Abstract

Stress plays a role in tumourigenesis through catecholamines acting at β‐adrenoceptors including β1‐, β2‐ and β3‐adrenoceptors, and the use of β‐adrenoceptor antagonists seems to counteract tumour growth and progression. Preclinical evidence and meta‐analysis data demonstrate that melanoma shows a positive response to β‐adrenoceptor blockers and in particular to propranolol acting mainly at β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors. Although evidence suggesting that β3‐adrenoceptors may play a role as a therapeutic target in infantile haemangiomas has been recently reviewed, a comprehensive analysis of the data available from preclinical studies supporting a possible role of β3‐adrenoceptors in melanoma was not available. Here, we review data from the literature demonstrating that propranolol may be effective at counteracting melanoma growth, and we provide preclinical evidence that β3‐adrenoceptors may also play a role in the pathophysiology of melanoma, thus opening the door for further clinical assays trying to explore β3‐adrenoceptor blockers as novel alternatives for its treatment.

Linked Articles

This article is part of a themed section on Adrenoceptors—New Roles for Old Players. To view the other articles in this section visit http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bph.v176.14/issuetoc

Abbreviations

- Ad

adrenaline

- Gs

stimulatory G protein

- NA

noradrenaline

Introduction

Melanoma is the most aggressive type of skin cancer. Excluding familiar forms, the main risk factor for melanoma development is represented by UV radiations. An increasing incidence of melanoma has been found, especially in young adults. In fact, consistent with epidemiological data, more than 130 000 new cases of melanoma and about 50 000 melanoma‐related deaths are diagnosed worldwide each year (Geller et al., 2013) with a continuous and dramatic increase in incidence during the last decades in Europe and in the USA (Apalla et al., 2017). While melanoma has been a major unmet medical need for many years, recently, there has been major progress thanks to the introduction of novel approaches, thus paving the way to new therapies for this aggressive form of cancer (Luke et al., 2017). In this respect, increasing knowledge of the signalling pathways that play a role in melanoma growth has been of central importance to identify novel therapeutic targets. In melanoma patients, for instance, the identification of BRAF mutations leading to overactivation of the MAPK pathway has opened the door to therapies targeting this pathway (Lim et al., 2017). Additional targeted therapies have been introduced against the kinase MEK, a member of the MAPK family, which is frequently co‐activated with BRAF in melanoma patients (Ryu et al., 2017). More recently, targeting the immune system with the use of checkpoint inhibitors is emerging as an elective option for melanoma treatment (Schadendorf et al., 2018). However, after the initial results associated with targeted therapies, tumour resistance or relapse of the melanoma lesion has been observed (Mattia et al., 2018) suggesting the need for additional therapies to treat melanoma.

In the search for possible novel targets to be used in treatment strategies to counteract melanoma growth, particular attention has been paid to catecholamines released by both the sympathetic nervous system [noradrenaline (NA)] and the adrenal gland [mainly adrenaline (Ad), and, to a lesser extent, NA], which are known to drive cancer progression and to reduce the survival in patients suffering from several types of cancer (Tang et al., 2013). Biological effects of catecholamines in tumour cells have been mainly associated with β‐adrenoceptors, a family composed of three members acting through downstream pathways that are in part distinct and in part overlapped (Cole and Sood, 2012; Tang et al., 2013). The presence of this family was proposed in 1948 (Ahlquist, 1948) and definitively demonstrated some years later (Powell and Slater, 1958). The existence of at least two members in this family was discovered in 1967 by comparing rank orders of potency of Ad and NA on fatty acid mobilization, cardiac activity, bronchodilation and vasorelaxation: the dominant receptor in adipose tissue/heart, identified as β1‐adrenoceptor, was equally sensitive to Ad and NA, while the dominant receptor in bronchi/vessels, identified as β2‐adrenoceptor, was much less sensitive to NA than to Ad (Lands et al., 1967). Twenty years later, with the development of pharmacological tools targeting these receptors as well as new techniques for studying drug–receptor interactions, the existence of a third β‐adrenoceptor subtype became apparent (Arch et al., 1984), and its presence was formally accepted at the end of the 1980s, when β3‐adrenoceptors were cloned and characterized in humans (Emorine et al., 1989). In 1994, the IUPHAR, in its adrenoceptor classification, recognized the presence of β3‐adrenoceptors as an additional member of the β‐adrenoceptor family (Bylund et al., 1994).

The three β‐adrenoceptors are widely expressed in different tumours, such as those of the brain, lung, liver, kidney, adrenal gland, breast, ovary, prostate, skin or lymphoid tissues (Sood et al., 2006; Perrone et al., 2008; Sloan et al., 2010; Moretti et al., 2013; Calvani et al., 2015), suggesting that these receptors may be regarded as possible targets for therapeutic interventions.

Among the tumours, there is increasing evidence that melanoma shows a surprisingly positive response to β‐adrenoceptor blockers targeting β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors. Among them, the most used blocker is propranolol, which is reported to have K i values at human β1‐, β2‐ and β3‐adrenoceptors of 1.8, 0.8 and 186 nM, respectively (Hoffmann et al., 2004; Vrydag and Michel, 2007), indicating a very much lower affinity for β3‐adrenoceptors than for β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors. Propranolol was introduced in the 1960s and originally used to treat angina pectoris (O'Rourke, 2007). Lately, it has been used in the treatment of different diseases, including myocardial infarction, hypertension and anxiety disorders, and propranolol is presently the gold standard in the treatment of infantile haemangiomas (Admani et al., 2014).

In melanoma cells, propranolol prevents the NA‐induced cell proliferation, likely through the activation of apoptotic processes (Dal Monte et al., 2013a; Moretti et al., 2013; Calvani et al., 2015; Wrobel and Le Gal, 2015; Zhou et al., 2016). In mouse models of melanoma, propranolol delays primary tumour growth and metastasis development, thus reducing melanoma progression and improving the survival rate (Hasegawa and Saiki, 2002; Glasner et al., 2010; Barbieri et al., 2012; Wrobel and Le Gal, 2015; Wrobel et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2016; Kuang et al., 2017; Maccari et al., 2017). In humans, a meta‐analysis of observational studies has suggested the possibility that β‐adrenoceptor blockers may provide new therapeutic options for the control of melanoma progression (De Giorgi et al., 2011). Thereafter, a significant reduction of the risk of melanoma progression has been reported for melanoma patients treated with β‐adrenoceptor blockers commonly used against cardiovascular diseases and hypertension (Lemeshow et al., 2011; De Giorgi et al., 2012; De Giorgi et al., 2013; De Giorgi et al., 2017; De Giorgi et al., 2018). Although some of these studies have been questioned (Livingstone et al., 2013; McCourt et al., 2014), De Giorgi et al. suggest potential benefits from targeting the β‐adrenoceptor pathway in melanoma patients. In this respect, a pro‐tumourigenic role for β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors in melanoma seems to be well delineated, and some clinical trials with propranolol in melanoma patients have been approved and are presently ongoing. Of them, a trial submitted in February 2016 aims at evaluating the effect of 80 mg·day−1 propranolol on overall survival of melanoma patients at 5 years of follow‐up. This study, which estimates to enrol 546 patients, is presently ongoing and is awaiting completion in 2022 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02962947). An additional trial, submitted in December 2017 and enrolling 47 patients with melanoma that cannot be removed by surgery, aims to evaluate the side effects and best dose of propranolol when given together with pembrolizumab, a monoclonal antibody authorized to treat melanoma. This trial is presently in the recruiting phase and is awaiting completion in 2020 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03384836).

So far, the role of β3‐adrenoceptors in melanoma has been poorly studied, although some preclinical data demonstrate that these receptors may participate in melanoma progression suggesting that blocking β3‐adrenoceptors may be a relevant treatment for melanoma (Dal Monte et al., 2013a; Dal Monte et al., 2014; Calvani et al., 2015; Sereni et al., 2015). However, the limited understanding of β3‐adrenoceptor function and the poor pharmacological profile of the β3‐adrenoceptor blockers currently available have hampered the development of clinical studies, thus making it difficult to extrapolate results from preclinical studies to humans. There are at least three reasons why these receptors have been, in general, poorly investigated (Cernecka et al., 2014). The first is that, in respect to the broad distribution of β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors, β3‐adrenoceptor expression profile is more restricted (Cernecka et al., 2014). The second is that β3‐adrenoceptors have a distinct regulation profile that differs from that of β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors. For instance, many of the β‐adrenoceptor ligands may be defined as β3‐adrenoceptor‐sparing ligands, since they bind β3‐adrenoceptors with a much lower affinity than that for β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors (Hoffmann et al., 2004; Cernecka et al., 2014). In addition, many β3‐adrenoceptor ligands show significant species‐specific differences in their affinity (Cernecka et al., 2014). For instance, the β3‐adrenoceptor agonist BRL37344 shows affinity differences of at least 10‐fold between rats and humans (Liggett, 1992). The third is that β3‐adrenoceptor ligands pose some problems of specificity as many of the ligands introduced as β3‐adrenoceptor‐selective can also bind to other β‐adrenoceptor subtypes and may also act on receptors different from β‐adrenoceptors (Vrydag and Michel, 2007). For example, at high concentration BRL37344 acts as a blocker of muscarinic receptors (Kubota et al., 2002; Matsubara et al., 2002).

