Abstract

Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) compose a family of multifunctional enzymes involved in the numerous aspects of regulating plant growth, development, and stress response. An in silico genome-wide analysis of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) was performed to identify eighty-five GST genes that were annotated according to their chromosomal location. Segmental duplication contributed more than tandem duplication for the expansion of GST gene family in pepper. All the identified members belong to ten different classes which are highly conserved among Arabidopsis, rice, tomato and potato counterparts indicating the pre-dicot-monocot split diversification of GST classes. Gene structure, protein domain, and motif organization were found to be notably conserved over the distinct phylogenetic groups, which demonstrated the evolutionary significant role of each class. Expression of most of the CaGST transcripts as well as the total pepper GST activity was found to be significantly up-regulated in response to cold, heat, drought, salinity and osmotic stress conditions. Presence of various hormone and stress-responsive cis-elements on most of the putative CaGST promoter regions could be directly correlated with the alteration of their transcripts. All these findings might provide opportunities for future functional validation of this important gene family in pepper.

Subject terms: Plant evolution, Abiotic

Introduction

Cellular detoxification is an elementary biological process in all living organisms including animals, plants, and microorganisms. It provides protection against different environmental noxious agents as well as reactive oxygen species (ROS) formed from different metabolic pathways, to ensure the optimum cellular condition for the growth and survival1. After the conversion of toxic components into reactive electrophiles by cytochrome P450s, these reactive molecules are subsequently transformed by the exertion of phase II enzymes, namely Glutathione S-transferase (GST) for the final degradation process2. GSTs are metabolic isozymes that form a complex family with versatile functions in plants3. Among its myriad functions, this family mainly works as a detoxification route in plants by conjugating glutathione (γ-Glu-Cys-Gly) to a diverse range of hydrophobic, electrophilic, xenobiotic compounds and redox buffering to form a soluble S-glutathionylated (R-SG) products4. This gene family possesses a high transcript abundance in most of the tissues and thus, act as a biomarker for the detection and monitoring of organ/tissue damage both in plants and animals1,5.

GST genes are abundantly found in animals, plants and even in some prokaryotes6. The family consists of cytosolic, mitochondrial and microsomal GSTs. Among them, the mitochondrial and microsomal members showed significant differences in their sequence and biosynthesis process as compared with the cytosolic GSTs7. Classification of the plant soluble GST members is evaluated based on the sequence conservance, genomic organization, kinetic and physiochemical properties, and immunological cross relativeness8. There are fourteen classes of GSTs found so far in plants, including tau (U), phi (F), lambda (L), dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR), theta (T), zeta (Z), eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1B- γ subunit (EF1Bγ), tetra-chloro hydroquinone dehalogenase (TCHQD), microsomal prostaglandin E-synthase type 2 (mPGES-2), glutathionyl hydroquinone reductase (GHR), metaxin, Ure2p, hemerythrin (H) and iota (I)8. The first four of them (tau, phi, lambda, DHAR) and recently identified two new classes (hemerythrin and iota) are highly plant-specific8.

Tau and phi classes have drawn much interest as they are the most abundant classes in plants and perform a major role in the xenobiotics metabolism9. Theta-class of GST is mainly involved in the oxidative metabolism and zeta GSTs convert maleylacetoacetate to fumarylacetoacetate in a glutathione-dependent reaction10. The lambda and DHAR function as thiol transferases by replacing its serine residue to cysteine11,12. The five other classes of GST, such as mPGES-2, GHR, metaxin, hemerythrin, and iota possess cysteine in their active site. Catalytic mechanism of Ure2p is mediated by the asparagine residue which plays a key role in the glutathione stabilization13. However, the catalytic nature of the EF1Bγ class is not clear to date8.

Previous studies have emphasized the involvement of GSTs in various abiotic stress response14,15. The tau class GSTs perform a potential role against the oxidative damages, chemical toxicity, and physical stress agents16,17. Over-expression of TaGSTU1B and TaGSTF6 genes in wheat enhanced tolerance against drought18. Ectopic expression of a rice tau glutathione s-transferase, OsGSTU4 improves tolerance to salinity and oxidative stresses in Arabidopsis by up-regulating several stress responsive and cellular detoxifying genes19. Similarly, ectopic expression of stress-inducible GmGSTU4, CsGSTU1 and CsGSTU2 transcripts in transgenic tobacco plants enhanced tolerance against diphenyl ether herbicide, salinity, and drought stresses20,21.

Genome-wide analysis of GST gene family had been carried out in various plant species, and identified 55 members in Arabidopsis15, 84 in barley22, 65 in Brassica oleracea23, 49 in G. arboretum and 59 in G. raimondii24, 27 in Japanese larch25, 42 in maize26, 62 in China-pear27, 90 in potato28, 37 in Physcomitrella patens29, 81 in populus30, 79 in rice14, 101 in soybean31, 14 in sunflower32, 23 in sweet orange33, 73 in Medicago34, 49 in Capsella35 and 90 in tomato36. Although detailed genome sequence information of Capsicum annuum is publicly available, genome-wide analysis of GST gene family was not performed yet. Pepper has a relatively large genome size of 3.48 Gb with a life cycle of around 95 days37. In this study, a comprehensive genome-wide analysis of GSTs has been accomplished in Capsicum annuum and identified a total of 85 members. Analyses of chromosomal position, physiochemical characteristics, conserved motifs, and subcellular localization of these identified members showed a great variation among themselves. An evolutionary trajectory is drawn between pepper and one of its closest relative tomato, based on their class wise sequence analysis. Furthermore, expression patterns of all the identified genes and total GST activity were analyzed under different developmental and environmental conditions. This study will facilitate a door for the researchers to identify the specific gene/member of the family for crop improvement and stress management.

Results

Identification and nomenclature of GST genes in Capsicum annuum

Eighty-five full length genes encoding putative GST proteins were identified in C. annuum and classified into ten classes: tau, phi, theta, zeta, lambda, EF1Bγ, DHAR, TCHQD, MGST, and GHR. The tau and phi classes are found to be the most abundant with 59 and 6 members, respectively (Table 1). The length of the CaGST transcripts ranged from 306 bp (CaGSTU29) to 14430 bp (CaGHR1), whereas the deduced proteins are 101 to 361 amino acids long. The molecular weight (MW) of the CaGST proteins vary from the lowest 11.62 kDa (CaGSTU29) to the highest of 74.94 kDa (CaGSTF5). However, the predicted pI values ranged from 5 to 9. The average length, MW, and pI of the CaGST proteins were found to be 230 aa, 26.3 kDa and 6.5, respectively (Table 1). Most of the CaGST proteins were predicted to be localized in the cytoplasm, followed by chloroplast, mitochondria, nucleus, extracellular space, and plasma membrane. Secondary structure analysis showed the presence of a higher percentage of α-helix in CaGST proteins as compared with β-sheets (Table S1). The percentage of the extended strand was fluctuating widely among the CaGST proteins, in a range of 10 to 28%. Glycosylation analysis showed that 40 CaGST proteins have a potential N-glycosylation site, whereas CaGSTF5 and CaGHR1 possess the highest number of predicted glycosylation site with seven and five, respectively (Table S2).

Table 1.

List of identified GST genes in pepper along with their detailed genomic and proteomic information.

| Sl no | Gene Name | Locus ID | CDS coordinate(5′-3′) | Strand | Gene (bp) | Protein (aa) | MW (kDa) | pI | Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CaGSTU1 | Capana00g001895 | 438859152–438859976 | + | 825 | 229 | 26.25 | 6.14 | Cya,b |

| 2 | CaGSTU2 | Capana00g002164 | 455860084–455861271 | + | 1188 | 225 | 26.00 | 5.53 | Cya,b |

| 3 | CaGSTU3 | Capana00g003105 | 524690584–524692284 | − | 1701 | 203 | 23.67 | 8.46 | Cya,b |

| 4 | CaGSTU4 | Capana00g003106 | 524702849–524704044 | − | 1196 | 219 | 25.56 | 6.60 | Cya,b |

| 5 | CaGSTU5 | Capana00g004478 | 647297751–647300086 | − | 2336 | 221 | 25.12 | 5.21 | Cya, Cpb |

| 6 | CaGSTU6 | Capana00g004596 | 657125404–657128170 | + | 2767 | 222 | 25.73 | 5.59 | Cya, Cyb |

| 7 | CaGSTU7 | Capana00g004598 | 657374139–657375389 | − | 1251 | 220 | 25.34 | 5.75 | Cya,b |

| 8 | CaGSTU8 | Capana00g004621 | 659428697–659429026 | + | 330 | 109 | 12.84 | 6.97 | Cya,b, Mta, Cpa |

| 9 | CaGSTU9 | Capana00g004665 | 665401358–665402749 | − | 1392 | 224 | 25.87 | 5.57 | Cya, Cpb |

| 10 | CaGSTU10 | Capana01g002551 | 166700570–166702635 | + | 2066 | 221 | 25.08 | 5.08 | Cya, Nub |

| 11 | CaGSTU11 | Capana01g003292 | 222778803–222779584 | − | 782 | 225 | 25.63 | 6.33 | Cya,b |

| 12 | CaGSTU12 | Capana01g003296 | 222806252–222809195 | − | 2944 | 222 | 25.91 | 6.00 | Cya,b |

| 13 | CaGSTU13 | Capana02g000947 | 103858121–103858901 | − | 781 | 153 | 17.40 | 5.57 | Cya,b |

