Abstract

Introduction:

Urine cytology is an important screening tool of patients for urothelial carcinoma (UC) and follow-up of patients with treated disease. Ease of procurement, cost-effectiveness, and lower turnaround time are the major advantages.

Objective:

To compare current system of reporting (CSR) at our institute with The Paris System (TPS) and analyze utility of urine cytology based on TPS reporting in correlation with urine culture and histopathology.

Materials and Methods:

One-year retrospective study of 90 cases was undertaken wherein cases presenting with painless hematuria and clinically suspicious of UC were included. Urine cytology slides were reviewed and reported with TPS guidelines. These findings were correlated with histopathological diagnosis and urine culture as indicated. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS 17 software.

Results:

With TPS guidelines, 11.1% and 5.6% cases were reported as high-grade UC (HGUC) and low-grade urothelial neoplasm (LGUN), respectively. Suspicious for HGUC category included 17.8% of cases. The rate of reporting “atypical urothelial cells (AUC)” was significantly lower (11.1%) with TPS on comparison with CSR (16.7%). Histopathological correlation of positive predictive value for HGUC was better (100%) on using TPS when compared with CSR (64.3%). Among 11 cases with microbial growth on urine culture, 9.1% were reported as atypical. Sensitivity and accuracy of TPS in detecting UC were 83.3% and 86.52%, respectively. Both were higher when compared with CSR.

Conclusion:

In comparison to CSR, criteria of TPS limit the AUC category and enhance the sensitivity and accuracy of detecting HGUC. Adopting TPS for urinary cytology will ensure uniformity and accuracy of HGUC diagnosis.

Keywords: Correlation, Paris system, urine cytology, urothelial carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Urothelial carcinoma (UC) is the second most common malignancy of the urogenital system, following prostate cancers, ranking 11th in incidence in global cancer statistics.[1] Around 75% of patients present with early, 20% with higher tumor stage, and 5% with metastatic disease. Disease recurs in overall 70% of treated patients, with 30% of these patients developing metastatic disease.[2]

Urinary cytology is an inexpensive screening tool for high-risk patients for UC as well as follow-up of patients with treated disease. Cystoscopy followed by histopathological examination of biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis. However, it is an invasive procedure and may miss flat lesions especially carcinoma in situ (CIS) which is considered as a high-grade lesion. In this scenario, the ease of procurement, cost-effectiveness, and lower turnaround time add advantage to urinary cytology and make it an effective screening procedure. Nevertheless, low sensitivity toward low-grade lesions and equivocal results of urinary cytology are the major limiting factors.[3,4]

Different classification schemes have evolved with changing histopathological classifications, increased understanding of urinary cytology, and changing expectations of treating physicians. Various classification schemes proposed by Koss et al.[5] were the earliest documented attempts at classifying urinary cytology findings followed by the classification schemes by Ooms and Veldhuizen[6] and Layfield et al.[7] Recent reporting schemes include the John Hopkins template and The Paris System (TPS).[8] The latest TPS reporting format evolved as a consensus between expert cytopathologists and urologists to bring in uniformity in terminology used in reporting urinary cytology. Considering the aggressive nature of high-grade UCs (HGUCs) in comparison to low-grade urothelial neoplasms (LGUNs), the first meeting of TPS working group concluded that the new system should concentrate on the detection of HGUC. This paradigm shift became the guiding principle for this new TPS reporting.[9]

This study aims to compare the current system of reporting (CSR) at our institute with TPS and analyze the utility of urine cytology based on TPS reporting in correlation with urine culture and histopathology. This will enable us to evaluate the utility of TPS guidelines for classifying the urinary cytology observations into various categories and assess its sensitivity and accuracy in detecting HGUC which further has a bearing on clinical management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A 1-year retrospective cross-sectional observational study was undertaken in the Department of Pathology from July 2016 to June 2017. The study included urinary cytology of 90 patients who presented with painless hematuria. Institutional ethics committee approval was obtained.

Second voided morning urine samples were obtained on 3 consecutive days. Each sample was processed using cytocentrifuge (Remi R8C BL) for 10 minutes at 1500 rpm. Low cellularity samples were processed using cytospin (Sakura Cytotec) for 5 min at 500 rpm. Two smears were prepared from each sample and stained by Papanicolaou stain and May–Grunwald–Giemsa stain following standard staining procedure.[10] The slides were classified into one of the seven categories following the algorithmic approach as per TPS guidelines.[8] The diagnostic categories of TPS system were compared to the current reporting system [Table 1].

