Abstract

Background

It is unclear whether functional outcomes improve or deteriorate with age following surgery for Hirschsprung's disease. The aim of this cross‐sectional study was to determine the long‐term functional outcomes and quality of life (QoL) in patients with Hirschsprung's disease.

Methods

Patients with pathologically proven Hirschsprung's disease older than 7 years were included. Patients with a permanent stoma or intellectual disability were excluded. Functional outcomes were assessed according to the Rome IV criteria using the Defaecation and Faecal Continence questionnaire. QoL was assessed by means of the Child Health Questionnaire Child Form 87 or World Health Organization Quality of Life questionnaire 100. Reference data from healthy controls were available for comparison.

Results

Of 619 patients invited, 346 (55·9 per cent) responded, with a median age of 18 (range 8–45) years. The prevalence of constipation was comparable in paediatric and adult patients (both 22·0 per cent), and in patients and controls. Compared with controls, adults with Hirschsprung's disease significantly more often experienced straining (50·3 versus 36·1 per cent; P = 0·011) and incomplete evacuation (47·4 versus 27·2 per cent; P < 0·001). The prevalence of faecal incontinence, most commonly soiling, was lower in adults than children with Hirschsprung's disease (16·8 versus 37·6 per cent; P < 0·001), but remained higher than in controls (16·8 versus 6·1 per cent; P = 0·003). Patients with poor functional outcomes scored significantly lower in several QoL domains.

Conclusion

This study has shown that functional outcomes are better in adults than children, but symptoms of constipation and soiling persist in a substantial group of adults with Hirschsprung's disease. The persistence of defaecation problems is an indication that continuous care is necessary in this specific group of patients.

Introduction

Hirschsprung's disease (HD) is a congenital absence of ganglion cells of the distal bowel that in most instances presents with severe functional obstruction shortly after birth. Following diagnosis, resection is usually performed to remove the aganglionic bowel and to restore continuity. Although many patients may attain normal bowel function following surgery, defaecation disorders, such as constipation or faecal incontinence, can persist1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11.

It has been postulated that functional outcomes improve as patients grow older, especially after reaching adolescence5, 6, 7. Other studies, however, have drawn attention to the fact that long‐term outcomes of HD in adulthood are far from satisfactory2, 3, 4. Indeed, one study3 found that defaecation problems actually deteriorated after the patients reached adulthood. Unfortunately, a lack of data on healthy controls hinders interpretation of the majority of these studies.

Persistent defaecation disorders, such as constipation and faecal incontinence, can potentially have a negative influence on quality of life (QoL)12, 13. A distinction is often made between generic QoL and health‐related QoL, the latter focusing primarily on aspects of life that are influenced directly by an individual's health. In patients with HD, the relationship between functional complaints and QoL has been studied previously, but these studies were often performed with health‐related QoL questionnaires and only rarely were generic QoL questionnaires used14. Moreover, it remains unclear how functional outcomes continue to influence QoL after the transition into adulthood14.

The primary aim of this study was to investigate the long‐term functional outcomes in different age groups and to compare them with data from matched controls. Secondary aims were to identify factors associated with poor outcomes and to evaluate the influence of poor functional outcomes on QoL using generic QoL questionnaires.

Methods

This study had the approval code METc 2013/226 and was performed in compliance with the requirements of the local medical ethics review board. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

The medical records of all known patients diagnosed with HD in all six paediatric surgical centres in the Netherlands were reviewed. Inclusion criteria were pathologically proven HD and a minimum age of 8 years. The following variables were collected from the records: co‐morbidities, length of aganglionosis, surgical treatment, episodes of enterocolitis, surgical complications and additional surgical interventions. Enterocolitis was defined as the presence of symptoms such as abdominal distension, diarrhoea, bloody stools and/or fever with the intention to treat as such15. Surgical complications were defined as complications that occurred within 30 days and were the direct result of the initial surgical intervention (such as anastomotic leakage, wound infection and adhesions).

After the exclusion of patients who were ineligible to participate (deceased, living abroad, had a permanent stoma or an intellectual disability), the remaining patients were invited to participate in the study. In the case of children aged between 8 and 17 years, parents or caregivers were asked to participate together with the patients, or on their behalf. On agreeing to participate, patients received questionnaires on anorectal functioning and QoL. For children, these were the Paediatric Defaecation and Faecal Continence (P‐DeFeC) questionnaire16 and the Child Health Questionnaire Child Form 87 (CHQ‐CF87)17. Adults received the Defaecation and Faecal Continence (DeFeC) questionnaire16 and the WHO Quality of Life 100 (WHOQOL‐100) questionnaire18.

