Abstract

Background

Quality of life (QOL) is always considered as a final consequence of clinical trials, interventions, and health care. The results of studies indicate that addiction leads to lower QOL. However, studies have been conducted on the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on improving QOL. The aim of this study was to investigate the efficacy of mindfulness-based relapse prevention (MBRP) on QOL and craving in methadone-treated patients.

Methods

This study was conducted in Qom, Iran, in 2017. A sample of 70 methadone-treated patients were randomly selected and assigned to two groups (intervention and control). Participants in both groups completed the 36-item Short Form (SF-36) QOL Questionnaire and Craving Beliefs Questionnaire (CBQ) at the beginning of the study (pre-test), 8 weeks after the study (post-test), and two months after the study (follow up). In this study, the experimental group received 8 training sessions on mindfulness prevention, while the control group did not receive general information about addiction and did not receive any psychological intervention. Finally, data of 63 patients were analyzed with the SPSS software, chi-square test, t-test, and repeated-measures ANOVA.

Findings

The results of repeated-measures ANOVA showed that there was no significant difference between intervention and control groups in the pre-test, but MBRP in the intervention group significantly increased the scores of QOL and decreased the scores of craving, significantly (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

The findings of present study indicate that MBRP training can increase the psychological and physical health in dependent methadone-treated patients and decrease craving. These findings suggest that mindfulness training can be used as an effective intervention for improving QOL and reducing craving.

Keywords: Mindfulness, Quality of life, Craving

Introduction

The prevalence of drug-related disorders is highest in comparison with other clinical problems. According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)’s annual report, the prevalence of substance use disorder (SUD) in the general population is 35.3%.1 The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) reports that Iran has the highest proportion of opium users in the world, and the highest prevalence rate is 2.8% among individuals in Iran.2 In recent years, advanced mental health professionals and educational and therapeutic institutions have experimented with theories, models, methods, strategies, and techniques for treating addiction and relapse preventing after drug discontinuation. However, no definitive treatment has yet been found. Even after that the dependent person has discontinued the use of the substance for a long time, one does not hope to stop using it for ever.3 In a review, 40%-60% of the patients treated with the drug relapsed to the drug within one year of treatment.4 Relapse is detectable by signs that are predicted in long use; one of the structures that is tied to relapse is craving. Craving is recognized as one of the most important factors in relapse process5 which is often referred to as an indicator of therapeutic success, as it may be a sign of an impending relapse.6 Craving is considered as the main driving force in SUD and its effective adjustment is associated with lower use and desirable outcomes.7

The findings indicate that craving has a negative relationship with other psychological triggers such as smoking, stress, impulsivity, as well as a positive relationship with distress tolerance in drug abusers.8 Craving can be considered as the personal experience of forced substances use or strong desire for something (substance use) that makes it impossible to focus on anything other than it.9 Different researchers and theorists have studied the causes of substance abuse; one of the most important causes of relapse is low quality of life (QOL).10 The addiction has important effects on the health of addicts.11 Many professionals consider addiction to be a factor that can lower QOL. Many studies have shown that drug abuse is associated with lower QOL.10,12 QOL is a collection of emotional and cognitive responses from individuals to their physical, psychological, and social status, which is always a final consequence of clinical trials, interventions, and health care.13

Studies have also shown that QOL in opioid dependents is lower than the non-psychiatric patients and general population, but is equated with psychiatric patients.14 QOL has been recognized as an important factor in the reduction of physical and psychological symptoms, and there are many indications that QOL is an important prognosis in therapeutic situations.15 There are psychological treatments for improving QOL and preventing the craving, including supportive care, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and mindfulness-based therapy (MBT).16 MBT helps clients to lessen their thoughts and feelings in real and dogmatic ways, see personal responses to mental distress, and progress toward life values.17 There are theories in which it is believed that cognition and emotion should be considered in the conceptual context of phenomena. For this reason, instead of approaches such as CBT that corrects cognitive and inferior beliefs to correct emotions and behaviors, here the patient is taught to take his emotions in the first step and live with "here and now" to have more psychological flexibility.17,18 In these therapies, cognitive and behavioral techniques are combined with awareness.18 Theoretical foundations and the conceptual framework of this research are based on the Marlatt's theoretical framework which says that increasing self-awareness improves coping skills through meditation of mindfulness.19

