Abstract

Introduction:

Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is a well-established technique for evaluation of salivary gland lesions, but because of the heterogenicity and morphological overlap between spectrum of lesion, there are a few challenges in its wide use. Recently, “The Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology” (MSRSGC) was introduced, providing guide for diagnosis and management according to the risk of malignancy (ROM) in different categories. The current study was conducted retrospectively to reclassify the salivary gland lesions from previous diagnosis and to evaluate the ROM in different categories.

Material and Methods:

Clinical data, FNAC specimen, histological, and clinical follow-up of cases were retrieved, cytological features were re-evaluated, and cases were reclassified as follows: Category 1: Non-diagnostic (ND); Category 2: Non-neoplastic (NN); Category 3: Atypia of undetermined significance (AUS); Category 4a: Neoplasm: benign (NB), Category 4b: Neoplasm: salivary gland neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential (SUMP); Category 5: suspicious of malignancy (SM); and Category 6: Malignant (M).

Result:

Total 293 cases were evaluated cytologically, and histological follow-up was available in 172 cases. The distribution of cases into different categories was as follows ND (6.1%), NN (38.2%), AUS (2.7%), NB (33.4%), SUMP (2.0%), SM (2.4%), and M (15%). Overall, ROM reported were 25%, 5%, 20%, 4.4%, 33.3%, 85.7%, and 97.5%, respectively for each category. Overall, sensitivity was 83.33%, specificity was 98.31%, positive predictive value was 95.74%, and negative predictive value was 92.80%.

Conclusion:

MSRSGC is a recently proposed six category scheme, which places salivary gland FNAC into well-defined categories that limit the possibilities of false negative and false positive cases.

Keywords: Fine-needle aspiration cytology, risk of malignancy, salivary gland lesions, the Milan system

INTRODUCTION

Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) of salivary gland is used world-wide for the diagnosis and management of salivary gland tumors. It provides a minimally invasive, safe, cost-effective, and accurate technique that is extremely useful in identifying a substantial subset of salivary gland nodules as benign and thus reduces unnecessary invasive surgical procedure in patients with benign diseases. In addition, it guides the further management strategy.[1,2,3,4] Many studies have reported excellent sensitivity and specificity of FNAC to differentiate neoplastic vs. non-neoplastic lesions as well as benign and malignant neoplasms; among different studies, the sensitivity of FNAC ranges from 86% to 100%, and specificity ranges between 90%–100%.[5,6,7,8,9,10] Apart from this, FNAC is an useful tool to differentiate between primary vs. metastatic lesions specially head and neck malignancies and thus helping in deciding the treatment plan.[11]

Despite being an useful sensitive and specific tool in the armamentarium of cytopathologists, there are a few challenges for salivary gland FNAC diagnosis, such as diversity and heterogenicity of salivary gland tumors, morphological overlap between different malignant tumors, and even between benign and malignant tumors.[12,13,14,15]

When FNAC is used to subclassify the neoplasm, the accuracy ranges widely from 48% to 94% in different studies.[1,6,13,16] The presence of basaloid cell component, oncocytoid changes, squamous metaplasia, and cystic component are few cytomorphological features that make FNAC a diagnostic challenge. There are many studies proposing use of morphological pattern based analysis to develop a risk stratification approach for classification of salivary gland neoplasm and providing risk of malignancy (ROM) and to guide for further ancillary test and management plan.[3,17,18] However, these studies have a wide variation of ROM in different categories ranging from 6% to 100%, thus lacking a consensus approach.[17,19,20]

Other major drawback is the terminology of reporting salivary FNAC, which varies markedly. Various reporting formats have been used varying from two tired scheme to six or even more.[16,21] Although some have tried to diagnose according to histological category, other have tried terminology such as atypical, suspicious, and malignant.[17,22]

Such diverse classification made it difficult for the treating clinician to interpret the report and decide the further management according to ROM, so to address a standard terminology for reporting salivary gland cytopathology. The American Society of Cytopathology and International Academy of Cytology recently proposed a tiered international classification scheme called the “Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology” (MSRSGC), providing guide for clinical management according to ROM in different categories.[23,24]

The MSRSGC is a six tier classification providing a standardized terminology and ROM for each category and thus avoiding the ambiguity often seen in FNAC interpretation. [Table 1]

Table 1.

