Abstract

Profilin 1 is a central regulator of actin dynamics. Mutations in the gene profilin 1 (PFN1) have very recently been shown to be the cause of a subgroup of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Here, we performed a large screen of US, Nordic, and German familial and sporadic ALS and frontotemporal dementia (FTLD) patients for PFN1 mutations to get further insight into the spectrum and pathogenic relevance of this gene for the complete ALS/FTLD continuum. Four hundred twelve familial and 260 sporadic ALS cases and 16 ALS/FTLD cases from Germany, the Nordic countries, and the United States were screened for PFN1 mutations. Phenotypes of patients carrying PFN1 mutations were studied. In a German ALS family we identified the novel heterozygous PFN1 mutation p.Thr109Met, which was absent in controls. This novel mutation abrogates a phosphorylation site in profilin 1. The recently described p.Gln117Gly sequence variant was found in another familial ALS patient from the United States. The ALS patients with mutations in PFN1 displayed spinal onset motor neuron disease without overt cognitive involvement. PFN1 mutations were absent in patients with motor neuron disease and dementia, and in patients with only FTLD. We provide further evidence that PFN1 mutations can cause ALS as a Mendelian dominant trait. Patients carrying PFN1 mutations reported so far represent the “classic” ALS end of the ALS-FTLD spectrum. The novel p.Thr109Met mutation provides additional proof-of-principle that mutant proteins involved in the regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics can cause motor neuron degeneration. Moreover, this new mutation suggests that fine-tuning of actin polymerization by phosphorylation of profilin 1 might be necessary for motor neuron survival.

Keywords: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, ALS, FTLD, Profilin 1, Cytoskeleton, Actin

1. Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative syndrome characterized by adult-onset of evolving loss of primarily upper and lower motor neurons, resulting in progressive paralysis and ultimately death from respiratory failure (Kiernan et al., 2011). In different populations, 1%—19% of patients report a familial predisposition for ALS (fALS) (Chio et al., 2008, 2011a, 2011b; Eisen et al., 2008; Haverkamp et al., 1995; Li et al., 1988), the remainders are isolated or sporadic ALS of unknown cause (denoted sALS). Since 1993, mutations in 15 genes have been associated with causing ALS. In Western Caucasian populations, the most frequently mutated genes in fALS appear to be C9ORF72 (DeJesus-Hernandez et al., 2011; Renton et al., 2011), SOD1 (Rosen et al., 1993), FUS/TLS (Kwiatkowski et al., 2009; Vance et al., 2009), and TARDBP (Gitcho et al., 2008; Kabashi et al., 2008; Sreedharan et al., 2008). When mutated, several of these genes have been demonstrated to be pleiotropic with involvement of other parts of the nervous system and have been associated with also causing frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) and Parkinsonism (reviewed in Andersen and Al-Chalabi 2011). However, the identified genes explain only 40%—60% of familial ALS cases in Western (Caucasian) populations and less in non-Caucasian populations (Andersen and Al-Chalabi 2011).

Very recently, exome sequencing of 2 large pedigrees with autosomal dominant ALS revealed p.Cys71Gly and p.Met114Thr missense mutations in the profilin 1 (PFN1) gene cosegregating with disease in all affected individuals in either family (Wu et al., 2012). The mutations were absent in most older unaffected family members and in 7560 control samples. Sequencing DNA from 274 additional fALS cases showed 7 cases carrying 1 of 4 non-synonymous mutations p.Cys71Gly, p.Met114Thr, p.Gln117Gly, and p.Gly118Val mutations. Two of 816 apparent sALS cases also carried the p.Gln117Gly PFN1 mutation (Wu et al., 2012). Lending further support for pathogenicity in ALS is the known biological function of Profilin 1. Profilin 1 is a small 140 amino acid protein that is essential for the polymerization of monomeric G-actin to filamentous-actin (Witke 2004). This is in line with the fact that variants in 4 other genes encoding proteins involved in cytoskeletal pathways, peripherin, spastin, NF-H and DCTN1, have earlier been suggested to contribute to ALS pathogenesis (Figlewicz et al., 1994; Gros-Louis et al., 2004; Munch et al., 2004, 2008).

Suggesting a function of profilin 1 also beyond actin regulation, it binds to a number of other proteins including huntingtin or the spinal muscular atrophy related protein, SMN (Giesemann et al., 1999; Witke 2004). SMN1 is also involved in axonal transport processes (Fallini et al., 2012) and therefore provides another possible link between profilin 1 and axonal integrity.

The recent findings prompted us to study the PFN1 gene in a large cohort of German, Nordic, and US ALS and FTLD patients. We aimed to further define the relevance and spectrum of PFN1 mutations in different ALS but also FTLD cohorts.

