Abstract

This pilot study explored the value of localized index node removal after neoadjuvant immunotherapy in patients with stage III melanoma, for use as a response indicator to guide the extent of completion lymph node dissection.

Promising technology

Introduction

The outcome of patients diagnosed with stage III melanoma is poor, with a 5‐year overall survival (OS) rate of less than 50 per cent1. Adjuvant checkpoint inhibition therapy significantly improves 5‐year relapse‐free survival (RFS) and OS2 rates, as well as median RFS3, 4.

There is growing evidence that neoadjuvant checkpoint inhibition (NACI) may be an even more favourable approach. In a previous phase Ib study (OpACIN)5, neoadjuvant was compared with adjuvant ipilimumab and nivolumab. The pathological response rate was 78 per cent in the neoadjuvant arm and, after a median follow‐up of 25·6 months, none of the responders had relapsed. In a currently ongoing phase II study, the aim is to identify the optimal neoadjuvant combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab in patients with macroscopic stage III melanoma (OpACIN‐neo; preregistered at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02977052).

The promising results of NACI raise the question of whether pathological complete (pCR) or near‐complete (near‐pCR) responders after NACI can safely avoid subsequent completion lymph node dissection (CLND). A prerequisite for such an approach would be a reliable indicator of pathological response for the entire lymph node basin.

One method could be to localize a single positive lymph node before the start of NACI, and remove it after NACI to use to assess the pathological response of the entire basin. This approach, using radioactive seed localization, has been shown to be of value in the treatment of node‐positive breast cancer, where it reduced the proportion of CLNDs after neoadjuvant systemic therapy by 82 per cent6. Unfortunately, the use of radioactive seeds is associated with operational challenges and risks7, and the technology has been applied only sparingly for melanoma8.

Recently, a novel magnetic surgical localization method has been used to overcome the challenges of radioactive seeds9. This technology was first tested in a feasibility study in breast cancer10. Subsequently, a second pilot study was designed to test the feasibility of this technology for targeted pathological lymph node removal in melanoma: the Magnetic Seed Localization for Melanoma (MeMaLoc) study (preregistered at the Dutch Centrale Commissie Mensgebonden Onderzoek: https://bit.ly/2SHouy4, NL58293.031.16).

The objective of the present study was to investigate whether targeted removal of a single pathological (index) node using magnetic seed localization is feasible, and whether this index node is a reliable indicator of pathological response in the entire lymph node basin in patients with stage III melanoma treated with NACI. To address these objectives, the index node was marked with the magnetic seed, removed surgically, and analysed separately from the rest of the lymph node basin after 6 weeks of NACI.

Methods

Twelve patients with resectable stage III melanoma and at least one measurable lymph node metastasis according to the RECIST 1.1 criteria11 were recruited to both the OpACIN‐neo and the MeMaLoc study. All patients signed informed consent for both studies separately. Both studies were approved by the ethics committee of the Netherlands Cancer Institute (Amsterdam, the Netherlands); additional approval was obtained to enrol patients in both studies simultaneously.

In the OpACIN‐neo study, patients were assigned randomly to one of three combination schemes of ipilimumab plus nivolumab. Some 2 weeks after enrolment, generally on the day of the second course of immunotherapy, patients were scheduled for an appointment in the radiology department.

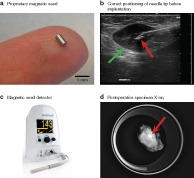

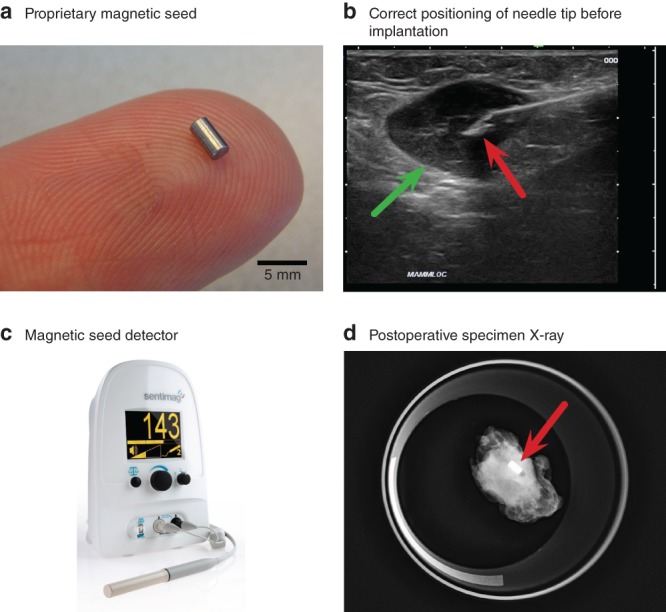

Under local anaesthesia, an experienced radiologist performed ultrasound‐guided placement of a single rice grain‐sized magnetic seed (1·7 × 3·5 mm) (Fig. 1 a) developed in‐house into the largest involved lymph node using a 14‐G needle (Fig. 1 b). The shortest distance between skin and seed on ultrasound imaging was recorded.

