Abstract

The coordinated generation and propagation of action potentials within cardiomyocytes creates the intrinsic electrical stimuli that are responsible for maintaining the electromechanical pump function of the human heart. The synchronous opening and closing of cardiac Na+, Ca2+, and K+ channels corresponds with the activation and inactivation of inward depolarizing (Na+ and Ca2+) and outward repolarizing (K+) currents that underlie the various phases of the cardiac action potential (resting, depolarization, plateau, and repolarization). Inherited mutations in pore-forming α subunits and accessory β subunits of cardiac K+ channels can perturb the atrial and ventricular action potential and cause various cardiac arrhythmia syndromes, including long QT syndrome, short QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome, and familial atrial fibrillation. In this Review, we summarize the current understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms that underlie K+-channel-mediated arrhythmia syndromes. We also describe translational advances that have led to the emerging role of genetic testing and genotype-specific therapy in the diagnosis and clinical management of individuals who harbor pathogenic mutations in genes that encode α or β subunits of cardiac K+ channels.

Introduction

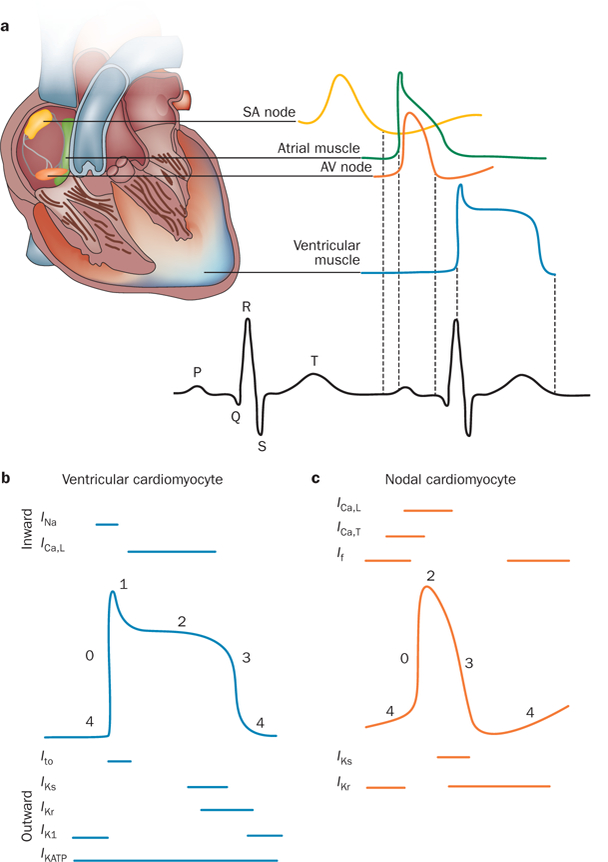

The ability of the heart to pump blood efficiently throughout the body is dependent on the coordination of nodal, atrial, and ventricular cardiomyocytes. In healthy individuals, the cardiac cycle is initiated by the spontaneous depolarization of specialized ‘pacemaker’ cells in the sinoatrial node located within the right atrium. Electrical coupling via intercellular gap junctions allows the rapid conduction of depolarizing electrical impulses to nearby atrial cardiomyocytes, which triggers the excitation and subsequent contraction of the atria that is reflected by the P-wave on the surface electrocardiogram (ECG). The electrical impulse is then conducted from the atria to the atrioventricular node where, after a brief delay, it propagates through the Purkinje fibers to the apex of the heart and then into the cardiomyocytes of the right and left ventricles. The excitation of ventricular cardiomyocytes results in the contraction of the ventricles and is represented by the QRS complex on the surface ECG (Figure 1a).

Figure 1 |.

Normal electrical activity of the heart. a | Schematic representation of the cardiac conduction system and the correlation between the action potentials of cardiomyocytes in distinct regions of the heart and the surface electrocardiogram. b | Temporal relationship between the inward and outward currents that contribute to the distinct phases (0–4) of the ventricular cardiomyocyte action potential. c | Temporal relationship between the inward and outward currents that contribute to the distinct phases (0–4) of the nodal cardiomyocyte action potential (which lacks a defined phase 1). Abbreviations: AV, atrioventricular; ICa,L, inward depolarizing Ca2+ current (through L-type Ca2+ channels); ICa,T, inward depolarizing Ca2+ current (through T-type Ca2+ channels); If, inward-rectifier mixed Na+ and K+ ‘funny’ current; IK1, inward-rectifier K+ current; IKATP, ATP-sensitive K+ current; IKr, rapid component of the delayed-rectifier K+ current; IKs, slow component of the delayed-rectifier K+ current; INa, inward depolarizing Na+ current; Ito, transient outward K+ current; SA, sinoatrial.

At the cellular level, the electrical impulses that drive the cardiac cycle are dependent on the generation of action potentials within individual cardiomyocytes via the sequential opening and closing of ion channels that conduct the depolarizing inward (Na+ and Ca2+) and repolarizing outward (K+) currents (Figure 1b,c).1 The transient outward current (Ito), delayed outward-rectifying currents (IKs, IKr, and IKur ), and inward-rectifying currents (IK1, IKAch, and IKATP) are conducted by cardiac K+ channels and are responsible for the rapid repolarization (phase 1 and phase 3) that is needed to restore and maintain the cardiomyocyte resting membrane potential (phase 4; Figure 1b). These K+ currents are critical for the timely restitution of the cardiac action potential and coordinated contraction of the atria and ventricles. In the 1990s, two teams independently made the seminal discovery that loss-of-function mutations in the K+-channel α subunits KvLQT1 or Kv7.1 (encoded by KCNQ1) and hERG1 or Kv11.1 (encoded by KCNH2) serve as the primary genetic substrates for congenital long QT syndrome (LQTS).2,3 Since then, loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutations that cause LQTS and a spectrum of related heritable cardiac channelopathies, including Brugada syndrome, short QT syndrome (SQTS), and familial atrial fibrillation (AF), have been identified in various K+-channel α subunits and ancillary proteins.4–7

Gain-of-function mutations that result in enhanced K+-channel function are expected to shorten the cardiac action-potential duration (APD) and provide a substrate for re-entrant arrhythmias in disorders such as Brugada syndrome and SQTS. Loss-of-function mutations that excessively impair K+-channel function prolong the cardiac APD and confer increased susceptibility to early afterdepolarizations that can trigger episodes of torsades de pointes in patients with LQTS.8 Over the past decade, the pathophysiological mechanisms and numerous genotype–phenotype correlations associated with K+ channelopathies have been elucidated and have provided the crucial insights needed to begin development of gene-specific and mutation-specific approaches to the risk stratification and clinical management of individuals with these potentially fatal, yet highly treatable, genetic disorders.9,10 In this Review, we describe the molecular and cellular mechanisms that underlie inherited arrhythmia syndromes associated with mutations in pore-forming α subunits and accessory β subunits of K+ channels. We also discuss the now-established role of genetic testing and genotype-specific therapy in the diagnosis and clinical management of individuals with inherited K+-channel-mediated arrhythmia syndromes.

Cardiac K+ channels

Structure and classification

With over 80 distinct genes that encode the principle subunits of K+-selective ion channels, K+ channels represent the largest and most-functionally diverse family of ion-channel proteins in the human genome.11–13 The genes that encode the α and β subunits of K+ channels that conduct the major K+ currents of the cardiac action potential are summarized (Table 1), and the structure of K+ channels is described in detail (Supplementary Box 1). Despite distinct differences in molecular structure, all α subunits of the K+ channels share several common features. Firstly, a highly conserved pore-forming region that makes the efflux of K+ ions following an electrochemical gradient and across the plasma membrane possible; secondly, a characteristic structural motif within the pore-forming region that establishes the channel’s selectivity filter to allow permeation of only K+ ions; thirdly, a mechanism of gating that controls the transition of the channel from an open to a closed conformation in response to membrane depolarization or ligand binding; and fourthly, one or more subunit-assembly domains that allow individual monomeric α subunits to assemble in a specific fashion into functional dimers or tetramers.13–16

Table 1 |.

Genes encoding important α and β subunits of K+ channels

| Current | Chromosomal location | Gene | Protein | Type of subunit | Disease | OMIM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ito,f | 1p13.2 | KCND3 | Kv4.3 | α | BrS9* | 605411 |

