Key Points

Question

Does the provision of a drug disposal bag increase the rate of proper excess opioid disposal among families of children prescribed opioids after outpatient surgery?

Findings

This randomized clinical trial of 202 families found that compared with providing only standard postoperative discharge instructions on opioid use, storage, and disposal, also providing a drug disposal bag significantly increased the rate of proper disposal of excess opioids by approximately 20% among families of children receiving postoperative opioids.

Meaning

Greater availability of drug disposal products may complement prescribing reduction efforts in the fight to end the opioid epidemic.

Abstract

Importance

Although opioids are an important component of pain management for children recovering from surgery, postoperative opioid prescribing has contributed to the current opioid crisis in the United States because these medications are often prescribed in excess and are rarely properly disposed. One potential strategy to combat opioid misuse is to remove excess postoperative opioids from circulation by providing patients with drug disposal products that enable safe disposal of opioids in the home garbage.

Objective

To determine whether the provision of a drug disposal bag increases proper opioid disposal among the families of pediatric patients undergoing ambulatory surgery.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This randomized clinical trial enrolled 202 parents or guardians of children 1 to 17 years of age who underwent otolaryngologic or urologic surgery at the outpatient surgery centers of a tertiary children’s hospital in Columbus, Ohio, from June to December 2018 and who received an opioid prescription prior to discharge.

Interventions

Families randomized to intervention were provided a drug disposal bag containing activated charcoal and instructions for use plus standard postoperative discharge instructions on opioid use, storage, and disposal. Families in standard care arm received standard postoperative discharge instructions only. All participants completed a baseline survey and a follow-up survey 2 to 4 weeks postoperatively.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcome was proper opioid disposal, defined as disposal using a drug disposal bag or a disposal method recommended by the US Food and Drug Administration.

Results

Of 202 parents or guardians enrolled, 181 completed follow-up (92 in intervention arm and 89 in standard care arm). Most patients in both groups were white (75 [73.5%] vs 79 [80.6%]) and male (63 [61.2%] vs 54 [54.6%]), and the median (interquartile range) age was 6 (5-9) years in the intervention arm and 7 (6-10) years in the standard care arm. For intention-to-treat analyses, 92 families receiving a disposal bag and 89 families not receiving a disposal bag were included. Among them, 66 families (71.7%) randomized to receive a disposal bag reported properly disposing of their child’s opioids, whereas 50 parents (56.2%) who did not receive a disposal bag reported proper opioid disposal (difference in proportions, 15.5%; 95% CI, 1.7%-29.3%; P = .03). Among only those families who filled an opioid prescription and had leftover opioids after resolution of their child’s pain, 66 of 77 parents or guardians (85.7%) who had received a disposal bag and 50 of 77 parents or guardians (64.9%) who had received standard care reported properly disposing of their child’s opioids (difference in proportions, 20.8%; 95% CI, 7.6%-34.0%).

Conclusions and Relevance

Results of this study indicated that providing drug disposal bags to families of children receiving postoperative opioids increased the likelihood of excess opioid disposal. Greater availability of disposal products may complement ongoing prescribing reduction efforts aimed at decreasing opioid misuse.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03575377

This randomized clinical trial assesses whether providing a drug disposal bag along with postoperative discharge instructions on opioid use, storage, and disposal affects the rate of proper opioid disposal compared with that for providing only the discharge instructions among families of pediatric patients undergoing ambulatory surgery.

Introduction

Despite recent decreases in opioid prescribing, opioid-related overdose and death rates continue to increase in all age groups.1,2,3 High rates of opioid misuse and nearly 10% of drug overdose deaths in the United States occur among adolescents and young adults aged 15 to 24 years.4,5 Prescriptions from family or friends are the most common source of prescription opioids misused by adolescents, and leftover pills from adolescents’ own prescriptions are the second most common source.6 Young children with opioids in the home are also at risk for opioid overdose through unintentional ingestion.7 In the pediatric population, opioids are most commonly prescribed after surgical and dental procedures.8 However, opioids prescribed for postoperative pain management vary widely,9 are often in excess,10 and are rarely disposed of properly.11 Rates of proper disposal of unused opioids after surgery have been reported to be less than 10% among both adults and children, suggesting that excess opioids remaining in the home after surgery is a widespread but targetable problem.11,12,13

Several previous studies14,15,16,17,18 have targeted the problem of nondisposal of excess opioids by providing patients with educational materials describing methods for proper disposal. However, those studies, all of which focused on adult patients, have not consistently demonstrated an improvement in excess opioid disposal after patient education.14,15,16,17,18 Another potential solution to facilitate disposal is the provision of drug disposal products. These products contain compounds that irreversibly adsorb or oxidize medications, enabling them to be disposed of in the home garbage without the possibility of retrieval.19,20 The primary objective of the present randomized clinical trial was to evaluate whether providing one such product, a drug disposal bag containing activated charcoal, to families of children having outpatient surgery increases proper opioid disposal.

