Summary

The genetic makeup of cancer cells directs oncogenesis and influences the tumor microenvironment. In this study, we massively profiled genes that functionally drive tumorigenesis using genome-scale in vivo CRISPR screens in hosts with different levels of immunocompetence. As a convergent hit from these screens, Prkar1a mutant cells are able to robustly outgrow as tumors in fully immunocompetent hosts. Functional interrogation showed that Prkar1a loss greatly altered the transcriptome and proteome involved in inflammatory and immune responses as well as extracellular protein production. Single cell transcriptomic profiling and flow cytometry analysis mapped the tumor microenvironment of Prkar1a mutant tumors, and revealed the transcriptomic alterations in host myeloid cells. Taken together, our data suggest that tumor-intrinsic mutations in Prkar1a lead to drastic alterations in the genetic program of cancer cells, thereby remodeling the tumor microenvironment.

eTOC

Codina et al. performed genome-scale in vivo CRISPR screens robustly identified multiple regulators of tumor-intrinsic factors that alter the ability of cells to grow as tumors across different levels of immunocompetence. Characterization of Prkar1a, a convergent hit from these screens, showed that its knockdown leads to drastic alterations in the phosphoproteome and transcriptome, corresponding to changes in the tumor microenvironment.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

As a key hallmark of cancer (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011), cancer cells have the ability to escape immune surveillance (Kim et al., 2007) using mechanisms such as immuno-editing (Dunn et al., 2002). Immune escape leads to resistance to various forms of cancer immunotherapy, especially checkpoint blockade immunotherapy (CBI), by primary, adaptive, or acquired resistance. A greater understanding of this process is therefore of central importance for improving clinical outcomes (Sharma et al. 2017). Complex genetic, cellular and immunological factors influence oncogenesis under a fully functional immune system (Chen and Mellman, 2013). The interactions between the immune system and cancer cells in are continuous, dynamic, and evolving. These interactions span from the initial establishment of a cancer cell to the development of metastatic disease, which is dependent on immune evasion, alteration of molecular features, cellular composition, and the tumor-immune microenvironment (Chen and Mellman, 2017). Our understanding of this phenomenon has just begun to be elucidated by pioneering studies, which have shown both tumor extrinsic and tumor intrinsic mechanisms. Tumor extrinsic mechanisms include non-tumor components within the tumor microenvironment, including regulatory T cells (Tregs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), M2 macrophages, and other inhibitory immune checkpoints. All of these are able to contribute to the inhibition of anti-tumor immune responses, and are thus also of fundamental importance to CBI efficacy (Sharma et al., 2017).

Tumor intrinsic mechanisms of immune evasion include a lack of antigenic proteins, low mutational burden, impaired antigen presentation by silencing or deletion of key molecules such as TAP, B2M, and HLA (Sharma et al., 2017). Additionally, constitutive expression of immunosuppressive ligands like PD-L1, either via transcriptional activation, epigenetic regulation or truncation of the 3’UTR has been shown to be immune-suppressive (Kataoka et al., 2016). Immune evasion can also arise from oncogenic pathways that directly influence the malignant nature of cancer cells, resulting in the alteration of the tumor-immune microenvironment. Examples include oncogenic signaling through the MAPK pathway resulting in the inhibition of T cell recruitment and function (Liu et al., 2013); loss of PTEN that enhances PI3K or ATK signaling (Lastwika et al., 2016; Parsa et al., 2007); EGFR mutations that activate PD-1 pathway (Akbay et al., 2013); overexpression of MYC that enforces the expression of CD47 or PD-L1 (Casey et al., 2016); expression of CDK5 to dampen the ability of T cells to reject tumors (Dorand et al., 2016); stabilization of P-catenin resulting in constitutive WNT signaling that induces T cell exclusion (Spranger et al., 2015); modulation of interferon gamma (IFNg) receptor signaling molecule Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) (Zaretsky et al., 2016)); direct changes in expression of INFg receptor 1 and 2 (IFNGR1 and IFNGR2) and interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1) (Gao et al., 2016); as well as epigenetic modifications of immune genes (Heninger et al., 2015).

Several screening systems in human cells and mouse models have previously demonstrated success in identifying essential genes in cancer immunotherapy (Manguso et al., 2017; Pan et al., 2018; Patel et al., 2017). We reasoned that performing in vivo tumorigenesis screens in hosts with different levels of immunocompetence would provide an approach to discover genetic factors in cancer cells that mediates tumor progression and immune response. Rag1−/− mice lack mature T and B cells due to the deficiency of Rag1. Nu/Nu are Foxn3 deficient and are athymic. C57BL/6 mice are commonly used wildtype mice fully immunocompetent. These mice represents with different levels of immunocompetence. In this study, through robust genetic screening, we have convergently identified Prkar1a as a potent suppressor of oncogenesis in multiple tiers of immunocompetence. We functionally interrogated its role in regulating gene expression and cellular properties for modulating the immune response and remodeling the tumor microenvironment.

Results

Convergent in vivo genome-scale knockout screens identify Prkar1a as a suppressor of oncogenesis across multiple hosts with different immune competence

We used a genome-scale in vivo CRISPR screening approach to identify oncogenic drivers in multiple hosts with different levels of immune competence. Specifically, we utilized a p53−/−;Myc-primed mouse hepatocyte cell line (denoted IM, or IMC9 after transduction with Cas9-GFP), which is immortalized but not transformed. We screened this line in multiple genotypes, including Rag1−/− mice, Nu/Nu mice, and fully immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice as a syngeneic host (Figure 1A). The hepatocytes were capable of forming tumors in Rag1−/− mice (10/10, 100%), but not Nu/Nu mice up to an injection dose of 10 million cells (0/10, 0%), suggesting that the immune system in Nu/Nu mice can keep tumor growth in check. In sharp contrast, when we mutagenized the cells with a genome-scale CRISPR knockout library (mBrie) (Doench et al., 2016) (Methods), all (21/21) injections led to rapid tumor formation (Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test, p = 7e-4) (Figure 1A–B; Figure S1A; Supplemental Table Sets TS1). Neither the parental line (0/4) nor the mBrie library mutagenized pool (0/20) was able to generate tumor in C57BL/6 mice observed for at least 90 days. These data together suggested that the loss-of-function mutations in a subset of genes enabled the cells to robustly grow tumors within the Nu/Nu host.

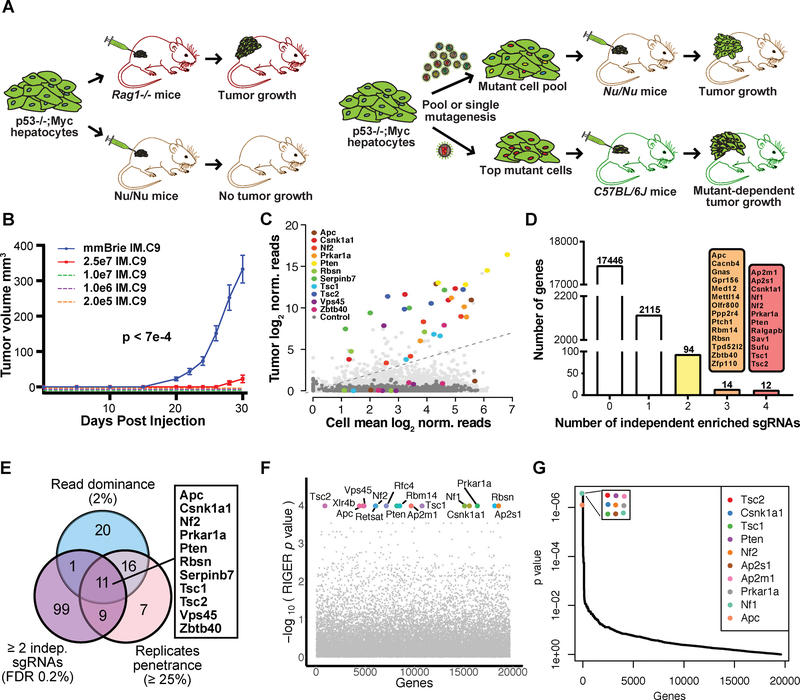

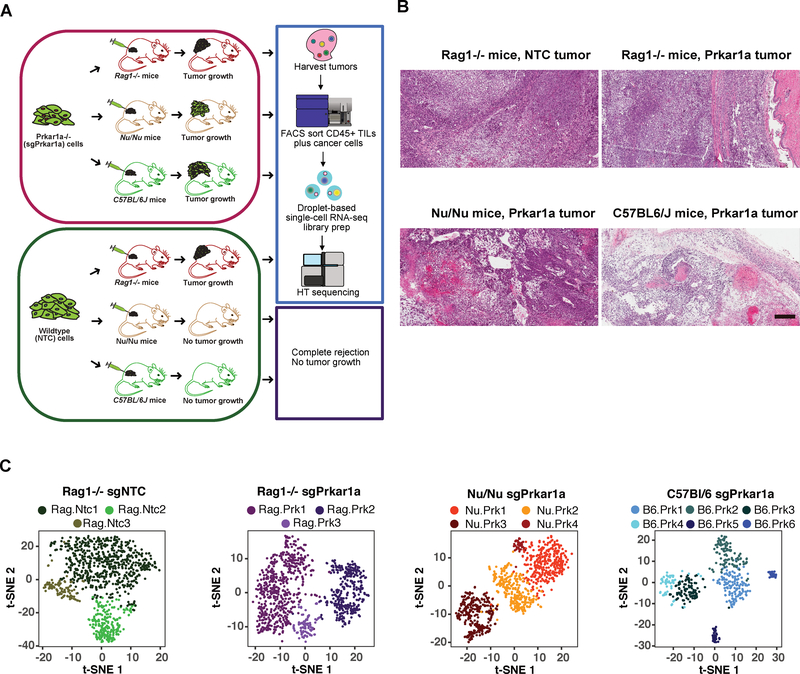

Figure 1. Genome scale in vivo CRISPR screens in different mouse hosts identified genes regulating oncogenesis.

(A) Schematics of experiment. Left, p53−/−;Myc mutated non-malignant hepatocyte cell lines are capable of growing as tumors in immunodeficient Rag1−/− mice with deficiency in both innate and adaptive immune system, however they are rejected by Nu/Nu mice. Right, genome-scale CRISPR screen and validation for mutants that can grow as tumors. Genome-scale CRISPR libraries (mBrie or mGeCKO) mutagenized cell pools have robust tumor growth in Nu/Nu host. Validation of individual gene mutant cells with top hits in mouse hosts with different levels of immune competence.

(B) Tumor growth curves of mBrie library transduced hepatocytes (n = 21), as compared to various injections using the parental cell line (n = 3 each) over a 30 day period (Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test, mBrie vs all controls, p = 7e-4). Error bars are s.e.m.