Substance-dependent individuals can be trained to recognize early warning signs of intake. The mindfulness-based intervention, due to its mechanisms such as acceptance, increase of awareness, sensitization, momentary presence, observation without judgment, dream, and release, is combined with traditional CBT techniques due to the positive effect on processes of therapy.20 According to research findings, one of the associative factors with craving is mindfulness.9 studies showed that mindfulness exercises reduced the craving of smoking.21 Also, descriptive findings report the negative relationship between mindfulness and substance abuse. The mindfulness reduces the craving of the drug abuse22 and predicts the higher level of mental health and lowers the use of alcohol, tobacco, and narcotics.23

Mindfulness through effective admission and attention is effective in reducing unpleasant inner emotions and states.17 Stress is one of the components of substance abuse that affects the psychological component of QOL and causes significant loss in various areas of life of patients.24 Mindfulness-based interventions are effective in reducing drug use.25 Combining prevention education with mindfulness can be relatively successful in treatment of drug abuse.20 The higher mental awareness is associated with less alcohol, tobacco, and drug use.25 Therefore, this study was done to determine the effectiveness of the mindfulness-based relapse prevention (MBRP) model on QOL and craving in methadone-treated patients.

Methods

This randomized controlled clinical trial was done in 2017. The study population included opiate-dependent men (aged 20-50 years) referring to methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) centers in Qom, Iran, from September to October 2017. The sample size of this study was according to previous relevant study. According to the study by Bowen et al.,20 for comparison of the groups in terms of the effectiveness of mindfulness on craving, an indicator of the effect size between the control and intervention group was reported 71%. With a confidence interval (CI) of 95% and a test power of 90%, using the Cohen’s formula, 28 people were needed in each group. But with 20% drop, we estimated 35 patients in each group to get more reliable results.

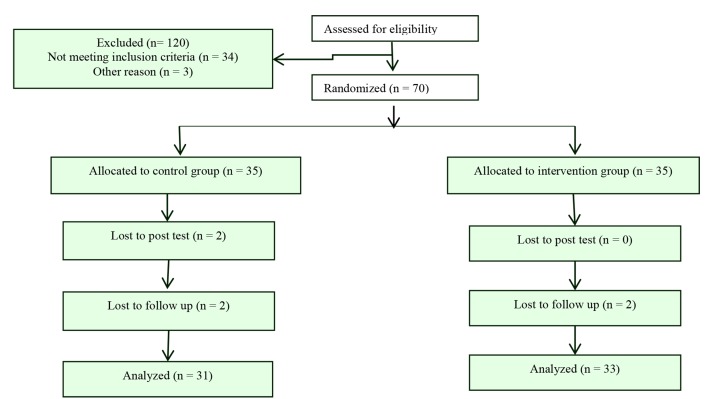

To conduct this research, referring to MMT centers in Qom, the list of persons applying for treatment was prepared and 120 persons were selected based on the criteria for entry and exit. The criteria for entering were: being between the age of 18-50 years, being treated with methadone, and having cycle degree. Excluding criteria were: the occurrence of mental disorders, absences of more than two sessions, co-dependence on substances other than opiates, and participation in other therapies simultaneously. Of these 120 people, 70 were randomly selected. In the next stage, two groups of 35 were randomly selected and placed in intervention and control groups (Figure 1). It was also conducted with all Structured Clinical Interviews (SCID-IV) for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-4th Edition (DSM-IV). Prior to the intervention, the rules and regulations of each session were presented, the treaty was adjusted, and the number and duration of each session was determined.

Figure 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram of study

The control group received only general information about the substance use. Both groups received methadone therapy and completed 36-item Short Form (SF-36) QOL Questionnaire and Craving Beliefs Questionnaire (CBQ) at the beginning of the study (pre-test), after the end of MBRP sessions (post-test), and finally two months after the end of the sessions (follow up). The treatment consisted of 8 sessions of 2 hours, each one with two parts of 45 minutes and 15 minutes of rest between them.

