Abstract

Achieving ambitious health goals—from the Every Woman Every Child strategy to the health targets of the sustainable development goals to the renewed promise of Alma-Ata of ‘health for all’—necessitates strong, functional and inclusive health systems. Improving and sustaining community health is integral to overall health systems strengthening efforts. However, while health systems and community health are conceptually and operationally related, the guidance informing health systems policymakers and financiers—particularly the well-known WHO ‘building blocks’ framework—only indirectly addresses the foundational elements necessary for effective community health. Although community-inclusive and community-led strategies may be more difficult, complex, and require more widespread resources than facility-based strategies, their exclusion from health systems frameworks leads to insufficient attention to elements that need ex-ante efforts and investments to set community health effectively within systems. This paper suggests an expansion of the WHO building blocks, starting with the recognition of the essential determinants of the production of health. It presents an expanded framework that articulates the need for dedicated human resources and quality services at the community level; it places strategies for organising and mobilising social resources in communities in the context of systems for health; it situates health information as one ingredient of a larger block dedicated to information, learning and accountability; and it recognises societal partnerships as critical links to the public health sector. This framework makes explicit the oft-neglected investment needs for community health and aims to inform efforts to situate community health within national health systems and global guidance to achieve health for all.

Keywords: health systems; health system strengthening; community health; frameworks; maternal, newborn and child health; primary care; health for all, Alma-Ata; SDGs

Summary box.

The six WHO building blocks have become a useful reference point for national and global policymakers; however, critical elements and the dynamic interplay required to implement community health effectively are insufficiently represented in the building blocks.

Service delivery and health workforce approaches often rely on community health workers and strategies, without adequate investment or recognition at the policy level. Community organisations, societal partnerships, household production of health and information systems are often not seen as part of the health system.

Using evidence, we support an expansion of the WHO building block framework, showing dynamism between health system components, and explicit community health needs, which central policymakers should proactively address and resource in order to institutionalise community health within the wider health system.

Even without prescribing particular community health implementation modalities, explicit attention to community-level services, actors and partnerships is necessary to strengthen health systems and provide primary healthcare for all.

A framework which goes ‘beyond the building blocks’ may be useful for national and global policymakers to recognise, prioritise and invest resources in aspects of the health system that promote community health in efforts to reach ambitious global goals.

Introduction

Global efforts to improve health, especially of women, newborns and children, require comprehensive and creative approaches. New global frameworks and calls to action (Every Woman Every Child, People-Centred Health Systems, United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Acting on the Call), all state the value of involving multiple stakeholders in health, including and especially ‘communities’.1–3 The UN’s Global Strategy, similar to other global guidance documents, labels community health work as an ‘essential component of health system resilience’ and community engagement as ‘one of the nine action areas’ required to improve health systems.4–6 The recent Global Conference on Primary Health Care (PHC), held in Astana, Kazakhstan, in 2018, renews past promises and principles of healthcare for all.7

Communities are groups of families, individuals and other types of networks and social circles that provide support and are often the unit on which health activities are organised and focused. Formal health services may be offered at health facilities, such as hospitals and health centres, but many services are provided at the community level, from familial provision of preventive or curative care in the household, to systematic clinical outreach from facilities. While most curative and specialised care should be provided in facility settings, many preventive, preliminary screening and basic treatments may be provided outside of formal facilities. Activities at the community level may also involve advocacy, education, governance, fundraising, inter-sectoral collaborations and other types of indirect support to the health system. Thus, community health has been recognised as foundational to global health, but is often treated in health systems frameworks as a forgotten and rediscovered issue or a secondary consideration.8–11

Health systems frameworks can serve many purposes, including: to describe the structure, organisation, functions and processes of a health system; to conceptualise actions to improve health system performance; or to coordinate and harmonise national and global health systems investment strategies, programme support and tools.12 It is impossible for one framework to serve all needs, as evidenced by the 41 different health systems strengthening frameworks developed from 1972 to 2011 identified in a recent review13 and the oft-quoted idea that ‘all models are wrong, but some are useful’.14 Health systems frameworks attempt to include the most salient aspects of a health system and the interlinked factors underpinning health system functionality and use. However, most of these frameworks exclude, or do not integrate ‘community health’ explicitly.15 Some frameworks include community elements under ‘context’ or ‘population’, but these are generally not operationally useful for planning and design purposes. Some recent recognition of the invisibility of community roles has occurred. For example, the Health Systems Global Research Symposium in 2018 listed a theme: “Community health systems—where community needs are located, but often the invisible level of health systems”.16 Global discourse around the Alma-Ata anniversary and 2018 meeting in Astana has brought yet again attention to the role of communities in providing PHC.7 In this paper, we propose simple but significant changes to a well-known health system framework as a guide or thinking tool for programmers, policymakers and donors of health systems efforts to more consciously include community health.

The WHO’s Health System Framework (also known as the ‘WHO building blocks’) has provided a common language and dominant structure of discourse on health systems issues in the last decade. Its utility, in spite of limitations, is commonly recognised by policymakers, programmers and scholars in global health.8 Although not the original intention of the framework, the WHO building blocks have become a tool for planning, funding decisions and establishing priorities. Its traditional six operational building blocks—service delivery, health workforce, information, medical products and technologies, financing, and leadership and governance—have become shorthand for describing health systems and for guiding investments in health systems strengthening.8 9 11 While ubiquitous, the framework is not without controversy.9 WHO itself has clarified how the framework provides a mapping of six essential groups of inputs required to support or strengthen health systems, but that it is also too static to help navigate the complexity of health systems.17 We fully endorse the evolving and growing school of thought for applying ‘systems thinking’ to the complexity of changes in health systems, but we aim to focus on the building blocks, and how they contribute to a disconnect—and a bias against community health—between health systems interventions and investments, at the policy level.9

Expanded framework

In 2014, the CORE Group—a collaborative network of non-governmental organisations (NGOs)—organised a panel with representatives from Unicef, Pan American Health Organization and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) on the representation of community in health systems frameworks, which concluded that community was everywhere tacitly and nowhere explicitly.11 This was the first in a series of discussions and workshops, through USAID’s Maternal and Child Survival Program’s Community Health Team and the CORE Group Systems for Health Working Group (formerly the Community-Centered Health Systems Strengthening Working Group) to better frame community health as part of health systems strengthening.

