Abstract:

Background

The Ending Homelessness in New Zealand: Housing First research programme is evaluating outcomes for people housed in a Housing First programme run by The People's Project in Hamilton, New Zealand. This baseline results paper uses administrative data to look at the scope and duration of their interactions with government services.

Methods

We linked our de-identified cohort to the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI). This database contains administrative data on most services provided by the New Zealand Government to citizens. Linkage rates in all datasets were above 90%. This paper reports on the use of government services by the cohort before being housed. We focus on the domains of health, justice and income support.

Results

The cohort of 390 people had over 200,000 recorded interactions across a range of services in their lifetime. The most common services were health, justice and welfare. The homeless cohort had used the services at rates far in excess of the general population. Unfortunately these did not prevent them from becoming homeless.

Conclusion

These preliminary findings show the homeless population have important service delivery needs and a very high level of interaction with government services. This highlights the importance of analysing the contributing factors towards homelessness; for evaluation of interventions such as Housing First, and for understanding the need for integrated systems of government policy and practice to prevent homelessness. This paper also provides the baseline for post-Housing First evaluations.

Keywords: New Zealand, Housing first, Homelessness, Service usage, Linked data

Highlights

-

•

A homeless cohort in New Zealand had a high rate of service usage leading up to engagement with Housing First services.

-

•

The cohort appeared in government linked data at higher rates than the general population.

-

•

The cohort had over 200,000 interactions with government services within the five years prior to being housed by Housing First services.

-

•

This paper shows the need for a systems-wide strategy to prevent homelessness.

1. Introduction

This paper analyses interactions between homeless people in New Zealand and government services. The baseline data presented in this paper are the service usage prior to housing of a cohort who has since received Housing First services in New Zealand. New Zealand's homeless population was estimated to number 41,705 in 2013, with 4,170 living without shelter. In that same year, one in every 100 New Zealanders did not have adequate housing on Census night (Amore, 2016). This was a rise of 15% since the 2006 Census, which in turn had risen 9% since the 2001 Census. Increased homelessness and people living without shelter in New Zealand is likely the result of an increasing lack of affordable and social housing, with a shortage of existing supply as well as affordable new builds, a rapidly-inflating property market, significant increase in demand for private rentals, and previous policy to reduce the state housing stock (Johnson, Howden-Chapman, & Eaqub, 2018). Māori, the indigenous people of New Zealand, as well as Pacific peoples, are overrepresented amongst those in severe housing deprivation (Amore, 2016), reflecting the ongoing effects of colonisation and discrimination for these communities (Groot & Peters, 2016). Correspondingly, these groups carry a greater burden of ill health, material poverty, poorer educational achievement, and shorter life expectancy (Anderson et al., 2016). Inequities in homelessness reflect the rougher end of these cumulative systemic inequities.

There is a global issue with rising homelessness, and despite some differences in context and circumstance, homelessness affects people who are already vulnerable in connected ways such as poverty (Busch-Geertsema, Culhane, & Fitzpatrick, 2016). While there are challenges unique to particular contexts (e.g. the pressure of the refugee crisis in Europe is not directly applicable to countries like New Zealand), there are global patterns of deprivation and discrimination that drive homelessness. The most effective responses to homelessness are holistic approaches that encompass all services and deliver a joined up approach (Pleace, 2017). An important step in bringing services into a holistic approach is to point out the interactions that are already occurring and the missed opportunities for prevention. Housing First is a holistic approach to homelessness services (Tsemberis, 2010). Originating in the U.S., versions of Housing First have since been implemented across North America, Europe, Australia and New Zealand (Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, 2018; Goering et al., 2014; Padgett, Henwood, & Tsemberis, 2016; Pleace, 2016). The model is premised on housing being a human right, and on the idea that complex issues are best addressed from within the stability of permanent housing (Tsemberis, 2010). There are no preconditions or barriers to entry, such as sobriety or treatment compliance requirements. Once housed, people are linked with services such as health and social welfare, with the ongoing close support of their Housing First case worker. There is strong international evidence that the Housing First approach improves outcomes, including for tenure stability and health (Padgett et al., 2016).

In response to rising homelessness, the New Zealand Government is now funding Housing First services. Both the previous National-led (centre-right, 2008–2017) and the current Labour-led (centre-left, 2017-current) governments have shown support for funding Housing First programmes. In 2017, the central government funded a pilot Housing First programme in Auckland (Adams & Minister for Social Housing, 2017b), and in 2017/18 funding was extended into other main centres across the country (Adams & Minister for Social Housing, 2017a). In the 2018 Budget the new Labour-led coalition Government announced a further expansion of funding for Housing First, both to continue to fund existing services, and to fund services in more areas (Twyford, Minister for Housing and Urban Development, 2018). Prior to government support, The People's Project (TPP) in Hamilton was the first organisation to implement the Housing First model on a large scale in New Zealand. TPP is a collaborative of community and government agencies and was largely privately-funded (McMinn, 2017; The People's Project, 2018) for the first four years.1 Hamilton, New Zealand's third-largest city, had a visible homelessness issue in its central city (Leaman, 2014). Since being established in 2014, The People's Project has been credited with a noticeable reduction in rough sleeping in Hamilton (Māori Television, 2016), and has anecdotally reported significant positive outcomes for the health and wellbeing of the people housed.

The People's Project approach follows the example of successful Housing First programmes in Canada, the U.S., Europe, and the U.K (The People's Project, 2019). Clients are engaged through a walk-in office in the central city (situated where many had been rough sleeping), by on-street outreach efforts, and referrals from government and community agencies. The service aims to assist all who come through the door, appropriate to their level of need. Staff are highly-skilled and experienced (Aspinall, 2018). By evaluating 390 of the first people housed by The People's Project, the research programme hopes to provide evidence that will support the ongoing and depoliticised funding of Housing First, by showing that investment in Housing First services is beneficial in terms of cost savings to government services, as well as in terms of the health, wellbeing and social outcomes of those who have received and are receiving Housing First services.

New Zealand is in a unique position to evaluate the efficacy of social good policies through linked administrative data available in the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI), developed and managed by Statistics NZ (Statistics New Zealand, 2017b). The IDI is the most comprehensive linked governmental dataset internationally, allowing for wide-ranging evaluation of social and governmental policies. Traditionally, these types of evaluations are best achieved through large-scale randomised controlled trials that involve significant time, resource, and cost (Howden-Chapman et al., 2007; Howden-Chapman et al., 2008; Keall et al., 2015; O'Campo et al., 2016; Stergiopoulos et al., 2015). The IDI provides a new opportunity for more efficient and far-reaching evaluations of policies or interventions as they are implemented or piloted, as well as having the potential to work alongside qualitative evaluation in new ways (Culhane, 2016). The high linkage rate that we have been able to achieve in the IDI is testament to the ability of research using the IDI to evaluate policy interventions.

