Key Points

Question

What is the association between immigration-policy concerns and the health outcomes in US-born Latino adolescents from immigrant families?

Findings

In this cohort study of 397 US-born adolescents in California, fear and worry about the personal consequences of current US immigration policy were associated with higher anxiety levels, sleep problems, and blood pressure changes. Reported anxiety statistically significantly increased after the 2016 presidential election, particularly among young people in the most vulnerable families.

Meaning

The current immigration policy and rhetoric appear to be associated with adverse mental health outcomes among US citizen children of immigrants.

Abstract

Importance

Current US immigration policy targets immigrants from Mexico and other Latin American countries; anti-immigration rhetoric has possible implications for the US-born children of immigrant parents.

Objective

To assess whether concerns about immigration policy are associated with worse mental and physical health among US citizen children of Latino immigrants.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study of cohort data from the Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas (CHAMACOS), a long-term study of Mexican farmworker families in the Salinas Valley region of California, included a sample of US-born adolescents (n = 397) with at least 1 immigrant parent. These adolescents underwent a health assessment before the 2016 presidential election (at age 14 years) and in the first year after the election (at age 16 years). Data were analyzed from March 23, 2018, to February 14, 2019.

Exposures

Adolescents aged 16 years self-reported their concern about immigration policy using 2 subscales (Threat to Family and Children’s Vulnerability) of the Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale (PIPES) instrument.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Resting systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and mean arterial pressure; body mass index; maternal- and self-reported depression and anxiety problems (using Behavioral Assessment System for Children, 2nd edition); self-reported sleep quality (using Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [PSQI]); and maternal rating of child’s overall health. All measures except sleep quality were assessed at both the aged-14-years and aged-16-years visits. Health outcomes at age 16 years and the change in outcomes between ages 14 and 16 years were examined among youth participants who reported low or moderate PIPES scores vs high PIPES scores.

Results

In the sample of 397 US-born Latino adolescents (207 [52.1%] female) and primarily Mexican American individuals, nearly half of the youth participants worried at least sometimes about the personal consequences of the US immigration policy (n = 178 [44.8%]), family separation because of deportation (177 [44.6%]), and being reported to the immigration office (164 [41.3%]). Those with high compared with low or moderate PIPES scores had higher self-reported mean anxiety T scores (5.43; 95% CI, 2.64-8.23), higher maternally reported anxiety T scores (2.98; 95% CI, 0.53-5.44), and worse PSQI scores (0.98; 95% CI, 0.36-1.59). Youth participants with high PIPES scores reported statistically significantly increased levels of anxiety over the 2 visits (adjusted mean difference-in-differences, 2.91; 95% CI, 0.20-5.61) and not significantly increased levels of depression (adjusted mean difference-in-differences, 2.63; 95% CI, –0.28 to 5.54).

Conclusions and Relevance

Fear and worry about the personal consequences of current US immigration policy and rhetoric appear to be associated with higher anxiety levels, sleep problems, and blood pressure changes among US-born Latino adolescents; anxiety significantly increased after the 2016 presidential election.

This study assesses health outcome and self-assessment data of teenaged Latino participants in the CHAMACOS study before and after the 2016 presidential election in the United States, which ushered in new immigration policy and rhetoric.

Introduction

Eighteen million children (or 25% of all children) in the United States live in immigrant families, most of whom originate from countries in Latin America.1 Although most of these young people are US-born citizens, 7.3% of school-aged children have at least 1 undocumented immigrant parent2; this proportion is higher in California (10.2%) and other immigrant destination states.

The United States has not offered large-scale, congressionally supported amnesty to undocumented immigrants since the 1990s.3 The 2012 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy offered transitory protections to undocumented immigrants brought to the country as minors. However, since the 2016 presidential election, US policy toward immigrants has turned notably hostile. The Trump Administration has suggested an end to birthright citizenship,4,5 characterized Mexican immigrants as criminals,6,7 championed the construction of a wall along the US-Mexico border,6,8,9 attempted to rescind DACA protections,10,11 and forcibly separated migrant children from their parents.12,13 These actions and statements have generated considerable anxiety in the immigrant community.14

Many studies have been conducted on the well-being of undocumented immigrants,15,16,17,18,19,20 but relatively few studies have focused on US citizen children of immigrant parents. Small, qualitative studies have suggested an association between US punitive immigration policy and family and economic instability, adverse growth and mental and physical health, and more limited access to health and social services.21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 A large cross-sectional study using 2000 to 2002 data found that US citizen children of undocumented mothers experienced more internalizing and externalizing problems compared with children of naturalized, documented, or US-born mothers.29 More recent data indicated that children of DACA-eligible mothers had fewer Medicaid mental health claims compared with children of non–DACA-eligible immigrants.30 Mothers from mixed-status undocumented families have also reported worse child health status compared with mothers from legal resident or citizen families.31

In the present study, we examined the association of US-born adolescent self-reported concern about immigration policy with their mental and physical health. We used data from the Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas (CHAMACOS), a study of primarily Mexican farmworker families in California. We used multiyear data to investigate the change in adolescent health status assessed before the 2016 presidential election (at age 14 years) and in the first year after the election (at age 16 years).

Methods

This study was approved by the University of California, Berkeley Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects. Written informed consent or assent was obtained from all study participants. Data were analyzed from March 23, 2018, to February 14, 2019.

Study Sample

The youth participants in the CHAMACOS study were born from 2000 through 2002 in the California agricultural region of Salinas Valley. Participants were enrolled in 2 waves. From October 1999 to October 2000, the first cohort was recruited: 601 pregnant women who spoke either the Spanish or English language, were 18 years of age or older, were under 20 weeks’ gestation, qualified for low-income health insurance (available to undocumented immigrants for prenatal care), and planned to deliver at a public hospital. These women delivered 536 live-born infants who remained in the study at birth.32 The second cohort was enrolled from January 2010 to September 2011 and consisted of 305 US-born children who were 9 years of age as well as their Spanish- or English-speaking mothers who had received prenatal care in Salinas Valley, qualified for low-income health insurance during pregnancy, and were aged 18 years or older at delivery.33

Of the 412 children who completed study visits at age 16 years between December 28, 2016, and January 8, 2018, we included 397 adolescents with at least 1 immigrant parent. Visits at age 14 years spanned from May 5, 2014, through August 22, 2016. At each visit, the mothers were interviewed in Spanish or English, the adolescents completed a questionnaire in English, and youth anthropometrics were measured.

Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale

The main independent variable was adolescent self-reported concerns about immigration policy at age 16 years, which were collected with a portion of the Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale (PIPES) instrument.34 PIPES was originally developed and validated in Arizona to assess the implication of state-level immigration policies for immigrant parents. The original Spanish-language PIPES included 24 items representing 4 factors. The version of PIPES we administered was in English and with all of the items from 2 subscales: (1) Threat to Family (worry about the impact of immigration policy, fear that you or a family member would be reported to immigration officials, and worry about family separation due to deportation) and (2) Children’s Vulnerability (stressed about family members being deported or detained, felt unsafe, emotionally upset, feared authorities, and difficulties focusing in school due to immigration policies). Questions were adapted from the parent-report to the adolescent self-report format. Items were rated on a 5-point scale, with 1 indicating never to 5 indicating always. Points were summed to generate the total PIPES score and separate subscale scores.

