Abstract

Introduction

Although pathogenesis of small vessel disease is poorly understood, increasing evidence suggests that endothelial dysfunction may have a relevant role in development and progression of small vessel disease. In this cross-sectional study, we investigated the associations between imaging signs of small vessel disease and blood biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction at two different time points in a population of ischaemic stroke patients.

Patients and methods

In stroke patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis, we analysed blood levels of von Willebrand factor, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor. Three reviewers independently assessed small vessel disease features using computed tomography. At baseline and 90 days after the index stroke, we tested the associations between single and combined small vessel disease features and levels of blood biomarkers using linear regression analysis adjusting for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, smoke.

Results

A total of 263 patients were available for the analysis. Mean age (±SD) was 69 (±13) years, 154 (59%) patients were male. We did not find any relation between small vessel disease and endothelial dysfunction at baseline. At 90 days, leukoaraiosis was independently associated with intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (β = 0.21; p = 0.016) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (β = 0.22; p = 0.009), and lacunes were associated with vascular endothelial growth factor levels (β = 0.21; p = 0.009) whereas global small vessel disease burden was associated with vascular endothelial growth factor (β = 0.26; p = 0.006).

Discussion

Leukoaraiosis and lacunes were associated with endothelial dysfunction, which could play a key role in pathogenesis of small vessel disease.

Conclusions

Small vessel disease features and total burden were associated with endothelial dysfunction 90 days after the stroke, whereas there was no relation during the acute phase. Our results suggest that endothelial dysfunction, particularly vascular endothelial growth factor, is involved in pathological process of small vessel disease.

Keywords: Small vessel disease, endothelial dysfunction, intercellular adhesion molecule, vascular cell adhesion molecule, vascular endothelial growth factor, acute stroke

Introduction

The term small vessel disease (SVD) describes a heterogeneous condition with different underlying aetiologies affecting microcirculation in the brain.1 SVD represents a frequent cause of vascular dementia, causes around one-fifth of the strokes in the world and is recognised as a disease with a high social impact.2,3 Magnetic resonance (MR) is the gold standard to investigate in vivo SVD, although considerable information can also be gathered with computed tomography (CT). CT signs of SVD are lacunar infarct, leukoaraiosis (i.e. white matter changes) and cerebral atrophy.

Pathogenesis of SVD is poorly understood; however, several studies suggested a key role of endothelial dysfunction in development and progression of SVD.4 Endothelial dysfunction has been associated with lacunar infarcts5 and with increased cerebral white matter hyperintensity.6 Although several biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction have been investigated in relation with SVD, studies reported conflicting results,7 and no marker of endothelial dysfunction has shown a predominant role.8 Moreover, the majority of the studies investigated endothelial dysfunction in patients with chronic cerebrovascular disease or in stroke-free subjects, and there are scarce data about the validity of the relationship in patients with acute stroke. Furthermore, growing evidence has shown that global evaluation of SVD may provide a useful overview of its impact on the brain,9–11 but no study so far investigated whether endothelial dysfunction is associated with SVD burden.

Analysing data from a population of acute ischaemic stroke patients treated with rt-PA, we aimed to evaluate the relationship between presence and severity of: (i) single features of SVD and (ii) global SVD burden and blood levels of markers of endothelial dysfunction at two different time points.

Methods

Patients

We retrospectively analysed the Italian registry of bioloGical MArkers in acute IschaemiC stroke (MAGIC). Briefly, MAGIC study was a multicentre prospective observational study across 14 centres in Italy. Patients with acute ischaemic stroke treated with i.v. rt-PA before 4.5 h from onset were enrolled, without age limit. Stroke severity was evaluated before rt-PA treatment using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS). Study protocol was approved in every participating centre from local ethic committee. Each patient received informed consent.

Procedures

Blood samples were obtained before rt-PA treatment and 90 days after the index stroke. For the purposes of the present study, we analysed the following markers of endothelial dysfunction: von Willebrand factor (vWF), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF). Blood separation from plasma was done within 240 min from sampling and stocked at −20°C; blood samples were analysed in a central laboratory within 30 days.

