Abstract

Objective

A ‘precision’ approach to type 2 diabetes therapy would aim to target treatment according to patient characteristics. We examined if measures of insulin resistance and secretion were associated with glycemic response to DPP4-inhibitor therapy.

Research Design and Methods

We evaluated whether markers of insulin resistance and insulin secretion were associated with 6 month glycemic response in a prospective study of non-insulin treated participants starting DPP4-inhibitor therapy (PRIBA, n=254), with replication for routinely available markers in UK electronic healthcare records (CPRD, n=23,001). In CPRD we evaluated associations between baseline markers and 3 year durability of response. To test the specificity of findings we repeated analyses for GLP-1 receptor agonists (PRIBA n=339, CPRD n=4,464).

Results

In PRIBA markers of higher insulin resistance (higher fasting C-peptide (p=0.03), HOMA2 insulin resistance (p=0.01) and triglycerides (p<0.01)) were associated with reduced 6 month HbA1c response to DPP4 inhibitors. In CPRD higher triglycerides and BMI were associated with reduced HbA1c response (both p<0.01). A subgroup defined by obesity (BMI≥30kg/m2) and high triglycerides (≥2.3mmol/L) had reduced 6 month response in both datasets (PRIBA HbA1c reduction 5.3[95%CI 1.8,8.6]mmol/mol (0.5%) (obese, high triglycerides) vs 11.3[8.4,14.1] mmol/mol (1.0%) (non-obese, normal triglycerides), p=0.01. In CPRD the obese, high triglycerides subgroup also had less durable response (hazard ratio 1.28[1.16,1.41], p<0.001). There was no association between markers of insulin resistance and response to GLP-1 receptor agonists.

Conclusions

Markers of higher insulin resistance are consistently associated with reduced glycemic response to DPP4-inhibitors. This finding provides a starting point for the application of a precision diabetes approach to DPP4-inhibitor therapy.

PRIBA ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01503112

Type 2 diabetes is a heterogeneous condition characterised by varying degrees of reduced beta cell function and higher levels of insulin resistance. Most of the 400 million patients worldwide will at some point require glucose lowering medication (1). Major international treatment guidelines recommend at least 4 oral treatment options after initial metformin has failed to achieve control, with choice between these informed predominantly by method of administration, overall side effect profile and cost (2–4).

Individual response to glucose lowering therapies in type 2 diabetes varies greatly. Identification of clinical phenotypic features or biomarkers robustly associated with glycemic response or other potentially beneficial effects for example reduced weight gain, or side effects for each therapy, may allow treatment of patients with the agent that is most likely to be effective for them, an approach known as ‘precision’ or ‘stratified’ medicine (5; 6). While much research has focused on identifying genetic or novel biomarker predictors of response, precision diabetes is most likely to be cost effective and have clinical impact using simple inexpensive biomarkers or routinely available clinical phenotypic features (7; 8).

DPP4 inhibitors are common (20% of U.S. and 40% of UK second-line prescriptions in 2016) (9) (J.M Dennis, B.M Shields, personal communication), well-tolerated (10), oral therapy options recommended in all clinical guidelines (2–4). Beyond baseline HbA1c and fasting glucose it is unclear if other factors are associated with glycemic response to DPP4 inhibitors (11; 12). A major mechanism of action of DPP4 inhibitors is potentiation of beta cell insulin secretion. We aimed to establish if measures of insulin secretion and insulin resistance were associated with short-term glycemic response and long-term durability of response in patients with type 2 diabetes starting DPP4 inhibitor therapy.

Research Design and Methods

We assessed whether clinical features and biomarkers associated with insulin secretion and insulin resistance were predictive of short-term 6 month glycemic response in analysis of a prospective study of patients starting DPP4 inhibitor therapy as part of routine care (PRIBA). To validate our findings we tested the consistency of associations between routinely recorded factors associated with response in PRIBA in a retrospective analysis of a much larger group of patients from UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), evaluating both 6 month glycemic response and long term durability of response to 3 years.

Study setting and assessment

PRIBA prospective study

The PRIBA study was designed to test the hypothesis that those who have low insulin secretion, as measured by C-peptide, will have poor glycemic response to incretin based treatments (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01503112), with associations between glycemic response and other clinical features, islet autoantibodies and Homeostasis Model Assessment (HOMA) 2 estimates of beta cell function and insulin sensitivity evaluated in pre-specified secondary analysis. 305 participants due to start DPP4 inhibitor therapy as part of their usual care were recruited from primary and secondary care across 17 National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) clinical research network centres in the UK from April 2011 to October 2013 as previously described (13).

At baseline (immediately prior to starting therapy) we measured HbA1c, fasting glucose, clinical markers of insulin resistance and insulin secretion (fasting C-peptide and post meal urine C-peptide Creatinine ratio (UCPCR) (14; 15); BMI, triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol (HDL-c) (16); sex-hormone binding globulin (SHBG), GAD and IA2 islet autoantibodies) and other clinical characteristics (age at therapy, sex, duration of diabetes, eGFR, ethnicity, LDL-cholesterol (LDL-c), number of diabetes therapies). We calculated HOMA-estimates of beta-cell function (HOMA2%B) and insulin resistance (HOMA2 IR) from fasting glucose and C-peptide measures using the HOMA2 calculator available from http://www.dtu.ox.ac.uk/homacalculator/ (17). Laboratory analysis was conducted as previously reported (13). Participants were included in the analysis if they were not insulin treated and had at least 3 months follow up with >75% adherence to therapy and limited co-treatment change (see study profile supplementary figure 1a). Ethics approval was granted by the South West National Research Ethics committee, and all participants gave written informed consent.