Demographic information questionnaire: The questionnaire had five questions that were used to collect the demographic information of the participants in the study. This questionnaire included questions about: employment status, age, level of education, marital status, and drug use history of the participants in the study.

CBQ: The questionnaire is a personal self-report scale that measures the beliefs of craving. The questionnaire has 20 items which are graded on a 7-point Likert scale (from totally agree to completely disagree). The Cronbach's alpha coefficient for that was 0.84.26 In Iranian studies, Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.84 and 0.81 have been reported, which indicate the validity and reliability of this scale, respectively.27

SF-36 quality of life questionnaire: This questionnaire was developed in 1992 and validated outside Iran. For example, in a research that evaluated the psychometric status of this questionnaire in China, the internal consistency coefficient was 0.82 and the reliability coefficient of the two semi-tests was 0.72.28 The questionnaire has 36 questions in eight dimensions that include physical performance dimensions, functional limitations due to physical problems, physical pain, general health, feeling of vitality, mental health, limitation of performance with regard to emotional issues, and social performance. The total score of the eight-dimensional health scores ranges from 0 to 100, which higher scores indicate better health status. Torkan et al. evaluated the reliability of this questionnaire using its internal consistency and its validity. The reliability test of the questionnaire was done using the statistical analysis of "internal consistency" and the validity was evaluated using the "comparison of well-known groups" and "convergence validity". The analysis of "internal consistency" showed that except for the vitality scale (α = 0.65), other scales of Persian version of SF-36 had the minimum standard reliability coefficients in the range of 0.77 to 0.90.29

Ethical considerations: This research has been reviewed and approved by the Vice Chancellor of Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran (No. 96149). Each participant completed the informed consent form and was also told to leave the study if not wanting to continue the session.

Results

In this study, 70 men treated with MMT were studied. Participants were placed in two groups of MBRP and control. Each group included 35 subjects. 4 members were excluded in the intervention group due to irregular presence and non-completion of the follow-up questionnaire, and 2 in the control group were excluded due to failure to complete the questionnaires in the post-test and follow-up stages of the study. Data were collected from 64 subjects (31 in the intervention group and 33 in the control group) (Figure 1).

There were no significant correlations between employment status, age, level of education, and marital status in two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants in both groups

| Variable | Control | MBRP | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) (mean ± SD) | 30.26 ± 5.13 | 29.82 ± 5.34 | 0.670 |

| Job [n (%)] | 0.740 | ||

| Employed | 25 (80.64) | 26 (78.78) | |

| Jobless | 6 (19.35) | 7 (21.22) | |

| Education level [n (%)] | 0.730 | ||

| Under diploma | 22 (70.96) | 25 (75.74) | |

| Diploma | 9 (20.03) | 8 (24.26) | |

| Marital status [n (%)] | 0.720 | ||

| Married | 23 (74.19) | 24 (72.72) | |

| Single | 8 (25.80) | 9 (27.28) |

SD: Standard deviation; MBRP: Mindfulness-based relapse prevention

The mean and standard deviation (SD) of craving in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up phases are presented in table 2. The mean of craving in pre-test in the intervention group was 89.52 ± 14.34 and in the control group was 83.37 ± 17.54. The difference in the scores of the two groups in pre-test was not significant. The mean score of post-test craving in the intervention group was 67.46 ± 11.14 and in the control group was 82.63 ± 18.57.

Table 2.

The comparison of craving at pre-test, post-test, and follow-up phases in both gr

| Variable |

Treatment phase |

P |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Craving | Pre-test (mean ± SD) | Post-test (mean ± SD) | Follow-up (mean ± SD) | Time | Time group* |

| Intervention | 89.52 ± 14.34 | 67.46 ± 11.14 | 67.28 ± 10.76 | 0.020 | < 0.001 |

| Control | 83.37 ± 17.54 | 82.63 ± 18.57 | 83.19 ± 18.78 | 0.070 | < 0.001 |

Repeated measures ANOVA

SD: Standard deviation

In the follow-up phase, this score in the intervention group was 67.28 ± 10.76 and in the control group was 83.19 ± 18.78. According to table 2, mindfulness education reduced craving in intervention group in comparison to control group. The changes in craving scores and in the post-test and follow-up phases are presented in table 2.

