Abstract

Background

there is a significant gap in the understanding, assessment and management of people with dementia and concurrent hearing and vision impairments.

Objective

from the perspective of professionals in dementia, hearing and vision care, we aimed to: (1) explore the perceptions of gaps in assessment and service provision in ageing-related hearing, vision and cognitive impairment; (2) consider potential solutions regarding this overlap and (3) ascertain the attitudes, awareness and practice, with a view to implementing change.

Methods

our two-part investigation with hearing, vision, and dementia care professionals involved: (1) an in-depth, interdisciplinary, international Expert Reference Group (ERG; n = 17) and (2) a wide-scale knowledge, attitudes and practice survey (n = 653). The ERG involved consensus discussions around prototypic clinical vignettes drawn from a memory centre, an audiology clinic, and an optometry clinic, analysed using an applied content approach.

Results

the ERG revealed several gaps in assessment and service provision, including a lack of validated assessment tools for concurrent impairments, poor interdisciplinary communication and care pathways, and a lack of evidence-based interventions. Consensus centred on the need for flexible, individualised, patient-centred solutions, using an interdisciplinary approach. The survey data validated these findings, highlighting the need for clear guidelines for assessing and managing concurrent impairments.

Conclusions

this is the first international study exploring professionals’ views of the assessment and care of individuals with age-related hearing, vision and hearing impairment. The findings will inform the adaptation of assessments, the development of supportive interventions, and the new provision of services.

Keywords: dementia, hearing, vision, expert reference group, cognitive impairment, older people

Key points

Experts agree that more training is needed to detect and manage the coexistence of cognitive & sensory impairment.

There is a need for correctly validated adapted assessments to account for concurrent deficits in cognition, vision and hearing.

Cross-discipline training and guidelines are needed for clinicians to improve assessment and care pathways.

Introduction

Hearing and vision impairments are among the most common and disabling co-morbidities in dementia, yet there is limited awareness, understanding and knowledge about how best to detect and manage them when they coexist. In a previous study, we found over 70% of people with dementia attending a community memory clinic reported that they required specific support for hearing problems, and those with higher levels of hearing loss, vision impairment and depression rated their quality of life worse than those with less severe difficulties in these areas [1]. Moreover, the evidence supporting hearing and vision loss as risk factors for cognitive decline and even dementia is growing [2, 3]. Thus, the public health and personal implications are clear, and improving detection of vision or hearing loss for people with cognitive impairment and implementing interventions early are potentially important steps to improve functional ability and quality of life. In spite of this, there are currently few specific recommendations for assessing and managing older people with these co-existing conditions [4, 5].

The opportunities to identify cognitive impairment at vision or hearing assessments are ripe [6]. For example, the UK’s National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has identified a specific need (NG16) for early identification and easy access to interventions, and UK’s College of Optometrists highlighted the need to adapt assessments for people with both vision impairment and dementia [7]. Considering the high level of comorbidity of hearing, vision and cognitive impairment, professionals in the respective disciplines of dementia care (i.e. geriatric psychiatry, neurology, mental health nursing, etc.), audiology and optometry, are ideally placed to identify these overlapping impairments. Nevertheless, there is a limited awareness, understanding and expertise amongst the respective professionals regarding the overlap of these conditions and the approach to assessment and intervention [8, 9].

To address this, we undertook a two-part investigation, involving: (1) an initial, in-depth international (Europe and North America) Expert Reference Group (ERG), with academic and clinical professionals (n = 17), representing audiology, geriatric psychiatry, psychology, social gerontology, neurology, vision science, optometry and speech and language therapy; and (2) a subsequent, wide-scale anonymous survey of professionals in hearing (n = 142), vision (n = 167) and dementia (n = 344) care, in the UK. Specifically, we aimed to: (1) explore the gaps in understanding, assessment and service provision; (2) elicit potential solutions; (3) ascertain the awareness, attitudes, and knowledge of the assessment and support of individuals with such comorbidity and (4) determine current practice regarding the assessment of the different domains in addition to the index domain. The overall goal was to inform the adaptation of current clinical assessment tools in the domains of hearing, vision and cognition [4] as well as to guide the development of a complex intervention to support hearing and vision functioning in people with dementia [5, 10, 11]. Our findings will help to understand the needs of health service providers to address the needs of affected individuals and to establish effective joint working amongst professionals to support patient care.