| 10q24.32 | KCNIP2 | KChIP2 | β | None | 604661 | |

| 11q13.4 | KCNE3 | MiRP2 | β | BrS5 | 604433 | |

| Ito,s | 11p14.1 | KCNA4 | Kv1.4 | α | None | 176266 |

| IKs | 11p15.5-p15.4 | KCNQ1 | Kv7.1/KvLQT1 | α | LQT1, SQT2, FAF | 607542 |

| 21q22.12 | KCNE1 | mink | β | LQT5 | 176261 | |

| 7q21.2 | AKAP9 | AKAP-9 | β | LQT11 | 611820 | |

| IKr | 7q36.1 | KCNH2 | Kv11.1/hERG | α | LQT2, SQT1, FAF | 152427 |

| 21q22.11 | KCNE2 | MiRP1 | β | None | 603796 | |

| IK1 | 17q24.3 | KCNJ2 | Kir2.1/IRK1 | α | LQT7, SQT3, FAF | 600681 |

| 17p11.2 | KCNJ12 | Kir2.2/IRK2 | α | None | 602323 | |

| IKATP | 12p12.1 | KCNJ8 | Kir6.1 | α | BrS8*/ERS | 600935 |

| 11p15.1 | KCNJ11 | Kir6.2 | α | None | 600937 | |

| 12p12.1 | ABCC9 | SUR2A/SUR2B‡ | β | FAF | 601439 | |

| IKur | 12p13.32 | KCNA5 | Kv1.5 | α | FAF | 176267 |

| N/A | KCNAB1-B3 | Kvβ1–3 | β | None | N/A | |

| IKAch | 2q24.1 | KCNJ3 | Kir3.1/GIRK1 | α | None | 601534 |

| 11q24.3 | KCNJ5 | Kir3.4/GIRK4 | α | LQT13 | 600734 | |

| If | 15q24.1 | HCN4 | HCN4 | α | Sinus bradycardia | 605206 |

Brugada-syndrome-associated mutations in KCNJ8 and KCND3 are more appropriately termed KCNJ8-BrS and KCND3-BrS. ‡SUR2A and SUR2B are splice-variants of ABCC9, classically considered as the cardiac (SUR2A) and vascular (SUR2B) isoforms. Abbreviations: BrS, Brugada syndrome; ERS, early repolarization syndrome; FAF, familial atrial fibrillation; If, inward-rectifier mixed Na+ and K+ ‘funny’ current; IK1, inward-rectifier K+ current; IKAch, acetylcholine-activated inward-rectifier K+ current; IKATP, ATP-sensitive K+ current; IKr, rapid component of the delayed-rectifier K+ current; IKs, slow component of the delayed-rectifier K+ current; IKur, ultra-rapid component of the delayed-rectifier K+ current; Ito,f, fast component of the transient outward K+ current; Ito,s, slow component of transient outward K+ current; Kir, inwardly rectifying K+ channel; Kv, voltage-gated K+ channel; LQT, long QT syndrome; OMIM, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man database reference number; SQT, short QT syndrome.

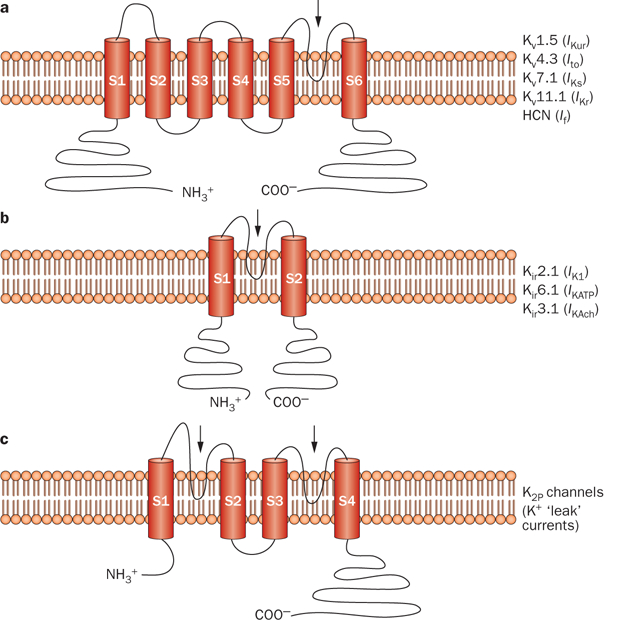

In general, α subunits of cardiac K+ channels can be classified into three broad classes on the basis of the primary amino-acid sequence of the pore-forming α subunit: the voltage-gated (Kv) and calcium-activated (KCa) channels possess six or seven transmembrane regions and one pore-forming region (Figure 2a), inward-rectifying K+ channels (Kir) have two transmembrane and one pore-forming region (Figure 2b), and members of the two-pore-domain K+ channel (K2P) subfamilies have four transmembrane and two pore-forming regions (Figure 2c).12,13,16 To recapitulate the biophysical properties of native K+ currents, the α subunits of the Kv and Kir channels generally interact with accessory β subunits and other regulatory intracellular and transmembrane proteins that cover a diverse molecular and functional spectrum.16,17

Figure 2 |.

Predicted protein topology of cardiac K+-channel α subunits. Schematic representations of a | the six-transmembrane one-pore-region voltage-dependent K+-channel (Kv) α subunits that conduct IKur, Ito, IKs, IKr, and If in the heart, b | the two-transmembrane one-pore-region inward-rectifying K+-channel (Kir) α subunits that conduct IK1, IKATP, and IKAch in the heart, and c | the four-transmembrane two-pore-region K+ channel (K2P) responsible for ‘leak’ K+ currents. The arrows indicate the location of the pore-forming region(s). Abbreviations: HCN, hyperpolarization-activated cyclic-nucleotide-gated channel; If, inward-rectifier mixed Na+ and K+ ‘funny’ current; IK1, inward-rectifier K+ current; IKAch, acetylcholine-activated inward-rectifier K+ current; IKATP, ATP-sensitive K+ current; IKr, rapid component of the delayed-rectifier K+ current; IKs, slow component of the delayed-rectifier K+ current; IKur, ultra-rapid component of the delayed-rectifier K+ current; Ito, transient outward K+ current.

Contribution to the action potential and ECG

In cardiomyocytes within the atria, Purkinje fibers, and ventricles, excitation by electrical impulses from adjacent cardiomyocytes activates SCN5A-encoded NaV 1.5 voltage-gated Na+ channels and, therefore, gives rise to phase 0 depolarization (indicated by a rapid upstroke; Figure 1b). The influx of Na+ rapidly shifts the membrane potential from a negative resting membrane potential (approximately –80 mV or –85 mV for atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes, respectively) into the positive range. The voltage-dependent inactivation of INa, coupled with the activation of KCND3-encoded Kv4.3 voltage-gated K+ channels that conduct Ito, results in phase 1 repolarization that determines the height and duration of the phase 2 plateau. The plateau phase represents a delicate balance between the influx of Ca2+ through CACNA1C-encoded Cav1.2 channels, which conduct the depolarizing L-type Ca2+ current (ICa,L), and the efflux of K+. This efflux occurs through voltage-gated KCNA5-encoded Kv1.5 channels (predominantly in cardiomyocytes within the human atria), KCNH2-encoded Kv11.1 channels, and KCNQ1-encoded Kv7.1 channels, which conduct the ultra-rapidly (IKur), rapidly (IKr), and slowly (IKs) activating components of the delayed outward-rectifying currents, respectively. Because Cav1.2 channels inactivate during phase 3 (repolarization), the repolarizing delayed outward-rectifying currents are mainly responsible for returning the membrane potential back to the negative resting potential. Finally, the diastolic resting membrane potential during phase 4 (resting phase; Figure 1b) is maintained by the conductance of K+ ions through nonvoltage-gated, KCNJ2-encoded Kir2.1 channels.

At the molecular level, the regional and spatial heterogeneity observed in atrial, nodal, and ventricular cardiomyocyte action-potential morphology (Figure 1a), APD, and effective refractory period are attributed to profound variation in the expression of ion channels within each region of the heart.1 Compared with ventricular cardiomyocytes, atrial cardiomyocytes exhibit action potentials with a markedly shorter and lower amplitude because of a shift in the balance of inward Ca2+ currents and outward K+ currents during phase 2. This feature is the result of the greater amplitude of Ito in phase 1 and the additional contribution of IKur to phase 3.18,19 Substantial differences in Ito density between the ventricular epicardium and the endocardium account for ventricular transmural action potential heterogeneity.20 Compared with the ventricular endocardium, where the amplitude of Ito is fairly low, the presence of a prominent Ito in the ventricular epicardium results in a shorter duration and more pronounced ‘notch’ in action potentials during phase 1.21

As a result of sparse or absent IK1,22 cardiomyocytes in the sinoatrial node fail to reach ‘true’ resting potentials in phase 4 (Figure 1c), a feature that contributes to their characteristic ability to generate spontaneous and repetitive action potentials. The lack of IK1, together with the activation of highly expressed, hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic-nucleotide-gated channels that conduct the inward-rectifying mixed Na+ and K+ ‘funny’ current (If) as membrane potentials dip below –40 mV to –45 mV during phase 3, results in the initiation of diastolic depolarization at the end of phase 4.23 As a functional consequence, Nav1.5 channels that are present in the sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes are believed to be functionally inactivated and thus not to contribute to the phase 0 upstroke. Phase 0 depolarization in the nodal cardiomyocytes, therefore, heavily relies on the activation of L-type and T-type Ca2+ channels that conduct ICa,L and ICa,T, respectively (Figure 1c).24 In addition, some nodal cardiomyocytes lack the fast component of Ito (Ito,f), which might partially explain why nodal cardiomyocytes (Figure 1c) lack the ‘spike-and-dome’ action-potential morphology of atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes (Figure 1b).23

Cardiac K+ channelopathies

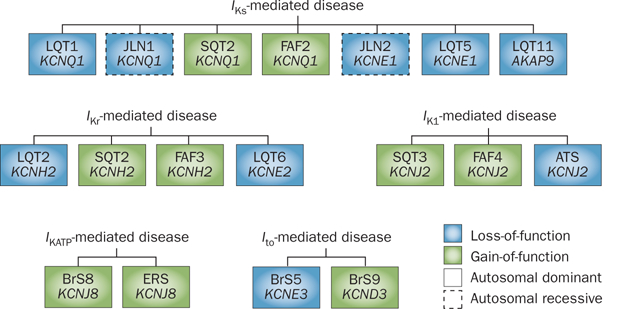

The term ‘channelopathy’ refers to any disease that arises from defects in ion-channel function.25 As such, the inherited arrhythmia syndromes discussed in this Review can be considered K+ channelopathies because each is caused by defects in cardiac K+-channel function (Figure 3). Collectively, cardiac channelopathies affect at least 1 in 1,000 individuals and shared cardinal events include syncope mediated by ventricular arrhythmias, seizures, and sudden cardiac death. The variable expressivity and incomplete disease penetrance that are hallmarks of all cardiac channelopathies are reflected in the clinical course of these disorders, which assumes a spectrum ranging from sudden death during infancy to a lifelong asymptomatic state.