| 14 | CaGSTU14 | Capana02g000948 | 103899028–103899345 | − | 318 | 105 | 11.98 | 9.13 | Cya, Cpa, Nub |

| 15 | CaGSTU15 | Capana02g000950 | 104101699–104102578 | + | 880 | 225 | 26.05 | 5.36 | Cya, Cpb |

| 16 | CaGSTU16 | Capana02g000952 | 104250329–104251764 | + | 1436 | 224 | 25.67 | 5.40 | Cya,b |

| 17 | CaGSTU17 | Capana03g000768 | 11322594–11323373 | − | 780 | 212 | 24.43 | 5.44 | Cya, Cpb |

| 18 | CaGSTU18 | Capana03g000769 | 11362575–11363976 | − | 1402 | 233 | 27.12 | 5.29 | Cya,b |

| 19 | CaGSTU19 | Capana03g004402 | 253298052–253300358 | + | 2307 | 222 | 25.91 | 5.00 | Cya |

| 20 | CaGSTU20 | Capana03g004562 | 257827721–257828950 | − | 1230 | 225 | 25.75 | 6.10 | Cya,b |

| 21 | CaGSTU21 | Capana03g004565 | 258031244–258032469 | + | 1226 | 225 | 26.05 | 6.25 | Cya,b |

| 22 | CaGSTU22 | Capana03g004566 | 258056794–258057997 | + | 1204 | 225 | 25.93 | 7.02 | Cya,b |

| 23 | CaGSTU23 | Capana06g002861 | 210286274–210287439 | − | 1166 | 220 | 25.36 | 5.53 | Cya,b |

| 24 | CaGSTU24 | Capana07g002003 | 210859245–210865929 | + | 6685 | 220 | 25.49 | 5.89 | Cya,b |

| 25 | CaGSTU25 | Capana07g002004 | 210867066–210867991 | + | 926 | 222 | 25.60 | 5.79 | Cya,b |

| 26 | CaGSTU26 | Capana07g002005 | 210902595–210903564 | + | 970 | 175 | 20.42 | 6.84 | Cya,b, Cpa |

| 27 | CaGSTU27 | Capana07g002006 | 210941269–210948401 | + | 7133 | 282 | 32.96 | 8.35 | Cya,b |

| 28 | CaGSTU28 | Capana07g002007 | 210981175–210982949 | + | 630 | 209 | 24.34 | 8.08 | Cya,b |

| 29 | CaGSTU29 | Capana07g002008 | 211057582–211057887 | + | 306 | 101 | 11.62 | 5.14 | Cya,b |

| 30 | CaGSTU30 | Capana07g002009 | 211066612–211068955 | + | 2344 | 238 | 27.61 | 6.25 | Cya,b |

| 31 | CaGSTU31 | Capana07g002010 | 211152285–211153567 | + | 1223 | 220 | 25.54 | 5.78 | Cya,b |

| 32 | CaGSTU32 | Capana07g002011 | 211155192–211156505 | − | 1314 | 219 | 25.32 | 6.84 | Cya,b |

| 33 | CaGSTU33 | Capana07g002012 | 211160558–211161672 | − | 1115 | 203 | 23.75 | 7.00 | Cya,b |

| 34 | CaGSTU34 | Capana08g001515 | 132057487–132058584 | + | 1098 | 226 | 25.76 | 5.38 | Cya,b |

| 35 | CaGSTU35 | Capana08g001518 | 132082843–132083882 | + | 1040 | 202 | 22.88 | 5.36 | Cya, Cpa |

| 36 | CaGSTU36 | Capana08g001520 | 132086808–132087750 | + | 943 | 181 | 20.61 | 5.11 | Cya,b, Cpa |

| 37 | CaGSTU37 | Capana09g001740 | 199536703–199537891 | + | 1189 | 223 | 25.30 | 5.30 | Cya, Cpb |

| 38 | CaGSTU38 | Capana09g001741 | 200130618–200131846 | + | 1229 | 220 | 25.04 | 5.48 | Cya, Cpb |

| 39 | CaGSTU39 | Capana09g001742 | 200167723–200169649 | + | 1927 | 224 | 26.36 | 6.77 | Cya, Nub |

| 40 | CaGSTU40 | Capana09g001760 | 202017261–202018643 | + | 1383 | 217 | 25.05 | 5.28 | Cya,b |

| 41 | CaGSTU41 | Capana09g001761 | 202086834–202088344 | + | 1511 | 220 | 24.85 | 5.41 | Cya, Cpb |

| 42 | CaGSTU42 | Capana09g001762 | 202236152–202237088 | + | 937 | 220 | 25.45 | 5.12 | Cya, Cpb |

| 43 | CaGSTU43 | Capana09g001763 | 202238222–202239079 | + | 858 | 154 | 17.67 | 5.12 | Cya, Mta |

| 44 | CaGSTU44 | Capana09g001764 | 202383049–202384214 | + | 1166 | 220 | 25.38 | 5.53 | Cya,b |

| 45 | CaGSTU45 | Capana09g001858 | 213200912–213201949 | + | 1038 | 217 | 25.28 | 5.38 | Cya, Cpb |

| 46 | CaGSTU46 | Capana09g001859 | 213228499–213229454 | − | 956 | 219 | 24.86 | 5.87 | Cya,b |

| 47 | CaGSTU47 | Capana09g001860 | 213238117–213239430 | − | 1314 | 221 | 25.19 | 5.23 | Cya, Nub |

| 48 | CaGSTU48 | Capana09g001861 | 213240773–213241709 | + | 937 | 224 | 25.76 | 5.58 | Cya, Cpb |

| 49 | CaGSTU49 | Capana09g001862 | 213303661–213304284 | + | 624 | 143 | 16.62 | 4.84 | Cya, Mta |

| 50 | CaGSTU50 | Capana09g002045 | 226590245–226590574 | + | 330 | 109 | 13.06 | 8.78 | Cya,b, Mta |

| 51 | CaGSTU51 | Capana11g001524 | 178109400–178111728 | + | 2329 | 231 | 25.76 | 6.18 | Cya, Cpa,b |

| 52 | CaGSTU52 | Capana11g001525 | 178112748–178114176 | + | 1429 | 215 | 23.85 | 8.88 | Cya, Cpa,b |

| 53 | CaGSTU53 | Capana11g001528 | 178187645–178188768 | + | 1124 | 220 | 24.84 | 6.75 | Cya, Cpa,b |

| 54 | CaGSTU54 | Capana11g001532 | 178455711–178456697 | + | 987 | 229 | 26.20 | 6.76 | Cya, Cpb |

| 55 | CaGSTU55 | Capana11g001533 | 178457971–178458582 | + | 612 | 203 | 23.42 | 6.31 | Pma, Ecb |

| 56 | CaGSTU56 | Capana11g001535 | 178483866–178484900 | + | 1035 | 229 | 26.01 | 5.57 | Cya, Cpb |

| 57 | CaGSTU57 | Capana11g001536 | 178558594–178560496 | − | 1903 | 229 | 26.25 | 5.45 | Cya, Cpb |

| 58 | CaGSTU58 | Capana11g001537 | 178588610–178590596 | + | 1987 | 229 | 26.13 | 5.62 | Cya, Cpb |

| 59 | CaGSTU59 | Capana12g000354 | 7186608–7188114 | + | 1507 | 219 | 25.57 | 5.47 | Cya, Nub |

| 60 | CaGSTF1 | Capana02g002285 | 142882377–142883807 | + | 1431 | 228 | 26.02 | 6.09 | Cya, Cpb |

| 61 | CaGSTF2 | Capana03g003600 | 230428836–230430376 | + | 1541 | 213 | 24.19 | 5.69 | Cya, Cpb |

| 62 | CaGSTF3 | Capana06g003058 | 218203021–218205366 | + | 2346 | 213 | 23.76 | 6.39 | Cya, Cpb |

| 63 | CaGSTF4 | Capana06g001819 | 54683346–54684364 | − | 1019 | 251 | 29.29 | 8.68 | Cya,b, Mta, Nua |

| 64 | CaGSTF5 | Capana12g000609 | 14792240–14802489 | + | 10250 | 654 | 74.94 | 7.13 | Pma, Cyb |

| 65 | CaGSTF6 | Capana12g000612 | 14873894–14878274 | + | 4381 | 252 | 28.64 | 5.26 | Cya, Eca, Cpb |

| 66 | CaGSTT1 | Capana01g000218 | 3161948–3164992 | + | 3045 | 186 | 21.15 | 9.74 | Mta, Nua, Cyb |

| 67 | CaGSTT2 | Capana01g000219 | 3169497–3173899 | + | 4403 | 250 | 28.34 | 9.25 | Cya, Mta, Nua |

| 68 | CaGSTT3 | Capana01g000221 | 3200545–3205818 | + | 5274 | 241 | 27.33 | 9.26 | Cya,b, Mta |

| 69 | CaGSTT4 | Capana12g001178 | 52439179–52442473 | − | 3295 | 235 | 26.46 | 6.45 | Cya, Cpb |

| 70 | CaGSTZ1 | Capana01g001395 | 45340308–45347371 | − | 7064 | 283 | 32.48 | 8.34 | Mta, Cya, Cpb,c |

| 71 | CaGSTZ2 | Capana12g000896 | 32868383–32869334 | + | 952 | 107 | 12.47 | 5.01 | Pma, Cyb |

