Abstract

Background:

Executive dysfunction deficit is the functionally most important cognitive deficit noted in schizophrenia. There is a dearth of Indian literature on the subject. The current study aimed at studying these executive functions in patients with schizophrenia in remission.

Methodology:

Sixty outpatients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia as per international classification of diseases-10 criteria; in remission as measured by Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale scores were divided into two groups using the personal and social performance scale. The patients with and without socio-occupational impairment formed the two groups. All patients were administered the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), Stroop test, Color Trails Test 1 and 2, Phonemic Fluency (Controlled Oral Word Association Test), and category fluency (animal names test) tests and the tower of London test to ascertain deficits in executive functions. The data obtained were subjected to statistical analysis.

Results:

The two groups were well matched. The group with socio-occupational impairment showed a lesser number of categories completed (P = 0.001), more perseverative errors (P = 0.001), and greater percentage of the same (P = 0.001) on the WCST. Statistically significant differences between both groups were observed for scores on phonemic fluency (P = 0.012) and category fluency (P = 0.049) tests as well as the Tower of London test (P = 0.021). They also showed differences on the Stroop test and Color Trail tests, but this was not statistically significant.

Conclusions:

Performance on executive function tests is significantly correlated with functional outcome. It is important that future studies explore the role of these tests as a marker of socio-occupational impairment in schizophrenia.

Keywords: Execution functions, remission, schizophrenia, socio-occupational impairment

Schizophrenia affects an approximate one person in a hundred and is a chronic, severe, and disabling disorder.[1] Multiple studies have demonstrated that patients with schizophrenia have cognitive deficits that affect cognitive and social functioning. These deficits vary in severity and hamper recovery and quality of life of the patient.[2] Executive function in schizophrenia encompasses cognitive processes which include problem-solving, ability to sustain attention, multitasking, cognitive flexibility, ability to deal with new stimuli planning, psychomotor speed, and verbal fluency.[3]

Cognitive flexibility is a trait that tends to overlap with problem-solving and is required to generate and test different approaches to problem-solving in novel situations.[4] It is tested using the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST)[5] where subjects must think of and be able to implement different matching strategies after an initially adaptive strategy is no longer resulting in correct responses.[6]

Working memory is conceptualized as a dynamic system consisting of an attention control system (the central executive) and two subsidiary storage systems, namely the articulatory or phonological loop and the visuospatial sketchpad.[7] The phonological loop and visuospatial sketchpad are typically classified under the larger domain of attention, which selects and operates strategies for maintaining and switching attention and is closely related to executive functioning.[8] The Stroop test has been used in measuring cognitive flexibility and color-word interference trial and is one of the most common measures of response inhibition.[9]

Optimal performance on the fluency task facilitates an organized search of various phonological and semantic networks to generate words.[10] The Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT) is the most extensively used verbal fluency task today.[11] The category fluency task involves asking subjects to name as many items from a single specified category they can, in a span of a minute, the most common category being animals.[12] Damage to the frontal cortex will cause impairments on any fluency measures; however, the task is also influenced by cognitive flexibility, anxiety, and poor volition.[13]

Planning may be defined as the ability to identify and organize the steps and elements needed to carry out an intention or achieve a goal.[14] The most well-known being the Tower of London has been used extensively as measures of planning.[15] The tower test is especially sensitive to damage to the prefrontal cortex and also measures other cognitive functions such as response inhibition, motor speed, and working memory.[16]

Verbal fluency tests are among the most extensively employed measures used to evaluate cognitive functioning following neurological damage, and comprise of associative exploration and retrieval of words based on phonemic or semantic criteria (phonemic and semantic fluency, respectively), usually carried out in the setting of a time constraint.[17] Patients with schizophrenia tend to do badly on word production tasks, such as the Word Fluency Test, COWAT, and Category (Animals) fluency Test compared to healthy comparison subjects, which is generally ascribed to the retrieval difficulties in schizophrenia. Greater semantic fluency deficit is a result of the disruption of the semantic store in addition to general retrieval deficits in schizophrenia.[18,19]

Perception tracking and sustained attention (ability to locate different elements within a predetermined time) are measured by the Color Trail Test 1. The Color Trail Test 2 assesses the same functions and also divided attention and sequencing (i.e., ability to achieve numeric order according to the required task because it demands sequential alternations of colors and numbers.[20]

Patients with schizophrenia demonstrate poor performance on tasks that measure planning capacity as in the Tower of London. Planning capacity involves the goal to be subdivided into subgoals, the subgoals must be placed in the correct sequence, and the single moves must be in the right order to achieve the subgoals.[21]

Neurocognitive deficits serve as a prognostic marker for future functional outcome. These functions are studied because of their close links to negative symptoms and poor functioning in the community.[22] It is important that studies compare the executive function in patients of schizophrenia with and without socio-occupational impairment. This would help target our therapy to improve executive function and in turn improve socio-occupational functioning leading to a better quality of life and recovery.[2,23] There is a dearth of Indian studies on the relationship between impaired cognitive function and functional disability of patients with schizophrenia.[24,25]

The objective of the study was to compare cognitive flexibility, working memory, psychomotor speed, planning and verbal fluency in patients with schizophrenia in remission, with and without socio-occupational impairment. It also aimed to find out if these tests can predict socio-occupational dysfunction.