(C) A color-coded scatterplot showing hit identification for genes whose loss-of-function lead to consistent tumor growth. Screen was performed using a second-generation genome-scale CRISPR knockout library (mBrie) transforming hepatocytes that can grow in fully immunodeficient Rag1−/− mice but not in Nu/Nu mice that have competent innate immunity although lacking mature T cells. Library-transduced cells were capable of escaping the innate immune system and grew as tumors at 100% penetrance. Average sgRNA library representation across all Nu/Nu tumors (n = 21) was plotted against average sgRNA library representation across all cell replicates (n = 3). The 11 top hits that pass all three statistical criteria were plotted as color-coded dots with each dot representing one sgRNA where the same color represents independent sgRNAs for the same gene. Non-targeting control sgRNAs (NTCs) were shown as dark grey dots. Other gene-targeting sgRNAs (GTSs) were shown as light grey dots.

(D) A barplot of the number of independent scoring sgRNAs in the mBrie screen. False-discovery rate (FDR) of 0.2% was used as a cutoff for scoring in each tumor. Four sgRNAs per gene were contained in the mBrie library. Highly consistent hits with >=3 scoring sgRNAs (14 genes with 3/4 scoring sgRNAs, 12 genes with 4/4) were shown.

(E) A Venn diagram showing the overlap of hits identified using three selection criteria, revealing 11 genes significant regardless of criteria. The first criterion is by abundance (i.e. a gene with one or more sgRNA(s) comprising of >=2% total reads in a tumor); the second criterion is by phenotypic penetrance (i.e. a gene with the frequency of one or more sgRNA(s) passing FDR 0.2% cutoff across 25% of all independent tumor samples); the third criteria is by independent construct (i.e. a gene with >=2 sgRNA(s) passing FDR 0.2% cutoff).

(F) RIGER analysis of the genome-scale screen showing top hits.

(G) MAGeCK analysis of the genome-scale screen showing top hits.

See also: Figures S1 and S2.

To determine which mutants comprised the tumors that grew in Nu/Nu mice, we deep-sequenced the sgRNA library representations within the tumors, plasmid, and transduced cells prior to transplantation (Methods). Library representation analyses revealed high coverage in three infection control replicates (97.8% on average), and recurrent patterns of sgRNA representation in tumors (Correlation test among tumors, p < 2.2e-16) (Dataset S1; Figure S1B-C). Analyses of gene-targeting and non-targeting sgRNA distributions revealed a high consistency between replicates and the overall shifts between different sample types (Figure S1D–E), providing a high-quality genome-scale in vivo screen dataset for analysis of enriched sgRNAs in the outgrown tumors. When comparing the mean library representation of in vivo tumor cells to that in pre-injection cells, we detected a population of sgRNAs that were highly enriched in the tumors, many of which targeted the same gene with independent sgRNAs, whereas non-targeting control sgRNAs (NTCs) rarely conferred tumor outgrowth (Figure 1C; Figure S2A–B). By ranking the genes by the number of independent sgRNAs across all 21 tumors, we found that 2,335 genes have at least one significant sgRNAs passing a false-discovery rate (FDR) cutoff of 0.2% (Figure 1D). Out of those, 120 genes had more than two significant sgRNAs, and twelve genes had all four of their targeting sgRNAs significantly enriched, serving as independent evidence of the knockout effect (Figure 1D). We then analyzed sgRNA enrichment using criteria for sgRNA abundance and significant incidence rate across independent tumors (Figure 1E) and independent sgRNAs. This approach identified genetic mutants that represent strength of selection, prevalence of phenotype, and robustness of constructs, respectively. Our analyses revealed a three-way convergence of robust hits, identifying 11 genes that were significantly enriched over all statistical criteria, including Apc, Csnk1a1, Nf2, Prkar1a, Pten, Rbsn, Serpinb7, Tsc1, Tsc2, Vps45, and Zbtb40 (Figure 1E). Additional analyses using RIGER (Methods), an established CRISPR screen analytical pipeline that utilizes the 2nd-best performing sgRNAs, revealed a highly similar set of genes, with 16 genes at the maximum level of statistical significance (Supplemental Table Sets TS2–TS3; Figure 1F; Figure 2A). Further analysis using MAGeCK, a model-based approach with consideration of the empirical null distribution of NTCs (Methods), also identified a similar set of genes, with nine genes having top level statistical significance of positive selection signature (Supplemental Table Sets TS4–TS5; Figure 1G; Figure 2A). Therefore, this screen identified high-confidence, candidate genes that were strongly enriched in tumors that escaped the immune system of the Nu/Nu host.

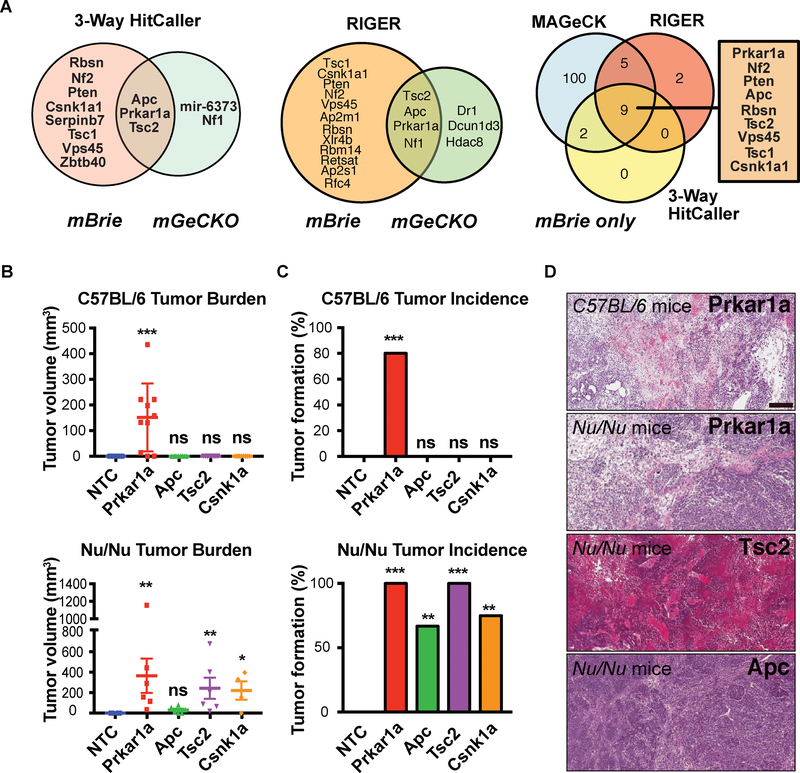

Figure 2. Convergent screen analysis and validation revealed Prkar1a mutant cancer cell robustly generate tumors in fully immunocompetent host.

(A) Venn diagram showing convergence of two genome-scale in vivo CRISPR screens, with hits identified using the custom 3-Way HitCaller pipeline (Left). The screen was repeated with a genome-scale CRISPR library (mGeCKO) and 5 genes were identified as top hits passing all statistical criteria. The mBrie screen and mGeCKO screen shared 3 hits: Prkar1a, Apc and Tsc2. (Middle) Convergence of two genome-scale in vivo CRISPR screens, with hits identified using RIGER. (Right) Convergence of mBrie in vivo CRISPR screens, showing consistent hits using three different hit calling algorithms (custom 3-Way HitCaller, MAGeCK and RIGER).

(B) Quantification of tumor sizes of top screen hit mutants. (Top) tumor volume measurement of mutants in C57BL/6J host 2 weeks post injection. Prkar1a mutant cells grew rapidly in this host, whereas NTC, Apc, Tsc2 or Csnklal mutants did not (n = 10 each); (Bottom) tumor volume measurement of mutants in Nu/Nu host 2.5 weeks post injection. Two-sided unpaired Mann-Whitney test was used to assess statistical significance for Prkar1a, Apc, Tsc2 or Csnklal mutants, relative to NTC (ns, not significant, i.e.*, p > 0.05; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001).

(C) Rate of tumor incidence of top screen hit mutants. (Top) tumor incidence rate of mutants in C57BL/6J host. Two-sided Fisher’s exact test was used to assess statistical significance for Prkar1a, Apc, Tsc2 or Csnk1a1 mutants, relative to NTC (ns, not significant, i.e. p > 0.05; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001).

(D) Representative H&E images of tumors in C. Scale bar, 250 μm.

See also: Figures S2 and S3.

To further enhance the rigor and stringency of identification, we repeated the screen with an independent CRISPR knockout library (mGeCKO) using the same optimized screening strategy (Dataset S2). This screen identified five top genes that passed the stringent statistical criteria using our custom 3-way hitcaller pipeline (FDR < 0.2%, >=2 sgRNAs, >=2% read abundance and >=25% of all tumors), of which three (Apc, Prkar1a, and Tsc2) overlap with the most stringent hits from the mBrie screen (Figure 2A). Similarly, four genes were identified as overlapping, stringent hits from both screens using RIGER and MAGeCK (Figure 2A). Multiple independent sgRNAs targeting these genes were consistently found at high levels across tumor samples relative to the infection-control cell samples, upon verification of single genes (Figure S2C–F). Apc, Prkar1a, and Tsc2 are the three genes that robustly emerged independent of statistical criteria, computational algorithm and screening library (Figure 2A; Figure S2C–F).

To validate Prkar1a and other top candidates, we performed tumor challenges that used single sgRNAs to target these genes in immortalized hepatocyte cells, followed by transplantation into Nu/Nu mice or fully immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice. Compared to NTC controls, all four top mutants identified from the screens were validated as potent tumor generators when transplanted into Nu/Nu mice (Figure 2B–D; Figure S3A–E). In sharp contrast, only the Prkar1a mutant is capable of generating tumors in immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice (Figure 2B–D), whereas mice challenged by cells with strong drivers mutated, including Apc, Tsc2 and Csnk1a1, remained tumor-free for the whole duration of experiment (60 days) (Figure 2B–D). These data indicated that Prkar1a knockout endowed the immortalized hepatocytes with the ability to develop tumors in fully immunocompetent hosts.

Phosphoproteomic characterization of Prkar1a mutants identified its downstream signaling targets

Due to the strong phenotype of Prkar1a knockout, we set out to interrogate the molecular regulation of Prkar1a and its downstream pathways. Prkar1a encodes the alpha regulatory subunit of the cAMP-Dependent Type I protein kinase (Protein kinase A, PKA). Due to the potential direct regulatory roles of Prkar1a in phosphorylation signaling, we investigated the changes in kinase activity and the phosphoproteome upon Prkar1a loss via stable isotope labeling using amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) (Figure 3A). Due to the amount of materials needed for SILAC experiments, we performed the proteomics experiments in culture outside a host context, with the goal to map out the cancer cells’ intrinsic properties.

