ABSTRACT

The kinetochore is a large protein complex that ensures accurate chromosome segregation during mitosis by connecting the centromere and spindle microtubules. One of the kinetochore sub-complexes, the constitutive centromere-associated network (CCAN), associates with the centromere and recruits another sub-complex, the KMN (KNL1, Mis12, and Ndc80 complexes) network (KMN), which binds to spindle microtubules. The CCAN-KMN interaction is mediated by two parallel pathways (CENP-C- and CENP-T-pathways) in the kinetochore, which bridge the centromere and microtubules. Here, we discuss dynamic protein-interaction changes in the two pathways that couple the centromere with spindle microtubules during mitotic progression.

KEYWORDS: Kinetochore, CCAN, KMN, mitosis

Introduction

Correct chromosome segregation during cell division is essential for self-replication in living organisms. Accurate chromosome segregation in eukaryotic cells is achieved by correct bipolar attachment of the spindle microtubules to sister centromeres. The centromere-microtubule linkage is ensured by a large protein complex called the kinetochore, which is assembled on the centromeric chromatin (Figure 1) [1–3]. The kinetochore also provides a binding platform for spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) proteins to monitor and correct malattachments of the microtubules to kinetochores [1,4–6]. Since the kinetochore plays such crucial roles, deciphering how the complex is assembled is important for understanding how the accurate chromosome segregation is guaranteed.

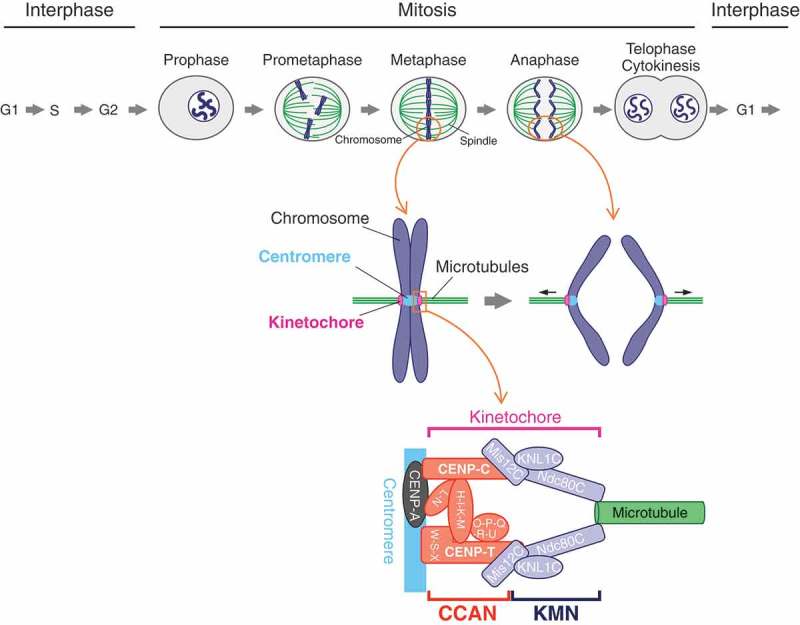

Figure 1.

Chromosome segregation and the kinetochore architecture in vertebrate mitosis. The duplicated genome in the S-phase is segregated equally to the next generation during mitosis. The chromosomes begin condensation in late G2 to prophase. In subsequent prometaphase to metaphase, the condensed chromosomes, which are captured by the spindle microtubules, are aligned along the equator of the cell. The microtubules attach to the kinetochore, which is formed on the centromere specified by histone H3 variant CENP-A. The kinetochore harnesses the pulling-force from the microtubules, bringing the segregated chromosomes (sister chromatids) to the opposite poles of the spindle during anaphase. The main architecture of the kinetochore is built with the constitutive centromere-associated network (CCAN) composed of 16 protein subunits and the KMN (KNL1, Mis12, and Ndc80 complexes: KNL1C, Mis12C, Ndc80C) network (KMN). CCAN and KMN interact with the centromere and spindle microtubule, respectively, making a linkage between the centromere and microtubules.

The kinetochore in vertebrates consists of more than a hundred proteins including structural sub-complexes and proteins that ensure the bipolar attachment such as SAC proteins [1,5,7,8]. A 16-protein complex called constitutive centromere-associated network (CCAN) is one of the major sub-complexes that form the kinetochore architecture (Figure 1) [8,9]. As the name implies, CCAN constitutively localizes to the centromere which is epigenetically marked by a centromere-specific histone H3 variant, centromere protein (CENP)-A [3,10,11] during cell cycle progression [1,9]. Another key kinetochore sub-complex is the KNL1-Mis12-Ndc80 complexes network (KMN network or KMN) (Figure 1) [2,12]. In contrast to CCAN which localizes to the centromere constitutively during the cell cycle, full KMN is assembled onto CCAN during mitosis [2,12], though centromere localization of the Mis12 complex (Mis12C) and the KNL1 complex (KNL1C) occurs in a subset of interphase cells [13,14]. Since the Ndc80 complex (Ndc80C) is a major microtubule-binding factor [2,12], the recruitment of KMN onto CCAN is a key step for the linkage between the centromere and spindle microtubules.

Two CCAN components, CENP-C and CENP-T, bind to KMN, independently [15–19]. Both proteins have KMN-binding regions in their N-terminus, shown by biochemical studies including in vitro reconstitution with recombinant proteins as well as cell biological analysis [15–19]. The interaction between CENP-C and Mis12C in KMN has been highlighted in previous studies [18,20–23], because CENP-C is conserved and essential for centromere function among major model systems including budding and fission yeasts, roundworms, fruit flies and vertebrates [24,25]. While CENP-T binds to both Ndc80C and Mis12C directly [17,19], significance of these interactions has not been well focused, since CENP-T is absent in some organisms such as roundworms or fruit flies [24,25]. However, in recent years, accumulating data have suggested the importance of KMN binding to CENP-T, especially in vertebrates [26–28]. In this review, we summarize how CCAN recruits KMN to the kinetochore and also discuss plasticity in their interaction interface.

CCAN

The centromere position in vertebrates is defined by sequence-independent epigenetic mechanisms [3]. A critical epigenetic marker is the centromere-specific histone H3 variant, CENP-A, which forms a nucleosome with canonical histones H2A, H2B, and H4 [10,11]. Posttranslational modifications on the histones in the CENP-A nucleosome are also important for centromere protein assembly [29,30]. CCAN is one of the kinetochore sub-complexes and constitutively localizes to the centromere during cell cycle progression [8–10]. In vertebrates, CCAN contains 16 proteins (CENP-C, -H, -I, -K, -L, -M, -N, -O, -P, -Q, -R, -S, -T, -U, -W, and -X), which are divided into sub-groups: CENP-C, the CENP-HIKM complex, the CENP-LN complex, the CENP-OPQRU complex, the CENP-TWSX complex (Figure 1) [8–10]. All sub-groups except for the CENP-OPQRU complex are essential for cell viability in vertebrate somatic cells [9]. Since CENP-C and CENP-N directly bind to CENP-A nucleosome, it is proposed that their CENP-A recognition contributes to centromere-specific localization of CCAN [31–36].