Retrospective analysis of UK primary care patients (CPRD database)

CPRD is the world’s largest longitudinal database of anonymised primary care electronic health records (18). We included 23,001 non-insulin treated patients with type 2 diabetes with prescription records of starting a DPP4 inhibitor for the first time from June 2007 to September 2016, and followed them up whilst they remained on DPP4 inhibitor therapy without the addition or cessation of any other anti-hyperglycemic medication (see study profile supplementary figure 1b). We extracted baseline routine clinical characteristics (age at therapy, duration of diabetes, sex and BMI) and biomarkers (HbA1c, triglycerides, HDL-c, LDL-c and eGFR), with baseline defined as the most recent record in the 3 months prior to the drug start date. Ethics approval was granted by the CPRD Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (ISAC 13_177R).

Analysis

Outcome definitions

Short-term glycemic response (PRIBA & CPRD)

The primary outcome was the absolute change from baseline in HbA1c 6 months after starting therapy, adjusting for baseline HbA1c. Where a 6 month HbA1c was not available or eligible in the PRIBA study (see supplementary figure 1a) we used a 3 month HbA1c measure, as previously described (13). In CPRD a valid 6 month HbA1c was defined as the closest HbA1c to 6 months after the drug start date +/-3 months for patients on unchanged anti-hyperglycemic therapy.

Durability of glycemic response (CPRD)

In CPRD where long-term follow-up data were available we assessed durability of response as the time to glycemic failure over 3 years in a complete case analysis of patients with baseline HbA1c between 53-97 mmol/mol (7-11%) and at least 3 months on DPP4 inhibitor therapy (n=15,616). Glycemic failure was defined as a) two consecutive HbA1c’s greater than 69 mmol/mol (8.5%) b) a single HbA1c greater than 69 mmol/mol (8.5%) followed by the addition of another anti-hyperglycemic therapy. To examine the sensitivity of results to this definition we repeated the analysis using HbA1c thresholds of a) 53mmol/mol (7.5%) and b) the baseline HbA1c level specific to each individual patient.

Statistical analysis

Short-term response (PRIBA & CPRD)

We examined associations between each standardised marker of insulin resistance and insulin secretion and 6 month HbA1c response in a series of linear regression models adjusted for baseline HbA1c and, in PRIBA, co-therapy change (11; 18). Non-normally distributed variables were log-transformed. We conducted a complete case analysis for each marker, including all patients with valid data even if they had missing data for other markers. To evaluate model fit we examined normality of residuals and linearity of associations for continuous variables. In both datasets we tested the independence of initial associations for each marker of insulin resistance and insulin secretion with 6 month response in further multivariable analysis, controlling for baseline HbA1c and other routinely recorded characteristics: age at therapy, duration of diabetes, sex, eGFR, LDL-c, ethnicity (CPRD only: white, non-white, missing) and co-therapy change (PRIBA only, CPRD patients all on unchanged therapy).

To further assess the robustness of findings we repeated the baseline adjusted analysis of 6 month response for males and females separately in both datasets, and in PRIBA with additional adjustment for fasting glucose. In CPRD we repeated the baseline adjusted analysis using 12 month response as the outcome in a distinct cohort of patients with 12 month (closest +/-3 months as for definition of 6 month response) HbA1c record (n=16,166).

Subgroup analysis of short-term response (PRIBA & CPRD)

Based on the initial results we defined 3 patient subgroups by standard clinical cut-offs for obesity (BMI>=30 kg/m2) and high triglycerides (>=2.3mmol/L) (19) - Group A: non-obese and normal triglycerides, Group B: non-obese OR normal triglycerides, Group C: obese and high triglycerides. We estimated the mean 6 month HbA1c response for each subgroup using linear regression models adjusted for baseline HbA1c and, in PRIBA, co-therapy change. We standardised baseline HbA1c to the mean PRIBA baseline level of 74mmol/mol (8.9%) for all subgroups in both datasets.

Durability of response (CPRD)

For 3 subgroups defined by the same BMI and triglyceride thresholds we compared mean durability in response to three years after starting therapy using a flexible parametric time to failure survival model. We included all patients with at least 3 months on therapy after starting a DPP4 inhibitor with valid baseline records of all covariates (baseline HbA1c, age at therapy, duration of diabetes, sex and eGFR). The use of flexible parametric models allowed prediction of the probability of therapy failure over three years as well as hazard ratios consistent with Cox proportional hazards regression (20). We tested continuous variables for non-linearity, and evaluated proportional hazards assumptions using Schoenfeld residuals. To estimate the probability of therapy failure (the inverse of survival) for each subgroup a predicted survival curve was calculated for each patient in the dataset before the individual survival curves for all patients within a subgroup were averaged (21). Each curve was standardised to the mean CPRD values of other clinical covariates (baseline HbA1c = 72mmol/mol (8.7%), age at therapy = 64 years, duration of diabetes = 8 years, eGFR = 82 ml/min/1.73m2). Point estimates for the failure probability at 3 years by subgroup were calculated using the same approach.

