Abstract

Background: Family planning (FP) providers are in an optimal position to address harmful partner behaviors, yet face several barriers. We assessed the effectiveness of an interactive app to facilitate implementation of patient–provider discussions about intimate partner violence (IPV), reproductive coercion (RC), a wallet-sized educational card, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Materials and Methods: We randomized participants (English-speaking females, ages 16–29 years) from four FP clinics to two arms: Trauma-Informed Personalized Scripts (TIPS)-Plus and TIPS-Basic. We developed an app that prompted (1) tailored provider scripts (TIPS-Plus and TIPS-Basic) and (2) psychoeducational messages for patients (TIPS-Plus only). Patients completed pre- and postvisit surveys. We compared mean summary scores of IPV, RC, card, and STI discussions between TIPS-Plus and TIPS-Basic using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, explored predictors with ordinal regression, and compared implementation with historical data using chi-square.

Results: Of the 240 participants, 47.5% reported lifetime IPV, 12.5% recent IPV, and 7.1% recent RC. No statistically significant differences emerged from summary scores between arms for any outcomes. Several significant predictors were associated with higher scores for patient–provider discussions, including race, reason for visit, contraceptive method, and condom nonuse. Implementation of IPV, RC, and STI discussions increased significantly (p < 0.0001) when compared with historical clinical data for both TIPS-Basic and TIPS-Plus.

Conclusions: We did not find an added benefit of patient activation messages in increasing frequency of sensitive discussions. Several patient characteristics appear to influence providers' likelihood of conversations about harmful partner behaviors. Compared with prior data, this pilot study suggests potential benefits of using provider scripts to guide discussions.

Keywords: IPV, reproductive coercion, implementation, primary care, family planning

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) and reproductive coercion (RC) are controlling behaviors perpetrated by a current or former partner, and are particularly prevalent among women seeking care at family planning (FP) clinics.1–3 IPV and RC have significant long-term and intergenerational health consequences, and as such, health care professionals have an important role in supporting survivors and preventing victimization.3

Both patient and provider barriers limit effective implementation of clinic-based interventions that promote universal education and assessment of IPV/RC. Across several studies,4–20 providers have noted similar barriers: insufficient time, lack of training, inadequate resources, personal discomfort, and uncertainty about how to handle patients' disclosures of IPV/RC. Among patients, reasons for not discussing IPV/RC with their health care provider include fear of retaliation by an abusive partner, stigma, previous poor encounters with the health care system, concerns about privacy and confidentiality, and uncertainty about whether a health care provider would be able to help.4–20

Researchers noted the influence of these barriers on intervention delivery during the implementation of a research-informed, evidence-based practice, Addressing Reproductive Coercion in Health Care Settings (ARCHES),21 centered on universal education, harm reduction, and warm referrals. While effective in increasing women's knowledge of resources and self-efficacy to enact harm reduction behaviors and reducing RC among women experiencing higher levels of RC at baseline, ARCHES was not consistently implemented, with significant variation across intervention sites.22 Implementation studies testing different strategies to improve integration of IPV/RC education and assessment into routine clinical practice are needed. The present intervention, Trauma-Informed Personalized Scripts (TIPS), was developed as a follow-up to ARCHES to address implementation challenges and explore the role of technology in IPV/RC assessment. Previous research has shown that technology-based interventions can help overcome barriers by improving confidentiality and privacy for patients, increasing provider efficiency, allowing for more adaptability, and appealing to younger age groups.6,23–30

As an extension of the main ARCHES study,21,22 all clinic staff at the participating FP clinics in the TIPS intervention were previously trained on the health impact of IPV/RC, as well as how to conduct IPV/RC universal education and assessment, distribute wallet-sized educational safety cards (https://www.futureswithoutviolence.org/is-your-relationship-affecting-your-health-safety-card/), and provide warm referrals to connect patients with local domestic violence advocates. Through a participatory and iterative process, we developed an interactive and user-friendly app31 with two main components: (1) printed provider scripts about fear, safety, harm reduction strategies, and universal education; and (2) patient psychoeducational messages, developed based on evidence from positive reward-related neuroscience.32 Both provider scripts and patient activation messages were tailored to patients' pregnancy intentions, contraceptive use, and IPV/RC exposure.

In the pilot TIPS study, we assess whether there are differences in patient-reported discussions of IPV/RC during clinical encounters comparing tailored messaging for both patients and providers (TIPS-Plus) to scripts for providers only (TIPS-Basic). We hypothesize that the patient activation component in TIPS-Plus will improve implementation when compared with TIPS-Basic by addressing both patient and provider barriers. In addition, we explore whether particular patient characteristics are associated with discussions about harmful partner behaviors during the clinical encounter. We also compare TIPS data with historical ARCHES data from the same clinics to examine whether adding a tablet-based app improves implementation of ARCHES, beyond what was achieved with standard training.

Materials and Methods

Four FP clinics in Western Pennsylvania, previously trained to implement ARCHES,33 participated in the study. These clinics serve a diverse patient population of primarily low-income reproductive age women, seeking care for contraception, general preventive health for women, and sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening and treatment. In the ARCHES randomized controlled trial (RCT), implementation of the intervention varied across clinics: 37%–91% of patients reported a discussion about IPV/RC during their clinic visit and 62%–94% received an educational safety card.22 The TIPS clinics were control sites during the ARCHES RCT (meaning they were providing usual care). As such, during the ARCHES RCT, no patients in the TIPS clinics received the educational safety card, but 59%–71% of participants (in TIPS clinics) did report that their providers discussed IPV or RC with them during a clinic visit.

