Abstract

Background

The long-term effectiveness of group continence promotion delivered via community organisations on female urinary incontinence, falls and healthy life expectancy remains unknown.

Methods

A pragmatic cluster randomised trial was conducted among 909 women aged 65–98 years with urinary incontinence, recruited from 377 community organisations in the UK, Canada and France. A total of 184 organisations were randomised to an in-person 60-min incontinence self-management workshop (461 participants), and 193 to a control healthy ageing workshop (448 participants). The primary outcome was self-reported incontinence improvement at 1-year. Falls and gains in health utility were secondary outcomes.

Results

A total 751 women, mean age 78.0, age range 65–98 completed the trial (83%). At 1-year, 15% of the intervention group versus 6.9% of controls reported significant improvements in urinary symptoms, (difference 8.1%, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 4.0–12.1%, intracluster correlation 0.04, number-needed-to-treat 13) and 35% versus 19% reported any improvement (risk difference 16.0%, 95% CI 10.4–21.5, number-needed-to-treat 6). The proportion of fallers decreased from 42% to 36% in the intervention group (−8.0%, 95% CI −14.8 – −1.0) and from 44% to 34% in the control group (−10.3%, 95% CI −17.4 – −3.6), no difference between groups. Both intervention and control groups experienced a gain in health utility (0.022 points (95% CI 0.005–0.04) versus 0.035 (95% CI 0.017–0.052), respectively), with no significant difference between groups.

Conclusion

Community-based group continence promotion achieves long-term benefits on older women’s urinary symptoms, without improvement in falls or healthy life expectancy compared with participation in a healthy ageing workshop.

Keywords: urinary incontinence, older women, falls, health utility, cluster randomised trial, older people

Key points

Group-based continence promotion improves older women’s urinary incontinence.

There was no effect on falls or healthy life expectancy compared with healthy ageing education.

Community organisations can play a pivotal role in promoting health education to older women.

Frail older women benefit from community-based interventions.

Pragmatic community-based clinical trials are feasible and acceptable to older women.

Introduction

Urinary incontinence and falls rank among the most frequent geriatric syndromes. Prevalence estimates for both exceed 30% among community-dwelling older women, depending on the population studied [1, 2]. Incontinence is associated with falls, exacting a significant toll on quality of life (QOL) [1, 2]. Brief, low-cost interventions with proven long-term effectiveness on urinary symptom improvement and a reduction in fall rates have yet to be tested, scaled up and implemented worldwide.

The European Research Area in Ageing was launched in 2004 to fund innovative transnational research that improves healthy active life expectancy among older adults, through the roll out of socially meaningful interventions [3]. The Continence Across Continents to Upend Stigma and Dependency (CACTUS-D) cluster-randomised trial was funded through this initiative. CACTUS-D sought to compare the long-term effectiveness of a community-based group continence promotion workshop against a control intervention on improvements in urinary incontinence symptoms among older women at 1-year follow-up. Secondary outcomes were fall reduction and improved health-related QOL. Outcomes were evaluated at the level of the individual.

Methods

The trial design was a pragmatic, open-label, two-arm, international, multi-site cluster-randomised controlled trial [4]. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from all four sites by 26 March 2013. Written informed consent to participate in the trial and publish the data was obtained from each individual. ClinicalTrials.govIdentifier:NCT01858493.

Community organisation and participant enrolment

Any community organisation (the cluster unit) from France, the UK and Canada (Quebec and Alberta provinces) was eligible to participate if their membership included older women. Community organisations were contacted by phone or mail to assess cluster eligibility and interest. Cluster randomisation was used to prevent contamination between participants from each organisation.

Eligible participants from each cluster were female members from consenting organisations who were 65 years or older, spoke English or French, self-reported at least two incontinence episodes weekly, were not taking medications to treat incontinence and had not sought professional advice for incontinence symptoms within the past year. Participants did not undergo physical examination or objective clinical outcomes assessment at baseline or follow-up. We excluded participants with a major neurocognitive disorder, based on self-report. In France and in Western Canada, baseline data were collected and participants were screened and enroled prior to randomisation. In the UK and Quebec, women completed the baseline questionnaire prior to randomisation, but interested participants only signed the consent form and returned the baseline questionnaire after the workshop was completed. The latter approach was required by the Ethics Boards and organisations’ preferences in order to allow all members of the participating organisation to attend the workshops. In a second screening stage, a research assistant confirmed eligibility status and interest in enroling in the trial via telephone follow-up within 1 week of the workshop.

