Abstract

Nonmarital pregnancy increases the likelihood of entering a marital or cohabiting union. The timing of a pregnancy within the life course of an individual or relationship duration may also impact the likelihood of forming coresidential unions and their stability. This study examines the association between non-marital pregnancy and first union formation and how this varies across age. It also considers whether the influence of pregnancy on the stability of cohabitations shifts across their duration. Using data on young adults in the U.S. (Add Health), competing-risk event-history models examine the time-varying influence of pregnancy on union formation and stability. Findings suggest that pregnancy is more strongly associated with union formation during adolescence, becoming less influential as women age. Within cohabitations, pregnancy had a bigger impact on increasing the likelihood of marriage early within unions, but the longer a couple cohabited the less likely they were to transition to marriage when pregnant.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Cohabitation, Marriage, Union Formation, Union Stability, Timing

Research suggests that relationship transitions, into or out of cohabitations and marriages, are strongly impacted by pregnancy (Brien, Lillard, & Waite, 1999; Manning 2004; Guzzo, 2006; Lichter, Sassler, & Turner, 2014). There has been significant growth in the experience of “shot-gun cohabitations” in recent decades and fewer transitions into a first marriage following a nonmarital conception (England, Fitzgibbons, & Wu, 2012; Lichter 2012). Pregnancy appears to be more of a precursor to cohabitation than it is to marriage (Rackin & Gibson-Davis, 2012; Lichter, et al. 2014; Su, Dunifon, & Sassler, 2015).

The pregnancy period may be a particularly fluid time in non-marital relationships as couples transition from one relationship status to another. Non-marital pregnancies that result in a live birth may act as a catalyst for relationship progression, from a non-coresidential relationship to cohabitation or marriage and from cohabitation to marriage. Decisions about marriage and childbirth may also be jointly determined among cohabiting couples (Wu & Musick, 2008). For some couples, family formation events cluster temporally, with decisions to have children and enter into coresidential unions occurring simultaneously. Alternatively, pregnancy may increase the likelihood of relationship dissolution as couples renegotiate the terms of their relationship with an impending child. The timing of when a pregnancy occurs within the context of a cohabiting relationship may be important for the stability and trajectory of the union. Limited research has examined how the timing of a pregnancy within the duration of a cohabiting union is associated with a couple’s relationship trajectory.

Pregnancy may motivate different relationship decisions, depending on the characteristics of the individuals involved or the relationship. While for some couples a nonmarital conception may increase their likelihood of marrying or cohabiting, the role that pregnancy plays for the trajectory of a relationship may vary depending on the age of the individuals involved as well as the timing of when the pregnancy occurs within the duration of the relationship. Using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), this study examines the role that non-marital pregnancy plays on the likelihood that couples enter into first cohabiting unions or marriages, as well as the association between pregnancies occurring within first cohabiting unions and the likelihood that unions dissolve or transition to marriage. Using an event-history modeling framework, the timing of pregnancy within first cohabitations is specifically modeled, to see if pregnancies that result in a live birth have a different association with relationship transitions depending on the age of respondents as well as when in the course of a cohabiting relationship the pregnancy occurs. The current study thereby makes two important contributions to the literature. First, by examining the age-graded association between pregnancy and first union formation. Second, by testing whether the association between pregnancy and union transitions shifts across time the longer a cohabiting couple has been living together. Results suggest that the timing of pregnancy matters for the relationship formation and stability of first cohabiting unions, with a decreasing association between pregnancy and first union formation as people age and a decreasing association between pregnancy and transitioning to marriage across the duration of cohabiting unions.

The current study is particularly focused on the association between pregnancy and transitions into first coresidential unions and within first cohabiting unions. First coresidential unions are conceptually distinct from higher-order unions. The majority of Americans only cohabit or marry once (Cohen & Manning, 2010; Lichter, Turner, & Sassler, 2010; Kreider & Ellis, 2011). First cohabiting unions also tend to be more stable and more likely to transition into marriage, while women in higher-order cohabitations tend to be more socioeconomically disadvantaged (Lichter & Quian, 2008). Therefore, by focusing on first coresidential unions we capture a larger and more representative portrait of union transitions among American women.

Background

While research largely finds that nonmarital pregnancy increases the likelihood of coresidential union formation (Brien, et al., 1999), such unions are fairly fragile. Over sixty percent of non-marital unions end within five years of the birth of their child (McLanahan & Beck, 2010). The linkage between nonmarital births and union instability may be driven by the unintended nature of nonmarital conceptions, with unintended pregnancies more common among unmarried couples (Musick, 2002; Guzzo & Hayford, 2012). Further, the unintended nature of nonmarital pregnancies coupled with the stress of economic disadvantage faced by many of these young couples may exacerbate relationship tensions during this period (Edin & Tach, 2012). Union stability is also heavily influenced by residential status, with individuals who were cohabiting at the time of their child’s birth significantly more likely to still be together in a cohabiting relationship or have transitioned to marriage compared to couples who were romantically-involved but not cohabiting at the time of their child’s birth (Carlson, McLanahan, & England, 2004; McLanahan & Beck, 2010). While union stability is relatively high between the time of non-marital conceptions and birth, research finds that almost a fifth of women who were not in a coresidential union at conception were cohabiting with their partner by the birth (Lichter et al. 2014). Couples who conceived a child prior to coresidential union formation have an increased likelihood of experiencing a union dissolution after their child’s birth (Osborne, Manning, & Smock, 2007). The relationships of cohabiting partners who transition to marriage after the birth of a child appear to be becoming more stable over historical time, presumably as these family-building patterns become more normative (Musick & Michelmore, 2015).

Pregnancy generally increases the likelihood of transitioning into a more formalized, residential union. Research also points to the fragile nature of these unions, with many relationships that experience nonmarital pregnancies and births dissolving within a few years. A limited body of research has explored the association between non-residential pregnancies and the likelihood of entering into a cohabitation or marriage (Rackin & Gibson-Davis, 2012; Lichter, et al., 2014), finding that non-residential pregnancy is more likely to lead to cohabitation than marriage. Research has also examined pregnancies within cohabiting unions, finding that the majority of pregnant cohabiting women remain cohabiting prior to the birth of their child (Licter et al, 2014; Raley, 2001) but are more likely to transition to marriage than breakup when they become pregnant (Lichter et al, 2014). Other factors, including unintended pregnancies, economic disadvantage, drug and alcohol abuse, and relationship conflict may increase the likelihood that couples break-up during the pregnancy period (Lichter et al., 2014; Edin & Tach, 2012).

