Abstract

Background:

Early childhood trauma is known to independently increase adverse outcome risk in coronary artery disease (CAD) patients, although the neurological correlates are not well understood. The purpose of this study was to examine whether early childhood trauma alters neural responses to acute mental stress in CAD patients.

Methods:

Participants (n = 152) with CAD underwent brain imaging with High Resolution Positron Emission Tomography and radiolabeled water during control (verbal counting, neutral speaking) and mental stress (mental arithmetic, public speaking). Traumatic events in childhood were assessed with the Early Trauma Inventory (ETI-SR-SF) and participants were separated by presence (ETI+) or absence (ETI−) of early childhood trauma. Brain activity during mental stress was compared between ETI+ and ETI−.

Results:

Compared to ETI−, ETI+ experienced greater (p < 0.005) activations during mental stress within the left anterior cingulate, left occipital lobe, bilateral frontal lobe and deactivations (p < 0.005) within the left insula, left parahippocampal gyrus, right dorsal anterior cingulate, bilateral cerebellum, bilateral fusiform gyrus, left inferior temporal gyrus, right occipital lobe, and right parietal lobe. Significant (p < 0.005) positive correlations between brain activation and ETI-SR-SF scores were observed within the left hippocampus, bilateral frontal lobe, left occipital cuneus, right parietal precuneus, and bilateral temporal lobe.

Limitations:

Results in non-CAD samples may differ and ETI may be subject to recall bias.

Conclusion:

Early childhood trauma exacerbated activations in stress-responsive limbic and cognitive brain areas with direct and indirect connections to the heart, potentially contributing to adverse outcomes in CAD patients.

Keywords: coronary artery disease, mental stress, childhood trauma, insula, hippocampus, cardiovascular

INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the leading cause of mortality in the United States (Benjamin et al., 2018). Prevalence of CAD is known to increase in the presence of traditional risk factors (Benjamin et al., 2018); however, emerging evidence indicates emotional risk factors such as mental stress (Wei et al., 2014), depression (Davidson, 2008; Rugulies, 2002; Vaccarino et al., 2009; Wulsin and Singal, 2003), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Turner et al., 2013; Vaccarino and Bremner, 2013a; Vaccarino et al., 2013) may also contribute to CAD development. The exact mechanism by which emotional factors increase CAD risk are unclear; however, there are likely neurobiological (Bremner, 2003; Vaccarino and Bremner, 2017), endocrine (Kalmakis et al., 2015), and psychosocial (Davidson, 2008; Strike and Steptoe, 2005) components.

Early childhood trauma, including physical, emotional, sexual abuse, and other traumas before the age of 18 (Bremner et al., 2007; Suglia et al., 2018). Traumatic events experienced during childhood can have deleterious consequences through adulthood such as hypo/hypersecretion of cortisol (Anda et al., 2006; Gunnar and Quevedo, 2007; Kalmakis et al., 2015; Yehuda, 2006), dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPAA) (Yehuda, 2002), and impaired cognitive function (Lupien et al., 2009) potentially coalescing into psychiatric conditions such as PTSD or depression (Bremner et al., 2007; Gunnar and Quevedo, 2007). Neurobiological consequences of trauma exposure during childhood may also impair development within brain regions such as the prefrontal cortex (Lupien et al., 2009) and hippocampus (Bremner, 2003) which exert negative feedback on the HPAA (Bremner, 2003; Brydges et al., 2018). These adverse of effects of early childhood also appear in a graded manner, as greater number of trauma events are related to increased memory impairment, perceived stress, and greater difficulty controlling anger (Anda et al., 2006).

The cumulative neurobiological effects of early childhood trauma have recently been understood to adverse impact health in adulthood (Brown et al., 2009). Early childhood trauma independently increases cardiovascular disease risk and is also linked with increased risk of hypertension, myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke later in life (Bremner and Vaccarino, 2015; Dong et al., 2004a; Dong et al., 2004b; Goodwin and Stein, 2004; Korkeila et al., 2010; Rich-Edwards et al., 2012; Vaccarino and Bremner, 2013b), as well as increased mortality (Brown et al., 2009). This increased cardiovascular disease risk likely results from neuro- endocrinological and behavioral hyperresponsiveness occurring during stressful or traumatic events (Weber and Reynolds, 2004) along with altered basal HPAA regulation and glucocorticoid levels (Lupien et al., 2009) persisting into adulthood and potentially occurring as a result of impaired prefrontal cortex and hippocampus development of neural, endocrine, and immune correlates of early childhood trauma (Anda et al., 2006; Bremner, 2003; Danese and McEwen, 2012). Exacerbated neurobehavioral responses can elicit episodes of acute coronary syndrome (Davidson, 2008) although the triggers eliciting these events is poorly understood. Better understanding the genesis of exacerbated neurobehavioral events are is important; a meta-analysis found adverse behavioral events significantly elevate the risk ratio (> 3) for immediate (within 2 h) adverse cardiovascular events (Mostofsky et al., 2014).

One method to induce acute psychological stress is via mental stress. These paradigms include mental arithmetic (performing arithmetic under time pressure with negative feedback) and public speaking (Bremner et al., 2018; Hammadah et al., 2017b; Ramadan et al., 2013; Sheps et al., 2002; Specchia et al., 1984; Sullivan et al., 2018; Vaccarino et al., 2018; Vaccarino et al., 2016). Evidence for the effects of psychological stress on neurohormonal systems following exposure to childhood trauma has been demonstrated previously, with increased hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to both traumatic memory stressors in women with abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder (Elzinga et al., 2003) and public speaking stressors in women with abuse and depression (Heim et al., 2000). Previously, in CAD patients, we have shown that mental stress activates areas within the inferior frontal gyrus and parietal cortex while deactivating areas within the pre- and postcentral gyrus, cerebellum, fusiform gyrus, and lingual gyrus (Bremner et al., 2018). Thus, mental stress appears to modulate brain activity in limbic, cognitive, and autonomic brain areas responding to the dual cognitive and emotional stress elicited by the tasks. However, whether early childhood trauma alters neural responses to acute mental stress within CAD patients is not well understood.

The purpose of this study was to examine whether a history of early childhood trauma is related to neural responses to mental stress in CAD patients. We hypothesized that early childhood trauma will increase brain activations and deactivations in brain areas previously identified to be involved in mental stress in CAD patients (Bremner et al., 2018) and implicated in the neural circuits of early trauma (Bremner, 2005; Bremner and Vaccarino, 2015): anterior cingulate, medial prefrontal cortex, insula, and the cerebellum.

METHODS

Participant Population

Participants in this study were drawn from the Mental Stress Ischemia Prognosis Study (MIPS) (Hammadah et al., 2017a). Participants were all between the ages of 30 and 79 and had confirmed CAD. Participants in MIPS were recruited at Emory University Hospital, Grady Memorial Hospital, and the Atlanta VA Medical Center between September 2010 and September 2016. CAD was defined as having a history of myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting, or percutaneous coronary intervention at least one year prior to the study, or a positive nuclear stress test. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, high blood pressure (systolic ≥ 180 or diastolic ≥ 100 mm Hg), recent acute coronary syndrome, history of a severe mental disorder (including schizophrenia, psychosis, bipolar disorder, substance dependence within 1 year), history of loss of consciousness > 1 min, history of neurological disorder (i.e., Parkinson’s disease, dementia, stroke), or contraindications to regadenoson. Certain medications were withheld for 12 hours (calcium channel blockers, nitrates) or 24 hours (beta-adrenergic antagonists) prior to the study. If withholding medication was considered harmful to the participant, they were excluded from the study. Those with mental stress ischemia and depression were oversampled in the brain sub-study of MIPS. All participants provided written consent and the study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Mental Stress

As part of the larger MIPS study (Hammadah et al., 2017a), all participants completed the Early Trauma Inventory (ETI, described below) and physical screening during a preliminary visit. Participants then returned for a second visit (within one week) during which mental stress testing and brain imaging were completed. Participants were scanned during four conditions: a control task for mental math (counting out loud), a control task for public speaking (talking about a neutral event), a stressful mental math task, and a stressful public speaking task. Control tasks were completed first, and the order of stressful tasks were counterbalanced. Each task was completed twice for a total of eight position emission tomography (PET) images per participant. The stressful mental math task included calculating increasingly difficult math problems with addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division while an administrator in a white lab coat provided negative feedback (Bremner et al., 2003). The difficulty of mental math was increased until participants incorrectly answered three successive problems. The stressful public speaking task required participants to prepare (two minutes) and present (two minutes) a speech in response to two stressful interpersonal situations (Bremner et al., 2018). The speech was presented to a video camera and audience wearing white coats and participants were told the content and duration would be evaluated. Blood pressure and heart rate were recorded at one-minute intervals during the control and stress tasks using an automated oscillometric device.