Table 1.

Categories and number of cases under each category as per the current system of reporting and the Paris system

| Current system of reporting | n (%) | The Paris system | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unsatisfactory | 1 (1.1) | Nondiagnostic/unsatisfactory | 1 (1.1) |

| Negative for malignant cells | 42 (46.7) | Negative for high-grade urothelial carcinoma | 47 (52.2) |

| Atypical cells - favor reactive change | 15 (16.7) | Atypical urothelial cells | 10 (11.1) |

| Atypical cells - suspicious for malignancy | 18 (20) | Suspicious for high-grade urothelial carcinoma | 16 (17.8) |

| Positive for malignant cells | 13 (14.4) | High-grade urothelial carcinoma | 10 (11.1) |

| Low-grade urothelial neoplasm | 5 (5.6) | ||

| Others | 1 (1.1) | Other: primary and secondary malignancies and miscellaneous lesions | 1 (1.1) |

The cytological diagnosis was correlated with histopathology and urine culture for microbial growth. The histopathological specimens were obtained by cold cup biopsy technique and transurethral resection of bladder tumor. Data were tabulated and analyzed using statistical tests for sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) using SPSS 17 software.

RESULTS

The study included 90 patients who presented with painless hematuria. Sixty-three patients (70%) were males and 27 (30%) were females with a male-to-female ratio of 2.3:1. The age ranged from 17 to 87 years (median age = 59 years). The age of patients with UC ranged from 36 to 82 years (median age = 62 years). Seven of 90 cases (7.8%) were previously treated cases of UC on follow-up for recurrence.

The comparative analysis of the diagnostic categories based on the CSR and TPS is depicted in Table 1. The histopathological diagnosis of the surgical specimens included a spectrum of benign and malignant urothelial lesions as depicted in Table 2. Our study also included two cases (2.2%) of prostatic adenocarcinoma invading the urinary bladder, one case (1.1%) each of renal cell carcinoma and cervical squamous cell carcinoma invading the urinary bladder.

Table 2.

Histopathological diagnosis of the surgical specimens

| Histopathology | n (%) |

|---|---|

| High-grade urothelial carcinoma | 21 (35) |

| Low-grade urothelial carcinoma | 15 (25) |

| PUNLMP | 1 (1.7) |

| Carcinoma in situ | 2 (3.4) |

| Other malignancies | 4 (6.7) |

| No evidence of malignancy | 8 (13.3) |

| Benign | 9 (15.0) |

| Total | 60 (100) |

In the CSR, 13 cases (14.4%) classified as “positive for malignant cells” were categorized as eight cases of HGUC and five cases of LGUN by TPS. Eighteen cases (20%) reported as “atypical cells – suspicious for malignancy” by CSR were recategorized as two cases (11.1%) of HGUC and 16 cases (88.9%) of suspicious for high-grade UC (SHGUC) by TPS. Five of 15 cases (33%) in the category “atypical urothelial cells (AUC) – favor reactive” in the CSR were reclassified as negative for high-grade UC (NHGUC) using TPS. Ten of 15 cases (67%) were categorized as AUCs by TPS.

Detection rate for “AUC” using TPS was 11.1% (versus 16.7% by CSR). On histological correlation, 4 of 10 cases (40%) were malignant (UCs) and 5 of 10 (50%) were benign and included four cases of cystitis cystica and 1 of nonspecific cystitis. One case with microbial growth on urine culture was noted. On cytohistological correlation, the rate of detection for HGUC and LGUN was 95.24% and 62.5%, respectively [Table 3].

Table 3.

Cytological and histopathological correlation

| Cytology | Histopathology | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HGUC | LGUC | PUNLMP | CIS | Others | No tumor | Benign | |

| ND | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - |

| NHGUC | 1 | 5 | 1 | - | - | 7 | 4 |

| AUC | 1 | 2 | - | - | 1 | - | 5 |

| SHGUC | 9 | 4 | - | 1 | 2 | - | |

| HGUC | 10 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| LGUN | - | 4 | - | 1 | - | - | - |

| Others | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Total | 21 | 15 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 9 |

ND: Nondiagnostic; NHGUC: Negative for high-grade urothelial carcinoma; AUC: Atypical urothelial cells; SHGUC: Suspicious for high-grade urothelial carcinoma; LGUN: Low-grade urothelial neoplasm; HGUC: High-grade urothelial carcinoma; LGUC: Low-grade urothelial carcinoma; PUNLMP: Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential; CIS: Carcinoma in situ

The sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, PPV, and NPV and accuracy of TPS in comparison to CSR are depicted in Table 4. The positive predictive percentage of HGUC for each of the diagnostic categories in TPS is shown in Table 5.