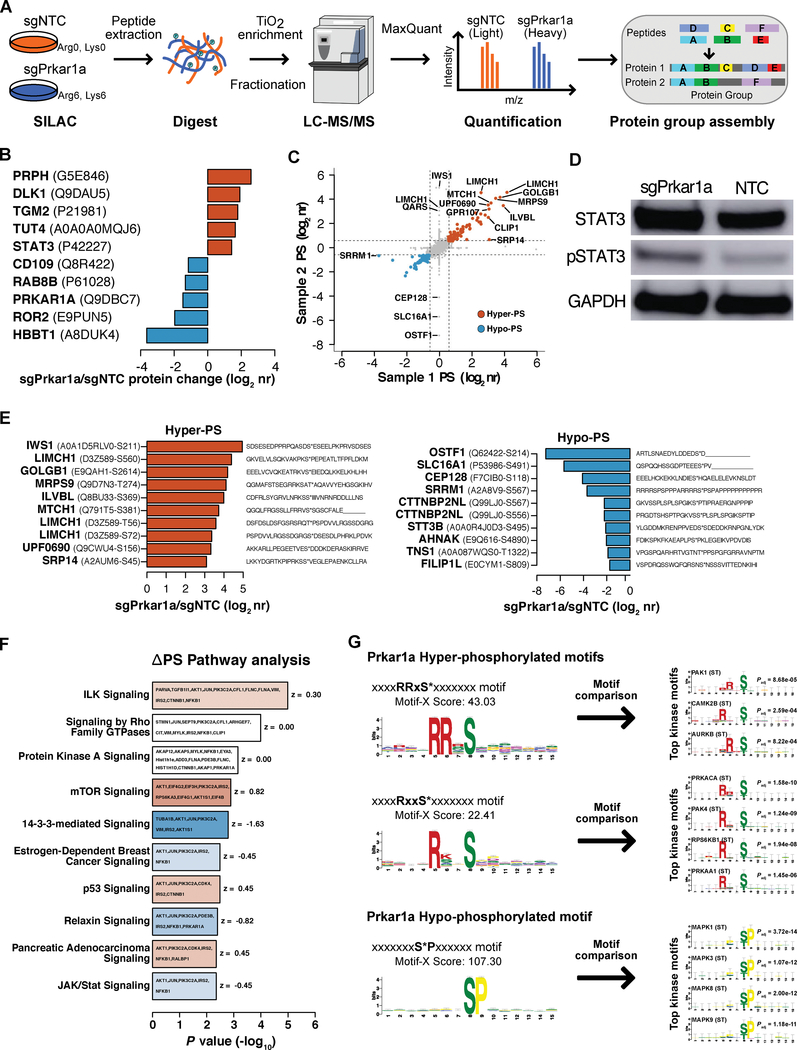

Figure 3. Phosphoproteomic characterization of Prkar1a mutant cells identified its downstream signaling targets.

(A) Schematics of Prkar1a phosphoproteomic experiments. Two independent sets of Prkar1a mutant and NTC control cells were compared using a multiplexed shotgun proteomics approach that included stable isotope labeling using amino acids in cell culture (SILAC), followed by protein extraction, trypsin digestion, TiO2 enrichment of phosphopeptides, cation exchange chromatography (CEX) fractionation and LC-MS/MS analysis by LTQ Orbitrap XL. Peptides were subsequently quantified, identified and assembled into groups of proteins, based on shared peptide sequences.

(B) Waterfall plots of the top upregulated and downregulated proteins as MS-identified protein groups in Prkar1a mutants. The protein level changes in Prkar1a mutants (Prkar1a /NTC log2 normalized-protein ratio (nr)) are plotted. As expected, the PRKAR1A protein is among the most downregulated.

(C) Color-coded scatterplot of differential phosphorylation between independent phosphoproteomic experiments. Phosphorylation changes in each Prkar1a mutant sample (Prkar1a /NTC log2 nr) are plotted for each phosphorylation site (PS). Hypo-PS and hyper-PS (> 1.5-fold change) are shown as respective blue and red dots, and top differential PS (ΔPS, > 3-fold change) are labeled with protein symbols.

(D) Western of STAT3 and phospho-STAT3 (pSTAT3) in Prkar1a mutant and NTC cell samples.

(E) Waterfall plots of the top hyper-phoshorylation site (PS) and hypo-PS in Prkar1a mutants (Left and right panels, respectively). The PS changes in Prkar1a mutants (Prkar1a /NTC log2 nr) are labeled with the gene symbol (bold), UniProt accession number and phosphorylated residue (in parentheses), as well as the peptide sequence in a 31 residue window, centered on the PS residue.

(F) Waterfall plot of the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of protein groups with PS changes (DPS; > 1.5-fold change) in Prkar1a mutants. The top ten canonical pathways are ranked by significance (−logi0 p value), and the bar colors represent the activation z score, which is presented to the right of each bar.

(G) Identification of hyper- and hypo-phosphorylation motifs in Prkar1a mutant cells. (Left) Sequence log-odds diagrams (Logos) are shown for hyper-PS (top) or hypo-PS (bottom) motifs that are over-represented in Prkar1a mutant cells. Each motif is presented above the Logo with an asterisk following the PS and a motif score for the enrichment below the motif. (Right) Logos are shown for the top kinase-interacting motifs that match to the identified hyper-PS (top) or hypo-PS (bottom) motifs in Prkar1a mutant cells. Up to four of the top kinase-substrate motifs (Bonferroni-adjusted p < 1e-3) are presented for each PS motif. All kinase-substrate motifs are shown with the significance of the motif match (upper right of each Logo) and the kinase name with phosphorylated residues in parentheses (upper left of each Logo).

We labeled the Prkar1a mutant cells (sgPrkar1a ) with Lys6/Arg6 “heavy” stable isotope and control cells (NTC) with Lys0/Arg0 “light” stable isotope, and proteins were extracted, mixed, trypsin-digested, TiO2-enriched for phosphopeptides, fractionated by cation exchange chromatography (CEX) and analyzed by LC-MS/MS using a LTQ Orbitrap XL (Methods). Two independent SILAC-pair replicates were used to compare Prkar1a mutants to control cells at the peptide, protein, and post-translational modification levels, at which we identified a respective 19,979 unique peptides (peptide spectrum matches, PSMs), 2,940 protein groups and 2,994 phosphorylation sites after strict quality control filtering (Datasets S3–S5). From this dataset, we identified differentially regulated proteins, as well as a set of differentially phosphorylated peptides upon Prkar1a loss, based on phosphorylation fold change at a peptide phosphorylation site (PS) and by the number of differentially phosphorylated peptides in a protein group (Figure 3B, C, E). As a robustness check, PRKAR1A protein level was confirmed to be one of the most downregulated proteins in the sgPrkar1a group (Figure 3B), validating the proteomics measurements. Additional validation of the data was assessed by the Western blot quantification of STAT3, one of the most upregulated proteins in the dataset and a key player in immune and inflammation signaling (Figure 3B, D). The proteins with the most significant hyper-phosphorylation upon Prkar1a loss included IWS1, LIMCH1 and GOLGB1 (Figure 3E). The phospho-signaling pathway changes in Prkar1a mutants, based on differentially phosphorylated proteins, showed that the most significantly enriched pathway change in Prkar1a mutants was integrin-linked kinase (ILK) signaling, Rho GTPase signaling, PKA signaling, mTOR signaling, JAK/STAT signaling and others, all of which modulate oncogenesis and ECM remodeling (Figure 3F). Comparative analysis of all PSs as a set showed a shift in the kinase activity of Prkar1a mutants, emphasized by alterations in the target motifs of differentially phosphorylated peptides, for which the hypo-phosphorylated peptides are enriched in the S*P motif, whereas the hyper-phosphorylated peptides are enriched in RRxS* and RxxS* motifs (Figure 3G). These data together revealed the proteome and phospho-proteome level alterations in Prkar1a mutant cells.

Whole transcriptome profiling identified deregulated gene expression programs in Prkar1a mutants