Randomisation and allocation concealment

Consenting organisations were randomised in a 1:1 ratio to a continence promotion or control intervention in permutated alternating block sizes of 2 or 4, stratified according to site. An independent statistician blindly allocated organisations using computer-generated stochastic digits. The trial was blinded at the level of cluster randomisation as the community organisations, the research assistants who performed the telephone follow-ups, and the statistician who analysed the outcomes were blinded to group allocation. However, the trial is considered open-label because the participants who received the interventions were aware of group allocation at the time of implementation.

Interventions

The experimental intervention was a continence promotion workshop, modelled on a successful pilot trial conducted in the UK [5]. The control intervention was a healthy ageing workshop that did not address treatment for incontinence. The rationale for the control workshop was to account for the social effect on QOL of bringing older women together to discuss health issues, and to diminish community organisations’ concerns about encouraging its members to attend a 1-h lecture-discussion that was deliberately designed not to help improve health. Both the experimental and control interventions started with an icebreaker on memory problems. The continence promotion intervention then evolved into a facilitated interactive discussion to address myths surrounding involuntary urine loss and possible causes. Descriptions of self-management techniques such as pelvic floor muscle exercises and lifestyle interventions were provided. A self-management brochure was distributed. In lieu of detailed continence promotion information, participants in the control healthy ageing workshop engaged in a facilitated discussion about the causes and solutions to hearing loss, medication side effects and insomnia. The workshops and self-management brochures are available at https://www.deprescribingnetwork.ca/cactus-trial.

Trained research assistants acted as facilitators and delivered each workshop in person in English or French, once, within a 60-min period to groups of participants at each community centre. The materials and script for each workshop were adapted to context for language, visual graphics and culture. Fidelity to the script and key messaging for each intervention were verified on a regular basis by having each facilitator record their presentation and send it to a facilitator at a different site who checked the content against an agreed upon fidelity checklist.

Outcomes

Outcomes were collected at 1 week and 3, 6, 9 and 12 months at the level of the individual. The primary outcome was sustained incontinence improvement at 1-year post-intervention, measured by the Patient’s Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I) questionnaire [6]. Secondary outcomes included the proportion of participants in each group who reported falls, queried with a fall diary and phone follow-up, and improvement in generic health-related QOL recorded with the Short Form-12v2 (SF-12v2) and the SF-6D [7]. We chose the SF-6D in response to the funders’ request to assess interventions based on their ability to improve healthy active life expectancy. The SF-6D represents preference-weighted utility scores ranging from 0 to 1, where 0 represents death and 1 represents perfect health, and can be converted to a generic measure of quality-adjusted life years.

A participant scoring their urinary symptoms at telephone follow-up as “very much better” or “much better” on the PGI-I was deemed to have a clinically important improvement, based on previous correlation with voiding diaries, clinician assessment and prior trials of continence promotion [5, 6, 8]. Any improvement was defined as a PGI-I score of “very much better”, “much better” or “a little better”.

In order to characterise participants enroled in the trial, we measured frailty at baseline using the 13-item Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES-13) [9]. A score of ≥ 3 on the VES-13 predicts a 4.2-fold increase in mortality or functional decline in a 2-year period. We also administered the Incontinence Quality of Life (I-QOL) questionnaire and the International Consultation on Incontinence-Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (ICIQ-FLUTS) questionnaire to measure the frequency, severity, bother and type of incontinence [10, 11]. The diagnostic value of simple questions through self-report has been shown to be similar to that of clinical examination for determining the presence and type of incontinence [12]. At 1-year, participants were asked if they regularly performed pelvic floor muscle exercises as a result of the workshop, and whether they sought care for their symptoms.

