Abstract

Background

Pericytes are members of the tumor stroma; however, little is known about their origin, function, or interaction with other tumor components. Emerging evidence suggest that pericytes may regulate leukocyte transmigration. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) are immature myeloid cells with powerful inhibitory effects on T-cell–mediated antitumor reactivity.

Methods

We generated subcutaneous tumors in a genetic mouse model of pericyte deficiency (the pdgfbret/ret mouse) and littermate control mice (n = 6–25). Gene expression profiles from 253 breast cancer patients (stage I-III) were evaluated for clinic-pathological parameters and survival using Cox proportional hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) based on a two-sided Wald test.

Results

We report that pericyte deficiency leads to increased transmigration of Gr1+/CD11b+ cells in experimentally induced tumors. Pericyte deficiency produced defective tumor vasculature, resulting in a more hypoxic microenvironment promoting IL-6 upregulation in the malignant cells. Silencing IL-6 expression in tumor cells attenuated the observed differences in MDSC transmigration. Restoring the pericyte coverage in tumors abrogated the increased MDSC trafficking to pericyte-deficient tumors. MDSC accumulation in tumors led to increases in tumor growth and in circulating malignant cells. Finally, gene expression analysis from human breast cancer patients revealed increased expression of the human MDSC markers CD33 and S100A9 with concomitant decreased expression of pericyte genes and was associated with poor prognosis (HR = 1.88, 95% CI = 1.08 to 3.25, P = .03).

Conclusions

Our data uncovers a novel paracrine interaction between tumor pericytes and inflammatory cells and delineates the cellular events resulting in the recruitment of MDSC to tumors. Furthermore, we propose for the first time a role for tumor pericytes in modulating the expression of immune mediators in malignant cells by promoting a hypoxic microenvironment.

Pericytes represent a fundamental component of the tumor stroma (1), but in contrast to other stromal cell types such as cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) (2) or inflammatory cells (3), little is known about their recruitment, identification, and interaction with neoplastic or stromal cells. Recent findings have proposed a role for pericytes in regulating leukocyte trafficking (4), with tumors developed in mice deficient for the pericyte-specific gene rgs5 (5) showing increased infiltration of CD8+/CD4+ T-cells, albeit only after adoptive transfer (6). Furthermore, constitutive activation of the main receptor for pericyte recruitment, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGFR)-β (7), results in upregulation of immune response genes in pericytes (8).

As both innate and acquired immune cells coexist in tumors, leukocytes constitute a large fraction of the stroma. Despite a strong correlation between Cytotoxic T-cell accumulation and better clinical outcome (9), tumors are still able to escape immune surveillance through different mechanisms, of which the recruitment of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) is pivotal (10). MDSCs comprise a heterogeneous collection of immature myeloid cells that efficiently inhibit T-cell-mediated antitumor reactivity (10). The expansion of MDSC population in tumors is a consequence of increased expression of certain cytokines (11); amongst these, elevated levels of IL-6 correlate with MDSC enhancement (12–15). Yet, while many studies have attempted to unravel the mechanisms by which MDSCs influence tumor biology, the cellular and molecular events leading to cytokine expression and subsequent MDSC accumulation in tumors are largely unknown.

We hypothesized that pericyte coverage of tumor blood vessels regulates leukocyte trafficking. In order to test this, we took advantage of, firstly, a genetic model for pericyte deficiency (the pdgfbret/ret mouse) (16), generating subcutaneous B16 melanomas and Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) in pericyte-deficient mice and littermate controls, and, secondly, gene expression data from a cohort of breast cancer patients. We report that poorer pericyte coverage results in elevated MDSC numbers in tumors. Our findings suggest for the first time that pericyte coverage of the tumor vasculature is a critical factor controlling tumor immunogenicity. Further, we describe a novel paracrine interaction between pericytes and inflammatory cells, thus expanding our understanding of the cellular events that result in the recruitment of MDSCs to tumors.

Methods

Mouse Experiments

Tumors and tissues were studied in transgenic mice lacking the PDGF-B retention motif (pdgfbret/ret), backcrossed at least seven generations against C57Bl/6-J and identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) genotyping (17). Tumor cells (1-2x106) were inoculated subcutaneously in the dorsal flank of eight- to 12-week old control and pdgfbret/ret mice. Both male and female mice were used for this study. Mice were killed two or three weeks after cell inoculation. All procedures were carried out in accordance with institutional policies following approval from the Animal Ethical Board of Northern Stockholm.

Flow Cytometry

Tumors and tissues from naïve and tumor-bearing mice were collected under isoflurane anesthesia, finely minced, and digested by 5 mg/mL of collagenase-A (Roche, Manheim, Germany) and 1 mg/mL of dispase (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ) in HBSS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 150 mg/mL glucose (Sigma Aldrich) for one hour at 37°C. The dispersed tissues were filtered using a 100 μm nylon mesh (BD, San Jose, CA), and erythrocytes were depleted (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Heparinized blood and bone marrow from femurs were harvested for single cell preparation and erythrocytes lysed as mentioned above. Cell fractions from tumors, tissues, and blood were pre-incubated with anti-CD16/32 antibody (1:100; dilution factor, FcγR-binding inhibitor, eBioscience) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Life Technologies) and subsequently immunostained with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies against cell surface antigens (Gr1, CD45, and CD18: BD Biosciences, Ly6G, Ly6C, and CD11b: eBioscience) or matched isotype controls, diluted 1:50 in PBS. Cells were then washed in PBS and resuspended in stabilizing fixative (BD Biosciences).

For FACS analysis of circulating tumor cells, erythrocyte-depleted blood samples were obtained from GFP+ tumor-bearing mice (three weeks’ incubation). Data were acquired using FACSORT flow cytometer or FACSCanto III (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with Flowjo software (version 7.6.4, Treestar, Ashland, OR).

Human Gene Expression Analysis

Patients and Specimens

Our study population consisted of the Uppsala breast cancer cohort (253 patients), previously described in detail (18,19). The ethics committee at Karolinska Institute approved the gene expression study (Stockholm, Sweden), and written consent was obtained from each patient for the use of the biological tissues. The distribution of tumor stage at diagnosis was as follows: Stage 1, 41.0%; Stage 2, 24.6%; Stage 3, 34.4%; and mean age at diagnosis was 62.13 years (range = 28–93 years). Raw data files are publically available (NCBI Geo GSE3494).

Gene Set Annotation and Unsupervised Clustering

Probe annotations for U133A and B chips were updated with versions 2.14.0 of the hgu133a.db and 2.14.0 of hgu133b.db packages from the Bioconductor website (www.bioconductor.org). In cases of numerous probes for one gene, an average expression over all probes was taken. For heatmaps, an unsupervised clustering was performed using the hclust function in R version 2.15.1, and heatmaps were produced using the heatmap.2 function of the gplots package. The three cluster groups formed in the data were subsequently related to clinico-pathological parameters as outlined in the statistics section below.