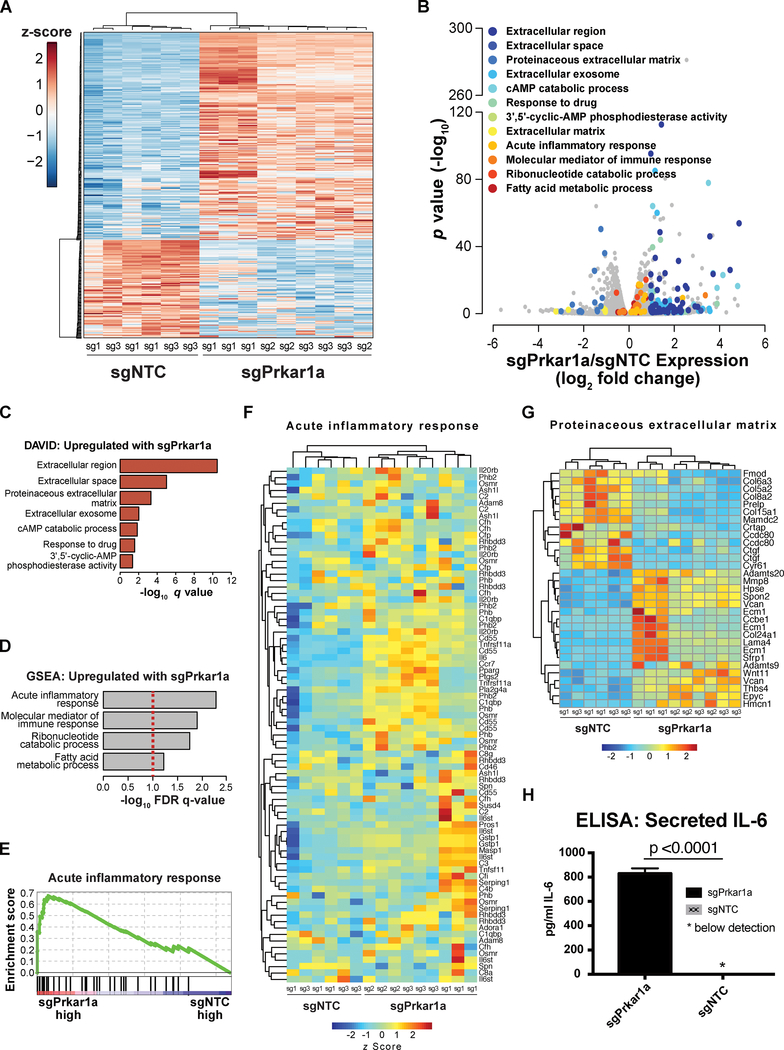

To further dissect the gene product changes downstream of phosphorylation, we utilized mRNA-sequencing (mRNA-seq) to profile the transcriptome of Prkar1a mutant cells together with matched NTC controls in culture, using three independent sgRNAs for sgPrkar1a and two independent NTCs, with three biological replicates for each sample group (Methods). We collected total RNA from IMC9 cells at 7 days-post-infection in biological triplicates and performed strand-specific, poly-A enriched mRNA-seq (Datasets S6). Using a differential expression analysis, we identified a set of 371 transcripts that are differentially expressed between Prkar1a mutant and wildtype cells, with 119 transcripts being down-regulated and 252 being up-regulated upon Prkar1a loss (Dataset S7, Figure 4A–B). These differentially expressed genes belonged to a distinct set of pathways with the most significantly upregulated genes centered on immune, inflammatory and secreted protein signatures (Figure 4B). Gene ontology analysis by the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) revealed that extracellular proteins were among the top categories of Prkar1a-upregulated genes, along with the anticipated on-target cAMP catabolic process signature mediated by the feedback regulation of PKA signaling via the Phosphodiesterases (Pde) gene family (Supplemental Table Sets TS6–TS7; Figure S4A). The immune, inflammatory and cAMP-catabolism signatures were recapitulated with gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (Supplemental Table Sets TS8–TS9; Figure 4D–E). A closer look of specific transcripts revealed that Prkar1a significantly upregulated genes encode inflammatory and secretory factors, such as cell surface proteins, cytokines, ECM proteins and molecular mediators of immune response (Figure 4F–G; Figure S4B). Using ELISA, we further confirmed that Prkar1a mutant cells turned on the protein production switch of IL-6, a pro-inflammatory cytokine with important roles in promoting tumor progression (Coussens and Werb, 2002) (Prkar1a vs NTC, > 800-fold change; p < 0.0001; Figure 4H). Moreover, STAT3 the transcription factor associated with IL-6 expression, was also found to be upregulated at the mRNA level, showing consistency between our proteomic and transcriptomic data sets (p = 6.1e-25). Echoing the phenotypes, these data suggest that cancer cell intrinsic Prkar1a-loss leads to upregulated production of secreted cytokines and extracellular proteins implicated in inflammatory response, which may influence the host tumor microenvironment (TME).

Figure 4. Whole transcriptome profiling of Prkar1a mutants identified an upregulated gene expression program of immune response and extracellular protein production.

(A) An overall heatmap of all differentially expressed genes between Prkar1a mutant and control cells. Three independent sgRNAs for Prkar1a and two independent NTCs were subjected to whole transcriptome analysis by mRNA-seq (n = 3 biological replicates for each sgRNA). Differential gene expression (upregulated or downregulated in Prkar1a mutants) is shown by z scores.

(B) A color-coded volcano plot of all differentially expressed transcripts between Prkar1a mutant and control cells. The statistical significance (−log10 FDR-corrected p value) was plotted against the log2 fold-change of normalized gene expression levels. Each dot represents one gene, which are color-coded by the most highly enriched gene sets, described in the legend.

(C) Waterfall plots of most significantly enriched gene ontologies for genes that are upregulated in Prkar1a mutants. The enrichment analysis was performed by the Database of Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID), and the top gene sets are shown, as ranked by FDR-corrected q values. Gene sets including extracellular or secreted proteins emerged on top as most enriched; Gene sets including cAMP catabolic process and response, as well as phosphodiesterase activity indicated the on-target activity of Prkar1a regulated PKA pathway.

(D) A waterfall plot of most significantly enriched gene sets of all Prkar1a upregulated genes. Pathway analysis was performed using GSEA with gene expression levels considered during enrichment calculation (methods), and the top gene sets are shown, as ranked by FDR-corrected q values. Gene sets including acute inflammatory response and molecular mediator of immune response emerged on top as the most significantly enriched ones; the gene set of ribonucleotide catabolic process indicated the on-target activity of Prkar1a regulated PKA pathway; Gene sets are not mutually exclusive.

(E) A GSEA individual pathway analysis plot showing the enrichment of acute inflammatory response genes in the Prkar1a mutant cells as compared to NTC.

(F) A heatmap of all differentially expressed transcripts between Prkar1a mutant and control cells for the genes in the acute inflammatory response category. Relative gene expression levels were shown as z scores.

(G) A heatmap of all differentially expressed transcripts between Prkar1a mutant and control cells for the genes in the proteinaceous extracellular matrix category. Relative gene expression levels were shown as z scores.

(H) A barplot of IL-6 ELISA between Prkar1a mutant and control cells.

See also: Figure S4.

Single-cell transcriptome profiling mapped the tumor microenvironment of Prkar1a mutant tumors in hosts of varying immunocompetence

To directly interrogate the host TME, we performed single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) (Methods), an approach that can elucidate both the gene expression signature and cell population structure in a high-throughput manner. We re-challenged Rag1−/−, Nu/Nu and C57BL/6 mice with Prkar1a and NTC cells (Figure 5A). As expected, Prkar1a cells grew tumors in all three mice genotypes, whereas NTC cells only grew in Rag1−/− (Figure 5A–B). We then sought to profile the tumor-infiltrating immune repertoire, and simultaneously profile the cancer cells in the same tumor. However, since the vast majority of cells in the tumor single cell suspensions are cancer cells, we performed FACS to purify both CD45+ immune cells and GFP+ cancer cells. Using these enriched immune cell populations, we subsequently spiked-in a smaller fraction of cancer cells taken from the same tumor. The single cells were barcoded and had cDNA libraries constructed in a single-cell manner, based on previously established methods (Gierahn et al., 2017; Macosko et al., 2015) (Methods) (Figure 5A) (Datasets S8–S14; Supplemental Table Sets TS10–TS14). The single-cell transcriptional data were dimensionality-reduced by principle components analysis (PCA), visualized by t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) and clustered by shared nearest neighbor (SNN) methods. The single-cell clustering identified distinct different subpopulations of the sequenced TME cellular repertoire for the Prkar1a and NTC tumors in Rag1−/− mice as well as the Prkar1a tumors in Nu/Nu and C57BL/6 mice (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Single cell profiling of Prkar1a mutant tumors in hosts of different immune competence.

(A) Schematic for single cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) experiments. IMC9 tumor cells were transfected with sgPrkar1a or NTC to generate Prkar1a knockout or control cells, respectively. Transfected IMC9 cells were then subcutaneously injected into immunocompromised (Rag1−/−), partially immunocompromised (Nu/Nu), and immunocompetent (C57BL/6) mice as shown, and the resulting tumors were extracted, then sorted to CD45+ tumor-infiltrating immune cells and tumor cells that were mixed in a 1:10 ratio for scRNA-seq. One representative mouse in each group was sequenced.

(B) H&E staining of tumors subjected to tumor-immune scRNAseq. Scale bar, 250 μm.

(C) Cellular populations within the tumor microenvironment, visualized by t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) plot of clustered, dimensionality-reduced single-cell transcriptional profiles. Each dot represents a single cell that is arranged relative to other cells based on transcriptional profiles, such that similar cells are grouped together.

See also: Figures S5, S6.

By merging the transcriptome data from the single cell populations of sgPrkar1a and sgNTC-generated tumors in Rag1−/− mice, we identified 3 clusters (Figure 6A), based on the optimal cell separation in the t-SNE embedding, canonical immune gene expression patterns, and optimal rank selection using non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) (Brunet et al., 2004; Gaujoux and Seoighe, 2010). We distinguished cluster 1 and 2 as immune cells, largely comprised of myeloid populations, based on the significantly up-regulated expression of Cd14, Fcgr3 (Cd16) and Fcgr2b (Cd32), as well as increased expression of Itgam (Cd11b) (MAST analysis; adjusted p < 1e-9) (Figure 6C; Figure S6), whereas cluster 3 cells are primarily cancer cells, based on expression of tumor-specific marker genes, Mgp, Fkbp11, Cdkn2a and Mrpl33, identified by comparing the most highly expressed genes in the IMC9 cells from bulk RNA-seq analysis to a reference panel of immune cells comprised of Immunological Genome Project data (ImmGen version 1) (Heng et al., 2008) (Figure 6C; Figure S5B; Figure S6). In addition, we classified the clusters into stromal and innate immune cell types by comparing the mean expression of cluster-specific differentially expressed genes (MAST analysis of each cluster relative to all other cells; adjusted p < 1e-3, 95th-percentile of |log-scale fold-change expression|) to an ImmGen reference panel, comprised of 85 cell types (Figure 6B; Figure S5D). This transcriptional comparison shows moderate correlation (Kendall correlation co-efficient τ > 0.3) between clusters 1–2 and myeloid cell types, including macrophage, dendritic cell (DC) and monocyte cells, with cluster 1 also correlating with granulocytic neutrophils (Figure 6B). In contrast, the cluster 3 population moderately correlated (τ > 0.3) with fibroblast cells and weakly (τ > 0.2) with endothelial and epithelial cells (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Differential single cell expression analysis of the immune microenvironment in the tumors induced by Prkar1a mutant and control cancer cells in Rag1−/− mice.

(A) t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) visualization of aligned single-cell transcriptional data generated from Prkar1a−/− or NTC tumors in Rag1−/− mice. Cells of the t-SNE plot are labeled by the tumor dataset (top) and by unsupervised clusters that were identified (bottom).

(B) Identification of cell cluster populations based on expression correlation to known immune cell populations. Cluster-specific marker genes were identified as differentially expressed genes (MAST analysis; FDR-adjusted p < 0.001) with the top 95% fold-change between clusters, and the log-normalized mean expression of these marker genes in each cluster was compared by Kendall correlation analysis to ImmGen V1 transcriptional data (85 cell populations of innate immune and stromal cells). The scaled correlation coefficients for the cluster-specific markers are shown for each ImmGen cell population, arranged by unsupervised hierarchical clustering, performed separately within 6 broad cell type categories of the ImmGen data.

(C) Classification of cell clusters by cell type-specific characteristic gene expression patterns, as shown by expression-labeled t-SNE plots. Clusters 1 and 2 are identified as myeloid cell populations by the gene expression of canonical myeloid cell surface markers such as Cd14, Fcgr3 (Cd16), Fcgr2b (Cd32) and Itgam (Cd11b). These clusters also express known markers of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). Cluster 3 represents the IMC9 cancer cells based on the expression of the previously defined IMC9-specific gene markers including Mgp, Fkbp11, Cdkn2a and Mrpl33.

(D) Volcano plots showing differentially expressed genes in the tumor microenvironment between the myeloid-like immune cells in tumors induced by Prkar1a−/− and control cells. Each panel shows a cluster-specific differential expression analysis, for which the FDR-adjusted p values are shown in the y axes and the log-scale expression fold-changes are shown in the x axes. Differentially expressed genes were defined as those with an adjusted p value < 0.01 and a fold-change > 1.8 in the Prkar1a knockout tumor model. Overexpressed and underexpressed genes are depicted by red and blue points, respectively.

