Abstract

Objective

Associations between suicidality and lipid dysregulation are documented in mental illness, but the potential role of leptin remains unclear. We examined the association between leptin and suicidal behaviour in schizophrenia, together with the influence of other clinical and biological indices.

Method

We recruited a sample of 270 participants with schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses. Blood samples were analysed for leptin, while symptom severity was assessed by Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) and Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS‐C). Patients' history of suicidal behaviour was categorized into three subgroups based on IDS‐C suicide subscale: No suicidal behaviour, mild/moderate suicidal behaviour and severe suicidal behaviour with/without attempts.

Results

Mild/moderate suicidal behaviour was present in 17.4% and severe suicidal behaviour in 34.8%. Both groups were significantly associated with female gender (OR = 6.0, P = 0.004; OR = 5.9, P = 0.001), lower leptin levels (OR = 0.4, P = 0.008; OR = 0.5, P = 0.008) and more severe depression (OR = 1.2, P < 0.001; OR = 1.1, P < 0.001) respectively. Smoking (OR = 2.6, P = 0.004), younger age of onset (OR = 0.9, P = 0.003) and less use of leptin‐increasing medications (OR = 0.5, P = 0.031) were associated with severe/attempts group, while higher C‐reactive protein CRP (OR = 1.3, P = 0.008) was associated with mild/moderate group.

Conclusion

Lower leptin levels were associated with higher severity of suicidal behaviour in schizophrenia.

Keywords: suicide, schizophrenia, depression, leptin, lipid

Significant outcomes.

After adjusting for potential confounding factors (i.e. age, sex, BMI, smoking, and medications), the association between leptin and severity of suicidal behaviour remained significant. The finding suggests potential biological mechanisms in the development of suicidal behaviour that should be followed up in future studies.

Increased risk of suicidal behaviour (both moderate and severe groups) was associated with female gender, smoking, early age of onset and severe depression.

Lower use of psychotropic medications that are known to increase leptin levels (i.e. clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine and mirtazapine) was associated with severe suicidal behaviour.

Limitations.

The study was observational with a cross‐sectional design, and we can neither assume the direction of the association between leptin and suicidal behaviour nor conclude regarding causality.

The lack of a detailed psychometric test assessing suicidality prevents us from in‐depth exploration of associations to other phenomena, such as the risk of violent suicide.

We have not included a healthy control group since suicidal behaviour is sporadic in the healthy general population.

Introduction

Patients with schizophrenia have significantly higher mortality rates than the general population 1, with a recent systematic review estimating an average of 14.5 years of potential life lost 2. Lifetime suicide risk in schizophrenia is estimated to be around 4.9% 3. The proportion of increased mortality rates attributable to suicide, however, varies across different studies, from 0% to 46% of all causes of death 4. Since suicidal behaviour is highly complex phenomenon, many studies have investigated both clinical and biological risk factors for suicide in this patient group.

Interestingly, some clinical risk factors for suicide were found to be disease‐specific while others were similar to those found in the general population 5. The systematic review of Hor and Taylor 6 identified 51 studies concerning risk of suicide in schizophrenia published since 2004. The authors highlighted several common and disease‐specific clinical factors with strong evidence of increased risk, and these included depressive symptoms, the presence of active positive symptoms, lower level of negative symptoms, the presence of insight, comorbid substance use, past individual and family history of suicide.

Studies of potential biological risk factors for suicide in general over the last two decades have included investigations of the role of inflammatory cytokines and lipid dysregulation. A recent systematic review of 22 studies indicated that elevated interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) and reduced IL‐2 were observed in patients with suicide attempts 7. Wu and colleagues conducted a meta‐analysis including 65 studies, highlighting the potential role of lipid dysregulation. The authors found significantly lower serum levels of total cholesterol (TC) and low‐density lipoproteins (LDL) in suicidal patients compared to non‐suicidal patients and healthy controls 8. These findings highlight the possible underlying role of lipid disturbances in the pathophysiology of suicide in schizophrenia.