2. Methods

With informed written consent and approval by the national medical ethical review boards in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (WMA, 1964), blood samples were drawn from 244 Nordic fALS and 16 FTLD patients, 108 fALS and 260 sALS patients from Germany, as well as 60 US fALS samples not included in Wu et al., (2012). At least 1 index case from each family was seen by an ALS specialist. The demographics of the study cohorts are summarized in Table 1. The fALS cases included were defined as having a familial history of ALS according to the definition of Byrne et al., (2011), and fulfilling the El-Escorial criteria for ALS (Brooks et al., 2000). Most samples had been prescreened for mutations in a number of other ALS-associated genes. Of the Nordic samples, 102 samples were from patients without mutations in any ALS-associated genes (SOD1, ANG, CHMP2B, FUS/TLS, OPTN, PGRN, SIGMAR1, ITPR2, TARDBP, UBQLN2, VAPB, and C9ORF72 genes; details available upon request). However, we also screened an additional 158 Nordic patients including individuals with identified mutations in other fALS genes (C9ORF72, SOD1, FUS/TLS, VAPB, TARDBP, OPTN; for details see Supplementary Table 1) to test the hypothesis that mutations in PFN1 could be part of oligomutant fALS as has recently been claimed for C9ORF72 and TARDBP (Chio et al., 2012; Kaivorinne et al., 2012; van Blitterswijk et al., 2012) and tends to occur in conserved populations. For the same reason 49 out of the 108 German fALS cases were included despite mutations detected in a prescreening for SOD1, TARDBP, C9ORF72, FUS, and OPTN mutations. The individuals harboring a PFN1 mutation mentioned in this report did not carry a mutation in any of the above-mentioned genes. For the Nordic and the German fALS cohort the numbers of mutations in specific known ALS genes are given in Supplementary Table 1. The sALS cases included in this study were not prescreened for other genes. US fALS cases with mutations detected in the prescreening were excluded (i.e., mutations in SOD1, TARDBP, C9ORF72, FUS, and OPTN were absent in the cohort of 60 fALS patients from the United States).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study populations

| Age at onset, mean ± SD (y) | Sex distribution (m:f) | Bulbar onset (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| US fALS cohort (n = 60) | 56.4 ± 13.0 | 1:1.5 | 23.3 |

| Nordic fALS cohort (n = 244) | 52.1 ± 14.9 | 1:0.35 | 25.8 |

| German fALS cohort (n = 108) | 50.3 ± 13.5 | 1:0.65 | 18.9 |

| German sALS cohort (n = 260) | 58.6 ± 11.5 | 1:0.75 | 32.3 |

| Nordic FTLD cohort (n = 16)a.b | 55.9 ± 8.0 | 1:1 | Not applicable |

| German control cohort (n = 604) | 49.7 (at sample collection); range, 20.0–81.0 | 1:0.79 | Not applicable |

| Nordic control cohort (n = 368) | ND | ND | Not applicable |

Key: ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; f, female; fALS, familial ALS; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration; m, male; ND, not determined/available; sALS, sporadic ALS.

The Nordic ALS and FTLD patients were from single families from Sweden (158), Finland (39), Denmark (37) and Norway (26).

Nine of the 16 patients with cognitive impairment and dementia as first symptom later developed ALS, and the other 7 had a pure FTLD phenotype throughout their disease course. All 16 cases had blood relatives with ALS without overt cognitive involvement.

Genomic DNA was extracted from buffy coat cells with the Nucleon BACC2 DNA extraction kit (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) or the FlexiGene DNA kit (Qiagen, GmbH, Germany) according to the manufacturers’ protocols. DNA from German patients was derived from immortalized lymphoblast cultures. All 3 exons and at least 10 base pairs of flanking intron sequences were amplified and sequenced as described in Wu et al. (2012) and compared with the PFN1 reference sequence (GenBank entry NM_005022). Specific screening for the novel mutation p.Thr109Met was performed using a TaqMan genotyping assay (Applied Biosystems) or by an enzymatic digestion with TspR1 after polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. Primer sequences and reaction conditions are available upon request. Screening for the hexanuxelotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 was performed by repeat-primed PCR (DeJesus-Hernandez et al., 2011; Renton et al., 2011) (Nordic and US cases) or a 3-step approach with PCR fragment analysis followed by repeat-primed PCR and confirmation of repeat expansions by Southern blot analysis (German samples; Southern blot protocol unpublished, manuscript in preparation).

3. Results

The genetic analysis of all 3 coding exons of PFN1 was performed in 412 fALS patients (244 Nordic, 108 German, 60 US), 260 German sALS, and 16 Nordic FTLD patients. Most of the fALS patients were prescreened for the most frequent ALS genes, but included in the study independent of their genetic status, because recent evidence suggests that mutations in a known ALS gene do not exclude a “second hit” (Chio et al., 2012; Kaivorinne et al., 2012; van Blitterswijk et al., 2012) (for respective details of the study cohorts see Table 1 and the Methods section).