See also: Figure S7.

Further categorization suggested that cluster 1 is best described as a population of tumor associated macrophages (TAMs), with significantly increased expression (adjusted p < 1e-8) of key TAM markers, including Cd68, Cd163 and Csf1r (Cd115) (Bronte et al., 2016). In addition, our data suggest that both immune cell clusters contain myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) with notable expression of multiple MDSC markers (Bronte et al., 2016), including significantly increased expression of Arg1, Cybb (Nox2) and Il4ra markers, relative to tumor cells of cluster 3 (Figure 6C, Figure S6). Once the clusters were characterized, we assessed the transcriptional differences related to Prkar1a loss, as it affects each cell cluster. These differential expression analyses show that Prkar1a loss is significantly associated with the increased expression of the inflammatory marker Saa3 in all three clusters (adjusted p < 1e-5), indicating that the inflammatory phenotype observed by RNA-seq is conferred to the TME. Decreased expression of MHCII genes in both immune cell clusters was also observed, including Cd74, H2-Aa, H2-Ab1 and H2-Eb1 (adjusted p < 1e-9; Figure 6D). In addition, the chemokine gene Cxcl13 is significantly increased in the cluster 1 cells (adjusted p < 4.23e-22; Figure 6D). Together, these data mapped the TME of Prkar1a mutant tumors in Rag1−/− mice and revealed the cellular repertoire as well as transcriptional changes in immune genes.

Next, we investigated whether the same immune infiltrates are found within immuno-competent C57BL/6 tumors, generated by the loss of Prkar1a. Wildtype tumors were not assessed in the immuno-competent background, as NTC tumors did not form in C57BL/6, therefore, only Prkar1a mutant tumors can be profiled in this host to serve as a refinement but not comparison. We repeated the single cell transcriptomics analysis of eGFP+ IMC9 and CD45+ immune cells of C57BL/6 tumors as a 1:10 mixed cell ratio, with the 10X Genomics platform for scRNA-seq library prep prior to sequencing. After pre-processing, we applied the Potential of Heat-diffusion for Affinity-based Trajectory Embedding (PHATE) technique (Figure S5C Left) (Moon et al., 2017). The ensuing population structure of the data showed a notable split into two discreet groups of cells, which represented immune and tumor subsets, based on the expression of Ptprc (Cd45) and Mgp genes, respectively (Figure S5C Right). As the expression of these genes was not detected in all cells, we partitioned the population structure into two clusters using unsupervised SNN clustering. Next, we investigated the immune cell populations in finer detail by subsetting the Ptprc+ cluster and visualizing the subpopulation structure by PHATE dimensionality reduction, followed by unsupervised clustering (Figure S5D). We next sought to categorize the five immune subpopulations by comparing the expression of cluster-specific genes (Methods) in each cluster to 107 known immune cells of a reference panel, comprised of neutrophils, macrophages, monocytes, dendritic cells (DCs), natural killer cells and T cells (Figure S5E). The correlation heatmap shows a macrophage signature in all immune subclusters, with the strongest macrophage-correlations to subclusters 1, 2 and 4 (τ > 0.5). These three clusters also have moderately high correlations to DCs and monocytes (τ > 0.4), whereas subcluster 3 correlates moderately high with neutrophil and macrophage cell types (τ > 0.4). In support of this cell type categorization, we show significantly increased expression of TAM-specific genes Adgre1 (F4/80), Csf1r (Cd115) and H2-Aa (MHC-II) in subcluster 4 (adjusted p < 1e-5; Figure S7). We also found significantly increased expression of various myeloid markers in the adjacent subclusters of 1 and 3, which might represent populations of MDSCs. We also show significantly upregulated expression of MDSC regulatory genes (Ddit3 and Sl00a8) and M-MDSC enzymes (Arg1 and Nos2) in subcluster 3 cells (Figure S7). Furthermore, the data shows increased trends in PMN-MDSC-related genes, Cybb (Nox2) and Cd244 (Figure S7). We see the expression of these immune cell type genes follow gradient-like expression patterns across cells in the PHATE plot (Figure S7 Bottom). As the PHATE dimensionality reduction technique has been shown to preserve both local and global relationships between cells (Moon et al., 2017), these gradient-like transcriptional trends may reflect a spectrum of the phenotype in these different myeloid cell types, which will be interesting to explore in future single-cell analyses. These data further corroborated the refined TME of Prkar1a mutant tumors in the fully immunocompetent C57BL/6 wildtype host.

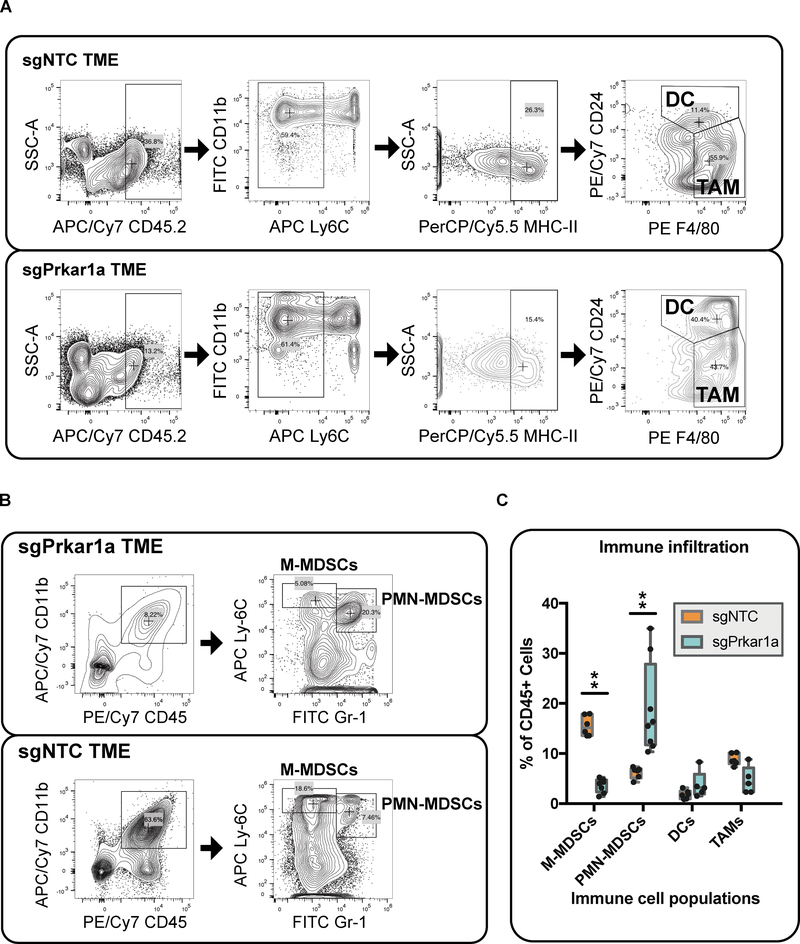

Flow cytometry confirms the alterations of tumor microenvironment in Prkar1a mutant tumors

To directly quantify Prkar1a knockout mediated differences in tumor-infiltrating immune cell populations, we performed flow cytometry on eight tumors with Prkar1a loss and six tumors without. First, we quantified dendritic cells and TAMs (Figure 7A, C), however there are no significant changes between Prkar1a knockout and wildtype tumors, yet there was a noteworthy decrease in TAMs in Prkar1a knockout tumors (Figure 7A, C). Subsequently, we inspected MDSC populations to show a significant increase of PMN-MDSCs and significant decrease of M-MDSCs in Prkar1a knockout tumors (adjusted p = 4.99e-7 and 1.88e-6, respectively; Figure 7B–C). Taken together, these data show that the loss of Prkar1a leads to a polarized recruitment of PMN-MDSCs, as well as a decrease in TAMs and the M-MDSCs from which they are derived, representing a substantial alteration of the host TME.

Figure 7. Flow cytometry analysis of the immune microenvironment in the tumors induced by Prkar1a mutant and control cancer cells.

(A-B) Flow cytometry plots present the differences in the quantities of specific immune cell subsets from tumors that were generated with or without Prkar1a loss.

(A) The gating schemes for the detection of dendritic cells (DCs) and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are presented using composite flow cytometry data from five sgPrkar1a-generated tumors or six sgNTC-generated tumors in Rag1−/− mice.

(B) Plots show the flow cytometry gating scheme for the quantification of monocytic and polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells (M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs, respectively) in tumors that were generated with or without Prkar1a loss. The composite flow cytometry data is shown for eight sgPrkar1a-generated tumors or six sgNTC-generated tumors in Rag1−/− mice.

(C) Quantitative analysis of immune cell infiltration differences between Prkar1a−/− and NTC tumors. Immune cells were quantified from the flow cytometry data in (A-B) and normalized to proportion of CD45/CD45.2+ cells for each tumor. The immune cell populations were compared between Prkar1a−/− and NTC tumors by unpaired t-test with Holm-Sidak correction for multiple-testing. Significant population changes are depicted with asterisks (**, adjustedp < 1e-5).

Discussion

Malignant transformation, oncogenesis, and evading immune destruction are all key hallmarks of cancer with fundamental roles in the cancer immune cycle with direct consequences on immunotherapy outcomes (Chen and Mellman, 2013; Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011; Sharma et al., 2017). Using multiple whole-genome knockout screens, we identified several candidate factors whose loss-of-function consistently led to tumor outgrowth in mouse hosts with different levels of immunocompetence. Knocking out several hits enabled the cells to grow out in Nu/Nu mice as tumors, while only Prkar1a knockout cells are able to grow in fully immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice. This is surprising given that under the same genetic context, knockouts of well-known tumor suppressors such as Tsc2 and Apc failed to grow in the C57BL/6 host. Prkar1a encodes a regulatory subunit of the PKA holoenzyme complex. Prkar1a is the only subunit of the four whose knockout leads to pronounced disease-related phenotypes. Prkar1a mutations were associated with disease in the Carney complex (CNC), a disease syndrome characterized by hyper-pigmented skin and sporadic neoplasias (Akin et al., 2017; Alband and Korbonits, 2014; Stratakis, 2016). In this context, hereditary or germline LOF mutations in Prkar1a were sufficient to produce the disease in a dominant manner. In addition, Prkar1a mutations are associated with several tumor types such as cardiac, endocrine, thyroid and lung adenocarcinoma (Kondo et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016) (Saloustros et al., 2017). Prkar1a overexpression is also associated with tumor formation in multiple contexts, indicating that altering Prkar1a function leads to differential phenotypes across cellular and genetic backgrounds. Additionally, recent clinical findings show that patients with a rare form of liver cancer, known as fibrolamellar HCC, harbor the classical DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion, which was recapitulated in mouse model of cancer (Kastenhuber et al., 2017; Rondell et al., 2017). This fusion protein results in hyperactive PKA signaling, similar to Prkar1a knockouts. Supporting the similarity, a subset of CNC patients also develop fibrolamellar HCC indicating significant overlap between the phenotypes (Rondell et al., 2017). Given the increased likelihood with which patients with CNC develop various types of tumors, Prkar1a was speculated to be a suppressor for early oncogenesis, where the immune system plays a fundamental role in clearing mutated cells with aberrant growth to preserves tissue homeostasis (Brown et al., 2017).