Outcome Measures

At the aged-14-years and aged-16-years visits, blood pressure (BP) was assessed with an automatic digital sphygmomanometer (Dinamap 9300 or Dinamap Carescape 100; Critikon). Resting systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured in triplicate. If any readings were elevated (>95th percentile for age and sex), a fourth measurement was taken on the other arm. We calculated the mean of the last 2 measurements for analysis. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was calculated as [(2 × DBP) + SBP] divided by 3. We categorized youth prehypertension or hypertension according to sex, age, and height.35

At both visits, adolescent barefoot height was measured in triplicate using a wall-mounted stadiometer, and mean measures were calculated for analysis. Weight was measured using a bioimpedance scale (TBF-300A; Tanita). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated and categorized as underweight (<5th percentile), normal (5th to <85th percentile), overweight (≥85th to <95th percentile), or obese (≥95th percentile).36

At both visits, mothers and adolescents completed parent-report and youth self-report versions of the Behavioral Assessment System for Children, 2nd edition, or BASC-2.37 The BASC-2 Depression and Anxiety subscales were analyzed as standardized T-score values and as a binary at-risk or clinically significant variable (T score ≥60).

At the aged-16-years visit only, adolescents completed an adapted version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)38 to report sleep quality in the preceding month. The PSQI scores could range from 0 to 21, with lower scores indicating better sleep. Poor sleep quality was defined as a score of 5 or higher.

At both visits, mothers rated their child’s health as excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. For this analysis, we analyzed the responses continuously (1 to 5). We also compared excellent or very good to good, fair, or poor responses.

Statistical Analysis

The distribution of PIPES scores was right skewed. We dichotomized total and subscale scores into either low or moderate (ie, a mean response of less than sometimes responses for all questions) or high (ie, a mean response of sometimes responses for all questions).34 We constructed separate multivariable regression models for each end point. Covariates were selected using directed acyclic graphs (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

We estimated the difference-in-differences over the 2-year study period between youth participants with high PIPES scores and youth participants with low or moderate PIPES scores using generalized estimating equations with an interaction term between binary PIPES and the study period. Specifically, we calculated the change from the aged-14-years visit to the aged-16-years visit separately within the low or moderate PIPES group and within the high PIPES group. Next, we calculated and reported the difference in these 2 within-group changes (ie, the difference in slopes). That is, we examined the additional change in outcomes in the high PIPES group above and beyond that experienced in the low or moderate PIPES group. All generalized estimating equations models used an exchangeable correlation structure and robust SEs.

Final covariates were coded as shown in Table 1 unless indicated. Covariates included youth sex; maternal educational level and number of years in the United States (≤5 years and >5 years) at delivery; and maternal marital status, maternal depression risk, and household poverty status at the aged-16-years visit. For change in outcome analyses between visits, we included time-varying covariates from the aged-14-years visit or before this time, including maternal depression risk at the aged-9-years visit as well as household poverty and marital status from the aged-14-years visit. Poverty status was calculated by dividing the mother-reported household income by the number of people supported compared with the US federal poverty index for that year.39 Mothers were deemed at risk for depression if their score on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale40 was 16 points or higher.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of US-Born Youth Participants With Low or Moderate or With High Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale (PIPES) Score.

| Variable | No. (%) | PIPES Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | P Value | |||

| Low or Moderatea | Highb | |||

| Youth sex | <.001 | |||

| Male | 190 (47.9) | 169 (53.7) | 21 (25.6) | |

| Female | 207 (52.1) | 146 (46.4) | 61 (74.4) | |

| Father’s country of birth | .31 | |||

| United States | 14 (3.6) | 13 (4.2) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Mexico | 365 (93.6) | 290 (92.7) | 75 (97.4) | |

| Other | 11 (2.8) | 10 (3.2) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Mother’s length of time in the United States at delivery, y | .06 | |||

| ≤1 | 90 (22.7) | 65 (20.6) | 25 (30.5) | |

| 2-5 | 106 (26.7) | 83 (26.4) | 23 (28.1) | |

| 6-10 | 101 (25.4) | 80 (25.4) | 21 (25.6) | |

| ≥11 | 79 (19.9) | 66 (21.0) | 13 (15.9) | |

| Entire life | 21 (5.3) | 21 (6.7) | 0 | |

| Mother’s age at delivery, y | .97 | |||

| 18-24 | 156 (39.3) | 123 (39.1) | 33 (40.2) | |

| 25-29 | 125 (31.5) | 101 (32.1) | 24 (29.3) | |

| 30-34 | 76 (19.1) | 60 (19.1) | 16 (19.5) | |

| 35-45 | 40 (10.1) | 31 (9.8) | 9 (11.0) | |

| Mother’s educational level | .14 | |||

| ≤6th Grade | 184 (46.3) | 138 (43.8) | 46 (56.1) | |

| 7-12th Grade | 132 (33.3) | 110 (34.9) | 22 (26.8) | |

| ≥High school graduate | 81 (20.4) | 67 (21.3) | 14 (17.1) | |

| Mother’s marital status at aged-16-y visit | .23 | |||

| Not married | 103 (25.9) | 86 (27.3) | 17 (20.7) | |

| Married or living as married | 294 (74.1) | 229 (72.7) | 65 (79.3) | |

| Household income at aged-16-y visit | .67 | |||

| At or below poverty level | 229 (57.7) | 180 (57.1) | 49 (59.8) | |

| Above poverty level | 168 (42.3) | 135 (42.9) | 33 (40.2) | |

| Mother’s depression at aged-16-y visit | .21 | |||

| No | 269 (67.9) | 218 (69.4) | 51 (62.2) | |

| Yes | 127 (32.1) | 96 (30.6) | 31 (37.8) | |

PIPES score of 8-23 corresponds to a mean of less than sometimes responses for all 8 questions (n = 315).

PIPES score of 24-40 corresponds to a mean of more than sometimes responses for all 8 questions (n = 82).

We never asked mothers directly about their immigration documentation status, but we created a proxy variable for likely status on the basis of the length of time the mother had been living in the United States by the time she delivered (we did not have this information for the father). If the mother had resided in the country for 5 years or less at delivery (between 2000 and 2002), she was likely undocumented given that the most recent major amnesty was enacted in 1995 (Immigration and Nationality Act, Section 245[i] Amnesty, 1994). We tested for effect modification by the mother’s likely documentation status and by youth sex.