Psychometric Assessment

Patients were assessed with the short form of the Early Trauma Inventory-Self Report (ETI-SR-SF) questionnaire, a validated instrument for the assessment of trauma incurred before the age of 18 (Bremner et al., 2007; Bremner et al., 2000). The ETI-SR-SF consists of 27 items requiring a binary response (yes or no) and separated into four subcomponents (General, Physical, Emotional, and Sexual Trauma) based on previously established criteria (Bremner et al., 2000). The number of positive responses (indicating presence of trauma) were summed for the ETI-SR-SF total score with totals for each subcomponent also calculated. Individual items and endorsement frequency separated by ETI status is presented in Supplementary Table 1. The threshold for determining presence of early childhood trauma was the ETI-SR-SF total score plus one standard deviation from healthy controls (Bremner et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2013a). This resulted in a threshold value of 7 for classifying as having early childhood trauma (ETI+; ≥ 7 total score) and absence of early childhood trauma (ETI−; < 7 total score). Prior studies demonstrated the validity of this cut-point in differentiating patients as abused versus non-abused based on cardiovascular outcomes relevant to the long-term physical effects of early trauma (Zhao et al., 2013b). All participants also completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) for self-reported measurement of depressive symptoms (Beck et al., 1996). PTSD presence was examined using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First and Gibbon, 2004). Presence of mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia (MSIMI) was identified using previous methodology (Bremner et al., 2018).

Neuroimaging

High Resolution Positron Emission Tomography (HR-PET brain imaging was completed using a High Resolution Research Tomograph (HR-PET) (CTI, Knoxville, TN), which has a spatial resolution of 2 mm (Schmand et al., 1999). Brain perfusion was assessed to quantify regional activation in response to the stressful and control tasks. Ten seconds into each PET scan, 20 mCi of radio-labeled water (H2[O15]), produced in an on-site cyclotron, was injected to measure blood perfusion within the brain. Each scan lasted for two minutes and electrocardiogram and vital signs were continuously monitored with physician present.

Image Analysis

All HR-PET images were analyzed similar to previous research (Bremner et al., 2018) using statistical parametrical mapping (SPM8; www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). First, a mean intensity image was created from the eight individual scans. Each individual scan was then spatially normalized to this mean, transformed into a common anatomical space (SPM8 PET Template), smoothed with a three-dimensional Gaussian filter to 5-mm full width half maximum, and normalized to whole brain activity. Next, a first level (individual) model was computed using the four control and four mental stress scan conditions. The model was grand mean scaled, estimated, and contrasts computed for both areas of activation (stress – control) and deactivation (control – stress). Second level (between-participant) analyses were computed using the t-contrast images generated from the first level analysis with data grouped by ETI-SR-SF status. The second level analyses included covariates of age and mental stress induced myocardial ischemia (MSIMI) presence given the known relationship to altered neurological responses to mental stress within those with CAD (Bremner et al., 2018). In addition, regions of activity were extracted from the contrast maps and compared to the ETI-SR-SF total scores. A second, voxel-wise regression analysis, was conducted on the areas of brain activation using the SPM8 multiple regression design.

Statistical Analysis

Normality of data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test within R (v3.4.0; www.r-project.org). Descriptive statistics were recorded for the entire study sample along with ETI+ and ETI− subgroups (Table 1). Descriptive comparisons between ETI+ and ETI− groups were completed using a two-sample t-test or Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test for continuous variables or chi-square test for discrete variables. For heart rate and blood pressure data, a linear mixed effects model was fitted using the lmer package within R (cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lme4) with fixed effects for ETI-SR-SF presence and task type (stress or control) and a random effect for participant. If any significant main effects were observed, pairwise post-hoc contrasts with Bonferroni-Holm corrections were completed using the lsmeans package in R (cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lsmeans). For regional brain blood flow analyses, comparison contrasts between areas of greater activation and deactivation between ETI+ and ETI− were coded according to previous guidelines (Gläscher and Gitelman, 2008) and produced images where individual voxels correspond to the between group t-statistic. Furthermore, the between-group contrast images were masked with the overall (collapsed across ETI-SR-SF status) activation/deactivation maps to limit Type I error rates. Significant voxel clusters for all brain analyses were identified using a threshold of p < 0.005 (uncorrected) which has been shown to minimize both Type I and Type II errors in brain imaging research (Lane et al., 1997; Reiman et al., 1997). Additionally, areas of significant activation were constrained to clusters with a minimum voxel cluster size greater than ten. Significant cluster locations were identified using the distance from the anterior commissure in millimeters with x, y, and z coordinates transformed from the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) coordinates to those of the Talairach stereotaxic atlas (Talairach and Tournoux, 1988). The a priori α level for non-brain imaging data was chosen at 0.05. All data are presented as mean ± SD.

Table 1.

Demographic information for study participants (n = 152) separated by early childhood trauma presence (ETI+) or absence (ETI−).

| ETI+ (n = 80) | ETI− (n = 72) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y (mean ± SD) | 60.7 ± 8.2 | 64.2 ± 8.2 * | 0.005 |

| Women (%) | 39 | 25 | 0.07 |

| African American (%) | 36 | 33 | 0.71 |

| Body Mass Index, kg·m−2 (mean ± SD) | 30.7 ± 6.3 | 29.8 ± 5.7 | 0.41 |

| Hypertension (%) | 74 | 78 | 0.56 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 83 | 83 | 0.89 |

| Diabetes (%) | 34 | 35 | 0.90 |

| Myocardial Infarction (%) | 35 | 36 | 0.89 |

| Heart Failure (%) | 8 | 20 * | 0.04 |

| Smoking (%) | 0.52 | ||

| Never Smoked | 33 | 33 | |

| Quit Smoking | 50 | 56 | |

| Current Smoker | 17 | 11 | |

| Medications (%) | |||

| Anti-Depressants | 46 | 22 * | 0.002 |

| ACE Inhibitors | 41 | 47 | 0.46 |

| Angiotensin Receptor Inhibitors | 15 | 14 | 0.85 |

| Diuretics | 14 | 8 | 0.29 |

| Vasodilators | 6 | 8 | 0.62 |

| Anxiolytics | 89 | 86 | 0.62 |

| β-Blockers | 74 | 72 | 0.83 |

| Statins | 89 | 92 | 0.55 |

| Education Level, y (mean ± SD) | 15.8 ± 4.3 | 14.4 ± 3.0 | 0.06 |

| Annual Household Income (%) | 0.62 | ||

| < $20,000 | 21 | 17 | |

| $20,000 – $34,999 | 20 | 15 | |

| $35,000 – $49,999 | 11 | 10 | |

| $50,000 – $99,999 | 21 | 21 | |

| >$100,000 | 22 | 26 | |

| Do Not Know | 5 | 11 |

p < 0.05 difference from ECT-. ACE = Angiotensin-converting enzyme

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the participant demographic information for the study separated by ETI− SR-SF status. The study sample included 53 African-Americans (34.9 %) and 49 females (32.2 % of all participants). The ETI+ participants were younger than ETI−, had greater rates of anti-depressant usage, and fewer instances of previous heart failure vs. ETI−. No significant differences were observed between ETI− and ETI+ for race, body mass index, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, prior myocardial infarction, smoking status, medications, education history, or family income. Table 2 describes the psychometric evaluation scores for both ETI+ and ETI− participants. ETI+ participants reported greater BDI and ETI-SR-SF scores compared to ETI−, although depression scores suggested only ‘mild depression’ according to published guidelines (Beck et al., 1996). Most (> 65%) ETI+ participants experienced severe physical abuse including items: slapped in the face, pushed or shoved, punched or kicked (Supplementary Table 1). ETI+ participants also had prevalent (>50%) endorsement rates of general trauma (witness violence, serious injury/death of friend, serious personal injury) and emotional abuse items (put down/ridiculed, ignored, parent fail to understand needs) (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 2.