Assessment of functional outcomes

Functional outcomes were assessed using patients' answers to the P‐DeFeC and DeFeC questionnaires, which allowed the authors to score the Rome IV criteria, and assess the use of therapies for constipation and faecal incontinence.

Constipation was defined by the Rome IV criteria for functional constipation19. To meet these criteria, patients should have at least two of the following symptoms: straining, hard or lumpy stools, incomplete evacuation, anorectal obstruction, use of manual manoeuvres to facilitate defaecation, or fewer than three bowel movements a week. Additionally, loose stools should rarely be present without the use of laxatives. The individual symptoms incorporated in the Rome IV criteria were also assessed for functional constipation, which had to occur at least several times a month.

Faecal incontinence was defined by the Rome IV criteria for faecal incontinence as recurrent uncontrolled passage of faecal material, including soiling, at least several times a month20. Several subtypes of faecal incontinence were also assessed, such as soiling (loss of small amounts of faeces), urge incontinence (inability to reach the toilet in time), incontinence to solid stool (loss of large amounts of solid faeces without having felt urge) and incontinence to liquid stool (loss of watery stools or diarrhoea).

By means of the questionnaire, an evaluation was undertaken of the use of laxatives and bowel management at least several times a month as therapy for constipation or faecal incontinence.

Reference data for the P‐DeFeC and DeFeC questionnaires were available from studies that had been performed previously in the general Dutch population. This produced 1103 healthy children and adults who did not have a history of bowel surgery or somatic diseases that could influence their bowels21, 22.

Assessment of quality of life

The CHQ‐CF8717 was used to assess QoL in children aged 8–17 years. This is a generic QoL questionnaire with 87 items that are scored on a four‐ to six‐point Likert scale. Following completion, ten multi‐item domains and two single‐item questions were calculated and converted to a 0–100‐point continuum, where a higher score indicates better QoL. The following domains were assessed for this study: behaviour, mental health, self‐esteem and general health.

The WHOQOL‐10018 was used to assess QoL in adults. The WHOQOL‐100 consists of 100 items covering six domains and a general evaluative facet (overall QoL and general health). The items are scored on a five‐point Likert scale. Calculated domain scores range between 4 and 20 points; a higher domain score indicates better QoL. The following domains were analysed in the present study: overall QoL, physical health, psychological health and social relationships.

Reference data for the healthy Dutch population were available for both the CHQ‐CF8723 and WHOQOL‐100 questionnaires (courtesy of J. de Vries, University of Tilburg)24.

Statistical analysis

Proportions are reported as prevalence percentages with 95 per cent confidence intervals. Quantitative variables are expressed as mean(s.d.) or median (range). Statistical tests used were χ2, Mann–Whitney U and t tests. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to test the association between potential risk factors and the likelihood of faecal incontinence, with results reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95 per cent confidence intervals. The multivariable analysis was built using variables that tended towards significance (P < 0·100) in the univariable analyses. Two‐sided P < 0·050 was considered statistically significant. Data were analysed with SPSS® version 23.0 for Windows® (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

Based on the inclusion criteria, 830 patients were identified as eligible for the study, of whom 211 were subsequently excluded: patients who had died (43), who lived abroad (47), whose addresses were not available (10) or who were unable to complete one of the questionnaires because of a permanent stoma (25) or intellectual disability (such as Down syndrome, 86). The most common reasons for a permanent stoma were postoperative complications (7), persistent constipation (5) and severe intellectual disability (3). A total of 619 patients received an invitation to participate in the study (Fig. S1, supporting information).

Following invitation, 346 patients and their parents or caregivers (55·9 per cent) agreed to participate and completed the questionnaires (Table 1). There were 173 children aged 8–17 years and 173 adults with HD. Additional patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. A dropout analysis showed that the only significant difference between non‐responders and responders was in median age: 22 (range 8–50) versus 18 (8–45) years respectively (P = 0·004). The 346 patients who responded were randomly matched 1 : 1 with controls on the basis of sex and age. Because of the high prevalence of male patients, it was not possible to match 52 patients with appropriate controls. This did not result in significant differences in sex or age between the group of 346 patients with HD and the group of 294 controls.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and dropout analysis

| Non‐responders (n = 273) | Responders (n = 346) | P † | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 22 (8–50) | 18 (8–45) | 0·004‡ |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 224 : 49 | 274 : 72 | 0·373 |

