherlands, and all patients gave written informed consent (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants (n = 99)

| Descriptivesa | n (%)[range] |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 55 (55.6) |

| Male | 44 (44.4) |

| Parental diagnosis bipolar disorder | 22 (22.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Married or living together | 46 (46.5) |

| Single | 34 (34.3) |

| Divorced or widowed | 19 (19.2) |

| Educational level | |

| ≤high school | 46 (26.4) |

| >high school | 53 (53.6) |

| Working status | 86 (86.9) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Bipolar I | 88 (88.9) |

| Bipolar II | 11 (11.1) |

| Childhood abuse | |

| Physical | 7 (7.1) |

| Sexual | 9 (9.1) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Anxiety disorder | 40 (40.4) |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 22 (22.2) |

| Drug abuse | 9 (9.1) |

| Pharmacotherapy bipolar disorder | 83 (83.8) |

| Suicide attempts, prevalence | 22 (22.2) |

| During 5 years under study | |

| Age at onset, years (SD) | 29.17 (10.2) [14.0‐53.0] |

| Number of mood episodes | |

| Depressed, median | 2 (0‐16) |

| Manic/hypomanic, median | 2 (1‐15) |

Up to inclusion.

Of each participant, a retrospective life chart (LCM‐r) ranging from onset of first mood symptoms until study entry was reconstructed, according to the guidelines in the NIMH LCM‐manual,15 resulting in a graphic representation of the past longitudinal illness course, including initial prodromal symptoms. The severity rating of mood episodes was based on both the severity of manic and depressive symptoms and the degree of associated functional impairment.16 Per these guidelines, all available information from clinical and personal records and repeated clinical interviews was collected by a trained research clinician. The occurrence and severity of mood episodes were determined for every consecutive month.

2.2. Application of the clinical staging model

Using duplicates of the original hand‐completed LCM‐r graphics for all 99 subjects, three clinicians (AM, UK, RK) independently assigned the occurrence, duration and temporal sequence of stages for each month after initial symptoms, using the modified staging model by Berk et al6, 8 (Table 2), and further refined for application to life chart data by consensus among clinical investigators, see Appendix 1. In summary, the model consists of five stages (0‐4) which are each divided into sub‐stages (eg A, B, C, D). Both stages and sub‐stages were rated. In our model, subjects remained in the assigned stage after remission of the episode until transition to a consecutive stage.

Since we used life charts covering the period from first symptoms until study entry (range 10 months to 45 years), the overall course of each mood episode was known at the time the stages were assigned. We decided to use a prospectively oriented reconstruction, ie if an episode would eventually last 2 years or more, stage 4 (chronic course) was only assigned after these 2 years, after first recording all applicable preceding stages. Functional recovery was defined as return of mood to baseline for at least 2 months.

Since our main interest covered illness progression during the first 5 years after the onset of BD, data were right‐censored 60 months after onset of BD (stage 2) or earlier if the time between onset and inclusion was less than 60 months (N = 13), resulting in a maximum of 60 data‐points per subject. The interrater reliability was calculated for the full stages, ie without subgroups.

2.3. Statistical analyses

The data were prepared for statistical analysis by a multi‐state model. As not all subjects experienced each subsequent stage, subjects could enter the study in a higher stage and/or skip stages. By definition, backward transition was only possible from stage 4 to 3. We distinguished the transition from stage 2 to 3 as primary entry of stage 3 (3.1); conversion from stage 4 back to stage 3 was defined as secondary entry of stage 3 (3.2).

A multi‐state model was fitted to the data enabling calculation of the probability of the progression to each stage, as demonstrated by Keown‐Stoneman et al.17 The mstate package in R was used to construct this multi‐state model18 in order to represent all the in‐between stages instead of treating such stages as covariates. In this model, each state corresponds with a stage, starting at the time of onset of BD. A Markov model with stratified hazards was used both with and without covariates. This model is based on the assumption that the transition rate is independent of both the length of stay in the current state (sojourn time) and which states were visited prior to the current state.19

The following covariates were added: having at least one parent with bipolar disorder (stage 0); prodromal subsyndromal depressive or manic symptoms (stage 1); type of bipolar onset (stage 2). A monophasic onset, (single mania or depression leading to diagnosis), was compared to a biphasic onset, (depression immediately followed by (hypo)mania or mania immediately followed by depression). Sex and age at onset were added (early onset ≤18; intermediate or late bipolar onset >18).20, 21, 22, 23

3. RESULTS

A total of 99 subjects were included in the current study. Of these subjects, 55 were female. At SFBN‐NFS study entry, 88 subjects met the criteria for bipolar I disorder and 11 met the criteria for bipolar II. The average age at onset of BD, indicating the age when a patient first qualified for the diagnosis of bipolar disorder (stage 2), as in having a first manic episode, a depression after a hypomania or a hypomania after depression, was 29.17 (10.2) [14.0‐53.0].