Table 4.

Comparison between current system of reporting and The Paris system (with 95% confidence interval)

| Current system of reporting | The Paris system | |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 57.50% | 83.33% |

| Specificity | 75.51% | 89.40% |

| Positive predictive value | 65.71% | 87.50% |

| Negative predictive value | 68.52% | 85.70% |

| Accuracy | 67.42% | 86.52% |

Table 5.

Correlation of cytology and histopathology with positive predictive value (for HGUC) of each category using the Paris system

| Histopathology | TPS cytology | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHGUC (n=18) | AUC (n=8) | SHGUC (n=14) | HGUC (n=10) | |

| Benign | 11 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| CIS | - | - | 1 | - |

| LGUN | 6 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| HGUC | 1 | 1 | 9 | 10 |

| PPV for HGUC, % | 5.6 | 12.5 | 64.3 | 100 |

TPS: The Paris System; CIS: Carcinoma in situ; LGUN: Low-grade urothelial neoplasm; HGUC: High-grade urothelial carcinoma; PPV: Positive predictive value; NHGUC: Negative for high-grade urothelial carcinoma; AUC: Atypical urothelial cells; SHGUC: Suspicious for high-grade urothelial carcinoma

DISCUSSION

Urine cytology is an inexpensive tool for the initial screening of patients presenting with painless hematuria. Numerous reporting systems have been used for accurate diagnosis of urothelial lesions. The recent TPS reporting of urine cytology evolved with emphasis on UCs and detection of HGUC.[8]

Among urothelial neoplasms, HGUC has more aggressive biologic behavior. Chaux et al. in a review of a large series of cases stated that tumor recurrence and progression were encountered in 36.5% and 40% cases, respectively. Metastatic rate observed was 20% and 15.3% of patients died of disseminated disease.[11]

This study evaluated TPS in urine cytology in 90 cases presenting with painless hematuria and compared with CSR. The median age of patients with UCs was 62 years and was more common in males as seen in other studies.[12,13,14,15]

In our study, by applying strict cytologic criteria of TPS, the prevalence of cases in the different diagnostic categories changed in comparison to CSR. The rate of reporting of AUC category reduced to 11.1% when compared with CSR where the rate was 16.7%. This is in accordance to other studies using TPS wherein the rate of reporting of “AUC” varies from 1.9% to 23.2%.[16,17,18,19] However, the PPV percentage of AUC category with subsequent histopathologic diagnosis of HGUC increased from nil to 12.5%.

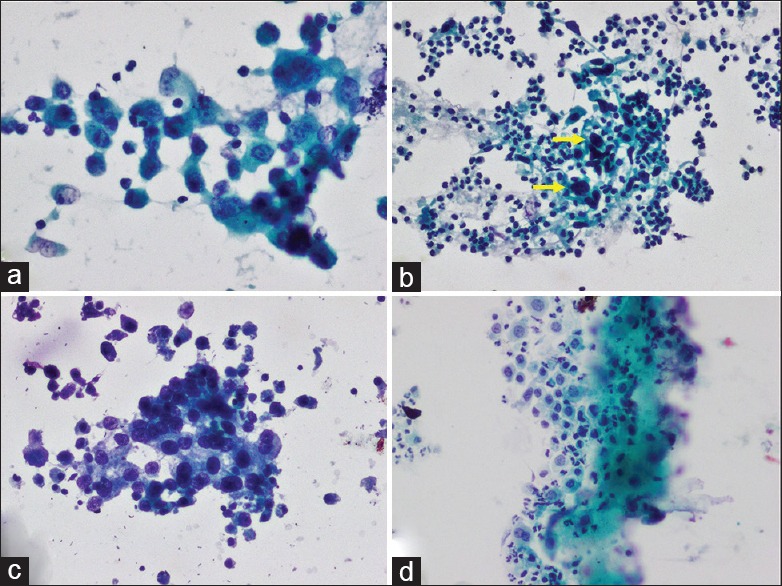

Hence, the PPV of TPS for HGUC in the AUC category was better than CSR. This is attributed to the requirement of specific criteria of atypia in TPS wherein nucleocytoplasmic ratio >0.5 along with hyperchromasia or coarse chromatin or irregular rim of chromatin is essential for diagnosis of the AUC category [Figure 1a].