This study is part of the EU funded SENSE-Cog Programme which aims to understand and manage the overlap of ageing-related hearing, vision and cognitive impairment.

Methods

Study design

Part 1: International expert reference group

Setting

The ERG took place over two days in Athens, in April 2016, with multiple sessions divided into different activities, all with the aim of informing different aspects of the wider SENSE-Cog programme [reported in 10]. Here, we report on specific activities related to the aims of this paper.

Participants

A total of 17 of 23 clinical and academic experts, identified through literature review and personal contacts, and selected for their clinical or research expertise in the area, attended the meeting and were: audiologists (n = 3); psychologists (n = 3); hearing scientist (n = 1); dementia clinicians (n = 4); optician (n = 1); vision scientist (n = 1); social gerontologist specialising in older adult vision health (n = 1) and post-doctoral fellows working across disciplines (n = 2). The experts represented programmes of sensory and cognitive impairment in the UK (England and Wales), France, Germany, Cyprus, Greece and Canada.

Facilitators

The male and female facilitators of the ERG were members of the wider SENSE-Cog consortium, chosen to reflect diverse professional approaches to the topic. They included an academic geriatric psychiatrist, working clinically in a memory assessment centre in the UK but trained in Canada and the USA; a clinical academic audiologist, working in Cyprus and trained in Greece and the USA; an academic hearing science specialist, working in the UK with training in the UK in speech and language therapy and the psychology of hearing impairment. The scribes capturing feedback from the participants were post-doctoral researchers in psychology. Each facilitator was familiar with the topic area.

Data collection

This was based on full and break-out group guided discussions of prototype clinical vignettes, one from each domain (see Appendix 1). Prior to the break-outs, to provide a common language for discussion among the experts, a full group 30-min didactic session of topic-related material was presented. The experts were then semi-randomly assigned into two balanced working groups for facilitator-led discussions of each of the three case vignettes. The membership of each group was semi-randomly reassigned for each case, balanced by profession, country of work and facilitator (see Appendix 1). Facilitators prompted discussion by encouraging the group to discuss the case using four anchor questions regarding assessment and management methods employed in different settings:

‘What are the steps in your standard assessment of [domain specific] impairment?’

‘What problems might you encounter if the person has concurrent hearing/vision/cognitive problems?’

‘How might your standard assessment be adapted in the case of concurrent problems?’

‘What home-based interventions might improve the lives of people living with hearing, vision and cognitive difficulties?’

The scribe and facilitator captured the output using field notes and audio recording, kept the participants on track with the guided questions, and attempted to probe any examples of tacit knowledge that may have underlain suggested approaches. Following the break-out groups, the ERG participants re-convened for a shared plenary discussion of each of the three cases, led by the facilitators. This enabled group differences to be highlighted and discussed, and further summary points, captured by the scribes, to be made.

Part 2: Professionals’ anonymised survey

Respondent sample

From July 2017 to February 2018, we conducted a national UK survey involving 703 clinicians. Completed datasets were received from 653 clinicians from the following fields: dementia care (344) (including geriatric psychiatrists, psychologists, community psychiatric nurse and other allied health professionals); audiology (142), and optometry (167). Respondents were identified through our own clinical contacts in dementia care, audiology and optometry; and the memberships of the following professional bodies or networks: the UK’s Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Old Age Psychiatry faculty; the College of Optometrists; the British Society of Audiology; the British Academy of Audiology and Greater Manchester’s Eye Health Network. All respondents had to be actively working in a clinical or academic setting related to one of the three domains of vision, hearing or cognitive health. Our method did not allow for random sampling of respondents, nor were we able to ascertain the denominator of recipients of the survey for a response-rate calculation.

Data collection

Emails and paper-based surveys were sent in two waves. Both waves included a cover letter. We did not gather data from non-responders. Completion of the survey was considered implied consent and following completion of the survey, participants received a certificate recognising their contribution to supporting dementia research. There were neither other incentives, nor any requirement to complete the survey. The study was approved by our local ethical review board.