Figure 1.

Overview of the magnetic seed localization procedure

a Proprietary magnetic seed on finger. b Correct positioning of the needle tip (red arrow) in lymph node (green arrow) before implantation. c Magnetic detector (Endomag Sentimag®) used during surgery to detect the seed. d Postoperative specimen X‐ray with magnetic seed (red arrow) in situ.

CLND was performed 6 weeks after the start of NACI. Before and occasionally during surgery, a commercially available magnetic detection system (Sentimag®; Endomag, Cambridge, UK) (Fig. 1 c) was used to detect the magnetic seed and guide surgery. The ability to detect the seed transcutaneously was recorded. The probe was covered by a sterile sheath during surgery. Surgeons were instructed to remove the marked lymph node first and complete the rest of the CLND subsequently.

The Sentimag® is a magnetic proximity sensing system that detects the magnetic seed developed in‐house and functions like a γ probe, but without the need for radioactivity. It is highly sensitive to any conductive material near the probe. Therefore, at least during the short moments of measurement, the use of standard metal surgical instruments is precluded. During these moments, surgeons may opt either to remove all instruments surrounding the probe or to resort to polymer tools (SUSI ®; B. Braun, Tuttlingen, Germany).

After removal of the index node, the specimen was sent for X‐ray imaging to confirm the presence of the magnetic seed in the node (Fig. 1 d). Surgeons were asked to complete the System Usability Scale (Appendix S1, supporting information) to obtain data on satisfaction with the novel magnetic technology, and an application‐specific questionnaire to assess the feasibility of the magnetic technology for targeted node removal (Appendix S2, supporting information).

Both specimens (index node and rest of basin) were sent for separate pathological assessment, and revised centrally according to the International Neoadjuvant Melanoma Consortium (INCM) scoring system12. The total number of nodes in the specimen was counted, as well as the number of nodes that had evidence of viable and/or treated tumour.

The therapeutic response was determined by estimating the percentage of viable tumour cells (vTCs) relative to the entire area with signs of viable and/or treated tumour, and categorized as follows12: pCR, 0 per cent vTCs; near‐pCR, more than 0 to 10 per cent vTCs; pathological partial response (pPR), more than 10 to 50 per cent vTCs; pathological no response (pNR), more than 50 per cent vTCs.

The index node was determined a representative indicator of therapy response if it was congruent with the therapeutic response in the total basin.

Continuous variables are described as median (i.q.r.) values.

Results

Between February 2017 and May 2018, 12 patients (6 men) were included; their median age was 55 years and the location of lymph node metastasis was axillary in seven patients and inguinal in five.

Four different surgeons, experienced with using γ probes for sentinel lymph node biopsies but with no previous experience of magnetic localization, performed the 12 procedures. Seeds were in situ for a median of 23 (i.q.r. 21–27) days. All 12 magnetic seeds were detected transcutaneously and removed successfully with the index node. The magnetic localization technology was scored with a median score of 98 of 100 on the System Usability Scale (Table 1). Surgeons rated that the technology was intuitive to use (4·8 of 5) and that they would like to use the technology for future procedures (4·8 of 5) (Fig. S1, supporting information). Although instructed to start surgery with targeted removal of the index node guided by the detector, in five patients the surgeon identified the marked node using the detector before and during the procedure, but removed it from the rest of the specimen immediately after surgery.

Table 1.

Overall results

| No. of patients* (n = 12) | |

|---|---|

| Seed in situ (days) † | 23 (21–27) |

| Skin to seed distance on ultrasound imaging (mm) † | 10 (5–15) |

| Surgery | |

| Transcutaneous detection | 12 |

| Retrieval rate | 12 |

| System Usability Scale score† | 98 (90–100) |

| Pathology | |

| Total node count per patient† | 24 (16–34) |

| Node count with evidence of viable or treated tumour† | 2 (1–3) |

| Response | |

| Index node | |

| pCR | 7 |

| Near‐pCR | 3 |

| pPR | 1 |

| pNR | 1 |

| Total basin | |

| pCR | 7 |

| Near‐pCR | 3 |

| pPR | 1 |

| pNR | 1 |

| Index node congruent with total basin | 12 |

Unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (i.q.r.). pCR, pathological complete response; pPR, pathological partial response; pNR, pathological no response.

Pathological assessment of the specimens showed that seven of the 12 patients had a pCR, three had a near‐pCR, one had a pPR and one a pNR (Table S1, supporting information).

In all cases, the therapeutic response of the index node was congruent with that in the total basin.

Discussion

This study shows that it is feasible before surgery to localize, and during surgery to remove, the largest (index) lymph node using a proprietary in‐house developed magnetic seed and an intraoperative magnetic detector as guidance9. All magnetic seeds were detected transcutaneously. Four independent surgeons rated the magnetic technology favourably for each procedure and stated they would like to use the technology for future procedures.