Methods

We performed a randomized clinical trial including families with children having outpatient surgery at the 2 ambulatory surgery centers of our hospital (Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio) from June through December 2018 (trial protocol in Supplement 1). Parents or guardians of children having outpatient urologic or otolaryngologic surgery were enrolled. Parents or guardians were eligible if they were English speaking and their child was 1 to 17 years of age and expected to receive an opioid prescription at discharge. Parents or guardians were excluded if they were unable or unwilling to complete a follow-up survey. If a family had more than 1 child scheduled for surgery on the same day, the family was asked to complete all surveys for the child scheduled to undergo surgery first. The Institutional Review Board at Nationwide Children’s Hospital approved this trial as a minimal risk study and thus waived the need for informed participant consent.

Screening and Enrollment

A member of the research staff (A.E.L.) reviewed operating room schedules and consulted with attending surgeons to identify surgical procedures after which an opioid was likely to be prescribed. All potentially eligible parents or guardians were approached on the days when research assistants were available. Parents or guardians were approached, enrolled, and randomized in the preanesthesia waiting area of the ambulatory surgery unit. Study staff (A.E.L., A.J.C., and H.W.R.) explained that the study aimed to better understand children's pain management needs after surgery and required brief baseline and follow-up surveys and tracking of pain medication use. Study staff did not mention that questions regarding opioid disposal would be included on the follow-up survey. If parents verbally agreed to participate, they were randomized to receive either (1) a drug disposal bag (Deterra, Verde Technologies) in addition to standard opioid-related education by the care team or (2) standard education only. Randomization was performed electronically using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system.21 A 1:1 allocation ratio and randomized block scheme, with blocks of sizes 4 and 6, were used.

Intervention and Control Groups

All families received a 1-page pain journal to record their child’s opioid and nonopioid adjunct pain medication administration. All families also received the standard opioid-related education provided by the care team, which included a handout22 describing proper opioid use, storage, and disposal (with no mention of disposal products) and a video containing the same information.23 In addition, parents or guardians of patients undergoing otolaryngologic procedures were required to sign an “opioid consent form,” acknowledging that they would follow appropriate dosing recommendations, not give opioids if their child appeared sleepy, not give acetaminophen concurrently with acetaminophen-containing opioid medications, dispose of unused opioids safely and responsibly, and contact their child’s surgeon’s office or the on-call physician with any questions. This consent form had been implemented as part of quality improvement efforts several months prior to this trial. If a parent or guardian of a child undergoing otolaryngologic surgery did not sign this form, the child could still undergo the surgical procedure but would not receive an opioid prescription at discharge. Families randomized to the intervention arm additionally received a drug disposal bag and were instructed by a research assistant to use the bag for opioid disposal once their child no longer required opioids for pain control. They were also advised to use the bag to dispose of other leftover or expired medications in their home. The directions on the bag describing its proper use were also reviewed. The drug disposal bag in this study is a small resealable bag containing activated charcoal in a capsule. Once medications are put into the bag and water added, the activated charcoal is released, causing medications to be adsorbed and rendered no longer usable. The bags can be used with pills, patches, and liquids.20,24

Baseline Data Collection

Baseline data were collected directly from parents or guardians as well as from electronic medical records and were entered into REDCap. Parent- or guardian-reported data included educational level, household income level, and acknowledgment of anyone with chronic pain or anyone using prescribed opioids residing in the child’s home. Parents also completed the Brief Health Literacy Screening Tool.25 This was administered because of evidence of lesser overall knowledge about opioid pain medication among adults with low health literacy.26 Demographic and clinical characteristics of the child were extracted from medical records (trial protocol in Supplement 1).

Follow-up Survey

Parents or guardians were contacted by their preferred method of email (with survey link) or telephone call 2 weeks postoperatively, at which time they were asked about their child’s postoperative opioid and nonopioid medication use, opioid storage location, disposal method, and any barriers to disposal (trial protocol in Supplement 1). If the child continued to require opioids at the time of contact, parents or guardians were contacted again 4 weeks postoperatively.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was the rate of proper disposal of unused opioids, defined as the disposal of unused opioids by using a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–recommended method or a drug disposal bag. Drug take-back events, drop-off boxes, flushing down the toilet or sink, mixing with an unpalatable substance before disposal in the garbage, or use of a drug disposal bag were all considered proper disposal methods.27 Secondary outcomes defined a priori included the number of doses of opioid pain medication used, whether any opioids remained unused after the resolution of postoperative pain and how many doses remained unused, opioid storage location, opioid disposal (by any method), and barriers to opioid disposal. Secondary outcomes examined post hoc included caregivers’ ratings of their child’s overall postoperative pain control, whether the opioid prescription was filled, and the number of days opioids were used.