KMN

KMN, which is recruited onto CCAN during mitosis, consists of three sub-complexes: KNL1C including KNL1 and Zwint, Mis12C including Mis12, Nnf1 (also known as PMF1), Nsl1, and Dsn1, and Ndc80C including Ndc80, Nuf2, Spc24, and Spc25 (Figure 1) [2,12]. Ndc80C forms a rod-like structure with globular domains in both ends [37] (see also Figure 4). One of the globular domains consists of the Ndc80-Nuf2 sub-complex and provides an interface for microtubule binding [37]. The other globular domain, which is made of the Spc24-Spc25 sub-complex, binds to Mis12C and also to CENP-T, a CCAN protein [17,21]. Mis12C components, Dsn1 and Nsl1, form an interface for the Spc24-Spc25-binding [21,38]. In addition, Mis12C interacts with KNL1C, making a central hub for KMN [38]. KMN also interacts with other additional kinetochore proteins, which monitor and ensure bipolar attachment, working as a signaling platform for the surveillance systems including error collection and SAC.

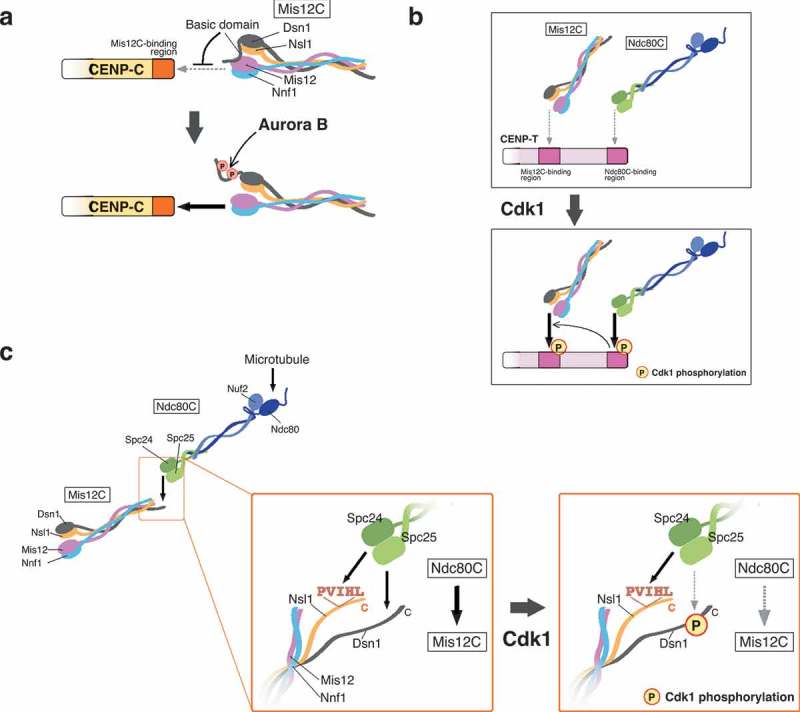

Figure 4.

Kinetochore-protein interactions controlled by various phospho-regulations. (a) Model for CENP-C and Mis12 complex (Mis12C) interaction. Mis12C consists of Mis12, Dsn1, Nsl1, and Nnf1 (also known as PMF1). The interaction between CENP-C and Mis12C is inhibited by the basic domain of Dsn1, which masks the CENP-C-binding interface in Mis12C. Aurora B kinase phosphorylates the basic domain to release the inhibition, promoting stable binding of CENP-C to Mis12C. (b) Model for CENP-T interaction with the Ndc80 complex (Ndc80C) and Mis12C. CENP-T has the Mis12C- and Ndc80C-binding regions, and Cdk1 phosphorylates these regions and increases their binding affinity to Mis12C and Ndc80C, respectively. The Ndc80C-CENP-T interaction is an upstream event of the Mis12C-CENP-T interaction. (c) Model for the Mis12C-Ndc80C interaction. Ndc80C consists of Ndc80, Nuf2, Spc24, and Spc25. The globular domain of the Spc24-Spc25 sub-complex (Spc24-Spc25) interacts with Nsl1 and Dsn1 in Mis12C. Nsl1 interacts with Spc24-Spc25 through the PVIHL motif in its C-terminus. The Dsn1 C-terminus has the Ndc80C-binding region. Multivalent interaction surfaces seem to contribute to stable interaction between Mis12C and Ndc80C. Cdk1 phosphorylation in the Ndc80C-binding region of Dsn1 reduces its affinity to Spc24-Spc25, resulting in unstable interaction between Mis12C and Ndc80C.

Two pathways from the centromere to spindle microtubules

Since Ndc80C in KMN binds to microtubules together with other microtubule-binding proteins [39], the recruitment of KMN subunits onto CCAN is a key process for establishing microtubule attachment to the kinetochore. In vitro reconstitution and structural studies demonstrated that two CCAN components, CENP-C and CENP-T, directly bind to KMN through their N-terminal region (Figure 2(a)) [17–19,21]. These proteins also bind to the centromere chromatin via their C-terminal region (Figure 2(a)) [17,33,40,41]; thus, the two-pathways (CENP-C- and CENP-T-pathways) model has been proposed for KMN recruitment onto CCAN to make bridges between the centromere and spindle microtubules (Figure 2(b)) [1,9].

Figure 2.

Two-pathways model connecting the centromere to spindle microtubules. (a) Schematic representation of human CENP-C and CENP-T. Human CENP-C interacts with various centromere/kinetochore proteins. The Mis12 complex (Mis12C)-binding region in the extreme N-terminus binds to KMN, which associates with the spindle microtubules. The PEST-rich region interacts with the CCAN sub-complexes, CENP-HIKM, and CENP-LN. There are two CENP-A nucleosome-binding regions: central domain and CENP-C motif. The dimerization domain in the extreme C-terminus is thought to promote self-dimerization. Human CENP-T directly binds to the Ndc80 complex (Ndc80C) through the extreme N-terminus (Ndc80C-binding region). Mis12C interacts to the Mis12C-binding region next to the Ndc80C-binding region (Mis12C-binding region). There is a histone fold domain in the C-terminus, which forms a nucleosome like complex with CENP-W, -S and -X, which also contain histone fold domains. The complex interacts with the centromere chromatin. (b) Two pathways in the kinetochore that bridge the centromere to microtubules: CENP-C- and CENP-T-pathways. Both CENP-C and CENP-T bind to KMN via their N-terminus and centromere chromatin via their C-terminus, independently, making the two pathways in the kinetochore.