The inter‐rater reliability of assigning stages to the LCM‐r, was 0.69 using a Fleiss Kappa, signifying high concordance among three raters.24

Before the onset of bipolar disorder, eleven subjects (12%) had fulfilled criteria for stage 0, defined by having at least one bipolar parent. Seventy‐five subjects (75%) had experienced a period of prodromal symptoms (stage 1)—non‐specific psychiatric symptoms or depressive episode(s)—prior to progression through stage 2.

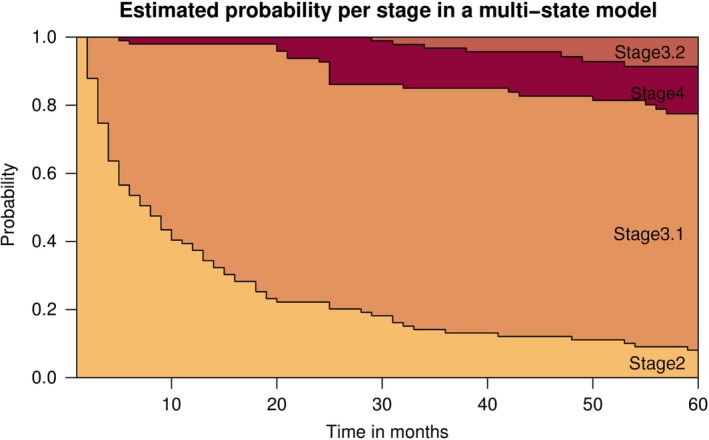

Figure 1 visualizes the progression through the stages of the multi‐state model. As time progresses, the probability of remaining in stage 2 decreases, whereas the probability for transition to stages 3.1, 4 and 3.2 increase.

Figure 1.

Probability of reaching stages in the first 5 years after onset of BD. Subjects were diagnosed with bipolar disorder (stage 2 or higher) at time 0 [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The average duration subjects spent in stage 0 was 28.3 years (SD 10.2) and for stage 1 3.5 years (SD 4.5). In the 5 years after onset of BD, patients spent an average of 1.2 years (SD 1.5) in stage 2. The first entry of stage 3 lasted an average of 3.2 years (SD 1.5), stage 4 1.6 years (SD 1.4), and a second entry of stage 3 1.8 years (SD 1.0). Five years after onset of BD, 7% of the subjects still remained in stage 2. 72% had reached stage 3 and 13% stage 4, with 8% recovering to stage 3 (3.2) within the time frame. No subjects reached stage 4 more than once.

In adding covariates to our data, their influence on the transition hazards was calculated (see Table 3). The hazard ratio reflects the increase in transition rate for a specified covariate within a group, for example male vs female sex. A biphasic onset for both mania‐depression (MD) or depression‐mania (DM) increased the progression rate from stage 2 to 3 (HR 2.68 and 3.34) as well as male sex (HR 1.78).

Table 3.

Influence of covariates on the transition hazards

| Covariate | Hazard ratio | 95% confidence interval | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transition stage 2 to 3 | |||

