Abstract

Background:

Rollout of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has helped to achieve the increased life span among pediatric HIV patients. The psychosocial aspects of parents or caregivers can affect the treatment adherence in children and the disease outcome.

Aims and Objectives:

This study aims at understanding the perspectives on disclosure of HIV status, stigma, antiretroviral treatment, and compliance among caregivers of children attending ART clinic in South India and to explore the barriers to treatment-seeking behavior.

Materials and Methods:

This facility-based qualitative study was carried out among caregivers of pediatric HIV patients <15 years of age. In-depth interview was conducted on caregivers after informed consent in the absence of the child, focusing on stigma, disclosure of HIV status to children, adherence, and coping strategies followed by the parents. The complete interviews were transcribed in English, and content analysis was done to identify the emergence of codes. Interview was conducted among mothers of affected child. The disease status of the children was known only to the parents and not to the children themselves (excepting one) or siblings. Parents intended to keep it confidential for the affected children as long as possible. Nevertheless, to maintain adherence and to prevent disclosure of HIV status, mothers traveled to this ART center from very far places, medical records were hidden, and tablets were removed from the strips and said to be medicines for energy and protection.

Conclusion:

Mothers of HIV-positive children faced many difficulties to prevent the disclosure of the diagnosis from the affected children and others, which is not very conducive to adherence to the ART regimen. Effective disclosure strategies to manage this emotionally vulnerable group are an urgent need.

Keywords: Adherence, antiretroviral therapy, children, disclosure, HIV, stigma

According to the National AIDS Control Organization, the total number of people living with HIV/AIDS in India was estimated at around 21.17 lakhs in 2015, 6.7% of whom were children <15 years of age (0.14 million).[1] Through the National Paediatric HIV/AIDS Initiative, launched in 2006, nearly 1,06,824 children living with HIV/AIDS were registered in HIV care at ART centers till March 2014. Pediatric formulations of ARV drugs are available at all ART centers, and 42,015 were receiving free ART till 2014.[2]

The advent of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has contributed to a significant change in the course of the disease, and the benefits of ART treatment are well documented.[3,4,5] Rollout of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has helped to achieve the increase of life span among pediatric HIV patients.

Compliance to ART is an important predictor of progression of HIV to AIDS and death, and is a major determinant of HIV drug resistance. Barriers to treatment adherence among adults in developing countries have been described as stigma-related factors, lack of supportive environment at home and school, health service delivery factors, and patient factors.[6,7,8,9] In this context, considering the issue of stigma and discrimination by others, disclosure of HIV status to the affected children will have impact on their treatment adherence and their quality of life.[10,11,12,13]

Earlier studies conducted among HIV patients regarding stigma describe the situation of either mother disclosing her HIV status to children or spouse informing her/his HIV status to her/his husband or wife.[14,15,16] Though there exists a significant literature on the clinical features of HIV infection in the pediatric age group in India,[17,18,19,20] very few studies have explored the psychosocial aspects of the disease in children and the coping mechanisms by parents or caregivers.[21,22]

In the Indian context, parents of children living with HIV are the major source of psychosocial support and driving force to compliance related to ART. Majority of the HIV-affected children are living as orphaned children due to the premature death of parents due to HIV. Hence, majority of the HIV-affected children are under the support of caregivers in the family.

In this context, this study aims at understanding the perspectives of the caregivers on disclosure of HIV status, stigma, antiretroviral treatment, and compliance among children attending ART clinic of a tertiary care hospital and to explore the barriers to treatment-seeking behavior.

METHODS

Study setting and population

Puducherry, a union territory situated 165 km from Chennai, the capital of Tamil Nadu, has a population of 1.24 million and a HIV prevalence of 0.19%.[1] The HIV clinic at the teaching tertiary care referral hospital caters to patients from Puducherry and a wide area bordering Vellore, Cuddalore, Villupuram, and Tiruvannamalai districts of Tamil Nadu. This study was a facility-based, qualitative study carried out among caregivers of pediatric HIV patients <15 years of age attending one of the tertiary care ART centers (link ART center) in South India. In this link ART center, HIV-infected children are advised to come for follow-up every month for assessing the disease progression and to refill drugs. Because majority of the affected children were accompanied by their mother to the center, we interviewed mothers.

