Abstract

We describe a sexual network consisting of 1 nonbinary-gendered participant and 2 male and 4 female participants in Australia, 2018. Six of 7 participants had oropharyngeal gonorrhea in the absence of urogenital gonorrhea. This observation supports a new paradigm of gonorrhea transmission in which oropharyngeal gonorrhea can be transmitted through tongue kissing.

Keywords: gonorrhea, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, disease transmission, transmission, infectious, pharynx, Australia, sex network, oropharyngeal gonorrhea, urogenital gonorrhea, STIs, sexually transmitted infections, kissing, bacteria, whole-genome sequencing

Oropharyngeal gonorrhea is considered to be acquired primarily from an infected penis during oral sex (1). However, male urethral gonorrhea is usually symptomatic (2–4), prompting men to seek treatment soon after symptoms appear (5), resulting in short duration of infectivity and low point prevalence. Thus, infected penises are unlikely to be the source to explain the observed high prevalence of oropharyngeal gonorrhea (6,7). To address this epidemiologic conundrum, we previously described a paradigm of gonorrhea transmission in which oropharyngeal gonorrhea can be acquired from a partner’s oropharynx during tongue kissing (8), as originally proposed in the 1970s and 1980s (9,10). However, investigating whether kissing can lead to gonorrhea transmission has been difficult because kissing often occurs concurrently with other sexual acts (11). We describe a sexual network of 1 nonbinary, 2 male, and 4 female participants who were tested for gonorrhea at genital and oropharyngeal sites in early 2018 to explore gonorrhea transmission dynamics.

The Study

Ethics approval was obtained from the Alfred Hospital Ethics Committee, Melbourne, Australia (project no. 462/18). The index case was identified during routine patient care at Melbourne Sexual Health Centre (Carlton, Victoria, Australia). After patients consented to take part in our study, they contacted their sexual partners, who then each consented and were interviewed. Participants independently provided accounts of their sexual activity to permit interparticipant verification. We describe the timing of events with respect to day 0, the day of a music festival during which most sexual activity occurred.

We tested for Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection by nucleic acid amplification with the Aptima Combo 2 assay and confirmed by the Aptima GC assay (Gen-Probe, https://www.hologic.com). We performed whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatic analyses on available samples (Appendix).

Recalled accounts of sexual activity were consistent between participants. No participant reported symptoms of gonorrhea, and none used antimicrobial drugs during the relevant period.

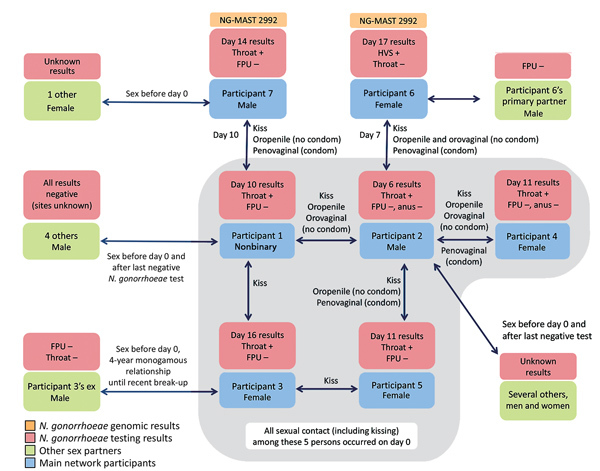

On day 10, the index patient (participant 1 [P1], nonbinary gender, assigned female sex at birth) sought screening for sexually transmitted infections at Melbourne Sexual Health Centre. Though asymptomatic, P1 tested positive for oropharyngeal gonorrhea and negative for urogenital gonorrhea. P1’s most recent negative test for gonorrhea was 5 months prior. Between the previous negative test and day 0, P1 had sex with 4 men besides their primary male sexual partner (P2) (Figure). These 4 other male sexual partners subsequently tested negative for gonorrhea; however, we were not able to confirm what anatomic sites were tested. On day 0, P1 had tongue kissed P3 (female) and had tongue kissed and had reciprocal orogenital sex (without condoms) and penovaginal sex (without condoms) with P2.

Figure.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae diagnoses among participants of a sexual network, Australia, 2018. FPU, first-pass urine; HVS, high vaginal swab; NG-MAST, N. gonorrhoeae multiantigen sequence type.

On day 16, P3 tested positive for oropharyngeal gonorrhea and negative for urogenital gonorrhea. She had not been tested for gonorrhea in the past 4 years because, until a recent break-up, she had been in a long-term monogamous relationship. She had no other sexual contacts (including kissing) with other men or women during this time. P3’s expartner was later contacted and tested and was negative for oropharyngeal and urogenital gonorrhea.