Psychometric Scores (mean ± SD) for participants with coronary artery disease (n = 152) separated by early childhood trauma presence (ETI+) or absence (ETI−) as measured by the Early Child Trauma Inventory Self Report Short Form (ETI-SR-SF).

| ETI+ (n = 80) | ETI− (n = 72) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beck Depression Inventory | 16.6 ± 12.5 | 7.9 ± 8.3 | < 0.0001 |

| PTSD Diagnosis | 17.5% | 9.7% | 0.17 |

| Current PTSD | 12.5% | 5.6% | 0.14 |

| ETI-SR-SF Total Score | 11.8 ± 4.2 | 3.3 ± 2.6 | < 0.0001 |

| General Trauma | 4.7 ± 2.4 | 1.5 ± 1.7 | < 0.0001 |

| Physical Trauma | 3.1 ± 1.5 | 1.3 ± 1.3 | < 0.0001 |

| Emotional Trauma | 2.6 ± 1.9 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Sexual Trauma | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 0.2 ± 0.6 | < 0.0001 |

Heart rate was significantly increased during acute mental stress (2.4 ± 6.4 bt·min−1) compared to control (−0.1 ± 5.5 bt·min−1) tasks (p < 0.001). ETI+ (2.5 ± 7.0 bt·min−1) and ETI− (2.3 ± 5.6 bt·min−1) exhibited similar increases in heart rate during acute mental stress (p = 0.16). Similarly, systolic blood pressure increased significantly (p < 0.0001) during acute mental stress (5.3 ± 13.0 mmHg) compared to control (−3.6 ± 11.1 mmHg) tasks (p < 0.001). ETI+ (3.8 ± 12.5 mmHg) and ETI− (6.9 ± 13.5 mmHg) exhibited similar increases in heart rate during acute mental stress (p = 0.13).

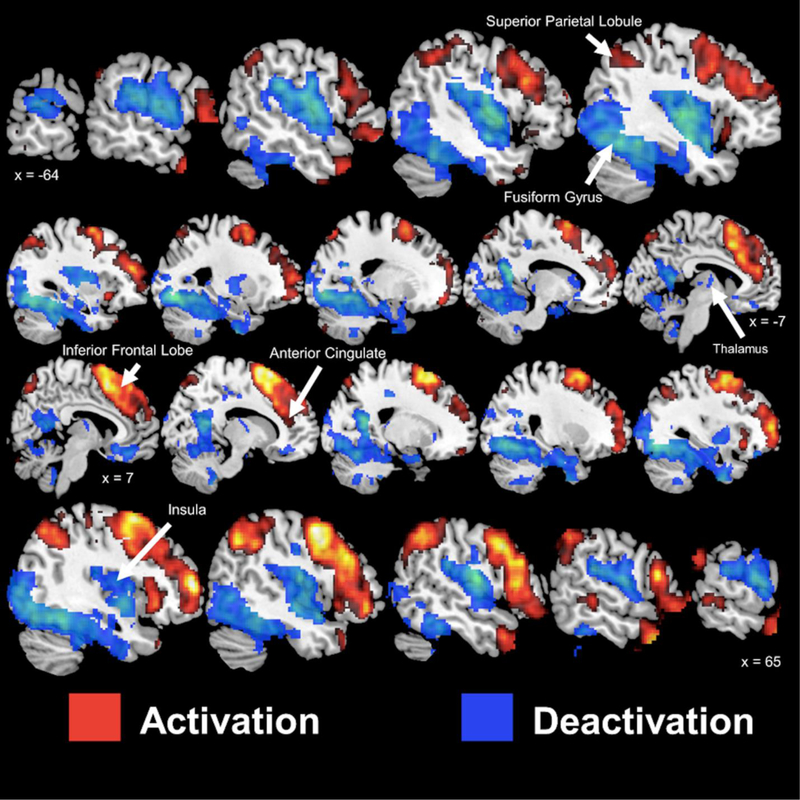

Figure 1 presents the activation and deactivation patterns during mental stress irrespective of ETI-SR-SF status. Areas of activation were observed within bilateral frontal lobe (inferior, medial, and superior gyrus), bilateral temporal lobe (middle, inferior, pole), bilateral parietal cortex (inferior, superior, and precuneus), bilateral anterior cingulate, and the bilateral posterior cerebellum. In contrast, areas of deactivation were observed within the bilateral temporal lobes (Hechel’s gyrus, superior gyrus), bilateral occipital lobe (superior, medial gyrus), bilateral frontal lobe (medial orbital gyrus), bilateral postcentral gyrus, bilateral insula, bilateral thalamus, left putamen, left caudate, bilateral hippocampus, right medial and posterior cingulate gyrus, bilateral cerebellum (anterior, posterior, and vermis).

Figure 1.

Sagittal slices of significant (p < 0.005) activation (red) and deactivation (blue) during mental stress in participants with coronary artery disease. Talairach x coordinates are presented to indicate slice location. Negative and positive Talairach coordinates indicate left and right hemisphere, respectively.

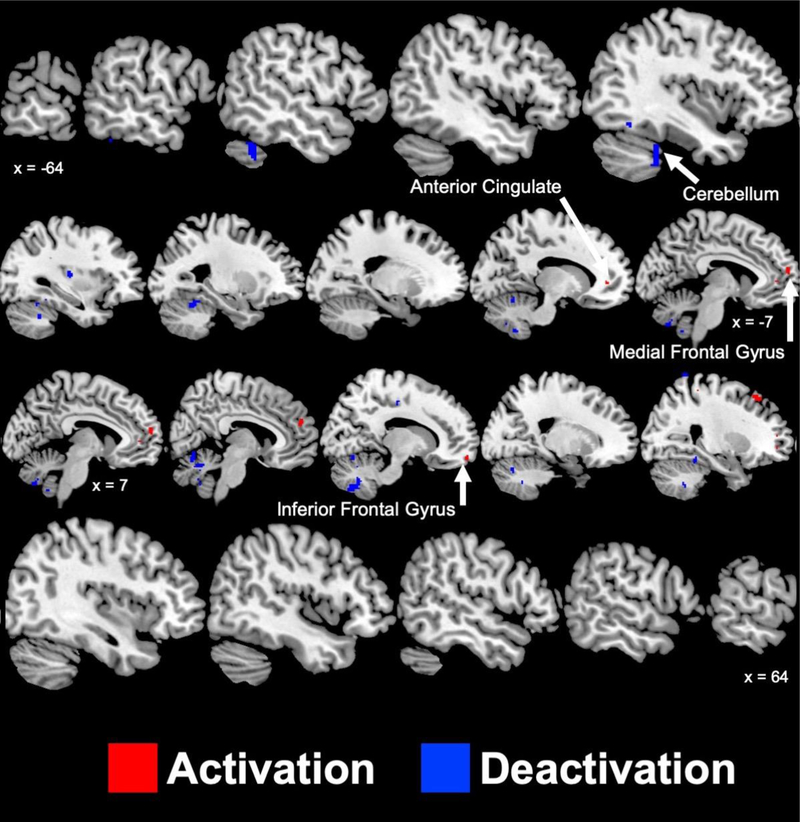

Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 2 present the brain areas with greater (p < 0.005) mental stress induced activation and deactivation in ETI+ compared to ETI− participants. ETI+ participants experienced greater activations within the left anterior cingulate and the right (middle, medial, and superior gyri) and left (medial gyrus) frontal lobes compared to ETI−. ETI+ also experienced greater deactivations within the left insula, left parahippocampal gyrus, right dorsal anterior cingulate gyrus, bilateral anterior and posterior cerebellum, bilateral fusiform gyrus, and right postcentral gyrus.

Figure 2.

Sagittal slices of significant (p < 0.005) areas with greater activation (red) and deactivation (blue) during mental stress in participants with coronary artery disease who have experienced early childhood trauma compared to those who have not. Talairach x coordinates are presented to slice indicate location. Negative and positive Talairach coordinates indicate left and right hemisphere, respectively.