Instrument development

To ensure face validity, the survey instrument, based on the output of the ERG, was further co-produced with the input of a group of service users with experience of vision or hearing loss and dementia, and who were trained in the basics of clinical research methods through the SENSE-Cog research programme’s ‘patient and public intervention’ work stream [12]. Respondents were directed to answer each statement on a four point scale according to their agreement, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The draft versions were piloted by six professionals (two from each domain) and adjusted according to feedback. To optimise the response rate, our a priori goal, was not to exceed a 3-min average response time for survey completion. There were three versions of the survey minimally adapted to take account of the specifics of each group of professionals.

Analysis

Part 1: International expert reference group

Data were qualitatively analysed to answer the research question: ‘What are the gaps in understanding and service provision for people with dementia and hearing and/or vision impairment, and what possible solutions might there be?’ Content analysis using a combined model of deductive and inductive search strategies [13] was applied to the audio-recorded material and field notes from the scribes. These allowed for verification and confirmation when inconsistencies arose. All data were integrated to the Qualitative Analysis Software MAXQDA. A predefined short code list was created as per the objectives of the ERG. Codes consisted of: (1) ‘perceived gaps’, to capture shortcomings related to knowledge and/or availability of service provision for people with dementia and hearing and/or vision problems; and (2) ‘proffered solutions’, which related to any potential solution or strategy to address any of the perceived gaps identified in (1). Using these predefined codes, a first round of data coding was performed, which enabled sub-codes to emerge under the above given codes.

Part 2: Professionals’ anonymised survey

We analysed the complete data from the sample of 653 respondents. Any missing data in terms of individual item response was accounted for by pairwise deletion. The focus of our analysis was descriptive and pertained to the awareness, attitudes, knowledge and practice of the professional groups representing the three different domains.

Results

Part 1: International expert reference group

It was evident from the discussions that each expert made remarks from the viewpoint of their domain-specific expertise and level of experience in the area. Thus, among the different case vignettes, the level of contribution per expert varied. Analysis of the transcripts revealed that the process of discussing a prototypical case followed a pattern. Firstly, in all groups, the respective expert for the field (e.g. audiologist for the hearing case) started the discussion by presenting an expert perspective, informing the other experts, and revealing complexities for the other group participants. The subsequent discussion widened the perspective to encompass the expertise of the disciplines present. Finally, the mutual recognition of the complexity of the respective disciplines of those taking part in each group was also evident. This recognition was reflected by the frequent need for explanation of domain-specific information related to particular points of discussion for each case (see Appendix 2 for quotations).

The results presented here are confined to a summative overview of the gaps and solutions identified by experts, within the two codes. Specific quotations from experts supporting the codes are shown in Appendices 1 and 2.

Code 1: Perceived gaps in the assessment and intervention of individuals with overlapping impairment:

Across all the break-out groups, the consensus was that the lack of adapted assessments to account for concurrent deficits was the single most important gap. It was agreed that the complexity of the problem demanded ‘multiple’, ‘flexible’ and ‘needs-based’ solutions’, to detecting and correcting impairments and that simply correcting a single impairment, such as supplying a hearing aid, would not be sufficient. Furthermore, any proposed adapted assessment tool should go beyond the mere description of impairment and should consider the impact on an individual’s functional ability. The discussion highlighted the loss of validity of standard assessment tools when administered to people with dual or triple impairment. The most obvious problem was that of cognitive tests which rely heavily on hearing and vision for completion. It was agreed that adaptations to existing tools in all domains should occur with input from the other domain disciplines. The widely used Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) was considered inappropriate for individuals with hearing and/or vision impairment. Another gap identified was the relative lack of interdisciplinary contact among professionals of the respective domains. Finally, all agreed that comorbidity significantly increased the impact of the impairments on quality of life and that any identified gaps should be perceived using a patient-centred, as well as a couples-’ and caregiver-centred perspective, particularly if caregivers had their own health issues.

Code 2: Proffered solutions regarding the gaps in assessment and care:

This step focused on finding solutions for the gaps in understanding and service provision for people with dementia and hearing and/or vision impairment that were identified. Here, three patterns emerged: (1) consensus on some solutions; (2) recognition of gaps with no obvious solutions and (3) where consensus on solutions could not be found. When the discussion driven by a specific discipline reached the limits of possible solutions, the group looked to the other disciplines for alternatives, occasionally reaching beyond the represented disciplines and into allied domains such as occupational therapy or psychotherapy.