METHODOLOGY

Participants

The present study was a cross-sectional study conducted in the outpatient facility of a tertiary care private psychiatric hospital. The study participants included 60 patients with schizophrenia who visited the hospital between May and December 2014. Hospital Ethics Review Board approved the study before commencement and a written informed valid consent was obtained from patients and legally acceptable relatives.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were patients of either sex between ages of 25 and 45 years with at least 7 years of formal education who satisfied the criteria of schizophrenia according to the International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD)[26] and in remission based on the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) scores.[27] The criteria used was that the score of each item on Positive, Negative and General Psychopathology Scale of PANSS must be ≤3.

The exclusion criteria were patients who were not in remission, psychiatric diagnosis other than schizophrenia and presence of chronic physical, neurological illness, cerebrovascular accident, head injury, mental retardation or active medical condition that confounded the diagnosis and interfered with the study and/or unwillingness to participate.

Demographic data

A clinical profile sheet was designed to collect sociodemographic variables of the participants and the information regarding the illness which was required for further assessment and statistical analysis.

International classification of diseases-10

The diagnosis of schizophrenia anytime during the longitudinal course of illness in the participants was made using ICD-10 criteria.

Scales used in the study

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale – It is a 30-item inventory scale and used for measuring symptom severity in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia symptoms across three subscales: Positive symptoms (items P1–P7), negative symptoms (items N1–N7), and general psychopathology symptoms (items G1–G16) are present. Each item is scored on a scale ranging from 1 (absent) to 7 (extreme). A higher score represents greater severity. The PANSS was specifically developed to assess individuals with schizophrenia and is widely used in research settings. It is shown to have a good reliability, criterion validity, and construct validity[27,28]

Personal and Social Performance (PSP) Scale – It is a 100-point single-item rating scale, subdivided into 10 equal intervals. The ratings are based mainly on the assessment of patient's functioning in four main areas: (1) socially useful activities; (2) personal and social relationships; (3) self-care; and (4) disturbing and aggressive behaviors. Operational criteria to rate the levels of disabilities have been defined for the above-mentioned areas. The total score exceeds 70 shows a high functioning, while a score below 70 indicates low functioning.[29,30] PSP has better face validity and psychometric properties. It was found to be an acceptable, quick, and valid measure of patients’ personal and social functioning. Excellent inter-rater reliability was also obtained in less educated workers.[31]

Tests of executive function used in the study

Wisconsin card sorting test

It examines problem-solving, novel concept formation, set-shifting/cognitive flexibility, and working memory.[32,33] The test consists of 128 cards of 2 sets of 64 cards each. There are stimuli of various forms printed on the cards. The stimuli vary in terms of three attributes, color, form, and number. The subject is instructed to study the cards and match each successive card from the pack to one of the four stimulus cards. The subject is told only whether each response is right or wrong and is never told the correct sorting principle. The subject must guess the concept based on the examiner's feedback and continue with the test. The numbers are put in serial orders for consecutive correct responses. After the subject places ten consecutive cards, the tester changes the concept without the subjects’ knowledge. The subjects’ capability to form a mental set is measured by how quickly he/she attains the concept and retains it for 10 consecutive trials. The test is terminated after the subject attains all the 6 concepts or after all the 128 cards have been used. The first principle of matching is by color, followed by form and finally by number. Then, the same sequence is repeated.

The following aspects were measured in the study:

Number of categories completed – It is the number of categories (i.e., each sequence of 10 consecutive correct matches to the criterion sorting category) that the client successfully completed during the test. Scores can range from minimum of 0 to maximum of 6

Perseverative errors – When a client persists in responding to a stimulus characteristic that is incorrect, the response is set to match the perseverated principle and is scored as perseverative. Clients may perseverate to color, form or number. Responses that do not match the sorting principle in effect are scored as errors

Percent perseverative errors – The total number of perseverative errors divided by the total number of trials administered and multiplied by 100.