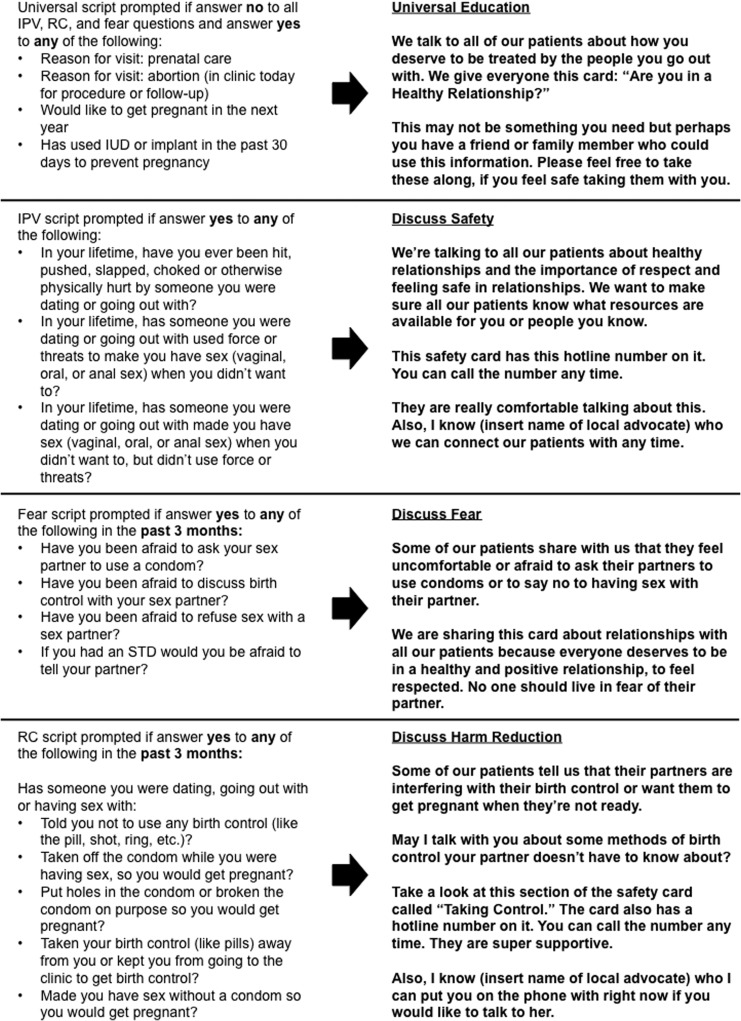

We used a RCT design to test how an interactive app impacted the frequency of provider–patient communication about harmful partner behaviors. After patients enrolled in the study, all participants (TIPS-Plus and TIPS-Basic) completed two separate surveys in the waiting room or a quiet location before seeing a provider for their visit: (1) a baseline survey using REDCap34 on demographics, sexual history, self-efficacy, and decisional conflict; and (2) a survey on the tablet-based app31 on pregnancy status, reason for visit, and lifetime and recent exposure to IPV/RC. The app randomized individual participants (before taking the survey) to TIPS-Plus (patient messages and provider scripts) or TIPS-Basic (provider scripts only), then presented questions about the patient's sexual/reproductive health and experiences with IPV and RC; her responses triggered a series of specialized scripts. These scripts would prompt the provider to discuss specific topics, such as fear, safety, harm reduction strategies, and universal education about IPV/RC (Fig. 1), without necessitating disclosure during the visit; only the scripts, not the patient's specific responses, were shown to the provider. Patients assigned to TIPS-Plus also received psychoeducational feedback on healthy/unhealthy relationships while answering questions on the tablet-based app. The messages were embedded into the app and tailored to their responses. We developed the scripts and activation messages through think-aloud sessions, semistructured interviews, and focus groups with providers, clinic staff, and patients. All participants completed an exit survey after their visit with the provider. Each survey took ∼5 minutes to complete.

FIG. 1.

If participating patients responded “yes” to the questions in the left column of the figure when using the tablet-based app, the corresponding script in the right column would be printed for their provider to use to help facilitate a tailored conversation about IPV and RC during the visit.

Eligible participants were as follows: female, 16–29 years old, English-speaking, and visiting one of the participating FP clinics. Participating patients had to complete their baseline survey before seeing a provider. We recruited patients from May 2016 to February 2017 and used two recruitment methods: (1) research assistants directly recruited patients at each clinic and (2) clinic receptionists provided study information to individuals through a telephone scheduling service before an upcoming visit.35 Patients received a US$25 gift card at baseline for their time. All FP providers were included in the ARCHES training (physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, and medical assistants).

For the primary outcome of any discussion with the provider, we created a summary score that captured any discussion of IPV, RC, and a wallet-sized safety card during the clinic visit. In addition, we measured summary scores for each discussion separately: IPV (3 items, score range = 0–3), RC (6 items, score range = 0–6), a wallet-sized safety card (4 items, score range = 0–4), and among those diagnosed with an STI, STI partner notification (2 items, score range = 0–2). We also examined recent (past 3 months) or lifetime disclosure of IPV or RC (Table 1). Patient participants self-reported all outcomes in the exit survey.

Table 1.

Primary Outcomes Related to Intervention Delivery During Clinic Visit

| Outcome | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| IPV-related discussion | Three items measured if providers engaged in discussions of IPV during clinic visits | “Today, did your health care provider talk with you about how violence or abuse in a relationship can impact a person's health?” |

| RC-related discussion | Six items measured if providers assessed patients for reproductive coercion and provided them with harm reduction strategies (regardless of whether patient experiencing RC) during clinic visit | “Today, did your health care provider ask you if your partner was messing or tampering with your birth control?” |

| Safety card-related discussion | Four items measured if clinicians reviewed and provided patients with safety card during clinic visits, as well as gauged participant understanding of the card and likelihood of sharing the safety card with others | “Today, did your health care provider talk to you about how to help a friend who is in an unhealthy relationship by giving this card?” |

| STI-related discussion | For participants who screened positive for an STI, two items assessed patient fear of partner notification and if the provider offered alternative forms of partner notification | “Did your health care provider ask you if you were afraid your partner might hurt you if you told them you have one?” |

| IPV/RC disclosure | One item measured if participant disclosed any IPV/RC (recent or lifetime) during their clinic visit | “Earlier when you took the tablet survey, you answered questions about being physically hurt, being made to have sex or being pressured to become pregnant. During your visit, did you share with your provider any experiences like these you may have had with someone you were dating or going out with?” |

