Abstract

The role of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling in cancer is well-known in the context of angiogenesis but is also important in the functional regulation of tumor cells themselves. Notably, autocrine VEGF signaling mediated by its co-receptors called neuropilins (NRPs) appears be essential for sustaining the proliferation and survival of cancer stem cells (CSCs), which are implicated in mediating tumor growth, progression and drug resistance. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms involved in VEGF-mediated support of CSCs is critical to successfully treating cancer patients. The expression of the Hippo effector TAZ is associated with breast CSCs and has been shown to confer stem cell-like properties. We found that VEGF-NRP2 signaling contributes to the activation of TAZ in various breast cancer cells, which mediates a positive feedback loop that promotes mammosphere formation. VEGF-NRP2 signaling activated the GTPase Rac1, which inhibited the Hippo kinase LATS, which enabled the activity of TAZ. In complex with the transcription factor TEAD, TAZ then bound and repressed the promoter of the gene encoding the Rac GTPase-activating protein (Rac GAP) β2-chimaerin. By activating GTP hydrolysis, Rac GAPs effectively turn off Rac signaling; hence, TAZ-mediated repression of β2-chimaerin sustained Rac1 activity in CSCs. Depletion of β2-chimaerin in non-CSCs increased Rac1 activity, TAZ abundance and mammosphere formation. Analysis of a breast cancer patient database revealed an inverse correlation between β2-chimaerin and TAZ expression in tumors. Our findings highlight an unexpected role for β2-chimaerin in a feedforward loop of TAZ activation and the acquisition of CSC properties.

Introduction

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was originally characterized as a protein that promotes endothelial growth (1) and increases vascular permeability (2). For these and other reasons, it was presumed that the role of VEGF in cancer was limited to angiogenesis (1, 3–5). It is evident now, however, that there are angiogenesis-independent functions of VEGF in cancer that are mediated by specific receptors. Tumor cells express VEGF receptor tyrosine kinases (VEGFR1 and VEGFR2) and neuropilins (NRPs), another family of VEGF receptors. NRP1 and NRP2 were identified initially as neuronal receptors for semaphorins, which are axon guidance factors that function primarily in the developing nervous system (6). The finding that NRPs can also function as VEGF receptors and that they are expressed on endothelial and tumor cells launched studies aimed at understanding their contribution to angiogenesis and tumor biology (7). NRPs have the ability to interact with and modulate the function of VEGFR1 and VEGFR2, as well as other receptors (8–10). There is also evidence that NRPs are valid targets for therapeutic inhibition of angiogenesis and cancer (11–14).

A surge of evidence has implicated autocrine VEGF signaling mediated by NRPs in the function of cancer stem cells (CSCs), a sub-population of cells that function in tumor initiation, the differentiation of multi-lineage cancer cell hierarchies, therapy resistance and metastasis (12, 15–21). These observations have led to intense investigation into the mechanisms by which VEGF sustains CSCs and how these processes can be exploited therapeutically. Previously, we reported that NRP2 is highly expressed in breast CSCs and that VEGF-NRP2 signaling contributes to breast tumor initiation (22). A key issue that emerges from these findings is the mechanism by which VEGF-NRP2 signaling contributes to the function of CSCs. In pursuit of this issue, we were intrigued by reports that the Hippo pathway transducer TAZ confers stem cell properties and contributes to breast tumorigenesis, especially in high-grade tumors, which are distinguished by high NRP2 expression and VEGF-NRP2 signaling activity (22). Moreover, TAZ expression in breast cancer correlates with tumor grade (23) and high-grade tumors harbor a higher frequency of CSCs than do lower grade tumors (24). Mechanistic studies have shown that TAZ can induce an epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) in mammary epithelial cells (25), a process that can increase stem cell properties (26). Moreover, TAZ is necessary for the self-renewal of CSCs (23). In contrast, the role of YAP in breast cancer is less clear and its expression does not correlate with clinical outcome (27).

The Hippo pathway consists of core kinases and regulatory molecules that facilitate TAZ phosphorylation, cytoplasmic retention and inactivation (28–30). For this reason, identifying upstream receptors that disrupt Hippo signaling and, consequently, enhance TAZ activity is critical for understanding how these effectors contribute to the function of CSCs. In this study, we discovered that VEGF-NRP2 signaling contributes to increased TAZ activity by a Rac1-dependent, feed-forward mechanism.

Results

VEGF-NRP2 Signaling Contributes to TAZ Activation:

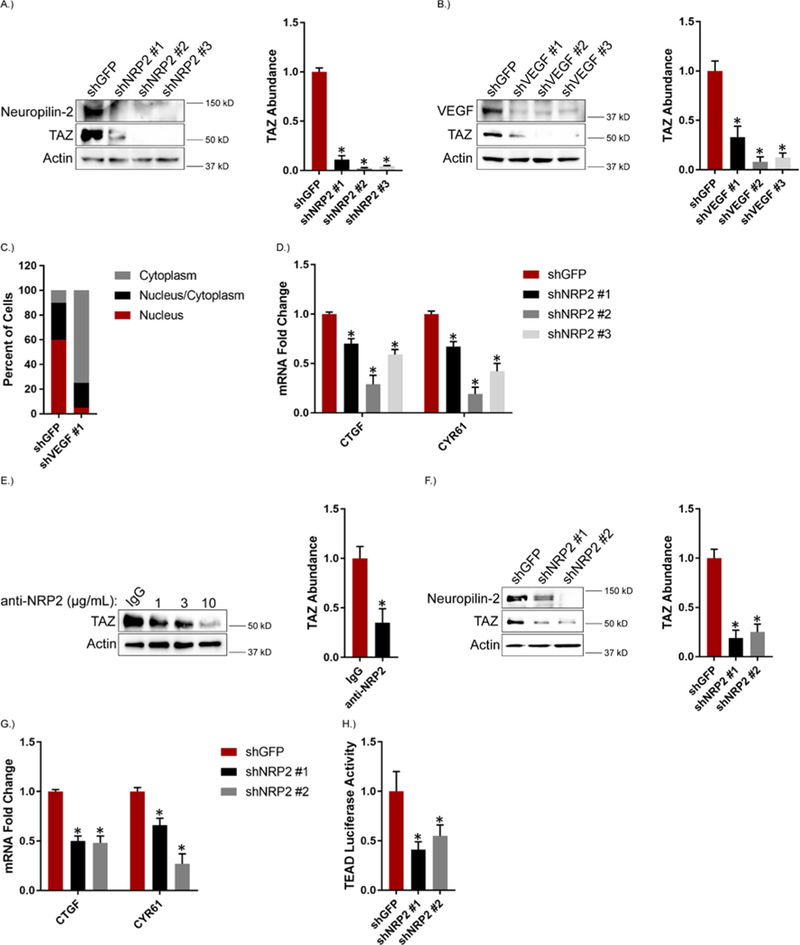

Initially, we assessed the contribution of VEGF-NRP2 signaling to TAZ activation. For this purpose, we used an inducible system to transform MCF10A cells with Src, which generates a population of CD44high/CD24low cells with CSC properties (31). This population is actually comprised of distinct epithelial (EPTH) and mesenchymal (MES) populations that differ in TAZ activity and tumor initiating potential. The MES population has enhanced TAZ activity, self-renewal potential and tumor initiating capability compared to the EPTH population (32). Importantly, MES cells express increased levels of VEGF and NRP2 compared to EPTH cells and are dependent on VEGF-NRP2 signaling for self-renewal (33). Expression of either NRP2 (Figure 1A) or VEGF (Figure 1B) was diminished in MES cells using shRNAs, which resulted in decreased TAZ abundance compared to control cells as assessed by immunoblotting (Figures 1, A and B). As reported previously, TAZ abundance is an indicator of its activation status (34, 35), as well as its nuclear localization. For this latter reason, we compared TAZ localization in control cells to VEGF- and NRP2-depleted cells by immunofluorescence (Figure 1C; fig. S1A). TAZ is localized primarily in the nucleus in control MES cells (Figure 1C; fig. S1A). In contrast, little, if any, TAZ was detected in VEGF- and NRP2-depleted cells, which is consistent with our immunoblotting data (Figures 1, A and B). The TAZ that was detected in VEGF-depleted cells is localized in the cytoplasm (Figure 1C; fig. S1A).

Figure 1: VEGF-NRP2 Signaling Contributes to TAZ Activation.

Expression of NRP2 (A) and VEGF (B) was diminished in MES cells and the impact on TAZ abundance was quantified by immunoblotting. Representative blots are shown. Densitometric values were processed using ImageJ and are provided as bar graphs (mean ± SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates. C.) TAZ localization (cytoplasm, nucleus/cytoplasm and nucleus) in control and VEGF-depleted MES cells was determined by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. Data are mean of n = 3 biological replicates. D.) mRNA expression of the indicated TAZ target genes was quantified by qPCR in NRP2-depleted MES cells. Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. E.) MES cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of a function-blocking NRP2 antibody for 6 hours and the impact on TAZ abundance was quantified by immunoblotting. Representative blots are shown. Densitometric values are provided as bar graphs (mean ± SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates of MES cells treated with 3 μg/mL of the NRP2 function-blocking antibody. F.) NRP2 expression was diminished in MDA-MB-231 cells and the impact on TAZ abundance was quantified by immunoblotting. Representative blots are shown. Densitometric values are provided as bar graphs (mean ± SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates. G.) mRNA expression of the indicated TAZ target genes was quantified by qPCR in NRP2-depleted MDA-MB-231 cells. Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. H.) NRP2-depleted MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with an 8XGTIIC-luciferase reporter construct and assayed for TEAD transcriptional activity. Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. * p ≤ 0.05 by two-tailed t test.

Depletion of NRP2 in MES cells also reduced the mRNA expression of the TAZ target genes CTGF and CYR61 (Figure 1D). To substantiate the data obtained with shRNAs, we treated MES cells with a function-blocking NRP2 antibody (11) and observed a concentration -dependent decrease in TAZ abundance (Figure 1E). Although similar results were obtained with YAP (fig. S1B–C), we focused subsequent experiments on TAZ because convincing data correlating YAP expression and clinical parameters in breast cancer are lacking (27).