Each patient received a CT scan at baseline and after 24 h (22–36 h).

SVD assessment

CT scans from each participating centre were collected at a central core lab and three stroke neurologists (FA, BP, VP) blinded to clinical data independently rated leukoaraiosis, lacunes and cerebral atrophy following STandards for ReportIng Vascular changes on nEuroimaging criteria.12 Evaluation of SVD features was blinded to demographic and clinical characteristics. We performed a preliminary intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) calculation among three readers on 40 CT scans. We included in the present study all patients with available baseline or 24 h CT scan for rating of SVD features. Where early ischaemic changes or infarct were too large to allow rating of SVD, evaluation of SVD features was made only in the non-ischaemic hemisphere. We separately graded leukoaraiosis severity in anterior (score: 0–2) and posterior (score: 0–2) with Van Swieten Scale (VSS), obtaining a five-point scale for severity evaluation.13 We defined lacunes as round or ovoidal hypodense lesions ≤20 mm of diameter in basal ganglia, white matter and brainstem. We evaluated cortical and central cerebral atrophy with a three-point scale (0= ‘none’, 1= ‘moderate’ and 2= ‘severe’) against a reference template and summed the single scores to obtain a five-point scale for evaluation of global cerebral atrophy.14 To evaluate global SVD, we assigned 1 point for each of the following if present: lucencies (VSS ≥ 1) in anterior or posterior periventricular white matter, lacunes ≥1 and presence (≥1) of cerebral atrophy. The combined four-point ordinal score evaluated the global burden of SVD ranging from 0 (no imaging features of SVD) to 3 (presence of each SVD feature scored as severe for each imaging variable). The concept of SVD score has been previously tested with regards to cerebral hypoperfusion, clinical outcomes and blood–brain barrier permeability.10,11,15 As previously reported,16 we also combined leukoaraiosis and lacunes into a combined score. Absence of leukoaraiosis and lacunes was marked as 0, presence of one of these as 1 and presence of both as 2.

Statistical analysis

We performed a natural logarithmic transformation of crude values of levels of endothelial dysfunction markers to obtain normally distributed data. We described demographic and clinical characteristics of the population with summary statistics, and used Pearson χ2, Kruskal–Wallis or analysis of variance (ANOVA) test, as appropriate, to test differences among groups. To investigate unadjusted associations, we used the ANOVA of the distribution of baseline and 90-day levels of markers of endothelial dysfunction and (1) single features of SVD and (2) the SVD score. We retained associations with p values <0.1 from the unadjusted analysis and built a multivariable linear regression model adjusting for age, sex, stroke severity, hypertension, diabetes, smoke. We considered statistically significant a p-value <0.05. We carried out statistical analysis with SPSS for Windows (version 22.0; SPSS, Armonk NY, IBM Corp.).

Results

Baseline characteristics of population

From the whole population of the MAGIC study (n = 327), 263 (80%) had CT scan available for SVD assessment. Main reasons for excluded patients were poor quality of images and missed centralisation of the CT scans. Evaluation of cerebral atrophy was not possible in seven patients, and lacune rating was not possible in one patient; this left 255 patients for the analysis of global SVD score (i.e. leukoaraiosis, lacunes, brain atrophy ratings). At 90 days, 21 (8%) patients died, and 44 (18%) of the remaining patients did not have the follow-up blood sample. This left 190 (75%) patients for the 90-day analysis. Regarding SVD signs with CT scans, ICC ranged from good to excellent among three readers (ICC for leukoaraiosis = 0.87; lacunes = 0.76; cerebral atrophy = 0.89).