The Milan system for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology: Implied risk of malignancy and recommended clinical management

| Diagnostic category | Risk of malignancy (%) | Management |

|---|---|---|

| I. Non-diagnostic | 25 | Clinical and radiologic correlation/repeat FNAC |

| II. Non-neoplastic | 10 | Clinical follow-up and radiological correlation |

| III. Atypia of undetermined significance (AUS) | 20 | Repeat FNAC or surgery |

| IV. Neoplasm | ||

| Neoplasm: Benign | <5 | Surgery or clinical follow-up |

| Neoplasm: Salivary gland neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential (SUMP) | 35 | Surgery |

| V. Suspicious for malignancy (SM) | 60 | Surgery |

| VI. Malignant | 90 | Surgery |

The current study was conducted retrospectively to reclassify the salivary gland lesions from previous FNAC diagnosis and to evaluate the ROM indifferent categories.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical data of the cases and FNAC specimen from salivary gland lesions were retrieved from the department of pathology from January 2013 to December 2017, and the salivary gland lesions were reclassified by using MSRSGC categories. The histological reports and clinical follow-up, wherever available were compared.

Salivary gland swelling both major and minor were aspirated through a direct percutaneous or intraoral route with 22 or 23 gauze needle with or without ultrasound guidance wherever needed. The smears were aspirated by trained cytopathologists 2–3 times randomly in different areas, and smears were prepared and stained with May-Grunwald-Giemsa stain, H and E stain in all cases and occasionally with Pap stain also.

The cytological features were evaluated, and then cases were reclassified according to MSRSGC as follows:

Category 1: Non-diagnostic (ND)

Category 2: Non-neoplastic (NN)

Category 3: Atypia of undetermined significance (AUS)

Category 4a: Neoplasm: Benign (NB)

Category 4b: Neoplasm: Salivary gland neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential (SUMP)

Category 5: Suspicious of malignancy (SM)

Category 6: Malignant (M).

Histopathological data wherever available were retrieved, histological diagnosis was considered as gold standard, and the ROM was calculated for each category in these cases.

RESULTS

The FNAC distribution of 293 cases according to age, sex, and site of involvement is shown in Table 2. Males were slightly more affected than female, 154 vs. 139 the ratio being 1.1: 1. Largest number of cases were seen in age group 21 to 40 year (46.1%) followed by 41–60 year age group (27%). Parotid gland was involved in 57.7% cases followed by submandibular gland in 27.3% with minor salivary gland involved in 15% of cases.

Table 2.

Distribution of cases according to age, sex, and site of involvement

| Parameter | No of cases |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 154 (52.6%) |

| Female | 139 (47.4%) |

| Age (years) | |

| <20 | 40 (13.6%) |

| 21-40 | 135 (46.1%) |

| 41-60 | 79 (27%) |

| 61-80 | 30 (10.2%) |

| >81 | 09 (3.1%) |

| Gland involved | |

| Parotid | 169 (57.7%) |

| Submandibular | 80 (27.3%) |

| Minor salivary gland | 44 (15%) |

The FNAC distribution of cases according to MSRSGC is shown in Table 3. NN category was the largest category 38.2% followed by NB category (33.4%). M, SM, ND, AUS, and SUMP constitute 15%, 2.4%, 6.1%, 2.7%, and 2%, respectively.

Table 3.

Histological follow-up of Milan system diagnostic categories

| Category | Cat 1 | Cat 2 | Cat 3 | Cat 4a | Cat 4b | Cat 5 | Cat 6 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | 18 (6.1%) | 112 (38.2%) | 08 (2.7%) | 98 (33.4%) | 06 (2.0%) | 07 (2.4%) | 44 (15%) | 293 |

| No. of cases with histological follow-up | 04 (2.3%) | 20 (11.6%) | 05 (2.9%) | 90 (52.3%) | 06 (3.5%) | 07 (4.1%) | 40 (23.2%) | 172 (58.7%) |

| Benign: non-neoplastic | 2 (50%) | 13 (65%) | - | 01 (1.1%) | 01 (16.6%) | - | - | 17 (9.8%) |

| Benign: neoplastic | 01 (25%) | 06 (30%) | 04 (80%) | 85 (94.4%) | 03 (50%) | 01 (14.2%) | 01 (2.5%) | 101 (58.7%) |

| Malignant | 01 (25%) | 01 (5%) | 01 (20%) | 01 (4.4%) | 02 (33.3%) | 06 (85.7%) | 39 (97.5%) | 54 (31.4%) |

| Risk of malignancy | 01/04 (25%) | 01/20 (5%) | 01/05 (20%) | 04/90 (4.4%) | 02/06 (33.3%) | 06/07 (85.7%) | 39/40 (97.5%) | 54/172 (31.4%) |

Histological follow-up was available in 172 cases, and available histopathological comparison according to MSRSGC and ROM of each category is shown in Table 3. In category 1 (ND) out of 18, follow-up was available in only 4 cases, and out of these, 1 case turned out to be adenoid cystic carcinoma on histological follow-up; overall, ROM for this category reported was 25%.