Statistical analysis and power

All analyses were conducted on an intent-to-treat basis. To assess improvements in incontinence, we estimated the unadjusted risk difference (prevalence of the outcome) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) via generalised estimating equations with an identity link and an exchangeable correlation structure to account for possible correlation between women in the same organisation. Falls were analysed using the proportion of participants in each group who had one or more falls. Post hoc analyses were stratified by frailty because there was a higher rate of frailty among participants in the control group. Partially missing SF-12 data at a given time were imputed using a missing-at-random Bayesian model, which has been reported and validated [13]. We used RStudio 1.0.153 and R 3.4.1, and Stan in R through the RStan 2.16.2 package.

Sample size calculations for the primary outcome (an improvement in incontinence) were based on assumptions of a 26% improvement rate in the intervention group, and a 6% improvement in the control group (difference of 20% between the two trial arms) [14]. To detect this 20% difference with 80% power, at a 0.05 significant level, with an intracluster correlation of 0.05, unequal cluster size, and an expected attrition rate of up to 20%, we calculated 200 participants per site. With four sites, we estimated a sample size of 800 for the entire study, in order to have sufficient sample size to conduct sub-group analyses by site. [14]. An inflation factor of 1.65 was applied to account for potential correlation between individuals in the same cluster (i.e. anticipated intraclass correlation of 0.05), and the unequal cluster sizes (ranging from 8–16 individuals per cluster) [15].

Results

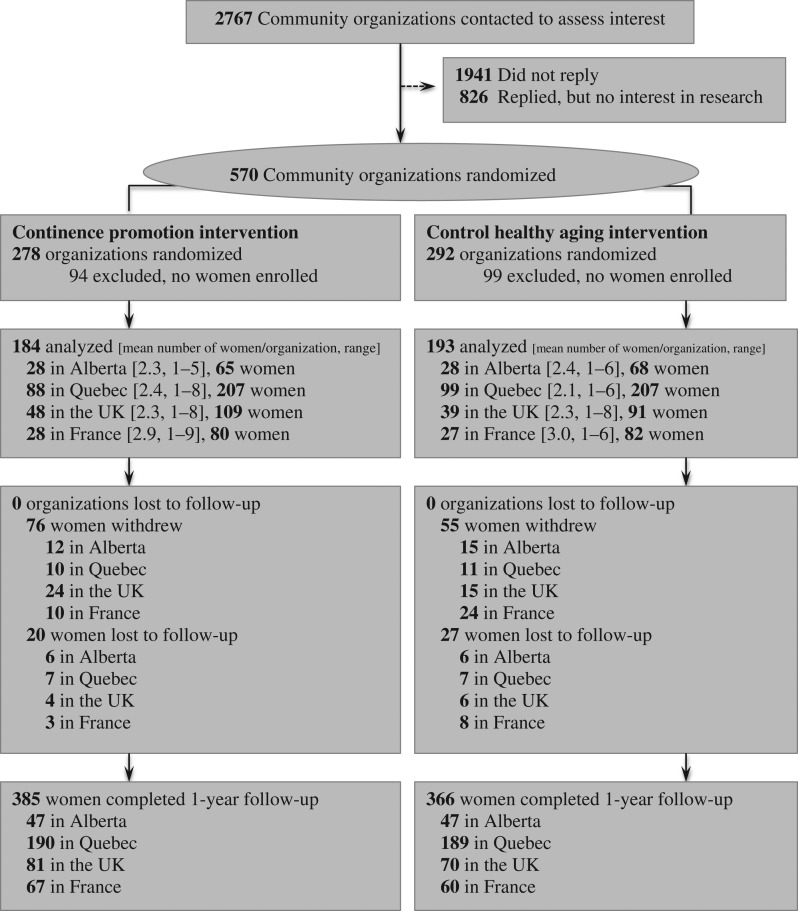

Over the course of 3 years, from June 2013 until June 2016, 2767 community organisations were invited to participate and 570 (21%) consented to enrol in the trial. Community organisations included religious and seniors’ organisations, women’s centres, residences, and seniors’ clubs. A total of 9432 women attended the workshops, of which 909 met eligibility and consented to enrol in CACTUS-D. The continence promotion intervention included 461 women (184 clusters) versus 448 (193 clusters) in the control arm (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Participant flow through the trial.

