Ceftibuten-clavulanate (CTB-CLA) is a novel β-lactam–β-lactamase combination with potential utility for the management of urinary tract infections caused by extended-spectrum-β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing organisms. We examined the pharmacodynamics of the combination against 25 Enterobacteriaceae expressing β-lactamases (CTX-M, TEM, and SHV wild types and SHV-ESBL) in the murine thigh infection model.

KEYWORDS: beta-lactamase inhibitor, clavulanic acid, extended-spectrum β-lactamases, human-simulated regimens, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, urinary tract infections

ABSTRACT

Ceftibuten-clavulanate (CTB-CLA) is a novel β-lactam–β-lactamase combination with potential utility for the management of urinary tract infections caused by extended-spectrum-β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing organisms. We examined the pharmacodynamics of the combination against 25 Enterobacteriaceae expressing β-lactamases (CTX-M, TEM, and SHV wild types and SHV-ESBL) in the murine thigh infection model. MIC values of CTB and CTB-CLA ranged from 1 to >32 mg/liter and 0.125 to 8 mg/liter, respectively. Human-simulated regimens of CTB and CLA equivalent to clinical doses of 400 mg orally (p.o.) every 8 h (q8h) and 187 mg q8h, respectively, were developed. CLA dose fractionation studies were undertaken to characterize the driver of efficacy. CLA dose-ranging studies were undertaken to assess the activity of the CTB human-simulated regimen in combination with escalating CLA exposures. The relationships between the percentage of the dosing interval during which the free CLA plasma concentrations remained above a threshold concentration (%fT>CT) and the change in log10 CFU per thigh at 24 h were examined across different threshold concentrations. Additionally, the efficacy of a human-simulated regimen of CTB-CLA was assessed against isolates with various susceptibilities to the combination. The pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic index that best correlated with the efficacy of the combination was %fT > threshold CLA plasma concentration of 0.5 mg/liter. The plasma %fT>0.5 mg/liter associated with the static endpoint was 20.59%. For isolates with CTB-CLA MICs of ≤4 mg/liter, stasis was achieved with a human-simulated regimen of CTB-CLA against 20/22 isolates (90.9%), while for isolates with MICs of 8 mg/liter, only 1/3 tested isolates (33.3%) displayed stasis. Results suggest a susceptibility breakpoint of 4 mg/liter for CTB-CLA. These data support the consideration of the CTB-CLA combination for the treatment of urinary tract infections due to ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae.

INTRODUCTION

The discovery of novel oral β-lactam–β-lactamase inhibitor (BL-BLI) combinations is an increasingly attractive avenue of development in the antimicrobial space (1). Particularly in the context of urinary tract infections (UTIs), where rates of infection caused by extended-spectrum-β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing organisms continue to rise and few oral options for treatment exist, these combinations provide a convenient, noninvasive (i.e., nonintravenous) option which may be administered outside the institutional setting (2). Furthermore, the pharmacokinetic (PK) characteristics of oral agents that are predominately excreted via glomerular filtration are generally favorable for the treatment of UTI, as adequate drug exposures are achieved by means of accumulation in the bladder to derive sufficient bacterial kill (3, 4).

Ceftibuten (CTB) is an oral third-generation cephalosporin originally approved in 1995 for the treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis, acute otitis media, and pharyngitis caused by Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, or Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates (5). It is also used off-label for the treatment of UTI due to susceptible bacteria. In addition to its advantages as an oral formulation and its favorable safety profile, CTB proves an attractive choice for development as a BL-BLI combination given that it exhibits improved stability against hydrolysis by several class A and B β-lactamases compared with other agents in the class, specifically those produced by urogenital pathogens (6).

Clavulanic acid (CLA) is a well-known β-lactamase inhibitor, currently in use clinically as a coformulation with either amoxicillin or ticarcillin. Although largely well tolerated, its dose-limiting adverse effect is most commonly gastrointestinal (i.e., nausea, stomach pain, and diarrhea) (7). CLA has shown effective inactivation of serine β-lactamases, including ESBLs (8, 9).

Here, we investigated the pharmacodynamic (PD) profile of the novel CTB-CLA combination in the murine thigh infection model against a phenotypically and genotypically diverse group of Enterobacteriaceae isolates expressing ESBLs of the SHV and CTX-M types.

RESULTS

In vitro susceptibility.

A summary of the 25 Enterobacteriaceae isolates utilized in this study, their MICs for CTB and CTB-CLA (2:1 ratio), as well as their β-lactamase expression is shown in Table 1. CTB MICs were 1 to 32 mg/liter, while CTB-CLA combination MICs ranged between 0.125 and 8 mg/liter.

TABLE 1.

All the isolates selected for the in vivo efficacy studies

| Isolate | JMI isolate identification no. | Bacterial species | MIC (mg/liter) |