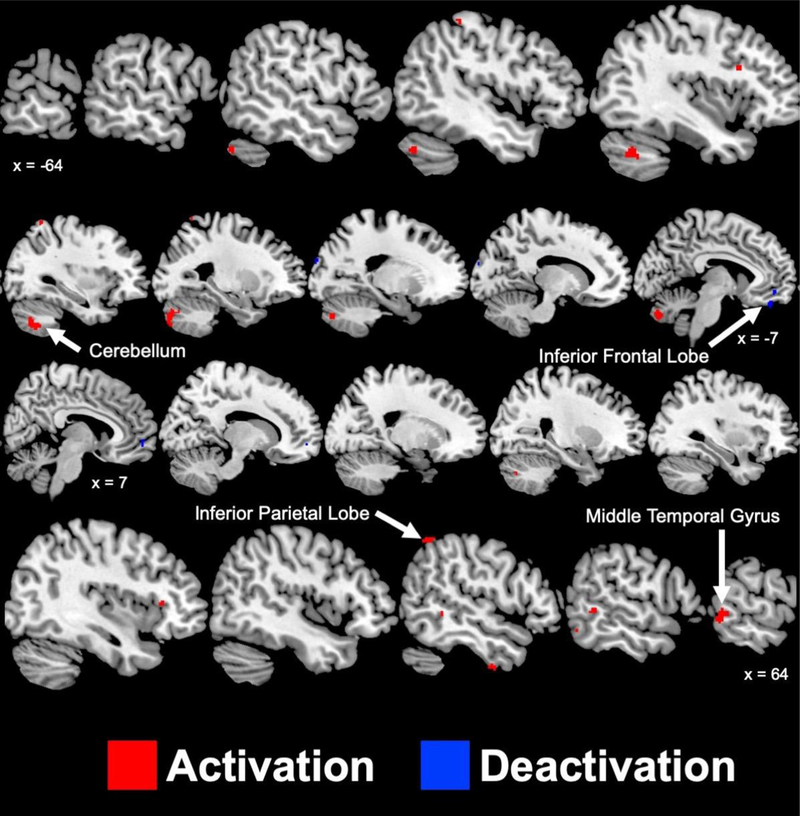

Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 3 present the brain areas with greater (p < 0.005) mental stress-induced activation and deactivations in ETI− compared to ETI+ participants. ETI− participants experienced greater activations within the right parietal lobe (inferior lobule), left postcentral gyrus, right temporal lobe (inferior and medial gyrus), right inferior frontal gyrus, and bilateral cerebellum. ETI− experienced greater deactivations within the left frontal lobe (medial and orbital gyrus), right frontal lobe (medial gyrus), and the left occipital lobe.

Figure 3.

Sagittal slices of significant (p < 0.005) areas with greater activation (red) and deactivation (blue) during mental stress in participants with coronary artery disease who have not experienced early childhood trauma compared to those who have. Talairach x coordinates are presented to indicate slice location. Negative and positive Talairach coordinates indicate left and right hemisphere, respectively.

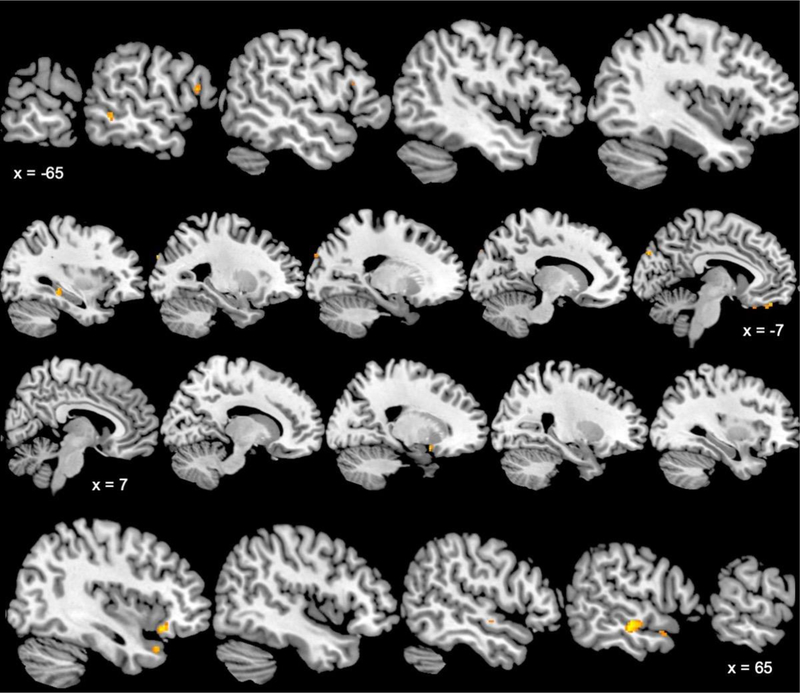

Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 4 present areas with significant positive correlations between brain activations during mental stress and ETI-SR-SF total score. Thus, these areas were more active in individuals with a greater level of childhood trauma. Significant positive relationships between brain activations and total ETI-SR-SF scores were observed within the left hippocampus, bilateral frontal lobe, left occipital cuneus, and bilateral temporal lobe (middle gyrus, right superior gyrus).

Figure 4.

Sagittal slices of brain areas with significant (p < 0.005, minimum cluster size of 11 voxels) positive relationships between mental stress activation level and early childhood trauma inventory total score in participants with coronary artery disease. Talairach x coordinates are presented to indicate slice location. Negative and positive Talairach coordinates indicate left and right hemisphere, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This study showed that early childhood trauma results in altered central neurologic responses to acute mental stress in patients with CAD. Specifically, CAD patients with early childhood trauma had increased activity in brain areas involved in emotional regulation and also in areas involved in autonomic responses to stress which could contribute to worsened CAD prognosis (Kraynak et al., 2018): the bilateral insula, anterior cingulate/medial prefrontal cortex, and cerebellum. These findings help to explain the mechanisms behind the physiologic effects of early traumatic exposures observed in other studies (Otte et al., 2005; Suglia et al., 2018), and support the growing body of evidence that early traumatic exposures may result in a catastrophic effect on the body and mind that may last throughout the life of certain individuals (Felitti et al., 1998; Goodwin and Stein, 2004).

CAD patients with early childhood trauma had increased activations with stress (mental arithmetic and public speaking) in areas comprising the neural network for the identification of environmental threats for survival: thalamus, sensory cortex, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus (Danese and McEwen, 2012). ETI+ participants exhibited greater activations within the medial prefrontal cortex (anterior cingulate, frontal lobe) which appears sensitive to increased emotional stress in those with early sexual trauma and PTSD (Bremner et al., 1999). Medial prefrontal activity and severity of early childhood trauma has also previously correlated with the anticipation of aversive shocks in individuals with depression (Duncan et al., 2015). This gradation in activity, combined with resting-state brain analysis, was hypothesized to be evidence of childhood trauma modulating activation of the neural network involving the medial frontal cortex, insula, and motor cortex which processes adverse stimuli (Duncan et al., 2015). In the current study, CAD patients with early childhood trauma likewise experienced greater activations within the medial frontal and motor cortices and greater deactivations within the posterior insula. The insula is also part of the salience network, a large-scale network responsible for detecting and integrating emotional information (Marusak et al., 2015; Peters et al., 2016). Saliency network activity and connectivity is elevated in adults with major depression, PTSD, and anxiety (Paulus and Stein, 2006; Peters et al., 2016). Altered insula activity, in combination with the anterior cingulate, likely indicates increased anxiety during cognitive testing (Gasquoine, 2014) and has been associated with both early trauma (Teicher et al., 2014) and PTSD (Bruce et al., 2013; Nicholson et al., 2016). Therefore, our data suggest that, within participants with CAD, early childhood trauma elicits activity within brain areas which mediate stress following mental arithmetic and public speaking. That early childhood trauma upregulates the stress responses during these challenges is an important finding, as emotional factors (including moderate to severe stress) increases risk for adverse cardiovascular events (Strike and Steptoe, 2005) including mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia (Bremner et al., 2018).

The presence of early childhood trauma within our CAD sample elicited greater activations in brain areas known to be involved within task-specific high-order processing. This appears to align with previous studies (Petkus et al., 2018; Saleh et al., 2017) indicating early childhood trauma may impair processing speed, attention, executive function, and working memory in adults without CAD. While we do not have performance measures within the given study, greater neural activity within task-specific regions potentially indicates cognitive deficiency or, at a minimum, more effortful cognitive processing. Early childhood trauma elicited greater mental stress deactivations in the posterior lobes of the cerebellum, an area known to be involved within emotional and cognitive processing (Leiner et al., 1989). Furthermore, the cerebellum is reciprocally connected to the frontal lobe (Brodmann areas 8, 44, 45) and motor cortices (Brodmann areas 4 and 6) (Leiner et al., 1989); we found early childhood trauma altered activity within Brodmann areas 8 and 45. While we recognize the highly debated nature of cerebellar contributions to emotion and cognition (Koziol et al., 2014; Marien et al., 2014), the widely distributed deactivations in those with early childhood trauma likely indicate a multimodal impact on neural processes required to complete the mental stress tasks. One such modality is working memory (Koziol et al., 2014). Working memory demands primarily invoke fronto-parietal network activity (Eriksson et al., 2015) to accomplish encoding and responses, but the posterior cerebellum assists within verbal rehearsal mechanisms (Koziol et al., 2014). Mental arithmetic and public speaking tasks are heavily reliant on verbal working memory (Acheson and MacDonald, 2009), and thus the greater frontal lobe and cerebellum activity observed in participants with early childhood trauma appears to challenge much of the working memory network when producing accurate responses (correct answer, cogent argument).