The CENP-C-pathway

CENP-C was originally identified as an antigen of sera from patients with autoimmune diseases [42,43]. CENP-C is conserved and essential for chromosome segregation in most model organisms [24,25,44]. CENP-C has multiple-conserved domains, which bind specifically to other centromere proteins: Mis12-binding domain in the N-terminus [16,18,20,21], CENP-HIKM and CENP-LN complexes-binding domain in the middle-conserved region [45,46], and two CENP-A nucleosome-binding domains in human CENP-C (Figure 2(a)) [31,33,47]. The extreme C-terminus is also conserved and involved in CENP-C dimerization [48,49]. Since CENP-C interacts with KMN, other CCAN, and the CENP-A nucleosome, CENP-C has been proposed as a central hub of kinetochore assembly in human cells [32,45].

In vitro biochemical studies demonstrated that the extreme N-terminus of human CENP-C directly binds to Mis12C [18,21]. The CENP-C N-terminus is required for KMN recruitment in Drosophila or Xenopus experimental systems [20,50]. Consistent with this, artificial tethering of the CENP-C N-terminus to a non-centromeric locus in human and chicken cells was sufficient for recruiting KMN onto this locus [15,16,51]. The artificial tethering of the CENP-C N-terminus at a non-centromeric locus induces a functional kinetochore in chicken DT40 cells, which is able to ensure normal chromosome segregation after removal of the native centromere on chicken chromosome Z [15]. Importantly, no other CCAN proteins localize to the artificial kinetochore induced by the CENP-C N-terminus, indicating that CENP-C N-terminus is sufficient for recruiting KMN and forming a functional kinetochore, independently of other CCAN proteins [15].

The CENP-T-pathway

Another scaffold in CCAN for KMN recruitment of vertebrate cells is CENP-T, which was originally identified by mass-spectrometry analyses of CENP-A containing chromatin fractions [52,53]. CENP-T has KMN-binding regions in the N-terminus as well as a histone fold domain in the C-terminus (Figure 2(a)) [15–17,19,51,54]. The histone fold forms a nucleosome-like structure in vitro with other histone fold-containing CCAN proteins such as CENP-S, -W, and -X [54]. Since the CENP-TWSX complex binds to the centromere DNA in vivo and mutation of the DNA binding region of the complex shows severe mitotic defects, association of the complex with centromere chromatin is essential for proper chromosome segregation [40,41,54].

In contrast to CENP-C, which recruits Ndc80C through Mis12C-binding, the CENP-T N-terminus directly interacts with Ndc80C (Figure 2(a)) [16,17,19,51]. Human CENP-T has two Ndc80C-binding sites, whereas chicken CENP-T and the budding yeast CENP-T homolog CNN1 have one site [17,55]. In addition to Ndc80C, the CENP-T N-terminus also binds to Mis12C (Figure 2(a)) [15,16,19,51]. Recent in vitro studies showed that human CENP-T recruits three Ndc80C on it [19]: two are recruited directly and one indirectly through Mis12C interactions, and proposed that the multivalency of Ndc80C (three bound to one CENP-T) is important for kinetochore interaction with microtubules in human cells [56]. The artificial tethering of the CENP-T N-terminus recruits KMN on a non-centromeric locus in vertebrate cells [15,16]. Consistent with biochemical studies [17,19], the tethering assay demonstrated that Ndc80C and Mis12C binding regions are separated in the CENP-T N-terminus [15,51]. The artificial tethering of CENP-T N-terminus induces the formation of a functional kinetochore without other CCAN proteins in chicken DT40 cells, as observed from CENP-C N-terminus tethering [15].

Two-pathways model

The in vitro reconstitution with recombinant proteins and the artificial kinetochore assays clearly demonstrate that both CENP-C and CENP-T independently make direct contacts with KMN, and that such interaction enables them to build a functional kinetochore on an artificial tethering site [15–17,21]. Since both CENP-C and CENP-T have their own centromere-binding interface in the C-terminus [17,32,33,40,41,47], this led to the two-pathways model in which CENP-C and CENP-T provide two independent pathways for recruiting KMN onto centromeres (Figure 2(b)) [1,9].

The CENP-C-pathway vs the CENP-T-pathway in native kinetochores

The CENP-C- and CENP-T-pathways both exist in the native kinetochores of vertebrate cells [1,9]. However, the question remained to be addressed was how the two pathways work together in native kinetochores. Based on in vitro reconstitution studies, the CENP-C-pathway is thought to be the main scaffold for making a linkage between the centromere and spindle microtubules in human cells [45]. However, our recent results have revealed that the CENP-C and Mis12C interaction is dispensable for cell viability and chromosome segregation in chicken DT40 cells [26]. Taking advantage of the conditional knock-out system of chicken DT40 cells, we replaced wild-type chicken CENP-C (CENP-C WT) with a mutant CENP-C (CENP-C ∆73) that lacks the Mis12C-binding region, in DT40 cells (Figure 3(a)). Cells only expressing CENP-C ∆73 divided normally, in the same manner as cells expressing CENP-C WT (Figure 3(a)) [26]. Since the CENP-T-pathway is still active in cells expressing CENP-C ∆73, we thought that CENP-C and CENP-T might be redundant; however, this was not the case. Replacement of CENP-T WT with a CENP-T mutant lacking the Ndc80C-binding region (CENP-T ∆90) in DT40 cells, which makes the CENP-C-pathway the sole pathway in the cells, did not support for cell growth (Figure 3(b)) [26]. Furthermore, the Mis12C-binding domain in CENP-T is also essential for cell viability (Figure 3(b), CENP-T ∆120–240) [26]. These findings indicate that KMN-binding of CENP-T, but not of CENP-C, is essential for centromere function, suggesting that CENP-T makes the dominant pathway for linking between the centromere and spindle microtubules during mitosis in DT40 cells. Using a tension sensor system, we have found that CENP-T harnesses microtubule-dependent pulling-forces during mitosis, but CENP-C does not seem to be applied tension from microtubules [26]. This observation also supports the idea that the CENP-T pathway is more important than the CENP-C-pathway for the bridge from the centromere to microtubules.

Figure 3.