The WCST is one of the most extensively used tests of frontal lobe function in clinical and research contexts.[33] It is also one of the most significant for schizophrenia is cognitive flexibility disorders.[34]

Stroop test (NIMHANS version)

This assesses attention, psychomotor speed, response inhibition, cognitive flexibility, and working memory. The color names blue, green, red, and yellow are printed in capital letters on a paper. The color of the print occasionally corresponds with the color designated by the word. The words are printed in 16 rows and 11 columns. Stimulus sheet is placed in front of the subject. The subject is asked to read the stimuli column-wise as fast as possible. The time taken to read all the 11 columns is noted down. Next, the subject is asked to name the color in which the word is printed.

This time also the subject proceeds column wise. The time taken to name all the colors is noted down. The reading time and the naming time were converted into seconds. The reading time was subtracted from the naming time to get the Stroop effect score. It can be successfully used in various settings due to its short administration time, reliability, validity, and ease of administration.[35,36]

The color trail tests 1 and 2

The color trail 1 test consists of numbers 1–25 that are randomly spread, with odd numbers in pink circles and even numbers in yellow ones. The subject is asked to point to successive numbers in ascending order 1–25. The time taken to complete the test is noted. It measures psychomotor speed.

The color trail 2 test consists of numbers from 2 to 25 are printed twice, once on pink circles and once on yellow circles. These are randomly arranged on the test sheet. The subject is asked to point to numbers in alternating colors with the successive numbers being in the ascending order. The time taken to complete the test is noted. It measures visuospatial working memory, ability to shift strategy, and executive function.

The validity of the color trail test has been documented in a variety of clinical and neuropsychological populations.[37,38]

Phonemic fluency (controlled oral word association test) and category fluency test

It measures initiation, psychomotor speed, fluency, cognitive flexibility, and working memory.[39,40,41]

Phonemic fluency – The subject is asked to generate words for 1 min in the case of each consonant starting with the consonant, i.e., F, A, S or in their mother tongue starting with Ka, Pa, Ma. The total number of acceptable new words in 1 min is noted down for each consonant. The average new words generated forms the score

Category fluency – The subject is asked to generate the names of as many animals as possible in 1 min. The subject is asked to exclude the names of fish bird and snakes. The number of names generated forms the score.

The tower of London test

It measures planning, sequencing, and working memory.[42] The subject is presented with a goal state of arrangement of the three balls on one of the boards which is placed near the examiner. The arrangement of the balls on the other board is the initial state. The subject must arrive at the goal state in the board placed on his side. This can be done with the minimum of 2 moves (for 2 moves problem), 3 moves (3 moves problems), 4 moves (4 moves problems), and 5 moves (5 moves problems). The test has a total of 12 problems. The first 2 problems can be solved with 2 moves, the next 4 problems can be solved with 3 moves, the next 4 problems with 4 moves, and the last 4 problems with 5 moves. In each problem, the time taken from start to finish is noted down. The next score is the number of moves used per problem.

The various scores calculated are namely meantime to solve the problem, mean number of moves, number of problems solved with minimum number of moves and an overall score of total number of problems solved with minimum number of moves (this is obtained by totaling the number of problems solved with minimum number of moves in each category of problems).

Statistical analysis

Based on the total score of the PSP the participants were divided into two groups namely each group had 30 patients.

Poor PSP group – with socio-occupational impairment (poor socio-occupational functioning; PSP total score ≤70)

Good PSP group – without socio-occupational impairment (good socio-occupational functioning; PSP total score >70).

Participants within each group were compared on sociodemographic characteristics and performance on various tests of executive function. Statistically analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software version 16.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to assess the socio-demographic characteristics of the patients. Unpaired t-test was used for continuous variables and Chi-square test for discrete variables. Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. All P values were two-tailed, and the statistical significance was calculated at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Comparison of sociodemographic variables of patients with and without socio-occupational impairment

Both groups were well matched on sociodemographic variables. The poor PSP group has greater number of patients that were unemployed (P = 0.001), living in rural areas (P = 0.001), higher scores on PANSS (P = 0.001), and longer mean duration of illness (P = 0.036) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of sociodemographic profiles in both groups

| Variables | Good PSP | Poor PSP | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender distribution | |||

| Male | 23 | 21 | 0.55† |

| Female | 7 | 9 | |

| Mean age (years) | 33.57 | 35.87 | 0.232‡ |

| Education | |||

| School educated | 0 | 5 | 0.02§,† |

| College educated | 30 | 25 | |

| Employment | |||

| Never employed | 0 | 13 | 0.001§,† |

| Unemployed | 0 | 17 | |

| Employed | 30 | 0 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 16 | 21 | 0.18† |

| Unmarried | 14 | 9 | |

| Residence | |||

| Urban | 30 | 20 | 0.001§,† |

| Rural | 0 | 10 | |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| High | 5 | 7 | 0.80† |

| Middle | 22 | 20 | |

| Lower | 3 | 3 | |

| Family history of psychiatric illness | |||

| Yes | 5 | 4 | 0.71† |

| No | 25 | 26 | |

| Mean PANSS total score | 50.53±5.64 | 63.63±6.20 | 0.001§,‡ |

| Mean duration of illness (months) | 71.80±70.68 | 113.20±78.38 | 0.036§,‡ |

§P<0.05 Significant; †Statistical analysis done using Chi-square test; ‡Statistical analysis done using unpaired t-test. PSP – Personal and Social Performance; PANSS – Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