We extended this analysis to MDA-MB-231 cells because they exhibit mesenchymal properties and highly express VEGF and NRP2 (33). Similar to MES cells, NRP2 depletion reduced the abundance of TAZ, as well as TAZ target genes, (Figures 1, F and G) suggesting that NRP2 affects TAZ-mediated transcription. TAZ regulates gene expression by associating with the TEAD family of transcription factors (36), which infers that NRP2 should affect TEAD transcriptional activity. Indeed, the activity of a TEAD luciferase reporter was reduced significantly in MDA-MB-231 cells with diminished NRP2 expression compared to control cells (Figure 1H).

Rac1 Facilitates VEGF-NRP2–mediated Activation of TAZ:

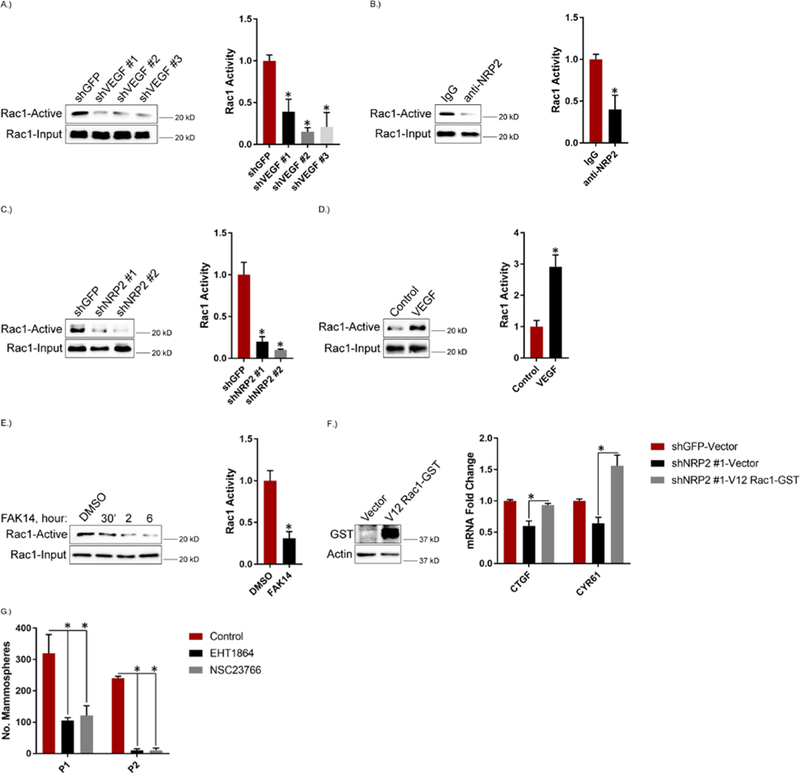

To investigate the mechanism by which VEGF-NRP2 signaling activates TAZ, we focused on Rac1 for several reasons. This GTPase is a major effector of NRP/plexin signaling in neurons (37, 38) and it has been implicated in VEGF signaling in endothelial cells (39, 40). Moreover, Rac1 has also been implicated in TAZ activation (35, 41–43). We observed that depleting VEGF expression or treating MES cells with the NRP2 function-blocking antibody resulted in a substantial decrease in Rac1 activity (Figures 2, A and B). Similar results were obtained with MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 2C). Conversely, stimulating MDA-MB-231 cells with VEGF resulted in an increase in Rac1 activity (Figure 2D).

Figure 2: VEGF-NRP2 Signaling Activates Rac1.

A.) Expression of VEGF was diminished in MES cells and the impact on Rac1 activity was assessed using a GST fusion protein containing the Rac/cdc42 binding domain of PAK (PBD). Representative blots are shown. Densitometric values are provided as bar graphs (mean ± SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates. B.) MES cells were treated with 3 μg/mL of a function blocking NRP2 antibody for 6 hours and assayed for Rac1 activity. Representative blots are shown. Densitometric values are provided as bar graphs (mean ± SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates. C.) NRP2 expression was diminished in MDA-MB-231 cells and the impact on Rac1 activity was assessed. Representative blots are shown. Densitometric values are provided as bar graphs (mean ± SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates. D.) MDA-MB-231 cells were serum-starved for 24 hours, treated with 50 ng/mL of VEGF for 30 minutes and assayed for Rac1 activity. Representative blots are shown. Densitometric values are provided as bar graphs (mean ± SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates. E.) MES cells were treated with 2 μM of FAK14 for the indicated time points and assayed for Rac1 activity. Representative blots are shown. Densitometric values are provided as bar graphs (mean ± SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates of MES cells treated with FAK14 for 6 hours. F.) NRP2 expression was diminished in MDA-MB-231 cells that were then transfected with constitutively active V12 Rac1-GST. GST expression was quantified by immunoblotting. mRNA expression of the indicated TAZ target genes was quantified by qPCR. Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. G.) MES cells were treated with 50 μM of the Rac inhibitors EHT1864 or NSC23766 and assayed for self-renewal by serial passage mammosphere formation (P1: passage 1; P2: passage 2). Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. * p ≤ 0.05 by two-tailed t test.

An important issue is whether VEGFRs contribute to Rac1 activation in breast cancer cells. Treatment of MDA-MB-231 cells with the VEGFR inhibitors pazopanib and subitinib in the presence of VEGF did not decrease Rac1 activity compared to VEGF alone (fig. S2), suggesting that VEGF-NRP2 activation of Rac1 is VEGFR-independent. This result is not surprising because we reported previously that MDA-MB-231 and other breast cancer cell lines express very low levels of VEGFRs (44). In contrast, VEGF-NRP2–mediated Rac1 activation appears to be focal adhesion kinase (FAK)-dependent, because the FAK inhibitor FAK14 significantly decreased Rac1 activity in MES cells (Figure 2E). This result is consistent with previous findings that FAK is a downstream effector of VEGF-NRP2 signaling (22), and it has been implicated in Rac1 activation (45–47), as well as Hippo pathway regulation (48, 49).

The results described above prompted us to evaluate whether VEGF-NRP2 signals through Rac1 to promote TAZ activation. Based on our finding that depletion of NRP2 in MDA-MB-231 cells decreased the expression of TAZ target genes (Figure 1G), we found that expression of a constitutively active V12 Rac1 in these cells rescued their expression (Figure 2F). This result provides evidence that the VEGF-NRP2-Rac1 axis contributes to TAZ activation. Subsequently, we assessed the role of Rac1 inhibition on mammosphere formation in MES cells and observed decreased mammosphere formation upon treatment with the Rac inhibitors EHT1864 and NSC23766 (Figure 2G).

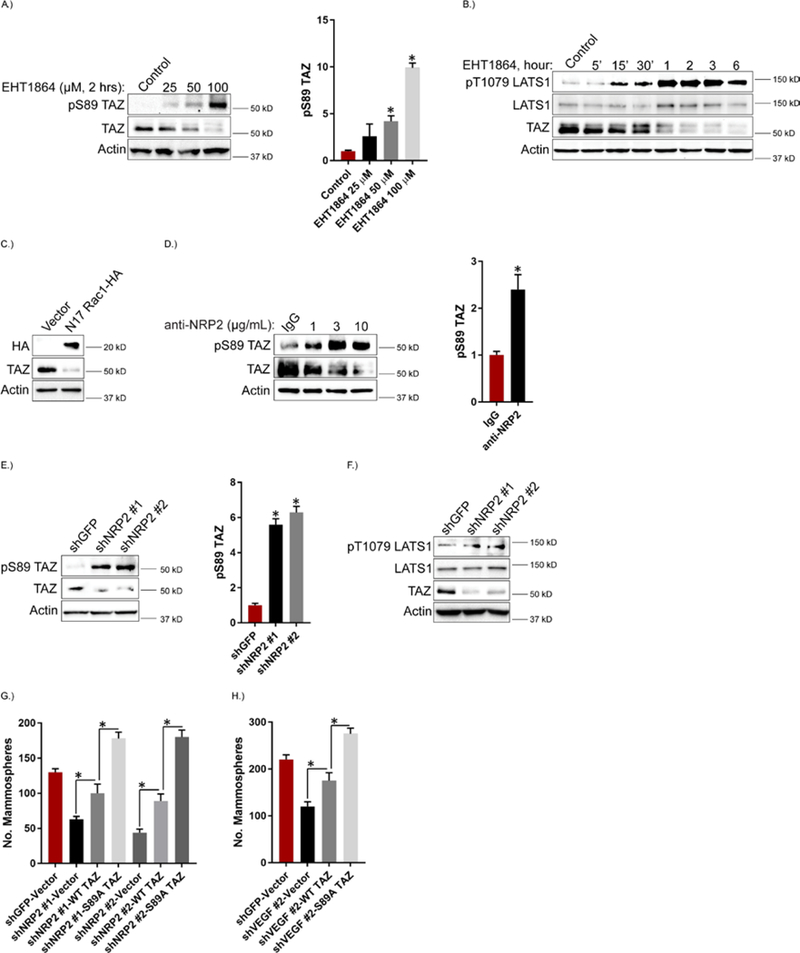

We next sought to investigate the mechanism by which VEGF-NRP2-mediated regulation of Rac1 contributes to TAZ activation. We focused on the LATS tumor suppressor kinases because they phosphorylate TAZ directly at the Ser89 position and promote its cytoplasmic retention and degradation when phosphorylated and activated on their hydrophobic motifs (Thr1079 in LATS1, Thr1041 in LATS2) (25, 50, 51). Moreover, LATS can be regulated by Rac1 (35, 41, 42). Treatment of MES cells with the Rac inhibitor EHT1864 resulted in a concentration-dependent increase in the abundance of phosphorylated Ser89 (pSer89) TAZ and a concomitant decrease in TAZ abundance (Figure 3A). It also increased the abundance of pThr1079 LATS1 and decreased TAZ abundance as early as 15 minutes after treatment, and this pattern persisted for up to 6 hours (Figure 3B). Expression of dominant-negative N17 Rac1 also decreased TAZ abundance in MES cells (Figure 3C). Similar results were obtained with the NRP2 function-blocking antibody (Figure 3D). NRP2 knockdown in MDA-MB-231 cells also increased the abundance of pSer89 TAZ and pThr1079 LATS1 and decreased the abundance of TAZ (Figures 3, E and F). NRP2 depletion also increased LATS-mediated YAP phosphorylation (pSer127) (fig. S1B). LATS knockdown rescued TAZ abundance in NRP2 depleted MDA-MB-231 cells, which shows that VEGF-NRP2-Rac1 regulation of TAZ is LATS-dependent (fig. S3A).