| 72 | CaGSTL1 | Capana05g000544 | 14609977–14614464 | + | 4488 | 314 | 35.45 | 8.71 | Cpa,b,c |

| 73 | CaGSTL2 | Capana09g001864 | 213395287–213400333 | + | 5047 | 239 | 27.75 | 5.57 | Cya,b |

| 74 | CaGSTL3 | Capana10g001792 | 183887466–183889739 | − | 2274 | 222 | 25.80 | 5.24 | Cya,b |

| 75 | CaGSTL4 | Capana10g001806 | 186021678–186025506 | − | 3829 | 253 | 29.10 | 5.75 | Cya,b, Mta |

| 76 | CaEF1Bɣ1 | Capana11g000124 | 3480968–3485480 | − | 4513 | 414 | 46.83 | 5.65 | Cya, Cpb |

| 77 | CaEF1Bɣ2 | Capana08g000330 | 43923121–43924032 | − | 912 | 204 | 23.47 | 8.67 | Cya, Nua |

| 78 | CaDHAR1 | Capana05g000799 | 31400365–31405449 | + | 5085 | 295 | 32.75 | 8.33 | Mta, Cpa,b,c |

| 79 | CaDHAR2 | Capana05g002401 | 214455819–214460536 | − | 4718 | 212 | 23.57 | 5.88 | Cya,b |

| 80 | CaTCHQD | Capana00g004998 | 686182991–686184172 | + | 1182 | 268 | 31.64 | 9.06 | Mta, Cya |

| 81 | CaMGST1 | Capana02g002296 | 143033395–143035039 | + | 1645 | 144 | 16.38 | 9.15 | Pma |

| 82 | CaMGST2 | Capana04g000166 | 2049728–2054459 | − | 4732 | 323 | 36.21 | 9.02 | Cpa,c |

| 83 | CaGHR1 | Capana02g001236 | 116162258–116176687 | + | 14430 | 361 | 41.43 | 6.80 | Mta, Nua, Cpc |

| 84 | CaGHR2 | Capana02g000926 | 102853919–102854627 | − | 709 | 123 | 13.73 | 4.37 | Nua, Cya |

| 85 | CaGHR3 | Capana06g000146 | 1927452–1929409 | + | 1958 | 373 | 41.82 | 6.61 | Cpa,c |

Abbreviations- CDS, coding DNA Sequence; MW, Molecular Weight; pI, Isoelectric point; bp, base pair; aa, amino acid; kDa, kilodalton; Cp, Chloroplast; Ec, Extracellular; Cy, Cytoplasm; Mt, Mitochondria; Nu, Nucleus; Pm, Plasma-membrane.

aLocalization prediction by CELLO v.2.5 (http://cello.life.nctu.edu.tw/).

bLocalization prediction by pSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/).

cChloroplast localization signal confirmed by ChloroP (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ChloroP/).

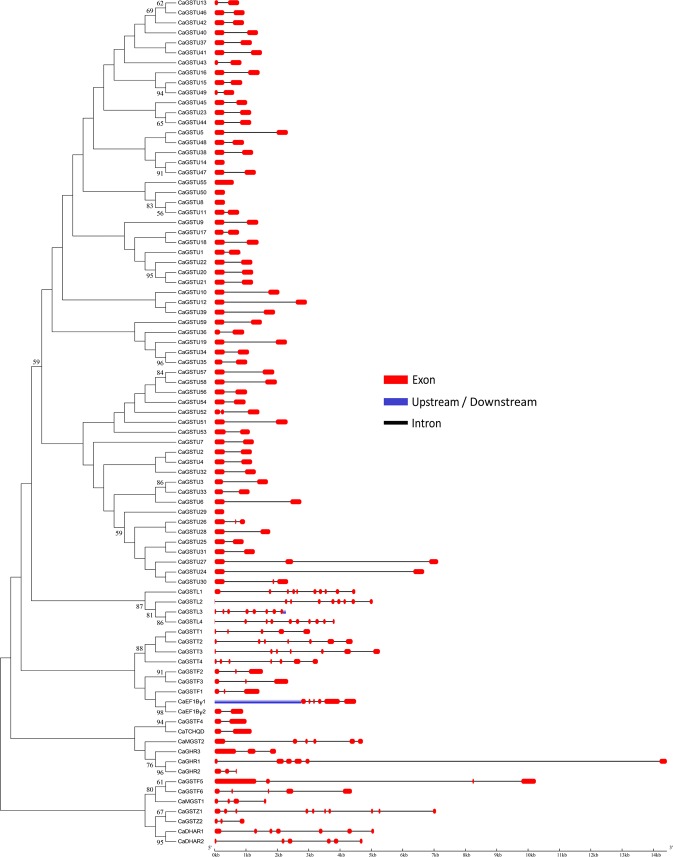

Genomic organization of the pepper GST gene family

All the CaGST genes are distributed randomly and unevenly in all the 13 chromosomes of pepper (Fig. S1). Chromosome 9 is the most densely populated with fifteen genes (17.6%), followed by ten genes each in chromosome 7 and 0, then nine genes each in chromosome 2 and 11 (Fig. S1). A total of sixteen gene clusters were observed on 12 different chromosomes. Among these clusters, eleven were formed among tau members, one each was for the theta and GHR cluster. Twenty-four sets of CaGST proteins appeared to be ≥80% similar, that indicates the possible gene duplication events among these genes (Table S3). A maximum of nine duplicated GST genes were located in chromosome 7, followed by six in chromosome 9 and five in chromosome 11. Out of the twenty-four gene pairs, twelve pairs were found as tandemly duplicated, whereas rest twelve pairs appeared as segmentally duplicated. Furthermore, the substitution rate of non-synonymous (dN) and synonymous (dS) ratios were calculated to investigate the selective constraints on the duplicated CaGST gene pairs, where values >1, <1, and equal to 1 implies positive selection, purifying selection, and neutral selection, respectively. All the identified duplicated CaGST gene pairs showed the dN/dS value less than 0.7, signifying the influence of purifying selection behind the evolution of these gene pairs. Moreover, the estimated divergence time of the duplicated gene pairs varies from 1.18 Mya to 17.84 Mya (Table S3). Identification of the exon-intron organization of 85 CaGST genes revealed a group-specific exon/intron patterns within each GST class. A similar type of exon/intron number and length were notable in the phylogenetically related members (Fig. 1). The tau-class CaGSTs typically contained one/two exons, while phi GST genes contained two to five exons in its gene structure (Fig. 1). CaGSTZ1, CaGSTL1, and CaGSTL4 contained the maximum number of nine introns and ten exons, followed by 9 exons in CaGSTL2, 8 exons in CaGSTL3, 7 exons in CaGSTT2, CaGSTT3, CaGSTT4 and CaDHAR1 (Fig. 1). An interesting pattern of intron distribution was observed among the putative paralogous members. Most of the paralogs showed same number and similar sized intron such as gene cluster of CaGSTU13, 46, 42 and CaGSTU23, 44, 45; while some of them showed intron gain/loss phenomenon as compared with their paralogs (CaGSTU26 and 30, CaGSTL3 and 4, CaEF1Bγ1 and 2, CaGHR1 and 2, and CaDHAR1 and 2). Few of them showed partial deletion of exon such as CaGSTU54 and 56 as compared with their two paralogs- CaGSTU57 and 58 (Fig. S2A), while some others showed exon duplication such as CaGSTU14 and CaGSTU47 (Fig. S2B).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic and Structural analysis of CaGST genes. (A) Number at each node in the phylogenetic tree represents the bootstrap value higher than 50. The different class of GST genes forms separate clades. (B) The schematic diagram represents the gene structure of all 85 CaGST genes identified in this study. Exons are shown as red boxes; introns are shown as black lines, and the upstream/downstream regions are shown as blue boxes. The relative size of the full transcript, intron, exon, and upstream region could be inferred from the supplied scale in kilobase pair (kb).

Domain architecture analysis showed that 60 out of 85 CaGST proteins contained two conserved GST domains, namely, N-terminal and C-terminal (Fig. S3). Only one N-terminal domain present in 22 CaGSTs, whereas only C-terminal domain present in 3 CaGST proteins (CaGSTU13, CaGSTU43, and CaGHR2). Additional distinct EF1Bγ domain (PF00736) was found to be present in the CaEF1Bγ1 and CaEF1Bγ2 proteins, while the MAPEG domain (PF01124) was present only in CaMGST1 protein. Analysis of conserved motifs of CaGST proteins identified ten distinct motifs (Table S4, and Fig. S4). Among them, four motifs are located in the N-terminal GST domain, while the rest six reside in the C-terminal GST domain of the proteins. Motif3 is found to be present in the N-terminal of 65 proteins; followed by motif 1, motif 4, motif 2, motif 7, and motif 5 with 58, 57, 55, 53 and 51 sites, respectively. Interestingly, lambda class specific pattern was shown by motif 9, while motif 10 was present only in four tau class members (CaGSTU1, CaGSTU20, CaGSTU21, and CaGSTU22). Among others, motif 6 and 8 were present in 44 and 16 CaGSTs, respectively. The lowest number of one motif (either motif 4 or 8) is present in CaGSTZ2, CaGSTL2, CaEF1Bγ2, CaMGST1, CaGHR2, and CaGHR3.