In the present review, after summarizing our knowledge about the role of β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors in cancer, we will focus on studies demonstrating the role of these receptors in melanoma. Additionally, we will review preclinical studies supporting the involvement of β3‐adrenoceptors in melanoma biology, thus indicating that their role needs to be investigated further as they may represent a possible target for novel therapeutic approaches aimed at counteracting melanoma growth.

Stress and β‐adrenoceptor‐mediated tumour progression

Stress is commonly defined as the general reaction of the organism in response to endogenous and exogenous stimuli. The stress responses play a central role in the mechanisms of adaptation to environmental changes (Cameron and Schoenfeld, 2018). One of the main systems involved in these mechanisms is the sympathetic‐adrenal medullary system that releases catecholamines whose effects are mediated through interactions with α‐ and β‐adrenoceptors (Kirstein and Insel, 2004; Ahles and Engelhardt, 2014).

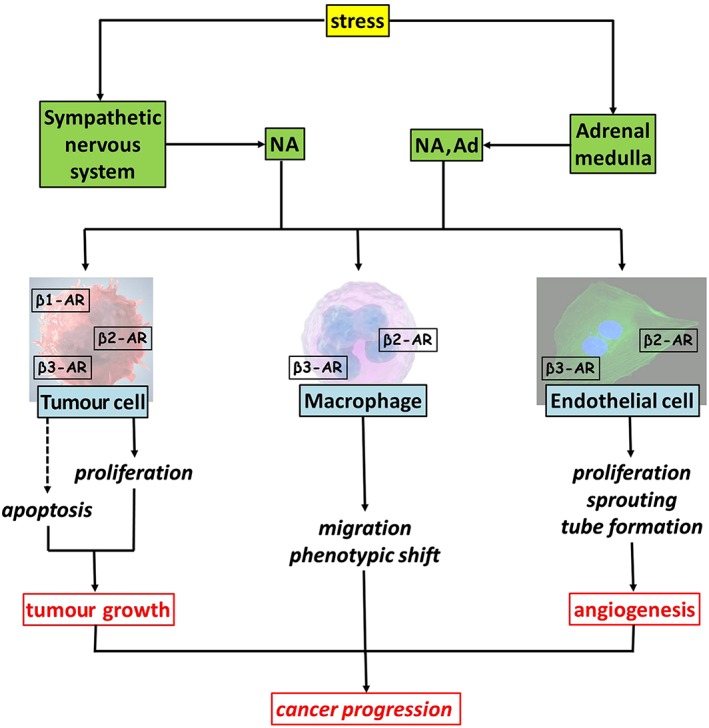

Over the past 25 years, epidemiological and clinical studies have linked psychological factors such as stress, chronic depression and lack of social support to the incidence and progression of cancer. In this respect, there is a growing interest on the relationship between stress and tumour progression, and several findings point to β‐adrenoceptors as a key regulator of important biological processes involved in the onset and progression of some solid tumours. In particular, the sympathetic nervous system and catecholamines have been shown to regulate multiple cellular processes that contribute to the initiation and progression of cancer including tumour cell growth and migration as well as angiogenic processes (Tang et al., 2013). In particular, catecholamines, in addition to promoting tumour growth by directly acting on tumour cells, can regulate the activity of cells of the tumour micro‐environment (Cole et al., 2015). For example, NA recruits and stimulates endothelial cells to proliferate and form tube‐like structures (Tilan and Kitlinska, 2010; Madden et al., 2011; Jiang et al., 2014; Calvani et al., 2015; Pan et al., 2015), thus paving the way to tumour progression and metastatization. In addition, catecholamines promote the polarization of macrophages in the tumour micro‐environment toward the tumour permissive M2 phenotype (Qin et al., 2015). A schematic representation of the influence of catecholamines on tumour growth and cancer progression is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Stress‐induced release of catecholamines from the sympathetic nervous system and the adrenal medulla acts on tumour cells by driving their proliferation and inhibiting apoptotic cell death, thus sustaining tumour growth. Catecholamines may also recruit macrophages into the tumour mass likely through β2‐ and/or β3‐adrenoceptors and induce M2 pro‐tumourigenic phenotype presumably through β2‐adrenoceptors. Catecholamines additionally act on endothelial cells to stimulate angiogenic processes possibly through β2‐ and/or β3‐adrenoceptors. β1‐AR, β1‐adrenoceptor; β2‐AR, β2‐adrenoceptor; β3‐AR, β3‐adrenoceptor.

The first evidence for the role of β‐adrenoceptors in tumour growth comes from the study of Schuller and Cole (1989); they demonstrated that the non‐selective β‐adrenoceptor agonist isoprenaline induces the proliferation of lung adenocarcinoma cells, while propranolol counteracts the effect of β‐adrenoceptor stimulation. Next, the permissive role of β‐adrenoceptors in tumour growth was demonstrated in different types of cancer, including pancreas, breast, ovary, colorectum, oesophagus, stomach, lung, prostate, nasopharynx, melanoma, leukaemia, haemangiomas and angiosarcoma (Tang et al., 2013). In particular, there is growing evidence from experimental models and perspective studies that the use of β‐adrenoceptor blockers may be effective at reducing cancer growth and progression. For example, in mouse models of neuroblastoma, β‐adrenoceptor blockers, either non‐selective or selective, have been demonstrated to increase the response to chemotherapy (Pasquier et al., 2013). In addition, in a mouse model of ovarian carcinoma, chronic stress induces an increase in NA associated with a β2‐adrenoceptor‐mediated growth of carcinoma cells, an effect that is abolished by propranolol (Thaker et al., 2006). Moreover, in a mouse model of prostate cancer in which surgical stress favours tumour growth, selective β2‐adrenoceptor blockade prevents the effect of stress (Hassan et al., 2013). Finally, propranolol prevents tumour formation in a mouse model of lung cancer (Min et al., 2016) while suppressing proliferation and promoting apoptosis in haemangioma cells, an effect that is mirrored by selective blockade of β2‐, but not of β1‐adrenoceptors (Munabi et al., 2016). Overall, data from the literature point to β2‐adrenoceptors as having a major role in mediating the pro‐tumourigenic effects of stress. This role that has been confirmed in β2‐adrenoceptor knockout mice, in which the loss of β2‐adrenoceptors counteracts tumour progression in a model of prostate cancer (Zahalka et al., 2017), and in pancreatic cancer cell lines, in which selective β2‐adrenoceptor blockade is more effective at suppressing cell invasion and proliferation in comparison to selective β1‐adrenoceptor blockade (Zhang et al., 2010).

Meta‐analysis of observational studies including patients with different types of cancer and independently treated with β‐adrenoceptor blockers for concomitant diseases has demonstrated beneficial effects on tumour progression. For example, β‐adrenoceptor blockers ameliorate tumour progression, confer a survival advantage in patients with metastatic brain tumours and decrease tumour proliferation in patients suffering from early stage breast cancer (Bir et al., 2015; Montoya et al., 2017). In addition, the therapeutic use of propranolol seems to be effective at managing infantile haemangiomas, and propranolol has recently replaced the previous gold standard corticosteroids as the treatment of choice for these tumours (Admani et al., 2014).

In addition to directly acting on tumour cells, β‐adrenoceptors play a major role in mediating the intimate crosstalk between tumour cells and their environment that has a profound influence on tumour growth and progression (Finotello and Eduati, 2018). In this respect, it has been demonstrated that propranolol counteracts the stress‐induced formation of new blood vessels in a mouse model of colorectal carcinoma and that the deletion of the gene encoding for β2‐adrenoceptors leads to inhibition of angiogenesis in a mouse model of prostate cancer (Liu et al., 2015; Zahalka et al., 2017). In addition, propranolol prevents both macrophage recruitment into the tumour mass in a model of ovarian carcinoma and macrophage M2 polarization in a model of breast cancer (Armaiz‐Pena et al., 2015; Qin et al., 2015).

