Abstract

The Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) has shown to strengthen health providers' skills in the provision of breastfeeding counselling and support, which have led to improvements in breastfeeding outcomes. In Malawi, where BFHI was introduced in 1993 but later languished due to losses in funding, the Maternal and Child Survival Program supported the Malawi Ministry of Health (MOH) in the revitalization and scale‐up of BFHI in 54 health facilities across all 28 districts of the country. This paper describes the revitalization and scale‐up process within the context of an integrated health project; successes, challenges, and lessons learned with BFHI implementation; and the future of BFHI in Malawi. More than 80,000 mothers received counselling on exclusive breastfeeding following childbirth prior to discharge from the health facility. Early initiation of breastfeeding was tracked quarterly from baseline through endline via routine MOH health facility data. Increases in early initiation of breastfeeding were seen in two of the three regions of Malawi: by 2% in the Central region and 6% in the Southern region. Greater integration of BFHI into Malawi's health system is recommended, including improved preservice and in‐service trainings for health providers to include expanded BFHI content, increased country financial investments in BFHI, and integration of BFHI into national clinical guidelines, protocols, and nutrition and health policies.

Keywords: Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative; breastfeeding; breastfeeding initiation, implementation science, scale up; infant and young child feeding

Key messages.

BFHI is critical for equipping health providers with skills on breastfeeding counselling and to improve rates of early initiation of breastfeeding.

BFHI messages and activities can be integrated through other health areas, including newborn, routine immunization, and post‐partum family planning.

Engagement of local leadership at the community, district, and national levels was critical to the revitalization and scale‐up of BFHI in Malawi.

Full integration of BFHI into the health system requires preservice training, improved data monitoring and quality, financial investments, and expansion of breastfeeding support at the community level.

1. INTRODUCTION

Breastfeeding is one of the most cost‐effective health interventions, with a return of between $4 and $35 for every $1 invested (Hoddinott, Alderman, Behrman, Haddad, & Horton, 2013; Shekar, Kakietek, Eberwein, & Walters, 2017). As evidenced by a body of work supporting a number of health and economic benefits for societies, mothers, and children, breastfeeding protects against infant mortality (Sankar et al., 2015), diarrhoea, and respiratory infections (Horta & Victora, 2013), otitis media (Bowatte et al., 2015), asthma (Victora et al., 2016), overweight and obesity (Horta, Loret De Mola, & Victora, 2015), and type 2 diabetes (Horta et al., 2015) and is associated with higher intelligence quotient in children and adolescents (Horta et al., 2015; Kramer et al., 2008). The economic losses from not breastfeeding and its effect on cognitive deficits can lead to significant economic burden due to lost productivity (Rollins et al., 2016) and lower wages associated with lower intelligence quotient.

Launched globally by UNICEF and the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1991 and since implemented in over 160 countries (Labbok, 2012), the Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) aims to promote, protect, and support breastfeeding (WHO, 1998) in maternity and newborn facilities (WHO & UNICEF, 2018). With varying degrees of sustainability and continuation of their BFHI programmes, more than 20,000 facilities have received Baby‐Friendly designation since 1991 through adherence to the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding (the Ten Steps; WHO & UNICEF, 2009b; Labbok, 2012), which are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding

| 1 | Have a written breastfeeding policy that is routinely communicated to all health care staff. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Train all health care staff in skills necessary to implement this policy. |

| 3 | Inform all pregnant women about the benefits and management of breastfeeding. |

| 4 | Help mothers initiate breastfeeding within a half‐hour of birth. |

| 5 | Show mothers how to breastfeed, and how to maintain lactation even if they should be separated from their infants. |

| 6 | Give newborn infants no food or drink other than breast milk unless medically indicated. |

| 7 | Practise rooming in—allow mothers and infants to remain together—24 hours a day. |

| 8 | Encourage breastfeeding on demand. |

| 9 | Give no artificial teats or pacifiers (also called dummies or soothers) to breastfeeding infants. |

| 10 | Foster the establishment of breastfeeding support groups and refer mothers to them on discharge from the hospital or clinic. |