Service usage prior to housing is an essential component of the story of homelessness and Housing First. This can indicate the cost of homelessness in terms of government-funded service usage (Ly & Latimer, 2015; Parsell, Peterson, & Culhane, 2016), the history of life and systemic/structural circumstances that lead towards homelessness (Pleace, 2010; Wood, Batterham, Cigdem, & Mallett, 2015) and the level, type, and complexity of need. Some rhetoric, including from previous New Zealand Governments, has framed people like those discussed in this paper as “hard to reach” (Flanagan & Hancock, 2010; McFarlane et al., 2017). This paper shows interactions with government-funded services by the cohort of 390 people who were homeless, up to the date housed. Despite many interactions with government agencies, homelessness up to this point in this cohort had not been prevented.

Previous research has shown that people experiencing homelessness - particularly chronic homelessness - are more likely to have increased interactions with government services than the general population, due to a higher level of need, and higher use of emergency and acute services. A study of psychiatric service usage in San Francisco, for example, found that people who were homeless accounted for 30% of all episodes of service, and were more likely to have multiple episodes of service and to be hospitalised after the initial visit (McNiel & Binder, 2005). Whilst this study covered a number of patients (n = 2,294), it was able to look at a period of only six months. A quasi-experimental study of 1,811 people in Eastlake in Seattle (a project-based Housing First programme) looked at cost and use of services before and after housing. The study found that in the year prior to housing, individuals who were homeless accrued a median of $4,066 per month of use costs. After the Housing First intervention, costs were offset by a mean of $2,449 per month per person in reduced service use (Larimer et al., 2009). A Philadelphia study looked at costs for psychiatric care, substance abuse treatment, and incarceration for 2,703 individuals experiencing chronic homelessness over a three year period. They found that costs totalled around $20 million annually, with an average of $7,445 per individual; 20% of the individuals accounted for 60% of the total costs, with an average annual cost of $22,372 (Poulin, Maguire, Metraux, & Culhane, 2010). In each of these studies, the cohorts studied were predominantly male.

The research programme, and its aims and methodologies, are the result of a research partnership between the University of Otago Wellington, the University of Waikato, and The People's Project (Ombler et al., 2017). The research partnership is based on the primacy of telling the story of the people housed through the work of The People's Project. This paper is an outcome of the relationship between the research partners, and reflects a shared overarching aim to improve the systemic issues that contribute to ongoing homelessness and its attendant problems.

2. Methods

The IDI links microdata about people and households sourced from government administrative data, official surveys, and selected non-governmental organisation datasets. This research database is made available in de-identified form to approved researchers for specific ‘public good’ projects. Data from different sectors and agencies is linked together probabilistically using a central dataset in the IDI called the ‘spine’ (Black, 2016). The spine is created using tax, births, and visa data and is a person-level dataset to which all datasets link, and through which datasets from different sectors (e.g. justice and education) can be linked to each other. It has a single unique identifier for every member of the target population (the ever-resident New Zealand population), which allows us to use the IDI to obtain individual level, longitudinal de-identified data. Outputs can then be generated and approved on an aggregated level to show rates and trends across government interactions for different groups.

2.1. Study population

For this research, Statistics NZ2 liaised with our community partner, The People's Project, to link their initial cohort of previously homeless people who were housed into the IDI. The People's Project supplied a dataset with the name, date of birth and National Health Identifier (NHI) together with the data of first interaction, the date housed and categorisation of homelessness type. SNZ then linked this dataset to the IDI by replacing the NHI with an encrypted identifier used across the health datasets in the IDI, and removing names and dates of birth to de-identify records. This dataset could then be linked to the unique identifier for each person in the spine, allowing for linking de-identified data across a wide range of government interactions to individuals in this group (hereafter referred to as ‘HF cohort’).3

2.2. Comparison population

The linked administrative datasets in the IDI allow for the identification of residents in New Zealand at a given time based on the individual's records of activity in the various administrative datasets (Gibb, Bycroft, & Matheson-Dunning, 2016). Specifically, this excludes all members of the usually resident population of New Zealand who had died, emigrated or otherwise had no activity in a range of administrative datasets in the 12 months before the reference date. The national population identified in this way is the Estimated Resident Population (ERP). Using a reference date of 31 June 2016, we restricted the group to those with full demographic information, who were in the same age range as our population and took a one percent random subsample of this group. We have then used this subsample (n = 33,666) as a national comparison group in our analysis.

2.3. Reference period

The 390 individuals in our cohort were clients of The People's Project between October 2014 and June 2017, with a median date when first housed of 9 June 2016. To identify pre-housed patterns and trends, all interactions across different government services prior to the date when each individual was first housed were examined. In order to make comparisons about rates of service usage over a similar time period for the ERP, the median date housed of 9 June 2016 was used as an arbitrary baseline for this group. For both the HF cohort and the ERP, the time between each individual's baseline date and the date of any linked events prior to this was found. In this way, the date first housed for the HF cohort and the median date housed for the ERP is what is represented as time 0 in figures included in the Results section.

2.4. Datasets

A brief overview of the 11 datasets we have used to compare the extent and usage of different types of government services is given below. These have been grouped together according to one of three key dataset domains: health, justice, and social development (i.e. welfare services) and tax. Full information on all datasets is available from Statistics New Zealand (Statistics New Zealand, 2017a). The demographic information we present in Table 1 was obtained using a composite table in the IDI. This applies Statistics NZ standard rules to derive from the IDI the most reliable estimate of a person's sex, birth month and year, and ethnicity.

Table 1.

Data sources.

| Dataset domain: Health | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hospitalisations | Discharge and event data about all publicly-funded hospital admission events. There is a single record for each inpatient or day patient discharge, although transfers within or between hospitals are recorded as separate events. |

| 2 | Injuries | All claims made due to a unique work-related or non-work related accident. These claim records are managed by the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC), a government-owned universal no-fault injury compensation service in NZ. Multiple instances of a claim being lodged for the same accident were counted once. |

| 3 | Pharmaceuticals | Information on all subsidised pharmaceutical dispensings issued through NZ pharmacists. Multiple prescriptions on the same script and repeat prescriptions are counted as separate instances of a pharmaceutical being dispensed. |

| 4 | Mental health and addiction service usage | Records of the contacts, activities, and services for referrals to secondary mental health and addiction service providers. These include assessments, inpatient and outpatient bednights, and treatment. There is full coverage for nationally funded service providers, and selected coverage of non-government organisations. Multiple activities provided as part of the service for any one referral are counted separately. |