Leptin is a peptide hormone synthesized mainly from adipose tissue. From its discovery by Zhang and colleagues 9 in 1994, the effects of leptin on the brain were initially seen as limited to the homeostatic regulation of feeding and energy consumption through its action on hypothalamus 10, 11. Recently, it has become clear that leptin has many other brain regulatory functions that also involve neuroendocrine, neuroinflammatory and neurodevelopmental processes 12, 13, 14. These functions are mainly mediated through the widely distributed leptin receptors in the human brain, located in the hypothalamic nuclei, hippocampus, amygdala and cortex 15. Leptin receptors are also present throughout the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, an important area for regulation of stress and emotional response 16. Moreover, leptin has been hypothesized to exert modulatory actions on both dopaminergic and serotonergic systems 17, 18.

These emerging findings from preclinical studies have encouraged research on potential links between leptin dysregulation and clinical psychopathology 19, including studies of the association between serum leptin levels and symptom profiles of schizophrenia. The results are however conflicting. A few studies show that leptin levels are increased, not only in patients using atypical antipsychotics 20 but also in drug‐free 21 and drug naive subjects 22. However, another study reported decreased leptin levels in patients with schizophrenia, particularly in patients with severe suicidal behaviour i.e. suicide attempts 23. The role of leptin, a potential lipid‐regulation associated biomarker, has however been infrequently investigated in suicide research.

Aims of the study

The current study has the primary aim to investigate the association between leptin levels and suicidal behaviour in a representative clinical sample of patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, to test the hypothesis that lower levels of serum leptin are associated with increased severity of suicidal behaviour. A secondary aim is to assess other potential clinical and biological indices that could be associated with suicidal behaviour in the sample.

Material and methods

Participants

Subjects were recruited through the ongoing Norwegian Thematically Organized Psychosis (TOP) study. The project started in 2003 as a multicentre study involving the major hospitals of greater Oslo and is approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics. Inclusion criteria are being 18–65 years of age, meeting the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia and bipolar disorders according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐IV; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) and being able and willing to give a written informed consent to participate. Participants with a history of significant head injury, neurological disorder, mental retardation and autoimmune disease were excluded.

For the present study, we included only subjects with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders diagnosed according to DSM‐IV with available serum leptin measurements. We then excluded patients with C‐reactive protein (CRP) above 10 mg/L (n = 31) and with missing data for the main research question of the study (i.e. symptoms scales and information about suicidal behaviour) from the analyses. The final sample consisted of 270 participants with the following diagnostic distribution: schizophrenia (n = 145), schizoaffective disorder (n = 43), schizophreniform disorder (n = 13) and psychosis not otherwise specified (NOS; n = 69).

Clinical variables

Sociodemographic and clinical data were collected from clinical interviews and medical records. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV Axis I Disorders (SCID‐I) was used to confirm the diagnosis 24. We calculated duration of illness as the age at time of the inclusion minus the age of onset of the first psychotic episode. Standardized procedures were used for physical examination that included height, weight and body mass index (BMI). The following psychometric rating scales were used to assess symptom severity: the Structured Interview for the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) 25 and clinician‐rated Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS‐C) 26. The grouping of patients based on the severity of suicidal behaviour was derived from IDS‐C item 18 on suicide with the addition of information about a history of at least one‐lifetime suicidal attempt from the clinical interviews and hospital records.

Item 18 of IDS‐C measures suicidal severity using a four‐point scale (0–3). Here, (0) is scored for those who do not think of suicide or death; (1) is scored for those who feel that life is empty or is not worth living; (2) is scored for those who thinks of suicide/death several times in a week; and finally, (3) is scored for those who thinks of suicide/death several times a day, or has suicidal plans or suicidal attempts. Based on this and lifetime history of attempts, we categorized the patients into three subgroups: no suicidal behaviour (score = 0 on IDS‐C/item 18 and no history of attempts), mild to moderate suicidal behaviour (score from 1 to 2 on IDS‐C/item 18 and no history of attempts) and severe suicidal behaviour with or without attempts (score = 3 on IDS‐C/item 18 and at least one history of attempt) henceforth ‘severe suicidal behaviour'.