This research, however, has not explicitly examined how the timing of nonmarital pregnancy impacts the likelihood of these relationship transitions. That is, does the impact of pregnancy on the likelihood of entering into a first cohabitation or marrying one’s partner depend on the age when the person becomes pregnant? Secondly, among those who are cohabiting at a nonmarital conception, does the timing of pregnancy within the course of one’s relationship duration impact the likelihood that the relationship transitions to marriage, remains cohabiting, or dissolves? Modeling pregnancy in a time-varying, dynamic fashion, elucidates how the association between pregnancy and union transitions shift over time. Understanding how the association between nonmarital pregnancy and union formation changes as people age may provide insight into age-graded trends in non-marital childbearing and the context of childrearing (Ventura, 2009). Findings about the shifting role of pregnancy across the duration of cohabiting unions will also inform our understanding of the diversity of experiences within cohabitations. Variation in the association between pregnancy and union stability over cohabitation duration may point to shifts in the meaning of childbearing over the course of a relationship in this growing family form.

Conceptual Frameworks

Life course theory and exchange theories of relationship development act as useful conceptual frameworks for understanding the shifting influence of pregnancy on romantic relationship behavior over time. Age acts to structure the life course and the norms and expectations for behavior (Elder, 1994; Settersten, 2004). Therefore, the linkages between interrelated family-building behavior (pregnancy and union transitions) may shift over time as do age-graded constraints, opportunities, and expectations for behavior (Liefbroer, 1999). The economic and social constraints facing individuals who experience a non-marital conception during adolescence may preclude them from transitioning into a coresidential union or a legal marriage, while the economic and social circumstances of individuals who become nonmaritally pregnant in young adulthood may better enable them to form a coresidential union. Alternatively, the social stigmas surrounding teenage pregnancy (Wilson & Huntington, 2006; Mollburn, 2010) and the more limited economic circumstances of these teens (Child Trends, 2015) might also contribute to pressures to legitimize these unions and combine resources by transitioning into a coresidential or marital union. Adolescent pregnancies are significantly more likely to occur outside of marriage compared to later pregnancies (Child Trends, 2015), and the likelihood of entering into cohabiting or marital unions is significantly lower among teenagers, increasing as individuals age (Manning, Brown, & Payne, 2014). Therefore, it is hypothesized that becoming pregnant will increase the likelihood that individuals begin cohabiting or marry, but this increased likelihood of union formation will be stronger at older ages.

Hypothesis 1:

Becoming pregnant will increase the likelihood that women begin cohabiting with or marry their partner, and this likelihood will increase at older ages.

Prior research supports this hypothesis, finding that pregnant women over the age of 25 who were single or cohabiting at conception were significantly more likely to be married by the birth and less likely to have broken up compared to younger pregnant women under age 25 (Lichter, et al., 2014). This research is largely descriptive, however, and does not test whether the probability of entering into a union by pregnancy status shifts as women age.

The timing of a pregnancy within the context of a relationship might also impact the likelihood of relationship transitions. Over the course of a relationship the perceived costs and benefits of different partner characteristics and experiences may shift; the interpretation and reaction of different relationship events (such as pregnancy) likely differ depending on when these events occur within the context of the larger relationship history. Social exchange theories of relationship development argue that while individuals seek to maximize their rewards and minimize risk within relationships, these evaluations of costs and benefits are dynamic and shift as relationships progress (Rusbult & Buunk, 1993; Regan, 2008). Couples that become pregnant early within a cohabiting relationship, soon after moving in together, may experience heightened relationship distress and an increased likelihood of dissolution, or may move to formalize their union in marriage as they renegotiate the terms of their newly formed union. The decisions to have a child and to transition into a cohabiting or marital union may also occur jointly, therefore such family-building events may be more likely to occur around the same time (e.g. Wu & Musick, 2008). On the other hand, couples who become pregnant after years of living together having not yet transitioned to marriage may be more likely to remain cohabiting, as such a union has proven to them to be a stable relationship form in which to raise a child. Long term cohabiters may also have strongly held rationales for not transitioning to legal marriage (e.g. Hatch, 2015) that may not be impacted by conception and pregnancy.

Research also suggests that pregnancy and childbirth negatively impacts relationship quality, with couples who were married longer before having their first child having a smaller decrease in relationship satisfaction after childbirth compared to those who had a child soon after marrying (Doss, Rhoades, Stanley, & Markman, 2010). Furthermore, relationship satisfaction is linked with a couples’ level of commitment to their relationship and their likelihood of union dissolution (Brown, 2000; Le & Agnew, 2003), and to a lesser extent the likelihood that cohabiters marry (Brown, 2000). Thus, the timing of when a pregnancy occurs within the timeline of a romantic relationship may impact the stability of that union, in part through its impact on relationship quality. It is therefore hypothesized that the influence of pregnancy on the likelihood of a cohabiting relationship transitioning to marriage or leading to dissolution will shift depending on the timing of the pregnancy within the cohabitation duration. Pregnancies that occur early in a cohabiting union are expected to increase both the likelihood of marriage and union dissolution while the likelihood of transitioning to marriage is expected to be lower among those who become pregnant after years of living together.

Hypothesis 2:

Pregnancies that occur within the early part of a cohabiting union are expected to increase the likelihood of both marriage and union dissolution. The likelihood of transitioning to marriage is expected to be lower when cohabitors become pregnant at later points in their cohabitation.

The current study explores the shifting influence of non-marital pregnancy on union transitions using an event-history modeling framework that tests whether the impact of pregnancy on union transitions is proportional across time. This study consists of two sets of analyses that answer two sets of questions. The first looks at the impact that non-marital pregnancy has on the likelihood of entering into a first coresidential union (a cohabitation or marriage) and whether this association is similar depending on the age when a person becomes pregnant. These analyses therefore help to answer the question of whether the association between nonmarital pregnancy and union formation is age-graded. The second set of analyses examines the influence of non-marital pregnancy within first cohabiting unions on the likelihood that individuals make the transition to legal marriage, dissolve their union, or remain cohabiting, and considers whether this association is similar depending on the timing of when the pregnancy occurs within the duration of the cohabitation. These analyses therefore help to answer the question of whether the association between nonmarital pregnancy and union stability changes over the course of a cohabiting relationship.