The first theme to emerge from the group was that any solutions had to be seen from the perspective of ‘interdisciplinarity’. Namely, all three disciplines should work together to adapt assessment tools, develop interventions, and build care pathways. It was agreed that cross-discipline training is critical, including as a means of quality control for when assessment tools are used within another domain (i.e. a hearing screen used in a memory clinic). This theme echoed the notion of ‘person-centred care’, which put the patient and their needs, rather than the discipline, at the centre of the frame of reference. Specific examples of improved assessment practices included hearing and vision specialists undertaking brief, adapted cognitive screens as part of their sensory-based functional assessments and memory specialists doing brief hearing and vision assessments. However, there were diverging opinions concerning identification of hearing and vision impairment by behavioural observation only, as well as diverging opinions regarding the utility of extensive diagnostic hearing and vision assessment. One participant stated that an in-depth audiological assessment in older adults with a neurocognitive disorder and moderate-to-severe hearing loss may cause additional physical and psychological burden.

As for care pathways, the group expressed the need for caution regarding the practice of ‘sign-posting’ among specialities or services, as this may lead to confusion and loss to follow-up, particularly if sign-posted to a service not skilled in understanding the co-morbidities involved. A solution suggested was the need for a common ‘sensory-cognitive’ team approach, with professionals from all three domains working seamlessly together and sharing a common knowledge base. This could involve a trained ‘sensory-cognitive’ outreach worker, who links with professionals in all three domains. Finally, the point was made that all healthcare workers in the broader field of older adult care should have heightened awareness of the added risks and burdens resulting from the overlapping impairments.

The next theme within this ‘solution’ Code was ‘adapting assessments’. The group discussed the different neuropsychological screening tools (e.g. Addenbrookes Cognitive Examination (ACE), Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, MMSE, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA), etc.) but did not reach a consensus about which test(s) may be most appropriate for identification of cognitive impairments among those with hearing and vision impairments. It was agreed that existing tools should be adapted to account for hearing, vision and cognitive comorbidity, rather than investing time in developing entirely new solutions. While such adaptation and re-validation work is ongoing, specific suggestions for immediate change included: (1) incorporating brief visual and/or hearing related assessments in memory clinics; (2) adding screening or ‘probe’ questions regarding cognitive function to hearing and/or vision assessments in audiology or optometry clinics; (3) focussing more on functional ability in all three clinical settings of all three domains; (4) ensuring that patients bring and wear best corrected hearing aids and glasses during cognitive assessments in memory clinics; (5) prioritising collateral information on functional ability in all three domains (from family, carers) and (6) taking information from peers and family and integrating ‘probe questions’ related to vision and hearing in memory assessments.

The final theme to emerge centred on ‘Intervention-related solutions’, which included ‘person-centred’ and ‘environment-centred’ approaches. It became apparent that management of one sensory domain (i.e. treating a hearing loss by providing a hearing aid) may not address all of the individuals’ sensory needs. Therefore, here, as with the approach to assessments, the notion of ‘individualization’ and ‘flexibility’ of approach was considered paramount. The person-centred approach should address the patient’s home setting and the social networks to optimise the outcomes of any intervention. Furthermore, it was suggested that a rehabilitation approach is important, so as to maximise an individual’s potential. A specific example was that a professional should ensure that an individual has the visual, cognitive and perceptual ability to handle and use a small hearing aid correctly. As for ‘environment-centred’ approaches, the group had several suggestions, including the need for home-based ‘environmental’ support, which could involve installing auditory and visual adaptations to the television and high lux lights for close work, managing light versus glare, designating a ‘hearing friendly’ room (i.e. with good acoustics due to soft furnishings. etc.), installing ‘visible’ doorbells, and other pragmatic solutions. It was noted that the earlier such assistive devices as hearing aids were offered, the better (i.e. in the mild cognitive impairment or early dementia stage) since people in the more advanced stages of dementia might have more difficulties accepting or using a hearing aid.