Figure 3 |.

Classification of cardiac K+ channelopathies stemming from mutations in α or β subunits on the basis of currents and channels. Current-centric depiction of the K+ channelopathies arising from loss-of-function (blue boxes) or gain-of-function (green boxes) mutations that perturb IKs, IKr, IK1, IKATP, or Ito. Abbreviations: BrS, Brugada syndrome; ERS, early repolarization syndrome; FAF, familial atrial fibrillation; I, inward-rectifier K+ current; I, ATP-sensitive K+ current; I, rapid component of the delayed-rectifier K+ current; IKs, slow component of the delayed-rectifier K+ current; Ito, transient outward K+ current; JLN, Jervell and Lange–Nielsen syndrome; LQT, long QT syndrome; SQT, short QT syndrome. Permission obtained from Wolters Kluwer Health © Priori et al. Inherited arrhythmogenic disease: the complexity beyond monogenic disorders. Circ. Res. 94(2), 140–145 (2004).

LQTS

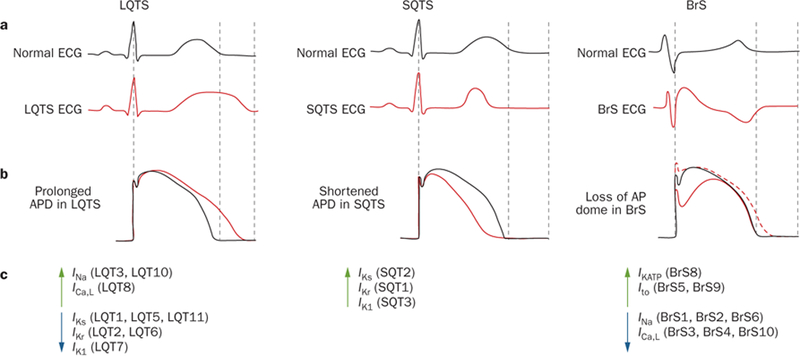

In LQTS, the enhancement of inward depolarizing currents (INa and ICa) or the reduction of outward repolarizing currents (IKr, IKs, and IK1) results in the prolongation of cardiac action potentials that manifests as QT prolongation on the surface ECG (Figure 4).26 These phenomena are associated with an increase in cardiomyocyte refractoriness and enhancement of the Na+,Ca2+-exchange current, which leads to abnormal reactivation of the L-type Ca2+-channel during phase 2 and phase 3, and triggers early afterdepolarizations and torsades de pointes.27

Figure 4 |.

Pathophysiological mechanisms of K+-channel-mediated arrhythmias at the ionic and cellular level. a | Schematic representation of a normal ECG (black) and typical ECGs for patients with LQTS (left, red), SQTS (middle, red), and BrS (right, red), illustrating QT lengthening, QT shortening, and coved ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads V1–V3 and presence of a J-wave, respectively. b | Tracings of normal ventricular action potentials (black) and tracings that display epicardial action-potential prolongation in LQTS (left, red), action-potential abbreviation in SQTS (middle, red), and the transmural gradient between the epicardial action potential (right, solid red line) and endocardial action-potential (right, dotted red line) that results in the inscription of the J-wave in BrS. c | Perturbations in ion currents that contribute to the pathogenesis of LQTS, SQTS, and BrS. Green upwards arrows indicate gain-of-function mutations, whereas blue downwards arrows represent loss-of-function mutations. Abbreviations: AP, action potential; APD, action-potential duration; BrS, Brugada syndrome; ECG, electrocardiogram; LQT or LQTS, long QT syndrome; SQT or SQTS, short QT syndrome. Reproduced from Wilde, A. A. & Bezzina, C. R. Genetics of cardiac arrhythmias. Heart 91(10), 1352–1358 © 2005, with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Genetic basis of congenital LQTS

Congenital LQTS is an uncommon, genetically heterogeneous disorder of myocardial repolarization associated with an increased risk of syncope, seizures, and sudden death secondary to torsades de pointes—the characteristic form of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation in patients with LQTS (Supplementary Figure 1).28 The autosomal-dominant form of congenital LQTS, previously known as Romano–Ward syndrome, is caused by a mutation in any one of at least 13 distinct LQTS-susceptibility genes, has an estimated prevalence of 1:2,000, and is associated with an annual event rate of 0.3–0.6% depending on the genotype.29 By contrast, the very rare autosomal-recessive form of congenital LQTS (known as Jervell and Lange–Nielsen syndrome) stems from mutations in KCNQ1 (LQTS type 1, or LQT1) or KCNE1 (LQT5) and is associated with a more malignant cardiac phenotype with a higher event rate than autosomal-dominant LQTS, as well as concomitant bilateral sensorineural deafness.30

Genetic basis of adult LQTS

Loss-of-function mutations in the KCNQ1-encoded Kv7.1 channel cause LQT1, the most-common genetic subtype of LQTS, which is responsible for 30–35% of all LQTS cases.31,32 Because the assembly of Kv7.1 with the KCNE1-encoded β subunit K+ voltage-gated channel subfamily E member 1 (also known as minK) is required to recapitulate IKs fully,33,34 loss-of-function mutations in KCNE1 (LQT5) also prolong the QT interval.

Over 300 LQT1-susceptibility mutations have been identified to date. The functional investigation of merely a fraction of these has already unearthed an array of biogenic and biophysical mechanisms that underlie IKs loss-of-function. These mechanisms include defective protein trafficking,35 impaired subunit tetra-merization,36 kinetic alterations (that affect voltage sensing, channel gating, K+ selectivity, or K+ permeation), and disruption of interactions between Kv7.1 and key regulatory proteins or molecules (such as the kinase-anchoring protein AKAP-937 and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate38). Notably, these mechanisms are not mutually exclusive. A single KCNQ1 mutation can confer more than one functional effect on the Kv7.1 channel, as illustrated by mutations such as Kv7.1-His258Arg58 and Kv7.1-Ser277Leu.39,40

Interestingly, IKs is enhanced by β-adrenergic stimulation via AKAP-mediated and minK-mediated phosphorylation of the Kv7.1 α subunit by protein kinase A and protein kinase C, respectively.41 Furthermore, Chen and colleagues described a mutation in the KCNQ1-binding domain of AKAP-9 (LQT11) that reduces the cAMP-mediated phosphorylation of Kv7.1, thereby blunting the response of IKs to increased levels of cAMP-associated β-adrenergic stimulation.42 These data suggest that the contribution of IKs to cardiac repolarization is particularly important in the presence of β-adrenergic stimulation. Consistent with this molecular signaling, LQT1-related cardiac events typically occur in settings associated with increased adrenergic tone, such as emotional stress or exercise (particularly swimming), which is likely to be because of an inadequate compensatory response by mutant IKs to β-adrenergic stimulation.43 LQT1 genotype–phenotype correlations also include the presence of broad-based, prolonged T-waves on the ECG44 and paradoxical QT prolongation during a QT stress test with epinephrine or during the recovery phase after an exercise stress-test on a treadmill or bicycle.45–50

LQT2 is caused by loss-of-function mutations in the KCNH2-encoded human-ether-a-go-go-related gene K+-channel 1 (hERG1 or Kv11.1) and is responsible for an estimated 25–30% of all LQTS cases.31,32 The assembly of four full-length hERG1a α subunits—or a combination of hERG1a and the shorter, alternatively spliced hERG1b isoform—form the tetrameric Kv11.1 channel that conducts IKr.51,52 This current is differentiated from other K+ currents that mediate cardiac repolarization by its disproportionately rapid rate of inactivation compared with its activation, and by the unique structural features of the inner mouth of its channel pore that leave the channel prone to blockade by an array of drugs, leading to acquired, drug-induced LQTS.53 The interaction of Kv11.1 with the KCNE2-encoded MiRP1 β subunit is thought to be required to recapitulate the kinetic and pharmacological properties of native IKr,54 and rare LQTS-associated mutations in KCNE2 (LQT6) decrease currents through Kv11.1 channels when co-expressed in heterologous expression systems.55–57 However, the physiological importance of the hERG1–MiRP1 interaction and the functional consequences of KCNE2 loss-of-function mutations in vivo have been disputed.58–60

The functional characterization of a small percentage of known KCNH2 mutations has elucidated multiple mechanisms responsible for IKr loss-of-function in LQT2, including nonsense-mediated decay, defective Kv11.1 protein synthesis, impaired Kv11.1 protein trafficking, and kinetic alterations in channel gating and K+ selectivity or K+ permeation.61 Defective Kv11.1 protein trafficking—which encompasses defective protein folding, retention in the endoplasmic reticulum, and disrupted trafficking to the Golgi apparatus or to the cell surface—represents the dominant molecular mechanism in LQT2 and is thought to underlie the functional consequences of an estimated 80–90% of KCNH2 missense mutations.61,62 Interestingly, the function of many trafficking-deficient Kv11.1 channels can be rescued by high-affinity hERG-blocking drugs, such as fexofenodine63 or aminoglycoside antibiotics,64 and by lowering the incubation temperature of cells in culture.65 The hERG secretory pathway and pharmacological rescue of hERG mutants deficient in protein trafficking have been reviewed elsewhere.66