| Parent with BD: y vs n | 0.90 | [0.54‐1.52] | 0.70 |

| Prodromal: y vs n | 1.05 | [0.59‐1.87] | 0.87 |

| Onset: Mono vs MD | 2.68 | [1.50‐4.80] | <0.01a |

| Onset: Mono vs DM | 3.34 | [1.85‐6.03] | <0.01a |

| Age of onset: ≤18 vs >18 | 0.75 | [0.44‐1.27] | 0.28 |

| Sex: m vs f | 1.78 | [1.14‐2.77] | 0.01a |

| Transition stage 2 to 4 | |||

| Parent with BD: y vs n | 0.00 | [0.00‐∞] | >0.99 |

| Prodromal: y vs n | 0.00 | [0.00‐∞] | >0.99 |

| Onset: Mono vs MD | 0.00 | [0.00‐∞] | >0.99 |

| Onset: Mono vs DM | 4.01 × 106 | [0.00‐∞] | >0.99 |

| Age of onset: ≤18 vs >18 | 0.15 | [0.01‐2.82] | 0.21 |

| Sex: m vs f | 0.00 | [0.00‐∞] | >0.99 |

| Transition stage 3 to 4 | |||

| Parent with BD: y vs n | 0.36 | [0.08‐1.59] | 0.17 |

| Prodromal: y vs n | 0.48 | [0.13‐1.79] | 0.27 |

| Onset: Mono vs MD | 0.68 | [0.18‐2.56] | 0.57 |

| Onset: Mono vs DM | 1.61 | [0.44‐5.94] | 0.47 |

| Age of onset: ≤18 vs >18 | 0.53 | [0.20‐1.41] | 0.21 |

| Sex: m vs f | 1.16 | [0.45‐2.97] | 0.76 |

| Transition stage 4 to 3 | |||

| Parent with BD: y vs n | 2.74 | [0.08‐94.37] | 0.58 |

| Prodromal: y vs n | 0.24 | [0.01‐5.02] | 0.35 |

| Onset: Mono vs MD | 0.43 | [0.04‐4.41] | 0.48 |

| Onset: Mono vs DM | 0.16 | [0.00‐5.62] | 0.31 |

| Age of onset: ≤18 vs >18 | 2.39 | [0.16‐36.83] | 0.53 |

| Sex: m vs f | 0.46 | [0.08‐3.80] | 0.54 |

BD, Bipolar Disorder; Mono, monophasic; MD, mania‐depression (biphasic onset); DM, depression mania (biphasic onset).

Parameter estimates from a Markov model with stratified hazards. Significance P ≤ 0.05.

4. DISCUSSION

We tested the applicability of a staging model for BD based on episode recurrence as proposed by Berk et al6 and assessed the progression of BD in the first 5 years after onset of first symptoms that indicate the presence of BD. Experts have conceptualized staging in different ways, and the proposed model by Berk et al is one such model. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first application of a clinical staging model for BD to real longitudinal patient data. A time frame of 5 years after onset of BD was chosen, since progression in the first years specifically favors early intervention and sheds light upon factors influencing course and outcome.

Subjects progressed through the stages in different ways in these first 5 years. We used comprehensive retrospective life charts of psychiatric outpatients to calculate the probability of progression from one stage to the next and to assess the impact of several covariates. We assessed the first 5 years after onset of BD, defined as the point at which the subject retrospectively qualified for the diagnosis of BD‐ according to the adjusted model by Kupka and Hillegers. This could be either a manic episode, a hypomanic episode after a depression or a depression after a hypomanic episode. Five years after the onset of BD (stage 2), the majority of subjects had progressed to stage 3, indicating the recurrent nature of the disorder in the study population. About one‐fifth (21%) reached stage 4, and approximately a third of those recovered to a non‐chronic state (stage 3) within the observation period. Stage reversal was inherent upon the study definition of remission, defined as a symptom free interval of more than 2 months, allowing for termination of stage 4. No subject reached stage 4 more than once during this period. Although it remains unclear whether BD must be conceptualized as a neuroprogressive condition,25 our study has added to the evidence of general illness progression to more advanced stages as recently summarized by Kessing et al.26

We assessed the influence of covariates on the transition rate, ie the rate at which subjects progressed through the stages. Biphasic over monophasic episodes at the time at onset of BD were the strongest predictor of a faster transition from stage 2 to 3, irrespective of the order of the directionality of the mood episode, ie depression‐mania and mania‐depression subjects. By definition, subjects with mania followed by depression enter stage 3. Our findings are in line with Turvey et al,27 finding a positive relation between poor prognosis and poly‐phasic first episodes.

Several epidemiological studies reported no difference in the prevalence of BD between sexes (4‐6), although one study found women to be at higher risk for recurrence of mood episodes (5). However, in the first 5 years, our findings indicate a higher transition hazard for stage 2 to 3 for males, underlining the importance of staging models in studies investigating sex differences in BD.

Several studies28, 29 have shown an increased risk for developing any mood disorder in offspring of bipolar patients. Still, once BD occurred, we found no difference in transition hazard between the groups with and without a parent with BD. Although a relationship between an early age at onset and a poorer prognosis has been widely reported,22, 23, 30 we found no difference in transition rate for the group with onset ≤ age 18. Transitions from stage 2 to 4 and between stage 3 and 4 were not significantly influenced by any of the tested variables, although the group that transitioned from 2 to 4 was too small to draw any final conclusions.