Replication analysis with GLP-1 receptor agonists (PRIBA and CPRD)

To test the specificity of findings for DPP4 inhibitors we repeated the analyses of short-term response and durability of response for non-insulin treated subjects starting GLP-1 receptor agonists, the other glucose-lowering drug evaluated in PRIBA (PRIBA n=339, CPRD n=4,464). We have previously reported the PRIBA primary analysis of predictors of glycemic response for the full PRIBA GLP-1 receptor agonist cohort, which included an additional 209 insulin treated participants (14). All data extraction and analysis were conducted using Stata v14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Patient characteristics & response to DPP4 inhibitor therapy

Baseline characteristics and biomarker measures were similar for subjects starting DPP4 inhibitors in both datasets (Table 1). In both cohorts the majority of patients started Sitagliptin. 254 patients were included in PRIBA and 23,001 (for analysis of 6 month glycemic response) in CPRD (for study profiles see supplementary figure 1). Mean (standard deviation (SD)) 6 month HbA1c change was -8.3 (13.5) mmol/mol (-0.7% (1.2%)) in PRIBA and -7.6 (15.1) mmol/mol (-0.7% (1.4%)) in CPRD.

Table 1. Subject baseline characteristics.

| PRIBA (n=254) | CPRD (n=23,001) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Characteristics mean (SD) unless stated |

|||

| Baseline HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 74 (12) | 72 (15) | |

| Baseline HbA1c (%) | 8.9 (1.1) | 8.7 (1.3) | |

| Age at therapy start (years) | 63 (10) | 64 (11) | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 54 (10) | 56 (10) | |

| Male sex (%) | 63% | 61% | |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | 9 (6) | 8 (5) | |

| BMI - median (IQR); mean(SD) | 32 (29-37); 33 (6) | 32 (28-36); 33 (6) | |

| Ethnicity (%) | |||

| White | 97% | 45% | |

| Non-White | 3% | 6% | |

| Missing | 0% | 49% | |

|

Biomarkers median (IQR); mean (SD) unless stated *=log-transformed |

|||

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.7 (1.2-2.4); 1.8 (0.9)* | 1.8 (1.3-2.6); 1.9 (1.0)* | |

| HDL-c (mmol/L) | 1.1 (0.9-1.3); 1.1 (0.3)* | 1.1 (0.9-1.3); 1.1 (0.3)* | |

| LDL-c (mmol/L) | 1.9 (1.5-2.3); 1.9 (0.8)* | 2.1 (1.6-2.6); 2.0 (0.8)* | |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | 27 (19-41); 27 (16)* | NA | |

| Fasting C-peptide (pmol/L) | 1150 (820-1460); 1090 (480)* | NA | |

| HOMA2-%B | 54 (37-73); 51 (27)* | NA | |

| HOMA2 IR | 3.1 (2.3-4.2); 3.1 (1.5)* | NA | |

| UCPCR nmol/mmol | 3.4 (2.0-5.0); 3.0 (2.3)* | NA | |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.3m2) | 85 (70-98); 85 (24) | 82 (66-97); 82 (23) | |

| GAD or IA2 positive (%) | 3% | NA | |

| Therapy | |||

| Number of concomitant therapies at therapy start (% of total) |

|||

| 0 | 3% | 6% | |

| 1 | 35% | 51% | |

| 2 | 57% | 42% | |

| 3+ | 5% | 2% | |

| DPP4 type (% of total) | |||

| Sitagliptin | 87% | 72% | |

| Alogliptin | 0% | 2% | |

| Linagliptin | 4% | 10% | |

| Saxagliptin | 6% | 12% | |

| Vildagliptin | 2% | 4% | |

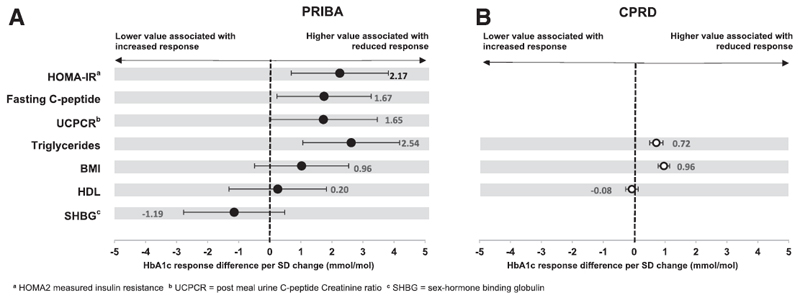

Higher baseline fasting C-peptide and HOMA measured insulin resistance are associated with reduced glycemic response to DPP4 inhibitors

In the PRIBA cohort mean HbA1c response was reduced by 1.67 mmol/mol for every 1 SD higher baseline fasting C-peptide (standardised β 1.67 [95% CI 0.17 to 3.17] mmol/mol/SD, p=0.03) (Figure 1). We observed the same direction and similar size of effect for UCPCR (response reduction per SD higher 1.65 [95% CI -0.07 to 3.37] mmol/mol, p=0.06). Higher baseline HOMA measured insulin resistance (HOMA2-IR) was also associated with reduced response (response reduction per SD higher: 2.17 [95% CI 0.62 to 3.72], mmol/mol, p=0.01), but there was no evidence of an association between beta-cell function (HOMA2-%B) and response (response reduction per SD higher 0.16 [95% CI -1.49 to 1.81] mmol/mol, p=0.85). Islet autoantibody prevalence was low (2.8% GAD or IA2 positive; response reduction for presence of autoantibodies: 5.6 [95% CI -3.6, 14.7] mmol/mol, p=0.23).