All index node responses were congruent with the total basin responses. This suggests that the index node can be considered a reliable indicator of therapeutic response.

If, in future, patients with a (near‐)complete response (pCR or near‐pCR) could safely avoid CLND, ten of the 12 patients in this study would have been spared CLND. The percentage of patients in whom CLND can be omitted is dependent upon the response rate to NACI. Being aware of the very small sample size of the pilot study, these results seem promising but need rigorous scientific assessment, preferably using an adequately powered prospective trial. If confirmed, this treatment could improve the care of patients with stage III melanoma after NACI, similar to the current practice in breast cancer6, 13, 14.

The present study is limited by its small sample size, and it was not powered to detect a significant outcome. In addition, (neo‐)adjuvant checkpoint inhibition therapy is currently not standard of care, because the potential survival benefit and cost‐effectiveness still need to be established.

In five patients, the surgeon localized the node before and during surgery, but removed it surgically from the rest of the basin only after surgery. The reason for this was that the surgical approach for a selective node removal and CLND is sometimes notably different. This depends on the location of the index node within the basin. First removing the index node might have jeopardized the success of the subsequent CLND in these patients. This limitation is, of course, no longer present when subsequent CLND is not necessary.

Supporting information

Appendix S1 System Usability Scale

Appendix S2 Postoperative application‐specific questionnaire

Table S1 Results per patient

Fig. S1 Results of application‐specific questionnaire for each procedure

Disclosure

B.S., T.J.M.R. and B.t.H. are inventors on the patent that describes the magnetic seed used in this study. B.S. and T.J.M.R. are shareholders in a start‐up company that aims to bring this technology to commercial fruition. C.U.B. reports personal fees for advisory roles for MSD, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Roche, GSK, Novartis, Pfizer, Genmab and Lilly, and grants from Bristol‐Myers Squibb, NanoString and Novartis, outside the submitted work. E.A.R. reports travel support from NanoString Technologies and MSD, outside the submitted work. V.F. and A.C.J.v.A declare advisory board/consultancy agreement and research grant received from Amgen. A.C.J.v.A declares advisory board/consultancy agreements for Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Novartis, MSD–Merck and Merck–Pfizer. A.C.J.v.A and M.W.W. declare a research grant from Novartis.

The authors declare no other conflict of interest.

Presented to the meeting of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Melanoma Group, Majorca, Spain, October 2018, and the 2018 Congress of the European Society for Medical Oncology, Munich, Germany, October 2018; published in abstract form as Ann Oncol 2018; 29(Suppl 8): viii463

References

- 1. Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, Thompson JF, Atkins MB, Byrd DR et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 6199–6206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 711–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Postow MA, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, Robert C, Grossmann K, McDermott D et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2006–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, Arance A, Grob JJ, Mortier L et al.; KEYNOTE-006 investigators. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2521–2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blank CU, Rozeman EA, Fanchi LF, Sikorska K, van de Wiel B, Kvistborg P et al. Neoadjuvant versus adjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab in macroscopic stage III melanoma. Nat Med 2018; 24: 1655–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van der Noordaa MEM, van Duijnhoven FH, Straver ME, Groen EJ, Stokkel M, Loo CE et al. Major reduction in axillary lymph node dissections after neoadjuvant systemic therapy for node‐positive breast cancer by combining PET/CT and the MARI procedure. Ann Surg Oncol 2018; 25: 1512–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jakub J, Gray R. Starting a radioactive seed localization program. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22: 3197–3202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fleming MD, Pockaj BA, Hansen AJ, Gray RJ, Patel MD. Radioactive seed localization for excision of non‐palpable in‐transit metastatic melanoma. Radiol Case Rep 2015; 1: 54–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schermers B, ten Haken B, Muller SH, van der Hage JA, Ruers TJM. Optimization of an implantable magnetic marker for surgical localization of breast cancer. Biomed Phys Eng Express 2018; 4: 67001. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schermers B, van der Hage JA, Loo CE, Vrancken Peeters MTFD, Winter‐Warnars HAO, van Duijnhoven F et al. Feasibility of magnetic marker localisation for non‐palpable breast cancer. Breast 2017; 33: 50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009; 45: 228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tetzlaff MT, Messina JL, Stein JE, Xu X, Amaria RN, Blank CU et al. Pathological assessment of resection specimens after neoadjuvant therapy for metastatic melanoma. Ann Oncol 2018; 29: 1861–1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Donker M, Straver ME, Wesseling J, Loo CE, Schot M, Drukker CA et al. Marking axillary lymph nodes with radioactive iodine seeds for axillary staging after neoadjuvant systemic treatment in breast cancer patients: the MARI procedure. Ann Surg 2015; 261: 378–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mieog JS, van der Hage JA, van de Velde CJ. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for operable breast cancer. Br J Surg 2007; 94: 1189–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 System Usability Scale

Appendix S2 Postoperative application‐specific questionnaire

Table S1 Results per patient

Fig. S1 Results of application‐specific questionnaire for each procedure