These two research questions jointly examine whether the association between pregnancy and making a transition in union status changes over time. Previous research has relied on the assumption that non-marital pregnancy is associated with union transitions in similar ways across age and union duration. However, principles of the life course perspective suggest that the timing of events may have different antecedents and consequences, and that development involves both continuity and change (Elder, Johnson, & Crosnoe, 2003). These principles call into question the inherent assumption of continuity in the effects of pregnancy on the lives of women that has been modeled in previous empirical investigations. Further, prior research suggests that the association between individual characteristics and union transitions does vary depending on the age of individuals (e.g. the earlier family environment; Thorsen, 2017) or the duration point in a cohabiting union (e.g. marital intentions; Parker, 2018). By considering both entrance into and stability within cohabiting unions, this study may inform our understanding of the dynamic nature of pregnancy for women’s relationships.

Method

Data and Sample

Data analyses were conducted using Waves I and IV of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), a nationally representative school-based survey of youth in grades 7 through 12 in the United States on their social and health behaviors (Harris et al., 2009). The study began during the 1994-1995 school year, with both an in-school and at-home questionnaire of students. A fourth wave of data-collection took place with in-home interviews of original respondents in 2007 and 2008, when respondents were between the ages of 24 and 32 (N = 15,701). Most measurements were drawn from this fourth wave of data collection, the latest available. Add Health is a useful survey to use when looking at cohabitation and pregnancy behavior, as it collects detailed relationship, pregnancy, and birth calendars for a nationally representative sample of men and women and follows this sample longitudinally from adolescence into young adulthood, when the majority of first transitions into coresidential unions occur.

Individuals who participated at both Wave I and Wave IV who had a valid sample weight were included in the current study (n = 14,800). Individuals who reported they had married or cohabited but were missing important date information to determine the type and timing of first coresidential union were excluded (n = 662). The sample was limited to those individuals whose first residential union was heterosexual, given the legal restrictions facing individuals in same-sex relationships for entering marriages during this time period (n=258). Individuals who entered into a coresidential union at age 15 or earlier (n = 206) were excluded from the analytic sample, given legal restrictions on the age at marriage (typically age 16 with parental consent). Finally, given concerns about the validity of men’s fertility data and the potential for under-reporting, particularly of non-marital pregnancies and births, the current study only examines the fertility experiences of women (Rendall, Clarke, Peters, Ranjit, & Verropoulou, 1999). After these exclusions the final analytic sample for the first set of analyses was 7,288 women who were not in a coresidential relationship at age 15 and available to enter into their first coresidential union. The second set of analyses examining the trajectory of first cohabiting unions was further restricted to the subset of women whose first union was a cohabitation, after excluding a small number of people (n = 37) who were missing important date information on union duration (analytic sample n = 4,754).

Measures

Dependent Variables.

In the first set of analyses the dependent variable is type of first residential union formed, if any. Information collected at Wave IV on the respondents’ romantic relationship histories was used to identify the first union, and type of union. Person-year observations were used as the unit of analysis, with the sample of 7,288 respondents contributing a total of 60,249 person years. As age is the unit of time in this analysis, person-years are used, given that chronological age is more meaningfully distinguished in year increments rather than month-increments. This categorical variable, first residential union, was coded as 0 “single (never married/cohabited)”, 1 “marriage”, or 2 “cohabitation”. Women who had not married or cohabited by Wave IV were censored and their age at the Wave IV interview was used as their final person-year observation. Tests of the functional form indicated that the baseline hazard could be categorized into four distinct age groups reflecting adolescence (age 16-18), early adulthood (19-23), the mid-twenties (24-28), and the late-twenties/early-thirties (ages 29-33), to capture the changing hazard of union formation. In order to test the proportionality assumption that pregnancy had a similar impact on union formation across age, interaction terms were generated between these age groups and the pregnancy measure to test if the impact of pregnancy varied depending on the age of the respondent. Age at cohabitation formation, in years, was used as a time-constant independent variable in the second set of analyses.

The dependent variable in the second set of analyses is the union-transition, break-up or marriage, of individuals out of their first cohabiting relationship. Relationship-specific information on the date of marriage or date of break-up (if applicable) were obtained from Wave IV relationship histories and ordered to determine the first relevant relationship transition experienced by women in their first cohabiting relationship. The unit of analysis was person-month of observation, with the 4,754 women in the analytic sample contributing 131,014 person-months. Cohabitation outcome, is a categorical variable coded as 0 “still together (cohabiting)”, 1 “married”, or 2 “broken up”. Respondents who were still cohabiting with their first cohabitation partner at Wave IV were censored and considered “still together”. Tests of the functional form of the baseline hazard indicated that a measurement schema of duration captured in one year increments up until year five, with a final category of five or more years for the remaining duration years was the best fitting and most interpretable specification of the changing hazard of cohabitation transitions. To test the proportionality assumption interaction terms were generated between cohabitation duration (in years) and pregnancy to test if the association between pregnancy and making a union transition varied by the year of cohabitation duration.

The current analyses focuses on transitions that occurred within the first seven years of a cohabiting union, given that the nature of making a transition to legal marriage or ending a union is perhaps quite different in long-term cohabitations. The small group of cohabiters who did make a transition after year seven (n = 147) were included in the analytic sample, but are coded as “still together” in a union throughout the period of observation. Therefore, the observation period began the month when the respondent first began cohabiting up until they broke-up or married their partner, were interviewed while still cohabiting at Wave IV, or until the first month of year seven in the cohabitation.

Pregnancy.