Figure 1. DPP4 inhibitors - associations between markers of insulin resistance and HbA1c response at 6 months.

Circles (black = PRIBA, white = CPRD) denote the mean HbA1c change (mmol/mol) at 6 months per 1 standard deviation (SD) higher baseline value of each marker. Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals.

Other markers of insulin resistance are consistently associated with glycemic response to DPP4 inhibitors in PRIBA and CPRD

In PRIBA higher triglycerides was associated with reduced glycemic response (response reduction per SD increase 2.54 [95% CI 0.99 to 4.08] mmol/mol, p<0.001), with a consistent direction of association for higher BMI (response reduction per higher BMI 0.96 [95% CI -0.54 to 2.46] mmol/mol, p=0.21) and lower SHBG (response reduction per SD higher SHBG -1.19 [95% CI -2.81 to 0.42] mmol/mol, p=0.15) (Figure 1, supplementary table 1). In CPRD higher triglycerides and BMI were associated with reduced HbA1c response (Figure 1, supplementary table 1). HDL-c was not associated with response in either dataset (p=0.81 in PRIBA, p=0.46 in CPRD).

Markers of insulin resistance are associated with glycemic response to DPP4 inhibitors independently of other routine clinical characteristics

Results were consistent when a) stratifying by sex (supplementary table 1), b) controlling for baseline HbA1c, age at therapy, sex, duration of diabetes, eGFR, LDL-c, ethnicity (CPRD only) and co-therapy change (PRIBA only) in multivariable analysis of each dataset (supplementary table 2), c) in PRIBA controlling for fasting glucose (supplementary table 3) and d) in CPRD with 12 month HbA1c response as the outcome (supplementary table 4).

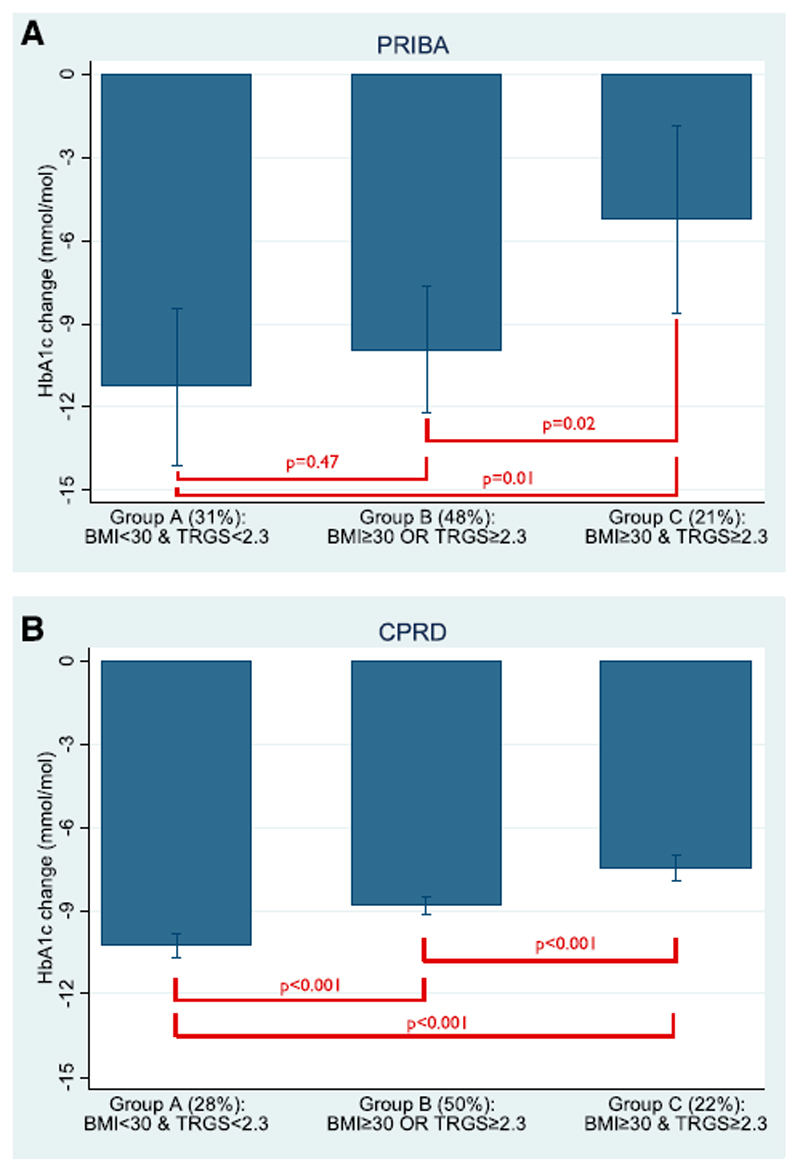

Standard clinical criteria of obesity and high triglycerides can identify patients likely to have markedly reduced glycemic response to DPP4 inhibitors

Higher triglycerides was associated with reduced glycemic response independently of BMI in both datasets, and higher BMI was associated with reduced response independently of triglycerides in CPRD (supplementary table 5). To examine the potential clinical implication of this finding we compared mean baseline HbA1c adjusted response in 3 patient subgroups defined by standard clinical cut-offs for obesity (BMI>=30 kg/m2) and high triglycerides (>=2.3mmol/L) - Subgroup A: non-obese and normal triglycerides, Subgroup B: non-obese OR normal triglycerides, Subgroup C: obese and high triglycerides).

