Abstract

Background

Anemia is the leading public health problem among pregnant women worldwide. Iron-Folic Acid (IFA) supplementation is the strategy to control pregnancy induced anemia, but its adherence status was not well studied.

Objective

The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of IFA adherence and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care at Denbiya district health centers.

Methods

Cross -sectional study design was conducted in Denbiya district health centers from April 2 to May 27, 2016. A total of 395 study participants were enrolled in the study. Systematic random sampling was used to select study participants. Data were collected using the interviewer-administered technique. Adherence to IFA supplementation was assessed by the pills count method. A logistic regression model was used.

Results

The study revealed that the prevalence of good adherence towards IFA supplementation among Antenatal care (ANC) service users’ at Denbiya district health centers were found to be 28.01% [95% CI, 24.01, 35.9]. Attending secondary school and above [Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) = 3.44, 95% CI: 1.09, 10.92], having two ANC visits [AOR = 2.53, 95% CI: 1.34, 4.76] and three and above ANC visits [AOR = 4.14, 95% CI: 2.14, 8.01] were significantly associated with good adherence of IFA supplementation. To the contrary, husband education status; secondary school and above reduced the odds of good adherence by 77% compared to illiterates to IFA supplementation [AOR = 0.23, 95% CI: 0.07, 0.72].

Conclusion

The prevalence of good adherence among pregnant women towards IFA supplementation was low. Mothers’ education and having two or more ANC visits were positively associated with good adherence towards IFA supplementation.

Keywords: Iron, Folic acid, Adherence, Compliance, Pregnant women, Antenatal care

Background

Anemia is the leading public health problem worldwide. Globally, the estimated prevalence of anemia was 24.8% in the general population; 47.4% in preschool-aged children, 41.8% in pregnant women, and 30.2% in non-pregnant women [1].

Pregnant women are at high risk of iron deficiency anemia due to increased nutrient requirements. As a result, 38.2% of pregnant women suffered from anemia worldwide [2]. Inadequate dietary intake, previous pregnancy, normal recurrent loss of iron from menstrual blood, morning sickness, and previous anemia history were the risk factors of anemia for pregnant women [3]. Prophylaxis IFA supplementation is an important option to prevent iron deficiency anemia in pregnant women [4]. IFA supplementation is part of Antenatal Care (ANC) to reduce the risk of low birth weight, maternal anemia, and iron deficiency [5]. In South India, the IFA adherence rate was 64.7%. The effectiveness of IFA supplementation depends on the adherence or compliance of pregnant women. In Muntinlupa, Philippine, the compliance rate of pregnant mothers to IFA is 54% [6]. In Brazil, the IFA adherence rate of pregnant women is 82%, but its adherence rate decreased as the frequency of doses increases [7]. Forget fullness, vomiting, nausea, heartburn, and diarrheas were the main reasons of drug interruption [8–10]. In Mozambique, the iron sulfate adherence was 79% for having two or more visits, 53% for those having adequate prenatal care, and 67% for those who complete their intake of IFA tablets [11]. In Tigray, Ethiopia the rate of adherence to IFA supplementation was 37.2% [12] and Addis Ababa 60% [13]. The presence of iron sulfate side effects such as constipation, darkened or green stools, diarrhea, loss of appetite, nausea, stomach cramp, and vomiting decrease the IFA adherence rate in pregnant women [7, 14]. Conducting research on IFA adherence for pregnant women provides a double benefit for the mother and the fetus [15]. Iron-folic acid supplementation is one of a strategy made to prevent anemia for pregnant women [4, 5], but there is no evidence on the adherence of IFA supplementation among pregnant women in the study area. Therefore, the present study determines the adherence to IFA supplementation among pregnant women.