Study tool and procedure

Mothers or caregivers were interviewed in the absence of children to avoid inadvertent disclosure of disease state to children. Interview was conducted by two trained professionals in one of the rooms within the ART center, which ensured adequate privacy. Out of the two interviewers, one acted as a notetaker and recorded the full verbatim. In-depth interview was conducted with the help of an interview guide which focused mainly on stigma, disclosure of HIV status to children, adherence, and coping strategies followed by the parents to conceal disease state to others from emic perspectives. Whenever the interview was disrupted due to the mother becoming emotional, enough time was given for her to come back from that and emotions were mentioned by the notetaker along with verbatim. In case the mother was not able to understand, probes were given to facilitate the interview to go on without any disruption.

The study was conducted during 2013–2014 after approval from the Scientific and Institute Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from the caregivers, and confidentiality was maintained by removing the personal identifier from the transcripts. These transcripts were kept in the lockable cabins. Caregivers were recruited based on criterion sampling. The criterion was that their child had to be HIV infected and getting treatment for at least past 6 months from the date of the interview. A list of eligible children were identified from treatment registers maintained in ART center. Children from two strata, i.e., acquired infection perinatally (mother is HIV positive) and acquired infection in the later age (both parents were negative) were recruited. The number of children to be included in each stratum was restricted based on the redundancy of information obtained from interviews.

Analysis

During the interview, one of the notetakers wrote the complete verbatim. These verbatim notes were translated into English, and content analysis was done through the following procedures. Transcripts were independently reviewed by two authors by iterative process. Transcripts were reviewed twice to identify the emergence of codes. The list of phrases for deductive coding was obtained from already published literature. Codes, which were similar, were analyzed manually, categories were made, and finally themes were arrived from these categories. Participant responses were also substantiated as quotes.

RESULTS

A total of 11 caregivers of HIV-infected children were interviewed. Mean age of the caregivers was 30 ± 5 years and all were mothers of the affected children. Each interview lasted for 60–90 min. Out of 11 children, three children had their mothers on current ART and therefore were screened for HIV infection. Rest of them were detected incidentally during routine clinical case workup for diseases such as bronchiectasis, parotitis, nephritis, and meningitis. All the children were aged more than 6 years at the time of the study. Of the 11 affected children, six were males. Two children were orphans including one adopted child. As per the modified Kuppuswamy classification, all the caregivers were belonging to upper-lower to lower-middle socioeconomic class. Five caregivers of the 11 children were coming from rural area.

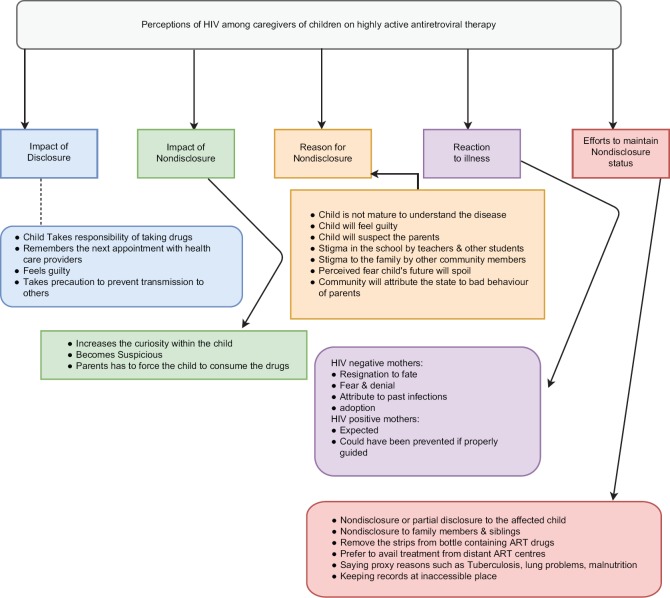

Findings of the qualitative study are presented in the form of thematic framework in Figure 1. Specific quotes which justify the themes are presented as follows.