Biochemical variables

Fasting venous blood samples were obtained in the morning. Measurement and analysis of total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), low‐density lipoproteins (LDL) and standard C‐reactive protein (CRP) were conducted at the Department of Medical Biochemistry, Oslo University Hospital. Leptin concentrations were measured using 125I‐labelled human leptin radioimmunoassay (HL‐81K Kit; EMD Millipore Corporation) and analysed at the Hormone Laboratory, Department of Endocrinology, Aker University Hospital.

Medications

Studies have reported that psychotropic medications may increase leptin levels, in particular, olanzapine, clozapine, quetiapine and mirtazapine 27, 28, 29. In order to adjust for potential confounding effects of psychotropic medications in the statistical analysis, we used data from the clinical interview and medical records together with measurements of the serum level of different antipsychotic drugs. Based on this, we dichotomized the sample into two subgroups: the group using psychotropic medications affecting leptin (olanzapine, clozapine, quetiapine and mirtazapine) vs. the group using other psychotropic medications/not using any psychotropic medications.

Statistical analysis

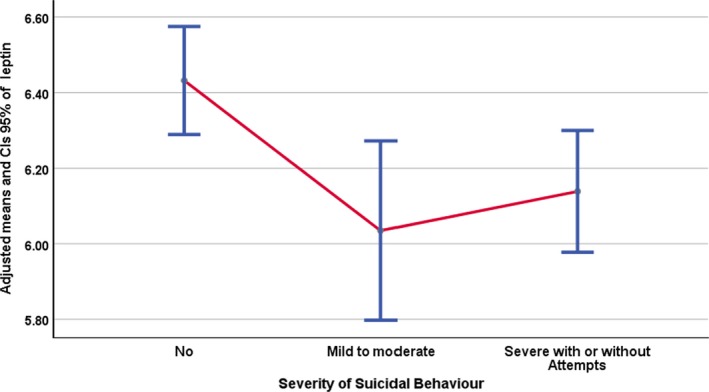

The data were analysed using the statistical package for Social Sciences (IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp., 2016). The statistical significant level was preset to P < 0.05 (two‐tailed). Variables were presented as numbers (percentages) or means (± standard deviation) as appropriate. Substitution with mean was used for missing data for years of education (five patients missing this information). Leptin levels were log‐transformed for all analyses due to markedly skewed distribution. To investigate the association between leptin and suicidal behaviour, with other sociodemographic, clinical and biochemical characteristics, we started out investigating their bivariate associations using Pearson's r for normally distributed continuous variables as shown in Table 2. We then used multivariate multinomial logistic regression to estimate the odds ratio (OR) of being in the mild to moderate or the severe suicidal groups respectively, compared to the no suicidality group. We included all potential covariates with known clinical associations to suicidal behaviour or to variation in leptin levels according to previous studies, in addition to those showing significant bivariate associations with both leptin and suicidal behaviour in our current sample. (i.e. age, gender, daily tobacco smoking, BMI, age of onset, medication affecting leptin, IDS – C total score without suicide item 18 and CRP; Table 3). Lipid measures (i.e. TC, TG and LDL) were not entered into the multivariate analysis to avoid potential multicollinearity issues since they were highly correlated with BMI and CRP. We then added (log) leptin levels at the last step of the multivariate analysis. To illustrate the distribution of (log) leptin levels across groups, adjusted for covariates, we used an analysis of covariance (ancova) to produce adjusted means for the error bar graph shown in Fig. 1.

Table 2.