While its role as a tumor suppressor is now supported, the molecular changes associated with Prkar1a−/− mediated tumorigenesis are less clear. Reports have shown that Prkar1a knockout increases PKA activity, as well as resistance to apoptosis via mTOR activation (Robinson-White et al., 2006; Pringle et al, 2014). Additionally, it has also been shown that Prkar1a regulates the ERK/Snail/E-cadherin pathway (Wang et al, 2016). We investigated the mechanistic mechanisms of Prkar1a in cancer cells, showing that its genetic perturbation leads to drastic alterations in the proteome, phosphoproteome and the transcriptome. These changes center on acute inflammatory responses, mediators of immune response, and production of secreted ECM proteins and cytokines. For example, IL-6 production is dramatically upregulated, potentially enhancing Prkar1a−/− cells’ ability to drive inflammation in the absence of other cell types, as well as to drive early malignant transformation in both an autocrine and paracrine manner. Notably, a miRNA overexpressed in various cancers, miRNA-1246, targets PKA pathway genes leading to an inflammatory phenotype (Bott et al., 2017), which further supports our findings.

Single-cell transcriptome profiling and comparative analysis of Prkar1a mutant and wildtype tumor cells in Rag1−/− mice revealed the TME alterations in this host. The phenotypic effect of Prkar1a knockout is too strong to have comparable tumors in the hosts with more potent immune systems (Nu/Nu and C57BL/6, where Prkar1a wildtype cells cannot grow as tumors). The down-regulation of MHC-II in the immune cells of Prkar1a tumors on Rag1−/− mice may suggest gene expression changes in the tumor-associated macrophage populations or recruitment of myeloid-derived suppressive cells. Alternatively, the down-regulation of antigen presentation in resident macrophages is in line with the reduced MHCII expression. Furthermore, characterization of the immune cell infiltrate by flow cytometry in Rag1−/− mice showed a significant increase of PMN-MDSCs relative to controls. PMN-MDSCs are antigen specific immunosuppressive cells, known to down-regulate cytotoxic T-cell activity resulting in tumor specific T-cell tolerance (Kumar et al., 2016). While additional studies will need to be performed to understand the significance of this finding, it raises the possibility that the PMN-MDSCs could play an outsized role in regulating the growth of Prkar1a−/− tumors in hosts with intact adaptive immune system. Future molecular characterization of Prkar1a may further unveil the detailed molecular, cellular and immunological mechanisms underlying TME changes driven by this gene or other tumor-intrinsic factors. In summary, by convergent genome-scale screens and multiple sets of functional interrogation, we have identified Prkar1a as a gene regulating a tumor-intrinsic genetic program for remodeling the tumor microenvironment.

STAR Methods

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

All resources related to this work are available upon reasonable request to the lead contact, Sidi Chen (sidi.chen@yale.edu).

METHOD DETAILS

Cell culture

Immortalized hepatocyte cell lines with the background of p53−/−;cMyc (IM and 172) were from (Zender et al., 2006). Lung cancer cells were from (Kumar et al., 2009). Cells were transduced with lenti-Cas9 or lenti-Cas9-GFP to generate Cas9-positive cells. All cell lines were grown under standard conditions using DMEM containing 5% FBS & 1% Penstrep in a CO2 incubator unless otherwise noted. Cell culture for SILAC experiment was described below.

Mice

Several mouse strains with various levels of immunocompetence were used as transplant hosts, including C57BL/6, Nu/Nu and Rag1−/−. Mice, both sexes, between the ages of 6–12 weeks of age were used for the study. All animals were housed in standard individually ventilated, pathogen-free conditions, with 12h:12h or 13h:11h light cycle, room temperature (21–23°C) and 40–60% relative humidity. When a cohort of animals was receiving multiple treatments, animals were randomized by 1) randomly assign animals to different groups using littermates, 2) random mixing of females prior to treatment, maximizing the evenness or representation of mice from different cages in each group, and/or 3) random assignment of mice to each group, in order to minimize the effect of gender, litter, small difference in age, cage, housing position, where applicable. All mouse experiments follow ARRIVE guidelines.

Virus production of CRISPR library

First-generation and second-generation mouse genome-scale CRISPR sgRNA libraries, mGeCKO and mBrie, respectively, from (Sanjana et al., 2014) and (Doench et al., 2016). Libraries were amplified and re-sequenced by barcoded Illumina sequencing with customized primers to ensure proper representation. For virus production, envelope plasmid pMD2.G, packaging plasmid psPAX2, and library plasmid were added at ratios of 1: 1:2.5, and then polyethyleneimine (PEI) was added and mixed well by vortexing. The solution was stand at room temperature for 10–20 min, and then the mixture was dropwisely added into 80–90% confluent HEK293FT cells and mixed well by gently agitating the plates. Six hours post-transfection, fresh DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Pen/Strep was added to replace the transfection media. Virus-containing supernatant was collected at 48 h and 72 h post-transfection, and was centrifuged at 1500 g for 10 min to remove the cell debris; aliquoted and stored at −80°C. Virus was titrated by infecting IM cells at a number of different concentrations, followed by the addition of 2 μg/mL puromycin at 24 h postinfection to select the transduced cells. The virus titers were determined by calculating the ratios of surviving cells 48 or 72 h post infection and the cell count at infection.

Cellular CRISPR library production

Cells were transduced at 500x or higher coverage and at MOI between 0.2 to 0.4 to ensure sufficient coverage of the library and low percentage of multiple infectants, using a method similar to (Chen et al., 2015; Shalem et al., 2014).

Cell library transplantation

Un-transduced and library-transduced cells were injected subcutaneously into the right and left flanks of Nu/Nu mice at 2e7 cells per flank. The mGeCKO- or mBrie- transduced IMC9 cells were treated in a similar manner, with the exception that 2.5e7 cells were injected into the right flank only. Tumors were measured every 2–3 days by caliper and their sizes were estimated as spheres. Statistical significance was assessed by Welch’s t-test, given the unequal sample numbers and variances for each treatment condition.

Mouse organ dissection, imaging, and histology

Mice were sacrificed by carbon dioxide asphyxiation or deep anesthesia with isoflurane followed by cervical dislocation. Mouse livers and other organs were manually dissected and examined under a fluorescent stereoscope (Zeiss). Organs were then fixed in 4% formaldehyde or 10% formalin for 48 to 96 hours, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 6 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for pathology. For tumor size quantification, H&E slides were scanned using an Aperio digital slidescanner (Leica). Tumor sizes in area were measured using ImageScope (Leica). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was done with well-established markers using standard protocols (see key resources table for reagent information). IHC staining quantification was done manually using ImageScope (Leica), where applicable.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Phospho-Stat3 (Tyr705) (D3A7) XP | Cell Signaling Technologies | Catalog Number: 91455 |

| Stat3a (D1A5) XP® Rabbit mAb #8768 | Cell Signaling Technologies | Catalog Number: 8768 |

| GAPDH antibody | Santa Cruz Biotech | Catalog Number: 32233 |

| Ultra-LEAF™ Purified anti-mouse CD3e Antibody (clone: 145-2C11) | Biolegend | Catalog Number: 100340 |

| APC anti-mouse CD3e Antibody (clone: 145-2C11) | Biolegend | Catalog Number: 100312 |

| FITC anti-mouse Ly-6G/Ly-6C (Gr-1) Antibody (clone: RB6-8C5) | Biolegend | Catalog Number: 108405 |

| FITC anti-mouse/human CD11 b Antibody (clone: M1/70) | Biolegend | Catalog Number: 101206 |

| PE/Dazzle594 anti-mouse CD11c Antibody (clone: N418) | Biolegend | Catalog Number: 117348 |

| PerCP/Cy5.5 anti-mouse I-A/I-E Antibody (clone: m5/114.15.2) | Biolegend | Catalog Number: 107626 |

| APC anti-mouse Ly-6C Antibody (clone: HK1.4) | Biolegend | Catalog Number: 128016 |

| PE anti-mouse F4/80 Antibody (clone: BM8) | Biolegend | Catalog Number: 123110 |

| APC/Cy7 anti-mouse CD45.2 Antibody (clone: 104) | Biolegend | Catalog Number: 109824 |

| APC/Cy7 anti-mouse/human CD11b Antibody (clone: M1/70) | Biolegend | Catalog Number: 101225 |

| PE/Cy7 anti-mouse CD24 Antibody (clone: M1/69) | Biolegend | Catalog Number: 101822 |

| PE/Cy7 anti-mouse CD45 Antibody (clone: 30-F11) | Biolegend | Catalog Number: 103113 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| One Shot Stbl3 Chemical Competent E. coli | ThermoFisher | Catalog Number: C737303 |

| Endura™ ElectroCompetent Cells | Lucigen | Catalog Number: 60242-2 |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Qubit™ dsDNA HS Assay Kit | ThermoFisher | Catalog Number: Q32854 |

| Chromium Single Cell | 10x Genomics | |

| Gibson Assembly® Master Mix | NEB | Catalog Number: E2611 |

| Collagenase, Type IV, powder | ThermoFisher | Catalog Number: 17104019 |

| QuickExtract DNA Extraction Solution | Epicenter | Catalog Number: QE09050 |

| Proteinase K | Sigma-Aldrich | Catalog Number: 3115879001 |

| RNAse A | Qiagen | Catalog Number: 19101 |

| Phusion Flash High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix | ThermoFisher | Catalog Number: F548L |

| DreamTaq Green PCR Master Mix (2X) | ThermoFisher | Catalog Number: K1082 |

| E-Gel™ Low Range Quantitative DNA Ladder | ThermoFisher | Catalog Number: 12373031 |

| T7E1 | NEB | Catalog Number: M0302L |

| TRIzol™ Plus RNA Purification Kit | ThermoFisher | Catalog Number: 12183555 |

| QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit | Qiagen | Catalog Number: Q28706 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| UniProt C57BL6J UP000000589 proteome (last modified: May 16, 2017) | Bayona-Bafaluy et al., 2003; Church et al., 2009 | http://www.uniprot.org/proteomes/UP000000589 |