Positive molecular test result(s)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTB | CTB-CLA (2:1) | ||||

| KP 620 | 36196 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 16 | 0.25 | SHV-ESBL, SHV-WT |

| KP 622 | 12197 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 32 | 0.5 | CTX-M gp1, SHV-WT |

| EC 506 | 45360 | Escherichia coli | >32 | 1 | CTX-M gp1 |

| EC 513 | 129 | Escherichia coli | >32 | 4 | CTX-M gp1 |

| KP 632 | 27358 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | >32 | 8 | CTX-M gp1, SHV-WT, TEM-WT |

| EC 501 | 415 | Escherichia coli | 4 | 0.5 | CTX-M gp1 |

| KP 626 | 50826 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 32 | 1 | CTX-M gp1, SHV-WT, TEM-WT |

| EC 511 | 51193 | Escherichia coli | 16 | 2 | CTX-M gp1, TEM-WT |

| EC 514 | 4366 | Escherichia coli | >32 | 4 | CTX-M gp1, CTX-M gp9, TEM-WT |

| KP 631 | 41235 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | >32 | 8 | CTX-M gp1, SHV-WT, TEM-WT |

| EC 495 | 14318 | Escherichia coli | 1 | 0.25 | CTX-M gp2, TEM-WT |

| EC 496 | 40357 | Escherichia coli | 2 | 0.25 | CTX-M gp9 |

| EC 500 | 51167 | Escherichia coli | 2 | 0.5 | CTX-M gp9 |

| EC 510 | 28560 | Escherichia coli | 2 | 2 | CTX-M gp1 |

| KP 617 | 26344 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 8 | 0.12 | CTX-M gp1, TEM-WT |

| KP 623 | 14317 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 16 | 0.5 | CTX-M gp1, SHV-ESBL, SHV-WT, TEM-WT |

| KP 624 | 9804 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | >32 | 1 | CTX-M gp1, CTX-M gp9, TEM-WT, SHV-WT |

| KP 625 | 45397 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | >32 | 1 | CTX-M gp1, SHV-WT |

| KP 627 | 14163 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 8 | 2 | CTX-M gp1, SHV-WT |

| KP 630 | 9813 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | >32 | 4 | CTX-M gp1, SHV-WT, TEM-WT |

| KP 616 | 21312 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 4 | 0.12 | CTX-M gp1, SHV-WT, TEM-WT |

| KP 618 | 1246 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 4 | 0.12 | CTX-M gp1, SHV-WT, TEM-WT |

| KP 628 | 38765 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | >32 | 4 | CTX-M gp1, SHV-WT, TEM-WT |

| KP 633 | 54550 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | >32 | 8 | CTX-M gp1, SHV-WT, TEM-WT |

| EC 512 | 51173 | Escherichia coli | 32 | 4 | CTX-M gp9 |

WT, wild type.

Human-simulated exposure pharmacokinetic studies.

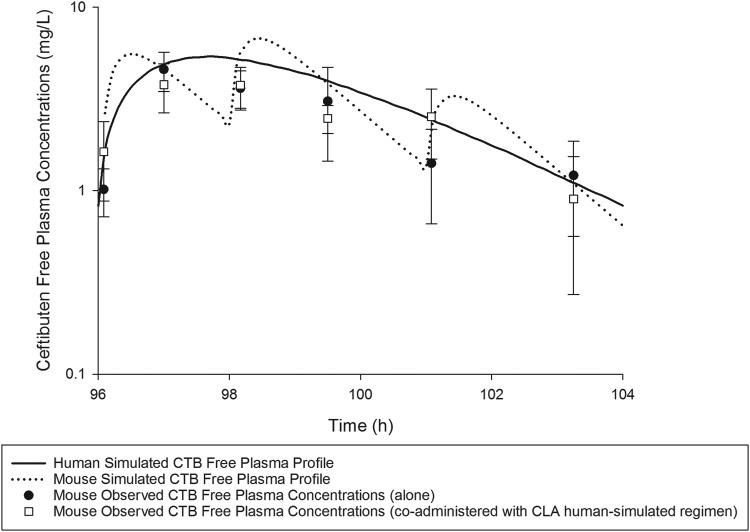

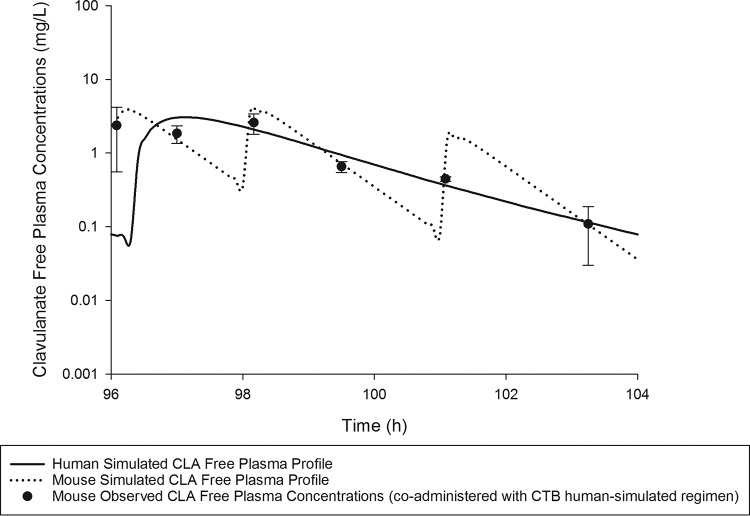

On the basis of the percentage of the dosing interval during which the free plasma drug concentrations remained above the MIC (%fT>MIC), a CTB exposure in mice similar to that predicted in humans following the oral administration of 400 mg every 8 h (q8h) was attained when mice were administered 2.4 mg/kg of body weight at 0 h, 2.2 mg/kg at 2 h, and 1 mg/kg at 5 h repeated every 8 h subcutaneously. Likewise, a CLA exposure in mice similar to that predicted in humans following the oral administration of 187 mg q8h was attained when mice were administered 1.68 mg/kg at 0 h, 1.54 mg/kg at 2 h, and 0.7 mg/kg at 5 h every 8 h subcutaneously. Comparisons of %fT>MIC values achieved with CTB and CLA at MICs ranging between 0.063 and 8 mg/liter and the area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h for the free, unbound fraction of the drug (fAUC0–24) in both humans and mice receiving the selected human-simulated regimens are presented in Table 2. Figure 1 illustrates the free plasma concentration-time profile of the CTB human-simulated regimen, when administered to mice alone and in combination with that of CLA. The coadministration of CLA did not alter CTB exposure, as shown in Fig. 1. Figure 2 illustrates the free plasma concentration-time profile of the CLA human-simulated regimen, when administered to mice in combination with that of CTB.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of %fT>MIC values achieved with CTB and CLA at different MICs in humans and mice