Methods

Study setting and period

Cross-sectional study was conducted at Dembiya district health centers (Guramba, Kolladiba, Robit, and Chuahit) among pregnant women from April 2 to May 27, 2016. These health centers are found in the North Gondar zone of Amhara regional state of Ethiopia. Dembia district is situated around 772 Km away from Addis Ababa (the capital city of Ethiopia). These health centers serve for more than half a million of people in the town and rural areas. At the moment there were around 789 pregnant women in all of the health centers.

Sample size determination and sampling procedures

All pregnant women who had ANC follow up in the Denbiya district health centers were a source of population. Pregnant women who received IFA supplementation for at least one month prior to data collection were included in the study. The sample size was determined using a single population proportion formula through the EPi Info Stat Calc Program with the assumption of 95% level of confidence, 5% marginal error, and taking the prevalence of IFA adherence in Tigray, Ethiopia (37.2%) [12]. After computing the calculation, the sample size was 359. Finally, considering a10% non-response rates, the final sample size was 395. The sampling frame was developed according to the order of the pregnant women attending the ANC clinic. A systematic random sampling technique was used to select study participants by calculating a sampling interval as the total population to sample size. Then each participant was selected every two-person pattern.

Data collection tools and procedures

The structured interviewer-administered questionnaire which is composed of socio-demographic and obstetric history were used to collect the data [12, 13]. Besides, data on adherence of IFA was collected using pills count methods. Data were collected by three midwives (one supervisor and two data collectors). To maintain the quality of the data, the questionnaire was pretested and half day training was given to data collectors and supervisors. The questionnaire first developed in English and translated to Amharic local language to collect data then back to English for analysis to maintain its consistency.

Operational definitions

Antenatal care visit

Antenatal care provided by skilled health personnel (doctor, nurse or midwife) during pregnancy.

Trimester

The number of weeks during pregnancy (1st, 1-12 weeks, 2nd, 13–26 weeks, and 3rd, 27-40 weeks).

Gravidity

The number of pregnancy whatever the outcome.

Parity

The number of live births among pregnancy.

IFA adherence

Good Adherence was considered as a pregnant woman who took ≥65% of the total prescribed IFA supplementation per month; whereas the opposite is true for non-adherence [12].

Data processing and analysis

Data were entered into the EPi Info Version seven and exported to SPSS Version twenty for analysis. Descriptive statistics, such as means, medians, frequencies, and percentages were calculated. All variables having p-value ≤0.2 in bivariate analysis entered into the multivariate logistic regression model to identify the effect of the independent variable on the outcome variables. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and AOR with a 95% CI was calculated to see the presence of associations. Model fitness was checked by using Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit test.

Result

Socio-demographic characteristics of pregnant women

A total of 395 pregnant women were enrolled in the study with a response rate of 96.7%. More than one-third (43.2%) of the pregnant women were found to be in the age range of 25-31 years. Majorities (96.6%) were married, and 84% were housewife. Nearly two-thirds (59.2%) of pregnant women were illiterate (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio demographic characteristics of pregnant women attending ANC service at Denbiya district health centers, Northwest Ethiopia, 2016 (n = 382)

| Variables | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||

| 18–24 | 79 | 20.7 |

| 25–31 | 165 | 43.2 |

| 32–42 | 138 | 36.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 369 | 96.6 |

| Unmarried | 13 | 3.4 |

| Religion | ||

| Orthodox | 357 | 93.5 |

| Muslim | 23 | 6 |

| Protestant | 2 | 0.5 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Amhara | 372 | 97.4 |

| Tigray | 10 | 2.6 |

| Mother’s education status | ||

| Illiterate | 226 | 59.2 |

| Primary school | 83 | 21.7 |

| Secondary school and above | 73 | 19.1 |

| Husband education status | ||

| Illiterate | 209 | 54.7 |

| Primary school | 97 | 25.4 |

| Secondary school and above | 76 | 19.9 |

| Occupation | ||

| Housewife | 321 | 84 |

| Government employee | 23 | 6 |

| Private employee | 11 | 2.9 |

| Merchant | 27 | 7.1 |

| Monthly household income in Ethiopia | ||

| Birr (EB) | ||

| < 1000 | 115 | 30.1 |

| 1000–2000 | 114 | 29.8 |

| 2001–3000 | 95 | 24.9 |

| > 3000 | 58 | 15.2 |

Obstetric and health-related characteristics of pregnant women

One hundred fifty-four (40.3%) of pregnant mothers had two ANC visits. Nearly two-thirds (62%) were multigravida, and (57.3%) were ≤ two trimesters (Table 2).