Mauchly’s test of sphericity showed that the uniformity of matrix variance-covariance was not confirmed (W = 0.638, P < 0.001). However, Hayling test (F = 1.08, P < 0.001) showed a relationship between membership in the group and the intervention phase (time). The results of repeated measures ANOVA are presented in table 3.

Table 3.

The comparison of quality of life (QOL) at pre-test, post-test, and follow-up phases in both groups

| Variable | Pre-test (mean ± SD) |

Post-test (mean ± SD) |

Follow-up (mean ± SD) |

P |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Time | Time group* | |

| Vitality | 43.21 ± 9.79 | 43.39 ± 4.44 | 46.12 ± 8.48 | 43.24 ± 4.44 | 46.17 ± 8.36 | 43.47 ± 4.44 | 0.490 | 0.020 |

| Physical functioning | 41.74 ± 12.14 | 40.92 ± 9.51 | 42.82 ± 11.27 | 40.87 ± 9.34 | 42.07 ± 10.15 | 40.69 ± 9.13 | 0.530 | 0.370 |

| Physical pain | 43.56 ± 8.14 | 42.94 ± 9.04 | 46.17 ± 7.93 | 43.87 ± 8.88 | 45.43 ± 8.13 | 42.28 ± 9.04 | 0.240 | 0.180 |

| General health perceptions | 47.59 ± 6.31 | 46.77 ± 4.84 | 54.46 ± 4.94 | 45.68 ± 5.12 | 53.88 ± 6.37 | 44.62 ± 4.79 | 0.030 | < 0.001 |

| Physical role functioning | 42.18 ± 6.42 | 43.11 ± 4.44 | 47.25 ± 5.84 | 42.27 ± 4.44 | 46.07 ± 5.40 | 42.82 ± 4.44 | 0.110 | 0.310 |

| Emotional role functioning | 44.29 ± 5.34 | 44.87 ± 8.61 | 50.64 ± 6.23 | 44.52 ± 9.44 | 49.39 ± 5.74 | 43.32 ± 8.83 | 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Social role functioning | 43.25 ± 7.13 | 45.17 ± 6.52 | 48.37 ± 7.94 | 42.77 ± 7.19 | 48.68 ± 6.45 | 43.45 ± 6.34 | 0.010 | 0.009 |

| Mental health | 46.56 ± 9.14 | 50.19 ± 8.16 | 53.82 ± 8.48 | 48.81 ± 7.74 | 52.39 ± 7.91 | 49.07 ± 7.24 | 0.140 | < 0.001 |

| General QOL | 43.87 ± 9.47 | 43.27 ± 6.26 | 46.37 ± 8.12 | 43.69 ± 7.53 | 45.83 ± 8.46 | 42.86 ± 5.37 | 0.010 | < 0.001 |

Repeated measures ANOVA

SD: Standard deviation; QOL: Quality of life

The mean and SD of the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up periods for QOL and its subscales are presented in table 3. The mean of QOL of total pre-test in the MBRP group was 43.87 ± 9.47 and in the control group was 43.27 ± 6.26. The difference in the scores of the two groups before the intervention was not significant. The mean score of post-test QOL in the MBRP group was 46.37 ± 8.12 and in the control group was 43.69 ± 7.53. In the follow-up phase, this rate in the MBRP group was 45.83 ± 8.46 and in the control group was 42.86 ± 5.37. Also, changes in QOL scores and its subscales in the post-test and follow-up periods are presented in table 3. Repeated measures ANOVA was used to compare the changes in QOL scores in three phases of study. The findings showed that the general score of QOL and its subscales in the MBRP group had a significant change compared to the control group (P ≤ 0.050) (Table 3).

Discussion

The study showed that mindfulness training could reduce the craving in methadone-treated patients. Finding of this study is consistent with findings of previous studies.16,30 For example, Bowen et al. in their study found that patients who received MBRP training reported lower levels of craving in comparison to control group who received treatment as usual.25 The findings are consistent with importance of interventions that increase mindfulness principles including acceptance and awareness and help patients foster a nonjudgmental view of their experience.