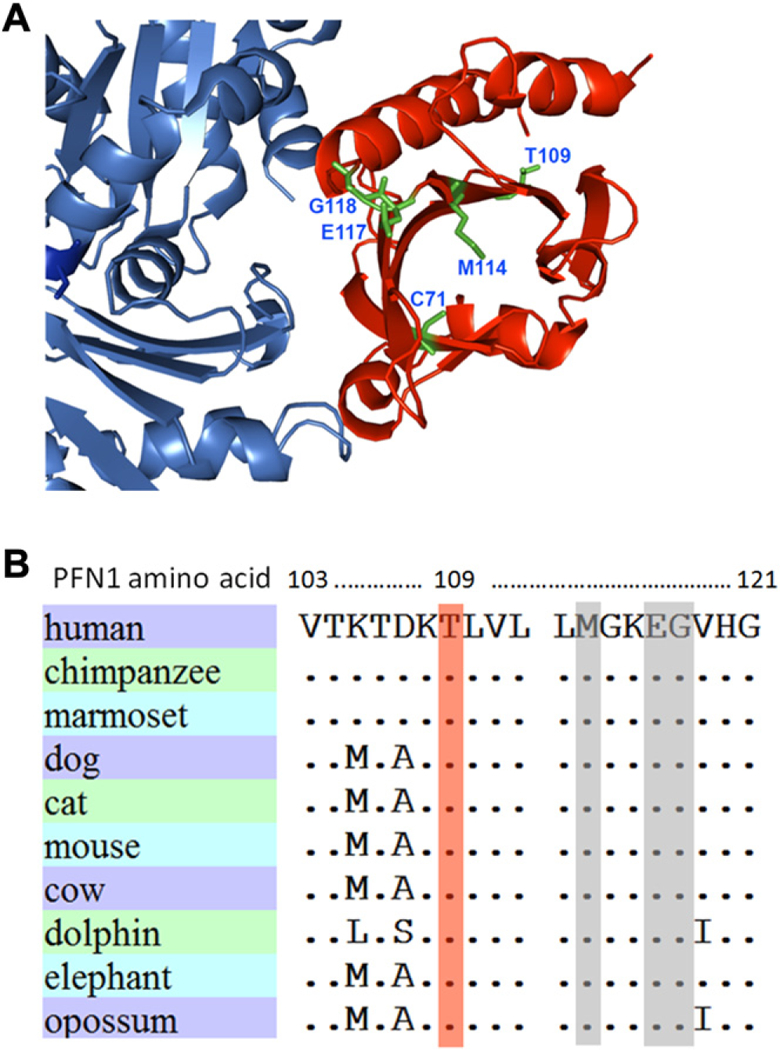

We identified a novel nonsynonymous mutation c.326C>T (p.Thr109Met) in a German ALS family. This mutation is not listed in the Exome Variant Server (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), which covers approximately 4300 individuals of European American and 2203 of African American ancestry at this position. Moreover, this mutation is not listed in the 1000 Genomes database (http://browser.1000genomes.org/index.html) containing data for the PFN1 gene of1092 individuals, including 379 individuals of European ancestry. Additionally, we did not find this mutation in 604 unrelated, healthy German controls or in 368 Nordic controls. Thus, taken together the information from publicly accessible databases and our own screening results, the novel mutation was absent in 5651 individuals of European ancestry and a total of 8567 DNA samples worldwide, strongly supporting the pathogenic relevance of the mutation. Thr109 is positioned close to the actin binding domain of profilin 1 and contributes to a cluster together with 4 out of 5 recently reported PFN1 ALS mutations in very close proximity (Fig. 1A and B). This amino acid is highly conserved among vertebrates (Fig. 1B), and has been shown to be subject to phosphorylation by mass spectrometry analysis (see Supplementary Table 2 in Olsen et al., 2010). In addition, among the 60 US fALS patients, the recently described p.Gln117Gly sequence variant, which is of unclear pathogenicity so far, was detected in an unrelated patient. In contrast, nonsynonymous mutations were absent in the 244 Nordic fALS and 16 FTLD patients, and among the 260 German sALS cases. Sequencing of at least 10 base pairs of the adjacent introns in addition to the complete PFN1 coding sequence revealed no sequence variations predicted to alter splicing of the PFN1 transcript. Mutations in the SOD1, C9ORF72, FUS/TLS, TARDBP, UBQLN, and OPTN genes were excluded in the 2 patients of this study carrying the PFN1 mutations.

Fig. 1.