Table 2.

Obstetric characteristics of pregnant women attending ANC service at Denbiya district health centers, Northwest Ethiopia, 2016 (n = 382)

| Variables | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of ANC visit | |||

| One times | 119 | 31.2 | |

| two times | 154 | 40.3 | |

| Three and above | 109 | 28.5 | |

| Parity | |||

| Nulliparous | 58 | 15.2 | |

| Primiparous | 84 | 22 | |

| Multiparous | 240 | 62 | |

| Gravidity | |||

| Primigravida | 53 | 13.9 | |

| Multigravida | 329 | 86.1 | |

| Trimester | |||

| ≤ two | 219 | 57.3 | |

| three | 163 | 42.7 | |

| Acute illness | |||

| Yes | 66 | 17.3 | |

| No | 316 | 82.7 | |

Prevalence of IFA adherence among pregnant women

The prevalence of good adherence among pregnant women towards IFA supplementation was found to be 28.01% [95% CI, 24.01, 35.9]. The mean (SD) IFA consumption among pregnant women was 1.08 ± 0.24 pills.

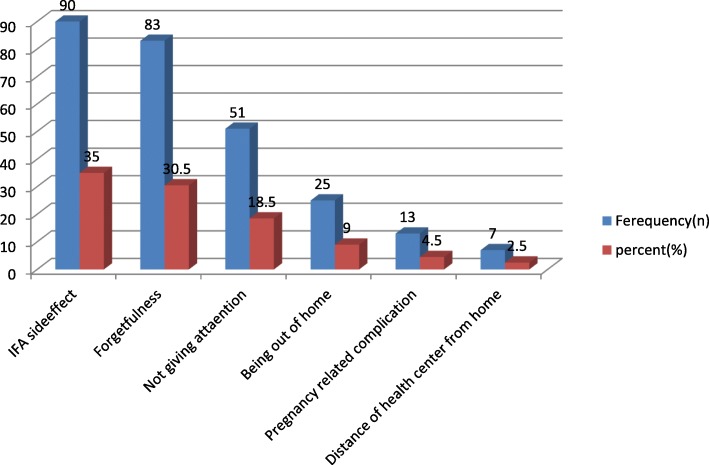

Gastrointestinal discomfort due to side effect 35%, forgetting 30.5%, and not giving attention 18.5% are the reasons of non-adherence to IFA supplementation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Reasons for IFA non-adherence among pregnant women attending ANC service at Denbiya district health centers, Northwest Ethiopia, 2016

Factors associated with IFA adherence among pregnant women

In both the bivariate and multivariable analysis; maternal education and numbers of ANC visits were significantly associated with good adherence to IFA supplementation. Education status; secondary school and above [AOR = 3.44, 95% CI: 1.09, 10.92], and antenatal care visits; two ANC visit [AOR = 2.53, 95% CI: 1.34, 4.76], and three and above ANC visit [AOR = 4.14, 95% CI: 2.14, 8.01] were significantly associated with good adherence to IFA supplementation. Whereas husband education status; secondary school and above reduced the odds of good adherence by 77% compared to illiterates to IFA supplementation [AOR = 0.23, 95% CI: 0.07, 0.72] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with IFA adherence among pregnant women attending ANC service at Denbiya district health centers, Northwest Ethiopia, 2016 (n = 382)

| Variables | Crude OR | Adjusted OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherence status | 95% CI | 95% CI | ||