Bivariate associations of leptin and suicide

| Leptin† | Suicidal behaviour‡ | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.1 | −0.1 |

| Female sex | 0.5** | 0.2* |

| Daily tobacco smoking | −0.1 | 0.2** |

| Medication affecting leptin§ | 0.0 | −0.1* |

| BMI | 0.5** | −0.1 |

| Age of onset | −0.0 | −0.3** |

| PANSS – positive | −0.1 | 0.2** |

| PANSS – negative | −0.0 | 0.0 |

| IDS – C¶ | 0.1 | 0.3** |

| TC | 0.2** | −0.1 |

| LDL | 0.2** | −0.1 |

| TG | 0.2** | 0.0 |

| CRP | 0.4** | 0.0 |

BMI, body mass index; CRP, C‐reactive protein; IDS‐C, Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology clinician‐rated; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

†log‐transformed leptin score.

‡Suicidal behaviour is classified according to item 18 in IDS‐C and lifetime history of suicidal attempts.

§Psychotropic medications affecting leptin are clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine and mirtazapine.

¶IDS – C total score without suicidal ideation item 18.

Table 3.

Multinominal logistic regression analysis

| B (SE) | Wald | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Suicidal behaviour (mild to moderate) vs. None | |||||

| Intercept | 0.2 (1.7) | ||||

| Age | −0.0 (0.0) | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Female sex | 1.8 (0.68) | 8.2** | 6.0 | 1.8 | 20.5 |

| Daily tobacco smoking | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 2.8 |

| BMI | 0.0 (0.1) | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.2 |

| Age of onset | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| Medication affecting leptin | −0.7 (0.4) | 2.8 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 1.1 |

| CRP | 0.2 (0.1) | 7.0** | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.5 |

| IDS‐C total (without suicide item 18) | 0.1 (0.0) | 47.7** | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Leptin | −0.9 (0.4) | 7.0** | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| Suicidal behaviour (severe and/or attempts) vs. None | |||||

| Intercept | 1.9 (1.3) | ||||

| Age | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| Female sex | 1.8 (0.5) | 12.1** | 5.9 | 2.2 | 16.0 |

| Daily tobacco smoking | 1.0 (0.3) | 8.1** | 2.6 | 1.4 | 5.1 |

| BMI | 0.1 (0.1) | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| Age of onset | −0.1 (0.0) | 8.8** | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Medication affecting leptin | −0.7 (0.3) | 4.7* | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| CRP | 0.1 (0.1) | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.2 |

| IDS‐C total (without suicide item 18) | 0.1 (0.0) | 18.5** | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| Leptin | −0.7 (0.3) | 7.0** | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.8 |

R 2 = 0.4 (Cox & Snell), 0.4 (Nagelkerke). Model χ2 (18) = 127.2, P < 0.001

BMI, body mass index; CRP, C‐reactive protein; IDS‐C, Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology clinician‐rated.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

Figure 1.

Error bar graph of adjusted leptin levels in relation to severity of suicidal behaviour.

Results

Two hundred seventy patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders were participated, out of whom 161 (59.6%) were male. Mean age was 30.7 (±10.1) and duration of illness was 8.2 (±8.4) years. Around half of the patients (52.2%) had either mild or severe suicidal behaviour. Their demographic, clinical and biochemical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the sample

| N = 270 | |

|---|---|

| Age (years), M (SD) | 30.7 (10.1) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 161 (59.6) |

| Education (years), M (SD) | 12.8 (2.9) |

| Caucasian ethnicity, n (%) | 218 (80.7) |

| Daily tobacco smoking, n (%) | 157 (58.1) |

| Age of onset (years), M (SD) | 22.6 (8.6) |

| Schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses, n (%) | |

| Schizophrenia | 145 (53.7) |

| Schizophreniform | 13 (4.8) |

| Schizoaffective | 43 (15.9) |

| Psychosis NOS | 69 (25.6) |

| Psychotropic medications, n (%) | |

| Use on regular basis | 328 (88.2) |

| Psychotropic medications affecting leptin* | 141 (37.9) |

| PANSS – positive, M (SD) | 15.1 (5.1) |

| PANSS – negative, M (SD) | 15.8 (6.4) |

| IDS‐C total, M (SD) | 19.3 (12.6) |

| Suicidal behaviour†, n (%) | |

| No | 129 (47.8) |

| Mild to moderate | 47 (17.4) |

| Severe with or without attempts | 94 (34.8) |

| BMI (kg/m2), M (SD) | 26.1 (5.1) |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l), M (SD) | 5.3 (1.1) |