Comparison of scores on various tests of executive function

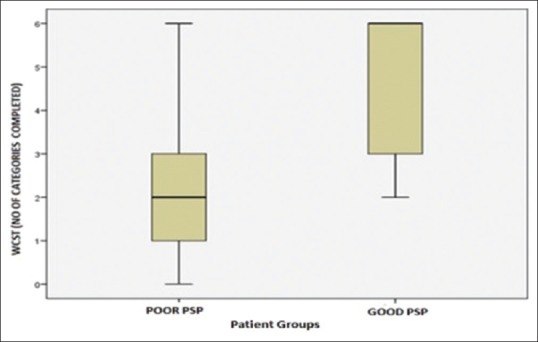

The mean WCST (number of categories completed) in good PSP group (4.73) was greater than the mean WCST (number of categories completed) in the poor PSP group (2.13) (P = 0.001) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Scores on number of categories of Wisconsin Card Sorting Test in both groups

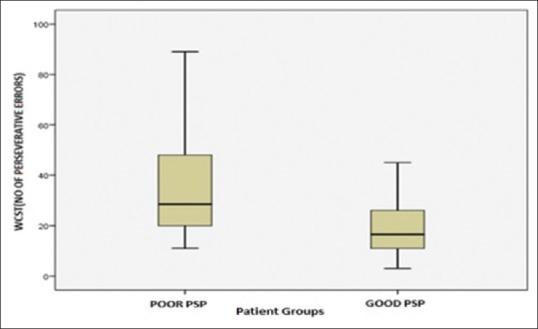

The mean WCST (number of perseverative errors) in poor PSP group (34.63) was greater than that in the good PSP group (19.87) (P = 0.001) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Number of Perseverative errors in both groups on Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

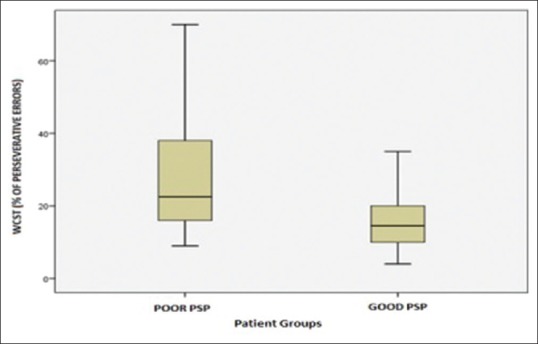

The mean WCST (percentage of perseverative errors) in poor PSP group (27.67) was greater than that in the good PSP group (16.33) (P = 0.001) [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Percentage of perseverative errors on Wisconsin Card Sorting Test in both groups

The mean Stroop Effect score (in secs) in poor PSP group (208.13) was greater than that in the good PSP group (173.60) (P = 0.094).

The mean Color Trails Test 1 time (in secs) in poor PSP group (84.37) was greater than the mean Color Trails Test 1 time (in secs) in the good PSP group (75.77). This difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.295).

The mean Color Trails Test 2 times (in secs) in poor PSP group (175.80) was greater than mean Color Trails Test 2 times (in secs) in the good PSP group (156.63). This difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.263).

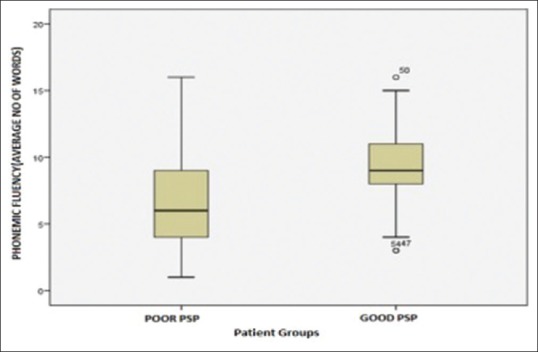

The mean phonemic fluency (average number of words) in good PSP group (9.07) was greater than the mean phonemic fluency (average number of words) in the poor PSP group (6.73). This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.012) [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Phonemic fluency (average number of words) in both groups

