Abstract

Objective

Improving access to effective and safe medicines is one of the major goals of all health systems. To achieve this goal, assessment is a fundamental phase of national medicine programs for access improvement. Collecting and compiling applicable indicators and impart a comprehensive framework for assessing access to medicine, are the aims of this study.

Methods

To investigate the published materials on access to medicines framework or indicators, a literature review with a systematic search was conducted using PubMed/ Medline, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases. The results were completed with a general search of documents in Iran Food and Drug Administration (IRFDA). Two independent researchers reviewed all the articles and documents. Thereafter the related indicators were extracted. In focused group discussion of academics and IRFDA experts, duplicate entries or ineffectual concepts were cleaned from the preliminary indicators. In the next step, Delphi questionnaire was sent to the 17 experts that work in academia, Social Security Insurance, IRFDA, Ministry of Health and Iran Pharmacist Association. The results of Delphi technique were finalized in an expert panel.

Results

One hundred and thirty one indicators were found in systematic search. After primary extraction of related indicators, 77 indicators were sent to the 17 experts in a Delphi form. The results of Delphi were finalized in a specialized-working group and 67 indicators were accepted in 5 categories including physical availability and geographical accessibility (19 indicators), affordability (23 indicators), human resources (4 indicators), quality and safety (5 indicators), information and rational use (16 indicators).

Conclusion

The indicators that inclusively assess the full access to medicine in the concept of rational use have been categorized into five categories in this study. To determine the access to medicine status in each country further local surveys are necessary for all several indicators in each category.

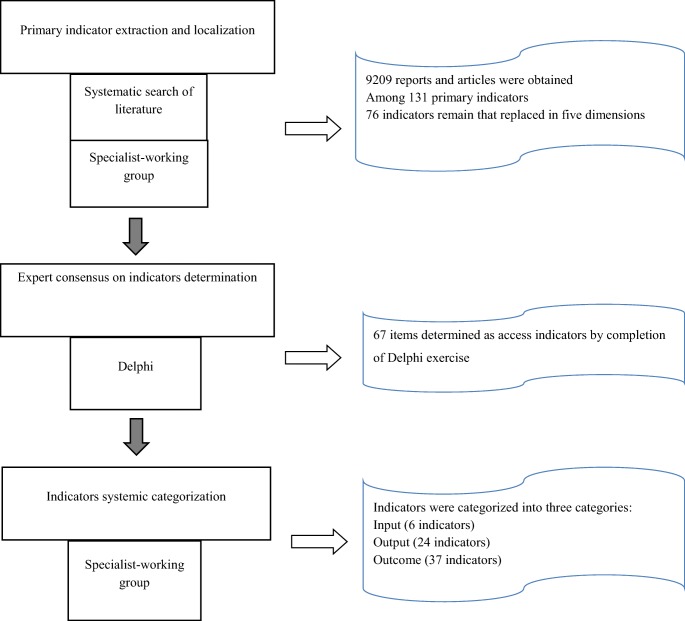

Graphical abstract.

The graphical abstract of accomplished steps

Keywords: Health services accessibility, Access to medicine, Accessibility, Availability, Pharmaceutical services, Health status indicators, “Health care quality, Access, and Evaluation”, Affordability, “Costs and cost analysis”, Health policy, National medicine program, Pharmaceutical policy

Introduction

Access to essential medicines is an irrefutable part of access to health and can influence the welfare of society. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), accessibility has three major objectives, including, physical accessibility, economic accessibility or affordability and information accessibility [1]. Physical accessibility refers to the availability and geographical accessibility of medicine for who need them for rational use. Affordability refers to the ability of people to pay for medicines without financial hardship and information accessibility includes the right to request, receive and impart information [1–4]. Most health systems have a mission to provide access to a sufficient quantity of safe, effective and high-quality medicines at an affordable price for the whole population [5]. Different countries follow different strategies in their National Medicine Policy (NMP) to achieve this mission. There is a need for systematic monitoring of the impact of country policies and activities on access and use of medicines. So, it is extremely important to have a consistent framework and comprehensive indices for assessing medicine accessibility at country. The World Health Organization has developed an Operational package for monitoring and assessing the pharmaceutical situation in countries in 2001 for the first time and has updated it in 2007 [6]. Afterward, some countries tried to assess their pharmaceutical sector using WHO or their own indicators. However, to our knowledge, there is no comprehensive framework for assessing access to medicine with a system approach. The authors believe that a system approach and attention to system component, including: input, output and outcome are very effective in monitoring and assessing. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to gather, evaluate and validation of the available indicators from scientific and governmental literature to provide an evidence-based framework for evaluating access to medicine in a system component level. The information gathered in this article can serve to guide researchers as well as policymakers to evaluate national medicine policy in a context of a country.

Methods

All study procedures were approved by the Iran National Institute of Health Research’ and National Institute for Medical Research Development’ Specialized Research Council.

