Abstract

This meta-analysis estimates the overall efficacy of HIV prevention interventions to reduce HIV sexual risk behaviors and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among heterosexual African American men. A comprehensive search of the literature published during 1988–2008 yielded 44 relevant studies. Interventions significantly reduced HIV sexual risk behaviors and STIs. The stratified analysis for HIV sexual risk behaviors indicated that interventions were efficacious for studies specifically targeting African American men and men with incarceration history. In addition, interventions that had provision/referral of medical services, male facilitators, shorter follow-up periods, or emphasized the importance of protecting family and significant others were associated with reductions in HIV sexual risk behaviors. Meta-regression analyses indicated that the most robust intervention component is the provision/referral of medical services. Findings indicate that HIV interventions for heterosexual African American men might be more efficacious if they incorporated a range of health care services rather than HIV/STI-related services alone.

Keywords: HIV intervention, African, American, Heterosexual, Meta-analysis Men

Introduction

African Americans have a disproportionately high rate of HIV infections via sexual contact in the US [1]. Among U.S. males, African Americans account for 63% of HIV transmissions through high-risk heterosexual contact compared to 13% whites and 21% Hispanics [1]. In addition, nearly half of the recent HIV cases among African American females (44%) are attributed to high-risk heterosexual contact [1]. Since the majority of sex partner networks are intra-racial [2, 3], interventions designed to reduce risky sexual behaviors among heterosexual African American men have great potential to substantially reduce HIV infection in the entire African American community. For our paper, we operationalize heterosexual African American men as African American men who report having sex with women.

Incorporating factors that influence HIV sexual risk behaviors of heterosexual African American men is critical to the efficacy of HIV behavioral interventions for this at-risk population [4]. One important factor is machismo [5]. Machismo is an ideology present in the African American community [5, 6] (as well as others [7, 8]) that emphasizes perpetual male dominance over females and is characterized by an overemphasis in male sexual prowess, female subordination, and heterosexuality [5–8]. Black men who conform to this ideology are less motivated to engage in safer behavior and are more likely to adopt negative attitudes toward condom use [5], engage in inconsistent condom use, and have multiple sex partners [9–11]. Although measured in various ways [12], men who adhere to a traditional gender role are more likely to show behavioral traits consistent with machismo. On the other hand, machismo may integrate traditional roles that emphasize the importance of men as heads of families and related responsibilities to protect partner and family [6]. In this regard, machismo could help create a sense of responsibility to reduce HIV risk that is aligned with a sense of manhood [5]. This attitude may thus result in practicing behaviors that protect the man and his sex partners. In other words, machismo may be a risk factor as well as a protective factor, depending on whether male dominance or responsibility is emphasized.

Some structural challenges may impede the ability of heterosexual African American men to maintain the responsibilities to protect partner and self. Poverty, incarceration, and disparities in health care have been correlated with the risk of HIV infection [13–15]. African Americans are disproportionately affected by poverty [16, 17]; in turn, poverty has been correlated with disparity in health care insurance among African Americans compared with whites [17]. The rate of incarceration is also disproportionately high among African Americans. Incarceration reduces opportunities to earn income and thus limits opportunities to break out of the poverty cycle, which in turn affects health care [18, 19]. African American men are also more likely than white men to receive delayed diagnoses and treatment for chronic diseases (including HIV infection) [20–22].

Interventions to reduce risky sexual behaviors among African Americans have been evaluated in a few recently published meta-analyses [22–25]; however, none of these reviews specifically examined factors associated with intervention efficacy for heterosexual African American men. All of these meta-analyses pointed out the importance of intensive skills training to increase the ability to negotiate safer sex [22–25], especially for African American women [25]. For heterosexual African American men, who generally have more power in a relationship, skills for negotiating safer sex may be less influential than social (e.g., machismo) and structural factors (e.g., poverty, incarceration, health care access) on impacting one’s HIV risk. Our review expands the scope of previously published meta-analyses by directly testing whether studies addressing social and structural factors that disproportionally impact African American men would be more efficacious in reducing HIV risk. We also examined factors derived from behavioral change theories (e.g., knowledge, attitude toward condom use, motivation, skills building) that may be associated with intervention effects for this high risk population.

Methods

Data Sources

We searched the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) project cumulative database of the HIV/AIDS and STI behavioral prevention research literature from June 2007 through May 2008 [26, 27] to locate reports of interventions, published during January 1988–May 2008. The PRS database was developed using a comprehensive search of five electronic bibliographic databases, including AIDSLINE (1988–2000), EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Sociological Abstracts from 1988 through 2008. These searches were performed by two subject-expert librarians, who used standardized search terms (i.e., indexing terms and keywords) in 3 areas:

HIV, AIDS, or STI

Intervention evaluation

Behavioral or biological outcomes

The reports had to have one search term in each of the three areas. We used the same constructs to manually search 35 journals that regularly publish HIV or STI prevention research. Additional auxiliary searches include checking citations posted on Malow’s list (Robert M. Maslow, PhD, HIV Listserv, http://www.robertmalow.org/), reference lists of pertinent articles for relevant reports, and contacting authors for their upcoming publications.

Study Selection

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

U.S.-based behavioral intervention intended to reduce the sexual risk of HIV or STI transmission

Controlled trial (randomized or nonrandomized; single-group designs were excluded)

Reporting of at least one postintervention HIV/STI behavior outcome (i.e., unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse, inconsistent condom se) or biologic outcome (i.e., STI, HIV)

Reporting data sufficient for effect size (ES) calculation

Focus on the risk of heterosexual transmission

Focus on African American men

The study criterion of focus on African American men had to be achieved by meeting one of the following conditions:

Sole focus on African American men

At least 50% of sample composed of African American men

Outcome data stratified for African American men

We excluded studies that were focused on men who have sex with men (MSM) (including participants self-identified as homosexual, bisexual, or transgender) or whose samples were composed of more than 50% MSM. In addition, we excluded community-level interventions that intend to reduce the HIV risk of an entire community because the focus and mechanisms (e.g., delivery through community saturation) are conceptually different than from those of individual- or group-level interventions that are intended to change individual’s behaviors.

Data Abstraction

Information from eligible interventions was independently abstracted by pairs of trained reviewers. The overall agreement among the trained reviewers is 96% with a kappa rate of 80%. Linkages among studies were identified to ensure that multiple citations describing a single intervention study were included in the coding, data abstraction, and analyses. Standardized coding forms were used to code each intervention for study information, participant characteristics, outcomes, intervention features, and methodological quality. If a particular study did not report a characteristic, we coded that article as not having that characteristic.

The primary behavioral outcome measure was operationalized as (a) unprotected vaginal/anal sex, (b) condom use, (c) or indexes of sexual risk that included (a) or (b). The primary biologic outcome measure was operationalized as any reports of STI or HIV infection obtained through medical records or self-reports. The outcomes measures were selected because of their role in HIV transmission [28, 29]. In terms of intervention components, machismo was operationalized as protecting family/significant others and gender roles. Gender roles were defined as any intervention component or issue that directly involves the concept of gender norms, gender roles, masculinity, or femininity, such as gender empowerment issues, gender dynamics involved with practicing safer sex, or reaffirming a sense of manhood in the context of HIV risk reduction.

Three culture-specific components were included: (a) use of culture-specific materials (i.e., any statement related to the inclusion of materials reflective of the African American culture); (b) racially/ethnically matched deliverer (i.e., matching the participants and deliverer by race or ethnicity); and (c) deliverer trained in principles of cultural competency, defined as training to implement intervention components that are based on the cultural constructs of the target population [30].

Two gender-specific components were included: (a) use of gender-specific materials (i.e., any statement related to gender specificity or provision of materials tailored for men); and (b) gender-matched deliverer (i.e., matching participants and deliverer by gender).

Contextual factors included socioeconomic status, incarceration history, and health care issues. Socioeconomic status was captured by the use of two indicators: (a) focus on low-income persons or (b) percentage of participants with income below the federal poverty level (e.g., <$10,000/year). Incarceration history was measured by using the proportion of the sample that reported ever being incarcerated. We constructed two health services related indicators: provision/referral of medical services and discussion of mental health topics. Provision/referral of medical services was coded “yes” for interventions offering the delivery or referral for any of the following services: (a) HIV/STI-related health care, (b) general health care (including mental health care), and (c) drug treatment. The discussion of mental health topics was coded yes if an intervention addressed depression, anger, stress, anxiety, or other mental health related topics.

Additional intervention components that are common constructs in behavior change theories (e.g., information-motivation-skills theory, social cognitive theory, reason action theory) were considered in this review including knowledge and information, attitude toward condoms, motivation, normative influence, and skills building. Four types of skills building were measured as intervention components: (a) condom-use skills, (b) negotiation skills relevant to safer sex/condom use, (c) decision-making/problem-solving skills, and (d) assertiveness (i.e., improve the ability to proactively pursue safer sex behaviors).