All analyses were performed with Stata, version 14.2 (StataCorp LLC). Two-sided P = .05 or less was considered statistically significant. We presented 95% CIs. In interaction models, P = .20 or less from a likelihood ratio test was considered statistically significant.

Results

In total, 397 US-born Latino adolescents were included in this study. These youth participants (including more female [207 (52.1%)] than male [190 (47.9%)]) were primarily Mexican American (385 [98.2%] had a mother or father born in Mexico, and 337 [86.0%] had parents both born in Mexico), and the remainder of the sample had an immigrant parent born elsewhere in Central America. Almost half of the mothers had been living in the United States for 5 years or less at delivery and had a sixth grade education or less (Table 1). At the aged-14-years visit, most mothers were married or living as married and were living in poverty.

The items in the PIPES instrument that were the most endorsed by youth participants were under the Threat to Family subscale (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Specifically, they were concerned at least sometimes about the implications of the US immigration policy for the family (178 [44.8%]), family separation because of deportation (177 [44.6%]), and being reported to the immigration officials (164 [41.3%]). Female adolescents had higher PIPES scores compared with male adolescents (29.5% vs 11.1% were within the high PIPES score range). Youth participants whose mothers more recently immigrated to the United States (≤5 years at delivery) had somewhat higher PIPES scores compared with other participants (48 [24.5%] vs 34 [16.9%] were within the high PIPES score range; P = .06) (Table 1).

Although few adolescents had hypertension, 56 (16.0%) were prehypertensive (Table 2). More than half were overweight (69 [17.6%]) or obese (141 [36.1%]), with mean BMIs of approximately 27 (75th percentile). The self-reported mean (SD) anxiety T score was 50.8 (11.1); 83 of 386 adolescents (21.5%) were within either the at-risk or clinically significant range. The self-reported mean (SD) depression T score was 48.1 (10.0); 57 of 386 adolescents (14.8%) were within either the at-risk or clinically significant range.

Table 2. Summary of Health Outcomes of US-Born Youth Participants.

| Health Outcome | Overall | Male | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total No. | No. (%) With Outcome | Total No. | No. (%) With Outcome | Total No. | No. (%) With Outcome | |

| Blood Pressure | ||||||

| SBP, mean (SD), mm Hga | 351 | 111.1 (11.7) | 172 | 115.0 (11.0) | 179 | 107.2 (11.0) |

| No hypertension | 274 (78.1) | 118 (68.6) | 156 (87.2) | |||

| Prehypertension | 56 (16.0) | 44 (25.6) | 12 (6.7) | |||

| Stage 1 hypertension | 19 (5.4) | 10 (5.8) | 9 (5.0) | |||

| Stage 2 hypertension | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | |||

| DBP, mean (SD), mm Hg | 351 | 62.1 (7.1) | 172 | 62.9 (6.8) | 179 | 61.4 (7.4) |

| MAP, mean (SD), mm Hg | 351 | 81.0 (7.9) | 172 | 82.9 (7.3) | 179 | 79.2 (8.0) |

| Body Composition | ||||||

| BMI, mean (SD)b | 391 | 27.1 (7.4) | 187 | 26.9 (6.9) | 204 | 27.3 (7.8) |

| BMI z score, mean (SD) | 1.03 (1.17) | 1.09 (1.21) | 0.98 (1.13) | |||

| BMI percentile, mean (SD) | 75.5 (27.4) | 75.5 (28.3) | 75.4 (26.5) | |||

| Underweight | 6 (1.5) | 3 (1.6) | 3 (1.5) | |||

| Normal or healthy weight | 175 (44.8) | 81 (43.3) | 94 (46.1) | |||

| Overweight | 69 (17.6) | 29 (15.5) | 40 (19.6) | |||

| Obese | 141 (36.1) | 74 (39.6) | 67 (32.8) | |||

| Anxiety | ||||||

| Youth self-report, mean (SD), T scorec | 386 | 50.8 (11.1) | 184 | 49.8 (10.4) | 202 | 51.8 (11.7) |

| Clinically significant | 22 (5.7) | 4 (2.2) | 18 (8.9) | |||

| At risk | 61 (15.8) | 29 (15.8) | 32 (15.8) | |||

| Average | 229 (59.3) | 111 (60.3) | 118 (58.4) | |||

| Low | 69 (17.9) | 40 (21.7) | 29 (14.4) | |||

| Very low | 5 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 5 (2.5) | |||

| Parent report, mean (SD), T scorec | 391 | 49.9 (9.8) | 187 | 50.4 (8.7) | 204 | 49.4 (10.8) |

| Clinically significant | 15 (3.8) | 6 (3.2) | 9 (4.4) | |||

| At risk | 48 (12.3) | 17 (9.1) | 31 (15.2) | |||

| Average | 266 (68) | 136 (72.7) | 130 (63.7) | |||

| Low | 56 (14.3) | 28 (15.0) | 28 (13.7) | |||

| Very low | 6 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 6 (2.9) | |||

| Depression | ||||||

| Youth self-report, mean (SD), T scorec | 386 | 48.1 (10.0) | 184 | 46.9 (8.4) | 202 | 49.2 (11.3) |

| Clinically significant | 22 (5.7) | 4 (2.2) | 18 (8.9) | |||

| At risk | 35 (9.1) | 17 (9.2) | 18 (8.9) | |||

| Average | 210 (54.4) | 108 (58.7) | 102 (50.5) | |||

| Low | 119 (30.8) | 55 (29.9) | 64 (31.7) | |||

| Parent report, mean (SD), T scorec | 391 | 51.1 (10.6) | 187 | 50.9 (8.6) | 204 | 51.2 (12.1) |

| Clinically significant | 24 (6.1) | 9 (4.8) | 15 (7.4) | |||

| At risk | 37 (9.5) | 13 (7.0) | 24 (11.8) | |||

| Average | 279 (71.4) | 145 (77.5) | 134 (65.7) | |||

| Low | 51 (13.0) | 20 (10.7) | 31 (15.2) | |||

| Sleep Quality | ||||||

| PSQI score, mean (SD)d | 386 | 3.8 (2.4) | 183 | 3.3 (2.3) | 203 | 4.2 (2.5) |

| Poor sleep quality | 45 (11.7) | 45 (24.6) | 76 (37.4) | |||

| Subjective Health | ||||||

| Parent-rated health, mean (SD), 1-5e | 385 | 2.29 (0.97) | 183 | 2.27 (1.01) | 202 | 2.30 (0.93) |

| Excellent | 95 (24.7) | 50 (27.3) | 45 (22.3) | |||

| Very good | 127 (33.0) | 56 (30.6) | 71 (35.1) | |||

| Good | 122 (31.7) | 56 (30.6) | 66 (32.7) | |||

| Fair | 39 (10.1) | 19 (10.4) | 20 (9.9) | |||

| Poor | 2 (0.5) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) | |||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Systolic blood pressure was categorized by percentile for age, sex, and height as no hypertension (<90th percentile), prehypertension (90th-95th percentile), stage 1 hypertension (95th-99th percentile), or stage 2 hypertension (>99th percentile).