Figure 1.

Thematic analysis framework on perceptions, challenges, and coping strategies followed by caregivers of HIV-infected child on antiretroviral therapy

Reactions to child's HIV status and perception on illness

Resignation to fate

Caregivers of children who were already infected by HIV consider this infection to be an expected one. However, there is some resentment for not having being told about the prevention of perinatal transmission during pregnancy.

One 30-year-old HIV-infected mother (mother of a 7-year-old child on ART) remarked:

“That time when she was in the womb, nobody told not to give my milk. So she got it. If we already knew we would not have given that. When I conceived for the second time I did not feed my second daughter, now she does not have the disease like us.”

Another 34-year-old HIV-infected mother (mother of a 9-year-old child) said that:

“We know this is the disease. We did not do any mistake. We are going to live 10 years less compared to others. What else can be done?”

Fear and denial

Caregivers who were not infected by HIV were emotionally more traumatized by the fear of being ostracized by others and thinking about the infected child's future.

One 28-year-old mother not infected by HIV (mother of a 10-year-old girl child on ART) expressed:

“She developed swelling in the neck for which we first visited the hospital. When the doctor told it started because of HIV we could not bear. Alas! I didn’t do any mistake. Why did God treat us like this? Till this moment, we could not console our soul. Every day by thinking this, we cry continuously. Her father tells, leave it! We have to console ourselves. I cry within myself or in front of my husband. For us, whenever we think about this, the mind could not bear. In case if something happens to us, what will happen to her fate?”

Another 38-year-old mother (mother of a 10-year-old child) said that:

“During her school days she had many injections for ulcers. That could be the only reason why she got the disease. In our family nobody has diseases. Nobody is having bad behaviour also. We are true to our God.”

Another woman adopted a child from orphanage at 3 months of his age (currently, 6 years of age). At that time of adoption, the adopted parents did not know that the child has HIV. When the child was worked up for hematuria, it was found to be due to HIV nephritis. She expressed,

“We did not do any mistake. We thought that he is only going to give meaning for our life. Every time I have to visit this hospital, I become anxious with chest pain and fatigue. Here (in the hospital), at the registration counter they will ask which OPD you have to go and who this child is. The moment I say he is my child only, they ask do I have it as well. I cry within myself. Whatever it is, still he is our beloved son. We will live for him till the end.”

Disclosure of HIV status to children and family members

Only one 12-year-old girl was aware of her HIV status (neither her parents nor her sibling is positive for HIV). The caregiver reported thus:

“She knows her illness, but she will not reveal it to others. She feels guilty on her own for her status. We are not able to help her!”

Partial disclosure to children

Except for the one child, all the other children did not know their disease status. They have been informed of having some illness but not exactly what it is. In fact, that increased their curiosity further. The following quotes expressed by various caregivers clearly exemplified it.

“During the initial time she used to ask what happened to me? Why are you giving me these many tablets? Why God has given these many tablets to me alone? What sin I have done?” (caregiver of an 11-year-old female child).

“She will go and ask her father-Dad, why is mother crying always when she gives me tablets?” (caregiver of a 7-year-old female child).

“Since she can understand English whenever the doctors are discussing during the rounds she will be curious to know what they are talking. She will keep asking so many questions with the junior doctors whenever they are in the ward” (caregiver of a 12-year-old girl).

Reasons for withholding the true diagnosis from the child

Most of the caregivers did not plan on disclosing the HIV status to the child. They felt that the child is not mature enough to understand the disease.