Systematic search of literatures

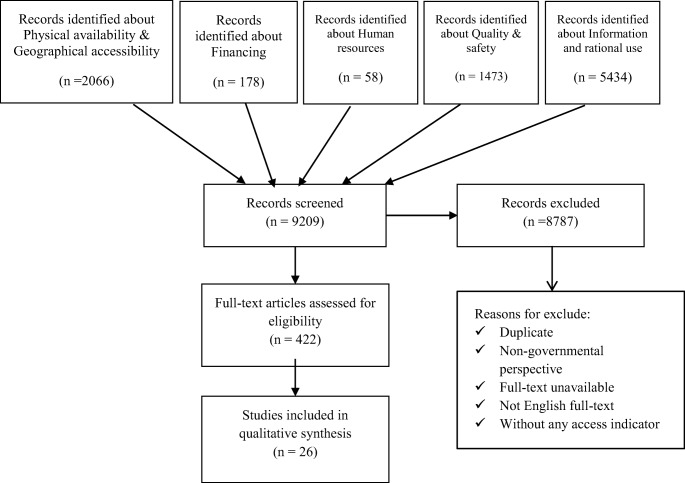

The following electronic databases including PubMed/ Medline, Scopus, and Google Scholar were searched. Additionally, a comprehensive search of government documents was done. Exclusive keywords were used to search for resources associated in five dimensions of access, including physical availability and geographical accessibility, affordability, human resources, quality and safety, and information and rational use. The search was conducted systematically in order to avoid losing any indicator of worldwide studies in this article. Electronic bibliographic databases have been searched for articles from First of January 2000 up to 17th November 2016. The keywords used were: access, assessment, analysis, measure, indicator, index, drug, medicine, medication, pharmaceutical, rational use, use, information, quality, safety, financial, cost, expenditure, geographic access, availability. Studies that used the governmental perspective and covered all five dimensions of access in their method were included. The restriction for language was Persian and English. All the articles and documents were reviewed by two researchers in terms of title, then abstract and eventually full text. Any occurred controversial decision has been conducted to consensus by a third researcher as a supervisor. Duplicated studies, studies that did not have full text or full text in English and Persian, as well as studies that not mentioned any indexes or used non-governmental perspective, were excluded. The main objective was to collect all possible indicators for assessing the access to medicine, which was suggested or used, by different countries. Hence, there was no need for quality assessment.

Indicators localization

In order to categorize and localize the indicators, a specialist-working group was established from the experts of Medical universities (Pharmacoeconomics and Pharmaceutical Administration Departments) and Iran Food and Drug Administration (IrFDA). Within 6 hours of teamwork, all the extracted indicators were reviewed and unnecessary or contradictory concepts were removed, modified or localized according to the country context.

Delphi procedure

A Delphi study has been run with all consideration for a comprehensive study [7]. Initially, 20 participants were invited to join the Delphi, which 17 of them have contributed to the study. Among them, one had not responded the questionnaire and thus response rate was 94.11%. The follow-up was carried out for someone who did not respond, but quitted Delphi. The experts comprised of specialists from the fields of health insurance, public health, rational use of medicine, pharmaceutical administration, and pharmacoeconomics with academic and executive backgrounds in the country’s pharmaceutical system. The characteristic information of the invited experts to participate has been shown in Table 1. Experts were deliberately chosen from among those who had national and international experience in insurance, regulatory organization, the health ministry, or academics, and had experience of working on the concepts of access to medicine and the health system. The geographic scope of the Delphi procedure was national. In the first unstructured round, a core group of authors drafted a set of revised indicators in the five dimensions of access to medicine and participated experts evaluated the indicators and recommendations via email or face-to-face interview. A questionnaire sent to experts, including elementary explanations for the study, cases to be considered and a table. Each indicator was specified in the table with the name and description in each row, and experts were asked to record their points. The face-to-face interview was conducted for 2 participants whom working with email was not convenient for them. The experts evaluated the importance of the indicators in dimension of a 10-point scale where 1 represented “lowest importance” and 10 represented “highest importance”. The median score equal or higher than 7 was considered as consensus threshold, where the median score between 5 and 7 was reviewed in the next round, and the median score equal or lower than 5 was eliminated. The Delphi was open for approximately 3 months and repeated two times to reach consensus. Despite the first round, the second run was directed at meeting. The decision was to change the form of Delphi due to problems that researchers had faced. The follow up by email and interview were time-consuming that might threaten the result of the study. The aim of the second run was to rescore first round median scores and reaching to a consensus.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of participants

| Gender | M | 6.50% |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Age | 52 | |

| Education | PhD | 100% |

| Employment | Academic with Executive experiences in IFDA | 44% |

| IFDA | 18.8% | |

| Ministry of Health | 12.5% | |

| Insurance | 25% | |

M Male, PhD Doctor of philosophy, IFDA Iran food and drug administration

Specialist-working group

With the purpose of systemic approach, several expert panels were conducted in the form of specialist working group. The panel was composed of academicians, monitoring and evaluation specialist, and IrFDA managers. Over three expert panels, the indicators were categorized into three fields of input, outputs, and outcomes. Then index, ancillary, a source of data, collection frequency and collection level were determined and confirmed by the experts.

Results

Primary indicator extraction and localization

A total of 9209 reports and articles were obtained from databases, WHO documents, and Food and Drug Administration of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Finally, a set of indicators of access to medicine was obtained. Figure 1 shows the summary of search results and Table 2 shows a total of primary 131 indicators in different dimensions. According to the specialist-working group, 76 indicators remained that replaced in five dimensions, including physical availability, geographical accessibility, financing, human resources, quality and safety, and information and rational use.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart of access to medicine indicators systematic search

Table 2.

Total access to medicine indicators extracted from literatures review

| Dimension | Indicator | Source of indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Physical availability & geographical accessibility | Existence and year of last update of a published national list of essential medicines [3, 8] | Gray literature |

| The availability of certain tracer drugs [9] | Systematic search | |

| Medicines not found in any outlets [8] | ||

| Medicines found in less than 25% of outlets [8] | ||

| Medicines found in 25 to 50% of outlets [8] | ||

| Medicines found in 50 to 75% of outlets [8] | ||

| Medicines found in over 75% of outlets [10] | Systematic search | |

| Mean percentages of availability of selected medicines by condition of morbidity and version of medicine, according to sector [11, 12] | Systematic search | |

| Drugs included in the WHO Model List | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| Availability of vaccines (EPI) | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| Availability of vaccines (none EPI) | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| Availability of key medicines in public health facility dispensaries, private drug outlets and warehouses supplying the public sector.(availability of essential medicines) [4] | Gray literature | |