Figure 3: Rac1 Facilitates VEGF-NRP2 Activation of TAZ through Inhibition of LATS.

A.) MES cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of the Rac inhibitor EHT1864 for 2 hours and the impact on pSer89 TAZ and TAZ abundance was quantified by immunoblotting. Representative blots are shown. Densitometric values are provided as bar graphs (mean ± SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates. B.) MES cells were treated with the Rac inhibitor EHT1864 (100 μM), lysed at the indicated time points and the impact on pThr1079 LATS1, LATS1 and TAZ abundance was quantified by immunoblotting. Data are representative of n = 2 biological replicates. C.) MES cells were transfected with dominant negative N17 Rac1-HA and the impact on TAZ abundance was quantified by immunoblotting. Data are representative of n = 2 biological replicates. D.) MES cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of a function-blocking NRP2 antibody for 6 hours and the impact on pSer89 TAZ and TAZ abundance was quantified by immunoblotting. Representative blots are shown. Densitometric values are provided as bar graphs (mean ± SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates of MES cells treated with 3 μg/mL of the NRP2 function-blocking antibody. E.) NRP2 expression was diminished in MDA-MB-231 cells and the impact on pSer89 TAZ and TAZ abundance was quantified by immunoblotting. Representative blots are shown. Densitometric values are provided as bar graphs (mean ± SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates. F.) NRP2 expression was diminished in MDA-MB-231 cells and the impact on pThr1079 LATS1 and LATS1 was quantified by immunoblotting. Data are representative of n = 2 biological replicates. G.) NRP2-depleted MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with empty vector, wild-type TAZ or S89A TAZ and assayed for self-renewal by serial passage mammosphere formation. Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. H.) VEGF-depleted MES cells were transfected with empty vector, wild-type TAZ or S89A TAZ and assayed for self-renewal by serial passage mammosphere formation. Error bars indicate standard deviation from 3 technical replicates. Data are representative of n = 2 biological replicates. * p ≤ 0.05 by two-tailed t test.

Given the importance of TAZ in promoting CSC properties (23), we hypothesized that VEGF-NRP2-Rac1-mediated LATS inhibition is a critical upstream regulator of TAZ-mediated mammosphere formation. Depletion of NRP2 in MDA-MB-231 cells significantly reduced mammosphere formation, which was partially rescued by expression of wild-type TAZ (Figure 3G; fig. S4). Expression of S89A TAZ, which is resistant to LATS-mediated phosphorylation at that site, rescued mammosphere formation significantly more than did expression of wild-type TAZ (Figure 3G; fig. S4). Similar results were obtained by VEGF depletion in MES cells (Figure 3H). These results indicate that the wild-type TAZ ectopically expressed is subject to regulation by upstream VEGF-NRP2 signaling, but that the S89A TAZ mutant is not. Together, these data provide functional evidence that VEGF-NRP2-Rac1 promotes a TAZ-dependent stem-like phenotype through inhibition of LATS-mediated phosphorylation of TAZ at Ser89.

To gain insight into the mechanism by which VEGF-NRP2-Rac1 signaling inhibits LATS activity, we postulated that this signaling regulates Merlin, the protein product of the Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) gene, because phosphorylation of Merlin on Ser518 by p21-activated kinase (PAK) is inhibitory (52–54). Moreover, Merlin phosphorylation inhibits LATS phosphorylation (55). These findings are relevant because PAK is a Rac-activated kinase (56). Following these observations, we found that either Rac inhibition or NRP2 depletion in MES cells reduced the abundance of Ser518 -phosphorylated Merlin (fig. S3, B and C).

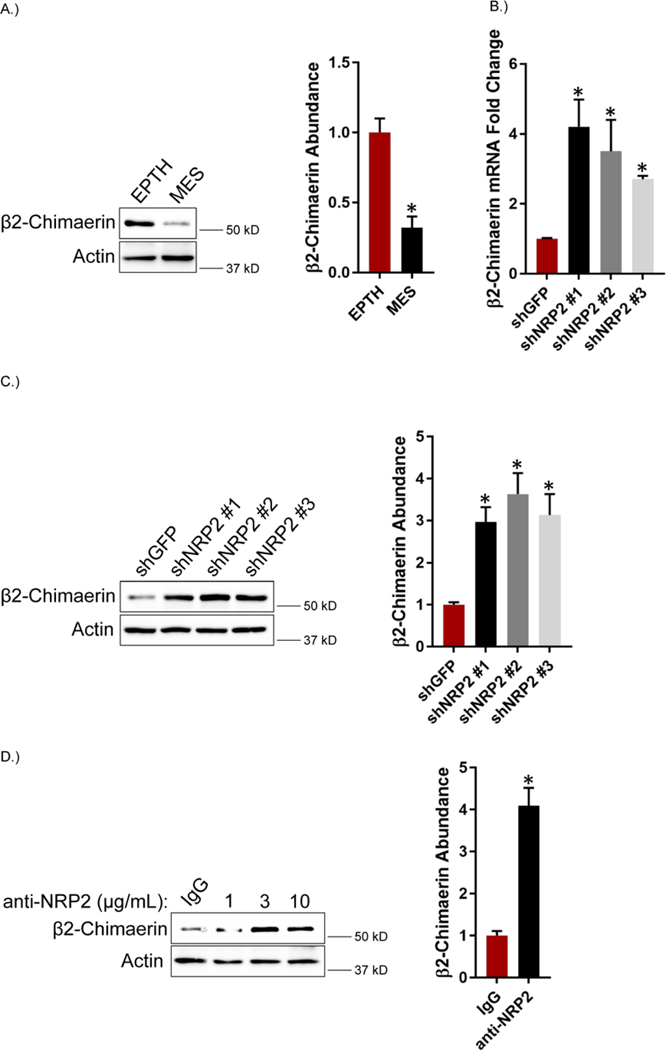

VEGF-NRP2 Signaling Represses the Rac GAP β2-chimaerin:

Rac1 cycles from GTP-bound active states to GDP-bound inactive states, which, in large part, is regulated by the expression of guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) and GAPs. Therefore, we profiled the expression of known Rac GEFs and GAPs in EPTH and MES cells (Table 1). Notably, we observed that the expression of the Rac GAP β2-chimaerin was markedly reduced in MES cells compared to EPTH cells (Table 1), which we verified by immunoblotting (Figure 4A). β2-chimaerin is a Rac-specific GAP that has been implicated as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer (57–61). Given that β2-chimaerin abundance is reduced in MES cells and these cells highly express VEGF and NRP2 (33), we assessed whether VEGF-NRP2 signaling repressed β2-chimaerin expression. Indeed, we observed that NRP2 depletion increased β2-chimaerin mRNA and protein expression in MES cells (Figures 4, B and C). Treatment of MES cells with the NRP2 function-blocking antibody also increased β2-chimaerin abundance (Figure 4D). These observations provide evidence that VEGF-NRP2 signaling represses β2-chimaerin expression.

Table 1: mRNA screen of Rac GEFs and GAPs in EPTH and MES cells.

The expression of the indicated Rac GEFs and GAPs was compared in EPTH and MES cells using qPCR. Table 1 shows fold change in mRNA expression upon normalization with EPTH cells, which was set as 1. NE indicates not expressed. Numbers in parentheses indicate standard deviation.

| EPTH | MES | |

|---|---|---|

| GEFs | ||

| PRex1 | NE | NE |

| PRex2 | NE | NE |

| Tiam1 | 1 (0.13) | 0.52 (0.04) |

| Tiam2 | NE | NE |

| SOS1 | 1 (0.01) | 0.62 (0.04) |

| ARHGEF7 | 1 (0.08) | 1.1 (0.01) |

| Dock1 | 1 (0.08) | 0.56 (0.13) |

| VAV1 | NE | NE |

| VAV2 | 1 (0.07) | 0.63 (0.02) |

| VAV3 | 1 (0.1) | 0.69 (0.17) |

| Trio | 1 (0.05) | 0.76 (0.02) |

| GAPs | ||

| β2-chimaerin | 1 (0.08) | 0.16 (0.07) |

| ARHGAP10 | 1 (0.05) | 0.7 (0.05) |

Figure 4: VEGF-NRP2 Signaling Represses the Rac GAP β2-chimaerin.

A.) Abundance of β2-chimaerin was quantified by immunoblotting in EPTH and MES cells. Representative blots are shown. Densitometric values are provided as bar graphs (mean ± SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates. B.) Expression of NRP2 was diminished in MES cells and β2-chimaerin mRNA expression was quantified by qPCR. Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. C.) β2-chimaerin abundance was quantified by immunoblotting in NRP2-depleted MES cells. Representative blots are shown. Densitometric values are provided as bar graphs (mean ± SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates. D.) MES cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of a function blocking NRP2 antibody for 6 hours and abundance of β2-chimaerin was quantified by immunoblotting. Representative blots are shown. Densitometric values are provided as bar graphs (mean ± SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates of MES cells treated with 3 μg/mL of the NRP2 function-blocking antibody. * p ≤ 0.05 by two-tailed t test.