We coded the following variables of methodological quality: study design (i.e., randomized versus nonrandomized controlled trials), allocation method (e.g., sequence generation, concealment, blinding), unit of assignment, retention rate, and intent-to-treat analysis (i.e., efficacy analysis was conducted based on original group assignment, regardless of participants’ actual intervention exposure).

Effect Size

Effect sizes were estimated with odds ratios because the odds ratio allows the estimated ES to be expressed in terms of relative odds of each outcome. For studies reporting means and standard deviations for continuous variable outcomes, standardized mean differences were calculated and then converted into odds ratio values [31]. An odds ratio of <1 indicates a reduction in odds of HIV sexual risk behavior or STI outcomes in the intervention group relative to the comparison group.

Standard meta-analytical methods were used [32]. For each study, we first used the natural logarithm to obtain log odds ratio (lnOR) and calculated its corresponding weight (i.e., inverse variance). In estimating the overall ES, we multiplied each lnOR by its weight, summed the weighted lnOR of all studies, and then divided by the sum of the weights. The aggregated lnOR was then converted back to odds ratio by exponential function, and a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was derived. We also examined the magnitude of heterogeneity of ESs by using the Q statistic and Higgins’s I2 index [33, 34]. We based our final presentation on the random-effects model because this method can provide a more conservative estimate of variance and is more appropriate than fixed-effect models when generalizing to a population of studies beyond those reviewed [35].

Analytic Approach

We used the following rules to guide data abstraction for estimating the overall intervention effect.

To meet the independence of ES assumption, we selected the intervention group that was most theoretically potent and the comparison group that was least potent (typically a standard of care or a wait-list control). Multiple ESs were calculated from individual studies if more than one relevant outcome was provided. Aggregated analyses were conducted for HIV sexual risk behavior and STI outcomes separately. The ESs and variance were averaged within a study for the HIV sexual risk behavior analyses if both unprotected sex and condom use outcomes were reported. We calculated the ES by adjusting for baseline differences between the intervention and comparison groups in cases when adjusted data were not reported [36].

We established a hierarchical selection criterion for studies reporting multiple assessments. We used the 3-month post-intervention follow-up for HIV sexual risk behavior outcomes and the 6-month post-intervention follow-up for STI outcomes as the priority assessments

We conducted sensitivity analyses to determine whether the overall results were sensitive to the aforementioned rules for guiding ES calculation. The aggregated ES estimate was compared with the estimate obtained after we excluded an outlier study that might influence the results. Another sensitivity test compared the aggregated effect with the ES of the 7 studies that included both HIV sexual risk behaviors and STI outcomes. Lastly, we examined whether overall results were sensitive to the 2 studies [37, 38] whose samples comprised approximately 20% MSM.

Between-group analyses were conducted to determine whether methodological quality; study or sample characteristics; or intervention features were associated with ESs. We assessed the between-group differences using the mixed-effects model [39] with the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software, version 2. Variables significantly associated (P < 0.05) with intervention efficacy on the basis of the mixed-effects model were entered into a multivariate random-effects meta-regression model by using STATA version 9 with the “meta-reg” command.

Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of funnel plots [40] and Egger’s regression [41] (a linear regression test that compares the standardized ES estimates with the precision [the inverse of the standard error] of each study). To reduce the likelihood of other biases, we performed other procedures consistent with the best practices associated with methodologically sound meta-analysis [42].

Results

Study Samples, Intervention Characteristics, and Methodological Quality

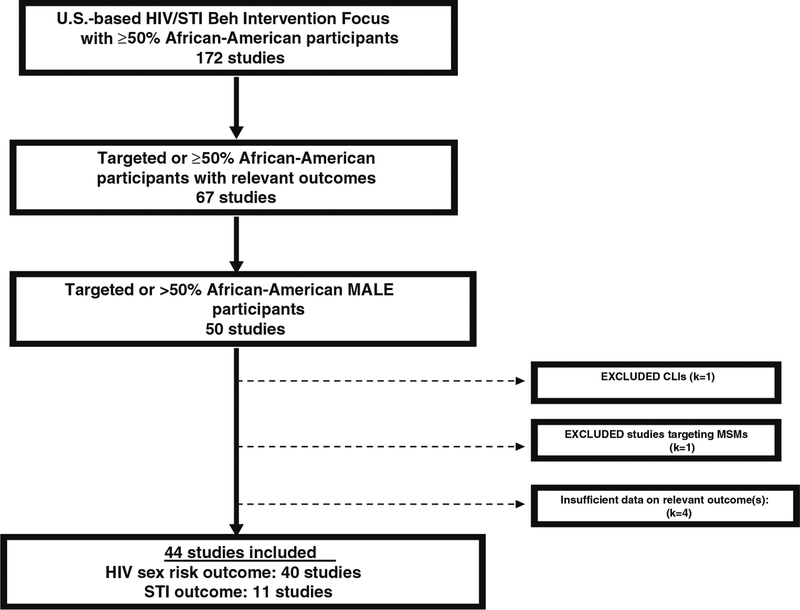

Our review included 44 studies (Fig. 1; Tables 1, 2) comprising 22,105 participants. The median age of participants was 34. Of the 44 studies, 14 stratified data by gender and race, seven focused on African American men, 14 focused on illicit drug users, and six focused on participants with a history of incarceration.

Fig. 1.

Trial selection process for meta-analytic review of HIV/STI behavioral interventions for African-American males (January 1988–May 2008)

Table 1.

Summary of stratified analyses for individual-level and group-level interventions for reducing HIV sexual risk behavior among heterosexual African American males

| k | OR | Lower 95% | Upper 95% | I2 | QB | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 40 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.89 | 42.42 | 67.74 | 0.003** |

| Sample characteristics | |||||||

| Target African Americans | |||||||

| Yes | 9 | 0.51 | 0.38 | 0.68 | 0.00 | 9.95 | 0.002** |

| No | 31 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.97 | 39.31 | ||

| Target males | |||||||

| Yes | 18 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.88 | 37.76 | 1.22 | 0.27 |

| No | 22 | 0.83 | 0.70 | 0.99 | 46.87 | ||

| Target African American males | |||||||

| Yes | 6 | 0.56 | 0.41 | 0.78 | 0.00 | 4.20 | 0.04* |

| No | 34 | 0.82 | 0.71 | 0.94 | 45.24 | ||

| Target youth | |||||||

| Yes | 7 | 0.64 | 0.49 | 0.85 | 0.00 | 2.23 | 0.14 |

| No | 33 | 0.82 | 0.71 | 0.94 | 46.28 | ||

| Target drug users | |||||||

| Yes | 14 | 0.82 | 0.63 | 1.06 | 58.54 | 0.13 | 0.71 |

| No | 26 | 0.77 | 0.67 | 0.89 | 29.37 | ||

| Target low income | |||||||

| Yes | 5 | 0.57 | 0.26 | 1.22 | 58.98 | 0.72 | 0.40 |

| No | 35 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.91 | 41.32 | ||

| Target incarceration history | |||||||

| Yes | 7 | 0.58 | 0.43 | 0.78 | 60.41 | 4.91 | 0.03* |

| No | 33 | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.97 | 39.06 | ||

| Intervention features | |||||||

| Formative research conducted | |||||||

| Yes | 14 | 0.72 | 0.60 | 0.87 | 25.02 | 1.20 | 0.27 |

| No | 26 | 0.83 | 0.70 | 0.99 | 47.11 | ||

| Culture-specific materials | |||||||

| Yes | 8 | 0.82 | 0.61 | 1.11 | 53.14 | 0.14 | 0.70 |

| No | 32 | 0.77 | 0.66 | 0.90 | 41.28 | ||

| Gender-specific materials | |||||||

| Yes | 8 | 0.73 | 0.56 | 0.95 | 26.00 | 0.32 | 0.57 |

| No | 32 | 0.79 | 0.68 | 0.92 | 44.73 | ||

| Ethnically matched deliverer | |||||||

| Yes | 7 | 0.71 | 0.59 | 0.85 | 0.00 | 0.92 | 0.34 |

| No | 33 | 0.80 | 0.69 | 0.93 | 47.66 | ||

| Gender-matched deliverer | |||||||

| Yes | 8 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.78 | 0.00 | 4.33 | 0.03* |

| No | 32 | 0.84 | 0.72 | 0.98 | 42.49 | ||

| Gender roles | |||||||

| Yes | 2 | 0.73 | 0.60 | 0.90 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.58 |