Part 2: Professionals’ anonymised survey

The majority of respondents were dementia care professionals (n = 344, 52.7%; physicians, nurses, allied health professionals), followed by vision professionals (n = 167, 25.6%) and hearing professionals (n = 97, 21.7%). The respondent sample was representative, consisting of 453 females (69.4%) and 200 males (30.6%) at varying career stages; 152 people working for <5 years (23.3%), 236 people working for between 5 and 15 years (36.3%) and 263 people working for >15 years (40.4%).

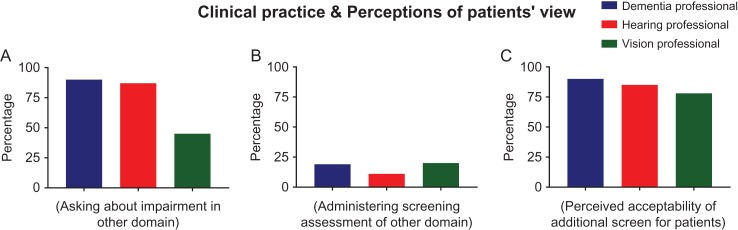

Details of the survey responses are outlined in Figures 1–3.

Figure 1.

Survey responses from health professionals who endorsed questions about their awareness regarding hearing, vision and cognitive impairments. Bar graphs show the percentage of each group in agreement to the statements about ‘Awareness’ of (A) the overlap between dementia, hearing and vision impairment, (B) brief assessments for use in conjunction with primary assessment and (C) referral/care pathways for patients who have positive screens.

Figure 3.

Survey responses from health professionals who endorsed questions about their awareness regarding hearing, vision and cognitive impairments. Bar graphs show the percentage of each group in agreement to the statements about ‘Professionals’ clinical practice and perceptions of patients view’, regarding (A) asking about impairment in cognition/hearing/vision (B) administering a brief cognitive/hearing/vision assessment in addition to the main assessment and (C) perceived acceptability of a brief screening assessment in addition to the main assessment.

In general, professionals across all domains reported awareness of the overlaps between cognitive, hearing and visual impairment (Figure 1A). When answering how often they asked about impairment in the alternative domains, a high proportion of dementia and hearing professionals reported commonly asking (90% and 87%, respectively), but the proportion of vision professionals asking about cognitive impairment was notably lower at only 45% (Figure 3A).

In spite of this, Figure 1B shows the proportion in all three groups reporting awareness of brief screening assessments for use in conjunction with their primary assessment was relatively low (mean = 42.13%, SD = 6.66). Few professionals felt they had sufficient training to administer the alternative screen (Figure 2B), adequate knowledge of how to use the results of the additional assessment (Figure 2A), and enough awareness of referral pathways for a positive screen (Figure 1C).

Figure 2.

Survey responses from health professionals who endorsed questions about their knowledge, skills and attitudes regarding hearing, vision and cognitive impairments. Bar graphs show the percentage of each group in agreement to the statements about ‘Knowledge, skills and attitudes’ around (A) how to use the results of the additional brief assessment in care management, (B) training/expertise in administering a brief screening assessment and (C) perceived usefulness of guidelines on brief assessments to use in addition to the usual assessment.

Very few non-dementia clinicians (16%) reported administering cognitive assessments in hearing and vision clinics (Figure 3B), and the ones that did reported the following: self-reported cognitive impairment (n = 5); MMSE (n = 6); MOCA (n = 1); Abbreviated Mental Test (n = 1); ACE-Revised (n = 1); Mini-Cog (n = 4) and ‘other’ screening assessments (n = 7).