Compared with individuals with LQT1, patients with LQT2 experience more cardiac events as a result of auditory stimuli, such as the ringing of a telephone or alarm clock.67 Women with LQT2 have a greater torsadogenic potential during the postpartum period than at other times.68,69 Other clinically relevant LQT2 genotype– phenotype correlations include the presence of low-amplitude T-waves and notched T-waves on the ECG (Supplementary Figure 1).44,68

Andersen–Tawil syndrome (ATS), another K+-channel mediated subtype of LQTS, is a rare, multisystem disorder characterized by the clinical triad of dysmorphic features, periodic paralysis, and nonsustained ventricular arrhythmia.4 Loss-of-function mutations in the KCNJ2-encoded Kir2.1 channel (and thus IK1) are responsible for 50–60% of ATS cases (also known as LQT7). ATS1 is differentiated from the classical forms of LQTS (LQT1, LQT2, and Na+-channel-mediated LQT3) by a mild QT-interval prolongation, marked prolongation of the QU interval, and the presence of broad, high-amplitude U-waves on the ECG (Supplementary Figure 1).70 Although the arrhythmia burden of patients with ATS is often quite high owing to well-tolerated rhythm abnormalities such as slow ventricular tachycardia, degeneration to lethal ventricular arrhythmias triggered by early afterdepolarizations is less common in patients with ATS than in patients with more-common forms of LQTS.70

Diagnosis

The primary diagnostic characteristic of LQTS is a prolonged heart-rate-corrected QT interval (QTc) on a 12-lead ECG (Figure 4) in the absence of structural heart disease or secondary causes of a prolonged QT interval, such as electrolyte imbalances, hypothermia, and use of certain drugs.71 A prolonged QTc is defined in the 2009 joint guidelines of the AHA, ACC, and Heart Rhythm Society as >450 ms in men and >460 ms in women.72 However, the large overlap of QTc values between patients with LQTS and healthy individuals presents a substantial diagnostic challenge. Approximately 40–50% of genotype-positive patients with LQTS have a QTc <460 ms,73 whereas 5–10% of the general population have a QTc >460 ms on a screening ECG.74 Therefore, employing the 99.5th percentile of the QTc-value distribution (corresponding to >470 ms in men and >480 ms in women) might maximize the identification by ECG screening of those individuals who would benefit most from a comprehensive LQTS evaluation, while minimizing the number of false-positives (Figure 5). However, even at these thresholds, the positive predictive value for LQTS is still <10% in the absence of any corroborating evidence. Furthermore, manual calculation of the QTc from either lead II or lead V5 of the 12-lead ECG using a method such as Bazett’s formula75 is critical to verify the QTc measurement because computer-derived QTc values can be unreliable in patients with complex T-wave and U-wave arrangements.74,76

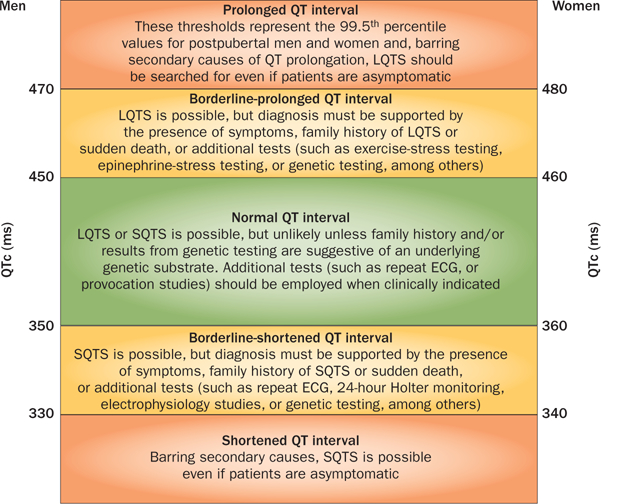

Figure 5 |.

The spectrum of QTc values and associated clinical indications for adults with a QTc value in the prolonged, borderline-prolonged, normal, borderline-short, and extremely short ranges. This Figure represents a modification of the algorithm initially proposed by G. M. Vincent140 and later modified by S. Viskin.141 Abbreviations: ECG, electrocardiogram; LQTS, long QT syndrome; QTc, heart-rate-corrected QT interval; SQTS, short QT syndrome. Reprinted from Viskin, S. The QT interval: too long, too short or just right. Heart Rhythm 6(5), 711–715 © 2009, with permission from the Heart Rhythm Society.

A definitive diagnosis of LQTS can be particularly challenging in individuals with borderline QT prolongation (defined as 450–470ms in men and 460–480ms in women; Figure 5) and should involve a thorough examination of the entire clinical picture. First introduced in 1985 and modified in 1993, the Schwartz score is a diagnostic scorecard that relies on ECG parameters and the clinical and family history to assess quantitatively the clinical probability of LQTS in a patient (Table 2).77 Although the positive predictive value of a composite score ≥3.5 is quite high, the Schwartz score is not useful to assess LQTS probability in first-degree and second-degree relatives because of the markedly variable disease expressivity and penetrance that is often observed in families with a history of LQTS. For the assessment of relatives of patients with known LQTS-causative mutations, the only definitive diagnostic test that is currently available is confirmatory genetic testing.78

Table 2 |.

Diagnostic criteria and score for LQTS

| Diagnostic criteria | LQTS points* |

|---|---|

| ECG findings‡ | |

| QTc interval ≥480 ms | 3 |

| QTc interval 460–479 ms | 2 |

| QTc interval 450–459 ms (in men) | 1 |

| Torsade de pointes§ | 2 |

| T-wave alternans | 1 |

| Bradycardia (<2nd percentile for age) | 1 |

| Clinical history | |

| Syncope without stress§ | 2 |

| Syncope with stress§ | 1 |

| Congenital deafness | 0.5 |

| Family history | |

| Family history of LQTS|| | 1 |

| Unexplained sudden death of a 1st-degree family member <30 years of age|| | 0.5 |

Total score indicates probability of LQTS: ≤1 point (low), 2–3 points (intermediate), ≥4 points (high).

QTc interval calculated with Bazett’s formula; results must be obtained in the absence of underlying disorders, drugs, or other modifiers known to influence the QTc interval.

Syncope and torsade de pointes are mutually exclusive.

The same family member cannot be counted twice. Abbreviations: LQTS, long QT syndrome; QTc, heart-rate-corrected QTc interval. Permission obtained from the AHA © Schwartz, P. J. et al. Diagnostic criteria for the long QT syndrome. An update. Circulation 88(2), 782–784 (1993).

Many genotype-positive patients with LQTS, particularly individuals with LQT1,79 display no or ‘borderline’ QT prolongation (450–470 ms in men and 460–480 ms in women); diagnostic tests to unmask potentially lethal genetic substrates in individuals with concealed LQTS are, therefore, needed. Under normal physiological circumstances, increased β-adrenergic tone as a result of exercise or administration of catecholamines enhances cardiac repolarization (mainly via effects on IKs), and thus accelerates repolarization. In patients with LQT1, the normal physiological response of Kv7.1 channels to β-adrenergic stimulation is blunted, resulting in ‘attenuated QTc shortening’ or ‘paradoxical QTc lengthening’ during exercise or after administration of low-dose epinephrine (≤0.1 μg/kg/min).44,49,50 In 2006, we reported that the presence of paradoxical QT prolongation during a challenge with escalating doses of epinephrine had a 92.5% sensitivity, 86% specificity, and 76% positive predictive value to detect individuals with LQT1.47 Because these tests primarily challenge the responsiveness of Kv7.1 channels (or of IKs) to β-adrenergic stimulation, the presence of a normal QT-interval shortening response during exercise or upon administration of epinephrine does not exclude other types of LQTS.80 Nonetheless, the use of a epinephrine-challenge protocol with bolus injections has been reported to improve the detection of LQT2 by enhancing the characteristic notched T-waves that are associated with perturbations of Kv11.1 channels or IKr.81

Risk stratification

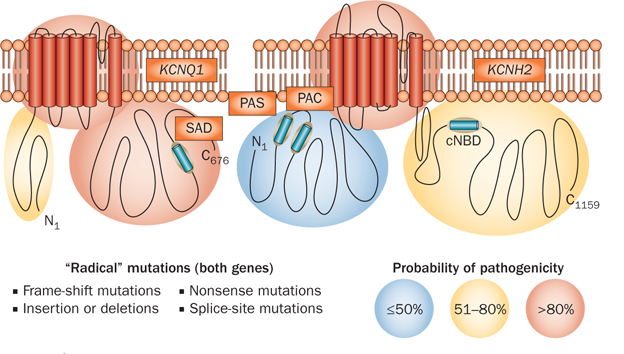

Given the marked genotypic and phenotypic heterogeneity that is associated with LQTS, the use of clinical and genetic predictors to determine which individuals are at the greatest risk of life-threatening events is crucial to the selection of appropriate and efficacious management strategies. Clinical predictors of increased risk of LQTS-triggered events include a QTc >500 ms, previous syncope mediated by torsades de pointes or aborted sudden death, boys in childhood, and women in adulthood.82 Independent of these clinical predictors, certain genetic predictors are associated with increased risk, including multiple disease-causative mutations, LQT1-causative mutations that are associated with a dominant-negative effect or located in the transmembrane domains (or both),83 LQT2-causative mutations in the Kv11.1 pore region,84 LQT2-causative mutations in α-helical domains,85 and mutations involving conserved amino-acid residues.86 The use of location-based algorithms that compare the relative incidence of mutations in patients with those in healthy individuals has demonstrated that the probability of pathogenicity associated with missense mutations is largely dependent on the location of the mutation within the Kv7.1 or Kv11.1 channel, whereas ‘radical mutations’ (such as nonsense mutations, splice-site mutations, insertions, and deletions) have a high probability of pathogenicity regardless of their location (Figure 6).87,88 The co-segregation of deleterious, common genetic variations (such as KCNH2-Lys897Thr,89 KCNE1-Asp85Asn,90 and various single-nucleotide polymorphisms in NOS1AP that modulate the QT interval in healthy individuals)91 that represent functional polymorphisms with a mild QT-lengthening and proarrhythmic influence can worsen the clinical course of LQTS.

