Abstract

Disease‐associated proteins are thought to propagate along neuronal processes in neurodegenerative diseases. To detect disease‐associated prion protein (PrPSc) in the vagus nerve in different forms and molecular subtypes of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD), we applied 3 different anti‐PrP antibodies. We screened the vagus nerve in 162 sporadic and 30 genetic CJD cases. Four of 31 VV‐2 type sporadic CJD and 7 of 30 genetic CJD cases showed vagal PrPSc immunodeposits with distinct morphology. Thus, PrPSc in CJD affects the vagus nerve analogously to α‐synuclein in Parkinson disease. The morphologically diverse deposition of PrPSc in genetic and sporadic CJD argues against uniform mechanisms of propagation of PrPSc. Ann Neurol 2019;85:782–787

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) is a lethal and transmissible neurodegenerative disease. CJD has 3 major etiological forms: acquired, genetic, and the most frequent, sporadic. In sporadic CJD (sCJD), at least 6 different molecular subtypes are distinguished based on the polymorphism at codon 129 (methionine [M] or valine [V]) of the prion protein gene (PRNP) and the type of proteinase K–resistant prion protein (PrP) fragments detected by Western blot.1 Importantly, neuropathological examination, based on the analysis of the distribution of characteristic spongiform change and immunomorphology of disease‐associated PrP (PrPSc), reliably allows the recognition of molecular subtypes.2 Lesion profiles and clinical phenotypes are significantly different between molecular subtypes.2 Interestingly, VV‐2 and MV‐2 cases show prominent involvement of subcortical areas, including the brainstem.3

In acquired animal prion diseases, including scrapie in sheep, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle, and chronic wasting disease in deer, the medulla oblongata is thought to be a location where PrPSc reaches the central nervous system after being transported through the vagus nerve from the gastrointestinal tract.4, 5 In humans, the detection of PrPSc in the lymphoreticular system of the gastrointestinal tract supports the spreading concept from the periphery to the brain in variant CJD, which is associated with BSE.6 Furthermore, Iacono et al have suggested that involvement of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagal nerve might indicate an “environmental exposure” in sCJD.7

Prion diseases are model disorders for other, more frequent, neurodegenerative conditions. Prion‐like propagation of disease‐associated α‐synuclein and hierarchical involvement of brain regions is thought to be a central event in the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease (PD).8 Interestingly, α‐synuclein can be found in the gastrointestinal tract; therefore, the vagus nerve has been suggested as a route of α‐synuclein spreading to the brain.9 However, the direction of α‐synuclein propagation in the vagus nerve is still debated.10 In human prion disease, it has been suggested that accumulation of PrPSc in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve could be an indication for disease propagation outside of the brain.7, 11 To expand previous findings, we assessed the peripheral medullary segments of the vagus nerve in individuals suffering from sporadic and genetic forms of CJD.

Materials and Methods

Selection of the Cases

We recruited brain samples of definite CJD cases from 3 different cohorts. In 2 cases (1 sporadic and 1 T188K mutation; genetic CJD [gCJD]), postmortem samples from the gastrointestinal tract were also available. Samples derived from the Austrian Surveillance Center for Prion Diseases, Vienna, Austria, the Hungarian Surveillance Center for Prion Diseases, Budapest, Hungary, and the Neurological Tissue Bank of the Biobanc Hospital Clinic, August Pi i Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute, Barcelona, Spain. We also included 5 non‐CJD control cases from the Neurobiobank of the Institute of Neurology, Vienna, Austria. Samples were collected in the framework of National Prion Disease Surveillance systems with appropriate institutional board approvals.