Statistical Analysis

On the basis of the results of a similar trial in an adult surgical population,28 we expected the proportion of families properly disposing of their child’s unused opioids to increase by 20%, from 23% in the control group to 43% in the group receiving the drug disposal bag. To achieve 80% power to detect this effect size, and accounting for a combined 15% of families not receiving an opioid prescription, not filling an opioid prescription, or being lost to follow-up, we aimed to enroll 202 families. Baseline characteristics and outcomes are described using medians and interquartile ranges or frequencies and percentages. Outcomes were compared between groups using χ2 or Fisher exact tests. Planned analyses were performed to assess treatment effect heterogeneity by caregiver health literacy and whether an opioid consent form was signed. Heterogeneity was assessed on additive and on relative scales using linear and log binomial regression models, respectively, and stratified analyses were performed. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide, version 7.15 (SAS Institute Inc). Primary and secondary outcomes are reported for the intention-to-treat population and the primary outcome is also reported for the per protocol population. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

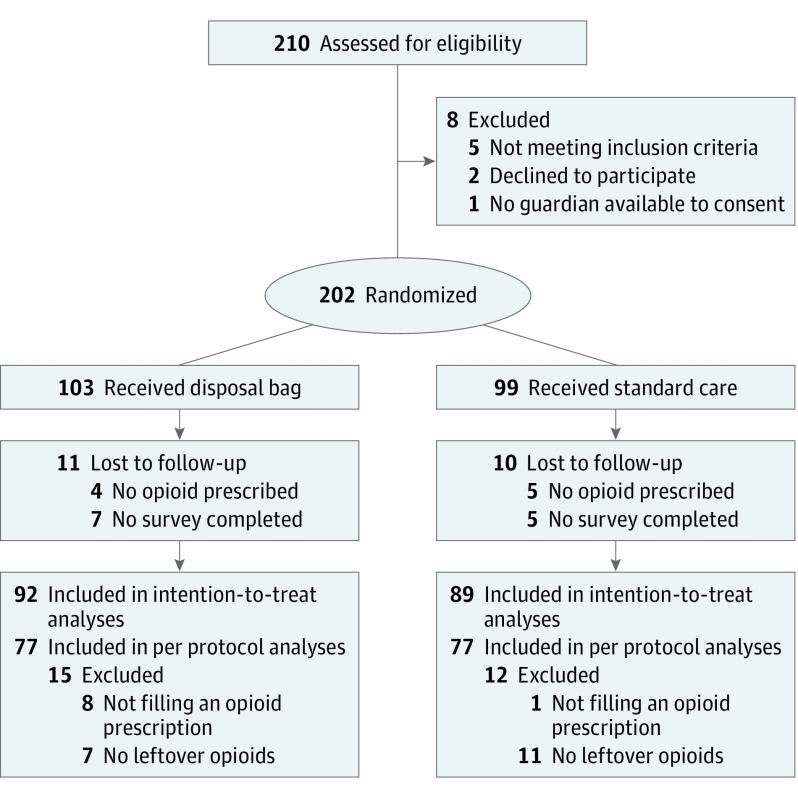

In total, 202 families were enrolled (Figure). Among them, 103 families were randomized to receive a drug disposal bag, and 99 were randomized to receive standard care. The majority of patients in both groups were white individuals (75 [73.5%] vs 79 [80.6%]) and male (63 [61.2%] vs 54 [54.6%]) (Table 1). The median (interquartile range) patient age was 6 (5-9) years in the intervention arm and 7 (6-10) years in the standard care arm. The majority of patients had private insurance (58 [56.3%] vs 52 [52.5%]). The most common procedure performed was tonsillectomy (75 [72.8%] vs 79 [79.8%]). Nearly all children were prescribed liquid opioid medication (96 of 99 [97.0%] vs 89 of 94 [94.7%]), and only short-acting hydrocodone (72 of 99 [72.7%] vs 78 of 94 [83.0%]) and oxycodone (27 of 99 [27.3%] vs 16 of 94 [17.0%]) were prescribed. Most caregivers showed adequate health literacy (94 [91.3%] vs 85 [85.9%]). Notably, 30 of 202 families [14.9%] reported that someone in the household lived with chronic pain, and 9 of 202 families [4.5%] indicated that someone in the home was currently using prescription opioids.

Figure. Enrollment, Randomization, and Participant Flow in the Study.