TAZ Activates Rac1 by Repressing β2-chimaerin through a TEAD-Dependent Mechanism:

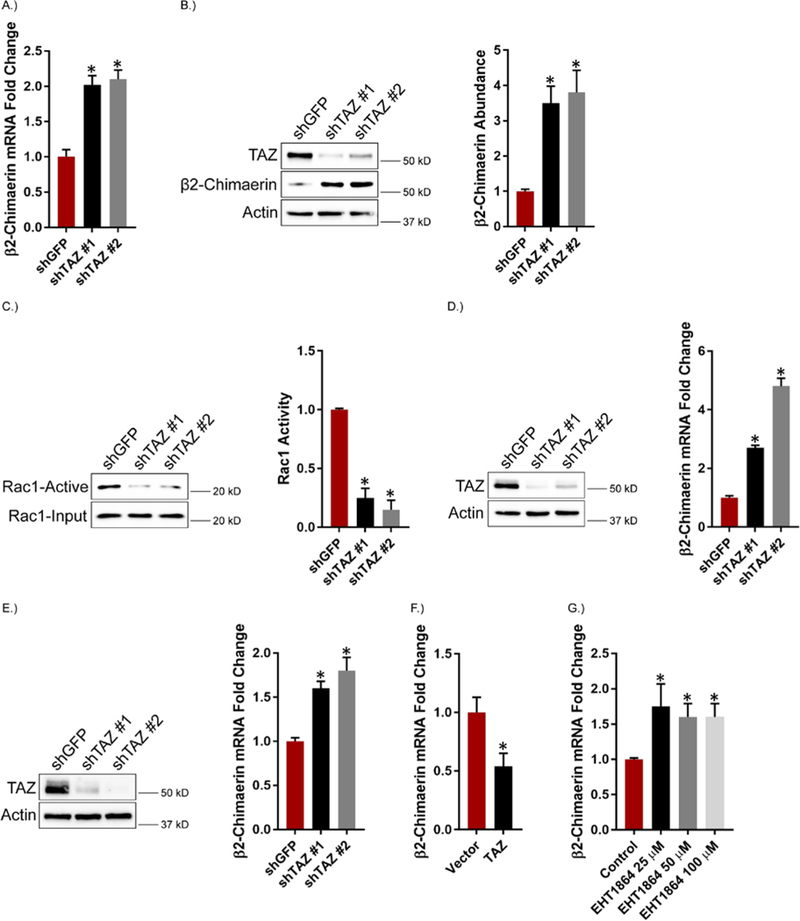

Based on our observation that VEGF-NRP2 signaling activates TAZ and represses β2-chimaerin, we assessed the possibility that TAZ represses β2-chimaerin. This possibility is supported by studies demonstrating that TAZ can function in transcriptional repression (62, 63). Depletion of TAZ in MES cells caused an increase in β2-chimaerin mRNA and protein expression and a consequent decrease in Rac1 activity (Figures 5, A to C). TAZ knockdown in MDA-MB-435 cells (Figure 5D) and MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 5E) also increased β2-chimaerin mRNA expression. Conversely, TAZ overexpression repressed β2-chimaerin mRNA expression in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 5F). Given our observations that Rac1 activates TAZ (Figure 3) and that TAZ represses β2-chimaerin expression, we inhibited Rac1 in MES cells using EHT1864 and observed an increase in the expression of β2-chimaerin mRNA (Figure 5G). These results provide evidence that VEGF-NRP2-Rac1-mediated TAZ activation maintains elevated Rac1 activity by repressing β2-chimaerin in a positive feedback loop.

Figure 5: TAZ Activates Rac1 by Repressing β2-chimaerin.

A.) TAZ expression was diminished in MES cells and the impact on β2-chimaerin mRNA expression was quantified by qPCR. Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. (B and C) β2-chimaerin abundance (B) and Rac1 activity (C) were assessed in TAZ knockdown MES cells. Representative blots are shown. Densitometric values are provided as bar graphs (mean ± SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates. D.) TAZ expression was diminished in MDA-MB-435 cells and the impact on β2-chimaerin mRNA expression was quantified by qPCR. Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. E.) TAZ expression was diminished in MDA-MB-231 cells and the impact on β2-chimaerin mRNA expression was quantified by qPCR. Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. F.) MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with TAZ and the impact on β2-chimaerin mRNA expression was quantified by qPCR. Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. G.) MES cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of the Rac inhibitor EHT1864 for 2 hours and β2-chimaerin mRNA expression was quantified by qPCR. Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. * p ≤ 0.05 by two-tailed t test.

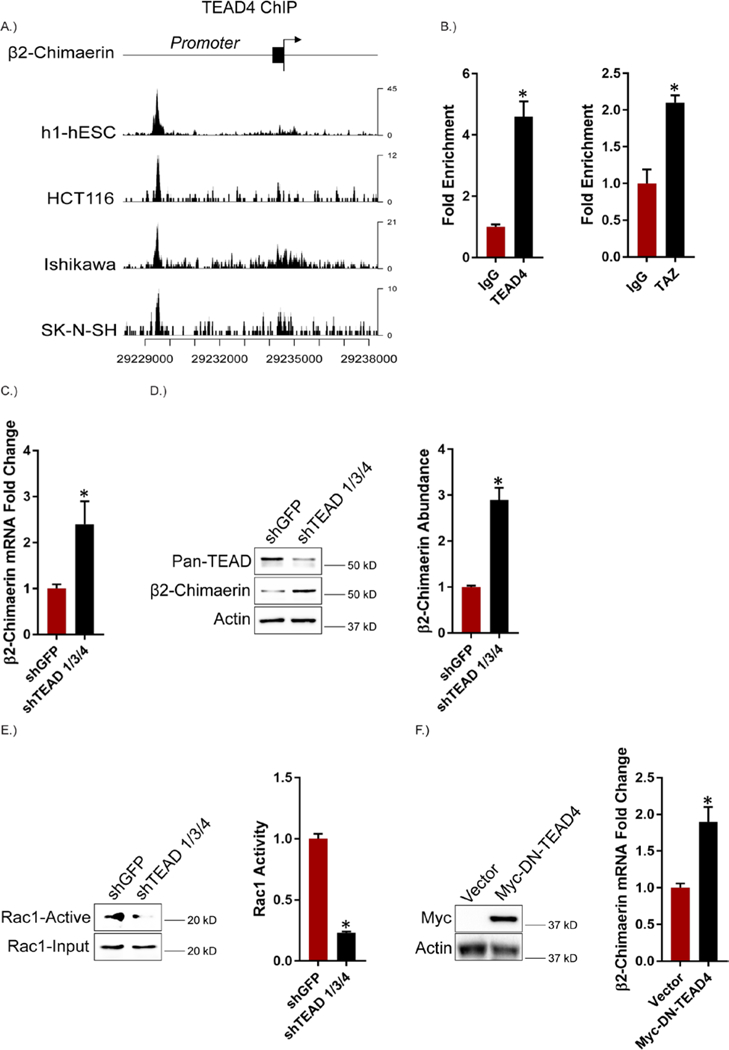

TAZ-mediated transcriptional repression is dependent on the TEAD1–4 family of transcription factors (62, 63). TEAD4, in particular, is expressed at relatively high levels in breast cancer, especially triple negative breast cancer (64, 65). Given this information, we initially searched the encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE) for TEAD4 ChIP-seq datasets and found 4 cell types (h1-human embryonic stem cells, HCT116 colon cancer cells, Ishikawa endometrial adenocarcinoma cells and SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells) where TEAD4 bound to the promoter region of the β2-chimaerin gene (Figure 6A). Specifically, a conserved peak was observed near position 29229000 (chr7) in all of the cell types. These findings are significant because they demonstrate direct binding of TEAD4 to the β2-chimaerin promoter. Also, h1-hESCs, HCT116, Ishikawa and SK-N-SH cells have enhanced TAZ/TEAD activity (66, 67). To validate the ENCODE data in our model system, we performed ChIP in MES cells using antibodies specific for TEAD4 and TAZ. The results verify that TEAD4 and TAZ are recruited to the genomic region in the β2-chimaerin promoter identified in ENCODE (Figure 6B). Based on these data, we depleted TEAD1/3/4 expression in MES cells and observed an increase in β2-chimaerin mRNA and protein expression (Figures 6, C and D) and a decrease in Rac1 activity (Figure 6E), consistent with our TAZ knockdown results (Figures 5, A to C). Similarly, expression of dominant-negative TEAD4 in MDA-MB-231 cells increased β2-chimaerin mRNA expression (Figure 6F).

Figure 6: TEAD Mediates Repression of β2-chimaerin by TAZ.

A.) Using ENCODE, TEAD4 binding signals were analyzed from ChIP-seq datasets from h1-hESCs (human embryonic stem cells), HCT116 (colon cancer), Ishikawa (endometrial adenocarcinoma) and SK-N-SH (neuroblastoma) cells in the promoter region of the β2-chimaerin gene. B.) Binding of TEAD4 and TAZ on the β2-chimaerin promoter was analyzed using ChIP in MES cells. Error bars indicate standard deviation from 3 technical replicates. Data are representative of n = 2 biological replicates. C.) TEAD 1/3/4 expression was diminished in MES cells and the impact on β2-chimaerin mRNA expression was quantified by qPCR. Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. (D and E) β2-chimaerin abundance (D) and Rac1 activity (E) were assessed in TEAD 1/3/4 knockdown MES cells. Representative blots are shown. Densitometric values are provided as bar graphs (mean ± SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates. F.) β2-chimaerin mRNA expression was quantified by qPCR in MDA-MB-231 cells expressing either a control vector or dominant-negative TEAD4. Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. * p ≤ 0.05 by two-tailed t test.