| Dataset domain: Justice | ||

| 5 | Alleged criminal offences | Records of court and non-court proceedings against alleged offenders by Police, as described in the NZ Police National Recording Standard (New Zealand Police, 2016). Multiple offences from a single criminal incident are counted separately. |

| 6 | Sentencing and remand data | All records from the national department that manages corrections. These relate to custodial and community sentences imposed by judges, as well as people serving custodial remand while they await trial or sentencing. Orders imposed by the court for prisoners upon early release from custodial sentences are also included. Remand, sentences, and parole board orders that relate to each other are recorded as separate events. |

| 7 | Criminal court charges laid | Ministry of Justice records for all criminal charges filed by Police, Corrections, local authorities or a number of other government agencies. A single charge record usually refers to one offence charge. All charges with linking information are counted, including those that were withdrawn or not proceeded with for any other reason.4 |

| Dataset domain: Social development and tax | ||

| 8 | Notification of care and protection concern (as a child) | This dataset is a records of reports made to Child, Youth and Family (CYF5) or Police where there is concern about the care or behaviour of a child. Each notification of concern for a child or young person's behaviour or care is included. |

| 9 | Finding of abuse (as a child) | These records detail the assessments made by a Child, Youth and Family social worker about whether or not a child (defined as 0 to 16) has been subject to abuse. |

| 10 | Main benefit assistance | Working-age social welfare records for main benefits relate to the commencement of a new administrative spell as the single or primary recipient of main benefit assistance, as well as any associated partners. Main working-age benefits support those that are unemployed, in caring roles, as well as those living with a health condition or disability or in other need of welfare support. |

| 11 | Reported income from wages and salaries | We used data provided from the Inland Revenue database to identify taxed earnings from wages and salaries on a monthly basis. (Not counted in total events). |

| 12 | Recorded income from main benefit assistance | Data from the Inland Revenue database also records aggregate benefit payments for main working-age welfare entitlements on a monthly basis. (Not counted in total events). |

2.5. Analysis

Unless otherwise specified, all available data were used for linking to individuals in the HF cohort as well as our control population, and to compare coverage in different dataset areas between the two groups and assess rates of service usage. The exception to this is the summary statistics of event rates for notifications and findings data from CYF (datasets 8 and 9 in Table 1, respectively), where we have chosen to restrict the study populations to those born after 1986 in both instances in an attempt to minimise the confounding effect of age on the reference period for these datasets. All summary statistics in both of these instances are derived from linked datasets of events that belong to only those members of each population group that were at most 5 years old in 1991. This excludes older members of each population that would have been outside of CYF's duty of care when the dataset reference period began. Numbers are exact for the HF cohort and for the ERP. The results are presented as means, quintiles, and histograms. The histograms show the rate of events in each of the 15 years before baseline for both HF and ERP (superimposed).

2.6. Ethics and confidentiality measures

All People's Project cohort participants gave informed consent to record linking and research into past and future usage of government services. Ethical approval was given by the University of Otago Human Research Ethics Committee, reference HD16/049. All analysis was done on de-identified records in a secure Datalab environment. As part of the privacy, confidentiality, and security measures required for research using the IDI, all values reported in this paper have been approved by SNZ as meeting the necessary confidentiality rules. Any count or associated statistic with an underlying count of people or events below six (or 20 for a mean) are suppressed. All values are randomly rounded to base three and summary statistics have been derived from these rounded counts.

3. Results

This section first gives an overview of key demographics of the HF cohort (n = 390) and the ERP (n = 33,666). It then presents results of the data linking; an overview of rates of service usage; and some analysis of selected datasets.

The demographics of the HF cohort and ERP are shown in Table 2. The HF cohort has a higher proportion of females (53.8%) than males (46.2%), with approximately 50% aged between 26 and 44 years. There was a much higher proportion identifying as Māori (73.1%) than in the general national (14.5%) or Hamilton City (21.3%) populations.

Table 2.

Demographics of the Housing First and Estimated Resident Population cohorts.

| Variable | Relative percentage (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Housing First cohort (n = 390) | Estimated Resident Population (n = 33,666) | ||

| Sex | Female | 53.8 | 50.2 |

| Male | 46.2 | 49.9 | |

| Age (years) | Under 25 | 15.4 | 14.8 |

| 25–44 | 51.5 | 36.1 | |

| 45–64 | 32.3 | 34.4 | |

| 65+ | ≤ 1.5 | 14.7 | |

| Ethnicity (total response, multiple ethnicities allowed) | Māori | 73.1 | 14.2 |

| European | 40.8 | 70.4 | |

| Pacific | 6.9 | 6.6 | |

| Asian | 3.1 | 14.0 | |

| Middle Eastern, Latin American, African (MELAA) | 4.6 | 2.4 | |

| Other | ≤ 1.5 | 1.7 |

We examined the rate of data linking in each of the three domains of health, justice, and social development/tax (Table 3). Despite this cohort being commonly described as a “hard to reach” group, Table 3 demonstrates that higher proportions of the HF cohort than the ERP appear in each domain. For the areas such as justice where only part of the population have any interaction with the government, the HF cohort are much more likely to be linked than the controls. Overall, 97% of the HF cohort was in over five of the 11 datasets, compared to 44% for the ERP.

Table 3.

Numbers appearing in administrative datasets for Housing First population and Estimated Resident Population.

| % of population linked to at least one event type in each dataset domain | Housing First | Estimated Resident Population |

|---|---|---|

| Health | 99.2% | 96.2% |

| Justice | 83.8% | 23.6% |

| Social Development and Tax | 97.7% | 92.5% |

The HF cohort had a high and sustained use of all government services (Table 4). These data do not equip us to pinpoint when homelessness has occurred in the period leading up to engaging with Housing First services, but the trend clearly suggests increasing vulnerability.6 The most common service was for pharmaceuticals (with antidepressants and antipsychotics the most common type of pharmaceutical given in the five years before baseline), followed by benefits and mental health services. For mental health services and justice sector services the cohort had over ten times the rate of service usage in the last five years than the ERP. There were also much higher rates of welfare, pharmaceuticals and hospitalizations and a relatively slight increase in injury claims. Even with the limited historical data on child abuse, there is a strong suggestion that the Housing First cohort suffered an elevated level of abuse compared to the ERP.

Table 4.