In PRIBA we found mean 6 month baseline HbA1c standardised glycemic response was halved for the obese and high triglycerides subgroup (Subgroup C -5.2 [95% CI -1.8 to -8.6] mmol/mol (-0.5% [95% CI -0.2;-0.8])) compared to the non-obese and normal triglycerides subgroup (Subgroup A -11.3 [95% CI -8.4 to -14.1] mmol/mol (-1.0% [95% CI -0.8;-1.3])) and was significantly reduced compared to intermediate Subgroup B (-9.9 [95% CI -7.6 to -12.2] mmol/mol (-0.9% [95% CI -0.7;-1.1])) (Figure 2a). Direction of effect was replicated in CPRD, albeit with smaller differences in mean response between subgroups (Subgroup A mean baseline adjusted HbA1c response -10.3 [95% CI -9.8 to -10.7] mmol/mol (-0.9% [95% CI -0.9;-1.0]), Subgroup B -8.8 [95% CI -8.5 to -9.1] mmol/mol (-0.8% [95% CI -0.8;-0.8]), Subgroup C -7.5 [95% CI -7.0 to -7.9] mmol/mol (-0.7% [95% CI -0.6;-0.7]), Figure 2b).

Figure 2. DPP4 inhibitors - predicted mean absolute HbA1c change from baseline at 6 months in a) PRIBA b) CPRD across subgroups defined by the presence or absence of obesity (BMI>=30 kg/m2) and high triglycerides (TRGs >=2.3mmol/L) - Subgroup A: non-obese and normal triglycerides, Subgroup B: non-obese OR normal triglycerides, Subgroup C: obese and high triglycerides.

Baseline HbA1c is standardised to the mean PRIBA baseline level of 74mmol/mol (8.9%) for all subgroups. Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals.

Obesity and high triglycerides are associated with less durable glycemic response to DPP4 inhibitors over 3 years

15,616 patients were followed up in this analysis for a mean time of 1.5 years. Over the 3 year study period 3,514 (23%) patients had glycemic failure (confirmed HbA1c ≥ 69 mmol/mol (8.5%). We observed an increased relative risk of glycemic failure, reflecting a less durable response) in the same obesity and high triglycerides defined subgroups, standardising for other clinical characteristics (hazard ratios for glycemic failure: Subgroup C obese AND high triglycerides versus Subgroup A non-obese and normal triglycerides 1.28 [95% CI 1.16-1.41], p<0.001; Subgroup B obese OR high triglycerides versus Subgroup A 1.17 [95% CI 1.08-1.27], p<0.001; Subgroup C versus Subgroup B 1.09 [95% CI 1.01-1.18], p=0.04; supplementary table 6). Consistent relative differences between subgroups were observed at HbA1c failure thresholds of 7.5% and the baseline HbA1c specific to each individual patient (supplementary table 7-8). These results translated into significant differences between subgroups in the absolute probability of glycemic failure at three years (Subgroup C: obese AND high triglycerides 39% [95% CI 37-42%]; Subgroup B: obese OR high triglycerides 37% [95% CI 35-38%]; Subgroup A: non-obese and normal triglycerides 32% [95% CI 31-34 %] supplementary figure 2).

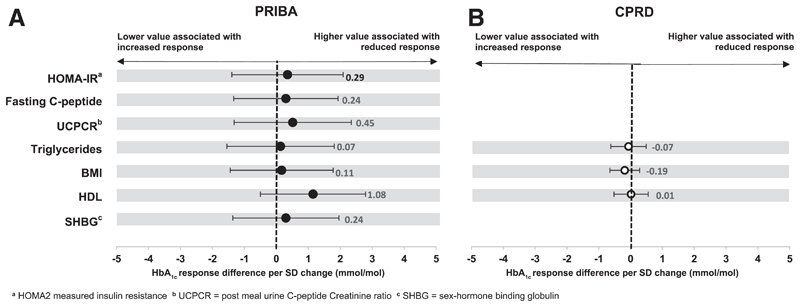

There is no evidence of an association between markers of insulin resistance and glycemic response to GLP-1 receptor agonists

We found no evidence of an association between any marker of insulin resistance and 6 month glycemic response to GLP-1 receptor agonists in PRIBA (n=339) or CPRD (n=4,464) on continuous analysis (Figure 3, supplementary tables 8-9). There was also no evidence for a difference in response to GLP-1 receptor agonists across the obesity and triglyceride defined subgroups (all subgroup comparisons p>0.40; supplementary table 10, supplementary figure 3), although there were few subjects in the non-obese, normal triglyceride subgroup starting GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy in both datasets (PRIBA 2%, CPRD 5%). Similarly, in CPRD we found no evidence of an association between durability of glycemic response and BMI (HR per unit increase 1.01 (95% CI 1.00-1.02, p=0.29) or triglyceride levels (HR per unit increase 0.99 (95% CI 0.95-1.04, p=0.80) (supplementary table 11), or of a difference in durability of response across obesity and triglyceride defined subgroups (supplementary table 12, supplementary figure 4).

Figure 3. GLP-1 receptor agonists - associations between markers of insulin resistance and HbA1c response at 6 months.

Circles (black = PRIBA, white = CPRD) denote the mean HbA1c change (mmol/mol) at 6 months per 1 standard deviation (SD) higher baseline value of each marker. Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals.