Main characteristics of population are shown in Table 1. Mean age (±SD) was 69 (±13) years, 154 (59%) were male. Median NIHSS was 12 (IQR = 7–17). Among vascular risk factors, hypertension was the most frequent (62%). Median onset to treatment time was 165 (IQR = 140–180) min. A total of 94 (36%) patients had some degree of leukoaraiosis; 86 (33%) had one or more lacunes; 205 (78%) patients had cerebral atrophy. As expected, patients with leukoaraiosis had higher rates of hypertension (75% versus 55%; p < 0.05) and smoke exposure (43% versus 27%; p < 0.05). Patients with cerebral atrophy more frequently presented hypertension (68% versus 37%; p < 0.05) and atrial fibrillation (26% versus 10%, p < 0.05). No differences were observed between patients with or without lacunes.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the study population.

| Total N = 263 |

Leukoaraiosis |

Lacunesa |

Cerebral atrophyb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PresenceN = 94 | AbsenceN = 169 | PresenceN = 86 | AbsenceN = 176 | PresenceN = 205 | AbsenceN = 51 | ||

| Age, mean±SD | 68.6 ± 12.7 | 74.4 ± 7.8 | 65.3 ± 13.7 | 71.8 ± 10 | 66.9 ± 13.7 | 72.4 ± 9.2 | 53.6 ± 13.3 |

| Sex, male | 154 (59) | 58 (62) | 96 (57) | 53 (62) | 101 (57) | 124 (61) | 27 (53) |

| NIHSS, median (IQR) | 12 (7–17) | 12 (8–17) | 12 (7–17) | 11 (7–15) | 12 (8–18) | 12 (8–18) | 11 (7–14) |

| OCSP-lacunar syndrome | 32 (12) | 10 (11) | 22 (13) | 9 (11) | 23 (13) | 19 (9)* | 13 (27)* |

| Hypertension | 161 (62) | 70 (75)* | 91 (55)* | 58 (68) | 102 (58) | 139 (68)* | 18 (37)* |

| Diabetes | 38 (15) | 12 (13) | 26 (16) | 9 (11) | 29 (17) | 26 (13) | 10 (20) |

| Smokers | 72 (33) | 32 (43)* | 40 (27)* | 27 (40) | 45 (29) | 60 (34) | 9 (24) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 58 (23) | 23 (25) | 35 (21) | 17 (21) | 40 (23) | 52 (26)* | 5 (10)* |

| Congestive heart failure | 33 (13) | 12 (13) | 21 (13) | 12 (14) | 20 (12) | 30 (15) | 3 (6) |

| Systolic BP, mmHg, mean±SD | 141.1 ± 21.7 | 151.3 ± 22 | 144.8 ± 21.3 | 150.9 ± 21.7 | 145.3 ± 21.6 | 148.5 ± 21.8 | 141.7 ± 20.8 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg, mean±SD | 79.6 ± 12.7 | 80.1 ± 13 | 79.3 ± 12.5 | 81.4 ± 11.8 | 78.7 ± 13 | 79.1 ± 12.4 | 80.5 ± 13.8 |

| Leukocytes, n × 103, mean±SD | 8 ± 2.5 | 8.1 ± 2.5 | 7.9 ± 2.5 | 7.7 ± 2.5 | 8.1 ± 2.5 | 7.9 ± 2.5 | 8.4 ± 2.6 |

| Baseline glucose, mg/dl, mean±SD | 129.7 ± 49.9 | 131.3 ± 52.1 | 128.8 ± 48.7 | 131.2 ± 37.3 | 129 ± 55.2 | 130.7 ± 50.8 | 124.2 ± 46.3 |

| Aspirin use | 82 (31) | 35 (38) | 47 (28) | 31 (37) | 51 (29) | 71 (35)* | 9 (18)* |

| Anti-inflammatory drugs | 16 (6) | 4 (4) | 12 (7) | 5 (6) | 11 (6) | 13 (7) | 3 (6) |

| OST, minutes, median (IQR) | 140 (100–165) | 138 (91–165) | 140 (100–165) | 145 (104–165) | 136 (99–165) | 140 (100–165) | 138 (91–165) |

| OTT, minutes, median (IQR) | 165 (140–180) | 170 (154–191) | 165 (135–180) | 170 (149–185) | 165 (139–180) | 165 (140–184) | 167.5 (133–185.5) |

BP: blood pressure; IQR: interquartile range; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; OCSP: Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project; OST: onset to blood sample time; OTT: onset to treatment time; SD: standard deviation.