Information collected at Wave IV which captured the birth dates of all children using detailed fertility calendars was used to determine the date when respondents first became pregnant. The start dates of pregnancies were measured as eight months prior to the birth dates, in order to account for early births and lack of knowledge about pregnancy early in the first trimester, following the convention of other family demographers (Budig, 2003). This measure captures pregnancies that resulted in a live birth, similar to other research examining the association of pregnancy with cohabitation behavior (e.g. Rackin & Gibson-Davis, 2012; Lichter et al., 2014). Respondents were coded “1” for pregnancy in the person-year or person-months that corresponded with each period that they were pregnant. Thus, the binary indicator for pregnancy is time-varying across person-years and person-months so that people are given a “one” during periods when they are pregnant and a “zero” otherwise. To test whether the association of pregnancy with union formation or cohabitation stability varies across age/time, interaction terms were tested between pregnancy and age, and pregnancy and cohabitation duration.

Controls.

Several sociodemographic characteristics were included in the current study to control for their association with union formation behavior, including race, family structure during adolescence, educational attainment, and birth order. Race was a time-constant variable measured at Wave I with four categories: non-Hispanic white (68%), non-Hispanic Black (16%), Hispanic (12%), and non-Hispanic other race (4%; including Asian and Native American). Family structure was a time-constant, categorical variable measured using the Wave I household roster with four categories: married biological parent family (56%), married step-parent family (13%), single parent family (23%), and other family form (8%; includes cohabiting stepfamilies). Educational attainment was a time-varying variable capturing the highest degree obtained at each time point. This measure was constructed using information from Wave IV on the educational history of the respondents. For every person-year or person-month that the respondent may experience a censoring event (cohabitation or marriage in the first analyses, break-up or marriage in the second) individuals were given a value for their educational attainment up until that time point: less than a high school degree, high school degree, Associate’s degree, or Bachelor’s degree and beyond. A time-varying binary indicator of birth order was also included in all models (1 “second-order birth or higher”). The majority of women who became pregnant prior to first union formation (90%) or within their first cohabiting union (76%) were pregnant with their first child. Birth order was not significantly associated with union formation or cohabitation transition in any models (results available upon request). Results were the same when excluding women who had higher order births.

Analytic Strategy

The first set of analyses examines how pregnancies that result in a live birth impact the movement into first coresidential unions, while the second set of analyses explores the influence of pregnancies that result in live birth on the stability of first cohabiting unions and the timing of making a transition to marriage or union dissolution. Both analyses employ a discrete-time competing risk event history modeling approach. This method accounts for the competing likelihood that the first analytic sample of single individuals face of entering into a cohabiting or marital union and the competing likelihood that the second analytic sample of cohabiting individuals face of transitioning to legal marriage or breaking up. These models take the form of multinomial logistic regression models that estimate the relative risk of event occurrence at every time point of risk exposure up until the person-year of union formation and the person-month of cohabitation transition, or until the respondent is censored by the end of the study period. Person-years are used in the first set of analyses, as the unit of time is chronological age, which is more meaningfully distinguished in year increments rather than month-increments. Person-months are used in the second set of analyses, as the unit of time is cohabitation duration, to better capture union transitions occurring in quick succession (e.g. respondents begin cohabiting and transition to marriage four months later). To evaluate whether the impact of predictors on hazard rates were proportional across time (e.g. age and cohabitation duration) interactions with time were tested (Singer & Willett, 2003). To test this proportionality assumption a series of F-tests were administered to assess the improvement of model fit when including interaction terms between predictors and dummy variables for time (age in the first analyses and cohabitation duration in the second analyses). Post-estimation Wald tests were also performed to test for the significance of the combined main effect of predictors and interaction terms with time (e.g. sum of coefficient tests). Missing data was handled using multiple imputation procedures. Less than one percent of data was missing and imputed for race (10 people; .14% of the sample) and educational attainment (18 people; .25% of the sample). Fifty women reported a live birth but were missing date information on the birth, these dates were not imputed and therefore these pregnancies were not captured with the pregnancy variable (.69% of the sample). Analyses used appropriate weighting and adjustments for stratification and clustering to account for the complex survey design of Add Health, using the svy command in Stata 13.

In analyses modeling transitions within cohabiting unions adjustments were also made to control for the prior sorting of individuals into first cohabiting unions. The selection process of entering into a first cohabitation is over multiple alternatives (e.g. marrying directly or remaining outside of a coresidential union versus entering a cohabiting union), therefore a selection correction which accounts for this multinomial logit specification is preferred (Bourguignon, Fournier, & Gurgand, 2007). The multinomial selection correction proposed by Dubin and McFadden (1984) was employed. This correction essentially uses two inverse Mills ratios, one for the initial probability of cohabiting versus remaining outside of a coresidential union and one for the initial probability of cohabiting versus marrying directly. These corrections were calculated post-imputation in a two-step process by first estimating the predicted probabilities of alternative first union formation outcomes (e.g. remaining outside of a coresidential union or marrying directly) using the initial prediction model of union formation, and then these predicted probabilities were used to calculate the inverse Mills ratios (Bourguignon, et al., 2007; Dubin & McFadden, 1984). These inverse mills ratios were included in the final multivariate model, in order to account for any potential confounding. Results were the same without the inclusion of these controls. This suggests that the observed association between non-marital pregnancy and cohabitation outcomes was not due to the select nature of individuals who were in a first cohabiting union (versus married directly or still single/not in a coresidential union).

Results

Descriptive information on the analytic sample is presented in Table One. Among those women who were single at age 15, the majority entered into a cohabitation as their first union (67%), while 18% entered into a marriage directly and 16% remained single and were not in a coresidential union at the time of their interview at Wave IV, when they were 28 years old on average. In line with previous research on the frailty of cohabitating unions, almost half (49%) of first cohabiting unions in our sample dissolve. A sizeable minority (39%) transition their first cohabiting unions into marriage, while only a small minority of women remain cohabiting in their first cohabiting union by Wave IV (12%). Prior to entering a coresidential union (or Wave IV if remaining single), 14% of the sample experienced a non-marital conception at some time that resulted in a live birth. About 11% of those individuals who entered into a coresidential union (a marriage or cohabitation; n = 6,114), were pregnant at the time of union formation. Finally, among the subset of women whose first union was a cohabitation, 27% were pregnant at some point during their cohabitation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample*

| Variable | Mean/Percentage | Std. Error | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Wave 1 | 15.41 | 0.12 | 11-21 |