| LDL (mmol/l), M (SD) | 3.2 (1.0) |

| Triglyceride (mmol/l), M (SD) | 1.5 (0.9) |

| Leptin‡(mg/l), M (SD) | 6.3 (1.0) |

| CRP (mg/dl), M (SD) | 3.3 (2.8) |

BMI, body mass index; CRP, C‐reactive protein; IDS‐C, Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology clinician‐rated; LDL, low‐density lipoproteins; M, mean; NOS, not otherwise specified; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; SD, standard deviation.

Psychotropic medications affecting leptin are clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine and mirtazapine.

Suicidal behaviour is classified according to item 18 in IDS‐C and lifetime history of suicidal attempts.

log‐transformed leptin score.

In the bivariate analyses, we found serum leptin levels to be positively and statistically significantly correlated with female gender (r = 0.5, P < 0.001), BMI (r = 0.5, P < 0.001), lipid levels [TC (r = 0.2, P < 0.001); LDL (r = 0.2, P = 0.004); TG (r = 0.2, P = 0.001)] and CRP (r = 0.4, P < 0.001). Severity of suicidal behaviour was positively correlated with female gender (r = 0.2, P = 0.011), daily tobacco smoking (r = 0.2, P = 0.002), positive symptoms (r = 0.2, P = 0.001), depression (r = 0.3, P < 0.001), negatively correlated with age of onset (r = −0.3, P < 0.001) and use of psychotropic drugs that are known to increase leptin level (r = −0.1, P = 0.019) (Table 2).

The multivariate multinomial logistic regression analysis showed that female gender (OR = 6.00, 95% CI = 1.8–20.5; OR = 5.9, 95% CI = 2.2–16.0 respectively) and higher depressive symptoms (OR = 1.2, 95% CI = 1.1–1.2; OR = 1.1, 95% CI = 1.0–1.1 respectively) statistically significantly increased the risk of being in the mild to moderate or severe suicidal behaviour groups (compared to the no suicidal behaviour group).

Importantly, lower levels of leptin also significantly increased the risk of being in the mild to moderate or severe suicidal behaviour groups (OR = 0.4, 95% CI = 0.2–0.8; OR = 0.5, 95% CI = 0.3–0.8 respectively). In addition, higher CRP levels (OR = 1.3, 95% CI = 1.1–1.5) increased the risk of being in the mild to moderate suicidal behaviour group, while daily tobacco smoking (OR = 2.6, 95% CI = 1.4–5.1), younger age of onset (OR = 0.9, 95% CI = 0.9–1.0) and less use of medications affecting leptin (i.e. clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine or mirtazapine; OR = 0.5, 95% CI = 0.3–0.9) increased the risk of being in the severe suicidal behaviour group. The pseudo‐R 2 (Cox and Snell) for the analysis was 0.38, and the detailed regression weights are found in Table 3.

Finally, participants with both mild to moderate and severe suicidal behaviour had significantly lower adjusted levels of leptin compared to participants with no suicidal behaviour [F (2, 260) = 4.75, P = 0.009, partial η2 = 0.035]. Adjusted means and 95% CIs error bar of adjusted leptin levels for the suicide severity groups are shown in Fig. 1.

Discussion

The main finding of the current study is that lower levels of leptin were associated with increased risk of suicidal behaviour in schizophrenia spectrum patients, also after adjusting for age, sex, smoking, BMI and psychotropic medications affecting leptin. This finding is in line with previous findings of Atmaca and colleagues, who reported lower levels of leptin in schizophrenia patients with suicidal attempts, compared to patients without attempts 23 and in patients with severe mental disorders and suicide attempts compared to healthy controls 30 respectively.