In category 2 (NN), histological follow-up of 20 cases were available; out of total 112 cases, 3 cases of benign tumor were reported, which were wrongly diagnosed as category 2 (NN)- chronic sialadenitis, and 1 case of mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) was reported on histopathology, which was wrongly diagnosed as category 2 (NN) -granulomatous sialadenitis on FNAC interpretation according to MSRSGC. Overall, ROM reported for this category was 5%.

Histological follow-up of 5 out of 8 cases were available in category 3 (AUS). Three cases were reclassified as pleomorphic adenoma (PA), 1 case as basal cell adenoma (BCA), and 1 case was reclassified as adenoid cystic carcinoma (AdCC). Overall, ROM for this category was 20%.

Category 4a had histological follow-up of 90 cases out of 98 cases. Out of 75 cases diagnosed as PA on FNAC, 71 showed concordance on histological follow-up, and 4 cases reclassified into malignant category (2 cases as AdCC, 1 case as MEC, and 1 case as unclassified carcinoma). Out of 8 cases diagnosed as category benign: BCA on FNAC, 2 cases were reclassified as PA on histological follow-up. One case of Warthin's tumor on FNAC was reclassified as chronic sialadenitis on histological follow-up. Overall, ROM reported was 4.4% in this category.

Category 4b cases were those, where a specific neoplastic entity cannot be made, and out of 6 cases, 1 case was reclassified as granulomatous sialadenitis, 3 cases as PA, and 1 case as AdCC and MEC each. Overall, ROM reported was 33.3% in this category. Category 5 had histological follow-up of 7 cases, and 6 cases showed concordance with diagnosis of malignancy with ROM of 85.7%.

Category 6 is for the smears that are diagnostic for malignant lesion, and histological follow-up of 40 cases was available. Only one case was misdiagnose as malignant on FNAC, which was reported as PA on histological follow-up. Twelve cases of MEC, 13 cases of AdCC, 4 cases of lymphoma, 3 cases of carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma, 2 cases of epithelial myoepithelial carcinoma, acinic cell carcinoma, and polymorphous adenocarcinoma each, and 1 case of lymphoepithelial carcinoma were reported, and overall, ROM reported was 97.5% for this category.

DISCUSSION

FNAC is a safe, accurate, and cost-effective method for evaluation of salivary gland swelling and can help in management of the patient by providing nature of the lesion.[25,26,27]

MSRSGC is a newer system for reporting salivary gland lesions according to risk stratification with an objective to provide a better communication between clinicians and cytopathologists so as to improve overall patient management. It is an evidence based six tiered system, which provides ROM and clinical management strategies for each category.[5,10,17] It classified FNAC into six categories; ND, NN, AUS, NB, SUMP, SM, and malignant with ROM of 25%, 10%, 20%, 5%, 35%, 60%, and 90% for each category.[23] Few other studies also classify salivary gland lesion according to risk stratification and provide ROM for different category with marked variation; NN 0–67%, NN 0–20%, AUS 10%–35%, NB 0%–13%, SUMP 0%–100%, SM 0%–100%, and malignant 57%–100%.[1,5,6,10,16,17,28] The present study had also categorized salivary gland FNAC into six categories according to MSRSGC, and overall, ROM reported was 25%, 5%, 20%, 4.4%, 33.3%, 85.7%, and 97.5%, respectively for each category, and results are comparable to that provided in MSRGSC.

Category 1 cases are non-diagnostic salivary gland aspirates providing insufficient diagnostic material for an informative interpretation. There were 4 cases (6.1%) in ND category and on histological follow-up, 2 cases that were diagnosed as ND in FNAC were reclassified as chronic sialadenitis, and the presence of marked fibrosis and loss of acini might be the possible reason for the false diagnosis. One case which was diagnosed as AdCC on histology revealed marked cystic change, and acellular aspirate from cystic areas during FNAC might had led it to be classified as ND category.