| No | 38 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.91 | 43.98 | ||

| Motivation/intention | |||||||

| Yes | 18 | 0.81 | 0.68 | 0.95 | 29.11 | 0.17 | 0.68 |

| No | 22 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.94 | 51.99 | ||

| Knowledge/information | |||||||

| Yes | 10 | 0.66 | 0.53 | 0.83 | 0.00 | 2.30 | 0.13 |

| No | 30 | 0.82 | 0.71 | 0.95 | 49.20 | ||

| Protecting significant others/family | |||||||

| Yes | 8 | 0.59 | 0.45 | 0.77 | 10.32 | 5.25 | 0.02* |

| No | 32 | 0.84 | 0.73 | 0.96 | 40.94 | ||

| Positive attitude toward condom use | |||||||

| Yes | 5 | 0.82 | 0.63 | 1.08 | 45.35 | 0.19 | 0.66 |

| No | 35 | 0.77 | 0.66 | 0.90 | 43.65 | ||

| Normative influence | |||||||

| Yes | 4 | 0.61 | 0.30 | 1.26 | 74.06 | 0.46 | 0.50 |

| No | 36 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.90 | 37.30 | ||

| Skill-correct condom use | |||||||

| Yes | 21 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.99 | 31.21 | 2.11 | 0.15 |

| No | 19 | 0.70 | 0.55 | 0.88 | 51.35 | ||

| Skill-safer sex negotiation skills | |||||||

| Yes | 18 | 0.83 | 0.71 | 0.97 | 34.91 | 0.72 | 0.40 |

| No | 22 | 0.73 | 0.60 | 0.91 | 0.04 | ||

| Skill-assertiveness skills | |||||||

| Yes | 4 | 0.73 | 0.60 | 0.89 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.58 |

| No | 36 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.91 | 46.07 | ||

| Skill-decision-making/problem-solving skills | |||||||

| Yes | 17 | 0.76 | 0.64 | 0.90 | 28.86 | 0.23 | 0.63 |

| No | 23 | 0.80 | 0.66 | 0.98 | 48.81 | ||

| Provision/referral of med serv.-HIV/STI care | |||||||

| Yes | 1 | 0.57 | 0.18 | 1.80 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.59 |

| No | 39 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.90 | 43.57 | ||

| Provision/referral of med serv.-general health | |||||||

| Yes | 4 | 0.44 | 0.28 | 0.70 | 15.70 | 6.69 | 0.01* |

| No | 36 | 0.83 | 0.73 | 0.94 | 36.75 | ||

| Provision/referral of med serv-drug treatment | |||||||

| Yes | 4 | 0.42 | 0.28 | 0.62 | 11.59 | 10.91 | 0.0009** |

| No | 36 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.95 | 31.49 | ||

| Provision/referral of med serv (HIV/STI txt, general health, drug txt) | |||||||

| Yes | 5 | 0.44 | 0.31 | 0.62 | 0.00 | 12.25 | 0.0004** |

| No | 35 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.96 | 32.81 | ||

| Mental health issues (stress, anxiety, anger, depression) | |||||||

| Yes | 7 | 0.92 | 0.75 | 1.14 | 2.15 | 2.42 | 0.12 |

| No | 33 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.88 | 46.70 | ||

| No. of intervention sessions | |||||||

| 1 | 11 | 0.77 | 0.57 | 1.04 | 57.41 | 1.73 | 0.63 |

| 2–5 | 11 | 0.94 | 0.73 | 1.22 | 59.53 | ||

| ≥6 | 14 | 0.76 | 0.61 | 0.95 | 30.14 | ||

| Nr | 4 | 0.81 | 0.54 | 1.21 | 33.88 | ||

| Duration (min) | |||||||

| ≤60 | 5 | 0.84 | 0.60 | 1.18 | 48.98 | 0.10 | 0.99 |

| 61–360 | 15 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 1.00 | 47.39 | ||

| ≥361 | 13 | 0.84 | 0.65 | 1.09 | 48.01 | ||

| Nr | 7 | 0.79 | 0.47 | 1.32 | 68.53 | ||

| Study design | |||||||

| Randomization | |||||||

| Yes | 34 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.92 | 44.22 | 0.43 | 0.51 |

| No | 6 | 0.68 | 0.42 | 1.09 | 30.07 | ||

| Retention (%) | |||||||

| ≥70 | 22 | 0.77 | 0.64 | 0.93 | 48.08 | 0.15 | 0.92 |

| <70 | 4 | 0.75 | 0.48 | 1.17 | 32.89 | ||

| Nr | 14 | 0.81 | 0.64 | 1.02 | 42.44 | ||

| Power reported | |||||||

| Yes | 8 | 0.81 | 0.70 | 0.93 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.59 |

| No | 32 | 0.76 | 0.64 | 0.90 | 49.18 | ||

| Intent to treat analysis | |||||||

| Yes | 40 | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.89 | 42.42 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| No | - | - | - | - | |||

| Longest follow-up times (months) | |||||||

| ≤2 | 4 | 0.41 | 0.27 | 0.63 | 9.29 | 0.002** | |

| >2 | 36 | 0.83 | 0.73 | 0.94 | |||

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01

Table 2.

Summary of HIV behavioral interventions for heterosexual African American men included for meta-analysis

| Author Date Intervention | Recruitment/Intervention Setting/Sample Description | Study Groups, Assignment Method, Unit of delivery | Intervention Components/Cultural & Gender Relevancy (Materials, Facilitator/Participant Matching) | Assessments Period (s) & Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andersen et al. 1996 [47] |

Recruitment Public area/community Intervention Project offices Sample N = 539, 67% AA male |

1 comparison group (standard care), 1 intervention group (Personalized Nursing LIGHT Project) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group (via zip codes) |

Comparison group: Standard of care Intervention group components: HIV knowledge, social support, self-esteem, HIV/STI related care, personalized risk reduction plan, cleaning needles Cultural & gender relevancy: None reported |

Assessment Baseline and 6-month follow-up Findings Reduced UPS |

| Berkman et al, 2006 [48] |

Recruitment Community-Based Establishment Intervention Community Sample N = 92, 65% AA male |

1 comparison group (HIV education group), 1 intervention group (SexG- Brief Group) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: HIV education & condom use skills Intervention group components: HIV/STD knowledge/information, motivation/intention, condom use skills, decision-making & problem solving, safer sex negotiation skills Cultural & gender relevancy: None reported |

Assessments Baseline and 6-month follow-up Findings Reduced UPS |

| Berkman et al., 2007 [49] |

Recruitment Psychiatric Clinic Intervention Psychiatric Clinic Sample N = 149, 54% AA male |

1 comparison group (attention control), 1 intervention group (Enhanced SexG + booster Group) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Individual |

Comparison group: Money management, social skills Intervention group components: HIV&STD knowledge/information, motivation/intention, normative influence, condom use skills, decision-making/problem solving skills, social support, evaluation of personal goals Cultural & gender relevancy Gender matched facilitators |

Assessments Baseline and 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month follow-ups (plus boosters.) Findings Reduced UPS Increased condom use |

| Branson et al., 1998 [50] |

Recruitment STD Clinic Intervention STD Clinic Sample N = 964, 50% AA male |

1 comparison group (standard care), 1 intervention group (multisession group counseling) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: HIV counseling and testing Intervention group components: HIV knowledge/information, motivation to protect oneself and others, empowerment, personal responsibility, self-esteem, decision-making skills, condom use skills, needle-cleaning skills Cultural & gender relevancy: None reported |

Assessments Baseline and 12-month follow-up Findings Condom use similar in both intervention and control groups Reduced new STIs lowered similarly in both interv and comparison group |

| Cohen et al., 1992 [51] |

Recruitment STD clinic Intervention STD Clinic Sample N = 426, 65% AA male |

1 comparison group (standard care), 1 intervention group (group counseling) Assignment: Non-random (time of day) Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: Routine care Intervention group components: HIV knowledge/information, safer-sex negotiation skills, condom-use skills Cultural & gender relevancy: Ethnic and gender matching of facilitator (females only) |

Assessment Baseline and 7–9 month follow-up Findings Lower rate of new STIs No differences were found among women. |

| Cohen et al., 1992 [52] |

Recruitment STD clinic Intervention STD Clinic Sample (stratified data) N = 196, 100% AA male |

1 comparison group (wait-list), 1 intervention group (Condom skills program for men) Assignment: Non-random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: Wait-listed Intervention group components: HIV knowledge/information, condom-use skills Cultural & gender relevancy: Ethnic and gender matching of facilitator (females only) |

Assessment Baseline and follow-up at 7–9 months Findings Lower rate of new STIs |

| Cottler et al., 1995 [53] |

Recruitment Public area/community Intervention Storefront Health Centers Sample (stratified data) N = 341, 100% AA male |