Body mass index was categorized as underweight (<5th percentile), normal or healthy weight (5th-85th percentile), overweight (85th-95th percentile), or obese (≥95th percentile).

The BASC-2 T score was categorized by sex-specific standards as clinically significant (≥70), at risk (60-70), average (40-60), low (30-40), or very low (≤30).

PSQI scores ranged from 0 to 21, with lower scores indicating better sleep. Poor sleep quality was defined as a score of 5 or higher.

Parent report of child's general health is on a scale of 1 (excellent) to 5 (poor).

Sixty-five adolescents (16.3%) reported fairly bad or very bad sleep quality, with 85 (21.3%) taking a long time to fall asleep and 43 (10.8%) experiencing daytime dysfunction because of sleepiness at least once a week (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Poor sleep quality was associated with higher self-reported anxiety (Pearson correlation = 0.36; P < .001) and depression (Pearson correlation = 0.35; P < .001) levels but with lower SBP (Pearson correlation = –0.15; P = .006) and DBP (Pearson correlation = –0.18; P < .001). Self-reported anxiety and depression were not associated with BP (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Overall, 41 mothers (10.6%) rated their child’s health as fair or poor.

Youth participants with high total PIPES scores compared with those with low or moderate PIPES scores had higher self-reported mean anxiety T scores (difference, 5.43; 95% CI, 2.64-8.23), higher maternally reported anxiety T scores (difference, 2.98; 95% CI, 0.53-5.44), and worse PSQI scores (difference, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.36-1.59) (Table 3). Youth participants with high total PIPES scores were statistically significantly more likely to report anxiety symptoms in the clinically significant or at-risk range (incidence rate ratio, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.00-2.63) and poor sleep quality (incidence rate ratio, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.03-2.33) (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Table 3. Adjusted Differences in Health Outcomes of US-Born Youth Participants With Low or Moderate or With High Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale (PIPES) Scorea.

| Health Outcome | Total PIPES Score | PIPES Subscale Score: Threat to Family Subscale | PIPES Subscale Score: Children’s Vulnerability Subscale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | Difference, β (95% CI) | Mean (SE) | Difference, β (95% CI) | Mean (SE) | Difference, β (95% CI) | ||||

| Low or Moderateb | Highc | Low or Moderated | Highe | Low or Moderatef | Highg | ||||

| Blood pressure | |||||||||

| SBP, mm Hg | 111.4 (0.7) | 109.7 (1.3) | −1.68 (−4.65 to 1.29) | 111.1 (0.8) | 111.0 (1.0) | −0.14 (−2.65 to 2.37) | 111.5 (0.7) | 109.0 (1.4) | −2.53 (−5.65 to 0.59) |

| DBP, mm Hg | 62.4 (0.4) | 60.9 (0.9) | −1.55 (−3.43 to 0.34) | 62.4 (0.5) | 61.6 (0.6) | −0.77 (−2.36 to 0.82) | 62.4 (0.4) | 60.6 (0.9) | −1.85 (−3.83 to 0.13) |

| MAP, mm Hg | 81.4 (0.5) | 79.7 (0.9) | −1.73 (−3.77 to 0.31) | 81.2 (0.5) | 80.7 (0.7) | −0.51 (−2.23 to 1.22) | 81.4 (0.5) | 79.2 (1.0) | −2.24 (−4.38 to −0.10) |

| Body composition | |||||||||

| BMI | 27.2 (0.4) | 27.1 (0.8) | −0.04 (−1.91 to 1.84) | 27.1 (0.5) | 27.3 (0.6) | 0.20 (−1.38 to 1.78) | 27.2 (0.4) | 27.0 (0.9) | −0.18 (−2.16 to 1.80) |

| Anxiety | |||||||||

| Youth self-report, T score | 49.7 (0.6) | 55.2 (1.3) | 5.43 (2.64 to 8.23) | 50.0 (0.7) | 52.4 (1.0) | 2.38 (−0.01 to 4.77) | 50.0 (0.6) | 54.8 (1.4) | 4.76 (1.80 to 7.71) |

| Parent report, T score | 49.3 (0.6) | 52.2 (1.1) | 2.98 (0.53 to 5.44) | 49.5 (0.6) | 50.5 (0.8) | 1.03 (−1.05 to 3.11) | 49.4 (0.5) | 52.0 (1.2) | 2.52 (−0.07 to 5.12) |

| Depression | |||||||||

| Youth self-report, T score | 47.7 (0.6) | 49.8 (1.2) | 2.14 (−0.41 to 4.69) | 47.8 (0.7) | 48.6 (0.9) | 0.74 (−1.42 to 2.89) | 47.7 (0.6) | 49.8 (1.2) | 2.10 (−0.58 to 4.79) |

| Parent report, T score | 50.8 (0.6) | 52.3 (1.2) | 1.50 (−1.17 to 4.16) | 50.9 (0.7) | 51.5 (0.9) | 0.60 (−1.64 to 2.84) | 51.0 (0.6) | 51.5 (1.3) | 0.55 (−2.26 to 3.35) |

| Sleep quality | |||||||||

| PSQI score | 3.6 (0.1) | 4.6 (0.3) | 0.98 (0.36 to 1.59) | 3.6 (0.2) | 4.2 (0.2) | 0.59 (0.07 to 1.11) | 3.6 (0.1) | 4.7 (0.3) | 1.13 (0.47 to 1.78) |

| Subjective health | |||||||||

| Parent-rated health, 1-5h | 2.3 (0.1) | 2.2 (0.1) | −0.16 (−0.40 to 0.08) | 2.3 (0.1) | 2.3 (0.1) | −0.06 (−0.27 to 0.14) | 2.3 (0.1) | 2.2 (0.1) | −0.12 (−0.38 to 0.14) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Estimates from generalized linear models, with the gaussian distribution and identity link providing the mean change in outcome value for an increase from low or moderate PIPES score to high PIPES score category. Adjusted for maternal educational level, marital status, depression risk, length of time living in the United States at delivery; household income; and youth sex.

Total score of 8 to 23 corresponds to a mean of less than sometimes responses for all 8 questions. Data are within-group means and SEs estimated from regression models.

Total score of 24 to 40 corresponds to a mean of more than sometimes responses for all 8 questions.

Threat to Family subscale score of 3 to 8 corresponds to a mean of less than sometimes responses for all 3 questions.

Threat to Family subscale score of 9 to 15 corresponds to a mean of more than sometimes responses for all 3 questions.

Children's Vulnerability subscale score of 5 to 14 corresponds to a mean of less than sometimes responses for all 5 questions.

Children's Vulnerability subscale score of 15 to 25 corresponds to a mean of more than sometimes responses for all 5 questions.

Parent report of child's general health is on a scale of 1 (excellent) to 5 (poor).