The main strengths of our study are the unique set of meticulously gathered longitudinal illness course data, at that time collected without any staging model in mind, and the use of current advanced statistical techniques. Since retrospective life chart data were used, dropout during the period under study was no concern.

Our study has several limitations. Our dataset consisted of 99 subjects, resulting in a limited amount of covariates to be tested. Due to recall bias, symptoms covering early stages may have been underestimated. Inevitably, subjects at risk (stage 0) experiencing prodromal symptoms (stage 1) but not progressing to syndromal BD (stage 2) were not included in the SFBN‐NFS study. Moreover, the patient sample may not be representative for BD patients who are not treated in a specialized setting. Also we did not account for treatments that may have influenced the course of illness, and thus studied a naturalistic rather than a natural course. Similarly, the influence of common comorbidities of bipolar disorder, including alcohol and substance abuse, or anxiety disorder, were not considered. Psychiatric comorbidity has been associated with increased bipolar illness burden and future staging studies should attempt to ascertain temporal relationship in staging transitions.31, 32 Lastly, we chose a multi‐state model with a Markov assumption to analyze our data, considering transitions as independent of duration and previous episodes. In applying a frailty factor to a cox‐regression model, Kessing et al33 was able to relate episodes as dependent upon previous episodes, accounting for sensitization as suggested by the kindling model. However, this method is not yet available for multistate models. The disadvantage of the multi‐state model approach is that it cannot handle continuous internal covariates as states unless they are first transformed into categories, as they must be represented by discrete states. Dimensional approaches are needed to refine the methodology for staging of BD, which should be considered a multidimensional disorder in which (hypo)manic, mixed, and depressive states are variants of the same disorder, distinguished by severity of individual symptoms and therapeutic response.

One of the core controversies about clinical staging is whether it is meaningful when understanding the underlying pathophysiology is limited and biomarkers are lacking.34 However, our study shows that application of a staging model based on the clinical course does provide new insights into illness progression thereby providing a valid framework in which the influence of different variables or biomarkers on the illness progression can be investigated.

Although the current study may predict the course of BD on a group level, predictions on a personal level cannot be made yet, clinical profiling being the next step towards a more personalized diagnosis and treatment. For example, in earlier stages, the disorder may respond well to monotherapy,35, 36, 37 with better compliance and fewer side effects, while later stages may require more complex treatments. Awareness of a staging model could improve interventions during prodromal stages, often called the ‘window of opportunity’ to minimize or prevent further episodes.

In conclusion, our results suggest that clinical staging is a useful model to describe the progression of BD. Application of a staging model on longitudinal illness course data is possible and informative. Future studies are recommended, using larger samples enabling the study of sub‐stages and other covariates, to further refine the predictive power of this model. This may ultimately lead to a staging model that is useful for prediction of progression of BD in clinical practice.

Supporting information

van der Markt A, Klumpers UMH, Draisma S, et al. Testing a clinical staging model for bipolar disorder using longitudinal life chart data. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21:228‐234. 10.1111/bdi.12727

REFERENCES

- 1. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic‐Depressive Illness: Bipolar Disorders and Recurrent Depression, 2nd edn New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Diagnostic And Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM‐5 . Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Print. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization . The ICD‐10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fava GA, Kellner R. Staging: a neglected dimension in psychiatric classification. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;87:225‐230. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McGorry PD, Hickie IB, Yung AR, Pantelis C, Jackson HJ. Clinical staging of psychiatric disorders: a heuristic framework for choosing earlier, safer and more effective interventions. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:616‐622. 10.1111/j.1440-1614.2006.01860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berk M, Conus P, Lucas N, et al. Point of View Setting the stage: from prodrome to treatment resistance in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:671‐678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kapczinski F, Magalhães PVS, Balanzá‐Martinez V, et al. Staging systems in bipolar disorder: an International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force Report. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130:354‐363. 10.1111/acps.12305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kupka RW, Hillegers MH. Staging and profiling in bipolar disorders. Tijdschr Psychiatr. 2012;54:949‐956. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23138622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Duffy A. Toward a comprehensive clinical staging model for bipolar disorder: integrating the evidence. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59:659‐666. https://doi.org/25702367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Verduijn J, Milaneschi Y, van Hemert AM, et al. Clinical staging of major depressive disorder: an empirical exploration. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:1200‐1208. 10.4088/JCP.14m09272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leverich GS, Nolen WA, Rush AJ, et al. The Stanley Foundation bipolar treatment outcome network: I longitudinal methodology. J Affect Disord. 2001;67:33‐44. 10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00430-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sachs GS. Strategies for improving treatment of bipolar disorder: integration of measurement and management. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2004;110(422 SUPPL.):7‐17. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leverich GS, Post RM. Life charting of affective disorders. CNS Spectr. 1998;3:21‐37. [Google Scholar]

- 14. First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV Axis I Disorders‐Patient Edition (SCID‐I/P). New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Leverich GSW, Post RM. The NIMH Life Chart Manual™ for recurrent affective illness. 2002:32.