Conclusions

Our results show that markers of higher insulin resistance are consistently associated with reduced glycemic response to DPP4 inhibitor therapy. In our UK-representative cohort 22% of patients were obese with high triglycerides (≥2.3mmol/L) and these patients had both markedly reduced short-term glycemic response and shorter durability of response on DPP4 inhibitor treatment. With GLP-1 receptor agonists we found no evidence of an association between markers of insulin response and either 6 month glycemic response or durability of response to 3 years. Findings were robustly demonstrated in a prospective study and validated in real-world data and provide a starting point for the application of a precision diabetes approach with DPP4 inhibitor therapy.

Strengths of this study include that we have shown consistent findings across several clinical features and markers of insulin resistance in a prospective study and large dataset of electronic healthcare records. We have shown findings are robust with adjustment for baseline HbA1c (11; 22), and potential confounders, and by definition of glycemic response, with similar associations for short term (6 and 12 month) and long term (3 year durability) glycemic outcomes. Our study is the first to identify characteristics associated with durability of response to DPP4 inhibitor therapy, an area where evidence is limited (23).

Limitations of this study include that we were only able to partially replicate our results from the PRIBA study cohort, as measures such as C-peptide were not available in our replication dataset. Our effect size for triglycerides is notably smaller in our replication dataset. It is possible this relates to differences in triglyceride measurement (we were unable to confirm if measured triglycerides were fasted in these real-world data) or to increased error in electronic healthcare records in comparison to the prospective study (24), or to the effect of statistical chance in the smaller dataset. The only long-term follow-up data we had to evaluate durability of glycemic response was from the routine primary care dataset CPRD, further evaluation in a trial setting with greater follow-up than PRIBA would be of considerable interest. An additional important limitation is that this study has examined response to only two of the available therapies. Evidence is limited for other therapies, although a previous study found no evidence of a relationship between clinical insulin resistance or dyslipidaemia markers and glycemic response with the SGLT-2 inhibitor Dapaglifozin (25). High BMI and triglycerides have both been shown to be associated with modest increases in the rate of diabetes progression (26). While this is unlikely to be relevant to our finding for 6 month glycemic response this could influence our findings for treatment durability, and replication looking at other comparison therapies is therefore particularly important in this context. While we have only examined relatively crude measures of insulin resistance, for clinical practice we consider it very unlikely that more complex measures would ever be feasible (27).

Existing studies of the association between insulin resistance and short-term glycemic response to DPP4 inhibitors have not shown consistent findings and are constrained by methodological and reporting limitations, as recently reviewed by Bihan and colleagues (11). Meta-regression of study level data have suggested reduced glycemic response in patients with higher BMI in one study (28), but no relationship in another analysis (29). These studies should be interpreted with some caution due to risk of ecological bias (30; 31). A number of individual clinical trials of DPP4 inhibitors have commented on consistency of glucose response across subgroups defined by baseline BMI or insulin resistance, reduced glycemic response with high HOMA measured insulin resistance was reported in 2 of 7 studies, and reduced response with high BMI in 6 of 36 studies, as reviewed in Bihan et al (11). No studies reported an opposite direction of effect. These reports are very limited, with the vast majority providing no statistical comparison or details of what analysis was undertaken. An important issue for analysis of this nature is accounting for the influence of baseline HbA1c, the strongest predictor of glycemic response, which may confound true associations, especially as baseline HbA1c and insulin resistance are positively correlated (22; 32; 33). There are limited data examining the relationship between triglycerides and response to DPP4 inhibitors, however one study stratified patients by baseline triglycerides (</>1.7mmol/l) and found the odds of achieving an HbA1c target of 53mmol/mol (7%) were doubled in the low triglyceride subgroup (OR 2.2 [95% CI 1.0-4.7], p=0.04) (34).

While it is plausible our finding of reduced glycemic response in those with high BMI or high triglycerides directly relates to insulin resistance through reduced effect of drug potentiated insulin secretion, this effect is not apparent in other drugs with effects on insulin secretion, for example there is no relationship between obesity and response to sulfonylurea therapy or GLP-1 receptor agonists (13; 35). An alternative explanation would be a direct effect of lipotoxicity, or indirect associations with other (unmeasured) factors important to DPP4 inhibitor response. A direct mechanism for lipotoxicity in reducing response to incretin based therapy has been previously suggested, with expression of GLP1 receptors diminished in islets exposed to elevated fatty acid levels in animal models, and beta cell response to GLP1 restored following fatty acid reduction with fibrate pharmacotherapy, however this mechanism would not explain the lack of an association between these features and GLP-1 Receptor Agonist response(36). It has also been shown that GLP-1 response is blunted in obese insulin resistant patients with high liver fat and also blunted in patients with high fasting triglycerides (37; 38), therefore impaired GLP-1 secretion in obese insulin resistant individuals represents a potential indirect mechanism that could also account for the lack of a similar relationship for injected GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy. While the lack of association for HDL-c may be considered unexpected, we note HDL-c has a much weaker relationship with insulin resistance than either triglycerides or fasting insulin/C-peptide, which may explain this finding (16).

Our findings have potential implications for clinical practice, as both BMI and triglycerides are routinely available at no additional cost. Stratification of treatment based on these criteria may therefore be cost effective even with the more modest differences in treatment effect seen in our replication cohort. Although our own and previous research suggests these findings may be specific to DPP4 inhibitors further work examining the relationship between these, and other, factors and response to comparator drugs is needed. Our study design, emphasising the importance of replication across datasets, provides an exemplar for such future analyses. In addition while simple categorisation by subgroup may provide a starting point for prediction of therapy response in type 2 diabetes, we anticipate a more sophisticated precision diabetes approach combining features into a multivariable response calculator will have greatest clinical utility, and this this is an important area for future research (7; 39).