IPV, intimate partner violence; RC, reproductive coercion; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

The final sample size of 240 was intended to provide 80% power to detect a standardized mean difference of 0.4 among longer term outcomes of interest at follow-up (e.g., confidence to use condoms with male partners). Here, we focus on the impact of the TIPS intervention on IPV/RC discussion during the baseline clinical encounter. We compared patient characteristics between the intervention and comparison arms using t-tests and chi-square (or Fisher's exact) tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. We used the Wilcoxon rank-sum tests to compare mean summary scores for participants in TIPS-Plus and TIPS-Basic. We also explored whether patient characteristics were associated with higher summary scores during their visits for each outcome, using ordinal logistic regression models beginning with simple models to assess bivariate (i.e., unadjusted) associations. Factors for which the test statistic for the bivariate association had a p < 0.2 were then tested for possible interactions with treatment arm; however, small cell sizes prevented most of these models from converging (results not shown). The bivariate model factors with p < 0.2 as well as the treatment group indicator were then included in multiple ordinal logistic regression models to get adjusted odds ratios (aORs). We reviewed similar items that were asked in both ARCHES (historical control) and TIPS, and used chi-square to compare results. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures. We obtained a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality.

Results

A total of 240 women participated in the baseline survey (58% participation). We recruited 87.3% of participants in clinic and 12.7% using the telephone scheduling service. Almost all participants (99.1%) completed postvisit exit surveys (Fig. 2). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Patients predominantly identified as white (70.8%) with a mean age of 22.4 years. The majority completed some college (40.4%) or a college degree (30.4%); 62.1% of the patients were in a serious relationship/dating one person. Lifetime IPV prevalence was 47.5%, with recent IPV and RC reported by 12.5% and 7.1% of patients, respectively. One in five participants had been fearful of their partner in the past 3 months. No statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics were found between treatment groups. Clinics differed statistically by patients' race, age, education level, and relationship status, but did not differ in lifetime or recent IPV or recent fear of a partner.

FIG. 2.

Flowchart demonstrating the randomization process in this pilot study. FP, family planning; PA, Pennsylvania.

Table 2.

Patient Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristic | Total (n = 240), % (n) | TIPS-Plus (n = 114), % (n) | TIPS-Basic (n = 126), % (n) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | ||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1.3 (3) | 1.8 (2) | 0.8 (1) | |

| Asian | 2.1 (5) | 2.6 (3) | 1.6 (2) | |

| Black/African American | 18.3 (44) | 17.5 (20) | 19.1 (24) | |

| Hispanic or Latina | 1.3 (3) | 0.9 (1) | 1.6 (2) | |

| White | 70.8 (170) | 71.9 (82) | 69.8 (88) | |

| Multiracial | 5.8 (14) | 5.3 (6) | 6.3 (8) | |

| Other | 0.4 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.8 (1) | |

| Fisher's exact p-value | 0.966 | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 22.4 (0.24) | 22.2 (0.32) | 22.6 (0.34) | |

| Two-sample t-test p-value | 0.427 | |||

| Education | ||||

| <12th grade | 9.6 (23) | 9.7 (11) | 9.5 (12) | |

| Finished high school | 19.6 (47) | 20.2 (23) | 19.1 (24) | |

| Some college | 40.4 (97) | 43.9 (50) | 37.3 (47) | |

| College degree or higher | 30.4 (73) | 26.3 (30) | 34.1 (43) | |

| Chi-square p-value | 0.598 | |||

| Relationship status | ||||

| Single | 31.3 (75) | 29.0 (33) | 33.3 (42) | |

| Dating >1 person | 4.2 (10) | 3.5 (4) | 4.8 (6) | |

| Dating 1 person/in a serious relationship | 62.1 (149) | 64.9 (74) | 59.5 (75) | |

| Married | 1.3 (3) | 0.9 (1) | 1.6 (2) | |

| Married with other sex partners than husband | 0.8 (2) | 1.8 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 0.4 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.8 (1) | |

| Fisher's exact p-value | 0.616 | |||

| Lifetime IPV | 47.5 (114) | 47.4 (54) | 47.6 (60) | |

| Chi-square p-value | 0.969 | |||

| Past 3 months experiences | ||||

| Any recent IPV | 12.5 (30) | 13.2 (15) | 11.9 (15) | |

| Chi-square p-value | 0.769 | |||

| Any recent RC | 7.1 (17) | 5.3 (6) | 8.7 (11) | |

| Chi-square p-value | 0.296 | |||

| Any recent fear | 20.4 (49) | 16.7 (19) | 23.8 (30) | |

| Chi-square p-value | 0.170 | |||

SD, standard deviation; TIPS-Basic, providers received tailored scripts to discuss harmful partner behaviors with their patients; TIPS-Plus, providers received tailored scripts to discuss harmful partner behaviors with their patients + patients received psychoeducational messages.

TIPS-Basic versus TIPS-Plus

We observed no statistically significant differences in the mean summary scores for discussion-related outcomes (Table 3). The mean summary score for any discussions about harmful partner behavior was 2.37 in TIPS-Plus and 2.39 in TIPS-Basic (p = 0.635). On a scale of 0–3, the mean summary score for discussions about IPV was 1.86 in TIPS-Plus compared with 2.04 in TIPS-Basic (p = 0.222). For RC discussions, we noted relatively low mean scores overall (range = 0–6), with 2.72 in TIPS-Plus and 2.66 in TIPS-Basic (p = 0.771). For patient–provider discussions about the safety card (range = 0–4), participants in TIPS-Plus had a mean score of 2.66 compared with 2.72 in TIPS-Basic (p = 0.781). Finally, with regard to STI partner notification (range = 0–2), mean scores were 1.19 and 1.56 in TIPS-Plus and TIPS-Basic, respectively, among those who were diagnosed with an STI at that visit (p = 0.075). A total of 25% of participants in TIPS-Plus disclosed IPV or RC to their provider during their visit, compared with 20.2% in TIPS-Basic (p = 0.450).