PAM50 Gene Expression Signature

Relevant genes for the PAM50 signature were taken from Perou et al. (20). Signature genes were extracted from the Uppsala A and B expression array sets and mean centered before passing the resulting object to the PAM50 function code as previously described (20), resulting in the classification of tumors into the molecular subtypes (Luminal A, B, human epidermal growth factor 2 [HER2]–enriched, basal-like, and normal-like) based on a nearest centroid predictor.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD. For two group comparisons, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test was performed (Prism v5.01, GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). For human gene expression analysis, two-sided Fischer’s exact test and Kruskal-Wallis tests were employed to determine statistical associations between pericyte/MDSC cluster groups and clinico-pathological/molecular parameters. P values were not adjusted for multiple testing. Survival analysis was carried out using the “survival” (version 2.37–7) and “survplot” packages (version 0.0.7, R-programming environment). Hazard ratios confidence intervals and two-sided Wald P values were calculated using a Cox proportional hazard model (specifically with the “coxph” function in R, proportionality was verified by visualization), and differences between survival groups were calculated and visualized by Kaplan-Meier analysis. P values of .05 or less were considered statistically significant.

Results

Evaluation of Gr1+ /CD11b+ Cells in Pericyte-Deficient Tumors

Different reports have established the degree of pericyte loss in the pdgfbret/ret mouse in a variety of tissues and tumors (16,17,21,22). Here, we show that B16 and LLC tumors grown in pdgfbret/ret mice have decreased NG2 immunoreactivity relative to controls (Supplementary Figure 1, A and B, available online), which was also observed in healthy lungs and skin (Supplementary Figure 1C, available online, and data not shown).

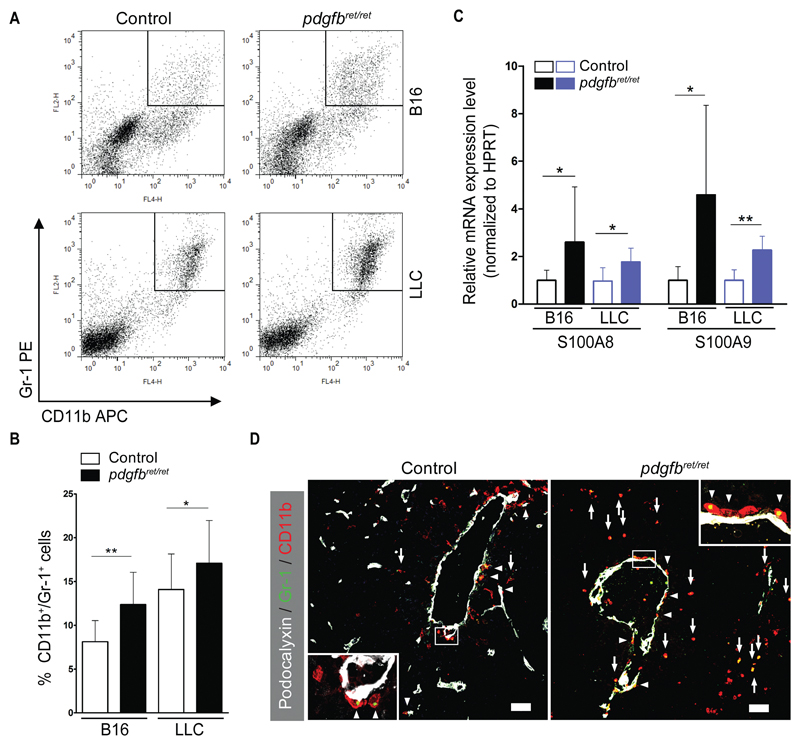

Using flow cytometry, we readily detected Gr1+/CD11b+ cells in experimental malignancies; however, these cells predominantly accumulated in the pericyte-deficient tumors (B16, control 8.1% ±2.4; pdgfbret/ret 12.4% ±3.7; P = .003; LLC, control 14.1% ±4.1; pdgfbret/ret 17.1% ±4.9; P = .04) (Figure 1, A and B). An elevated Gr1+/CD11b+ population was observed in pdgfbret/ret tumors harvested after equal incubation time or from equal-sized tumors (Supplementary Figure 1F, available online). Immunostaining verified the presence of the double-positive cells (Figure 1D). Flow cytometry of CD45+ cells failed to detect differences in total leukocyte infiltration (Supplementary Figure 1, D and E, available online).

Figure 1.

FACS analysis of CD11b+/Gr1+ cells in tumors. B16 melanoma and Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) cells were injected s.c. in pdgfbret/ret and control mice. Tumors were resected after two weeks, and flow cytometry was performed to detect CD11b+/Gr1+ cells. Tumors were also processed for immunohistochemistry and mRNA extraction. A) Representative dot plots showing the gating of CD11b+/Gr1+ cells. All plotted cells were gated based on appropriate isotype controls. B) Quantification of CD11b+/Gr1+ cells (n = 10 to 15 in each group) as percentage of total viable cells (B16, control 8.1% ±2.4; pdgfbret/ret 12.4% ±3.7, P = .003; LLC, control 14.1% ±4.1; pdgfbret/ret 17.1% ±4.9, P = .04). C) Expression of S100A8 and S100A9 mRNA as analyzed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (n = 10 in each group). D) Confocal images of B16 tumors that were triple stained for Podocalyxin (white), CD11b (red,) and Gr1 (green). Arrows indicate CD11b+/Gr1+ cells at tumor sites, and arrowheads mark CD11b+/Gr1+ cells near tumor vessels. The images are representative of five to 10 fields from two to three cryosections (n = 6 mice from each genotype). Objective lens, 20x (dry) and 40x (oil immersion). Scale bar = 50 μm. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *P < .05, **P < .01, by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. LLC = Lewis Lung Carcinoma; MDSC = myeloid-derived suppressor cells; PDGF-B = platelet-derived growth factor B retention motif knockout mice (pericyte deficient mice, pdgfbret/ret).

In mice, Gr1+/CD11b+ cells have been described as immature cells of the myeloid lineage, or MDSC (10). We studied additional MDSC markers such as S100a8, S100a9 (23), and Arginase-1 (24). The pericyte-deficient tumors expressed statistically significantly more s100a8 (B16, control 1 ± 0.4; pdgfbret/ret 2.6 ± 2.3; P = .04; LLC, control 1.0 ± 0.7; pdgfbret/ret 1.8 ± 0.6; P = .01) and S100a9 (B16, control 1.0 ± 0.6; pdgfbret/ret 4.5 ± 3.8; P = .04; LLC, control 1 ± 0.4; pdgfbret/ret 2.3 ± 0.6; P = .01) mRNA as measured by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) when compared with controls (Figure 1C). Furthermore, we detected an increase of Arginase-1+ cells (Supplementary Figure 2A, available online) and elevated Arginase-1 protein activity (Supplementary Figure 2B, available online).

MDSCs in mice can have either granulocytic (Ly6G+) or monocytic phenotype (Ly6C+) (10). We examined whether pericyte deficiency altered these two subpopulations in tumors. Granulocytic, CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6Clow cells were predominant in the blood of tumor-bearing mice (Supplementary Figure 2, C and D, available online). Melanomas harbored a majority of monocytic MDSCs (CD11b+Ly6G-Ly6C+ cells) (25), whereas in LLC the granulocytic subset was prevalent (Supplementary Figure 2, E and F, available online); however, no differences were found between different genotypes.