| Co‐morbidities | 26 (9·5) | 33 (9·5) | 1·000 |

| Length of aganglionosis | 0·804 | ||

| Ultrashort | 5 (1·8) | 10 (2·9) | |

| Rectosigmoid | 222 (81·3) | 282 (81·5) | |

| Long segment | 23 (8·4) | 29 (8·4) | |

| Total colonic | 23 (8·4) | 25 (7·2) | |

| Preoperative enterocolitis | 30 (11·0) | 46 (13·3) | 0·395 |

| Primary surgical treatment | 0·443 | ||

| Surgical reconstruction | 265 (97·1) | 337 (97·4) | |

| Sphincterectomy | 3 (1·1) | 4 (1·2) | |

| Other | 2 (0·7) | 0 (0·0) | |

| None/conservative | 3 (1·1) | 5 (1·4) | |

| Surgical reconstruction | 0·166 | ||

| Duhamel | 149 (56·2) | 210 (62·3) | |

| Soave | 1 (0·4) | 1 (0·3) | |

| Rehbein | 80 (30·2) | 73 (21·7) | |

| Swenson | 0 (0) | 1 (0·3) | |

| Transanal endorectal pull‐through | 35 (13·2) | 52 (15·4) | |

| Postoperative complication | 26 of 270 (9·6) | 36 of 341 (10·6) | 0·706 |

| Postoperative enterocolitis | 24 of 270 (8·9) | 47 of 341 (13·8) | 0·061 |

| Redo pull‐through | 15 of 270 (5·6) | 23 of 341 (6·7) | 0·546 |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (range).

χ2 test, except

Mann–Whitney U test.

Functional outcomes in children

The prevalence of constipation was comparable between children with HD and their controls (22·0 versus 14·3 per cent respectively). However, the patients had symptoms such as straining, incomplete evacuation and anorectal obstruction significantly more often (Table 2). The patients also used laxatives (30·6 versus 4·1 per cent; P < 0·001) and bowel management (17·9 versus 0·7 per cent; P < 0·001) to treat constipation significantly more frequently than controls.

Table 2.

Functional outcomes in children and adults

| Children (8–17 years) | Adults (≥ 18 years) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n = 173) | Controls (n = 147) | P † | Patients (n = 173) | Controls (n = 147) | P † | P (patients: children versus adults)† | |

| Constipation | |||||||

| Prevalence (Rome IV) | 38 (22·0) | 21 (14·3) | 0·077 | 38 (22·0) | 28 (19·0) | 0·520 | 1·000 |

| Symptoms | |||||||

| Straining | 64 (37·0) | 32 (21·8) | 0·003 | 87 (50·3) | 53 (36·1) | 0·011 | 0·013 |

| Lumpy or hard stools | 5 (2·9) | 14 (9·5) | 0·012 | 11 (6·4) | 9 (6·1) | 0·931 | 0·125 |

| Incomplete evacuation | 68 (39·3) | 13 (8·8) | < 0·001 | 82 (47·4) | 40 (27·2) | < 0·001 | 0·129 |

| Anorectal obstruction | 39 (22·5) | 17 (11·6) | 0·010 | 44 (25·4) | 25 (17·0) | 0·068 | 0·529 |

| Manual manoeuvres | 0 (0) | 3 (2·0) | 0·059 | 10 (5·8) | 7 (4·8) | 0·686 | 0·001 |

| < 3 bowel movements per week | 12 (6·9) | 12 (8·2) | 0·678 | 18 (10·4) | 19 (12·9) | 0·482 | 0·252 |

| Laxative use | 53 (30·6) | 6 (4·1) | < 0·001 | 9 (5·2) | 6 (4·1) | 0·636 | < 0·001 |

| Bowel management for constipation | 31 (17·9) | 1 (0·7) | < 0·001 | 14 (8·1) | 1 (0·7) | 0·002 | 0·007 |

| Faecal incontinence | |||||||

| Prevalence (Rome IV) | 65 (37·6) | 9 (6·1) | < 0·001 | 29 (16·8) | 9 (6·1) | 0·003 | < 0·001 |

| Subtypes* | |||||||

| Soiling | 60 (34·7) | 6 (4·1) | < 0·001 | 29 (16·8) | 6 (4·1) | < 0·001 | < 0·001 |

| Urge incontinence | 7 (4·0) | 2 (1·4) | 0·148 | 2 (1·2) | 3 (2·0) | 0·525 | 0·091 |

| Incontinence to solid stool | 12 (6·9) | 3 (2·0) | 0·039 | 2 (1·2) | 3 (2·0) | 0·525 | 0·006 |

| Incontinence to liquid stool | 15 (8·7) | 2 (1·4) | 0·004 | 5 (2·9) | 5 (3·4) | 0·793 | 0·021 |

| Bowel management for faecal incontinence | 19 (11·0) | 1 (0·7) | < 0·001 | 3 (1·7) | 0 (0·0) | 0·109 | 0·017 |

Values in parentheses are percentages.

Respondents often had various types of faecal incontinence.

χ2 test.

The overall prevalence of faecal incontinence was significantly higher in children with HD than their controls (37·6 versus 6·1 per cent; P < 0·001). The most common subtype of faecal incontinence among the patients was soiling (34·7 per cent), followed by incontinence to liquid (8·7 per cent) and solid (6·9 per cent) stool, all of which were significantly more prevalent than in controls (Table 2). Bowel management to treat faecal incontinence was used in 11·0 per cent of patients, but only 0·7 per cent of controls (P < 0·001).

Functional outcomes in adults

The prevalence of constipation was comparable between adult patients and adult controls (22·0 versus 19·0 per cent; P = 0·520). The adults with HD had symptoms such as straining and incomplete evacuation significantly more often than their controls (Table 2). Using laxatives was not more common among patients compared with their control group, whereas they more often used bowel management to treat constipation (8·1 versus 0·7 per cent; P = 0·002).

The overall prevalence of faecal incontinence was higher in adult patients compared with their controls (16·8 versus 6·1 per cent; P = 0·003). This was mainly the result of a significantly higher prevalence of soiling (16·8 versus 4·1 per cent; P < 0·001), which was the only subtype of faecal incontinence that showed a significant difference (Table 2).

Comparison of functional outcomes in children and adult patients

The prevalence of constipation was the same in children and adults with HD (both 22·0 per cent). Nevertheless, adult patients reported straining and manual manoeuvres when defaecating more often than children (Table 2). For the treatment of constipation, children used laxatives (30·6 versus 5·2 per cent; P < 0·001) and bowel management (17·9 versus 8·1 per cent; P = 0·007) significantly more often than adult patients.

Among patients with HD, the overall prevalence of faecal incontinence was lower in adults than children (16·8 versus 37·6 per cent; P < 0·001). The subtypes of faecal incontinence, such as soiling, incontinence to solid stool and incontinence to liquid stool, were all significantly less prevalent in adults (Table 2). Only 1·7 per cent of the adult patients required bowel management for faecal incontinence, compared with 11·0 per cent of children (P = 0·017).

Factors associated with faecal incontinence

In univariable analyses, sex, length of aganglionosis and postoperative complication were not significantly associated with faecal incontinence, whereas age group and redo pull‐through procedures were (Table 3). The multivariable analysis showed that adult patients were significantly less likely to report faecal incontinence than children with HD (OR 0·35, 95 per cent c.i. 0·21 to 0·58). Patients who required a redo pull‐through were significantly more likely to have faecal incontinence than patients who had only undergone one procedure (OR 3·54, 1·46 to 8·62). There was no significant interaction between the variables used in the multivariable analysis.

Table 3.

Prevalence and likelihood of faecal incontinence

| Likelihood of faecal incontinence‡ | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||||

| Total no. of patients* | Prevalence of faecal incontinence (%) | P † | Odds ratio | P | Odds ratio | P | |

| Overall | 346 | 27·2 (22·5, 31·9) | |||||

| Sex | 0·175 | ||||||

| Men | 274 (79·2) | 28·8 (23·4, 34·2) | 1·00 (reference) | ||||

| Women | 72 (20·8) | 21 (11, 30) | 0·65 (0·35, 1·21) | 0·177 | |||

| Patient group | < 0·001 | ||||||

| Children (8–17 years) | 173 (50·0) | 37·6 (30·3, 44·9) | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| Adults (≥ 18 years) | 173 (50·0) | 16·8 (11·1, 22·4) | 0·33 (0·20, 0·55) | < 0·001 | 0·35 (0·21, 0·58) | < 0·001 | |

| Length of aganglionosis | 0·482 | ||||||

| Ultrashort | 10 (2·9) | 20 (–10, 50) | 0·70 (0·15, 3·38) | 0·660 | |||

| Rectosigmoid | 282 (81·5) | 26·2 (21·1, 31·4) | 1·00 (reference) | ||||

| Long segment | 29 (8·4) | 28 (10, 45) | 1·07 (0·45, 2·52) | 0·876 | |||

| Total colonic | 25 (7·2) | 40 (19, 61) | 1·87 (0·81, 4·35) | 0·144 | |||

| Postoperative complication | 0·777 | ||||||

| No | 305 (89·4) | 27·2 (22·2, 32·2) | 1·00 (reference) | ||||

| Yes | 36 (10·6) | 25 (10, 40) | 0·89 (0·40, 1·97) | 0·769 | |||

| Redo pull‐through | 0·001 | ||||||

| No | 323 (93·4) | 25·1 (20·3, 29·8) | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 23 (6·6) | 57 (35, 78) | 3·88 (1·64, 9·20) | 0·002 | 3·54 (1·46, 8·62) | 0·005 | |

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals unless indicated otherwise;

values in parentheses are percentages.

χ2 test.

Logistic regression analysis; variables with P < 0·100 in univariable analysis were subsequently included in the multivariable analysis.

Comparison of functional outcomes and quality of life

The QoL questionnaires were completed by 150 children and 160 adults with HD; 36 patients omitted the QoL questionnaire after completing the questionnaire on anorectal functioning.

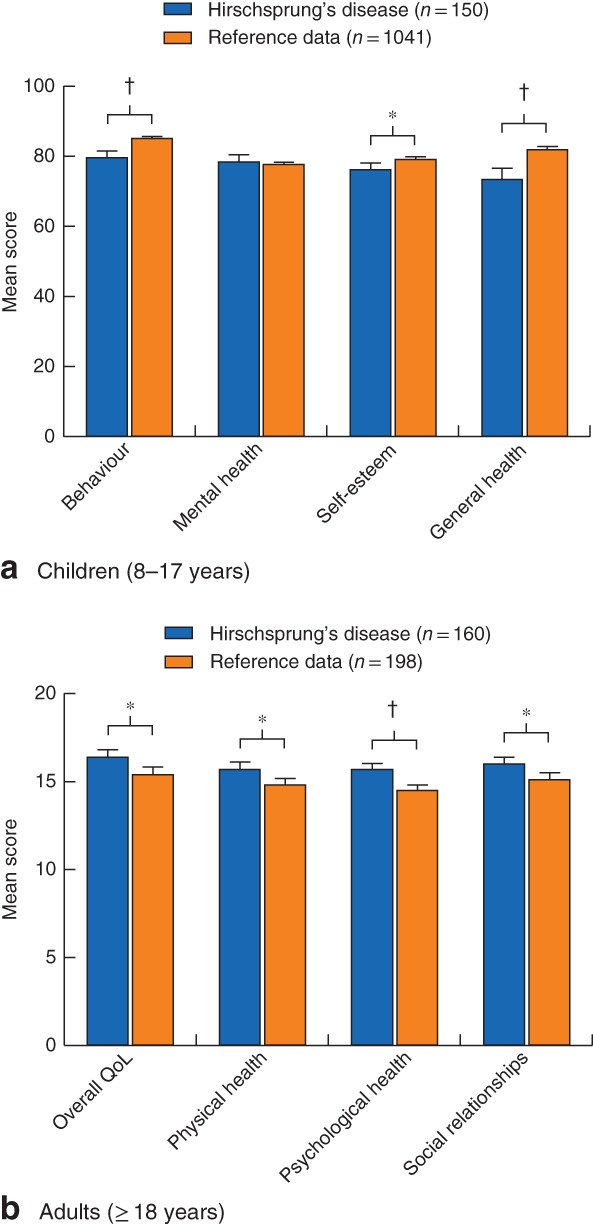

Comparing mean QoL domain scores of children with HD with reference data from the general population, the patients had significantly lower scores for behaviour (mean(s.d.) 80(13) versus 85(11); P < 0·001), self‐esteem (76(13) versus 79(13); P = 0·008) and general health (73(20) versus 82(14); P < 0·001) (Fig. 1 a). Among children with HD, the constipated group had significantly lower median scores on all four domains tested than the group without constipation (Table 4). Children with faecal incontinence alone had significantly lower median scores for the domains behaviour (83 (range 61–99) versus 77 (21–98); P = 0·010) and general health (81 (19–100) versus 74 (26–100; P = 0·017) than those without faecal incontinence.

Figure 1.

Quality‐of‐life scores of children and adults with Hirschsprung's disease compared with reference data from healthy controls. a Child Health Questionnaire Child Form (CHQ‐CF87) scores in children; b WHO Quality of Life (WHOQOL‐100) score in adults. Values are mean with 95 per cent confidence interval. QoL, quality of life. *P < 0·050, †P < 0·001 (t test)

Table 4.