Altered activity within the posterior cerebellum in with early childhood trauma may also represent more effortful language and speech production (Marien et al., 2014; Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2009). A basic model of speech production outlined previously (Marien et al., 2014), indicates speech-specific neural information originating in Broca’s area (Brodmann area 44), which synapses onto the insula, then to both the cerebellum and caudate nucleus before connecting to the premotor cortex and terminating at the primary motor cortex for speech production. Interestingly, we observed that left inferior frontal gyrus (Brodmann area 44) activation positively correlated with ETI-SR-SF score, which, when combined with the greater deactivations within the cerebellum, potentially suggest a dysregulation of this basic neural network in individuals with early childhood trauma. Furthermore, dysregulation of this network (specifically the insula) may also predict cognitive impairments, as has been observed in young individuals who have experienced trauma compared to match participants without trauma during an emotional congruency task (Marusak et al., 2015).

The second important finding of this study is CAD patients with early childhood trauma experienced greater activations in areas known to be implicated with psychological- and emotion-mediated increases in cardiovascular disease risk (Kraynak et al., 2018). Specifically, the anterior cingulate cortex, hippocampus, ventral medial prefrontal cortex, and insula appear to constitute a neural network which connects limbic and cortical structures to the peripheral vasculature (Kraynak et al., 2018; Nagai et al., 2010). Presence of early childhood trauma resulted in greater left insula deactivations and severity positively correlated with left hippocampus and ventromedial prefrontal cortex activity. Furthermore, within CAD patients, insula activity correlates positively with stress-induced peripheral vasoconstriction (Shah et al., 2018) which has been linked to mental stress ischemia (Hammadah et al., 2017b). During autonomic processing, the insula receives interoceptive information from a specialized spinothalamocortical tract which assists in the cortical representation of salient visceral and somatosensory information (Critchley, 2005). The left insula regulates general autonomic functioning (Oppenheimer and Cechetto, 2016) by gating parasympathetic activity (Gray et al., 2009). The hippocampus, however, appears to directly mediate cardiovascular responses (Myers, 2017) through glutamatergic connections to the thalamus and hypothalamus. This is evidenced by stimulation of the hippocampus, in combination with an intact medial prefrontal cortex, decreased heart rate and mean arterial pressure in rats (Ruit and Neafsey, 1988). Secondly, in addition to this corticolimbic circuitry, CAD patients with early childhood trauma increased brain activity in areas which activate with acute mental stress and are related to elevated sympathetic responses: postcentral gyrus and middle temporal gyrus (Critchley et al., 2000). Thus, the presence of multiple related brain regions correlating with the severity of early childhood trauma indicates altered regulation of autonomic (and potentially cardiovascular) responses during acute mental stress in CAD patients. We acknowledge early childhood trauma did not alter cardiovascular responses (heart rate, blood pressure) within this study. However, the observed changes during mental stress were smaller than similar mental stress challenges (Critchley et al., 2000) and are hypothesized to be likely due, in part, to the high prevalence (~75%) of medication usage which decreases heart rate (e.g., beta-blockers) in our CAD sample.

In addition to increased emotional and autonomic challenges, the third important finding of this study was that early childhood trauma elicited changes in brain areas which could indicate chronic altered regulatory or homeostatic state in participants with CAD. Specifically, the current study was consistent with prior brain imaging studies in victims of childhood abuse and related traumas (Baker et al., 2013; Bremner, 2002; Saleh et al., 2017). Previously, early childhood trauma has been reported to reduce volume of the insula (Baker et al., 2013), frontal lobe (Andersen et al., 2008), hippocampus (Brydges et al., 2018; Teicher et al., 2012), and anterior cingulate (Baker et al., 2013; Kasai et al., 2008; Kitayama et al., 2006) in adults. It has been hypothesized these morphological differences result from neuron loss, decreases in dendritic branching or spine density, or decreases neurogenesis with early childhood trauma (Baker et al., 2013) which are likely subjugated by an elevated stress response (i.e., increased/prolonged HPAA activation) within the developing brain (Twardosz and Lutzker, 2010). Early childhood trauma may also alter functional connectivity within these areas, as demonstrated by altered inhibitory control between the inferior frontal lobe and dorsal anterior cingulate (Elton et al., 2014). Early childhood trauma also appears to decrease volume of the corpus callosum (Kitayama et al., 2007; Teicher et al., 2004), potentially from stress-induced glial cell dysfunction resulting in inadequate myelination (Twardosz and Lutzker, 2010). In addition to morphological changes, others have suggested altered connectivity may also result from impaired synaptic (glutamatergic) transmission and impaired assembly of neurons required to for multi-modal processing (Negron-Oyarzo et al., 2016); these changes may also explain the cognitive impairments occurring concomitant to decreased volumes (Baker et al., 2013). The exacerbated activity within areas required for normal endocrine function is important given the elevated CAD risk from chronic HPAA dysregulation following early childhood trauma (Kalmakis et al., 2015). Areas with early childhood trauma-mediated volume reductions (insula, anterior cingulate, frontal lobe) may also contribute to CAD development by insufficient regulation of the hypothalamus (Thayer and Lane, 2009).

While this study has clear strengths of large sample size with current coronary artery disease, utilization of a high-resolution PET scanner to locate areas of activations, and usage of a previously validated measure of early childhood trauma, several limitations persist. First, one limitation is that, because a non-CAD sample was not included in the current study, findings from our sample are not generalizable to non-CAD populations. Nonetheless, CAD is a prevalent condition and the population is high risk which underscores the public health relevance of these findings. Furthermore, recent reviews (Kraynak et al., 2018) have also emphasized the importance of investigating neural mechanisms of cardiovascular disease risks in clinical samples. Second, we do not have volumetric data on participants and therefore inferences regarding potential changes in brain area volume (e.g., hippocampus) and activity were not possible. Third, trauma was a self-reported measure, the ETI-SR-SF, which may have biased our results towards the null through non-differential recall bias. Additionally, the ETI-SR-SF does not include information on trauma chronicity and severity by item or developmental epoch. These aspects of trauma assessment, however, are covered in the long version of the ETI-SR, and the ETI-SR-SF has been validated against that measure (Bremner et al., 2007). Thus, ETI-SR-SF severity score is a good indicator of trauma severity, and is a validated measure for detecting early childhood trauma, and, by creating the threshold for ETI+ two standard deviations from the ETI−, we were able to separate those with and without clinically significant early trauma with 95% confidence. Finally, it should be emphasized that our measurements of stress-induced brain activations in specific regions does not imply a causal relationship between these activations and changes in cardiac activity. Determination of the exact mechanism by which stress is processed by the brain resulting in changes in the heart was beyond the scope of the present study.

In summary, this study uniquely addressed the influence of early childhood trauma on brain activity during mental stress in participants with cardiovascular disease. This study made the following novel observations: (1) within those with CAD, the presence of early childhood trauma is associated with altered brain activations, (2) altered neural activity with early childhood trauma involve areas known to be implicated in cognitive, sensory, and autonomic processing, (3) activity within some brain areas, specifically the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, appear to be associated with early child trauma severity. These findings suggest that childhood trauma can exacerbate neural changes to mental stress in areas that, as shown in our previous studies (Bremner et al., 2018; Shah et al., 2018), may also be involved within adverse cardiovascular responses. Whether these findings are applicable to non-CAD populations merits further investigation.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS:

Early childhood trauma increases brain activity in response to acute mental stress

Brain areas with increased activity indicate upregulation of chronic stress response

Early childhood trauma severity was positively associated with hippocampus activity

Acknowledgements:

This study was supported by National Institute of Health [P01 HL101398, HL088726, MH076955, MH067547-01, MH56120, RR016917, HL077506, HL068630, HL109413, HL125246, and HL127251]. We wish to acknowledge Margie Jones, C.N.M.T., for assistance with imaging and analysis procedures and Nancy Murrah, R.N., Lucy S. Shallengerger, Janice Parrott, R.N., Karen Sykes, and Steve Rhodes, R.N., for assistance with patient assessments and clinical research.

Role of Funding Source

This study was supported by National Institute of Health [P01 HL101398, HL088726, MH076955, MH067547-01, MH56120, RR016917, HL077506, HL068630, HL109413, HL125246, and HL127251]. Funding sources had no involvement in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article.

Financial Disclosures:

Matthew T. Wittbrodt Ph.D, reports no direct or indirect financial or personal relationships, interests, or affiliations relevant to the subject matter of the manuscript that have occurred over the past two years, or that are expected in the foreseeable future. This disclosure includes, but is not limited to, grants or funding, employment, affiliations, patents (in preparation, filed or granted), inventions, honoraria, consultancies, royalties, stock options/ownership, or expert testimony.