Table 1. Baseline Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) of Participants | |

|---|---|---|

| Disposal Bag (n = 103) | Standard Care (n = 99) | |

| Patient characteristic | ||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 6 (5-9) | 7 (6-10) |

| Male sex | 63 (61.2) | 54 (54.6) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 75 (73.5) | 79 (80.6) |

| Black | 5 (4.9) | 11 (11.2) |

| Asian | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Hispanic | 4 (3.9) | 0 (0) |

| Biracial/multiracial | 17 (16.7) | 7 (7.1) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Primary payer | ||

| Medicaid | 43 (41.8) | 45 (45.5) |

| Private insurance | 58 (56.3) | 52 (52.5) |

| Other | 2 (1.9) | 2 (2.0) |

| Surgical procedurea | ||

| Tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy | 75 (72.8) | 79 (79.8) |

| Tympanoplasty | 0 (0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Turbinate reduction | 14 (13.6) | 12 (12.1) |

| Inguinal hernia repair | 12 (11.7) | 5 (5.1) |

| Circumcision | 4 (3.9) | 5 (5.1) |

| Circumcision revision | 2 (1.9) | 4 (4.0) |

| Orchiopexy | 10 (9.7) | 3 (3.0) |

| Hydrocele repair | 4 (3.9) | 3 (3.0) |

| Hypospadias repair | 2 (1.9) | 1 (1.0) |

| Orchiectomy | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0) |

| Hidden penis repair | 2 (1.9) | 1 (1.0) |

| Type of opioid prescribed (n = 193) | ||

| Hydrocodone | 72 (72.7) | 78 (83.0) |

| Oxycodone | 27 (27.3) | 16 (17.0) |

| Opioid formulation (n = 193) | ||

| Pills | 3 (3.0) | 5 (5.3) |

| Liquid | 96 (97.0) | 89 (94.7) |

| Caregiver and family characteristic | ||

| Highest educational level of any parent or guardian | ||

| High school or GED | 25 (24.3) | 24 (24.2) |

| Associate’s degree or some college | 37 (35.9) | 43 (43.4) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 22 (21.4) | 20 (20.2) |

| Master’s degree or above | 19 (18.5) | 12 (12.1) |

| Household income (n = 200), $ | ||

| ≤25 000 | 24 (23.5) | 18 (18.3) |

| >25 000-50 000 | 22 (21.6) | 27 (27.6) |

| >50 000-100 000 | 28 (27.5) | 30 (30.6) |

| >100 000 | 28 (27.5) | 23 (23.5) |

| Health literacy | ||

| Limited or marginal | 9 (8.7) | 14 (14.1) |

| Adequate | 94 (91.3) | 85 (85.9) |

| Anyone with chronic pain in household | 18 (17.5) | 12 (12.1) |

| Anyone using prescribed opioids in household | 3 (2.9) | 6 (6.1) |

Abbreviations: GED, General Education Development; IQR, interquartile range.

Some patients had more than 1 procedure.

In total, 193 parents or guardians received an opioid prescription at discharge. Clinicians elected not to prescribe opioids to 7 patients, and the parents of 2 patients, both of whom had received a drug disposal bag, refused an opioid prescription. Among the 193 parents or guardians whose child was prescribed an opioid, 94% completed a follow-up survey. Compared with the standard care, a higher percentage of families who received a drug disposal bag reported properly disposing of their child’s leftover opioids (66 of 92 [71.7%] vs 50 of 89 [56.2%], difference in proportions, 15.5%; 95% CI, 1.7%-29.3%; P = .03) (Table 2). Among only those parents or guardians who filled an opioid prescription and had leftover opioids after the resolution of their child’s pain, 66 of 77 (85.7%) who had received a disposal bag and 50 of 77 (64.9%) who had received standard care properly disposed of their child’s leftover opioids (difference in proportions, 20.8%; 95% CI, 7.6%-34.0%). However, a lower percentage of families who received a disposal bag filled their child’s opioid prescription (difference in proportions, −7.6%; 95% CI, −13.7% to −1.4%). Most parents in both groups reported that their child’s postoperative pain control was good (57 of 92 [62.0%] vs 53 of 89 [59.6%]) and was similar to (41 [44.6%] vs 39 [43.8%]) or better than (39 [42.4%] vs 39 [43.8%]) what they had expected. The number of days that opioids were used and the total number of doses taken and left over did not differ by group. Most families had opioid pain medication left over after the resolution of their child’s pain (77 for each group; 83.7% vs 86.5%), and this did not differ by group (difference in proportions, −2.8%; 95% CI, −13.2% to 7.5%). Among parents reporting disposal, the majority not receiving a disposal bag disposed of their child’s opioids by pouring them in the toilet or sink (34 of 54 [63.0%]), whereas the majority of those receiving a disposal bag used it for opioid disposal (60 of 67 [89.6%]). Opioid storage locations were similar across groups, with approximately 60% of families storing medications on a counter or in an unlocked closet, drawer, or cabinet. Among the parents or guardians who did not dispose of their child’s opioids, most cited no barriers to disposal but instead indicated that they planned to dispose of the medication (7 of 10 [70.0%] vs 18 of 23 [78.3%]). Ten (10.9%) of the parents or guardians who received a disposal bag reported using the bag to dispose of other medications in their home, 7 of whom also used the bag to dispose of their child’s leftover opioid pain medication (Table 2; eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