β2-chimaerin Repression Contributes to Enhanced TAZ Activity:

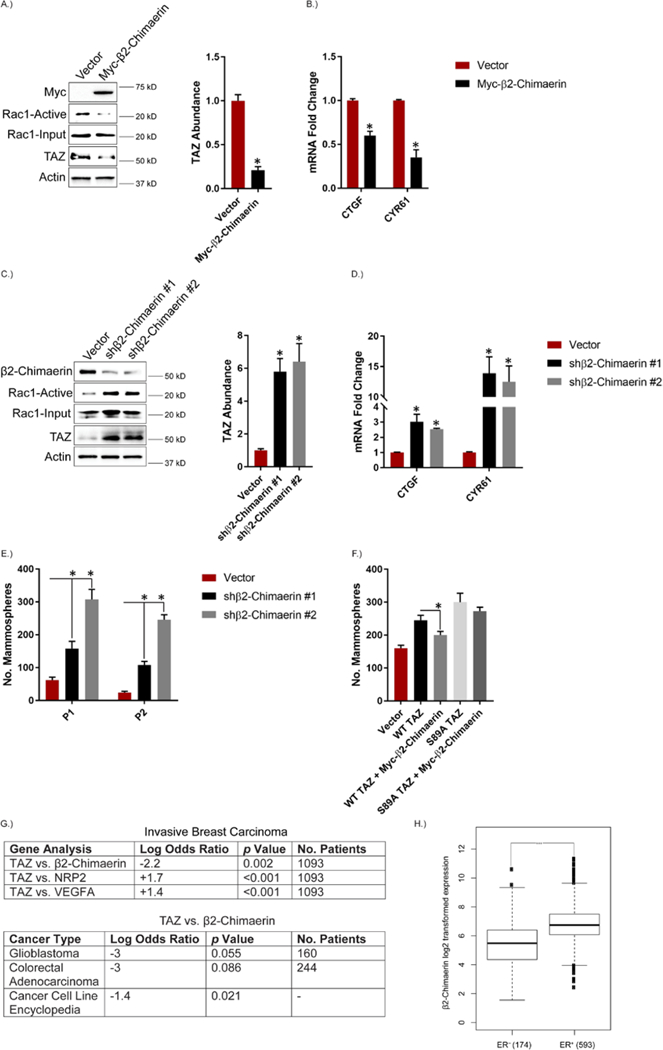

An important issue that arises from the data thus far is whether β2-chimaerin repression has a causal role in TAZ activation. Expression of β2-chimaerin in MDA-MB-231 cells decreased Rac1 activity, as well as the abundance of TAZ itself (Figure 7A) and TAZ target genes (Figure 7B). Conversely, β2-chimaerin knockdown in EPTH cells increased Rac1 activity, TAZ abundance (Figure 7C) and TAZ target genes (Figure 7D). Notably, β2-chimaerin-depleted EPTH cells exhibited increased mammosphere formation compared to control EPTH cells (Figure 7E). Expression of β2-chimaerin also reduced TAZ-mediated, but not S89A TAZ-mediated, mammosphere formation in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 7F), providing further evidence that Rac1 inhibition of LATS contributes to TAZ activation and CSC properties.

Figure 7: β2-chimaerin Repression Contributes to Enhanced TAZ activity.

A.) MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with Myc-tagged β2-chimaerin and Rac1 activity and TAZ abundance were assessed. Representative blots are shown. Densitometric values are provided as bar graphs (mean ± SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates. B.) mRNA expression of the indicated TAZ target genes was quantified by qPCR in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with Myc-tagged β2-chimaerin. Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. C.) Expression of β2-chimaerin was diminished in EPTH cells and the impact on Rac1 activity and TAZ abundance were assessed. Representative blots are shown. Densitometric values are provided as bar graphs (mean ± SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates. D.) mRNA expression of the indicated TAZ target genes was quantified by qPCR in β2-Chimaerin-depleted EPTH cells. Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. E.) β2-chimaerin-depleted EPTH cells were assayed for self-renewal by serial passage mammosphere formation (P1: passage 1; P2: passage 2). Data are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. F.) MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with empty vector, wild-type TAZ or S89A TAZ with and without Myc-tagged β2-chimaerin and assayed for self-renewal by serial passage mammosphere formation. Error bars indicate standard deviation from 3 technical replicates. Data are representative of n = 2 biological replicates. G.) cBioPortal for cancer genomics was used to compare TAZ expression with β2-chimaerin, NRP2 and VEGFA expression in the invasive breast carcinoma dataset from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). The expression of TAZ vs. β2-chimaerin was also compared in the TCGA glioblastoma and colorectal adenocarcinoma databases as well as the cancer cell line encyclopedia (967 cell lines). Log odds ratios and p values were calculated using fisher exact t test with the mutual exclusivity tool on cBioPortal. H.) cBioPortal for cancer genomics was used to analyze the expression of β2-chimaerin in ER+ vs. ER− breast cancer patients from the TCGA invasive breast carcinoma database. * p ≤ 0.05 by two-tailed t test; *** p < 0.0001 by Welch t test.

These in vitro data indicating an inverse causal relationship between β2-chimaerin and TAZ and a positive causal relationship between VEGF-NRP2 and TAZ were substantiated by analysis of their expression in invasive breast carcinomas in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database obtained from cBioPortal (68, 69) (Figure 7G). Indeed, the expression of TAZ and β2-chimaerin were inversely correlated. In contrast, the expression of TAZ correlated with that of VEGF and NRP2. An inverse correlation between TAZ and β2-chimaerin was also detected in glioblastoma and colorectal adenocarcinoma samples in the TCGA. These findings are significant because both glioblastoma and colon cancer exhibit enhanced TAZ activity (66, 70, 71). Lastly, TAZ and β2-chimaerin exhibited an inverse correlation in the cancer cell line encyclopedia obtained from cBioPortal (967 cell lines) (Figure 7G), which provides further evidence of a repressive role (68, 69).

Our data indicate that TAZ-mediated repression of β2-chimaerin is associated with a mesenchymal phenotype. To substantiate this conclusion, we analyzed a microarray (GSE48204) that utilized TGF-β-treated NMuMG mammary epithelial cells to induce an EMT (72). In support of our conclusion, we found that the EMT reduced β2-chimaerin expression and increased expression of VEGF and NRP2, as well as TAZ target genes (fig. S5). We also used cBioPortal to stratify breast cancer patients in the TCGA database based on their expression of the estrogen receptor (ER), which is associated with an epithelial phenotype. Comparison of β2-chimaerin expression in the estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) and ER− subgroups revealed that ER− patients have lower expression of β2-chimaerin compared to ER+ patients (Figure 7H).

Discussion

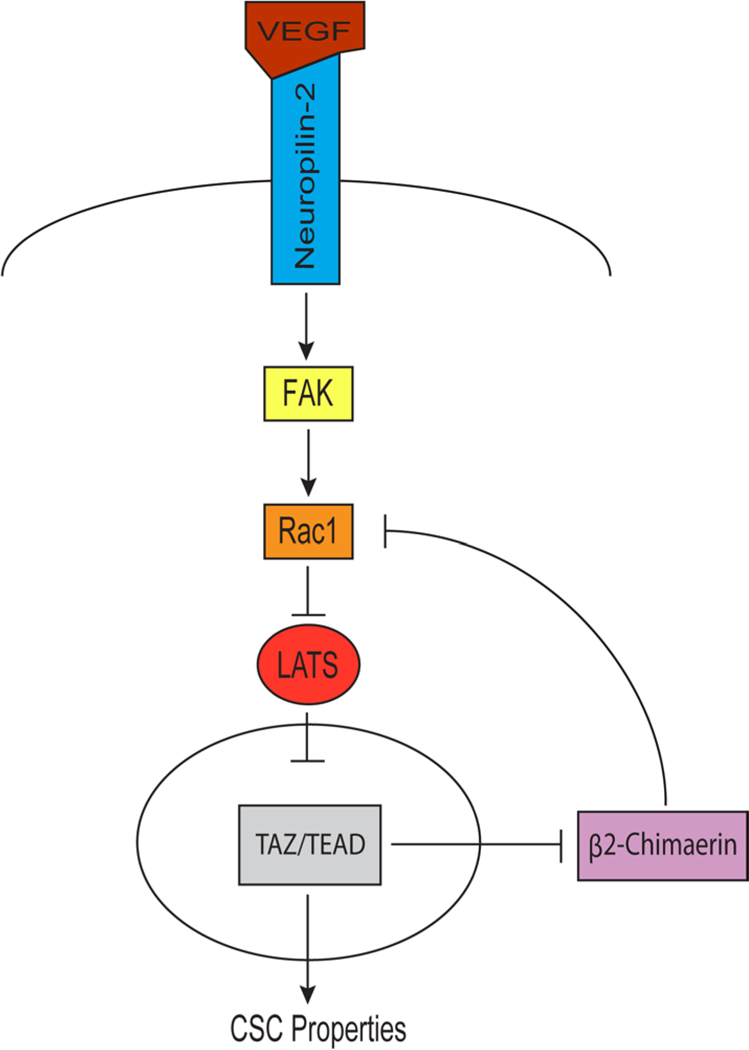

The results of this study establish a causal role for VEGF-NRP2 signaling in sustaining the activation of TAZ, a critical effector molecule of the Hippo pathway that contributes to breast tumorigenesis and is associated with aggressive, high-grade tumors. An essential component of this mechanism is the repression of β2-chimaerin, a Rac GAP, by TAZ and the consequent activation of Rac1 resulting in a positive feedback loop driven by VEGF-NRP2 signaling that sustains TAZ activation (Figure 8). These findings increase our understanding of autocrine VEGF signaling in tumor cells and they substantiate the importance of Rac in the biology of CSCs and TAZ regulation.

Figure 8: Model depicting the major findings of this study.

VEGF-NRP2 signaling promotes FAK-mediated Rac1 activation, which inhibits LATS. Consequently, TAZ is located in the nucleus where it associates with TEAD and represses the Rac GAP β2-chimaerin to maintain elevated Rac1 activity in a positive feedback loop.

Our conclusion that repression of β2-chimaerin contributes to TAZ activation and self-renewal indicates that this Rac GAP is an important gatekeeper that impedes the acquisition of stem cell properties. Based on the hypothesis that breast CSCs are de-differentiated and exhibit features of an EMT (26), this conclusion infers that repression of β2-chimaerin is a consequence of the EMT and that its expression is associated with an epithelial phenotype. Indeed, we uncovered that β2-chimaerin is repressed by the TGF-β-induced EMT of mammary epithelial cells. Importantly, we also demonstrated that ER+ patients have higher β2-chimaerin expression compared to ER− patients. These observations contrast with the report that β2-chimaerin reduces E-cadherin levels in an in vitro overexpression system (60). Interestingly, however, this report also demonstrated that low expression of β2-chimaerin is associated with reduced relapse-free survival of breast cancer patients, which supports our findings.

Our results need to be discussed in the context of the report that NRP2 binds β2-chimaerin directly, and that Semaphorin3F-NRP2 signaling reduces this association to activate β2-chimaerin and regulate axonal pruning in the hippocampus (38). Although β2-chimaerin and NRP2 exhibit an inverse expression pattern in breast cancer, we tested the hypothesis that residual β2-chimaerin may be sequestered and inactivated by NRP2 as a mechanism of Rac1 regulation. However, we were unable to co-immunopurify NRP2 with β2-chimaerin. This is not definitive, but it does suggest NRP2 regulation of β2-chimaerin differs in breast cancer cells and neurons. This difference may reflect the fact that different ligands (Semaphorin3F and VEGF) engage NRP2 in these cells types. It is also worth mentioning that we previously demonstrated that Semaphorin3A and VEGF compete for NRP binding in breast cancer cells, and that these two ligands have opposite effects on the behavior of these cells (73). Nonetheless, the existing data highlight an important causal effect of NRP2 on β2-chimaerin that is executed by distinct mechanisms.