The choice to expand the WHO building blocks is intended to build on a well-known framework in wide use, and the concept of an expansion was inspired by a wave of converging efforts. In the 2000s, the CORE Group model for Community/Household Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses (IMCI)—developed with USAID, United Nations agencies and academic partners—was used to complement the IMCI model.18 The global fund developed the community systems framework, providing operational guidance to grantees on the integration of community participation into HIV, tuberculosis and malaria interventions.19 Future health systems published a supplement on ‘Unlocking Community Capabilities’, which explored key community capability domains in health systems research.20 The People-Centered Health model indicates a large role for communities in the co-production of health.2 21 Some international development organisations have adapted the WHO building blocks by adding a ‘seventh’ building block for ‘community’,22 23 and USAID also developed a visual representation of two strands of resources (health-specific and health-enabling) required to create a ‘community health ecosystem’.24

All these efforts convey complementary messages on the challenge of making community health an integral part of health systems plans, while providing enough contextual flexibility for varying regions, settings and political realities. This paper builds on those efforts, and seeks to articulate how to create policy space for the diversity of community health energies and innovations through simple adjustments to the original WHO building blocks.

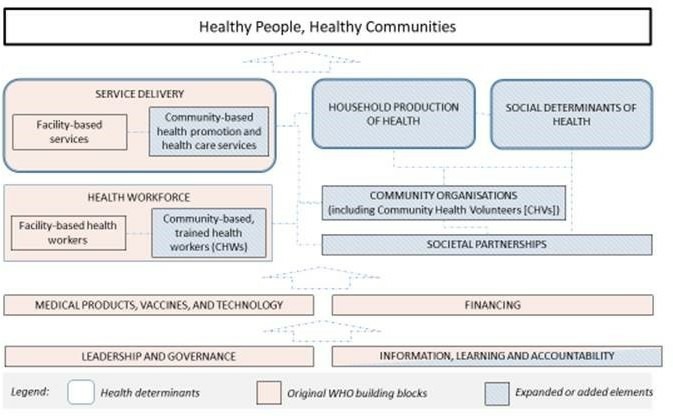

We developed our framework through a participatory process with multiple iterations. First, we conducted a rapid literature review of both published and unpublished papers, based on feedback from community health subject matter experts, which uncovered community aspects related to each of the traditional six building blocks. Following this review, formal discussions were held at three international meetings convened by the CORE Group in Washington, DC; Baltimore, MD; and Seattle, WA, between 2015 and 2017. At these meetings, small groups were organised, with each assigned to consider one component of health systems, which then became the basis for the expanded elements. Groups were provided with documents or references from the initial literature review, and asked to add additional documents that might be relevant. Groups provided detailed oral and written feedback, as well as illustrative case studies. The framework was also presented during the Institutionalizing Community Health Conference, convened by USAID and Unicef in South Africa in 2017, and feedback from participants was solicited.25 26 (As participants were acting as representatives of organisations and not providing personal information or opinions, this was not human subjects research and did not qualify for ethical review.) The framework was revised and shared internally among the partners of the USAID Maternal and Child Survival Program and members of the CORE Group Systems for Health Working Group. Written feedback was sought and these two groups reviewed multiple iterations of the framework, resulting in the version included in this paper (figure 1).

Figure 1.

‘Beyond the building blocks’ expanded framework.

‘Beyond the building blocks’ framework

The objective of our framework is to expand on elements and relationships under-represented in the dominant building block framework. For this reason, systems domains, such as medical products or health financing, for example, which are unquestionably of fundamental importance, receive only rapid treatment in this paper. Additionally, the WHO framework includes responsiveness, financial risk protection and efficiency as outcomes that, in the pursuit of sustainable universal health coverage, are essential. For concision, our framework focuses on health outcomes directly related to healthy communities. We believe that our framework can help policymakers improve responsiveness and efficiency, as well as increase focus on social determinants of health and institutions only indirectly linked to health.

Determinants of health

The top of the framework starts with the determinants of health in communities. What produces healthy communities? Broadly, community health depends on (1) delivery of high quality, evidence-based services (service delivery), (2) household production of health and (3) social determinants of health. All three determinants influence each other.

The evidence for the essential value of community-based services has expanded considerably in the last decades, including for nutrition, immunisation, child health, newborn health and maternal health.3 Community services can be defined differently depending on the operational framework; they can involve health promotion activities, notably through social and behaviour change interventions, or direct community healthcare service delivery. Both Facility-Based and Community-Based Services must be appropriately planned for, with assurances for quality at both levels; however, budgets are frequently skewed toward facilities, with insufficient attention and support for frontline health workers—often, community health workers (CHWs)—and facility outreach activities. Studies have found that funds are often ‘disproportionally spent’ on more specialised care, despite the potential exacerbation of inefficiency and inequity.27–29 Country and regional context, national and local epidemiology, health infrastructure, and policy constraints and opportunities should guide each country and each administrative region to optimally balance the types of services and referrals offered between the community and facility, but all should appropriately resource health promotion, preventive and curative services, and referrals between them. Community initiatives may be very cost-effective, but the absolute cost may be quite high, given the desired scale. Our framework expands the service delivery building block to ensure that both points of service receive attention and resources. As in the WHO building blocks, services can be delivered by public and regulated private sectors, including non-profit private providers.

The second group of determinants includes the household production of health, defined as ‘a dynamic behavioural process through which households combine their (internal) knowledge, resources and behavioural norms and patterns with available (external) technologies, services, information and skills to promote, maintain and restore the health of their members’.30 Household health behaviours are influenced by both proximate and distal factors, including socioeconomic and ecological determinants operating through intermediate variables, such as personal disease control factors, to influence household health behaviours related to disease prevention and treatment.31 32

Formally trained health providers are not always the most important factor for the adoption and maintenance of healthy lifestyles. The WHO estimates that 70%–90% of all healthcare takes place in the home.33 Especially for children, mothers and female relatives are often the primary caregivers, encouraging health-promoting behaviours and identifying illnesses.31 Household prevention and treatment of proximal causes of illness and death start before pregnancy and continue through early childhood. These include maternal nutrition, immediate and exclusive breastfeeding, prevention and management of hypothermia, prevention and knowledge of care seeking for neonatal infections, nutrition and water and sanitation behaviours, such as hand-washing.21 34–39 Households are also on the frontline for the prevention of domestic accidents, promotion of child protection, enabling early childhood development and ensuring gender equity.34

Social determinants of health and environmental conditions predispose people to certain conditions, influence the effects of services and household efforts toward health, affect overall well-being and nutrition and directly determine ability to reach and optimally utilise health facilities. Such social determinants include livelihood and availability of resources for daily needs (housing and food), access to education and economic opportunities, living conditions and the status of women in society.40 Environmental determinants include housing and community design, the built environment, the natural environment (green space and climate) and access to clean water.40 Individuals can be at higher risk for poor health outcomes due to ‘compounded disadvantage’ across multiple social determinants of health.41 This further limits access to health prevention, promotion and curative services.