Kasra Moazzami MD, reports no direct or indirect financial or personal relationships, interests, or affiliations relevant to the subject matter of the manuscript that have occurred over the past two years, or that are expected in the foreseeable future. This disclosure includes, but is not limited to, grants or funding, employment, affiliations, patents (in preparation, filed or granted), inventions, honoraria, consultancies, royalties, stock options/ownership, or expert testimony.

Bruno B. Lima MD Ph.D, reports no direct or indirect financial or personal relationships, interests, or affiliations relevant to the subject matter of the manuscript that have occurred over the past two years, or that are expected in the foreseeable future. This disclosure includes, but is not limited to, grants or funding, employment, affiliations, patents (in preparation, filed or granted), inventions, honoraria, consultancies, royalties, stock options/ownership, or expert testimony.

Zuhayr S. Alam, reports no direct or indirect financial or personal relationships, interests, or affiliations relevant to the subject matter of the manuscript that have occurred over the past two years, or that are expected in the foreseeable future. This disclosure includes, but is not limited to, grants or funding, employment, affiliations, patents (in preparation, filed or granted), inventions, honoraria, consultancies, royalties, stock options/ownership, or expert testimony.

Daniel Corry MPH, reports no direct or indirect financial or personal relationships, interests, or affiliations relevant to the subject matter of the manuscript that have occurred over the past two years, or that are expected in the foreseeable future. This disclosure includes, but is not limited to, grants or funding, employment, affiliations, patents (in preparation, filed or granted), inventions, honoraria, consultancies, royalties, stock options/ownership, or expert testimony.

Muhammad Hammadah MD, reports no direct or indirect financial or personal relationships, interests, or affiliations relevant to the subject matter of the manuscript that have occurred over the past two years, or that are expected in the foreseeable future. This disclosure includes, but is not limited to, grants or funding, employment, affiliations, patents (in preparation, filed or granted), inventions, honoraria, consultancies, royalties, stock options/ownership, or expert testimony.

Carolina Campanella PhD, reports no direct or indirect financial or personal relationships, interests, or affiliations relevant to the subject matter of the manuscript that have occurred over the past two years, or that are expected in the foreseeable future. This disclosure includes, but is not limited to, grants or funding, employment, affiliations, patents (in preparation, filed or granted), inventions, honoraria, consultancies, royalties, stock options/ownership, or expert testimony.

Laura Ward, reports no direct or indirect financial or personal relationships, interests, or affiliations relevant to the subject matter of the manuscript that have occurred over the past two years, or that are expected in the foreseeable future. This disclosure includes, but is not limited to, grants or funding, employment, affiliations, patents (in preparation, filed or granted), inventions, honoraria, consultancies, royalties, stock options/ownership, or expert testimony.

Arshed A. Quyyumi MD, reports research support from NIH grants P01 HL101398 and R33 HL138657. Otherwise he reports no other direct or indirect financial or personal relationships, interests, or affiliations relevant to the subject matter of the manuscript that have occurred over the past two years, or that are expected in the foreseeable future. This disclosure includes, but is not limited to, grants or funding, employment, affiliations, patents (in preparation, filed or granted), inventions, honoraria, consultancies, royalties, stock options/ownership, or expert testimony.

Amit J. Shah MD, receives research grant support from the NHLBI K23 HL127251. Otherwise he reports no other direct or indirect financial or personal relationships, interests, or affiliations relevant to the subject matter of the manuscript that have occurred over the past two years, or that are expected in the foreseeable future. This disclosure includes, but is not limited to, grants or funding, employment, affiliations, patents (in preparation, filed or granted), inventions, honoraria, consultancies, royalties, stock options/ownership, or expert testimony.

Viola Vaccarino MD PhD, received research grant funding support form NIH grants P01 HL101398, HL109413, MH076955, MH067547, HL077506, HL068630, HL109413, HL125246, and HL127251. Otherwise she reports no other direct or indirect financial or personal relationships, interests, or affiliations relevant to the subject matter of the manuscript that have occurred over the past two years, or that are expected in the foreseeable future. This disclosure includes, but is not limited to, grants or funding, employment, affiliations, patents (in preparation, filed or granted), inventions, honoraria, consultancies, royalties, stock options/ownership, or expert testimony.

Jonathon A. Nye Ph.D, reports no direct or indirect financial or personal relationships, interests, or affiliations relevant to the subject matter of the manuscript that have occurred over the past two years, or that are expected in the foreseeable future. This disclosure includes, but is not limited to, grants or funding, employment, affiliations, patents (in preparation, filed or granted), inventions, honoraria, consultancies, royalties, stock options/ownership, or expert testimony.

J, Douglas Bremner MD, received research grant funding support form NIH grants P01 HL101398, MH56120, RR016917, HL088726, ElectroCore LLC and the Brain Behavior Foundation. Otherwise he reports no other direct or indirect financial or personal relationships, interests, or affiliations relevant to the subject matter of the manuscript that have occurred over the past two years, or that are expected in the foreseeable future. This disclosure includes, but is not limited to, grants or funding, employment, affiliations, patents (in preparation, filed or granted), inventions, honoraria, consultancies, royalties, stock options/ownership, or expert testimony.

Viola Vaccarino MD PhD received grant funding support form NIH grants P01 HL101398, HL109413, Arshed Quyyumi MD received grant funding support form NIH grants P01 HL101398 J Douglas Bremner MD

Glossary

- ETI

Early Childhood Trauma

- ETI+

Presence of Early Childhood Trauma

- ETI−

Absence of Early Childhood Trauma

- MIPS

Mental Stress Ischemia Prognosis Study

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have financial conflict of interests to report.