CENP-T forms a major pathway for linking the centromere and microtubules in chicken DT40 cells. (a) Schematic representation of chicken CENP-C. All functional domains in human CENP-C are conserved in chicken full-length CENP-C (FL), with exception of the central domain which is one of CENP-A binding domains in human CENP-C. A CENP-C mutant in which the Mis12 complex (Mis12C)-binding region is deleted (∆73) is able to complement CENP-C deficiency in chicken DT40 cells, suggesting that Mis12C-binding of CENP-C is dispensable for proper chromosome segregation in DT40 cells. (b) Schematic representation of chicken CENP-T. Chicken CENP-T has the Ndc80 complex- (Ndc80C) and Mis12C-binding regions as well as the histone fold domain in human CENP-T. CENP-T deficiency in DT40 cells are complemented by full-length CENP-T (FL), but not by CENP-T mutants lacking the Ndc80C- or Mis12C-binding region (∆90 or ∆120–240, respectively), indicating that those regions are essential for viability of DT40 cells. (c) Dynamic changes in the CCAN–KMN interaction making CENP-T the major pathway. Aurora B kinase phosphorylates Mis12C, facilitating interaction between CENP-C and Mis12C, which brings KNL1 complex (KNL1C), at onset of mitosis (late G2/prophase). Cdk1 phosphorylates CENP-T to promote stable binding of Mis12C and Ndc80C to the CENP-T-pathway. Cdk1 phosphorylation on Mis12C reduces its affinity to Ndc80C. When the pulling force is applied on the kinetochore from the microtubules, Mis12C could be spatially separated from Aurora B kinase, and its Aurora B phosphorylation is likely to be dephosphorylated by protein phosphatase 1 (PP1). These phospho-regulatory mechanisms result in dynamic changes in the CCAN–KMN interaction during mitotic progression. Consequently, the major fraction of Ndc80C interacts with the CENP-T-pathway, making it the major linkage between the centromere and spindle microtubules.

Dynamic interaction of CCAN-KMN during mitotic progression

Centromere localization of Mis12C is found in a subset of interphase cells and all mitotic cells [13]. In contrast, Ndc80C is loaded onto centromeres during mitosis [57]. Our detailed analysis of KMN localization found that localization levels of Mis12C and Ndc80C on kinetochores are varied during mitotic progression (Figure 3(c)), providing a clue for explaining why the CENP-T-pathway is dominant in the chicken cells [26].

Mis12C is found in centromeres during prophase and the Mis12C localization at this stage is dependent on CENP-C. In the subsequent prometaphase, Mis12C starts binding to CENP-T in addition to CENP-C, resulting in increased of total levels of Mis12C on centromeres. Subsequently, the levels of CENP-T-binding Mis12C are constant in metaphase and anaphase, but those of CENP-C binding Mis12C are decreased in these phases. The Ndc80C levels on centromeres are also dynamic. The Ndc80C levels are undetectable during prophase and then reach to the highest during prometaphase. Importantly, centromere localization of a majority of Ndc80C is dependent on CENP-T, but less dependent on CENP-C. Ndc80C remains on CENP-T from metaphase to anaphase, though its levels are reduced. These dynamic changes of KMN-CCAN interaction make CENP-T a major KMN-binding scaffold during metaphase (Figure 3(c)), which is consistent with results showing that KMN-binding to CENP-T, but not to CENP-C, is essential for DT40 cell viability [26].

Our observations of the interaction changes for CCAN-KMN are consistent with a previous study, which analyzed protein copy numbers on kinetochores in human cells. Suzuki et al. [27] quantified copy numbers of kinetochore proteins using quantitative fluorescence microscopy and demonstrated that the CENP-T-pathway recruited more Ndc80C than the CENP-C-pathway in mitotic human cells. They also showed that a majority of CENP-C was unbound to Mis12C. These results are further supported with data using super-resolution microscopy by the same group for detailed localization of kinetochore proteins in mitotic human cells [28]. Their results indicate that the CENP-C C-terminus, which binds to the CENP-A nucleosome, is placed near the surface of the centromeric chromatin; in addition, the middle part of CENP-C stretches away from the centromere, but its N-terminus turns back inside close to the centromere surface [28]. In contrast, CENP-T forms an elongated configuration in the kinetochore and the CENP-T C-terminus, which binds to DNA, localizes near to the centromeric chromatin, whereas its KMN-binding region in the N-terminus stretches to outside of the kinetochore where Ndc80C is placed [28]. This microscopic observation also supports with the idea that CENP-T functions as the major load-bearing pathway.

Phospho-regulation for CCAN-KMN interaction

Extensive studies using cell biological, biochemical, and structural approaches have demonstrated that protein phosphorylation is one of the key regulators for the CCAN–KMN interaction during mitosis [58]. In fact, the known phospho-regulatory processes can sufficiently explain the changes in the CCAN–KMN interaction during mitotic progression.

A mitotic kinase, Aurora B kinase (AurB), which resides in the centromere, phosphorylates multiple kinetochore proteins, and is involved in error collection and SAC [59,60]. AurB phosphorylation on kinetochores is counteracted with protein phosphatase 1 (PP1), which localizes to distal kinetochores [61,62]. Once the bipolar-microtubule attachment is established, the pulling-force stretches kinetochores and spatially separates the AurB substrates from the AurB, which departs from the centromere and localizes into the midzone during anaphase, leading to dephosphorylation of the kinetochore substrates by PP1 [59,60].

AurB phosphorylation also controls the CENP-C-Mis12C interaction [21,63,64]. Structural analyses demonstrated that Dsn1 in Mis12C has an auto-inhibitory role in the Mis12C-CENP-C interaction through its conserved basic domain (Figure 4(a)) [21,22]. AurB phosphorylation on the basic domain releases the inhibition of Mis12C-CENP-C interaction, which increases the binding affinity between Mis12C and CENP-C in vitro and facilitates Mis12C localization to the centromere in mitotic cells [21,63,64]. Given that the bipolar-attachment induces PP1-dependent dephosphorylation of AurB substrates, the Dsn1 basic domain could also be dephosphorylated at this stage, presumably leading to reduction of binding-affinity between CENP-C and Mis12C in metaphase and anaphase; this is consistent with our observation that levels of CENP-C binding Mis12C are decreased in metaphase and anaphase (Figure 3(c)) [26]. Therefore, the CENP-C-pathway could not provide enough strength for the load-bearing microtubule attachment. This can explain why the mutant cells with only the CENP-C-pathway are lethal. Indeed, the forced-binding of Mis12C to CENP-C in the mutant cells suppresses their growth defects [26].