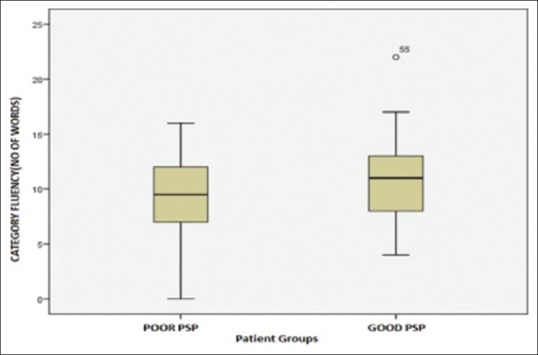

The mean category fluency (number of words) in good PSP group (11.00) was greater than the mean category fluency (number of words) in the poor PSP group (9.07). This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.049) [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Category fluency (number of words) in both groups

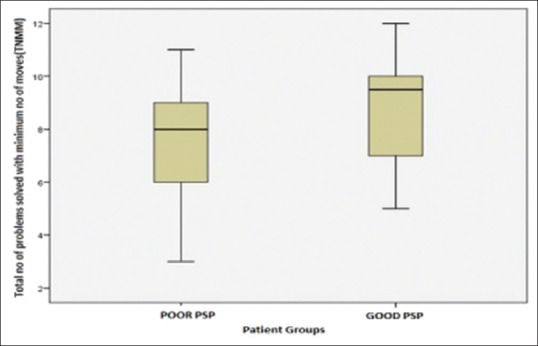

The mean total number of problems solved with minimum number of moves (transactional net margin method [TNMM]) in good PSP group (8.90) was greater than mean total number of problems solved with minimum number of moves (TNMM) in the poor PSP group (7.67). This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.021) [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Transactional net margin method in both groups

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the percentage of college-educated in those with good socio-occupational functioning (good PSP group) was higher than those with poor socio-occupational functioning (poor PSP group). The difference was statistically significant. Previous studies showed that more years of education positively influenced performance on tasks that tested executive function.[43] The duration of formal academic training reflected good premorbid functioning, intellectual level and a higher level of information-processing skills in the past. Patients with good education thus did well on cognitive tasks because of this inherent capability. These observations indicate that education may be a protecting factor of cognitive and social functioning in chronic schizophrenia.[44]

In this study, all of the patients in good socio-occupational functioning (good PSP) group were from the urban locality and were employed as compared to those in poor socio-occupational functioning (poor PSP) group. The study was conducted at a tertiary hospital located at a metropolitan city, so most of the patients in our total study sample that is both groups were from the urban locality and were college educated. Patients living in a large metropolitan city had potentially a better opportunity to enter the workforce than a nonurban population as stated by previous studies.[45] Employment status before admission to the hospital is a factor that can predict the outcome of psychosocial function, in which patients who do not work, the functional outcome was significantly lower.[46] In the present study, no statistically significant differences were found between gender, marital status, socioeconomic status, family history of psychiatric illness or age of patients in two groups.

In the present study, the patients with poor socio-occupational functioning (poor PSP) had greater mean negative symptom score on PANSS as compared to patients with good socio-occupational functioning (good PSP). Previous studies have shown a significant correlation between negative symptoms and functional outcome implying that the greater the severity of negative symptoms, the greater the cognitive deficits are; the results also suggest that negative symptoms are related to cognitive function to a greater extent than positive symptoms and cause more disability and thus negative symptoms predict employment outcomes.[47]

Furthermore, this study showed that the patients with poor socio-occupational functioning (poor PSP) had greater mean PANSS total score as compared to patients with good socio-occupational functioning (good PSP) and the difference was statistically significant.

The results of the present study showed that the mean duration of illness in months was greater in patients with poor socio-occupational functioning (poor PSP) as compared to those with good socio-occupational functioning (good PSP). The association found between longer duration of illness and worsening of performance on the WCST may additionally suggest the progressive character of executive dysfunctions in patients with chronic schizophrenia as indicated in previous studies.[48]

The results of the present study show that patients with good socio-occupational functioning (good PSP group) completed more number of categories, made fewer perseverative errors and percentage of perseverative errors as compared to poor socio-occupational functioning (poor PSP group). This is similar to previous studies.[49,50] These results show that WCST significantly affects the functional outcome and that better WCST performance is related to higher levels of work function. A study convincingly demonstrates what was suggested in the previous review, that WCST has significant relationships with functional outcome.[51] A meta-analytic study convincingly demonstrated what was suggested in the previous review, that WCST has significant relationships with functional outcome and that WCST was the most common way to assess executive functioning in most studies.[52] Another study showed that better executive functioning (WCST scores) were associated with more wages earned and more hours worked.[53] The negative correlation between WCST and functional outcome has also been reported.[54]

In the present study, the mean Stroop Effect score (in secs) in patients with poor socio-occupational functioning (poor PSP) although greater than patients with good socio-occupational functioning (good PSP), the difference was not statistically significant. However, studies have shown that the Stroop Test was significantly negatively correlated with the domains of social functioning which implied that the time taken to complete the task was negatively associated with social functioning.[55,56]