BFHI can aid countries in reaching the fifth goal of the World Health Assembly's Global Nutrition Targets 2025, which aims to improve exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) rates to at least 50% globally (WHO & UNICEF, 2014). Evidence reveals that BFHI positively impacts breastfeeding outcomes, including early initiation of breastfeeding and EBF rates (UNICEF & WHO, 2017). A systematic review of 58 studies in low‐, middle‐, and high‐income countries demonstrated that BFHI led to increases in EBF, early initiation of breastfeeding, breastfeeding duration, and any breastfeeding (Pérez‐Escamilla, Martinez, & Segura‐Pérez, 2016), with a dose–response relationship seen between the number of the Ten Steps a woman is exposed to and breastfeeding outcomes. Similarly, a 2015 systematic review and meta‐analysis by Sinha et al. of 195 studies from low‐, middle‐, and high‐income countries evaluating the effects of the Ten Steps on breastfeeding outcomes found that early initiation of breastfeeding <1 hr increased by 25% with adherence to the initiative (Sinha et al., 2015).

In Kuwait, BFHI implementation resulted in a twofold improvement in early initiation of breastfeeding following Baby‐Friendly designation (UNICEF & WHO, 2017). A study in Croatia using data following a national revitalization of BFHI in public hospitals demonstrated significant improvements in EBF rates following Baby‐Friendly designation in Croatia. Rates increased by 412%, 6 months following certification, from 8.9% to 45.6% (Zakarija‐Grković, Boban, Janković, Ćuže, & Burmaz, 2017). A cluster‐randomized trial in Belarus evaluating the effects of BFHI on breastfeeding outcomes in select hospitals showed that babies exposed to BFHI were significantly more likely to be exclusively breastfed at 3 months than those not exposed, 43% versus 6% (Kramer et al., 2008).

BFHI can contribute to improved health providers' capacity, skills, and attitudes around infant feeding, as well as provide protection and support for breastfeeding, leading to decreases in the use of breast milk substitutes (BMS; UNICEF & WHO, 2017; WHO, 2017). However, facilities and countries face the challenge of being able to maintain Baby‐Friendly designation, especially those with limited financial resources or monitoring systems in place (UNICEF & WHO, 2017). This is evidenced in that 28% of health facilities have been designated Baby‐Friendly at some point, yet only 10% of births globally occur in a Baby‐Friendly facility (Labbok, 2012; WHO, 2017). To address global and country‐level challenges around sustaining BFHI, UNICEF, and the WHO released updated BFHI implementation guidance in 2018 with recommendations on improving sustainability through key actions, including incorporating its activities into already existing national health platforms (WHO & UNICEF, 2018). This updated BFHI guidance includes changes to critical management procedures and key clinical practices in the Ten Steps (Aryeetey & Dykes, 2018) and was based on up‐to‐date, evidence‐based recommendations set forth in BFHI guidelines by the WHO and UNICEF (2017).