Data are numbers (%) unless otherwise stated.

aOne missing patient.

bSeven missing patients.

*p < 0.05.

SVD features and baseline levels of biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction

At baseline, levels of vWF were higher in patients with leukoaraiosis (mean 5.1 versus 4.9; p = 0.007) and in patients with cerebral atrophy (5.0 versus 4.9; p = 0.027), whereas there was no difference in patients with lacunes. ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and VEGF levels showed no significant differences in patients with or without SVD signs (see Supplemental table 1).

After adjustment for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes and smoke, neither leukoaraiosis (p = 0.222) nor cerebral atrophy (p = 0.881) was associated with vWF levels.

SVD and 90-day levels of biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction

Ninety-day analysis demonstrated a difference among levels of all markers in patients with SVD signs compared to those without, as shown in Table 2. ICAM-1 levels were increased in patients with leukoaraiosis (mean 12.4 versus 12.1; p = 0.002) and in patients with lacunes (mean 12.3 versus 12.1; p = 0.078), VCAM-1 levels were higher in patients with leukoaraiosis (mean 13.3 versus 12.9; p = 0.002), VEGF was increased in patients with lacunes (mean 4.6 versus 4.0; p = 0.005) and vWF was higher in patients with leukoaraiosis (mean 5.0 versus 4.8; p = 0.012) and with cerebral atrophy (mean 4.9 versus 4.7; p = 0.034).

Table 2.

Biomarker levels at baseline and after 90 days across SVD score.

| SVD Score 0N = 39 | SVD Score 1N = 98 | SVD Score 2N = 72 | SVD Score 3N = 46 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICAM-1 baseline, mean±SD | 12.3 ± 0.6 | 12.2 ± 0.7 | 12.3 ± 0.7 | 12.4 ± 0.6 | 0.688 |

| VCAM-1 baseline, mean±SD | 12.9 ± 0.6 | 12.9 ± 0.7 | 12.8 ± 0.7 | 12.8 ± 1.6 | 0.930 |

| VEGF baseline, mean±SD | 4.7 ± 1.1 | 4.4 ± 1.1 | 4.6 ± 1.0 | 4.8 ± 0.9 | 0.220 |

| vWF baseline, mean±SD | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 5.1 ± 0.5 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 0.016 |

| ICAM-1 90 days, mean±SD | 12.2 ± 0.6 | 11.9 ± 1.0 | 12.4 ± 0.5 | 12.4 ± 0.5 | 0.004 |

| VCAM-1 90 days, mean±SD | 13.1 ± 0.5 | 12.8 ± 1.1 | 13.3 ± 0.6 | 13.3 ± 0.5 | 0.005 |

| VEGF 90 days, mean±SD | 4.0 ± 1.4 | 4.0 ± 1.4 | 4.2 ± 1.1 | 4.7 ± 1.0 | 0.055 |

| vWF 90 days, mean±SD | 4.6 ± 0.7 | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 5.0 ± 0.6 | 5.0 ± 0.7 | 0.041 |

ICAM-1 intercellular adhesion molecule-1; SD: standard deviation; SVD: small vessel disease; VCAM-1: vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; vWF: von Willebrand factor.Bold values = p<0.05

Adjusted linear regression analysis showed an independent association between presence of leukoaraiosis and ICAM-1 (β = 0.21; p = 0.016), and VCAM-1 (β = 0.19; p = 0.025) levels, whereas the association with vWF levels was not confirmed (β = 0.12; p = 0.142). Lacunes were associated to VEGF levels (β = 0.21; p = 0.009), but not with ICAM-1 levels (β = 0.09; p = 0.304).

Cerebral atrophy was not independently associated with 90-day vWF levels (β=−0.01; p = 0.914).

