Summary

Studies on regulatory T cells (Treg) have focused on thymic Treg as a stable lineage of immunosuppressive T cells, the differentiation of which is controlled by the transcription factor forkhead box protein 3 (Foxp3). This lineage perspective, however, may constrain hypotheses regarding the role of Foxp3 and Treg in vivo, particularly in clinical settings and immunotherapy development. In this review, we synthesize a new perspective on the role of Foxp3 as a dynamically expressed gene, and thereby revisit the molecular mechanisms for the transcriptional regulation of Foxp3. In particular, we introduce a recent advancement in the study of Foxp3‐mediated T cell regulation through the development of the Timer of cell kinetics and activity (Tocky) system, and show that the investigation of Foxp3 transcriptional dynamics can reveal temporal changes in the differentiation and function of Treg in vivo. We highlight the role of Foxp3 as a gene downstream of T cell receptor (TCR) signalling and show that temporally persistent TCR signals initiate Foxp3 transcription in self‐reactive thymocytes. In addition, we feature the autoregulatory transcriptional circuit for the Foxp3 gene as a mechanism for consolidating Treg differentiation and activating their suppressive functions. Furthermore, we explore the potential mechanisms behind the dynamic regulation of epigenetic modifications and chromatin architecture for Foxp3 transcription. Lastly, we discuss the clinical relevance of temporal changes in the differentiation and activation of Treg.

Keywords: Foxp3, Nr4a3, regulatory T cells (Treg), Time of cell kinetics and activity (Tocky), transcriptional autoregulatory circuit

Introduction

Dynamics of Foxp3 transcription as a key to understanding regulatory T cell‐mediated immune regulation

It is widely considered that regulatory T cells (Treg) constitute a distinct lineage of CD4+ T cells dedicated for immunosuppression 1. Key evidence for the distinct lineage include: (i) Treg development is controlled by the transcription factor Foxp3 2; and (ii) the development of Treg in the thymus is delayed to after that of other T cells under physiological conditions 3. However, accumulating evidence shows the simultaneous development of Treg and other T cells 4, 5 and Treg plasticity is now widely recognized, as Treg can lose forkhead box protein 3 (Foxp3) expression and become effector T cells (ex‐Treg) during inflammation 6, 7. Thus, studies on dynamic changes in the differentiation and activation status of Tregs – and other T cells – in vivo is essential for understanding Foxp3‐mediated T cell regulation. This dynamic perspective is important not only for basic research but also clinical research and immunotherapy development, which is illustrated by the catastrophic clinical trial of the superagonistic anti‐CD28 antibody TGN1412 in 2006.

TGN1412 was developed as an immunosuppressive treatment after an anti‐CD28 antibody was found to suppress autoimmune reactions in rodent models 8. TGN1412 was thus designed to bind to the CD28 molecule on the surface of Treg which would, in turn, theoretically suppress non‐Tregs 9. This trial, however, resulted in catastrophe, where all six volunteers given TGN1412 developed a ‘cytokine storm’ due to stimulation of a significant proportion of T cells 10. Later, it was found that CD28 molecules in memory‐phenotype T cells are down‐regulated in primates – which does not occur in humans – and this species difference was deemed to be the major cause of the incident 11. Meanwhile, Vitetta and Ghetie pointed out that Tregs and non‐Tregs may not represent strictly separate lineages, and therefore the assumption of specific activation of Tregs may have been inappropriate 12. In fact, basic studies later showed the plasticity of Tregs: Tregs may lose Foxp3 expression during inflammation and non‐Tregs may acquire Foxp3 expression 13. Summarizing, the case provides two important lessons: first, the concepts of lineage stability may constrain hypotheses, which can be detrimental in clinical settings; and secondly, it is fundamental to investigate the dynamic changes in the differentiation and activation statuses of Tregs and other T cells in vivo, which are still poorly understood.

The key evidence of Foxp3 as the lineage‐specification transcription factor is that mutations in the Foxp3/FOXP3 gene can lead to autoimmune disease in both mice 14 and humans 15. However, this does not preclude the dynamic induction of Foxp3 as a negative regulator in response to T cell activation. In fact, Foxp3 expression can be induced solely by T cell receptor (TCR) signals in human T cells 16 and, although less efficiently, also in mice 17, and the induction is enhanced by transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β and interleukin (IL)‐2 18. TGF‐β is produced by activated antigen‐presenting cells such as dendritic cells 19 and macrophages 20, while IL‐2 is produced mainly by activated T cells, particularly CD4+ T cells 21. As the immunosuppressive Treg population is commonly identified by the expression of Foxp3 (as Foxp3+ T cells in mice 2 and Foxp3highCD45RA+ 22, 23 or Foxp3+CD127–CD25high T cells 24, 25 in humans), the investigation of Foxp3 dynamics in vivo, especially during immune responses, will be key for understanding the in‐vivo dynamics of Treg and T cell regulation. To this end, we have recently developed a new technology, the Timer of cell kinetics and activity (Tocky) system, which allows the investigation of invivo dynamics of Foxp3 and Tregs during physiological immune responses 26, 27.

In this paper, we will aim to introduce a dynamic perspective to the molecular mechanisms that account for the transcriptional and epigenetic control of the Foxp3 gene, and thereby to improve the understanding of Foxp3‐mediated T cell regulation in vivo.