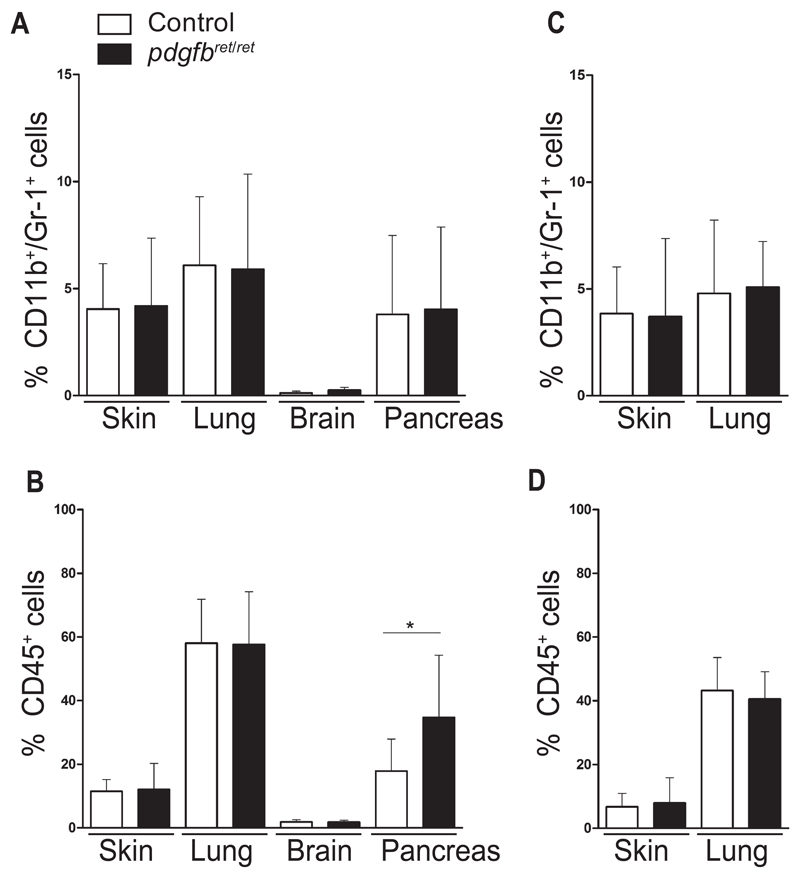

The pdgfbret/ret mouse bears a systemic reduction of pericytes (17). We postulated that pericyte deficiency is sufficient to cause Gr1+/CD11b+ accumulation in healthy tissues. Skin, lung, brain, and pancreas from naïve pdgfbret/ret and control mice showed no differences in the amount of Gr1+/CD11b+ cells (Figure 2A; Supplementary Figure 3A, available online). We also failed to detect differences in the CD45+ population (Figure 2B; Supplementary Figure 3B, available online), except in the pancreas of pericyte-deficient mice (control 17.8 ± 10; pdgfbret/ret 34.7 ± 19.6; P = .02) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Analysis of CD11b+/Gr1+ cells in healthy tissues. Brain, skin, liver, and pancreas from naïve control and pdgfbret/ret mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for detection of CD11b+/Gr1+ cells. A) Quantification of CD11b+/Gr1+ cells in the different tissues. B) Quantification of total leukocytes as measured by CD45+ cells. Skin and lungs from tumor-bearing mice were analyzed by flow cytometry. C) Quantification of CD11b+/Gr1+ cells in skin and lungs from tumor-bearing mice. D) Quantification of total leukocytes as measured by CD45+ cells in skin and lungs from tumor-bearing mice. n = 7 mice from both genotypes for brain, skin, and lung analyses, and n = 10 mice for pancreas. All quantifications are based on gating using appropriate isotype controls. Data are presented as mean ± SD, *P < .05, by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test.

Examination of healthy lungs and skin from tumor-bearing mice did not reveal differences in the double-positive cell population (Figure 2C; Supplementary Figure 4A, available online) or in the total leukocyte pool (Figure 2D; Supplementary Figure 4B, available online). We conclude that pericyte deficiency per se is not sufficient to cause an increase of the Gr1+/CD11b+ population.

Identifying the MDSC-Recruiting Cytokine Upon Pericyte Deficiency

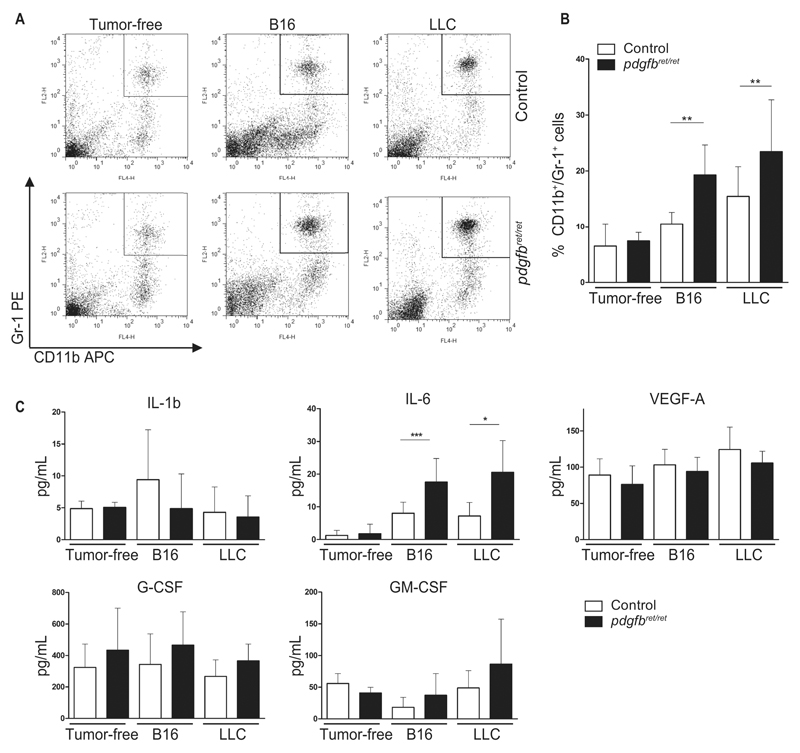

Previous studies have reported the expansion of Gr1+/CD11b+ cells in blood, spleen, and bone marrow in preclinical tumor models (26). Indeed, tumor-bearing mice had increased Gr1+/CD11b+ frequency in all these tissues (Figure 3, A and B; Supplementary Figure 4, C-E, available online). Further analysis between genotypes of the double-positive population revealed no differences in spleen and bone marrow (Supplementary Figure 6, B and D, available online) but a statistically significant increase in the blood of tumor-bearing pdgfbret/ret (B16: P = .001; LLC: P = .006) (Figure 3, A and B).

Figure 3.