Attending to these processes may influence both the experience of craving and response to it.25 In addition, the findings showed that mindfulness training could improve QOL in methadone-treated patients, that is consistent with results of previous studies.31-33 For example, Habibi et al. investigated the effectiveness of mindfulness therapy on improving the QOL of addicts in terms of physical and psychological health. The experimental group received 8 sessions of mindfulness-based intervention, while control group did not receive any intervention during this period. The results showed that mindfulness training in the MBRP group significantly increased scores of physical and psychological health.34 Mindfulness can improve QOL and reduce craving in methadone-treated patients. Several studies have shown that addiction is associated with a defect in the function of the impulse control network, which is associated with the prefrontal cortex.30 Therefore, improving the function of the prefrontal cortex may lead to self-regulation and emotional regulation, thereby helping to treat addiction.35 On the other hand, the findings of the biological nervous system also support the hypothesis that the mindfulness meditation increases awareness and creates alternatives for neglecting and impulsive behavior.20 Mindfulness not only strengthens the strategies of coping with the craving of drug use, but also is a substitute for addiction and destructive behaviors. In fact, by managing or controlling craving instead, healthy alternative behaviors can prevent drug use.36

Mindfulness with an emphasis on acceptance instead of suppressing thoughts17 and the breakdown of drug-related recurrence stress increases recovery probability.9 Mindfulness training can increase cognitive control over craving and reduce stress associated with reduced drug use; therefore, it also plays a role in treating drug inactivity.37 Mindfulness with attention control and related emotional regulation, can be effective in controlling these disorders by increasing control over the visual clues of substance use and alcohol.33 Stress is one of the most important associative factors of substance abuse, which greatly affects the psychological component of QOL.38 Many studies have proved the effectiveness of mindfulness in reducing stress.39 Studies have shown that mindfulness and psychosocial flexibility can reduce distress17 and they suggest that mindfulness and psychological flexibility can play an important role in the control of anxiety, depression, and other psychological distress.40 By learning mindfulness, clients can manage stressful aspects of drug use and improve self-esteem, QOL, and psychological well-being.20

Mindfulness-awareness training can increase the coping strategies of addicts. When they get new information and skills in relation to psychological care during the treatment, this situation becomes more tolerable for them and they can be better adapted to it.17 In fact, it can be said that mindfulness through strengthening the coping strategy leads to reduction of anxiety and psychological distress and thus improves self-efficacy and, consequently, increases the QOL.34

Mindfulness teaches addicts to see their thoughts as thought, regardless of any content they may have. They learn to receive their thoughts more objectively as transient psychological events. When a person is in a state of observation, he is less influenced by his thoughts. The positive effects of this process can be seen in craving control. This will help them increase their capacity to prevent rumination.36 Addicts may have different experiences, such as sadness, feeling of failure, dissatisfaction, waiting for punishment, self-blame, or even suicidal ideation; this process, i.e., seeing thought as thought, helps addicts to manage them.32

Applying mindfulness exercises, including physical scanning, helps addicts make more effective strategies for adjusting emotions. When emotions are revealed in the form of thoughts or simultaneously with physical sensations, if one learns to stay in his body with his body sensations, his emotional responsiveness will decrease. Mindfulness by this mechanism can be useful in decreasing craving and relapse probability. Based on studies, it can be claimed that mindfulness-based intervention can be done through various mechanisms to improve the QOL and reduce the probability of relapse through effective reduction of craving.41 MBT has been shown as an effective method in the treatment of SUDs. Investigation of the neurobiological and behavioral dysfunction in SUDs suggests the promising aspect of mindfulness for SUD. Mindfulness may help the addicts decrease avoidance, tolerate unpleasant withdrawal and emotional states (stress-related), and unlearn maladaptive behaviors (rumination). Additionally, it may decrease the interactions between these processes, thus, decreasing their additive effects on substance use.33,41 Also, mindfulness-based intervention as an effective treatment can reduce the craving and improve physical and mental health by various mechanism in methadone-treated patients.