Results were stronger under the Children’s Vulnerability subscale than the Threat to Family subscale for both continuous (Table 3) and categorical outcomes (eTable 4 in the Supplement). Compared with youth participants with low or moderate Children’s Vulnerability scores, those with high scores had lower MAP (–2.24; 95% CI, –4.38 to –0.10) and somewhat lower DBP (–1.85; 95% CI, –3.83 to 0.13). PIPES scores were not associated with BMI, depression, or overall health when examined as continuous or categorical outcomes.

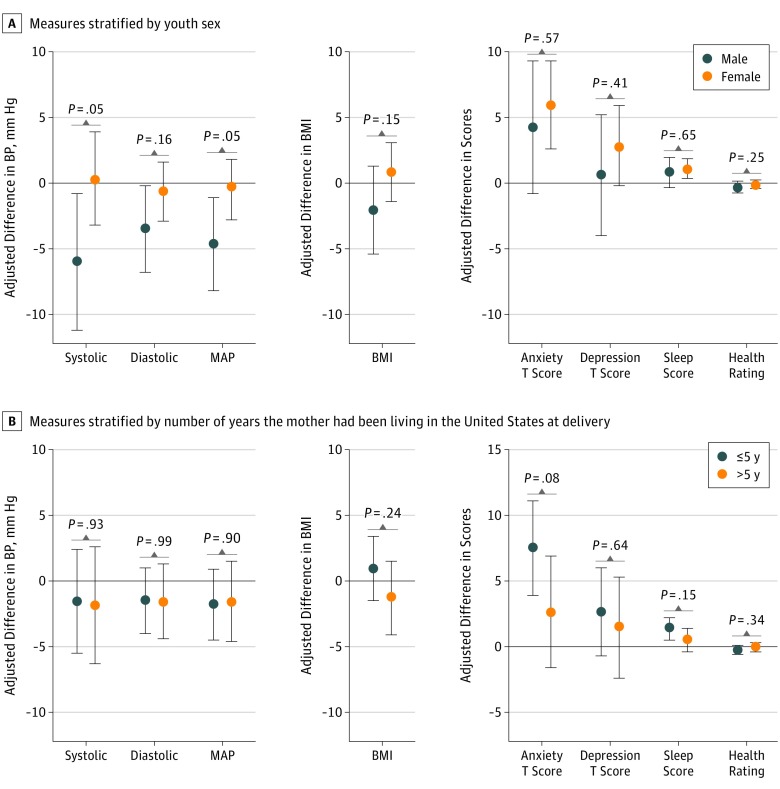

We observed a statistically significant sex interaction: among males but not among females, a higher PIPES score was associated with decreased SBP (–6.00; 95% CI, –11.19 to –0.81; likelihood ratio P = .05), DBP (–3.47; 95% CI, –6.78 to –0.17; likelihood ratio P = .16), and MAP (–4.68; 95% CI, –8.25 to –1.11; likelihood ratio P = .05) (Figure, A). We also observed statistically significant interaction by the length of time the mother had lived in the country; higher PIPES score was associated with increased PSQI score (1.36; 95% CI, 0.55-2.18; likelihood ratio P = .15) and self-reported anxiety T score (7.49; 95% CI, 3.86-11.13; likelihood ratio P = .08) only among youth participants whose mothers had resided in the United States for 5 years or less at delivery (ie, more likely to be undocumented) (Figure, B). No statistically significant effect modification by sex or by the length of time the mother had lived in the country was observed for other measures.

Figure. Comparison of Mental and Physical Health Measures Between US-Born Children With Low or Moderate PIPES (Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale) Score and Those With High PIPES Score .

A statistically significant sex interaction was observed: among males but not among females, a higher PIPES score was associated with lower systolic blood pressure (BP), diastolic BP, and mean arterial pressure (MAP). A statistically significant interaction by the length of time the mother had lived in the country was also observed; higher PIPES score was associated with worse sleep score and anxiety T score only among youth participants whose mothers had resided in the United States for 5 years or less at delivery. BMI indicates body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared). P values are from likelihood ratio tests for interaction.

With regard to changing health outcomes between the aged-14-years and the aged-16-years visits (Table 4; eFigure 2 in the Supplement), youth participants with high PIPES scores at 16 years of age reported an increase in anxiety level that statistically significantly exceeded that experienced by those with low or moderate PIPES scores (difference in differences, 2.91; 95% CI, 0.20-5.61). The change in depression level, although higher, was not statistically significant (difference in differences, 2.63; 95% CI, –0.28 to 5.54). Neither association differed by sex (likelihood ratio P = .37 and P = .97, respectively). Maternally reported youth symptoms did not increase substantially (difference in differences: anxiety, 0.75 [95% CI, –1.40 to 2.90]; depression, 1.29 [95% CI, –0.93 to 3.51]). We found no overall change in BP associated with PIPES scores between visits (difference in differences: SBP, –2.19 [95% CI, –4.88 to 0.50]; DBP, –1.66 [95% CI, –3.84 to 0.52]; and MAP, –1.20 [95% CI, –3.34 to 0.94]). Adolescents with high PIPES scores whose mothers had resided in the United States for 5 years or less at delivery showed less increase in SBP (likelihood ratio P = .10), DBP (likelihood ratio P = .11), and MAP (likelihood ratio P = .13) compared with their peers (Table 4).

Table 4. Summary of Health Outcomes Changes Between Visits by US-Born Youth Participantsa.

| Health Outcome | Within-Group Change From Aged-14-y to Aged-16-y Visits, Mean (SE) | Between-Group Difference in Differences | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | P Value for Interaction for Male and Female Comparisond | β (95% CI) | P Value for Interactiond | ||||||

| Low or Moderate PIPES Scoreb | High PIPES Scorec | All Participants | Male | Female | Mother Lived ≤5 y in United States at Delivery | Mother Lived >5 y in United States at Delivery | |||

| Blood pressure | |||||||||

| SBP, mm Hg | 2.88 (0.6) | 0.70 (1.2) | −2.19 (−4.88 to 0.50) | −2.94 (−7.75 to 1.86) | −1.08 (−4.43 to 2.28) | .25 | −4.16 (−7.76 to −0.56) | −0.16 (−4.17 to 3.84) | .10 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 4.42 (0.5) | 2.76 (1.0) | −1.66 (−3.84 to 0.52) | −1.87 (−5.42 to 1.68) | −1.44 (−4.18 to 1.30) | .30 | −3.11 (−6.13 to −0.09) | 0.06 (−2.93 to 3.05) | .11 |

| MAP, mm Hg | 4.96 (5.0) | 3.76 (1.0) | −1.20 (−3.34 to 0.94) | −2.12 (−6.35 to 2.12) | −0.38 (−2.94 to 2.18) | .27 | −2.88 (−5.66 to −0.09) | 0.61 (−2.66 to 3.87) | .13 |