Neuropathology

Five‐micrometer‐thick slices from formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded tissue blocks of the medulla oblongata were examined. Only those cases were included in the study where the peripheral (extracerebral and intracranial) segment of vagus nerve was present on Klüver‐Barrera–stained sections (Fig 1A, B). We first screened the sections using the 12F10 anti‐PrP antibody (Epitope: aa. 142–160; 1:1,000; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). In addition, we evaluated the peripheral segment of the hypoglossal nerve as well as the hypoglossal nucleus, the nucleus ambiguus, and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagal nerve for the presence of intraneuronal PrP deposits. For epitope retrieval, we applied autoclaving at 121°C for 10 minutes, immersion in 96% formic acid for 5 minutes, and treatment with proteinase K (5 μg/ml in TRIS buffer) at 37°C for 5 minutes, to eliminate the cellular PrP. In the case of a positive signal for PrPSc, we expanded immunostainings using 2 additional antibodies targeting different epitopes of the PrP (6H4; epitope: aa. 144–152; 1:500; Prionics, Schlieren, Switzerland; and KG9, epitope: aa. 140–180; 1:1,000; TSE Resource Centre, Roslin Institute, Edinburgh, UK). We defined a positive signal as a dark brown coarse aggregate inside the peripheral nerve fibers with at least 50 μm distance from the edge of the nerve parenchyma.

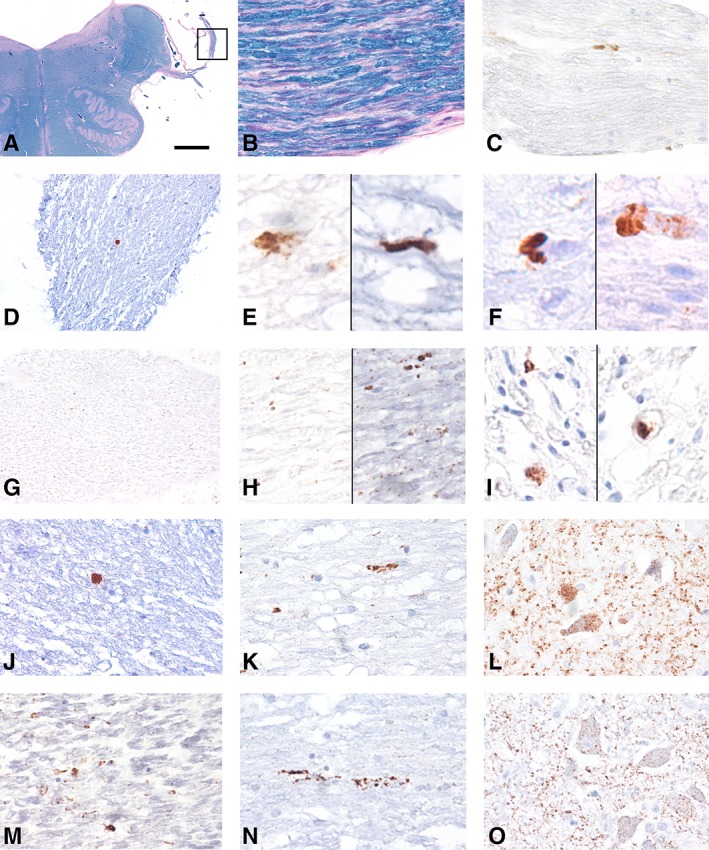

Figure 1.

Involvement of the vagus nerve in sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (sCJD) and genetic CJD (gCJD). (A) Cross‐section of the brainstem at the level of the medulla oblongata using Klüver–Barrera staining to show the peripheral emerging part of the vagus nerve (marked and enlarged in B) evaluated in this study. (C, D) Disease‐associated prion protein (PrPSc) deposits (antibody 12F10) in the vagus nerve in representative VV‐2 sCJD cases. (E, F) Coarse PrPSc deposits in different VV‐2 sCJD cases (all with antibody 12F10 except right image of E, which represents KG9 antibody). (G) Fine granular deposits of PrPSc in the vagus nerve of an E200K gCJD case (enlarged in H; all with antibody 12F10 except right image of H, which represents KG9 antibody). (I) PrPSc deposits in the vagus nerve of a T188K gCJD case (the left image is stained for 12F10 and the right for 6H4). (J–O) Immunostaining for 12F10 antibody in a VV‐2 sCJD (J–L) and an E200K gCJD (M–O) case showing the peripheral segment (J, M) and intracerebral course of the vagus nerve (K, N) and its dorsal motor nucleus (L, O). The bar in A represents 0 .4cm for A; 20 μm for B, C, and J–O; 40 μm for D and G; and 10 μm for E, F, H, and I. [Color figure can be viewed at www.annalsofneurology.org]

Statistical Analysis

We used a chi‐squared test to compare the frequencies of PrPSc immunoreactivity in the vagus nerves among the different molecular subtypes of sCJD and gCJD cases.