Blood analyses of CD11b+/Gr1+ cells and serum analyses of cytokines. Blood and serum were collected from naïve and tumor-bearing pdgfbret/ret and control mice. A) Representative dot plots and (B) quantification of CD11b+/Gr1+ cells in blood of naïve, B16, and Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) tumor–bearing mice. For each genotype: n = 7 (naïve mice), n = 10 (B16 tumor–bearing mice), and n = 12 (LLC tumor–bearing mice). C) Serum ELISA analysis for IL-1b, IL-6, G-CSF, GM-CSF, and VEGF-A from tumor-free, B16, and LLC tumor–bearing mice, evaluated from n = 13 (naïve mice), and n = 10 to 20 (tumor-bearing mice). Data are presented as mean ± SD, *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. G-CSF = granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; GM-CSF = granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor; IL-1b = interleukin 1b; IL-6 = interleukin 6; LLC = Lewis Lung Carcinoma; VEGF-A = vascular endothelial growth factor A.

We examined the mRNA expression of S100A8 and S100A9 from the axillary and cervical tumor-draining lymph nodes and observed a trend towards increased levels of both mRNAs in pericyte-deficient mice relative to controls (Supplementary Figure 4F, available online).

To identify the factor contributing to the generation of Gr1+/CD11b+ cells (10), we measured the serum concentration of the cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, G-CSF, GM-CSF, and VEGF-A (Figure 3C). Only IL-6 was statistically significantly increased in tumor-bearing pdgfbret/ret mice, in both B16 (P < .001) and LLC (P = .01) (Figure 3C). Thus, pericyte deficiency in tumors causes elevated serum IL-6 levels.

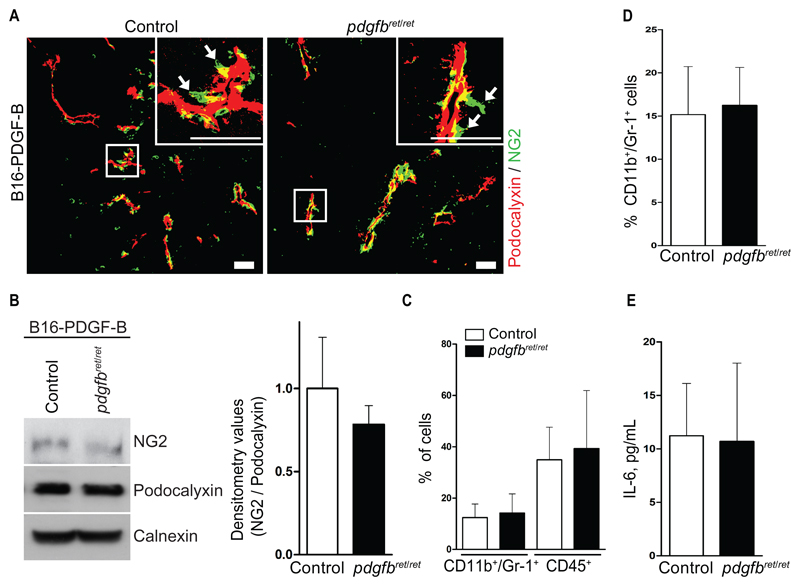

Rescue of Pericyte Coverage in Tumor Blood Vessels

PDGFB overexpression by T241 cells has been shown to restore pericyte coverage specifically in tumor vessels of pdgfbret/ret mice (22). We took advantage of B16 cells overexpressing PDGF-B (27) (B16-PDGF-B), and thus revert the pericyte-depleted phenotype in the tumors of pdgfbret/ret mice. Pericyte coverage in both pdgfbret/ret and control B16-PDGF-B tumors appeared similar by immunostaining with comparable NG2 expression as revealed by immunoblotting (Figure 4, A and B), indicating that our rescue strategy was successful.

Figure 4.

Analysis of myeloid-derived suppressor cell levels in pericyte-rescued tumors. Pericyte coverage of tumor blood vessels was rescued by overexpressing PDGFB from B16 melanoma tumor cells. B16-PDGF-B cells were inoculated s.c. into pdgfbret/ret and control mice. Tumors, blood, and serum were collected and processed for immunostaining, protein extraction, and flow cytometry. A) Confocal images showing immunostaining of endothelial cells by podocalyxin (red) and pericytes by NG2 (green) from B16-PDGF-B control and pdgfbret/ret tumors. The images are representative of five fields from n = 5 mice for each genotype. Arrows indicate detached pericytes. Objective lens, 20x (dry) and 40x (oil immersion). Scale bar = 50 μm. B) Western blot and quantification by densitometry for NG2 and podocalyxin from B16-PDGF-B tumors. Images are representative of two independent experiments. C) Flow cytometry quantification of CD11b+/Gr1+ cells and total leukocytes as CD45+ cells from B16-PDGF-B tumors. D) Flow cytometry quantification of CD11b+/Gr1+ cells in blood of B16-PDGF-B tumor–bearing mice (n = 9 mice). E) IL-6 serum concentration from B16-PDGF-B tumor–bearing mice (n = 5 to 10 mice). Data are presented as mean ± SD by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. NG2 = chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 2.

We did not observe differences in the frequency of MDSC in both pdgfbret/ret and control B16-PDGF-B tumors (Figure 4C; Supplementary Figure 5A, available online), or in tumor-infiltrating CD45+ cells (Figure 4C; Supplementary Figure 5A, available online), in Gr1+/CD11b+ cells in blood (Figure 4D; Supplementary Figure 5B, available online), or in serum IL-6 (Figure 4E).

In summary, the degree of pericyte coverage of vessels dictates the frequency of MDSC in tumors.

IL-6 Silencing in Malignant Cells

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis revealed a two-fold increase in IL-6 mRNA in pdgfbret/ret melanomas over controls (control 1 ± 0.8; pdgfbret/ret 2.1 ± 1.3; P = .02) (Figure 5A), with no differences in IL-6 mRNA expression from tumor-isolated CD45+ cells (Figure 5B). We decided to silence IL-6 expression in tumor cells by lentiviral infection of shRNA against IL-6 (termed LLC-IL6KD and B16-IL6KD). B16-IL6KD cells grew at the same rate (Supplementary Figure 6A, available online), with a decrease in IL-6 mRNA of approximately five-fold (P = .001) as compared with control-infected cells (Supplementary Figure 6B, available online).