Comparative rates of service usage.

| Data domain | Earliest date records available from | Data source | Total Occurrences (HF)a | Mean from all available data (HF) | Mean in 5 years before housed (HF) | Median (HF) in 5 years before housed (HF) | 75th percentile (HF) in 5 years before housed (HF) | Mean from all available data (ERP)b | Mean in 5 years before 09-June-2016 (ERP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | 1988 | Hospitalisations | 4,317 | 11.1 | 3.2 | 2 | 4.0 | 3.3 | 0.9 |

| 1994 | Injuries | 3,660 | 9.4 | 2.2 | 1 | 3.0 | 6.7 | 1.7 | |

| 2005 | Pharmaceuticals | 88,131 | 226.0 | 141.6 | 29 | 89.5 | 103.3 | 59.1 | |

| 2008 | Mental Health - Outpatient eventsc | 37,299 | 95.6 | 72.5 | 6 | 52 | 7.9 | 5.9 | |

| 2008 | Mental Health - Inpatient periods | 399 | 1.0 | 0.79 | 0 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.03 | |

| Justice | 2009 | Police offence | 1,980 | 5.1 | 3.7 | 1 | 5.8 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| 1990 | Criminal charges | 7,395 | 19.0 | 3.5 | 1 | 5.0 | 1.5 | 0.3 | |

| 1998 | Sentencing and remand | 11,616 | 29.8 | 9.1 | 0 | 6.0 | 2.2 | 0.7 | |

| Social Development | 1999 | Months in which tax paid on wages and salaries | 15,114 | 38.8 | 9.2 | 2 | 12.8 | 87.5 | 29.9 |

| 1993 | Months in which a benefit was received | 44,469 | 114.0 | 41.9 | 49.5 | 60.0 | 19.3 | 6.1 | |

| 1993 | New spells on a benefit | 4,515 | 11.6 | 3.3 | 3 | 5 | 2.1 | 0.5 | |

| 1991 | Notification of care and protection concern (as a child)d | 660 | 5.9 | NA | NA | NA | 0.7 | NA | |

| 1991 | Finding of abuse (as a child)d | 252 | 2.3 | NA | NA | NA | 0.2 | NA |

HF refers to Housing First cohort.

ERP refers to Estimated Resident Population.

Both inpatient and outpatient rates of mental health and addiction service usage have been found from a single source of national-level data about contacts, activities and services for secondary-care mental health and addiction service providers.

Restricted to those born after 1986 (n = 111 for HF).

While service usage was higher for the HF cohort as a whole this is not evenly distributed amongst the individuals, with 25% of the cohort having less than the average usage of most services and some users having extreme levels of service usage.

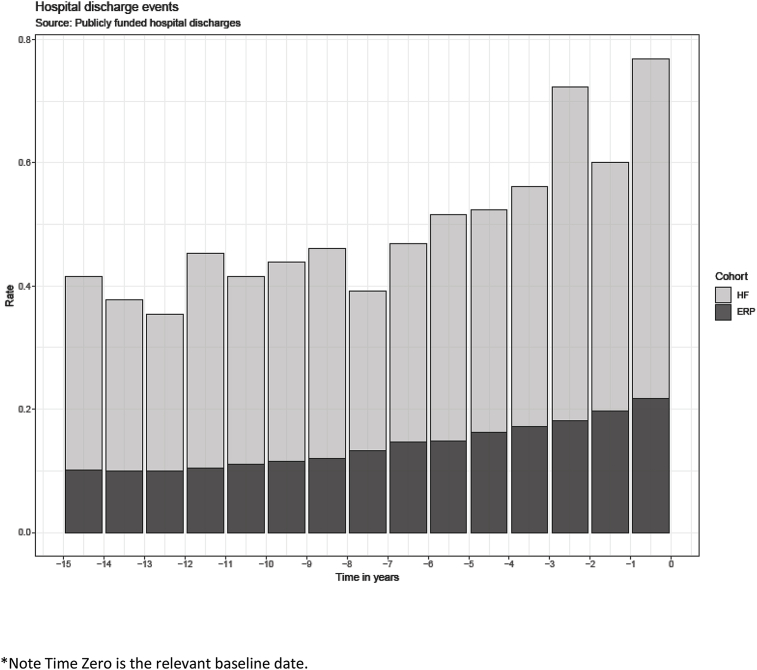

For some datasets, such as for hospitalisations and benefit receipt, a long history prior to baseline was available (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). These datasets showed a high and increasing level of service usage over a long time period compared to the ERP. For hospitalisations 375 out of the 390 (96%) in the cohort population had at least one recorded hospitalisation in their lives prior to being housed. Overall the cohort has a high ongoing rate of hospitalisations for a long period of time. This rose steeply over the last decade before they were housed by The People's Project.

Fig. 1.

Hospitalisation history at baseline.

*Note Time Zero is the relevant baseline date.

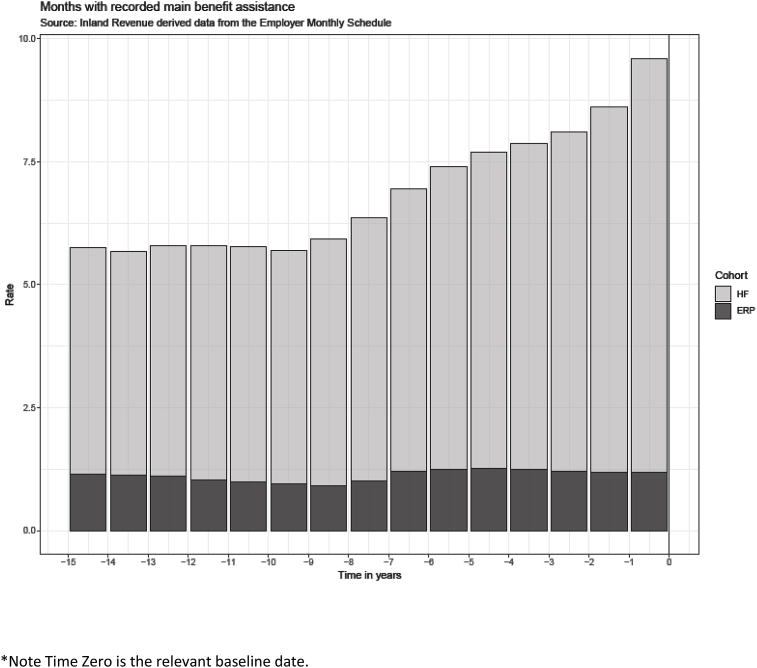

Fig. 2.

Benefit history at baseline

*Note Time Zero is the relevant baseline date.

Like hospitalisations, there is a detailed history of benefit receipt for the HF cohort. This showed a high level of benefit usage with many repeated periods on benefits; for some the payments for income support are at least 18 years before the date people were housed. There is a clear rise in the number of interactions for the decade before people were housed, which peaked in the final year prior to the Housing First intervention. In the 5 years before baseline, the cohort had earned $8,277,639 in wages and salaries and were paid $19,305,078 in benefits with 54% having paid tax on wages and salaries and 96% having received benefits. The average monthly income for those who had taxable earnings recorded during this time was $2,307 for HF compared to $4,480 among the ERP. For benefits, the average monthly income was between $1,100–1,200 for both HF and ERP.