| Drug | Species | %fT>MIC for MIC (mg/liter) of: |

fAUC0–24 (mg·h/liter) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | |||

| CTB | Humana | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 93.33 | 68.75 | 35.00 | 0.00 | |

| Mouseb | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 91.25 | 71.25 | 32.08 | 0.00 | ||

| CLA | Humanc | 100.00 | 83.75 | 67.50 | 52.50 | 37.50 | 21.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 24.07 |

| Moused | 95.00 | 85.00 | 72.50 | 56.25 | 38.75 | 18.75 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 26.28 | |

Human exposures estimated based on the population pharmacokinetic parameters of CTB for a dose of 400 mg p.o. q8h.

Mouse exposure estimated based on best-fit pharmacokinetic parameters of CTB alone or in combination with CLA in infected mice.

Human exposures estimated based on the population pharmacokinetic parameters of CLA for a dose of 187 mg p.o. q8h.

Mouse exposure estimated based on best-fit pharmacokinetic parameters of CLA in combination with CTB in infected mice.

FIG 1.

CTB human-simulated free plasma concentration-time profile in the neutropenic thigh infection model (alone or in combination with the CLA human-simulated regimen) compared with humans receiving an oral dose of 400 mg every 8 h. Data are means ± standard deviations.

FIG 2.

CLA human-simulated free plasma concentration-time profile in the neutropenic thigh infection model compared with humans receiving an oral dose of 187 mg every 8 h. Data are means ± standard deviations.

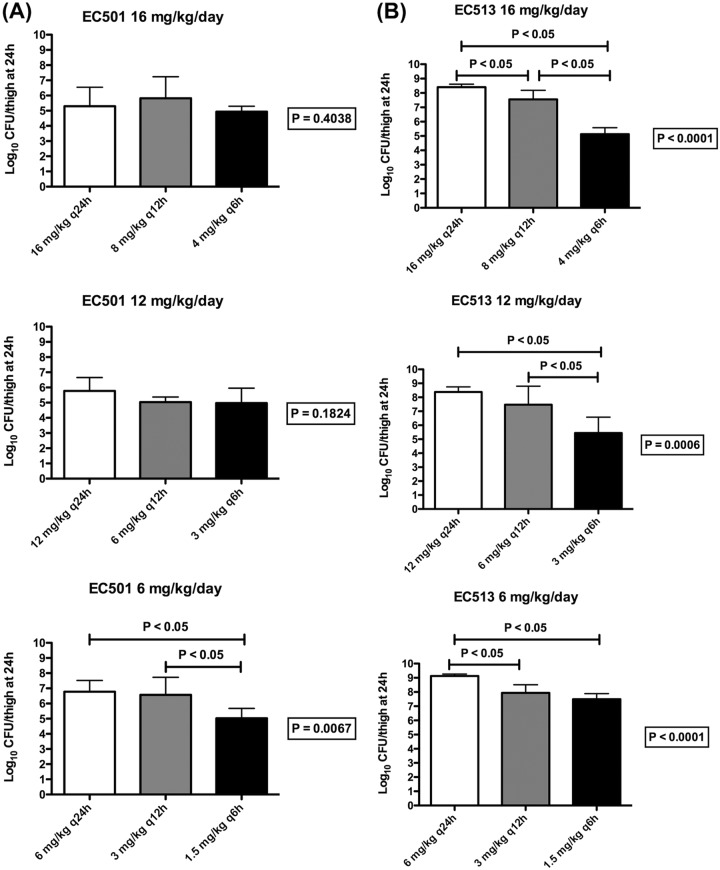

CLA dose fractionation studies.

The purpose of CLA dose fractionation studies was to determine the PK/PD index (the free, unbound peak drug plasma concentration to MIC ratio [fCmax/MIC ratio], fAUC/MIC ratio, and the percentage of the dosing interval during which the free, unbound drug plasma concentrations remained above a threshold concentration [%fT>CT]), relative to CLA exposure, that correlated most closely with the efficacy of the CTB-CLA combination. As such, 2 β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates were utilized in this investigation. These isolates were selected based on their phenotypic profiles to include 2 isolates with distinct CTB-CLA MICs, EC 501 and EC 513, with CTB-CLA (2:1) MICs of 0.5 and 4 mg/liter, respectively.

The results of the CLA dose fractionation studies against EC 501 and EC 513 are shown in Fig. 3. At 0 h, the average bacterial burden in the thighs was 5.89 ± 0.09 log10 CFU/thigh. For the two tested isolates, adequate growth in the neutropenic thigh infection model was achieved; the bacterial burdens increased over 24 h by average magnitudes of 3.48 ± 0.47 and 2.49 ± 1.28 log10 CFU/thigh in the control mice and those receiving the CTB human-simulated regimen alone, respectively. Compared with a CTB human-simulated regimen alone, the coadministration of CLA with all tested dosing regimens resulted in bacterial killing for isolate EC 501. For the 6-mg/kg/day dose, the fractionated administration (1.5 mg/kg q6h) was associated with a statistically significant difference in bacterial eradication compared with the once-daily (6 mg/kg q24h) or the twice-daily (3 mg/kg q12h) regimen of the same total daily dose (P < 0.05). This provided evidence that CLA exerted time-dependent enzyme inhibition, as fractionated administration resulted in enhanced bacterial killing. At the higher daily doses, improved killing was observed with more fractionated CLA administration; however, the difference in bacterial burdens across the different fractionated regimens did not reach the threshold of significance (P > 0.05). For isolate EC 513, the administration of CLA q6h was associated with a statistically significant difference in bacterial killing compared with that achieved with the q24h and/or the q12h regimens for all the daily doses examined (P < 0.05). Data from isolate EC 513 corroborated the findings from isolate EC 501 and indicated that relative to CLA exposure, the PK/PD index that best correlated with the efficacy of the CTB-CLA combination was %fT>CT (threshold plasma CLA concentration).