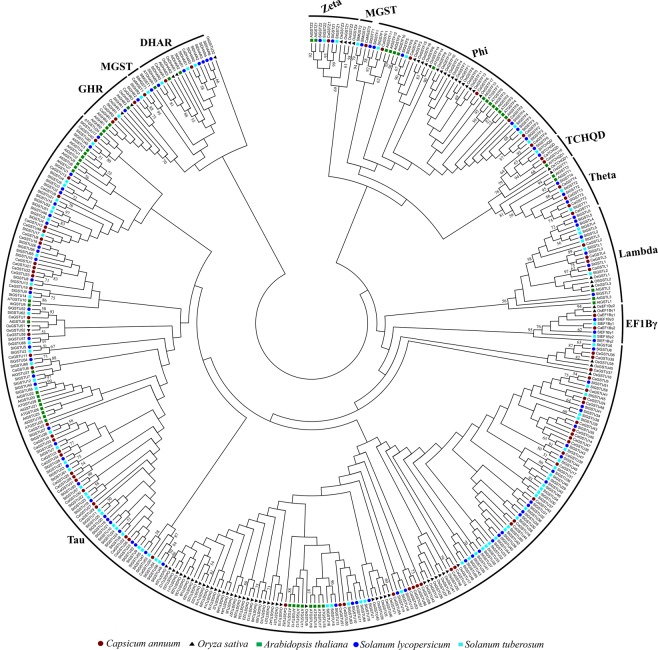

Phylogenetic analysis of GST proteins

The evolutionary relationship of GST family members was predicted by comparing them to different plant species. A total number of 401 full length GST protein sequences from five different plant species- pepper, Arabidopsis, rice, tomato, and potato were aligned to create an unrooted maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2). All these CaGST proteins were found to be closely associated with an individual class of GSTs. Most classes formed a monophyletic group with very few exceptions of OsGSTU32, CaGSTU10, and SlGSTT1 (Fig. 2). The tree clearly suggested that the largest and most abundant class of GST is tau (brown circle) with 59, 52, 28, 57 and 66 members in pepper, rice, Arabidopsis, tomato, and potato; respectively. All these tau members are distributed in 6 different small clades under a large superclade, which indicates the presence of internal variation among these tau members. Similarly, the second largest clade is formed by the phi members with a green rectangle. The clustering of same classes of GST from five plant species demonstrates that the presence of all these GST individual classes during the divergence of plants followed a species-specific gene duplication. The major divergences that divided the family into 10 individual classes might occur in the common ancestor of all the investigated species.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of GST proteins. GST proteins from five species- pepper, tomato, potato, Arabidopsis, and rice were used to construct an unrooted phylogenetic tree using MEGA Maximum-likelihood method with 1000 bootstraps. GST members from tau, lambda, zeta, DHAR, theta, GHR, TCHQD, phi, MGST, EF1Bγ classes were marked with red, green, cyan, blue, violet, gray, coral, yellow, pink, royal blue; respectively. Members of each class formed different clades with few exceptions.

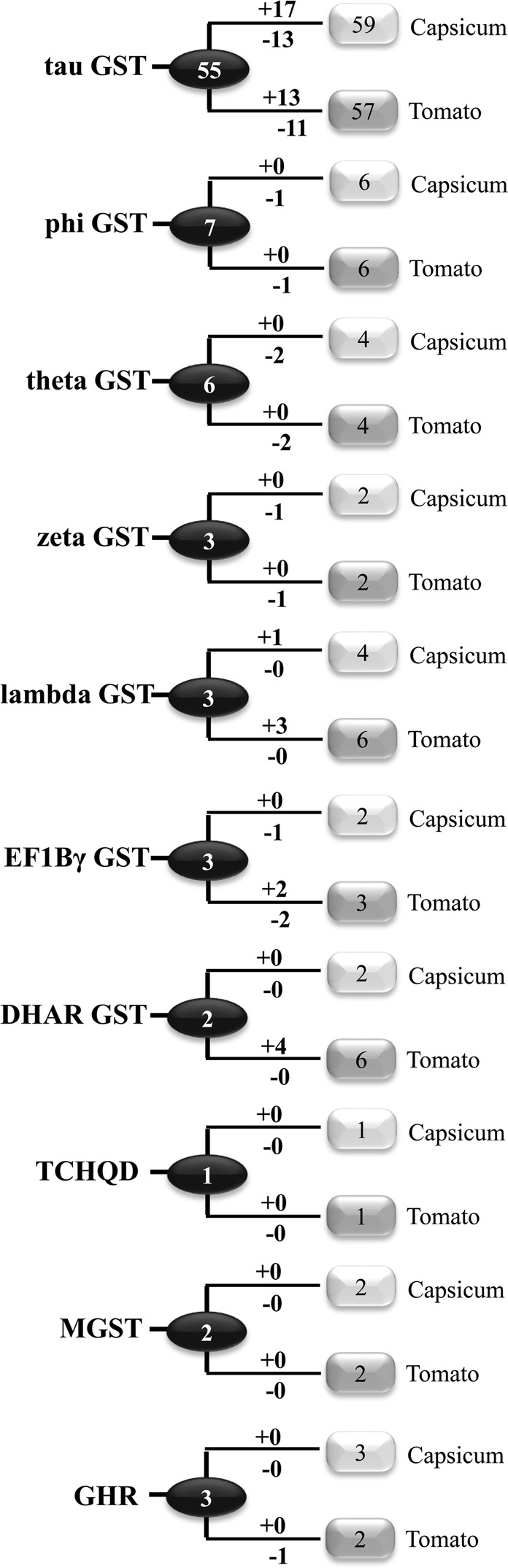

Molecular evolution of Capsicum and tomato GST family

To investigate the lineage-specific expansion of GST genes in Capsicum and tomato genome, a phylogenetic analysis was performed using the GST protein sequences from Capsicum and tomato. A total of 85 Capsicum and 90 tomato GSTs fell into ten distinct classes. The divergence point between Capsicum and tomato were labeled with circles on certain specific nodes of the phylogenetic tree that represents the most recent common ancestral (MRCA) genes before the split (Figs S5–S10). Most of the MRCA have a member from both the species, while some of them have representation from either Capsicum or tomato, indicating a subsequent loss in tomato and Capsicum genome, respectively. There were at least 55 MRCA for tau GST genes between Capsicum and tomato out of a total of 59 and 57 members, respectively (Fig. 3). After the split, Capsicum gained 17 genes and lost 13 genes, resulting in the 59 tau GST genes; while tomato gained 13 genes and lost 11 genes, resulting in 57 tau genes. For phi GST, there are at least 7 MRCA between Capsicum and tomato (Fig. 3). After the split, both of them lost one member without any gain, resulting 6 phi members in each species (Fig. 3). Similarly, two genes have been lost from 6 MRCA of theta GST to result in 4 existing members in each species.

Figure 3.

Copy number variation between Capsicum and tomato GST genes. The numbers presented inside the circles and rectangles represent the numbers of GST genes as common ancestral and species-specific, respectively. Numbers on the branches with plus and minus symbols represent the numbers of gene gains and losses, respectively throughout the evolution between these two species. The light gray boxes represent Capsicum, while dark gray boxes symbolize tomato.

For zeta, lambda, EF1Bγ, and GHR GSTs, there are at least three ancestral genes in the MRCA analysis of Capsicum and tomato (Fig. 3). After the split, both Capsicum and tomato lost one zeta member without any gain; no loss with one gain for Capsicum and three gain for tomato lambda GST; one loss without gain for Capsicum and two loss with two gain for tomato EF1Bγ GST; and no loss/gain for Capsicum and one loss without any gain for tomato GHR GST genes. For DHAR GST, the MRCA of Capsicum and tomato had at least two ancestral members (Fig. 3). After the split, there was no gain/loss event in Capsicum, while four genes have been gained by tomato. For TCHQD GST and MGST classes, there were no identifiable gene gain or loss events after the split of these two species (Fig. 3).