Overall, our results show a high level of interactions with government agencies preceding homelessness. In the five years before they were housed by The People's Project, the HF cohort had 93,615 recorded interactions with government services, and had spent 10,440 bed nights in mental health facilities. Despite these interactions, few were able to be officially linked to housing services and in cases where they were, this may have been to temporary or emergency accommodation. That all 390 required housing after so much interaction with government services reveals a lack of a systems approach that ultimately fails some of our most vulnerable.

4. Discussion

This research shows that high quality administrative datasets can provide insight into the unmet needs of vulnerable populations. These preliminary findings are significant because we demonstrate how a cohort that is supposedly ‘hard to reach' is highly traceable across a range of government records. The HF cohort is not ‘hard-to-reach’ with over 200,000 individual recorded and linked interactions with government services, an average of over 500 each. Rather, they are likely victims of inadequate systems.

The findings in this paper echo those of a 2015 report by New Zealand's Productivity Commission, which found that for people with complex problems, government services were poorly coordinated, leading to inefficient use of government funds, and exacerbation of issues for the people concerned. They found that this was particularly true for people who were the most disadvantaged (New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2015, p. 2). People who are facing multiple challenges have been required to navigate a siloed system, in which each service only attends to a particular need, and in which there are few referrals between services. The Commission's report recommended that people with severely complex needs require a central navigator to assist them to access the services they are entitled to (New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2015, p. 17). The Housing First approach attends to this gap by having a case worker liaise with multiple agencies alongside, or on behalf of, the client. However, there are few mechanisms in current New Zealand policy that allow for the navigation and collaboration across these siloed systems prior to a crisis such as homelessness.

The amount and extent of service usage before being housed is an essential component of the story of homelessness and the policy solution of Housing First. The logic of Housing First emphasises the social cost of not having effective systems in place to prevent and address homelessness. Despite high government inputs, needs for this population have not been met. This evidence of inadequate systems integration provides a prompt for government services to evolve to better meet the needs of this population. The concept of “joined-up government” has dominated public policy discourse for many years; it refers to the idea that implementing policy programmes necessitates government departments to collaborate in order for policy to succeed (Exworthy & Hunter, 2011). The Productivity Commission report noted that previous efforts to better coordinate between agencies had been focused at Ministerial and Chief Executive levels (New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2015, p. 8), yet it also argued that top-down approaches were particularly inappropriate for people with complex problems who require a more tailored approach (New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2015, p. 10).

The demographics of the HF cohort mostly reflected already-understood characteristics regarding homelessness, with one notable exception being a higher number of females than males. Consistent with well-known inequities, there was an over-representation of Māori amongst the cohort experiencing homelessness. The ongoing effects of colonialism and discrimination are evident in this over-representation, a situation for which the New Zealand Government has a responsibility for as part of its Treaty of Waitangi obligations (Orange). New Zealand is unique in this sense, with existing legal precedents and frameworks to enable compensation where there have been found to be breaches of The Treaty by the Crown against Māori. At the time of writing, a Kaupapa (thematic) Inquiry on housing is being undertaken by the Waitangi Tribunal, a standing commission of inquiry which makes recommendations to Government on Treaty claims (Waitangi Tribunal, 2015). The findings of this inquiry may have implications for homelessness. Pacific peoples in the HF cohort matched the ERP, but the rate of 6.9% is slightly higher than the Hamilton Pacific population at 5.1% (Statistics New Zealand, 2013).

One notable demographic characteristic was the greater number of females in the HF cohort. Rough sleeping populations are often portrayed or understood as being predominantly male,7 however research on the severely deprived housing population in New Zealand suggests that females may be more likely to be in ‘hidden homelessness’, staying with family or friends, rather than more visible places such as the street or city night shelters (Amore, Viggers, Baker, & Howden-Chapman, 2013). It is possible that the higher level of females in the HF cohort is due to inadvertent selection or outreach bias, or more active seeking of support by women, though without more evidence it is difficult to speculate. This reinforces suggestions that female homelessness is poorly-understood. Further research is needed to look into any differences between females and males regarding trajectories into homelessness, and experience of housing services.

The HF cohort's most common interaction with government was with the health and mental health systems, with rates vastly in excess of the general population, despite being younger. This indicates the need for the health system to take active responsibility for the social determinants of health including housing. Despite having universal publicly-funded healthcare, a key system failure is that there has been no referral pathway from health to housing services, despite the District Health Boards being created with the purpose of integrating health in the community (New Zealand Parliament, 2000). Such systems require a means to screen for and identify homelessness and/or risk of homelessness, and provide coordinated referral points to local housing and housing support service providers. Previous research in New Zealand has shown that people with severe mental illness also experience poorer physical health and premature death from comorbid conditions such as cancer (Cunningham, 2016; Paterson et al., 2018). Our cohort has high mental health needs, so may also be disadvantaged regarding comorbidity. Interestingly, extensive welfare reforms in 2013 introduced obligations for beneficiaries with health condition and disability deferments for unemployment-related benefits to visit a doctor every four weeks for the first two months, then every thirteen weeks, in order to remain eligible (Work and Income New Zealand, 2018). This has likely increased interactions with general medical practitioners and has potentially had the effect of driving higher prescription rates. Yet, high rates of prescriptions for pharmaceuticals do not address the underlying and environmental drivers of poor health and homelessness. We make the point in this paper that the rate of prescriptions dispensed to the HF cohort prior to being housed shows they have a very high level of need, and that secure housing should be considered an essential part of a treatment protocol.

The HF cohort also had high rates of interaction with the justice system. This is consistent with international experience, in which homelessness and higher rates of incarceration are linked. Time spent in the justice system has ramifications for housing stability. Even short periods in prison can lead to leases being discontinued, and there is no clear policy of ensuring permanent housing for those leaving prison. People who are newly-released from prison are often reliant on temporary, emergency, or inadequate accommodation (such as poor-quality boarding houses), and are vulnerable to added discrimination and lack of opportunities. In New Zealand, consistent with many examples internationally (Jeffries & Bond, 2012), the indigenous Māori population is over-represented in those incarcerated, with around 51% of the prison population being Māori compared to 15% of the total population8(Department of Corrections, 2018; Workman & McIntosh, 2013). Moreover, Māori are over-represented at all stages of the justice system, including being apprehended, prosecuted, and convicted at higher rates (Morrison, 2009; Statistics New Zealand, 2018). The types of need present in the prison population also indicate high need, with 91% of prisoners having a diagnosis for mental health or addiction problems (Indig, Gear, & Wilhelm, 2016), and high rates as victims of abuse (Gluckman, 2018). This points to a need for the justice system to work closely with the health and social development systems to ensure that people are well-supported during and after prison-time, and ultimately to prevent high rates of imprisonment.