The contradictory findings concerning leptin levels and suicidal behaviour in schizophrenia from other previous studies could be explained by the potential confounding influence of factors (i.e. age, sex, BMI, dietary habits, smoking, age of onset and duration of illness) that may act on leptin levels in both mentally ill patients and healthy individuals 31, 32, 33, 34. We here, however, found that lower leptin levels were significantly associated with moderate and severe suicidal behaviour (compared to no suicidal behaviour) also after adjustments for these factors.

A relationship between depression, suicidal behaviour and low brain leptin has previously been found in analyses of cerebral venous blood in patients with major depressive disorders and mRNA from post‐mortem CNS tissue from patients with completed suicide 35. Recent and emerging evidence supports the notion that leptin could be an essential component of the pathophysiology of depression and suicide 36. First, the presence of leptin receptors in brain areas closely related to depression neurobiology such as the amygdala and the hippocampus, together with the potential hippocampal synaptic neuroplasticity induced by leptin documented in recent animal studies, supports this hypothesis 37. Second, it has been suggested that leptin has a modulatory effect on HPA axis activity in the hypothalamus and subsequently affect response to stress 16. Third, evidence from animal studies shows a potential modulatory role of leptin on serotonin through its action on nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and nitric oxide (NO) production, which could affect serotonin reuptake 38 and activation 39. In addition, NO levels are found to be high in schizophrenia 40. The lack of inhibitory effects of leptin on NO could aggravate the serotonin dysregulation in schizophrenia in turn affecting mood, impulsivity and self‐regulation. Thus, the serotonergic pathway, in particular, could be considered the main pathophysiological link between leptin, mood, psychotic disorders and associated suicidal behaviour 41.

Furthermore, the interaction between adiposity and inflammation has been linked to leptin in several studies on depression 42. Interestingly, our finding supports this potential link and extends it to suicidal behaviour. We found that leptin levels were significantly positively correlated with CRP and BMI, and that CRP was associated with mild to moderate suicidal behaviour. The lack of any direct association between suicidal behaviour and BMI in our sample could be understood in terms of the recent findings of population‐based studies. These studies indicated that suicidal behaviour is higher among underweight individuals (BMI < 20 kg/m2) and people with extreme obesity (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2) which indicate a U‐shaped or curvilinear relationship 43, 44. This complex type of relationship is difficult to investigate in our sample, which mainly comprised individuals with an average BMI with a few overweight exceptions.

It is noteworthy that the use of specific psychotropic medications (i.e. clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine and mirtazapine) could increase leptin levels 28, 29. One of the interesting findings from our analyses is that less use of these medications was associated with severe suicidal behaviour. Clozapine is the only antipsychotic drug that has US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for treatment of suicidal behaviour 45, at the same time as clozapine use is associated with weight gain and increased leptin levels 46. This finding raises the possibility of a potential pathophysiological role of leptin in suicidal behaviour processes, linked to other underlying mechanisms such as adiposity and inflammation, which needs further investigation.

Major strengths of this study include the well‐characterized and representative sample of schizophrenia spectrum disorders patients, together with the detailed clinical, biochemical and medication records that allowed us to adjust for potential confounders adequately. Major limitations are the cross‐sectional design that does not allow us to conclude about the directionality of the association between leptin and suicidality. Moreover, the lack of specific psychometric assessment of suicidality and its related aspects prevent us from exploring in‐depth associations including the use of violent means in attempts 30. Finally, we did not include healthy controls in the current study, as they have very low levels of suicidal behaviour and the main research question is targeting the association between leptin levels and suicidal behaviour.

In summary, this study indicates an inverse association between leptin and severity of suicidal behaviour in schizophrenia. Proper assessment of depression together with the use of psychotropic drugs affecting leptin could have a beneficial role in the management of suicide risk. Future studies should explore the interaction between leptin and inflammation, and its potential link to suicide, with particular emphasis on the role of depressive symptomatology. A better understanding of the complex phenomenon of suicidal behaviour is essential to improve prognosis and long‐term outcome of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank and acknowledge the patients for their participation in the study, the staff members at NORMENT who were involved in acquisition of data and the Department of Medical Biochemistry at Oslo University Hospital for performing analyses of blood samples.