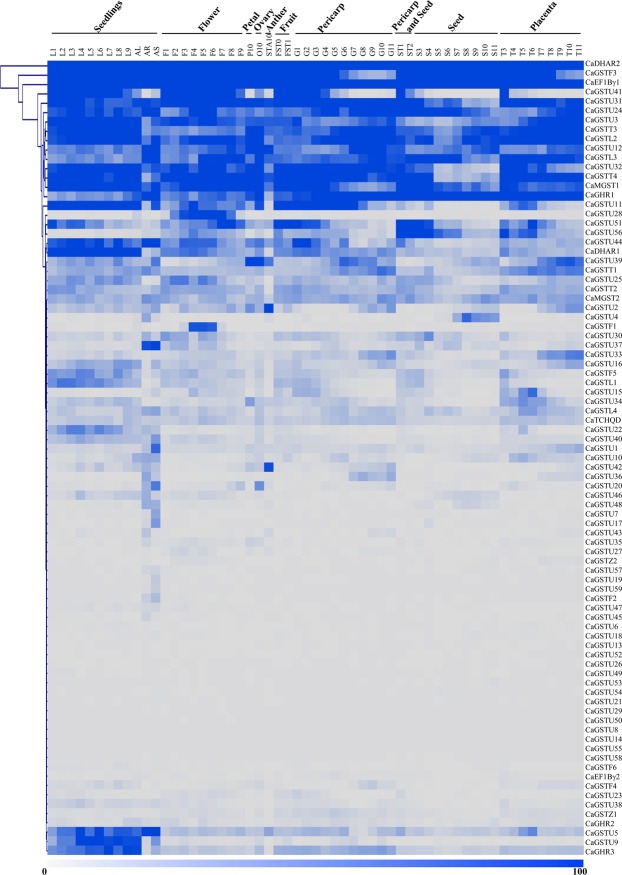

Expression analysis of CaGST transcripts in different tissues

To investigate the putative roles of CaGST genes in C. annuum growth and development, expression of all the identified CaGST genes were analyzed in the 57 different tissues and organs based on the RNA-seq data. All these tissues could be broadly represented into nine major organs/stages: seedlings, flower, petal, ovary, anther, fruit, pericarp, seed, and placenta. The analysis revealed a differential pattern of expression for different CaGST transcripts depending on the type of tissues and organs (Fig. 4). Based on the differential expression patterns, all these genes could be classified into three groups: a) Some CaGSTs showed extremely low levels of expression in almost all tissues and organs, b) Some CaGSTs exhibited low to medium levels of expression among different organs/tissues, and c) Some were highly expressive across all the tissues of the entire life cycle. Among all, CaDHAR2 and CaEF1Bγ1 showed the maximum level of expression in all the tissues, while other members of this clade such as CaGSTF3, CaGSTU31, CaGSTU24, CaGSTU3, CaGSTT3, CaGSTL2, CaGSTU12, CaGSTL3, CaGSTU32, CaGSTT4, CaMGST1, and CaGHR1 exhibited a high level of expression in most of the tissues (Fig. 4). Notably, two clusters of GST genes from CaGSTU51 to CaDHAR1 and from CaGSTU5 to CaGHR3 (Fig. 4) maintained a medium to high levels of expression in all the analyzed tissues. Interestingly, some of the members showed a highly tissue-specific expression, such as CaGSTU41 showed a low level of expression in pericarp, seed and placental otherwise the level is high in other tissues; CaGSTU28 and CaGSTF1 possessed only flower-specific expression; expression of CaGSTU56 raised significantly in seed and placenta; and the cluster of CaGSTU5 to CaGHR3 showed a high level of seedling specific expression (Fig. 4). Thus, different GST transcripts might have different developmental and tissue-specific regulation to maintain their specific localized or ubiquitous function.

Figure 4.

Expression profiling of CaGST genes at different anatomical tissues. Expression of all the identified CaGST transcripts was analyzed in 57 developmentally diverse tissues using the RNA-seq data. All these tissues could be categorized into nine major stages, such as seedlings, flower, petal, ovary, anther, fruit, pericarp, seed, and placenta. Heatmap with hierarchical clustering was performed using the expression values in MeV software package with Manhattan correlation. The highest level of expression is represented by dark blue (100%), while the low level is presented as white (0%). Thus, the intensity of the color in the heatmap is directly proportioned to the transcript abundance of each member.

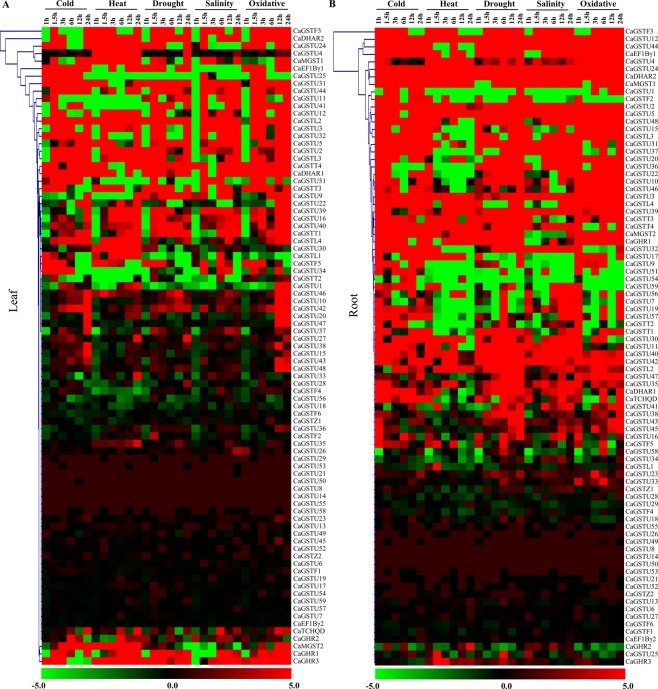

Transcript analysis of CaGSTs in response to various abiotic stresses

To identify the abiotic stress-responsiveness, expression profiling of all CaGST transcripts were further analyzed in response to five different abiotic stresses viz. cold, heat, drought, salinity and osmotic using the Illumina RNA-Seq data (Fig. 5). Transcriptome profiling was performed in the leaf and root tissue of hot pepper at six different time points such as 1 h, 1.5 h, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h. Most of the genes showed a different level of upregulation with few downregulation events. As compared with the leaf samples (Fig. 5A), the genes showed more upregulation in the root samples (Fig. 5B) as root is one of the first organs to perceive the adverse conditions. A large cluster of genes (CaGSTU55 to CaEF1Bγ2) showed a minimum alteration in response to all these stresses in both the leaf and root tissues. Two clusters of genes; one from CaGSTF3 to CaMGST1, and another from CaGSTU2 to CaGSTU48, showed the maximum upregulation in the root against all these stresses (Fig. 5B), while there is no such unique pattern of upregulation in the leaf (Fig. 5A). Moreover, there are a few stress-specific transcript alteration events in the root (Fig. 5B) such as CaGSTU1 showed cold and oxidative stress-specific upregulation; a cluster of CaGSTU15 to CaGSTU46 showed heat-specific downregulation; and CaGSTF2, CaGSTU51, and CaGSTU54 exhibited cold-specific upregulation. Likewise, a cold specific upregulation for CaGSTU25 and CaGSTU34; and drought and salinity specific upregulation for CaGSTU11 and CaGSTU44 was observed in the leaf samples (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Alteration of CaGST transcripts in various abiotic stresses. Expression of all 85 CaGST transcripts was analyzed from the leaf (A) and root (B) samples treated with five major abiotic stresses, such as cold, heat, drought, salinity and oxidative. Relative fold change of transcript abundance in seven different time points of each stress (1 h, 1.5 h, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h) was plotted with MeV software package. The color scale, depicted at the down of each heatmap, represents the intensity of alterations where green color indicates downregulation and red indicates upregulation.

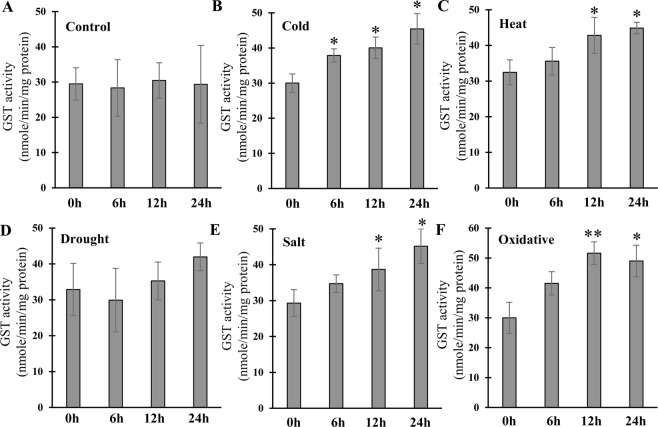

Stress-responsive alteration of total GST activity

In order to validate the abiotic stress specific up-regulation of the majority of CaGST transcripts, the total GST activity was measured in response to the same abiotic stress conditions- cold, heat, drought, salinity, and oxidative; and compared with the respective untreated control conditions (Fig. 6). As shown in Fig. 6, a strong positive induction of GST activity was observed in response to all these stress treatments. GST enzyme activity enhanced significantly in response to heat, cold, salt, and oxidative stresses as compared with their untreated (0 h) sample (Fig. 6). A gradual enhancement of GST activity with time was observed for heat, cold and salt stresses, while total GST activity under oxidative stress reached a maximum level within 12 h of stress imposement, and maintained the level until 24 h observation period (Fig. 6F). Among all these stresses, drought showed minimum induction with a slow rate over the time of 24 h (Fig. 6D). However, the level of total GST activity in the untreated control sample remains almost similar within the 24 h experimental period (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Measurement of total GST activity in response to various abiotic stresses. Total GST enzyme activity was measured in response to various abiotic stresses such as cold, heat, drought, salinity, and oxidative at four different time points of stress exposure. The activity was represented as nmoles/min/mg protein. All the experiments were repeated thrice and represent as the average ± standard deviation (n = 3). The significance level of the paired student’s two-tailed t-test is represented as * and ** with a p-value less than 0.05 and 0.01; respectively.