A major conclusion of this study is that VEGF-NRP2 signaling contributes to TAZ activation by a Rac1-dependent mechanism. This role for Rac1 differs from its more established role in regulating cell invasion and migration in cancer, but it is consistent with other reports implicating Rac1 in the function of CSCs (74–76), as well as in YAP/TAZ activation (35, 41–43). Our results on the ability of VEGF-NRP2 signaling to inhibit LATS by a Rac1-dependent mechanism support these observations and they identify a novel ligand-receptor interaction that can mediate this regulation. Furthermore, our data suggest that the ability of Rac1 to inhibit LATS is mediated by its regulation of Merlin, which is an important organizer of the membrane-cytoskeleton interface (52–55, 77–79). Although we are not ruling out the possibility that VEGF-NRP2 signaling may activate RhoA, which has also been implicated in YAP/TAZ activation (35, 41, 79–81), we focused our attention on Rac1 because β2-xhimaerin is Rac-specific and does not have GAP activity against Rho (57, 58).

Although many studies have implicated autocrine VEGF signaling in the function of CSCs (20), its ability to contribute to Hippo-TAZ regulation provides a new dimension to our understanding of VEGF biology. While this manuscript was in review, however, it was reported that VEGF-VEGFR2 signaling contributes to YAP/TAZ activation during developmental angiogenesis (82). Our data support the role of VEGF in promoting YAP/TAZ activation, but the mechanism used by breast cancer cells is distinct because it appears to be dependent on VEGF-NRP2 activation of FAK-Rac1 but independent of VEGFR. Moreover, our findings reveal a pivotal role for β2-xhimaerin as a repressive intermediary between VEGF-NRP2 and TAZ activation. They also reinforce the hypothesis that targeting VEGF-NRP signaling is a viable therapeutic strategy for tumor cells that are dependent on TAZ activation.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Antibodies

EHT1864 was purchased from Tocris, NSC23766 was purchased from Selleckchem, FAK14 was purchased from Sigma, Sunitinib and Pazopanib were purchased from LC Laboratories, human VEGFA165 was purchased from R&D Systems and the function-blocking Neuropilin-2 antibody was provided by Genentech (11). Immunoblotting antibodies were acquired as follows: Actin (A2066, Sigma), TAZ (560235, BD Biosciences), YAP/TAZ (8418S, Cell Signaling Technologies), pS89 TAZ (sc-17610, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), pS127 YAP (4911A, Cell Signaling Technologies), Neuropilin-2 (sc-7242, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), β2-chimaerin (CHN2) (HPA018989, Sigma), pT1079 LATS1 (8654S, Cell Signaling Technologies), LATS1 (9153S, Cell Signaling Technologies), VEGF (sc-152, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Rac1 (610650, BD Biosciences), Pan-TEAD (13295S, Cell Signaling Technologies), pS518 Merlin (9163S, Cell Signaling Technologies), Merlin (6995S, Cell Signaling Technologies), HA-Tag (3724S, Cell Signaling Technologies), GST (sc-138, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and Myc-Tag (2278S, Cell Signaling Technologies).

Constructs

The following lentiviral shRNA vectors were used: VEGF (TRCN0000003343, TRCN0000003344, TRCN0000003345), Neuropilin-2 (TRCN0000063309, TRCN0000063312, TRCN0000063310), β2-chimaerin (provided by Dr. Alex Kolodkin, Johns Hopkins Medical Institute (38)) and TEAD 1/3/4 (provided by Dr. Junhao Mao, University of Massachusetts Medical School (66)). Retroviral shTAZ vectors were used as previously described (32). Stable shRNA expression was accomplished by selecting cells in 2 μg/mL puromycin for 2 to 4 days. Myc-tagged (6X) β2-chimaerin was provided by Dr. Alex Kolodkin, Johns Hopkins Medical Institute (38), Myc-tagged dominant negative TEAD4 was provided by Dr. Junhao Mao, University of Massachusetts Medical School, dominant negative Rac1 (N17Rac1) and constitutively active Rac1 (V12Rac1) were described previously (21). Human TAZ was cloned into pcDNA3.1 vector and site-directed mutagenesis was performed to generate TAZ S89A.

Cell Culture

ER-SRC transformed MCF10A cells were provided by Dr. Kevin Struhl (Harvard Medical School). To generate puromycin sensitive MCF10A ER-SRC cells, v-SRC was cloned from the cDNA pool of the original MCF10A ER-SRC cell line. Subsequently, pWZL Blast Twist ER plasmid (Addgene Plasmid #18799) was digested by BamHI to remove the Snai1 cDNA, and replaced with v-SRC cDNA, resulting in the expression of the fusion protein, v-SRC-ER, by the new recombinant plasmid. This plasmid was subsequently used to produce retrovirus for infecting MCF10A cells. Stable clones were selected by blasticidin. Isolation of the EPTH and MES populations of CD44+CD24−/low MCF10A ER-SRC transformed cells using flow cytometry has been previously described (33). EPTH and MES cells were cultured as subclones for 2–3 passages and used for experiments. MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-435 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. All experiments were performed at a cell density of 25–35%.

Transfection and siRNA Knockdown

For overexpression, plasmids were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were processed for immunoblotting, qPCR or mammosphere formation approximately 24 hours following transfection. For LATS ½ siRNA knockdown, MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected using DharmaFect 4 (Dharmacon). Cells were processed for immunoblotting 48 hours following transfection. LATS ½ siRNA has been previously described (32).

Mammosphere Assay

Cells were plated in UltraLow attachment 6 well plates in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with B27, EGF and fibroblast growth factor as previously described (33). For serial passaging, mammospheres were pelleted and dissociated with 0.05% Trypsin for 15 minutes at 37 degrees Celsius to obtain single cells. These cells were washed in 1X PBS, counted and re-plated in UltraLow attachment 6 well plates.

Immunolotting

Cells were washed in 1X PBS and scraped on ice in RIPA buffer with EDTA and EGTA (BP-115DG, Boston Bioproducts) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Pierce, #88669). Laemmli 6X SDS sample buffer (BP-111R, Boston Bioproducts) was added to each sample and the protein lysate was boiled for 10 minutes and separated using SDS-PAGE. Rac activity was assessed using a GST fusion protein containing the Rac/cdc42 binding domain of PAK (PBD) as previously described (21, 83).

Luciferase Reporter Assay

TEAD transcriptional activity was assessed using a luciferase reporter construct (8XGTIIC-Addgene #34615) with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (#E2940, Promega). Approximately 24 hours following transfection, luciferase activity was measured as the average ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase.

Real time quantitative PCR

RNA extraction was accomplished using an RNA isolation kit (BS88133, Bio Basic Inc) and cDNAs were produced using qScrict cDNA synthesis kit (#95047, Quantabio). SYBR green (Applied Biosystems) was used as the qPCR master mix. Experiments were performed in triplicate and normalized to GAPDH. qPCR primer sequences were obtained from the Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School PrimerBank (http://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank/).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChiP was performed using ChIP-IT Express Chromatin Immunoprecipitation kit (Active Motif). Antibodies used were TEAD4 (N-G2, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and TAZ (70148S, Cell Signaling Technologies). The following qPCR primer sequence was used to amplify the region of the TEAD4 peak in the β2-chimaerin promoter identified in ENCODE: Forward primer 5’-GCTTACAGCTGGCTTCACTT-3’ Reverse Primer 5’-GGCCGAGAGAGAGAGAGTTT-3’.

Immunoflourescence Confocal Microscopy

TAZ localization was performed by fixing cells with paraformaldehyde (4%) and permeabilizing them with Triton X-100 (0.1%) as described (23, 32). Cells were blocked with 1% BSA and horse serum (2.5%) and incubated with TAZ antibody (1:100 dilution; sc-48805, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, cells were washed with 1X PBS and incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies. Images were captured at 20X magnification using a confocal microscope (Zeiss).

ENCODE Data Analysis

Encode TEAD4 binding signals were downloaded from www.encodeproject.org in bigwig format. The coverages of duplicate samples were pooled and then plotted along the promoter region of the β2-chimaerin (CHN2) gene.

cBioPortal Analysis

cBioPortal (www.cbioportal.org) was utilized to compare the mRNA expression (RNA Seq V2 RSEM) of TAZ, VEGFA, NRP2 and β2-chimaerin using the TCGA invasive breast carcinoma provisional dataset (68, 69). In addition, the mRNA expression (RNA Seq V2 RSEM) of TAZ and β2-chimaerin was compared in the TCGA glioblastoma provisional dataset and the TCGA colorectal adenocarcinoma Nature 2012 dataset. The cancer cell line encyclopedia (Novartis/Broad, Nature 2012) was used to compare the expression of TAZ and β2-chimaerin across various cell lines using the mRNA expression z-scores microarray. To determine whether the expression of two genes are inversely correlated, we performed the mutual exclusivity analysis with a z-score threshold of ± 1.5 as expressed, and calculated the log odds ratio between the two genes and p value using Fisher exact t-test. In addition, we stratified breast cancer patients in the TCGA Cell 2015 database based on their ER status, and compared β2-Chimaerin expression in the ER+ and ER− subgroups using Welch t-test.

Microarray Data Analysis

The microarray dataset from GEO (GSE48204) (72) was download using the Bioconductor package GEOquery (version 2.41.0). Moderated t-test was used to identify differentially expressed genes between TGF-β induced EMT cells and NMuMG cells treated with vehicle. Genes with an adjusted p-value of ≤ 0.05 using B-H method were considered significant (84).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Chung-Cheng Hsieh for consulting on statistical analysis, and Drs. Dan McCollum, Junhao Mao, Dohoon Kim and Tom Fazzio for helpful discussions.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH Grants CA168464 and CA203439 (A.M.M). Ameer L. Elaimy was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award from the NCI (F30CA206271) and an American Medical Association Foundation Medical Student Seed Grant.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors of this manuscript do not have any competing interests.