| Essential medicines production as percentage of licenses held by manufacturers [13] | Systematic search | |

| Stock out duration at public health facility dispensaries and warehouses supplying the public sector [4] | Gray literature | |

| % of adequate record keeping at public health facility dispensaries and warehouses supplying the public sector [4] | Gray literature | |

| Number of medicines shortage in public hospitals | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| Number of facilities [14] | Systematic search | |

| Proportion of each pharmaceutical cadre by facility type and sector [8] | Gray literature | |

| Travel time to access healthcare [15] | Systematic search | |

| Distance to access healthcare [15–19] | Systematic search | |

| % medicines obtained in the public sector [20] | Systematic search | |

| % medicines obtained in the private sector [20] | Systematic search | |

| Percentage of municipalities covered [21] | Systematic search | |

| Pharmacy Facilities Density (number of pharmacies affiliated with the subsidized medicines-essential medicines- per 100,000 inhabitants) [21] | Systematic search | |

| %All prescribed medicines are available in any pharmacy | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| %Patient is forced to change his/her drug, but the alternative drug is available in any pharmacy | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| %Patient has to go to a specific public pharmacy to obtain his/her medicine/s | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| %The prescribed medicines are obtained with several visits to pharmacies | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| %Patient has to trip toa bigger city toobtainhis/her medicine/s | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| %patient has to trip toa bigger city and to a specific public pharmacy toobtainhis/her medicine/s | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| %Patient must trip to the capital city to take his/her medicine/s | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| %Patient has to take his/her medicine from black market | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| %The prescribed medicine is not available at all | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| Financing | Total pharmaceutical out-of-pocket expenditure [22] | Systematic search |

| Pharmaceutical out-of-pocket expenditure as % of total pharmaceutical expenditure(inpatients/outpatients) | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| Medicines’ inflation rate | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| % Obtained medicines for free [20] | Systematic search | |

| per patient drug expenditure (monthly drug costs divided by the number of patients dispensed drugs, i.e. costs per patient) [23] | Systematic search | |

| unit prices (monthly drug costs divided by the number of units dispensed, i.e. costs per unit) [23] | Systematic search | |

| co-payment for medicines per patient | ||

| Average spent on medicines in the last 4 weeks [24] | Systematic search | |

| % of people have to refuse dispensation of medicines due to co-payment [24] | Systematic search | |

| Were there any medicines prescribed or recommended for you in the last 30 days that you were not able to find or buy? [25] | Systematic search | |

| Affordability was measured as the number of days’ wages required for the lowest-paid unskilled government worker to purchase standard treatments for common conditions. [10, 26–28] | Systematic search | |

| Affordability (GDP per capita) [22] | Systematic search | |

| Dollars per generic, preferred or non-preferred equivalents (coverage) In questionnaire: | ||

|

1.receiving free samples from the doctor [28] 2.skip filling prescription because of high cost [28] 3.taking less medication than prescribed by doctor to save money [28] 4.being talked about the use of brand vs. generic drugs [29] |

Systematic search | |

| Real expenditure per capita [30] | Systematic search | |

| Effective co-payment rate (Cost-sharing expenditure divided by total expenditure) [30] | Systematic search | |

| Median MPR (median price ratio) of Innovator brand, most sold generic and low price generic drugs in Public Procurement Sector, Private Sector Retail Pharmacies, and Dispensing Doctors’ Sector [31] | Systematic search | |

| During the past 12 months, was there any time you needed prescription medicines but didn’t get them because you couldn’t afford it [32] | Systematic search | |

| % Households whose monthly medicine expenditures represent at least >20% of total expenditures [3] | Systematic search | |

| Average household medicine expenditures as % of total expenditures [3] | Gray literature | |

| Average household medicine expenditures as % of non-food expenditures [3] | Gray literature | |

| Average household medicine expenditures as % of total health expenditures [3] | Gray literature | |

| Average annualized health expenditures per person [3] | Gray literature | |

| Average HH medicine expenditures for a reported illness as a % of total expenditures [3] | Gray literature | |

| % HH with at least partial insurance coverage for at least one medicine [3] | Gray literature | |

| % respondents who say that prescribed medicines were not taken “because HH cannot afford medicines” [3] | Gray literature | |

| % respondents who can get free medicines at public health care facility [3] | Gray literature | |

| % respondents who agree medicines are more expensive at private pharmacies [3] | Gray literature | |

| % respondents who say they can get credit from the private pharmacy [3] | Gray literature | |

| % respondents who can usually afford to buy medicines they need [3] | Gray literature | |

| % respondents who agree that better insurance coverage would increase their use of medicines [3] | Gray literature | |

| % respondents who have had to borrow money or sell things to pay for medicines [3] | Gray literature | |

| Measuring Price Components [28] | Gray literature | |

| Types of free medicines [33] | Gray literature | |

| Types of fees charged [33] | Gray literature | |

| Type of insurance coverage [33] | Gray literature | |

| Percentage of cost covered [33] | Gray literature | |

| Public medicines budget and per capita drug expenditures [33] | Gray literature | |

| Affordability of treatment for adults and children under 5 years of age at public health facility dispensaries and private drug outlets [4] | Gray literature | |

| Price variation of key medicines in public health facility dispensaries and private drug outlets [4] | Gray literature | |

| Average cost of medicines at public health facilities and private drug outlets(by patient) [4] | Gray literature | |

| Price of key medicines [4] | Gray literature | |

| Price of pediatric medicines [4] | Gray literature | |

| Pharmaceutical spending per person and growth rate [34] | Systematic search | |

| Percent of population reporting not filling a prescription or skipping a dose because of costs during the previous 12 months [34] | Systematic search | |

| Human resources | Number of pharmacists (per 1000 pop) [35] | Systematic search |