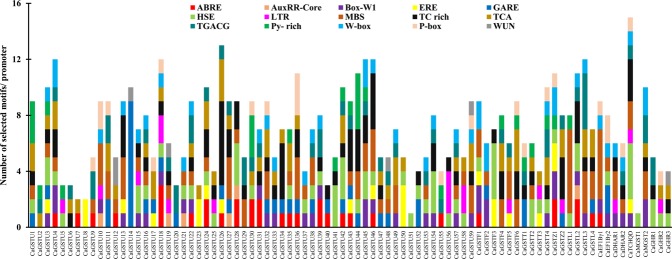

Presence of Cis-elements in the CaGST promoters

To understand the tissue-specificity or stress-responsive transcriptional regulation of CaGST genes, the 1000 bp 5′ upstream region from the transcriptional start site (ATG) was retrieved and scanned through PlantCARE database for the identification of important cis-regulatory elements. The promoters possessed several cis-elements that confer hormone and stress response. We have identified the presence of seven hormone-related such as abscisic acid-responsive (ABRE), auxin-responsive (AUXRR-core), ethylene-responsive (ERE), gibberellin-responsive (GARE and P-box), salicylic acid-responsive elements (TCA-element) and MeJA-responsive element (TGACG-motif); seven defense and stress-responsive elements such as fungal elicitor-responsive (Box-W1, W-Box), heat stress-responsive (HSE), low-temperature-responsive (LTR) elements, MYB binding site involved in drought-inducibility (MBS), stress responsiveness (TC-rich repeats), and wound-responsive element (WUN-motif); and one transcriptional enhancer (pyrimidine-rich motif) (Fig. 7). The upstream region of most CaGST members contained at least one hormone-related and one stress-related element. The top four abundant elements involved in the hormone and stress responses are - MBS element with 85 instances, 83 instances of the defense and stress-responsive element (TC-rich repeats), 64 instances of HSE element and 63 instances of TCA element (Table S5). The promoter of CaTCHQD contains the highest number of 15 cis-element, followed by the promoter of CaGSTU26 with 13 members. Whereas the minimum number of one cis-regulatory element was positioned in the promoter of CaGSTU51 and CaMGST1, followed by the promoter of CaGSTU7 and CaGSTU8 with 2 motifs (Fig. 7). Presence of such diverse type of hormone and stress-inducible cis-elements could be directly correlated with the positive alteration of the CaGST transcripts (Fig. 5) and total GST activity (Fig. 6) under various abiotic stress conditions.

Figure 7.

Analysis of the putative promoter of CaGST genes. One kb 5′ upstream sequences of all the identified CaGST genes were retrieved from the genome database and analyzed through PlantCARE to identify the presence and number of various cis-acting regulatory elements. Different hormone-responsive and stress-related elements were identified and plotted against a bar diagram. The abundance of different regulatory elements on each of the promoter was represented with different colors.

Discussion

Hot Pepper (C. annuum) is one of the most economically important, nutritious and world-wide grown spicy vegetable37. Various environmental stresses including salt, wind, cold, temperature, drought, humidity and osmotic stress cause a serious threat and thus, constrain the total production of pepper38. Water deficit notably diminishes the final fruit production in Capsicum chinense by interfering with the process of flowering and fruit development39. Much focus has been given in recent years to understand the stress responses and adaptation mechanisms of pepper by identifying many of the master regulatory genes40–42. GSTs are a promiscuous enzyme family that plays a vital role in the growth and development as well as stress management. A comprehensive genome-wide exploration identified a total of eighty-five CaGST gene members (Table 1) with at least one conserved GST domain (Fig. S3). The number of identified GST genes are higher in pepper as compared to most other species; but fewer than barley, tomato, potato and soybean14,15,22–25,28–33,36,43,44. Among the ten identified classes of CaGST, tau is the most abundant class, followed by phi (Table 1). The almost similar pattern of tau and phi dominance was observed in other plant species; and thus, termed as plant-specific GSTs15,45. In spite of the ubiquitous abundance of the tau class in tracheophytes (25–62 copies), they are completely missing in Physcomitrella patens and green algae35. The possible reason behind the tau and phi class-specific expansion might be their substantial functional influence on the xenobiotics metabolism and stress tolerance against both pathogens and environmental factors35,46–48.

The expansion of a gene family occurs mainly through three evolutionary mechanisms such as tandem duplication, segmental duplication, and transposition41. Due to the polyploidy nature of most plants, segmental duplication occurs frequently as compared with the other two means. The members of CaGST gene family arises largely due to several rounds of tandem and segmental gene duplications. Among the 59 tau GSTs in Capsicum, sixteen (27%) were created by segmental duplication and fourteen (23%) by the tandem duplication event, indicating that segmental duplication has the major contribution for the rapid expansion of the tau GSTs in Capsicum (Table S3). Apart from that, gene clustering also played an important role in the family expansion where 52 out of 59 CaGSTUs (88%) were presented in the eleven clusters on eight chromosomes (0, 1, 2, 3, 7, 8, 9 and 11). Similarly, 3 out of 4 theta GST (75%), 3 out of 3 DHAR GST (100%), 2 out of 4 lambda GST (50%), 2 out of 6 phi GST (33%) formed one cluster each (Fig. S1). This indicates a major contribution of tandem clustering towards the expansion of gene members in each class. Interestingly, different GST proteins from the same genomic cluster showed distinct variation in their enzymatic activity, catalytic efficiency, substrate affinity, and specificities34,35. The reasons behind these extensive tandem duplication event in GST gene family with the diverse kinetic property are still unknown.

Most CaGST genes shared a similar exon-intron structure within the same phylogenetic group (Fig. 1), indicating that the evolution of GST domains may be closely related to the diversification of gene structure. Gene structure analysis showed variation in the presence of exon number in various CaGST genes. The number of exons varied from one to a maximum of ten in CaGST genes, where the majority of them were single exonic (Fig. 1). Likewise CaGSTs, the presence of nine introns was reported previously for tomato and potato GST genes28,36, while a maximum number of 16 and 14 were reported in Vigna radiate and Chinese cabbage, respectively49,50. Previous reports suggested that introns influence and enhance the expression of a gene in a eukaryotic organism, which has been experimentally validated with heterologous gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana51,52. The clustering of most intronless or intron-containing genes into the same group (Fig. 1), suggested that this may be a unique feature of the evolution of pepper GST gene family. Due to the less selection pressure, intronic sequences possess a higher rate of gain and loss as compared with exonic sequences53. In two of the five segmentally duplicated rice gene pairs showed intron gain event53. An interesting study of 612 pairs of paralogs from seven representative gene families and 300 pairs of orthologs from different species, concluded that orthologs are more conserved with significantly fewer structural changes as compared with paralogs of similar evolutionary time54.

Phylogenetic analysis revealed that CaGSTs were closely allied to the same class of GSTs of four other plant species- tomato, potato, Arabidopsis, and rice (Fig. 2). This suggested that the evolution and divergence of each GST classes have happened before the split of monocot and dicot. However, CaGST members are more closely related to the tomato and potato as compared with Arabidopsis and rice counterparts, reflecting the fact that pepper, tomato, and potato belong to the same superfamily of eudicots and diverged more recently from a common ancestor37. Orthologous gene-based phylogenetic analysis of grape, papaya, pepper, tomato, potato, and Arabidopsis genome concluded that pepper has been separated from tomato and potato ∼36 Mya ago55. Thus, pepper GSTs were compared with that of tomato to elucidate the lineage-specific expansion and genome diversity among these two species (Fig. 3). Thirteen clades contained only CaGST and seven clades contained only tomato GST (Figs S3–S10), indicating that gene loss might have occurred in these clades. The number of clades indicated that there were at least 85 ancestral GST genes before the Capsicum-tomato split (Fig. 3).

Extensive expression analysis revealed the developmental stage and tissue specific transcript alteration of CaGST genes (Fig. 4). Similarly, nine genes were expressed ubiquitously, ten showed root specificity and two expressed in leaves out of 37 tau GST of Sorghum bicolor56. Six sunflower GST genes were mainly expressed in leaves, four in seeds and two each in flowers and roots out of a total of 14 identified members32. In addition to the developmental alteration, expression of GST genes also showed significant variation in response to adverse environmental conditions (Fig. 5). Plants exposure with various abiotic stresses such as cold, heat, drought and salt resulted in the enhancement ROS level and thus, caused oxidative stress57. Tau GSTs could protect the cell by enhancing the detoxification of herbicides such as atrazine, metolachlor, flurodifen, and thiocarbamates58 and maintaining higher GST activity under salinity and oxidative stress19. JrGSTT1 enhanced chilling stress tolerance of Juglans regia by protecting oxidative enzymes, scavenging ROS, and elevating the expression of several stress-related genes59. Upregulation of most of the SlGST transcripts in response to multiple abiotic stresses could be directly harmonized with the enhancement of total GST activity under similar conditions36. Similarly, upregulation of 6 HaGSTs (HaGSTU1, U2, U5, U6, F2, and Z1) expression showed a significant positive correlation with the changes in their respective GST activity32. The present study also found the positive relationship between the GST transcript upregulation and enzyme activity in pepper against four abiotic stresses and oxidative injury (Fig. 6). Heterologous expression of one of the sweet orange tau GST or JrGSTT1 in tobacco enhanced tolerance against herbicide, salinity, chilling and drought stresses56,59. Several stress-responsive motifs were identified in the putative promoter region of CaGST genes (Fig. 7). Cis-acting elements played important to control/regulate the expression of genes and thus, modulating plant response against stress and developmental changes60. Two commonly present abiotic stress‐inducible cis‐acting elements, dehydration‐responsive element (DRE) and ABRE are found to be interdependent in the ABA‐responsive expression of Atrd29A gene60,61. Similarly, the presence of two putative low-temperature responsive cis-elements in the 5′-proximal region of BN115 gene was found to be indispensable for its cold-induced expression in Brassica napus61. The highly abiotic stress responsive genes of the present study such as CaGSTF3, CaGSTL2, CaGSTL3, CaEF1Bγ1, and CaGSTU44, showed the presence of a variable amount of HSE, MBS, TC-rich repeat, and LTR motifs (Figs 6, 7). All these common motifs might work synergistically depending on the type of stress to induce the expression of a maximum number of stress-responsive genes.