Data and materials availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.

References and Notes

- 1.Leung DW, Cachianes G, Kuang WJ, Goeddel DV, Ferrara N, Vascular endothelial growth factor is a secreted angiogenic mitogen. Science 246, 1306–1309 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Senger DR, Galli SJ, Dvorak AM, Perruzzi CA, Harvey VS, Dvorak HF, Tumor cells secrete a vascular permeability factor that promotes accumulation of ascites fluid. Science 219, 983–985 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrara N, VEGF and the quest for tumour angiogenesis factors. Nat Rev Cancer 2, 795–803 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tischer E, Gospodarowicz D, Mitchell R, Silva M, Schilling J, Lau K, Crisp T, Fiddes JC, Abraham JA, Vascular endothelial growth factor: a new member of the platelet-derived growth factor gene family. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 165, 1198–1206 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrara N, VEGF as a therapeutic target in cancer. Oncology 69 Suppl 3, 11–16 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uniewicz KA, Fernig DG, Neuropilins: a versatile partner of extracellular molecules that regulate development and disease. Front Biosci 13, 4339–4360 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soker S, Takashima S, Miao HQ, Neufeld G, Klagsbrun M, Neuropilin-1 is expressed by endothelial and tumor cells as an isoform-specific receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor. Cell 92, 735–745 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neufeld G, Kessler O, Herzog Y, The interaction of Neuropilin-1 and Neuropilin-2 with tyrosine-kinase receptors for VEGF. Adv Exp Med Biol 515, 81–90 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sulpice E, Plouet J, Berge M, Allanic D, Tobelem G, Merkulova-Rainon T, Neuropilin-1 and neuropilin-2 act as coreceptors, potentiating proangiogenic activity. Blood 111, 2036–2045 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koch S, van Meeteren LA, Morin E, Testini C, Westrom S, Bjorkelund H, Le Jan S, Adler J, Berger P, Claesson-Welsh L, NRP1 presented in trans to the endothelium arrests VEGFR2 endocytosis, preventing angiogenic signaling and tumor initiation. Dev Cell 28, 633–646 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caunt M, Mak J, Liang WC, Stawicki S, Pan Q, Tong RK, Kowalski J, Ho C, Reslan HB, Ross J, Berry L, Kasman I, Zlot C, Cheng Z, Le Couter J, Filvaroff EH, Plowman G, Peale F, French D, Carano R, Koch AW, Wu Y, Watts RJ, Tessier-Lavigne M, Bagri A, Blocking neuropilin-2 function inhibits tumor cell metastasis. Cancer Cell 13, 331–342 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goel HL, Chang C, Pursell B, Leav I, Lyle S, Xi HS, Hsieh CC, Adisetiyo H, Roy-Burman P, Coleman IM, Nelson PS, Vessella RL, Davis RJ, Plymate SR, Mercurio AM, VEGF/neuropilin-2 regulation of Bmi-1 and consequent repression of IGF-IR define a novel mechanism of aggressive prostate cancer. Cancer Discov 2, 906–921 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray MJ, Van Buren G, Dallas NA, Xia L, Wang X, Yang AD, Somcio RJ, Lin YG, Lim S, Fan F, Mangala LS, Arumugam T, Logsdon CD, Lopez-Berestein G, Sood AK, Ellis LM, Therapeutic targeting of neuropilin-2 on colorectal carcinoma cells implanted in the murine liver. J Natl Cancer Inst 100, 109–120 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan Q, Chanthery Y, Liang WC, Stawicki S, Mak J, Rathore N, Tong RK, Kowalski J, Yee SF, Pacheco G, Ross S, Cheng Z, Le Couter J, Plowman G, Peale F, Koch AW, Wu Y, Bagri A, Tessier-Lavigne M, Watts RJ, Blocking neuropilin-1 function has an additive effect with anti-VEGF to inhibit tumor growth. Cancer Cell 11, 53–67 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 3983–3988 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baccelli I, Trumpp A, The evolving concept of cancer and metastasis stem cells. J Cell Biol 198, 281–293 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta PB, Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA, Cancer stem cells: mirage or reality? Nat Med 15, 1010–1012 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korkaya H, Liu S, Wicha MS, Breast cancer stem cells, cytokine networks, and the tumor microenvironment. J Clin Invest 121, 3804–3809 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S, Ginestier C, Ou SJ, Clouthier SG, Patel SH, Monville F, Korkaya H, Heath A, Dutcher J, Kleer CG, Jung Y, Dontu G, Taichman R, Wicha MS, Breast cancer stem cells are regulated by mesenchymal stem cells through cytokine networks. Cancer Res 71, 614–624 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goel HL, Mercurio AM, VEGF targets the tumour cell. Nat Rev Cancer 13, 871–882 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goel HL, Pursell B, Shultz LD, Greiner DL, Brekken RA, Vander Kooi CW, Mercurio AM, P-Rex1 Promotes Resistance to VEGF/VEGFR-Targeted Therapy in Prostate Cancer. Cell Rep 14, 2193–2208 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goel HL, Pursell B, Chang C, Shaw LM, Mao J, Simin K, Kumar P, Vander Kooi CW, Shultz LD, Greiner DL, Norum JH, Toftgard R, Kuperwasser C, Mercurio AM, GLI1 regulates a novel neuropilin-2/alpha6beta1 integrin based autocrine pathway that contributes to breast cancer initiation. EMBO Mol Med 5, 488–508 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cordenonsi M, Zanconato F, Azzolin L, Forcato M, Rosato A, Frasson C, Inui M, Montagner M, Parenti AR, Poletti A, Daidone MG, Dupont S, Basso G, Bicciato S, Piccolo S, The Hippo transducer TAZ confers cancer stem cell-related traits on breast cancer cells. Cell 147, 759–772 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pece S, Tosoni D, Confalonieri S, Mazzarol G, Vecchi M, Ronzoni S, Bernard L, Viale G, Pelicci PG, Di Fiore PP, Biological and molecular heterogeneity of breast cancers correlates with their cancer stem cell content. Cell 140, 62–73 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lei QY, Zhang H, Zhao B, Zha ZY, Bai F, Pei XH, Zhao S, Xiong Y, Guan KL, TAZ promotes cell proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition and is inhibited by the hippo pathway. Mol Cell Biol 28, 2426–2436 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheel C, Weinberg RA, Cancer stem cells and epithelial-mesenchymal transition: concepts and molecular links. Semin Cancer Biol 22, 396–403 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zanconato F, Cordenonsi M, Piccolo S, YAP/TAZ at the Roots of Cancer. Cancer Cell 29, 783–803 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu FX, Guan KL, The Hippo pathway: regulators and regulations. Genes Dev 27, 355–371 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanai F, Marignani PA, Sarbassova D, Yagi R, Hall RA, Donowitz M, Hisaminato A, Fujiwara T, Ito Y, Cantley LC, Yaffe MB, TAZ: a novel transcriptional co-activator regulated by interactions with 14–3-3 and PDZ domain proteins. EMBO J 19, 6778–6791 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varelas X, The Hippo pathway effectors TAZ and YAP in development, homeostasis and disease. Development 141, 1614–1626 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Wang G, Struhl K, Inducible formation of breast cancer stem cells and their dynamic equilibrium with non-stem cancer cells via IL6 secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 1397–1402 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang C, Goel HL, Gao H, Pursell B, Shultz LD, Greiner DL, Ingerpuu S, Patarroyo M, Cao S, Lim E, Mao J, McKee KK, Yurchenco PD, Mercurio AM, A laminin 511 matrix is regulated by TAZ and functions as the ligand for the alpha6Bbeta1 integrin to sustain breast cancer stem cells. Genes Dev 29, 1–6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goel HL, Gritsko T, Pursell B, Chang C, Shultz LD, Greiner DL, Norum JH, Toftgard R, Shaw LM, Mercurio AM, Regulated splicing of the alpha6 integrin cytoplasmic domain determines the fate of breast cancer stem cells. Cell Rep 7, 747–761 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu CY, Zha ZY, Zhou X, Zhang H, Huang W, Zhao D, Li T, Chan SW, Lim CJ, Hong W, Zhao S, Xiong Y, Lei QY, Guan KL, The hippo tumor pathway promotes TAZ degradation by phosphorylating a phosphodegron and recruiting the SCF{beta}-TrCP E3 ligase. J Biol Chem 285, 37159–37169 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park HW, Kim YC, Yu B, Moroishi T, Mo JS, Plouffe SW, Meng Z, Lin KC, Yu FX, Alexander CM, Wang CY, Guan KL, Alternative Wnt Signaling Activates YAP/TAZ. Cell 162, 780–794 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang H, Liu CY, Zha ZY, Zhao B, Yao J, Zhao S, Xiong Y, Lei QY, Guan KL, TEAD transcription factors mediate the function of TAZ in cell growth and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem 284, 13355–13362 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu BP, Strittmatter SM, Semaphorin-mediated axonal guidance via Rho-related G proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol 13, 619–626 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riccomagno MM, Hurtado A, Wang H, Macopson JG, Griner EM, Betz A, Brose N, Kazanietz MG, Kolodkin AL, The RacGAP beta2-Chimaerin selectively mediates axonal pruning in the hippocampus. Cell 149, 1594–1606 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan W, Palmby TR, Gavard J, Amornphimoltham P, Zheng Y, Gutkind JS, An essential role for Rac1 in endothelial cell function and vascular development. FASEB J 22, 1829–1838 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fryer BH, Field J, Rho, Rac, Pak and angiogenesis: old roles and newly identified responsibilities in endothelial cells. Cancer Lett 229, 13–23 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng X, Degese MS, Iglesias-Bartolome R, Vaque JP, Molinolo AA, Rodrigues M, Zaidi MR, Ksander BR, Merlino G, Sodhi A, Chen Q, Gutkind JS, Hippo-independent activation of YAP by the GNAQ uveal melanoma oncogene through a trio-regulated rho GTPase signaling circuitry. Cancer Cell 25, 831–845 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jang JW, Kim MK, Lee YS, Lee JW, Kim DM, Song SH, Lee JY, Choi BY, Min B, Chi XZ, Bae SC, RAC-LATS½ signaling regulates YAP activity by switching between the YAP-binding partners TEAD4 and