Figure 6 |.

The probabilistic nature of LQTS genetic testing. Depicted is the probability of pathogenicity for mutations that localize to the N-terminal, transmembrane, or C-terminal regions of the Kv7.1 and Kv11.1 channels that collectively constitute the two major causes of congenital LQTS. Although radical mutations have a >90% probability of being pathogenic, the probability for missense mutations varies depending on the location within each respective K+ channel. Missense mutations in areas shaded in red carry a high probability (>80%), mutations in yellow have an intermediate probability (51–80%), and the pathogenicity of mutations in blue areas is uncertain (<50%). Abbreviations: cNDB, cyclic-nucleotide-binding domain; LQTS, long QT syndrome; PAC, PAS-associated C-terminal domain; PAS, Per–Arnt–Sim domain; SAD, subunit assembly domain. Permission obtained from Wolters Kluwer Health © Tester, D. J. & Ackerman, M. J. Genetic testing for potentially lethal, highly treatable inherited cardiomyopathies/channelopathies in clinical practice. Circulation 123(9), 1021–1037 (2011).

Patient management

Management of all symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with LQTS should include proper counseling on the avoidance of QT-prolonging medications71 and the maintenance of adequate hydration (and hence electrolyte levels) in the setting of emesis or diarrhea to avoid hypokalemia. Given that sudden death can be the first manifestation of all types of LQTS, all symptomatic patients and most asymptomatic patients aged <40 years require medical, surgical, or device-related therapy (or a combination thereof). Asymptomatic patients aged >40 years (regardless of their genotype) and asymptomatic men aged >20 years with LQT1 have the lowest risk, and an appropriate intervention (if any) should be selected on an individual basis.

Data derived from basic, translational, and clinical studies have made genotype-guided pharmacological and nonpharmacological therapies for the management of patients with genotype-positive LQTS possible. The mainstay of therapy in all patients with LQTS, but particularly those with LQT1, is β-blocker therapy (usually with nadolol and propranolol), which is protective and associated with a low risk of a breakthrough event while patients are on therapy.92 In terms of nonpharmacological intervention, unilateral left cardiac sympathetic denervation, which involves the surgical resection of the lower half of the left stellate ganglion and of the thoracic ganglia T2–T4, is more effective in patients with LQT1 than in patients with other forms of LQT,93 and should be considered in individuals with demonstrated intolerance to β-blocker therapy, arrhythmia storms, and recurrent shocks from implantable cardioverter–defibrillators (ICDs).94,95 Of the major types of LQTS, prophylactic ICD implantation should be utilized least frequently in patients with LQT1, although an ICD is indicated as secondary prevention in individuals who experience aborted cardiac arrest or suffer breakthrough cardiac events, such as syncope mediated by torsades de pointes on adequate β-blocker therapy. Because of the severe arrhythmia burden often associated with Jervell and Lange–Nielsen syndrome, the use of β-blockers plus either an ICD or left cardiac sympathetic denervation is indicated as first-line therapy.

For patients with LQT2, β-blocker therapy still constitutes first-line therapy, but is associated with a 20–30% chance of an LQT2-triggered breakthrough event.96,97 Additional treatment options include oral K+ supplementation or drugs that increase serum K+ levels (for example spironolactone).98 Indications for an ICD in patients with LQT2 are largely the same as for patients with LQT1, but also include high-risk patients such as previously symptomatic adult women with a QTc >500 ms.99,100 Because left cardiac sympathetic denervation might exert a substrate-independent antifibrillatory effect, this therapy is a viable option for patients with LQT2 who suffer from recurrent ICD shocks or other complications related to device implantation.

Given the rare nature of the other K+-channel mediated subtypes of LQTS (such as LQT5, LQT6, LQT7, and LQT11), no specific genotype-guided clinical recommendations for the management of patients with these subtypes currently exist. However, since LQT5 and LQT11 stem from mutations in auxiliary proteins that modify the function of Kv7.1 channels and IKs, patients with LQT5 and LQT11 should be treated in the same way as patients with LQT1.

SQTS

First described in 1999,101 SQTS is a heritable, primary electrical disorder of the heart. SQTS is characterized by an extremely short QT interval (usually QT ≤350 ms or QTc ≤330 ms in men, QT ≤360 ms or QTc ≤340 ms in women; Figure 5) on the ECG in an individual with an otherwise structurally normal heart, but an increased risk of AF, ventricular fibrillation, and sudden cardiac death.102,103 Although the overall prevalence of SQTS remains unknown, individuals with clinically defined SQTS seem to carry one of the highest overall yearly event rates among patients with heritable arrhythmia syndromes (3.3% overall and 4.9% in patients who do not receive pharmacotherapy).104

By contrast with LQTS, which arises from loss-of-function mutations in cardiac K+ channels, the three known genetic subtypes of K+-channel-mediated SQTS arise from gain-of-function mutations in KCNH2 (SQT1), KCNQ1 (SQT2), and KCNJ2 (SQT3).105–107 In general, acceleration of repolarization because of an enhancement of IKr, IKs, or IK1 abbreviates cardiac action potentials, which manifests electrocardiographically as a very short QT interval (Figure 4). Similar to the pathogenesis of K+-channel-mediated J-wave syndromes, preferential and heterogeneous abbreviation of the action potential in the epicardium or endocardium secondary to enhancement of outward repolarizing currents seems to give rise to a transmural dispersion of repolarization that serves as a substrate for the genesis of re-entrant arrhythmias.108

Genetic basis

Nearly 5 years after the seminal description of SQTS as a clinical entity, the first SQTS-susceptibility gene, KCNH2 (SQT1), was discovered by Brugada and colleagues using a candidate-gene-based approach.105 In this study, two distinct missense mutations that both led to the substitution of lysine for asparagine at residue 588 (KCNH2-Asn588Lys) in the S5 pore-forming region of the Kv11.1 channel were identified in two unrelated families with SQTS.105 Functional characterization using the standard whole-cell patch-clamp technique revealed that KCNH2-Asn588Lys mutant channels failed to rectify across a physiological range of potentials, and right-shifted the voltage-dependent inactivation, which resulted in a large net gain-of-function in IKr during the plateau phase of the cardiac action potential (Supplementary Table 1).105 Two additional SQT1-associated mutations, KCNH2-Thr618Ile and KCNH2-Arg1135His, have also been described.109,110 Although both mutations display functionally perturbed electrophysiological phenotypes (Supplementary Table 1), only KCNH2-Thr618Ile traced with disease in a multigenerational SQTS pedigree. KCNH2-Arg1135His is currently classified as an SQTS modifier, given that two additional KCNH2-Arg1135His carriers within the same small pedigree failed to display a QT interval within the SQTS diagnostic range.110

Shortly after the discovery of KCNH2 as the first SQTS-susceptibility gene, Bellocq and colleagues identified a mutation in KCNQ1 (SQT2) in a man aged 70 years who presented with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation and an abnormally short QT interval, using a candidate-gene-based approach.106 This mutation was predicted to result in the substitution of valine for leucine at residue 307 in the pore-forming region of the Kv7.1 channel. Heterologous expression of mutant KCNQ1-Val307Leu revealed a functionally perturbed electrophysiological phenotype (Supplementary Table 1) that imparts a pronounced gain-of-function to IKs.106 Another SQT2-associated mutation (KCNQ1-Val141Met), which abolished voltage-dependent gating in vitro (Supplementary Table 1), was subsequently identified in a baby girl aged 38 weeks with AF and SQTS in utero.111 Notably, although strong circumstantial evidence suggests a casual relationship between IKs gain-of-function mutations in KCNQ1 and SQTS, the discovery of KCNQ1-Val141Met and KCNQ1-Val307Leu in isolated, sporadic cases precludes proof of a definite casual relationship by demonstration that these mutations co-segregate with disease.

In 2005, Priori and colleagues discovered a novel mutation within a third SQTS-susceptibility gene, KCNJ2 (SQT3), in an asymptomatic girl aged 5 years and her father aged 35 years, who both displayed extremely short QT intervals.107 This mutation was predicted to result in the substitution of aspartic acid for asparagine at residue 172 (KCNJ2-Asp172Asn) in the S2 region of the Kir2.1 channel. Functional characterization of KCNJ2-Asp172Asn using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique demonstrated an increased outward IK1 at potentials between –75 mV and –45 mV.107

Diagnosis and risk stratification

As in patients with LQTS, the overlap of QTc values between patients with SQTS and healthy individuals limits the use of a short QT as the sole or primary diagnostic criterion because roughly 5% of healthy adult men and women would be expected to have a QTc that falls within the SQTS diagnostic range (<350 ms for men and <360 ms for women; Figure 5). Furthermore, the QT interval is typically independent of heart rate in patients with SQTS (for example, the QT–RR relationship shows a diminished rate-dependence.102,112 Thus, at rapid heart rates (>100 bpm), commonly used heart-rate-correction formulas (such as Bazett’s formula) tend to yield normal QTc values (350–450 ms for adult men and 360–460 ms for adult women; Figure 5), which results in a false-negative diagnosis. Therefore, when SQTS is suspected, measurement of the QT interval when the heart rate is at least <100 bpm (preferably close to 60 bpm) is imperative.102,103 In pediatric populations where a resting heart rate >100 bpm is physiologically normal, the use of 24 h Holter monitoring or long-term ECG monitoring can be required to obtain accurate QT-interval measurements.102,103 A diagnosis of SQTS also requires the elimination of secondary causes of a short QT interval, such as hypercalcemia, hyperkalemia, hyperthermia, metabolic or respiratory acidosis, and drugs known to shorten the QT interval (such as digitalis).102

As with other heritable cardiac channelopathies, rendering a definitive SQTS diagnosis in individuals with borderline short QT intervals (defined as 330–350 ms in men and 340–360 ms in women; Figure 5) can be particularly challenging and requires a careful examination of the entire clinical picture. A diagnostic scorecard for SQTS on the basis of the QT interval, and clinical and family history was proposed by Gollob and colleagues in 2011 (Table 3).7 Although the scorecard seems to have a high positive predictive value for detection of patients with a high probability of having SQTS (as the Schwartz score has for LQTS), it might be less sensitive for the diagnosis of relatives of patients with confirmed SQTS, because incomplete disease penetrance seems to be a common phenomenon across heritable arrhythmia syndromes.