Results

We screened a total of 405 sCJD and gCJD cases; 192 contained the peripheral segment of the vagus nerve at the level of the medulla oblongata. From these cases, 127 sections (66%) contained the peripheral segment of the hypoglossal nerve, and in 169 (88%) the hypoglossal nucleus, 166 (86%) the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagal nerve, and 158 (82%) the nucleus ambiguus were evaluable. Following consensus classification,2 106 of 192 with peripheral vagus nerve were MM/MV‐1 sCJD, 31 VV‐2, 15 MV‐2, 9 MM‐2, and a single case was VV‐1. Thirty cases were classified as genetic prion diseases (19 E200K, 6 D178N‐FFI, 2 cases of 4 octapeptide repeat, and single cases of 5 octapeptide repeat, T188K, and P102L mutations). Fifty percent were female, and the median age at death was 66.2 years.

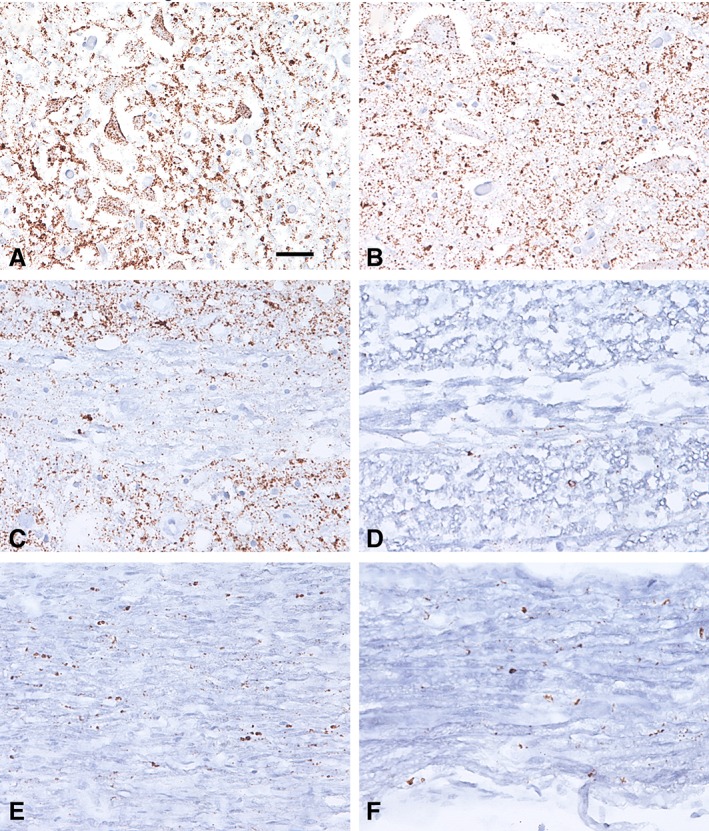

Eleven cases (5.7% of the cohort) showed PrPSc immunoreactivity in the peripheral segment of the intracranial portion of the vagus nerve. This included 4 of 31 (12.9%) VV‐2 sCJD and 7 of 30 (23.3%) gCJD cases. Six carried the E200K PRNP mutation (31.6% of E200K mutation cases). The single case with the T188K mutation was also PrPSc positive. Fine somatosynaptic PrP immunoreactivity was seen in the brainstem in different molecular subtypes, and coarser granular intraneuronal deposits were observed in the hypoglossal nucleus, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagal nerve, and the nucleus ambiguus only in VV‐2 (67.7–74.2% of cases in these nuclei), MV‐2 K (56.3–75%), and gCJD (54.8–61.3%) cases. Although the presence of PrPSc immunoreactivity in the vagus or hypoglossal nerve (only 2 cases with the E200K PRNP mutation) was associated with intraneuronal PrPSc in the ipsilateral corresponding nuclei (Fig 2), not all cases with intraneuronal PrPSc in the nuclei contained simultaneous immunoreactivity in the corresponding nerves (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Representative microphotographs of the dorsal motor vagal and hypoglossal nuclei and nerves in a genetic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease case with the E200K PRNP mutation. (A, B) Immunohistochemistry for prion protein (antibody 12F10) reveals diffuse synaptic neuropil staining and a granular intraneuronal immunoreactivity in the neurons of the dorsal nucleus of the vagal nerve (A) and the hypoglossal nucleus (B). (C–F) A granular pattern of immunoreactivity is also observed along the intramedullary (C, D) and extramedullary (E, F) segments of the vagal (C, E) and hypoglossal (D, F) nerves. The bar in A represents 35 μm for A and B and 50 μm for C–F. [Color figure can be viewed at www.annalsofneurology.org]

Table 1.