On day 6, before P1 underwent testing, P2 sought routine asymptomatic screening for sexually transmitted infections at Melbourne Sexual Health Centre and tested positive for oropharyngeal gonorrhea and negative for urogenital and anal gonorrhea. P2’s most recent test was 4 months earlier, when he tested negative for oropharyngeal, anal, and urogenital gonorrhea. P2 had sex with several men and women besides his primary partner between his last test and day 0; test results are not known for many of these sex partners.

On day 0, P2 had sex with P4 (female), consisting of tongue kissing, reciprocal orogenital sex without condoms, and penovaginal sex with condoms. On day 11, P4 tested positive for oropharyngeal gonorrhea and negative for urogenital and anal gonorrhea. Eleven days before day 0, P4 had tested negative for oropharyngeal and urogenital gonorrhea. P2 and P4 had had sex weekly for 5 months before day 0.

On day 0, P2 also had sex with P5 (female), consisting of tongue kissing, oropenile sex without condoms, and penovaginal sex with condoms. On day 11, P5 tested positive for oropharyngeal and negative for urogenital gonorrhea. P5’s previous gonorrhea test (negative results) was 1–2 years earlier. P5 also tongue kissed P3 but had no other sexual contact with her. P5 had no other sexual contacts, including tongue kissing, the 3 months before day 0.

On day 7, P2 had sex with P6 (female), consisting of tongue kissing, reciprocal orogenital sex without condoms, and penovaginal sex with condoms. On day 17, P6 tested positive for urogenital gonorrhea but negative for oropharyngeal gonorrhea. P6 had tested negative for urogenital gonorrhea ≈3 weeks before her contact with P2. The only other person (male) P6 had sex with during the time between her negative and positive test results subsequently tested negative for urogenital gonorrhea.

On day 10, P1 had sex with P7 (male), consisting of penovaginal sex with condoms, tongue kissing, and oropenile sex without condoms. P1 and P7 had sex weekly for 2 months before day 0. On day 14, P7 tested positive for oropharyngeal and negative for urogenital gonorrhea. His previous test was 4 years prior. P7 had 1 other sexual partner (female) in the months before day 0, and she was unable to be contacted.

Two N. gonorrhoeae isolates (from P6 and P7) were available for whole-genome sequencing. Both were N. gonorrhoeae multiantigen sequence type 2992, and no single-nucleotide polymorphism differences were found between the isolates (BioProject no. PRJNA449254).

This report describes a sexual network consisting of 1 nonbinary participant and 2 male and 4 female participants, of which 6 participants had oropharyngeal gonorrhea in the absence of urogenital gonorrhea. Although it is possible that some of the oropharyngeal infections were caused by undisclosed sexual contacts or inaccurate testing information, an additional explanation is that gonorrhea was transmitted by tongue kissing.

Two gonorrhea samples were available for genomic analysis and were highly related genomically. These participants were separated in this network by 2 other participants, corroborating the epidemiologic observation that these infections were the result of within-network transmission rather than a result of sexual contact with persons external to the network. Also, given the low prevalence of gonorrhea among the general population in Melbourne (https://kirby.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/kirby/report/SERP_Annual-Surveillance-Report-2017_compressed.pdf), the probability that all participants acquired gonorrhea from external partners is low.

No men in this network had urethral gonorrhea, suggesting that the oropharynx-to-penis route has a lower transmission probability than tongue kissing. This finding is consistent with an existing mathematical model that included transmission by kissing, which calculated a per-act transmission of 1% for oral sex and 17% for kissing (12). Few observational studies have examined transmission by kissing, but 1 study of male couples found 26% concordance of oropharyngeal gonorrhea between partners (13).

Because this report describes sexual contacts that occurred at a music festival, participants’ recall might have been affected by alcohol or drugs. Also, awareness of being part of a study involving sexual partners could have affected participants’ willingness to disclose information. However, recall was consistent between participants, suggesting that their recall was accurate.

Conclusions

Accumulating evidence suggests that tongue kissing might be a common mode of gonorrhea transmission (12–14). The observation that expectorated saliva from persons with oropharyngeal gonorrhea contains high loads of N. gonorrhoeae DNA suggests a plausible mechanism for transmission (15). The sexual network described here adds to this evidence. We also highlight the need for routine screening for oropharyngeal gonorrhea for all persons with multiple sexual partners.