| PhosphoNetworks kinase phosphorylation motif data | Hu et al., 2014a; Hu et al., 2014b; Newman et al., 2013 | http://www.phosphonetworks.org/download/motifMatrix.csv |

| Immunological Genome Project expression data (version 1) | Heng et al., 2008 | GEO: GSE15907 |

| Mouse genome (mm10) | Macosko et al., 2015 | GEO: GSE63472 |

| Prkar1a mutant mRNA-seq | This study | SRA: PRJNA506858 |

| Prkar1a mutant proteomics | This study | PRIDE: PXD011837 |

| Prkar1a mutant single cell RNA-seq | This study | GEO: PRJNA509929 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| HEK293FT | ThermoFisher | Catalog Number: R70007 |

| Myc;p53−/− hepatocyte | Zender et al. 2006 | Clone IM |

| Myc;p53−/− hepatocyte | Zender et al. 2006 | Clone 172 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| C57BL/6J | Jackson Laboratory | Catalog Number: 000664 |

| Nu/Nu | Jackson Laboratory | Catalog Number: 002019 |

| Rag1−/− | Jackson Laboratory | Catalog Number: 002216 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| mGeCKOa | Sanjana et al., 2014 | https://www.addgene.org/pooled-library/zhang-mouse-gecko-v2/ |

| mBrie | Doench et al. 2014 | https://www.addgene.org/pooled-library/broadgpp-mouse-knockout-brie/ |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| FlowJo softward 9.9.6 | FlowJo, LLC | |

| Cutadapt 1.12 | Martin et al., 2011 | https://github.com/marcelm/cutadapt/ |

| Bowtie 1.1.2 | Langmead et al., 2009 | https://sourceforge.net/projects/bowtie-bio/files/bowtie/1.1.2 |

| GSEA | Subramanian et al., 2005 | http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/ |

| DAVID | Huang et al., 2009 | https://david.ncifcrf.gov/ |

| Scran R package | Lun et al., 2016 | https://github.com/MarioniLab/scran/ |

| Rtsne R package | Maaten, 2014; Maaten and Hinton, 2008 | https://github.com/jkrijthe/Rtsne/ |

| Edge R package | Robinson et al., 2010 | https://github.com/StoreyLab/edge/ |

| Panther classification system | Mi et al., 2013 | http://pantherdb.org/ |

| RIGER | Luo et al. 2008 | https://software.broadinstitute.org/GENE-E/extensions/RIGER.jar |

| MAGeCK | Li et al. 2014 | http://mageck.sourceforge.net |

| Dropseq_tools-1.12 | Macosko et al., 2015 | http://mccarrolllab.com/dropseq/ |

| Seurat R package | Satija et al., 2015 | http://satijalab.org/seurat/ |

| STAR 2.5.3a | Dobin et al., 2013 | https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR/ |

| R: The R Project for Statistical Computing | The R Foundation | https://www.r-project.org/ |

| MaxQuant version 1.6.0.1 | Tayanova et al., 2016 | https://www.biochem.mpg.de/511795/maxquant |

| MEME software suite version 4.12.0 | Bailey et al., 2009 | http://meme-suite.org/ |

| Tomtom motif comparison | Gupta et al., 2007 | http://meme-suite.org/ |

| Kallisto | Bray et al., 2016 | https://pachterlab.github.io/kallisto/ |

| Sleuth | Pimentel et al., 2017 | http://pachterlab.github.io/sleuth/ |

| Picard 2.9.0 | Broad Institute, 2018 | http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/ |

| Modification Motifs (MoMo) | Cheng et al., 2017 (BioRx) | http://meme-suite.org/ |

| Ingenuity Pathway Analysis | Qiagen | https://analysis.ingenuity.com |

| phateR R package | Moon et al., 2017 (BioRx) | https://github.com/KrishnaswamyLab/phateR |

| MAST R package | McDavid et al., 2017 | https://github.com/RGLab/MAST/ |

| pheatmap R package | Kolde, 2018 | https://github.com/raivokoldeZpheatmap |

| Other | ||

Mouse tissue collection for molecular biology

Mouse organs were dissected and collected manually under a dissection scope where applicable. For molecular biology, tissues were flash frozen with liquid nitrogen, ground in 24 Well Polyethylene Vials with metal beads in a GenoGrinder machine (OPS diagnostics). Homogenized tissues were used for DNA/RNA/protein extractions using standard molecular biology protocols.

Genomic DNA extraction

A total of 3e7 cells per replicate, or 200–800 mg of frozen ground tissue each sample, was used for gDNA extraction for library readout. Samples were re-suspended in 6 mL of NK Lysis Buffer (50 mM Tris, 50 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, pH 8.0) supplemented with 30 μL of 20 mg/mL Proteinase K (Qiagen) in 15 mL conical tubes, and incubated at 55 °C bath for 2 h up to overnight. After all the tissues have been lysed, 30 μL of 10 mg/mL RNAse A (Qiagen) was added, mixed well and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Samples were chilled on ice and then 2 mL of pre-chilled 7.5 M ammonium acetate (Sigma) was added to precipitate proteins. The samples were inverted and vortexed for 15–30 s and then centrifuged at ≥ 4,000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was carefully decanted into a new 15 mL conical tube, followed by the addition of 6 mL 100% isopropanol (at a ratio of ~ 0.7), inverted 30–50 times and centrifuged at ≥ 4,000 g for 10 minutes. Genomic DNA should be visible as a small white pellet. After discarding the supernatant, 6 mL of freshly prepared 70% ethanol was added, mixed well, and then centrifuged at ≥ 4,000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded by pouring; and remaining residues was removed using a pipette. After air-drying for 10–30 min, DNA was re-suspended by adding 200–500 μL of Nuclease-Free H2O. The genomic DNA concentration was measured using a Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific), and normalized to 1000 ng/μL for the following readout PCR.

Demultiplexing and read preprocessing

Raw single-end fastq read files were filtered and demultiplexed using Cutadapt (Martin, 2011). To remove extra sequences downstream (i.e. 3’ end) of the sgRNA spacer sequences, we used the following settings: cutadapt --discard-untrimmed -a GTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATGGC. As the forward PCR primers used to readout sgRNA representation were designed to have a variety of barcodes to facilitate multiplexed sequencing, we then demultiplexed these filtered reads with the following settings: cutadapt -g file:fbc.fasta --no-trim, where fbc.fasta contained the 12 possible barcode sequences within the forward primers. Finally, to remove extra sequences upstream (i.e. 5’ end) of the sgRNA spacers, we used the following settings: cutadapt --discard-untrimmed -g GTGGAAAGGACGAAACACCG. Through this procedure, the raw fastq read files could be pared down to the 20bp sgRNA spacer sequences.

Mapping of sgRNA spacers and quantitation of sgRNAs

Having extracted the 20 bp sgRNA spacer sequences from each demulitplexed sample, we then mapped the sgRNA spacers to the library from which they originated (either mGeCKO or mBrie). To do so, we first generated a bowtie index of either sgRNA library using the bowtie-build command in Bowtie 1.1.2 (Langmead et al., 2009). Using these bowtie indexes, we mapped the filtered fastq read files using the following settings: bowtie -v 1 --suppress 4,5,6,7 --chunkmbs 2000 --best. Using the resultant mapping output, we quantitated the number of reads that had mapped to each sgRNA within the library. To generate sgRNA representation barplots, we set a detection threshold of 1 read, and counted the number of unique sgRNAs present in each sample.

Normalization and summary-level analysis of sgRNA abundances

We normalized the number of reads in each sample by converting raw sgRNA counts to reads per million (rpm). The rpm values were then subject to log2 transformation for certain analyses. To generate correlation heatmaps, we used the NMF R package (Gaujoux and Seoighe, 2010) and calculated the Pearson correlations between individual samples using log2 rpm counts. To calculate the cumulative distribution function for each sample group, we first averaged the normalized sgRNA counts across all samples within a given group. We then used the ecdfplot function in the latticeExtra R package to generate empirical cumulative distribution plots.

Determining significantly enriched sgRNAs (custom 3-Way HitCaller)

Three criteria were used to identify enriched sgRNAs / genes: 1) if an sgRNA comprised ≥ 2% of the total reads in at least one tumor sample; 2) if an sgRNA was deemed statistically significantly enriched in ≥ 25% of all tumor samples (for mBrie) or ≥ 50% of all tumor samples (for mGeCKO) using a false-discovery rate (FDR) threshold of 2% based on the abundances of all nontargeting controls; or 3) if ≥ 2 independent sgRNAs targeting the same gene were each found to be statistically significant at FDR < 2% in at least one tumor sample. For the first and second criteria, individual sgRNA hits were collapsed to genes to facilitate comparisons with the hits from the third criteria.

Individual gene validation in Nu/Nu and C57BL/6J mice

Two to three sgRNAs were chosen for each validation target, corresponding to the most highly enriched sgRNAs found within tumors. Additionally, 3 NTCs sgRNAs were chosen randomly from the mGeCKO library to serve as negative controls. All sgRNA spacers were cloned in to lentiviral backbone, and virus was produced in HEK293FT cells as described above at a lower scale. IM.C9 cells were infected with validation constructs and selected for via 5 μg/mL puromycin treatment to produce KO cell lines. For each cell line 4e5 cells were injected into both flanks of a Nu/Nu or C57BL/6 mouse 5–7 days post viral infection. Tumors were measured by caliper every 2–3 days to assess growth rate.

SILAC proteomics sample preparation

Both sgPrkar1a and NTC transduced IMC9 cells were grown in standard tissue culture conditions as described previously, with the exception of the media used. sgPrkar1a cells were cultured with media containing lys6 and arg6 isotopes, deficient in the regular forms of the amino acids. NTC cells were grown in standard media. Cells were cultured for one week, and > 5 passages to promote full incorporation of the heavy isotopes. Cells were counted using a countess II machine and trypan blue staining. Protein was subsequently extracted with RIPA buffer on ice for 30 minutes, using 200 μ l lx buffer per million cells. Lysate was then spun down for 15 min at 14,000g. Protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) was then added to the extracted supernatant to prevent degradation. Protein concentration was measured and then normalized by Bradford assay with BSA standard. Following Bradford lysates from heavy sgPrkar1a cells and light NTC cells were mixed in a 1:1 ratio, followed by phosphopeptide enrichment. The flowthrough fractions contain unmodified peptides and the eluate fractions contain phosphopeptides, which were subjected to MassSpec analysis.