FIG 3.

Bacterial burdens in thighs at 24 h across CLA dosing frequencies (once, twice, and 4 times per 24 h) in combination with the CTB human-simulated regimen against EC 501 (A) and EC 513 (B). Data are means ± standard deviations.

CLA dose-ranging studies.

The purpose of CLA dose-ranging studies was to assess the in vivo bactericidal activity of the CTB human-simulated regimen in combination with various CLA exposures, including human-simulated exposure, against 11 β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates. At 0 h, the average bacterial burden in the thighs was 5.99 ± 0.29 log10 CFU/thigh. The bacterial burdens increased over 24 h by an average magnitude of 3.38 ± 0.45 log10 CFU/thigh in the control mice. For the majority of the tested isolates, an increase in the bacterial burden was observed in the thighs of the mice receiving the CTB human-simulated regimen alone; the bacterial burdens increased over 24 h by an average magnitude of 2.01 ± 1.35 log10 CFU/thigh compared with the 0-h control mice. The administration of the CTB human-simulated regimen was associated with different degrees of bacterial reduction compared with the burdens in the thighs of the 24-h control mice, which could be attributed to differences in the extent of expression of the different β-lactamases in the infection model utilized as well as the relative fitness of the isolates.

Compared with CTB human-simulated regimen alone, the coadministration of CLA at the tested exposures enhanced bacterial killing, as evidenced by a greater reduction in the initial bacterial burden. The average maximal reduction of the burden (Imax) at 24 h achieved due to coadministration of CLA was 3.76 ± 2.12 log10 CFU/thigh, estimated relative to the bacterial densities in the thighs of the mice treated with the CTB human-simulated regimen alone.

The relationships between the %fT>CT of the CLA plasma concentration and the change in the log10 CFU per thigh at 24 h for each isolate were examined for threshold concentrations ranging between 0.063 and 2 mg/liter. The exposure-response relationships for each isolate were strongest at a fixed threshold concentration of 0.5 mg/liter based upon the median coefficient of determination achieved at each of the threshold concentrations examined. The exposure-response relationships, in the context of %fT > threshold CLA plasma concentration of 0.5 mg/liter (%fT>0.5 mg/liter), for the majority of the isolates were relatively strong based upon the coefficient of determination (R2 ≥ 0.75 for 8 out of 11 isolates), as shown in Table 3. The threshold concentration of 0.5 mg/liter in this case represents the approximate plasma CLA concentration during the drug elimination phase, below which the expressed β-lactamases would no longer be effectively inhibited by CLA and a lack of in vivo activity would be observed.

TABLE 3.

CLA %fT>CT of 0.5 mg/liter required to achieve net stasis and 1-log killing against Enterobacteriaceae isolates

| Isolate (MIC [mg/liter])a | CLA %fT>0.5 mg/liter required to achieve: |

R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stasis | 1-log reductionb | ||

| EC 513 (4) | 22.35 | 39.58 | 0.9264 |

| EC 501 (0.5) | 12.55 | 16.51 | 0.6092 |

| EC 512 (4) | 0.00 | 12.49 | 0.4158 |

| KP 620 (0.25) | 0.61 | NA | 0.8746 |

| KP 622 (0.5) | 35.52 | NA | 0.7456 |

| EC 506 (1) | 1.40 | NA | 0.8755 |

| KP 626 (1) | 2.71 | NA | 0.9765 |

| EC 511 (2) | 7.15 | NA | 0.1032 |

| KP 631 (8) | 46.56 | 68.76 | 0.7769 |

| EC 514 (4) | 7.31 | NA | 0.8658 |

| KP 632 (8) | 75.67 | NA | 0.7925 |

| Median | 7.31 | 28.04c | 0.7925 |

| IQR | 1.40–35.52 | 13.5–61.47c | |

| Composite (all isolates) | 20.59 | 91.63 | 0.4732 |

MIC based on the combination of CTB-CLA (2:1 ratio). IQR, interquartile range.

NA, target not achieved.

Based on the estimate from 4 isolates only (EC 513, EC 501, EC 512, and KP 631).