Mitotic phosphorylation also plays a key role in regulation of the CENP-T-KMN interaction. The CENP-T N-terminus has the Ndc80C-binding region, which interacts with the Spc24-Spc25 subcomplex in Ndc80C (Figure 4(b)) [17]. This interaction is stabilized by phosphorylation at Cdk1 consensus motifs in the CENP-T N-terminus; human CENP-T has two Cdk1 consensus motifs, whereas chicken CENP-T has one motif [17,19,51]. Phosphorylation at these sites is required for Ndc80C recruitment to the CENP-T-pathway in mitotic human cells [19,51]. Cyclin B-Cdk1 (CycB-Cdk1) should be the kinase that regulates the CENP-T-Ndc80C interaction in mitosis. CycB-Cdk1 is a kinase that governs mitotic entry and exit; activation of CycB-Cdk1 induces mitotic entry and inactivation leads to exit from mitosis. Therefore, CycB-Cdk1 activity induces Ndc80C-binding to CENP-T during mitosis.

In addition to the CENP-T-Ndc80C interaction, the CENP-T-Mis12C interaction is regulated by Cdk1. Thr195 and Ser201 in human CENP-T are suggested as key phosphorylation sites by Cdk1 for the Mis12C interaction [19,51]. However, chicken DT40 cells are viable when we replace CENP-T WT with a CENP-T mutant, in which Thr184 of chicken CENP-T (corresponding to human CENP-T Ser201) is substituted to Ala [26], suggesting that the mutant CENP-T still binds to Mis12C. Considering this result, additional regulatory mechanisms may control the CENP-T-Mis12C interaction. The artificial tethering assays in which various CENP-T mutants are placed on a non-centromeric locus in human and chicken cells have shown that direct binding of Ndc80C to the CENP-T extreme N-terminus is required for the CENP-T-Mis12C interaction, suggesting that the direct binding of CENP-T to Ndc80C is an upstream event of Mis12C-recruitment onto the CENP-T-pathway [15,51]. Further study is needed to understand how this Mis12-recruitment is controlled by the CENP-T-Ndc80C interaction as well as phospho-regulations.

Our localization analyses demonstrated that a majority of Ndc80C localizes to the CENP-T-pathway, but less to Mis12C on the CENP-C-pathway in DT40 cells (Figure 3(c)) [26]. However, in vitro reconstitution studies for KMN demonstrated that Mis12C tightly associates with Ndc80C [17,38]. The in vitro and in vivo difference in the Mis12C-Ndc80C binding could also be attributed to phospho-regulation in cells. One of the interfaces for Ndc80C-binding of Mis12C is Dsn1, which is a member of Mis12C [21,22]. Dsn1 interacts with Ndc80C via its C-terminus whose sequence is similar to the Ndc80C-binding region of CENP-T [21]. As the Ndc80C-binding region of CENP-T has a consensus site for Cdk1-phosphorylation, there exists a Cdk1-phosphorylation site in the corresponding region of Dsn1 [21,26]. Interestingly, in contrast to CENP-T in which Cdk1 phosphorylation positively regulates its Ndc80C interaction, Cdk1 phosphorylation in Dsn1 decreases its affinity to Ndc80C [26]. Furthermore, a CENP-T mutant whose Ndc80C-binding region is swapped with that of Dsn1 does not rescue the CENP-T-deficient phenotype, but the mutant with a phospho-dead mutation in Dsn1 sequence does, suggesting that phosphorylation in the Dsn1 C-terminus negatively regulates its Ndc80C interaction [26]. Mis12C has another Ndc80C–binding interface, which is the PVIHL motif in Nsl1 of Mis12C [38]. The PVIHL motif is required, but not sufficient, for tight interaction between Mis12C and Ndc80C [38]. Multivalent Ndc80C-binding interfaces in Mis12C may contribute to tight binding of Mis12C to Ndc80C, and presumably, the lack of one of the interfaces is enough to disrupt the interaction. In contrast to Dsn1 phosphorylation by Cdk1, CENP-T phosphorylation strengthens the CENP-T-Ndc80C interaction [16,17,19], so that a majority of Ndc80C localizes to the CENP-T-pathway in mitotic cells.

Even though only small populations of Ndc80C bind to Mis12C in mitotic cells, the Mis12C–Ndc80C interaction is essential, because deletion of the Ndc80C-binding region of Dsn1 is lethal in chicken DT40 cells [26]. Although one explanation for this observation could be the importance of multicopy recruitment of Ndc80C on CENP-T [56], which might help tracking depolymerizing microtubules, further investigation on this issue is necessary.

Rerouting the pathway for making a linkage between the centromere and microtubules in evolution

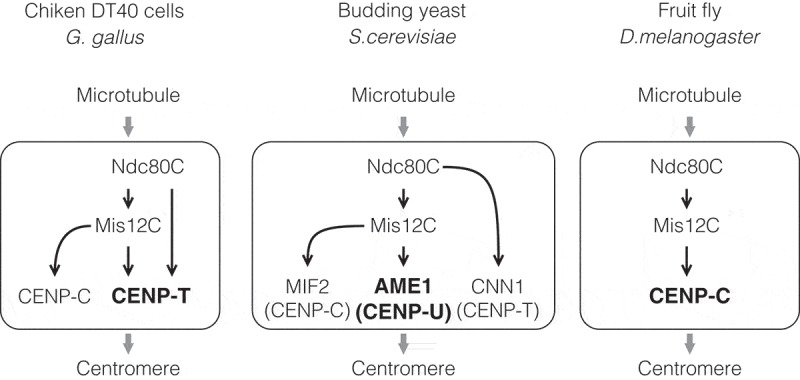

The vertebrate kinetochore has both the CENP-C- and CENP-T-pathways for forming a bridge between the centromere and microtubules [15,16,32,54,65], and we propose that CENP-T forms a major pathway in chicken cells (Figure 5) [26]. Given the results of studies on copy numbers and precise localization of kinetochore proteins in human cells [27,28], it is possible that the CENP-T-pathway is also the major pathway in human cells. Both CENP-C and CENP-T are conserved in yeasts: CNN1 and MIF2 are homologs of CENP-T and CENP-C, respectively, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [66]. In contrast to vertebrate CENP-T, CNN1 is a non-essential for cell viability [67]. Although MIF2 is essential for cell viability, the Mis12C (MIND-complex in the yeast)-binding domain of MIF2 is dispensable for chromosome segregation [49,68]. In addition to the CENP-C- and CENP-T-pathways, S. cerevisiae has a third pathway mediated by AME1, which forms the COMA (CTF19, OKP1, MCM21, and AME1; vertebrate orthologs of CENP-P, CENP-Q, CENP-O, and CENP-U, respectively) complex, is essential for cell viability [68,69]. AME1 forms a complex with OKP1 and binds to Mis12C and CSE4 (a CENP-A homolog) [68,70]. AME1 has the Mis12C-binding domain in its N-terminus, and its deletion causes cell lethality [68], suggesting that S. cerevisiae has three pathways for making a linkage between the centromere and a microtubule, and the AME1-pathway is the main pathway. In vertebrates, CENP-U also forms a complex with CENP-P, CENP-Q, and CENP-O as well as an additional subunit CENP-R [65,71]. In contrast to the yeast ortholog, CENP-U and its interacting proteins are dispensable for cell proliferation in chicken DT40 cells [71–73]. Nevertheless, the CENP-OPQRU complex directly binds to microtubules via CENP-Q, which might help microtubule-binding of Ndc80C [65], consequently contributing to chromosome alignment and recovery from the spindle damage in vertebrates [65,71,74].