Approximately half of the physicians in the ‘dementia professionals’ group reported administering some type of hearing or vision screening assessment, albeit a self-report measure (46% of the hearing screen and 19% of the vision screens) whereas the proportion of non-physiciandementia professionals was considerably lower at 8%. Other types of auditory screening assessment administered by dementia professionals included: the Hear Check (n = 4), which is a simple but validated hand-held objective hearing test; parts of the physical exam (n = 11), including the whisper test (n = 3), bedside tuning fork (n = 3) or not reported (n = 5) and Hearing Handicap Inventory for the older people (n = 3), which is a short questionnaire identifying possible difficulties experienced due to hearing loss. For vision screening, the following assessments were used: visual acuity charts (n = 39), neurological exam (n = 7), which included the visual fields test (n = 4); and ‘other’ screen assessments or questionnaires which were not defined (n = 9). Finally, over 90% within each group agreed that guidelines would be useful (Figure 2C) and that patients would find a brief screening assessment acceptable as part of their primary assessment (Figure 3C).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the perspectives of European and North American professionals representing all three domains of hearing, vision and dementia care, regarding the assessment and care needs of individuals with dual- and triple-impairments. The qualitative analysis from the ERG revealed three main gaps for people with concurrent hearing, vision and cognitive impairment: (1) a lack of standardised, sensitive clinical assessment tools and evidence-based interventions; (2) poor interdisciplinary communication and care pathways and (3) a lack of evidence-based interventions to address these needs. Agreed solutions centred on the need for flexible, individualised, patient- and caregiver-centred approaches, based on an interdisciplinary approach. Results from the subsequent survey revealed data to support these findings, in that in spite of being aware of the overlaps among the co-morbidities, screening is not routinely undertaken, professionals do not feel confident in interpreting the screening assessments, and understanding of how positive screens may impact on subsequent care is lacking. These findings highlight the urgent need to implement changes in current practice and that more training and guidelines regarding assessment and care would be welcomed.

The identified need to develop brief, sensitive assessment instruments for sensory function and cognition is consistent with the literature [9, 14]. In particular, cognitive assessments should be appropriately adapted and fully validated in people with dual and triple-impairments, and hearing and vision assessment procedures and protocols need to be modified to take into account cognitive loss. Such tools, procedures and protocols should be made available across disciplines to guide referral for further specialised assessment, as previously recommended [7]. Furthermore, consistent with the World Health Organisation International classification of Functioning, Disability and Health framework [15] contextual assessments using standardised brief questionnaires such as the AD8 could enhance the sensitivity of standard screening measures [16]. Within the wider SENSE-Cog programme, adaptation and validation of adapted, brief cognitive tools in multiple languages is currently ongoing. In adapting an existing tool, it is essential to include questions with the best discriminative power. Furthermore, within SENSE-Cog, an online screening tool for all three domains of hearing, vision and cognitive impairment for self-administration by individuals at home, as well as to guide sign-posting by clinicians, has been developed and is being validated.

The need for evidence-based interventions for people with sensory-cognitive impairments must simultaneously address all affected domains since standard interventions will likely not result in desired outcomes [17]. The findings from the current study, together with an earlier study investigating management of comorbid vision impairment and dementia [9] have informed the development of a new home-based, individualised hearing and vision intervention to improve quality of life of people with dementia. The intervention has now been field tested and full scale efficacy testing in a randomised clinical trial across five European started in Spring 2018 [10, 11, 18]. The intervention, delivered by a specially trained ‘sensory support therapist’ (SST), will encompass interdisciplinary aspects including home-based patient, environment, family-centred approaches.

Finally, with regards to the methodology of our study, the theoretical basis for the Expert Reference Group was derived from the field of ‘expert knowledge elicitation’, which is well developed in other fields such as computer engineering and software design. Techniques to probe the domain-specific knowledge and experience of experts include methods such as interviews, workshops, expert conversations, scenarios and the use of prototypes [19–22]. We chose a workshop-based collaborative, dialogue-based method, based around prototype case vignettes, which has been shown to be very effective [20], followed by a wide-ranging survey to validate and extend the findings.

In conclusion, this study explored key aspects of the assessment and care of individuals with age-related hearing, vision and hearing impairment, from the perspective of professionals representing all three domains. This has provided valuable insights which will inform the adaptation of assessments, the development of supportive interventions, and the new provision of services.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data mentioned in the text are available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to the Expert Reference Group members: Kathy Pichora-Fuller, Anna Pavlina Charalambous, Chryssoula Thodi, Piers Dawes, Iracema Leroi, Lucas Wolski, Valeria Orgeta, Rachel Domone, Sarah Bent, Thomas Bisitz, Antonis Politis, Sotiris Plainis and Argyro Voulgari. Thanks to those who helped the survey: Greater Manchester NIHR Clinical research network, Gemma Stringer, Kim Wrigley, Kitti Kotasz, Michael Bowden and Gregor Russell.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest: None.

Declaration of Sources of Funding: This work was supported by the SENSE‐Cog project, which has received funding from the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Grant Agreement 668648. PD and JL are supported by the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre and received funding from Deafness Support Network.