| Race | |||

| White | 68% | 0.03 | 0-1 |

| Black | 16% | 0.02 | 0-1 |

| Hispanic | 12% | 0.02 | 0-1 |

| Other Race | 4% | 0.01 | 0-1 |

| Family Structure | |||

| Married, biological parents | 56% | 0.01 | 0-1 |

| Married stepfamily | 13% | 0.01 | 0-1 |

| Single parent | 23% | 0.01 | 0-1 |

| Other family form | 8% | 0.01 | 0-1 |

| Age at Wave 4 | 28.26 | 0.12 | 24-34 |

| Characteristics at union entrance (among 1st time cohabiters) | |||

| Age at Union Entrance | 20.80 | 0.11 | 16-32 |

| Educational Attainment | |||

| Less than High School | 25% | 0.01 | 0-1 |

| High School | 52% | 0.01 | 0-1 |

| Associates/Vocational Degree | 7% | 0.00 | 0-1 |

| Bachelor’s or more | 16% | 0.01 | 0-1 |

| Dependent variable - type of first union | |||

| Single at Wave IV | 16% | 0.01 | 0-1 |

| Marriage is first union | 18% | 0.01 | 0-1 |

| Cohabitation as first union | 67% | 0.01 | 0-1 |

| Dependent variable - cohabitation outcome (among 1st time cohabiters) | |||

| Still cohabiting | 12% | 0.01 | 0-1 |

| Married | 39% | 0.01 | 0-1 |

| Broken up | 49% | 0.01 | 0-1 |

| Main independent variable - pregnancy | |||

| Pregnancy prior to entering a union | 14% | 0.01 | 0-1 |

| Pregnancy at union entrance a | 11% | 0.01 | 0-1 |

| Pregnancy within a cohabiting union | 27% | 0.01 | 0-1 |

Note:

descriptive statistics refer to the sample of individuals who were single at age 15 (n=7,288) unless otherwise noted as the sample of first-time cohabiters (n=4,754);

Among the subset of individuals who have a first union (n=6,114)

Table Two presents the results from multinomial logistic regression models predicting first union formation. Results indicate that at older ages women had a significantly higher likelihood of entering their first cohabitation or directly entering into a marriage, with a peak between the ages of 24 to 28. Being pregnant was associated with a significant increase in the likelihood that women entered into a coresidential union, but results indicate that the impact of pregnancy on union formation varied across age. During adolescence individuals who were pregnant were significantly more likely to enter into either a marriage directly (OR = 15.24) or a cohabiting union (4.95) rather than remain single compared to their non-pregnant age-mates. Over time, however, the association between pregnancy and union formation was reduced, with significantly smaller differences in the likelihood of entering a cohabitation or marriage directly by pregnancy status. For direct marriage, this pattern took a U-shape, with a statistically similar associations between marriage and pregnancy both during adolescence and in women’s early thirties. Wald tests of the sum of coefficients indicated that in women’s twenties differences in the odds of marriage by pregnancy status was significantly smaller; at all ages pregnant women had a significantly higher likelihood of entering into a marriage directly versus remaining outside of a coresidential union but this difference was largest during adolescence and women’s early-thirties. According to Wald tests of the sum of coefficients, when modeling the likelihood of entering a cohabitation, the association between pregnancy and union formation was reduced at older ages but remained a statistically significant predictor. Only in the late-twenties and early thirties did pregnancy have no impact on the likelihood that single women entered into a cohabiting union. Thus when women are in their early-thirties become pregnant, they have a higher likelihood of entering a marriage directly but not of entering into a cohabitation, relative to their non-pregnant peers.

Table 2.

Multivariate Models of First Union Formation

| Marriage | Cohabitation | Cohabitation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Remaining Single is reference) | (Marriage is reference) | |||||

| b | OR | b | OR | b | OR | |

| Pregnant | 2.724*** (0.19) | 15.24 | 1.599*** (0.12) | 4.95 | −1.125*** (0.21) | 0.34 |

| Pregnancy by Age interactions | ||||||

| Pregnant X Age 19-23 | −1.004*** (0.25) | 0.37 | −0.536*** (0.17) | 0.58 | 0.468^ (0.28) | 1.60 |

| Pregnant X Age 24-28 | −1.025** (0.35) | 0.36 | −0.311 (0.25) | 0.73 | 0.714^ (0.40) | 2.04 |

| Pregnant X Age 29 plus | −0.006 (1.22) | 0.99 | −1.078 (1.07) | 0.34 | −1.072 (1.56) | 0.34 |

| Age (16-18 ref) | ||||||

| Age 19-23 | 1.178*** (0.16) | 3.25 | 0.968*** (0.09) | 2.63 | −0.209 (0.15) | 0.81 |

| Age 24-28 | 1.238*** (0.22) | 3.45 | 0.968*** (0.13) | 2.63 | −0.270 (0.19) | 0.76 |

| Age 29 plus | 0.502 (0.38) | 1.65 | 0.516* (0.24) | 1.68 | 0.013 (0.37) | 1.01 |

| Constant | −6.373*** (0.17) | 0.00 | −3.913*** (0.11) | 0.02 | 2.460*** (0.19) | 11.70 |

Notes: results are weighted, adjust for clustering and stratification, and are based on multiply imputed data; standard errors are in parentheses; models include controls for race, family structure, education, and birth order;