| Density of pharmacists and pharmaceutical technicians per region [35] | Systematic search | |

| Number of pharmacists employed in the public and private sector or NGO [35] | Systematic search | |

| Density of pharmaceutical human resources per 10,000 population by cadre [8] | Gray literature | |

| Density of each pharmaceutical cadre per 10,000 population by facility type [8] | Gray literature | |

| Proportion of the workforce by cadre [8] | Gray literature | |

| Proportion of facilities with non-pharmaceutical cadres providing pharmaceutical services [8] | Gray literature | |

| % of facilities that comply with the law (presence of a pharmacist) [4] | Gray literature | |

| Quality & safety | % facilities with pharmacist, nurse, pharmacy aide/health assistant or untrained staff | |

| Dispensing [4] | Gray literature | |

| % facilities with doctor, nurse, trained health worker/health aide prescribing [4] | Gray literature | |

| % facilities with prescriber trained in RDU [4] | Gray literature | |

| Number of Quality Control samples taken for testing annually | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| Number of annual tested samples failed to meet quality standards | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| % of SSFFC medicines per Total medicines | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| Information and rational use | medication error in prescribing and administration | Gray literature (governmental document) |

| abuse of selected medicines (according to DID) | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| Average number of medicine prescribed per patient encounter [1, 36, 37] | Gray literature & systematic search | |

| Encounters with only one drug prescribed [36] | Systematic search | |

| Encounters with five or more drugs prescribed [36] | Systematic search | |

| Percentage of medicines prescribed by generic name [1, 36–38] | Gray literature & systematic search | |

| Percentage of medicine prescribed from an EML or formulary [1, 37] | Gray literature & systematic search | |

| Percentage encounters with an antibiotic prescribed [1, 36–38] | Gray literature & systematic search | |

| Percentage encounters with an injection prescribed [1, 36–38] | Gray literature & systematic search | |

| Prescriptions contain corticosteroids medicine as % of total prescription | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| Annual consumption of selected narcotic pain killers (mg/capita) | Gray literature (governmental document) | |

| % HH medicines taken for acute illness by category of providers who recommended or prescribed them [3] | Gray literature | |

| % HH medicines by source [3] | Gray literature | |

| % acute illnesses for which the class of medicines taken does not reasonably match recalled symptoms [3] | Gray literature | |

| % of acute illnesses treated with injections [3] | Gray literature | |

| % HH medicines with adequate label [3] | Gray literature | |

| % HH medicines with adequate primary packaging [3] | Gray literature | |

| % respondents who said prescribed medicines were not taken for a reason related to acceptability [3] | Gray literature | |

| % respondents who said prescribed medicines were not taken because of previous side effects [3] | Gray literature | |

| % HH classes of medicines kept for future use [3] | Gray literature | |

| % HH reporting a serious acute illness who did not seek care outside and did not take medicines [3] | Gray literature | |

| % HH reporting a serious acute illness who sought care outside but did not take all prescribed medicines [3] | Gray literature | |

| % HH with a chronically ill person who was never told to take medicines [3] | Gray literature | |

| % HH with a chronically ill person who does not take recommended medicines regularly [3] | Gray literature | |

| Drugs included in the WHO Model List [36] | Systematic search | |

| Drugs included in the National List of Essential Medicines [36] | Systematic search | |

| Drugs included in the local List of Essential Medicines [36] | Systematic search | |

| Drugs available in the same facility of the consultation [36] | Systematic search | |

| % of facilities that comply with the law (presence of a pharmacist) [4] | Gray literature | |

| % facilities with pharmacist, nurse, pharmacy aide/health assistant or untrained staff | ||

| Dispensing [4] | Gray literature | |

| % facilities with doctor, nurse, trained health worker/health aide prescribing [4] | Gray literature | |

| % facilities with prescriber trained in RDU [4] | Gray literature |

Expert consensus on indicators determination

At the end of round one of the Delphi exercise, 38 items achieved consensus using the average value. It means that 37 items were accepted and 1 item was rejected (from information and rational use field) in the first round. The distribution of accepted items was 16 items in physical availability and geographical accessibility, 16 items in affordability, 1 item in human resource, 3 items in safety and quality and 1 item in information and rational use. Remained 38 items were advanced to round two. After receiving feedback, the panel achieved consensus on accepting 30 items. Overall, 67 items determined as access indicators by completion of Delphi exercise.

Indicators systemic categorization

According to the results of the specialist-working group, the determined indicators were categorized into three categories of input (6 indicators), output (24 indicators) and outcome (37 indicators). The Food and Drug Administration, the National Health Institute, the Iranian Medical Association and the Association of Iranian Pharmacists will have the largest share in the data collection of indicators. In addition, 39 indicators require specialized periodic surveys. Other characteristics specified for each indicator, such as the frequency of the collection and levels of collection are interpreted in Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5.

Table 3.

Input indicators of access to medicine

| Main index | Sub-index | Collecting Frequency | Collecting Level | Source of Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical availability and geographical accessibility | Number of centers providing medicine | Annually | Provincial / National | IrFDA |

| Number of urban pharmacies per every 100,000 population | Annually | Provincial / National | IrFDA | |

| Number of 24 h urban pharmacies per every 100,000 population | Annually | Provincial / National | IrFDA | |

| Human resources | Number of pharmacists per every 1000 population | Annually | Provincial / National | Iran Medical Council / Iran Pharmacists Association |

| Concentration of pharmacists and Pharmaceutical technicians per district | Annually | Provincial | Iran Medical Council / Iran Pharmacists Association | |

| Concentration of Pharmaceutical human resources based on sort of work group per every 10,000 population | Annually | Provincial / National | Iran Medical Council / Iran Pharmacists Association |

IrFDA Iran food and drug administration

Table 4.