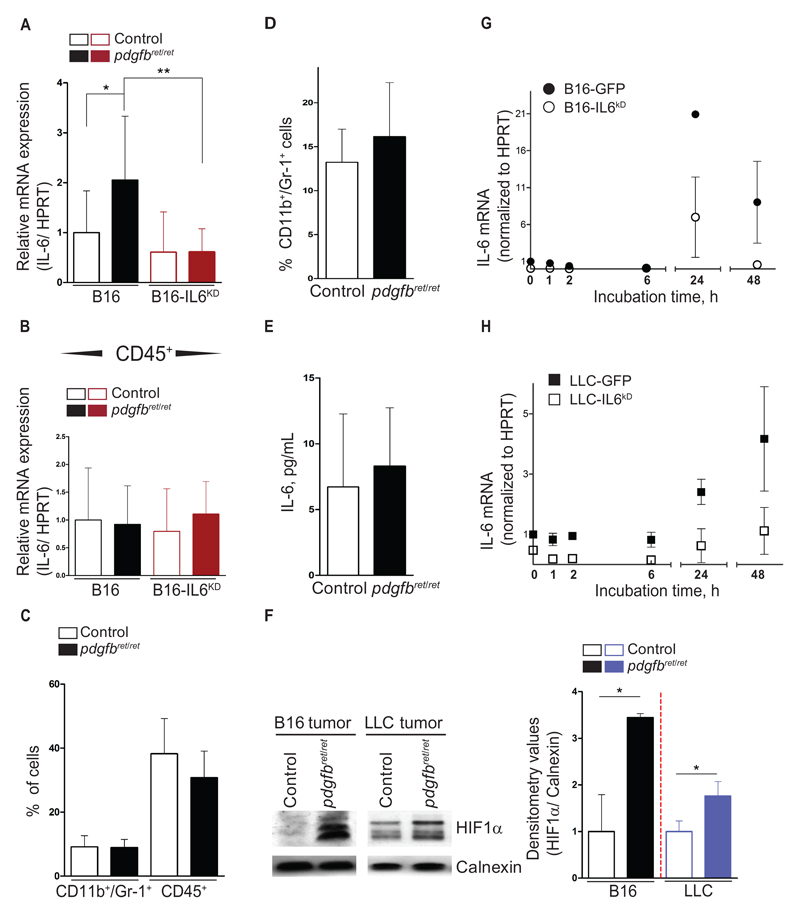

Figure 5.

FACS analysis of myeloid-derived suppressor cells from B16-IL6KD tumors and origin of IL-6 upregulation. Silencing of IL-6 expression in the malignant cells was achieved by lentiviral infection carrying relevant shRNAs against IL-6. IL-6–silenced cell lines (B16-IL6KD and Lewis Lung Carcinoma [LLC]–IL6KD) were then inoculated s.c. into pdgfbret/ret and control mice. Tumors, blood, and serum were collected and processed for immunostaining, protein extraction, and flow cytometry (A). IL-6 mRNA quantification in whole tumor extracts of B16 and B16-IL6KD cell engraftments as measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) (n = 13 from B16 tumors, n = 6 to 8 for B16 IL6KD tumors). B) IL-6 mRNA quantification from isolated tumor-infiltrating CD45+ cells from B16 and B16-IL6KD tumors (n = 4 to 10). C) Flow cytometry quantification of CD11b+/Gr1+ cells and total leukocytes as CD45+ cells from B16-IL6KD tumors. D) Flow cytometry quantification of CD11b+/Gr1+ cells in the blood of B16-IL6KD tumor–bearing mice (n = 10 for all flow cytometry experiments). E) Quantification by ELISA of IL-6 concentration in serum of B16-IL6KD tumor–bearing mice (n = 10 each genotype). F) Representative western blot image and densitometry values for HIF1α from B16 and LLC whole tumor extracts. Calnexin was used as an internal control. The subsequent quantification encompasses three independent western blot experiments. B16 and LLC cells were placed in hypoxia KD KD in vitro (1% O2). At different timepoints, nuclear proteins and total mRNA were collected. G and H) IL-6 mRNA quantification from B16, B16-IL6KD, LLC, and LLC-IL6KD as analyzed by qRT-PCR. Data summarizes the results obtained from two independent in vitro experiments. Data are presented as mean ± SD, *P < .05, **P < .01, by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. HIF1α = hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha; LLC = Lewis Lung Carcinoma.

Next, we generated B16-IL6KD tumors. IL-6 silencing did not alter the pericyte coverage observed in parental B16-F10 tumors (Supplementary Figures 1, A and B, and 6C, available online). IL-6 mRNA expression in B16-IL6KD tumors and from isolated tumor-infiltrating CD45+ was found to be equal between genotypes (Figure 5, A and B). We then analyzed the recruitment of Gr1+/CD11b+ cells to the B16-IL6KD and LLC-IL6KD tumors. We did not detect any differences in MDSCs between pericyte-deficient tumors and controls (Figure 5C; Supplementary Figure 5C, available online, and data not shown). Similarly, we found equal levels of CD45+ cells in tumors (Figure 5C; Supplementary Figure 5C, available online), Gr1+/CD11b+ cells in blood (Figure 5D; Supplementary Figure 5D, available online), and in IL-6 serum concentration (Figure 5E). In summary, pericyte deficiency results in increased IL-6 expression from the malignant cells, driving MDSC accumulation in tumors.

We studied the association between pericyte deficiency and IL-6 overexpression in malignant cells. As previously observed (28), the pericyte-deficient tumors (both B16-mock and B16-IL6KD) were statistically significantly more hypoxic than controls, as determined by HIF-1α stabilization (B16, P < .05; LLC, P = .03) (Figure 5F; Supplementary Figure 6E, available online) and by increased necrosis (Supplementary Figure 7B, available online). Interestingly, differences in HIF-1α stabilization were abrogated upon rescuing the pericyte coverage (B16-PDGF-B tumors) (Supplementary Figure 6E, available online). We then placed B16 and LLC cells in hypoxia (1% O2) in vitro and observed robust HIF-1α stabilization after three hours (Supplementary Figure 6D, available online). IL-6 mRNA expression was upregulated at 24 hours (B16 ≈ 20-fold; B16-IL6KD ≈ 6-fold), or later (LLC ≈ 2-fold at 24 hours, ≈ 4-fold at 48 hours) (Figure 5, G and H). Thus, we conclude that pericyte deficiency–driven hypoxia results in upregulation of IL-6 mRNA in the malignant cells.

Tumor-Dependent Outcome of Elevated Gr1+/CD11b+ Cells

Next, we aimed to determine the relevancy of the increased MDSC levels in pericyte-deficient mice (Table 1). We examined malignant cell apoptosis by TUNEL assay and both pdgfbret/ret B16 and LLC tumors showed statistically significant decreases in apoptosis relative to controls (B16, P = .03; LLC, P = .02) (Supplementary Figure 7A, available online). Normalizing the levels of Gr1+/CD11b+ cells by either rescuing pericyte coverage (B16-PDGF-B tumors) or inhibiting the recruitment of the double-positive cell population (B16-IL6KD tumors) resulted in identical numbers of malignant apoptotic cells (Supplementary Figure 7A, available online).

Table 1. Tumor phenotype and TILs in B16 and LLC pericyte-deficient tumors as compared with controls.

| Tumor characteristics | LLC | B16 | B16-IL6KD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor phenotype | |||

| Malignant cell apoptosis | decreased | decreased | unchanged |

| Tumor weight at resection* | increased | unchanged | unchanged |

| Circulating malignant cells | unchanged | increased | unchanged |

| TILs | |||

| MDSC | increased | increased | unchanged |

| CD8a, INFㆠ| decreased | unchanged | unchanged |

| CD4, CCL4, IL17γ† | unchanged‡ | increased | unchanged |

Tumor weight measured two weeks after cell inoculation. LLC = Lewis Lung Carcinoma; MDSC = myeloid-derived suppressor cells; TILs = tumor-infiltrating leukocytes.

TILs, mRNA expression of cytokines from isolated tumor-infiltrating CD45+ cells.

Decreased mRNA expression of CD4 and unchanged mRNA level of CCL4 and IL17a.