| Good | Poor | |||

| Mother ‘s education status | ||||

| Illiterate | 63 | 163 | 1 | 1 |

| Primary school | 24 | 59 | 1.05 (0.603,1.836) | 1.76 (0.88,3.50) |

| Secondary school and | 20 | 53 | 0.98 (0.54,1.76) | 3.44 (1.09,10.92)* |

| above | ||||

| Husband education status | ||||

| Illiterate | 63 | 146 | 1 | 1 |

| Primary school | 26 | 71 | 0.85 (0.50,1.45) | 0.60 (0.31,1.16) |

| Secondary school and | 18 | 58 | 0.72 (0.39,1.32) | 0.23 (0.07,0.72)* |

| above | ||||

| Number of ANC visit | ||||

| One times | 19 | 100 | 1 | 1 |

| two times | 45 | 109 | 2.17 (1.19,3.96) | 2.527 (1.341,4.761)* |

| Three and above | 43 | 66 | 3.43 (1.84,6.39) | 4.14 (2.14,8.01)* |

| Trimester | ||||

| ≤ two | 50 | 169 | 1 | 1 |

| three | 57 | 106 | 1.82 (1.16,2.85) | 1.16 (0.62,2.17) |

*p-value < 0.05

Discussion

The prevalence of good adherence among pregnant women towards IFA supplementation was found to be 28.01% [95% CI, 24.01, 35.9]. The finding of the current study is higher than studies conducted in Afar, Ethiopia (22.9%) [12] and Mecha, Ethiopia (20.4%) [16]. To the contrary, the finding of this study is much lower than studies conducted from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (60%) [13], Mizan Tepi, Ethiopia (70.6%) [17], Eritrea (64.7%) [18], Enugu, Southeastern Nigeria (64.5%) [19], Senegal (69%) [20], Kathmandu, Nepal (73.2%) [21], and Iraq (51.47%) [22]. The possible discrepancy might be due to variations in socio-demographic characteristics, data collection tools and the cut point of adherence status, and period of data collection.

The current study revealed that maternal education is an independent factor of good adherence to IFA supplementation. Pregnant mothers who had secondary education and above were 3.44 times more likely [AOR = 3.44, 95% CI; 1.09, 10.92] to have good adherence towards IFA supplementation compared to those had no secondary education and above. This finding is supported by studies from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia [13], Asela, Ethiopia [10], West Iran [23], and West Bengal, India [24]. This might be due to education is more likely to enhance pregnant women awareness on the outcome of IFD deficiency and ways to overcome these deficiencies from different sources including advice from health workers. This implies that educated women have a greater ability to stick to health care inputs such as IFA which offer better for fetal growth and development; and care for both the infant and the mother [25, 26].

Numbers of ANC visits are found to be the determinant factors of good adherence towards IFA supplementation. Pregnant mothers who had two ANC visits are 2.53 times more likely [AOR = 2.527, 95% CI; 1.341, 4.761] to have good adherence towards IFA supplementation compared to those who had one ANC visit. Similarly, Pregnant mothers who had three and above ANC visits are 4.14 times more likely [AOR = 4.14, 95% CI; 2.14, 8.01] to have good adherence towards IFA supplementation compared to those who had one ANC visit. This finding is supported by studies Eritrea [18], Kiambu, Kenya [27], and Northwest Ethiopia [28]. This is the fact that ANC is the vital route for the delivery of iron supplementation and reinforcement of adherence. This suggests increase ANC visits are a good opportunity to increase contact between pregnant women and health professionals. Thus, health professionals can disseminate key information/messages, especially the benefits of IFA supplementation.

Husband education status; secondary school and above reduced the odds of good adherence by 77% compared to illiterates [AOR = 0.23, 95% CI: 0.07, 0.72]. This might be due to the misunderstandings/misperception of educated husbands on side effects and may think IFA has a negative adverse effect on the fetus like the other unsafe drugs. This suggests that educated husbands may affect the autonomy of the mothers to take iron-folic acid supplementation. The relationship between IFA adherence and husbands’ education needs further investigation, triangulated with a quantitative and qualitative study.