- 16. Denicoff KD, Leverich GS, Nolen WA, et al. Validation of the prospective NIMH‐Life‐Chart Method (NIMH‐LCM‐p) for longitudinal assessment of bipolar illness. Psychol Med. 1921;2000:1391‐1397. 10.1017/S0033291799002810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Keown‐Stoneman CD, Horrocks J, Darlington GA, Goodday S, Grof P, Duffy A. Multi‐state models for investigating possible stages leading to bipolar disorder. Int J bipolar Disord. 2015;3:5 10.1186/s40345-014-0019-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. de Wreede LC, Fiocco M, Putter H. The mstate package for estimation and prediction in non‐ and semi‐parametric multi‐state and competing risks models. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2010;99:261‐274. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mills M. Introducing Survival and Event History Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd; 2011. 10.4135/9781446268360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Perlis RH, Dennehy EB, Miklowitz DJ, et al. Retrospective age at onset of bipolar disorder and outcome during two‐year follow‐up: results from the STEP‐BD study. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11:391‐400. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00686.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baldessarini RJ, Salvatore P, Khalsa HMK, Imaz‐Etxeberria H, Gonzalez‐Pinto A, Tohen M. Episode cycles with increasing recurrences in first‐episode bipolar‐I disorder patients. J Affect Disord. 2012;36:149‐154. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cate Carter TD, Mundo E, Parikh SV, Kennedy JL. Early age at onset as a risk factor for poor outcome of bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:297‐303. 10.1016/S0022-3956(03)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bellivier F, Golmard J‐L, Rietschel M, et al. Age at onset in bipolar I affective disorder: further evidence for three subgroups frank. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:999‐1001. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. The measurement of Interrater agreement. 2003. 10.1002/0471445428.ch18. [DOI]

- 25. Passos IC, Mwangi B, Vieta E, Berk M, Kapczinski F. Areas of controversy in neuroprogression in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;134:91‐103. 10.1111/acps.12581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kessing LV, Andersen PK. Evidence for clinical progression of unipolar and bipolar disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135:51‐64. 10.1111/acps.12667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Turvey CL, Coryell WH, Solomon DA, et al. Long‐term prognosis of bipolar I disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;99:110‐119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gottesman II, Laursen TM, Bertelsen A, Mortensen PB. Severe mental disorders in offspring with 2 psychiatrically ill parents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:252‐257. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Duffy A, Horrocks J, Doucette S, Keown‐Stoneman C, McCloskey S, Grof P. The developmental trajectory of bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204:122‐128. 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.126706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schulze TG, Müller DJ, Krauss H, et al. Further evidence for age of onset being an indicator for severity in bipolar disorder [2]. J Affect Disord. 2002;68:343‐345. 10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Levander E, Frye MA, McElroy S, et al. Alcoholism and anxiety in bipolar illness: differential lifetime anxiety comorbidity in bipolar I women with and without alcoholism. J Affect Disord. 2007;101:211‐217. 10.1016/j.jad.2006.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Frye MA, Altshuler LL, McElroy SL, et al. Gender differences in prevalence, risk, and clinical correlates of alcoholism comorbidity in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:883‐889. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kessing LV, Olsen EW, Andersen PK. Recurrence in affective disorder: analyses with frailty models. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:404‐411. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Malhi GS, Rosenberg DR, Gershon S. Staging a protest!. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16:776‐779. 10.1111/bdi.12254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Swann AC, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Dilsaver SC, Morris DD. Differential effect of number of previous episodes of affective disorder on response to lithium or divalproex in acute mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1264‐1266. 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Berk M, Kapczinski F, Andreazza AC, et al. Pathways underlying neuroprogression in bipolar disorder: focus on inflammation, oxidative stress and neurotrophic factors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:804‐817. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goi PD, Bücker J, Vianna‐Sulzbach M, et al. Pharmacological treatment and staging in bipolar disorder: evidence from clinical practice. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2015;37:121‐125. 10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials