Abstract

Survival of human peripheral nervous system neurons and associated distal axons is highly dependent on energy. Diabetes invokes a maladaptation in glucose and lipid energy metabolism in adult sensory neurons, axons and Schwann cells. Mitochondrial (Mt) dysfunction has been implicated as an etiological factor in failure of energy homeostasis that results in a low intrinsic aerobic capacity within the neuron. Over time, this energy failure can lead to neuronal and axonal degeneration and results in increased oxidative injury in the neuron and axon. One of the key pathways that is impaired in diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) is the energy sensing pathway comprising the nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1)/peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator α (PGC-1α)/Mt transcription factor A (TFAM or mtTFA) signaling pathway. Knockout of PGC-1α exacerbates DPN, whereas over-expression of human TFAM is protective. LY379268, a selective metabolomic glutamate receptor 2/3 (mGluR2/3) receptor agonist, also upregulates the SIRT1/PGC-1α/TFAM signaling pathway and prevents DPN through glutamate recycling in Schwann/satellite glial (SG) cells and by improving dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neuronal Mt function. Furthermore, administration of nicotinamide riboside (NR), a precursor of NAD+, prevents and reverses DPN, in part by increasing NAD+ levels and SIRT1 activity. In summary, we review the role of NAD+, mitochondria and the SIRT1–PGC-1α–TFAM pathway both from the perspective of pathogenesis and therapy in DPN.

1. Introduction

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN), a common neurological complication of diabetes, exhibits a distal dying-back process of nerve fiber loss where collateral sprouting and regeneration are impaired. It is estimated that there are in excess of 400 million diabetics in the world (Cho et al., 2018). The largest populations of diabetics are in the Western Pacific and South-East Asia. Most of the countries with the highest prevalence of diabetes (12% or higher) are in the Western Pacific or Middle East/North Africa. The prevalence of distal symmetric polyneuropathy, the most common presentation of diabetic neuropathy, can be 50% or higher and is associated with pain and sensory loss. Currently, there is no therapy that permanently reverses neuropathy; only palliative treatment is available. The prevalence of diabetic neuropathy are predicted to rise by fivefold over the next 10 years due to the epidemic in obesity and an associated increase in incidence and earlier onset of type 2 diabetes (http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/home/index. html). Distal symmetric polyneuropathy in type 1 and 2 diabetes is associated with structural changes in the peripheral nerves including microangiopathy, a dying-back of distal axons that affects large myelinated and small axons characterized by a reduced intraepidermal nerve fiber density (IENFD), and sometimes with segmental demyelination.

The dying-back of nerves and formation of axonal swellings are critical pathological features in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes in humans and animals. To mitigate this neuropathic degeneration, strict glycemic control ameliorates but does not reverse neuropathy in type 1 patients (DCCT, 1993; EDIC, 2003). In contrast, glycemic control is relatively ineffective in preventing diabetic neuropathy in type 2 diabetes (Ang, Jaiswal, Martin, & Pop-Busui, 2014). In addition to hyperglycemia, dysdipidemia, due to increased lipid levels in blood, has been suggested as a major contributor to DPN in T2D. Defective Mt fatty acid oxidation in Schwann cells leading to accumulation of acylcarnitine in neurons and subsequent neuronal mitochondrial (Mt) dysfunction is suggested as a potential promoter of neuropathy (Viader et al., 2011). Mt oxidative damage in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons, axons, and Schwann cells has been proposed as a unifying mechanism for diabetic neuropathy (Chandrasekaran et al., 2015, 2017; Choi, Chandrasekaran, Inoue, Muragundla, & Russell, 2014; Chowdhury, Smith, & Fernyhough, 2013; Fernyhough, 2015; Russell et al., 2002; Sifuentes-Franco, Pacheco-Mois es, Rodríguez-Carrizalez, & Miranda-Díaz, 2017). Mt impairment is evidenced by depolarization of the inner Mt membrane potential in DRG neurons from diabetic animals, reduced respiratory chain activity in DRG neurons from diabetic rodents, and decreased Mt DNA (mtDNA) levels in DRG from mice with chronic diabetic neuropathy (Chandrasekaran et al., 2015, 2017; Chowdhury, Dobrowsky, & Fernyhough, 2011; Russell et al., 2002; Russell, Sullivan, Windebank, Herrmann, & Feldman, 1999). Impaired Mt may be rescued by the activation of Mt biogenesis or regeneration of new Mt. Thus, activation of Mt biogenesis may be protective under conditions where significant Mt degeneration is present.

2. Mitochondrial hypothesis of diabetic peripheral neuropathy

Mt oxidative damage in DRG neurons, axons, and Schwann cells has been proposed as a unifying mechanism for diabetic neuropathy (Chowdhury et al., 2011, 2013; Cowell & Russell, 2003; Fernyhough, 2015; Leinninger, Edwards, Lipshaw, & Feldman, 2006; Russell et al., 2002; Russell & Zilliox, 2014; Sifuentes-Franco et al., 2017; Vincent, Brownlee, & Russell, 2002; Vincent, Olzmann, Brownlee, Sivitz, & Russell, 2004). In normal DRG neurons and axons, the intermediary metabolism of carbohydrates and fatty acids that occur in Mt strips electrons from substrates leading to accumulation on the soluble electron carrier NADH and on protein-bound FADH2. The electrons from NADH and FADH2 are then passed down the Mt respiratory chain to drive ATP synthesis by oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). The redox energy generated by the electron transfer from NADH and FADH2 is conserved by pumping protons across the inner Mt membrane to build up a proton electrochemical potential gradient. This gradient, composed of a substantial membrane potential and a smaller pH gradient, is used by the ATP synthase to generate ATP, which is then mostly exported to the cytoplasm to carry out work.

Much of the long-term pathology of diabetes occurs because of persistent hyperglycemia. In cultured prenatal rat neurons with excess glucose, there is a 50% increase in mean Mt size and a rapid peak rise in reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Russell et al., 2002). This is coupled with loss of regulation of the Mt membrane potential (initial Mt membrane hyperpolarization followed by depolarization). Stabilizing the Mt membrane potential and blocking the adenosine nucleotide translocase reduces generation of ROS and DRG neuronal injury. Further evidence that hyperglycemia causes destabilization of the inner Mt membrane potential is provided by evidence showing that uncoupling proteins can prevent hyperpolarization of the inner membrane potential and reduce generation of ROS (Vincent et al., 2004). It is unknown if similar changes occur in vivo in diabetic neuropathy.

Small quantities of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are produced as by-products are detoxified in the nerve by cellular antioxidants such as glutathione, catalase, and superoxide dismutase (Vincent, Kato, McLean, Soules, & Feldman, 2009). In the peripheral nervous system, Schwann cells have a high antioxidant capacity, that exceeds that in peripheral sensory neurons (Vincent et al., 2009) and easily detoxify the accumulating ROS under normal metabolic conditions (Anjaneyulu, Berent-Spillson, & Russell, 2008; Berent-Spillson & Russell, 2007; Chandrasekaran et al., 2017; Cowell & Russell, 2004). While hyperglycemia does affect cultured adult Schwann cells, the concentration of glucose required to achieve significant cellular and Mt injury is very high (150mM) (Delaney, Russell, Cheng, & Feldman, 2001). Furthermore, in Schwann cells, the basal activity of antioxidant enzymes, for example, SOD and catalase, was similar to the maximum stimulated activities in the DRG neurons (Vincent et al., 2009). In contrast, addition of prooxidants to cultured Schwann cells further increased these enzyme antioxidant activities in Schwann cells. In contrast, long-term diabetes will damage Mt function. The increase in ROS can potentially damage Mt electron carriers and increase reverse electron flow from Complex I and III of the respiratory chain. In support, long-term diabetes is shown to cause depolarization of the inner Mt membrane potential, reduced respiratory chain activity, and decreased Mt DNA (mtDNA) levels in DRG neurons (Chandrasekaran et al., 2015; Chowdhury et al., 2011; Russell et al., 2002, 1999).

A further problem created by impaired Mt function is that of energy homeostasis. Neurons have a large surface area and in order to maintain their membrane potential, they are high-energy demanding (Sasaki, 2018). Survival of distal axons, which in humans may be a considerable distance from the soma, is dependent on axonal transport mechanisms that also require energy. The net effect of Mt dysfunction is that it results in a low intrinsic aerobic capacity within the neuron and over time this can lead to neuronal and axonal degeneration (Choi, Chandrasekaran, Demarest, et al., 2014; Zilliox, Chadrasekaran, Kwan, & Russell, 2016). Thus, Mt regeneration may be protective under conditions where significant Mt degeneration is present.

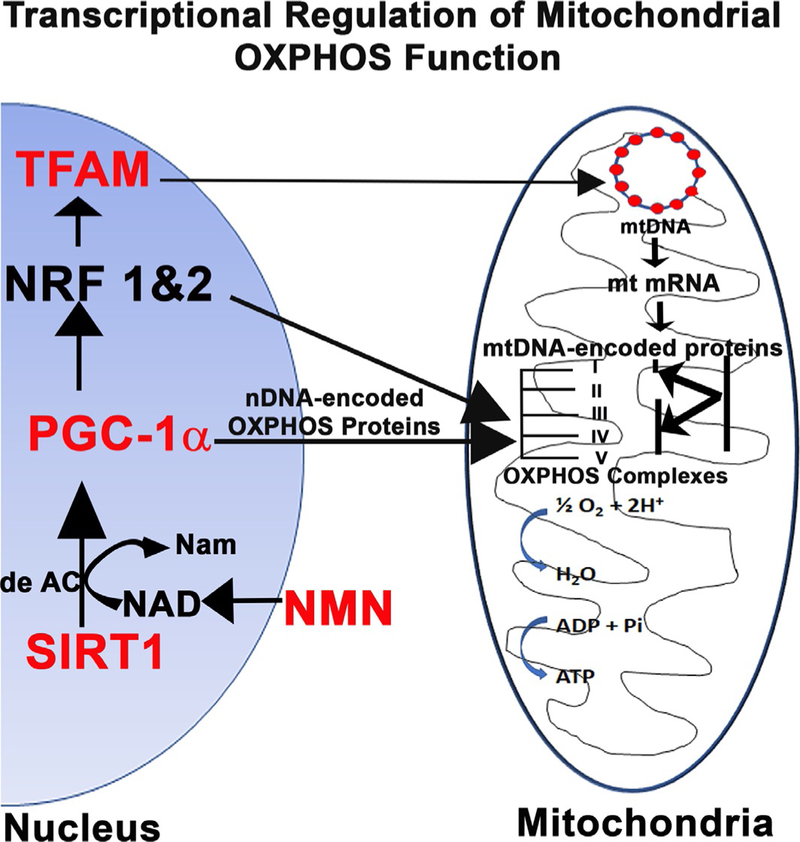

3. Control of mitochondrial biogenesis: The SIRT1–PGC-1α–TFAM axis

Mt biogenesis requires the participation of two genetic systems, nuclear DNA (nDNA) encoding most proteins that are transported to Mt and Mt DNA (mtDNA) which encodes subunit proteins that are part of Mt oxidative phosphorylation complexes (OXPHOS) I, III, IV and V (Garesse & Vallejo, 2001; Goffart & Wiesner, 2003; Jeong-Yu & Clayton, 1996; Jornayvaz & Shulman, 2010; Kelly & Scarpulla, 2004; Locker & Rabinowitz, 1979). Among the nDNA-encoded proteins, proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator α (PGC-1α) is a nuclear transcriptional coactivator and a master regulator of Mt biogenesis (Scarpulla, 2011). PGC-1α interacts with the nuclear receptor PPAR-γ and regulates the activities of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and nuclear respiratory factors (NRFs). The NRFs, in turn, promote the expression of the Mt transcription factor Mt transcription factor A (TFAM or mtTFA). TFAM a nDNA-encoded protein, binds to light- (LSP) and heavy-strand promoters (HSP) of mtDNA, from which transcripts are produced and then processed to yield the individual mRNAs encoding 13 subunits of the oxidative phosphorylation system, ribosomal, and transfer RNAs (Attardi, 1985; Bestwick & Shadel, 2013; Clayton, 2000). TFAM also promotes replication of mtDNA (Campbell, Kolesar, & Kaufman, 2012; Kang, Chu, & Kaufman, 2018; Kang, Kim, & Hamasaki, 2007). Post-translational modifications also regulate the activity of PGC-1α. For example, the nutrient sensing enzyme Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), a NAD+-dependent deacetylase, deacetylates multiple lysine residues in PGC-1α, activates it and thereby promotes Mt fatty acid metabolism in response to low glucose. Similarly, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is an enzyme sensor that is activated upon energy depletion in muscle (Jager, Handschin, St-Pierre, & Spiegelman, 2007). During energy deprivation, AMPK activation restores energy balance by increasing levels of ATP and reducing processes that consume ATP. AMPK is also known to circulate in the blood once released from muscle (Kobilo et al., 2014) and this could explain why exercise, which improves muscle function, can also have remote effects on somatic and autonomic nerve fibers. AMPK phosphorylates PGC-1α on specific serine and threonine residues (Jager et al., 2007) but deacetylation may also be necessary to activate PGC-1α (Canto et al., 2009). This results in increased Mt gene expression supporting the idea that AMPK can mediate at least some of its effects through PGC-1α (Canto et al., 2009). It is also apparent that the SIRT1 and AMPK pathways can work together to promote Mt function (Thirupathi & de Souza, 2017; Wu et al., 1999). Thus, SIRT1/AMPK-PGC-1α-TFAM axis is an important pathway to explore their potential against DPN in animal models.

4. PGC1-α in neuropathy: Effect on diabetes and lipid metabolism

PGC-1α is a transcriptional co-activator and a master regulator for Mt biogenesis in many tissues including the nervous system (Besseiche, Riveline, Gautier, Breant, & Blondeau, 2015; Lehman et al., 2008; Lin, Handschin, & Spiegelman, 2005). PGC-1α has been shown to be implicated in development of diabetes in humans (Andrulionyte, Kuulasmaa, Chiasson, & Laakso, 2007; Andrulionyte, Zacharova, Chiasson, & Laakso, 2004; Patti et al., 2003). PGC-1α has been mapped to chromosome 4P15.1, a region associated with basal insulin levels in Pima Indians that are at high risk of developing diabetes and diabetes-related complications (Baier et al., 2002; Muller, Bogardus, Beamer, Shuldiner, & Baier, 2003; Muller, Bogardus, Pedersen, & Baier, 2003). Furthermore, common polymorphisms of PGC-1α are associated with conversion from impaired glucose tolerance to diabetes (Andrulionyte et al., 2007; Vimaleswaran et al., 2005). Thus, it is likely that PGC-1α and its downstream signaling intermediates are important in normal Mt regulation in diabetic subjects (Mootha et al., 2003).

PGC-1α is a promising target for therapy against neurological disease. For example, the pan-PPAR agonist, bezafibrate, upregulates PGC-1α and exerts beneficial effects in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington’s disease (Johri et al., 2012). PGC-1α activates transcriptional factors such as nuclear respiratory factors 1 and 2 (NRF1 and NRF2) and TFAM, which in turn induce Mt respiratory chain proteins and lead to replication of the Mt genome (Kelly & Scarpulla, 2004; Puigserver & Spiegelman, 2003; Wu et al., 1999). Presence of PGC-1α has been clearly demonstrated in neurons (Choi, Chandrasekaran, Inoue, et al., 2014; Choi, Ravipati, et al., 2014; Cowell, Blake, Inoue, & Russell, 2007; Cowell, Blake, & Russell, 2007; Cowell, Talati, Blake, Meador-Woodruff, & Russell, 2009; Fernyhough, 2015) and knockout of PGC-1α in mice is associated with CNS neurodegeneration that includes the formation of large vacuoles in the neuropil and defects in energy metabolism (Leone et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2004). In diabetic wild type and PGC-1α knockout mice, there is no difference in plasma glucose, hemoglobin A1C, or insulin levels between wild type diabetic and PGC-1α knockout diabetic mice, indicating that exacerbation of peripheral nerve injury is independent of glycemic control (Choi, Chandrasekaran, Inoue, et al., 2014). However, significant increases in total cholesterol and triglyceride levels were observed in both non-diabetic PGC- 1α knockout mice relative to non-diabetic wild type mice and in diabetic PGC-1α knockout and diabetic wild type mice. These findings are consistent with recent observations that increased lipid levels are associated with neuropathy (Cooper et al., 2018; Hinder et al., 2017; Lewis et al., 2017; Rumora et al., 2018; Yorek et al., 2017). Importantly, a Mt specific 35kDa PGC-1α isoform localizes to the Mt inner membrane and matrix in neurons. This isoform interacts with the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) and its import in the Mt depends on VDAC. Valinomycin treatment which depolarizes the Mt potential, abolished Mt localization of the 35kDa PGC-1α. Furthermore, overexpression of PGC-1α decreases lipid-droplet accumulation and increases Mt fatty acid oxidation in diabetes (Choi, Ravipati, et al., 2014). In part, PGC-1α regulates lipid metabolism in neurons through two key enzymes in the Mt beta-oxidation machinery, acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase and Mt trifunctional enzyme subunit alpha (Choi, Ravipati, et al., 2014). Furthermore, decreased activation of PGC-1α is strongly correlated with impaired fatty acid oxidation (Heilbronn, Gregersen, Shirkhedkar, Hu, & Campbell, 2007) and adipose-specific ablation of PGC-1α results in Mt dysfunction (Kleiner et al., 2012). Thus, PGC-1α has a critical role in lipid metabolism and this may play an important role in the development of diabetic neuropathy.

5. Neuropathy is more severe in diabetic PGC-1α knockout mice

Comparison of nerve conduction studies in wild type diabetic and non-diabetic mice, and PGC-1α knockout diabetic and non-diabetic mice after 4 and 8 weeks of diabetes showed slowing of tail and sciatic nerve conduction values that were worse in PGC-1α knockout diabetic mice compared to PGC-1α knockout non-diabetic mice and wild type diabetic mice (Choi, Chandrasekaran, Inoue, et al., 2014). All were abnormal when compared to wild type non-diabetic mice. In general, nerve conduction parameters were reduced in diabetic PGC-1α knockout mice when compared to PGC-1α wild type diabetic animals, which is consistent with the concept that PGC-1α knockout worsens neuropathy. Sensory testing with von-Frey filaments showed mechanical allodynia was greater in PGC-1α knockout diabetic animals compared to PGC-1α wild type diabetic mice, consistent with more severe neuropathy in PGC-1α knockout diabetic compared to PGC-1α wild type diabetic mice.

Measurement of intraepidermal nerve fiber (IENF) innervation in the hind paw was tested as previously described (Chandrasekaran et al., 2015; Choi, Chandrasekaran, Inoue, et al., 2014). Epidermal fibers are small distal fibers that are very susceptible to mild diabetes (Russell & Zilliox, 2014; Zilliox et al., 2011). The IENF density was so severely affected in this model of type 1 diabetes mellitus that it was difficult to detect differences between diabetic PGC-1α wild type and diabetic PGC-1α knockout mice. However, non-diabetic PGC-1α knockout mice showed a significant decrease in IENF density along their length compared with non-diabetic PGC-1α wild type mice. In contrast, to the IENF, the dermal fibers were significantly decreased in diabetic PGC-1α knockout mice compared to diabetic PGC-1α wild type and non-diabetic PGC-1α knockout mice, supporting the concept that knockout of PGC-1α increases susceptibility to neuropathy in a model of type 1 diabetes. Thus, loss of PGC-1α in diabetes increases the susceptibility to develop both large and small fiber neuropathy.

6. Effect of PGC-1α knockout on mitochondrial function in diabetic neuropathy

Loss of PGC-1α impairs Mt function and the Mt anti-oxidant response (Choi, Chandrasekaran, Inoue, et al., 2014). In PGC-1α knockout DRG neurons, the Mt were morphologically abnormal, as viewed by transmission electron microscopy. DRG from the PGC-1α knockout mice had autophagic vacuoles containing electron dense material and empty vacuolar structures with double trilaminar membranes that likely represented terminal Mt degeneration. In isolated Mt from PGC-1α knockout DRG neurons there was reduced state 3 and 4 respiration consistent with reduced respiratory function. Furthermore, gene expression of glutathione peroxidase (GPX) and manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) were reduced while protein levels of transcription factors that regulate Mt transcription and are important for normal Mt homeostasis (e.g., TFAM and NRF1) were significantly decreased in DRG neurons of both PGC-1α (−/−) non-diabetic and diabetic mice. Moreover, levels of oxidized proteins consistent with increased oxidative stress were significantly increased and overexpression of PGC-1α, using an adenoviral construct, prevented the generation of ROS in adult mouse DRG cultures.

Mice that overexpress PGC-1α specifically in DRG neurons are not available to determine if overexpression of PGC-1α would prevent neuropathy. On the other hand, generalized overexpression of PGC-1α cannot be viably tested because these mice develop a fatal cardiomyopathy (Lehman et al., 2008). Further support for the role of PGC-1α in Mt regulation is provided by data from humans with insulin resistance and diabetes that shows an inverse correlation between muscle PGC-1α levels and Mt activity (Mootha et al., 2003; Patti et al., 2003) and different PGC-1α knockout mice have degenerating Mt in the CNS (Jiang et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2004). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that PGC-1α knockout results in Mt degeneration and failure of Mt respiration. Genetic ablation of PGC-1α exacerbates DPN and is associated with Mt degeneration and increased oxidative stress. In contrast, overexpression of PGC-1α in neurons prevents high glucose-induced oxidative injury (Choi, Chandrasekaran, Inoue, et al., 2014).

Importantly, the transcriptional upstream activators of TFAM, PGC-1α and SIRT1, are present inside Mt and are in close proximity to mtDNA (Aquilano, Baldelli, Pagliei, & Ciriolo, 2013; Aquilano et al., 2010). In these studies, PGC-1α and SIRT1 were shown to interact with TFAM, as assessed by confocal microscopy analysis and by Blue Native-PAGE. Furthermore, PGC-1α is present on the same D-loop region recognized by TFAM. PGC-1α and SIRT1 are associated with the TFAM consensus sequence (MT-TFH).

7. TFAM and mtDNA: Transcription, replication, and protection

TFAM is essential for maintenance of mtDNA and for cell survival. Homozygous knockout of TFAM is embryonic lethal (Larsson et al., 1998). In contrast, mice with tissue-specific TFAM knockout survive and have been used to study the role of TFAM in disease models (Trifunovic & Larsson, 2002). Mice with TFAM knockout in pancreatic β-cells develop diabetes from the age of 5 weeks and display mtDNA depletion, deficient oxidative phosphorylation, and abnormal-appearing Mt in neonatal islets (Silva et al., 2000). Overexpression of TFAM in mice protects against delayed neuronal death due to forebrain transient ischemia (Hokari et al., 2010), improves working memory (Hayashi et al., 2008), and protects Mt against β-amyloid-induced oxidative damage (Xu et al., 2009). There is, therefore, a rationale to test the effect of TFAM overexpression in diabetic neuropathy.

TFAM protein plays a dual role. First, TFAM maintains mtDNA copy number by regulating mtDNA replication (Campbell et al., 2012). The copy number of mtDNA correlates with Mt gene expression levels as well as with Mt respiratory activity (D’Erchia et al., 2015). Age-related depletion of mtDNA in human islets contributes to decreased Mt function and risk of type 2 diabetes (Nile et al., 2014). The second role of TFAM is structural. TFAM wraps mtDNA entirely to form a nucleoid structure like histones in the nucleosome (Alam et al., 2003; Ohgaki et al., 2007; Wang, Marinov, Wold, & Chan, 2013) that may also protect mtDNA against ROS (Chakrabarty et al., 2014). Recent results show that it is important to maintain the ratio of TFAM to mtDNA within a narrow range, since small TFAM variations may affect transcription and mtDNA replication (Farge et al., 2014). A small increase in TFAM levels in vivo (~twofold) leads to a proportional increase in mtDNA. In the TFAM transgenic mouse, which overexpresses human TFAM, increased mtDNA levels have been observed in brain tissues (Ikeuchi et al., 2005; Kang et al., 2007). In peripheral DRG neurons, TFAM similarly proportionally increases mtDNA (Chandrasekaran et al., 2015). In all these studies, the TFAM overexpression has been shown to increase only the mtDNA; the Mt mass remains the same, and there is no increase in oxidative phosphorylation or increase in ATP levels (Ikeuchi et al., 2005; Kang et al., 2007). This contrasts with overexpression of the upstream regulator of TFAM, PGC-1α. PGC-1α has the capacity to not only increase mtDNA levels but also increase Mt number both in cultured cells and in vivo in tissues (Lin et al., 2005; Puigserver & Spiegelman, 2003). Similarly, overexpression of the master regulator SIRT1 also increases not only mtDNA levels but also Mt number (Rodgers et al., 2005). A plausible explanation is that both PGC-1α and SIRT1, via PGC-1α, also increase the expression of nuclear DNA-encoded genes, including the nuclear respiratory factors 1 and 2 (Scarpulla, 2011, 2012; Scarpulla, Vega, & Kelly, 2012). These factors in turn stimulate expression of other nDNA-encoded Mt oxidative phosphorylation subunits in addition to the nDNA-encoded TFAM and increase Mt mass. In contrast, TFAM acts only in Mt and increases mtDNA replication and transcription.

Overactivation of PGC-1α or SIRT1 causes deleterious pathological effects. For example, forcing high overexpression of SIRT1 or PGC-1α in transgenic mouse models causes cardiac hypertrophy, whereas moderate overexpression of SIRT1 or PGC-1α is cardioprotective (Alcendor et al., 2007; Goldenthal, 2016). Thus, there appear to be physiological and pathological signals that differentially affect tissue function. Such pathological side effects are not noted in TFAM overexpression model systems. The proposed explanation is that the interaction between TFAM and mtDNA is dynamic and that the presence of one increases the stability of the other. This interaction is most likely beneficial from a regulatory point of view because small changes in TFAM protein levels or mtDNA levels result in rapid adjustment to maintain a constant ratio of TFAM to mtDNA (Farge et al., 2014).

8. Overexpression of human TFAM protects against DPN

The effect of TFAM was tested in a mouse model of type 1 diabetes. Human TFAM (hTFAM) cDNA was used to generate transgenic (Tg) mice (Ikeuchi et al., 2005). A modified chicken β-actin promoter with cytomegalovirus enhancer was used to drive the expression of hTFAM in all tissues. The body weight, blood glucose levels, blood lipid levels, and various neuropathy end-points were measured in animal groups at 6 and 16 weeks (Chandrasekaran et al., 2015). Expression of hTFAM protected mice against diabetic neuropathy as evidenced by preservation of nerve conduction velocity, mechanical allodynia, thermal nociception, and IENF density in diabetic TFAM Tg mice compared to diabetic WT mice. TFAM prevented diabetes-induced slowing of nerve conduction velocity, reduced mechanical allodynia, and loss of IENF. There was no difference in glucose or insulin levels between wild type diabetic and TFAM Tg diabetic mice, even though hTFAM was expressed in all tissues. This is because the promoter is not tissue or cell specific. The protection against peripheral nerve injury is local and independent of glycemic control.

The above study showed that there is a net loss of both mtDNA and TFAM in chronic experimental diabetes (Chandrasekaran et al., 2015). In 6-week diabetic DRG neurons, there is an attempt to upregulate both mtDNA and TFAM, although the increase was not significant. It could be argued that acute exposure to hyperglycemia increases TFAM levels, mtDNA, and Mt biogenesis to meet the high energy demand in neurons. However, in the presence of chronic hyperglycemia with concurrent generation of ROS, the regulation might change from physiological to pathological and eventually lead to an overall decline in mtDNA, TFAM, and Mt function. MtDNA is particularly susceptible to oxidative injury, attributed in part to the following factors: (1) its location within Mt where the respiratory complexes I and III are potential sites for the generation of reactive oxygen (•O2) and (2) the limited repair activity against DNA damage within Mt (Murphy, 2009). Under normal conditions, the toxic effects of ROS are prevented by scavenging enzymes such as MnSOD, GPX, and catalase, in addition to other nonenzymatic antioxidants. However, when production of ROS becomes excessive, or if the levels of antioxidant enzymes decreases, then oxidative stress may have a harmful effect on the functional and structural integrity of biological tissue. Our results showed that the DRG neurons from TFAM Tg mice can scavenge high glucose-induced ROS much more efficiently than the DRG neurons from wild type mice. This scavenging ability in DRG neurons from TFAM Tg mice did not appear to be due to an increase in the expression of the antioxidant enzymes MnSOD and GPX. Our results on Mt respiration also showed no significant increase in ADP-stimulated state 3 or resting state 4 respiration. All these findings suggest that the protective effect of TFAM overexpression is apparent only under chronic conditions of oxidative stress. Results obtained with isolated Mt from other tissues (e.g., heart) using the same hTFAM transgenic mice showed that despite the significant increase in mtDNA copy number in the heart from TFAM Tg mice, Mt respiratory Complex I, Complex II, Complex III, and Complex IV enzymatic activities were similar compared with WT heart Mt (Ikeuchi et al., 2005). In infarcted myocardial (MI) heart Mt from WT mice, the enzymatic activities of Complex I, Complex III, and Complex IV were significantly lower than those from WT-sham. Most importantly, there was no such decrease in the enzymatic activities of Complex I, Complex III, or Complex IV in TFAM Tg Mt (Ikeuchi et al., 2005). These results corroborated our data and demonstrate that the regulation of mtDNA copy number is dissociated from that of electron transport function, although protection is noted in conditions of increased oxidative stress.

The results of our studies on PGC-1α and TFAM are summarized in Fig. 1. PGC-1α knockout exacerbates DPN and this is associated with Mt degeneration and increased oxidative stress. In contrast, TFAM overexpression prevented a decrease in mtDNA copy number in diabetic DRG neurons, helped prevent experimental DPN, protected DRG neurons from oxidative stress, and helped prevent experimental diabetic neuropathy. Certain drug therapies, for example, the mGluR2/3 agonists, increase levels of SIRT1, PGC-1α, and TFAM and may be effective as therapies in diabetic neuropathy (Chandrasekaran et al., 2017).

Fig. 1.

Nuclear gene-encoded regulatory factors are essential for mitochondrial biogenesis and function. The nuclear factors that regulate the expression of nDNA-encoded genes that regulate Mt metabolism and organelle biogenesis are SIRT1 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α). PGC-1α serves as a central component of the transcriptional regulatory circuitry that coordinately controls the energy-generating functions of Mt in accordance with the metabolic demands imposed by changing physiological conditions and disease. SIRT1 is a deacetylase enzyme that deacetylates PGC-1α and increases its activity. Our results show that genetic ablation of PGC-1α exacerbates DPN and is associated with Mt degeneration and increased oxidative stress. In contrast, nDNA-encoded factors such as TFAM act exclusively within the Mt to regulate the control of Mt transcription and replication of mtDNA. TFAM over-expression prevented a decrease in mtDNA copy number in diabetic DRG neurons, helped prevent experimental diabetic neuropathy, and protected DRG neurons from oxidative stress.

9. Administration of the mGluR 2/3 agonist, LY379268, protects against DPN

LY379268 [(−)-2-oxa-4-aminobicyclo(3.1.0)hexane-4,6-dicarboxylic acid] is a highly potent and systemically available mGlu2/3 receptor agonist (Sharpe, Kingston, Lodge, Monn, & Headley, 2002). LY379268 prevents diabetes-induced nerve conduction slowing in both motor and sensory axons, and somatosensory deficits such as mechanical allodynia. The drug also prevented a reduction in the level of the most distal unmyelinated nerve fibers in the hind limb paw epidermis and dermis. In diabetic neuropathy, release of glutamate is associated with increased oxidative stress and decreased Mt function (Anjaneyulu et al., 2008; Berent-Spillson et al., 2004; Berent-Spillson & Russell, 2007; Spillson & Russell, 2003). The glutamate hypothesis of DPN was interrogated by inducing the glutamate reuptake pathway with an mGluR2/3 agonist to elucidate the mechanism of protection. Glutamate is transported to the axon terminals for synaptic release and induces an ionotropic uptake mechanism involving Na+ and Ca2+ ions (Choi, 1992).

Evidence from the peripheral nervous system (PNS) shows that the machinery for production, paracrine release, and recycling of glutamate is present in sensory ganglia including the transport enzymes (GLAST, GLT1) as well as the recycling enzyme (GS) and amidohydrolase (Cangro et al., 1985; Miller, Richards, & Kriebel, 2002; Ohara et al., 2009). This local release is a non-synaptic glutamatergic transmission that occurs within the ganglia. Non-synaptic release of glutamate into the extracellular space within the ganglion is shown in cultured whole ganglia in response to KCl or capsaicin (Jeftinija et al., 1991; Jeftinija, Liu, Jeftinija, & Urban, 1992). Knockdown of glutamate-glutamine recycling enzymes or glutamate transporters results in increased extracellular glutamate (Gong, Kung, Magni, Bhargava, & Jasmin, 2014; Kung et al., 2013). The knockdown was found to be confined to the satellite glial cells (SGC) that are found wrapping the neuronal somata, isolating the ganglion cell bodies (Gong et al., 2014; Ohara et al., 2009). SGC contain all the proteins necessary for the uptake and recycling of glutamate (Jasmin, Vit, Bhargava, & Ohara, 2010; Kung et al., 2013). These findings suggest that glutamatergic transmission within the ganglion could impact the nociceptive threshold. Importantly DRG neurons do express glutamate receptors, including mGluR2/3, in their soma. Thus, in addition to the vesicular transport of glutamate to axon terminals for synaptic release, the DRG neurons release and uptake glutamate for inter-ganglionic glutamatergic communication.

This release of glutamate to DRG neurons may have implications for diabetic neuropathic pain and is a further example of the symbiosis between DRG neuron and satellite or Schwann cell. For example, it is known that glutamate is implicated in the generation and maintenance of neuropathic pain probably through opening of glutamate regulated calcium channels that regulate the hyperexcitability of nociceptive neurons (Fernandez-Montoya, Avendano, & Negredo, 2017). Glutamate carboxypeptidase II inhibitors reduce hydrolysis of the neuropeptide NAAG to NAA and glutamate and have been shown to significantly reduce thermally-induced pain in animal models of diabetic neuropathy (Zhang et al., 2002). These inhibitors also normalize the slowing observed in motor conduction velocities. The exact mechanism by which drugs that block generation of glutamate, or inhibit mGluR2/3, affect the nerve conduction velocity in motor or sensory axons is uncertain. Both types of drugs will increase levels of glutathione (Berent-Spillson & Russell, 2007; Spillson & Russell, 2003) and this may reduce the effect of ROS on the aldose reductase pathway and in turn reduce polyol flux in the peripheral nerve (Ho et al., 2006). The effect of increasing myoinositol in the peripheral nerve in diabetes is to significantly decrease levels of cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate [cAMP] (Shindo, Tawata, Aida, & Onaya, 1992). This in turn will reduce the speed of salutatory conduction in both myelinated sensory and motor axons. Aldose reductase inhibitors will reduce polyol flux, increase cAMP (Shindo et al., 1992) and increase nerve conduction velocity.

Results from several investigators have shown GFAP to be present at barely detectable levels in normal DRG. Diabetes markedly increases GFAP levels, suggesting that the increase may represent induction of gliopathic pain (Jasmin et al., 2010; Ohara et al., 2009). Treatment with the mGluR2/3 agonist, LY379268, prevented increased GFAP levels. The increase in GFAP is likely to represent differentiation of SGC as a response to increased glutamate release in diabetes. The decrease in levels of glutamate transporters and recycling proteins are likely to exacerbate the glutamate accumulation and further increase GFAP levels. All these changes were reversed in rats treated with an mGluR2/3 agonist. A mechanistic model is shown in Fig. 2. Hyperglycemia induces oxidative stress and promotes release of glutamate from DRG neurons. While glutamate is increased in the DRG neurons and extra neuronal space (Berent-Spillson & Russell, 2007; Chandrasekaran et al., 2017), this does not imply an increase in spinal axonal glutamate that would increase pain signaling. Potentially, diabetes induced release of intracellular glutamate into the extracellular pool may ultimately deplete the DRG neuronal pool and decrease activation of glutamate receptors. However, it is known that after axonal injury, there is a downregulation of metabotropic receptors that inhibit or decrease neuronal excitability, whereas there is concomitant upregulation of ionotropic receptors that mediate an enhancement of neurotransmitter release and/or neuronal excitability (Zimmermann, 2001). Overall, these changes may lead to potentiation of primary afferent input that plays a significant role in the development of pain sensitization and perpetuation. This will occur despite a decrease in spinal glutamate release (Malmberg, O’Connor, Glennon, Cesena, & Calcutt, 2006).

Fig. 2.

The role of satellite ganglion cells (SGC) and dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons in glutamate recycling. Glutamate transporters GLT-1 and GLAST are present in SGC to import extracellular glutamate, for conversion to glutamine by glutamine synthetase (GS). Glutamine is eventually recycled to the neuron for conversion into glutamate. Hyperglycemia induces oxidative stress, and promotes release of glutamate from DRG neurons. In diabetes, GSH is decreased and hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress affects glutamate transport proteins, increasing extracellular glutamate, causing expansion of GFAP positive SGC. LY379268 treatment promotes glutamate uptake and is therefore likely to decrease extracellular glutamate, preventing expansion of GFAP-positive SGC cells. Thus, activation of the mGluR2/3 receptor with an agonist likely constrains sensory transmission, glutamate release and importantly nociceptive transmission. This allows modification of glutamate-induced receptor potentials before impulses are generated and transmitted to the spinal cord.

LY 379268 treatment removes extracellular glutamate by activating the glutamate recycling pathway to decrease excitability of the neurons and promote neuroprotection (Chandrasekaran et al., 2017). We propose a mechanism that LY379268 activates glutamate recycling pathways in surrounding satellite glial cells (SGC), normalizes neuronal Mt OXPHOS metabolism and prevents development of neuropathy. GFAP is one of the markers that we used to advance this hypothesis of increased glutamate recycling: diabetes increases GFAP positive SGC and LY379268 treatment decreased GFAP positive cells. The mechanism suggested in our study is supported by findings from other studies. There are three known glutamate transporter proteins: GLAST, GLT1, and EAAC1. SGC expresses GLAST1 and GLT1, whereas EAAC1 is expressed in neurons (Carozzi et al., 2008, 2011). Sciatic nerve injury decreases expression of GLAST and GLT-1 (Sung, Lim, & Mao, 2003). This decrease in glutamate transport causes an increase in extracellular glutamate, which in turn is associated with neuropathic pain (Sung et al., 2003). Rapid removal of glutamate from the perineuronal space prevents the cytotoxic effects of glutamate (Choi, 1992). SGC cells convert glutamate to glutamine using the enzyme glutamine synthetase (GS) and glutamine is then taken up by neurons through glutamine transporters and converted back to glutamate to be reused. mGluR2/3 receptors, present in DRG neurons, can further reduce the levels of extracellular glutamate. Both neurons and SGC can eliminate the toxicity of extracellular glutamate.

The synthesis of glutathione (GSH) involves two steps, ligation of glutamate with cysteine to form gamma-glutamyl-cysteine and the addition of glycine to the c-terminus to form GSH. This pathway exists in both neurons and SGC. GSH made by SGC is secreted to the intracellular space and taken up by neurons to replenish GSH (Johnson, Wilson-Delfosse, & Mieyal, 2012). This is consistent with previous findings in which exposure to a mGluR2/3 agonist prevents glucose-induced neuronal injury in DRG neuronal cultures, only in the presence of Schwann/SGC cells, by increasing glutathione and maintaining Mt function (Berent-Spillson et al., 2004; Berent Spillson & Russell, 2003, 2007). NMDA receptor antagonists are not as protective as mGluR2/3 agonists, suggesting that ionotropic pathways are not involved in this mechanism (Anjaneyulu et al., 2008; Berent-Spillson et al., 2004; Berent-Spillson & Russell, 2007). Results from western blots of Mt transcription factors and OXPHOS proteins suggest that the physiological response to diabetic injury is insufficient to protect DRG neurons. Levels of SIRT1, PGC-1α, and TFAM were increased in DRG from subacutely diabetic animals (Chandrasekaran et al., 2017). In contrast, levels of PGC-1α and TFAM were decreased in more chronic diabetes (Choi, Chandrasekaran, Inoue, et al., 2014). This suggests that the Mt machinery responds to hyperglycemia-induced injury to DRG, albeit insufficiently to protect them. Recycling of glutamate with LY379268 further increased levels of SIRT1, PGC-1α, and TFAM (Chandrasekaran et al., 2017). This increase occurred despite LY379268-treated diabetic rats being hyperglycemic. Even though levels of TFAM were observed to be increased, our results showed a significant decrease in overall DRG mtDNA levels. A plausible explanation for the paradoxical increase in TFAM with decreased mtDNA levels can be attributed to an increase in protein oxidation, notwithstanding hyperglycemia induced physiological upregulation of TFAM. These results would suggest that despite increases in the levels of TFAM, TFAM was ubiquitinated causing it to be nonfunctional and thus preventing TFAM-induced mtDNA replication and transcription (Santos, Mishra, & Kowluru, 2014).

Our hypothesis is summarized in Fig. 2. Overall, the data indicates that use of a selective mGluR2/3 agonist is effective in reducing the severity of diabetic neuropathy. The mechanism of protection is likely to involve presynaptic glutamate release, glutamate uptake, conversion of glutamate to glutamine to provide precursors for GSH synthesis, and substrate for neuronal Mt oxidative metabolism. Subsequently, improved Mt function with LY379269 is associated with upregulation of the SIRT1–PGC-1α–TFAM axis.

10. Role of NAD+ analogues in DPN

A significant advance made in unlocking the underlying molecular mechanisms of axonal degeneration was recognizing the importance of NAD+ in regulating axonal maintenance, degeneration and regeneration (Di Stefano & Conforti, 2013; Gerdts, Summers, Milbrandt, & DiAntonio, 2016; Sasaki, 2018; Wang & He, 2009). NAD(H) furnishes reducing equivalents to the Mt electron transport chain to generate ATP. However, NAD+ also acts as a degradation substrate for enzymes such as Sirtuins, Poly (ADP-ribosyl) transferase 1 (PARP1) and a Cluster of Differentiation 38 (CD38) (Mouchiroud, Houtkooper, & Auwerx, 2013; Yang & Sauve, 2016; Yoshino, Baur, & Imai, 2018). In cellular and animal models, activation of proteins that either deplete NAD+ levels, like PARP1 and CD38 or regulate NAD+ metabolism such as Sterile Alpha and TIR Motif—constraining 1 (SARM1) or inhibit Sirtuin 1 such as Deleted in Bladder Cancer protein1 (DBC1) promote axonal degeneration (Geisler et al., 2016; Osterloh et al., 2012; Turkiew, Falconer, Reed, & Höke, 2017). In contrast, knockout of PARP1, CD38, and SARM1 protects mice against high fat diet (HFD) or chemotherapy-induced neuropathy (Barbosa et al., 2007; Escande et al., 2015; Obrosova et al., 2008; Sasaki, Nakagawa, Mao, DiAntonio, & Milbrandt, 2016; Turkiew et al., 2017). Proteins that resynthesize NAD+ via the salvage pathway such as NMNAT1 to 3, protect against axonal degeneration (Araki, Sasaki, & Milbrandt, 2004; Babetto et al., 2010; Di Stefano et al., 2017; Gilley & Coleman, 2010; Press & Milbrandt, 2008; Sasaki, Vohra, Baloh, & Milbrandt, 2009; Yahata, Yuasa, & Araki, 2009). More recently nicotinamide riboside (NR) was administered to prediabetic and type 2 diabetic mice. NR improved glucose tolerance, reduced weight gain, liver damage and the development of hepatic steatosis in prediabetic mice while protecting against sensory and motor neuropathy (Trammell et al., 2016). The neuroprotective effect of NR could not be explained by improved glycemic control alone because NR has virtually no effect on the HBA1C or the non fasting glucose in high fat diet (HFD) fed mice. However, NR did decrease fasting glucose and non-fasting glucose in HFD with streptozotocin (STZ)-treated mice. Hepatic NADP(+) and NADPH levels were significantly decreased in prediabetic and type 2 diabetic animals but were reversed when mice were supplemented with NR. Thus, dietary supplementation with precursors of NAD+ protect against HFD-induced neuropathy (Trammell et al., 2016).

11. The choice of NAD+ precursor is critical

The precursors of NAD+ are Nicotinamide (NAM), Nicotinic Acid (NA), nicotinamide riboside (NR) and Nicotinamide Mononucleotide (NMN). NAM was first associated with diabetes when it was shown to protect against streptozotocin-induced diabetes (Schein, Cooney, & Vernon, 1967). NAM, but not Nicotinic Acid (NA), can recover this drop in NAD+ levels (Ho & Hashim, 1972). It was demonstrated that the NAD+ reduction induced in diabetes was due to increased DNA damage, stimulating PARP1 activity (Yamamoto, Uchigata, & Okamoto, 1981). More recently, Otsuka Long Evans Tokushima Fatty (OLETF) rats, a rodent model of obesity and type 2 diabetes, exhibited profound metabolic improvements following NAM treatment (100mg/kg for 4 weeks). NAM treatment induced liver NAD+ levels, which were complimented by enhanced glucose control (Yang et al., 2014). Despite NAM being suggested as a treatment for type 1 diabetes (Olmos et al., 2006), clinical trials failed to confirm this hypothesis (Cabrera-Rode et al., 2006; Gale, Bingley, Emmett, Collier, & European Nicotinamide Diabetes Intervention Trial (ENDIT) Group, 2004).

Reports indicate that long-term or high doses of NAM are detrimental because they favor the development of a fatty liver, due to reductions in available methyl groups (Kang-Lee et al., 1983). For instance, NAM administration for 8 weeks (1000mg/kg) resulted in methyl group deficiency, which is likely due to the conversion of NAM into 1-methyl-NAM (mNAM or MNA) by nicotinamide n-methyltransferase (NNMT). NNMT shunts NAM away from NAD+ using S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) as a methyl donor (Aksoy, Szumlanski, & Weinshilboum, 1994; Riederer, Erwa, Zimmermann, Frank, & Zechner, 2009). In line with this hypothesis, supplementation of methionine, a methyl group donor, prevented the formation of steatohepatosis caused by high doses of NAM (Kang-Lee et al., 1983). Recently, NNMT expression was found to be negatively correlated with GLUT4, the insulin-responsive glucose transporter, in adipose tissue (Kraus et al., 2014). In adipose-specific Glut4-KO mice, NNMT transcripts are increased, conversely NNMT transcripts are reduced in adipose-specific Glut4-overexpressing mice (Kraus et al., 2014). Similarly, NNMT transcripts were increased in the White Adipose Tissue (WAT) of ob/ob, db/db, and HFD fed mice compared to lean insulin sensitive controls (Kraus et al., 2014). In addition, tissue specific knockdown of NNMT in WAT and liver, using antisense oligonucleotides, protected against diet-induced obesity by increasing the expression of SIRT1 target genes and energy expenditure. Interventions improving insulin sensitivity—e.g., exercise or bariatric surgery—were associated with a significant reduction in WAT NNMT expression. Bariatric surgery was also associated with a significant decrease in plasma MNA, due to less absorption of NAM from the diet and less conversion to MNA and more toward NAD+ synthesis (Kannt et al., 2015).

NAD+ cannot be given directly because of its toxic effects that include serious hyperglycemia lasting for hours. NAM exerts end-product inhibition on SIRT1 deacetylase activity, whereas another source of NAD+, NA, often leads to severe flushing, mediated by the binding of nicotinic acid to the GPR109A receptor (Benyo et al., 2005; Bogan & Brenner, 2008). Therefore, NAD+ precursors that do not activate GPR109A (Tunaru et al., 2003) but still increase NAD+ levels, such as NR and NMN, are more likely to be clinically useful. The estimated total intracellular content of NAD+ is in the 0.2–0.5mM range (Houtkooper, Canto, Wanders, & Auwerx, 2010; Sauve, Wolberger, Schramm, & Boeke, 2006), which lies within the estimated Km values of SIRT1 for NAD+. NAD+ in peripheral DRG neurons in diabetic rats is decreased and levels of NAD+ lie in the lower end of the Km value of the SIRT1 enzyme, thus linking depleted NAD+ to DPN and impaired SIRT1 activation (Chandrasekaran, Chen, Sagi, & Russell, 2016). One such compound is NR that is well tolerated and orally bioavailable and protects against both sensory and motor neuropathy (Trammell et al., 2016).

12. SIRT1 and DPN

Activators of SIRT1, such as resveratrol, have been shown to prime the Mt by increasing its reserve capacity to combat Mt stress under diabetic conditions (Roy Chowdhury et al., 2012). Administration of resveratrol (an activator of SIRT1 and AMPK) in cultured adult rat DRG neurons was also shown to increase neurite outgrowth compared to untreated cultures (Chowdhury et al., 2011; Dasgupta & Milbrandt, 2007; Roy Chowdhury et al., 2012). SIRT1 activation confers neuroprotection in experimental neuritis (Shindler, Ventura, Rex, Elliott, & Rostami, 2007). Furthermore, we have shown that overexpression of SIRT1 in neurons reduces demyelination and axonal injury and improves clinical symptoms in EAE-induced demyelination (Nimmagadda et al., 2013), suggesting a critical role for SIRT1 in axon development and maintenance. Diabetic peripheral axonal pathology includes retraction of terminal nerve endings and alterations in the peripheral terminals of sensory neurons located in the epidermis (Biessels et al., 2014). Axonal degeneration is prevented by upregulation of the NAD+ synthetic enzyme NMNAT2 (Gerdts et al., 2016). Furthermore, preliminary studies show that SIRT1, which is upregulated by the NAD+ precursors NMN or NR (Fig. 3), is able to prevent and reverse DPN through improving Mt oxidative metabolism (Chandrasekaran et al., 2016, 2018).

Fig. 3.

Regulation of SIRT1 by Nicotinamide Mononucleotide (NMN). NMN increases NAD+ levels that are reduced by a high fat diet (HFD) in models of type 2 diabetes. In the nucleus, NAD+ is consumed by SIRT1 to deacetylate activators of transcription such as PGC-1α. PGC-1α in turn promotes transcriptional regulation of genes that promote Mt biogenesis, fatty acid metabolism, activate anti-oxidant responses and thus decrease oxidative injury.

Another member of the sirtuin family, SIRT2, is downregulated in DRG from diabetic mice and is important in inducing neurite growth (Schartner et al., 2018). SIRT2 expression is decreased in DRG from type 1 diabetic mice due to enhancement of polyol pathway activity. Over-expression of SIRT2 increased neurite outgrowth in culture in both control and diabetic DRG. SIRT2 expression, P-AMPK levels, levels of respiratory Complexes II/III and respiratory capacity were significantly decreased after exposure to high glucose. Treatment with aldose reductase inhibitors increased expression of SIRT2, P-AMPK/PGC-1α and increased neurite outgrowth.

In summary, the studies suggest that SIRT1 and SIRT2 are decreased in diabetic DRG and overexpression can increase axonal outgrowth. Neuronal overexpression of SIRT1 enhances the SIRT1/PGC-1α axis in neurons and protects against DPN. The bioenergetics profile of DRG neurons from NMN-treated DRG neurons show higher maximal respiratory capacity with neuronal SIRT1 overexpression. In addition to addressing a potential pathogenic pathway in diabetic neuropathy, this suggests that medications that would prevent NAD+ depletion induced by diabetes mellitus and would activate SIRT1 may provide a therapeutic intervention for diabetic neuropathy.

13. Conclusion

The NAD+-Dependent SIRT1–PGC-1α–TFAM pathway is important in regulating mitochondrial function. PGC-1α and SIRT1 are present inside Mt and are in close proximity to mtDNA. Within the Mt, PGC-1α and SIRT1 can regulate oxidative phosphorylation and transcriptionally activate TFAM, which wraps around the Mt DNA to provide protection against oxidative injury by ROS. As expected, based on this concept, knockout of PGC-1α exacerbates DPN, whereas overexpression of human TFAM is protective. Certain drugs are able to upregulate this pathway and may provide protection in DPN. For example, selective metabolomic glutamate receptor 2/3 (mGluR2/3) receptor agonists and NR show protection in DPN. Despite these promising findings, we need to better understand the long-term regulation of the SIRT1–PGC-1α–TFAM pathway and whether protection can be sustained and DPN can be reversed.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health 1R01DK107007–01A1, Office of Research Development, Department of Veterans Affairs (Biomedical and Laboratory Research Service and Rehabilitation Research and Development, 101RX001030), Diabetes Action Research and Education Foundation, University of Maryland Institute for Clinical & Translational Research (ICTR) and the Baltimore GRECC (J.W.R.), 1K08NS102468–01A1 (C-Y.H.) and the Atlantic Nutrition Obesity Research Center, Grant P30 DK072488 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

References

- Aksoy S, Szumlanski CL, & Weinshilboum RM (1994). Human liver nicotinamide N-methyltransferase. cDNA cloning, expression, and biochemical characterization. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 269, 14835–14840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam TI, Kanki T, Muta T, Ukaji K, Abe Y, Nakayama H, et al. (2003). Human mitochondrial DNA is packaged with TFAM. Nucleic Acids Research, 31(6), 1640–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcendor RR, Gao S, Zhai P, Zablocki D, Holle E, Yu X, et al. (2007). Sirt1 regulates aging and resistance to oxidative stress in the heart. Circulation Research, 100(10), 1512–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrulionyte L, Kuulasmaa T, Chiasson JL, & Laakso M (2007). Single nucleotide polymorphisms of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha gene (PPARA) influence the conversion from impaired glucose tolerance to type 2 diabetes: The STOP-NIDDM trial. Diabetes, 56(4), 1181–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrulionyte L, Zacharova J, Chiasson JL, & Laakso M (2004). Common polymorphisms of the PPAR-gamma2 (Pro12Ala) and PGC-1alpha (Gly482Ser) genes are associated with the conversion from impaired glucose tolerance to type 2 diabetes in the STOP-NIDDM trial. Diabetologia, 47(12), 2176–2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang L, Jaiswal M, Martin C, & Pop-Busui R (2014). Glucose control and diabetic neuropathy: Lessons from recent large clinical trials. Current Diabetes Reports, 14(9), 528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anjaneyulu M, Berent-Spillson A, & Russell JW (2008). Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) and diabetic neuropathy. Current Drug Targets, 9(1), 85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquilano K, Baldelli S, Pagliei B, & Ciriolo MR (2013). Extranuclear localization of SIRT1 and PGC-1alpha: An insight into possible roles in diseases associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. Current Molecular Medicine, 13(1), 140–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquilano K, Vigilanza P, Baldelli S, Pagliei B, Rotilio G, & Ciriolo MR (2010). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma co-activator 1 alpha (PGC-1{alpha}) and sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) reside in mitochondria: Possible direct function in mitochondrial biogenesis. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 285, 21590–21599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki T, Sasaki Y, & Milbrandt J (2004). Increased nuclear NAD biosynthesis and SIRT1 activation prevent axonal degeneration. see comment Science, 305(5686), 1010–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attardi G (1985). Animal mitochondrial DNA: An extreme example of genetic economy. International Review of Cytology, 93, 93–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babetto E, Beirowski B, Janeckova L, Brown R, Gilley J, Thomson D, et al. (2010). Targeting NMNAT1 to axons and synapses transforms its neuroprotective potency in vivo. The Journal of Neuroscience, 30(40), 13291–13304. 10.1523/jneurosci.1189-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baier L, Kovacs P, Wiedrich C, Cray K, Schemidt A, Shen GQ, et al. (2002). Positional cloning of an obesity/diabetes susceptibility gene(s) on chromosome 11 in Pima Indians. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 967, 258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa MT, Soares SM, Novak CM, Sinclair D, Levine JA, Aksoy P, et al. (2007). The enzyme CD38 (a NAD glycohydrolase, EC 3.2.2.5) is necessary for the development of diet-induced obesity. FASEB Journal, 21(13), 3629–3639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benyo Z, Gille A, Kero J, Csiky M, Suchankova MC, Nusing RM, et al. (2005). GPR109A (PUMA-G/HM74A) mediates nicotinic acid-induced flushing. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 115(12), 3634–3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berent-Spillson A, Robinson A, Golovoy D, Slusher B, Rojas C, & Russell JW (2004). Protection against glucose-induced neuronal death by NAAG and GCP II inhibition is regulated by mGluR3. Journal of Neurochemistry, 89, 90–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berent-Spillson A, & Russell JW (2007). Metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 protects neurons from glucose-induced oxidative injury by increasing intracellular glutathione concentration. Journal of Neurochemistry, 101(2), 342–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besseiche A, Riveline JP, Gautier JF, Breant B, & Blondeau B (2015). Metabolic roles of PGC-1alpha and its implications for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes & Metabolism, 41(5), 347–357. 10.1016/j.diabet.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestwick ML, & Shadel GS (2013). Accessorizing the human mitochondrial transcription machinery. Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 38(6), 283–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biessels GJ, Bril V, Calcutt NA, Cameron NE, Cotter MA, Dobrowsky R, et al. (2014). Phenotyping animal models of diabetic neuropathy: A consensus statement of the diabetic neuropathy study group of the EASD (Neurodiab). Journal of the Peripheral Nervous System, 19(2), [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogan KL, & Brenner C (2008). Nicotinic acid, nicotinamide, and nicotinamide riboside: A molecular evaluation of NAD+ precursor vitamins in human nutrition. Annual Review of Nutrition, 28, 115–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Rode E, Molina G, Arranz C, Vera M, González P, Suárez R, et al. (2006). Effect of standard nicotinamide in the prevention of type 1 diabetes in first degree relatives of persons with type 1 diabetes. Autoimmunity, 39, 333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CT, Kolesar JE, & Kaufman BA (2012). Mitochondrial transcription factor A regulates mitochondrial transcription initiation, DNA packaging, and genome copy number. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1819(9–10), 921–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cangro CB, Sweetnam PM, Wrathall JR, Haser WB, Curthoys NP, & Neale JH (1985). Localization of elevated glutaminase immunoreactivity in small DRG neurons. Brain Research, 336(1), 158–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canto C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Feige JN, Lagouge M, Noriega L, Milne JC, et al. (2009). AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature, 458(7241), 1056–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carozzi VA, Canta A, Oggioni N, Ceresa C, Marmiroli P, Konvalinka J, et al. (2008). Expression and distribution of ‘high affinity’ glutamate transporters GLT1, GLAST, EAAC1 and of GCPII in the rat peripheral nervous system. Journal of Anatomy, 213(5), 539–546. 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00984.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carozzi VA, Zoia CP, Maggioni D, Verga E, Marmiroli P, Ferrarese C, et al. (2011). Expression, distribution and glutamate uptake activity of high affinity-excitatory aminoacid transporters in in vitro cultures of embryonic rat dorsal root ganglia. Neuroscience, 192, 275–284. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarty S, D’Souza RR, Kabekkodu SP, Gopinath PM, Rossignol R, & Satyamoorthy K (2014). Upregulation of TFAM and mitochondria copy number in human lymphoblastoid cells. Mitochondrion, 15, 52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran K, Anjaneyulu M, Inoue T, Choi J, Sagi AR, Chen C, et al. (2015). Mitochondrial transcription factor A regulation of mitochondrial degeneration in experimental diabetic neuropathy. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism, 309(2), E132–E141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran K, Chen C, Sagi AR, & Russell JW (2016). A nicotinamide adenine nucleotide (NAD+) precursor is a potential therapy for diabetic neuropathy. Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases, 3(1), S86. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran K, Ho CY, Salimian M, Kumar P, Reddy SS, & Russell JW (2018). Increased deacetylation of proteins by Sirtuin 1 protein over expression reverses T2D peripheral neuropathy (abstract). Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases, 5(S1), 253. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran K, Muragundla A, Demarest TG, Choi J, Sagi AR, Najimi N, et al. (2017). mGluR2/3 activation of the SIRT1 axis preserves mitochondrial function in diabetic neuropathy. Annals of Clinical Translational Neurology, 4(12), 844–858. 10.1002/acn3.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, Huang Y, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Ohlrogge AW, et al. (2018). IDF diabetes atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 138, 271–281. 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW (1992). Excitotoxic cell-death. Journal of Neurobiology, 23(9), 1261–1276. 10.1002/neu.480230915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Chandrasekaran K, Demarest TG, Kristian T, Xu S, Vijaykumar K, et al. (2014). Brain diabetic neurodegeneration segregates with low intrinsic aerobic capacity. Annals of Clinical Translational Neurology, 1(8), 589–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Chandrasekaran K, Inoue T, Muragundla A, & Russell JW (2014). PGC-1α regulation of mitochondrial degeneration in experimental diabetic neuropathy. Neurobiology of Disease, 64, 118–130. 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Ravipati A, Nimmagadda V, Schubert M, Castellani R, & Russell JW (2014). Potential roles of PINK1 for increased PGC-1α-mediated mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and their associations with Alzheimer disease and diabetes. Mitochondrion, 18, 41–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury SK, Dobrowsky RT, & Fernyhough P (2011). Nutrient excess and altered mitochondrial proteome and function contribute to neurodegeneration in diabetes. Mitochondrion, 11(6), 845–854. 10.1016/j.mito.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury SK, Smith DR, & Fernyhough P (2013). The role of aberrant mitochondrial bioenergetics in diabetic neuropathy. Neurobiology of Disease, 51, 56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton DA (2000). Transcription and replication of mitochondrial DNA. Human Reproduction, 15, 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MA, Menta BW, Perez-Sanchez C, Jack MM, Khan ZW, Ryals JM, et al. (2018). A ketogenic diet reduces metabolic syndrome-induced allodynia and promotes peripheral nerve growth in mice. Experimental Neurology, 306, 149–157. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowell RM, Blake KR, Inoue T, & Russell JW (2007). PGC-1á and PGC-1á-responsive genes are upregulated during Forskolin-induced Schwann cell differentiation. Neuroscience Letters, 439, 269–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowell RM, Blake KR, & Russell JW (2007). Localization of the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha to GABAergic neurons during maturation of the rat brain. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 502, 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowell R, & Russell JW (2003). Nitrosative injury and antioxidative therapy in the management of diabetic neuropathy. Journal of Investigative Medicine, 52, 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowell RM, & Russell JW (2004). Peripheral neuropathy and the Schwann cell In Kettenmann H & Ransom BR (Eds.), Neuroglia (2nd ed., pp. 573–585): Oxford University Press; Reprinted from: Not in File. [Google Scholar]

- Cowell RM, Talati P, Blake KR, Meador-Woodruff JH, & Russell JW (2009). Identification of novel targets for PGC-1alpha and histone deacetylase inhibitors in neuroblastoma cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 379(2), 578–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta B, & Milbrandt J (2007). Resveratrol stimulates AMP kinase activity in neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(17), 7217–7222. 10.1073/pnas.0610068104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DCCT. (1993). The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The diabetes control and complications trial research group. The New England Journal of Medicine, 329, 977–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney CL, Russell JW, Cheng H-L, & Feldman EL (2001). Insulin-like growth factor-I and over-expression of Bcl-xL prevent glucose-mediated apoptosis in Schwann cells. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology, 60, 147–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Erchia AM, Atlante A, Gadaleta G, Pavesi G, Chiara M, De Virgilio C, et al. (2015). Tissue-specific mtDNA abundance from exome data and its correlation with mitochondrial transcription, mass and respiratory activity. Mitochondrion, 20, 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano M, & Conforti L (2013). Diversification of NAD biological role: The importance of location. The FEBS Journal, 280(19), 4711–4728. 10.1111/febs.12433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano M, Loreto A, Orsomando G, Mori V, Zamporlini F, Hulse RP, et al. (2017). NMN deamidase delays Wallerian degeneration and rescues axonal defects caused by NMNAT2 deficiency in vivo. Current Biology, 27(6), 784–794. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDIC. (2003). Sustained effect of intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes mellitus on development and progression of diabetic nephropathy: The epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications (EDIC) study. JAMA, 290(16), 2159–2167. 10.1001/jama.290.16.2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escande C, Nin V, Pirtskhalava T, Chini CC, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL, et al. (2015). Deleted in breast cancer 1 limits adipose tissue fat accumulation and plays a key role in the development of metabolic syndrome phenotype. Diabetes, 64(1), 12–22. 10.2337/db14-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farge G, Mehmedovic M, Baclayon M, van den Wildenberg SM, Roos WH, Gustafsson CM, et al. (2014). In vitro-reconstituted nucleoids can block mitochondrial DNA replication and transcription. Cell Reports, 8(1), 66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Montoya J, Avendano C, & Negredo P (2017). The glutamatergic system in primary somatosensory neurons and its involvement in sensory input-dependent plasticity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(1). 10.3390/ijms19010069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernyhough P (2015). Mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic neuropathy: A series of unfortunate metabolic events. Current Diabetes Reports, 15(11), 89–0671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale EA, Bingley PJ, Emmett CL, Collier T, & European Nicotinamide Diabetes Intervention Trial (ENDIT) Group (2004). European Nicotinamide Diabetes Intervention Trial (ENDIT): a randomised controlled trial of intervention before the onset of type 1 diabetes. Lancet, 363, 925–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garesse R, & Vallejo CG (2001). Animal mitochondrial biogenesis and function: A regulatory cross-talk between two genomes. Gene, 263(1–2), 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler S, Doan RA, Strickland A, Huang X, Milbrandt J, & DiAntonio A (2016). Prevention of vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy by genetic deletion of SARM1 in mice. Brain, 139(Pt 12), 3092–3108. 10.1093/brain/aww251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdts J, Summers DW, Milbrandt J, & DiAntonio A (2016). Axon self-destruction: New links among SARM1, MAPKs, and NAD+ metabolism. Neuron, 89(3), 449–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilley J, & Coleman MP (2010). Endogenous Nmnat2 is an essential survival factor for maintenance of healthy axons. PLoS Biology, 8(1), e1000300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffart S, & Wiesner RJ (2003). Regulation and co-ordination of nuclear gene expression during mitochondrial biogenesis. Experimental Physiology, 88(1), 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenthal MJ (2016). Mitochondrial involvement in myocyte death and heart failure. Heart Failure Reviews, 21(2), 137–155. 10.1007/s10741-016-9531-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong KR, Kung LH, Magni G, Bhargava A, & Jasmin L (2014). Increased response to glutamate in small diameter dorsal root ganglion neurons after sciatic nerve injury. PLoS One, 9(4), e95491 [doi:ARTN]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y, Yoshida M, Yamato M, Ide T, Wu Z, Ochi-Shindou M, et al. (2008). Reverse of age-dependent memory impairment and mitochondrial DNA damage in microglia by an overexpression of human mitochondrial transcription factor A in mice. The Journal of Neuroscience, 28(34), 8624–8634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilbronn LK, Gregersen S, Shirkhedkar D, Hu D, & Campbell LV (2007). Impaired fat oxidation after a single high-fat meal in insulin-sensitive nondiabetic individuals with a family history of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes, 56(8), 2046–2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinder LM, O’Brien PD, Hayes JM, Backus C, Solway AP, Sims-Robinson C, et al. (2017). Dietary reversal of neuropathy in a murine model of prediabetes and metabolic syndrome. Disease Models & Mechanisms, 10(6), 717–725. 10.1242/dmm.028530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho CK, & Hashim SA (1972). Pyridine nucleotide depletion in pancreatic islets associated with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Diabetes, 21(7), 789–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho EC, Lam KS, Chen YS, Yip JC, Arvindakshan M, Yamagishi S, et al. (2006). Aldose reductase-deficient mice are protected from delayed motor nerve conduction velocity, increased c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation, depletion of reduced glutathione, increased superoxide accumulation, and DNA damage. Diabetes, 55(7), 1946–1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokari M, Kuroda S, Kinugawa S, Ide T, Tsutsui H, & Iwasaki Y (2010). Over-expression of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) ameliorates delayed neuronal death due to transient forebrain ischemia in mice. Neuropathology, 30(4), 401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtkooper RH, Canto C, Wanders RJ, & Auwerx J (2010). The secret life of NAD +: An old metabolite controlling new metabolic signaling pathways. Endocrine Reviews, 31(2), 194–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeuchi M, Matsusaka H, Kang D, Matsushima S, Ide T, Kubota T, et al. (2005). Overexpression of mitochondrial transcription factor A ameliorates mitochondrial deficiencies and cardiac failure after myocardial infarction. Circulation, 112(5), 683–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager S, Handschin C, St-Pierre J, & Spiegelman BM (2007). AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) action in skeletal muscle via direct phosphorylation of PGC-1alpha. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(29), 12017–12022. 10.1073/pnas.0705070104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasmin L, Vit JP, Bhargava A, & Ohara PT (2010). Can satellite glial cells be therapeutic targets for pain control? Neuron Glia Biology, 6(1), 63–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeftinija S, Jeftinija K, Liu F, Skilling SR, Smullin DH, & Larson AA (1991). Excitatory amino acids are released from rat primary afferent neurons in vitro. Neuroscience Letters, 125(2), 191–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeftinija S, Liu F, Jeftinija K, & Urban L (1992). Effect of capsaicin and resiniferatoxin on peptidergic neurons in cultured dorsal root ganglion. Regulatory Peptides, 39(2–3), 123–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong-Yu S, & Clayton DA (1996). Regulation and function of the mitochondrial genome. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease, 19(4), 443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Kang SU, Zhang S, Karuppagounder S, Xu J, Lee YK, et al. (2016). Adult conditional knockout of PGC-1alpha leads to loss of dopamine neurons. eNeuro, 3(4). 10.1523/ENEURO.0183-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WM, Wilson-Delfosse AL, & Mieyal JJ (2012). Dysregulation of glutathione homeostasis in neurodegenerative diseases. Nutrients, 4(10), 1399–1440. 10.3390/nu4101399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johri A, Calingasan NY, Hennessey TM, Sharma A, Yang L, Wille E, et al. (2012). Pharmacologic activation of mitochondrial biogenesis exerts widespread beneficial effects in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Human Molecular Genetics, 21(5), 1124–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jornayvaz FR, & Shulman GI (2010). Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Essays in Biochemistry, 47, 69–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang I, Chu CT, & Kaufman BA (2018). The mitochondrial transcription factor TFAM in neurodegeneration: Emerging evidence and mechanisms. FEBS Letters, 592(5), 793–811. 10.1002/1873-3468.12989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang D, Kim SH, & Hamasaki N (2007). Mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM): Roles in maintenance of mtDNA and cellular functions. Mitochondrion, 7(1–2), 39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang-Lee YA, McKee RW, Wright SM, Swendseid ME, Jenden DJ, & Jope RS (1983). Metabolic effects of nicotinamide administration in rats. Journal of Nutrition, 113, 215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannt A, Pfenninger A, Teichert L, Tonjes A, Dietrich A, Schon MR, et al. (2015). Association of nicotinamide-N-methyltransferase mRNA expression in human adipose tissue and the plasma concentration of its product, 1- methylnicotinamide, with insulin resistance. Diabetologia, 58(4), 799–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly DP, & Scarpulla RC (2004). Transcriptional regulatory circuits controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Genes & Development, 18(4), 357–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner S, Mepani RJ, Laznik D, Ye L, Jurczak MJ, Jornayvaz FR, et al. (2012). Development of insulin resistance in mice lacking PGC-1alpha in adipose tissues. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(24), 9635–9640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobilo T, Guerrieri D, Zhang Y, Collica SC, Becker KG, & van Praag H (2014). AMPK agonist AICAR improves cognition and motor coordination in young and aged mice. Learning & Memory, 21(2), 119–126. 10.1101/lm.033332.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus D, Yang Q, Kong D, Banks AS, Zhang L, Rodgers JT, et al. (2014). Nicotinamide N-methyltransferase knockdown protects against diet-induced obesity. Nature, 508, 258–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung LH, Gong KR, Adedoyin M, Ng J, Bhargava A, Ohara PT, et al. (2013). Evidence for glutamate as a neuroglial transmitter within sensory ganglia. PLoS One, 8(7), e68312 [doi:ARTN e68312]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson NG, Wang J, Wilhelmsson H, Oldfors A, Rustin P, Lewandoski M, et al. (1998). Mitochondrial transcription factor A is necessary for mtDNA maintenance and embryogenesis in mice. Nature Genetics, 18(3), 231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman JJ, Boudina S, Banke NH, Sambandam N, Han X, Young DM, et al. (2008). The transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha is essential for maximal and efficient cardiac mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and lipid homeostasis. American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 295(1), H185–H196. 10.1152/ajpheart.00081.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinninger GM, Edwards JL, Lipshaw MJ, & Feldman EL (2006). Mechanisms of disease: Mitochondria as new therapeutic targets in diabetic neuropathy. Nature Clinical Practice. Neurology, 2(11), 620–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone TC, Lehman JJ, Finck BN, Schaeffer PJ, Wende AR, Boudina S, et al. (2005). PGC-1alpha deficiency causes multi-system energy metabolic derangements: Muscle dysfunction, abnormal weight control and hepatic steatosis. PLoS Biology, 3(4), e101 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis EJH, Perkins BA, Lovblom LE, Bazinet RP, Wolever TMS, & Bril V (2017). Effect of omega-3 supplementation on neuropathy in type 1 diabetes: A 12-month pilot trial. Neurology, 88(24), 2294–2301. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Handschin C, & Spiegelman BM (2005). Metabolic control through the PGC-1 family of transcription coactivators. Cell Metabolism, 1(6), 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Wu PH, Tarr PT, Lindenberg KS, St-Pierre J, Zhang CY, et al. (2004). Defects in adaptive energy metabolism with CNS-linked hyperactivity in PGC-1alpha null mice. Cell, 119(1), 121–135. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locker J, & Rabinowitz M (1979). An overview of mitochondrial nucleic acids and biogenesis. Methods in Enzymology, 56(3–16), 3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]