Out of total 112 cases (38.2%), histological follow-up was available in 20 cases under category 2 (NN). One case which was mis-interpreted as chronic granulomatous sialadenitis was reclassified as low-grade MEC on histological follow-up. The presence of cystic change, histiocytes, and foreign body granulomatous reaction against extravasated mucin might had led to the diagnosis of NN: granulomatous sialadenitis on FNAC.

The AUS category cases are those, where a neoplastic lesion cannot be completely ruled out, and we had 8 cases (2.73%) in this category; in 5 cases, histological follow-up was available, and one case was reclassified as AdCC on histology. The presence of occasional basaloid cell with atypia might be the reason of categorization into AUS on FNAC.

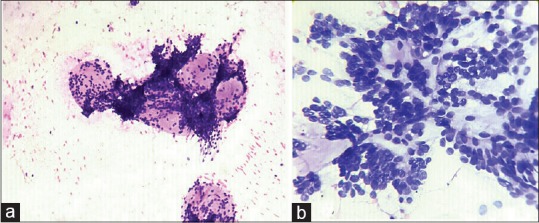

The benign category 4a had 98 cases 33.4%, and histological follow-up was available in 90 cases. PA constituted the highest percentage of all salivary gland neoplasm followed by BCA. FNAC is an effective tool to distinguish benign and malignant neoplasm with high specificity 97%–98%.[1,29] However, some time it is very difficult to differentiate between a benign neoplasm and low-grade malignant neoplasm, and in our study, 2 cases were reclassified as AdCC on histology, which were diagnosed as NB-PA on FNAC. In both cases, basaloid cell population forming occasional micro-acini around hyaline globule might had led to false diagnosis of benign category on FNAC [Figure 1a]. One case was diagnose as low-grade MEC on histology and the presence of abundant mucoid background with lack of malignant epithelial component might had led to false diagnosis of PA on cytology.

Figure 1.

(a) Abundant hyaline matrix with cells arranged around hyaline globules (Haematoxylin and eosin × 100). (b) Basaloid cells forming micro-acini around hyaline material. (Haematoxylin and eosin × 200)

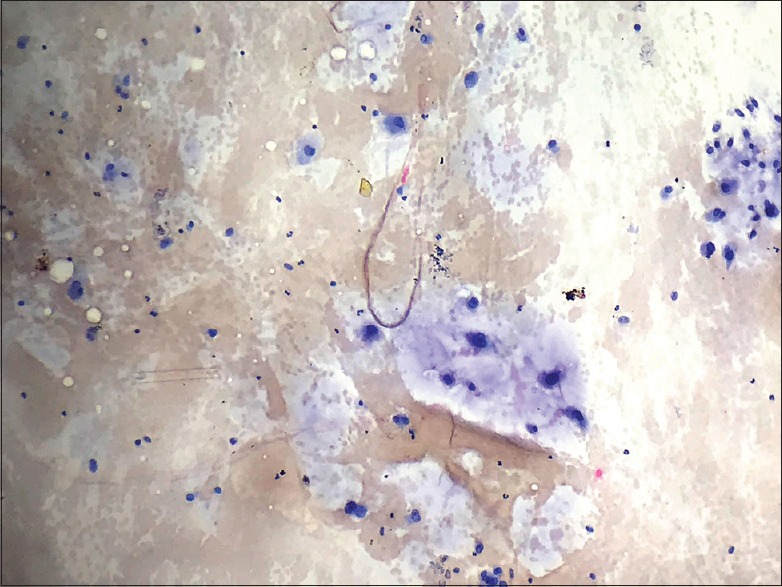

The diagnosis of SUMP is reserved for FNAC specimen, where cytological features are diagnostic of a neoplastic process, but the cytological findings cannot effectively distinguish between a benign and malignant neoplasm.[23] Out of 6 cases (2%) diagnosed as SUMP, 1 case was reclassified as AdCC on histological follow-up. On FNAC, this smear revealed a matrix forming tumor with cell arranged round hyaline globules [Figure 1b]. Other case diagnosed as MEC revealed bland epithelial cell lying against abundant myxoid background and occasional goblet cell with the myxoid matrix led to categorization into SUMP in FNAC [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Bland epithelial cells with minimal pleomorphism embedded in myxoid matrix. (Haematoxylin and eosin ×100)

Suspicious for malignancy SM category is reserved for FNAC specimens, where overall cytomorphological features are suggestive of malignancy, but not all the criteria for a specific diagnosis of malignancy are present.[23] The categories AUS, SUMP, and SM represent the intermediate diagnostic categories in Milan system.[24] The SM category was used by cytopathologists since long-time and is well-known to clinicians also.[2,13,16,25] In our study, majority of FNAC cases classified as SM had high-grade features precluding them a definite diagnosis of malignant lesion. One case that was diagnosed as SM on FNAC revealed basaloid cells admixed with marked squamous metaplasia and lacking myxoid or hyaline stroma, but on histology the case was reclassified as PA with squamous metaplasia.