Ethical approval: Ethics Committee Approval from North West-Greater Manchester Research Ethics Committee.

References

- 1. Leroi I, Pye P, Simkin Z, Hann M, Regan J, Dawes P SENSE-Cog: Exploring the needs of individuals living with dementia and sensory impairment. Abstract. 5th annual BIT conference on Geriatrics and Gerontology, Fukuoka, 2017.

- 2. Maharani A, Dawes P, Nazroo J, Tampubolon G, Pendleton N, Sense-Cog WP1 group . Visual and hearing impairments are associated with cognitive decline in older people. Age Ageing 2018; 66: 1130–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 2017; 390: 2673–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pye A, Charalambous P, Leroi I, Thodi C, Dawes P. Screening tools for the identification of dementia for adults with age-related acquired hearing or vision impairment: a scoping review. Int Psychogeriatr 2017; 29: 1771–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dawes P, Wolski L, Himmelsbach I, Regan J, Leroi I. Interventions for hearing and vision impairment to improve outcomes for people with dementia: a scoping review. Int Psychogeriatr 2018; 24: 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thodi C, Charalambous AP, Dawes P, Wolski L, Leroi I, Himmelsbach I Hearing and Vision Impairment in Dementia: Gaps and Solutions, a view from the professionals. Abstract. 16th Annual Meeting of the International Society of Geriatric Psychopharmacology, Athens, 2016.

- 7. Hancock B, Shah R, Edgar D, Bowen M. A proposal for a UK dementia care pathway. Optomet Pract 2015; 16: 71–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Charalambous AP, Dawes P, Wolski L et al. Cognitive assessment of adults with hearing and/or vision impairment. Abstract. 16th Annual Meeting of the International Society of Geriatric Psychopharmacology, Athens, 2016.

- 9. Lawrence V, Murray J. Balancing independence and safety: the challenge of supporting older people with dementia and sight loss. Age Ageing 2010; 39: 476–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leroi I, Pye A, Armitage CJ et al. Research protocol for a complex intervention to support hearing and vision function to improve the lives of people with dementia. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2017; 3: 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Regan J, Dawes P, Pye A et al. Improving hearing and vision in dementia: protocol for a field trial of a new intervention. BMJ Open 2017; 7: e018744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miah J, Bamforth H, Charalambous A et al. Overcoming the challenges of involving older people with dementia, hearing and vision problems in research- sharing learning and future progress. Res Involv Engagem 2017; 3 (Suppl 1): 015. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mayring P. Qualitative Content Analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/ Forum: Social Research [online] 2000; 1: .

- 14. Phillips NA. The implications of cognitive ageing for listening and the framework for understanding effortful listening. Ear Hear 2016; 37 (Suppl 1):44S–57S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organisation International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health: World Health Organisation [Online] Geneva 2001; available: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/ [Accessed 26.04.18].

- 16. Constantinidou F, Christodoulou M, Prokopiou J. The effects of age and education on executive functioning and oral naming performance in Greek Cypriot Adults: the neurocognitive study for the aging. Folia Phoniatr Logop 2012; 64: 187–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Taljaard DS, Olaithe M, Brennan-Jones CG, Eikelboom RH, Bucks RS. The relationship between hearing impairment and cognitive function: a meta-analysis in adults. Clin Otolaryngol 2016; 41: 718–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Regan J, Collin F, Frison E et al. A randomised controlled trial of hearing and vision support in dementia: Protocol for SENSE-Cog Trial. (under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19. Burge J. ‘Knowledge Elicitation Tool Classification’. Artificial Intelligence Research group, Worcester Polytechnic Institute 2001; available: http://web.cs.wpi.edu/~jburge/thesis/kematrix.html [Accessed 20.04.18]

- 20. Coughlan J, Macredie RD. Effective communication in requirements elicitation: a comparison of methodologies. Requir Eng 2002; 7: 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hadorn D, Kvizhinadze G, Collinson L, Blakely T. Use of expert knowledge elicitation to estimate parameters in health economic decision models. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2014; 30: 461–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maiden NAM, Rugg G. ACRE: a framework for acquisition of requirements. Softw Eng J 1996; 11: 183–92. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.