Table 3.

Comparing After-Visit Patient Report of Provider Communication About Intimate Partner Violence, Reproductive Coercion, Safety Cards, and Sexually Transmitted Infections Between Trauma-Informed Personalized Scripts (TIPS)-Plus and TIPS-Basic

| Mean summary score (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome (summary score) | TIPS-Plus, n = 114 | TIPS-Basic, n = 126 | pa |

| Discussion of IPV, RC, and safety card (3 summary items)b | 2.37 (2.19–2.55) | 2.39 (2.21–2.57) | 0.6349 |

| IPV discussion (3 items) | 1.86 (1.63–2.08) | 2.04 (1.84–2.24) | 0.2224 |

| RC discussion (6 items) | 2.72 (2.36–3.09) | 2.66 (2.31–3.00) | 0.7706 |

| Safety card discussion (4 items) | 2.66 (2.36–2.95) | 2.72 (2.45–2.99) | 0.7805 |

| STI discussion (2 items)c | 1.19 (0.85–1.53) | 1.57 (1.26–1.88) | 0.0748 |

| IPV/RC disclosure | 25.0% (20/80) | 20.2% (19/94) | 0.4500d |

Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann–Whitney) test, unless otherwise indicated.

Any discussion: summary score of any IPV discussion, any RC discussion, and any safety card discussion.

Responses from patients who reported a sexually transmitted infection diagnosis at clinic visit (n = 42; 21 = TIPS-Plus and 21 = TIPS-Basic).

Disclosure rates, compared by chi-square.

TIPS, Trauma-Informed Personalized Scripts; CI, confidence interval

Predictors of patient–provider discussions on harmful partner behaviors

Using multivariate ordinal logistic regression, we found several significant predictors for higher scores on provider discussions about harmful partner behaviors (Tables 4 and 5). For any provider discussions and IPV-related discussions, specifically, individuals of “other” race (American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, Hispanic/Latina, multiracial, and other) had statistically higher odds (any: aOR = 3.46, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.05–11.37; IPV: aOR = 3.01, 95% CI = 1.32–8.02) of having a higher summary score than individuals who identified as white. Similarly, black patients had significantly higher odds (aOR = 7.32, 95% CI = 1.14–47.17) of having a higher summary score compared with white patients in reporting STI-related discussions with their providers. Other positive predictors for any discussions related to harmful partner behaviors include visiting the clinic for contraception other than condoms (aOR = 2.06, 95% CI = 1.13–3.75) and using withdrawal as a contraceptive method (aOR = 2.38, 95% CI = 1.20–4.73). Seeking care for contraception other than condoms (aOR = 1.84, 95% CI = 1.05–3.22) and using withdrawal for contraception (aOR = 1.87, 95% CI = 1.08–3.25) were positive predictors of RC-related discussions, in addition to condom nonuse (when condom use was desired) (aOR = 1.94, 95% CI = 1.04–3.62). For patient–provider discussions on RC, negative predictors included lower education level (high school or less; aOR = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.26–0.86), being single or dating more than one person (aOR = 0.42, 95% CI = 0.24–0.75), seeking care for an annual checkup (aOR = 0.40, 95% CI = 0.22–0.72), and using a short-acting reversible contraceptive method (aOR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.34–0.98). Condom nonuse when desired (i.e., Have you ever not used a condom when you wanted to?) was also associated with higher IPV discussion scores (aOR = 2.19, 95% CI = 1.13–4.25). The only significant predictor for higher safety card discussion score was use of withdrawal as a contraceptive method (aOR = 2.17, 95% CI = 1.23–3.83).

Table 4.

Ordinal Logistic Regression Results–Bivariate Comparisons of Patient Characteristics on Intimate Partner Violence, Reproductive Coercion, Safety Card, and Sexually Transmitted Infection Discussions

| Outcome effect size unadjusted OR (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | Any discussiona | IPV discussion | RC discussion | Safety card discussion | STI discussionb |

| Age,c years | |||||

| 16–19 | 0.71 (0.35–1.45) | 0.70 (0.37–1.34) | 0.78 (0.42–1.46) | 0.87 (0.46–1.63) | 0.90 (0.15–5.29) |

| 25–29 | 1.03 (0.52–2.05) | 1.15 (0.63–2.10) | 1.08 (0.61–1.93) | 1.05 (0.58–1.91) | 1.19 (0.31–4.63) |

| Raced | |||||

| Black | 2.41 (1.09–5.33) | 2.67 (1.36–5.28) | 2.24 (1.20–4.19) | 1.06 (0.59–1.93) | 7.02 (1.24–39.67) |

| Other racial groupe | 3.46 (1.14–10.49) | 4.06 (1.64–10.05) | 1.66 (0.80–3.48) | 1.68 (0.79–3.59) | 2.63 (0.53–13.20) |

| Born in the United States | 0.46 (0.10–2.20) | 0.21 (0.05–1.02) | 0.41 (0.12–1.40) | 0.94 (0.31–2.84) | 0.46 (0.04–5.14) |

| Educationf | |||||

| High school or less | 0.60 (0.34–1.05) | 0.79 (0.47–1.34) | 0.57 (0.34–0.95) | 0.87 (0.52–1.47) | 0.60 (0.17–2.11) |

| Relationship statusg | |||||

| Single/dating >1 person/other | 0.94 (0.55–1.62) | 1.09 (0.66–1.78) | 0.51 (0.32–0.83) | 1.01 (0.62–1.65) | 1.80 (0.54–5.98) |