Achieving ambitious global goals, such as the sustainable development goals, requires attention to social determinants of health.6 Health systems need to appropriately gauge these determinants’ effects on community health at the local level, and to tailor health interventions to correct for social exclusion and prevalent negative social determinants. Beyond health interventions, multisectoral approaches (eg, food security, access to clean water, improved sanitation) will be required to extend services to the hardest-to-reach, addressing the underlying causes of poor health, and implementing effective and sustainable health interventions.41 42

These three types of determinants are critical, although not comprehensive, pathways for achieving health in communities. While not under the exclusive mandate of healthcare services delivery systems, they are under the purview of public health systems programmers, and policymakers need to intentionally develop the elements to address services, household production and social determinants as part of the community health equation.

Health workforce

At the next level, our framework follows the logic of the WHO building blocks with identification of specific human resources necessary, including those at the community level, for the operations of a health system. Health workforce includes both facility-based and community-based health workers, the latter of which may be CHWs or community health volunteers (CHVs), facility staff conducting outreach, or other actors (eg, social workers) providing education, communication, referral, or transport.27 43

Two types of community workers are distinguished in our framework. This ‘dual model’ represents an effort to appreciate management and resourcing differences:

CHWs are community-based health workers with limited training, who are part of the health workforce, and should receive skilled supervision and compensation through an institutionalised mechanism. CHWs offer a variety of services, and may be full-time or part-time, but overall represent a manageable health workforce by public health managers, and are employed by the government, or are regulated by the government and employed by NGOs, or the private sector.

CHVs represent non-professional actors, with more limited training, who are not compensated systematically beyond ad hoc incentives. CHVs may be working across sectors like agriculture and micro-economic development, often on a part-time basis, and may have organised organically into action groups. Although CHVs are often grouped together with paid CHWs, their support needs and interactions with the formal health system may be different, and there may be less governmental oversight. CHVs represent a form of human and social capital, with which public health systems can collaborate.15 Thus, in our framework, the CHVs are included in community organisations.

Our framework also distinguishes facility and community-based workers, since the resources and structures to support CHWs (supplies, equipment, training, infrastructure, supervision and fair pay) are different—yet often less well developed and standardised than those for facility health workers—and require specific management.

The most common maternal, newborn and child health preventive intervention strategies implemented by CHWs are malaria prevention and behaviour change communication often related to promotion of healthy behaviours.44 CHWs have proved effective at promoting newborn care practices (eg, skin-to-skin contact, exclusive breastfeeding, care seeking) and contributing to maternal and neonatal mortality reduction through health communication on family planning, treatment for common illnesses and referrals for complex cases in both urban and rural environments.21 44 45 Well-trained and supervised CHWs can effectively manage and treat common childhood illnesses such as malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoeal disease.46–48 Even for prevention of maternal deaths—where healthcare infrastructure and skilled birth attendance are essential—the community-based distribution of misoprostol, along with education efforts, has helped reduce maternal mortality from postpartum haemorrhage.49 50

CHW programme are not a replacement for health facilities. A Cochrane review found that community members often find CHW promotion activities insufficient for their health needs.51 However, CHWs can complement facility-based systems, especially where health systems and linkages are weak or inaccessible. Community-based service delivery requires a community-based health workforce, managed in close coordination with the facility workforce and other elements. In order to build a useful and respected CHW programme, health systems managers need to dedicate specific attention and resources to recruiting, training, leading toward effectiveness and efficiency, supporting, and compensating this cadre of workers.51 The role of CHWs will vary with context and time, but needs to be considered strategically and be regulated based on country needs and resources.43

Community organisations

Next, we propose community organisations as an essential element for building effective community health systems, based on two essential considerations: (1) communities play a critical role in advancing the determinants of health contributing to service delivery and the health workforce and (2) community organisations are the practical construct through which health systems can engage with communities at scale.

Communities consist of individuals, families, households, kin and non-kin social networks, and various social and community-wide groupings that provide social support, advice, knowledge, behavioural reinforcements, social norms and the social fabric on which many individual behaviours evolve. Evidence is substantial that communities in various forms are key contributors to maternal, newborn and child health, and a recent systematic review suggests an important role for community engagement to directly improve child health outcomes.52–56

Health workers providing regular services and outreach in communities also rely on communities themselves. Communities are where policies and programme for gender equity, economic development, literacy, schooling and other social determinants of health are expressed (either progressive or regressively). For health systems, the question is consequently not whether communities play a role, but how communities can be recognised and elevated within the system. Community members are already active in improving their own lives, survival and health, and the health of the community overall. The more important question is how can health systems practically work with communities to ensure progressive development toward improved health.57 Health sector engagement with communities may take many forms, but working with community organisations—formal or informal, dedicated to health, neighbourhood concerns, or other development purposes—is unavoidable to reach scale. Individual CHWs or district health officers may hold ad hoc meetings with individual community members, but as soon as plans for project replicability or scale-up are established, some form of organising, including potential standardisation, and consultations with larger numbers and more diverse groups of people, will be required. Community organisations can act as a convener of different stakeholders or subgroups and give structure to collaborative processes. Community structures, when valued and effectively used, can amplify the work of CHWs, support the development of practices to help identify, refer and care for sick individuals, compile essential data, and encourage inclusive participation, including in social accountability efforts.58

Various approaches to community engagement, strengthening of community organisations, and support structures have been described and each will follow different modalities.41 Describing the many modalities of community organisation and mobilisation is beyond the scope of this paper, which focuses on the policy and planning requirements to allow for this organisation and mobilisation. However, some examples include care groups,59 60 participatory women’s groups, peer support groups, breastfeeding groups and village committees, which have all shown effectiveness in improving health at the community level.60–64 This area is under-researched, especially at scale, but the number of studies able to demonstrate impact, including on mortality, is increasing.65 Community participation more broadly, through various types of committees and other local community-based organisations, but without direct healthcare visits to home, has also been shown to have an impact on maternal, newborn and child health by building local leadership and mobilising resources.55 66 67

Community organisations are also the required structures to leverage the value of volunteerism. Global health programmes are converging on the idea that volunteers should not and cannot be asked to carry out the full work of professionals, and that community health work requires skills, time and compensation.27 43 This does not indicate; however, that volunteers and CHVs need not be involved; volunteers still have an important role to maximise benefits to communities.68 Community organisations are essential levers to mobilise human capital, and advocate for and ensure fair treatment and roles for members.