Table 2. Analyses of Primary and Secondary Outcomes.

| Outcome | No. (%) of Participants | Difference, Proportion (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disposal Bag (n = 92) | Standard Care (n = 89) | ||

| Primary outcome | |||

| Proper opioid disposala | 66 (71.7) | 50 (56.2) | 15.5 (1.7 to 29.3)b |

| Secondary outcome | |||

| Filled opioid prescription | 84 (91.3) | 88 (98.9) | −7.6 (−13.7 to −1.4) |

| Parent or guardian rating of child’s overall postoperative pain control | |||

| Poor | 4 (4.4) | 2 (2.3) | 2.1 (−12.4 to 16.7) |

| Adequate | 31 (33.7) | 34 (38.2) | −4.5 (−18.9 to 10.2) |

| Good | 57 (62.0) | 53 (59.6) | 2.4 (−12.4 to 16.7) |

| Parent or guardian rating of child’s overall postoperative pain control compared with their expectation | |||

| Worse | 12 (13.0) | 11 (12.4) | 0.6 (−9.0 to 10.4) |

| About what was expected | 41 (44.6) | 39 (43.8) | 0.8 (−13.7 to 15.2) |

| Better | 39 (42.4) | 39 (43.8) | −1.4 (−15.9 to 13.0) |

| No. of days opioids were used (91 for bag, 88 for standard care)c | |||

| 0 | 31 (34.1) | 21 (23.9) | 10.2 (−3.0 to 23.4) |

| 1-3 | 31 (24.1) | 29 (33.0) | −8.9 (−12.7 to 14.9) |

| 4-7 | 25 (27.5) | 33 (37.5) | −10.0 (−23.7 to 3.6) |

| >7 | 4 (4.4) | 5 (5.7) | −1.3 (−7.7 to 5.1) |

| No. of opioid doses (85 for bag, 73 for standard care)c | |||

| 0 | 31 (36.5) | 21 (28.8) | 7.7 (−6.9 to 22.3) |

| 1 | 5 (5.9) | 9 (12.3) | −6.4 (−15.5 to 2.6) |

| 2 | 14 (16.5) | 10 (13.7) | 2.8 (−8.4 to 13.9) |

| 3 | 5 (5.9) | 2 (2.7) | 3.2 (−3.1 to 9.4) |

| 4 | 7 (8.2) | 4 (5.5) | 2.7 (−5.1 to 10.6) |

| ≥5 | 23 (27.1) | 27 (37.0) | −9.9 (−24.5 to 4.6) |

| No. of leftover opioid doses (85 for bag, 73 for standard care)c | |||

| 0 | 11 (12.9) | 5 (6.9) | 6.0 (−3.1 to 15.3) |

| 1-5 | 19 (22.4) | 13 (17.8) | 4.6 (−7.9 to 17.0) |

| 6-10 | 23 (27.1) | 20 (27.4) | −0.3 (−14.3 to 13.6) |

| 11-15 | 21 (24.7) | 24 (32.9) | −8.2 (−22.3 to 6.0) |

| >15 | 11 (12.9) | 11 (15.1) | −2.2 (−13.0 to 8.8) |

| Any opioids left over after postoperative pain resolution | 77 (83.7) | 77 (86.5) | −2.8 (−13.2 to 7.5) |

| Opioid disposal by any method | 67 (72.8) | 54 (60.7) | 12.1 (−1.5 to 25.8) |

| Method of disposal (67 for bag, 54 for standard care) | |||

| Drug disposal bag | 60 (89.6) | 0 | 89.6 (78.8 to 95.8) |

| Toilet or sink | 6 (9.0) | 34 (63.0) | −54.0 (−67.9 to −37.8) |

| Threw in trash after combining with unpalatable substance | 0 | 7 (13.0) | −13.0 (−30.2 to 5.1) |