Development of Tocky for investigating in‐vivo dynamics of Treg differentiation

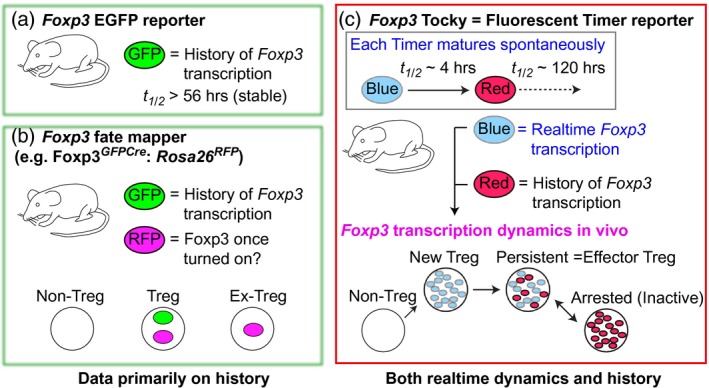

The current understanding of Treg differentiation and function is based significantly on evidence obtained by Foxp3 fluorescent protein (FP) reporters such as enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) 28, 29 and fate mapping systems for the Foxp3 gene (e.g. Foxp3CreGFP:Rosa26RFP 17 and Foxp3ERT2CreGFP:Rosa26YFP 30). Notably, all these systems rely upon stable FPs such as GFP, the half‐life of which is longer than 56 h. Therefore, temporal changes in Foxp3 transcription shorter than 2–3 days cannot be investigated by these reporter systems.

In order to understand the in‐vivo dynamics of those molecular mechanisms underlying the differentiation and function of Tregs, we have recently developed the Tocky system using Fluorescent Timer protein (Timer). Timer proteins exhibit a short‐lived blue fluorescent form, before maturation to the stable red state 27, 31. The half‐life of blue fluorescence is ~ 4 h 26, 27 and that of the mature red fluorescence is ~ 5 days 26. Thus, blue and red fluorescence (blue and red) provide a measurement of both the ‘real‐time’ activity and the history of gene transcription 26. Tocky uses this information to analyse dynamic changes quantitatively in transcriptional activities during cellular activation and differentiation 27. Importantly, we have identified three characteristic dynamics of transcription in the Tocky system: blue+red– cells are those that have just initiated transcription (new); blue+red+ cells along the diagonal line between blue and red axes are those with sustained transcription, accumulating both blue and red form proteins (persistent); and blue–red+ cells are those that have recently down‐regulated gene expression under the detection threshold of flow cytometry and are inactive in transcription of the gene (arrested or inactive) 27 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of tools to investigate forkhead box protein 3 (Foxp3)‐expressing T cells in vivo. (a) Most Foxp3 reporter mice use stable fluorescent proteins (FP), such as enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), the half‐life of which is > 56 h. (b) Foxp3 fate mappers such as Foxp3GFPCre:Rosa26RFP allow the identification of regulatory T cells (Tregs) with Foxp3 expression and ex‐Tregs that lost Foxp3 expression. Notably, both GFP and red fluorescent protein (RFP) are stable FPs. (c) Foxp3–Tocky uses fluorescent timer, the emission spectrum of which changes spontaneously and irreversibly from blue to red fluorescence. The half‐life of blue fluorescence is ~4 h, and thus reports the ‘real‐time’ activity of Foxp3 transcription. In contrast, the half‐life of red fluorescence is ~120 h and thus reports the history of Foxp3 transcription. The Tocky system combines blue and red fluorescence data and identifies characteristic transcriptional dynamics including new, persistent and arrested (inactive).

Foxp3 transcription is controlled mainly by 5' upstream sequences and conserved non‐coding sequences (CNS) 1–3 in intronic regions 7, 32, 33, 34. Importantly, while TCR signals (together with TGF‐β and IL‐2 signals) induce Foxp3 expression in any T cells in vitro 18, naturally arising Foxp3 expression is found mainly in self‐reactive T cells in non‐inflammatory conditions 1. Thus, we will classify the mechanisms for Foxp3 transcription into two groups, as follows:

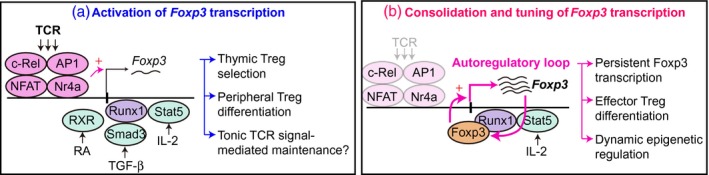

Mechanisms for the activation of Foxp3 transcription: these are used during thymic Treg selection and peripheral Treg differentiation and are potentially involved in the mechanism for tonic TCR signal‐mediated activation of Foxp3 transcription.

Mechanisms for the consolidation and tuning of Foxp3 transcription: these are used for sustaining Foxp3 transcription over time, which induces effector Treg differentiation and the dynamic regulation of epigenetic modifications, such as demethylation of CpG islands in enhancer regions (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Activation versus consolidation and tuning of Foxp3 transcription. We propose to classify Foxp3 transcriptional regulation into two major mechanisms. (a) Activation of Foxp3 transcription is regulated mainly by T cell receptor (TCR) signals and enhanced by interleukin (IL)‐2, transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β and retinoic acid (RA). This may lead to thymic regulatory T cell (Treg) selection and peripheral Treg differentiation. In addition, tonic TCR signals through self‐reactive TCRs may use this mechanism to regulate homeostatic Foxp3 transcription. (b) Consolidation and tuning of Foxp3 transcription. The maintenance of Foxp3 transcription requires CNS2 of the Foxp3 gene, which may provide a platform for Foxp3–Runx1/CBF‐β complex to form the autoregulatory transcriptional circuit (autoregulatory loop) for the Foxp3 gene. The activity of this loop can be affected by IL‐2 signalling via phosphorylated signal tranducer and activator of transcription‐5 (STAT)‐5. This mechanism may lead to temporally persistent Foxp3 transcription, which promotes effector Treg differentiation, and the dynamic regulation of epigenetic modifications during Treg differentiation.