Formal health system collaborations with community organisations can be challenging but also have spill-over benefits in terms of increased trust, accountability and social capital, which is associated with improved maternal and child health outcomes.69–71 Government, institution and donor engagement with community organisations should be part of a long-term strategy for performance, sustainability, resilience and responsiveness. As epidemiological conditions change and new challenges arise, these organisations provide a platform for effective country response. The focus needs to shift from building evidence for community engagement—a case already well made—to policymakers creating the space for local evidence and learning for how to maximise the benefits of engaging and working with community organisations over time.72

Societal partnerships

Our framework makes the case for an intentional government consideration of societal partnerships, both in and outside of the health sector. Policy negotiations and mechanisms engaging diverse partners are required to scale-up effective health programmes to achieve national and global health goals. Societal partnerships imply the existence of established policy to encourage official agreements or standardised working arrangements with civil society groups, researchers and service providers (public or private). Innovative financing mechanisms are creating more opportunities for public–private partnerships, but government–non-profit partnerships should move from ad hoc and occasional, to strategic and ambitious.73 This may entail more careful negotiations, as well as long-term commitment to services, results, shared accountability and resources.

Actions designed to improve specific geographic communities are, by definition, local. Centralised and decentralised health systems leaders may both be constrained in reaching and managing small and dynamic organisations effectively and at scale. Despite flaws, civil society and NGOs often serve fundamental functions in community health service delivery, community engagement and social accountability,74–76 and often are not confined only to the scope of health activities. These organisations and agencies vary in size, scope, reach and mission, but acknowledgement by policymakers of the important functions served by these groups could help better define their roles in supporting regional and national systems.

Given the importance of social determinants and household production of health, actors outside of the health sector need to be engaged strategically. In 2011, WHO called for inter-sectoral action on health with the ‘aim to integrate a systematic consideration of health concerns into all other sectors’ routine policy processes, and identify approaches and opportunities to promote better quality of life’.77 An array of global health challenges are inter-sectoral in nature (eg, pollution, deforestation, non-communicable diseases, transportation, zoonoses and emerging infectious disease threats) and will therefore best be addressed through multisectoral partnership approaches.41 While health systems have specific jurisdictions, there needs to be strategic consideration of the long-term partnerships required across sectors to achieve community health. This collaboration across education, economic development, livelihood, social protection, nutrition, agriculture, employment and water and sanitation is a requirement for strengthening systems for health and may be easier to facilitate at local levels.76 78

Societal partnerships will be contextually defined based on geography, demography, politics and ethnic and religious diversity. However, health ministries, as duty-bearers in promoting community health, should explore contextual-specific partnerships to achieve responsiveness, promote inclusion and strive for adaptive capacity at scale beyond just the latest innovative interventions. Partnership with civil society should not be a side effect of project investments. The specific required partnerships to achieve specific public health goals will vary by region and epidemiological need, but our framework suggests that partnership in and out of the health sector should be considered systematically with dedicated intellectual, human and financial resources.

To illustrate the importance of these two new building blocks—community organisations and societal partnerships—three case studies were developed in consultation with local community health practitioners from Ethiopia, Nepal and Liberia (Box 1).

Box 1. Examples of societal partnerships and engagement of community organisations to integrate community health in health systems strategies.

Ethiopia

In Ethiopia, the Federal Ministry of Health partnered with Save the Children and other stakeholders to strengthen Kebele Command Posts (KCPs) in support of community health. The programme was a demand creation strategy for maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH) that was integrated into the national Community-Based Newborn Care (CBNC) programme. KCPs are an existing community platform working on local development issues. Membership includes a Kebele Manager (a Kebele is the lowest administrative unit), a political appointee, a school director, a health extension worker, an agriculture development agent and a representative from the women and youth associations. As part of the demand creation strategy, KCPs were strengthened in 245 districts (20 KCPs per district) by expanding membership to include a broader group of stakeholders, and maintaining a gender balance. This included the addition of respected elders, women in leadership (through the Health Development Army), faith-based leaders, traditional birth attendants (in a non-clinical role) and families affected by a maternal or newborn death. The strengthened KCP worked together to identify problems affecting mothers and newborns, develop a community action plan and implement actions, such as support to emergency transport systems, early pregnancy reporting and creating family friendly maternal health services. The strengthened KCP was able to explore the underlying issues affecting MNCH-CBNC in their community, expand the available work force to implement health activities, and integrate changes into the health centre (eg, cash or in-kind contributions to sustain the running of maternity waiting homes). An evaluation of the MNCH-CBNC demand creation strategy showed that the new members of the KCP were supported by district leadership and were seen as a key component for sustainability of demand creation activities. Further, by working with a strengthened KCP with improved organisational capacity, membership and skills, the Federal Ministry of Health and Save the Children were able to improve access to and quality of health services by shifting social norms and attitudes to support the health of mothers and newborns.25

Nepal

In Nepal, the National Planning Commission developed and rolled out a national Multi-sector Nutrition Plan (MSNP, 2012–2017, followed by MSNP II 2018–2022), that included provision for Nutrition and Food Security steering committees at all three levels of government: federal, provincial and local. The plans illustrate how societal partnerships can enrich health sector governance by involving multiple government ministries (finance; health; agriculture; water and sanitation; education; federal affairs and local development; livestock and birds; agriculture; and women, children and social welfare), external development partners, civil society and the private sector to engage with one another to address nutrition and food security from multiple perspectives. The local steering committees specifically serve to coordinate, guide and monitor the application of multisector principles and approaches for improving nutrition and food security in district and village development committee plans. They bring together stakeholders at the municipal level to promote ‘citizen participation in deciding budget allocation, and in bringing together leaders from multiple sectors to plan, coordinate and influence Village Development Committee and district-level funding’.76 95

Liberia

In recent years, Liberia revised its community health policy largely in response to the deadly Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak of 2014–2015 that further weakened an already fragile health system. During the outbreak, millions were left without access to services as health facilities closed and community distrust of the health system grew. At the onset of the outbreak, the country mounted a response with limited community engagement and participation and little consideration of societal partnerships. This negatively affected the effectiveness of the EVD response and accelerated the spread of EVD cases in the communities. Arising from the outbreak, Liberia resolved in its ‘Investment Plan for Building a Resilient Health System 2015–2021’ that it would ‘ensure an enabling environment that restores trust in the health authorities’ ability to provide services through community engagement in service delivery and utilisation, governance and accountability at all levels’. Accordingly, the country embarked on a policy revision process to institutionalise a community health program and establish a workforce able to deliver community-based services in remote areas. To accomplish this, the Ministry of Health and its partners undertook a bottleneck analysis of the existing community health programme and recognised the key principles of community ownership and participation. Societal partnerships were promoted via a strong coordination structure set-up at the national level involving all relevant technical divisions at the Ministry of Health, other relevant sectors (including the Ministry of Internal Affairs with oversight for the local government structures and Ministry Finance and National Planning), donors and developmental partners, international and national non-governmental organisations. The policy revision process was consultative and inclusive involving district and county health authorities, the local administrative and political structures, civil society organisations and community-based groups including community health volunteers. The revised policy has set the stage for the deployment of a cadre of community workers that is strongly embedded within the health systems and at the same time engaged with communities.96