| Drug take-back event | 0 | 2 (3.7) | −3.7 (−21.3 to 14.2) |

| Law enforcement agency | 0 | 3 (5.6) | −5.6 (−23.1 to 12.4) |

| Authorized pharmacy | 0 | 4 (7.4) | −7.4 (−24.9 to 10.6) |

| Threw in trash as isd | 1 (1.5) | 3 (5.6) | −4.1 (−21.6 to 13.9) |

| Dumped in backyardd | 0 | 1 (1.9) | −1.9 (−19.6 to 16.0) |

| Storage location (83 for bag, 87 for standard care) | |||

| On a counter | 17 (20.5) | 13 (14.9) | 5.6 (−9.7 to 20.3) |

| In an unlocked closet, cabinet, or drawer | 31 (37.4) | 37 (42.5) | −5.1 (−20.2 to 9.9) |

| In a purse, backpack, or other carrier | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (−15.0 to 15.2) |

| In a locked box, closet, cabinet, or drawer | 32 (38.6) | 33 (37.9) | 0.7 (−14.5 to 15.6) |

| On top of refrigerator | 2 (2.4) | 3 (3.5) | −1.1 (−16.1 to 14.2) |

| Barriers to disposal (10 for bag, 23 for standard care)e | |||

| Inconvenient | 1 (10.0) | 1 (4.4) | 5.6 (−30.7 to 41.8) |

| Not sure how to get rid of it | 2 (20.0) | 5 (21.7) | −1.7 (−37.8 to 34.8) |

| Want to keep in case my child needs it later | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Want to keep in case someone else in my household needs it later | 0 | 1 (4.4) | −4.4 (−40.2 to 32.3) |

| I wasn’t told how to dispose of it | 0 | 1 (4.4) | −4.4 (−40.2 to 32.3) |

| Planning to dispose, just haven’t gotten around to it yet | 7 (70.0) | 18 (78.3) | −8.3 (−44.0 to 28.3) |

| Used disposal bag to dispose of other medications | 10 (10.9) | NA | NA |

| Primary outcome (per protocol analysis)f | |||

| Proper opioid disposal (77 each group) | 66 (85.7) | 50 (64.9) | 20.8 (7.6 to 34.0) |

| Opioid disposal by any method (77 each group) | 67 (87.0) | 54 (70.1) | 16.9 (4.2 to 29.6) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Defined as the disposal of unused opioids by a US Food and Drug Administration–recommended method or by using a disposal bag.

P = .03.

Evaluated only for participants who either did not fill an opioid prescription or did fill an opioid prescription and could recall the number of days or doses.

Not considered a proper method of opioid disposal.

Some parents or guardians cited multiple reasons for not disposing of their child’s opioid pain medication.

Includes only parents or guardians who filled their child’s opioid prescription and who had leftover opioids after the resolution of their child’s pain.

In analysis testing for differences in the effect of drug disposal bag provision by caregiver health literacy or receipt of an opioid consent form, we found no significant treatment effect heterogeneity on either the additive scale or relative scale (eTable2 in Supplement 2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effect of drug disposal product provision on the rate of postoperative opioid disposal among families of children undergoing surgery. We found an approximately 20% increase in the rate of proper opioid disposal with the provision of a drug disposal bag. We also found a higher than expected rate of opioid disposal among families that did not receive a disposal bag, which likely reflects the influence of the standardized, multimodal, opioid-related education provided to families of surgical patients at our institution.

We speculate that the provision of a drug disposal bag improved opioid disposal through several mechanisms, including convenience and the bag serving as a physical reminder of the need to dispose of leftover medication. Currently, the FDA recommends that opioids be disposed of either through drug take-back events or drop-off boxes, or if these are not readily available, that opioids be disposed of by flushing them down the toilet to avoid any potential for deliberate or unintentional misuse. If take-back options are not readily available, the FDA also recommends that patients dispose of unused or expired medications by mixing them with an unpalatable substance before disposing of them in the garbage.27 However, for opioids, flushing is recommended over mixing with unpalatable substances because such mixing does not prevent medications from being recovered and abused.29 In contrast to mixing with unpalatable substances, the activated charcoal in the drug disposal bags used in this study irretrievably adsorbs nearly all of the medication placed in the bag.20,29

Drug take-back events and drop-off boxes have become more prevalent in recent years, particularly since the 2014 ruling by the US Drug Enforcement Administration allowing pharmacies to become registered collectors. However, these disposal methods still capture only a small portion of the prescribed opioids present in the community.24 This is likely attributable to the inconvenience of these methods for many patients and families. In the present study, only 7 caregivers in the standard care group took their child’s leftover medication to a take-back event or drop-off box at a law enforcement agency or authorized pharmacy, and no families in the intervention group did so. Thus, it appeared in the present study that ease of access to a safe and simple method of drug disposal was preferable to disposal at designated sites. The disposal bag may also have served as a physical reminder to dispose of leftover medication. Finally, it is possible that some families elected to use the disposal bag to reduce the potential environmental issues associated with flushing opioids.