Mechanisms for the activation of Foxp3 transcription

Foxp3 as a TCR signal downstream gene

The differentiation and function of Tregs is under the control of TCR signals 35, 36, 37, 38. In the thymus, the recognition of cognate antigen induces not only negative selection but also the differentiation of CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs from CD4‐SP cells using transgenic TCR systems 39, 40, 41. Conversely, TCR transgenic mice in the recombination activating gene (Rag)‐deficient backgrounds lack Foxp3+ T cells due to the absence of self‐antigen recognition 42, 43. The analysis of TCR signals using reporter mice have provided insights into the mechanism for TCR‐mediated Treg differentiation. The Hogquist group showed that Tregs receive strong TCR signals in the thymus and the periphery when analysed using a Nur77(Nr4a1)‐GFP transgenic reporter 44. Using Nr4a3–Tocky, we have shown that Foxp3 expression in the thymus occurs in T cells that have received temporally persistent TCR signals 27. Furthermore, using Foxp3–Tocky we showed that Foxp3 transcription is initiated in non‐Treg cells during inflammation in the periphery 26. In humans, activation‐induced Foxp3 in conventional T cells suppresses their proliferation and cytokine production in a cell‐intrinsic manner 45. In addition, activated conventional T cells can express both Foxp3 and cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen‐4 (CTLA‐4), and thereby acquire the suppressive function that is dependent upon CTLA‐4 46. These suggest that Foxp3 has a role in negative feedback regulation of T cell activation in co‐operation with other immunoregulatory molecules, including CTLA‐4. Foxp3 transcription, therefore, is thus under the control of TCR signals in both the thymus and the periphery. In addition, in normal homeostasis, Tregs and naturally arising memory‐phenotype T cells are self‐reactive and receive ‘tonic’ TCR signals in the periphery 27, 44. Considering this evidence, the biological meaning of TCR signal‐induced Foxp3 expression includes two situations: (i) antigen recognition‐induced Foxp3 transcription in Foxp3– cells (conventional T cells; non‐Tregs) in the thymus and the periphery; and (ii) the effects of tonic TCR signals in Foxp3+ Tregs.

In line with the evidence of Foxp3 expression upon TCR stimulation, the gene regulatory regions of the Foxp3 gene are bound by transcription factors downstream of major branches of the TCR signalling pathway, including nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) and activator protein 1 (AP1) 47, the nuclear factor kappa B (NF‐B) components c‐Rel and p65 32, 48, 49, 50, cyclic AMP response element‐binding protein (CREB) 51 and Nr4a proteins 52 (Fig. 2).

Nr4a proteins (Nr4a1, Nr4a2 and Nr4a3) bind to their target sequences as homodimers or heterodimers and regulate transcription 53, 54. Foxp3+ Treg differentiation is abolished in Nr4a1/2/3 triple knock‐out (KO) mice and Nr4a1/3 double KO, and these mice develop fatal autoinflammatory disease 52. Nr4a proteins bind to the Foxp3 promoter upon anti‐CD3 stimulation 52 and retroviral gene transduction of Nr4a2 or Nr4a3 induces Foxp3 transcription 55. Importantly, however, Nr4a triple KO lack not only Foxp3+ Tregs but also most of the double‐positive (DP) cell population 52, which suggests that the Treg reduction in these KO mice is a consequence of defective regulation of positive and negative selection. Meanwhile, we have identified Nr4a3 as the gene that is the most correlated with the effects of TCR signals in the thymus and the periphery, followed by Nr4a1 27. Specifically, using canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) 56, we analysed the transcriptome data set of thymic T cell populations and that of resting and anti‐CD3 stimulated peripheral T cells, and thereby identified the genes that were correlated with both thymic T cells under selection (in‐vivo TCR signals) and peripheral T cell activation 27. By developing Nr4a3–Tocky, we have shown that temporally persistent TCR signals sustain Nr4a3 transcription and initiate Foxp3 transcription 27. This leads to the new model for Nr4a, that the recognition of cognate antigen conveys persistent TCR signals, which induce and accumulate Nr4a proteins and thereby control thymic selection and differentiation processes including Treg differentiation.

Foxp3 transcription‐enhancing cytokine signals

Foxp3 transcription is activated by IL‐2 signalling in the presence of TCR stimulation and TGF‐β signalling 18. However, it is unknown whether these cytokine signals can regulate Foxp3 transcription independently from TCR signalling.

IL‐2 signalling is a central cytokine for T cell activation, proliferation and differentiation 21. The expression of CD25 (IL‐2R α‐chain) is induced by TCR and CD28 signals and forms the high‐affinity IL‐2R, together with IL‐2R β ‐chain (CD122) and the common ‐chain (CD132) 57, 58. IL‐2 binding to IL‐2R triggers phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)‐4 and STAT‐5 by the associated kinases Janus kinase (Jak)1 and Jak3, which promote cell cycle entry and proliferation of TCR‐stimulated T cells 59. In addition to the role in T cell activation, CD25 is also a surface marker for Treg in mice 60 and humans 61. In fact, IL‐2 signalling is functional in Tregs. Phosphorylated STAT‐5 binds to the promoter and CNS2 and activates Foxp3 transcription 62, 63. KO mice for the genes that are involved in IL‐2 signalling (Il2 64, Il2ra 64, Il2rb 65, Jak3 66 and Stat5a/Stat5b 67) have reduced Foxp3+ T cells in the thymus and periphery. Thus, IL‐2 signalling is required for the activation of Foxp3 transcription, most probably during both the early phase of Treg differentiation as well as the maintenance of both Foxp3 transcription and the Treg population. Considering the primary role of IL‐2 for the activation and proliferation of T cells 21, this suggests a role of Foxp3 as a sensor for the IL‐2 abundance in the environment surrounding individual T cells. In other words, when T cells are activated IL‐2 becomes abundant, which enhances Foxp3 expression in nearby T cells. Given that IL‐2R expression in Tregs absorbs IL‐2 and suppresses IL‐2‐mediated T cell proliferation 68, the size of the T cell population may be self‐regulated through the feedback mechanism involving IL‐2, CD25 and Foxp3 38.