Taken together, our results provide a comprehensive analysis of the GST gene family in pepper. Sequence and phylogenetic analysis of GST from five different plant species revealed the evolutionary conservation of each class of GST proteins. A close relationship between the expression and activity of GST with plant stress tolerance established GST as a major stress biomarker for the plant.

Materials and Methods

Sequence retrieval, analysis, and annotation

To retrieve all GST members in pepper, previously reported rice and Arabidopsis GST protein sequences from each class was taken as a query in the blastp search with the default parameters (e-value10−10) against the Pepper Genome Protein Database (release 2.0) (http://peppersequence.genomics.cn; http://public.genomics.org.cn/BGI/pepper/) and Sol Genomics Network (SGN) (https://www.solgenomics.net/). Sequences were then analyzed through the NCBI conserved domain database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) to identify the individual class of each identified members. Detailed information about the locus name, CDS coordinate (5′-3′), length of the transcript and peptide were collected from the Pepper Genome Database (http://pepperhub.hzau.edu.cn/pegnm/) and Sol Genomics Network (SGN). The ProtParam tool (http://www.expasy.org/tools/protparam.html) was used to calculate various physiochemical properties like molecular weight and theoretical isoelectric point (pI) of the identified proteins. The secondary structure of GST proteins was predicted using the SOPMA (Self-Optimized Prediction Method with Alignment, https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page=/NPSA/npsa_sopma.html). Moreover, N-glycosylation sites were identified using NetNGlyc 1.0 server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetNGlyc/). Furthermore, subcellular localization was predicted using the CELLO version 2.5 (http://cello.life.nctu.edu.tw/), pSORT (http://www.genscript.com/wolf-psort.html) and ChloroP server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ChloroP/). Pfam (http://pfam.xfam.org/) was used to assess the conserved GST_N and GST_C domains in all the identified members. Domains were graphically depicted using the software ‘Illustrator for Biological Sequences’ (version 1.0.2). The conserved motifs of CaGST proteins were identified using the online MEME server (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme).

Chromosome localization, gene structure and duplications

The physical location of CaGST genes was collected from the Pepper Genome Database and the positions of these CaGST genes were plotted to thirteen C. annuum chromosomes. Exon-intron structure of CaGST genes was obtained by gene structure display server (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) using the corresponding genomic and CDS sequence. Duplication events were predicted by blastp search (e-value10−10) with ≥80% sequence identity in the Pepper Genome Database62. Two or more homologous genes within 100 Kb region on the same chromosome were considered as tandemly duplicated (TD)62, while those located beyond 100 kb region were designated as segmental duplication (SD). Synonymous rate (dS), non-synonymous rate (dN), and evolutionary constraint (dN/dS) between the duplicated CaGST gene pairs were analyzed using the PAL2NAL online tool (http://www.bork.embl.de/pal2nal/). Divergence time (T) of each duplicated gene pairs was calculated using the formula: (T = dS/2λ), where λ is considered as a fixed rate of 1.5 × 10−8 substitutions per site per year for dicotyledonous plants63.

Phylogenetic analysis

To analyze the evolutionary relationship, GST protein sequences from five different species- Capsicum annuum, Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa, Solanum lycopersicum and Solanum tuberosum were obtained from respective genome database and class information was gathered from the previously published literatures14,15,28,36. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the default parameters of the maximum likelihood method in MEGA 7 software with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The James Taylor Thornton (JTT) substitution model was set with the site coverage cutoff of 95%. To investigate the lineage-specific expansion of GST genes in Capsicum annuum and Solanum lycopersicum, ten class-specific phylogenetic trees were constructed using MEGA 7 software according to the above mentioned procedure.

Pepper RNA-seq data analysis

Illumina RNA sequenced gene expression profiling data of each CaGST genes at different tissues and developmental stages and in response to five abiotic stresses was obtained from the pepper hub transcriptome database (http://pepperhub.hzau.edu.cn/petdb/). For abiotic stress treatments, datasets were obtained from the database for 0, 1, 1.5, 3, 6, 12 and 24 h of cold, heat, drought, salinity and osmotic stress treatments for leaf and root tissue, and the relative fold change of expression was calculated based on their control value (0 h). Heat maps with hierarchical clustering were performed using the default parameters of TIGR Multiple Experiment Viewer (MEV) 4.9 software package with the Manhattan correlation64.

Plant materials, stress treatment, and total GST activity

C. annuum (BARI Morich-3) were germinated and grown as described previously by Guo et al.40. Fifteen days old plants were soaked with normal water (for experimental control), or 200 mM NaCl (for salinity), or 5% mannitol (for drought stress), or 5 mM H2O2 (for oxidative stress), or normal water at 400C (for heat stress) or 40C (for cold stress). Shoot samples were collected at 0, 6, 12, and 24 hours post-stress induction. Total protein was extracted using the ice-cold extraction buffer containing 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 50% glycerol, 16 mM MgSO4 and 1 mM PMSF57. After quantification of the protein by Bradford method65, GST activity was measured by its ability to conjugate the reduced glutathione and 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene at 344 nm36. Activity was calculated using the extinction coefficient of the product formed (9.6 mM−1 cm−1) and was expressed as nmoles of CDNB conjugated/minute/mg of total protein.

Analysis of putative promoter sequence

The 1000 bp 5′ upstream sequences from the transcription start site of all the CaGST genes were acquired from the pepper hub (http://pepperhub.hzau.edu.cn/pegnm/) and then analyzed individually on the PlantCARE program (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) with default parameters for the identification of the important stress and hormone responsive cis-regulatory elements66.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

SI, SDS, and AG acknowledge the logistic support and laboratory facilities of the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet, Bangladesh. ZSJ, SA, and TI acknowledge Plant Breeding and Biotechnology Laboratory, Department of Botany, University of Dhaka for providing laboratory facilities. AG acknowledges the Humboldt Research Fellowship for Postdoctoral Researchers.

Author Contributions

A.G. conceived the idea. A.G. and T.I. designed the experiments. S.I., S.D.S., Z.S.J., and S.A. performed the experiments. A.G., T.I., and S.I. analyzed data. S.I. and S.D.S. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors read the manuscript and approved the final version.

Data Availability

The authors declare that all the data and plant materials will be available without restrictions.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Shiful Islam and Saikat Das Sajib contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Tahmina Islam, Email: subarna.islam@gmail.com.

Ajit Ghosh, Email: ajitghoshbd@gmail.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-45320-x.

References

- 1.Hayes JD, McLellan LI. Glutathione and glutathione-dependent enzymes represent a co-ordinately regulated defence against oxidative stress. Free Radic Res. 1999;31:273–300. doi: 10.1080/10715769900300851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards, R., Dixon, D. P., Cummins, I., Brazier-Hicks, M. & Skipsey, M. In Organic xenobiotics and plants 125–148 (Springer, 2011).

- 3.Frova C. The plant glutathione transferase gene family: genomic structure, functions, expression and evolution. Physiologia plantarum. 2003;119:469–479. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-3054.2003.00183.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marrs KA. The functions and regulation of glutathione S-transferases in plants. Annual review of plant biology. 1996;47:127–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loguercio C, et al. Alpha-glutathione transferases in HCV-related chronic hepatitis: a new predictive index of response to interferon therapy? Journal of hepatology. 1998;28:390–395. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(98)80311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basantani, M. & Srivastava, A. J. B. Plant glutathione transferases—a decade falls short. 85, 443–456 (2007).