Table 3 |.

Diagnostic criteria and score for SQTS

| Diagnostic criteria | SQTS points* |

|---|---|

| ECG findings‡ | |

| QTc interval 351–370 ms | 1 |

| QTc interval 331–350 ms | 2 |

| QTc interval <330 ms | 3 |

| J-point–T-peak interval <120 ms§ | 1 |

| Clinical history | |

| History of sudden cardiac arrest | 2 |

| Documented polymorphic VT or VF|| | 2 |

| Syncope|| | 1 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 |

| Family history | |

| Family history of SQTS¶ | 1 |

| Unexplained sudden death of a 1st-degree family member aged <30 years¶ | 1 |

| Sudden infant-death syndrome¶ | 1 |

| Genotype | |

| Genotype-positive | 2 |

| Variant of uncertain significance in a culprit gene | 1 |

Total score indicates probability of SQTS: ≤2 points (low), 3 points (intermediate), ≥4 points (high).

QTc interval calculated with Bazett’s formula; results must be obtained in the absence of underlying disorders, drugs, or other modifiers known to influence the QTc interval.

J-point–T-peak interval must be measured in the precordial lead with the greatest amplitude T-wave; a minimum of one point must be obtained in the electrocardiogram section in order to obtain additional points.

Syncope and VT or VF are mutually exclusive.

The same family member cannot be counted twice. Abbreviations: SQTS, short QT syndrome; QTc, heart-rate-corrected QTc interval; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia. Reprinted from Gollob, M. H. et al. The short QT syndrome: proposed diagnostic criteria. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 57(7), 802–812 © 2011, with permission from the ACC Foundation.

Given that fewer than 10 unrelated SQTS cases with specific mutations have been described, current data are insufficient to establish meaningful genotype–phenotype correlations for K+-channel-mediated SQTS. However, the T-wave morphology in SQT1 and SQT2 seems to be distinctly different from that of SQT3. Individuals with SQT1 or SQT2 tend to have characteristic tall, symmetric, peaked T-waves,105,106 whereas those with SQT3 feature narrow, asymmetric, peaked T-waves.107

Patient management

Given the high incidence of both sudden death and inducible ventricular arrhythmia during invasive electrophysio-logical studies in patients with SQTS,113 ICDs remain the therapy of choice.102 However, patients with SQTS might be at increased risk of inappropriate ICD shocks because of the tall T-wave morphology.114 In addition, adjunctive antiarrhythmic medications such as quinidine and disopyramide (class Ia agents) or nifekalant (a class III agent) have been shown to normalize the QT interval and T-wave morphology, and thereby decrease the transmural dispersion of repolarization and myocyte refractoriness in SQTS, which provides initial evidence that these drugs might reduce arrhythmia risk in these patients.115–117 Although the results of these studies are promising, larger studies are needed to evaluate fully the future role of these pharmacological agents in the management of SQTS.

J-wave syndromes

Collectively, the QRS–ST-segment junction, or J-point, and the domed deflection immediately following the QRS complex, or J-wave, signify the end of depolarization and start of repolarization on the surface ECG (Figure 1).118 After the seminal description of Brugada syndrome as a clinical entity in 1992,119 the presence of J-point elevation and ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads has served as an electrocardiographic marker for individuals at increased risk of sudden cardiac death.120,121 By contrast, an early repolarization pattern (characterized by the presence of J-point elevation and notching or slurring of the QRS complex that results in a J-wave in the inferolateral leads) is almost always a benign ECG variant that is typically detected in healthy young men and athletes of all ages.122,123 However, findings from two multicenter studies published in 2008 demonstrated that an early repolarization pattern was more-commonly seen in patients with documented idiopathic ventricular fibrillation than in healthy individuals, which suggests a potential association of J-point elevation with the J-wave and idiopathic ventricular fibrillation.124,125 On the basis of this emerging evidence, Antzelevitch and Yan used the term ‘J-wave syndromes’ to describe a loose spectrum of congenital and acquired disorders that includes Brugada syndrome and three distinct subtypes of early repolarization syndrome that might confer susceptibility for idiopathic ventricular fibrillation and that are differentiated on the basis of the spatial localization of the early repolarization pattern on the ECG.118

The best-characterized of the J-wave syndromes remains Brugada syndrome, a rare, heritable cardiac channelopathy that predisposes to syncope and sudden cardiac death. Brugada syndrome is characterized electro-cardiographically by coved-type ST-segment elevation (type I Brugada syndrome, BrS1; Figure 4) in the right precordial leads (V1–V3), with or without the presence of pseudo right bundle branch block, in the absence of ischemia, structural heart disease, and pharmacological agents known to induce a Brugada-syndrome-like ECG pattern.121,126 Brugada syndrome is estimated to affect 5 in 10,000 individuals,121 predominantly men in the fourth decade of life, and carries a yearly event rate of 7.7% in symptomatic individuals and 0.5% in asymptomatic individuals (approximately 1.4% overall).127

Two hypotheses exist for the origin of the electrocardiographic and arrhythmogenic manifestations of Brugada syndrome at the cellular and ionic level. The ‘repolarization theory’ suggests that the presence of a prominent, unopposed Ito in the right ventricular epicardium, as a result of either insufficient inward depolarizing currents (INa and ICa) or enhanced outward currents (IKATP or Ito), causes the heterogeneous loss of the action-potential dome, abnormalities of the J-point and J-wave, ST-segment elevation, and initiation of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation via phase 2 re-entry (Figure 4b).118 By contrast, the ‘depolarization theory’ suggests that conduction delays in the right ventricular ouflow tract might provide the substrate for re-entry and the initiation of ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation.128

Genetic basis

In 2008, Haissaguerre and colleagues described the case of a girl aged 14 years who presented with multiple episodes of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation that were associated with a marked, early repolarization pattern in the inferolateral leads (early repolarization syndrome type 2). The patient was found to harbor a Ser422Leu mutation in the KCNJ8-encoded Kir6.1 α subunit of the KATP channel.129 Subsequently, we discovered the same mutation in two unrelated cases: one individual with early repolarization syndrome and one with Brugada syndrome.130 Functional characterization of the KCNJ8-Ser422Leu mutation demonstrated that mutant Kir6.1 channels co-expressed with sulfonylurea receptor 2A in COS-1 cells produced a significantly larger IKATP in the presence of high concentrations of the K+-channel agonist pinacidil compared with nonmutated Kir6.1 channels.130 These data suggest that the mutant Kir6.1 channels fail to close adequately in response to increased intracellular ATP levels, which indicates that IKATP gain-of-function mutations might serve as the pathogenic substrate for some cases of Brugada syndrome and early repolarization syndrome. The predominant expression of Kir6.1 in the epicardium of mice,131 and the observation that epicardial predominant activation of Kir6.1 channels occurs during ischemia, led to the conclusion that the presence of an additional, epicardial, predominant, outward repolarizing current that is superimposed on the intrinsic Ito-mediated transmural voltage gradient might serve as the pathogenic basis for KCNJ8-mediated Brugada syndrome and early repolarization syndrome.

Although Ito has long been central to the repolarization theory, over the past 5 years, molecular evidence has emerged that directly implicates perturbations in Ito in disease pathogenesis. In 2008, Delpon and colleagues described a loss-of-function mutation (Arg99His) in the negatively modulating KCNE3-encoded MiRP2 Kv4.3 β subunit that was associated with Brugada syndrome and significantly increased Ito amplitude in vitro.132 After this initial evidence that Ito gain-of-function mutations could, indeed, contribute to the pathogenesis of Brugada syndrome, we identified two distinct missense mutations (Leu450Phe and Gly600Arg) in the KCND3-encoded Kv4.3 channel in two unrelated cases of Brugada syndrome.133 In vitro expression of KCND3-Leu450Phe and KCND3-Gly600Arg with the KCNIP2-encoded β subunit Kv-channel-interacting protein 2 demonstrated that both mutations conferred a marked gain-of-function in Ito. Furthermore, data obtained using an established mathematical model of ventricular action potentials (Luo–Rudy II) demonstrated that the increase in Ito that is associated with the heterozygous expression of both KCND3-Leu450Phe and KCND3-Gly600Arg in the heart produced a marked and stable loss of the action-potential dome in the right ventricular epicardium.133

Diagnosis and risk stratification

A BrS1 ECG pattern can arise spontaneously at rest or be induced by class I sodium-channel blockers (such as flecainide, amjaline, or procainamide).121 Placement of the right precordial leads in the second and third intercostal spaces improves detection of a BrS1 ECG pattern.121,134,135 Importantly, the presence of a Brugada-syndrome-like ECG pattern in isolation should not serve as the sole basis for the diagnosis of Brugada syndrome; a definitive diagnosis should be made only in patients with a diagnostic ECG that have at least one of the additional key diagnostic criteria in their personal or family history (Box 1).