1 comparison group (HIV/AIDS materials, HIV C&T), 1 intervention group (Peer-delivered intervention) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Individual |

Comparison Group HIV/AIDS materials, HIV C&T Intervention components HIV knowledge, stress management, drug awareness (delivered via peer counseling) Cultural & gender relevancy None reported |

Assessment Baseline and 2-month follow-up Findings Increased condom use past 30 days |

| Crosby et al., 2009 [54] |

Recruitment STD Clinic Intervention STD Clinic Sample N = 266, 100% AA male |

1 comparison group: (standard care), 1 intervention group (Lay Health Advisor) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Individual |

Comparison group: Nurse-delivered messages regarding condom use knowledge, access to condoms Intervention group components: Addresses knowledge/information; motivation/intention; self-efficacy for condom use, correct condom use skills, lubrication use, access to condoms and lubrication Cultural & gender relevancy: Ethnic-matched facilitator, culturally-competent facilitator, gender-matched facilitator |

Assessments Baseline and 3-month follow-up Findings Lower rate of new STIs Increased condom use (at last sex) No significant differences in UPS during last 3 months |

| Delamater et al., 2000 [55] |

Recruitment STD clinic Intervention STD Clinic Sample N = 312, 100% AA male |

1 comparison group (standard care), 1 intervention group (video intervention) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Individual |

Comparison group: Education program Intervention group components: HIV knowledge/intention, motivation/intention, protecting community, personal risk/vulnerability, condom-use skills Cultural & gender relevancy: Ethnic-matched facilitator |

Assessments Baseline and 6-month follow-up Findings Increased condom use past 30 days |

| Dilorio et al., 2006 [56] |

Recruitment Community based establishment Intervention Community Sample N = 93, 58% AA male |

1 comparison group (HIV information and discussion), 1 intervention group (“Keepin’ It Real”) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: HIV knowledge and discussion Intervention group components: HIV knowledge, attitude towards sexual values and behavior, self-efficacy, correct condom use, assertiveness skills, decision-making/problem-solving skills, parent-child; communication skills, social support, personalized risk reduction plan Culture & gender relevancy: None reported |

Assessments Baseline and 6-month follow-up (after booster) Findings Increased condom during last sex (past 30 days) |

| Diliorio et al., 2007 [57] |

Recruitment Community-based establishment Intervention Not reported Sample N = 273, 96% AA male |

1 comparison group (attention control), 1 intervention group (“Real Men”) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: Nutrition and exercise Intervention group components: HIV knowledge, motivation/intention, attitude toward parent-child communication about HIV, listening and communication self-efficacy, social support, discuss emotional issues associated with adolescent development, developing personal goals, discuss peer pressure, parental monitoring Culture & gender relevancy: Gender appropriate materials |

Assessments Baseline and 3-, 6-, 12-month follow-up Findings Higher condom use at first sex Reduced UPS |

| El-Bassel et al., 2003 [58] |

Recruitment Clinic (hospital-based) Intervention Clinic (hospital-based) Sample N = 434 (217 couples), 55% AA, 50% male |

1 comparison group: (Education), 2 intervention groups: (Couples, Women only) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: HIV/STD education (video) Intervention group components (“Project Connects”): Communication skills, safer-sex negotiation skills, problem-solving skills Cultural & gender relevancy: Gender matched facilitators |

Assessments Baseline and 3-month follow-up Findings Increased protected sex acts Reduced UPS No differences found between two intervention groups No significant difference in STD symptoms |

| Grinstead et al., 2001 [59] |

Recruitment Correctional Intervention Correctional Sample N = 414, 51% AA male |

1 comparison group (standard care), 1 intervention group (Pre-release HIV Prevention Intervention) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Individual |

Comparison group: Access to HIV educational materials, informal access to peer educators Intervention group components: Addresses personal risk, personalized risk reduction plan, and HIV knowledge, HIV testing referrals, needle exchange Cultural & gender relevancy: Gender matched facilitator (male) |

Assessments Baseline and 2–4 week follow-up Findings Increased condom use during first sex |

| Grinstead et al., 1999 [37] |

Recruitment Correctional Intervention Correctional Sample N = 185, 50% AA male |

1 comparison group (Standard care), 1 intervention group (peer-led intervention) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Individual |

Comparison group: Access to HIV educational materials, informed access to peer educators & consultation with staff Intervention group components: HIV knowledge/information, HIV testing referrals, needle exchange, drug treatment, personal risk/vulnerability, personalized risk reduction planning Cultural & gender relevancy: Gender-matched deliverer |

Assessments Baseline and 2–4 weeks follow-up (post-release) Findings Increased condom use during first sex |

| Jemmott et al., 1992 [60] |

Recruitment Community-based establishment, educational, health care clinic Intervention Educational setting (local school on Saturdays) Sample N = 57, 100% AA male |

1 comparison group (non-HIV intervention), 1 intervention group (AIDS Risk Reduction Intervention) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: Career planning, analysis, and opportunities Intervention group components: HIV knowledge/information, motivation/intention, attitude toward sexual risk behavior and HIV/AIDS, self-esteem, condom use and abstinence self-efficacy, condom use skills, safer sex negotiation, impulse control, and condom availability skills |

Assessment Baseline and 3-month follow-up Findings Reduced UPS Increased condom use |

| Kalichman et al., 1999 [38] |

Recruitment STD Clinic Intervention STD Clinic Sample N = 117, 100% AA male |

1 comparison group (standard care), 1 intervention group (“Project Nia”) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: HIV prevention information, HIV Counseling and Testing, condom discussion Intervention group components Personal risk reduction plan, HIV knowledge/information, motivation to protect oneself and others, self-esteem, condom use skills, assertiveness skills, problem-solving skills, safer sex negotiation skills Cultural & gender relevancy: Culturally and gender specific materials. Gender-matched facilitators |

Assessment Baseline and 3-, 6-month follow-up Findings Reduced UPS Increased condom use |

| Kalichman et al., 1999 [61] |

Recruitment STD Clinic Intervention Community Sample N = 67, 100% AA male |

1 comparison group (Standard care), 1 intervention group (Polyurethane condom use skills) Assignment: Non-Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: Access to HIV educational video and group discussion Intervention group components: HIV knowledge/information, motivation/intention, condom use skills, decision making/problem solving Cultural & gender relevancy: Ethnic and Gender-matched facilitators. |

Assessments Baseline and 3-month follow-up Findings Increased condom use |

| Kalichman et al., 2005 [62] |

Recruitment STD Clinic Intervention STD Clinic Sample N = 612, Approx. 59% AA male |

1 comparison group, 3 intervention groups: (a-Motivational enhancement, b-Behavioral self-management and sexual communication, c-Full 1MB model) Unit of delivery: Group Unit of delivery: Individual |

Comparison group: HIV education about transmission, risk factors, and disease processes) Intervention groups components (four groups) Motivational enhancement: Emphasizes personal behavioral change based on personal responsibility Behavioral self-management and sexual communication: Emphasize strategies to reduce high risk behavior and communicating safe sex practices with partner Full 1MB model: Includes all components listed above. Video: used as part of intervention delivery Cultural & gender relevancy: Culturally and gender specific materials. Gender-matched facilitators |

Assessments Baseline and 3-, 6-, 9-month follow-up Findings Lower new STIs Reduced UPS |

| Kamb et al., 1998 [63] |

Recruitment STD Clinics Intervention STD Clinic Sample N = 5758, 59% AA, 57% male, Assignment: Block randomization (computer-generated) |

1 comparison group (Routine HIV/STD information), 2 intervention groups: (Enhanced counseling, Brief counseling) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison groups: Typical STD clinic didactic messages promoting consistent condom use with all partners Intervention group components Same as above and adding… Enhanced counseling: Information to encourage changes in self-efficacy, attitude, perceived norms about condom use. Goals for reducing risk were developed for each participant Intervention based on theory of reason action and social cognitive theory Brief counseling: Information to assess actual and self-perceived HIV/STD risk and develop risk reduction plan (modeled after CDC plan) Cultural & gender relevancy: None reported |

Assessments Baseline and 3, 6, 9, 12-month follow-up Findings Increased condom use. Shown between comparison and intervention groups at 3-month, less pronounced at 6-month; no differences at 9, 12-month. Decreased reporting of new STIs between comparison and intervention groups-no differences between two intervention groups |

| Kotranski et al., 1998 [64] |

Recruitment Public area/community Intervention Field Office Sample N = 595, 48.6% AA men (stratified) |

1 comparison group (HIV risk reduction education, HIV C&T, drug treatment, needle cleaning), 1 intervention group (enhanced HIV counseling intervention) |