Output indicators of access to medicine

| Main index | Sub-index | Collecting Frequency | Collecting Level | Source of Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical availability and geographical accessibility | Availability of national essential medicine list for the country and its last revised date | Annually | National | IrFDA |

| Percentage of rarely medicine that are available in the formal list of the country | Annually | National | IrFDA | |

| Average time spent travelling to the daily and 24 h pharmacy | every 3 years | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Median distance from daily and 24 h pharmacy | every 3 years | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Financial access | Median/average price of essential medicines | Annually | National | IrFDA |

| Median/average price of medicines for pediatric diseases | Annually | National | Survey | |

| Percentage of free medicines available for patients | Annually | National | IrFDA | |

| Providing information for patients on benefit and side effects of using Brand and Generic medicines when they buying them | every 3 years | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Relative median from the brand price, the best-selling generic medicine and popular generic medicines in pharmacies | Annually | National | IrFDA | |

| Median/average expenditure of patients for essential medicines | Annually | National | Survey | |

| Median/average expenditure of patients for pediatric medicines | Annually | National | Survey | |

| Number of workday wages of a general laborer to pay for medicine in normal circumstances (a normal illness) | Annually | National | Survey | |

| Human resource | Percentage of pharmacies that work under the supervision of a pharmacist | every 3 years | Provincial / National | Survey |

| Safety and quality | Percentage of SSFFC medicines from the total medicine | Annually | Provincial / National | IrFDA |

| Number of expired medicines available on the shelves of pharmacies | every 3 years | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Information and rational use | Percentage of health centers that have been trained to prescribe medicine rationally | Annually | Provincial /National | IrFDA |

| Percentage of available medicines in the pharmacy that contain written instruction in the box | every 3 years | National | Survey | |

| Percentage of people who have not used the prescribed medicines due to not being admitted | every 3 years | National | Survey | |

| Percentage of people who have not used the prescribed medicines due to previous side effects | every 3 years | National | Survey | |

| Percentage of families that keep non-OTC or expired medicines at home for future use | every 3 years | National | Survey | |

| Outcome indicators per medicine | Percentage f people who have chronic disease but do not regularly use prescribed medicine | every 3 years | National | Survey |

| Percentage of medicine in a household that do not have appropriate label | every 3 years | National | Survey | |

| Percentage of medicine in a household that have appropriate initial boxing | every 3 years | National | Survey | |

| Percentage of medicine that contain instruction from entire medicines given to a patient | every 3 years | National | Survey |

IrFDA Iran food and drug administration

Table 5.

Outcome indicators of the access to medicine

| Main index | Sub-index | Collecting Frequency | Collecting Level | Source of Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical availability and geographical accessibility | Percentage of medicines available in the national list that are not found in any pharmacy | Monthly | National | IrFDA |

| Percentage of medicines available in the national list that are found in less than 25% of pharmacies | Annually | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Percentage of medicines available in the national list that are found in 25% to 50% of pharmacies | Annually | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Percentage of medicines that have been prescribed with generic name | Every 6 month | Provincial / National | IrFDA | |

| Percentage of medicines that have been prescribed from the national medicine list | Every 6 month | National | IrFDA | |

| Percentage of medicines available in the national list that are found in 50% to 75% of pharmacies | Annually | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Percentage of medicines available in the national list that are found in the more than 75% of pharmacies | Annually | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Percentage of outpatient medicines that are found in the access level one | Annually | National | Survey | |

| Percentage of outpatient medicines that are found in urban pharmacies | Every 6 month | National | IrFDA | |

| Percentage of patients that had to go to pharmacy several time to get their prescribed medicine | Annually | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Percentage of patients that had to go to the another city to get their prescribed medicine | Annually | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Percentage of rarely used medicines are not found in any pharmacy | Monthly | National | IrFDA | |

| Percentage of patients who had to get their medicine from black market | Annually | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Financial access | Total pharmaceutical expenditure of patient | Annually | National | Survey |

| Sum of pharmaceutical expenditure of patient as a percentage of total pharmaceutical expenditure | Annually | National | Survey | |

| Pharmaceutical inflation rate | Annually | National | IrFDA | |

| Sum of pharmaceutical expenditure per patient | Annually | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Average copayment/ coinsurance per patient for medicine during the last 4 weeks in pharmacies (patient’s expenditure) | Annually | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Household pharmaceutical expenditure as percentage of total expenditure | Annually | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Percentage of households that have at least one insurance coverage for a medicine | Annually | Provincial / National | Ministry of Cooperatives, Labor, and Social Welfare | |

| Average pharmaceutical expenditure of household as a percentage of total non-nutritional expenditure | Annually | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Average pharmaceutical expenditure of household as a percentage of healthcare expenditure | Annually | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Percentage of people who have not obtained their medicine due to pharmaceutical copayment/coinsurance | Every 2 years | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Percentage of people who take less amount of medicine than prescribed to cut the coast | Every 2 years | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Percentage of patient who do not take medicine as they cannot pay for it | Every 2 years | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Percentage of increase in the use of medicine after obtaining insurance coverage | Annually | National | Ministry of Cooperatives, Labor, and Social Welfare | |

| Percentage of people who had to borrow money or sell their home furniture to pay for medicine | Every 2 years | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Percentage of households whose pharmaceutical expenditure accounts for more than 20% of their total healthcare expenditure | Annually | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Safety and Quality | Duration of pharmaceutical counseling per every prescription or patient | Annually | National | Survey |

| Pharmaceutical error during perception and use | Every 6 month | Provincial / National | IrFDA | |

| Percentage of medicine misuse (per DDD) | Annually | Provincial / National | Survey | |

| Information, prescription and use | Average number of medicines prescribed for a patient | Annually | Provincial / National | IrFDA |

| Percentage of people that attend pharmacy with at least one prescribed antibiotic | Annually | Provincial / National | IrFDA | |

| Percentage of people that attend pharmacy with at least one injectable medicine | Annually | Provincial / National | IrFDA | |

| Percentage of people that attend pharmacy with at least one corticosteroid medicine | Annually | Provincial / National | IrFDA | |

| Average annual use of selected narcotic analgesia (mg/capital) | Annually | Provincial / National | IrFDA | |

| Percentage of acute diseases that have been cured by injectable medicines | Annually | Provincial / National | Survey |