Position and evolutionary conservation of PFN1 mutations. (A) Threedimensional illustration of the novel p.Thr109Met mutation from this work and the 4 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mutations from Wu et al. (2012) (Protein Data Bank accession 2BTF). Blue: actin; red: profilin 1. In (B) the evolutionary conservation of the novel PFN1 mutation p.Thr109Met is shown. The mutated threonine residue is colored in light red. Three out of the 4 mutations identified by Wu et al. (2012) are located in close proximity and shadowed in gray.

Both patients had limb onset disease. Age of onset was 54 years in the male US patient (p.Gln117Gly), and 48 years in the German female patient (p.Thr109Met) (clinical features are summarized in Table 2). The latter required supportive noninvasive ventilation 7 years after onset of disease on which she became completely dependent within approximately 3—4 years. Eight years after onset, she was using a wheel chair, but still able to walk 10—20 meters with support. Since then she has slowly developed complete tetraplegia. Bulbar signs and symptoms including dysarthria, dysphagia, and tongue atrophy, were first observed 7 years after onset. She now communicates with a computerized eye gaze system. Because of the severe peripheral denervation, signs of upper motor neuron affection cannot be tested. However, brisk deep tendon as well as pathologic masseter muscle reflexes and bilateral Babinski’s signs were observed earlier in the disease course. Electromyographic studies confirmed the acute and chronic denervation, and motor nerve conduction velocities that were normal to marginally decreased when performed 9 years after onset, without documentation of sensory neurography results. Test for GM1-autoantibodies was negative.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients from families with PFN1 mutations

| Family | Mutation | Sex | Age at onset (y) |

Disease duration (mo) |

Disease onset |

UMN signs | LMN signs | Dementia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (US patient) | PFN1p.Gln117Gly | M | 54 | NA | spinal | NA | NA | – |

| 2 (German patients) | PFN1p.Thr109Met | F | 48 | >336a | spinal | + | + | – |

| PFN1p.Thr109Met | F | 70 | >144a | spinal | NA | NA | – | |

| No DNA available for genetic testing | F | 55 | 24 | bulbar | NA | NA | – | |

Key: +, present; –, absent; LMN, lower motor neuron; NA, not applicable (unknown); UMN, upper motor neuron.

Patient is still alive.

No ALS or symptoms indicative of a motor neuron disease, FTLD, or psychosis are reported among the parents and grandparents of the patient carrying the p.Thr109Met mutation, including the 7 uncles and aunts of the index patient from which detailed medical information is available (not displayed in Fig. 2). A sister of the index patient died from ALS with a disease course of 2 years. Unfortunately, no DNA is available from her. Another sister of the index patient also carries the novel PFN1 mutation and is now 82 years old. She complains about a slowly progressive, asymmetric paraparesis for 12 years, and has become wheel chair bound. Although the patient provided a blood sample for genetic testing, she declined further medical work-up.

Fig. 2.

Pedigree of the German amyotrophic lateral sclerosis family with the missense PFN1 mutation p.Thr109Met. Arrow indicates the index patient. Genotypes of available DNA samples for the PFN1 mutation are shown (‘w’ denotes wild type, ‘m’ denotes mutant). For patient III/1 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis diagnosis could not be confirmed or excluded based on the retrospective information.

A DNA sample was available from another deceased sibling, who also carried the PFN1 mutation. Unfortunately, only incomplete medical information could be obtained about this patient, who died at the age of 86 years of a “paretic condition” without ever receiving a diagnosis of ALS. He was not demented at the time of his death.

A sibling died from cardiac ischemia at the age of 83 years. This individual did not carry the PFN1 mutation. Three children of the index patient are in their mid-forties and none of them complain about neuromuscular symptoms. Thus, although we could not prove complete segregation, the mode of inheritance of the p.Thr109Met PFN1 mutation family is compatible with an auto-somal dominant trait, but it is not possible to estimate the disease penetrance.

A detailed history and DNA samples were unavailable from the US fALS family carrying the p.Gln117Gly mutation.

4. Discussion

In this large screen for PFN1 mutations in US and European ALS and FTLD patients we are able to provide further support for PFN1 as a causative but rare gene in ALS. This includes the discovery of a novel missense mutation, which alters a phosphorylation site close to the actin binding domain of profilin 1. Moreover, we excluded PFN1 mutations in 9 ALS-FTLD and 7 FTLD-only cases.