Comparison group: HIV risk reduction education, HIV C&T, drug treatment referrals, needle cleaning, medical and social support Intervention group components: Condom use skills, personal risk vulnerability, all comparison group components (HIV risk reduction education, HIV C&T, drug treatment referrals, needle cleaning, medical and social support) Cultural & gender relevancy: None reported |

Assessments Baseline and 6-month follow-up Findings Reduced UPS (last 30 days) |

| Latkin et al., 2003 [65] |

Recruitment Public area/community Intervention Health clinic Sample N = 250, 55% AA male |

1 comparison group (Attention Control), 1 intervention group (Network-Oriented Peer Outreach) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: HIV knowledge, addiction and family dynamics Intervention group components HIV knowledge, normative influence, safer sex negotiation, leadership and communication skills, safer sex exercise, street outreach Cultural and gender relevancy: None reported |

Assessments Baseline and 6-month follow-up Findings Increased change in condom use among casual partners |

| Lurigio et al., 1992 [66] |

Recruitment Adult Probation Depart. Intervention Adult Probation Dept. Sample N = 99, Approx. 77% AA male |

1 comparison group Education: (Heart Disease), 1 intervention group: (HIV education) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Individual and Group |

Comparison groups: Heart disease prevention strategies Intervention group components HIV/STD knowledge and information, motivation and intention, condom use skills, skills using lubricants, cleaning needles; using dental dams Cultural & gender relevancy: None reported |

Assessments Baseline and (approx) 1 month follow-up Findings Condom use |

| McMahon et al., 2001[67] |

Recruitment Drug Treatment Program (VA Hospital) Intervention Drug Treatment Program (VA Hospital) Sample N = 149, 59% AA male |

1 comparison group: (Standard care), 1 intervention group (Cognitive-behavioral HIV risk reduction group) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: Basic information about HIV, HIV risk behaviors, and risk reduction practices Intervention group components HIV knowledge/information, condom use skills, safer sex negotiation skills, other sex-related communication skills, needle use skills, personal risk/vulnerability assessment Cultural & gender relevancy: Cultural and gender specific materials |

Assessments Baseline and 12-month follow-up Findings Increases in # of unprotected sex acts |

| Magura et al, 1994 [68] |

Recruitment Correctional Intervention Correctional Sample N = 157, 65% AA men |

1 comparison group (wait-list control), 1 intervention group (AIDS Education Program) Assignment: Convenience Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: Wait-list Intervention group components HIV knowledge, attitude towards high-risk behavior, decision-making/problem-solving skills, protecting oneself, protecting family/significant others, general health care, drug treatment, personal risk/vulnerability Cultural & gender relevancy: Gender-matched participants, gender appropriate materials |

Assessments Baseline and 5-month follow-up Findings Increased condom use during vaginal sex Increased condom use during oral & anal sex |

| Maher et al.,2003[69] |

Recruitment STD Clinic Intervention Community location convenient to participant Sample N = 581, 100% AA male |

1 comparison group: (Routine counseling), 1 intervention group (Intensive counseling) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Individual |

Comparison group: Standard of care (STD clinic) Intervention group components Personal risk assessment, HIV knowledge, motivation to protect oneself and others, attitude and beliefs about STDs, changing social norms, condom use skills, safer sex negotiation skills, alternatives to intercourse, future education and job plans Cultural & gender relevancy Intervention materials culturally specific. Counselors familiar and sensitive to cultural norms, values, and traditions |

Assessments Baseline and 12 months Findings STD incidence lower for interv group compared to comparison group |

| Malow et al., 1994 [70] |

Recruitment VA hospital drug txt Intervention VA hospital drug txt Sample N = 152, 100% AA men |

1 comparison group (Videotape and printed material), 1 intervention group (Psychoeducational program) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: HIV risk reduction education via videotape and printed materials Intervention group components: HIV knowledge, motivation/intention, condom use attitudes, self-efficacy, correct condom use, safer sex negotiation, needle cleaning, personal risk/vulnerability Cultural & gender relevancy Ethnic and Gender matched deliverers Culturally and gender appropriate materials used |

Assessments Baseline and 3-month follow-up Findings Greater UPS reduction among interv group compared to control group |

| Martin et al., 2003 [71] |

Recruitment Correctional Intervention Not reported Sample (of men reporting any UPS) N = 294 58% AA male |

1 comparison group (enhanced NIDA intervention), 1 intervention group (Focused Intervention) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: Pre-test counseling for HIV & Hepatitis, HIV and Hepatitis information, condom use, needle cleaning, communication skills, HIV test Intervention group components HIV knowledge, correct condom use, decision making/problem-solving, needle cleaning skills, though mapping, drug treatment benefits, protecting oneself, protecting family/significant others, personal risk/vulnerability, personalized risk reduction plan Cultural & gender relevancy: None reported |

Assessments Baseline and 6 month follow-up Findings Reduced UPS |

| McCoy et al, 1990 [72] |

Recruitment Public area/community Intervention Storefront Assessment Center Sample N = 88, 52% AA men (stratified) |

1 comparison group (HIV risk reduction education, referrals), 1 intervention group (NADR-Belle Glade) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: HIV risk reduction education, referrals to services) Intervention group components Condom use skills, needle cleaning practices, HIV C&T, bleach kits, condoms, encouragement of safer sex negotiation, HIV knowledge/information, motivation/intentions, attitudes toward risk reduction, personal responsibility, personal risk/vulnerability, personalized risk reduction plan, self-esteem, HIV/STI related care, general health care (including mental health), drug txt. Cultural & gender relevancy: Culturally appropriate materials used |

Assessment Baseline and 6-month follow-up Findings Consistent condom use increased |

| Metcalf et al., 2005 [73] |

Recruitment STD Clinic Intervention STD Clinics Sample (Stratified data) N = 906, 100% AA men |

1 comparison group (counseling), 1 intervention (counseling + booster) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Individual |

Comparison group: HIV knowledge, motivation/intention, attitude toward condom use, condom use self-efficacy, social support, personal risk/vulnerability, personalized risk reduction planning, goal setting Intervention group components HIV knowledge, motivation/intention, attitude toward condom use, condom use self-efficacy, social support, personal risk/vulnerability, personalized risk reduction planning, goal setting, PLUS booster package Cultural/Relevancy: None reported |

Assessment Baseline and 3 month follow-up Findings Greater STD rate reduction among interv group compared to control Greater reduction in sex risk behaviors for booster group compared to non-booster group |

| NIMH et al, 1998 [74] |

Recruitment STD Clinic Intervention STD Clinic Sample N = 3706, 74% AA male |

1 comparison group (Education), 1 intervention group (Small group sessions focusing on risk reduction skills-building) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: Education session Intervention group components Condom use skills, decision-making/problem-solving skills HIV knowledge, safer sex negotiation. Cultural & gender relevancy: None reported |

Assessments Baseline and 6, 12-month follow-ups Findings Reduced UPS, increased condom use, reduced STI incidence |

| O’Donnell et al., 1998 [75] |

Recruitment STD Clinic Intervention STD Clinic Sample N = 2004, 62% AA male |

1 comparison group (Standard care), 2 intervention groups: (Video viewing only, Video viewing followed by interactive group discussion) Assignment: Proportionate random sampling plan (reflective of clinic patient population) Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: Standard of care Intervention groups components (2 groups) Video viewing only: Provided education about STDs and prevention, positive attitudes about condom use, and modeled strategies for condom use in various sexual relationships. Video viewing/discussion: Addresses HIV knowledge, motivation to protect oneself and others, and attitudes toward condom use, safer sex negotiation skills, overcoming barriers to condom use Cultural & gender relevancy: AA and gender specific materials (videos). Gender matched facilitator (men). |

Assessments Baseline and follow-up (avg. 17 months) via clinical records Findings New STIs lower among interv (video/discussion) group compared to comparison group. |

| O’Leary et al., 1998 [76] |

Recruitment STD Clinic Intervention STD Clinic Sample N = 659, Approx. 54% AA male |

1 comparison group: (Standard Care), 1 intervention group (Intensive HIV Risk Reduction) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: Standard care Intervention group components Addresses personal risk, HIV/STD knowledge, and condom use self-efficacy, correct condom use skills, negotiating safef sex skills Cultural & gender relevancy: None reported |

Assessments Baseline and 3 months Findings # of sex ptrs lower among interv group. # of unprotected sex acts lower overall between BL and 3 M assessments in both groups. |

| Otto-Salaj et al., 2001 [77] |

Recruitment Community Mental Health Clinic Intervention Community Mental Health Clinic Sample N = 189, >50% AA male |