p < .01

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

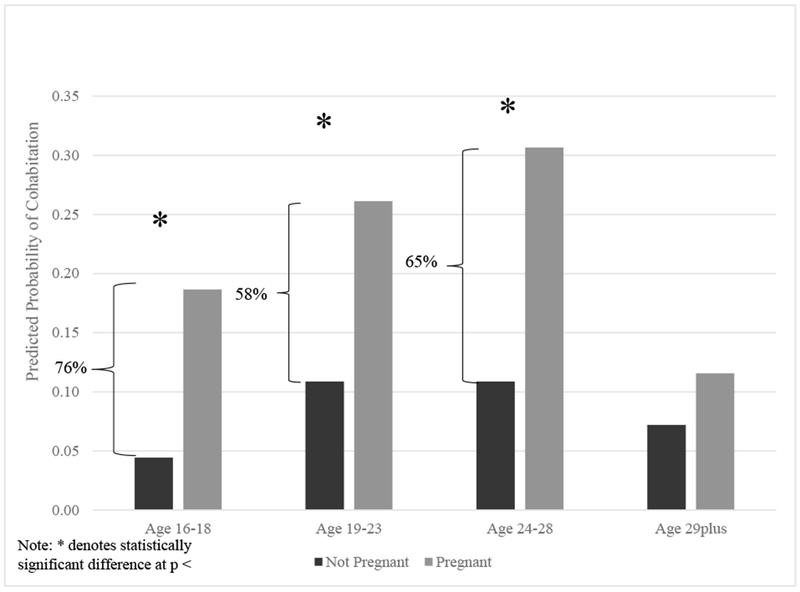

To help illustrate these results, the predicted probabilities that single women enter into a cohabitation (Figure 1) and a marriage (Figure 2) by their pregnancy status at various ages were calculated. All other variables in the model were held at their mean. As seen in Figure One, during adolescence pregnant women were much more likely to enter a marriage directly compared to their non-pregnant peers, while at older ages this difference is smaller. During adolescence, being pregnant was associated with a 93% higher predicted probability of marrying directly compared to those who were not pregnant. When considering cohabitation (Figure 2), at most ages pregnant women were significantly more likely to begin cohabiting than their non-pregnant peers, however this difference was largest during adolescence (76% higher predicted probability of cohabiting), and reduced during the early-twenties (58% higher predicted probability) and mid-twenties (65% higher predicted probability), with no statistically significant difference in the probability of cohabiting by pregnancy status in women’s early thirties.

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of entering a cohabitation across age by pregnancy status

Figure 2.

Predicted probability of entering a marriage directly across age by pregnancy status

Models estimating the stability of first cohabiting unions are presented in Table Three, which take the form of multinomial logistic regression models estimating the likelihood of transitioning to marriage, breaking-up, or remaining cohabiting among women in their first cohabiting union. Looking at the impact of cohabitation duration on cohabitation stability, results indicate that women were more likely to marry their partner rather than remain cohabiting the longer they have been living together, while the likelihood of breaking-up with their partner is reduced the longer they remain cohabiting. Pregnancies which occurred within the context of cohabiting unions were associated with the stability of those unions. However, results suggest that the association between pregnancy and the likelihood of marriage shifts across the duration of the cohabiting union. Being pregnant during the first year of cohabiting was associated with an increased odds of marrying one’s partner rather than remaining single (OR = 2.64). This higher likelihood of marrying one’s partner when pregnant was similar during the second and third years of cohabiting, but by the fourth year and later this difference was reduced. Wald tests of the sum of coefficients indicate that this difference converges and was no longer statistically significant, such that by the fourth year or later living in a cohabiting union, becoming pregnant did not increase the likelihood of transitioning to marriage relative to remaining cohabiting. These results suggest that after several years of living together without marrying or breaking-up if a couple becomes pregnant they are just as likely to remain cohabiting and not transition to marriage than if they didn’t become pregnant. Interestingly, pregnancy was not significantly associated with the likelihood of breaking up with one’s partner versus remaining cohabiting at any point in the cohabitation. This suggests that pregnancy is not necessarily “protective” against break-ups, as pregnant and non-pregnant women have similar odds of remaining cohabiting or breaking up with their partner across the duration of their union. Throughout cohabiting unions, however, being pregnant was associated with a lower likelihood of breaking-up rather than marrying one’s partner (OR = 0.32). Graphs of the predicted probability of marriage in Figure Three helps to illustrate the shifting association of pregnancy with the likelihood of transitioning to marriage across the duration of a cohabitation.

Table 3.

Multivariate Models of Cohabitation Stability

| Marriage | Break-up | Break-up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Still together is reference) | (Marriage is reference) | |||||

| b | OR | b | OR | b | OR | |

| Pregnant | 0.971*** (0.13) | 2.64 | −0.157 (0.15) | 0.85 | −1.128*** (0.20) | 0.32 |

| Pregnancy by cohabitation duration interactions | ||||||

| Pregnant X second year | −0.223 (0.25) | 0.80 | −0.276 (0.30) | 0.76 | −0.053 (0.37) | 0.95 |

| Pregnant X third year | −0.439 (0.30) | 0.55 | −0.057 (0.40) | 0.94 | 0.496 (0.52) | 1.64 |

| Pregnant X fourth year | −1.300** (0.41) | 0.27 | −0.418 (0.45) | 0.66 | 0.882 (0.64) | 2.42 |

| Pregnant X fifth year plus | −0.905* (0.42) | 0.40 | −0.300 (0.45) | 0.57 | 0.605 (0.65) | 1.83 |

| Cohabitation Duration (first year reference) | ||||||

| Second year | 0.353*** (0.09) | 1.42 | −0.168* (0.07) | 0.85 | −0.521*** (0.12) | 0.59 |

| Third year | 0.287** (0.10) | 1.33 | −0.348*** (0.08) | 0.71 | −0.634*** (0.12) | 0.53 |

| Fourth year | 0.305** (0.11) | 1.36 | −0.440*** (0.11) | 0.64 | −0.745*** (0.17) | 0.47 |

| Fifth year plus | 0.418** (0.16) | 1.52 | −0.316** (0.10) | 0.73 | −0.733*** (0.20) | 0.48 |

| Constant | −4.555*** (0.35) | 0.01 | −4.751*** (0.25) | 0.01 | −0.196 (0.43) | 0.82 |

Notes: results are weighted, adjust for clustering and stratification, and are based on multiply imputed data; standard errors are in parentheses; model controls for the Dubin-McFadden selection variables, race, family structure, education, age at union formation, and birth order;

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Figure 3.

Predicted probability of marriage across cohabitation duration by pregnancy status

Discussion

When a couple becomes pregnant the nature of their relationship changes. No longer are they merely romantic partners, they also become partners in child-bearing and -rearing. The current study suggests that the timing of when a pregnancy occurs in the life course of an individual or the duration a cohabiting relationship is associated with the trajectory and stability of that relationship.