Number of Cases Showing PrPSc Immunoreactivity or Lack of PrPSc Immunoreactivity in Different Medullary Nuclei and the Vagal and Hypoglossal Nerves

| PrP IHC Positive | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PrP IHC Positive | Dorsal Vagus NU | Ambiguus NU | Hypoglossal NU | Hypoglossal Nerve | Vagus Nerve |

| Dorsal vagus NU | 51 | 50 | 2 | 11 | |

| Ambiguus NU | 55 | 48 | 2 | 11 | |

| Hypoglossal NU | 47 | 45 | 2 | 11 | |

| Hypoglossal nerve | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Vagus nerve | 11 | 11 | 11 | 2 | |

| PrP IHC Negative | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PrP IHC Positive | Dorsal Vagus NU | Ambiguus NU | Hypoglossal NU | Hypoglossal Nerve | Vagus Nerve |

| Dorsal vagus NU | 1 | 8 | 30 | 44 | |

| Ambiguus NU | 0 | 7 | 28 | 41 | |

| Hypoglossal NU | 0 | 0 | 27 | 37 | |

| Hypoglossal nerve | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vagus nerve | 0 | 45 | 0 | 1 | |

| PrP IHC Negative | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PrP IHC Negative | Dorsal Vagus NU | Ambiguus NU | Hypoglossal NU | Hypoglossal Nerve | Vagus Nerve |

| Dorsal vagus NU | 103 | 111 | 82 | 111 | |

| Ambiguus NU | 100 | 104 | 79 | 106 | |

| Hypoglossal NU | 108 | 101 | 87 | 119 | |

| Hypoglossal nerve | 80 | 77 | 85 | 124 | |

| Vagus nerve | 108 | 103 | 121 | 124 | |

IHC = immunohistochemistry; NU = nucleus; PrPSc = disease‐associated prion protein.

The morphology of the immunoreactivity in the vagal nerve differed between CJD subtypes. In the VV‐2 sCJD cases, we observed coarse aggregates within the extracerebral portion of the vagus nerve with all anti‐PrP antibodies (see Fig 1). In contrast, in the gCJD cases, the PrPSc immunoreactivity consisted of fine granular dots along the nerve in particular with the 12F10 and KG9 antibodies. The 6H4 antibody did not show unequivocal PrPSc immunoreactivity in E200K mutation cases. Importantly, we detected PrPSc deposits within the axons surrounded by the myelin sheath. The gastrointestinal samples of 2 of the genetic cases did not show PrPSc deposits. Finally, in control cases, we observed no PrPSc staining in the vagus nerve. In cases with positive PrPSc in the peripheral segment of the vagus nerve, deposits could be followed along its intraparenchymal medullary course up to the dorsal motor nucleus in both sporadic and genetic cases.

Chi‐squared test revealed significant differences between the molecular groups (p < 0.001). The frequency of PrPSc immunoreactivity in the vagus nerve was significantly higher in VV‐2 sCJD than in MM/MV‐1 (p = 0.002), but not after comparisons with VV‐1, MV‐2, MM‐2 sCJD and gCJD cases (p > 0.1). The frequency was higher in gCJD cases when compared to the MM/MV‐1 (p < 0.0001) and MV‐2 (p = 0.045) sCJD groups, but not when comparing with VV‐1 or MM‐2 groups (p > 0.1). No clinical data on autonomic disturbances were available.

Discussion

We show here that in CJD, PrPSc accumulates in the intracranial extracerebral segment of the vagus nerve. This finding expands previous observations on PrPSc deposition in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve.7 We had no access to extracranial portions of the nerve or peripheral organs, except for 2 genetic cases that did not exhibit disease‐associated PrP aggregates.