1 comparison group (Health Promotion), 1 intervention group (cognitive-behavioral intervention) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: Stress, nutritional health, cancer, heart disease, personal relationships Intervention group components HIV knowledge, self-efficacy for risk reduction behavior, assertiveness skills, decision making/problem-solving skills, goal setting, safer sex negotiation skills, sexual communication skills, protecting oneself, personal responsibility, personal risk/vulnerability, personalized risk reduction plan, enhancing risk reduction skills for purposes of empowerment |

Assessment Baseline and 3, 6, 12 months follow-ups Findings Reduced UPS, increased protected sex |

| Saint Lawrence et at., 1995 [78] |

Recruitment Health care center Intervention Not reported Sample N = 3706, 28% AA. male (stratified data) |

1 comparison group (education only), 1 intervention (educational and behavioral skills) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: Education session Intervention group components Condom use skills, assertiveness skills, decision-making/problem-solving skills, safer sex negotiation skills, social support, protecting oneself, protecting family/significant others, personal risk/vulnerability, personalized risk reduction planning, risk reduction self-efficacy, HIV knowledge/information, attitudes toward condom use, normative influence, safer sex negotiation. Cultural & gender relevancy: Gender-matched deliverers, Culturally appropriate materials |

Assessments Baseline and 3, 6, 12-month follow-ups Findings Reduced UPS among AA males |

| Saint Lawrence et al., 1999 [79] |

Recruitment Correctional Intervention Correctional Sample N = 361, 70% AA male |

1 comparison group (Anger Management), 1 intervention group (Sexual Risk Reduction Skills Training) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison: Anger management, providing positive/negative feedback, accepting criticism, resisting peer pressure, conflict resolution Intervention HIV knowledge, correct condom use, safer sex negotiation, refusing unwanted sexual initiations, self-reinforcement of adaptive behavior Cultural & gender relevancy: Gender-matched deliverers |

Assessments Baseline and 6-month follow-up Findings Reduce UPS, increased proportion of condom-protected sex, increased condom-protected vaginal sex |

| Siegal et al., 1995 [80] |

Recruitment Public area/community Open-air drug markets Intervention Not reported Sample N = 434, >50% AA male |

1 comparison group (HIV education, 1 intervention group (NADR-Dayton & Columbus) Assignment: Non-RCT (systematic assignment) Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: HIV education via literature and demonstration Intervention group components Condom use skills, decision making/problem-solving, safer sex negotiation, bleach use, HIV/STI related care, General health care, drug txt, personal responsibility, personal risk/vulnerability, HIV knowledge/information Cultural & gender relevancy: None reported |

Assessments Baseline and 6-month follow-up Findings Reduced score on sex risk index (# sex ptrs, type of sex, frequency of CU w/sex) |

| Stephens et al., 1993 [81] |

Recruitment Health care clinics Community-based establishments Correctional settings Intervention Community (Assessment Center) Sample N = 512, >50% AA male |

1 comparison group: HIV risk reduction education, referrals to services), 1 intervention group: (NADR Study-Miami) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Individual and Group |

Comparison group: HIV risk reduction education, referrals to services) Intervention group components Condom use skills, needle cleaning practices, bleach kits, condoms, HIV knowledge/information, motivation/intentions, attitudes toward risk reduction, personal responsibility, personal risk/vulnerability, personalized risk reduction plan, self-esteem, safer sex negotiation, problem solving, HIV/STI related care, general health care (including mental health), drug txt. Cultural & gender relevancy: Culturally appropriate materials used |

Assessments Baseline and 6-month follow-up Findings Reduced score on sex risk index (# sex ptrs, type of sex, frequency of CU w/sex) |

| Stephens et al., 1993 [81] |

Recruitment Public area/community Intervention Community Sample N = 508, >50% AA male |

1 comparison group (HIV risk reduction education, referrals to services), 1 intervention group: (NADR Study-Cleveland) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Individual and Group |

Comparison group: HIV/AIDS education and referrals to needed community services (e.g. HIV C&T) Intervention group components Condom use skills, decision making/problem solving, safer sex negotiation, bleach use, risk avoidance, condom distribution, bleach kits, HIV/STI related care, general health care (including mental health), drug txt. Cultural & gender relevancy: None reported |

Assessments Baseline and 6-month follow-up Findings Reduced score on sex risk index (# sex ptrs, type of sex, frequency of CU w/sex) |

| Stephens et al., 1993 [81] |

Recruitment Public area/community Intervention None reported Sample N = 90; >50% AA male |

1 comparison group (AIDS education and referrals) and 1 intervention group (NADR-Jersey) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: None reported |

Comparison group: AIDS education and referrals Intervention group components Information not available Cultural & gender relevancy: None reported |

Assessments Baseline and 6-month follow-up Findings Reduced score on sex risk index (# sex ptrs, type of sex) |

| Stephens et al., 1993 [81] |

Recruitment Public area/community Intervention None reported Sample N = 323; >50% AA male |

1 comparison group (AIDS education and referrals) and 1 intervention group (NADR-Newark) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: None reported |

Comparison group: AIDS education and referrals Intervention group components HIV knowledge/information Cultural & gender relevancy: None reported |

Assessments Baseline and 6-month follow-up Findings Reduced score on sex risk index (# sex ptrs, type of sex) |

| Stephens et al., 1993 [81] |

Recruitment Public area/community Community-based establishments Correctional settings Residential Intervention None reported Sample N = 415, >50% AA male |

1 comparison group (AIDS information and demonstration), 1 intervention (NADR-New Orleans) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Individual and Group |

Comparison groups: AIDS information and demonstration Intervention group components Condom use skills, decision making/problem solving, safer sex negotiation, risk avoidance & needle cleaning, bleach kits and condoms, personal risk/vulnerability, HIV knowledge/information, HIV/STI related care, general health care (including mental health), drug txt. Cultural & gender relevancy: None reported |

Assessments Baseline and 6-month follow-up Findings Reduced score on sex risk index (# sex ptrs, type of sex, frequency of CU w/sex) |

| Susser et al., 1998 [82] |

Recruitment Community Based Establishment Intervention Community Sample N = 59, 58% AA male |

1 comparison group (Education), 1 intervention group (Sex, Games, and Videotape) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Group |

Comparison group: HIV/STD knowledge, condom use instructions Intervention group components HIV knowledge/information, condom use skills, safer sex negotiation skills, sex risk reduction self-efficacy, personal risk/vulnerability assessment Cultural & gender relevancy: Ethnic-matched facilitators |

Assessments Baseline, 6-month, & 12-month follow-ups Findings Unprotected sex episodes lower in intervention group compared to comparison group |

| Wenger et al., 1991 [83] |

Recruitment STD clinic Intervention STD Clinic Sample N = 256, Approx. 55% AA male |

1 comparison group: (AIDS education alone), 1 intervention group: (AIDS education and HIV test with results) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Individual |

Comparison group: AIDS Education Intervention group components HIV knowledge and personal risk, condom use skills, and HIV C&T Cultural & Gender Relevancy: None reported |

Assessments Baseline and 2-month follow-up (via mail questionnaire) Findings Condom use with last partner increased for intervention group compared to comparison group. |

| Wolitski et al., 2006 [84] |

Recruitment Correctional Intervention Correctional Sample N = 522, 52% AA male |

1 comparison group: (Standard Education), 1 intervention group: (Enhanced Intervention) Assignment: Random Unit of delivery: Individual |

Comparison group: HIV knowledge, personalized risk reduction plans, referrals, skills training Intervention group components: Personalized risk reduction plan, HIV knowledge, motivation to protect oneself and others, prevention case mgmt., harm reduction, problem solving skills Cultural & gender relevancy: None reported |

Assessments Baseline and 24-week follow-up Findings UPS lower among interv. group compared with comparison |

Interventions typically were delivered in small groups (k = 30, 68%), consisting of a maximum of 3 sessions (k = 23, 52%) and lasting a maximum of 6 h (k = 23, 52%). The predominant intervention settings were STI clinics (k = 12, 27%), followed by community-based organizations (k = 7, 16%), correctional facilities (k = 6, 14%), and other health care settings (k = 6, 14%). The interventions were delivered by trained facilitators (k = 22, 50%) or educators (k = 18, 41%).

Of the 44 studies, 34 used one or more behavioral theories. Nearly three-fourths reported the inclusion of at least one cultural or gender-relevant feature: 10 used culturally specific materials, and nine used racially matched deliverers; 11 used gender-matched deliverers, and nine used gender-specific materials. Nearly two-thirds of interventions included skills building in HIV/STI risk reduction: condom use (k = 24); negotiation of safer sex/condoms (k = 21); and decision-making/problem-solving (k = 17). Five interventions (11%) reported one or more types of provision/referral of medical services, which included drug treatment (k = 4), other general health care (including mental health care) (k = 4), or HIV/STI-related care (k = 1).