Salivary gland aspirate classified as malignant reserved for cases where cytomorphological features that are diagnostic for malignancy.[23] Out of total 44 cases, (15%) histopathological follow-up of 40 cases was available, and 1 case was reclassified as PA, which was wrongly diagnosed as malignant: MEC on FNAC and presence of scattered atypical cells showing high nuclear cytoplasmic ratio lying in a myxoid background might led to false diagnosis.

Utilizing MSRSGC for diagnosing malignant lesion by FNAC, overall sensitivity was 83.33%, specificity was 98.31%, positive predictive value was 95.74%, and negative predictive value was 92.80% with an accuracy of 93.60%. The values are comparable to or even superior to many studies using conventional method for diagnosis of salivary gland lesions.[5]

MSRSGC is a recent six category scheme to classify salivary gland smears; despite being heterogenicity and morphological overlap between different salivary gland lesions, it will definitely cater the need of cytopathologists and treating clinician because beside the benefit of risk stratification and providing ROM, this system proposed a tiered scheme which places salivary gland FNAC into well-defined categories that limit the possibilities of false negative and false positive cases.

Limitation of this study is the small number of sample size, lesser number of histological follow-up, and retrospective nature of the study. Further studies including large sample size utilizing proposed management plan are required for prospective application of the study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Colella G, Cannavale R, Flamminio F, Foschini MP. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of salivary gland lesions: A systematic review. J Oral MaxillofacSurg. 2010;68:2146–53. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain R, Gupta R, Kudesia M, Singh S. Fine needle aspiration cytology in diagnosis of salivary gland lesions: A study with histologic comparison. Cytojournal. 2013;10:5. doi: 10.4103/1742-6413.109547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schindler S, Nayar R, Dutra J, Bedrossian CW. Diagnostic challenges in aspiration cytology of the salivary glands. SeminDiagnPathol. 2001;18:124–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakrabarti S, Bera M, Bhattacharya PK, Chakrabarty D, Manna AK, Pathak S, et al. Study of salivary gland lesions with fine needle aspiration cytology and histopathology along with immunohistochemistry. J Indian Med Assoc. 2010;108:833–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt RL, Hall BJ, Wilson AR, Lay field LJ. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of fine-needle aspiration cytology for parotid gland lesions. Am J ClinPathol. 2011;136:45–59. doi: 10.1309/AJCPOIE0CZNAT6SQ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu CC, Jethwa AR, Khariwala SS, Johnson J, Shin JJ. Sensitivity, specificity, and posttest probability of parotid fine-needle aspiration: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154:9–23. doi: 10.1177/0194599815607841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt RL, Narra KK, Witt BL, Factor RE. Diagnostic accuracy studies of fine-needle aspiration show wide variation in reporting of study population characteristics: Implications for external validity. Arch Pathos Lab Med. 2014;138:88–97. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0036-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song IH, Song JS, Sung CO, Rohm JL, Choi SH, Nam SY, et al. Accuracy of core needle biopsy versus fine needle aspiration cytology for diagnosing salivary gland tumors. J PatholTransl Med. 2015;49:136–43. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2015.01.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyagi R, Dey P. Diagnostic problems of salivary gland tumors. DiagnCytopathol. 2015;43:495–509. doi: 10.1002/dc.23255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei S, Layfield LJ, LiVolsi VA, Montone KT, Baloch ZW. Reporting of fine needle aspiration (FNA) specimens of salivary gland lesions: A comprehensive review. DiagnCytopathol. 2017;45:820–7. doi: 10.1002/dc.23716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pusztaszeri MP, Faquin WC. Update in salivary gland cytopathology: Recent molecular advances and diagnostic applications. SeminDiagnPathol. 2015;32:264–74. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahn S, Kim Y, Oh YL. Fine needle aspiration cytology of benign salivary gland tumors with myoepithelial cell participation: An institutional experience of 575 cases. ActaCytol. 