In conclusion, our study shows simple markers of higher insulin resistance are consistently associated with reduced glycemic response to DPP4 inhibitor therapy. This finding was robustly demonstrated in a prospective study and validated in real-world data and provide a starting point for the application of a precision diabetes approach to DPP4 inhibitor therapy in type 2 diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank staff of the National Institute for Health Research Exeter Clinical Research Facility and National Institute for Health Research Diabetes Research Network for assistance with conducting the study. The authors thank the members of the Predicting Response to Incretin Based Agents (PRIBA) study group (Supplementary Data) and all cohort participants.

Funding

The PRIBA study was funded by A National Institute for Health Research (U.K.) Doctoral Research Fellowship (DRF-2010-03-72, Jones) and supported by the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network. The MASTERMIND consortium is supported by the Medical Research Council (UK) (MR/N00633X/1). AGJ is supported by an NIHR Clinician Scientist award. TJM is a National Institute for Health Research CSO Clinical Senior Lecturer. ATH and RHH are NIHR Senior Investigators. ERP is Wellcome Trust New Investigator (102820/Z/13/Z), ATH is a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator. ATH, AVH, BAK and BMS are supported by the NIHR Exeter Clinical Research Facility. NS acknowledges support by Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking under grant agreement no. 115372, the resources of which comprise financial contribution from the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) and EFPIA companies' in kind contribution. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The funders had no role in any part of the study or in any decision about publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement

WEH declares a grant from Quintiles, ERP declares personal fees from Lily, Novo Nordisk, and Astra Zeneca. NS declares personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Janssen and a grant from Astra Zeneca. RHH declares research funding from Bayer, Astra Zeneca, MSD and honoraria from Amgen, Bayer, Elcelyx, Jannsen, Intarcia, MSD, Novartis, Novo Nordisk and Servier. For all other authors there are no other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Author Contributions

Contributors: AGJ and JMD designed the study. AGJ, AVH, BAK and TJM researched the data (PRIBA study), BMS, LRR and MNW extracted the CPRD data. JMD, BMS and AGJ analysed the data with assistance from WEH. JMD and AGJ drafted the article. ATH, ERP, NS, WEH, and RHH discussed and contributed to study design, provided support for the analysis and interpretation of results. All authors critically revised the article and approved the final version. All authors had full access to all of the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Guarantor