Factors such as fear of being ostracized by other schoolchildren, comments on parents’ bad behavior, and fear of emotional disturbance acted as barriers in disclosing the disease state with the children. Hence, they expect the child to know the disease status on their own or when they able to read and understand their case records.

“If we tell him, he will feel bad. Let him know when he is able to read himself” (mother of an 8-year-old male child).

“Better not to think about it or let her know now. She will come to know when the time comes. Even if we try to tell her, she may not understand or worse still– she may not accept it” (a HIV-infected mother).

“If we tell her, she will ask us how she acquired the disease. We won’t tell her, in case if she comes to know, we shall see to it at that time” (a HIV-infected mother).

Nondisclosure to family members

In general, the disease status was known only to the parents. Even the close relatives like grandparents were not informed regarding this. In nuclear families, it was not shared even among the siblings. Caregivers were worried about the discrimination of the affected child by other siblings in the family. Caregiver of an 11-year-old female said that “We thought of admitting her in the hostel. But now we are planning on admitting our two other children in the hostel. This way, she will always be in our care.”

One caregiver (whose other children were not having the disease) said that:

“Even her elder brother does not know about this status. He knows that illness as TB. He thinks that's why she is very lean. When she goes to her grandmother's house during her vacation, that time I will remove all the strips and put it in the bottle.”

Efforts to maintain nondisclosure of disease status to others

Parents did not want to disclose the HIV status of the child to others due to the fear of being discriminated by schoolchildren and teachers.

Specific instructions to children

Because almost all the children did not know their HIV status, caregivers had given certain instructions to the infected children to maintain the nondisclosure of HIV status to others. Caregivers had instructed the children not to show the records to anyone and not to play.

One 38-year-old mother narrated that “We have told her to be careful while going to school. In case of any injury she should not allow anybody to touch her wound and that she should clean it herself with cotton kept in her bag. In case she is not able to handle the situation, she can ask her teacher to call us.”

Stating false conditions of illnesses

Parents also took steps to keep the disease state as confidential. They stated surrogate reasons for the poor health like the child is affected by “chronic cold” or having “holes in the lungs” or “his/her liver is weak.” They also maintain that the medicines taken by their children are mainly for energy and protection.

One caregiver said, “We give tablets without the knowledge of others. If guests visit us, we give medicines to her outside the house. In case someone asks, we have instructed her to tell that these are taken for strength.”

Availing antiretroviral therapy services from center far from their residence

They do not prefer to take drugs from nearby ART centers in spite of proximity and convenience.

One mother who travels 40 km to the tertiary center to collect drugs said, “Though the nearby hospital is only three kilometres from my house, we don’t want it to be close. Others may get our treatment notebook and they will think badly. We are coming here (to the tertiary centre) so that nobody will come to know. This is only convenient for us also.”

In spite of these methods, caregivers felt that it cannot be kept confidential beyond certain point of time. Chronic nature of illness and reaction to drugs will increase the curiosity of others and thereby lead to disclosure.

“Since she is taking medicines for a long time even other people might feel suspicious. These tablets made her face to be dull and her cheeks have sunken” (mother of an 11-year-old female child).

Perception on antiretroviral drugs and compliance to treatment

Perception of the importance of antiretroviral therapy

Caregivers felt that the antiretroviral drugs are essential to expand the life span of the affected child, and they were aware of a few side effects also.

“Medicines are important and life is being sustained by it. After starting drugs, her face has changed– patches are seen on the face, dark circles surrounding eyes and gums have receded. We come two days before the medication gets over. Because of drugs we feel better, we are able to walk and eat. That's why we cannot stop the drugs-ever” (HIV-infected mother of an 11-year-old infected child).

“If these tablets are eaten regularly, her immunity will improve” (mother of a 13-year-old infected child).

Hope for new drugs

They were also aware that HIV cannot be cured by drugs. Yet, they had a hope that research will find some new drugs. The following verbatim of the in-depth interviews corroborated with these findings.