References

- Acheson DJ, MacDonald MC, 2009. Verbal working memory and language production: Common approaches to the serial ordering of verbal information. Psychol Bull 135, 50–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, Dube SR, Giles WH, 2006. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 256, 174–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL, Tomada A, Vincow ES, Valente E, Polcari A, Teicher MH, 2008. Preliminary evidence for sensitive periods in the effect of childhood sexual abuse on regional brain development. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 20, 292–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LM, Williams LM, Korgaonkar MS, Cohen RA, Heaps JM, Paul RH, 2013. Impact of early vs. late childhood early life stress on brain morphometrics. Brain Imaging Behav 7, 196–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK, 1996. Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio 78, 490–498. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Delling FN, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jimenez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Lutsey PL, Mackey JS, Matchar DB, Matsushita K, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, O’Flaherty M, Palaniappan LP, Pandey A, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Ritchey MD, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P, American Heart Association Council on, E., Prevention Statistics, C., Stroke Statistics, S., 2018. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 137, e67–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, 2002. Neuroimaging of childhood trauma. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry 7, 104–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, 2003. Long-term effects of childhood abuse on brain and neurobiology. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 12, 271−+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, 2005. Effects of traumatic stress on brain structure and function: relevance to early responses to trauma. J Trauma Dissociation 6, 51–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Bolus R, Mayer EA, 2007. Psychometric properties of the Early Trauma Inventory-Self Report. J Nerv Ment Dis 195, 211–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Campanella C, Khan Z, Shah M, Hammadah M, Wilmot K, Al Mheid I, Lima BB, Garcia EV, Nye J, Ward L, Kutner MH, Raggi P, Pearce BD, Shah A, Quyyumi A, Vaccarino V, 2018. Brain Correlates of Mental Stress-Induced Myocardial Ischemia. Psychosom Med [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bremner JD, Narayan M, Staib LH, Southwick SM, McGlashan T, Charney DS, 1999. Neural correlates of memories of childhood sexual abuse in women with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 156, 1787–1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Vaccarino V, 2015. Neurobiology of early life stress in women., In: Orth-Gomér K, Schneiderman N, Vaccarino V, Hans-Christian D (Eds.), Psychosocial Stress and Cardiovascular Disease in Women: Concepts, Findings, Future Perspectives . Springer International Publishing, pp. 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Vermetten E, Mazure CM, 2000. Development and preliminary psychometric properties of an instrument for the measurement of childhood trauma: the Early Trauma Inventory. Depress Anxiety 12, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Vythilingam M, Vermetten E, Adil J, Khan S, Nazeer A, Afzal N, McGlashan T, Elzinga B, Anderson GM, Heninger G, Southwick SM, Charney DS, 2003. Cortisol response to a cognitive stress challenge in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) related to childhood abuse. Psychoneuroendocrinology 28, 733–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DW, Anda RF, Tiemeier H, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Croft JB, Giles WH, 2009. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. Am J Prev Med 37, 389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce SE, Buchholz KR, Brown WJ, Yan L, Durbin A, Sheline YL, 2013. Altered emotional interference processing in the amygdala and insula in women with post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuroimage Clin 2, 43–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brydges NM, Moon A, Rule L, Watkin H, Thomas KL, Hall J, 2018. Sex specific effects of pre-pubertal stress on hippocampal neurogenesis and behaviour. Transl Psychiatry 8, 271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HD, 2005. Neural mechanisms of autonomic, affective, and cognitive integration. J Comp Neurol 493, 154–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HD, Corfield DR, Chandler MP, Mathias CJ, Dolan RJ, 2000. Cerebral correlates of autonomic cardiovascular arousal: a functional neuroimaging investigation in humans. J Physiol 523 Pt 1, 259–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, McEwen BS, 2012. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol Behav 106, 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson KW, 2008. Emotional predictors and behavioral triggers of acute coronary syndrome. Cleve Clin J Med 75 Suppl 2, S15–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Giles WH, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Williams JE, Chapman DP, Anda RF, 2004a. Insights into causal pathways for ischemic heart disease: adverse childhood experiences study. Circulation 110, 1761–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong MX, Giles WH, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Williams JE, Chapman DP, Anda RF, 2004b. Insights into causal pathways for ischemic heart disease - Adverse childhood experiences study. Circulation 110, 1761–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan NW, Hayes DJ, Wiebking C, Tiret B, Pietruska K, Chen DQ, Rainville P, Marjanska M, Ayad O, Doyon J, Hodaie M, Northoff G, 2015. Negative childhood experiences alter a prefrontal-insular-motor cortical network in healthy adults: A preliminary multimodal rsfMRI-fMRI-MRS-dMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 36, 4622–4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elton A, Tripathi SP, Mletzko T, Young J, Cisler JM, James GA, Kilts CD, 2014. Childhood Maltreatment is Associated with a Sex-Dependent Functional Reorganization of a Brain Inhibitory Control Network. Hum Brain Mapp 35, 1654–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elzinga BM, Schmahl CS, Vermetten E, van Dyck R, Bremner JD, 2003. Higher cortisol levels following exposure to traumatic reminders in abuse-related PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology 28, 1656–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson J, Vogel EK, Lansner A, Bergstrom F, Nyberg L, 2015. Neurocognitive Architecture of Working Memory. Neuron 88, 33–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, Marks JS, 1998. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 14, 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, 2004. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II), In: Segal MJHDL (Ed.), Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment John Wiley & Sons Inc., Hoboken, NJ, US, pp. 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Gasquoine PG, 2014. Contributions of the insula to cognition and emotion. Neuropsychol Rev 24, 77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gläscher J, Gitelman D, 2008. Contrast weights in flexible factorial design with multiple groups of subjects. SPM@ JISCMAIL. AC. UK) Sml, editor, 1–12.

- Goodwin RD, Stein MB, 2004. Association between childhood trauma and physical disorders among adults in the United States. Psychological Medicine 34, 509–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MA, Rylander K, Harrison NA, Wallin BG, Critchley HD, 2009. Following one’s heart: cardiac rhythms gate central initiation of sympathetic reflexes. J Neurosci 29, 1817–1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar M, Quevedo K, 2007. The neurobiology of stress and development. Annu Rev Psychol 58, 145–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammadah M, Al Mheid I, Wilmot K, Ramadan R, Shah AJ, Sun Y, Pearce B, Garcia EV, Kutner M, Bremner JD, Esteves F, Raggi P, Sheps DS, Vaccarino V, Quyyumi AA, 2017a. The Mental Stress Ischemia Prognosis Study: Objectives, Study Design, and Prevalence of Inducible Ischemia. Psychosom Med 79, 311–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammadah M, Alkhoder A, Al Mheid I, Wilmot K, Isakadze N, Abdulhadi N, Chou D, Obideen M, O’Neal WT, Sullivan S, Samman Tahhan A, Kelli HM, Ramadan R, Pimple P, Sandesara P, Shah AJ, Ward L, Ko Y-A, Sun Y, Uphoff I, Pearce B, Garcia EV, Kutner M, Bremner JD, Esteves F, Sheps DS, Raggi P, Vaccarino V, Quyyumi AA, 2017b. Hemodynamic, catecholamine, vasomotor and vascular responses: Determinants of myocardial ischemia during mental stress. International Journal of Cardiology 243, 47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Newport DJ, Heit S, Graham YP, Wilcox M, Bonsall R, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB, 2000. Pituitary-adrenal and autonomic responses to stress in women after sexual and physical abuse in childhood. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association 284, 592–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmakis KA, Meyer JS, Chiodo L, Leung K, 2015. Adverse childhood experiences and chronic hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity. Stress 18, 446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai K, Yamasue H, Gilbertson MW, Shenton ME, Rauch SL, Pitman RK, 2008. Evidence for acquired pregenual anterior cingulate gray matter loss from a twin study of combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 63, 550–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama N, Brummer M, Hertz L, Quinn S, Kim Y, Bremner JD, 2007. Morphologic alterations in the corpus callosum in abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder: a preliminary study. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis 195, 1027–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama N, Quinn S, Bremner JD, 2006. Smaller volume of anterior cingulate cortex in abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Affect. Disord 90, 171–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkeila J, Vahtera J, Korkeila K, Kivimäki M, Sumanen M, Koskenvuo K, Koskenvuo M, 2010. Childhood adversities as predictors of incident coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular disease. Heart 96, 298–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koziol LF, Budding D, Andreasen N, D’Arrigo S, Bulgheroni S, Imamizu H, Ito M, Manto M, Marvel C, Parker K, Pezzulo G, Ramnani N, Riva D, Schmahmann J, Vandervert L, Yamazaki T, 2014. Consensus paper: the cerebellum’s role in movement and cognition. Cerebellum 13, 151–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraynak TE, Marsland AL, Gianaros PJ, 2018. Neural Mechanisms Linking Emotion with Cardiovascular Disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 20, 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane RD, Reiman EM, Ahern GL, Schwartz GE, Davidson RJ, 1997. Neuroanatomical correlates of happiness, sadness, and disgust. Am J Psychiatry 154, 926–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiner HC, Leiner AL, Dow RS, 1989. Reappraising the cerebellum: what does the hindbrain contribute to the forebrain? Behav Neurosci 103, 998–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR, Heim C, 2009. Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci 10, 434–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marien P, Ackermann H, Adamaszek M, Barwood CH, Beaton A, Desmond J, De Witte E, Fawcett AJ, Hertrich I, Kuper M, Leggio M, Marvel C, Molinari M, Murdoch BE, Nicolson RI, Schmahmann JD, Stoodley CJ, Thurling M, Timmann D, Wouters E, Ziegler W, 2014. Consensus paper: Language and the cerebellum: an ongoing enigma. Cerebellum 13, 386–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marusak HA, Etkin A, Thomason ME, 2015. Disrupted insula-based neural circuit organization and conflict interference in trauma-exposed youth. NeuroImage : Clinical 8, 516–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostofsky E, Penner EA, Mittleman MA, 2014. Outbursts of anger as a trigger of acute cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Heart Journal 35, 1404–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers B, 2017. Corticolimbic regulation of cardiovascular responses to stress. Physiol Behav 172, 49–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai M, Hoshide S, Kario K, 2010. The insular cortex and cardiovascular system: a new insight into the brain-heart axis. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens 4, 174–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negron-Oyarzo I, Aboitiz F, Fuentealba P, 2016. Impaired Functional Connectivity in the Prefrontal Cortex: A Mechanism for Chronic Stress-Induced Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Neural Plasticity [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nicholson AA, Sapru I, Densmore M, Frewen PA, Neufeld RWJ, Théberge J, McKinnon MC, Lanius RA, 2016. Unique insula subregion resting-state functional connectivity with amygdala complexes in posttraumatic stress disorder and its dissociative subtype. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging 250, 61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer S, Cechetto D, 2016. The Insular Cortex and the Regulation of Cardiac Function. Compr Physiol 6, 1081–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otte C, Neylan TC, Pole N, Metzler T, Best S, Henn-Haase C, Yehuda R, Marmar CR, 2005. Association between childhood trauma and catecholamine response to psychological stress in police academy recruits. Biological Psychiatry 57, 27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus MP, Stein MB, 2006. An insular view of anxiety. Biol Psychiatry 60, 383–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters SK, Dunlop K, Downar J, 2016. Cortico-Striatal-Thalamic Loop Circuits of the Salience Network: A Central Pathway in Psychiatric Disease and Treatment. Front Syst Neurosci 10, 104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkus AJ, Lenze EJ, Butters MA, Twamley EW, Wetherell JL, 2018. Childhood Trauma Is Associated With Poorer Cognitive Performance in Older Adults. J Clin Psychiatry 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan R, Sheps D, Esteves F, Zafari AM, Bremner JD, Vaccarino V, Quyyumi AA, 2013. Myocardial ischemia during mental stress: role of coronary artery disease burden and vasomotion. JAHA 2, e000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiman EM, Lane RD, Ahern GL, Schwartz GE, Davidson RJ, Friston KJ, Yun LS, Chen K, 1997. Neuroanatomical correlates of externally and internally generated human emotion. Am J Psychiatry 154, 918–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich-Edwards JW, Mason S, Rexrode K, Spiegelman D, Hibert E, Kawachi I, Jun HJ, Wright RJ, 2012. Physical and sexual abuse in childhood as predictors of early-onset cardiovascular events in women. Circulation 126, 920–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugulies R, 2002. Depression as a predictor for coronary heart disease - A review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 23, 51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruit KG, Neafsey EJ, 1988. Cardiovascular and respiratory responses to electrical and chemical stimulation of the hippocampus in anesthetized and awake rats. Brain Res 457, 310–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh A, Potter GG, McQuoid DR, Boyd B, Turner R, MacFall JR, Taylor WD, 2017. Effects of early life stress on depression, cognitive performance and brain morphology. Psychol Med 47, 171–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmand M, Wienhard K, Casey M, Eriksson L, Jones W, Reed J, Treffert J, Lenox M, Luk P, Bao J, 1999. Performance evaluation of a new LSO high resolution research tomograph-HRRT, Nuclear Science Symposium, 1999. Conference Record. 1999 IEEE. IEEE, pp. 1067–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Shah A, Chen C, Campanella C, Kasher N, Evans S, Reiff C, Mishra S, Hammadah M, Lima BB, Wilmot K, Al Mheid I, Alkhoder A, Isakadze N, Levantsevych O, Pimple PM, Garcia EV, Wittbrodt M, Nye J, Ward L, Lewis TT, Kutner M, Raggi P, Quyyumi A, Vaccarino V, Bremner JD, 2018. Brain correlates of stress-induced peripheral vasoconstriction in patients with cardiovascular disease. Psychophysiology, e13291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sheps DS, McMahon RP, Becker L, Carney RM, Freedlan KE, Cohen JD, Sheffield D, Goldberg AD, Ketterer MW, Pepine CJ, Raczynski JM, Light K, Krantz DS, Stone PH, Knatterud GL, Kaufmann PG, 2002. Mental stress-induced ischemia and all-cause mortality in patients with coronary artery disease: Results from the Psychophysiological Investigations of Myocardial Ischemia Study. Circulation 105, 1780–1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specchia G, Deservi S, Falcone C, Gavazzi A, Angoli L, Bramucci E, Ardissino D, Mussini A, 1984. Mental Arithmetic Stress-Testing in Patients with Coronary-Artery Disease. American Heart Journal 108, 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoodley CJ, Schmahmann JD, 2009. Functional topography in the human cerebellum: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Neuroimage 44, 489–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strike PC, Steptoe A, 2005. Behavioral and emotional triggers of acute coronary syndromes: a systematic review and critique. Psychosom Med 67, 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suglia SF, Koenen KC, Boynton-Jarrett R, Chan PS, Clark CJ, Danese A, Faith MS, Goldstein BI, Hayman LL, Isasi CR, Pratt CA, Slopen N, Sumner JA, Turer A, Turer CB, Zachariah JP, American Heart Association Council on, E., Prevention, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the, Y., Council on Functional, G., Translational, B., Council on, C., Stroke, N., Council on Quality of, C., Outcomes, R., 2018. Childhood and Adolescent Adversity and Cardiometabolic Outcomes: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 137, e15–e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan S, Hammadah M, Al Mheid I, Wilmot K, Ramadan R, Alkhoder A, Isakadze N, Shah A, Levantsevych O, Pimple PM, Kutner M, Ward L, Garcia EV, Nye J, Mehta PK, Lewis TT, Bremner JD, Raggi P, Quyyumi AA, Vaccarino V, 2018. Sex differences in hemodynamic and microvascular mechanisms of myocardial ischemia induced by mental stress. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 38, 473–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P, 1988. Co-planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain: 3-dimensional proportional system: an approach to cerebral imaging