Reducing poverty is an important factor in reducing homelessness. Homelessness results from, and causes, a multitude of factors of which poverty is a central element (Gaetz, Donaldson, Richter, & Gulliver, 2013). In a context such as New Zealand with a centrally-funded health system, the effects of poverty are a significant burden on the health budget, manifesting in part in preventable conditions related to a lack of minimally-acceptable housing conditions (Oliver et al., 2018). The state welfare system has moved towards a more obligation-heavy system in recent years, and benefit payments have not kept pace with the cost of living (Boston, 2013; O'Brien, 2013). Simultaneously, there is a high rate of ‘working poor’ (Ministry of Social Development, 2017). As a result, more of our most vulnerable are living in poverty, in very poor housing conditions, and are at risk for homelessness. The current government has committed to reducing poverty, with a particular focus on children (Ardern, 2018). Investment in reducing poverty and economic inequality, as well as addressing the quantity and quality of the housing supply, will reduce the risk of homelessness (Shinn, 2007), and will improve wellbeing.

The story inferred by these results is one of slippage in between government services, reflecting poor linkage between agencies, and a lack of mechanisms by which to address complexity (New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2015). It is clear that homeless people are looking for help and that this help has not been provided (Tsemberis, 2010). As a cohort this group has had high needs over the entire time-frame of available data. Health and benefit data shows that this group has needed high levels of support going back over 20 years before they were housed. This high level of need worsens over the long time-frame presented, and rises rapidly in the approximately five years before being housed. This indicates a substantial level of need, and opportunity for better-integrated systems across the broad categories of health, justice and social development. The system evident in our results is a siloed approach, which does not address complex needs, and is not equipped to respond to environmental and social determinants of poorer outcomes. The international literature on responses to homelessness strongly supports more holistic systems-integrative approaches, enacted earlier, which have the opportunity to enhance well-being and resilience before homelessness occurs (Turner, 2014; Worton et al., 2017).

International examples of evaluations of Housing First have demonstrated a strong evidence base. These results also demonstrate the ability of the IDI to enable effective cross-government evaluation of policies and interventions. We have been able to establish a high rate of linkage into the IDI's main spine, as well as access a wide range of longitudinal government data. This research adds substantially to the evidence on the cost of homelessness to government and to wellbeing.

4.1. Limitations

Administrative data are used, and while for the 390 people in the HF cohort we were able to find 219,807 items listed, this is likely to be an underestimate of the true lifetime need of the cohort. Data will have been missed due to lack of records or poor linking with potentially some false positives. Mental health data in particular have a variable standard of reporting, underestimating interactions. We are unable to ascertain how long or how often people have been homeless using these data. It is possible that the higher rates of service usage in the years prior to being housed reflect a crisis point.

4.2. Future work

Future work is needed to see if Housing First has delivered a broad-based change in usage of government services. It will of course take time for changes to be apparent in the administrative data. The next research steps are to find appropriate controls and compare the change in interactions between the intervention and control groups.

5. Conclusion

This paper highlights the consequences and some potential drivers of homelessness, and builds on a now large body of work that shows housing is a key determinant of health, justice and social development outcomes. These in turn directly affect economic and housing security. Government systems therefore need to react to these interconnected problems in a systematic way that includes housing as a key component. Housing First is likely to be a crucial element in addressing chronic homelessness in New Zealand, but a systems-wide strategy is needed to prevent future homelessness, and to ensure that complex needs are properly addressed in government services. This story is not unique to New Zealand, and where wide-ranging and well-supported strategic approaches have been implemented, there have been significant reductions in homelessness, and improvements in wellbeing (Pleace, 2017). The data presented here add to international evidence around the drivers and ramifications of homelessness. Despite differences between countries, in terms of particular challenges, homeless demographics, and housing and types of welfare systems, this is a familiar story of silos over systems. This research therefore adds to the international evidence that indicates the importance of integrated approaches to addressing the complex needs of those experiencing chronic homelessness, with an emphasis on housing.

Funding

This paper was supported by funding from the New Zealand Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment, Endeavour Fund.

Disclaimer

The results in this paper are not official statistics. They have been created for research purposes from the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI), managed by Statistics New Zealand. The opinions, findings, recommendations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are those of the authors, not Statistics NZ.

Access to the anonymised data used in this study was provided by Statistics NZ under the security and confidentiality provisions of the Statistics Act 1975. Only people authorised by the Statistics Act 1975 are allowed to see data about a particular person, household, business, or organisation, and the results in this paper have been confidentialised to protect these groups from identification and to keep their data safe. Careful consideration has been given to the privacy, security, and confidentiality issues associated with using administrative and survey data in the IDI. Further detail can be found in the Privacy impact assessment for the Integrated Data Infrastructure available from www.stats.govt.nz.

The results are based in part on tax data supplied by Inland Revenue to Statistics NZ under the Tax Administration Act 1994. This tax data must be used only for statistical purposes, and no individual information may be published or disclosed in any other form, or provided to Inland Revenue for administrative or regulatory purposes. Any person who has had access to the unit record data has certified that they have been shown, have read, and have understood section 81 of the Tax Administration Act 1994, which relates to secrecy. Any discussion of data limitations or weaknesses is in the context of using the IDI for statistical purposes, and is not related to the data's ability to support Inland Revenue's core operational requirements.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the 390 individuals that are discussed in this paper, each of whom has their own unique story to tell. We also acknowledge the staff of The People's Project for their invaluable role. Without their permission and support this work would not be possible. Ngā mihi nui.

Footnotes

In December 2018 The People's Project was contracted by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development to deliver Housing First services in Hamilton.

Statistics NZ is the New Zealand Government's central statistics agency.

The People's Project data is available for research and evaluation use on the IDI, provided the applicant is approved by The People's Project. This applies to government agencies as well as external researchers.

Court suppression orders prevent the linking of charges with name suppression to identities in the IDI. This suppression affects around 2% of charges, primarily for sexual offences and homicide and those with particular charge outcome types.

Child, Youth and Family was changed to Oranga Tamariki – Ministry for Children in 2017. In this paper we refer to it as CYF, given that the data we are presenting were predominantly collected under the ministry known as CYF.

Identification of homelessness in national statistics is currently in development, through a research partnership between He Kainga Oranga/Housing and Health Research Programme and Statistics New Zealand.

For example, see (Bretherton, 2017; Homeless Hub, 2018; Homelessness Australia, 2016; Schneider, Chamberlain, & Hodgetts, 2010):

This ethnic disparity is more pronounced for women, with Māori women making up 63% of the female prison population.