Several points of evidence suggest that the novel p.Thr109Met mutation is pathogenic. We could show partial cosegregation of the mutation, although a brother of the index patient could not be confirmed to have suffered from ALS based on the scarce medical information that is available. However, incomplete penetrance is not unusual in a late-onset disease like ALS, and was also observed with the initially described families segregating a PFN1 mutation (Wu et al., 2012). The 3 healthy children of the index patient are currently in their mid 40s. Importantly, taking together information from publicly available databases and our own screening results, the p.Thr109Met mutation has not been found among 8567 control individuals worldwide, of which are 5651 of European ancestry, including 630 and 368 of our own German and Nordic control samples, respectively. Additional arguments for the pathogenicity of the PFN1p Thr109Met mutation are the location and nature of this sequence alteration: although Thr109 in profilin 1 is not part of an actin binding domain as the previously detected mutations (Wu et al., 2012), it is located only few amino acids apart from 3 out of the 4 other recently identified mutations in profilin 1 which might point to a mutation “hot spot” (Wu et al., 2012). In addition, the sequence alteration abolishes a threonine residue that is a known phosphorylation site (Olsen et al., 2010). Although the biological function of phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of PFN1 at Thr109 is unknown at present, the finding that a phosphorylation site is omitted in our patient additionally suggests that this mutation might result in altered protein function. Finally, despite substantial interspecies variation within the same profilin protein family members (Witke, 2004), p.Thr109 in profilin 1 is highly conserved in mammals (Fig. 1B), further suggesting that it is functionally critical.

Even though the index patient has a large and well-documented family, we were unable to find any evidence for ALS or FTLD in earlier generations. This might point to a reduced penetrance associated with the p.Thr109Met mutation. Additionally, undisclosed paternity or a de novo mutation event cannot be ruled out. De novo mutations have earlier been documented in ALS patients with SOD1 or FUS/TLS gene mutations (Alexander et al., 2002; Chio et al., 2011a, 2011b; DeJesus-Hernandez et al., 2010).

The sequence variant p.Gln117Gly detected in our study was recently reported both in sporadic and familial ALS patients in another study (Wu et al., 2012). In contrast to the recently described PFN1 mutations it was also found in few control samples, does not change actin binding of profilin 1, and results in an only mildly increased tendency to form aggregates compared with the wild-type protein (Wu et al., 2012). However, the fact that this sequence alteration was found to have an approximately 7-fold higher allele frequency in ALS compared with controls (Wu et al.,2012), the finding that it affects a functionally critical position in the PFN1 actin binding domain together with results from cell biological experiments suggest that a pathogenic role cannot be ruled out. Nevertheless, it has to be emphasized that p.Gln117Gly could also be completely nonpathogenic.

To our knowledge, all 25 PFN1 mutation carriers identified to date are associated with a spinal onset ALS phenotype (this work and Wu et al., 2012). Predominantly spinal onset might be a distinguishing feature for patients with PFN1 mutations, in line with what has earlier been observed in ALS patients with SOD1 or TARDBP gene mutations (Andersen and Al-Chalabi, 2011). However, the sister of our patient carrying the p.Thr109Met mutation reportedly died of bulbar ALS within 2 years after diagnosis. Unfortunately, no DNA is available from her to confirm or exclude a potential PFN1 mutation.

No signs of dementia or behavioral abnormalities typical for the presence of FTLD were observed in any of the PFN1 -associated ALS patients reported so far (this study and Wu et al., 2012). PFN1-associated ALS cases thus seem to represent predominantly the ALS end of the ALS/FTLD disease spectrum, an assumption that is in agreement with the absence of PFN1 mutations among the ALS-FTLD and FTLD patients in this study. However, larger sample numbers might be required to exclude that PFN1 sequence alterations causing FTLD in rare instances.

Together with the recent discovery of 4 other mutations in a few percent of fALS cases of Caucasian (US, Italian) and Sephardic Jewish origin (Wu et al., 2012) our results (US, Nordic, and German patients) add significantly to the understanding of the role of cytoskeletal abnormalities in ALS. Sequence variants in other genes that affect the cytoskeleton and axonal transport (e.g. NF-H and DCTN1; Figlewicz et al., 1994; Munch et al., 2004), have been suggested to contribute to ALS pathogenesis. The results of Wu et al. (2012) and our study provide proof-of-principle that mutations in a gene that regulates actin cytokeletal dynamics can affect moto-neuron integrity in a monogenic, autosomal dominantly inherited manner. Subtle modulation of cytoskeletal dynamics is crucial for a large number of neuron-specific functions (e.g., neurite outgrowth or synaptic vesicle recycling). Because of their long axonal projections, motor neurons might be particularly susceptible to disturbance in proper cytoskeleton function and subsequently axonal transport processes.