In the present study, no statistically, significant difference was found in the means of Color Trails Test 1 time (in secs) and means of Colour Trails Test 2 time (in secs) between the two groups. Previous studies have demonstrated no statistically significant difference between trail making test and functional outcome.[57,58] However, other researchers have shown that Trail test A and B were significantly negatively correlated with the domains of social functioning; it implied the time taken to complete the task was negatively associated with social functioning.[47]

In the present study, the mean phonemic fluency (average number of words) in patients with good socio-occupational functioning (good PSP) was greater than poor socio-occupational functioning (poor PSP) and the difference was statistically significant. The mean category fluency (number of words) in patients with good socio-occupational functioning (good PSP) was greater than poor socio-occupational functioning (poor PSP) and the difference was statistically significant. Previous studies showed that verbal fluency test (semantic and phonemic) had significant positive correlations with the social functioning domains. These results show that schizophrenia patients with good socio-occupational functioning would perform significantly better on verbal fluency tests and thus verbal fluency predicts functional outcome in patients with schizophrenia.[59,60] A higher level of education was connected with better results in verbal fluency test, which suggests the educational level has a beneficial influence on verbal abilities (reading and word generation).[61]

On analyzing the Tower of London test, the mean total number of problems solved with minimum number of moves (TNMM) in patients with good socio-occupational functioning (good PSP) was greater than poor socio-occupational functioning (poor PSP) and the difference was statistically significant. Other variables measured on Tower of London were not statistically significant. A study done earlier showed that Tower of London was most strongly associated with planning on macro (completeness and complexity of long-term life plans) and micro level (ability to organize the activity during the day). Patients, who did worse on Tower of London often, were unemployed and had other social role or engagement in activities that were below their educational and professional capabilities and they also coped with the labor duties worse.[62,63] In another study, the relationship between community functioning and planning was found. Planning is measured by Tower of London test, and thus, it predicts functional outcome in schizophrenia patients.[64]

This study emphasizes the need to acknowledge the importance of executive function in the recovery and long-term socio-occupational functioning in patients with schizophrenia. Remission is necessary but not sufficient step for recovery so the aim should be to achieve recovery in schizophrenia for better functional outcome.

A formal neuropsychological assessment for individuals with schizophrenia is recommended with valid and reliable tests. As this assessment will serve as a prognostic marker and will guide further optimal management. Given the importance of neurocognition to the functioning and rehabilitative change, it is important to focus on interventions to improve neurocognition in schizophrenia. The executive functions measured by these tests can be targeted for cognitive remediation therapy. Further studies are needed for better understanding of the neurobiology of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia and study the significance of sociodemographic factors in functional outcome of schizophrenia patients.

Limitations of the study

The intelligence (and hence the cognitive reserve) of the study participants was not tested, although any history suggestive of a developmental delay was excluded from the participants. Some studies have shown executive deficits to be independent of the IQ. The two groups differed in terms of years of education, and this could be a limiting factor that affected performance on executive function tests. All patients in our study were on medications, including antipsychotics, anticholinergics, and benzodiazepines which may have caused minor cognitive deficits. The effect of medication on test performance cannot be ruled out. The sample size was small and circumscribed to one center. Larger studies are needed to validate the results.