Another HIV-infected mother of a 10-year-old infected child said, “There is no belief of cure. Only we can expect some betterment in our life. Hoping for new drugs in the future that will benefit at least the next generation.”

Because the caregivers were well informed regarding the importance of drugs, they took special care not to miss any drugs.

Measures taken to ensure compliance

Mother of one HIV-infected child remarked, “When I’m going out of town I remove strips or bottles, fold the drugs in a paper and give it to my relatives at home. I call over phone and confirm whether the drugs were given. This is how I ensure compliance.”

When the child is fully informed of his/her HIV status, he/she takes keen interest in treatment. “She is regular in taking drugs. At the same time she never shows those drugs to others. She reminds us one week before itself to come to the hospital to collect drugs for the next month” (mother of an infected child who knows her HIV status).

However, among the children who were not informed regarding their status, every time, the parents have to ensure compliance to treatment and follow-up visit. “Even if we are busy in our work, she doesn’t help herself with the medicines” (mother of an infected child who is not informed of her status).

DISCUSSION

This study deals in-depth with the efforts and various measures taken by the mothers who are also caregivers of pediatric HIV patients to maintain the health of their children. We also explored their perception and examined their beliefs regarding ART as the health status of these children is totally dependent on them. In spite of the emotional turbulence that the mothers of the children in this ART center experienced, they took all care to maintain nondisclosure to children themselves, family members, and others.

In complete disclosure, the child is completely aware of his/her disease status and treatment to be followed, whereas in partial disclosure, the child knows that he/she is suffering from some illness but not as HIV. In nondisclosure, the child is completely unaware of his/her status. When the child is completely ignorant or partially aware, his/her frustration and anxiety increases which results in lack of compliance to drugs or forced to comply by the parents.

Age of the child more than 12 years, prolonged duration of illness, educational status of the child, and self-administration of drugs have facilitated the process of disclosure by the parents.[11,23,24]

In India, majority of the HIV infections are transmitted through heterosexual mode.[25] Hence, the caregivers try to conceal the disease status of children. There is a prevailing thought among caregivers that, if HIV status of a child is disclosed, others may attribute that to improper sexual behavior of the child's parents. Hence, they try not to disclose the disease state of the children in spite of themselves being HIV negative. As for the disclosure of the HIV-positive status to the child, it is a very vital issue to not only the HIV-positive mothers, but also to the HIV-negative mothers. Observations similar to our study were made by Bhattacharya et al. in another facility-based study in North India where only 17% of the 145 children were fully aware of the diagnosis. Some of the strategies adopted were similar to those adopted by the mothers in our study that of deception by means of attributing the symptoms to other conditions.[26] Other studies from Africa showed similar results.[12,23,24,27,28] In Tanzania, out of the 211 parent–/caregiver–child dyads, only 22.3% of the children had complete disclosure, the reasons for nondisclosure being children were too young to understand, disclosure may cause negative emotional consequences like discrimination, the child may not be able to keep it secret, and did not know what and how to deliver the disclosure message.[10] In Nigeria, disclosure had been done in only 13 out of the 96 children, and again the reasons given for secrecy were inability of the children to understand (63.9%), fear of disclosure to other children (41.0%), fear of disclosure to family/friends (33.7%), fear of psychological disturbance of the children (31.3%), and fear of blaming the parents (26.5%).[29] Disclosure and declaration of HIV/AIDS to the adolescents have been stated to involve different issues. Adolescents being an emotionally vulnerable age group, the way in which they will respond to their disease status is unpredictable. Sexually infected ones may find it difficult to face their family due to guilt; the perinatally affected adolescents, on the other hand, can be expected to blame their parents for their situation.[30] The 12-year-old girl in our study, who was aware of her diagnosis, also experienced guilt feelings, but the reasons for the same could not be elicited from the interview. However, disclosure had helped adherence to ART as also observed in our study.