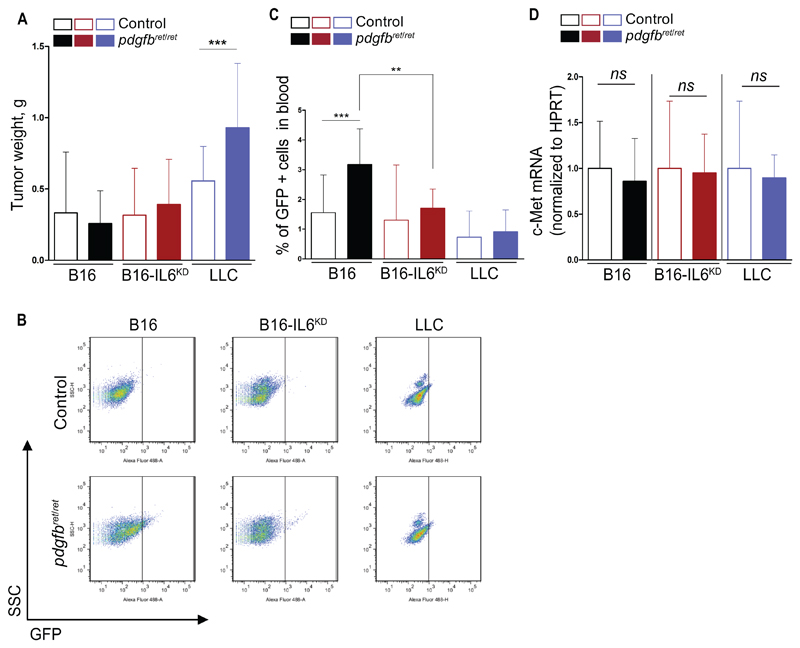

Next, we examined tumor growth in pericyte-deficient and control mice. Pericyte-deficient LLC tumors, but not B16 tumors, were statistically significantly larger when compared with controls (P = .001) (Figure 6A). We generated GFP-expressing cell lines (B16-GFP; LLC-GFP; B16-IL6KD-GFP), and then analyzed circulating malignant cells by FACS (Supplementary Figure 6F, available online). We found statistically significantly higher amounts of GFP+ cells in B16-GFP–bearing, pericyte-deficient mice (P = .001) but not in LLC-GFP–bearing mice (Figure 6, B and C). Interestingly, the difference was abolished in B16-IL6KD tumor–bearing mice (P = .008) (Figure 6, B and C). The increased frequency of circulating malignant cells was c-Met independent (28), because no differences in c-Met expression were found in B16 and B16-IL6KD tumors (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Biological outcomes of elevated myeloid-derived suppressor cell levels. B16, B16-IL6KD, and Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) tumor cells were inoculated s.c. in pdgfbret/ret and control mice. Tumors were resected and weighed and processed for mRNA extraction. A) Tumor weight measured at resection, two weeks after tumor cell inoculation (n = 24 to 25 for LLC tumors, n = 16 to 20 for B16 and B16-IL6KD tumors). Tumor cell lines engineered to express GFP were generated (B16-GFP, LLC-GFP, and B16-IL6KD-GFP). The modified cell lines were inoculated s.c. into pdgfbret/ret and control mice. Tumors and blood were collected three weeks after tumor cell inoculation. B and C) Representative dot plot and quantification of intravasated GFP–expressing tumor cells into the blood (n = 19 in each B16 group, n = 6 to 10 in each B16-IL6KD group, and n = 8 in each LLC group). D) mRNA quantification of c-Met in whole tumor extracts of B16, B16-IL6KD, and LLC tumor engraftments (n = 5 to 10). Data are presented as mean ± SD, NS = no statistical significance. **P < .01, ***P < .001 by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. c-Met = hepatocyte growth factor receptor; LLC = Lewis Lung Carcinoma.

We next examined mRNA expression from isolated tumor-infiltrating CD45+ cells. LLC tumors from pdgfbret/ret mice had statistically significantly lower levels of cytotoxic T-cell–related genes (mean ± SD: CD8a, control 1 ± 0.7; pdgfbret/ret 0.1 ± 0.1; P = .03; IFNγ, control 1 ± 0.7; pdgfbret/ret 0.3 ± 0.1; P = .04), whereas no differences were observed in TH17 cell–related genes (CD4, CCl4, and IL17a) (Supplementary Figure 6, G and H, available online). Conversely, B16 tumors had no differences in cytotoxic T-cell genes but elevated mRNA expression of TH17 cell–related genes (Supplementary Figure 6, G and H). Normalizing the recruitment of the double-positive population to tumors (B16-IL6KD) resulted in equal mRNA expression of all analyzed genes (Supplementary Figure 6, G and H, available online).