However, whether toxicity of the novel Thr109Met mutation is indeed related to an altered interaction with actin remains to be confirmed in biological experiments. Thr109 is not directly involved in actin binding of PFN1 (see Fig. 1A), although together with 3 of the previously identified ALS mutations it forms an apparent cluster within a stretch of 9 amino acids (Wu et al., 2012). Apart from the regulation of actin dynamics, profilin 1 might be involved in the complex regulation of a broad array of other cellular processes. This is underscored by more than 50 potential profilin binding partners that have been identified (Witke 2004), amongst which are 3 that play a role in neurodegenerative diseases: Valosin-containing protein (VCP; ALS/FTLD, inclusion body myositis, Paget’s disease) (Witke et al., 1998), SMN protein (spinal muscular atrophy) (Giesemann et al., 1999) and huntingtin (Lund-Huntington’s disease) (Witke, 2004). Therefore, binding partners other than actin could principally also contribute to toxic effects of the p.Thr109Met mutation in PFN1. Of note, the novel p.Thr109Met mutation abolishes a proven phosphorylation site in profilin 1 ( in Olsen et al., 2010), and its surface exposure according to the model presented in Fig. 1A makes it principally well accessible for kinases. Although the biological function of profilin 1 Thr109 phospho-modification is unknown so far, this raises the interesting possibility that altered profilin 1 phosphorylation might contribute to ALS pathogenesis or neurodegeneration in general. Interestingly, though little is known about the biological function of other phosphorylation sites in mammalian profilin 1, phosphorylation of Tyr137 in profilin 1 by ROCK kinases reduced its binding to polyglutamine proteins, and enhanced their aggregation (Shao et al., 2008).

Overall, our data confirm that PFN1 mutations, though in rare instances, can cause ALS in a dominant manner. The discovery provides proof-of-principle evidence that mutations in a protein involved in the regulation of actin cytoskeletal abnormalities can cause motor neuron degeneration, although other profilin 1 binding partners could also be relevant. The nature of the novel mutation discovered in this study allows hypothesizing that impaired phosphorylation of profilin 1 might contribute to motoneuron degeneration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the patients and their families for their participation in this project. We thank the clinicians who referred the patients to us. The work was supported by grants from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (01G10704; network for ALS research [MND-NET]), the Charcot Foundation for ALS Research (ACL, JHW), the Swedish Brain Power Consortium, the Swedish Brain Research Foundation, the Bertil Hàllsten Research Foundation (PMA), the N1H/N1NDS to J.E.L. (1R01NS065847). The study was also supported by the Swabian ALS Registry. The skillful technical assistance and patient care of Nadine Todt, Antje Knehr, Ann-Charloth Nilsson, and Helena Alstermark is gratefully acknowledged. The authors thank the 1000 Genome project and NHLB1 GO Exome Sequencing Project and its ongoing studies which produced and provided exome variant calls for comparison: the Lung GO Sequencing Project (HL-102923), the WH1 Sequencing Project (HL-102924), the Broad GO Sequencing Project (HL-102925), the Seattle GO Sequencing Project (HL-102926), and the Heart GO Sequencing Project (HL-103010).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

Appropriate approval and procedures were used concerning human subjects and animals.

All authors report no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.10.009.