| Body composition | |||||||||

| BMI | 1.77 (0.2) | 2.05 (0.5) | 0.28 (−0.73 to 1.30) | 0.27 (−0.69 to 1.22) | 0.38 (−0.95 to 1.71) | .07 | 0.58 (−0.93 to 2.09) | −0.10 (−1.26 to 1.06) | .33 |

| Anxiety | |||||||||

| Youth self-report, T score | 1.54 (0.6) | 4.45 (1.2) | 2.91 (0.20 to 5.61) | 4.21 (−0.66 to 9.07) | 3.47 (0.08 to 6.85) | .37 | 4.47 (1.20 to 7.74) | 0.94 (−3.67 to 5.55) | .53 |

| Parent report, T score | −0.04 (0.5) | 0.71 (0.7) | 0.75 (−1.40 to 2.90) | −0.48 (−4.74 to 3.77) | 1.41 (−1.16 to 3.98) | .21 | 1.61 (−1.19 to 4.41) | −0.35 (−3.72 to 3.02) | .66 |

| Depression | |||||||||

| Youth self-report, T score | −0.09 (0.6) | 2.54 (2.5) | 2.63 (−0.28 to 5.54) | 1.25 (−2.49 to 5.00) | 3.50 (−0.34 to 7.35) | .97 | 3.87 (0.73 to 7.01) | 1.07 (−4.39 to 6.52) | .49 |

| Parent report, T score | 1.29 (0.5) | 2.58 (1.0) | 1.29 (−0.93 to 3.51) | −1.33 (−4.84 to 2.19) | 2.58 (−0.28 to 5.44) | .71 | 1.98 (−1.19 to 5.14) | 0.69 (−2.24 to 3.62) | .32 |

| Subjective health | |||||||||

| Parent-rated health, 1-5e | 0.07 (0.1) | 0.03 (0.1) | −0.04 (−0.31 to 0.24) | −2.94 (−7.75 to 1.86) | −1.08 (−4.43 to 2.28) | .25 | −0.14 (−0.51 to 0.22) | 0.09 (−0.31 to 0.49) | .77 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; PIPES, Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Estimates are within-group mean differences and between-group difference-in-differences in continuous value from aged-14-years to aged-16-years visits from generalized estimating equations using the gaussian distribution, identity link, and exchangeable correlation matrix with robust SEs. Models include an interaction term between PIPES category and period and are adjusted for maternal educational level, marital status, depression risk, and length of time living in the United States at delivery; household income; and youth sex.

Total score of 8 to 23 corresponds to a mean of less than sometimes responses for all 8 questions. Data are within-group means and SEs estimated from regression models.

Total score of 24 to 40 corresponds to a mean of more than sometimes responses for all 8 questions.

P value for interaction cross-product terms.

Change in parent report of child's general health is on a scale of 1 (excellent) to 5 (poor) from 14 to 16 years of age.

Discussion

We hypothesized that the vulnerability perceived by adolescents from immigrant families in the face of the current restrictive anti-immigrant policy and rhetoric in the United States has an adverse association with their physical and mental health. The adolescents in this study lived in Salinas Valley, in which Latino people constitute approximately 75% of the population41 and the proportion of undocumented residents likely exceeds 29%.42 The city of Salinas is promoted as a welcoming city nestled within the sanctuary state of California.43 Nevertheless, nearly half of the adolescent study participants reported worrying at least sometimes about the consequences of US immigration policy for their family and themselves, concerns that are aligned with recent data from US-born Latino adults.14

Study results indicate that adolescents’ degree of worry in the first year after the 2016 presidential election was associated cross-sectionally with higher anxiety and poor sleep quality as well as lower MAP and SBP for male participants; these findings possibly reflect a physiologic desensitization in males in response to chronic stress. Comparing a youth’s well-being before and after the 2016 election, we observed that self-reported anxiety symptoms increased markedly among individuals who reported more worry about immigration policy. The smaller changes in BP associated with high levels of anxiety were most pronounced in youth participants whose mothers had lived in the United States for 5 years or less at delivery, the proxy for presumed undocumented status. Thus, this study provides, to our knowledge, the first long-term evidence of the association between the rapidly changing immigration policy environment and alterations in certain aspects of the health trajectory of US citizen adolescents from immigrant families.

These results support the conclusions of previous research that found US-born Mexican American children may experience collateral health damage29,30,31,44,45,46 from immigration policy that targets their families. In a 2008 study of children separated from parents after raids by the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, two-thirds were reported to have experienced changes in sleep pattern after the raids.44 Sleep quality is key to academic achievement and to overall health and well-being.47,48 This research and several other studies46,49 have reported adverse associations between a punitive immigration policy and children’s anxiety and depression symptoms. Latino children with undocumented parents potentially facing policy-related burdens may be at greater risk of both internalizing and externalizing behaviors compared with peers with documented or US citizen parents.29 Mental health stress in adolescence may be associated with short-term disturbance in school performance, increased risk for substance abuse, and long-term employment and health consequences.50,51,52 Conversely, an inclusive policy that prevents deportation of parents has demonstrated protective properties, easing the minds of US citizen children.30

In a previous report,53 mothers participating in the CHAMACOS study who had a lot of worry about deportation in 2012 were more likely to be obese and have higher pulse pressure, but they were not more likely to be hypertensive or have elevated DBP or MAP. In the present analysis, no association was found between PIPES scores and BMI of youth participants. These findings suggest that, although immigrant adults may experience chronic concern about deportation, it is possible that their US citizen children were relatively buffered from this fear in 2012 until recently. In this case, the follow-up period of only 1 year after the election, with many youth participants who were weighed soon afterward, may have been too short to observe a change in BMI. Likewise, it may have been too short a period to move the needle on mothers’ overall assessments of their children’s health.

Given the previous findings of higher pulse pressure in mothers who worried more about deportation, the finding in the present study of lower MAP among the most worried male (but not female) participants was somewhat unexpected. However, this decreased MAP may reflect sex-specific physiologic differences in response to adversity; male individuals tend to adapt by calibrating downward to achieve homeostasis, whereas female individuals tend to calibrate upward.54 For the most worried males in this sample, increased fear of family deportation and perception of vulnerability could be associated with a reduction in physiologic responsivity; lowered BP may reflect a move to a lower resting state.

Strengths and Limitations

The present study has both strengths and limitations. To our knowledge, this study is the first (or perhaps only) sample of adolescents from immigrant families to undergo physical and mental health outcomes measurement at time points almost immediately before and after a historical event that has fear-evoking implications for their families. The sample answered the call for long-standing research into the implications of this event for the well-being of children from immigrant families.16,31,55 Other important strengths include repeat assessments of multiple health end points, including both maternal and youth participants’ reporting on adolescent mental health using a widely used tool validated in both English and Spanish.37 The use of PIPES34 is another strength, allowing us to capture a more nuanced picture of youth participants’ concerns compared with previous studies, which largely relied on parental immigration status as the independent variable.