Box 1 |. Diagnostic criteria for Brugada syndrome.

The type 1 (cove-shaped) Brugada ECG pattern detected in ≥2 right precordial ECG leads (V1–V3),* with at least one of the following:

Documented polymorphic VF or VT

Family history of sudden cardiac death <40 years of age

Presence of a type 1 Brugada ECG pattern in family member(s)

Inducible VF or VT during programmed electrical stimulation

Syncope

Nocturnal agonal respiration

*Spontaneously or in the presence of sodium-channel blockers. Abbreviations: ECG, electrocardiogram; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

The identification of susceptibility mutations for Brugada syndrome and early repolarization syndrome in KCNJ8, KCNE3, and KCND3 that result in IKATP and Ito gain-of-function have established a potential role for K+ channels in the pathogenesis of J-wave syndromes. However, the clinical utility and implications of these discoveries remains unknown. Unfortunately, as cases of Brugada syndrome that are associated with mutations in KCNE (BrS5), KCNJ8 (BrS8), and KCND3 (BrS9) are rare, no meaningful genotype–phenotype relationships involving K+-channel-mediated Brugada syndrome have been established at this point. Notably, however, the conduction abnormalities associated with mutations in SCN5A (BrS1)—such as PR-interval lengthening, QRS abnormalities, pronounced right bundle branch block, among others—have not been observed in K+-channel-mediated Brugada syndrome.

Patient management

Regardless of genotype, all symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with Brugada syndrome should be advised to avoid drugs that are known to exacerbate the condition (such as sodium-channel blockers). Given that fever can enhance the electrocardiographic and arrhythmogenic manifestations of Brugada syndrome, patients should also be advised to take an over-the-counter antipyretic agent (for example acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug) if they contract a febrile illness. ICD use currently remains the only known treatment to prevent sudden cardiac death effectively in symptomatic patients with Brugada syndrome. However, several anecdotal reports have indicated that quinidine, a class Ia antiarrhythmic that also blocks Ito, suppresses ventricular arrhythmias in high-risk patients with Brugada syndrome and those with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation or early repolarization syndrome.129,136 A prospective registry has been established to address the lack of empirical evidence regarding the use of quinidine in the medical management of J-wave syndromes.137

Familial AF

AF is the most-commonly encountered, sustained cardiac arrhythmia in clinical practice. Although AF is not generally considered to be a heritable disease, data indicate that as many as 5% of all patients with AF and up to 15% of patients with lone AF (defined as AF in the absence of structural heart disease) might have a familial form of the disease.138 Three distinct genetic patterns are tied to AF: firstly, monogenic familial AF; secondly, familial AF associated with other heritable diseases that include structural causes (such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and dilated cardiomyopathies) or channelopathic causes (such as LQTS, Brugada syndrome, and SQTS); and thirdly, nonfamilial AF linked to AF-predisposing genetic backgrounds.

Monogenic familial AF is an autosomal-dominant condition characterized by the absence of P-waves and F-waves, as well as an inconsistent R–R interval on the ECG. Similar to acquired AF, monogenic familial AF is associated with serious complications, including stroke, systemic embolization, and sudden death. Collectively, familial AF is associated with 16 distinct genetic loci and mutations in seven K+-channel α or β subunits that result in IKs gain-of-function (KCNQ1 and KCNE5), IKr gain-of-function (KCNH2 and KCNE2), IK1 gain-of-function (KCNJ2), IKur loss-of-function (KCNA5), and perturbed IKATP function (ABCC9).139 However, most of these mutations have been discovered in isolated patients or families and, therefore, preclude the development of meaningful genotype–phenotype correlations, risk stratification strategies, or specific therapies for monogenic familial AF.

Conclusions

Fundamental advances in our understanding of the molecular and cellular basis of K+-channel-mediated cardiac channelopathies have allowed the enumeration of various clinically useful genotype–phenotype correlations. However, 20–25% of LQTS cases, 60–65% of Brugada syndrome cases, and even more cases of early repolarization syndrome, idiopathic ventricular fibrillation, SQTS, and familial AF remain genetically elusive. The emergence of next-generation sequencing platforms and the reduced cost and wider availability of existing sequencing technologies promise to result in the rapid identification of novel disease-susceptibility genes and greatly expand the number of known disease-causative mutations in established genes. These advances will undoubtedly lead to the elucidation of novel pathophysiological mechanisms and enhance our understanding of the biophysical properties, clinical manifestations, and therapeutic responses associated with particular mutations. Such insights might eventually pave the way for the development of refined genotype-specific, and potentially even mutation-specific, risk-stratification strategies and therapies. Although still years away from reaching the clinical setting, the continued development of novel classes of antiarrhythmic drug—such as activators of IKr, IKs, and IK1—promises to lead to the development of tailored pharmacological regimens. Such regimens would be designed to enhance phase 3 and phase 4 repolarization reserve by targeting the precise molecular mechanisms that are responsible for K+-channel-mediated diseases. The development of risk-stratification strategies and medical therapeutic options for diseases arising from gain-of-function mutations in K+ channels is of particular importance given the substantial comorbidities and complications associated with ICDs. Furthermore, the elucidation of environmental, genetic, and epigenetic factors that contribute to the markedly variable disease expressivity and incomplete disease penetrance associated with cardiac channelopathies will further enhance the ability of clinicians to risk-stratify and manage individuals afflicted by these potentially lethal, yet highly treatable, genetic disorders.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

K+ channels represent the largest and most-functionally diverse family of ion channels encoded in the human genome and have a critical role in the restitution of cardiac action potentials

Loss-of-function mutations in the α and β subunits that conduct IKs, IKr, and IK1 are associated with long QT syndrome (LQTS)

Genotype-specific approaches to the diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment of patients with LQTS type 1 or type 2 should be utilized

Gain-of-function mutations in the α and β subunits that conduct Ito, IKs, IKr, IK1, and IKATP are associated with short QT syndrome, J-wave syndromes, and familial atrial fibrillation

The entire clinical picture should be assessed during the diagnosis of K+ channelopathies, including a 12-lead electrocardiogram, genetic tests, and a patient’s clinical and family history

Review criteria.

A search for original articles focusing on K+-channel mutations and arrhythmias was performed in PubMed. The search terms employed included “potassium channel”, “mutation”, and “arrhythmia” in various permutations. No data limitations were applied. All papers identified were full-length manuscripts (excluding abstracts or preliminary reports) written in English. In addition, the reference lists of these articles were searched to identify additional pertinent articles.

Acknowledgments

M. J. Ackerman is supported by the Mayo Clinic Windland Smith Rice Comprehensive Sudden Cardiac Death Program and the National Institutes of Health (R01-HD42569 and P01-HL094291). J. R. Giudicessi is supported by a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Kirschstein NRSA Individual Predoctoral MD/PhD Fellowship (F30-HL106993).

Footnotes

Competing interests

M. J. Ackerman declares associations with the following companies: Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, St. Jude Medical, and Transgenomic. See the article online for full details of the relationships. J. R. Giudicessi declares no competing interests.

Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nrcardio

Contributor Information

John R. Giudicessi, Mayo Medical School, Mitchell Student Center BA-07, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905, USA.

Michael J. Ackerman, Mayo Clinic Windland Smith Rice Sudden Death Genomics Laboratory, Guggenheim 501, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905, USA.