Funding

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7‐PEOPLE‐2013‐COFUND) under Grant agreement no. 609020‐Scientia Fellows. In addition, the study was supported by grants from Stiftelsen KG Jebsen, the Research Council of Norway (#223273, # 248778) and the South East Norway Health Authority (#2017‐112).

Declaration of interest

OAA has received speaker's honorarium from Lundbeck. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Gohar SM, Dieset I, Steen NE, Mørch RH, Vedal TSJ, Reponen EJ, Steen VM, Andreassen OA, Melle I. Association between leptin levels and severity of suicidal behaviour in schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

References

- 1. Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:1123–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hjorthoj C, Sturup AE, McGrath JJ, Nordentoft M. Years of potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2017;4:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Palmer BA, Pankratz VS, Bostwick JM. The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia: a reexamination. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bushe CJ, Taylor M, Haukka J. Mortality in schizophrenia: a measurable clinical endpoint. J Psychopharmacol 2010;24(4 Suppl):17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hawton K, Sutton L, Haw C, Sinclair J, Deeks JJ. Schizophrenia and suicide: systematic review of risk factors. Br J Psychiatry 2005;187:9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hor K, Taylor M. Suicide and schizophrenia: a systematic review of rates and risk factors. J Psychopharmacol 2010;24(4 Suppl):81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gananca L, Oquendo MA, Tyrka AR, Cisneros‐Trujillo S, Mann JJ, Sublette ME. The role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of suicidal behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016;63:296–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wu S, Ding Y, Wu F, Xie G, Hou J, Mao P. Serum lipid levels and suicidality: a meta‐analysis of 65 epidemiological studies. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2016;41:56–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature 1994;372:425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Prolo P, Wong ML, Licinio J. Leptin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 1998;30:1285–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morton GJ, Meek TH, Schwartz MW. Neurobiology of food intake in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 2014;15:367–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ahima RS, Osei SY. Leptin signaling. Physiol Behav 2004;81:223–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bouret SG. Neurodevelopmental actions of leptin. Brain Res 2010;1350:2–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Valleau JC, Sullivan EL. The impact of leptin on perinatal development and psychopathology. J Chem Neuroanat 2014;61–62:221–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Couce ME, Burguera B, Parisi JE, Jensen MD, Lloyd RV. Localization of leptin receptor in the human brain. Neuroendocrinology 1997;66:145–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roubos EW, Dahmen M, Kozicz T, Xu L. Leptin and the hypothalamo‐pituitary‐adrenal stress axis. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2012;177:28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yadav VK, Oury F, Suda N et al. A serotonin‐dependent mechanism explains the leptin regulation of bone mass, appetite, and energy expenditure. Cell 2009;138:976–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Burghardt PR, Love TM, Stohler CS et al. Leptin regulates dopamine responses to sustained stress in humans. J Neurosci 2012;32:15369–15376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zupancic ML, Mahajan A. Leptin as a neuroactive agent. Psychosom Med 2011;73:407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sentissi O, Epelbaum J, Olie JP, Poirier MF. Leptin and ghrelin levels in patients with schizophrenia during different antipsychotics treatment: a review. Schizophr Bull 2008;34:1189–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arranz B, Rosel P, Ramirez N et al. Insulin resistance and increased leptin concentrations in noncompliant schizophrenia patients but not in antipsychotic‐naive first‐episode schizophrenia patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:1335–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang HC, Yang YK, Chen PS, Lee IH, Yeh TL, Lu RB. Increased plasma leptin in antipsychotic‐naive females with schizophrenia, but not in males. Neuropsychobiology 2007;56:213–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Atmaca M, Kuloglu M, Tezcan E, Ustundag B. Serum leptin and cholesterol levels in schizophrenic patients with and without suicide attempts. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2003;108:208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. First MB, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM‐IV axis I disorders‐patient edition (SCID I/P, version 2.0). New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Dept; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987;13:261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, Jarrett RB, Trivedi MH. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychol Med 1996;26:477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Birkenaes AB, Birkeland KI, Friis S, Opjordsmoen S, Andreassen OA. Hormonal markers of metabolic dysregulation in patients with severe mental disorders after olanzapine treatment under real‐life conditions. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2009;29:109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schilling C, Gilles M, Blum WF et al. Leptin plasma concentrations increase during antidepressant treatment with amitriptyline and mirtazapine, but not paroxetine and venlafaxine: leptin resistance mediated by antihistaminergic activity? J Clin Psychopharmacol 2013;33:99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Potvin S, Zhornitsky S, Stip E. Antipsychotic‐induced changes in blood levels of leptin in schizophrenia: a meta‐analysis. Can J Psychiatry 2015;60(3 Suppl 2):S26–S34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Atmaca M, Kuloglu M, Tezcan E, Ustundag B. Serum leptin and cholesterol values in violent and non‐violent suicide attempters. Psychiatry Res 2008;158:87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Al‐Harithy RN. Relationship of leptin concentration to gender, body mass index and age in Saudi adults. Saudi Med J 2004;25:1086–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Al Mutairi SS, Mojiminiyi OA, Shihab‐Eldeen AA, Al Sharafi A, Abdella N. Effect of smoking habit on circulating adipokines in diabetic and non‐diabetic subjects. Ann Nutr Metab 2008;52:329–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Herran A, Garcia‐Unzueta MT, Amado JA, de La Maza MT, Alvarez C, Vazquez‐Barquero JL. Effects of long‐term treatment with antipsychotics on serum leptin levels. Br J Psychiatry 2001;179:59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jow G‐M, Yang T‐T, Chen C‐L. Leptin and cholesterol levels are low in major depressive disorder, but high in schizophrenia. J Affect Disord 2006;90:21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eikelis N, Esler M, Barton D, Dawood T, Wiesner G, Lambert G. Reduced brain leptin in patients with major depressive disorder and in suicide victims. Mol Psychiatry 2006;11:800–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lu X‐Y. The leptin hypothesis of depression: a potential link between mood disorders and obesity? Curr Opin Pharmacol 2007;7:648–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shanley LJ, Irving AJ, Harvey J. Leptin enhances NMDA receptor function and modulates hippocampal synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci 2001;21:Rc186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chanrion B, Mannoury la Cour C, Bertaso F et al. Physical interaction between the serotonin transporter and neuronal nitric oxide synthase underlies reciprocal modulation of their activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:8119–8124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fossier P, Blanchard B, Ducrocq C, Leprince C, Tauc L, Baux G. Nitric oxide transforms serotonin into an inactive form and this affects neuromodulation. Neuroscience 1999;93:597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Herken H, Uz E, Ozyurt H, Akyol O. Red blood cell nitric oxide levels in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2001;52:289–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Farr OM, Tsoukas MA, Mantzoros CS. Leptin and the brain: influences on brain development, cognitive functioning and psychiatric disorders. Metabolism 2015;64:114–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Milaneschi Y, Simmons WK, van Rossum EFC, Penninx BW. Depression and obesity: evidence of shared biological mechanisms. Mol Psychiatry 2018;24:18–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gao S, Juhaeri J, Reshef S, Dai WS. Association between body mass index and suicide, and suicide attempt among British adults: the health improvement network database. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:E334–E342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Brown KL, LaRose JG, Mezuk B. The relationship between body mass index, binge eating disorder and suicidality. BMC Psychiatry 2018;18:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kasckow J, Felmet K, Zisook S. Managing suicide risk in patients with schizophrenia. CNS Drugs 2011;25:129–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tschoner A, Engl J, Rettenbacher M et al. Effects of six‐second generation antipsychotics on body weight and metabolism ‐ risk assessment and results from a prospective study. Pharmacopsychiatry 2009;42:29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]