Figure 1.

(a) AUC with mild atypia (Papanicolaou stain ×200). (b) SHGUC showing <10 cells with severe atypia (arrow) (Papanicolaou stain ×200). (c) HGUC showing >10 cells with severe atypia (Papanicolaou stain ×200). (d) LGUN showing fibrovascular core and mild atypia (Papanicolaou stain ×100)

In this study, 5 of 15 cases (33%) of the previously reported “AUCs – favor reactive” category were reclassified as NHGUC using TPS. Similar to this, Miki et al.[20] applied TPS on previously reported “atypical urothelial cytology” samples and reclassified 70.3% of these cases as NHGUC. The increase in NHGUC category and the reduction in AUC category are a consequence of applying the TPS criteria which clearly states that in the presence of mild atypia and absence of significant clinical, radiologic, and endoscopy findings, cases should be assigned to the NHGUC category.

Our findings also suggest that the quantitative criteria of categorizing smears with severely atypical cells present in numbers less than 5–10 cells as SHGUC and more than or equal to 10 cells as HGUC, as recommended by TPS to distinguish SHGUC and HGUC, are valid [Figure 1b and c]. This is reflected by the PPV for the detection of HGUC on histopathology which varied significantly in the two categories (64.3% and 100%, respectively). Utility of these criteria of TPS also resulted in 11.1% increase (2 of 18 cases) in the detection rate of HGUC in comparison to our CSR.

Among SHGUC cases by TPS, 56.25% were diagnosed as HGUC, 25% as low-grade UC (LGUC), 6.25% as CIS, and 12.5% as secondary tumors from prostate and renal cell carcinoma infiltrating the bladder by histopathology. Straccia et al.[16] also found that among SHGUC cases, 38.5% and 7.7% were HGUC and LGUC on histopathology, respectively.

TPS also enabled categorization of malignant cases as HGUC (11.1%) and LGUN (5.6%) which was not possible with CSR. All cases reported as HGUC on cytology using TPS were HGUC on histopathology as well. Straccia et al.[16] in their study found 82% of HGUC cases on cytology to be diagnosed as HGUC on histopathology as well.

Among the LGUN cases by TPS, four of five (80%) were diagnosed as LGUC on histopathology, while in one case a diagnosis of CIS was rendered as noted by other authors.[16,17] The presence of papillary cell fragments with fibrovascular cores with the presence of cells with evidence of mild nuclear atypia which falls short of HGUC supports a diagnosis of LGUN [Figure 1d].[8,16] The term “LGUN” used in TPS comprises LGUC, papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential, and papilloma. This is due to the absence of well-defined discriminating cytologic criteria to distinguish these lesions. Distinguishing LGUC from upper urinary tract reactive changes is difficult in view of overlapping cytomorphologic findings.[8]

The PPV percentage for HGUC was highest for the TPS cytologic category HGUC (100%) followed by SHGUC (64.3%), AUC (12.5%), and NHGUC (5.6%). This is in concordance to other studies performed using TPS wherein the risk for malignancy varies from 0% to 10% for “NHGUC” category, 50%–90% for “SHGUC,” and more than 90% for “HGUC” category.[10,12,13] The high rate of detection of HGUC on cytology is attributed to the fact that shedding of dyscohesive malignant cells in urine is greater in HGUC compared with LGUN.

The proposed utility of TPS is for detection of HGUCs. The accuracy of TPS in detecting malignancy was 86.52% and was better in comparison to CSR (67.4%). The sensitivity and specificity of TPS were 83.3% and 89.4%, respectively, when compared with CSR where sensitivity and specificity were 57.5% and 75.5%, respectively. The PPV of TPS also improved to 87.5% in comparison to 65.7 in CSR and NPV of 85.7% of TPS (CSR NPV 68.5) [Table 5]. Malviya et al.[15] in their study found a higher sensitivity of 95% and a comparable accuracy of 86.2% on using TPS. The increase in sensitivity was a result of decrease in the cases in the AUC category and increased detection rate of HGUC.

These findings clearly indicate where on instances that the cytology is reported as HGUC or SHGUC by TPS, there is very high probability of malignancy, whereas a negative result does not always imply the absence of malignancy.[8,16,17] The recommended management for SHGUC and HGUC is similar and requires further investigation to identify the source of suspicious or malignant cells.[8]

TPS facilitated the standardization of urine cytology reporting and significantly increased the sensitivity of diagnosing HGUC. This study is limited by the interpretation of cytological findings by a single pathologist and further studies addressing interobserver variability should be considered.