The baseline characteristics of participants are listed in Table 1. The age range was 65–98. More than a quarter of participants experienced incontinence several times per day. About 53% of participants met frailty criteria at baseline. There were no significant differences by site. A total of 751 participants completed the study, with 47 lost-to-follow-up and 111 withdrawals.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at baseline

| Intervention n = 461 | Control n = 448 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean ± SD, range) | 77.4 ± 7.8, 65–98 | 78.6 ± 7.9, 65–98 |

| Living alone (%) | 61.1 | 60.9 |

| Self-reported fair or poor health (%) | 23.6 | 27.9 |

| SF-12 derived utility (mean ± SD)a | 0.729 ± 0.127 | 0.707 ± 0.132 |

| Frail (n, % of total)b | 225 (48.8%) | 256 (57.1%) |

| Comorbidities (%)c | ||

| Depression | 23.6 | 24.5 |

| Heart disease | 27.5 | 31.9 |

| Arthritis | 44.7 | 48.7 |

| Diabetes | 16.9 | 19.4 |

| Hypertension | 55.3 | 56.9 |

| Experienced a fall in previous year (%) | 41.8 | 43.8 |

| Study site (%) | ||

| Alberta, Canada | 14.1 | 15.1 |

| France | 17.4 | 18.3 |

| UK | 23.6 | 20.3 |

| Quebec, Canada | 44.9 | 46.2 |

| Type of incontinence (%) | ||

| Urge | 27.3 | 21.0 |

| Stress | 12.4 | 11.6 |

| Mixed | 46.8 | 51.1 |

| Other | 23.5 | 16.3 |

| Nocturia (>2 micturitions/night)d | 26.5 | 29.2 |

| Severity of incontinence (%) | ||

| 2–3 times per week | 41.0 | 47.7 |

| Once per day | 29.3 | 23.7 |

| Several times per day | 29.7 | 28.6 |

| I-QOL score (mean ± SD) | 78.4 ± 18.4 | 78.3 ± 19.2 |

| ICIQ-FLUTS score (mean ± SD, range) | 15.1 ± 5.4, 4–32 | 15.3 ± 5.6, 3–37 |

I-QOL, Incontinence Quality of Life scale. Overall scores 0–100, higher scores indicate higher quality of life.

ICIQ-FLUTS, International Consultation on Incontinence-Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptom scale. Overall scores 0–48, higher scores indicate worse symptoms.

aValues from imputed data.

bBased on VES-13 with score ≥ 3 establishing frailty.

cProportions do not equal 100% because more than one comorbidity may be present.

dNocturia was reported concurrently with the type of incontinence, so does not add up to 100%.