TGF‐β signalling has multi‐faceted effects on tissue development and regeneration, inflammation and cancer in a context‐dependent manner 69. The importance of TGF‐β signalling in T cells is recognized particularly in mucosal and tumour immunity 70. The transcriptional response of T cells to TGF‐β signalling is also context‐dependent, and is illustrated by the reciprocal differentiation of T helper type 17 (Th17) and Tregs by IL‐6 and IL‐2, respectively, in the presence of TGF‐β 71, 72. TGF‐β signal‐activated Mothers Against DPP Homologue 3 (SMAD3) binds to the CNS1 of the Foxp3 gene 32, 73. However, the genetic deletion of the SMAD‐binding site does not change the frequencies of Tregs in the thymus and the periphery, apart from marginal reductions of Foxp3+ T cells in Peyer’s patches and lamina propria in aged mice 74. This suggests that TGF‐β controls Foxp3 transcription through multiple sites in the Foxp3 gene and/or through the induction of other factors. While IL‐2 signalling is intrinsically required for Treg differentiation, as discussed above, the opposing effects of IL‐6 signalling seem to be reactive and inflammation‐dependent, as the genetic deletion of Stat3 does not affect Treg populations, while inhibiting the differentiation of Tregs in the CD45RBhigh T cell‐mediated colitis model 75.

Veldhoen and Stockinger have proposed the model that TGF‐β skews CD4+ T cell differentiation from Th1 to Th17 76, and as such, TGF‐β may shift T cells from the Th1–Th2 axis to the Th17–Treg axis. In the TGF‐β‐rich microenvironment, such as in the intestines, tumour or damaged tissues undergoing regeneration and remodelling, the persistence of pathogen or autoantigen may activate monocytes and dendritic cells, and thereby repress Foxp3 transcription and promote Th17 differentiation, as observed in rheumatoid arthritis patients 77. In contrast, once the activation of innate immune cells is terminated, Foxp3 transcription may be initiated in antigen‐reactive T cells, as observed by Foxp3–Tocky 26, especially when adjacent T cells are proliferating and producing IL‐2, inducing the resolution of inflammation.

Mechanisms for the consolidation and tuning of Foxp3 transcription – the role of autoregulatory transcriptional circuit for the Foxp3 gene

The maintenance of Foxp3 transcription in Treg requires conserved non‐coding sequences 2 (CNS2), which includes the widely studied Treg‐specific demethylated region, TSDR 33. The cytosine–phosphate–guanine (CpG) motifs in the TSDR are methylated in non‐Treg cells and fully demethylated in thymic Tregs 22, 33. The genetic deletion of CNS2 results in the reduction of Foxp3 expression in thymic Tregs but does not affect Foxp3 induction in vitro 32. CNS2 is bound by several key transcription factors, including the Runx/Cbf‐β complex 78, 79, 80, 81, Ets‐1 82, which makes an active complex with Runx1 83, Foxp3 protein 32 and STAT‐5 63.

Foxp3 binding to CNS2 is dependent upon Runx1/CBF‐β 32. Importantly, the expression of Foxp3 in Tregs is reduced in both CBF‐β‐deficient Tregs 78 and CNS2‐deleted Tregs 34. CNS2 is required for maintaining the number of Tregs in the periphery during homeostasis and is also important for sustaining Foxp3 expression during inflammation 7, 34. CNS2‐deleted Tregs lose Foxp3 expression in the presence of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL‐4 and IL‐6, and become effector T cells to enhance autoimmune inflammation in mice 7. Furthermore, analysis of TCR repertoires in human Tregs also suggests the dynamic regulation of both CD25 and Foxp3 on T cells in rheumatoid arthritis 84. These data together suggest that, although Foxp3 expression is commonly recognized to be stable, it is in fact dynamically regulated in Foxp3+ Tregs during homeostasis and during immune responses.

Our recent investigations using Foxp3–Tocky have shown that, intriguingly, resting Tregs have intermittent Foxp3 transcription, while activated effector Tregs with high expression of immunoregulatory molecules (including CTLA‐4 and IL‐10) have more sustained Foxp3 transcription throughout time 26. The phenotype of these effector Tregs with temporally persistent Foxp3 transcription is in fact very similar to those of the effector Tregs that are dependent upon Myb 85 and the CD44highCD62Llow activated Tregs that are dependent upon TCR signals 35, which supports the model that TCR signals induce temporally persistent Foxp3 transcription and thereby enhance the suppressive phenotype of Tregs. Furthermore, by analysing female mice with heterozygosity for a hypomorphic Foxp3 mutant (namely, Scurfy mutation), Foxp3 protein sustains the temporally persistent Foxp3 transcriptional dynamics that promote effector Treg functions 26. In the thymus, the active demethylation of the TSDR occurs only after the initiation of Foxp3 transcription and when Foxp3 transcription is highly sustained over time 27. These indicate that Foxp3 protein and the Foxp3 gene form an autoregulatory loop that consolidates the Treg‐type TSDR demethylation during thymic differentiation 27, and tunes Foxp3 transcriptional activities and thereby activates their suppressive activity during inflammation 26. Given the critical roles of the Runx1/Cbf‐β complex in the maintenance of Foxp3 expression and the Foxp3–Runx1 interaction in Treg differentiation and function, it is plausible that this autoregulatory transcriptional circuit is formed via the binding of Foxp3‐Runx1/Cbf‐β complex 32 to CNS2 of the Foxp3 gene (Fig. 2).