Limitations

The study did not assess the level of adherence and some other factors like knowledge of anemia. Further studies are recommended with all the necessary variables with strong study designs triangulated with qualitative methods.

Conclusions

The prevalence of good adherence among pregnant women towards IFA supplementation is low. Mothers’ education and two or more ANC visits are positively associated with IFA adherence. The IFA side effect was the main reason for pregnant women not taking regularly. Hence, promoting the benefits of frequent ANC, provide information about the benefits of IFA, side effect, and the effect of micro-nutrient deficiency should be intensified. Health professionals at the health facility should sensitize pregnant women on the need to continuously take the supplements throughout pregnancy. Local health extension workers, husbands and generally community should also be strongly involved in the promotion of prenatal iron supplementation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the study participant and data collectors for their collaboration during the data collection. We would also like to thank the University of Gondar for providing ethical clearance.

Abbreviations

- ANC

Antenatal care

- AOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI

Confidence Interval

- COR

Crude Odds Ratio

- IFA

Iron-folic acid

Authors’ contributions

MT carried out the IFA adherence study, participated in the sequence alignment and drafted the manuscript. MW carried out IFA adherence. AA participated in the sequence alignment. TD participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. AW conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusion of this article are included in this article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the College of Medicine and Health Sciences Research and Ethical review committee of the University of Gondar. A formal letter indicating the ethical approval was obtained and submitted to Denbiya district woreda health offices and health centers coordinator. Consent was obtained from each study participant. Personal identifiers like name and phone number were not used.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Missa Tarekegn, Email: missatarekegn@gmail.com.

Mamo Wubshet, Email: mamo_wubshet@yahoo.com.

Azeb Atenafu, Email: bemnyaz@gmail.com.

Terefe Derso, Email: dersotere@gmail.com.

Abere Woretaw, Email: wabere@ymail.com.

References

- 1.McLean E, Cogswell M, Egli I, Wojdyla D, De Benoist B. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia, WHO vitamin and mineral nutrition information system, 1993–2005. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(4):444–454. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO . The global prevalence of anaemia in 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. p. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goddard AF, James MW, McIntyre AS, Scott BB. Guidelines for the management of iron deficiency anaemia. Gut. 2011;60(10):1309–1316. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.228874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osungbade Kayode O., Oladunjoye Adeolu O. Preventive Treatments of Iron Deficiency Anaemia in Pregnancy: A Review of Their Effectiveness and Implications for Health System Strengthening. Journal of Pregnancy. 2012;2012:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2012/454601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. Daily iron and folic acid supplementation in pregnant women. Geneva: World Health Organization guideline; 2012. [PubMed]

- 6.Lutsey PL, Dawe D, Villate E, Valencia S, Lopez O. Iron supplementation compliance among pregnant women in Bicol, Philippines. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(1):76–82. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AId S, Batista Filho M, Bresani CC, Ferreira LOC, Figueiroa JN. Adherence and side effects of three ferrous sulfate treatment regimens on anemic pregnant women in clinical trials. Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25(6):1225–1233. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2009000600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gebremedhin S, Samuel A, Mamo G, Moges T, Assefa T. Coverage, compliance and factors associated with utilization of iron supplementation during pregnancy in eight rural districts of Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):607. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mithra P, Unnikrishnan B, Rekha T, Nithin K, Mohan K, Kulkarni V, et al. Compliance with iron-folic acid (IFA) therapy among pregnant women in an urban area of South India. Afr Health Sci. 2013;13(4):880–885. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v13i4.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niguse W, Murugan R. Determinants of adherence to Iron folic acid supplementation among pregnant women attending antenatal Clinic in Asella Town. Ethiopia. .