Previous studies have emphasized the importance of education to encourage proper opioid disposal. One study, which randomized adult patients undergoing dental surgery to receive information on local pharmacy-based opioid disposal sites vs routine postoperative instructions, found no increase in the proportion of patients who either disposed of or reported the intent to dispose of their unused opioids.14 A study by Rose et al15 evaluated the association between the provision of an educational pamphlet on safe opioid storage and opioid disposal among adults undergoing hip or knee arthroplasty. They found a significant increase, from 5% to 27%, in the proportion of patients reporting proper opioid disposal among those who had discontinued use of opioids by 4 weeks after surgery. However, in that study, only half of patients in both groups had discontinued their use of opioids by 4 weeks after surgery. In another study that provided an educational brochure describing the methods recommended by the FDA of drug disposal to adult patients undergoing plastic surgery, those patients receiving the brochure were more likely to dispose of their unused opioids (22% vs 11%).16 By contrast, another recent investigation by Cabo et al17 found no association of providing a similar brochure with opioid disposal among adult patients undergoing urologic surgery, most of whom preferred to keep their opioids for fear of the return of disease-specific pain or other pain. A recent study investigating the result of providing adult cancer patients in a palliative care clinic with educational material on safe opioid use, storage, and disposal showed that patients receiving the education were less likely to practice unsafe opioid use or storage and were less likely to have unused medications at home.18 Given the findings of these investigations in adults, we hypothesized that educational materials alone would have a modest effect on proper opioid disposal after pediatric surgery. However, the overall rate of disposal among families who did not receive a disposal bag in our trial was substantially higher than anticipated and likely reflects the efforts by our institution to educate all families receiving an opioid prescription about proper methods of opioid disposal. Families in our surgery centers who receive an opioid prescription for their child are provided with educational materials on proper opioid use, storage, and disposal.22 These materials are discussed, and families are also shown a video containing the information.23 Although education is a key component of safe opioid handling and disposal, the present study shows that providing a simple tool enabling families to safely dispose of leftover opioids in their home garbage increases the rate of proper disposal beyond that of education alone.

An unanticipated finding from this study was the significantly lower rate of opioid prescription filling among families who received a drug disposal bag. This finding may indicate that simply providing a drug disposal bag to families further emphasizes the dangers of opioid use. This decreased prescription fill rate did not translate into less adequate pain control in the children whose families received a drug disposal bag. However, further research into this finding is needed. Another concerning finding was that 60% of families stored opioids in unsecured locations. This suggests that additional interventions may be needed to promote the proper storage of postoperative opioids. Furthermore, most participants had many doses of opioid pain medication left over after the resolution of their child’s pain. This suggests an opportunity for further decreases in the amount of opioids prescribed.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, we included only parents or guardians of pediatric patients undergoing ambulatory otolaryngologic or urologic surgery. Most patients were young children and therefore received opioids in liquid form. Future research is needed for older pediatric patients prescribed pills and for patients who require opioids for pain due to traumatic injuries or major surgery. Second, this study was performed at a single institution that provides standardized education to surgical patients and families regarding opioid use, storage, and disposal. Third, the specific drug disposal bags we used cost $5.00 to $7.00 per bag, depending on size. Although organizations ordering a large number of bags can obtain them at a decreased cost, many patients and families may not be willing to pay out of pocket for these or similar products. Therefore, to see a large contribution of these products to opioid disposal, it is likely necessary to provide them to families at no cost.

Conclusions

The present study showed that providing families of children undergoing surgery with an easy to use drug disposal product increased proper opioid disposal rates. The opioid epidemic requires a multifaceted approach to curb the still increasing rates of opioid-related morbidity and mortality in this country. Providing a convenient method for safe disposal of opioids can complement the ongoing prescribing reduction efforts aimed at decreasing opioid misuse.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Baseline Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of the per Protocol Cohort

eTable 2. Primary Outcome Analyses Stratified by Surgical Subspecialty

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Gaither JR, Leventhal JM, Ryan SA, Camenga DR. National trends in hospitalizations for opioid poisonings among children and adolescents, 1997 to 2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(12):-. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen JD, Casavant MJ, Spiller HA, Chounthirath T, Hodges NL, Smith GA. Prescription opioid exposures among children and adolescents in the United States: 2000-2015. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4):e20163382. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCabe SE, West BT, Veliz P, McCabe VV, Stoddard SA, Boyd CJ. Trends in medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids among US adolescents: 1976-2015. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4):e20162387. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2015. NCHS data brief, No. 273. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db273.htm. Published February 2017. Accessed December 5, 2018.