Dynamic regulation of epigenetic modifications and chromatin architecture of the Foxp3 gene

TCR‐induced Foxp3 transcriptional activities can be opposed by epigenetic mechanisms for silencing Foxp3 transcription. The SUMO E3 ligase Pias3 binds to the Foxp3 promoter, and Pias1 KO mice have increased frequencies of Foxp3+ cells in CD4+ T cells and reduced methylation of histone H3 at Lys9 (H3K9), which is a hallmark of repressed genes 86. The DNA methyltransferase DNA (cytosine‐5)‐methyltransferases (Dnmt1) and the high mobility group transcription factors Tcf1 and Lef1 constitutively repress Foxp3 transcription in CD8+ T cells, as Dnmt1 –/– or Tcf1 –/– Lef1 –/– double KO permits the differentiation of Foxp3+CD8+ T cells, which are rarely found in normal mice 87, 88. In addition, the induction of Foxp3 expression in Dnmt1 –/– T does not require TGF‐β 87, suggesting that TGF‐β probably modulates epigenetic mechanisms in normal mice. Strong TCR signalling in vitro causes the accumulation of Dnmt1 at the Foxp3 promoter, which can lead to increased CpG methylation and inhibition of Foxp3 transcription 89. Thus, TGF‐β may be important for tuning Dnmt1 expression during T cell activation.

Foxp3–Tocky has shed light on the dynamics of Foxp3 epigenetic regulation following the initiation of Foxp3 transcription. Importantly, Foxp3 transcription precedes the demethylation of TSDR in the thymus. Both thymic new Foxp3 expressors, which are identified by Tocky 27, and immature CD24highFoxP3+CD4SP by Foxp3‐EGFP mice 90 have fully methylated TSDR. The active process for TSDR demethylation occurs only after Foxp3 transcription is sustained over time and the Foxp3 autoregulatory loop is formed 26. Collectively, the interactions between Foxp3‐inducing and inhibiting factors occur during the early phase of Treg differentiation when the Foxp3 gene is still ‘silenced’, and we would therefore hypothesize that Foxp3 protein may also have roles in dynamically regulating the epigenetic modifications of the Foxp3 gene. Future studies could therefore address the role of Foxp3 in the dynamic regulation of chromatin architecture, which can be investigated by chromatin conformation capture (3C) and derivative methods (e.g. Hi‐C). For example, the Zheng group showed that, using 3C, NFAT activation induces the interaction of the TSDR‐containing CNS2 with the Foxp3 promoter, which facilitates enhanced Foxp3 transcription 34. Using Hi‐C and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)‐mediated mutation, the Zhao group showed that the mixed lineage leukaemia (MLL) family methyltransferase MLL4 binds to –8·5k upstream enhancer of the Foxp3 gene, and makes a chromatin loop to promote the monomethylation of histone H3 at Lys4 (H3K4me1) in the promoter and CNS3, which activates Foxp3 transcription 91. The chromatin organizing factor special AT‐rich sequence binding protein 1 (SATB1) is also involved in activating Foxp3 transcription in the thymus, as the genetic deletion of SATB1 results in the marked reduction of Foxp3+ Tregs and the accumulation of thymic CD25+Foxp3– Treg precursors with reduced enhancer activity [which are identified by acetylation of histone H3 at Lys27 (H3K27ac)] 92. Thus, it is likely that chromatin remodelling of the Foxp3 gene underlies the temporally dynamic Foxp3 autoregulatory loop, suggesting that the former is also induced dynamically through the interactions between Foxp3 protein and key chromatin organizers and epigenetic regulators. In addition, as those chromatin organizers and epigenetic regulators control not only the Foxp3 gene but also other genes, the chromatin remodelling of Foxp3‐target genes may be also induced dynamically in activated Tregs and differentiating Tregs. Future studies, therefore, should investigate the role of Foxp3 protein and its co‐factors in the temporally dynamic regulation of chromatin structure within and outside the Foxp3 gene region.

Dynamic Foxp3 expression in vivo: perspectives for basic immunology and clinical relevance

After the emergence of single‐cell technologies and the Tocky tool, studies on T cell regulation are shifting from the stability and plasticity of Treg to the investigation of temporal changes in Foxp3‐mediated mechanisms in vivo. Our analysis of Tregs in peripheral immune compartments show that, in non‐inflammatory conditions, Foxp3 transcription is most probably modelled by intermittent gene activity 26. This intermittent transcription may offer an explanation for the low frequency of Treg cells with detectable Foxp3 transcripts in Treg cells analysed by single‐cell RNA‐seq 93, 94, although these data sets have limitations due to shallow sequencing depths. Given that the temporal changes in Foxp3 transcription control Treg function and effector Treg differentiation, future work will investigate the molecular mechanisms that control the real‐time transcribing of the Foxp3 gene, which can be analysed by the Tocky system. In addition, in line with the temporally dynamic regulation of Foxp3 transcription in vivo, the significance of thymic and peripheral Treg markers needs to be readdressed. Our investigation using Foxp3–Tocky has confirmed that the expression of Neuropilin 1 95 and Helios 96 are dynamically regulated in Tregs according to Foxp3 transcription dynamics 26, and therefore are not faithful markers of thymic Tregs, as has been noted previously in the literature 97.

Importantly, clinical studies and immunotherapy development may be benefited by the endorsement of the dynamic perspective. Whether targeting Tregs or not, immunotherapy may dynamically change Foxp3 transcription. If these dynamic responses are clarified, immunotherapy targeting T cells may be better designed with a more tailored strategy, as we recently showed by manipulating Foxp3 transcriptional dynamics through targeting inflammation‐reactive effector Tregs by OX40 (CD134) and tumour necrosis factor receptor II (Tnfrsf1b which are expressed specifically in Tregs with temporally persistent Foxp3 transcription 26. We therefore envisage that the investigation of dynamic changes in molecular mechanisms during T cell responses in vivo will improve the predictability of preclinical studies and thereby contribute to the development of new immunotherapies for autoimmune and cancer patients.

Disclosures

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist in relation to this paper.

Acknowledgements

D. B. is funded by a University of Birmingham Fellowship. M. O. is a David Phillips Fellow (BB/J013951/2) from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC).

OTHER ARTICLES PUBLISHED IN THIS REVIEW SERIES

Regulatory T cells: exploring mechanisms for future therapies. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2019, 197: 11–13.