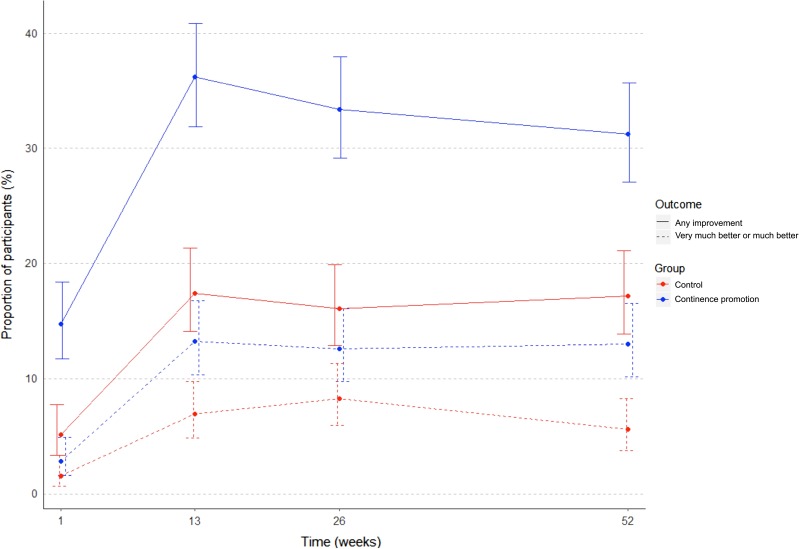

Urinary incontinence

Improvement in UI symptoms at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months post-intervention for the continence promotion and control group is illustrated in Figure 2. Positive results were obtained at 3 months for both clinically important and any improvement in UI, and these were sustained at 1-year follow-up. At 1-year follow-up, 15% of women in the continence promotion group reported clinically important urinary symptom improvement compared with 6.9% in the control group (difference 8.1%, 95% CI 4.0–12.1%, intracluster correlation 0.04, number-needed-to-treat = 13) (Table 2). Thirty-five percent versus 19.4% reported any improvement (risk difference 16.0%, 95% CI 10.4–21.5, intracluster correlation 0.02, number-needed-to-treat = 6). Incontinence-related QOL also changed favourably in the continence promotion compared with the control arm. At study endpoint, the proportion of participants practicing pelvic floor muscle exercises increased by 32% (95% CI 25–40%) in the continence promotion group. Eighteen percent of the women in each group reported seeking professional help for incontinence after participating in the workshop.

Figure 2.

Improvement in urinary incontinence over time.

Table 2.

Primary and secondary outcomes 1-year post-intervention

| Continence promotion arm | Control healthy ageing arm | Difference between participants in trial arms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Non-frail | Frail | All | Non-frail | Frail | ||

| n = 461 | n = 236 | n = 225 | n = 448 | n = 192 | n = 256 | n = 909 | |

| Primary Outcome: Urinary incontinence | |||||||

| Significant improvement % [95% CI] | 15.0 [11.8–18.6] | 16.5 [11.9–21.9] | 13.8 [9.6–19.0] | 6.9 [4.8–9.7] | 9.0 [5.3–14.0] | 5.5 [3.0–9.0] | 8.1 [4.0–12.1] |

| Any improvement % [95% CI] | 35.1 [30.8–39.7] | 38.5 [32.2–45.1] | 32.0 [26.0–38.5] | 19.4 [15.9–23.4] | 23.8 [17.9–30.5] | 16.4 [12.1–21.5] | 16.0 [10.4–21.5] |

| Gain in I-QOL score [95% CI] | 6.7 [5.6–7.8] | 8.0 [6.5–9.4] | 5.6 [3.9–7.3] | 5.4 [4.3–6.6] | 5.6 [4.1–7.0] | 5.5 [3.8–7.2] | 1.3 [1.2–1.4] |

| Decrease in ICIQ-FLUTS score [95% CI] | −2.8 [−11.6–5.9] | −3.0 [−10.5–4.5] | −2.7 [−12.6–7.3] | −2.3 [−11.1–6.4] | −2.9 [−11.5–5.8] | −2.0 [−10.7–6.8] | −0.5 [−1.1–0.1] |

| Secondary Outcome: Change in proportion of fallers, compared with previous year, % [95% CI] | −8.0 [−14.8 – −1.0] | −3.7 [−12.6–4.7] | −10.7 [−21.6 – −1.6] | −10.3 [−17.4 – −3.6] | −2.2 [−12.1–8.0] | −16.1 [−25.0 – −6.3] | −2.5 [−13.0–8.1] |

| Secondary Outcome: Gain in quality-adjusted life years, utility score [95% CI] | 0.022 [0.005–0.04] | 0.037 [0.016–0.058] | 0.007 [−0.002–0.032] | 0.035 [0.017–0.052] | 0.023 [−0.001–0.047] | 0.044 [0.022–0.066] | −0.013 [−0.029–0.005] |

I-QOL, Incontinence Quality of Life scale. Overall scores 0–100, higher scores indicate higher quality of life.

ICIQ-FLUTS, International Consultation on Incontinence-Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptom scale. Overall scores 0–48, higher scores indicate worse symptoms.

CI, confidence interval.

Falls

The proportion of fallers decreased in the intervention group from 42% at baseline to 36% at follow-up (difference −8.0%, 95% CI −14.8 – −1.0), and from 44% to 34% in the control group (difference −10.3%, 95% CI −17.4 – −3.6), with no significant difference between groups (Table 2).

Health-related quality of life

Women in both the intervention and control groups reported significant improvement in generic health-related QOL at 1-year, with no difference between groups (Table 2). Outcomes did not differ by site for any of the trial endpoints, nor by the timing of enrolment either pre- or post-randomisation.