Overall Effect Sizes: HIV-Risk Sex Behavior and STI Outcomes

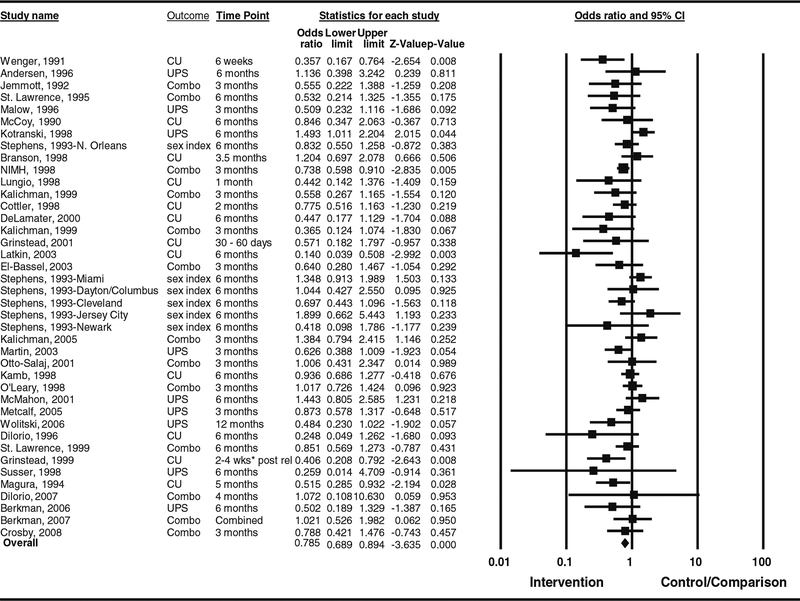

The aggregated ES of the 40 studies that reported any HIV sexual risk behavior was statistically significant (OR = 0.79; 95% CI = 0.69, 0.89, N = 20,934, Table 1). Q test and I2 indicated heterogeneity among studies reporting HIV sexual risk behavior outcomes (Q39 = 67.74, P < 0.003; I2 = 42.42) and further examination of heterogeneity is described under between-group analyses below.

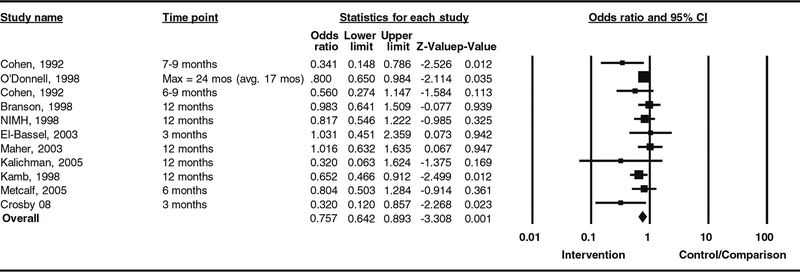

For the STI outcomes, the aggregated ES of 11 studies was also statistically significant (OR = 0.74; 95% CI = 0.63, 0.87, N = 14,592; Table 1). Q test and I2 did not indicate heterogeneity among studies reporting STI outcomes (Q10 = 12.60, P = 0.25, I2 = 20.62). Because of the lack of heterogeneity and a small number of studies, we did not conduct between- group analyses for the meta-regression analysis for STI outcomes (Figs. 2, 3).

Fig. 2.

Study specific and overall ES estimates (40 trials) of HIV sexual risk behavior outcomes for behavioral interventions targeting heterosexual African American men. Note. “Combo”-combined effect size of condom use (CU), unprotected sex (UPS), and author-defined HIV-risk behavior index (sex index) within a study. The boxes represent study weights (inverse variance of random-effects model)

Fig. 3.

Study specific and overall ES estimates (11 trials) of STIs outcomes for behavioral interventions targeting heterosexual African American men. Note. The boxes represent study weights (inverse variance of random-effects model)

Sensitivity Analyses

No single study influenced the overall ES for each outcome. We compared the ES estimates of seven studies that reported both HIV sexual risk behavior and STI outcomes with the overall HIV sexual risk behavior ES and STI effect size estimates. The results were comparable (HIV sexual risk behavior outcomes: OR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.74, 1.03, P = 0.11, k = 7; STI outcomes: OR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.61, 0.94, P = 0.01, k = 7). For HIV sexual risk behaviors, the effect size was comparable to the overall ES even when we excluded 2 studies with samples of ≥ 20% MSM (OR = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.71, 0.92, k = 38) (neither study reported STI outcomes). The ES for HIV sexual risk behaviors changed only slightly when we excluded studies that targeted drug users (OR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.67, 0.90, k = 26).

Publication Bias

On the basis of the linear regression test [41], we found evidence of publication bias for the 40 studies that reported any HIV sexual risk behavior (t = 2.45, P = 0.019). The funnel plot was asymmetrical, suggesting fewer studies with negative intervention effects and large variance (figure not shown). We did not find evidence of publication bias for the 11 studies that provided STI outcomes (t = 1.616, P = 0.141).

Between-Group Analyses for HIV-Risk Sex Behaviors

For HIV sexual risk behavior outcomes, efficacy was significantly greater (see Table 1) among interventions focused on African Americans, African American men, and men with incarceration history, as well as interventions that used gender-matched deliverers, addressed the protection of family and significant others, or provision/referral of medical services including general health care, drug treatment, or any provision/referral of medical services (HIV/STI, general health, drug treatment) (for all characteristics, P < 0.05). Additionally, studies with a shorter follow-up showed a larger intervention effect than studies with a longer follow-up (>2 months).

Findings of Meta-Regression Analysis of HIV-Risk Sex Behaviors

For HIV sexual risk behaviors, we conducted a multivariate random-effects meta-regression analysis to test for independent effects of the significant sample or intervention characteristics identified. The three provision/referral of medical services types (HIV/STI treatment, general health care, including mental health care, and drug treatment) were highly correlated with each other (Pearson r’s ranged from 0.72 to 0.88). To avoid multicollinearity among those variables, we used a composite measure of any provision/referral of medical services. We entered five additional predictors (based on the bivariate analyses): focused on African American men, men with incarceration history, length of follow-up period, gender-matched deliverer, and the protection of family/significant others. Provision/referral of medical services (coefficient = −0.53, SE = 0.28, z = −1.90, P = 0.07) emerged as the strongest independent predictor of intervention efficacy. We suspect that the marginal statistical significance of this variable was due in part to the moderate correlation between history of incarceration and provision/referral of medical services (r = 0.672, P < 0.001). When we removed incarceration history from the meta-regression equation, provision/referral of medical services emerged as a predictor with high statistical significance (coefficient = −0.55, SE = 0.23, z = −2.46, P = 0.02).

Discussion

This meta-analysis is the first to focus on heterosexual African American men. Similar meta-analyses [22–24], despite their focus on African Americans, did not stratify results by this high risk population. In addition, our meta-analysis directly tested the effects of interventions that addressed social and structural issues (e.g., gender roles and provision/referral of medical services) on HIV sexual risk behaviors. Like other meta-analyses, we also found that, in general, interventions can be efficacious in reducing HIV sexual risk behaviors and STI outcomes among heterosexual African American men.

Compared with a recent meta-analysis of African American women [25], the HIV interventions in our meta-analysis were slightly less efficacious in reducing HIV sexual risk behaviors among heterosexual African American men (men: OR = 0.79; 95% CI = 0.69, 0.89, N = 20,934; women: OR = 0.63; 95% CI = 0.54, 0.75; N = 11,239). The intervention effects on STI outcomes were comparable in both reviews (men: OR = 0.76; 95% CI = 0.64, 0.89, N = 14,592; women: OR = 0.81; 95% CI = 0.67, 0.98; N = 8,760). It is encouraging that interventions with heterosexual African American men can achieve reductions in HIV sexual risk behaviors and STI outcomes similar to those achieved by interventions with African American women.

As we hypothesized, skills-building for promoting safer sex negotiation was not critical in influencing African American men’s risk behaviors, which contrast the meta-analytic findings for African American women [25]. In the context of power dynamics in heterosexual relationships, the communication skill may be more important for women than men because women are often in subordinate power positions in relation to their male partners [6]. Another important theme that emerges from the findings is the association of increased efficacy with intervention features related to protecting family/significant others, suggesting that framing HIV prevention messages in the context of protecting family and significant others can motivate heterosexual African American men to reduce HIV sexual risk behaviors. In this regard, machismo may help encourage a sense of responsibility to reduce HIV risk that is aligned with their sense of manhood [5].

Poverty rates are disproportionately high among African American men and African American women [17, 43]. Although we coded the income and poverty level of the participants, none of the interventions we reviewed were specifically designed to address poverty issues. Recently, the use of financial empowerment strategies (e.g., microfinance) as an HIV prevention strategy [44] has received increased attention. However, many microfinance interventions are focused on women and emphasize gender inequality and empowerment. Given that many heterosexual African American men also struggle with low socioeconomic status, a microfinance strategy to empower these men seems worthy of consideration.