IrFDA Iran food and drug administration

Discussion

To ensure a continuous access to medicine, good evaluation tools are crucial. This report is an effort to develop a comprehensive list of quantitative indicators for assessing all aspects of access to medicine –as a system- for the first time. This study suggests four dimensions of access, including 1- physical availability and geographical accessibility, 2- affordability, 3- human resources, 4- quality and safety, and 5- information and rational use. Another categorization is based on the system components. Where, facilities and human resources are assumed as inputs, developed criteria, regulations and access infrastructures are assumed as outputs and the effect on people accessibility are assumed as outcomes. Since the impact is the long-term effect of the outcomes, it is so hard to measure particular in a health system that multiple variables –beyond the access to medicines- are involved. On the other hand, the impact is what the health system hopes their efforts will accomplish. It is the principal goal of a health system that will happen in the future and often is uncertain and immeasurable at this time. Therefore, assessing a system according to inputs, outputs and outcomes are more tangible and common in countries.

Countries all around the world have been carried out several surveys to appraise their pharmaceutical system that were included in systematic search as valuable experiences. Most studies employed standardized methodology developed by WHO [1, 10–12, 16, 20, 26, 31, 35, 36]. Also, none of them has presented system approach. Some countries have used some more important indicators to map their pharmaceutical situation [9, 13–15, 21, 25, 27, 32, 34]. Some surveys have adapted for assessing the accessibility in a special disease situation [15, 16, 20, 26]. Cummings et al. mentioned the racial and socioeconomic variables [14]. Lin and Taira focused on elderly population [17, 29]. In contrary Wang et al. reported the accessibility to pediatric essential medicine [27]. In that report, authors confine to physical availability in selected facilities as an availability indicator and measuring the price of medicines and compare it with patient wage as an affordability indicator. Lee et al. examined the effect of some reimbursement methods on societal affordability [23]. According to our result, the payment for medicines and proximity to community pharmacies are more frequent variables for most of the countries [17–19], and weightiest indicators in Delphi rounds. This result is a reflection of the importance of geographical accessibility and affordability in providing access. It is confirmed that the most significant barrier to access to medicine is fiscal [22]. There are some non-monetary determinants, which influence affordability. These determinants include patient income, employee status, and insurance or social security coverage [25]. Generic substitution could lead to significant improvement in affordability. According to a cost minimization study, the cost saving of using generics instead of originator brands in low and middle-income countries is estimated about 8 to 89% [39]. Mass generic production of new anticancer medicines can reduce treatment costs by up to 30 times [40]. The advantage of generic prescribing is making patient enable to select between available substitutes and not to be limited to the brand medicines. To enhance substitution without concerns, the quality assessment of generics is essential. Results of generic formulations assessment showed it is required to improve the registration process for generic products based on international standards of Common Technical Documents (CTDs) in Pakistan. [41] In Nigeria, physician’s greatest concern over the prescription of generic medicines has been reported the worry of failure in treatment because of quality [42]. Sufficient regulations to assuring generic medicine quality are crucial to protecting society from potentially unsafe effects or inefficient medicines that might lead to a waste of resources. Availability of qualified pharmaceutical human resources is effective on public education and health [43]. Globally, there is critical human resource deficiency for health, most of which are inefficient. However, it is more serious in developing countries. Sometimes the main problem is the distribution of health workers, in particular, specialist health workers that could have a significant impact on quality, safety, information and rational use of medicine. Although WHO has emphasized on quality of medicines superior to other dimensions of accessibility [44, 45] it was neglected in previous studies. This study attempts to accumulate quality and safety indicators in all aspects of pharmaceutical products and services. WHO defined the rational use of medicine as “Patients receive medications appropriate to their clinical needs, in doses that meet their own individual requirements, for an adequate period of time, and at the lowest cost to them and their community [46].” Nonetheless, the size of prescribing medicines, antibiotics, injections and corticosteroids are current indicators for assessing the rational use of medicines in most of the countries [1, 36–38]. Generally, the use of antibiotics and injectable formulations is high in many developing countries. Nowadays, microbial resistance is a global challenge. Selling antibiotics in the form of over the counter (OTC) is illegal, but in developing countries, most patients buy antibiotics in pharmacies without any prescription [47–49]. Even if there are strict laws to prevent this from happening and the pharmacy does not dispense the medication, the patient will go to another pharmacy and take the requested medication. The results of a systematic review showed the supply of antibiotics without prescription following a patient request, was 78% [49].

One of the major concerns about the irrational use of misplaced and unsafe injections is associated with the potential risk of transmission of hepatitis B and C, HIV/AIDS and other life-threatening problems [50].

According to systematic search results in this study, the number of medicines included in the National List of Essential Medicines is one of the selected indicators for assessing rational use of medicines. On the contrary, in some studies, it has been shown that the availability of a larger list of formulary does not always reflect a better quality of care. In the review of essential medicines in Stockholm for over 15 years, it has been shown that the number of items in the list has remained roughly constant during these years [51]. However, contrary to the assumption, prescribers’ adherence in the core list has increased from 75% to 84% [51]. The Stockholm model for the wise use of medicine has been introduced as a multidimensional approach to improving the quality of rational use of medicine in primary care and in the hospital [52]. This approach recommends that to improve the trust of physicians to the wise-list (essential medicine list) and increased adherence, use the comprehensive communication strategy and recommendations that have also electronic access, continuous medical education and involvement of professional networks and patients may be helpful [53].