Figure 5.

Divergence among species of pathways for linkage between centromere and microtubules. The major linkage pathway is varied among species. Vertebrates have two pathways for linking between the centromere and microtubules: CENP-C- and CENP-T-pathways, and the CENP-T-pathway is the major pathway in chicken (Gallus gallus) DT40 cells. There are three pathways in the budding yeast (S. cerevisiae): MIF2 (a CENP-C homolog)-, CNN1 (a CENP-T homolog)- and AME1 (a CENP-U homolog)-pathways, and the AME1-pathway is the major pathway in the yeast. Since CENP-C is the only CCAN in the fruit fly (D. melanogaster), the CENP-C-pathway forms a key bridge between the centromere and microtubules in the species.

In contrast, Caenorhabditis elegans does not have CENP-T, but has CENP-C and CENP-C is the sole CCAN member in Drosophila melanogaster [25,44]; the CENP-C-pathway paves the way for making a linkage between the centromere and microtubules in these organisms. Drosophila CENP-C seems to co-evolve with the Mis12C, which consists Mis12, Nsl1 (also called Kmn1) and either one of two Nnf1 paralogs (Nnf1a and Nnf1b). Dsn1, which is a component of the Mis12C in yeasts and vertebrates, is not identified in Drosophila [75]. Furthermore, KNL1 ortholog Spc105R sequence is shorter than that of vertebrate KNL1 and its binding protein Zwint is not found in Drosophila [75,76]. These evolutionary changes may enable the sole CENP-C pathway to bind to KMN tightly enough and to fulfill other kinetochore functions, including SAC. Interestingly, several species have CENP-T, but not CENP-C, homolog [25]. In addition, any CCAN components are not found in kinetoplastids [25,44,77].

Comparative genomics studies suggest evolutionary flexibility of the kinetochore protein network [24,25,44]. One possible scenario in an evolutionary perspective may be that the CENP-C-pathway is an ancestral pathway, given that CENP-C is widely found in eukaryotic supergroups [25,44]. It may also be possible that the CENP-T-pathway is ancestral, since CENP-T is found in a lineage of the Stramenopila-Alveolata-Rhizaria supergroup as well as in several organisms in Opisthokonta [25]. Presumably, a power balance between the CENP-C- and CENP-T-pathways is fluctuating. During evolutionary history, if the balance is tipped towards the CENP-C-pathway, the CENP-T-pathway becomes weak and could even be lost, like in D. melanogaster and C. elegans. Contrastingly, if the CENP-T-pathway takes power, CENP-C could be dispensable. In the kinetochore of vertebrate cells, although both pathways still exist, the balance appears to lean towards the CENP-T-pathway [26]. Some species like S. cerevisiae have acquired and utilized another pathway in CCAN as a major KMN scaffold together with the CENP-C- and CENP-T-pathways [68]. Kinetoplastids seem to have found a completely different way for making a linkage between the centromere and microtubules [77]. Because of this, they may potentially lose not only CCAN but also KMN [25,44]. The evolutionary flexibility of the kinetochore protein network potentially drives the divergence of pathways making a linkage from the centromere to spindle microtubules.