Supplementary methods to investigate oropharyngeal gonorrhea in the absence of urogenital gonorrhea in a sexual network of male and female participants, Australia, 2018.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the extraordinary generosity of the participants included in this report for giving permission and taking the time to share this sensitive information.

V.J.C. was supported by a scholarship from the Research Training Scheme of the Australian Government’s Department of Education and Training. E.P.F.C. and D.A.W. are supported by Early Career Fellowships from the Australian National Health (no. 1091226) and Medical Research Council (no. 1123854).

Biography

Dr. Cornelisse is a sexual health physician at Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Carlton, Victoria, Australia. His main research interests are the epidemiology and prevention of gonorrhea and HIV prevention.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Cornelisse VJ, Bradshaw CS, Chow EPF, Williamson DA, Fairley CK. Oropharyngeal gonorrhea in absence of urogenital gonorrhea in sexual network of male and female participants, Australia, 2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019 Jul [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2507.181561

References

- 1.Wiesner PJ, Tronca E, Bonin P, Pedersen AH, Holmes KK. Clinical spectrum of pharyngeal gonococcal infection. N Engl J Med. 1973;288:181–5. 10.1056/NEJM197301252880404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison WO, Hooper RR, Wiesner PJ, Campbell AF, Karney WW, Reynolds GH, et al. A trial of minocycline given after exposure to prevent gonorrhea. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1074–8. 10.1056/NEJM197905103001903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ong JJ, Fethers K, Howden BP, Fairley CK, Chow EPF, Williamson DA, et al. Asymptomatic and symptomatic urethral gonorrhoea in men who have sex with men attending a sexual health service. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23:555–9. 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryder N, Lockart IG, Bourne C. Is screening asymptomatic men who have sex with men for urethral gonorrhoea worthwhile? Sex Health. 2010;7:90–1. 10.1071/SH09100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fairley CK, Chow EP, Hocking JS. Early presentation of symptomatic individuals is critical in controlling sexually transmissible infections. Sex Health. 2015;12:181–2. 10.1071/SH15036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornelisse VJ, Chow EP, Huffam S, Fairley CK, Bissessor M, De Petra V, et al. Increased detection of pharyngeal and rectal gonorrhea in men who have sex with men after transition from culture to nucleic acid amplification testing. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44:114–7. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbee LA, Dombrowski JC, Kerani R, Golden MR. Effect of nucleic acid amplification testing on detection of extragenital gonorrhea and chlamydial infections in men who have sex with men sexually transmitted disease clinic patients. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41:168–72. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fairley CK, Hocking JS, Zhang L, Chow EP. Frequent transmission of gonorrhea in men who have sex with men. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:102–4. 10.3201/eid2301.161205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutt DM, Judson FN. Epidemiology and treatment of oropharyngeal gonorrhea. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:655–8. 10.7326/0003-4819-104-5-655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willmott FE. Transfer of gonococcal pharyngitis by kissing? Br J Vener Dis. 1974;50:317–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornelisse VJ, Walker S, Phillips T, Hocking JS, Bradshaw CS, Lewis DA, et al. Risk factors for oropharyngeal gonorrhoea in men who have sex with men: an age-matched case-control study. Sex Transm Infect. 2018;94:359–64. 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang L, Regan DG, Chow EPF, Gambhir M, Cornelisse V, Grulich A, et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae transmission among men who have sex with men: an anatomical site-specific mathematical model evaluating the potential preventive impact of mouthwash. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44:586–92. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornelisse VJ, Williamson D, Zhang L, Chen MY, Bradshaw C, Hocking JS, et al. Evidence for a new paradigm of gonorrhoea transmission: cross-sectional analysis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections by anatomical site in both partners in 60 male couples. Sex Transm Infect. 2019;sextrans-2018-053803. 10.1136/sextrans-2018-053803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cornelisse VJ, Zhang L, Law M, Chen MY, Bradshaw CS, Bellhouse C, et al. Concordance of gonorrhoea of the rectum, pharynx and urethra in same-sex male partnerships attending a sexual health service in Melbourne, Australia. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:95. 10.1186/s12879-018-3003-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chow EP, Tabrizi SN, Phillips S, Lee D, Bradshaw CS, Chen MY, et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae bacterial DNA load in the pharynges and saliva of men who have sex with men. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:2485–90. 10.1128/JCM.01186-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary methods to investigate oropharyngeal gonorrhea in the absence of urogenital gonorrhea in a sexual network of male and female participants, Australia, 2018.