The role of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in human autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2019, 197: 24–35.

Mechanisms of human FoxP3+ Treg cell development and function in health and disease. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2019, 197: 36–51.

Methods to manufacture regulatory T cells for cell therapy. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2019, 197: 52–63.

References

- 1. Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell 2008; 133:775–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Josefowicz SZ, Lu LF, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annu Rev Immunol 2012; 30:531–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hsieh CS, Lee HM, Lio CW. Selection of regulatory T cells in the thymus. Nat Rev Immunol 2012; 12:157–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dujardin HC, Burlen‐Defranoux O, Boucontet L, Vieira P, Cumano A, Bandeira A. Regulatory potential and control of Foxp3 expression in newborn CD4+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101:14473–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Samy ET, Wheeler KM, Roper RJ, Teuscher C, Tung KS. Cutting edge: autoimmune disease in day 3 thymectomized mice is actively controlled by endogenous disease‐specific regulatory T cells. J Immunol 2008;180:4366–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bailey‐Bucktrout SL, Martinez‐Llordella M, Zhou X et al Self‐antigen‐driven activation induces instability of regulatory T cells during an inflammatory autoimmune response. Immunity 2013; 39:949–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Feng Y, Arvey A, Chinen T, van der Veeken J, Gasteiger G, Rudensky AY. Control of the inheritance of regulatory T cell identity by a cis element in the Foxp3 locus. Cell 2014; 158:749–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beyersdorf N, Gaupp S, Balbach K et al Selective targeting of regulatory T cells with CD28 superagonists allows effective therapy of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med 2005; 202:445–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hünig T. The storm has cleared: lessons from the CD28 superagonist TGN1412 trial. Nat Rev Immunol 2012; 12:317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Suntharalingam G, Perry MR, Ward S et al. Cytokine storm in a phase 1 trial of the anti‐CD28 monoclonal antibody TGN1412. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:1018–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eastwood D, Findlay L, Poole S et al Monoclonal antibody TGN1412 trial failure explained by species differences in CD28 expression on CD4+ effector memory T‐cells. Br J Pharmacol 2010; 161:512–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vitetta ES, Ghetie VF. Immunology. Considering therapeutic antibodies. Science 2006; 313:308–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhou X, Bailey‐Bucktrout S, Jeker LT, Bluestone JA. Plasticity of CD4(+) FoxP3(+) T cells. Curr Opin Immunol 2009; 21:281–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Godfrey VL, Wilkinson JE, Russell LB. X‐linked lymphoreticular disease in the scurfy (sf) mutant mouse. Am J Pathol 1991; 138:1379–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bennett CL, Christie J, Ramsdell F et al The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X‐linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat Genet 2001; 27:20–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tran DQ, Ramsey H, Shevach EM. Induction of FOXP3 expression in naive human CD4+FOXP3 T cells by T‐cell receptor stimulation is transforming growth factor‐beta dependent but does not confer a regulatory phenotype. Blood 2007; 110:2983–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miyao T, Floess S, Setoguchi R et al Plasticity of Foxp3(+) T cells reflects promiscuous Foxp3 expression in conventional T cells but not reprogramming of regulatory T cells. Immunity 2012; 36:262–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N et al Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25‐ naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF‐beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med 2003; 198:1875–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ghiringhelli F, Puig PE, Roux S et al Tumor cells convert immature myeloid dendritic cells into TGF‐β–secreting cells inducing CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell proliferation. J Exp Med 2005; 202:919–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huynh ML, Fadok VA, Henson PM. Phosphatidylserine‐dependent ingestion of apoptotic cells promotes TGF‐beta1 secretion and the resolution of inflammation. J Clin Invest 2002; 109:41–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Malek TR. The biology of interleukin‐2. Annu Rev Immunol 2008; 26:453–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Miyara M, Yoshioka Y, Kitoh A et al Functional delineation and differentiation dynamics of human CD4+ T cells expressing the FoxP3 transcription factor. Immunity 2009; 30:899–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fujii H, Josse J, Tanioka M, Miyachi Y, Husson F, Ono M. Regulatory T cells in melanoma revisited by a computational clustering of FOXP3+ T cell subpopulations. J Immunol 2016; 196:2885–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Seddiki N, Santner‐Nanan B, Martinson J et al. Expression of interleukin (IL)‐2 and IL‐7 receptors discriminates between human regulatory and activated T cells. J Exp Med 2006; 203:1693–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu W, Putnam AL, Xu‐Yu Z et al CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ T reg cells. J Exp Med 2006; 203:1701–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bending D, Paduraru A, Ducker CB, Prieto Martín P, Crompton T, Ono M. A temporally dynamic Foxp3 autoregulatory transcriptional circuit controls the effector Treg programme. EMBO J 2018; 37:e99013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bending D, Martín PP, Paduraru A et al A timer for analyzing temporally dynamic changes in transcription during differentiation in vivo . J Cell Biol 2018; 217:2931–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Williams LM, Dooley JL, Farr AG, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3. Immunity 2005; 22:329–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haribhai D, Lin W, Relland LM, Truong N, Williams CB, Chatila TA. Regulatory T cells dynamically control the primary immune response to foreign antigen. J Immunol 2007; 178:2961–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rubtsov YP, Niec RE, Josefowicz S et al Stability of the regulatory T cell lineage in vivo . Science 2010; 329:1667–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Subach FV, Subach OM, Gundorov IS et al Monomeric fluorescent timers that change color from blue to red report on cellular trafficking. Nat Chem Biol 2009; 5:118–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zheng Y, Josefowicz S, Chaudhry A, Peng XP, Forbush K, Rudensky AY. Role of conserved non‐coding