Conclusion

The findings of present study indicated that mindfulness training could improve QOL and reduce the craving and, consequently, relapse rates in opioid-dependent addicts. In addition, mindfulness-based intervention was suggested as a treatment for improving QOL and also reducing craving. Mindfulness-based intervention can be used as an effective, available, and low-cost intervention for addicts. Limitations of this study include research sample limitation to men and short duration of follow-up. To raise the generalizability and reliability, further studies with longer follow-up periods and both men and women patients, and also studies comparing mindfulness-based intervention with golden therapy (CBT) are recommended.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this article are grateful to the staff of the Qom MMT centers and all the participants who cooperated with compassion, honesty, and patience in this study. This study was supported by the Research Assistant of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and Health Services (Grant No. 9545).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: Conceptual and empirical foundations. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2014. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Report of the WHO expert committee on national drug policies. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Askian P, Krauss SE, Baba M, Kadir RA, Sharghi HM. Characteristics of co-dependence among wives of persons with substance use disorder in Iran. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2016;14(3):268–83. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wegman MP, Altice FL, Kaur S, Rajandaran V, Osornprasop S, Wilson D, et al. Relapse to opioid use in opioid-dependent individuals released from compulsory drug detention centres compared with those from voluntary methadone treatment centres in Malaysia: a two-arm, prospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(2):e198–e207. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30303-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seo D, Sinha R. Neuroplasticity and predictors of alcohol recovery. Alcohol Res. 2015;37(1):143–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yule AM, Martelon M, Faraone SV, Carrellas N, Wilens TE, Biederman J. Examining the association between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and substance use disorders: A familial risk analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;85:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kober H. Emotion regulation in substance use disorders. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2014. pp. 428–46. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tull MT, Berghoff CR, Wheeless LE, Cohen RT, Gratz KL. PTSD symptom severity and emotion regulation strategy use during trauma cue exposure among patients with substance use disorders: Associations with negative affect, craving, and cortisol reactivity. Behav Ther. 2018;49(1):57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Witkiewitz K, Bowen S, Douglas H, Hsu SH. Corrigendum to "Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for substance craving" [Addictive Behaviors 38 (2013) 1563-1571]. Addict Behav. 2018;82:202. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muller AE, Clausen T. Group exercise to improve quality of life among substance use disorder patients. Scand J Public Health. 2015;43(2):146–52. doi: 10.1177/1403494814561819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasareanu AR, Opsal A, Vederhus JK, Kristensen O, Clausen T. Quality of life improved following in-patient substance use disorder treatment. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:35. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0231-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magnee EH, de Weert-van Oene GH, Wijdeveld TA, Coenen AM, de Jong CA. Sleep disturbances are associated with reduced health-related quality of life in patients with substance use disorders. Am J Addict. 2015;24(6):515–22. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim DS, Reynolds MR, Feldman T, Kar S, Herrmann HC, Wang A, et al. Improved functional status and quality of life in prohibitive surgical risk patients with degenerative mitral regurgitation after transcatheter mitral valve repair. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(2):182–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strada L, Vanderplasschen W, Buchholz A, Schulte B, Muller AE, Verthein U, et al. Measuring quality of life in opioid-dependent people: a systematic review of assessment instruments. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(12):3187–200. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1674-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nantes SG, Strand V, Su J, Touma Z. Comparison of the Sensitivity to Change of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey and the Lupus Quality of Life Measure Using Various Definitions of Minimum Clinically Important Differences in Patients with Active Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2018;70(1):125–33. doi: 10.1002/acr.23240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmadi G, Sohrabi F, Borjali A, Ghaderi M, Mohseni MS. Effectiveness of emotion regulation training on mindfulness and craving in soldiers with opioid use disorder. Journal of Military Psychology. 2015;6(22):5–21. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shapiro SL, Carlson LE. The art and science of mindfulness: Integrating mindfulness into psychology and the helping professions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunning DL, Griffiths K, Kuyken W, Crane C, Foulkes L, Parker J, et al. Research review: The effects of mindfulness-based interventions on cognition and mental health in children and adolescents - a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(3):244–58. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hendershot CS, Witkiewitz K, George WH, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention for addictive behaviors. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2011;6:17. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-6-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowen S, Witkiewitz K, Clifasefi SL, Grow J, Chawla N, Hsu SH, et al. Relative efficacy of mindfulness-based relapse prevention, standard relapse prevention, and treatment as usual for substance use disorders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):547–56. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garrison KA, Pal P, Rojiani R, Dallery J, O'Malley SS, Brewer JA. A randomized controlled trial of smartphone-based mindfulness training for smoking cessation: A study protocol. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:83. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0468-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruscio AC, Muench C, Brede E, Waters AJ. Effect of brief mindfulness practice on self-reported affect, craving, and smoking: A pilot randomized controlled trial using ecological momentary assessment. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(1):64–73. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maglione MA, Maher AR, Ewing B, Colaiaco B, Newberry S, Kandrack R, et al. Efficacy of mindfulness meditation for smoking cessation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addict Behav. 2017;69:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown S, Victor B, Hicks LM, Tracy EM. Recovery support mediates the relationship between parental warmth and quality of life among women with substance use disorders. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(5):1327–35. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowen S, Chawla N, Witkiewitz K. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for addictive behaviors. In: Baer R. Mindfulness-based treatment approaches. 2nd. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2014. pp. 141–57. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gellatly R, Beck AT. Catastrophic thinking: A transdiagnostic process across psychiatric disorders. Cognit Ther Res. 2016;40(4):441–52. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohammadzadeh A, Khosravani V, Feizi R. The comparison of impulsivity and craving in stimulant-dependent, opiate-dependent and normal individuals. J Subst Abuse. 2018;23(3):312–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang P, Chen C, Yang R, Wu Y. Psychometric evaluation of health related quality of life among rural-to-urban migrants in China. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:155. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0350-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torkan B, Parsay S, Lamyian M, Kazemnejad A, Montazeri A. Postnatal quality of life in women after normal vaginal delivery and caesarean section. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yaghubi M, Zargar F, Akbari H. Comparing effectiveness of mindfulness-based relapse prevention with treatment as usual on impulsivity and relapse for methadone-treated patients: A randomized clinical trial. Addict Health. 2017;9(3):156–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang YY, Tang R, Posner MI. Mindfulness meditation improves emotion regulation and reduces drug abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;163(Suppl 1):S13–S18. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shorey RC, Elmquist J, Wolford-Clevenger C, Gawrysiak MJ, Anderson S, Stuart GL. The relationship between dispositional mindfulness, borderline personality features, and suicidal ideation in a sample of women in residential substance use treatment. Psychiatry Res. 2016;238:122–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brewer JA, Bowen S, Smith JT, Marlatt GA, Potenza MN. Mindfulness-based treatments for co-occurring depression and substance use disorders: What can we learn from the brain? Addiction. 2010;105(10):1698–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02890.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Habibi M, Imani S, Pashaei S, Zahiri Sorori M, Mirzaee J, Zare M. Effectiveness of mindfulness treatment on quality of life in opium abusers: Promotion of the mental and physical health. Health Psychology. 2013;2(5):63–81. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, Ott U. How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6(6):537–59. doi: 10.1177/1745691611419671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brewer JA, Elwafi HM, Davis JH. Craving to quit: psychological models and neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness training as treatment for addictions. Psychol Addict Behav. 2013;27(2):366–79. doi: 10.1037/a0028490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zgierska A, Rabago D, Zuelsdorff M, Coe C, Miller M, Fleming M. Mindfulness meditation for alcohol relapse prevention: A feasibility pilot study. J Addict Med. 2008;2(3):165–73. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31816f8546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cook JM, Walser RD, Kane V, Ruzek JI, Woody G. Dissemination and feasibility of a cognitive-behavioral treatment for substance use disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder in the Veterans Administration. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2006;38(1):89–92. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2006.10399831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katz D, Toner B. A systematic review of gender differences in the effectiveness of mindfulness-based treatments for substance use disorders. Mindfulness. 2013;4(4):318–31. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis DM, Hayes JA. What are the benefits of mindfulness? A practice review of psychotherapy-related research. Psychotherapy (Chic) 2011;48(2):198–208. doi: 10.1037/a0022062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gratz KL, Tull MT. Emotion regulation as a mechanism of change in acceptance- and mindfulness-based treatments. In: Baer RA, editor. Assessing mindfulness and acceptance processes in clients: Illuminating the theory and practice of change. Oakland, CA: Context Press/New Harbinger Publications; 2010. pp. 107–33. [Google Scholar]