Prior research indicates that there has been a decline in “shot-gun marriages” over time (England et al., 2012), while “shot-gun cohabitation” has become more common (Lichter, 2012), particularly as a first union form. Results of the current study contribute to this growing body of literature in several ways. First, while being pregnant is associated with an increase in the likelihood that a woman enters into either a first marriage or a cohabitation, at older ages the difference between pregnant and non-pregnant women in the likelihood of entering a first marriage directly or a cohabitation is reduced. Contrary to the proposed hypothesis, findings indicate that, controlling for the age-graded nature of union formation, pregnancy has a bigger impact on the likelihood of entering a coresidential union during adolescence and is reduced over time. This finding may reflect that at older ages individuals are more likely to enter a coresidential union (e.g. Manning, et al. 2014), and therefore a non-marital pregnancy doesn’t have the same “pull” that it does at earlier ages when coresidential unions are less common.

Findings from the current study also highlight that the association between pregnancy and the outcomes of cohabiting relationships varies across the duration of the union. Namely, pregnancy is more influential on the stability of cohabiting unions in the first few years of living together. After several years of living together without marrying or breaking-up if a couple gets pregnant they were just as likely to remain cohabiting and not transition to marriage than if they didn’t become pregnant. These results contribute to the literature on cohabiting families and highlight that childbearing “motivates” transitions out of cohabiting unions and into marriages in different ways depending on how long people have been living together. While events like pregnancy might create inertia within relationships that contributes to a “sliding” into more formalized unions (Stanley, Rhoades, & Markman, 2006), this inertia may be more palpable early within cohabiting unions. This also points to the distinct nature of longer-term cohabiters, who may not prioritize or be able to afford marriage, even when faced with a pregnancy.

Research on the meaning of cohabitation suggests that distinct pathways exist for cohabiters, in which cohabitation serves as a “precursor to marriage”, an “alternative to singlehood”, or an “alternative to marriage” (e.g. Manning & Smock, 2005; Casper & Bianchi, 2002). Therefore, when people become pregnant within a cohabiting union after years of living together this family building strategy may better reflect an “alternative to marriage” orientation, in which pregnancy does not lead to a formalizing of that union with marriage. While research suggests that individuals from low socioeconomic backgrounds may be particularly likely to engage in these types of long-term cohabiting strategies (e.g. Sassler & Miller, 2017) supplementary analyses (not shown) testing the interaction between education and pregnancy for cohabitation stability did not find evidence that the association between pregnancy and making transitions with cohabiting unions varied significantly by educational attainment. Future research should continue to explore whether and why the meaning of pregnancy and childbearing changes the longer people remain cohabiting together. Examining changes in behavior across the course of cohabiting relationships and the meaning that pregnancy holds for these families may help researchers to better understand the diversity of experiences among cohabiting families and how family formation decisions are made.

While the current study informs our understanding of the dynamic nature of pregnancy for cohabitation formation and stability, there are several limitations to note. First, the current study focuses on the impact of pregnancy on first union formation and first cohabiting unions. Therefore, this study does not capture the impact of pregnancy on the formation and stability of second or higher-order coresidential unions. While serial cohabitation has increased over time, the majority of women only cohabit once (about 75%;Cohen & Manning, 2010; Lichter, et al., 2010), and those who do engage in serial cohabitation are more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and are more likely to experience relationship instability (Lichter & Qian, 2008). Therefore, focusing only on the association between pregnancy and first union formation and first cohabitation captures the majority of cohabitation experiences. Further, an inclusion of higher-order cohabitations would likely over-represent women from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Qualitative research highlights that family building behaviors and relationship dynamics surrounding pregnancy are distinct for low-income women (e.g. Edin & Kefalas, 2005; Edin & Tach, 2012). Therefore, the current analyses is limited to first coresidential union formation to capture a more representative group of cohabitation experiences. Future research should examine how pregnancy impacts the formation and stability of higher-order unions. Second, only pregnancies which resulted in live births are considered in the current study. Pregnancies which do not result in a live birth, but rather end in abortion or miscarriage, may have a very different impact on romantic relationships and future research should continue to explore how different pregnancy experiences might impact union formation and stability in a dynamic fashion. Third, considerable research suggests that economic factors play a major role in fertility and union formation decisions (e.g. Wu & Pollard, 2000). Due to data limitations the current study lacks time-varying measures of income or employment which would be useful predictors in modeling union transitions and relies instead on educational attainment as a measure of socioeconomic status. Similarly, information on relationship quality surrounding the pregnancy was not available, which may be an important factor in explaining the linkage between pregnancy and union transitions. Finally, information was only available for one member of the romantic couple. Future research would benefit from including information on the characteristics of both members of the couple to examine their unique contribution to pregnancy and cohabitation experiences.

Prior research has operated under the assumption that becoming pregnant will influence the likelihood of marriage or union dissolution in similar ways regardless of when in the union such childbearing events occur. These results suggest that that is an important oversight. We know that cohabiting unions are often short-lived states; however, future research should not treat the experiences within these unions as constant and should continue to be sensitive to the time-varying nature of these experiences. Results suggest that pregnancy has a stronger “pull” into first marital or cohabiting unions for single teenage women, and that over time, as entrance into first coresidential unions become more normative, these differences are reduced. Furthermore, the positive association between pregnancy and marriage within cohabiting unions shifts across the duration of that cohabitation. The longer that a cohabiting couple remains together in a cohabiting union, the less likely they are to marry when they become pregnant. These findings highlight that it is important to consider how pregnancy impacts relationship transitions in a dynamic manner; that pregnancy can mean different things for relationships across the life course of individuals and the duration of cohabitations.

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Health and Human Development to the Population Research Institute at The Pennsylvania State University for Population Research Infrastructure (R24 HD41025) and Family Demography Training (T-32HD007514). This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgement is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisel for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health Data Files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

References

- Bourguignon F, Fournier M, & Gurgand M (2007). Selection bias corrections based on the multinomial logit model: Monte Carlo comparisons. Journal of Economic Surveys, 21(1), 174–205. [Google Scholar]

- Brien MJ, Lillard LA, &Waite LJ (1999). Interrelated family-building behaviors: Cohabitation, marriage, and nonmarital conception. Demography, 36(4), 535–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL (2000). Union transitions among cohabitors: The significance of relationship assessments and expectations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(3), 833–846. [Google Scholar]

- Budig MJ (2003). Are women’s employment and fertility histories interdependent? An examination of causal order using event history analysis. Social Science Research, 32(3), 376–401. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M, McLanahan S England P (2004). Union formation in fragile families. Demography, 41(2), 237–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casper LM, & Bianchi SM (2002). Change and continuity in the American family. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Child Trends Databank. (2015). Teen births. Retrieved from http://www.childtrends.org/?indicators=teen-births.