All the mothers in our study understood the importance of the drugs in maintaining the health status of these children, and therefore, ensured compliance to the ART. We could not find studies in published literature describing the direct methods caregivers adopted to ensure compliance to ART. However, maintenance of secrecy of the diagnosis also contributes to compliance indirectly by preventing negative psychological and social fallout of HIV positivity, which is considered to be a grave disease almost universally.

Because this study was conducted among limited number of caregivers from link ART centers, findings of these results should be taken with caution before their transferability. Although the study intended to interview caregivers apart from parents of the HIV-infected children, in this study, except one, all the participants were happened to be mothers. Hence, to capture other caregivers’ perspectives, future studies should focus on institutional settings where orphaned children are cared.

The lesser disclosure of HIV and caregivers’ challenges in maintaining nondisclosure status have several programmatic implications in optimizing the adherence to ART, care, and support for HIV. As observed from our study as well as in others within and outside the country, disclosure of the HIV-positive status to the children is a very unbearable experience for the mothers/caregivers, and therefore, there is a need to assist parents and health-care providers in successfully disclosing the HIV status to infected children without adverse consequences.

To achieve zero new infection and zero discrimination, a strong thrust should be given in the areas of social support, self-empowerment, and education. Despite caregivers’ intention to maintain nondisclosure status, they are concerned regarding the transmission of HIV to other siblings, family members, and other schoolchildren through the affected child. To alleviate their fear of transmission, caregivers should be well informed regarding the myths and misconceptions and mode of transmission for HIV.

All health-care providers including the counselors in ART centers should be trained to manage the challenging concerns of caregivers in a case-to-case basis. All personnel from health system regardless of their role with direct health-care delivery to the patient should maintain utmost confidentiality of the child's status and they should not stigmatize either the affected child or the caregiver even in an indirect way. State governments should increase the access of early infant diagnosis of HIV among orphaned children. For HIV-positive children, programs should identify special adoption agencies who are trained in care and support for the HIV-affected ones.

CONCLUSION

On the whole, in the current era of increased life expectancy, effective disclosure strategies will facilitate roll-out of highly active ART to manage this emotionally vulnerable group are an urgent need.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.National AIDS Control Organization. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. India HIV Estimation 2015: Technical Report. National AIDS Control Organization [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Aids Control Organization. Annual Report. National Aids Control Organization. 2013-14. [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 11]. Available from: http://naco.gov.in/sites/default/files/NACO_English%202013-14.pdf .