- 11.Nwaru BI, Salomé G, Abacassamo F, Augusto O, Cliff J, Sousa C, et al. Adherence in a pragmatic randomized controlled trial on prophylactic iron supplementation during pregnancy in Maputo, Mozambique. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(6):1127–1134. doi: 10.1017/S1368980014001359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gebre Abel. Assessment of Factors Associated with Adherence to Iron-Folic Acid Supplementation Among Urban and Rural Pregnant Women in North Western Zone of Tigray, Ethiopia: Comparative Study. International Journal of Nutrition and Food Sciences. 2015;4(2):161. doi: 10.11648/j.ijnfs.20150402.16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gebreamlak Bisratemariam, Dadi Abel Fekadu, Atnafu Azeb. High Adherence to Iron/Folic Acid Supplementation during Pregnancy Time among Antenatal and Postnatal Care Attendant Mothers in Governmental Health Centers in Akaki Kality Sub City, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Hierarchical Negative Binomial Poisson Regression. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0169415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tolkien Z, Stecher L, Mander AP, Pereira DI, Powell JJ. Ferrous sulfate supplementation causes significant gastrointestinal side-effects in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0117383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peña-Rosas JP, De-Regil LM, Dowswell T, Viteri FE. Daily oral iron supplementation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD004736. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004736.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taye B, Abeje G, Mekonen A. Factors associated with compliance of prenatal iron folate supplementation among women in Mecha district, Western Amhara: a cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;20(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.SSaS N. Adherence and associated factors of prenatal Iron folic acid supplementation among pregnant women who attend ante Natal Care in Health Facility at Mizan-Aman town, bench Maji zone, Ethiopia, 2015. J Pregnancy Child Health. 2017;4(3).

- 18.Getachew M, Abay M, Zelalem H, Gebremedhin T, Grum T, Bayray A. Magnitude and factors associated with adherence to Iron-folic acid supplementation among pregnant women in Eritrean refugee camps, northern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1716-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ugwu E, Olibe A, Obi S, Ugwu A. Determinants of compliance to iron supplementation among pregnant women in Enugu, southeastern Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2014;17(5):608–612. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.141427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seck BC, Jackson RT. Determinants of compliance with iron supplementation among pregnant women in Senegal. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(6):596–605. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ratanasiri T, Koju R. Effect of knowledge and perception on adherence to iron and folate supplementation during pregnancy in Kathmandu, Nepal. J Med Assoc Thail. 2014;97(10):S67–S74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdul-Rahman AM. Adherence to folic acid supplements during Peri-Conceptional period. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2015;4(7):215–223. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sina Siabani MMA, Maryam Babakhani, Fateme Rezaei, and Soraya Siabani. Determinants of adherence to Iron and folate supplementation among pregnant women in West Iran: a population based cross-sectional study. Qual Prim Care 2017;25(3):157–163. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Pal PP, Sharma S, Sarkar TK, Mitra P. Iron and folic acid consumption by the ante-natal mothers in a rural area of India in 2010. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4(10):1213. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raut BK, Jha MK, Shrestha A, Sah A, Sapkota A, Byanju S, et al. Prevalence of iron deficiency anemia among pregnant women before iron supplementation in Kathmandu university hospital/Dhulikhel hospital. J Gynecol Obstet. 2014;2(4):54–58. doi: 10.11648/j.jgo.20140204.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agrawal S, Fledderjohann J, Vellakkal S, Stuckler D. Adequately diversified dietary intake and iron and folic acid supplementation during pregnancy is associated with reduced occurrence of symptoms suggestive of pre-eclampsia or eclampsia in Indian women. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dinga LA. Factors associated with adherence to iron/folate supplementation among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic at Thika District Hospital in Kiambu County. Kenya: University of Nairobi; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birhanu TM, Birarra MK, Mekonnen FA. Compliance to iron and folic acid supplementation in pregnancy, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):345. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3433-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusion of this article are included in this article.