References

- Adams A., Minister for Social Housing Helping more rough sleepers into homes. 2017. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/helping-more-rough-sleepers-homes [Press release]. Retrieved from.

- Adams A., Minister for Social Housing Housing First launches to help Auckland's homeless. 2017. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/housing-first-launches-help-auckland%E2%80%99s-homeless [Press release]. Retrieved from.

- Amore K. Severe housing deprivation in Aotearoa/New Zealand 2001-2013. 2016. http://www.healthyhousing.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Severe-housing-deprivation-in-Aotearoa-2001-2013-1.pdf Retrieved from.

- Amore K., Viggers H., Baker M.G., Howden-Chapman P. Severe housing deprivation: The problem and its measurement. 2013. www.statisphere.govt.nz Retrieved from.

- Anderson I., Robson B., Connolly M., Al-Yaman F., Bjertness E., King A. Indigenous and tribal peoples' health (the lancet–lowitja Institute global collaboration): A population study. The Lancet. 2016;388(10040):131–157. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00345-7. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673616003457 Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardern J. Taking action to reduce child poverty. 2018. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/taking-action-reduce-child-poverty [Press release], Retrieved from.

- Aspinall C. C. Aspinall; Unpublished: 2018. Key informant interview/interviewer. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Housing, Urban Research Institute What is the Housing First model and how does it help those experiencing homelessness? 2018, 25 May. https://www.ahuri.edu.au/policy/ahuri-briefs/what-is-the-housing-first-model Retrieved from.

- Black A. The IDI prototype spine's creation and coverage. 2016. www.stats.govt.nz Retrieved from.

- Boston J. The challenge of securing durable reductions in child poverty in New Zealand. Policy Quarterly. 2013;9(2):8. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton J. Recosnidering gender in homelessness. European Journal of Homelessness. 2017;11(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Busch-Geertsema V., Culhane D., Fitzpatrick S. Developing a global framework for conceptualising and measuring homelessness. Habitat International. 2016;55:124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Culhane D. The potential of linked administrative data for advancing homelessness research and policy. European Journal of Homelessness. 2016;10(3):109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham R. University of Otago; 2016. Cancer in the context of severe mental illness in New Zealand: An epidemiological study. (Doctor of Philosophy)http://hdl.handle.net/10523/6574 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Corrections Prison facts and statistics - June 2018. 2018. https://www.corrections.govt.nz/resources/research_and_statistics/quarterly_prison_statistics/prison_stats_june_2018.html#ethnicity Retrieved from.

- Exworthy M., Hunter D.J. The challenge of joined-up government in tackling health inequalities. International Journal of Public Administration. 2011;34(4):201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan S.M., Hancock B. Reaching the hard to reach' - lessons learned from the VCS (voluntary and community sector): A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research. 2010;10 doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaetz S., Donaldson J., Richter T., Gulliver T. The state of homelessness in Canada. 2013. http://homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/SOHC2103.pdf Retrieved from.

- Gibb S., Bycroft C., Matheson-Dunning N. Identifying the New Zealand resident population in the integrated data infrastructure (IDI) 2016. www.stats.govt.nz Retrieved from.

- Gluckman P. Using evidence to build a better justice system: The challenge of rising prison costs. 2018. https://www.pmcsa.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/Using-evidence-to-build-a-better-justice-system.pdf Retrieved from.

- Goering P., Veldhuizen S., Watson A., Adair C., Kopp B., Latimer E.…Aubry T. National at home/chez soi final report. 2014. http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca Retrieved from Calgary:

- Groot S., Peters E.J. Indigenous homelessness: New Zealand context. In: Peters E.J., Christensen J., editors. Indigenous homelessness: Perspectives from Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. University of Manitoba Press; Canada: 2016. pp. 323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Homeless Hub Single men. 2018. https://www.homelesshub.ca/about-homelessness/population-specific/single-men Retrieved from.

- Homelessness Australia Homelessness and men. 2016. https://www.homelessnessaustralia.org.au/sites/homelessnessaus/files/2017-07/Homelessness%20and%20men.pdf Retrieved from.

- Howden-Chapman P., Matheson A., Crane J., Viggers H., Cunningham M., Blakely T.…Davie G. Effect of insulating existing houses on health inequality: Cluster randomised study in the community. British Medical Journal. 2007;334(460) doi: 10.1136/bmj.39070.573032.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howden-Chapman P., Pierse N., Nicholls S., Gillespie-Bennett J., Viggers H., Cunningham M.…Crane J. Effects of improved home heating on asthma in community dwelling children: Randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal. 2008;337(a1411) doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indig D., Gear C., Wilhelm K. Comorbid substance use disorders and mental health disorders among New Zealand prisoners. 2016. https://www.corrections.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/846362/Comorbid_substance_use_disorders_and_mental_health_disorders_among_NZ_prisoners_June_2016_final.pdf Retrieved from.

- Jeffries S., Bond C.E.W. The impact of indigenous status on adult sentencing: A review of the statistical research literature from the United States, Canada, and Australia. Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice. 2012;10(3):223–243. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A., Howden-Chapman P., Eaqub S. A stocktake of New Zealand's housing. 2018. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2018-02/A%20Stocktake%20Of%20New%20Zealand's%20Housing.pdf Retrieved from Wellington:

- Keall M., Pierse N., Howden-Chapman P., Cunningham C., Cunningham M., Guria J. Home modifications to reduce injuries from falls in the home injury prevention intervention (HIPI) study: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2015;385(9964):231–238. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer M.E., Malone D.K., Garner M.D., Atkins D.C., Burlingham B., Lonczak H.S.…Marlatt G.A. Health care and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301(13):1349–1357. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaman A. Waikato Times; 2014. September 4). Julie's big clean-up.http://www.stuff.co.nz/waikato-times/news/10457338/Julies-big-clean-up Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Ly A., Latimer E. Housing first impact on costs and associated cost offsets: A review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;60(11):475–487. doi: 10.1177/070674371506001103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane J., Solomon J.P., Caddick L., Cameron S., Briggs B., Jera M.…Dalzell D.A. The Voices of People in hard-to-reach communities. 2017. https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/what-we-can-do/providers/building-financial-capability/cultural-and-social-inclusion/the-voices-of-people-in-hard-to-reach-communities.pdf Retrieved from Wellington:

- McMinn C. The role of local government in a homeless response, the People's project: A collaborative community response to rough sleepers in Hamilton. Parity. 2017;30(8):39–40. [Google Scholar]

- McNiel D.E., Binder R.L. Psychiatric emergency service use and homelessness, mental disorder, and violence. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(6):699–704. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.6.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Social Development Briefing for incoming minister: Social development. 2017. https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/corporate/bims/2017/social-development-bim-2017.pdf Retrieved from.