Overall, these data provide a strong rationale for the clinical evaluation of β‐adrenoceptor blockers acting at β1‐ or β2‐adrenoceptors, alone or in association with additional treatments, but less information is available as regards a possible tumourigenic role for β3‐adrenoceptors. β3‐Adrenoceptors are expressed in human melanoma, astrocytoma and leukaemia cells (Lamkin et al., 2012; Calvani et al., 2015; Yoshioka et al., 2016) as well as in mouse melanoma cells (Dal Monte et al., 2013a). In addition, in humans, β3‐adrenoceptors are overexpressed in colon and breast cancer (Perrone et al., 2008; Montoya et al., 2017), and a strong expression of β3‐adrenoceptors has been found in infantile haemangiomas and vascular lesions (Chisholm et al., 2012; Phillips et al., 2017). There is also pharmacological evidence that β3‐adrenoceptors are expressed in human ovarian and endometrial cancer (Modzelewska et al., 2017). In addition, β3‐adrenoceptor polymorphism has been associated with susceptibility to endometrial and breast cancer (Huang et al., 2001; Babol et al., 2004).

β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors in melanoma: preclinical data and meta‐analysis of observational studies

Among tumours, melanoma shows a surprisingly positive response to β‐adrenoceptor blockers that target β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors. In humans, these receptors are expressed in tissues from benign melanocytic naevi, atypical naevi and malignant melanomas, and their expression correlates well with tumour malignancy, thus supporting the hypothesis that circulating catecholamines, by activating β‐adrenoceptors, induce melanoma progression (Moretti et al., 2013). In addition, in human melanoma cells, NA may induce the expression of angiogenic factors including VEGF and some inflammatory cytokines thus indicating that catecholamines may influence tumour progression by regulating the production of factors involved in pathological angiogenesis and tumour metastatization (Yang et al., 2009; Moretti et al., 2013). Of note, the effect of NA on human melanoma cells can be prevented by β‐adrenoceptor blockade with propranolol, which can also counteract the NA‐induced cell proliferation, as demonstrated by using the B16F10 mouse melanoma cell line (Moretti et al., 2013; Dal Monte et al., 2013a; Calvani et al., 2015; Wrobel and Le Gal, 2015; Zhou et al., 2016). B16F10 cells are of particular interests in experimental studies on melanoma as they are poorly immunogenic, unable to generate an immune response in their syngeneic host, the C57BL/6 mouse (Wang et al., 1998). The effect of propranolol on mouse melanoma cells appears to involve the activation of apoptotic processes through the inhibition of different β‐adrenoceptor downstream effectors including PKB(Akt), STAT3 and inducible (i)NOS (NOS2) (Dal Monte et al., 2013a). However, in human malignant melanoma, propranolol also acts in synergy with sunitinib, a multi‐target TK inhibitor, inhibiting cell proliferation through the induction of cell cycle arrest rather than by inducing cell death (Kuang et al., 2017). Propranolol, in addition to inhibit melanoma cell proliferation in vitro, also reduces melanoma progression in vivo. In fact, in mice bearing B16F10 cells, propranolol attenuates tumour growth (Hasegawa and Saiki, 2002; Barbieri et al., 2012) and, when administered in combination with a COX inhibitor, but not alone, improves the survival rate (Glasner et al., 2010). Of note, in B16F10 cell‐bearing mice, propranolol seems to exert anti‐proliferative effects on cancer cells at concentrations up to 20 mg·kg−1, whereas higher doses are less effective indicating that the dose of propranolol administered is a critical parameter to obtain an optimal inhibition of melanoma growth (Maccari et al., 2017). Conflicting results from different studies concur to demonstrate that the effect of propranolol in reducing melanoma progression in mouse xenografts bearing human melanoma cells is dependent on the specific cell type and the experimental conditions (Wrobel and Le Gal, 2015; Zhou et al., 2016; Kuang et al., 2017). Finally, in a murine spontaneous model of melanoma, propranolol delays primary tumour growth and metastasis development by decreasing the infiltration of immunosuppressive cells in the tumour micro‐environment (Wrobel et al., 2016).

In humans, a meta‐analysis of observational studies performed in 121 melanoma patients suffering from malignant thick melanoma has shown that in 30 of them, the use of β‐adrenoceptor blockers for concomitant diseases for 1 or more years is associated with a reduced risk of melanoma progression (De Giorgi et al., 2011). A second study, performed in a larger cohort of patients and with a longer follow‐up, has confirmed the beneficial effects of β‐adrenoceptor blockers, demonstrating that patients with thick malignant melanoma show an increased survival time when treated with β‐adrenoceptor blockers (Lemeshow et al., 2011). However, these studies have been questioned by the finding that in other cohorts of patients, the use of β‐adrenoceptor blockers does not correlate with a reduced risk of death (Livingstone et al., 2013; McCourt et al., 2014). Nevertheless, recent findings by De Giorgi et al. (2017), who extended the follow‐up of the cohort of patients studied in 2011 to 8 years, have confirmed that the use of β‐adrenoceptor blockers significantly reduces the risk of recurrence and mortality. Finally, a prospective study in cutaneous melanoma patients with no evidence of metastasis and using propranolol daily as an off‐label adjuvant treatment has recently confirmed that β‐adrenoceptor blockade protects patients with thick cutaneous melanoma from disease recurrence (De Giorgi et al., 2018). Overall, preclinical data clearly indicate that β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors have a pro‐tumourigenic role in melanoma, although no therapies using β1‐ or β2‐adrenoceptor blockers to treat this type of cancer have been presently approved.

β3‐Adrenoceptors: pharmacology and function

β3‐Adrenoceptors have the classical structure of a GPCR, with seven transmembrane domains joined by three extracellular and three intracellular loops. Among the different β‐adrenoceptor subtypes, the C‐terminus is the region with the lowest homology, with β3‐adrenoceptors lacking the phosphorylation sites implied in agonist‐induced desensitization that are, on the contrary, a feature of β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors (Dessy and Balligand, 2010). In this respect, β3‐adrenoceptors transfected into CHO cells show a lack of desensitization, suggesting that the absence of phosphorylation sites in the C‐terminus actually causes the β3‐adrenoceptors to be resistant to agonist‐induced desensitization (Cernecka et al., 2014). To date, the crystal structure of β3‐adrenoceptors is not available, and therapeutic drugs specifically targeting β3‐adrenoceptors have only recently been approved to treat overactive urinary bladder syndrome (Michel and Korstanje, 2016).

So far, studies on the roles of β3‐adrenoceptors in physiology and pathology have been hampered by the lack of highly specific tools. In particular, several results demonstrate that, at least for the human β3‐adrenoceptors, the affinity of the widely used antagonist SR59230A is in the same range or even lower than for β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors. A second issue is related to the fact that SR59230A can act as a partial agonist, with the degree of partial agonism strongly depending on the model system. In addition, in some systems, SR59230A acts as a full agonist (Vrydag and Michel, 2007). An additional β3‐adrenoceptor antagonist, L‐748337, a drug belonging to a molecular class different from that of SR59230A, has been proposed as a valid alternative to selectively block β3‐adrenoceptors as in humans L‐748337 has been shown to have a much higher affinity for β3‐ than for β1‐ or β2‐adrenoceptors than SR59230A (Candelore et al., 1999). However, the affinity of L‐748337 for β3‐adrenoceptors is lower in rodents than in humans, and the drug binds to a low‐affinity site distinct from the catecholamine binding site of β3‐adrenoceptors. In addition, L‐748337 is a biased agonist more effective on p38 MAPK activation than on cAMP formation (Cernecka et al., 2014). The same type of problems exists for β3‐adrenoceptor agonists, among which the most widely used is BRL37344, which, however, is poorly selective and exerts part of its effects through β1‐ or β2‐adrenoceptors. In addition, at high concentrations, BRL37344 becomes an antagonist for muscarinic receptors (Kubota et al., 2002; Matsubara et al., 2002). A better specificity seems to be demonstrated by those β3‐adrenoceptor agonists that have entered clinical development, such as mirabegron, ritobegron and solabegron. Mirabegron seems to be more potent in humans than in rats, while ritobegron is more active in rats than in humans. In humans, solabegron appears to be more potent than mirabegron and ritobegron (Igawa and Michel, 2013).

Despite the limitations due to the variable specificity and selectivity of β3‐adrenoceptor ligands, the functional role of β3‐adrenoceptors has been ascertained in several organs and systems. Firstly, β3‐adrenoceptors have been shown to regulate lipolysis and thermogenesis in the brown adipose tissue (Sepa‐Kishi and Ceddia, 2018). Subsequently, the involvement of β3‐adrenoceptors in the pathophysiology of the cardiovascular system and the urinary tract has been demonstrated (Balligand, 2013; Igawa and Michel, 2013; Procino et al., 2016; Kaya et al., 2018). In addition, β3‐adrenoceptors play a physiological role in the control of several vascular functions, such as in the regulation of pathological angiogenesis in models of retinal vascular proliferation (Casini et al., 2014). In this respect, a recent review by Escarcega González et al. (2018) lists some lines of evidence suggesting that β3‐adrenoceptors may play a role in the pathophysiology of infantile haemangiomas thus representing a potential therapeutic target for its treatment. However, the limited pharmacological profile of the β3‐adrenoceptor acting drugs currently available (see below) has hindered the translation of preclinical data to clinical outcomes, thus representing a major limiting factor for suggesting the therapeutic importance of β3‐adrenoceptor blockers.