Comparison of functional outcomes and quality of life in patients with Hirschsprung's disease

| Constipation (Rome IV criteria) | Faecal incontinence (Rome IV criteria) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | P * | No | Yes | P * | |

| CHQ‐CF87 score (n = 150) | ||||||

| Behaviour | 82 (21–99) | 76 (46–97) | 0·010 | 83 (61–99) | 77 (21–98) | 0·010 |

| Mental health | 81 (50–100) | 76 (42–97) | 0·021 | 81 (42–100) | 77 (50–100) | 0·056 |

| Self‐esteem | 77 (30–100) | 73 (41–100) | 0·013 | 75 (41–100) | 77 (30–100) | 0·877 |

| General health | 80 (21–100) | 69 (19–99) | 0·004 | 81 (19–100) | 74 (26–100) | 0·017 |

| WHOQOL‐100 score (n = 160) | ||||||

| Overall QoL | 16 (10–20) | 16 (7–20) | 0·055 | 16 (9–20) | 16 (7–20) | 0·319 |

| Physical health | 16 (8–20) | 15 (7–20) | 0·077 | 16 (10–20) | 15 (7–20) | 0·018 |

| Psychological health | 16 (10–20) | 15 (10–19) | 0·025 | 16 (10–20) | 15 (10–20) | 0·204 |

| Social relationships | 16 (9–20) | 15 (9–19) | 0·079 | 16 (9–20) | 16 (9–20) | 0·141 |

Values are median (range). CHQ‐CF87, Child Health Questionnaire Child Form; WHOQOL‐100, WHO Quality of Life questionnaire. QoL, quality of life.

Mann–Whitney U test.

In an analysis of mean QoL domain scores in adult patients compared with their reference data set, adult patients had significantly higher scores for overall QoL (mean(s.d.) 16(3) versus 15(3); P = 0·001), physical health (16(3) versus 15(3); P = 0·002), psychological health (16(2) versus 15(2); P < 0·001) and social relationships (16(3) versus 15(3); P = 0·002) (Fig. 1 b). The only significant difference between constipated and non‐constipated adult patients was in the domain psychological health (median 16 (range 10–20) versus 15 (10–19); P = 0·025). The only significant difference between faecally continent and incontinent adult patients was in the domain of physical health (16 (10–20) versus 15 (7–20); P = 0·018).

Discussion

This nationwide study showed that functional outcomes were better in adults than children with HD, but that defaecation disorders persisted in a substantial group of adults. Patients who required a redo pull‐through procedure were more likely to have faecal incontinence. In the present cohort, defaecation disorders, especially constipation, negatively influenced QoL domains, with a more prominent effect in children than adults.

Interestingly, the prevalence of constipation in both children and adults with HD was comparable to that in their respective control groups. These findings warrant reflection. The true prevalence of constipation in patients with HD may be masked by the more frequent use of laxatives and bowel management than in controls. If true, this could also mean that the prevalence of constipation may decrease as the patients grow older, because the use of laxatives and rectal irrigation was significantly lower in adults than in children. As indicated by the increased frequency of symptoms found in this study, it may be that both children and adults with HD experienced more severe forms of constipation than controls.

In contrast to constipation, the prevalence of faecal incontinence was significantly higher in patients with HD than controls. It is important to note, however, that children more often had severe subtypes of faecal incontinence, such as incontinence to solid and liquid stool, whereas adult patients often reported soiling only. This means that both the prevalence and severity of faecal incontinence may decrease with age, although adults with HD did retain a significantly higher prevalence of soiling than controls. In contrast to the present results, a recent study6 concluded that faecal incontinence would eventually diminish to a prevalence not significantly different from that of healthy controls, even though soiling persisted in well over 40 per cent in their adult subgroup. It therefore seems that faecal continence may improve with age, but that problems persist well into adulthood. There are various reasons for this. Faecal incontinence in these patients may result from damage to the anal sphincter during reconstructive surgery25, depending on the type and quality of the initial surgery. With regard to the type of surgery, there is currently little evidence that substantiates the decision to opt for one technique over another26, 27, 28. The authors believe that further analyses, such as anorectal manometry or anal sphincter electromyography, should be performed to assess the differences between the techniques, especially between the transanal endorectal pull‐through and Duhamel operations, which currently are the two most commonly performed procedures. Such investigations might also give an objective prognosis regarding the functional outcomes in individual patients. In addition, impaired continence may result from more severe constipation in patients with HD21, which could be the result of a persistently absent rectoanal inhibitory reflex, stenosis of the anal sphincter following surgery or lack of pelvic floor coordination29. The absence of a rectal reservoir following surgery and subsequent increased defaecation frequency may further contribute to impaired faecal continence. In the present study, patients who required a redo pull‐through procedure were significantly more likely have faecal incontinence. A recent study30 indeed showed that short‐term outcomes after redo pull‐through procedures were complicated by a relatively high rate of soiling and faecal incontinence30. Important to note, however, is the finding that other functional symptoms, such as constipation and abdominal pain, improved following the redo procedure30. It remains unclear to what extent the redo procedure itself contributed to the impaired faecal continence, because it may already have been worse in these patients before the redo procedure. The authors merely conclude that a redo procedure may ultimately be necessary in some patients, but that one should be cautious about promising favourable functional outcomes, because the prevalence of faecal incontinence remains high after redo procedures. Given the heterogeneity of surgical techniques used, more comprehensive studies are required to analyse accurately the possible association between long‐term outcomes and different types of pull‐through procedure.