The association between the number of medicines prescribed for patients and the quality of care is a major concern in countries with both high rates of infectious diseases such as HIV and non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and hypertension [54, 55]. However, the question raised is whether the size of prescribing selected medicines could reflect the rationality of prescription. Recent research in Namibia has shown that WHO/INRUD indicators have poor accuracy in assessing prescribing practices and using national guidelines better reflects the quality of care [56]. The availability of the guidelines is an important factor that influences the use of them and also enhances adherence and performance of practitioners [57]. In this study, according to the collected indicators, it has been shown that the WHO guidelines for financial and geographic accessibility, as well as human resources, are not complete without systematic searches [8, 24, 28, 30, 33].

Specialist working groups in this study tried to extend the indicators to cover prescribing medication errors. Even so, the authors believe that further studies are necessary to improve the rational use of medicines indicators.

Conclusion

In conclusion, to comprehend the extent to which the health system has achieved its goals of providing access to medicines for its society and contributed to better health status, it is important to evaluate the whole pharmacotherapy chain from availability of qualified medicines for rational use of them. Accessibility at a national level is a system that needs assessment in all components, including inputs, outputs, and outcomes. Several indicators were identified at each stage that the weightiest being geographical accessibility and affordability and then after human resources indicators. Further studies are needed to improve access to medicine assessment from quality and rational use perspectives.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the panelists for their even-handed cooperation in this project. Iran National Institute of Health Research and National Institute for Medical Research Development (NIMAD) supported this work.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All the authors listed in this article have scientifically contributed significantly to do this research and they declare no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mahmood A, Elnour AA, Ali AA, Hassan NA, Shehab A, Bhagavathula AS. Evaluation of rational use of medicines (RUM) in four government hospitals in UAE. Saudi Pharm J. 2015; 24(2):189–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Geographic healthcare access and place, a research brief. 2014.

- 3.World Health Organization . Manual for the household survey to measure access and use of medicines. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . WHO operational package for assessing, monitoring and evaluating country pharmaceutical situation. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.How to develop and implement a national drug policy: World Health Organization; 2001.

- 6.WHO operational package for assessing, monitoring and evaluating country pharmaceutical situation: World Health Organization; 2007.

- 7.Weaver WT. The Delphi forecasting method. The Phi Delta Kappan. 1971;52(5):267–271. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . Pharmaceutical human resources assessment tool. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabde YD, et al. Mapping private pharmacies and their characteristics in Ujjain district, Central India. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang M, Yang S, Yan K, Liu J, Zhao J, Fang Y. Measuring access to medicines: a survey of prices, availability and affordability in Shaanxi Province of China. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70836. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotwani A. Where are we now: assessing the price, availability and affordability of essential medicines in Delhi as India plans free medicine for all. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinto CDBS, Miranda ES, Emmerick ICM, Costa NR, Castro CGSO. Medicine prices and availability in the Brazilian popular pharmacy program. Revista de Saude Publica. 2010;44(4):611–619. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102010005000021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen W, et al. Availability and use of essential medicines in China: manufacturing, supply, and prescribing in Shandong and Gansu provinces. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cummings JR, Wen H, Ko M, Druss BG. Race/ethnicity and geographic access to Medicaid substance use disorder treatment facilities in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):190–196. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akullian AN, Mukose A, Levine GA, Babigumira JB. People living with HIV travel farther to access healthcare: a population-based geographic analysis from rural Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Emmerick IC, et al. Access to medicines for acute illness in middle income countries in Central America. Rev Saude Publica. 2013;47(6):1069–1079. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102013000901069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin SJ. Access to community pharmacies by the elderly in Illinois: a geographic information systems analysis. J Med Syst. 2004;28(3):301–309. doi: 10.1023/B:JOMS.0000032846.20676.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Law MR, Heard D, Fisher J, Douillard J, Muzika G, Sketris IS. The geographic accessibility of pharmacies in Nova Scotia. Can Pharm J. 2013;146(1):39–46. doi: 10.1177/1715163512473062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norris P, Horsburgh S, Sides G, Ram S, Fraser J. Geographical access to community pharmacies in New Zealand. Health Place. 2014;29:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emmerick IC, et al. Barriers in household access to medicines for chronic conditions in three Latin American countries. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):015–0254. doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0254-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emmerick ICM, et al. Farmácia popular program: changes in geographic accessibility of medicines during 10 years of a medicine subsidy policy in Brazil. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2015;8(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s40545-015-0030-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wahlster P, Scahill S, Lu CY. Barriers to access and use of high cost medicines: a review. Health Policy Technol. 2015;4(3):191–214. doi: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2015.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee I-H, Bloor K, Hewitt C, Maynard A. The effects of new pricing and copayment schemes for pharmaceuticals in South Korea. Health Policy. 2012;104(1):40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davidová J, Ivanovic N, Práznovcová L. Participation in pharmaceutical costs and Seniors' access to medicines in the Czech Republic. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2008;16(1):26–28. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perlman F, Balabanova D. Prescription for change: accessing medication in transitional Russia. Health Policy Plan. 2011;26(6):453–463. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jingi AM, Noubiap JJN, Ewane Onana A, Nansseu JRN, Wang B, Kingue S, et al. Access to diagnostic tests and essential medicines for cardiovascular diseases and diabetes care: cost, availability and affordability in the west region of Cameroon. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Wang X, Fang Y, Yang S, Jiang M, Yan K, Wu L, et al. Access to paediatric essential medicines: a survey of prices, availability, affordability and price components in Shaanxi Province, China. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e90365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.World Health Organization . Measuring medicine prices, availability, affordability and price components. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taira DA, Iwane KA, Chung RS. Prescription drugs: elderly enrollee reports of financial access, receipt of free samples, and discussion of generic equivalents related to type of coverage. Am J Manag Care. 2003;9(4):305–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costa-Font J, Kanavos P, Rovira J. Determinants of out-of-pocket pharmaceutical expenditure and access to drugs in Catalonia. Appl Econ. 2007;39(5):541–551. doi: 10.1080/00036840500438947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Babar ZUD, Ibrahim MIM, Singh H, Bukahri NI, Creese A. Evaluating drug prices, availability, affordability, and price components: implications for access to drugs in Malaysia. PLoS Med. 2007;4(3):e82. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cunningham PJ. Medicaid cost containment and access to prescription drugs. Health Aff. 2005;24(3):780–789. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.3.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Level, I., Using indicators to measure country pharmaceutical situations.