Examination of Pericyte and MDSC Markers in Human Breast Cancer Patients

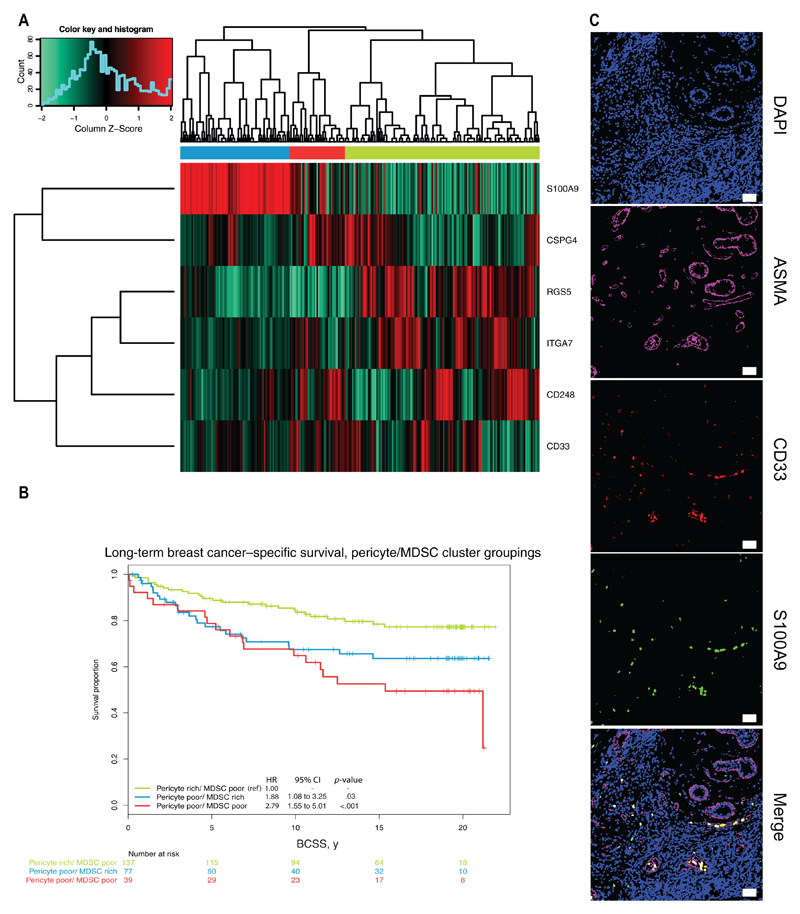

Our results suggest that tumor pericytes regulate MDSC burst in experimental models. We hypothesized that pericytes could also regulate MDSC trafficking to tumors in human malignancies. We analyzed the expression of pericyte markers (CSPG4, RGS5, CD248, ITGA7) as well as human MDSC markers (CD33, S100A9) (29) in a cohort of breast cancer patients (18,19). We readily identified a cluster of breast cancer patients that consistently displayed low expression of the pericyte genes with concomitant high expression of the human MDSC markers S100A9 and CD33 (Figure 7A). Notably, this cluster was associated with poor long-term breast cancer–specific survival (Cox proportional hazard ratio = 1.88, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.08 to 3.25, P = .03, based on two-sided Wald test, vs “pericyte rich, MDSC poor” reference group) (Figure 7B) and more aggressive clinico-pathological features, including estrogen and progesterone receptor negativity, higher tumor grade, and a high proportion of Basal-like, HER2-enriched and Luminal B tumors (P < .001) (Supplementary Table 1, available online). A trend towards [a higher rate of lymph node metastasis was also found for patients in these clusters but did not reach statistical significance (P = .11) (Supplementary Table 1, available online). The presence of CD33+/S100A9+ cells was confirmed immunohistochemically in human breast cancer tissue (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Expression of myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC)–related genes in a breast cancer patient cohort. Prespecified MDSC genes were extracted from the gene expression profiling of a large breast cancer cohort. A) Expression of the S100A9, RGS5, ITGA7, CD248, CSPG4, and CD33 genes in the 253 patients of the Uppsala dataset. B) Long-term breast cancer–specific survival curve, pericyte/MDSC cluster groupings (Cox proportional hazard ratio = 1.88, 95% confidence interval = 1.08 to 3.25, P = .03, based on two-sided Wald test, vs “pericyte rich, MDSC poor” reference group). C) Confocal images of human MDSC, CD33+/S100A9+ cells in tissue biopsy sample from breast cancer patients, stained with antibodies against αSMA (magenta), CD33 (red), and S100A9 (green). Nuclei are stained with DAPI. The panels are representative of at least 50 biopsies from breast cancer patients. Objective lens, 20x (dry). Scale bar = 50 μm. BCSS = breast cancer–specific survival; CI = confidence interval; CSPG4 = chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan 4; ITGA7 = integrin alpha-7; MDSC = myeloid-derived suppressor cells; RGS5 = regulator of G-protein signaling 5.

Discussion

Here we show that pericyte coverage of tumor vasculature is a critical factor for the accumulation of Gr1+/CD11b+ cells in the blood and neoplasms of tumor-bearing mice. The increased frequency of double-positive cells is specific, because we did not detect differences in healthy tissues nor in CD45+ cells. Although statistically significant, the MDSC increases observed in pericyte-deficient tumors when compared with controls were modest (Figure 1, A and B). However, in human malignant melanoma, slightly elevated monocytic MDSCs predicted poorer ipilimumab response, as measured in overall survival (25,30). Thus, small increases in infiltrating MDSC can potentially exert potent tumor-promoting effects.

The events resulting in MDSC accumulation in tumors are ill defined. Our results reveal that poor pericyte coverage elicits IL-6 overexpression specifically in malignant cells, leading to the expansion of MDSC in tumors. Mechanistically, hypoxia was found to be the factor behind this overexpression. Defective vascularization of tumor blood vessels caused by pericyte deficiency generates a more hypoxic microenvironment (28). Thus, pericyte coverage plays a critical role in regulating the immunogenic properties of tumors by altering the expression of relevant immune mediators in the malignant cells.

In healthy skin, immature myeloid cells stimulated tumor formation via Ccl4-dependent differentiation of CD4+ cells into IL-17A–expressing regulatory TH17 cells (29). We found the same genes upregulated in pdgfbret/ret melanoma (Supplementary Figure 6G, available online), indicating that regulatory TH17 could be recruited to B16 tumors in a similar fashion. IL-6 promotes regulatory TH17 cell differentiation; once present, regulatory TH17 cells may promote malignancy through a variety of mechanisms (31). In pdgfbret/ret LLC tumors however, no evidence of TH17 cell recruitment was found. Instead, we observed decreased expression of cytotoxic T-cell genes IFNγ and CD8a. It is tempting to speculate that the contrasting outcome of pdgfbret/ret B16 and LLC tumors reflects the different recruited MDSC subsets, myelocytic and granulocytic.

Interestingly, both pericyte deficiency and MDSC accumulation have been associated with increased malignancy (28,33–35). Poor pericyte coverage has been linked to increased vascular permeability (21,36,37), thus providing an easier passage for malignant cells through the dysfunctional vasculature (34). Yet, our IL-6 silencing data shows a normalized rate of circulating malignant cells in pericyte-deficient tumors (Figure 6C). As such, it is conceivable that cell trafficking and permeability to small molecules constitute two different features reflecting diverse hierarchical levels in the vascular barrier (21,38).

The pdgfbret/ret mouse is a well-established model of pericyte deficiency, and the degree of pericyte loss in different tissues and tumors has been analyzed in several reports (16,17,21,22,39). However, it is not trivial to translate our findings into human malignancies. Tumor pericytes are less abundant and establish less endothelial cell contact than pericytes in healthy tissues (40), and there are currently no biomarkers available that predict pericyte abundance and function. Thus, in order to address pericyte status in human tissues we rely on immunohistochemical analyses using a more or less specific pericyte marker (7). Many reports have studied pericytes in human malignancies by αSMA staining (33,41). Unfortunately, αSMA could also potentially identify perivascular myofibroblasts (7). Given these limitations, we examined genes representative of both pericyte coverage and the human MDSC markers CD33 and S100A9 in a publically available cohort of expression array–profiled breast cancer patients. We identified a subset of patients with decreased expression of pericyte markers who also overexpressed MDSC markers and were associated with poorer long-term survival. Of note, we could also detect MDSC in human breast cancer by immunohistochemistry. Although we acknowledge the limitations of studying pericytes in human malignancies, we feel that these results draw clear parallels to our observations in experimental tumor models, suggesting that pericytes may also regulate MDSC trafficking in human malignancies and confer a poor prognosis in breast cancer patients.

In summary, our work proposes for the first time that pericytes are key in mediating Gr1+/CD11b+ cell trafficking to tumors. Furthermore, we show that tumor pericytes manipulate the tumor microenvironment and modulate the expression of critical immune mediators in the malignant cells. Finally, our findings elucidate the cellular events that result in the recruitment of MDSCs to tumors. Collectively, our results propose a central role for tumor pericytes in regulating tumor immunogenicity.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Foundation (CAN-2013-0782 to GG); the Strategic Cancer Research Program at Karolinska (StratCan KI/DKFZ); the Åke Wiberg Foundation; Swedish Medical Society; the Magnus Bergwall Foundation; Hillevi Fries research fund in Uppsala; BRECT-Breast Cancer Theme Centrum at Karolinska Institute to AÖ, JB, and GG; and the Swedish Research Council–supported STARGET Linnéus Center of Excellence to AÖ, JB, RSJ, and GG.

Note

The study funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; nor the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Research support for clinical and translational–molecular biological studies from Astra Zeneca (grant with Karolinska Institute), Amgen, Bayer, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, and Sanofi-Aventis to Karolinska University Hospital or Karolinska Institute; no personal payments (to JB).