Provision/referral of medical services was the intervention component most strongly associated with efficacy in reducing HIV sexual risk behavior among heterosexual African American men. This finding is consistent with the findings of other reports demonstrating the benefit of using a comprehensive health care approach in implementing HIV behavioral prevention interventions [18, 19], especially when the disease is stigmatized or when people have limited access to care. Given that African American men have disproportionately less health care insurance [17] and are more likely to receive health care from providers with less training compared to whites [43], a more holistic health promotion approach that includes HIV prevention may be more likely to be effective in reducing HIV sexual risk behavior among these men. However, our findings revealed that most of the interventions that provide some form of health care services targeted African Americans with an incarceration history. Therefore, we caution public health researchers to conduct sufficient formative work when developing or adapting these components for interventions that target African American men with no incarceration history.

Several limitations warrant comment. First, our focus on heterosexual African American men means that the selection of studies hinged substantially on the accuracy and detail of the published reports. Many of the studies reported only sex and racial demographics; that is, they gave no information regarding sexual orientation. Others reported sexual orientation or identity but did not assess whether heterosexually identified participants engaged in any same-sex activity. Thus, our analyses may have included African American men who engaged in same-sex activity but who did not identify themselves as gay. Second, we did not conduct an extensive search in the grey literature (e.g., dissertations, conference abstracts, unpublished reports). Third, we used odds ratio as the indicator of ES. Despite the advantages of using odds ratios as a summary statistic in a meta-analysis, odds ratios cannot be used to compare populations whose risk factors differ at baseline [45, 46]. Evidence of efficacious intervention components was based on HIV risk behavior outcomes. Therefore, we cannot make generalizations that the efficacious intervention components identified in this meta-analysis also affect biological outcomes. While it is encouraging that behavioral interventions, as a whole, do reduce STIs among heterosexual African American men, more studies are needed to further examine the efficacious intervention components for impacting biological outcomes.

Another limitation is that the assessment of several variables was likely affected by reporting issues. The reported conceptual or operational definitions of cultural element indicators, in particular, were inconsistent or limited. Furthermore, there is also the possibility that some of cultural elements included in the interventions were not included in the published report. These reporting issues made it difficult to assess both the quantity and quality of the cultural elements incorporated in the interventions. Therefore, making generalizations across these studies would be extremely challenging.

Conclusion

The interventions in our meta-analysis were efficacious in reducing HIV sexual risk behaviors and STIs among heterosexual African American men; the interventions for African Americans in general and men with incarceration history were even more efficacious. The most efficacious HIV behavioral interventions incorporated other health care services rather than providing HIV/STI prevention alone. In addition, the protection of family and significant others is a component that contributes to intervention efficacy. Development of strategies targeting heterosexual African American men should include interventions that best incorporate the aforementioned components to maximize prevention efficacy and effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

We especially thank the Prevention Research Synthesis Team in the Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for their assistance in identifying relevant studies, coding, and providing valuable feedback.

Contributor Information

Kirk D. Henny, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Road NE, Mailstop E-37, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA

Nicole Crepaz, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Road NE, Mailstop E-37, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA.

Cynthia M. Lyles, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Road NE, Mailstop E-37, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA

Khiya J. Marshall, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Road NE, Mailstop E-37, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA

Latrina W. Aupont, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Road NE, Mailstop E-37, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA

Elizabeth D. Jacobs, ICF Macro, 3 Corporate Blvd. NE Ste. 370, Atlanta, GA 30329, USA,

Adrian Liau, Health Information & Translational Sciences, Indiana University School of Medicine, 410 W. 10th Street, HS 1001, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA.

Sima Rama, Manila Consulting Group, Inc., 1420 Beverly Road, Suite 220, McLean, VA 22101, USA.

Linda S. Kay, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Road NE, Mailstop E-37, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA

Leigh A. Willis, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Road NE, Mailstop E-37, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA

Mahnaz R. Charania, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Road NE, Mailstop E-37, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2009. vol. 21 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/. Published February 2011. Accessed 29 Aug 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laumann E, Ellingson S, Mahay J, Paik A, Youm Y. The sexual organization of the city. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adimora A, Schoenbach V, Floris-Moore M. Ending the epidemic of heterosexual HIV transmission among African Americans. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:468–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Estrada A Deriving culturally competent HIV prevention models Mexican American injection drug users. Paper presented at: HIV/AIDS research conference, Los Angeles, CA, April 23–24, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowleg L Love, sex, and masculinity in sociocultural context: HIV concerns and condom use among African American men in heterosexual relationships. Men Masc. 2004;7(2):166–86. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins P Black sexual politics: African Americans, gender, and the new racism. New York: Routledge; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huedo-Median TB, Boynton MH, Warren MR, et al. Efficacy of HIV prevention interventions in Latin American and Caribbean nations, 1995–2008: a meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(6): 1237–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albarracin J, Albarracin D, Durantini M. Effects of HIV-prevention interventions for samples with higher and lower percents of Latinos and Latin Americans: a meta-analysis of change in condom use and knowledge. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(4):521–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pleck J, Sonenstein F, Ku L. Masculinity ideology: its impact on adolescent males’ heterosexual relationships. J Soc Issues. 1993; 49(3):11–29.17165216 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willis L Tapping the core: behavioral characteristics of the low-income, African-American male core group. Soc Theory Health. 2007;5:245–66. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson Y, Quinn S, Eng E, Sandelowski M. The gender ratio imbalance and its relationship to risk of HIV/AIDS among African American women at historically black colleges and universities. AIDS Care. 2006;18:323–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beere CA. Gender roles: a handbook of tests and measures. vol. 36 New York: Greenwood Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Springer SA, Altice FL. Managing HIV/AIDS in correctional settings. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2005;2:165–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman S, Cooper H, Osborne A. Structural and social context of HIV risk. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(6):1002–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xanthos C, Treadwell H, Holden K. Social determinants of health among African-American men. J Mens Health. 2010;7:11–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adimora AA, Schoenbach V. Contextual factors and the black-white disparity in heterosexual HIV transmission. Epidemiology. 2002;13:707–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor B, Smith J. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2007. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sherman S, German D, Cheng Y, Marks M, Bailey-Kloche M. The evaluation of the JEWEL project: an innovative economic enhancement and HIV prevention intervention study targeting drug-using women involved in prostitution. AIDS Care. 2006; 18(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashburn K, Kerrigan D, Sweat M. Micro-credit, women’s groups, control of own money: HIV-Related negotiation among partnered Dominican women. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:396–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall H, Byers R, Ling Q, Espinoza L. Racial/ethnic and age disparities in HIV prevalence and disease progression among men who have sex with men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(6):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Talcott J, Spain P, Clark J, et al. Hidden barriers between knowledge and behavior: the North Carolina prostate cancer screening and treatment experience. Cancer. 2007;109:1599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LA, Smoak ND, et al. Behavioral interventions for African Americans to reduce sexual risk of HIV: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(4):492–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Darbes L, Crepaz N, Lyles C, Kennedy G, Rutherford G. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk behaviors and incident sexually transmitted diseases in heterosexual African Americans. AIDS. 2008;22:1177–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crepaz N, Horn A, Rama S, Griffin T, DeLuca J, Mullins M. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk sex behaviors and incident sexually transmitted disease in black and Hispanic sexually transmitted disease clinic patients in the United States: a meta-analytic review. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:319–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crepaz N, Marshall K, Aupont L, et al. The efficacy of HIV/STI behavioral intervention for African-American females in the United States: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(11): 2069–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeLuca J, Mullins M, Lyles C, Crepaz N, Kay L, Thadiparthi S. Developing a comprehensive search strategy for evidence-based systematic review. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice. 2008;3(1):3–32. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lyles C, Crepaz N, Herbst J, Kay L. Evidence-based HIV behavioral prevention from the perspective of the CDC’s HIV/AIDS prevention research synthesis team. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18:21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Basic information about HIV and AIDS. August 3, 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/basic/index.htm#spread. Accessed 27 Oct 27.

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Basic information about HIV and AIDS. August 11, 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/basic/index.htm. Accessed 10 June 2011.

- 30.Torre A, Estrada A. Mexican Americans and health. Tucson: University of Arizona Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanchez-Meca J, Marin-Martinez F, Chacon-Moscoso S. Effectsize indices for dichotomized outcomes in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods. 2003;8(4):448–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC, editors. The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;15:1539–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huedo-Medina TB, Sanchez-Meca J, Marin-Martinez F, Botella J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2.Psychol Methods. 2006;11:193–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]