Medical products, vaccines and technology

Medical products, including vaccines and innovative technologies endure as an essential element of the original WHO building blocks. Effective procurement, supply management and quality assurance are essential requirements at the community level. They carry both similar and distinctive challenges to facility-based supply, such as fewer products and a more distributed geographic scale. However, when community health is treated as an afterthought of formal conceptualisations of health systems, procurement and supply management of drugs and commodities for community health services can emerge as a parallel system, and technologies only available at tertiary level facilities may not be available to more isolated or rural communities.79 However, reliance on development partners should progressively be replaced, where possible, by full institutionalisation of community health resourcing in national maternal, newborn and child health strategies. Policies, including international trade agreements, which support the local development, production and distribution of technologies, should be promoted. New products and technologies should be placed to benefit individuals and communities in the most equitable and egalitarian ways possible, even when the most isolated communities are the most expensive to reach.

Financing

Appropriate financing levels and arrangements for community health in all essential WHO building blocks is a requirement for success. Community health investments are cost-effective, but this is too often mistakenly considered as equivalent to low-cost. Financing community health covers many items which, aggregated over technical interventions and geographic scale, add to substantial investments.27 28 43 Value for money cannot be achieved if the full cost of providing community interventions is insufficiently accounted for or not prioritised. Further, financing must go beyond the resources needed for direct health services to include a broader range of functions that support health services, institutions, partnerships and community well-being.

Leadership and governance

Our framework reiterates the central importance of leadership and governance of health systems. We draw attention to a few essential points, based on our proposed amendments to the framework, including the need for inter-sectoral collaboration, as well as dynamic communication between national, district and local levels. In most countries, the Ministry of Health has the regulatory and leadership role for health sector governance, and this governance is shared for specific tasks with other national ministries and local government at decentralised levels. Effective governance involves private sector stakeholders, both non-profit and for-profit, and each level has leadership, planning, controlling and resourcing responsibilities, including through supportive supervision and clinical governance.

Governance and leadership at each level affects all other functions of the health system. Policymakers need to accurately cost the essential elements of community health at scale, and must be prepared to advocate for greater resources to be allocated for such activities. In decentralised models, there may be a wider range of partners involved in delivering care and setting health policy; this adds complexity, but also presents an opportunity for increasing inter-sectoral collaboration. These types of collaborations may be easier to facilitate at local levels, where scopes may be more manageable, individuals may be more accessible, and outcomes may be more visible.78 Decentralised systems, which may struggle more with standardisation, may have more agility to be responsive when disasters occur or local health priorities change. Systems to support community participation in responsiveness planning must be appropriately resourced and can benefit the health system as a whole.80

Information, learning and accountability

The original WHO building blocks include a ‘health information’ block, demonstrating that reliable, timely and actionable information flows are essential to oversight and management of health systems. Our framework expands the definition to explicitly emphasise the value of learning and accountability as end goals of this investment. Improved information and transparency in data-sharing and policymaking can also improve accountability and governance.81

Data need to be generated through processes that create meaning as well as differentiated and actionable information by each level of the health system—including community actors’ level—and between levels of the system. The production, transmission and analysis of information requires a set of skills, technology, processes, investments and actors at not only the national, but also district and local levels. Information, learning and accountability relate to all of the other blocks of the health system, with different applications. Accountability is the bridge mechanism between policymakers and their intended beneficiaries.

Accountability, both administrative and social, relies on information and occurs at different levels and between different stakeholders. Recent work has shown both the importance of social accountability, and its limitations when pursued in isolation from broader multilevel change.82–85 As with learning, accountability entails much broader processes than the collection of data and the production of indicators. Social accountability efforts have shown potential for integration into community health processes and frontline service delivery, and have shown promising results for improving quality and participation.86 For example, community structures can be instituted to improve communication and allow for better feedback and accountability at local levels.86 However, accountability, as governance, needs to be operationalised at multiple levels, and there is a need for vertical integration of accountability throughout the layers of the health system.87

Conclusions

Our framework builds on the WHO building blocks—an existing high-level framework—as well as previously designed frameworks, to make explicit elements that are known but often overlooked in planning and resourcing community health programme. Much of health practice already takes place in the home and at the community level, and evidence is mounting about the effectiveness of community health actors not only in health education and disease prevention, but in treatment as well.30 88 Frameworks that better reflect this reality will be more useful to policymakers to better plan for and direct resources to where they might be most impactful.

As all frameworks, it has inherent limitations. The framework is not based on an exhaustive review of the literature or community programme, but rather represents a range of documented and shared experiences. Our framework does not answer the specifics of how a given health programme can be operationalised, but rather presents an argument for required ‘ingredients’ for effective, quality and scaled community health components of a health system. While ‘blocks’ represent useful defining elements of health systems, they are limited in the ability to describe essential and interrelated functions of a system.17 89 Our expanded framework is designed to focus on the macro level, highlighting the nodes of a network of relationships, and defining necessary types of inputs rather than operationalisation conditions, which will depend on history, context, public health priorities and local implementation. We do not describe all the types of services and interventions that CHWs can carry out in any given location, nor do we stipulate what specific activities can be supported through community members, volunteers, or groups.58 The elements of our framework, as in the original, are far more complex and richer than conceptualised. Adding a block for community organisations, for example, does not describe all the ways in which it is possible or effective to organise the energy of a community, but in almost any manifestation, this would require planning and resources. As long as policymakers create the space and designate sufficient resources, implementers will be able to test different models and design effectively in context.

Country and local leaders need to continue negotiating viable arrangements and evaluate them through rigorous methods for clinical, epidemiological and implementation research. Effectiveness, equity, cost, sustainability, resilience and adaptation to regional conditions within countries are legitimate lenses for defining the ‘how’ of effective community health in each context. What we posit is that the basic elements of this framework will all be required to build a well-performing health system inclusive of community health. Partnering strategically with civil society, establishing socially beneficial regulatory frameworks for the private sector, and proactively advancing health impact through partnerships outside of the health sector may be overlooked and under-resourced by ministries of health focused on the traditional six WHO building blocks. For community health, the ad hoc nature of partnerships with civil society groups can be an impediment to performance and resilience.