Post hoc frailty sub-group analyses

Differential effects were observed among frail and non-frail women in both trial arms (Table 2). Non-frail women in the continence promotion group achieved the greatest improvement in incontinence, with 38.5% (95% CI 32.2–45.1%) reporting any improvement at 1-year follow-up, and an associated utility gain of 0.037 points (95% CI 0.016–0.058). Frail women in the control group experienced the greatest reduction in falls, from 46.9% at baseline to 30.5% at follow-up (mean difference 16.1%, 95% CI 6.3–25.0), and the greatest gain in health utility (0.044 points, 95% CI 0.022–0.066) (Table 2).

Discussion

This international randomised trial demonstrated a sustainable improvement in incontinence symptoms among untreated older women exposed to a group continence promotion workshop. Participants in both the continence promotion and healthy ageing control workshops reported an overall decrease in falls and improved QOL, with no clear comparative benefit attributable to continence promotion. As only 1.4% of clinical trials focus exclusively on health interventions for older adults [16], we believe the results from this study make an important contribution to the armamentarium of evidence-informed community interventions that can be scaled up to promote healthy ageing.

Our results align with another recent trial in the outpatient setting demonstrating the success and low cost of a one-time bladder health class for older women on urinary symptom improvement [17]. However, the CACTUS-D trial is the first to investigate whether a community-based group intervention to promote continence can lead to a reduction in falls, filling a gap in evidence linking continence management to fall prevention [18, 19]. Women in the continence promotion group achieved a significant reduction in falls, as did women exposed to the control healthy ageing workshop. The control workshop addressed insomnia, medication side effects and sensory deficits. Although we cannot be certain, we hypothesise that the reduction in falls observed among the control group participants may have been due to deprescribing medications such as sedative-hypnotics, or better management of insomnia and sensory deficits. As there was no comparison to a similar group of older women without any health education exposure, it is impossible to know whether continence promotion alone, education about healthy ageing alone, or neither of the two confers benefits on falls and healthy life expectancy.

Several methodological challenges and limitations warrant mention. Only 20% of community organisations internationally agreed to enrol in the CACTUS-D trial, mainly because of disinterest in participating in health research. Many organisations refused to screen their members for incontinence eligibility prior to enrolment, for reasons of confidentiality and to ensure equal access to the workshops regardless of health status. As women were permitted to enrol in the study after exposure to the intervention in two sites, this likely contributed to post-randomisation selection bias, and a higher likelihood of frail women being recruited to the control workshop [20]. Women who attended the community organisations self-selected to a degree because they enjoyed social interaction and could have been more likely to participate. Additionally, the people selected may not have identified continence as a problem to them personally: even if they had the condition, it may not have bothered them. This may have affected improvement status. The SF-12 questionnaire was used because it captured the impact of physical and emotional health on activities and social function [7, 14], and allowed calculation of utilities and quality-adjusted life years, which are widely accepted [21]. However, no standard value for a clinically meaningful gain in health utilities exists for older women. Based on longitudinal studies, a 0.04 improvement in health utility over 1 year appears to be significant, but future studies are needed to validate this threshold [22–24]. The Hawthorne effect or social desirability bias combined with recall bias about falls in the year prior to the study may explain the gains in falls and QOL reported by participants in both the continence promotion and healthy ageing groups.

In conclusion, sustainable 1-year improvements in incontinence were achieved through group continence promotion delivered via community organisations to untreated older women compared with exposure to a healthy ageing workshop. Benefits on falls and QOL were observed among women exposed to both the continence promotion and the control healthy ageing workshops, with no difference between groups. Partnering with community organisations appears to be an effective way of engaging older women in health promotion activities.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the assistance of Marie-Eve Lavoie and Stephanie Ragot for their expert help with database management. Nastaran Sepanj, Lucie Merlet, Florence Steffener, Saima Rajabali, Brenda Parks and Marie-Eve Lavoie aided with recruitment and program delivery. The above-mentioned individuals received financial compensation for their contribution to this work. We express gratitude to all the participants who took part in this trial.

Declaration of sources of funding: The study was funded by a joint collaboration between the European Research Area on Ageing2 (ERA-AGE2) programme, with contributions from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec, the Economic and Social Research Council of the UK, the Institut National de Prévention et Éducation pour la Santé de la France, and the Observatoire régional de la Santé, Poitou-Charentes Publique de Poitou-Charentes. The authors retained full independence from the study sponsors in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review and approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of Conflict of Interest: None.