In terms of QoL, the present results showed that children with HD had significantly lower QoL domain scores compared with the reference data. These differences may be explained partially by poor functional outcomes, because constipation and faecal incontinence negatively influenced several QoL domains. In contrast to children, adult patients scored better on all four domains tested compared with their respective reference data sets. This could be the result of improved functional outcomes in adult patients compared with children. A more plausible explanation might be that adults develop better coping strategies to deal with their complaints31, 32. By way of illustration, adults may have more options to adapt their lives to accommodate for any defaecation disorders, whereas children are often bound by fixed schedules, such as school and after‐school activities.

The strength of this study was the large number of participants, from all six paediatric surgery centres in the Netherlands, and the relatively high response rate of 55·9 per cent. One limitation was the significant age difference between included patients and non‐respondents, even though the remaining variables all proved to be statistically non‐significant. The difference in age between respondents and non‐respondents was most likely the result of the high response rate among children with HD, supported by their parents, who were found to be more motivated to participate than adult patients. An attempt was made to overcome this possible inclusion bias by performing separate analyses in adults and children, and making age‐ and sex‐matched comparisons. Another limitation may be the cross‐sectional design of this study. A longitudinal design would have been preferable to analyse the influence of ageing on functional outcomes.

The results of this nationwide study showed that functional outcomes were better in adults than children with HD, although symptoms of constipation and soiling persisted in a substantial group of adults. One factor associated with poor functional outcomes was a redo pull‐through procedure, following which patients were significantly more likely have faecal incontinence. Poor functional outcomes negatively influenced QoL in children, whereas this influence diminished partially upon reaching adulthood, indicating better coping strategies in adults. Persistent symptoms of constipation and soiling indicate the need for counselling and transitional care in a specific group of patients.

Supporting information

Fig. S1 Study flow diagram

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the employees of RoQua, particularly I. A. M. ten Vaarwerk and E. Visser, for their help in processing the data from the digital questionnaire and preparing the database; T. van Wulfften Palthe for correcting the English manuscript; and J. de Vries for supplying the appropriate reference data for the WHOQOL‐100 questionnaire.

Presented to the 19th European Paediatric Surgeons' Association Annual Congress, Paris, France, June 2018