TPS not only addresses the issue of increasing the diagnostic yield (improves sensitivity and accuracy) of HGUC but also reduces the reporting of AUC in the presence of benign inflammatory pathology in the bladder. Hence, from this study, we conclude that urinary cytology is a valuable and inexpensive screening tool to plan further management of patients with hematuria and in those with clinical suspicion of malignancy. Towards this endeavor, TPS gives clear criteria-based guidelines for reporting urinary cytology which ensures uniformity of reporting.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan PS, Chan JB, Levin MR, Rao J. Urine cytology and adjunct markers for detection and surveillance of bladder cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2010;2:412–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes JH, Raab SS, Cohen MB. The cytologic diagnosis of low grade transitional cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;114:S59–67. doi: 10.1093/ppr/114.1.s59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chao D, Freedland SJ, Pantuck AJ, Zisman A, Belldegrun AS. Bladder cancer 2000: Molecular markers for the diagnosis of transitional cell carcinoma. Rev Urol. 2001;3:85–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koss LG, Bartels PH, Sychra JJ, Wied GL. Diagnostic cytologicsample profiles in patients with bladder cancer using TICAS system. Acta Cytol. 1978;22:392–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ooms EC, Veldhuizen RW. Cytological criteria and diagnostic terminology in urinary cytology. Cytopathology. 1993;4:51–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.1993.tb00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Layfield LJ, Elsheikh TM, Fili A, Nayar R, Shidam V. Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology. Review of the state of the art and recommendations of the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology for urinary cytology procedures and reporting: The Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology Practice Guidelines Task Force. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;30:24–30. doi: 10.1002/dc.10401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenthal DL, Wojcik EM, Kurtycz Daniel EI, editors. New York: Springer; 2016. The Paris System for Reporting Urinary Cytology. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barkan GA, Wojcik EM, Nayar R, Savic-Prince S, Quek ML, Kurtycz DFI, et al. The Paris System for reporting urinary cytology: The quest to develop a standardized terminology. Acta Cytol. 2016;60:185–97. doi: 10.1159/000446270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keebler CM, Facik M. Cytopreparatory techniques. In: Bibbo M, Wilbur DC, editors. Comprehensive Cytopathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2008. pp. 977–1003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaux A, Karram S, Miller JS, Fajardo DA, Lee TK, Miyamoto H, et al. High-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma of the urinary tract: A clinicopathologic analysis of a post – World Health Organization/International Society of Urological Pathology classification cohort from a single academic center. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:115–20. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lokeshwar VB, Habuchi T, Grossman HB, Murphy WM, Hautmann SH, Hemstreet GP, et al. Bladder tumor markers beyond cytology: International Consensus Panel on bladder tumor markers. Urology. 2005;66:35–63. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassan M, Solanki S, Kassouf W, Kanber Y, Caglar D, Auger M, et al. Impact of implementing the Paris system for reporting urine cytology in the performance of urine cytology: A Correlative study of 124 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016;146:384–90. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqw127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dev HS, Poo S, Armitage J, Wiseman O, Shah N, Al-Hayek S. Investigating upper urinary tract urothelial carcinomas: A single-centre 10-year experience. World J Urol. 2017;35:131–8. doi: 10.1007/s00345-016-1820-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malviya K, Fernandes G, Naik L, Kothari K, Agnihotri M. Utility of the Paris system in reporting urinary cytology. Acta Cytol. 2017;61:145–52. doi: 10.1159/000464270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Straccia P, Bizzarro T, Fadda G, Pierconti F. Comparison between cytospin and liquid-based cytology in urine specimens classified according to the Paris System for reporting urinary cytology. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016;124:519–23. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brimo F, Vollmer RT, Case B, Aprikian A, Kassouf W, Auger M. Accuracy of urine cytology and the significance of an atypical category. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:785–93. doi: 10.1309/AJCPPRZLG9KT9AXL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatia A, Dey P, Kakkar N, Srinivasan R, Nijhawan R. Malignant atypical cell in urine cytology: A diagnostic dilemma. Cytojournal. 2006;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1742-6413-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deshpande V, McKee GT. Analysis of atypical urine cytology in a tertiary care center. Cancer Cytopathol. 2005;105:468–75. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miki Y, Neat M, Chandra A. Application of The Paris System to atypical urine cytology samples: Correlation with histology and UroVysion FISH. Cytopathology. 2017;28:88–95. doi: 10.1111/cyt.12367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]