- Morrison B. Identifying and responding to bias in the criminal justice system: A review of international and new Zealand research. 2009. https://www.justice.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Publications/Identifying-and-responding-to-bias-in-the-criminal-justice-system.pdf Retrieved from.

- New Zealand Parliament New Zealand public health and disability Act 2000. 2000. http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2000/0091/latest/DLM80051.html Retrieved from.

- New Zealand Police Data and staistics user guides. 2016. http://www.police.govt.nz/about-us/publication/data-and-statistics-user-guides Retrieved from.

- New Zealand Productivity Commission More effective social services. 2015. https://www.productivity.govt.nz/sites/default/files/social-services-final-report-main.pdf Retrieved from.

- O'Brien M. A better welfare system. In: Rashbrooke M., editor. Inequality: A New Zealand crisis. Bridget Williams Books; Wellington: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- O'Campo P., Stergiopoulos V., Nir P., Levy M., Misir V., Chum A.…Hwang S. W. q. How did a housing first intervention improve health and social outcomes among homeless adults with mental illness in toronto? Two-year outcomes from a randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver J., Foster T., Kvalsvig A., Williamson D., Baker M., Pierse N. Risk of rehospitalisation and death for vulnerable New Zealand children. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2018;103(4):327–334. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-312671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ombler J., Atatoa-Carr P., Nelson J., Howden-Chapman P., Lawson Te-Aho K., Fariu-Ariki P.…Pierse N. Ending homelessness in New Zealand: Housing first research programme. Parity. 2017;30(10):5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Orange C. Treaty of Waitangi. https://teara.govt.nz/en/treaty-of-waitangi/page-1 Retrieved from.

- Padgett D.K., Henwood B.F., Tsemberis S.J. Oxford University Press; New York: 2016. Housing First: Ending homelessness, transforming systems, and changing lives. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsell C., Peterson M., Culhane D. Cost offsets of supportive housing: Evidence for social work. British Journal of Social Work. 2016;47(5) [Google Scholar]

- Paterson R., Durie M., Disley B., Rangihuna D., Tiatia-Seath J., Tualamali'i J. He Ara Oranga: Report of the government inquiry into mental health and addiction. 2018. https://mentalhealth.inquiry.govt.nz/assets/Summary-reports/He-Ara-Oranga.pdf Retrieved from.

- Pleace N. The new consensus, the old consensus and the provision of services for people sleeping rough. Housing Studies. 2010;15(4):581–594. [Google Scholar]

- Pleace N. Housing first guide: Europe. 2016. https://housingfirsteurope.eu/assets/files/2017/03/HFG_full_Digital.pdf Retrieved from U.K.

- Pleace N. The Action Plan for Preventing Homelessness in Finland 2016-2019: The culmination of an integrated strategy to end homelessness? European Journal of Homelessness. 2017;11(2) [Google Scholar]

- Poulin S.R., Maguire M., Metraux S., Culhane D. Service use and costs for persons experiencing chronic homelessness in Philadelphia: A population-based study. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61(11):1093–1098. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.11.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider B., Chamberlain K., Hodgetts D. Representations of homelessness in four Canadian newspapers: Regulation, control, and social order. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare. 2010;37(4) https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3564&context=jssw Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Shinn M. International homelessness: Policy, socio-cultural, and individual perspectives. Journal of Social Issues. 2007;63(3) [Google Scholar]

- Statistics New Zealand 2013 Census: QuickStats about Hamilton city. 2013. http://archive.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/profile-and-summary-reports/quickstats-about-a-place.aspx?request_value=13702&parent_id=13631&tabname=&sc_device=pdf Retrieved from.

- Statistics New Zealand Data in the IDI. 2017. http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/snapshots-of-nz/integrated-data-infrastructure/idi-data.aspx Retrieved from.

- Statistics New Zealand Integrated data infrastructure. 2017. http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/snapshots-of-nz/integrated-data-infrastructure.aspx Retrieved from.

- Statistics New Zealand Adults convicted in court by sentence type - most serious offence fiscal year: Ethnicity. 2018. http://nzdotstat.stats.govt.nz/wbos/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TABLECODE7373# Retrieved from.

- Stergiopoulos V., Gozdzik A., Misir V., Skosireva A., Connelly J., Sarang A.…McKenzie K. Effectiveness of housing first with intensive case management in an ethnically diverse sample of homeless adults with mental illness: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2015;10(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Television M. The People's project' drastically reduces rough sleeping in Hamilton. Māori television: Online news - rereātea. 2016, 16 December. https://www.maoritelevision.com/news/regional/peoples-project-drastically-reduces-rough-sleeping-hamilton Retrieved from.

- The People's Project The People's project: Home. 2018. https://www.thepeoplesproject.org.nz/ Retrieved from.

- The People's Project Housing first: What is the People's project? 2019. https://www.thepeoplesproject.org.nz/about/housing-first Retrieved from.

- Tribunal W. Memorandum of the chairperson concerning the Kaupapa inquiry programme. 2015. https://www.waitangitribunal.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Publications/WT-Kaupapa-Inquiry-Programme-Direction.pdf Retrieved from.

- Tsemberis S. Hazelden; Minnesota: 2010. Housing first: The pathways model to end homelessness for people with mental illness and addiction. [Google Scholar]

- Turner A. Beyond Housing First: Essential elements of a system-planning approach to ending homelessness. University of Calgary: The School of Public Policy SPP Research Papers. 2014;7(30) [Google Scholar]

- $100 million to tackle homelessness. 2018. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/100-million-tackle-homelessness Twyford, P., Minister for Housing and Urban Development. [Press release]. Retrieved from.

- Wood G., Batterham D., Cigdem M., Mallett S. The structural drivers of homelessness in Australia 2001-11. 2015. https://espace.curtin.edu.au/bitstream/handle/20.500.11937/53333/252698.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y Retrieved from.

- Work and Income New Zealand Work Capacity medical certificate - information for health practitioners. 2018. https://www.workandincome.govt.nz/providers/health-and-disability-practitioners/guides/work-capacity-med-cert-health-practitioners.html#null Retrieved from.

- Workman K., McIntosh T. Crime, imprisonment and poverty. In: Rashbrooke M., editor. Inequality: A New Zealand crisis. Bridget Williams Books; Wellington: 2013. pp. 120–133. [Google Scholar]

- Worton S.K., Hasford J., MacNaughton E., Nelson G., MacLeod T., Tsemberis S.…Richter T. Understanding systems change in early implementation of Housing First in Canadian communities: An examination of facilitators/barriers, training/technical assistance, and points of leverage. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2017;61(1–2) doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]