Global SVD burden and biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction

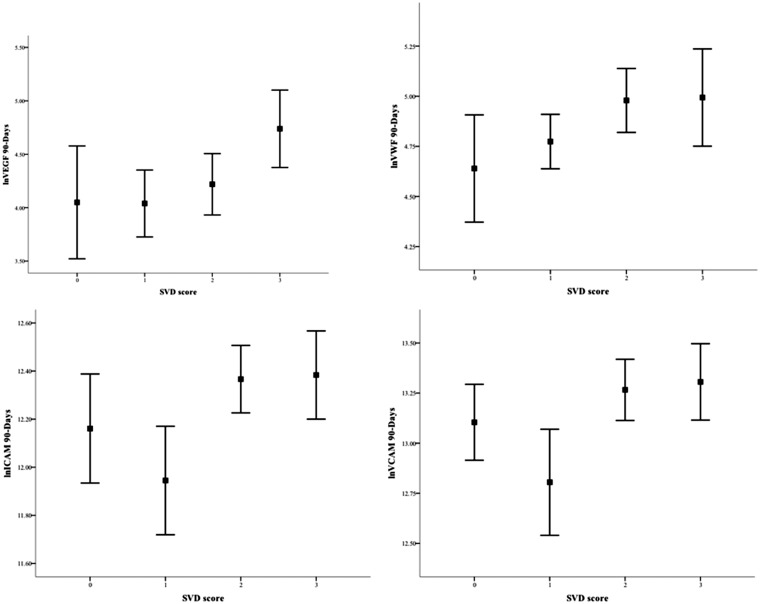

At baseline, only vWF levels were associated with increasing SVD burden; however, in linear regression analysis, the association was not confirmed (β = 0.09; p = 0.274). At 90 days, all markers of endothelial dysfunction were associated with combined features of SVD (Table 2). After adjustment, the SVD score confirmed a non-statistically significant association with ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 (β = 0.18, p = 0.066; β = 0.18, p = 0.065, respectively), whereas there was an independent association between the SVD score and VEGF (β = 0.26; p = 0.006) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Associations between SVD score and markers of endothelial dysfunction at 90 days. Data are means (95% confidence interval).

Considering the score with combined leukoaraiosis and lacunes, and without cerebral atrophy (Supplemental Table 2), only baseline vWF levels showed an increase with the increasing of the score (mean 4.9 versus 5.0 versus 5.1; p = 0.029). At 90 days, univariate analysis showed that levels of ICAM-1 (mean 12.0 versus 12.3 versus 12.4; p = 0.002), VCAM-1 (mean 12.9 versus 13.2 versus 13.3; p = 0.009) and VEGF (mean 4.0 versus 4.3 versus 4.6; p = 0.033) showed a similar increase with higher combined leukoaraiosis and lacunes score. Adjusted linear regression analysis demonstrated that combined leukoaraiosis and lacunes were associated only with 90-day levels of ICAM-1 (β = 0.20; p = 0.024), VCAM-1 (β = 0.20; p = 0.024) and VEGF (β = 0.22; p = 0.009).

Discussion

From a population of acute ischaemic stroke patients treated with rt-PA, we analysed the relationship between CT signs of SVD and biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction at two different time points, representing the acute stroke phase and the steady state. We found that leukoaraiosis, lacunes but not cerebral atrophy were associated with markers of endothelial dysfunction at 90 days. A global SVD score was also associated with endothelial dysfunction at 90 days.

We did not find any association between SVD and endothelial dysfunction during the acute stroke phase. Few studies evaluated biomarkers levels in SVD during the acute stroke phase, and there is a large heterogeneity across studies.8 For example, the time between stroke onset and blood sampling was remarkably different among studies, suggesting a performance bias that may translate in lack of consistency of results. Nonetheless, previous studies demonstrated that blood levels of endothelial and inflammatory biomarkers increase during the acute stroke phase and then return to baseline, suggesting a possible interference of acute phase itself on temporal profile of biomarkers levels.17,18 Our results are in keeping with this hypothesis, showing a lack of association between SVD and endothelial dysfunction during the acute stroke phase.