- 7.Mohsenzadeh S, et al. Plant glutathione S-transferase classification, structure and evolution. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2011;10:8160–8165. doi: 10.5897/AJB11.1024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lallement P-A, Brouwer B, Keech O, Hecker A, Rouhier N. The still mysterious roles of cysteine-containing glutathione transferases in plants. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2014;5:192. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar S, Trivedi P. Glutathione S-transferases: An Update for the Role in Arsenic Detoxification Mechanism. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2018;9:751. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheehan D, Meade G, Foley VM. Structure, function and evolution of glutathione transferases: implications for classification of non-mammalian members of an ancient enzyme superfamily. Biochemical Journal. 2001;360:1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj3600001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon DP, Davis BG, Edwards R. Functional divergence in the glutathione transferase superfamily in plants identification of two classes with putative functions in redox homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:30859–30869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202919200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moons A. Regulatory and functional interactions of plant growth regulators and plant glutathione S-transferases (GSTs). Vitamins &. Hormones. 2005;72:155–202. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(05)72005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thuillier A, et al. Atypical features of a Ure2p glutathione transferase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium. FEBS letters. 2013;587:2125–2130. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jain M, Ghanashyam C, Bhattacharjee A. Comprehensive expression analysis suggests overlapping and specific roles of rice glutathione S-transferase genes during development and stress responses. BMC genomics. 2010;11:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sappl PG, et al. The Arabidopsis glutathione transferase gene family displays complex stress regulation and co‐silencing multiple genes results in altered metabolic sensitivity to oxidative stress. The Plant Journal. 2009;58:53–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skopelitou K, et al. Characterization and functional analysis of a recombinant tau class glutathione transferase GmGSTU2-2 from Glycine max. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2017;94:802–812. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nutricati E, Miceli A, Blando F, De Bellis L. Characterization of two Arabidopsis thaliana glutathione S-transferases. Plant cell reports. 2006;25:997–1005. doi: 10.1007/s00299-006-0146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallé Á, et al. Glutathione transferase activity and expression patterns during grain filling in flag leaves of wheat genotypes differing in drought tolerance: response to water deficit. Journal of plant physiology. 2009;166:1878–1891. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma R, Sahoo A, Devendran R, Jain M. Over-expression of a rice tau class glutathione s-transferase gene improves tolerance to salinity and oxidative stresses in Arabidopsis. PloS one. 2014;9:e92900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kissoudis C, et al. Stress-inducible GmGSTU4 shapes transgenic tobacco plants metabolome towards increased salinity tolerance. Acta physiologiae plantarum. 2015;37:102. doi: 10.1007/s11738-015-1852-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cicero LL, Madesis P, Tsaftaris A, Piero ARL. Tobacco plants over-expressing the sweet orange tau glutathione transferases (CsGSTUs) acquire tolerance to the diphenyl ether herbicide fluorodifen and to salt and drought stresses. Phytochemistry. 2015;116:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rezaei MK, Shobbar Z-S, Shahbazi M, Abedini R, Zare S. Glutathione S-transferase (GST) family in barley: identification of members, enzyme activity, and gene expression pattern. Journal of plant physiology. 2013;170:1277–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vijayakumar H, et al. Glutathione transferases superfamily: cold-inducible expression of distinct GST genes in Brassica oleracea. International journal of molecular sciences. 2016;17:1211. doi: 10.3390/ijms17081211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dong Y, et al. Glutathione S-transferase gene family in Gossypium raimondii and G. arboreum: comparative genomic study and their expression under salt stress. Frontiers in plant science. 2016;7:139. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang Q, Liu Y-J, Zeng Q-Y. Biochemical functions of the glutathione transferase supergene family of Larix kaempferi. Plant physiology and biochemistry. 2014;77:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGonigle B, Keeler SJ, Lau S-MC, Koeppe MK, O’Keefe DP. A genomics approach to the comprehensive analysis of the glutathione S-transferase gene family in soybean and maize. Plant Physiology. 2000;124:1105–1120. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.3.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Libin, Qian Ming, Wang Runze, Wang Li, Zhang Shaoling. Characterization of the glutathione S-transferase (GST) gene family in Pyrus bretschneideri and their expression pattern upon superficial scald development. Plant Growth Regulation. 2018;86(2):211–222. doi: 10.1007/s10725-018-0422-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Islam MS, Choudhury M, Majlish A-NK, Islam T, Ghosh A. Comprehensive genome-wide analysis of Glutathione S-transferase gene family in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) and their expression profiling in various anatomical tissues and perturbation conditions. Gene. 2018;639:149–162. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y-J, Han X-M, Ren L-L, Yang H-L, Zeng Q-Y. Functional divergence of the glutathione S-transferase supergene family in Physcomitrella patens reveals complex patterns of large gene family evolution in land plants. Plant physiology. 2013;161:773–786. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.205815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lan T, et al. Extensive functional diversification of the Populus glutathione S-transferase supergene family. The Plant Cell. 2009;21:3749–3766. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.070219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu H-J, et al. Divergence in enzymatic activities in the soybean GST supergene family provides new insight into the evolutionary dynamics of whole-genome duplicates. Molecular biology and evolution. 2015;32:2844–2859. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma L, et al. Molecular cloning, identification of GSTs family in sunflower and their regulatory roles in biotic and abiotic stress. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2018;34:109. doi: 10.1007/s11274-018-2481-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Licciardello C, et al. Characterization of the glutathione S-transferase gene family through ESTs and expression analyses within common and pigmented cultivars of Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck. BMC plant biology. 2014;14:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han XM, Yang ZL, Liu YJ, Yang HL, Zeng QY. Genome-wide profiling of expression and biochemical functions of the Medicago glutathione S-transferase gene family. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2018;126:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He G, et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of the Glutathione S-Transferase Gene Family in Capsella rubella: Identification, Expression, and Biochemical Functions. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1325. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Islam S, Rahman IA, Islam T, Ghosh A. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of glutathione S-transferase gene family in tomato: Gaining an insight to their physiological and stress-specific roles. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0187504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim S, et al. Genome sequence of the hot pepper provides insights into the evolution of pungency in Capsicum species. Nature genetics. 2014;46:270. doi: 10.1038/ng.2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldberg, N. P. Chile pepper disorders caused by environmental stress. (Cooperative Extension Service, College of Agriculture and Home Economics …, 2004).

- 39.Jaimez R, Vielma O, Rada F, García‐Núñez C. Effects of water deficit on the dynamics of flowering and fruit production in Capsicum chinense Jacq in a tropical semiarid region of Venezuela. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science. 2000;185:113–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-037x.2000.00414.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo M, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the CaHsp20 gene family in pepper: comprehensive sequence and expression profile analysis under heat stress. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:806. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khan A, et al. Genome-wide analysis of dirigent gene family in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) and characterization of CaDIR7 in biotic and abiotic stresses. Scientific reports. 2018;8:5500. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23761-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang H-X, et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the SBP-box family genes under Phytophthora capsici stress in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Frontiers in plant science. 2016;7:504. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu, Y.-J., Han, X.-M., Ren, L.-L., Yang, H.-L. & Zeng, Q.-Y. Functional divergence of the GST supergene family in Physcomitrella patens reveals complex patterns of large gene family evolution in land plants. Plant physiology, pp. 112.205815 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Wang, L., Qian, M., Wang, R., Wang, L. & Zhang, S. Characterization of the glutathione S-transferase (GST) gene family in Pyrus bretschneideri and their expression pattern upon superficial scald development. Plant Growth Regulation, 1–12 (2018).

- 45.Kumar S, et al. Differential expression of rice lambda class GST gene family members during plant growth, development, and in response to stress conditions. Plant molecular biology reporter. 2013;31:569–580. doi: 10.1007/s11105-012-0524-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loyall L, Uchida K, Braun S, Furuya M, Frohnmeyer H. Glutathione and a UV light–induced glutathione S-transferase are involved in signaling to chalcone synthase in cell cultures. The Plant Cell. 2000;12:1939–1950. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.10.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benekos K, et al. Overexpression of a specific soybean GmGSTU4 isoenzyme improves diphenyl ether and chloroacetanilide herbicide tolerance of transgenic tobacco plants. Journal of biotechnology. 2010;150:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cummins, I. et al. Key role for a glutathione transferase in multiple-herbicide resistance in grass weeds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 201221179 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Vaish S, et al. In silico genome-wide identification and characterization of the glutathione S-transferase gene family in Vigna radiata. Genome. 2018;61:311–322. doi: 10.1139/gen-2017-0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Du, J. et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the glutathione S-transferase (GST) family under different developmental tissues and abiotic stresses in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis). PeerJ PrePrints (2018).

- 51.Emami S, Arumainayagam D, Korf I, Rose AB. The effects of a stimulating intron on the expression of heterologous genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant biotechnology journal. 2013;11:555–563. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shaul O. How introns enhance gene expression. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2017;91:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin H, Zhu W, Silva JC, Gu X, Buell CR. Intron gain and loss in segmentally duplicated genes in rice. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R41. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-5-r41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu G, Guo C, Shan H, Kong H. Divergence of duplicate genes in exon-intron structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:1187–1192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109047109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qin C, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of cultivated and wild peppers provides insights into Capsicum domestication and specialization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111:5135–5140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400975111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chi Y, et al. Expansion mechanisms and functional divergence of the glutathione S-transferase family in sorghum and other higher plants. DNA research. 2010;18:1–16. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsq031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ghosh A, Pareek A, Sopory SK, Singla-Pareek SL. A glutathione responsive rice glyoxalase II, OsGLYII-2, functions in salinity adaptation by maintaining better photosynthesis efficiency and anti-oxidant pool. Plant J. 2014;80:93–105. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kawahigashi H. Transgenic plants for phytoremediation of herbicides. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2009;20:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang G, et al. In planta characterization of a tau class glutathione S-transferase gene from Juglans regia (JrGSTTau1) involved in chilling tolerance. Plant Cell Rep. 2016;35:681–692. doi: 10.1007/s00299-015-1912-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Narusaka Y, et al. Interaction between two cis-acting elements, ABRE and DRE, in ABA-dependent expression of Arabidopsis rd29A gene in response to dehydration and high-salinity stresses. Plant J. 2003;34:137–148. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiang C, Iu B, Singh J. Requirement of a CCGAC cis-acting element for cold induction of the BN115 gene from winter Brassica napus. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;30:679–684. doi: 10.1007/BF00049344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kayum MA, et al. Genome-wide characterization and expression profiling of PDI family gene reveals function as abiotic and biotic stress tolerance in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis) BMC genomics. 2017;18:885. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4277-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koch MA, Haubold B, Mitchell-Olds T. Comparative evolutionary analysis of chalcone synthase and alcohol dehydrogenase loci in Arabidopsis, Arabis, and related genera (Brassicaceae) Molecular biology and evolution. 2000;17:1483–1498. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johnson SC. Hierarchical clustering schemes. Psychometrika. 1967;32:241–254. doi: 10.1007/BF02289588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lescot M, et al. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:325–327. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all the data and plant materials will be available without restrictions.