References

- 1.Nerbonne JM & Kass RS Molecular physiology of cardiac repolarization. Physiol. Rev 85, 1205–1253 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Q et al. Positional cloning of a novel potassium channel gene: KVLQT1 mutations cause cardiac arrhythmias. Nat. Genet 12, 17–23 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curran ME et al. A molecular basis for cardiac arrhythmia: HERG mutations cause long QT syndrome. Cell 80, 795–803 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plaster NM et al. Mutations in Kir2.1 cause the developmental and episodic electrical phenotypes of Andersen’s syndrome. Cell 105, 511–519 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hedley PL et al. The genetic basis of Brugada syndrome: a mutation update. Hum. Mutat 30, 1256–1266 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campuzano O & Brugada R Genetics of familial atrial fibrillation. Europace 11, 1267–1271 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gollob MH, Redpath CJ & Roberts JD The short QT syndrome: proposed diagnostic criteria. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 57, 802–812 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravens U & Cerbai E Role of potassium currents in cardiac arrhythmias. Europace 10, 1133–1137 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clancy CE & Kass RS Inherited and acquired vulnerability to ventricular arrhythmias: cardiac Na+ and K+ channels. Physiol. Rev 85, 33–47 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel C & Antzelevitch C Pharmacological approach to the treatment of long and short QT syndromes. Pharmacol. Ther 118, 138–151 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wulff H, Castle NA & Pardo LA Voltage-gated potassium channels as therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 8, 982–1001 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coetzee WA et al. Molecular diversity of K+ channels. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 868, 233–285 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snyders DJ Structure and function of cardiac potassium channels. Cardiovasc. Res 42, 377–390 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacKinnon R Pore loops: an emerging theme in ion channel structure. Neuron 14, 889–892 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bezanilla F & Stefani E Gating currents. Methods Enzymol 293, 331–352 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamargo J, Caballero R, Gomez R, Valenzuela C & Delpon E Pharmacology of cardiac potassium channels. Cardiovasc. Res 62, 9–33 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pongs O & Schwarz JR Ancillary subunits associated with voltage-dependent K+ channels. Physiol. Rev 90, 755–796 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giles WR & Imaizumi Y Comparison of potassium currents in rabbit atrial and ventricular cells. J. Physiol 405, 123–145 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schram G, Pourrier M, Melnyk P & Nattel S Differential distribution of cardiac ion channel expression as a basis for regional specialization in electrical function. Circ. Res 90, 939–950 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wettwer E, Amos GJ, Posival H & Ravens U Transient outward current in human ventricular myocytes of subepicardial and subendocardial origin. Circ. Res 75, 473–482 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Litovsky SH & Antzelevitch C Transient outward current prominent in canine ventricular epicardium but not endocardium. Circ. Res 62, 116–126 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shinagawa Y, Satoh H & Noma A The sustained inward current and inward rectifier K+ current in pacemaker cells dissociated from rat sinoatrial node. J. Physiol 523, 593–605 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anumonwo JM, Delmar M & Jalife J Electrophysiology of single heart cells from the rabbit tricuspid valve. J. Physiol 425, 145–167 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mangoni ME & Nargeot J Genesis and regulation of the heart automaticity. Physiol. Rev 88, 919–982 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ackerman MJ & Clapham DE Ion channels-basic science and clinical disease. N. Engl. J. Med 336, 1575–1586 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morita H, Wu J & Zipes DP The QT syndromes: long and short. Lancet 372, 750–763 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antzelevitch C Role of spatial dispersion of repolarization in inherited and acquired sudden cardiac death syndromes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol 293, H2024–H2038 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moss AJ Long QT Syndrome. JAMA 289, 2041–2044 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz PJ et al. Prevalence of the congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation 120, 1761–1767 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz PJ et al. The Jervell and Lange– Nielsen syndrome: natural history, molecular basis, and clinical outcome. Circulation 113, 783–790 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Splawski I et al. Spectrum of mutations in long-QT syndrome genes. KVLQT1, HERG, SCN5A, KCNE1, and KCNE2. Circulation 102, 1178–1185 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tester DJ, Will ML, Haglund CM & Ackerman MJ Compendium of cardiac channel mutations in 541 consecutive unrelated patients referred for long QT syndrome genetic testing. Heart Rhythm 2, 507–517 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barhanin J et al. KvLQT1 and lsK (minK) proteins associate to form the IKs cardiac potassium current. Nature 384, 78–80 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanguinetti MC et al. Coassembly of KvLQT1 and minKv(IsK) proteins to form cardiac IKs potassium channel. Nature 384, 80–83 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gouas L et al. New KCNQ1 mutations leading to haploinsufficiency in a general population; defective trafficking of a KvLQT1 mutant. Cardiovasc. Res 63, 60–68 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmitt N et al. A recessive C-terminal Jervell and Lange–Nielsen mutation of the KCNQ1 channel impairs subunit assembly. EMBO J 19, 332–340 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marx SO et al. Requirement of a macromolecular signaling complex for beta adrenergic receptor modulation of the KCNQ1– KCNE1 potassium channel. Science 295, 496–499 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park KH et al. Impaired KCNQ1–KCNE1 and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate interaction underlies the long QT syndrome. Circ. Res 96, 730–739 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Labro AJ, Boulet IR, Timmermans JP, Ottschytsch N & Snyders DJ The rate-dependent biophysical properties of the LQT1 H258R mutant are counteracted by a dominant negative effect on channel trafficking. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol 48, 1096–1104 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen J et al. A dual mechanism for IKs current reduction by the pathogenic mutation KCNQ1–S277L. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol 34, 1652–1664 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lo CF & Numann R Independent and exclusive modulation of cardiac delayed rectifying K+ current by protein kinase C and protein kinase A. Circ. Res 83, 995–1002 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen L et al. Mutation of an A-kinase-anchoring protein causes long-QT syndrome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U. S. A 104, 20990–20995 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwartz PJ et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation in the long-QT syndrome: gene-specific triggers for life-threatening arrhythmias. Circulation 103, 89–95 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moss AJ et al. ECG T-wave patterns in genetically distinct forms of the hereditary long QT syndrome. Circulation 92, 2929–2934 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimizu W et al. Epinephrine unmasks latent mutation carriers with LQT1 form of congenital long-QT syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 41, 633–642 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horner JM, Horner MM & Ackerman MJ The diagnostic utility of recovery phase QTc during treadmill exercise stress testing in the evaluation of long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm 8, 1698–1704 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vyas H, Hejlik J & Ackerman MJ Epinephrine QT stress testing in the evaluation of congenital long-QT syndrome: diagnostic accuracy of the paradoxical QT response. Circulation 113, 1385–1392 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vincent GM, Jaiswal D & Timothy KW Effects of exercise on heart rate, QT, QTc and QT/QS2 in the Romano-Ward inherited long QT syndrome. Am. J. Cardiol 68, 498–503 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ackerman MJ et al. Epinephrine-induced QT interval prolongation: a gene-specific paradoxical response in congenital long QT syndrome. Mayo Clin. Proc 77, 413–421 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wong JA et al. Utility of treadmill testing in identification and genotype prediction in long-QT syndrome. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol 3, 120–125 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jones EM, Roti Roti EC, Wang J, Delfosse SA & Robertson GA Cardiac IKr channels minimally comprise hERG 1a and 1b subunits. J. Biol. Chem 279, 44690–44694 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phartiyal P, Jones EM & Robertson GA Heteromeric assembly of human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG) 1a/1b channels occurs cotranslationally via N-terminal interactions. J. Biol. Chem 282, 9874–9882 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roden DM & Viswanathan PC Genetics of acquired long QT syndrome. J. Clin. Invest 115, 2025–2032 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abbott GW et al. MiRP1 forms IKr potassium channels with HERG and is associated with cardiac arrhythmia. Cell 97, 175–187 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Isbrandt D et al. Identification and functional characterization of a novel KCNE2 (MiRP1) mutation that alters HERG channel kinetics. J. Mol. Med 80, 524–532 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gordon E et al. A KCNE2 mutation in a patient with cardiac arrhythmia induced by auditory stimuli and serum electrolyte imbalance. Cardiovasc. Res 77, 98–106 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu Y, Mahaut-Smith MP, Huang CL & Vandenberg JI Mutant MiRP1 subunits modulate HERG K+ channel gating: a mechanism for pro-arrhythmia in long QT syndrome type 6. J. Physiol 551, 253–262 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weerapura M, Nattel S, Chartier D, Caballero R & Hebert TE A comparison of currents carried by HERG, with and without coexpression of MiRP1, and the native rapid delayed rectifier current. Is MiRP1 the missing link? J. Physiol 540, 15–27 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pourrier M, Zicha S, Ehrlich J, Han W & Nattel S Canine ventricular KCNE2 expression resides predominantly in Purkinje fibers. Circ. Res 93, 189–191 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jiang M et al. KCNE2 protein is expressed in ventricles of different species, and changes in its expression contribute to electrical remodeling in diseased hearts. Circulation 109, 1783–1788 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou Z, Gong Q, Epstein ML & January CT HERG channel dysfunction in human long QT syndrome. Intracellular transport and functional defects. J. Biol. Chem 273, 21061–21066 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Anderson CL et al. Most LQT2 mutations reduce Kv11.1 (hERG) current by a class 2 (trafficking-deficient) mechanism. Circulation 113, 365–373 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rajamani S, Anderson CL, Anson BD & January CT Pharmacological rescue of human K+ channel long-QT2 mutations: human ether-a-go-go-related gene rescue without block. Circulation 105, 2830–2835 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yao Y et al. Aminoglycoside antibiotics restore functional expression of truncated HERG channels produced by nonsense mutations. Heart Rhythm 6, 553–560 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Paulussen A et al. A novel mutation (T65P) in the PAS domain of the human potassium channel HERG results in the long QT syndrome by trafficking deficiency. J. Biol. Chem 277, 48610–48616 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Robertson GA & January CT HERG trafficking and pharmacological rescue of LQTS-2 mutant channels. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol 171, 349–355 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wilde AA et al. Auditory stimuli as a trigger for arrhythmic events differentiate HERG-related (LQTS2) patients from KVLQT1-related patients (LQTS1). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 33, 327–332 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rashba EJ et al. Influence of pregnancy on the risk for cardiac events in patients with hereditary long QT syndrome. Circulation 97, 451–456 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Khositseth A, Tester DJ, Will ML, Bell CM & Ackerman MJ Identification of a common genetic substrate underlying postpartum cardiac events in congenital long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm 1, 60–64 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang L et al. Electrocardiographic features in Andersen–Tawil syndrome patients with KCNJ2 mutations: characteristic T–U-wave patterns predict the KCNJ2 genotype. Circulation 111, 2720–2726 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arizona Center for Education and Research on Therapeutics. QT Drug Lists by Risk Groups [online], http://www.qtdrugs.org (2012).

- 72.Rautaharju PM et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part IV: the ST segment, T and U waves, and the QT interval: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society: endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. Circulation 119, e241–e250 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Priori SG, Napolitano C & Schwartz PJ Low penetrance in the long-QT syndrome: clinical impact. Circulation 99, 529–533 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Taggart NW, Haglund CM, Tester DJ & Ackerman MJ Diagnostic miscues in congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation 115, 2613–2620 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]