Instead, at 90 days we found that leukoaraiosis was associated with both ICAM-1 and VCAM-1. ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 are involved in endothelial activation during inflammatory phase, driving the extravasation of inflammatory cells.19 Past studies demonstrated an increase of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 in hypertensive patients, one of the main risk factors of SVD.20,21 Similarly, in a case–control study, Rouhl et al.22 demonstrated that ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 levels were associated with SVD features. Moreover, in 296 elderly stroke-free subjects, Markus et al.6 demonstrated an association between levels of ICAM-1 and increasing white matter lesions volumes after three and six years, suggesting a possible causal role of ICAM-1 for white matter lesions and their progression. Our results support the findings of the aforementioned studies and extend the association in patients with previous stroke and concurrent SVD, thus strengthening the relationship between ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and SVD.

We found that pre-existing lacunar infarcts, as a marker of SVD, were associated with increasing levels of VEGF. VEGF is the most specific growth factor for endothelium and is commonly involved in angiogenesis. An analysis from the Framingham study on 1863 healthy subjects demonstrated that VEGF levels were associated with increased risk of ischaemic stroke.23 Similarly to our findings, VEGF levels were also higher in patients with silent brain infarcts and concurrent lacunar stroke, supporting the association between VEGF and lacunar SVD.24 Furthermore, we found that the combined SVD score showed a meaningful association with VEGF, supporting a key role of VEGF in SVD process. Moreover, the SVD score of leukoaraiosis and lacunes showed associations with ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and VEGF. Such results confirm that assessment of total SVD burden could be useful in the evaluation of the impact of this condition on the brain. In a past study, Hassan et al.5 assessed total SVD burden in 110 patients with lacunar stroke and leukoaraiosis and showed an increase of endothelial activity expressed by ICAM-1 levels related to SVD severity compared to 60 controls. We also found a dose-effect response related to SVD severity and endothelial activity which reinforces our results and suggests a biological gradient of the relationship. Previous attempts of validation of a global SVD score have been performed;10,11,25,26 however, we acknowledge that a SVD score needs derivation and refinement in different settings (e.g. clinical, pathophysiological) with appropriate sample size and study design.

We were not able to demonstrate an association between cerebral atrophy and endothelial dysfunction. Cerebral atrophy has been included among imaging markers of SVD,12 but is also a common finding in neurodegeneration. However, SVD findings are frequently observed in patients with primary neurodegeneration, alluding to an overlap between neurodegeneration and SVD.27–29 Furthermore, as previously suggested by other authors,9,30 the lack of association with brain atrophy may imply that endothelial dysfunction is a specific process linked to SVD rather than to primary neurodegenerative causes.

Our study has limitations. First, we used CT instead of MR (i.e. imaging gold standard) for evaluation of SVD signs. Unavoidably we lost information about SVD using CT (e.g. enlarged perivascular spaces, microbleeds); however, core features of SVD such as lacunes and leukoaraiosis can be detected also with CT. Furthermore, we assessed SVD only at a single time point (i.e. during the acute stroke phase), whereas blood samples were taken at two time points. Progression of SVD might have influenced levels of circulating markers of endothelial dysfunction, but a relevant evolution of SVD in only three months is unlikely. Finally, as a retrospective and cross-sectional study, we cannot draw conclusions about causal relationship between SVD and endothelial dysfunction, rather we report associations in keeping with previous studies, and we suggest that evaluation of SVD and endothelial dysfunction could be more reliable during the steady state and not during the acute phase of stroke.

The strengths of our study are the centralised, blinded and independent rating of SVD features CT scan among three different readers, the centralised analysis of blood samples, the assessment of SVD with qualitative and reproducible standardised scales following experts’ consensus.

In conclusion, in patients with ischaemic stroke we demonstrated a relation between SVD and endothelial dysfunction at 90 days after stroke. Specifically, we observed that leukoaraiosis and lacunes were associated with markers of endothelial dysfunction, and that global SVD burden was consistently associated with VEGF. Our results confirm previous findings, supporting that endothelial dysfunction, particularly VEGF, may be involved in pathologic process of SVD. Acute phase of stroke could confound associations between endothelial dysfunction and SVD; therefore future studies should focus on the steady state rather than on the acute phase.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for Small vessel disease and biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction after ischaemic stroke by Francesco Arba, Alessio Giannini, Benedetta Piccardi, Silvia Biagini, Vanessa Palumbo, Betti Giusti, Patrizia Nencini, Anna Maria Gori, Mascia Nesi, Giovanni Pracucci, Giorgio Bono, Paolo Bovi, Enrico Fainardi, Domenico Consoli, Antonia Nucera, Francesca Massaro, Giovanni Orlandi, Francesco Perini, Rossana Tassi, Maria Sessa, Danilo Toni, Rosanna Abbate and Domenico Inzitari in European Stroke Journal