- 3.Rajasekaran S, Jeyaseelan L, Ravichandran N, Gomathi C, Thara F, Chandrasekar C. Efficacy of antiretroviral therapy program in children in India: Prognostic factors and survival analysis. J Trop Pediatr. 2009;55:225–32. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmm073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sophan S, Meng CY, Pean P, Harwell J, Hutton E, Trzmielina S. Virologic and immunologic outcomes in HIV-infected Cambodian children after 18 months of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2010;41:126–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song R, Jelagat J, Dzombo D, Mwalimu M, Mandaliya K, Shikely K. Efficacy of highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infected children in Kenya. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e856–61. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arage G, Tessema GA, Kassa H. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and its associated factors among children at South Wollo Zone hospitals, Northeast Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:365. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biadgilign S, Deribew A, Amberbir A, Deribe K. Barriers and facilitators to antiretroviral medication adherence among HIV-infected paediatric patients in Ethiopia: A qualitative study. SAHARA J. 2009;6:148–54. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2009.9724943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nyogea D, Mtenga S, Henning L, Franzeck FC, Glass TR, Letang E, et al. Determinants of antiretroviral adherence among HIV positive children and teenagers in rural Tanzania: A mixed methods study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:28. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0753-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paranthaman K, Kumarasamy N, Bella D, Webster P. Factors influencing adherence to anti-retroviral treatment in children with human immunodeficiency virus in South India – Aqualitative study. AIDS Care. 2009;21:1025–31. doi: 10.1080/09540120802612857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mumburi LP, Hamel BC, Philemon RN, Kapanda GN, Msuya LJ. Factors associated with HIV-status disclosure to HIV-infected children receiving care at Kilimanjaro Christian medical centre in Moshi, Tanzania. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;18:50. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.18.50.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santamaria EK, Dolezal C, Marhefka SL, Hoffman S, Ahmed Y, Elkington K, et al. Psychosocial implications of HIV serostatus disclosure to youth with perinatally acquired HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:257–64. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abebe W, Teferra S. Disclosure of diagnosis by parents and caregivers to children infected with HIV: Prevalence associated factors and perceived barriers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. AIDS Care. 2012;24:1097–102. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.656565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, Wilson MG, Deutsch R, Raeifar E, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: A qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:848. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2197-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwelunmor J, Zungu N, Airhihenbuwa CO. Rethinking HIV/AID disclosure among women within the context of motherhood in South Africa. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1393–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel SV, Patel SN, Baxi RK, Golin CE, Mehta M, Shringarpure K, et al. HIV serostatus disclosure: Experiences and perceptions of people living with HIV/AIDS and their service providers in Gujarat, India. Ind Psychiatry J. 2012;21:130–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.119615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varga CA, Sherman GG, Jones SA. HIV-disclosure in the context of vertical transmission: HIV-positive mothers in Johannesburg, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2006;18:952–60. doi: 10.1080/09540120500356906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lala MM, Merchant RH. After 3 decades of paediatric HIV/AIDS – Where do we stand? Indian J Med Res. 2014;140:704–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lodha R, Upadhyay A, Kapoor V, Kabra SK. Clinical profile and natural history of children with HIV infection. Indian J Pediatr. 2006;73:201–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02825480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mothi SN, Karpagam S, Swamy VH, Mamatha ML, Sarvode SM. Paediatric HIV – Trends & challenges. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134:912–9. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.92636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah SR, Tullu MS, Kamat JR. Clinical profile of pediatric HIV infection from India. Arch Med Res. 2005;36:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arun S, Singh AK, Lodha R, Kabra SK. Disclosure of the HIV infection status in children. Indian J Pediatr. 2009;76:805–8. doi: 10.1007/s12098-009-0177-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas B, Nyamathi A, Swaminathan S. Impact of HIV/AIDS on mothers in Southern India: A qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:989–96. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9478-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.John-Stewart GC, Wariua G, Beima-Sofie KM, Richardson BA, Farquhar C, Maleche-Obimbo E, et al. Prevalence, perceptions, and correlates of pediatric HIV disclosure in an HIV treatment program in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2013;25:1067–76. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.749333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kallem S, Renner L, Ghebremichael M, Paintsil E. Prevalence and pattern of disclosure of HIV status in HIV-infected children in Ghana. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:1121–7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9741-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra S, Sgaier SK, Thompson LH, Moses S, Ramesh BM, Alary M, et al. HIV epidemic appraisals for assisting in the design of effective prevention programmes: Shifting the paradigm back to basics. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhattacharya M, Dubey AP, Sharma M. Patterns of diagnosis disclosure and its correlates in HIV-infected North Indian children. J Trop Pediatr. 2011;57:405–11. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmq115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hejoaka F. Care and secrecy: Being a mother of children living with HIV in Burkina Faso. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:869–76. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vreeman RC, Nyandiko WM, Ayaya SO, Walumbe EG, Marrero DG, Inui TS, et al. The perceived impact of disclosure of pediatric HIV status on pediatric antiretroviral therapy adherence, child well-being, and social relationships in a resource-limited setting. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24:639–49. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown BJ, Oladokun RE, Osinusi K, Ochigbo S, Adewole IF, Kanki P, et al. Disclosure of HIV status to infected children in a Nigerian HIV care programme. AIDS Care. 2011;23:1053–8. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.554523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naswa S, Marfatia YS. Adolescent HIV/AIDS: Issues and challenges. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2010;31:1–10. doi: 10.4103/2589-0557.68993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]