AGJ is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, Hantel S, Mattheus M, Devins T, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ, Broedl UC, et al. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373:2117–2128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, Diamant M, Ferrannini E, Nauck M, Peters AL, Tsapas A, Wender R, Matthews DR. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach: update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes care. 2015;38:140–149. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Diabetes A. 8. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment. Diabetes care. 2017;40:S64–S74. doi: 10.2337/dc17-S011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Humphrey LL, Forciea MA, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of P Oral Pharmacologic Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Clinical Practice Guideline Update From the American College of Physicians. Annals of internal medicine. 2017;166:279–290. doi: 10.7326/M16-1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Florez JC. Precision Medicine in Diabetes: Is It Time? Diabetes care. 2016;39:1085–1088. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marshall SM. Precision diabetes: a realistic outlook on a promising approach. Diabetologia. 2017;60:766–768. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hattersley AT, Patel KA. Precision diabetes: learning from monogenic diabetes. Diabetologia. 2017;60:769–777. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4226-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sattar N. Biomarkers for diabetes prediction, pathogenesis or pharmacotherapy guidance? Past, present and future possibilities. Diabetic Medicine. 2012;29:5–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montvida O, Shaw J, Atherton JJ, Stringer F, Paul SK. Long-term Trends in Antidiabetes Drug Usage in the U.S.: Real-world Evidence in Patients Newly Diagnosed With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes care. 2017 doi: 10.2337/dc17-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karagiannis T, Paschos P, Paletas K, Matthews DR, Tsapas A. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors for treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the clinical setting: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj. 2012;344:e1369. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bihan H, Ng WL, Magliano DJ, Shaw JE. Predictors of efficacy of GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors: A systematic review. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2016;121:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esposito K, Chiodini P, Maiorino MI, Capuano A, Cozzolino D, Petrizzo M, Bellastella G, Giugliano D. A nomogram to estimate the HbA1c response to different DPP-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 98 trials with 24 163 patients. BMJ open. 2015;5:e005892. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones AG, McDonald TJ, Shields BM, Hill AV, Hyde CJ, Knight BA, Hattersley AT, Group PS Markers of Beta-Cell Failure Predict Poor Glycemic Response to GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Therapy in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes care. 2016;39:250–257. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones AG, Besser RE, McDonald TJ, Shields BM, Hope SV, Bowman P, Oram RA, Knight BA, Hattersley AT. Urine C-peptide creatinine ratio is an alternative to stimulated serum C-peptide measurement in late-onset, insulin-treated diabetes. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association. 2011;28:1034–1038. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Besser RE, Ludvigsson J, Jones AG, McDonald TJ, Shields BM, Knight BA, Hattersley AT. Urine C-peptide creatinine ratio is a noninvasive alternative to the mixed-meal tolerance test in children and adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes care. 2011;34:607–609. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLaughlin T, Abbasi F, Cheal K, Chu J, Lamendola C, Reaven G. Use of metabolic markers to identify overweight individuals who are insulin resistant. Annals of internal medicine. 2003;139:802–809. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes care. 2004;27:1487–1495. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrett E, Gallagher AM, Bhaskaran K, Forbes H, Mathur R, van Staa T, Smeeth L. Data Resource Profile: Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) International journal of epidemiology. 2015;44:827–836. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection E, Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in A. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambert PC, Royston P. Further development of flexible parametric models for survival analysis. Stata Journal. 2009;9:265. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Royston P, Lambert PC. Flexible parametric survival analysis using stata: Beyond the Cox model. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP., Stata Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones AG, Lonergan M, Henley WE, Pearson ER, Hattersley AT, Shields BM. Should Studies of Diabetes Treatment Stratification Correct for Baseline HbA1c? PloS one. 2016;11:e0152428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esposito K, Chiodini P, Maiorino MI, Bellastella G, Capuano A, Giugliano D. Glycaemic durability with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of long-term randomised controlled trials. BMJ open. 2014;4:e005442. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ehrenstein V, Nielsen H, Pedersen AB, Johnsen SP, Pedersen L. Clinical epidemiology in the era of big data: new opportunities, familiar challenges. Clinical epidemiology. 2017;9:245–250. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S129779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bujac S, Del Parigi A, Sugg J, Grandy S, Liptrot T, Karpefors M, Chamberlain C, Boothman AM. Patient Characteristics are not Associated with Clinically Important Differential Response to Dapagliflozin: a Staged Analysis of Phase 3 Data. Diabetes therapy : research, treatment and education of diabetes and related disorders. 2014;5:471–482. doi: 10.1007/s13300-014-0090-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou K, Donnelly LA, Morris AD, Franks PW, Jennison C, Palmer CN, Pearson ER. Clinical and genetic determinants of progression of type 2 diabetes: a DIRECT study. Diabetes care. 2014;37:718–724. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrannini E, Mari A. How to measure insulin sensitivity. Journal of hypertension. 1998;16:895–906. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816070-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim YG, Hahn S, Oh TJ, Kwak SH, Park KS, Cho YM. Differences in the glucose-lowering efficacy of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors between Asians and non-Asians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2013;56:696–708. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2827-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monami M, Cremasco F, Lamanna C, Marchionni N, Mannucci E. Predictors of response to dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors: evidence from randomized clinical trials. Diabetes/metabolism research and reviews. 2011;27:362–372. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson SG, Higgins JP. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Statistics in medicine. 2002;21:1559–1573. doi: 10.1002/sim.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berlin JA, Santanna J, Schmid CH, Szczech LA, Feldman HI, Anti-Lymphocyte Antibody Induction Therapy Study G Individual patient- versus group-level data meta-regressions for the investigation of treatment effect modifiers: ecological bias rears its ugly head. Statistics in medicine. 2002;21:371–387. doi: 10.1002/sim.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esposito K, Chiodini P, Capuano A, Maiorino MI, Bellastella G, Giugliano D. Baseline glycemic parameters predict the hemoglobin A1c response to DPP-4 inhibitors : meta-regression analysis of 78 randomized controlled trials with 20,053 patients. Endocrine. 2014;46:43–51. doi: 10.1007/s12020-013-0090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bloomgarden ZT, Dodis R, Viscoli CM, Holmboe ES, Inzucchi SE. Lower baseline glycemia reduces apparent oral agent glucose-lowering efficacy: a meta-regression analysis. Diabetes care. 2006;29:2137–2139. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jamaluddin JL, Huri HZ, Vethakkan SR. Clinical and genetic predictors of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor treatment response in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Pharmacogenomics. 2016;17:867–881. doi: 10.2217/pgs-2016-0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Donnelly LA, Doney AS, Hattersley AT, Morris AD, Pearson ER. The effect of obesity on glycaemic response to metformin or sulphonylureas in Type 2 diabetes. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association. 2006;23:128–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang ZF, Deng Y, Zhou Y, Fan RR, Chan JC, Laybutt DR, Luzuriaga J, Xu G. Pharmacological reduction of NEFA restores the efficacy of incretin-based therapies through GLP-1 receptor signalling in the beta cell in mouse models of diabetes. Diabetologia. 2013;56:423–433. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2776-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matikainen N, Bogl LH, Hakkarainen A, Lundbom J, Lundbom N, Kaprio J, Rissanen A, Holst JJ, Pietilainen KH. GLP-1 responses are heritable and blunted in acquired obesity with high liver fat and insulin resistance. Diabetes care. 2014;37:242–251. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alssema M, Rijkelijkhuizen JM, Holst JJ, Teerlink T, Scheffer PG, Eekhoff EM, Gastaldelli A, Mari A, Hart LM, Nijpels G, Dekker JM. Preserved GLP-1 and exaggerated GIP secretion in type 2 diabetes and relationships with triglycerides and ALT. European journal of endocrinology. 2013;169:421–430. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeevi D, Korem T, Zmora N, Israeli D, Rothschild D, Weinberger A, Ben-Yacov O, Lador D, Avnit-Sagi T, Lotan-Pompan M, Suez J, et al. Personalized Nutrition by Prediction of Glycemic Responses. Cell. 2015;163:1079–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.