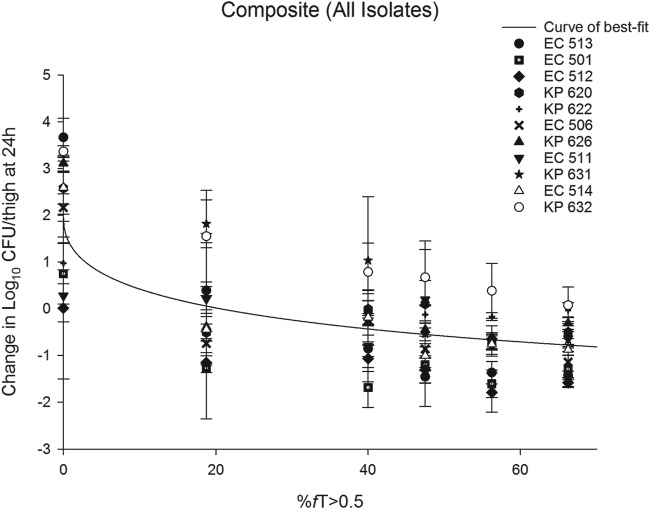

The relationship between the %fT>0.5 mg/liter and the change in the log10 CFU per thigh at 24 h for the composite plot of all 11 isolates is shown in Fig. 4. The median %fT>0.5 mg/liter associated with a static endpoint in Enterobacteriaceae isolates was 7.31%, with an interquartile range of 1.40% to 35.52%. The corresponding median target exposure associated with 1-log kill was 28.04%, with an interquartile range of 13.5% to 61.47%. However, the estimate of 1-log kill target exposure was based on predictions from only 4 isolates (EC 513, EC 501, EC 512, and KP 631). For the remaining 7 isolates, a 1-log reduction in the initial bacterial burden could not be attained based on the sigmoidal inhibitory maximal-effect (Emax) model predictions, even with a CLA exposure greater than that achieved with the targeted clinical CLA dose (187 mg). For isolate EC 512, the administration of the human-simulated regimen of CTB alone resulted in notable bacterial killing. Thus, the estimated CLA %fT>0.5 mg/liter associated with net stasis was approximately 0% for this isolate. For the composite of tested isolates, the values for plasma %fT>0.5 mg/liter associated with static and 1-log kill endpoints were 20.59% and 91.63%, respectively. Given that the human-simulated exposure of CLA provided a %fT>0.5 mg/liter of 56.25%, this exposure was predicted to be sufficient to attain stasis but not 1-log kill for the majority of the isolates.

FIG 4.

Curve of best fit to %fT>0.5 mg/liter and the change in log10 CFU per thigh at 24 h for the composite of all isolates tested in the neutropenic thigh infection model. The solid line represents the curve of best fit, while the symbols represent the actual changes in bacterial burdens observed in mice. Data are means ± standard deviations.

In vivo efficacy of human-simulated exposures.

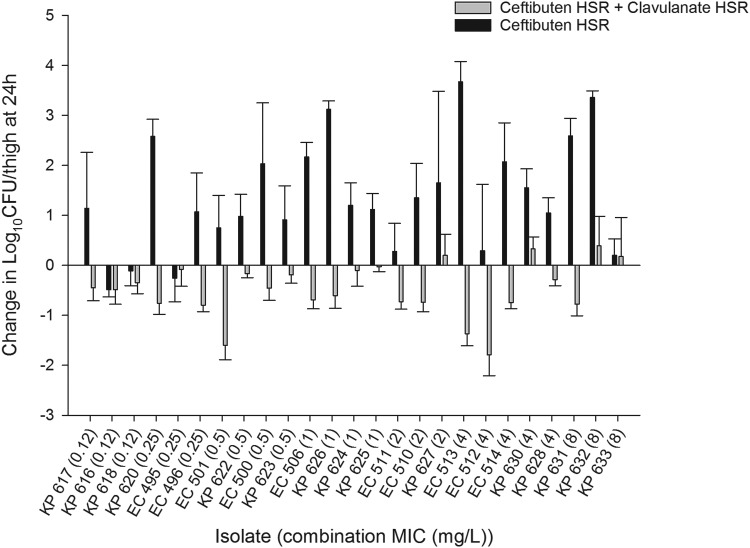

The in vivo efficacy of human-simulated CTB-CLA exposures against β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates was determined to help characterize the susceptibility breakpoint. As such, 25 genotypically diverse isolates exhibiting a range of CTB-CLA MICs were utilized. The results for the in vivo efficacies of CTB human-simulated exposure alone and in combination with CLA human-simulated exposure are presented in Fig. 5. At 0 h, the average bacterial burden in the thighs was 5.93 ± 0.26 log10 CFU/thigh. The bacterial burdens increased over 24 h by an average magnitude of 2.87 ± 0.81 log10 CFU/thigh in the control mice. For the majority of the tested isolates, an increase in the bacterial burden was observed for the thighs of the mice receiving the CTB human-simulated regimen alone; the bacterial burdens increased over 24 h by an average magnitude of 0.89 ± 1.03 log10 CFU/thigh compared with the 0-h control mice.

FIG 5.

Comparative efficacies of human-simulated exposures of CTB and CTB-CLA against 25 Enterobacteriaceae isolates. Data are means ± standard deviations. HSR, human-simulated regimen.

Compared with the CTB human-simulated regimen alone, coadministration with the CLA human-simulated regimen enhanced bacterial killing, as evidenced by a greater reduction in the initial bacterial burden for all the tested isolates. The human-simulated regimen of CTB-CLA was adequate to attain net stasis relative to the initial bacterial burdens at 24 h in a total of 21 out of 25 isolates. For isolates with MICs of ≤4 mg/liter (based on the MICs of the CTB-CLA combination at a ratio of 2:1), the static endpoint was achieved in 20 out of 22 isolates (90.9%). On the other hand, for isolates with MICs of 8 mg/liter, stasis was achieved in only 1 out of 3 tested isolates (33.3%). These data are suggestive of a susceptibility breakpoint of 4 mg/liter for the combination of CTB-CLA against Enterobacteriaceae isolates.