With renewed attention to primary health and health for all, the focus on community health will increase. At the Global Conference on Primary Health Care, 40 years after the Alma-Ata Declaration, PHC was defined as ‘an inclusive, community-led, multisectoral approach to promoting population health and preventing illness, as well as a means to provide curative and rehabilitative services’.90 For communities to lead the process, they must be recognised and valued as integral parts of the health system.

Households and communities are often responsible for many aspects of healthcare, especially for newborns and young children, from health education and illness prevention, to either provision of treatment or referral to care.30 88 Community organisations play important roles in navigating epidemiological, demographical and political shifts. Communities are often on the front lines in emergencies: recent literature regarding the role of civil society emerged post-Ebola in West Africa, as it did in severe health situations elsewhere.91–94 Strengthening health systems to better prepare for disruptions and stressors should occur at all levels, so as to continuously provide primary care to all.

In order to achieve health for all, health systems leaders, donors and policymakers need to develop health systems strategies, plans, budgets and resource allocations with the goal of building inclusive and pluralistic health systems. These systems should aim to address the determinants of health in communities; create societal partnerships with other sectors, civil society and local government; and resource community organisations behind shared health objectives, while respecting their identity and agency, welcoming and promoting diverse contributions to the governance and accountability agenda of responsive and adaptable health systems. We are hopeful that by presenting an expanded framework with key levers, conditions can be created for dialogue among stakeholders, including policymakers, planners and financiers, by considering the framework’s blocks as elements to balance around the values, purpose, resources and existing capacity of a health system.

To renew the promise of Alma-Ata and achieve health for all, the roles of communities must be taken seriously, not only in theory, but also in practice. While investing in community health promises a high return on investment, especially for women, newborns, children and families, these resources need to be clearly allocated to the highest impact interventions at the proper scale. Our framework suggests that this must include community-based service delivery and workforce, community organisations, and a range of actors including volunteers, diversified societal partnerships and dedicated efforts at learning and accountability.

Successful integration of community health in national health systems depends on the planning and considerations of national leaders and agents. Policymakers should be encouraged by this framework to question explicitly the elements and relationships required to build viable and resilient health systems for the era of the sustainable development goals. Only through commitment to engaged and sustainable partnership between sectors, stakeholders and systems can ‘health for all’ be achieved.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was made possible in part by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), under the Cooperative Agreement AID-OAA-A-14-00028. The contents are the responsibility of The Maternal and Child Survival Program (MCSP) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Thanks to the CORE Group Systems for Health Working Group (formerly the Community-Centered Health Systems Strengthening Working Group). Thanks to Reeti Desai Hobson and Halkeno Tura for assistance with the literature review, and Saron Worku for editorial assistance. The idea for this concept was developed at the CORE Group’s Global Health Practitioner Conference in 2014, with presenters Amalia Del Riego (PAHO), Ngashi Ngongo (Unicef) and Karen Kavanaugh (USAID), and was further refined at the 2015 Global Health Practitioner Conference. We thank the participants of both sessions. Thanks to Jennifer Nielsen and Pooja Pandey for their feedback on the Nepal case example, and to colleagues who provided review and feedback on drafts at various stages of development, including Grace Chee, Nazo Kureshy, Joseph Petraglia, Annie Portela, Josefien Van Olmen and Peter Winch. Sections of this manuscript were presented at the Institutionalizing Community Health Conference (ICHC) in Johannesburg in March 2017, the American University Research Symposium on Power in Global Health in Washington DC in May 2017, and the CORE Group’s Global Health Practitioner Conference in Baltimore in September 2017, a satellite session of the Health Systems Research Symposium in Liverpool in October 2018, the Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association in November 2018, and at the Harnessing the Power of Communities to Achieve Equity and Primary Health Care for All meeting in Bethesda, Maryland, in May 2019. The authors wish to thank the organisers of these events, and participants at these meetings for insightful feedback.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Stephanie M Topp

Contributors: E. Sacks, M. Morrow, W. Story, M. Rahimtoola, D. Shanklin, and E. Sarriot conceptualised the paper. E. Sacks wrote the first draft. W. Story oversaw the literature review, with support from K. Shelley and E. Sacks. M. Morrow, W. Story, O. Ibe, and E. Sarriot researched and drafted the case studies. All authors reviewed and approved the final text.

Funding: This study was supported by USAID/Maternal and Child Survival Program, Cooperative Agreement AID-OAA-A-14-00028.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. United Nations Every woman every child. New York: United Nations; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization WHO global strategy on People-Centered and integrated health services: interim report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. USAID Acting on the call ending preventable child and maternal deaths: a focus on health systems. USAID: Washington, DC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. United Nations Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescent's Health & Every Woman Every Child Initiative. New York: United Nations; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization, Healthy systems for universal health coverage – a joint vision for healthy lives, world Health organization and international bank for reconstruction and development / world bank. Washington, DC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization Sustainable development goals: 17 goals to transform our world World Health Organization; 2017. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ [Google Scholar]

- 7. International Conference on primary health care, 2018. Available: https://www.who.int/primary-health/conference-phc/

- 8. WHO Everybody's business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: who's framework for action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mounier-Jack S, Griffiths UK, Closser S, et al. Measuring the health systems impact of disease control programmes: a critical reflection on the WHO building blocks framework. BMC Public Health 2014;14 10.1186/1471-2458-14-278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. USAID Health system assessment approach (HSAA) V3. HFG project, 2017. Available: https://www.hfgproject.org/the-health-system-assessment-approach-a-how-to-manual/

- 11. Golding L. Strengthening community health systems through CHWs and mHealth. Washington, DC: CORE Group; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shakarishvili G, Atun R, Berman P, et al. Converging health systems frameworks: towards a Concepts-to-Actions roadmap for health systems strengthening in low and middle income countries. Global Health Governance 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hoffman SJ, Rottingen J-A, Bennett S, Lavis JN, Edge JS, Frenck J. Background paper of conceptual issues related to health systems research to inform a WHO global strategy on health systems research. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Box GEP. Science and statistics. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1976;71:791–9. 10.1080/01621459.1976.10480949 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sacks E, Swanson RC, Schensul JJ, et al. Community involvement in health systems strengthening to improve global health outcomes: a review of guidelines and potential roles. Int Q Community Health Educ 2017;37:139–49. 10.1177/0272684X17738089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Health systems global symposium, 2018. Available: www.healthsystemsglobal.org/