CONCLUSIONS

Cognitive flexibility, working memory, verbal fluency, psychomotor speed, and planning are useful tools of executive function to assess the ability of patients with schizophrenia and can be a marker of socio-occupational ability. These tests can serve as potential markers in the future to assess the ability of these patients to perform in an occupational domain. Larger studies across different populations are needed further to validate the findings of our studies.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, Welham J. Schizophrenia: A concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:67–76. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajji TK, Miranda D, Mulsant BH. Cognition, function, and disability in patients with schizophrenia: A review of longitudinal studies. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59:13–7. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knowles EE, Weiser M, David AS, Glahn DC, Davidson M, Reichenberg A. The puzzle of processing speed, memory, and executive function impairments in schizophrenia: Fitting the pieces together. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78:786–93. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Logue SF, Gould TJ. The neural and genetic basis of executive function: Attention, cognitive flexibility, and response inhibition. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2014;123:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson HE. A modified card sorting test sensitive to frontal lobe defects. Cortex. 1976;12:313–24. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(76)80035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teubner-Rhodes S, Vaden KI, Jr, Dubno JR, Eckert MA. Cognitive persistence: Development and validation of a novel measure from the Wisconsin card sorting test. Neuropsychologia. 2017;102:95–108. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gathercole SE, Baddeley AD. London: Psychology Press; 2014. Working Memory and Language. [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Esposito M, Postle BR. The cognitive neuroscience of working memory. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:115–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacLeod CM. Half a century of research on the stroop effect: An integrative review. Psychol Bull. 1991;109:163–203. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman NP, Miyake A. Unity and diversity of executive functions: Individual differences as a window on cognitive structure. Cortex. 2017;86:186–204. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2016.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugarman MA, Axelrod BN. Embedded measures of performance validity using verbal fluency tests in a clinical sample. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. 2015;22:141–6. doi: 10.1080/23279095.2013.873439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costa A, Bagoj E, Monaco M, Zabberoni S, De Rosa S, Papantonio AM, et al. Standardization and normative data obtained in the Italian population for a new verbal fluency instrument, the phonemic/semantic alternate fluency test. Neurol Sci. 2014;35:365–72. doi: 10.1007/s10072-013-1520-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeung MK, Sze SL, Woo J, Kwok T, Shum DH, Yu R, et al. Altered frontal lateralization underlies the category fluency deficits in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A near-infrared spectroscopy study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:59. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koechlin E. Prefrontal executive function and adaptive behavior in complex environments. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2016;37:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Georgiou GK, Li J, Das JP. Tower of London: What level of planning does it measure? Psychol Stud. 2017;62:261–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nitschke K, Köstering L, Finkel L, Weiller C, Kaller CP. A meta-analysis on the neural basis of planning: Activation likelihood estimation of functional brain imaging results in the tower of London task. Hum Brain Mapp. 2017;38:396–413. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turek A, Machalska K, Chrobak AA, Tereszko A, Siwek M, Dudek D. Speech graph analysis of verbal fluency tests distinguish between patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27:S914–5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quan W, Wu T, Li Z, Wang Y, Dong W, Lv B. Reduced prefrontal activation during a verbal fluency task in Chinese-speaking patients with schizophrenia as measured by near-infrared spectroscopy. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2015;58:51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fillman SG, Weickert TW, Lenroot RK, Catts SV, Bruggemann JM, Catts VS, et al. Elevated peripheral cytokines characterize a subgroup of people with schizophrenia displaying poor verbal fluency and reduced Broca's area volume. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:1090–8. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haut KM, Karlsgodt KH, Bilder RM, Congdon E, Freimer NB, London ED, et al. Memory systems in schizophrenia: Modularity is preserved but deficits are generalized. Schizophr Res. 2015;168:223–30. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liemburg EJ, Dlabac-De Lange JJ, Bais L, Knegtering H, van Osch MJ, Renken RJ, et al. Neural correlates of planning performance in patients with schizophrenia – Relationship with apathy. Schizophr Res. 2015;161:367–75. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenwood KE, Landau S, Wykes T. Negative symptoms and specific cognitive impairments as combined targets for improved functional outcome within cognitive remediation therapy. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31:910–21. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fervaha G, Foussias G, Agid O, Remington G. Motivational and neurocognitive deficits are central to the prediction of longitudinal functional outcome in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130:290–9. doi: 10.1111/acps.12289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hegde S, Thirthalli J, Rao SL, Raguram A, Philip M, Gangadhar BN. Cognitive deficits and its relation with psychopathology and global functioning in first episode schizophrenia. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013;6:537–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taksal A, Sudhir PM, Janakiprasad KK, Viswanath D, Thirthalli J. Impact of the integrated psychological treatment (IPT) on social cognition, social skills and functioning in persons diagnosed with schizophrenia: A feasibility study from India. Psychosis. 2016;8:214–25. [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases. 10th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma T, Antonova L. Cognitive function in schizophrenia.Deficits, functional consequences, and future treatment. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2003;26:25–40. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(02)00084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cameron N. Schizophrenic thinking in a problem-solving situation. Br J Psychiatry. 1939;85:1012–35. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldstein K, Scheerer M. Abstract and concrete behavior an experimental study with special tests. Psychol Monogr. 1941;53:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV social and occupational functioning assessment scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:323–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldberg TE, Goldman RS, Burdick KE, Malhotra AK, Lencz T, Patel RC, et al. Cognitive improvement after treatment with second-generation antipsychotic medications in first-episode schizophrenia: Is it a practice effect? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1115–22. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green MF, Nuechterlein KH. The MATRICS initiative: Developing a consensus cognitive battery for clinical trials. Schizophr Res. 2004;72:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kałwa A, Rzewuska M, Borkowska A. Cognitive dysfunction progression in schizophrenia-relation to functional and clinical outcome. Arch Psychiatr Psychother. 2009;1:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rao NP, Arasappa R, Reddy NN, Venkatasubramanian G, Reddy YC. Emotional interference in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A neuropsychological study using optimized emotional stroop test. Psychiatry Res. 2010;180:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krishna R, Udupa S, George CM, Kumar KJ, Viswanath B, Kandavel T, et al. Neuropsychological performance in OCD: A study in medication-naïve patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:1969–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D’Elia L, Satz P. USA: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1996. Color Trails Test. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dugbartey AT, Townes BD, Mahurin RK. Equivalence of the color trails test and trail making test in nonnative English-speakers. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2000;15:425–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benton AL, Hamsher K. Multilingual Aphasia Examination. Iowa City: AJA Associates; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lezak MD. Neuropsychological Assessment. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tombaugh TN, Kozak J, Rees L. Normative data stratified by age and education for two measures of verbal fluency: FAS and animal naming. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1999;14:167–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shallice T. Specific impairments in planning. Philos Transc R Soc London. 1982;298:199–209. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1982.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Srinivasan L, Thara R, Tirupati SN. Cognitive dysfunction and associated factors in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2005;47:139–43. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.55936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Henry JD, Crawford JR. A meta-analytic review of verbal fluency deficits in schizophrenia relative to other neurocognitive deficits. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2005;10:1–33. doi: 10.1080/13546800344000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srinivasan L, Tirupati S. Relationship between cognition and work functioning among patients with schizophrenia in an urban area of India. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1423–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.11.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brissos S, Molodynski A, Dias VV, Figueira ML. The importance of measuring psychosocial functioning in schizophrenia. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2011;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Santosh S, Dutta Roy D, Kundu PS. Psychopathology, cognitive function, and social functioning of patients with schizophrenia. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2013;23:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kałwa A, Rzewuska M, Borkowska A. Cognitive dysfunction progression in schizophrenia – Relation to functional and clinical outcome. Arch Psychiatry Psychother. 2012;1:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhagyavathi HD, Mehta UM, Thirthalli J, Kumar CN, Kumar JK, Subbakrishna DK, et al. Cascading and combined effects of cognitive deficits and residual symptoms on functional outcome in schizophrenia – A path-analytical approach. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229:264–71. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hegde S. A review of Indian research on cognitive remediation for schizophrenia. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;25:54–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guastella AJ, Hermens DF, Van Zwieten A, Naismith SL, Lee RS, Cacciotti-Saija C, et al. Social cognitive performance as a marker of positive psychotic symptoms in young people seeking help for mental health problems. Schizophr Res. 2013;149:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Green MF. What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:321–30. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Harvey PD, LaPuglia R, Marder J. Cognitive and symptom predictors of work outcomes for clients with schizophrenia in supported employment. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:1129–35. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.8.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krishnadas R, Moore BP, Nayak A, Patel RR. Relationship of cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia in remission to disability: A cross-sectional study in an Indian sample. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2007;6:19. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mehta UM, Thirthalli J, Subbakrishna DK, Gangadhar BN, Eack SM, Keshavan MS. Social and neuro-cognition as distinct cognitive factors in schizophrenia: A systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2013;148:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ergen M, Saban S, Kirmizi-Alsan E, Uslu A, Keskin-Ergen Y, Demiralp T. Time-frequency analysis of the event-related potentials associated with the Stroop test. Int J Psychophysiol. 2014;94:463–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2014.08.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buchanan RW, Holstein C, Breier A. The comparative efficacy and long-term effect of clozapine treatment on neuropsychological test performance. Biol Psychiatry. 1994;36:717–25. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nuechterlein KH, Barch DM, Gold JM, Goldberg TE, Green MF, Heaton RK. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;72:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Neill E, Gurvich C, Rossell SL. Category fluency in schizophrenia research: Is it an executive or semantic measure? Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2014;19:81–95. doi: 10.1080/13546805.2013.807233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Minor KS, Luther L, Auster TL, Marggraf MP, Cohen AS. Category fluency in psychometric schizotypy: How altering emotional valence and cognitive load affects performance. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2015;20:542–50. doi: 10.1080/13546805.2015.1116441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shao Z, Janse E, Visser K, Meyer AS. What do verbal fluency tasks measure? Predictors of verbal fluency performance in older adults. Front Psychol. 2014;5:772. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lam BY, Raine A, Lee TM. The relationship between neurocognition and symptomatology in people with schizophrenia: Social cognition as the mediator. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:138. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yeo RA, Martinez D, Pommy J, Ehrlich S, Schulz SC, Ho BC, et al. The impact of parent socio-economic status on executive functioning and cortical morphology in individuals with schizophrenia and healthy controls. Psychol Med. 2014;44:1257–65. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alekseev AA, Rupchev GE. Relationship between executive function and everyday functioning in schizophrenia (in Russian sample) Proc Soc Behav Sci. 2013;86:183–7. [Google Scholar]