| Sexual partnersh | |||||

| Mostly men | 1.38 (0.61–3.11) | 1.22 (0.62–2.40) | 1.16 (0.59–2.25) | 1.08 (0.53–2.20) | 0.91 (0.21–3.93) |

| Mostly women, only women, equally men and women | 1.20 (0.30–4.72) | 2.54 (0.65–9.92) | 1.11 (0.36–3.42) | 0.68 (0.22–2.11) | 0.37 (0.02–8.24) |

| Fearful of partner (in the last 3 months) | 1.04 (0.55–1.98) | 1.36 (0.75–2.44) | 1.21 (0.68–2.15) | 0.80 (0.45–1.42) | 1.08 (0.32–3.61) |

| Recent RC (in the last 3 months) | 0.59 (0.24–1.44) | 1.13 (0.45–2.87) | 1.25 (0.47–3.29) | 0.55 (0.23–1.30) | 0.95 (0.22–4.07) |

| Recent IPV (in the last 3 months) | 0.65 (0.31–1.37) | 0.57 (0.29–1.15) | 0.67 (0.32–1.36) | 1.39 (0.68–2.84) | 0.40 (0.10–1.61) |

| Any lifetime IPV | 0.85 (0.51–1.43) | 0.95 (0.59–1.52) | 0.92 (0.58–1.45) | 0.92 (0.57–1.47) | 1.46 (0.45–4.76) |

| Reason for clinic visit | |||||

| Birth control other than condoms | 1.63 (0.95–2.80) | 1.22 (0.74–2.01) | 1.61 (0.99–2.60) | 1.57 (0.96–2.57) | 1.90 (0.59–6.14) |

| Symptoms | 0.79 (0.31–2.06) | 1.45 (0.58–3.65) | 0.92 (0.38–2.22) | 0.56 (0.24–1.29) | 1.71 (0.28–10.50) |

| Annual checkup | 0.88 (0.51–1.52) | 1.11 (0.67–1.85) | 0.56 (0.35–0.91) | 1.05 (0.63–1.76) | 0.89 (0.26–3.04) |

| STI test or treatment | 0.99 (0.53–1.83) | 1.10 (0.63–1.90) | 1.39 (0.81–2.38) | 0.63 (0.37–1.09) | 1.00 (0.31–3.19) |

| Otheri | 0.88 (0.41–1.85) | 1.23 (0.60–2.55) | 1.05 (0.54–2.05) | 0.93 (0.46–1.85) | 1.19 (0.18–7.88) |

| Method of contraception | |||||

| Hidden methodk | 0.68 (0.36–1.28) | 0.74 (0.41–1.33) | 0.66 (0.37–1.17) | 0.97 (0.53–1.78) | 0.95 (0.22–4.07) |

| Long-acting reversible contraception | 1.41 (0.49–4.05) | 1.54 (0.62–3.82) | 1.19 (0.51–2.77) | 1.39 (0.57–3.42) | 1.71 (0.28–10.50) |

| Short-acting reversible contraception | 0.65 (0.38–1.10) | 0.64 (0.40–1.04) | 0.55 (0.35–0.87) | 0.86 (0.54–1.38) | 0.37 (0.10–1.39) |

| Condoms | 1.29 (0.75–2.23) | 1.03 (0.63–1.67) | 1.46 (0.91–2.35) | 1.36 (0.83–2.20) | 1.11 (0.34–3.61) |

| Withdrawal | 2.29 (1.20–4.35) | 1.53 (0.90–2.58) | 1.80 (1.09–2.96) | 1.85 (1.09–3.12) | 3.26 (0.84–12.65) |

| None | 0.68 (0.22–2.16) | 1.60 (0.46–5.53) | 1.33 (0.34–5.10) | 0.70 (0.24–2.00) | 1.19 (0.18–7.88) |

| Patient did not use a condom when she wanted to, at least once | 1.59 (0.81–3.08) | 2.03 (1.10–3.74) | 2.03 (1.15–3.58) | 1.18 (0.66–2.08) | 2.08 (0.61–7.09) |

| Condom use frequencyk | |||||

| Always | 1.11 (0.55–2.22) | 1.00 (0.53–1.86) | 0.82 (0.45–1.49) | 1.57 (0.82–3.00) | 0.57 (0.10–3.38) |

Summary score range: IPV = 0–3, RC = 0–6, wallet-sized safety card = 0–4, STI = 0–2.

Results in bold indicate statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Any discussion: summary score of any IPV discussion, any RC discussion, and any safety card discussion.

Responses from patients who reported a sexually transmitted infection diagnosis at clinic visit (n = 42).

Reference groups: 20–24 years.

Reference groups: White.

Includes American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, Hispanic/Latina, multiracial, and other.

Reference groups: Some college education or college degree.

Reference groups: Married or dating one person.

Reference groups: Only men.

Includes colposcopy/cryotherapy, abnormal pap test, HPV vaccine, pregnancy test, other.

Includes LARC, Depo-Provera injection, and emergency contraception.

Reference groups: Sometimes, rarely, never.

LARC, long-acting reversible contraception; OR, odds ratio; HPV, Human Papillomavirus.

Table 5.