- 17. Savigny D, Taghreed A. Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Winch PJ, Leban K, Casazza L, et al. An implementation framework for household and community integrated management of childhood illness. Health Policy Plan 2002;17:345–53. 10.1093/heapol/17.4.345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. The Global Fund Community systems strengthening framework. Geneva, Switzerland: The Global Fund; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20. George AS, Scott K, Sarriot E, et al. Unlocking community capabilities across health systems in low- and middle-income countries: lessons learned from research and reflective practice. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16 10.1186/s12913-016-1859-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, et al. What works? interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. The Lancet 2008;371:417–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61693-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Health systems strengthening. London, UK: Health Partners International; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Foundation for Professional Development, Technical Assistance, Foundation for Professional Development – South Africa, 2017. Available: https://www.foundation.co.za/t-a

- 24. Community health framework: version 1.0. Washington, DC: USAID; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Core group conference reports. Washington, DC; 2018. <https://coregroup.org/resources/conference-reports/> [Google Scholar]

- 26. Institutionalizing community health Conference, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2016. Available: http://www.ichc2017.org/

- 27. Dahn DB, Woldermariam DAT, Perry DH. Strengthening primary health care through community health workers: investment case and financing recommendations John Hopkins University, the Office of the UN Special Envoy for the health-MDGs, the World Bank, Partners in Health, Last Mile Health, the Clinton Foundation, ALMA and the governments of Ethiopia and Liberia; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28. MCSP Costs and cost-effectiveness of community health investments in reproductive, maternal, neonatal, and child health. Washington DC: USAID Maternal and Child Survival Program; 2017. https://www.mcsprogram.org/resource/costs-cost-effectiveness-community-health-investments-reproductive-maternal-neonatal-child-health/ [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barroy H, Vaughan K, Tapsoba Y. Towards universal health coverage: thinking public. Overview of trends in public expenditure on health (2000-2014). World Health organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available: https://www.who.int/health_financing/documents/towards-uhc/en/

- 30. Berman P, Kendall C, Bhattacharyya K. The household production of health: integrating social science perspectives on micro-level health determinants. Soc Sci Med 1994;38:205–15. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90390-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mosley WH, Chen LC. An analytical framework for the study of child survival in developing countries. Popul Dev Rev 1984;10:25–45. 10.2307/2807954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sirageldin I, Mosley W, Levine R, et al., Towards More Efficacy in Child Survival. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University, School of Hygiene & Public Health, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Murray C, Lopez A, Rodgers A, et al. Chapter 5: choosing interventions to reduce specific risks. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kerber KJ, de Graft-Johnson JE, Bhutta ZA, et al. Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health: from slogan to service delivery. Lancet 2007;370:1358–69. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61578-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Bahl R, et al. Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost? Lancet 2014;384:347–70. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60792-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Debes AK, Kohli A, Walker N, et al. Time to initiation of breastfeeding and neonatal mortality and morbidity: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013;13 Suppl 3 10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Luby SP, Agboatwalla M, Feikin DR, et al. Effect of handwashing on child health: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2005;366:225–33. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66912-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Omer K, Mhatre S, Ansari N, et al. Evidence-based training of frontline health workers for door-to-door health promotion: a pilot randomized controlled cluster trial with lady health workers in Sindh Province, Pakistan. Patient Educ Couns 2008;72:178–85. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shankar AH, Jahari AB, Sebayang SK, et al. Effect of maternal multiple micronutrient supplementation on fetal loss and infant death in Indonesia: a double-blind cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2008;371:215–27. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60133-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. CSDH Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Advancing community health across the continuum of care, 2015, core group, April 2015, presentation at the core group spring conference. Available: <https://coregroup.org/wp-content/uploads/media-backup/documents/Spring_Conference_2015/Spring_2015_GHPC_Booklet_Final.pdf>

- 42. Bessenecker C, Walker L. Reaching communities for child health: advancing health outcomes through Multi-Sectoral approaches. Washington DC: CORE Group; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 43. MCHIP Developing and strengthening community health worker programs at scale: a reference guide for program managers and policy makers. Baltimore MD: Jhpiego; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gilmore B, McAuliffe E. Effectiveness of community health workers delivering preventive interventions for maternal and child health in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013;13 10.1186/1471-2458-13-847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Marcil L, Afsana K, Perry HB. First steps in initiating an effective maternal, neonatal, and child health program in urban slums: the brac Manoshi project's experience with community engagement, social mapping, and census taking in Bangladesh. J Urban Health 2016;93:6–18. 10.1007/s11524-016-0026-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Langston A, Weiss J, Landegger J, et al. Plausible role for CHW peer support groups in increasing care-seeking in an integrated community case management project in Rwanda: a mixed methods evaluation. Global Health: Science and Practice 2014;2:342–54. 10.9745/GHSP-D-14-00067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mugeni C, Levine AC, Munyaneza RM, et al. Nationwide implementation of integrated community case management of childhood illness in Rwanda. Glob Health Sci Pract 2014;2:328–41. 10.9745/GHSP-D-14-00080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rodríguez DC, Shearer J, Mariano ARE, et al. Evidence-informed policymaking in practice: country-level examples of use of evidence for iCCM policy. Health Policy Plan 2015;30 Suppl 2:ii36–45. 10.1093/heapol/czv033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hofmeyr GJ, Gülmezoglu AM, Novikova N, et al. Misoprostol to prevent and treat postpartum haemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis of maternal deaths and dose-related effects. Bull World Health Organ 2009;87:666–7. 10.2471/BLT.08.055715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sanghvi H, Ansari N, Prata NJV, et al. Prevention of postpartum hemorrhage at home birth in Afghanistan. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2010;108:276–81. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Glenton C, Colvin CJ, Carlsen B, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of lay health worker programmes to improve access to maternal and child health: qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(10):CD010414 10.1002/14651858.CD010414.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Black RE, Taylor CE, Arole S, et al. Comprehensive review of the evidence regarding the effectiveness of community–based primary health care in improving maternal, neonatal and child health: 8. summary and recommendations of the expert panel. J Glob Health 2017;7 10.7189/jogh.07.010908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Perry HB, Rassekh BM, Gupta S, et al. Comprehensive review of the evidence regarding the effectiveness of community-based primary health care in improving maternal, neonatal and child health: 1. rationale, methods and database description. J Glob Health 2017;7 10.7189/jogh.07.010901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rifkin SB. Examining the links between community participation and health outcomes: a review of the literature. Health Policy Plan 2014;29 Suppl 2:ii98–106. 10.1093/heapol/czu076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rosato M, Laverack G, Grabman LH, et al. Community participation: lessons for maternal, newborn, and child health. Lancet 2008;372:962–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61406-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Underwood C, Boulay M, Snetro-Plewman G, et al. Community capacity as means to improved health practices and an end in itself: evidence from a multi-stage study. Int Q Community Health Educ 2013;33:105–27. 10.2190/IQ.33.2.b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kutalek R, Wang S, Fallah M, et al. Ebola interventions: listen to communities. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e131 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70010-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. LeBan K. How social capital in community systems strengthens health systems: people, structures, processes. Washington, DC: CORE Group; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Perry H, Morrow M, Borger S, et al. Care groups I: an innovative community-based strategy for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health in resource-constrained settings. Global Health: Science and Practice 2015;3:358–69. 10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Perry H, Morrow M, Davis T, et al. Care groups II: a summary of the child survival outcomes achieved using volunteer community health workers in resource-constrained settings. Global Health: Science and Practice 2015;3:370–81. 10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Progress Pfor. Global evidence for peer support: humanizing health care, Peers for progress. NC: Chapel Hill, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chapman DJ, Damio G, Young S, et al. Effectiveness of breastfeeding peer counseling in a low-income, predominantly Latina population: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004;158:897–902. 10.1001/archpedi.158.9.897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Prost A, Colbourn T, Seward N, et al. Women's groups practising participatory learning and action to improve maternal and newborn health in low-resource settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2013;381:1736–46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60685-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sokol R, Fisher E. Peer support for the hardly reached: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2016;106:e1–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Farnsworth SK, Böse K, Fajobi O, et al. Community engagement to enhance child survival and early development in low- and middle-income countries: an evidence review. J Health Commun 2014;19 Suppl 1:67–88. 10.1080/10810730.2014.941519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Björkman M, Svensson J. Power to the People: Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment on Community-Based Monitoring in Uganda * . Q J Econ 2009;124:735–69. 10.1162/qjec.2009.124.2.735 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Manandhar DS, Osrin D, Shrestha BP, et al. Effect of a participatory intervention with women's groups on birth outcomes in Nepal: cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;364:970–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17021-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sarriot E. Community health workers and health volunteers: leaving old debates behind. Huffington post. Institutionalizing community health conference Blog series. Available: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/community-health-workers-health-volunteers-leaving_us_58da6bc5e4b04f2f079272f5 [Accessed 28 Apr 2017].