Role of β3‐adrenoceptors in melanoma

A recent study determining the expression of β‐adrenoceptors across 29 tumour types, representing the most common cancers affecting humans, has shown that β3‐adrenoceptors are expressed by all the cancers and most strongly in melanoma (Rains et al., 2017). This supports the notion that β3‐adrenoceptors may be viewed as a possible target for therapies aimed at counteracting tumour growth in general and melanoma growth in particular. This point of view is sustained by several experimental findings. For example, non‐selective β‐adrenoceptor antagonists reduce the viability of human breast cancer cells, whereas β1‐ or β2‐adrenoceptor selective antagonists, alone or in combination, are not as effective as non‐selective β‐adrenoceptor antagonists (Montoya et al., 2017). This suggests that the effects of these antagonists could be in part mediated by β3‐adrenoceptors. In addition, a study performed in mice with genetic deletion of β1‐adrenoceptors, β2‐adrenoceptors or both has suggested that β3‐adrenoceptors may have a role in the development of prostate cancer (Magnon et al., 2013). Moreover, a novel L‐748337 derivative, which specifically targets β3‐adrenoceptors, has been shown to be effective at reducing tumour growth in a mouse model of adenocarcinoma (Jin et al., 2018).

Evidence from in vitro studies

Investigation of the role of β3‐adrenoceptors in melanoma is based on the observation that B16F10 cells express not only β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors, as previously deduced by pharmacological studies (Barbieri et al., 2012), but also β3‐adrenoceptors, a finding confirming and expanding the notion that β‐adrenoceptors may play important roles in modulating melanoma biology (Dal Monte et al., 2013a). In addition, this study showed that the exposure of melanoma cells to hypoxia (a strategy used to mimic a feature of the melanoma micro‐environment in vivo) results in a significant increase in β3‐adrenoceptor expression that is paralleled by an increased expression of VEGF, which may be considered an adaptive response of melanoma cells to low oxygen tension mediated by β3‐adrenoceptors. In fact, the up‐regulation of VEGF was prevented by treating melanoma cells with either SR59230A or L‐748337, which seem to specifically target β3‐adrenoceptor‐induced increase in VEGF levels, an effect that is not replicated by propranolol. Both SR59230A and L‐748337 are also able to reduce cell proliferation not only in B16F10 cells stimulated with NA but also in untreated B16F10 cells, indicating that spontaneous β3‐adrenoceptor activity, either constitutive or elicited by autocrine factors, is sufficient to sustain melanoma cell proliferation. Additionally, β3‐adrenoceptors also seem to play a role in melanoma cell survival, as SR59230A and L‐748337 are both able to induce apoptosis of B16F10 cells. The additional evidence that the effects of SR59230A and L‐748337 are indeed mediated by β3‐adrenoceptors further strengthens the notion that these receptors play an important role in melanoma. In particular, selective siRNAs targeting β3‐adrenoceptors have been found to replicate the effects of SR59230A and L‐748337 on melanoma cell proliferation and survival, confirming that β3‐adrenoceptors play a role in modulating melanoma cell growth. In addition, in mouse melanoma cells, an evaluation of known β‐adrenoceptor downstream effectors demonstrates that SR59230A and L‐748337 are coupled to a reduced expression of iNOS (NOS‐2), a well‐known pathway downstream of β3‐adrenoceptors, without having any effect on downstream effectors coupled to β2‐adrenoceptors, thus suggesting that β3‐adrenoceptors are the main target of SR59230A and L‐748337.

The expression of β3‐adrenoceptors has been also demonstrated in A375 human melanoma cells in which stress conditions that mimic the melanoma micro‐environment in vivo result in an up‐regulation of β3‐adrenoceptors. In fact, hypoxia, glucose withdrawal or ischaemia are all conditions that lead to increased levels of β3‐adrenoceptors without influencing the expression of β2‐adrenoceptors, thus indicating a role for β3‐adrenoceptors in regulating the adaptive response of melanoma cells to stressors and suggesting that a growing melanoma relies on β3‐adrenoceptor activity to overcome the limitations of suboptimal micro‐environmental conditions (Calvani et al., 2015).

Evidence from human biopsies

The expression of β3‐adrenoceptors has been also assessed in human samples of common melanocytic nevi, atypical melanocytic nevi, in situ primary melanoma, superficial spreading melanoma, nodular melanoma and cutaneous and lymph‐nodal metastatic melanoma. In particular, β3‐adrenoceptors are overexpressed in melanoma, which display a clear correlation with malignancy as their expression is higher in malignant and advanced malignant lesions. In addition to melanoma cells, stromal, inflammatory and endothelial cells also show a strong β3‐adrenoceptor expression that positively correlates with melanoma malignancy suggesting that β3‐adrenoceptors may participate in the formation of a ‘reactive stroma’, which supports melanoma development (Calvani et al., 2015).

Evidence from in vivo studies

β3‐Adrenoceptors have been demonstrated to be critically involved in melanoma growth in C57BL/6 mice in which syngeneic B16F10 cells were implanted in the back. In fact, in this model, the administration of SR59230A or L‐748337 reduces tumour volume, tumour weight and tumour vascularization (Dal Monte et al., 2013a). In particular, decreased tumour growth is due to reduced cell proliferation and increased apoptosis of melanoma cells as a consequence of either direct activation of apoptotic processes or indirect decrease of tumour vascularization. Interestingly, the reduced tumour vascularization does not appear to be secondary to a decreased expression of pro‐angiogenic factors but seems to be caused by apoptotic processes at the level of the tumour vasculature, which are mediated by β3‐adrenoceptors expressed by endothelial cells (Dal Monte et al., 2013a).

The possible pro‐tumourigenic role of β3‐adrenoceptors has been confirmed by some findings obtained in a mouse model of melanoma in which syngeneic B16F10 cells have been inoculated in mice with β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptor gene deletion (β1/β2‐adrenoceptor knockout; Sereni et al., 2015). This model has contributed to reveal an important role for host β1‐ and/or β2‐adrenoceptors in regulating the levels of catecholamines and β3‐adrenoceptors in the tumour mass. In addition, inhibiting β3‐adrenoceptors with the β3‐adrenoceptor antagonist L‐748337 reduces tumour volume and weight by reducing cell proliferation and activating apoptotic processes, with tumour responsiveness to the antagonist being much higher when β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors have been deleted. This indicates that the effect of β3‐adrenoceptors on melanoma growth is sustained by the activity of β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors expressed by the host.

Overall, results in the mouse model of melanoma demonstrate that SR59230A and L‐748337 are effective at reducing melanoma growth, an effect mediated through a dual action directed to both tumour and endothelial cells, thus suggesting that β3‐adrenoceptor blockade may counteract melanoma growth through additional effects on the melanoma micro‐environment including melanoma vascularization.

Role of β3‐adrenoceptors in melanoma micro‐environment

Tumour progression is a multistep process controlled by the complex interactions between tumour cells and their adjacent micro‐environment, which strongly sustains tumour growth by releasing a variety of signals able to induce several processes, such as cell proliferation and the formation of new blood vessels that may lead to tumour metastatization (Icard et al., 2014). In this respect, melanoma is viewed as an excellent model in which to study the interactions between cancer cells and their micro‐environment (Leong et al., 2018).