Ordinal Logistic Regression Results–Multivariate Comparisons of Patient Characteristics on Intimate Partner Violence, Reproductive Coercion, Safety Card, and Sexually Transmitted Infection Discussions

| Outcome effect size aOR (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | Any discussiona | IPV discussion | RC discussion | Safety card discussion | STI discussionb |

| Racec | |||||

| Black | 2.15 (0.88–5.25) | 2.07 (0.97–4.44) | 1.93 (0.92–4.03) | — | 7.32 (1.14–47.17) |

| Other racial groupd | 3.46 (1.05–11.37) | 3.01 (1.32–8.02) | 2.31 (0.95–5.61) | — | 2.53 (0.31–20.59) |

| Born in the United States | — | 0.39 (0.07–2.04) | 0.93 (0.18–3.91) | — | — |

| Educatione | |||||

| High school or less | 0.62 (0.32–1.17) | — | 0.47 (0.26–0.86) | — | — |

| Relationship statusf | |||||

| Single/dating >1 person/other | — | — | 0.42 (0.24–0.75) | — | — |

| Recent RC (in the last 3 months) | — | — | 0.95 (0.29–3.07) | 0.71 (0.27–1.87) | — |

| Recent IPV (in the last 3 months) | — | 0.48 (0.22–1.03) | — | — | 0.97 (0.20–4.75) |

| Reason for clinic visit | |||||

| Birth control other than condoms | 2.06 (1.13–3.75) | — | 1.84 (1.05–3.22) | 1.24 (0.69–2.22) | |

| Symptoms | — | — | — | 0.59 (0.22–1.56) | — |

| Annual checkup | — | — | 0.40 (0.22–0.72) | — | — |

| STI test or treatment | — | — | — | 0.66 (0.35–1.23) | — |

| Method of contraception | |||||

| Hidden methodg | — | — | 0.68 (0.36–1.27) | — | — |

| Short-acting reversible contraception | 0.66 (0.36–1.22) | 0.87 (0.51–1.49) | 0.58 (0.34–0.98) | — | 0.38 (0.08–1.85) |

| Condoms | — | — | 1.49 (0.87–2.55) | — | — |

| Withdrawal | 2.38 (1.20–4.73) | 1.50 (0.85–2.65) | 1.87 (1.08–3.25) | 2.17 (1.23–3.83) | 3.93 (0.83–18.61) |

| Patient did not use a condom when she wanted to, at least once | 1.41 (0.70–2.87) | 2.19 (1.13–4.25) | 1.94 (1.04–3.62) | — | — |

| Condom use frequencyh | |||||

| Always | — | — | — | 1.72 (0.87–3.40) | — |

All models were adjusted for intervention group (TIPS-Plus: provider scripts and patient activation messages; TIPS-Basic: provider scripts only) and all other variables with values shown in the column.

Results in bold indicate statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Any discussion: summary score of any IPV discussion, any RC discussion, and any safety card discussion.

Responses from patients who reported a sexually transmitted infection diagnosis at clinic visit (n = 42).

Reference groups: White.

Includes American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, Hispanic/Latina, multiracial, and other.

Reference groups: Some college education or college degree.

Reference groups: Married or dating one person.

Includes long acting reversible contraception (LARC), Depo-Provera injection, and emergency contraception.

Reference groups: Sometimes, rarely, never.

aOR, adjusted odds ratio.

TIPS versus historical data (ARCHES)

Compared with historical data from participating clinics, we found significantly higher rates of implementation with TIPS (with both TIPS-Plus and TIPS-Basic, with no significant differences between arms) for discussions about IPV and RC. For IPV discussion (i.e., Did your health care provider talk with you about healthy and unhealthy relationships?), implementation increased from 48.1% to 78.8% (p < 0.0001). For RC discussion (i.e., Today, did your health care provider ask if your partner was messing or tampering with your birth control?), implementation increased from 9.8% to 63.4% (p < 0.0001). For STI discussion (i.e., Did your health care provider ask you if you were afraid your partner might hurt you if you told them you have one?), implementation increased from 14.6% to 78.6% (p < 0.0001). While we observed statistically significant improvements in STI discussions among TIPS-Basic participants, we did not note any significant improvement in providers discussing safe ways to notify a partner about an STI in TIPS-Plus (p = 0.684). We did not conduct any comparisons between safety card discussions, since the TIPS clinics were control sites during the ARCHES study, thus providers were not given cards to distribute.

Discussion

We sought to compare TIPS-Plus and TIPS-Basic to determine the effectiveness of patient activation messages in addition to provider scripts in reducing barriers that both providers and patients face in discussing harmful partner behaviors. We found no statistically significant differences between the mean summary scores in TIPS-Plus and TIPS-Basic. In addition, we observed no significant differences in IPV or RC disclosure between the two arms. The lack of significant findings points to the extraordinary barriers patients have to overcome to initiate a conversation about harmful partner behaviors, including fear of judgment by providers, fear of retribution by a partner, and societal stigma more generally.8–20 It may take longer and more frequent exposure to address the highly complex challenges that patients face. Given the magnitude and difficulty of some of these barriers, it is important to resolve addressable barriers, such as provider time and knowledge, through interventions such as TIPS. As such, our findings shed light on the importance of addressing provider barriers and the potential utility of this scripted guidance for providers.

We also sought to elucidate patient characteristics that predicted conversations about harmful partner behaviors. Minority race was a significant predictor for any discussions, as well as IPV and STI discussions more specifically. Individuals categorized in the “other” racial group (Hispanic/Latina, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, and other) had higher odds of reporting increased summary scores for any and IPV discussions; black individuals had higher odds of reporting increased summary scores for STI discussions. Prior clinical studies have demonstrated no significant differences in IPV prevalence by race, and as such, minority race is not a known risk factor for IPV.1,36,37 In contrast, there is substantial evidence in the literature pointing to racial disparities in RC; yet, in our sample, we do not find that race is a significant predictor for RC discussions.1,36–39 The mechanism behind this observed phenomenon is unclear, but these results highlight the importance of addressing racial disparities and implicit bias during provider training sessions. As for STI discussions, existing prevalence estimates show higher rates of STIs among certain racial and ethnic minorities, so it follows more logically that black race is a significant predictor in our sample.40 Yet, it should be emphasized that providers should ask all patients who are STI positive, regardless of race, whether they are afraid of notifying their partner of their STI status. While beyond the scope of this study, these results suggest the continued need for integrating ongoing provider training on implicit bias. Implicit bias has been recognized by women's health organizations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, as an important priority to address among clinicians, as it has been shown to adversely impact relationships with patients and health outcomes.41,42 Training on implicit bias should be conducted through the lens of Reproductive Justice, which speaks to the nuanced and intersectional experiences of historically oppressed people.43