References

- 1. News From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention US toll from incontinence. JAMA 2014; 312: 884–884. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gale CR, Cooper C, Aihie A. Prevalence and risk factors for falls in older men and women: the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age Ageing 2016; 45: 789–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Geyer G. Establishing the European Research Area in Ageing: a network of national research programmes. Exp Gerontol 2005; 40: 759–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tannenbaum C, van den Heuvel E, Fritel X, Southall K, Jutai J, Rajabali S et al. Continence Across Continents To Upend Stigma and Dependency (CACTUS-D): study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials 2015; 16: 565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tannenbaum C, Agnew R, Benedetti A, Thomas D, van den Heuvel E. Effectiveness of continence promotion for older women via community organisations: a cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open 2013; 3: e004135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yalcin I, Bump RC. Validation of two global impression questionnaires for incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003; 189: 98–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brazier JE, Roberts J. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Med Care 2004; 42: 851–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tannenbaum C, Brouillette J, Corcos J. Rating improvements in urinary incontinence: do patients and their physicians agree? Age Ageing 2008; 37: 379–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saliba D, Elliott M, Rubenstein LZ, Solomon DH, Young RT, Kamberg CJ et al. The Vulnerable Elders Survey: a tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49: 1691–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wagner TH, Patrick DL, Bavendam TG, Martin ML, Buesching DP. Quality of life of persons with urinary incontinence: development of a new measure. Urology 1996; 47: 67–71. ; discussion 71–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire (ICIQ) ICIQ- FLUTS Module. Available at http://www.iciq.net/ICIQ.FLUTS.html Accessed December 24, 2018.

- 12. Holroyd-Leduc JM, Tannenbaum C, Thorpe KE, Straus SE. What type of urinary incontinence does this woman have? JAMA 2008; 299: 1446–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Halme AS, Tannenbaum C. Performance of a Bayesian approach for imputing missing data on the SF-12 health-related quality of life measure. Value Health 2018; 21: 1406–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Halme AS, Fritel X, Benedetti A, Eng K, Tannenbaum C. Implications of the minimal clinically important difference for health-related quality-of-life outcomes: a comparison of sample size requirements for an incontinence treatment trial. Value Health 2015; 18: 292–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eldridge SM, Ashby D, Kerry S. Sample size for cluster randomized trials: effect of coefficient of variation of cluster size and analysis method. Int J Epidemiol 2006; 35: 1292–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bourgeois FT, Olson KL, Tse T, Ioannidis JP, Mandl KD. Prevalence and characteristics of interventional trials conducted exclusively in elderly persons: a cross-sectional analysis of registered clinical trials. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0155948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Diokno AC, Newman DK, Low LK et al. Effect of group-administered behavioral treatment on urinary incontinence in older women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2018; 178: 1333–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morris V, Wagg A. Lower urinary tract symptoms, incontinence and falls in elderly people: time for an intervention study. Int J Clin Pract 2007; 61: 320–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Batchelor FA, Dow B, Low MA. Do continence management strategies reduce falls? A systematic review. Australas J Ageing 2013; 32: 211–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Agnew R, van den Heuvel E, Tannenbaum C. Efficiency of using community organisations as catalysts for recruitment to continence promotion trials. Clin Trials 2013; 10: 151–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Neumann PJ, Cohen JT. QALYs in 2018—advantages and concerns. JAMA 2018; 319: 2473–74. 10.1001/jama.2018.6072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kanesarajah J, Waller M, Whitty JA, Mishra GD. The relationship between SF-6D utility scores and lifestyle factors across three life stages: evidence from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. Qual Life Res 2017; 26: 1507–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stewart ST, Cutler DM, Rosen AB. Comparison of trends in U.S. health-related quality of life over the 2000’s using the SF-6D, HALex, EQ-5D, and EQ-5D visual analog scale versus a broader set of symptoms and impairments. Med Care 2014; 52: 1010–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hopman WM, Berger C, Joseph L et al. The natural progression of health-related quality of life: results of a five-year prospective study of SF-36 scores in a normative population. Qual Life Res 2006; 15: 527–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]