Recent findings suggest that β3‐adrenoceptor signalling acts in the crosstalk between the stromal compartment and the tumour cells (Calvani et al., 2015). In fact, A375 melanoma cells that are exposed to conditioned medium derived from different activated stromal cells, including M2 macrophages, myofibroblasts and hypoxic endothelial cells, display up‐regulated levels of β3‐adrenoceptors, but not of β2‐adrenoceptors. This finding suggests that β3‐adrenoceptors are the main receptor responsible for instructing melanoma cells to respond to environmental cell signals including VEGF and inflammatory cytokines. In addition, β3‐adrenoceptors have been demonstrated to have a major role in enhancing the motility of melanoma‐associated cells in this study; the conditioned medium of NA‐treated A375 melanoma cells was able to induce the migration of macrophages, fibroblasts, monocytes and endothelial cells and this migration was prevented by SR59230A or β3‐adrenoceptor‐selective silencing but not by propranolol or β2‐adrenoceptor‐selective silencing. Moreover, NA‐treated human dermal fibroblasts co‐cultured with A375 cells have been shown to stimulate melanoma cell migration, an effect that is prevented by SR59230A but not by β2‐adrenoceptor blockade, suggesting that β3‐adrenoceptors play a major role in mediating the crosstalk between melanoma and stromal cells that may lead to the activation of angiogenic processes. Finally, an increase in the stem‐like markers of melanoma cells, which is prevented by SR59230A but not by β2‐adrenoceptor blockade, has been observed in A375 cells treated with the conditioned medium from NA‐treated human dermal fibroblasts, indicating that β3‐adrenoceptors are the main receptors involved in the acquisition of stem‐like traits in melanoma cells. Overall, these results from in vitro studies collectively suggest that β3‐adrenoceptors can affect melanoma malignancy by acting on both tumour and stromal cells, coordinating angiogenic responses, melanoma and stromal cell motility and the acquisition of a more aggressive phenotype in melanoma cells.

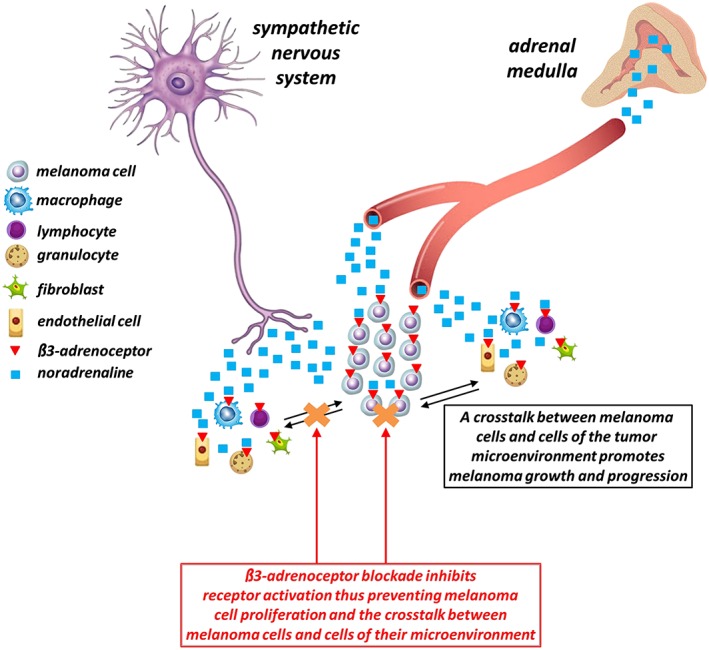

The key role of β3‐adrenoceptors in the interplay between melanoma cells and their micro‐environment has been recently confirmed using melanoma‐bearing β1/β2‐adrenoceptor knockout mice (Sereni et al., 2015). In this model, the increase in NA and β3‐adrenoceptors measured in the tumour mass is accompanied by increased tumour vascularity, suggesting that β3‐adrenoceptors may be overstimulated by NA thus acting as a pro‐angiogenic switch that increases the vascular response of the tumour, presumably through the recruitment of endothelial cells that subsequently assemble in newly formed blood vessels. This effect may be mediated by an increased production of pro‐angiogenic factors, including VEGF that is indeed up‐regulated in the tumours of β1/β2‐adrenoceptor knockout mice compared to the tumours of wild‐type mice. As demonstrated in this study, the deletion of β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors is also accompanied by reduced cell proliferation and increased cell apoptosis into the tumour mass, although tumour volume and weight are not significantly altered. This finding may be explained by assuming that NA overdrive increases the migration to the tumour site of β3‐adrenoceptor‐expressing host cells thus counteracting the decrease in melanoma volume, as would be expected following β1/β2‐adrenoceptor deletion. Overall, these data support the possibility that the increase in tumour vessels is an adaptive response of melanoma cells to an adverse micro‐environment, in which melanoma cells undergoing apoptosis stimulate vessel growth in an attempt to provide support for the tumour. The role of β3‐adrenoceptors in mediating the crosstalk between melanoma cells and their micro‐environment is represented schematically in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Noradrenaline released by the sympathetic nervous system and the adrenal medulla acts on both melanoma cells and cells of the tumour micro‐environment thus allowing a complex crosstalk that plays a central role in tumour growth and progression. β3‐Adrenoceptor blockade inhibits β3‐adrenoceptor activation thus preventing melanoma cell proliferation and the crosstalk between melanoma cells and stromal cells and finally counteracting melanoma growth.

β‐Adrenoceptor signalling in melanoma

Determining the specific intracellular pathways downstream β‐adrenoceptors represents a tough challenge and remains a prominent question regarding β‐adrenoceptor function in different organs. The three β‐adrenoceptor subtypes are coupled to stimulatory G proteins (Gs), and, in addition, β2‐ and β3‐adrenoceptors may also couple to inhibitory G proteins. In tumour cells, additional pathways may be activated by β‐adrenoceptors including the PI3K/Akt, the STAT3 and the MAPK pathways thus leading to tumour growth and metastatization (Coelho et al., 2017). β‐Adrenoceptor signalling depends not only on specific types of cancer cells but also on receptor–ligand interactions and the pharmacological profile of the ligand. In this respect, the pharmacological profile of β‐adrenoceptor ligands is complex. For example, β‐adrenoceptor blockers may act not only as antagonists on the G protein pathways but also as partial agonists or inverse agonists on additional pathways (Coelho et al., 2017). In this respect, propranolol is a biased agonist toward the Gs signalling pathway while is a partial agonists toward the MAPK pathway (Azzi et al., 2003), thus adding a new level of complexity in studies aimed at evaluating signalling pathways affected by β‐adrenoceptor blockers.