Abnormal protein processing and propagation are a common denominator of neurodegenerative diseases. Peripheral involvement of the autonomic nervous system has been studied in PD, where peripheral α‐synuclein aggregates have been detected throughout the body.12 Previous studies demonstrated limited or no peripheral involvement in human sporadic CJD with only discrete PrPSc deposits found in a few dorsal root ganglia, associated to Schwann cells of myelinated and unmyelinated fibers in the superficial peroneal nerve;13 they were also identified adaxonally in posterior root nerve fibers, but no labeling of the enteric nervous system has been reported.6, 14 Moreover, contrasting with α‐synuclein in PD, the optic nerve does not show PrPSc deposits in sCJD despite the involvement of further stations of the optic pathway.15

The higher frequency of PrPSc immunoreactivity in vagus nerve in VV‐2 cases compared with MM/MV‐1 cases could be attributed to the prominent subcortical pathology usually observed in this molecular subtype. The coarse morphology of PrPSc aggregates in VV‐2 CJD is somewhat different from the adaxonal and Schwann cell‐associated morphologies described previously13, 14 and may be associated with failure of either directional components of axonal transport. This morphology suggests similarities with α‐synuclein deposits in PD, where the olfactory and gastrointestinal tract have been discussed as potential catalysts of α‐synuclein misfolding and spread.9 The involvement of sympathetic nerves in the process of neuroinvasion has been proposed in experimental scrapie.16 In sCJD, involvement of peripheral organs, including the spleen and muscle17 and dorsal roots,14 has been interpreted as a spillover of cerebral PrPSc or centrifugal spread.14, 17 Whether PrPSc in the vagus nerve moves centrifugally toward the periphery or is transported centripetally toward the brain is still unclear. Noteworthy is the observation of α‐synuclein deposits in PD in further cranial nerves and their nuclei,18, 19 arguing for the concept that α‐synuclein accumulation in the brain can also spread to the periphery. Interestingly, the morphology with fine granular vagal PrPSc deposits was distinct in gCJD and also resembled adaxonal deposition (see Fig 1I). Although the accumulation of PrPSc in gCJD cases with E200K and T188K PRNP mutations most likely starts in the central nervous system, rarely the E200K mutation can be associated with early peripheral neuropathy.20, 21, 22 Together with recent reports on PRNP mutations associated with autonomic neuropathy and involvement of the gastrointestinal system,23, 24 an out to inward direction of propagation can be also considered, at least in some cases.

Because our study was retrospective and on archival tissue samples, there are inherent limitations. First, not all cases showed the segments of the vagus nerve emerging from the medulla oblongata and for some molecular subtypes the case numbers might be low; second, the entire course of the vagus nerve from the central nervous system to the periphery was not available; third, no peripheral organs innervated by the vagus had been systematically collected in our series; fourth, we could not evaluate specific autonomic symptoms or whether longer duration of illness was associated with more intense PrPSc immunoreactivity; and finally, we did not have the appropriate methodology to determine the anterograde or retrograde transport of PrPSc. However, our study expands previous observations restricted to medullary nuclei3, 7 and provides proof that PrPSc accumulation not only represents a local phenomenon but also involves corresponding cranial nerves. Furthermore, we suggest that the morphologically diverse deposition of PrPSc argues against a uniform propagation mechanism. These observations have implications for studies on other neurodegenerative conditions sharing prionlike pathogenic mechanisms, including α‐synucleinopathies.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. P.K., J.R., E.G., I.A., K.D., and G.G.K. contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data. P.K., J.R., E.G., and G.G.K. contributed to drafting the text and preparing the figures.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

Nothing to report.

Acknowledgment

The Austrian Reference Center for Human Prion Diseases is supported by the Federal Ministry of Labor, Social Affairs, Health, and Consumer Protection. E.G. holds a grant from the Medizinisch‐Wissenschaftlichen Fonds des Bürgermeisters der Stadt Wien (project no. 18097).

We thank brain donors and their relatives for generous tissue donation for research; and the Austrian, Hungarian, and Barcelona August Pi i Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute brain banks for sample and data procurement.