RUNX3. Oncogene 36, 999–1011 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gargini R, Escoll M, Garcia E, Garcia-Escudero R, Wandosell F, Anton IM, WIP Drives Tumor Progression through YAP/TAZ-Dependent Autonomous Cell Growth. Cell Rep 17, 1962–1977 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bachelder RE, Crago A, Chung J, Wendt MA, Shaw LM, Robinson G, Mercurio AM, Vascular endothelial growth factor is an autocrine survival factor for neuropilin-expressing breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 61, 5736–5740 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang F, Lemmon CA, Park D, Romer LH, FAK potentiates Rac1 activation and localization to matrix adhesion sites: a role for betaPIX. Mol Biol Cell 18, 253–264 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chiu YW, Liou LY, Chen PT, Huang CM, Luo FJ, Hsu YK, Yuan TC, Tyrosine 397 phosphorylation is critical for FAK-promoted Rac1 activation and invasive properties in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Lab Invest 96, 296–306 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pasapera AM, Plotnikov SV, Fischer RS, Case LB, Egelhoff TT, Waterman CM, Rac1-dependent phosphorylation and focal adhesion recruitment of myosin IIA regulates migration and mechanosensing. Curr Biol 25, 175–186 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim NG, Gumbiner BM, Adhesion to fibronectin regulates Hippo signaling via the FAK-Src-PI3K pathway. J Cell Biol 210, 503–515 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu JK, Du W, Shelton SJ, Oldham MC, DiPersio CM, Klein OD, An FAK-YAP-mTOR Signaling Axis Regulates Stem Cell-Based Tissue Renewal in Mice. Cell Stem Cell 21, 91–106 e106 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chan EH, Nousiainen M, Chalamalasetty RB, Schafer A, Nigg EA, Sillje HH, The Ste20-like kinase Mst2 activates the human large tumor suppressor kinase Lats1. Oncogene 24, 2076–2086 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meng Z, Moroishi T, Guan KL, Mechanisms of Hippo pathway regulation. Genes Dev 30, 1–17 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shaw RJ, Paez JG, Curto M, Yaktine A, Pruitt WM, Saotome I, O’Bryan JP, Gupta V, Ratner N, Der CJ, Jacks T, McClatchey AI, The Nf2 tumor suppressor, merlin, functions in Rac-dependent signaling. Dev Cell 1, 63–72 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xiao GH, Beeser A, Chernoff J, Testa JR, p21-activated kinase links Rac/Cdc42 signaling to merlin. J Biol Chem 277, 883–886 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kissil JL, Johnson KC, Eckman MS, Jacks T, Merlin phosphorylation by p21-activated kinase 2 and effects of phosphorylation on merlin localization. J Biol Chem 277, 10394–10399 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yin F, Yu J, Zheng Y, Chen Q, Zhang N, Pan D, Spatial organization of Hippo signaling at the plasma membrane mediated by the tumor suppressor Merlin/NF2. Cell 154, 1342–1355 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kumar R, Gururaj AE, Barnes CJ, p21-activated kinases in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 6, 459–471 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Caloca MJ, Wang H, Kazanietz MG, Characterization of the Rac-GAP (Rac-GTPase-activating protein) activity of beta2-chimaerin, a ‘non-protein kinase C’ phorbol ester receptor. Biochem J 375, 313–321 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Diekmann D, Brill S, Garrett MD, Totty N, Hsuan J, Monfries C, Hall C, Lim L, Hall A, Bcr encodes a GTPase-activating protein for p21rac. Nature 351, 400–402 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang C, Liu Y, Leskow FC, Weaver VM, Kazanietz MG, Rac-GAP-dependent inhibition of breast cancer cell proliferation by {beta}2-chimerin. J Biol Chem 280, 24363–24370 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Casado-Medrano V, Barrio-Real L, Garcia-Rostan G, Baumann M, Rocks O, Caloca MJ, A new role of the Rac-GAP beta2-chimaerin in cell adhesion reveals opposite functions in breast cancer initiation and tumor progression. Oncotarget 7, 28301–28319 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Menna PL, Skilton G, Leskow FC, Alonso DF, Gomez DE, Kazanietz MG, Inhibition of aggressiveness of metastatic mouse mammary carcinoma cells by the beta2-chimaerin GAP domain. Cancer Res 63, 2284–2291 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim M, Kim T, Johnson RL, Lim DS, Transcriptional co-repressor function of the hippo pathway transducers YAP and TAZ. Cell Rep 11, 270–282 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Valencia-Sama I, Zhao Y, Lai D, Janse van Rensburg HJ, Hao Y, Yang X, Hippo Component TAZ Functions as a Co-repressor and Negatively Regulates DeltaNp63 Transcription through TEA Domain (TEAD) Transcription Factor. J Biol Chem 290, 16906–16917 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang C, Nie Z, Zhou Z, Zhang H, Liu R, Wu J, Qin J, Ma Y, Chen L, Li S, Chen W, Li F, Shi P, Wu Y, Shen J, Chen C, The interplay between TEAD4 and KLF5 promotes breast cancer partially through inhibiting the transcription of p27Kip1. Oncotarget 6, 17685–17697 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adelaide J, Finetti P, Bekhouche I, Repellini L, Geneix J, Sircoulomb F, Charafe-Jauffret E, Cervera N, Desplans J, Parzy D, Schoenmakers E, Viens P, Jacquemier J, Birnbaum D, Bertucci F, Chaffanet M, Integrated profiling of basal and luminal breast cancers. Cancer Res 67, 11565–11575 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu X, Li H, Rajurkar M, Li Q, Cotton JL, Ou J, Zhu LJ, Goel HL, Mercurio AM, Park JS, Davis RJ, Mao J, Tead and AP1 Coordinate Transcription and Motility. Cell Rep 14, 1169–1180 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ohgushi M, Minaguchi M, Sasai Y, Rho-Signaling-Directed YAP/TAZ Activity Underlies the Long-Term Survival and Expansion of Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 17, 448–461 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, Antipin Y, Reva B, Goldberg AP, Sander C, Schultz N, The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov 2, 401–404 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, Cerami E, Sander C, Schultz N, Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal 6, pl1 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bhat KP, Salazar KL, Balasubramaniyan V, Wani K, Heathcock L, Hollingsworth F, James JD, Gumin J, Diefes KL, Kim SH, Turski A, Azodi Y, Yang Y, Doucette T, Colman H, Sulman EP, Lang FF, Rao G, Copray S, Vaillant BD, Aldape KD, The transcriptional coactivator TAZ regulates mesenchymal differentiation in malignant glioma. Genes Dev 25, 2594–2609 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yuen HF, McCrudden CM, Huang YH, Tham JM, Zhang X, Zeng Q, Zhang SD, Hong W, TAZ expression as a prognostic indicator in colorectal cancer. PLoS One 8, e54211 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chang C, Yang X, Pursell B, Mercurio AM, Id2 complexes with the SNAG domain of Snai1 inhibiting Snai1-mediated repression of integrin beta4. Mol Cell Biol 33, 3795–3804 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bachelder RE, Lipscomb EA, Lin X, Wendt MA, Chadborn NH, Eickholt BJ, Mercurio AM, Competing autocrine pathways involving alternative neuropilin-1 ligands regulate chemotaxis of carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 63, 5230–5233 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lai YJ, Tsai JC, Tseng YT, Wu MS, Liu WS, Lam HI, Yu JH, Nozell SE, Benveniste EN, Small G protein Rac GTPases regulate the maintenance of glioblastoma stem-like cells in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget 8, 18031–18049 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Man J, Shoemake J, Zhou W, Fang X, Wu Q, Rizzo A, Prayson R, Bao S, Rich JN, Yu JS, Sema3C promotes the survival and tumorigenicity of glioma stem cells through Rac1 activation. Cell Rep 9, 1812–1826 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McCauley HA, Chevrier V, Birnbaum D, Guasch G, De-repression of the RAC activator ELMO1 in cancer stem cells drives progression of TGFbeta-deficient squamous cell carcinoma from transition zones. Elife 6, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li W, You L, Cooper J, Schiavon G, Pepe-Caprio A, Zhou L, Ishii R, Giovannini M, Hanemann CO, Long SB, Erdjument-Bromage H, Zhou P, Tempst P, Giancotti FG, Merlin/NF2 suppresses tumorigenesis by inhibiting the E3 ubiquitin ligase CRL4(DCAF1) in the nucleus. Cell 140, 477–490 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li W, Cooper J, Zhou L, Yang C, Erdjument-Bromage H, Zagzag D, Snuderl M, Ladanyi M, Hanemann CO, Zhou P, Karajannis MA, Giancotti FG, Merlin/NF2 loss-driven tumorigenesis linked to CRL4(DCAF1)-mediated inhibition of the hippo pathway kinases Lats1 and 2 in the nucleus. Cancer Cell 26, 48–60 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Plouffe SW, Meng Z, Lin KC, Lin B, Hong AW, Chun JV, Guan KL, Characterization of Hippo Pathway Components by Gene Inactivation. Mol Cell 64, 993–1008 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dupont S, Morsut L, Aragona M, Enzo E, Giulitti S, Cordenonsi M, Zanconato F, Le Digabel J, Forcato M, Bicciato S, Elvassore N, Piccolo S, Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature 474, 179–183 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yu FX, Zhao B, Panupinthu N, Jewell JL, Lian I, Wang LH, Zhao J, Yuan H, Tumaneng K, Li H, Fu XD, Mills GB, Guan KL, Regulation of the Hippo-YAP pathway by G-protein-coupled receptor signaling. Cell 150, 780–791 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang X, Freire Valls A, Schermann G, Shen Y, Moya IM, Castro L, Urban S, Solecki GM, Winkler F, Riedemann L, Jain RK, Mazzone M, Schmidt T, Fischer T, Halder G, Ruiz de Almodovar C, YAP/TAZ Orchestrate VEGF Signaling during Developmental Angiogenesis. Dev Cell 42, 462–478 e467 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Moriarty CH, Pursell B, Mercurio AM, miR-10b targets Tiam1: implications for Rac activation and carcinoma migration. J Biol Chem 285, 20541–20546 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Benjamini Y, Hockberg Y, Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 57, 289–300 (1995). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.