- 5.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2016 national survey on drug use and health: detailed tables. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2016/NSDUH-DetTabs-2016.pdf. Published September 7, 2017. Accessed March 20, 2019.

- 6.McCabe SE, West BT, Boyd CJ. Leftover prescription opioids and nonmedical use among high school seniors: a multi-cohort national study. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(4):480-485. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkelstein Y, Macdonald EM, Gonzalez A, Sivilotti MLA, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN; Canadian Drug Safety And Effectiveness Research Network (CDSERN) . Overdose risk in young children of women prescribed opioids. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3):e20162887. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung CP, Callahan ST, Cooper WO, et al. Outpatient opioid prescriptions for children and opioid-related adverse events. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2):e20172156. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill MV, McMahon ML, Stucke RS, Barth RJ Jr. Wide variation and excessive dosage of opioid prescriptions for common general surgical procedures. Ann Surg. 2017;265(4):709-714. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voepel-Lewis T, Wagner D, Tait AR. Leftover prescription opioids after minor procedures: an unwitting source for accidental overdose in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(5):497-498. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bicket MC, Long JJ, Pronovost PJ, Alexander GC, Wu CL. Prescription opioid analgesics commonly unused after surgery: a systematic review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(11):1066-1071. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monitto CL, Hsu A, Gao S, et al. Opioid prescribing for the treatment of acute pain in children on hospital discharge. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(6):2113-2122. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feinberg AE, Chesney TR, Srikandarajah S, Acuna SA, McLeod RS; Best Practice in Surgery Group . Opioid Use After discharge in postoperative patients: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2018;267(6):1056-1062. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maughan BC, Hersh EV, Shofer FS, et al. Unused opioid analgesics and drug disposal following outpatient dental surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;168:328-334. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rose P, Sakai J, Argue R, Froehlich K, Tang R. Opioid information pamphlet increases postoperative opioid disposal rates: a before versus after quality improvement study. Can J Anaesth. 2016;63(1):31-37. doi: 10.1007/s12630-015-0502-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasak JM, Roth Bettlach CL, Santosa KB, Larson EL, Stroud J, Mackinnon SE. Empowering post-surgical patients to improve opioid disposal: a before and after quality improvement study. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(3):235-240.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.11.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cabo J, Hsi RS, Scarpato KR. Postoperative opiate use in urological patients: a quality improvement study aimed at improving opiate disposal practices. J Urol. 2019;201(2):371-376. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2018.09.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de la Cruz M, Reddy A, Balankari V, et al. The impact of an educational program on patient practices for safe use, storage, and disposal of opioids at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist. 2017;22(1):115-121. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deterra Drug Deactivation System https://deterrasystem.com/. Accessed January 15, 2018.

- 20.Community Environmental Health Strategies LLC for San Francisco Department of the Environment Overview of eight medicine disposal products. https://sfenvironment.org/sites/default/files/fliers/files/overviewmedicinedisposalproducts_21april2017.pdf. Published April 21, 2017. Accessed April 1, 2018.

- 21.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nationwide Children’s Hospital. Important facts to know when taking opioids. https://www.nationwidechildrens.org/family-resources-education/health-wellness-and-safety-resources/helping-hands/important-things-to-know-when-taking-opioids. Accessed December 7, 2018.

- 23.Nationwide Children’s Hospital. Opioid safety protocol for home [YouTube video]. https://www.nationwidechildrens.org/specialties/comprehensive-pain-management-clinic/pain-treatment-therapy-options/opioid-safety. Accessed December 7, 2018.

- 24.Egan KL, Gregory E, Sparks M, Wolfson M. From dispensed to disposed: evaluating the effectiveness of disposal programs through a comparison with prescription drug monitoring program data. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43(1):69-77. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2016.1240801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):588-594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wallace LS, Wexler RK, Miser WF, McDougle L, Haddox JD. Development and validation of the Patient Opioid Education Measure. J Pain Res. 2013;6:663-681. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S50715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. disposal of unused medicines: what you should know. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resourcesforyou/consumers/buyingusingmedicinesafely/ensuringsafeuseofmedicine/safedisposalofmedicines/ucm186187.htm. Accessed August 31, 2018.

- 28.Brummett CM, Steiger R, Englesbe M, et al. Effect of an activated charcoal bag on disposal of unused opioids after an outpatient surgical procedure: a randomized clinical trial. [published online March 27, 2019]. JAMA Surg. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fowler W. Deterra system deactivation of unused drugs: comparison between Deterra ingredients and others recommended in federal and SmartRx disposal guidelines. https://deterrasystem.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/White-Paper-updated-1-3-17.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Baseline Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of the per Protocol Cohort

eTable 2. Primary Outcome Analyses Stratified by Surgical Subspecialty

Data Sharing Statement