References

- 1. Parchi P, Giese A, Capellari S, et al. Classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease based on molecular and phenotypic analysis of 300 subjects. Ann Neurol 1999;46:224–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Parchi P, de Boni L, Saverioni D, et al. Consensus classification of human prion disease histotypes allows reliable identification of molecular subtypes: an inter‐rater study among surveillance centres in Europe and USA. Acta Neuropathol 2012;124:517–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Iwasaki Y, Hashizume Y, Yoshida M, et al. Neuropathologic characteristics of brainstem lesions in sporadic Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease. Acta Neuropathol 2005;109:557–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sigurdson CJ, Spraker TR, Miller MW, et al. PrP(CWD) in the myenteric plexus, vagosympathetic trunk and endocrine glands of deer with chronic wasting disease. J Gen Virol 2001;82(pt 10):2327–2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Keulen LJ, Bossers A, van Zijderveld F. TSE pathogenesis in cattle and sheep. Vet Res 2008;39:24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Head MW, Ritchie D, Smith N, et al. Peripheral tissue involvement in sporadic, iatrogenic, and variant Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease: an immunohistochemical, quantitative, and biochemical study. Am J Pathol 2004;164:143–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iacono D, Ferrari S, Gelati M, et al. Sporadic Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease: prion pathology in medulla oblongata—possible routes of infection and host susceptibility. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:396791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rub U, et al. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2003;24:197–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Braak H, Rub U, Gai WP, Del Tredici K. Idiopathic Parkinson's disease: possible routes by which vulnerable neuronal types may be subject to neuroinvasion by an unknown pathogen. J Neural Transm 2003;110:517–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lionnet A, Leclair‐Visonneau L, Neunlist M, et al. Does Parkinson's disease start in the gut? Acta Neuropathol 2018;135:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pomfrett CJ, Glover DG, Pollard BJ. The vagus nerve as a conduit for neuroinvasion, a diagnostic tool, and a therapeutic pathway for transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, including variant Creutzfeldt‐Jacob disease. Med Hypotheses 2007;68:1252–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Orimo S, Ghebremedhin E, Gelpi E. Peripheral and central autonomic nervous system: does the sympathetic or parasympathetic nervous system bear the brunt of the pathology during the course of sporadic PD? Cell Tissue Res 2018;373:267–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Favereaux A, Quadrio I, Vital C, et al. Pathologic prion protein spreading in the peripheral nervous system of a patient with sporadic Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease. Arch Neurol 2004;61:747–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hainfellner JA, Budka H. Disease associated prion protein may deposit in the peripheral nervous system in human transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Acta Neuropathol 1999;98:458–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rahimi J, Milenkovic I, Kovacs GG. Patterns of tau and alpha‐synuclein pathology in the visual system. J Parkinsons Dis 2015;5:333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Glatzel M, Heppner FL, Albers KM, Aguzzi A. Sympathetic innervation of lymphoreticular organs is rate limiting for prion neuroinvasion. Neuron 2001;31:25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Glatzel M, Abela E, Maissen M, Aguzzi A. Extraneural pathologic prion protein in sporadic Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1812–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kovacs GG, Breydo L, Green R, et al. Intracellular processing of disease‐associated alpha‐synuclein in the human brain suggests prion‐like cell‐to‐cell spread. Neurobiol Dis 2014;69:76–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Seidel K, Mahlke J, Siswanto S, et al. The brainstem pathologies of Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain Pathol 2015;25:121–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Antoine JC, Laplanche JL, Mosnier JF, et al. Demyelinating peripheral neuropathy with Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease and mutation at codon 200 of the prion protein gene. Neurology 1996;46:1123–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kovacs GG, Seguin J, Quadrio I, et al. Genetic Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease associated with the E200K mutation: characterization of a complex proteinopathy. Acta Neuropathol 2011;121:39–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Neufeld MY, Josiphov J, Korczyn AD. Demyelinating peripheral neuropathy in Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease. Muscle Nerve 1992;15:1234–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matsuzono K, Honda H, Sato K, et al. 'PrP systemic deposition disease': clinical and pathological characteristics of novel familial prion disease with 2‐bp deletion in codon 178. Eur J Neurol 2016;23:196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mead S, Gandhi S, Beck J, et al. A novel prion disease associated with diarrhea and autonomic neuropathy. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1904–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]