DISCUSSION

This investigation sought to characterize the efficacy of this novel BL-BLI combination against ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae to support potential indication as an oral agent for the management of UTI due to these resistant isolates. This is important given that the rates of UTI attributed to ESBL-producing organisms continue to rise, while oral agents with activity against these isolates are limited, particularly in cases of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and fluoroquinolone resistance (2, 10). According to data from a recent surveillance study conducted in the United States and Canada, among 3,498 Escherichia coli UTI isolates collected from 2010 to 2014, a statistically significant increase in rates of ESBL producers from 7.8 to 18.3% was observed (P < 0.0001). Furthermore, statistically significant decreases in susceptibility to cephalosporin agents, including cefepime, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, and ceftazidime, were also noted (2). In a study conducted by Prakash and colleagues, the authors sought to characterize the susceptibilities of CTX-M-, SHV-, and TEM-producing E. coli isolates from UTI to a variety of conventional agents (10). Among those isolates producing CTX-M (n = 46), none were susceptible to cefdinir alone, although in combination with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, isolates showed 89.1% susceptibility. These isolates’ susceptibilities to other oral options such as amoxicillin-clavulanic acid alone, doxycycline, and ciprofloxacin were found to be 10.9%, 10.9%, and 4.3%, respectively. Given that the currently available therapies for UTIs are increasingly associated with treatment failure, continued pharmacological innovation is greatly needed. This is particularly pressing in the context of outpatient care, where only a few oral options remain viable, and insufficient treatment is associated with poor clinical outcome (11–14).

In the present investigation, a genotypically diverse population of Enterobacteriaceae isolates (including those expressing CTX-M as well as TEM and SHV β-lactamases of wild types and ESBL types) at the upper end of the CTB MIC distribution with MICs of 1 to >32 mg/liter (MIC90 of ≤0.5 mg/liter among Enterobacteriaceae [15]) was chosen to represent the most challenging clinical potentialities. Multifold reductions in MICs were noted in the presence of CLA relative to the MICs of CTB alone; thereby, CLA restored the activity of CTB and improved its stability against hydrolysis in the presence of β-lactamase-producing isolates.

CLA dose fractionation studies and CLA dose-ranging studies were conducted to identify the PK/PD index and the magnitude of the index required to exert in vivo activity in the murine thigh infection model. In order to tease out the effect of CLA on the outcome of therapy with the CTB-CLA combination, CTB exposure was fixed such that all the animals were administered the CTB human-simulated regimen while varying CLA exposure only. This design allowed us to identify the PK/PD index as well as the magnitude of the index required to produce activity relative to CLA exposure.

The administration of human-simulated CTB-CLA exposures resulted in net stasis in vivo among the majority of the isolates examined, with combination CTB-CLA (2:1 ratio) MICs of ≤4 mg/liter, inclusive of those with CTB MICs of >32 mg/liter. The pharmacodynamic target of stasis in preclinical infection models is generally considered a surrogate endpoint for prediction of clinical efficacy in UTI, in contrast to a more deep-seeded infection (e.g., pneumonia), as drug accumulation in the bladder produces exposures that are severalfold higher than the plasma drug concentrations as well as the MICs for the causative organisms (15, 16). This has subsequently been shown to translate to good clinical efficacy, specifically in the context of treatment with cephalosporins for complicated UTs (cUTIs) attributed to ESBL producers (17–19). These data bolster confidence in the potential clinical utility of the CTB-CLA combination, given that at least net stasis can be achieved among the most resistant isolates.

Taken together, our data show promise for the development of the CTB-CLA combination (400 mg/187 mg orally [p.o.] every 8 h) for management of UTI caused by ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae and lend support for further investigation of this novel agent.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antimicrobial test agents.

Ceftibuten dihydrate (5 g) (batch number O0713A) and potassium clavulanate with 1:1 microcrystalline cellulose (5 g) (batch number AG41773) were acquired from Tecoland Corporation (Irvine, CA, USA). For in vivo testing, CTB was reconstituted to a 1-mg/ml concentration in a vehicle composed of 20% (wt/vol) (2-hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin (batch number WXBC2448V; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 50 mM Na-phosphate buffer (pH 7). Subsequent dilutions in the same vehicle were made to attain final concentrations that would deliver the required doses based on the mean weight of the study mouse population. For preparation of a 1-mg/ml stock solution of potassium clavulanate for in vivo testing, a known amount of potassium clavulanate with 1:1 microcrystalline cellulose was mixed with a sterile 0.9% normal saline solution (B. Braun Medical, Inc., Irvine, CA) by inversion, and the resulting suspension was then sonicated for 15 min on ice, followed by centrifugation at 3,250 × g at 4°C for 10 min to pellet the cellulose. The supernatant was filtered using 0.22-μm filter units (Millex-GV; Merck Millipore Ltd., Tullagreen, Carrigtwohill, Cork Co., Cork, Ireland). Subsequent dilutions were made using a sterile 0.9% normal saline solution. Stock CTB and CLA solutions were store at 4°C protected from light until immediately prior to use. CTB and CLA were administered via subcutaneous injections of 0.1 ml.

Bacterial isolates.

A total of 25 Enterobacteriaceae isolates expressing various β-lactamases (TEM, SHV, and CTX-M) were provided by JMI Laboratories (North Liberty, IA) for the assessment of the in vivo efficacy of the CTB-CLA combination. Selection of the isolates was based on phenotypic and genotypic information as well as the ability of the isolates to grow in the infection model utilized. The MICs of CTB and its combination with CLA at a fixed ratio of 2:1 in triplicate were examined by JMI Laboratories using the broth microdilution methodology outlined by the CLSI (20). For isolate MICs with the combination of CTB-CLA (2:1 ratio), quality control isolates E. coli ATCC 25922 (range, 0.12 to 0.5 mg/liter) and K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603 (range, 0.12 to 0.5 mg/liter) were utilized.