Nonetheless, we recognize that not knowing the immigration status of parents was a limitation of this study. We also did not have measures of self-reported immigration stress or sleep quality at age 14 years. Because these participants likely lived in an immigrant-friendly community, which may have served as a buffer, our results may have underestimated the implications for youth in communities that are less receptive to immigration.56

This study provides epidemiologic support for the American Academy of Pediatrics 2017 statement on protecting immigrant children, which stated that “Far too many children in this country already live in constant fear that their parents will be … deported… When children are scared, it can impact their health and development.”57 The findings underscore the call of adolescent health experts for “action… (to) alleviate the detrimental effects of this status on millions of children and youth,”55 including provision of legal and mental health services within trusted immigrant-supportive institutions, support for DACA, and, ultimately, enactment of comprehensive federal immigration reform. Future research should track these potentially lasting implications as adolescents exposed to anti-immigrant policy and rhetoric become young adults.

Conclusions

These study results suggest that the current immigration policy environment has negative implications for the mental health of US citizen children of immigrants. Anxiety among this population statistically significantly increased after the 2016 presidential election.

eTable 1. Responses on the Threat to Family and Children’s Vulnerability Subscale of the Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale (PIPES) Among 16-Year-Old US-born Children of Immigrants, CHAMACOS Study (N = 397)

eTable 2. Responses to the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index for 16-Year-Old Youth With Low/Moderate vs High Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale (PIPES) Scores, CHAMACOS Study

eTable 3. Pearson Correlations Between Health Outcomes for 16-Year-Old Youth, CHAMACOS Study

eTable 4. Associations of Binary Health Outcomes With Categorical Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale (PIPES) Among 16-Year-Old US-born Children of Immigrants, CHAMACOS Study

eFigure 1. DAGs for Child’s Perceived Immigration Policy Effects and (a) Blood Pressure, (b) BMI, and (c) Mental Health (DAGitty v3.0)

eFigure 2. Adjusted Predictive Margins at 14 and 16 Years by Categorical Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale (PIPES) Among (a) All 16-Year-Old US-born Children of Immigrants and (b) Stratified by Maternal Time in US at Delivery, CHAMACOS Study

References

- 1.Annie E. Casey Foundation. 2017 Race for results: building a path to opportunity for all children. https://www.aecf.org /resources/2017-race-for-results/. Published October 24, 2017. Accessed October 16, 2018.

- 2.Passel JS, Cohn D As Mexican share declined, U.S. unauthorized immigrant population fell in 2015 below recession level. Pew Research Center website. 2017. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/04/25/as-mexican-share-declined-u-s-unauthorized-immigrant-population-fell-in-2015-below-recession-level/. Published April 25, 2017. Accessed October 16, 2018.

- 3.Departments of Commerce, Justice, and State, the Judiciary, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act. 105th Congress. Public L No. 105-119—November 26, 1997 (1998). https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-105publ119/pdf/PLAW-105publ119.pdf. Accessed October 16, 2018.

- 4.Swan J, Kight SW Exclusive: Trump targeting birthright citizenship with executive order. Axios on HBO website. 2018: https://www.axios.com/trump-birthright-citizenship-executive-order-0cf4285a-16c6-48f2-a933-bd71fd72ea82.html. Published October 30, 2018. Accessed February 12, 2019.

- 5.Davis JH. President wants to use executive order to end birthright citizenship. New York Times October 30, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/30/us/politics/trump-birthright-citizenship.html. Accessed on February 12, 2019.

- 6.President Donald J. Trump’s address to the nation on the crisis at the border. WhiteHouse.gov website. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/president-donald-j-trumps-address-nation-crisis-border/. Published January 8, 2019. Accessed February 12, 2019.

- 7.Donald Trump announces a presidential bid. Washington Post June 16, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/post-politics/wp/2015/06/16/full-text-donald-trump-announces-a-presidential-bid/. Accessed January 24, 2019.

- 8.Nixon R, Qui L Trump's evolving words on the wall. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/18/us/politics/trump-border-wall-immigration.html? module=inline. Published January 18, 2018. Accessed January 24, 2019.

- 9.Remarks by President Trump on border security. WhiteHouse.gov. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-border-security/. Published January 3, 2019. Accessed February 12, 2019.

- 10.Shear MD, Hirschfeld Davis J Trump moves to end DACA and calls on Congress to act. New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/05/us/politics/trump-daca-dreamers-immigration.html. Published September 5, 2017. Accessed February 12, 2019.

- 11.Statement from President Donald J. Trump. WhiteHouse.gov. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/statement-president-donald-j-trump-7/. Published September 5, 2017. Accessed January 24, 2019.

- 12.Horwitz S, Sacchetti M Sessions vows to prosecute all illegal border crossers and separate children from their parents. Washington Post May 7, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost. com/world/national-security/sessions-says-justice-dept-will-prosecute-every-person-who-crosses-border-unlawfully/2018/05/07/e1312b7e-5216-11e8-9c91-7dab596e8252_story.html. Accessed February 12, 2019.

- 13.Radnofsky L, Andrews N, Fassihi F Trump defends family-separation policy. Wall Street Journal June 18, 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/trump-administration-defends-family-separation-policy-1529341079. Accessed February 12, 2019.

- 14.Pew Research Center Half of Hispanics say they worry about deportation. Hispanic Trends. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2018/10/25/views-of-immigration-policy/ph_2018-10-25_national-survey-of-latinos-2018_4-01/. Published October 24, 2018. Accessed November 5, 2018.