- 69. De Silva MJ, Harpham T. Maternal social capital and child nutritional status in four developing countries. Health Place 2007;13:341–55. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Story WT. Social capital and the utilization of maternal and child health services in India: a multilevel analysis. Health Place 2014;28:73–84. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Weiss J. 'CHW peer support groups: an alternative approach to supportive supervision lessons from the Rwanda. Kabeho Mwana child survival project. USAID presentation at the Integrated Community Case Management. (iCCM): Evidence Review Symposium, Accra, Ghana, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 72. George AS, LeFevre AE, Schleiff M, et al. Hubris, humility and humanity: expanding evidence approaches for improving and sustaining community health programmes. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Atun R, Knaul FM, Akachi Y, et al. Innovative financing for health: what is truly innovative? Lancet 2012;380:2044–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61460-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Horton R. Offline: Uncivil Society. The Lancet 2016;387 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00679-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Sarriot EG, LeBan K, Sacks E, et al. Uncivil and skewed language on civil society? Lancet 2016;387 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30731-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Story WT, LeBan K, Altobelli LC, et al. Institutionalizing community-focused maternal, newborn, and child health strategies to strengthen health systems: a new framework for the sustainable development goal era. Global Health 2017;13 10.1186/s12992-017-0259-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.First global Ministerial conference on healthy lifestyles and noncommunicable disease control. Moscow, Russia: World Health Organization; 2011. https://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncds_policy_makers_to_implement_intersectoral_action.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 78. Costello A. The social edge: the power of sympathy groups for our health, wealth and sustainable future. UK: Thornwick, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hejna E, Sarriot E. Systems effects of community case management projects. country report 1/3: Mozambique. Washington DC: Save the Children; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Rosales A, Yepes-Mayorga A, Arias A, et al. A cross-sectional survey on ZIKV in Honduras. International Journal of Health Governance 2017;22:83–92. 10.1108/IJHG-11-2016-0053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81. USAID Better health? composite evidence from four literature reviews. HFG project, 2017. Available: https://www.hfgproject.org/better-health-composite-evidence-from-four-literature-reviews/

- 82. Fox JA. Social accountability: what does the evidence really say? World Development 2015;72:346–61. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.03.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Gullo S, Galavotti C, Altman L. A review of care's community score card experience and evidence. Health Policy Plan 2016;31:1467–78. 10.1093/heapol/czw064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Ho LS, Labrecque G, Batonon I, et al. Effects of a community scorecard on improving the local health System in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo: qualitative evidence using the most significant change technique. Confl Health 2015;9 10.1186/s13031-015-0055-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Wetterberg A, Brinkerhoff D, Hertz J. No. BK-0019-1609 Governance and service delivery: practical applications of social accountability across sectors. RTI Press Publication: Research Triangle Park, NC; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Altobelli LC. Effectiveness in Primary Healthcare in Peru : Beracochea E, Improving aid effectiveness in global health. New York, New York: Springer, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Fox J. Scaling accountability through vertically integrated civil society policy monitoring and advocacy. UK: The Institute of Development Studies; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Baqui AH, El-Arifeen S, Darmstadt GL, et al. Effect of community-based newborn-care intervention package implemented through two service-delivery strategies in Sylhet district, Bangladesh: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008;371:1936–44. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60835-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. van Olmen J, Marchal B, Van Damme W, et al. Health systems frameworks in their political context: framing divergent agendas. BMC Public Health 2012;12 10.1186/1471-2458-12-774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Alma-Ata 40 Roundable group, 2018. implementing the Astana Declaration—What Alma-Ata taught us. health affairs blog. Available: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20181024.24072/full/

- 91. Beekman G, Bulte E, Peters B, Voors M. Civil society organisations in Liberia and Sierra Leone during the Ebola epidemic: a cross-section of changes and responses. Netherlands: Wageningen University; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 92. Gillespie AM, Obregon R, El Asawi R, et al. Social mobilization and community engagement central to the Ebola response in West Africa: lessons for future public health emergencies. Glob Health Sci Pract 2016;4:626–46. 10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. United Nations Development Programme Recovering from the Ebola crisis. New York, NY: World Bank, European Union and African Development Bank; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 94. Walker J. Civil society's role in a public health crisis. Science and Technology 2016;32. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Government of Nepal National Planning Commission, Multi-sector nutrition plan for accelerating the reduction of maternal and child under-nutrition in Nepal 2013-2017 (2023). Kathmandu, Nepal. 2012.

- 96. Johnson G, Bedford J, Miller N, et al. Maternal Community Health Workers during the Ebola Outbreak in Liberia. Maternal and Child Health working Paper. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), New York, 2017. Available: https://www.unicef.org/health/files/CHW_Ebola_working_paper_Liberia_29Nov2017_FINAL.pdf