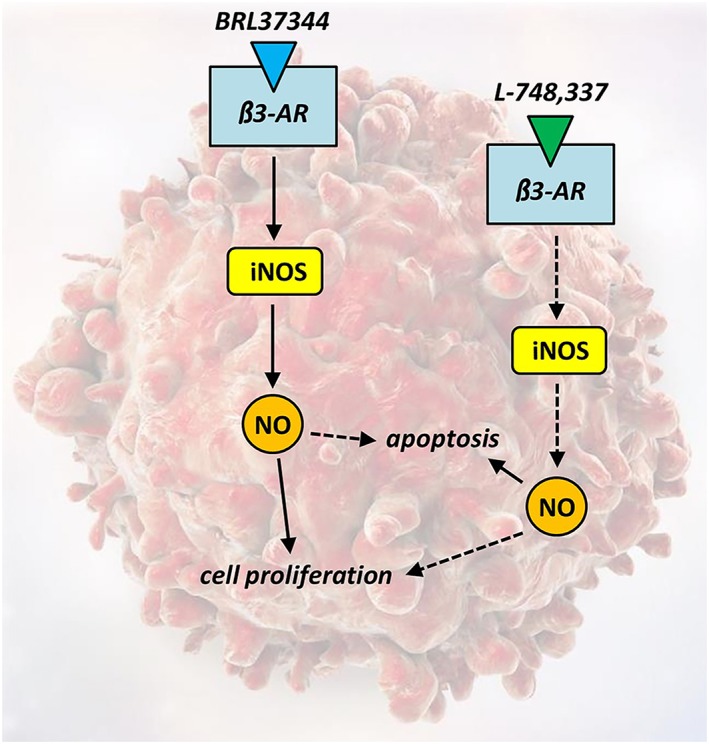

Among the signalling pathways involved in melanoma growth, NA acting on β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors activates the Gs/cAMP/PKA pathway thus leading to increased expression of VEGF and inflammatory cytokines (Yang et al., 2009; Deng et al., 2014). In addition, in human melanoma cells, propranolol has been found to inhibit the Akt and MAPK pathways thus promoting apoptosis and decreasing cell viability (Zhou et al., 2016). Moreover, in mouse melanoma cells, propranolol prevents the activation of different pathways including the activation of Akt, STAT3 and iNOS (Dal Monte et al., 2013a). Finally, in a mouse model of melanoma, stress‐induced β‐adrenoceptor activation promotes tumour growth by activating the endothelial NOS (eNOS/NOS‐3) pathway (Barbieri et al., 2012). Little is known about the signalling pathways downstream of β3‐adrenoceptors. In the failing heart, in particular, β3‐adrenoceptor activation leads to increased NO production, probably mediated by eNOS, followed by activation of PKG and the consequent PKG‐mediated myocyte relaxation, thus triggering a robust mechanism of cardioprotection, which is also accompanied by NO‐induced vasodilation of coronary arteries (Angelone et al., 2008; Balligand, 2016). Nevertheless, β3‐adrenoceptor‐induced NO production in the mouse retina in response to hypoxia results in aberrant vessel formation (Dal Monte et al., 2013b; Casini et al., 2014). The involvement of NO in the pro‐tumourigenic function of β3‐adrenoceptors has been demonstrated in B16F10 melanoma cells, in which β3‐adrenoceptor ligands influence iNOS expression and NO production (Dal Monte et al., 2014). These data, with the additional findings that the effects of β3‐adrenoceptor blockade are prevented by the NOS activator fluvastatin, while the effects of β3‐adrenoceptor activation are prevented by the NOS inhibitor L‐NAME, suggest that β3‐adrenoceptor activity is necessary to sustain NO production and demonstrate a functional link between β3‐adrenoceptor activity and NO signalling in melanoma cells. In addition, using selective activators/inhibitors of the three different NOS subtypes (neuronal NOS, iNOS and eNOS), it has been observed that selective iNOS activation prevents the effects of L‐748337, while iNOS inhibition counteracts the effects of β3‐adrenoceptor activation on iNOS and NO levels, with nNOS or eNOS selective activators/inhibitors having only minor effects (if any). These findings demonstrate that iNOS plays a central role in mediating β3‐adrenoceptor signals in B16F10 cells, although an involvement of nNOS or eNOS cannot be excluded. The additional demonstration that the effects of β3‐adrenoceptor ligands on melanoma cells can be prevented by pharmacological interaction with iNOS suggests that iNOS‐induced NO production downstream of β3‐adrenoceptor activation is a key event in melanoma survival and growth. Taken together, these findings point to the iNOS/NO pathway as the main effector linking β3‐adrenoceptors to their functional effects in mouse melanoma cells. A schematic diagram representing the effects of β3‐adrenoceptor activation or blockade on B16F10 cell proliferation and survival by modulating the iNOS/NO pathway is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

In melanoma cells, β3‐adrenoceptor activation with BRL37344 leads to an increase in iNOS expression and NO production thus resulting in cell proliferation and reduced apoptotic rate. On the contrary, β3‐adrenoceptor blockade with L‐748337 inhibits iNOS expression and NO production switching the balance between proliferation and apoptosis towards a reduction in proliferative processes and an increase in apoptotic cell death. β3‐AR, β3‐adrenoceptor.

Conclusions

Melanoma is the most aggressive skin cancer, and its progression depends on molecular alterations that select cells able to survive in an unfavourable micro‐environment. Until recently, therapeutic options to treat melanoma have been limited to surgical interventions and chemotherapies in the early stage of the disease, as metastatic melanomas are often refractory to commonly used anticancer drugs. However, during the last few years, treatments of melanoma have been improved thanks to a deeper knowledge of the signalling pathways involved in its pathogenesis and progression. Nonetheless, tumour resistance or relapse of the melanoma lesion has been observed, suggesting the need for additional therapies to be used alone or as add‐on therapies in treating melanoma. In this respect, targeting β‐adrenoceptors may be an effective way of counteracting melanoma growth, and the possibility of introducing drugs that block β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors in the management of melanoma patients is under active investigation. However, the incorporation of β3‐adrenoceptor blockers into the therapeutic armamentarium has far to go. Indeed, the currently available β3‐adrenoceptor blockers pose some problems of specificity, and the pattern of receptor expression as well as the ligand pharmacological profile may differ between rodents and humans. Hence, evidence from clinical studies is mandatory before it is decided whether β3‐adrenoceptors may be effectively regarded as an additional therapeutic target. Whether additional information on β‐adrenoceptor function in melanoma can be provided, the ideal antagonist perhaps is not a distinct β‐adrenoceptor antagonist but a true pan‐β‐adrenoceptor antagonist blocking all three subtypes with similar affinity. Nevertheless, off‐target effects of β‐adrenoceptor blockers cannot be excluded as β‐adrenoceptors are expressed by tissues that are not the intended targets in melanoma patients. In this respect, the fact that β3‐adrenoceptors have a rather restricted area of expression suggests a positive feature of the use of selective β3‐adrenoceptor blockers (when they become available and clinical evidence provided) for therapy, which would probably be associated with good tolerability. In addition, as innate resistance to anticancer treatments, including chemotherapy and targeted therapies, is a hallmark of cancers and in particular of melanoma, the fact that β3‐adrenoceptors are functionally active on stromal cells that are less like to develop resistance suggests that β3‐adrenoceptor blockers might avoid the troublesome resistance to therapy.

In conclusion, the finding that β3‐adrenoceptors play a role in the pathophysiology of melanoma may open up the door for further clinical assays trying to explore β3‐adrenoceptor blockers as novel alternatives for treating melanoma and other tumours. In this respect, accelerating the development of more selective pharmacological tools to be used in clinical studies is urgently required.

Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Harding et al., 2018), and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18 (Alexander et al., 2017a,b,c).

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Italian Ministry of Health (RF‐2011‐02351158 to P.B.; Rome, Italy). The authors thank Prof. Giovanni Casini (Department of Biology, University of Pisa) for his careful reading of the manuscript.

Dal Monte M., Calvani M., Cammalleri M., Favre C., Filippi L., and Bagnoli P. (2019) β‐Adrenoceptors as drug targets in melanoma: novel preclinical evidence for a role of β3‐adrenoceptors, British Journal of Pharmacology, 176, 2496–2508. doi: 10.1111/bph.14552.

Contributor Information

Massimo Dal Monte, Email: massimo.dalmonte@unipi.it.

Luca Filippi, Email: luca.filippi@meyer.it.