References

- 1. Menezes M, Corbally M, Puri P. Long‐term results of bowel function after treatment for Hirschsprung's disease: a 29‐year review. Pediatr Surg Int 2006; 22: 987–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ieiri S, Nakatsuji T, Akiyoshi J, Higashi M, Hashizume M, Suita S et al Long‐term outcomes and the quality of life of Hirschsprung disease in adolescents who have reached 18 years or older – a 47‐year single‐institute experience. J Pediatr Surg 2010; 45: 2398–2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jarvi K, Laitakari EM, Koivusalo A, Rintala RJ, Pakarinen MP. Bowel function and gastrointestinal quality of life among adults operated for Hirschsprung disease during childhood: a population‐based study. Ann Surg 2010; 252: 977–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aworanti OM, McDowell DT, Martin IM, Quinn F. Does functional outcome improve with time postsurgery for Hirschsprung disease? Eur J Pediatr Surg 2016; 26: 192–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Niramis R, Watanatittan S, Anuntkosol M, Buranakijcharoen V, Rattanasuwan T, Tongsin A et al Quality of life of patients with Hirschsprung's disease at 5–20 years post pull‐through operations. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2008; 18: 38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Neuvonen MI, Kyrklund K, Rintala RJ, Pakarinen MP. Bowel function and quality of life after transanal endorectal pull‐through for Hirschsprung disease: controlled outcomes up to adulthood. Ann Surg 2017; 265: 622–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Catto‐Smith AG, Trajanovska M, Taylor RG. Long‐term continence after surgery for Hirschsprung's disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 22: 2273–2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bjørnland K, Pakarinen MP, Stenstrøm P, Stensrud KJ, Neuvonen M, Granström AL et al; Nordic Pediatric Surgery Study Consortium. A Nordic multicenter survey of long‐term bowel function after transanal endorectal pull‐through in 200 patients with rectosigmoid Hirschsprung disease. J Pediatr Surg 2017; 52: 1458–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim AC, Langer JC, Pastor AC, Zhang L, Sloots CE, Hamilton NA et al Endorectal pull‐through for Hirschsprung's disease – a multicenter, long‐term comparison of results: transanal vs transabdominal approach. J Pediatr Surg 2010; 45: 1213–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rintala RJ, Pakarinen MP. Long‐term outcomes of Hirschsprung's disease. Semin Pediatr Surg 2012; 21: 336–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mills JL, Konkin DE, Milner R, Penner JG, Langer M, Webber EM. Long‐term bowel function and quality of life in children with Hirschsprung's disease. J Pediatr Surg 2008; 43: 899–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bartlett L, Nowak M, Ho YH. Impact of fecal incontinence on quality of life. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15: 3276–3282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Belsey J, Greenfield S, Candy D, Geraint M. Systematic review: impact of constipation on quality of life in adults and children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010; 31: 938–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hartman EE, Oort FJ, Aronson DC, Sprangers MA. Quality of life and disease‐specific functioning of patients with anorectal malformations or Hirschsprung's disease: a review. Arch Dis Child 2011; 96: 398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gosain A, Brinkman AS. Hirschsprung's associated enterocolitis. Curr Opin Pediatr 2015; 27: 364–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Meinds RJ, Timmerman MEW, van Meegdenburg MM, Trzpis M, Broens PMA. Reproducibility, feasibility and validity of the Groningen Defecation and Fecal Continence Questionnaires. Scand J Gastroenterol 2018; 53: 790–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Landgraf JM, Abetz L, Ware J. The CHQ User Manual. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center: Boston, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18. De Vries J, Heck V. De Nederlandse versie van de WHOQOL‐100 (The Dutch version of the WHOQOL‐100). Tilburg University: Tilburg, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M et al Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: 1393–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rao SS, Bharucha AE, Chiarioni G, Felt‐Bersma R, Knowles C, Malcolm A et al Functional anorectal disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: 1430–1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Meinds RJ, van Meegdenburg MM, Trzpis M, Broens PM. On the prevalence of constipation and fecal incontinence, and their co‐occurrence, in the Netherlands. Int J Colorectal Dis 2017; 32: 475–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Timmerman MEW, Trzpis M, Broens PMA. The problem of defecation disorders in children is underestimated and easily goes unrecognized: a cross‐sectional study. Eur J Pediatr 2018; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hosli E, Detmar S, Raat H, Bruil J, Vogels T, Verrips E. Self‐report form of the Child Health Questionnaire in a Dutch adolescent population. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2007; 7: 393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties . Soc Sci Med 1998; 46: 1569–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Heikkinen M, Rintala R, Luukkonen P. Long‐term anal sphincter performance after surgery for Hirschsprung's disease. J Pediatr Surg 1997; 32: 1443–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gosemann JH, Friedmacher F, Ure B, Lacher M. Open versus transanal pull‐through for Hirschsprung disease: a systematic review of long‐term outcome. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2013; 23: 94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seo S, Miyake H, Hock A, Koike Y, Yong C, Lee C et al Duhamel and transanal endorectal pull‐throughs for Hirschsprung' disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2018; 28: 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tannuri AC, Ferreira MA, Mathias AL, Tannuri U. Long‐term results of the Duhamel technique are superior to those of the transanal pullthrough: a study of fecal continence and quality of life. J Pediatr Surg 2017; 52: 449–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Meinds RJ, Eggink MC, Heineman E, Broens PM. Dyssynergic defecation may play an important role in postoperative Hirschsprung's disease patients with severe persistent constipation: analysis of a case series. J Pediatr Surg 2014; 49: 1488–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dingemans A, van der Steeg H, Rassouli‐Kirchmeier R, Linssen MW, van Rooij I, de Blaauw I. Redo pull‐through surgery in Hirschsprung disease: short‐term clinical outcome. J Pediatr Surg 2017; 52: 1446–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Athanasakos E, Starling J, Ross F, Nunn K, Cass D. An example of psychological adjustment in chronic illness: Hirschsprung's disease. Pediatr Surg Int 2006; 22: 319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stam H, Hartman EE, Deurloo JA, Groothoff J, Grootenhuis MA. Young adult patients with a history of pediatric disease: impact on course of life and transition into adulthood. J Adolesc Health 2006; 39: 4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Study flow diagram