- Cohen J, & Manning W (2010). The Relationship Context of Premarital Serial Cohabitation. Social Science Research, 39(5), 766–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss BD, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, & Markman HJ (2010). The effect of transition to parenthood on relationship quality: An eight-year prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(3), 601–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubin JA, & McFadden DL (1984). An econometric analysis of residential electric appliance holdings and consumption. Econometrica, 47,153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, & Kefalas M (2005). Promises I can keep: why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, & Tach L (2012). Becoming a parent: The social contexts of fertility during young adulthood In Early adulthood in a family context (pp. 185–207). Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH Jr. (1994). Time, human agency, and social change: Perspectives on the life course. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57(1), 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Johnson MK, & Crosnoe R (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory In Handbook of the life course (pp. 3–19). Springer, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- England P, Fitzgibbons E, & Wu LL (2012). Premarital conceptions, postconception (“shotgun”) marriages, and premarital first births: Education gradients in U.S. cohorts of white and black women born 1925-1959. Demographic Research, 27, 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo KB (2006). The relationship between life course events and union formation. Social Science Research, 35, 384–408. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo KB, & Hayford SR (2012). Unintended fertility and the stability of coresidential relationships. Social Science Research, 41(5), 1138–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Halpern CT, Whitsel E, Hussey J, Tabor J, Entzel P, & Udry JR (2009). The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health: Research Design. Retrieved from: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- Hatch A (2015). Saying “I don’t” to matrimony: An investigation of why long-term heterosexual cohabitors choose not to marry. Journal of Family Issues, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kreider RM, & Ellis R (2011) Number, timing, and duration of marriages and divorces: 2009. US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Le B, & Agnew CR (2003). Commitment and its theorized determinants: A meta-analysis of the investment model. Personal Relationships, 10, 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT (2012). Childbearing among cohabiting women: Race, pregnancy, and union transitions In Booth A, Amato P, McHale S, & VanHook J. (Eds.), Early Adulthood in a Family Context (pp 209–219). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Sassler S, & Turner RN (2014). Cohabitation, post-conception unions, and the rise in nonmarital fertility. Social Science Research, 47, 134–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, & Quian Z (2008) Serial cohabitation and the marital life course, Journal of Marriage and Family, 70(4), 861–878. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Turner RN, & Sassler S (2010). National estimates of the rise in serial cohabitation. Social Science Research, 39(5), 754–765. [Google Scholar]

- Liefbroer AC (1999). From youth to adulthood: Understanding changing patterns of family formation from a life course perspective, In van Wissen LJG & Dykstra PA (Eds.), Population Issues (pp. 53–85). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Manning W (2004). Children and the stability of cohabiting couples. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(3), 674–689. [Google Scholar]

- Manning W, Brown SL, & Payne K (2014). Two decades of stability and change in the age at first union formation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(2), 247–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, & Smock PJ (2005). Measuring and modeling cohabitation: New perspectives from qualitative data. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(4), 989–1002. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, & Beck AN (2010). Parental relationships in fragile families. The Future of Children, 20(2), 17–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollburn S (2010). Predictors and consequences of adolescents’ norms against teenage pregnancy. The Sociological Quarterly, 51(2), 303–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musick K (2002). Planned and unplanned childbearing among unmarried women. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(4), 915–929. [Google Scholar]

- Musick K, & Michelmore K (2015). Change in the stability of marital and cohabiting unions following the birth of a child. Demography, 52(5), 1463–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne C, Manning WD, & Smock PJ (2007). Married and cohabiting parents’ relationship stability: A focus on race and ethnicity. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(5), 1345–66. [Google Scholar]

- Parker E (2018) Plans for marriage among first-time cohabitors: Gender, transitions, and tempo. Paper presented at meeting of the Population Association of America, Denver, CO. [Google Scholar]

- Rackin H, & Gibson-Davis CM (2012). The role of pre- and postconception relationships for first-time parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(3), 526–39. [Google Scholar]

- Regan PC (2008). The Mating Game: A Primer on Love, Sex, and Marriage (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rendall MS, Clarke L, Peters HE, Ranjit N, & Verropoulou G (1999). Incomplete reporting of men’s fertility in the United States and Britain: A research note. Demography, 36(1), 135–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, & Buunk BP (1993). Commitment processes in close relationships: An interdependence analysis. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 10, 175–204. [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S & Miller A (2017) Cohabitation nation: Gender, class, and the remaking of relationships. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA Jr. (2004). Age structuring and the rhythm of the life course In Mortimer JT & Shanahan MJ (Eds.), Handbook of the Life Course (pp. 81–98). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, & Willett JB (2003). Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Rhoades GK, & Markman HJ (2006). Sliding versus deciding: Inertia and the premarital cohabitation effect. Family Relations, 55(4), 499–509. [Google Scholar]

- Su JH, Dunifon R, & Sassler S (2015). Better for baby? The retreat from mid-pregnancy marriage and implications for parenting and child well-being. Demography, 52(4), 1167–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsen ML (2017). The adolescent family environment and cohabitation across the transition to adulthood. Social Science Research, 64, 249–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura SJ (2009). Changing patterns of nonmarital childbearing in the United States, National Center on Health Statistics data brief, no 18 Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson H, & Huntington A (2005). Deviant (m)others: The construction of teenage motherhood in contemporary discourse. Journal of Social Policy, 35(1), 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wu LL, & Musick K (2008). Stability of marital and cohabiting unions following a first birth. Population Research and Policy Review, 27(6), 713–727. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, & Pollard MS (2000). Economic circumstances and the stability of nonmarital cohabitation. Journal of Family Issues, 21(3), 303–328. [Google Scholar]