Acknowledgements

We thank the hospital staff for data collection: M. Acampa, Siena; M. Bacigaluppi, Milano; A. Chiti, Pisa; A. De Boni, Vicenza; M.L. De Lodovici, Varese; F. Galati, Vibo Valentia; N. Marcello, Reggio Emilia; N. Micheletti, Verona; F. Muscia, Como; E. Paolino, Ferrara; P. Palumbo, Prato; P. Tosi, Rozzano; E. Mossello, Firenze; M.R. Tola, Ferrara, M. Torri, Firenze. We thank Dr Paolo Mattiolo for the help in figure preparation.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The main study, Biological Markers Associated with Acute Ischemic Stroke (MAGIC) Study was funded by grants from Italian Ministry of Health, 2006 Finalized Research Programmes (RFPS-2006-1-336520). This study was partially funded by Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze (2010.06.03). The funding body had no role in the study design.

Ethical approval

Study protocol was approved in every participating centre from local ethical committee.

Informed consent

Each patient enrolled in the study received informed consent.

Guarantor

FA is the corresponding author and the guarantor of the present work.

Contributorship

FA, AG, BP, SB, VP, DI, conceived the study, analysed and revised the data, draft the manuscript. BG and AMG analysed laboratory sample and reviewed the draft. GP performed the statistical analysis. PN, MN, GB, PB, EF, DC, AN, FM, GO, FP, RT, MS, DT and RA reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Data access

Coordinating centre (Florence) had full access to the study data. All authors had access to study data upon request to the Coordinating centre. Data are online on a dedicated website (http://www.stroketeam.it/magic/).