Proteomics analysis

Proteomic quantification and analysis of SILAC-labeled samples was performed using MaxQuant version 1.6.0.1 (Tyanova et al., 2016). Specifically, raw LC-MS/MS data files were analyzed using the default Orbitrap and MS/MS instrument parameters for Arg6/Lys6 “heavy” and Arg0/Lys0 “light” double SILAC-labeled peptides that had no more than three labeled residues. Peptide searches were then performed using a reference panel, derived from the in silico trypsin digest of the UniProt C57BL/6J mouse reference proteome (Proteome ID: UP000000589; last modified: May 16, 2017) (Bayona-Bafaluy et al., 2003; Church et al., 2009) with a maximum of 2 missed cleavage sites. These peptide searches included carbamidomethyl (C) as a fixed modification, as well as oxidation (M), acetyl (N-terminal), Gln/Glu -> pyro-Glu, phospho (STY) and deamination (NQ) as variable modifications. In addition, each peptide was searched for a maximum of 6 variable modifications, a maximum of 200 modification combinations, and the searches were set to include peptides with >= 7 residues, <= 4600 Da, and unspecific searches required a peptide length between 8 and 25 residues. Co-fragmented peptides from a MS/MS spectrum were identified and quantified. Missing patterns of incomplete isotope pattern SILAC labeled pairs were requantified, based on the identified isotope pattern. The “Match between runs’ algorithm was used to identify peptide features with a missing MS/MS spectrum or peptide sequence from another run, based on identified m/z and RT information. For the protein-level analysis, protein group identification required >=1 razor/unique peptide, and protein group quantification required at least 2 quantified peptide feature ratios between SILAC pairs. Protein ratio calculations included both razor and unique peptides, as well as unmodified peptides and peptides with oxidation (M) and acetyl (N-terminal) modifications; however, the unmodified counterparts/versions of these modified peptides were omitted from quantification. The protein group ratios were calculated using the “advanced ratio estimation” method, which reports the median of the peptide feature ratios or the result of a regression model for the intensities and log ratios if there is a correlation. Results from the peptide spectrum match (PSM), protein group and phospho-site analyses had reverse and contaminant sequences removed and were filtered based on a 1% false-discovery rate (FDR) that was calculated using the target-decoy strategy, in which decoy sequences were derived from reverse protein sequences. The PSM were also filtered based on the best spectrum match of a PSM (Andromeda score > 40), the difference between the Andromeda score of the best hit with that of the second best sequence hit (delta-score > 8), and the posterior error probability (PEP) of a false match (PEP < 0.01). The phospho-site level data were filtered as the PSM with the addition of a localization probability threshold for post-translational modifications (probability > 0.75). Protein groups were also filtered based on FDR (q value < 0.01).

Phosphorylation site motif analysis

Hypo- and hyper-phosphorylation site (hypo-PS and hyper-PS, respectively) motifs were identified by a motif discovery analysis performed using the Modification Motifs (MoMo) tool from the MEME software suite version 4.12.0 (Bailey et al., 2009). The motif discovery analysis used default settings with the Motif-X algorithm (Schwartz and Gygi, 2005) and included PS sequences, adjusted to a 15 residue width with the PS of interest at the center, and the background sequence database was the UniProt mouse proteome, which was used as the initial proteomics reference panel. The identified PS motifs were then compared to kinase phosphorylation motifs using the Tomtom motif comparison tool (Gupta et al., 2007) from the MEME software suite. The motif comparison analysis was performed using the default settings and kinase phosphorylation motif data from the PhosphoNetworks database (Hu et al., 2014a; Hu et al., 2014b; Newman et al., 2013).

Western blot

NTC and sgPrkar1a cells were cultured in regular media as above for 48 hours. Total protein samples from were collected and protease inhibitor cocktail was added to prevent degradation. Protein concentration was measured and then normalized by Bradford assay with BSA standard. Western was performed using a standard molecular biology protocols with antibodies detailed in Key Resources Table.

RNA-seq differential expression analysis

Strand-specific single-end RNA-seq read files were analyzed to obtain transcript level counts using Kallisto (Bray et al., 2016), with the settings --rf-stranded -b 100. Differential expression analysis between sg-NTC and sg-Prkar1a treated cells were then performed using Sleuth (Pimentel et al., 2017), with default settings.

Pathway enrichment analysis

For GSEA (Subramanian et al., 2005) we considered the entire set of genes in the differential expression analysis, and sorted the genes by their fold change values without regard to p-values. This ranked gene list was used for GSEA pre-ranked analysis, in reference to the C5-all pathway database. We considered a pathway as statistically significant if the q-value was less than 0.1. Using an adjusted p-value cutoff of 0.05, and a fold change threshold of ±1 (the “b” value from Sleuth output), we determined the set of transcripts that were significantly upregulated or downregulated with Prkar1a deletion. Converting these transcripts to the gene level, we then used the resultant gene sets for DAVID functional annotation analysis (Huang da et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2009), where we only considered GO categories. We considered a GO category as statistically significant if the Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value was less than 0.05.

ELISA

NTC and sgPrkar1a cells were cultured in regular media as above for 48 hours. Supernatant protein samples from were collected and protease inhibitor cocktail was added to prevent degradation. IL-6 ELISA was performed using a commercial kit (RnD).

TIL isolation for scRNA-seq

Cells were cultured and prepared for subcutaneous injection as above. Five million cells were injected into each mouse, and tumors was harvested for scRNA-seq experiments. Tumor tissue was immediately placed in PBS containing 2% FBS to maintain cell viability. Tumor tissue was then manually cut into small pieces using a razor in a 10cm dish containing 5ml PBS containing 2% FBS. Tumor tissue was then suspended into 15–20ml PBS and loaded into gentleMACs tubes. Collagenase IV was added in a 1:100 dilution to each sample, prior to loading into the gentleMACs tissue dissociation machine. Tissue was then dissociated for 30’ at 37 C. After dissociation samples were passed through a 100uM filter and re-suspended into 40mL of PBS. Samples were then spun down at 400g for 5 min, and supernatant was discarded. Cell pellets then were washed with 40mL PBS, and spun down again at 400g for 5 min and supernatant was discarded. 3mL ACK lysis buffer was added to each cell pellet, gently pipetting to mix, then incubated for 3–5 min. After incubation samples were re-suspended in 40mL PBS and passed through a 40uM filter to remove debris. Cells were then washed again, and stained with anti-CD45.2 antibody for 30’ using a 1:100 dilution (1e6 cells per mL). Prior to FACS, cells were washed 2x in PBS. Cells were then sorted based on CD45.2 (pan-immune cells) and GFP (cancer cells), and mixed as 90%:10% for single cell transcriptomics analysis. Unique molecular identifier (UMI) and single cell barcoded library preparation and sequencing was done using a slightly modified approach based on previously established methods (Gierahn et al., 2017; Macosko et al., 2015).

Pre-processing the single-cell RNA-seq data

Drop-seq (version 1.12) (Macosko et al., 2015) tools were used to preprocessing all Seq-Well (Gierahn et al., 2017) single-cell RNA-seq data unless stated otherwise. First the paired-end read fastq files were merged and converted to Bam files by Picard-FastqToSam (Picard version 2.9.0). From the Bam files, cellular and unique molecular identifier barcodes were extracted, and reads were filtered to exclude those with single-base quality scores below 10. The sequences were then trimmed to remove adapters and polyA tails, and the files were converted back to fastq format by Picard-SamToFastq. The sequences were then mapped by STAR aligner (version 2.5.3a) (Dobin et al., 2013) to the mm10 mouse reference genome, provided by the McCarroll lab (GEO dataset: GSE63472) (Macosko et al., 2015). The aligned data were sorted by Picard-SortSam, and the cell and UMI barcode metadata were attached using Picard-MergeBamAlignment. Gencode annotations were added to the aligned reads, and digital gene expression (DGE) files were prepared for the 1000 most frequently occurring cell barcodes. For data generated by Chromium Single-cell 3’ RNA-sequencing (10X Genomics), preprocessing was performed using the Cellranger software count-pipeline (10X Genomics), aligning to the mm10 mouse genome reference with default settings. The pre-processed 10X and DGE matrices were then imported using the Seurat package (Satija et al., 2015) for the R programming language (version 3.4.4), and the data were filtered to include genes detected in >5 cells, and cells with >200 detected genes and <5% mitochondrial genes. The data were then normalized to 10,000 transcripts/cell and log-transformed, using a pseudo-count of 1 (ln[x + 1]).

Filtering and visualization of scRNA-seq data

All single cell RNA-seq data analysis pipelines were performed using the Seurat package for R (Macosko et al., 2015) (Satija et al., 2015) (Butler et al., 2018). For single-dataset analyses of NTC-Rag1−/−, sgPrkar1a-Rag1−/−, sgPrkar1a-Nu/Nu and sgPrkar1a-C57BL/6 tumor micro-environments, variable genes were identified using the FindVariableGenes Seurat function, in which genes are split into 20 equal-width bins by mean expression, then filtered for those with high dispersion (>0.5 standard deviations from the average dispersion (log variance/mean ratio) within a bin) and high/low mean expression (>8 or <0.0125) (Satija et al., 2015). The variance in these variably expressed genes was then assessed by principal components analysis (PCA), and principal components were dimensionality reduced by t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) (van der Maaten and Hinton, 2008) via the Barnes-Hut approximation implementation (van der Maaten, 2014) or PHATE (Moon et al., 2017). Next, cell clustering was performed using shared nearest neighbor (SNN) algorithm (Waltman and van Eck, 2013). The t-SNE, PHATE and SNN techniques were each performed using the number of principal components that explains majority of the data variance, based on the “elbow” in plots of the partial variance described by each PC (Not shown). For the integrated analysis of sg-Prkar1a and sg-NTC-treated Rag1−/− cell samples, dimensionality reduction was performed using canonical correlation analysis (CCA). The correlation structure of the two datasets was then aligned using the dynamic time warping method, as described previously (Butler et al., 2018). The aligned, integrated data were visualized by t-SNE and clustered using SNN, as before.

Cluster analysis of scRNA-seq data

Cluster-specific marker genes were selected by differential expression analyses for each cluster, relative to all other clusters, using the Model-based Analysis of Single-cell Transcriptomics (MAST) (Finak et al., 2015) with the Surat R package (Satija et al., 2015), filtering the genes to include those with an adjusted-p < 0.01 and within the top absolute fold-change (95th percentile). The cluster-specific markers were then used to compare each cluster population with known immune cells from the Immunological Genome Project data (ImmGen version 1; GEO dataset: GSE15907) (Heng et al., 2008). More specifically, the marker expression was averaged among cluster/cell type, log-normalized (as described above), and compared between datasets by Kendall correlation analysis (fast approximation method by pcaPP R package), after which, the correlation coefficients from each comparison were scaled and visualized by heatmap (pheatmap R package). In addition, this correlation heatmap data were grouped by ImmGen (Heng et al., 2008) cell categories, and the specific cell types were arranged within these categories by unsupervised hierarchical clustering.