Animal infection model.

(i) Laboratory animals. Specific-pathogen-free, female ICR mice weighing 20 to 22 g were obtained from Envigo RMS, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN). The animals were allowed to acclimate for a minimum of 48 h before commencement of experimentation and were provided food and water ad libitum. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Hartford Hospital. Mice were rendered transiently neutropenic by injecting cyclophosphamide intraperitoneally (i.p.) at doses of 150 mg/kg of body weight 4 days before inoculation and 100 mg/kg of body weight 1 day before inoculation. In addition, uranyl nitrate at 5 mg/kg was administered 3 days prior to inoculation to produce a controlled degree of renal impairment to assist with humanizing the target exposures of both CTB and CLA.

(ii) Neutropenic thigh infection model. All isolates were previously frozen at −80°C in skim milk (BD Biosciences, Sparks, MD). Prior to mouse thigh inoculation, two transfers of the organisms were performed onto Trypticase soy agar plates with 5% sheep blood (TSA II; Becton, Dickinson and Co., Sparks, MD) and incubated at 37°C for approximately 24 h. After an 18- to 24-h incubation for the second bacterial transfer, a bacterial suspension of approximately 107 CFU/ml was made for inoculation. Final inoculum concentrations were confirmed by serial dilution and plating techniques. Thigh infection was produced by intramuscular injection of 0.1 ml of the inoculum into each thigh of the mouse 2 h prior to the initiation of antimicrobial therapy.

Human-simulated exposure pharmacokinetic studies.

Pharmacokinetic studies for CTB and CLA were carried out to identify regimens that provided exposures similar to those achieved in humans following the oral administration of 400 mg and 187 mg q8h of CTB and CLA, respectively, based the %fT>MIC. The pharmacokinetic profiles for CTB and CLA in healthy adult volunteers were simulated using previously defined population parameters (unpublished data; Achaogen, Inc.). CTB and CLA regimens were simulated for mice by using the parameters derived from the single-dose pharmacokinetic studies of each agent after applying the protein binding percentage (65% and 19.67% for CTB in humans and mice, respectively, and 30% and 2.27% for CLA in humans and mice, respectively). Once the regimens had been identified, confirmatory pharmacokinetic studies were undertaken to ensure that appropriate exposures were achieved. Infected animals (n = 36) were administered the human-simulated regimen of CTB. Groups of 6 mice were euthanized at 6 predefined time points. Terminal blood samples from CO2-asphyxiated mice were collected via cardiac puncture and placed in K2EDTA BD Microtainer tubes (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Plasma was separated by centrifugation for 10 min at 4°C at 10,000 × g and then transferred into polypropylene tubes. These tubes were stored at −80°C until analysis. The plasma samples were shipped to Intertek Pharmaceutical Services (San Diego, CA, USA) for CTB concentration determination. After the human-simulated regimen of CTB had been confirmed, the pharmacokinetics of both CTB and CLA were assessed when the human-simulated regimens of CLA and CTB were administered simultaneously. The CTB concentrations were compared visually to those previously achieved when CTB was administered alone to ascertain that coadministration of CLA did not alter the CTB profile.

CLA dose fractionation studies.

Mice were prepared and inoculated as described above, and treatment then commenced 2 h later and continued for 24 h. All treatment groups were administered the predefined CTB human-simulated regimen. Three total daily doses of CLA were evaluated per isolate: 16 mg/kg/day, 12 mg/kg/day, and 6 mg/kg/day. Each of the CLA total daily doses was fractionated into three regimens such that one-quarter, one-half, or the entire dose was administered four times, two times, or once over 24 h for a total of 3 groups per each total daily dose or 9 regimens per 3 doses.

Infected control mice (3 mice per group) were sacrificed just prior to antibiotic initiation and 24 h later. Animals sacrificed prior to antibiotic initiation served as 0-h control animals, representing the initial bacterial burden. The 24-h control animals received sterile normal saline with the same volume and schedule as those for the most frequent active-drug regimen. One group (3 mice) was administered the CTB human-simulated regimen alone to serve as a negative control. After the 24-h treatment period, all animals were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation. After sacrifice, the thighs were removed and individually homogenized in normal saline. Serial dilutions were plated onto appropriate agar media for CFU enumeration. Reductions in CFU at 24 h compared with the numbers in the starting control animals (time zero) were evaluated for each isolate to define the total reduction in log10 CFU per thigh achieved. The change in bacterial density was calculated for each of the dosing regimens. Comparisons between the effects of the three different regimens of the same total daily dose on bacterial burdens at 24 h were made by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s test, where the P value is ≤0.05.

CLA dose-ranging studies.

Mice were prepared and inoculated as described above, and treatment then commenced 2 h later and continued for 24 h. All treatment mice were administered the selected CTB human-simulated regimen. Treatment mice (3 per group) received the CTB human-simulated regimen alone or in combination with five different CLA regimens, inclusive of the human-simulated CLA regimen, and were sacrificed at the end of the 24-h period. Control animals received the diluent vehicle with the same volume, route, and schedule as those for the drug regimen. For each isolate tested, 3 infected mice (6 thighs) were used as 0-h controls, and 3 additional mice (receiving normal saline) served as 24-h controls. After the 24-h treatment period, all animals were euthanized, and thighs were cultured quantitatively as described above. Reductions in CFU at 24 h compared with the numbers in the starting control animals (time zero) were evaluated for each isolate to define the total reduction in log10 CFU per thigh achieved.