Other notable predictors included reason for visit, method of contraception, and condom nonuse when condom use was desired. If patients reported their reason for visit as “birth control other than condoms,” they reported higher odds of any discussion as well as more RC discussion items. These results suggest that providers are able to better initiate discussions of RC or other harmful partner behaviors when the visit reason is explicitly tied to contraceptive needs of a patient. In contrast, we found that providers are less likely to discuss RC when patients are instead coming in for an annual checkup. This may be because of insufficient time and other medical concerns taking precedence. Surprisingly, short-acting methods were associated with lower odds of more RC discussion items being asked, which is concerning given that many of these methods are more easily manipulated by a partner as opposed to hidden methods, such as intrauterine devices or implants. Finally, use of the withdrawal method seemed to be a “red flag” for providers to discuss RC and safety cards, as did condom nonuse for IPV and RC. Our results possibly indicate that providers are particularly attuned to counseling when patients are using less effective methods and are more likely to have in-depth conversations about harmful partner behaviors. These findings shed some light on providers' decision-making practices and point to need for identifying strategies to improve consistent communication with all patients about IPV/RC.

Finally, we compared implementation rates in TIPS with historical data from participating clinics, which were control sites in the original ARCHES study.22 We noted significant differences in almost all items (i.e., IPV, RC, and STI discussions). This improvement may be because all providers received scripts, telling them exactly what to say, addressing a commonly reported barrier in providing IPV/RC care.8–20 In addition, we paid attention during the design of the intervention to minimize clinic flow interruptions by having the patients complete the tablet-based survey while waiting. This helped address the barrier of insufficient time. Finally, the design process of the app relied on active participation of clinic staff. This may have improved clinician buy-in, increasing motivation to implement the intervention.

The TIPS study had a number of important strengths. As an exploratory study, we attempted to address both patient and provider barriers using a novel tablet-based app to help facilitate conversations about harmful partner behaviors. In addition, we implemented provider scripts as part of a universal education approach, which was developed based on patient-centered literature, revealing that survivors of IPV want access to resources and information regardless of disclosure to their providers.8–20 Our ultimate goal was to shift the locus of control from provider to patient, so that she can decide who and when to tell, and in receiving the educational safety card and provider guidance, also has the knowledge to make an informed decision.21,22 Furthermore, our use of the app adds to the existing literature on the use of technology in addressing IPV and RC. We addressed documented limitations to some existing computerized interventions, which left patients desiring a personal connection with a provider that allowed for a more customized response.4 To help reconcile this concern, the TIPS study used an innovative approach that combined the benefits of technology (nonjudgmental, confidential, and efficient) with tailoring the providers' in-person response. Clinical implications include the following: (1) short provider scripts tailored to patient responses may be helpful to increase the frequency of provider assessments of IPV and RC; (2) provider trainings should emphasize the universal assessment of IPV and RC, being mindful to address any implicit or explicit biases; and (3) tablet-based apps can be a useful tool to create interactive and tailored survey experiences.

The results of our study should be interpreted given the following limitations. As an exploratory study, piloted with a small number of FP clinics, there was no true control. The sample size was relatively small, limiting generalizability to larger populations. While we acknowledge that our study sites have been involved in a prior intervention33 (and as control sites in the initial ARCHES study), we tried to account for this by randomizing participants at the individual level, as opposed to the clinic level. The time lag between being trained in ARCHES and TIPS at these clinics was 2 years33; as we did not track staff turnover, we do not know which providers received which interventions. Next steps would include a larger RCT comparing TIPS-Plus and TIPS-Basic with a true control. Another area for exploration includes strategies to embed this app into the electronic health record. Furthermore, it would be useful to better understand how these tools impact overall provider self-efficacy to discuss other sensitive subjects, such as substance use, and other behavioral health diagnoses more broadly.