- 34.Morgan S, Kennedy J. Prescription drug accessibility and affordability in the United States and abroad, vol. 89: Issue brief (Commonwealth Fund); 2010. p. 1–12. [PubMed]

- 35.Welfare MoHaS. Assessment of the pharmaceutical human resources in Tanzania and the strategic framework. Tanzania; 2009.

- 36.Ferreira MBC, Heineck I, Flores LM, Camargo AL, Dal Pizzol TS, Torres ILS, et al. Rational use of medicines: prescribing indicators at different levels of health care. Braz J Pharm Sci. 2013;49(2):329–40.

- 37.World Health Organization . The world medicines situation. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terry Green SG. Identifying medicine use problems using indicator based studies in health facilities. 2012: Food and Drug Administration.

- 39.Cameron A, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Leufkens HGM, Laing RO. Switching from originator brand medicines to generic equivalents in selected developing countries: how much could be saved? Value Health. 2012;15(5):664–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woerkom M, et al. Ongoing measures to enhance the efficiency of prescribing of proton pump inhibitors and statins in the Netherlands: influence and future implications. J Comp Eff Res. 2012;1(6):527–538. doi: 10.2217/cer.12.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Babar A, et al. Assessment of active pharmaceutical ingredients in drug registration procedures in Pakistan: implications for the future. GaBI J. 2016;5(4):156–163. doi: 10.5639/gabij.2016.0504.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fadare JO, Adeoti AO, Desalu OO, Enwere OO, Makusidi AM, Ogunleye O, et al. The prescribing of generic medicines in Nigeria: knowledge, perceptions and attitudes of physicians. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;16(5):639–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Wuliji T, Carter S, Bates I. Migration as a form of workforce attrition: a nine-country study of pharmacists. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7(1):32. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Embrey MA. Managing access to medicines and health technologies: Kumarian Press; 2014.

- 45.World Health Organization, How to develop and implement a national drug policy: World Health Organization; 2001.

- 46.World Health Organization, Promoting Rational Use of Medicines: Core Components-WHO Policy Perspectives on Medicines. WHO; 2002 [cited 2016 31 May].

- 47.Moise K, Bernard JJ, Henrys JH. Evaluation of antibiotic self-medication among outpatients of the state university hospital of Port-Au-Prince, Haiti: a cross-sectional study, vol. 28: The Pan African Medical Journal; 2017. p. 4–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Lansang MA, Lucas-Aquino R, Tupasi TE, Mina VS, Salazar LS, Juban N, et al. Purchase of antibiotics without prescription in Manila, the Philippines. Inappropriate choices and doses. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(1):61–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Auta A, et al. Global access to antibiotics without prescription in community pharmacies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Inf Secur. 2019;78(1):8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mahmood A, Elnour AA, Ali AAA, Hassan NAGM, Shehab A, Bhagavathula AS. Evaluation of rational use of medicines (RUM) in four government hospitals in UAE. Saudi Pharm J. 2016;24(2):189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eriksen J, Gustafsson LL, Ateva K, Bastholm-Rahmner P, Ovesjö ML, Jirlow M, et al. High adherence to the ‘wise list’ treatment recommendations in Stockholm: a 15-year retrospective review of a multifaceted approach promoting rational use of medicines. BMJ Open. 2017;7(4):e014345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Bjorkhem-Bergman L, et al. Interface management of pharmacotherapy. Joint hospital and primary care drug recommendations. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(Suppl 1):73–78. doi: 10.1007/s00228-013-1497-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gustafsson LL, Wettermark B, Godman B, Andersén-Karlsson E, Bergman U, Hasselström J, et al. The 'wise list'- a comprehensive concept to select, communicate and achieve adherence to recommendations of essential drugs in ambulatory care in Stockholm. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;108(4):224–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Rwegerera GM, Moshomo T, Gaenamong M, Oyewo TA, Gollakota S, Mhimbira FA, et al. Antidiabetic medication adherence and associated factors among patients in Botswana; implications for the future. AJM. 2018;54(2):103–9.

- 55.Meyer JC, Schellack N, Stokes J, Lancaster R, Zeeman H, Defty D, et al. Ongoing initiatives to improve the quality and efficiency of medicine use within the public healthcare system in South Africa; a preliminary study. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Niaz Q, Godman B, Massele A, Campbell S, Kurdi A, Kagoya HR, et al. Validity of World Health Organisation prescribing indicators in Namibia’s primary healthcare: findings and implications. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Mashalla YJ, et al. Availability of guidelines and policy documents for enhancing performance of practitioners at the primary health care (PHC) facilities in Gaborone, Tlokweng and Mogoditshane, Republic of Botswana. J Public Health Epidemiol. 2016;8(8):127–135. doi: 10.5897/JPHE2016.0812. [DOI] [Google Scholar]