2013;57:567–74. doi: 10.1159/000354958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes JH, Volk EE, Wilbur DC Cytopathology Resource Committee. College of American Pathologists. Pitfalls in salivary gland fine-needle aspiration cytology: Lessons from the College of American Pathologists Interlaboratory Comparison Program in Nongynecologic Cytology. Arch Pathos Lab Med. 2005;129:26–31. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-26-PISGFC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Layfield LJ, Tan P, Glasgow BJ. Fine-needle aspiration of salivary gland lesions. Comparison with frozen sections and histologic findings. Arch Pathos Lab Med. 1987;111:346–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novoa E, Gurtler N, Arnoux A, Kraft M. Diagnostic value of core needle biopsy and fine needle aspiration in salivary gland lesions. Head Neck. 2016;38:E346–52. doi: 10.1002/hed.23999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffith CC, Pai RK, Schneider F, Duvvuri U, Ferris RL, Johnson JT, et al. Salivary gland tumor fine needle aspiration cytology: A proposal for a risk stratification classification. Am J ClinPathol. 2015;143:839–53. doi: 10.1309/AJCPMII6OSD2HSJA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossi ED, Wong LQ, Bizzarro T, Petrone G, Mule A, Fadda G, et al. The impact of FNAC in the management of salivary gland lesions: Institutional experiences leading to a risk-based classification scheme. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016;124:388–96. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffith CC, Schmitt AC, Little JL, Magliocca KR. New developments in salivary gland pathology: Clinically useful ancillary testing and new potentially targetable molecular alterations. Arch Pathos Lab Med. 2017;141:381–95. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2016-0259-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arab SE, Maleki Z, Zhao HQ, Rossi ED, Bo P, Chandra A, et al. Inter-institutional variability for malignancy in “suspicious” salivary gland fine needle aspiration: A multi-institutional study [abstract] Mod Pathos. 2017;30:87A. Abstract 336. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malik A, Maleki Z, Zhao HQ, Rossi ED, Bo P, Chandra A, et al. Inter-institutional variability of “atypical” salivary gland fine needle aspiration: A multi-institutional study [abstract] Lab Invest. 2017;97:107A. Abstract 411. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H, Fundakowski C, Khurana JS, Jhala N. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of salivary gland lesions. Arch Pathos Lab Med. 2015;139:1491–7. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2015-0222-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffith CC, Schmidt AC, Pantonowitz L, Monaco SE. A pattern-based risk-stratification scheme for salivary gland cytology: A multi-institutional, interobserver variability study to determine applicability. Cancer Cytopathol. 2017;125:776–85. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faquin WC, Rossi ED, editors. Cham: Springer; 2018. The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossi ED, Faquin WC, Baloch Z, Barkan GA, Foschini MP, Pusztaszeri M, et al. The Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology: Analysis and suggestions of initial survey. Cancer Cytopathol. 2017;125:757–66. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mairembam P, Jay A, Beale T, Morley S, Vaz F, Kalavrezos N, et al. Salivary gland FNA cytology: Role as a triage tool and an approach to pitfalls in cytomorphology. Cytopathology. 2016;27:91–6. doi: 10.1111/cyt.12232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim BY, Hyeon J, Ryu G, Choi N, Baek CH, Ko YH, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of fine needle aspiration cytology for high-grade salivary gland tumors. Ann SurgOncol. 2013;20:2380–7. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2903-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pastore A, Borin M, Malagutti N, Di Laora A, Beccati D, Delazer AL, et al. Preoperative assessment of salivary gland neoplasms with fine needle aspiration cytology and echography: A retrospective analysis of 357 cases. Int J ImmunopatholPharmacol. 2013;26:965–71. doi: 10.1177/039463201302600416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohilla M, Singh P, Rajwanshi A, Gupta N, Srinivasan R, Dey P. Three-year cytohistological correlation of salivary gland FNA cytology at a tertiary centre with the application of the Milan system for risk stratification. Cancer Cytopathol. 2017;125:767–75. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klijanienko J, Vielh P. Fine-needle sampling of salivary gland lesions. II. Cytology and histology correlation of 71 cases of Warthin'stumor (adenolymphoma) DiagnCytopathol. 1997;16:221–5. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199703)16:3<221::aid-dc5>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]