References

- Alexander MD, Traynor BJ, Miller N, Corr B, Frost E, McQuaid S, Brett FM, Green A, Hardiman O, 2002. “True” sporadic ALS associated with a novel SOD-1 mutation. Ann. Neurol. 52, 680–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen PM, Al-Chalabi A, 2011. Clinical genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: what do we really know? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 7, 603–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL, World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Motor Neuron Diseases, 2000. El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Other Motor Neuron Disord 1, 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne S, Bede P, Elamin M, Kenna K, Lynch C, McLaughlin R, Hardiman O,2011. Proposed criteria for familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 12, 157–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chio A, Borghero G, Pugliatti M, Ticca A, Calvo A, Moglia C, Mutani R, Brunetti M, Ossola I, Marrosu MG, Murru MR, Floris G, Cannas A, Parish LD, Cossu P, Abramzon Y, Johnson JO, Nalls MA, Arepalli S, Chong S, Hernandez DG, Traynor BJ, Restagno G, 2011a. Large proportion of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis cases in Sardinia due to a single founder mutation of the tArDBP gene. Arch. Neurol. 68, 594–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chio A, Calvo A, Moglia C, Ossola I, Brunetti M, Sbaiz L, Lai SL, Abramzon Y, Traynor BJ, Restagno G, 2011b. A de novo missense mutation of the FUS gene in a “true” sporadic ALS case. Neurobiol. Aging 32, 553.e523–553.e556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chio A, Restagno G, Brunetti M, Ossola I, Calvo A, Canosa A, Moglia C, Floris G, Tacconi P, Marrosu F, Marrosu MG, Murru MR, Majounie E, Renton AE, Abramzon Y, Pugliatti M, Sotgiu MA, Traynor BJ, Borghero G,2012. ALS/FTD phenotype in two Sardinian families carrying both C9ORF72 and TARDBP mutations. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 83, 730–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chio A, Traynor BJ, Lombardo F, Fimognari M, Calvo A, Ghiglione P, Mutani R, Restagno G, 2008. Prevalence of SOD1 mutations in the Italian ALS population. Neurology 70, 533–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJesus-Hernandez M, Kocerha J, Finch N, Crook R, Baker M, Desaro P, Johnston A, Rutherford N, Wojtas A, Kennelly K, Wszolek ZK, Graff-Radford N, Boylan K, Rademakers R, 2010. De novo truncating FUS gene mutation as a cause of sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum. Mutat 31, E1377–E1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, Boxer AL, Baker M, Rutherford NJ, Nicholson AM, Finch NA, Flynn H, Adamson J, Kouri N, Wojtas A, Sengdy P, Hsiung GY, Karydas A, Seeley WW, Josephs KA, Coppola G, Geschwind DH, Wszolek ZK, Feldman HBL, Dickson W, Boylan KB, Graff-Radford NR, Rademakers R, 2011. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 72, 245–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen A, Mezei MM, Stewart HG, Fabros M, Gibson G, Andersen PM, 2008. SOD1 gene mutations in ALS patients from British Columbia, Canada: clinical features, neurophysiology and ethical issues in management. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 9, 108–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallini C, Bassell GJ, Rossoll W, 2012. Spinal muscular atrophy: the role of SMN in axonal mRNA regulation. Brain Res. 1462, 81–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figlewicz DA, Krizus A, Martinoli MG, Meininger V, Dib M, Rouleau GA, Julien JP, 1994. Variants of the heavy neurofilament subunit are associated with the development of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 3, 1757–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesemann T, Rathke-Hartlieb S, Rothkegel M, Bartsch JW, Buchmeier S, Jockusch BM, Jockusch H, 1999. A role for polyproline motifs in the spinal muscular atrophy protein SMN. Profilins bind to and colocalize with SMN in nuclear gems. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 37908–37914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitcho MA, Baloh RH, Chakraverty S, Mayo K, Norton JB, Levitch D, Hatanpaa KJ, White CL 3rd, Bigio EH, Caselli R, Baker M, Al-Lozi MT, Morris JC, Pestronk A, Rademakers R, Goate AM, Cairns NJ, 2008. TDP-43 A315T mutation in familial motor neuron disease. Ann. Neurol. 63, 535–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros-Louis F, Lariviere R, Gowing G, Laurent S, Camu W, Bouchard JP, Meininger V, Rouleau GA, Julien JP, 2004. A frameshift deletion in peripherin gene associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45951–45956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverkamp LJ, Appel V, Appel SH, 1995. Natural history of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in a database population. Validation of a scoring system and a model for survival prediction. Brain 118, 707–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabashi E, Valdmanis PN, Dion P, Spiegelman D, McConkey BJ, Vande Velde C, Bouchard JP, Lacomblez L, Pochigaeva K, Salachas F, Pradat PF, Camu W, Meininger V, Dupre N, Rouleau GA, 2008. TARDBP mutations in individuals with sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Genet 40, 572–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaivorinne AL, Moilanen V, Kervinen M, Renton AE, Traynor BJ, Majamaa K, Remes AM, 2012. Novel TARDBP sequence variant and C9ORF72 repeat expansion in a family with frontotemporal dementia. Alzheimer. Dis. Assoc. Disord., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan MC, Vucic S, Cheah BC, Turner MR, Eisen A, Hardiman O, Burrell JR, Zoing MC, 2011. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 377, 942–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski TJ Jr., Bosco DA, Leclerc AL, Tamrazian E, Vanderburg CR, Russ C, Davis A, Gilchrist J, Kasarskis EJ, Munsat T, Valdmanis P, Rouleau GA, Hosler BA, Cortelli P, de Jong PJ, Yoshinaga Y, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Yan J, Ticozzi N, Siddique T, McKenna-Yasek D, Sapp PC, Horvitz HR, Landers JE, Brown RH Jr., 2009. Mutations in the FUS/TLS gene on chromosome 16 cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 323, 1205–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TM, Alberman E, Swash M, 1988. Comparison of sporadic and familial disease amongst 580 cases of motor neuron disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 51, 778–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munch C, Rolfs A, Meyer T, 2008. Heterozygous S44L missense change of the spastin gene in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral. Scler. 9, 251–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munch C, Sedlmeier R, Meyer T, Homberg V, Sperfeld AD, Kurt A, Prudlo J, Peraus G, Hanemann CO, Stumm G, Ludolph AC, 2004. Point mutations of the p150 subunit of dynactin (DCTN1) gene in ALS. Neurology 63, 724–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JV, Vermeulen M, Santamaria A, Kumar C, Miller ML, Jensen LJ, Gnad F, Cox J, Jensen TS, Nigg EA, Brunak S, Mann M, 2010. Quantitative phosphoproteomics reveals widespread full phosphorylation site occupancy during mitosis. Sci. Signal 3, ra3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renton AE, Majounie E, Waite A, Simon-Sanchez J, Rollinson S, Gibbs JR, Schymick JC, Laaksovirta H, van Swieten JC, Myllykangas L, Kalimo H, Paetau A, Abramzon Y, Remes AM, Kaganovich A, Scholz SW, Duckworth J, Ding J, Harmer DW, Hernandez DG, Johnson JO, Mok K, Ryten M, Trabzuni D, Guerreiro RJ, Orrell RW, Neal J, Murray A, Pearson J, Jansen IE, Sondervan D, Seelaar H, Blake D, Young K, Halliwell N, Callister JB, Toulson G, Richardson A, Gerhard A, Snowden J, Mann D, Neary D, Nalls MA, Peuralinna T, Jansson L, Isoviita VM, Kaivorinne AL, Holtta-Vuori M, Ikonen E, Sulkava R, Benatar M, Wuu J, Chio A, Restagno G, Borghero G, Sabatelli M, Heckerman D, Rogaeva E, Zinman L, Rothstein JD, Sendtner M, Drepper C, Eichler EE, Alkan C, Abdullaev Z, Pack SD, Dutra A, Pak E, Hardy J, Singleton A, Williams NM, Heutink P, Pickering-Brown S, Morris HR, Tienari PJ, Traynor BJ, 2011. A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 72, 257–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen DR, Siddique T, Patterson D, Figlewicz DA, Sapp P, Hentati A, Donaldson D, Goto J, O’Regan JP, Deng HX, Rahmani Z, Krizus A, McKenna-Yasek D, Cayabyab A, Gaston SM, Berger R, Tanzi RE, Halperin JJ, Herzfeldt B, Van den Bergh R, Hung W-Y, Bird T, Deng G, Mulder DW, Smyth C, Laing NG, Soriano E, Pericak-Vane MA, Haines J, Rouleau GA, Gusella JS, Horvitz HR, Brown RH Jr., 1993. Mutations in Cu/ Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [erratum in 1993;364:362]. Nature 362, 59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao J, Welch WJ, Diprospero NA, Diamond MI, 2008. Phosphorylation of profilin by ROCKI regulates polyglutamine aggregation. Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 5196–5208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreedharan J, Blair IP, Tripathi VB, Hu X, Vance C, Rogelj B, Ackerley S, Durnall JC, Williams KL, Buratti E, Baralle F, de Belleroche J, Mitchell JD, Leigh PN, Al-Chalabi A, Miller CC, Nicholson G, Shaw CE, 2008. TDP-43 mutations in familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 319, 1668–1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Blitterswijk M, van Es MA, Hennekam EA, Dooijes D, van Rheenen W, Medic J, Bourque PR, Schelhaas HJ, van der Kooi AJ, de Visser M, de Bakker PI, Veldink JH, van den Berg LH, 2012. Evidence for an oligogenic basis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum. Mol. Genet 21, 3776–3784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance C, Rogelj B, Hortobagyi T, De Vos KJ, Nishimura AL, Sreedharan J, Hu X, Smith B, Ruddy D, Wright P, Ganesalingam J, Williams KL, Tripathi V, Al-Saraj S, Al-Chalabi A, Leigh PN, Blair IP, Nicholson G, de Belleroche J, Gallo JM, Miller CC, Shaw CE, 2009. Mutations in FUS, an RNA processing protein, cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis type 6. Science 323,1208–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witke W, 2004. The role of profilin complexes in cell motility and other cellular processes. Trends Cell Biol. 14, 461–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witke W, Podtelejnikov AV, Di Nardo A, Sutherland JD, Gurniak CB, Dotti C, Mann M, 1998. In mouse brain profilin I and profilin II associate with regulators of the endocytic pathway and actin assembly. EMBO J 17, 967–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CH, Fallini C, Ticozzi N, Keagle PJ, Sapp PC, Piotrowska K, Lowe P, Koppers M, McKenna-Yasek D, Baron DM, Kost JE, Gonzalez-Perez P, Fox AD, Adams J, Taroni F, Tiloca C, Leclerc AL, Chafe SC, Mangroo D, Moore MJ, Zitzewitz JA, Xu ZS, van den Berg LH, Glass JD, Siciliano G, Cirulli ET, Goldstein DB, Salachas F, Meininger V, Rossoll W, Ratti A, Gellera C, Bosco DA, Bassell GJ, Silani V, Drory VE, Brown RH, Landers JE, 2012. Mutations in the profilin 1 gene cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature 488, 499–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.