Conclusions

The TIPS study highlights the complexity of overcoming patient barriers in addressing harmful partner behaviors, but is a promising step toward improving intervention implementation at the provider level. The results also shed light on how patient characteristics, particularly race, reason for clinic visit, method of contraception, and condom use behaviors, potentially impact provider decisions to assess for IPV, RC, safety, or STIs in more detail with some and not other patients. Furthermore, TIPS helps contribute to the larger evidence base on how to utilize apps to provide patients with personalized, tailored, health education messages.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Melanie Grafals, Zabi Mulwa, Ashley Antonio, and Sarah Morrow for their help with data collection. They gratefully acknowledge the staff of Planned Parenthood of Western Pennsylvania and Adagio Health, as well as Futures Without Violence for their invaluable support with this study. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institutes of Health, of Adagio Health, or of Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc. This work was supported by Grants R01HD064407 and K24HD075862 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. In addition, the research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Science of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number TL1TR001858. Clinical Trial Registration: NCT02782728.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Miller E, Decker M, McCauley H, et al. Pregnancy coercion, intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy. Contraception 2010;81:316–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miller E, McCauley HL, Tancredi DJ, et al. Recent reproductive coercion and unintended pregnancy among female family planning clients. Contraception 2014;89:122–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. Global and regional estimates of violence against women. Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85239/1/9789241564625_eng.pdf Accessed March2018 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chang J, Dado D, Schussler S, et al. In person versus computer screening for intimate partner violence among pregnant patients. Pat Educ Couns 2012;88:443–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hegarty K, Tarzia L, Murray E, et al. Protocol for a randomised controlled trial of a web-based healthy relationship tool and safety decision aid for women experiencing domestic violence (I-DECIDE). BMC Public Health 2015;15:736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Renker PR. Breaking the barriers: The promise of computer-assisted screening for intimate partner violence. J Midwifery Womens Health 2008;53:496–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gerber MR, Leiter KS, Hermann RC, et al. How and why community hospital clinicians document a positive screen for intimate partner violence: A cross-sectional study. BMC Family Practice 2005;6:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Colarossi L, Breitbart V, Betancourt G. Barriers to screening for intimate partner violence: A mixed-methods study of providers in family planning clinics. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2010;42:236–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Elliott L, Nerney M, Jones T, et al. Barriers to screening for domestic violence. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:112–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Erickson MJ, Hill TD, Siegel RM. Barriers to domestic violence screening in the pediatric setting. Pediatrics 2001;108:98–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Waalen J, Goodwin MM, Spitz AM, et al. Screening for intimate partner violence by health care providers. Barriers and interventions. Am J Prev Med 2000;19:230–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rodriguez MA, Quiroga SS, Bauer HM. Breaking the silence: Battered women's perspectives on medical care. Arch Fam Med 1996;5:153–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gerbert B, Johnston K, Caspers N, Bleecker T, Woods A, Rosenbaum A. Experiences of battered women in health care settings: A qualitative study. Women Health 1996;24:1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McCauley J, Yurk R, Jenckes MW, Ford DE. Inside “Pandora's Box”: Abused women's experiences with clinicians and health services. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13:549–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chang J, Decker MR, Moracco K, Martin S, Petersen R, Frasier P. What happens when health care providers ask about intimate partner violence? A description of consequences from the perspectives of female survivors. J Am Med Womens Assoc 2003;58:76–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hathaway JE, Willis G, Zimmer B. Listening to Survivors' Voices: Addressing partner abuse in the health care setting. Violence Against Women 2002;8:687–719 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chang J, Decker MR, Moracco K, Martin S, Petersen R, Frasier P. Asking about intimate partner violence: Advice from female survivors to health care providers. Pat Educ Couns 2005;59:141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Caralis PV, Musialowski R. Women's experiences with domestic violence and their attitudes and expectations regarding medical care of abuse victims. South Med J 1997;90:1075–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Friedman LS, Samet JH, Roberts MS, Hudlin M, Hans P. Inquiry about victimization experiences: A survey of patient preferences and physician practices. Arch Intern Med 1992;152:1186–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McNutt L-A, Carlson BE, Gagen D, Winterbauer N. Reproductive violence screening in primary care: Perspectives and experiences of patients and battered women. J Am Med Wom Assoc 1999;54:85–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tancredi DJ, Silverman JG, Decker MR, et al. Cluster randomized controlled trial protocol: Addressing reproductive coercion in health settings (ARCHES). BMC Womens Health 2015;15:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Miller E, Tancredi DJ, Decker MR, et al. A family planning clinic-based intervention to address reproductive coercion: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Contraception 2016;94:58–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Choo EK, Zlotnick C, Strong DR, et al. BSAFER: A Web-based intervention for drug use and intimate partner violence demonstrates feasibility and acceptability among women in the emergency department. Substance Abuse 2016;37:441–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fincher D, VanderEnde K, Colbert K, et al. Effect of face-to-face interview versus computer-assisted self-interview on disclosure of intimate partner violence among African American women in WIC clinics. J Interpers Violence 2015;30:818–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rhodes KV, Lauderdale DS, He T, et al. “Between me and the computer”: Increased detection of intimate partner violence using a computer questionnaire. Ann Emerg Med 2002;40:476–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rhodes KV, Drum M, Anliker E, et al. Lowering the threshold for discussions of domestic violence: A randomized controlled trial of computer screening. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1107–1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tideman RL, Pitts MK, Fairley CK. Client acceptability of the use of computers in a sexual health clinic. Int J STD AIDS 2006;17:121–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Trautman DE, McCarthy ML, Miller N, et al. Intimate partner violence and emergency department screening: Computerized screening versus usual care. Ann Emerg Med 2007;49:526–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brayboy LM, Sepolen A, Mezoian T, et al. Girl talk: A smartphone application to teach sexual health education to adolescent girls. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2017;30:23–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Carswell K, McCarthy O, Murray E, et al. Integrating psychological theory into the design of an online intervention for sexual health: The sexunzipped website. JMIR Res Protoc 2012;1:e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. 3C Institute, Where Research and Practice Come Together [Internet]. 3C Institute. Available at: www.3cisd.com Accessed June1, 2017

- 32. Forbes EE, May JC, Siegle GJ, et al. Reward-related decision-making in pediatric major depressive disorder: An fMRI study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2006;47:1031–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zachor H, Chang J, Zelazny S, Jones K, Miller E. Training reproductive health providers to talk about intimate partner violence and reproductive coercion: An exploratory study. Health Educ Res 2018;33:175–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Your Message. Every Phone. Every Time. TextMarks SMS marketing text messaging. Available at: www.textmarks.com Accessed June1, 2017

- 36. Sutherland MA, Fantasia HC, Fontenot H. Reproductive coercion and partner violence among college women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2015;44:218–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Holliday CN, McCauley HL, Silverman JG, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in women's experiences of reproductive coercion, intimate partner violence, and unintended pregnancy. J Womens Health 2017;26:828–835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Clark LE, Allen RH, Goyal V, Raker C, Gottlieb AS. Reproductive coercion and co-occurring intimate partner violence in obstetrics and gynecology patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;210:42 .e1–42.e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rosenfeld EA, Miller E, Zhao X, Sileanu FE, Mor MK, Borrero S. Male partner reproductive coercion among women veterans. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;218:239 .e1–239.e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. 2017 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance: STDs in Racial and Ethnic Minorities. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/minorities.htm Accessed November11, 2018

- 41. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No 699: Adolescent pregnancy, contraception, and sexual activity. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:e142–e149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG statement of policy on racial bias. Available at: www.acog.org/-/media/Statements-of-Policy/Public/StatementofPolicy93RacialBias2017-2.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20190114T2054175845 Accessed January14, 2019

- 43. Dehlendorf C, Reed R, Fox E, Seidman D, Hall C, Steinauer J. Ensuring our research reflects our values: The role of family planning research in advancing reproductive autonomy. Contraception 2018;98:4–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]