Conclusions

The kinetochore provides bridges between the centromere and the spindle microtubules and sustains the tension applied from the microtubules. The CCAN–KMN interaction in the kinetochore is dynamic during mitotic progression in vertebrate cells, and multiple phosphorylations within CCAN and KMN by mitotic kinases regulate these dynamics [26]. Such phosphorylations make the CENP-T-pathway the major KMN-binding scaffold in vertebrates; therefore, the Mis12C-CENP-C interaction is dispensable for cell viability [26]. However, considering that the Mis12C-binding region of CENP-C is well conserved among species, and binds to Mis12C tightly in vitro [21,22], it is unlikely that the Mis12C-CENP-C interaction is completely dispensable in vertebrates. This interaction is regulated by AurB activity [21,22,51,63,64], and it has been shown that AurB activity at the centromere is different between transformed and non-transformed cells [78–80], suggesting that the CENP-C-pathway may be important for helping the CENP-T-pathway in some cell types. A recent study demonstrated that tissue architecture affects chromosome segregation fidelity [81]. Further studies on the two pathways, as well as other kinetochore regulations across diverse biological contexts, should bring us a more comprehensive understanding of the transmission of genetic information beyond generations.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, KAKENHI Grant Numbers 15H05972, 16H06279, and 17H06167 to TF, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, KAKENHI Grant Number 16K18491 to MH.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members in the Fukagawa lab for helpful discussions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].Cheeseman IM. The kinetochore. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014. July 1;6(7):a015826–a015826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Musacchio A, Desai A.. A molecular view of kinetochore assembly and function. Biology (Basel). 2017. January 24;6(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fukagawa T, Earnshaw WC. The centromere: chromatin foundation for the kinetochore machinery. Dev Cell. 2014. September 8;30(5):496–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Musacchio A. The molecular biology of spindle assembly checkpoint signaling dynamics. Curr Biol. 2015. October 19;25(20):R1002–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sacristan C, Kops GJPL. Joined at the hip: kinetochores, microtubules, and spindle assembly checkpoint signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2015. January;25(1):21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sarangapani KK, Asbury CL. Catch and release: how do kinetochores hook the right microtubules during mitosis? Trends Genet. 2014. April;30(4):150–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nagpal H, Fukagawa T. Kinetochore assembly and function through the cell cycle. Chromosoma. 2016. September;125(4):645–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pesenti ME, Weir JR, Musacchio A. Progress in the structural and functional characterization of kinetochores. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2016. April;37:152–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hara M, Fukagawa T. Critical foundation of the kinetochore: the constitutive centromere-associated network (CCAN). Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2017;56:29–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].McKinley KL, Cheeseman IM. The molecular basis for centromere identity and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016. January;17(1):16–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Black BE, Cleveland DW. Epigenetic centromere propagation and the nature of CENP-a nucleosomes. Cell. 2011. February 18;144(4):471–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Varma D, Salmon ED. The KMN protein network – chief conductors of the kinetochore orchestra. J Cell Sci. 2012. December 15;125(24):5927–5936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kline SL, Cheeseman IM, Hori T, et al. The human Mis12 complex is required for kinetochore assembly and proper chromosome segregation. J Cell Biol. 2006. April 10;173(1):9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cheeseman IM, Hori T, Fukagawa T, et al. KNL1 and the CENP-H/I/K complex coordinately direct kinetochore assembly in vertebrates. Mol Biol Cell. 2008. February;19(2):587–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hori T, Shang W-H, Takeuchi K, et al. The CCAN recruits CENP-A to the centromere and forms the structural core for kinetochore assembly. J Cell Biol. 2013. January 7;200(1):45–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gascoigne KE, Takeuchi K, Suzuki A, et al. Induced ectopic kinetochore assembly bypasses the requirement for CENP-A nucleosomes. Cell. 2011. April 29;145(3):410–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Nishino T, Rago F, Hori T, et al. CENP‐T provides a structural platform for outer kinetochore assembly. EMBO J. 2013. February 6;32(3):424–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Screpanti E, De Antoni A, Alushin GM, et al. Direct binding of Cenp-C to the Mis12 complex joins the inner and outer kinetochore. Curr Biol. 2011. March 8;21(5):391–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Huis in ‘t Veld PJ, Jeganathan S, Petrovic A, et al. Molecular basis of outer kinetochore assembly on CENP-T. Elife. 2016. December;24:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Przewloka MR, Venkei Z, Bolanos-Garcia VM, et al. CENP-C is a structural platform for kinetochore assembly. Curr Biol. 2011. March 8;21(5):399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Petrovic A, Keller J, Liu Y, et al. Structure of the MIS12 complex and molecular basis of its interaction with CENP-C at human kinetochores. Cell. 2016. November 3;167(4):1028–1040.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Dimitrova YN, Jenni S, Valverde R, et al. Structure of the MIND Complex Defines a Regulatory Focus for Yeast Kinetochore Assembly. Cell. 2016. November;167(4):1014–1027.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zhou X, Zheng F, Wang C, et al. Phosphorylation of CENP-C by Aurora B facilitates kinetochore attachment error correction in mitosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017. December 12;114(50):E10667–E10676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Drinnenberg IA, Henikoff S, Malik HS. Evolutionary turnover of kinetochore proteins: a ship of theseus? Trends Cell Biol. 2016. July;26(7):498–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].van Hooff JJ, Tromer E, van Wijk LM, et al. Evolutionary dynamics of the kinetochore network in eukaryotes as revealed by comparative genomics. EMBO Rep. 2017. September 1;18(9):1559–1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hara M, Ariyoshi M, Okumura E-I, et al. Multiple phosphorylations control recruitment of the KMN network onto kinetochores. Nat Cell Biol. 2018. December;20(12):1378–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Suzuki A, Badger BL, Salmon ED. A quantitative description of Ndc80 complex linkage to human kinetochores. Nat Commun. 2015. September 8;6:8161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Suzuki A, Badger BL, Wan X, et al. The architecture of CCAN proteins creates a structural integrity to resist spindle forces and achieve proper Intrakinetochore stretch. Dev Cell. 2014. September 29;30(6):717–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Fukagawa T. Critical histone post-translational modifications for centromere function and propagation. Cell Cycle. 2017. July 3;16(13):1259–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Srivastava S, Zasadzińska E, Foltz DR. Posttranslational mechanisms controlling centromere function and assembly. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2018. June;52:126–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Carroll CW, Milks KJ, Straight AF. Dual recognition of CENP-A nucleosomes is required for centromere assembly. J Cell Biol. 2010. June 28;189(7):1143–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Weir JR, Faesen AC, Klare K, et al. Insights from biochemical reconstitution into the architecture of human kinetochores. Nature. 2016. August 31;537(7619):249–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kato H, Jiang J, Zhou B-R, et al. A conserved mechanism for centromeric nucleosome recognition by centromere protein CENP-C. Science. 2013. May 31;340(6136):1110–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Pentakota S, Zhou K, Smith C, et al. Decoding the centromeric nucleosome through CENP-N. Elife. 2017. December;27(6):213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chittori S, Hong J, Saunders H, et al. Structural mechanisms of centromeric nucleosome recognition by the kinetochore protein CENP-N. Science. 