- 15.Cavazos-Rehg PA, Zayas LH, Spitznagel EL. Legal status, emotional well-being and subjective health status of Latino immigrants. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(10):1126-1131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martínez O, Wu E, Sandfort T, et al. Evaluating the impact of immigration policies on health status among undocumented immigrants: a systematic review [published correction appears in J Immigr Minor Health. 2016;18(1):288]. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(3):947-970. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9968-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhodes SD, Mann L, Simán FM, et al. The impact of local immigration enforcement policies on the health of immigrant Hispanics/Latinos in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):329-337. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcini LM, Peña JM, Gutierrez AP, et al. “One scar too many”: the associations between traumatic events and psychological distress among undocumented Mexican immigrants. J Trauma Stress. 2017;30(5):453-462. doi: 10.1002/jts.22216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siemons R, Raymond-Flesch M, Auerswald CL, Brindis CD. Erratum to: coming of age on the margins: mental health and wellbeing among Latino immigrant young adults eligible for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). J Immigr Minor Health. 2017;19(4):1000. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0395-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patler C, Laster Pirtle W. From undocumented to lawfully present: do changes to legal status impact psychological wellbeing among Latino immigrant young adults? Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:39-48. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshikawa H. Immigrants Raising Citizens: Undocumented Parents and Their Children. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardy LJ, Getrich CM, Quezada JC, Guay A, Michalowski RJ, Henley E. A call for further research on the impact of state-level immigration policies on public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1250-1254. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henderson SW, Baily CDR. Parental deportation, families, and mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(5):451-453. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salas LM, Ayón C, Gurrola M. Estamos traumados: the effect of anti-immigrant sentiment and policies on the mental health of Mexican immigrant families. J Community Psychol. 2013;41(8):1005-1020. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21589 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brabeck KM, Lykes MB, Hunter C. The psychosocial impact of detention and deportation on US migrant children and families. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84(5):496-505. doi: 10.1037/ort0000011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dreby J. US immigration policy and family separation: the consequences for children’s well-being. Soc Sci Med. 2015;132:245-251. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ayón C. “Vivimos en jaula de oro”: the impact of state-level legislation on immigrant Latino families. J Immigr Refug Stud. 2017;16(4):351-371. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2017.1306151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martínez AD, Ruelas L, Granger DA. Household fear of deportation in Mexican-origin families: relation to body mass index percentiles and salivary uric acid. Am J Hum Biol. 2017;29(6). doi: 10.1002/ajhb.23044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landale NS, Hardie JH, Oropesa RS, Hillemeier MM. Behavioral functioning among Mexican-origin children: does parental legal status matter? J Health Soc Behav. 2015;56(1):2-18. doi: 10.1177/0022146514567896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hainmueller J, Lawrence D, Martén L, et al. Protecting unauthorized immigrant mothers improves their children’s mental health. Science. 2017;357(6355):1041-1044. doi: 10.1126/science.aan5893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vargas ED, Ybarra VDUS U.S. citizen children of undocumented parents: the link between state immigration policy and the health of Latino children. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017;19(4):913-920. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0463-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eskenazi B, Harley K, Bradman A, et al. Association of in utero organophosphate pesticide exposure and fetal growth and length of gestation in an agricultural population. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(10):1116-1124. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaspar FW, Harley KG, Kogut K, et al. Prenatal DDT and DDE exposure and child IQ in the CHAMACOS cohort. Environ Int. 2015;85:206-212. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ayón C. Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale: development and validation of a scale on the impact of state-level immigration policies on Latino immigrant families. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2016;39(1):19-33. doi: 10.1177/0739986316681102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.A pocket guide to blood pressure measurement in children: from the national high blood pressure education program working group on blood pressure in children and adolescents. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/bp_child_pocket.pdf. Published May 2007. Accessed October 18, 2018.

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention BMI for children and teens: defining childhood obesity. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/defining.html. Updated 2016. Accessed October 29, 2018.

- 37.Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. BASC-2: Behavioral Assessment System for Children. Second Edition Manual Circle Pines, MN: AGS Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193-213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.US Census Bureau Poverty thresholds: poverty thresholds by size of family and number of children; 2013-2016. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-poverty-thresholds.html. Accessed October 18, 2018.

- 40.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. App Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.US Census Bureau. QuickFacts Salinas City, California. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/salinascitycalifornia,US/PST045217. Accessed October 18, 2018.

- 42.US Census Bureau Nativity and citizenship status in the United States. Universe: total population in the United States 2011-2015 American Community Survey selected population tables. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml ?pid=ACS_15_SPT_B05001&prodType=table. Accessed January 24, 2019.

- 43.Rubin S. Salinas becomes a “welcoming city,” an approximation of sanctuary city. Monterey County Weekly. June 21, 2017. http://www.montereycountyweekly.com/blogs/news_blog/salinas-becomes-a-welcoming-city-an-approximation-of-sanctuary-city/article_ab4933de-56be-11e7-8210-bbbe09ed7f91.html. Accessed October 18, 2018.

- 44.Chaudry A, Capps R, Pedroza JM, Castañeda RM, Santos R, Scott MM Facing our future: children in the aftermath of immigration enforcement. The Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/28331/412020-Facing-Our-Future.PDF. Published February 2010. Accessed February 12, 2019.

- 45.Perreira KM, Pedroza JM. Policies of exclusion: implications for the health of immigrants and their children. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:147-166. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Allen B, Cisneros EM, Tellez A. The children left behind: the impact of parental deportation on mental health. J Child Fam Stud. 2015;24(2):386-392. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9848-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen MY, Wang EK, Jeng YJ. Adequate sleep among adolescents is positively associated with health status and health-related behaviors. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dewald JF, Meijer AM, Oort FJ, Kerkhof GA, Bögels SM. The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(3):179-189. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gulbas LE, Zayas LH, Yoon H, Szlyk H, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Natera G. Deportation experiences and depression among U.S. citizen-children with undocumented Mexican parents. Child Care Health Dev. 2016;42(2):220-230. doi: 10.1111/cch.12307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2009;32(3):483-524. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Currie J, Stabile M, Manivong P, Roos LL. Child health and young adult outcomes. J Hum Resour. 2010;45(3):517-548. doi: 10.3368/jhr.45.3.517 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thapar A, Collishaw S, Pine DS, Thapar AK. Depression in adolescence. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1056-1067. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60871-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Torres JM, Deardorff J, Gunier RB, et al. Worry about deportation and cardiovascular disease risk factors among adult women: the Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas study. Ann Behav Med. 2018;52(2):186-193. doi: 10.1093/abm/kax007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Del Giudice M, Ellis BJ, Shirtcliff EA. The adaptive calibration model of stress responsivity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(7):1562-1592. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoshikawa H, Suárez-Orozco C, Gonzales RG. Unauthorized status and youth development in the United States: consensus statement of the Society for Research on Adolescence. J Res Adolesc. 2017;27(1):4-19. doi: 10.1111/jora.12272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vargas ED, Sanchez GR, Juárez M. Fear by association: perceptions of anti-immigrant policy and health outcomes. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2017;42(3):459-483. doi: 10.1215/03616878-3802940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stein F. AAP statement on protecting immigrant children. American Academy of Pediatrics. https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/Pages/AAPStatementonProtectingImmigrantChildren.aspx. Published January 25, 2017. Accessed February 12, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Responses on the Threat to Family and Children’s Vulnerability Subscale of the Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale (PIPES) Among 16-Year-Old US-born Children of Immigrants, CHAMACOS Study (N = 397)

eTable 2. Responses to the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index for 16-Year-Old Youth With Low/Moderate vs High Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale (PIPES) Scores, CHAMACOS Study

eTable 3. Pearson Correlations Between Health Outcomes for 16-Year-Old Youth, CHAMACOS Study

eTable 4. Associations of Binary Health Outcomes With Categorical Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale (PIPES) Among 16-Year-Old US-born Children of Immigrants, CHAMACOS Study

eFigure 1. DAGs for Child’s Perceived Immigration Policy Effects and (a) Blood Pressure, (b) BMI, and (c) Mental Health (DAGitty v3.0)

eFigure 2. Adjusted Predictive Margins at 14 and 16 Years by Categorical Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale (PIPES) Among (a) All 16-Year-Old US-born Children of Immigrants and (b) Stratified by Maternal Time in US at Delivery, CHAMACOS Study