The authors thank Sidney M. Morris Jr. for the Arginase-1 antibody and the Scheele Animal House personnel for animal care.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pietras K, Ostman A. Hallmarks of cancer: interactions with the tumor stroma. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316(8):1324–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grivennikov SIS, Greten FRF, Karin MM. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140(6):883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Proebstl D, Voisin M-B, Woodfin A, et al. Pericytes support neutrophil sub-endothelial cell crawling and breaching of venular walls in vivo. J Exp Med. 2012;209(6):1219–1234. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nisancioglu MH, Mahoney WM, Kimmel DD, Schwartz SM, Betsholtz C, Genové G. Generation and characterization of rgs5 mutant mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(7):2324–2331. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01252-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamzah J, Jugold M, Kiessling F, et al. Vascular normalization in Rgs5-deficient tumours promotes immune destruction. Nature. 2008;453(7193):410–414. doi: 10.1038/nature06868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armulik A, Genové G, Betsholtz C. Pericytes: developmental, physiological, and pathological perspectives, problems, and promises. Dev Cell. 2011;21(2):193–215. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olson LE, Soriano P. PDGFRβ signaling regulates mural cell plasticity and inhibits fat development. Dev Cell. 2011;20(6):815–826. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gajewski TF, Meng Y, Blank C, et al. Immune resistance orchestrated by the tumor microenvironment. Immunol Rev. 2006;213:131–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(3):162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(4):253–268. doi: 10.1038/nri3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bunt SK, Yang L, Sinha P, Clements VK, Leips J, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Reduced inflammation in the tumor microenvironment delays the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and limits tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2007;67(20):10019–10026. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mundy-Bosse BL, Young GS, Bauer T, et al. Distinct myeloid suppressor cell subsets correlate with plasma IL-6 and IL-10 and reduced interferon-alpha signaling in CD4+ T cells from patients with GI malignancy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60(9):1269–1279. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1029-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen M-F, Kuan F-C, Yen T-C, et al. IL-6-stimulated CD11b + CD14 + HLA-DR – myeloid-derived suppressor cells, are associated with progression and poor prognosis in squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Oncotarget. 2014;5(18):8716–8728. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer C, Sevko A, Ramacher M, et al. Chronic inflammation promotes myeloid-derived suppressor cell activation blocking antitumor immunity in transgenic mouse melanoma model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(41):17111–17116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108121108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nisancioglu MH, Betsholtz C, Genové G. The absence of pericytes does not increase the sensitivity of tumor vasculature to vascular endothelial growth factor-A blockade. Cancer Res. 2010;70(12):5109–5115. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindblom P, Gerhardt H, Liebner S, et al. Endothelial PDGF-B retention is required for proper investment of pericytes in the microvessel wall. Genes Dev. 2003;17(15):1835–1840. doi: 10.1101/gad.266803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergh J, Norberg T, Sjögren S, Lindgren A, Holmberg L. Complete sequencing of the p53 gene provides prognostic information in breast cancer patients, particularly in relation to adjuvant systemic therapy and radiotherapy. Nat Med. 1995;1(10):1029–1034. doi: 10.1038/nm1095-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller LD, Smeds J, George J, et al. An expression signature for p53 status in human breast cancer predicts mutation status, transcriptional effects, and patient survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(38):13550–13555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506230102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker JS, Mullins M, Cheang MCU, et al. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(8):1160–1167. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armulik A, Genové G, Mäe M, et al. Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier. Nature. 2010;468(7323):557–561. doi: 10.1038/nature09522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abramsson A, Lindblom P, Betsholtz C. Endothelial and nonendothelial sources of PDGF-B regulate pericyte recruitment and influence vascular pattern formation in tumors. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(8):1142–1151. doi: 10.1172/JCI18549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinha P, Okoro C, Foell D, Freeze HH, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Srikrishna G. Proinflammatory S100 proteins regulate the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Immunol. 2008;181(7):4666–4675. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodriguez PC, Quiceno DG, Zabaleta J et al. Arginase I production in the tumor microenvironment by mature myeloid cells inhibits T-cell receptor expression and antigen-specific T-cell responses. Cancer Res. 2004;64(16):5839–5849. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weide B, Martens A, Zelba H, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells predict survival of patients with advanced melanoma: comparison with regulatory T cells and NY-ESO-1- or melan-A-specific T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(6):1601–1609. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: linking inflammation and cancer. J Immunol. 2009;182(8):4499–4506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furuhashi M, Sjöblom T, Abramsson A et al. Platelet-derived growth factor production by B16 melanoma cells leads to increased pericyte abundance in tumors and an associated increase in tumor growth rate. Cancer Res. 2004;64(8):2725–2733. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooke VG, LeBleu VS, Keskin D, et al. Pericyte depletion results in hypoxia-associated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis mediated by met signaling pathway. Cancer Cell. 2012;21(1):66–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ortiz ML, Kumar V, Martner A, et al. Immature myeloid cells directly contribute to skin tumor development by recruiting IL-17–producing CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2015;212(3):351–367. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitano S, Postow MA, Ziegler CGK, et al. Computational algorithm-driven evaluation of monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell frequency for prediction of clinical outcomes. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2(8):812–821. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bailey SR, Nelson MH, Himes RA, Li Z, Mehrotra S, Paulos CM. Th17 Cells in Cancer: The Ultimate Identity Crisis. Front Immunol. 2014;5 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Movahedi K, Guilliams M, Van den Bossche J, et al. Identification of discrete tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations with distinct T cell-suppressive activity. Blood. 2008;111(8):4233–4244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yonenaga Y, Mori A, Onodera H, et al. Absence of smooth muscle actinpositive pericyte coverage of tumor vessels correlates with hematogenous metastasis and prognosis of colorectal cancer patients. Oncology. 2005;69(2):159–166. doi: 10.1159/000087840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xian X, Håkansson J, Ståhlberg A, et al. Pericytes limit tumor cell metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(3):642–651. doi: 10.1172/JCI25705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Condamine T, Ramachandran I, Youn J-I, Gabrilovich DI. Regulation of tumor metastasis by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66(1):97–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-051013-052304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raines SM, Richards OC, Schneider LR, et al. Loss of PDGF-B activity increases hepatic vascular permeability and enhances insulin sensitivity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301(3):E517–E526. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00241.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zymek P, Bujak M, Chatila K, et al. The role of platelet-derived growth factor signaling in healing myocardial infarcts. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(11):2315–2323. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang EJ, Major S, Jorks D, et al. Blood-brain barrier opening to large molecules does not imply blood-brain barrier opening to small ions. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;52:204–218. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Genové G, Mollick T, Johansson K. Photoreceptor degeneration, structural remodeling and glial activation: A morphological study on a genetic mouse model for pericyte deficiency. Neuroscience. 2014;279:269–284. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morikawa S, Baluk P, Kaidoh T, Haskell A, Jain RK, McDonald DM. Abnormalities in pericytes on blood vessels and endothelial sprouts in tumors. Am J Pathol. 2002;160(3):985–1000. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64920-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Keeffe MB, Devlin AH, Burns AJ, et al. Investigation of pericytes, hypoxia, and vascularity in bladder tumors: association with clinical outcomes. Oncol Res. 2008;17(3):93–101. doi: 10.3727/096504008785055530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.