References

- 1.Pantoni L. Cerebral small vessel disease: from pathogenesis and clinical characteristics to therapeutic challenges. Lancet Neurol 2010; 9: 689–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norrving B. Lacunar infarcts: no black holes in the brain are benign. Pract Neurol 2008; 8: 222–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wardlaw JM, Smith C, Dichgans M. Mechanisms of sporadic cerebral small vessel disease: insights from neuroimaging. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 483–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevenson SF, Doubal FN, Shuler K, et al. A systematic review of dynamic cerebral and peripheral endothelial function in lacunar stroke versus controls. Stroke 2010; 41: 434–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hassan A, Hunt BJ, O’Sullivan M, et al. Markers of endothelial dysfunction in lacunar infarction and ischaemic leukoaraiosis. Brain 2003; 126: 424–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markus HS, Hunt B, Palmer K, et al. Markers of endothelial and hemostatic activation and progression of cerebral white matter hyperintensities: longitudinal results of the Austrian Stroke Prevention Study. Stroke 2005; 36: 1410–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiseman S, Marlborough F, Doubal F, et al. Blood markers of coagulation, fibrinolysis, endothelial dysfunction and inflammation in lacunar stroke versus non-lacunar stroke and non-stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. Cerebrovasc Dis 2014; 37: 64–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poggesi Pasi M, Pescini F, Pantoni L, et al. Circulating biologic markers of endothelial dysfunction in cerebral small vessel disease: a review. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016; 36: 72–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Staals J, Makin SD, Doubal FN, et al. Stroke subtype, vascular risk factors, and total MRI brain small-vessel disease burden. Neurology 2014; 83: 1228–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arba F, Inzitari D, Ali M, et al. Small vessel disease and clinical outcomes after IV rt-PA treatment. Acta Neurol Scand 2017; 136: 72–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arba F, Mair G, Carpenter T, et al. Cerebral white matter hypoperfusion increases with small-vessel disease burden. Data from the third International Stroke Trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2017; 26: 1506–1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, et al. STandards for ReportIng Vascular changes on nEuroimaging (STRIVE v1). Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 822–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Swieten JC, Hijdra A, Koudstaal PJ, et al. Grading white matter lesions on CT and MRI: a simple scale. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1990; 53: 1080–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collaborative Group IST-3. Association between brain imaging signs, early and late outcomes, and response to intravenous alteplase after acute ischaemic stroke in the third International Stroke Trial (IST-3): secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2015; 14: 485–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arba F, Leigh R, Inzitari D, et al. Blood-brain barrier leakage increases with small vessel disease in acute ischemic stroke. Neurology 2017; 89: 2143–2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arba F, Palumbo V, Boulanger JM, et al. Leukoaraiosis and lacunes are associated with poor clinical outcomes in ischemic stroke patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis. Int J Stroke 2016; 11: 62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horstmann S, Kalb P, Koziol J, et al. Profiles of matrix metalloproteinases, their inhibitors, and laminin in stroke patients: influence of different therapies. Stroke 2003; 34: 2165–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuo R, Ago T, Kamouchi M, et al. Clinical significance of plasma VEGF value in ischemic stroke – research for biomarkers in ischemic stroke (REBIOS) study. BMC Neurol 2013; 13: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang L, Froio RM, Sciuto TE, et al. ICAM-1 regulates neutrophil adhesion and transcellular migration of TNF-alpha-activated vascular endothelium under flow. Blood 2005; 106: 584–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhat SA, Goel R, Shukla R, et al. Platelet CD40L induces activation of astrocytes and microglia in hypertension. Brain Behav Immun 2016; 59: 173–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iadecola C, Davisson RL. Hypertension and cerebrovascular dysfunction. Cell Metab 2008; 7: 476–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rouhl RP, Damoiseaux JG, Lodder J, et al. Vascular inflammation in cerebral small vessel disease. Neurobiol Aging 2012; 33: 1800–1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pikula A, Beiser AS, Chen TC, et al. Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor and vascular endothelial growth factor levels are associated with risk of stroke and vascular brain injury: Framingham study. Stroke 2013; 44: 2768–2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwon HS, Kim YS, Park HH, et al. Increased VEGF and decreased SDF-1α in patients with silent brain infarction are associated with better prognosis after first-ever acute lacunar stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2015; 24: 704–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klarenbeek P, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Rouhl RP, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure in patients with lacunar stroke: association with total MRI burden of cerebral small vessel disease. Stroke 2013; 44: 2995–2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Staals J, Booth T, Morris Z, et al. Total MRI load of cerebral small vessel disease and cognitive ability in older people. Neurobiol Aging 2015; 36: 2806–2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.METACOHORTS Consortium. METACOHORTS for the study of vascular disease and its contribution to cognitive decline and neurodegeneration: an initiative of the Joint Programme for Neurodegenerative Disease Research. Alzheimers Dement 2016; 12: 1249–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kebets V, Gregoire SM, Charidimou A, et al. Prevalence and cognitive impact of medial temporal atrophy in a hospital stroke service: retrospective cohort study. Int J Stroke 2015; 10: 861–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arba F, Quinn T, Hankey GJ, et al. Cerebral small vessel disease, medial temporal lobe atrophy and cognitive status in patients with ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack. Eur J Neurol 2017; 24: 276–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiseman SJ, Bastin ME, Jardine CL, et al. Cerebral small vessel disease burden is increased in systemic lupus erythematosus. Stroke 2016; 47: 2722–2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material for Small vessel disease and biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction after ischaemic stroke by Francesco Arba, Alessio Giannini, Benedetta Piccardi, Silvia Biagini, Vanessa Palumbo, Betti Giusti, Patrizia Nencini, Anna Maria Gori, Mascia Nesi, Giovanni Pracucci, Giorgio Bono, Paolo Bovi, Enrico Fainardi, Domenico Consoli, Antonia Nucera, Francesca Massaro, Giovanni Orlandi, Francesco Perini, Rossana Tassi, Maria Sessa, Danilo Toni, Rosanna Abbate and Domenico Inzitari in European Stroke Journal