For the pharmacodynamic analysis of CLA, %fT>CT values for CT values ranging between 0.063 and 2 mg/liter were estimated for the different CLA exposures for each isolate using the bioactive, free-drug exposures as determined using values obtained from the protein binding and pharmacokinetic studies. A sigmoidal inhibitory Emax model was fitted to the data using WinNonlin (version 5.0.1; Pharsight Corp., Mountain View, CA), and the effective CLA exposure required to achieve net stasis and 1-log bacterial killing for each isolate was estimated relative to the bacterial burden achieved in the thighs of the mice receiving the CTB human-simulated regimen alone. The goodness of fit for each of these relationships was characterized using the same fitting technique.

In vivo efficacy of human-simulated exposures.

Once the mice were prepared and inoculated, as described above, groups of mice (n = 3) were treated with the human-simulated regimen of CTB alone or in combination with the human-simulated CLA regimen initiated 2 h later. Infected control mice (3 mice per group) were sacrificed just prior to antibiotic initiation and 24 h later. Animals sacrificed prior to antibiotic initiation served as 0-h control animals, representing the initial bacterial burden. The 24-h control animals received the diluent vehicle with the same volume and schedule as those for the drug regimen. After the 24-h treatment period, all animals were euthanized, and thighs were cultured quantitatively as described above. Efficacy was calculated as the change in bacterial density obtained in treated mice after 24 h compared with the numbers in the starting control animals (time zero).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Achaogen, Inc. D.P.N. has received research grants and has participated on the speakers’ bureau of the study sponsor. The other authors have nothing to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Avery LM, Nicolau DP. 2018. Investigational drugs for the treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 27:325–338. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2018.1460354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lob SH, Nicolle LE, Hoban DJ, Kazmierczak KM, Badal RE, Sahm DF. 2016. Susceptibility patterns and ESBL rates of Escherichia coli from urinary tract infections in Canada and the United States, SMART 2010–2014. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 85:459–465. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mombelli G, Pezzoli R, Pinoja-Lutz G, Monotti R, Marone C, Franciolli M. 1999. Oral vs intravenous ciprofloxacin in the initial empirical management of severe pyelonephritis or complicated urinary tract infections: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med 159:53–58. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frimodt-Moller N. 2002. Correlation between pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters and efficacy for antibiotics in the treatment of urinary tract infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents 19:546–553. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(02)00105-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pernix Therapeutics. 2010. Ceftibuten package insert. Pernix Therapeutics, LLC, Gonzales, LA. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perilli M, Segatore B, Franceschini N, Gizzi G, Mancinelli A, Caravelli B, Setacci D, del Tavio-Perez MM, Bianchi B, Amicosante G. 2001. Ceftibuten stability to active-site serine and metallo-beta-lactamases. Int J Antimicrob Agents 17:45–50. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(00)00319-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.GlaxoSmithKline. 2006. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid package insert. GlaxoSmithKline, Bridgewater, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bethel CR, Taracila M, Shyr T, Thomson JM, Distler AM, Hujer KM, Hujer AM, Endimiani A, Papp-Wallace K, Bonnet R, Bonomo RA. 2011. Exploring the inhibition of CTX-M-9 by beta-lactamase inhibitors and carbapenems. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:3465–3475. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00089-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finlay J, Miller L, Poupard JA. 2003. A review of the antimicrobial activity of clavulanate. J Antimicrob Chemother 52:18–23. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prakash V, Lewis JS, Herrera ML, Wickes BL, Jorgensen JH. 2009. Oral and parenteral therapeutic options for outpatient urinary infections caused by Enterobacteriaceae producing CTX-M extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:1278–1280. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01519-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pallett A, Hand K. 2010. Complicated urinary tract infections: practical solutions for the treatment of multiresistant Gram-negative bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother 65(Suppl 3):iii25–iii33. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pitout JD, Laupland KB. 2008. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: an emerging public-health concern. Lancet Infect Dis 8:159–166. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez-Baño J, Navarro MD, Romero L, Martínez-Martínez L, Muniain MA, Perea EJ, Pérez-Cano R, Pascual A. 2004. Epidemiology and clinical features of infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in nonhospitalized patients. J Clin Microbiol 42:1089–1094. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1089-1094.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melzer M, Petersen I. 2007. Mortality following bacteraemic infection caused by extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing E. coli compared to non-ESBL producing E. coli. J Infect 55:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kresken M, Körber-Irrgang B, Biedenbach DJ, Batista N, Besard V, Cantón R, García-Castillo M, Kalka-Moll W, Pascual A, Schwarz R, Van Meensel B, Wisplinghoff H, Seifert H. 2016. Comparative in vitro activity of oral antimicrobial agents against Enterobacteriaceae from patients with community-acquired urinary tract infections in three European countries. Clin Microbiol Infect 22:63.e1–63.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kucers A, Crowe SM, Grayson ML, Hoy JF. 1997. The use of antibiotics: a clinical review of antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral drugs, 5th ed Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lepeule R, Ruppé E, Le P, Massias L, Chau F, Nucci A, Lefort A, Fantin B. 2012. Cefoxitin as an alternative to carbapenems in a murine model of urinary tract infection due to Escherichia coli harboring CTX-M-15-type extended-spectrum β-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:1376–1381. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06233-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emery CL, Weymouth LA. 1997. Detection and clinical significance of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in a tertiary-care medical center. J Clin Microbiol 35:2061–2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suankratay C, Jutivorakool K, Jirajariyavej S. 2008. A prospective study of ceftriaxone treatment in acute pyelonephritis caused by extended spectrum beta-lactamase-producing bacteria. J Med Assoc Thai 91:1172–1181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.CLSI. 2018. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 28th ed CLSI supplement M100 CLSI, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]