2018. January 19;359(6373):339–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Tian T, Li X, Liu Y, et al. Molecular basis for CENP-N recognition of CENP-A nucleosome on the human kinetochore. Cell Res. 2018. March;28(3):374–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ciferri C, Musacchio A, Petrovic A. The Ndc80 complex: hub of kinetochore activity. FEBS Lett. 2007. June 19;581(15):2862–2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Petrovic A, Pasqualato S, Dube P, et al. The MIS12 complex is a protein interaction hub for outer kinetochore assembly. J Cell Biol. 2010. September 6;190(5):835–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Monda JK, Cheeseman IM. The kinetochore-microtubule interface at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2018. August 16;131(16):jcs214577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Hori T, Amano M, Suzuki A, et al. CCAN makes multiple contacts with centromeric DNA to provide distinct pathways to the outer kinetochore. Cell. 2008. December 12;135(6):1039–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Takeuchi K, Nishino T, Mayanagi K, et al. The centromeric nucleosome-like CENP-T-W-S-X complex induces positive supercoils into DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014. February;42(3):1644–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Moroi Y, Peebles C, Fritzler MJ, et al. Autoantibody to centromere (kinetochore) in scleroderma sera. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980. March;77(3):1627–1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Earnshaw WC, Rothfield N. Identification of a family of human centromere proteins using autoimmune sera from patients with scleroderma. Chromosoma. 1985;91(3–4):313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Drinnenberg IA, Akiyoshi B. Evolutionary Lessons from Species with Unique Kinetochores. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2017;56:111–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Klare K, Weir JR, Basilico F, et al. CENP-C is a blueprint for constitutive centromere-associated network assembly within human kinetochores. J Cell Biol. 2015. July 6;210(1):11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].McKinley KL, Sekulic N, Guo LY, et al. The CENP-L-N complex forms a critical node in an integrated meshwork of interactions at the centromere-kinetochore interface. Mol Cell. 2015. December 17;60(6):886–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Guo LY, Allu PK, Zandarashvili L, et al. Centromeres are maintained by fastening CENP-A to DNA and directing an arginine anchor-dependent nucleosome transition. Nat Commun. 2017. June;9(8):15775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Trazzi S, Perini G, Bernardoni R, et al. The C-terminal domain of CENP-C displays multiple and critical functions for mammalian centromere formation. PLoS ONE. 2009. June 8;4(6):e5832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Cohen RL, Espelin CW, De Wulf P, et al. Structural and functional dissection of Mif2p, a conserved DNA-binding kinetochore protein. Mol Biol Cell. 2008. October;19(10):4480–4491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Milks KJ, Moree B, Straight AF. Dissection of CENP-C-directed centromere and kinetochore assembly. Mol Biol Cell. 2009. October;20(19):4246–4255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Rago F, Gascoigne KE, Cheeseman IM. Distinct organization and regulation of the outer kinetochore KMN network downstream of CENP-C and CENP-T. Curr Biol. 2015. March 2;25(5):671–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Foltz DR, Jansen LET, Black BE, et al. The human CENP-A centromeric nucleosome-associated complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2006. April 16;8(5):458–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Izuta H, Ikeno M, Suzuki N, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the ICEN (Interphase Centromere Complex) components enriched in the CENP-A chromatin of human cells. Genes Cells. 2006. June;11(6):673–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Nishino T, Takeuchi K, Gascoigne KE, et al. CENP-T-W-S-X forms a unique centromeric chromatin structure with a histone-like fold. Cell. 2012. February;148(3):487–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Malvezzi F, Litos G, Schleiffer A, et al. A structural basis for kinetochore recruitment of the Ndc80 complex via two distinct centromere receptors. EMBO J. 2013. February 6;32(3):409–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Volkov VA, Huis in ‘t Veld PJ, Dogterom M, et al. Multivalency of NDC80 in the outer kinetochore is essential to track shortening microtubules and generate forces. Elife. 2018. April;9(7):576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Gascoigne KE, Cheeseman IM. CDK-dependent phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion coordinately control kinetochore assembly state. J Cell Biol. 2013. April 1;201(1):23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hara M, Fukagawa T. Kinetochore assembly and disassembly during mitotic entry and exit. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2018. February;21(52):73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Krenn V, Musacchio A. The aurora B kinase in chromosome bi-orientation and spindle checkpoint signaling. Front Oncol. 2015;5:225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Lampson MA, Cheeseman IM. Sensing centromere tension: aurora B and the regulation of kinetochore function. Trends Cell Biol. 2011. March;21(3):133–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Liu D, Vleugel M, Backer CB, et al. Regulated targeting of protein phosphatase 1 to the outer kinetochore by KNL1 opposes Aurora B kinase. J Cell Biol. 2010. March 22;188(6):809–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Emanuele MJ, Lan W, Jwa M, et al. Aurora B kinase and protein phosphatase 1 have opposing roles in modulating kinetochore assembly. J Cell Biol. 2008. April 21;181(2):241–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Welburn JPI, Vleugel M, Liu D, et al. Aurora B phosphorylates spatially distinct targets to differentially regulate the kinetochore-microtubule interface. Mol Cell. 2010. May 14;38(3):383–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kim S, Yu H. Multiple assembly mechanisms anchor the KMN spindle checkpoint platform at human mitotic kinetochores. J Cell Biol. 2015. January 19;208(2):181–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Pesenti ME, Prumbaum D, Auckland P, et al. Reconstitution of a 26-subunit human kinetochore reveals cooperative microtubule binding by CENP-OPQUR and NDC80. Mol Cell. 2018. September 20;71(6):923–939.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Westermann S, Schleiffer A. Family matters: structural and functional conservation of centromere-associated proteins from yeast to humans. Trends Cell Biol. 2013. June;23(6):260–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Bock LJ, Pagliuca C, Kobayashi N, et al. Cnn1 inhibits the interactions between the KMN complexes of the yeast kinetochore. Nat Cell Biol. 2012. June;14(6):614–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Hornung P, Troc P, Malvezzi F, et al. A cooperative mechanism drives budding yeast kinetochore assembly downstream of CENP-A. J Cell Biol. 2014. August 18;206(4):509–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Pot I, Knockleby J, Aneliunas V, et al. Spindle checkpoint maintenance requires Ame1 and Okp1. Cell Cycle. 2005. October;4(10):1448–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Anedchenko EA, Samel-Pommerencke A, Tran Nguyen TM, et al. The kinetochore module Okp1CENP-Q/Ame1CENP-U is a reader for N-terminal modifications on the centromeric histone Cse4CENP-A. EMBO J. 2019. January 3;38(1):e98991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Hori T, Okada M, Maenaka K, et al. CENP-O class proteins form a stable complex and are required for proper kinetochore function. Mol Biol Cell. 2008. March;19(3):843–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Okada M, Cheeseman IM, Hori T, et al. The CENP-H-I complex is required for the efficient incorporation of newly synthesized CENP-A into centromeres. Nat Cell Biol. 2006. May;8(5):446–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Kagawa N, Hori T, Hoki Y, et al. The CENP-O complex requirement varies among different cell types. Chromosome Res. 2014. September;22(3):293–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Minoshima Y, Hori T, Okada M, et al. The constitutive centromere component CENP-50 is required for recovery from spindle damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2005. December;25(23):10315–10328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Liu Y, Petrovic A, Rombaut P, et al. Insights from the reconstitution of the divergent outer kinetochore of Drosophila melanogaster. Open Biol. 2016. February;6(2):150236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Richter MM, Poznanski J, Zdziarska A, et al. Network of protein interactions within the Drosophila inner kinetochore. Open Biol. 2016. February;6(2):150238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Akiyoshi B. The unconventional kinetoplastid kinetochore: from discovery toward functional understanding. Biochem Soc Trans. 2016. October 15;44(5):1201–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Abe Y, Sako K, Takagaki K, et al. HP1-assisted aurora B kinase activity prevents chromosome segregation errors. Dev Cell. 2016. March 7;36(5):487–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Abe Y, Hirota T. System-level deficiencies in Aurora B control in cancers. Cell Cycle. 2016. August 17;15(16):2091–2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Huang H, Lampson M, Efimov A, et al. Chromosome instability in tumor cells due to defects in Aurora B mediated error correction at kinetochores. Cell Cycle. 2018;17(23):2622–2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Knouse KA, Lopez KE, Bachofner M, et al. Chromosome segregation fidelity in epithelia requires tissue architecture. Cell. 2018. September 20;175(1):200–211.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]