DNA elements in the Foxp3 gene in regulatory T‐cell fate. Nature 2010; 463:808–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Floess S, Freyer J, Siewert C et al Epigenetic control of the foxp3 locus in regulatory T cells. PLOS Biol 2007; 5:e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li X, Liang Y, LeBlanc M, Benner C, Zheng Y. Function of a Foxp3 cis‐element in protecting regulatory T cell identity. Cell 2014; 158:734–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Levine AG, Arvey A, Jin W, Rudensky AY. Continuous requirement for the TCR in regulatory T cell function. Nat Immunol 2014; 15:1070–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vahl JC, Drees C, Heger K et al Continuous T cell receptor signals maintain a functional regulatory T cell pool. Immunity 2014; 41:722–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li MO, Rudensky AY. T cell receptor signalling in the control of regulatory T cell differentiation and function. Nat Rev Immunol 2016; 16:220–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ono M, Tanaka RJ. Controversies concerning thymus‐derived regulatory T cells: fundamental issues and a new perspective. Immunol Cell Biol 2016; 94:3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jordan MS, Boesteanu A, Reed AJ et al Thymic selection of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells induced by an agonist self‐peptide. Nat. Immunol 2001; 2:301–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bautista JL, Lio CW, Lathrop SK et al Intraclonal competition limits the fate determination of regulatory T cells in the thymus. Nat Immunol 2009; 10:610–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Klein L, Kyewski B, Allen PM, Hogquist KA. Positive and negative selection of the T cell repertoire: what thymocytes see (and don't see). Nat Rev Immunol 2014; 14:377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Itoh M, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi N et al Thymus and autoimmunity: production of CD25+CD4+ naturally anergic and suppressive T cells as a key function of the thymus in maintaining immunologic self‐tolerance. J Immunol 1999; 162:5317–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Curotto de Lafaille MA, Lino AC. Kutchukhidze N, Lafaille JJ. CD25– T cells generate CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells by peripheral expansion. J Immunol 2004; 173:7259–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moran AE, Holzapfel KL, Xing Y et al T cell receptor signal strength in Treg and iNKT cell development demonstrated by a novel fluorescent reporter mouse. J Exp Med 2011; 208:1279–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McMurchy AN, Gillies J, Gizzi MC et al A novel function for FOXP3 in humans: intrinsic regulation of conventional T cells. Blood 2013; 121:1265–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zheng Y, Manzotti CN, Burke F et al Acquisition of suppressive function by activated human CD4+ CD25– T cells is associated with the expression of CTLA‐4 not FoxP3. J Immunol 2008; 181:1683–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mantel PY, Ouaked N, Ruckert B et al Molecular mechanisms underlying FOXP3 induction in human T cells. J Immunol 2006; 176:3593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Isomura I, Palmer S, Grumont RJ et al c‐Rel is required for the development of thymic Foxp3+ CD4 regulatory T cells. J Exp Med 2009; 206:3001–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Long M, Park SG, Strickland I, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Nuclear factor‐kappaB modulates regulatory T cell development by directly regulating expression of Foxp3 transcription factor. Immunity 2009; 31:921–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ruan Q, Kameswaran V, Tone Y et al Development of Foxp3(+) regulatory t cells is driven by the c‐Rel enhanceosome. Immunity 2009; 31:932–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kim HP, Leonard WJ. CREB/ATF‐dependent T cell receptor‐induced FoxP3 gene expression: a role for DNA methylation. J Exp Med 2007; 204:1543–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sekiya T, Kashiwagi I, Yoshida R et al Nr4a receptors are essential for thymic regulatory T cell development and immune homeostasis. Nat Immunol 2013; 14:230–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Maira M, Martens C, Philips A, Drouin J. Heterodimerization between members of the Nur subfamily of orphan nuclear receptors as a novel mechanism for gene activation. Mol Cell Biol 1999; 19:7549–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Duren RP, Boudreaux SP, Conneely OM. Genome wide mapping of NR4A binding reveals cooperativity with ETS factors to promote epigenetic activation of distal enhancers in acute myeloid leukemia cells. PLOS ONE 2016; 11:e0150450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sekiya T, Kashiwagi I, Inoue N et al The nuclear orphan receptor Nr4a2 induces Foxp3 and regulates differentiation of CD4+ T cells. Nat Commun 2011; 2:269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ono M, Tanaka RJ, Kano M. Visualisation of the T cell differentiation programme by canonical correspondence analysis of transcriptomes. BMC Genomics 2014; 15:1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shimizu A, Kondo S, Sabe H, Ishida N, Honjo T. Structure and function of the interleukin 2 receptor: affinity conversion model. Immunol Rev 1986; 92:103–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gaffen SL. Signaling domains of the interleukin 2 receptor. Cytokine 2001; 14:63–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Smith GA, Uchida K, Weiss A, Taunton J. Essential biphasic role for JAK3 catalytic activity in IL‐2 receptor signaling. Nat Chem Biol 2016; 12:373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Immunologic self‐tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL‐2 receptor alpha‐chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self‐tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol 1995; 155:1151–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Baecher‐Allan C, Brown JA, Freeman GJ, Hafler DA. CD4+CD25high regulatory cells in human peripheral blood. J Immunol 2001; 167:1245–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Burchill MA, Yang J, Vogtenhuber C, Blazar BR, Farrar MA. IL‐2 receptor beta‐dependent STAT5 activation is required for the development of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol 2007; 178:280–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yao Z, Kanno Y, Kerenyi M et al Nonredundant roles for Stat5a/b in directly regulating Foxp3. Blood 2007; 109:4368–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. A function for interleukin 2 in Foxp3‐expressing regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol 2005; 6:1142–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Chinen T, Kannan AK, Levine AG et al An essential role for the IL‐2 receptor in Treg cell function. Nat Immunol 2016; 17:1322–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Antov A, Yang L, Vig M, Baltimore D, Van Parijs L. Essential role for STAT5 signaling in CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cell homeostasis and the maintenance of self‐tolerance. J Immunol 2003; 171:3435–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Snow JW, Abraham N, Ma MC, Herndier BG, Pastuszak AW, Goldsmith MA. Loss of tolerance and autoimmunity affecting multiple organs in STAT5A/5B‐deficient mice. J Immunol 2003; 171:5042–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Feinerman O, Jentsch G, Tkach KE et al Single‐cell quantification of IL‐2 response by effector and regulatory T cells reveals critical plasticity in immune response. Mol Syst Biol 2010; 6:437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Massagué J. TGFβ signalling in context. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012; 13:616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Oh SA, Li MO. TGF‐β: guardian of T cell function. J Immunol 2013; 191:3973–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W et al Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature 2006; 441:235–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Laurence A, Tato CM, Davidson TS et al Interleukin‐2 signaling via STAT5 constrains T helper 17 cell generation. Immunity 2007; 26:371–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tone Y, Furuuchi K, Kojima Y, Tykocinski ML, Greene MI, Tone M. Smad3 and NFAT cooperate to induce Foxp3 expression through its enhancer. Nat Immunol 2007; 9:194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Schlenner SM, Weigmann B, Ruan Q, Chen Y, von Boehmer H. Smad3 binding to the foxp3 enhancer is dispensable for the development of regulatory T cells with the exception of the gut. J Exp Med 2012; 209:1529–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Durant L, Watford WT, Ramos HL et al Diverse targets of the transcription factor STAT3 contribute to T cell pathogenicity and homeostasis. Immunity 2010; 32:605–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Veldhoen M, Stockinger B. TGFb1, a Jack of all trades: the link with pro‐inflammatory IL‐17‐producing T cells. Trends Immunol 2006;27:358–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Evans HG, Gullick NJ, Kelly S et al In vivo activated monocytes from the site of inflammation in humans specifically promote Th17 responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106:6232–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kitoh A, Ono M, Naoe Y et al Indispensable role of the Runx1‐Cbfbeta transcription complex for in vivo‐suppressive function of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. Immunity 2009; 31:609–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ono M, Yaguchi H, Ohkura N et al Foxp3 controls regulatory T‐cell function by interacting with AML1/Runx1. Nature 2007; 446:685–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Rudra D, Egawa T, Chong MM, Treuting P, Littman DR, Rudensky AY. Runx‐CBFbeta complexes control expression of the transcription factor Foxp3 in regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol 2009; 10:1170–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Bruno L, Mazzarella L, Hoogenkamp M et al Runx proteins regulate Foxp3 expression. J Exp Med 2009; 206:2329–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Polansky JK, Schreiber L, Thelemann C et al Methylation matters: binding of Ets‐1 to the demethylated Foxp3 gene contributes to the stabilization of Foxp3 expression in regulatory T cells. J Mol Med (Berl) 2010; 88:1029–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Shrivastava T, Mino K, Babayeva ND, Baranovskaya OI, Rizzino A, Tahirov TH. Structural basis of Ets1 activation by Runx1. Leukemia 2014; 28:2040–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Bending D, Giannakopoulou E, Lom H, Wedderburn LR. Synovial regulatory T cells occupy a discrete TCR niche in human arthritis and require local signals to stabilize FOXP3 protein expression. J Immunol 2015; 195:5616–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Dias S, D'Amico A, Cretney E et al Effector regulatory T cell differentiation and immune homeostasis depend on the transcription factor myb. Immunity 2017; 46:78–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Liu B, Tahk S, Yee KM, Fan G, Shuai K. The ligase PIAS1 restricts natural regulatory T cell differentiation by epigenetic repression. Science 2010; 330:521–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Josefowicz SZ, Wilson CB, Rudensky AY. Cutting edge: TCR stimulation is sufficient for induction of Foxp3 expression in the absence of DNA methyltransferase 1. J Immunol 2009; 182:6648–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Xing S, Li F, Zeng Z et al Tcf1 and Lef1 transcription factors establish CD8(+) T cell identity through intrinsic HDAC activity. Nat Immunol 2016; 17:695–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Li C, Ebert PJR, Li Q‐J. T cell receptor (TCR) and transforming growth factor β (TGF‐β) signaling converge on DNA (Cytosine‐5)‐methyltransferase to control forkhead box protein 3 (foxp3) locus methylation and inducible regulatory T cell differentiation. J Biol Chem 2013; 288:19127–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Toker A, Engelbert D, Garg G et al Active demethylation of the Foxp3 locus leads to the generation of stable regulatory T cells within the thymus. J Immunol 2013; 190:3180–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Placek K, Hu G, Cui K et al MLL4 prepares the enhancer landscape for Foxp3 induction via chromatin looping. Nat Immunol 2017; 18:1035–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Kitagawa Y, Ohkura N, Kidani Y et al Guidance of regulatory T cell development by Satb1‐dependent super‐enhancer establishment. Nat Immunol 2016; 18:173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Delacher M, Imbusch CD, Weichenhan D et al Genome‐wide DNA‐methylation landscape defines specialization of regulatory T cells in tissues. Nat. Immunol 2017; 18:1160–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Zemmour D, Zilionis R, Kiner E, Klein AM, Mathis D, Benoist C. Single‐cell gene expression reveals a landscape of regulatory T cell phenotypes shaped by the TCR. Nat Immunol 2018; 19:291–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Weiss JM, Bilate AM, Gobert M et al Neuropilin 1 is expressed on thymus‐derived natural regulatory T cells, but not mucosa‐generated induced Foxp3+ T reg cells. J Exp Med 2012; 209:1723–42, S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Thornton AM, Korty PE, Tran DQ et al Expression of Helios, an Ikaros transcription factor family member, differentiates thymic‐derived from peripherally induced Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol 2010; 184:3433–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Szurek E, Cebula A, Wojciech L et al Differences in expression level of helios and neuropilin‐1 do not distinguish thymus‐derived from extrathymically‐induced CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. PLOS ONE 2015; 10:e0141161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]