References

- Admani S, Feldstein S, Gonzalez EM, Friedlander SF (2014). Beta blockers: an innovation in the treatment of infantile hemangiomas. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 7: 37–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahles A, Engelhardt S (2014). Polymorphic variants of adrenoceptors: pharmacology, physiology, and role in disease. Pharmacol Rev 66: 598–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlquist RP (1948). A study of the adrenotropic receptors. Am J Physiol 153: 586–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SP, Christopoulos A, Davenport AP, Kelly E, Marrion NV, Peters JA et al (2017a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: G protein‐coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol 174: S17–S129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Fabbro D, Kelly E, Marrion NV, Peters JA, Faccenda E et al (2017b)). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 174: S272–S359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Kelly E, Marrion NV, Peters JA, Faccenda E, Harding SD et al (2017c)). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: Overview. Br J Pharmacol 174: S1–S16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelone T, Quintieri AM, Brar BK, Limchaiyawat PT, Tota B, Mahata SK et al (2008). The antihypertensive chromogranin a peptide catestatin acts as a novel endocrine/paracrine modulator of cardiac inotropism and lusitropism. Endocrinology 149: 4780–4793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apalla Z, Nashan D, Weller RB, Castellsagué X (2017). Skin cancer: epidemiology, disease burden, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and therapeutic approaches. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 7 (Suppl. 1): 5–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arch JR, Ainsworth AT, Cawthorne MA, Piercy V, Sennitt MV, Thody VE et al (1984). Atypical β‐adrenoceptor on brown adipocytes as target for anti‐obesity drugs. Nature 309: 163–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armaiz‐Pena GN, Gonzalez‐Villasana V, Nagaraja AS, Rodriguez‐Aguayo C, Sadaoui NC, Stone RL et al (2015). Adrenergic regulation of monocyte chemotactic protein 1 leads to enhanced macrophage recruitment and ovarian carcinoma growth. Oncotarget 6: 4266–4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzi M, Charest PG, Angers S, Rousseau G, Kohout T, Bouvier M et al (2003). β‐Arrestin‐mediated activation of MAPK by inverse agonists reveals distinct active conformations for G protein‐coupled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 11406–11411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babol K, Przybylowska K, Lukaszek M, Pertynski T, Blasiak J (2004). An association between the Trp64Arg polymorphism in the beta3‐adrenergic receptor gene and endometrial cancer and obesity. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 23: 669–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balligand JL (2013). Beta3‐adrenoreceptors in cardiovasular diseases: new roles for an “old” receptor. Curr Drug Deliv 10: 64–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balligand JL (2016). β‐Adrenergic receptors cooperate with transcription factors: the “STAT” of their union. Circulation 133: 4–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri A, Palma G, Rosati A, Giudice A, Falco A, Petrillo A et al (2012). Role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in chronic stress‐promoted tumour growth. J Cell Mol Med 16: 920–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bir SC, Kalakoti P, Ahmed O, Bollam P, Nanda A (2015). Elucidating the role of incidental use of beta‐blockers in patients with metastatic brain tumors in controlling tumor progression and survivability. Neurol India 63: 19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylund DB, Eikenberg DC, Hieble JP, Langer SZ, Lefkowitz RJ, Minneman KP et al (1994). International Union of Pharmacology nomenclature of adrenoceptors. Pharmacol Rev 46: 121–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvani M, Pelon F, Comito G, Taddei ML, Moretti S, Innocenti S et al (2015). Norepinephrine promotes tumor microenvironment reactivity through β3‐adrenoreceptors during melanoma progression. Oncotarget 6: 4615–4632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron HA, Schoenfeld TJ (2018). Behavioral and structural adaptations to stress. Front Neuroendocrinol 49: 106–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candelore MR, Deng L, Tota L, Guan XM, Amend A, Liu Y et al (1999). Potent and selective human β3‐adrenergic receptor antagonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 290: 649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casini G, Dal Monte M, Fornaciari I, Filippi L, Bagnoli P (2014). The β‐adrenergic system as a possible new target for pharmacologic treatment of neovascular retinal diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res 42: 103–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernecka H, Sand C, Michel MC (2014). The odd sibling: features of β3‐adrenoceptor pharmacology. Mol Pharmacol 86: 479–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm KM, Chang KW, Truong MT, Kwok S, West RB, Heerema‐McKenney AE (2012). β‐Adrenergic receptor expression in vascular tumors. Mod Pathol 25: 1446–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho M, Soares‐Silva C, Brandão D, Marino F, Cosentino M, Ribeiro L (2017). β‐Adrenergic modulation of cancer cell proliferation: available evidence and clinical perspectives. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 143: 275–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW, Nagaraja AS, Lutgendorf SK, Green PA, Sood AK (2015). Sympathetic nervous system regulation of the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer 15: 563–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW, Sood AK (2012). Molecular pathways: beta‐adrenergic signaling in cancer. Clin Cancer Res 18: 1201–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Monte M, Casini G, Filippi L, Nicchia GP, Svelto M, Bagnoli P (2013a). Functional involvement of β3‐adrenergic receptors in melanoma growth and vascularization. J Mol Med (Berl) 91: 1407–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Monte M, Filippi L, Bagnoli P (2013b). Beta3‐adrenergic receptors modulate vascular endothelial growth factor release in response to hypoxia through the nitric oxide pathway in mouse retinal explants. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 386: 269–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Monte M, Fornaciari I, Nicchia GP, Svelto M, Casini G, Bagnoli P (2014). β3‐adrenergic receptor activity modulates melanoma cell proliferation and survival through nitric oxide signaling. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 387: 533–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Giorgi V, Gandini S, Grazzini M, Benemei S, Marchionni N, Geppetti P (2013). Effect of β‐blockers and other antihypertensive drugs on the risk of melanoma recurrence and death. Mayo Clin Proc 88: 1196–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Benemei S, Marchionni N, Botteri E, Pennacchioli E et al (2018). Propranolol for off‐label treatment of patients with melanoma: results from a cohort study. JAMA Oncol 4: e172908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Benemei S, Marchionni N, Geppetti P, Gandini S (2017). β‐Blocker use and reduced disease progression in patients with thick melanoma: 8 years of follow‐up. Melanoma Res 27: 268–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Gandini S, Benemei S, Asbury CD, Marchionni N et al (2012). β‐adrenergic‐blocking drugs and melanoma: current state of the art. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 12: 1461–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Gandini S, Benemei S, Lotti T, Marchionni N et al (2011). Treatment with β‐blockers and reduced disease progression in patients with thick melanoma. Arch Intern Med 171: 779–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng GH, Liu J, Zhang J, Wang Y, Peng XC, Wei YQ et al (2014). Exogenous norepinephrine attenuates the efficacy of sunitinib in a mouse cancer model. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 33: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessy C, Balligand JL (2010). Beta3‐adrenergic receptors in cardiac and vascular tissues emerging concepts and therapeutic perspectives. Adv Pharmacol 59: 135–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emorine LJ, Marullo S, Briend‐Sutren MM, Patey G, Tate K, Delavier‐Klutchko C et al (1989). Molecular characterization of the human beta 3‐adrenergic receptor. Science 245: 1118–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escarcega González CE, González Hernández A, Villalón CM, Rodríguez MG, Marichal Cancino BA (2018). β‐Adrenoceptor blockade for infantile hemangioma therapy: do β3‐adrenoceptors play a role? J Vasc Res 55: 159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finotello F, Eduati F (2018). Multi‐omics profiling of the tumor microenvironment: paving the way to precision immuno‐oncology. Front Oncol 8: 430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller AC, Clapp RW, Sober AJ, Gonsalves L, Mueller L, Christiansen CL et al (2013). Melanoma epidemic: an analysis of six decades of data from the Connecticut Tumor Registry. J Clin Oncol 31: 4172–4178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasner A, Avraham R, Rosenne E, Benish M, Zmora O, Shemer S et al (2010). Improving survival rates in two models of spontaneous postoperative metastasis in mice by combined administration of a β‐adrenergic antagonist and a cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitor. J Immunol 184: 2449–2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding SD, Sharman JL, Faccenda E, Southan C, Pawson AJ, Ireland S et al (2018). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2018: updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY. Nucl Acids Res 46 (D1): D1091–D1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa H, Saiki I (2002). Psychosocial stress augments tumor development through β‐adrenergic activation in mice. Jpn J Cancer Res 93: 729–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan S, Karpova Y, Flores A, D'Agostino RJ, Kulik G (2013). Surgical stress delays prostate involution in mice. PLoS One 8: e78175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann C, Leitz MR, Oberdorf‐Maass S, Lohse MJ, Klotz KN (2004). Comparative pharmacology of human β‐adrenergic receptor subtypes – characterization of stably transfected receptors in CHO cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 369: 151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XE, Hamajima N, Saito T, Matsuo K, Mizutani M, Iwata H et al (2001). Possible association of β2‐ and β3‐adrenergic receptor gene polymorphisms with susceptibility to breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 3: 264–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Icard P, Kafara P, Steyaert JM, Schwartz L, Lincet H (2014). The metabolic cooperation between cells in solid cancer tumors. Biochim Biophys Acta 1846: 216–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igawa Y, Michel MC (2013). Pharmacological profile of β3‐adrenoceptor agonists in clinical development for the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 386: 177–183.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Ding S, Wu J, Liu X, Wu Z (2014). Norepinephrine stimulates mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells after limb ischemia. PLoS One 9: e101774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J, Miao C, Wang Z, Zhang W, Zhang X, Xie X et al (2018). Design and synthesis of aryloxypropanolamine as β3‐adrenergic receptor antagonist in cancer and lipolysis. Eur J Med Chem 150: 757–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya E, Sikka SC, Oral DY, Ozakca I, Gur S (2018). β3‐Adrenoceptor control of lower genitourinary tract organs and function in male: an overview. Curr Drug Targets 19: 602–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirstein SL, Insel PA (2004). Autonomic nervous system pharmacogenomics: a progress report. Pharmacol Rev 56: 31–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang X, Qi M, Peng C, Zhou C, Su J, Zeng W et al (2017). Propranolol enhanced the anti‐tumor effect of sunitinib by inhibiting proliferation and inducing G0/G1/S phase arrest in malignant melanoma. Oncotarget 9: 802–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota Y, Nakahara T, Yunoki M, Mitani A, Maruko T, Sakamoto K et al (2002). Inhibitory mechanism of BRL37344 on muscarinic receptor‐mediated contractions of the rat urinary bladder smooth muscle. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 366: 198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamkin DM, Sloan EK, Patel AJ, Chiang BS, Pimentel MA, Ma JC et al (2012). Chronic stress enhances progression of acute lymphoblastic leukemia via β‐adrenergic signaling. Brain Behav Immun 26: 635–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lands AM, Luduena FP, Buzzo HJ (1967). Differentiation of receptors responsive to isoproterenol. Life Sci 6: 2241–2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemeshow S, Sørensen HT, Phillips G, Yang EV, Antonsen S, Riis AH et al (2011). β‐Blockers and survival among Danish patients with malignant melanoma: a population‐based cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 20: 2273–2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong SP, Aktipis A, Maley C (2018). Cancer initiation and progression within the cancer microenvironment. Clin Exp Metastasis. 10.1007/s10585-018-9921-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liggett SB (1992). Functional properties of the rat and human β3‐adrenergic receptors: differential agonist activation of recombinant receptors in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol Pharmacol 42: 634–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SY, Menzies AM, Rizos H (2017). Mechanisms and strategies to overcome resistance to molecularly targeted therapy for melanoma. Cancer 123: 2118–2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Deng GH, Zhang J, Wang Y, Xia XY, Luo XM et al (2015). The effect of chronic stress on anti‐angiogenesis of sunitinib in colorectal cancer models. Psychoneuroendocrinology 52: 130–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone E, Hollestein LM, van Herk‐Sukel MP, van de Poll‐Franse L, Nijsten T, Schadendorf D et al (2013). β‐Blocker use and all‐cause mortality of melanoma patients: results from a population‐based Dutch cohort study. Eur J Cancer 49: 3863–3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke JJ, Flaherty KT, Ribas A, Long GV (2017). Targeted agents and immunotherapies: optimizing outcomes in melanoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 14: 463–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccari S, Buoncervello M, Rampin A, Spada M, Macchia D, Giordani L et al (2017). Biphasic effects of propranolol on tumour growth in B16F10 melanoma‐bearing mice. Br J Pharmacol 174: 139–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden KS, Szpunar MJ, Brown EB (2011). β‐Adrenergic receptors (β‐AR) regulate VEGF and IL‐6 production by divergent pathways in high β‐AR‐expressing breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res Treat 130: 747–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnon C, Hall SJ, Lin J, Xue X, Gerber L, Freedland SJ et al (2013). Autonomic nerve development contributes to prostate cancer progression. Science 341: 1236361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattia G, Puglisi R, Ascione B, Malorni W, Carè A, Matarrese P (2018). Cell death‐based treatments of melanoma: conventional treatments and new therapeutic strategies. Cell Death Dis 9: 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara S, Okada H, Shirakawa T, Gotoh A, Kuno T, Kamidono S (2002). Estrogen levels influence beta‐3‐adrenoceptor‐mediated relaxation of the female rat detrusor muscle. Urology 59: 621–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCourt C, Coleman HG, Murray LJ, Cantwell MM, Dolan O, Powe DG et al (2014). Beta‐blocker usage after malignant melanoma diagnosis and survival: a population‐based nested case‐control study. Br J Dermatol 170: 930–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel MC, Korstanje C (2016). β3‐Adrenoceptor agonists for overactive bladder syndrome: role of translational pharmacology in a repositioning clinical drug development project. Pharmacol Ther 159: 66–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min HY, Boo HJ, Lee HJ, Jang HJ, Yun HJ, Hwang SJ et al (2016). Smoking‐associated lung cancer prevention by blockade of the beta‐adrenergic receptor‐mediated insulin‐like growth factor receptor activation. Oncotarget 7: 70936–70947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modzelewska B, Jóźwik M, Jóźwik M, Sulkowski S, Pędzińska‐Betiuk A, Kleszczewski T et al (2017). Altered uterine contractility in response to β‐adrenoceptor agonists in ovarian cancer. J Physiol Sci 67: 711–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya A, Amaya CN, Belmont A, Diab N, Trevino R, Villanueva G et al (2017). Use of non‐selective β‐blockers is associated with decreased tumor proliferative indices in early stage breast cancer. Oncotarget 8: 6446–6460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti S, Massi D, Farini V, Baroni G, Parri M, Innocenti S et al (2013). β‐adrenoceptors are upregulated in human melanoma and their activation releases pro‐tumorigenic cytokines and metalloproteases in melanoma cell lines. Lab Invest 93: 279–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munabi NC, England RW, Edwards AK, Kitajewski AA, Tan QK, Weinstein A et al (2016). Propranolol targets hemangioma stem cells via cAMP and mitogen‐activated protein kinase regulation. Stem Cells Transl Med 5: 45–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke ST (2007). Antianginal actions of beta‐adrenoceptor antagonists. Am J Pharm Educ 71: 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan WK, Li P, Guo ZT, Huang Q, Gao Y (2015). Propranolol induces regression of hemangioma cells via the down‐regulation of the PI3K/Akt/eNOS/VEGF pathway. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62: 1414–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquier E, Street J, Pouchy C, Carre M, Gifford AJ, Murray J et al (2013). β‐Blockers increase response to chemotherapy via direct antitumour and anti‐angiogenic mechanisms in neuroblastoma. Br J Cancer 108: 2485–2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrone MG, Notarnicola M, Caruso MG, Tutino V, Scilimati A (2008). Upregulation of β3‐adrenergic receptor mRNA in human colon cancer: a preliminary study. Oncology 75: 224–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JD, Zhang H, Wei T, Richter GT (2017). Expression of β‐adrenergic receptor subtypes in proliferative, involuted, and propranolol‐responsive infantile hemangiomas. JAMA Facial Plast Surg 19: 102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell CE, Slater IH (1958). Blocking of inhibitory adrenergic receptors by a dichloro analogue of isoproterenol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 122: 480–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procino G, Carmosino M, Milano S, Dal Monte M, Schena G, Mastrodonato M et al (2016). β3 adrenergic receptor in the kidney may be a new player in sympathetic regulation of renal function. Kidney Int 90: 555–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin JF, Jin FJ, Li N, Guan HT, Lan L, Ni H et al (2015). Adrenergic receptor β2 activation by stress promotes breast cancer progression through macrophages M2 polarization in tumor microenvironment. BMB Rep 48: 295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rains SL, Amaya CN, Bryan BA (2017). Beta‐adrenergic receptors are expressed across diverse cancers. Oncoscience 4: 95–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu S, Youn C, Moon AR, Howland A, Armstrong CA, Song PI (2017). Therapeutic inhibitors against mutated BRAF and MEK for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Chonnam Med J 53: 173–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schadendorf D, van Akkooi ACJ, Berking C, Griewank KG, Gutzmer R, Hauschild A et al (2018). Melanoma. Lancet 392: 971–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuller HM, Cole B (1989). Regulation of cell proliferation by β‐adrenergic receptors in a human lung adenocarcinoma cell line. Carcinogenesis 10: 1753–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepa‐Kishi DM, Ceddia RB (2018). White and beige adipocytes: are they metabolically distinct? Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 33: 20180003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sereni F, Dal Monte M, Filippi L, Bagnoli P (2015). Role of host β1‐ and β2‐adrenergic receptors in a murine model of B16 melanoma: functional involvement of β3‐adrenergic receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 388: 1317–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan EK, Priceman SJ, Cox BF, Yu S, Pimentel MA, Tangkanangnukul V et al (2010). The sympathetic nervous system induces a metastatic switch in primary breast cancer. Cancer Res 70: 7042–7052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sood AK, Bhatty R, Kamat AA, Landen CN, Han L, Thaker PH et al (2006). Stress hormone‐mediated invasion of ovarian cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res 12: 369–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Li Z, Lu L, Cho CH (2013). β‐Adrenergic system, a backstage manipulator regulating tumour progression and drug target in cancer therapy. Semin Cancer Biol 23: 533–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaker PH, Han LY, Kamat AA, Arevalo JM, Takahashi R, Lu C et al (2006). Chronic stress promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis in a mouse model of ovarian carcinoma. Nat Med 12: 939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilan J, Kitlinska J (2010). Sympathetic neurotransmitters and tumor angiogenesis‐link between stress and cancer progression. J Oncol 2010: 539706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrydag W, Michel MC (2007). Tools to study β3‐adrenoceptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 374: 385–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Saffold S, Cao X, Krauss J, Chen W (1998). Eliciting T cell immunity against poorly immunogenic tumors by immunization with dendritic cell‐tumor fusion vaccines. J Immunol 161: 5516–5524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel LJ, Bod L, Lengagne R, Kato M, Prévost‐Blondel A, Le Gal FA (2016). Propranolol induces a favourable shift of anti‐tumor immunity in a murine spontaneous model of melanoma. Oncotarget 7: 77825–77837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel LJ, Le Gal FA (2015). Inhibition of human melanoma growth by a non‐cardioselective β‐blocker. J Invest Dermatol 135: 525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang EV, Kim SJ, Donovan EL, Chen M, Gross AC, Webster Marketon JI et al (2009). Norepinephrine upregulates VEGF, IL‐8, and IL‐6 expression in human melanoma tumor cell lines: implications for stress‐related enhancement of tumor progression. Brain Behav Immun 23: 267–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka Y, Kadoi H, Yamamuro A, Ishimaru Y, Maeda S (2016). Noradrenaline increases intracellular glutathione in human astrocytoma U‐251 MG cells by inducing glutamate‐cysteine ligase protein via β3‐adrenoceptor stimulation. Eur J Pharmacol 772: 51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahalka AH, Arnal‐Estapé A, Maryanovich M, Nakahara F, Cruz CD, Finley LWS et al (2017). Adrenergic nerves activate an angio‐metabolic switch in prostate cancer. Science 358: 321–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Ma QY, Hu HT, Zhang M (2010). β2‐Adrenergic antagonists suppress pancreatic cancer cell invasion by inhibiting CREB, NFκB and AP‐1. Cancer Biol Ther 10: 19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C, Chen X, Zeng W, Peng C, Huang G, Li X et al (2016). Propranolol induced G0/G1/S phase arrest and apoptosis in melanoma cells via AKT/MAPK pathway. Oncotarget 7: 68314–68327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]