- Teicher MH, Anderson CM, Ohashi K, Polcari A, 2014. Childhood maltreatment: Altered network centrality of cingulate, precuneus, temporal pole and insula. Biol. Psychiatry 76, 297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, Anderson CM, Polcari A, 2012. Childhood maltreatment is associated with reduced volume in the hippocampal subfields CA3, dentate gyrus, and subiculum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, E563–E572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, Dumont NL, Ito Y, Vaituzis C, Giedd JN, Andersen SL, 2004. Childhood neglect is associated with reduced corpus callosum area. Biol Psychiatry 56, 80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer JF, Lane RD, 2009. Claude Bernard and the heart-brain connection: further elaboration of a model of neurovisceral integration. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 33, 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JH, Neylan TC, Schiller NB, Li Y, Cohen BE, 2013. Objective evidence of myocardial ischemia in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 74, 861–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twardosz S, Lutzker JR, 2010. Child maltreatment and the developing brain: A review of neuroscience perspectives. Aggression and Violent Behavior 15, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Vaccarino V, Bremner JD, 2013a. Traumatic stress is heartbreaking. Biol Psychiatry 74, 790–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccarino V, Bremner JD, 2013b. Traumatic stress is heartbreaking. Biol. Psychiatry 74, 790–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccarino V, Bremner JD, 2017. Behavioral, emotional and neurobiological determinants of coronary heart disease risk in women. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 74, 297–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccarino V, Goldberg J, Rooks C, Shah AJ, Veledar E, Faber TL, Votaw JR, Forsberg CW, Bremner JD, 2013. Post-traumatic stress disorder and incidence of coronary heart disease: a twin study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 62, 97–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccarino V, Sullivan S, Hammadah M, Wilmot K, Al Mheid I, Ramadan R, Elon L, Pimple PM, Garcia EV, Nye J, Shah AJ, Alkhoder A, Levantsevych O, Gay H, Obideen M, Huang M, Lewis TT, Bremner JD, Quyyumi AA, Raggi P, 2018. Mental stress-induced-myocardial ischemia in young patients with recent myocardial infarction: Sex differences and mechanisms. Circulation 137, 794–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccarino V, Votaw J, Faber T, Veledar E, Murrah NV, Jones LR, Zhao J, Su S, Goldberg J, Raggi JP, Quyyumi AA, Sheps DS, Bremner JD, 2009. Major depression and coronary flow reserve detected by positron emission tomography. Archives of Internal Medicine 169, 1668–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccarino V, Wilmot K, Al Mheid I, Ramadan R, Pimple P, Shah AJ, Garcia EV, Nye J, Ward L, Hammadah M, Kutner M, Long Q, Bremner JD, Esteves F, Raggi P, Quyyumi AA, 2016. Sex differences in mental stress-Induced myocardial ischemia in patients with coronary heart disease. JAHA 5, pii: e003630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber DA, Reynolds CR, 2004. Clinical perspectives on neurobiological effects of psychological trauma. Neuropsychol Rev 14, 115–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J, Rooks C, Ramadan R, Shah AJ, Bremner JD, Quyyumi AA, Kutner M, Vaccarino V, 2014. Meta-analysis of mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia and subsequent cardiac events in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 114, 187–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulsin LR, Singal BM, 2003. Do depressive symptoms increase the risk for the onset of coronary disease? A systematic quantitative review. Psychosomatic Medicine 65, 201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R, 2002. Post-traumatic stress disorder. New England Journal of Medicine 346, 108–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R, 2006. Advances in understanding neuroendocrine alterations in PTSD and their therapeutic implications. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1071, 137–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Bremner JD, Goldberg J, Quyyumi AA, Vaccarino V, 2013a. MAOA genotype, childhood trauma and subclinical atherosclerosis: a twin study. Psychosomatic medicine 75, 471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Bremner JD, Goldberg J, Quyyumi AA, Vaccarino V, 2013b. Monoamine oxidase a genotype, childhood trauma, and subclinical atherosclerosis: a twin study. Psychosom. Med 75, 471–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.