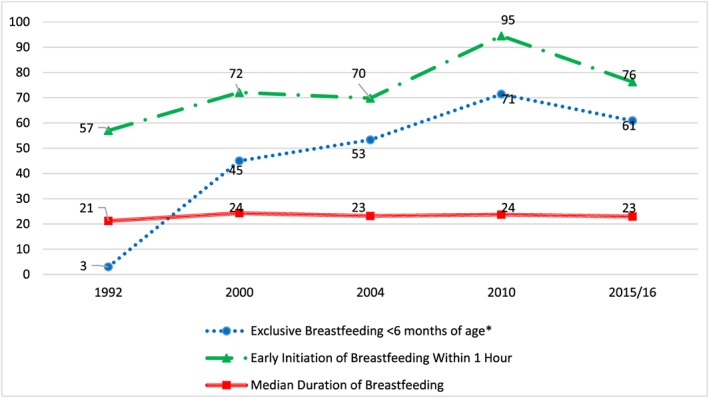

In Malawi, the Ministry of Health (MOH) made a commitment to improve breastfeeding practices through the adoption of BFHI, following the 1991 World Health Resolution Introduction of BFHI and the dismal national EBF rate of 3% reported in the 1992 Malawi Demographic and Health Survey (DHS; National Statistical Office Malawi & Macro International, 1994). BFHI was launched in the country with external funding in 1993, with 26 hospitals designated by the MOH as Baby‐Friendly from 1993 to 2004. Significant progress was made in breastfeeding practices, as shown in improvements in EBF rates to 45% in 2000 and 71% in 2010 (Figure 1; National Statistical Office Malawi & ORC Macro, 2001; National Statistical Office Malawi & IFC Macro, 2011).

Figure 1.

Trends in breastfeeding practices in Malawi (source: Malawi demographic health surveys)

In 2015, the MOH concentrated efforts on infant and young child feeding (IYCF) and commissioned an assessment of IYCF practices and initiatives in Malawi. Preliminary findings noted that there were no longer any Baby‐Friendly designated health facilities in Malawi, which was particularly worrying for the MOH. Further investigation into why BFHI had deteriorated revealed that adherence to the Ten Steps waned following the loss of BFHI funding in 2004, with minimal internal monitoring and supportive supervision measures for BFHI in place. In addition, confusion among health providers around infant feeding recommendations for HIV positive mothers led to further decline in adherence to the Ten Steps. This was partly attributed to by the delay in updating of national guidelines to reflect global guidance from WHO recommendations around prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission (PMTCT) released in 2006 and later revised in 2009 (WHO, 2010a, 2010b; Chinkonde, Hem, & Sundby, 2012).

The finding that previous Baby‐Friendly facilities had lost their designation by the MOH prompted the MOH to refocus on improving breastfeeding practices through revitalizing the BFHI. The MOH worked with partners in Malawi's IYCF Technical Working Group—including non‐governmental organizations, donor agencies, and UNICEF—to bring more attention to improving breastfeeding practices. The MOH wrote a proposal with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to revitalize BFHI, which was awarded in 2016 to the USAID‐funding Maternal and Child Survival Program (MCSP). Following this, the 2015–2016 Malawi DHS showed an EBF rate of 61%—a decrease from 2010—further demonstrating the need to reinvigorate efforts to improve breastfeeding practices (National Statistical Office Malawi & ICF Macro, 2017).

The objectives of this paper are to (a) discuss the revitalization and scale‐up process of BFHI in Malawi at the community, district, and national levels; (b) describe successes, challenges, and lessons learned from the revitalization and scale‐up of BFHI in Malawi; and (c) describe next steps and the future of BFHI in Malawi.

2. METHODS

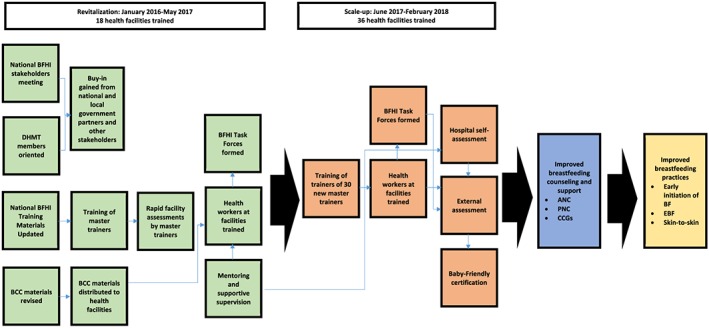

MCSP is a global, 5‐year USAID programme that aims to support high‐impact health interventions—alongside MOHs and other governmental and non‐governmental partners—in 25 high‐priority, low‐ and middle‐income countries to reduce maternal and child mortality (MCSP, 2018a). In Malawi, MCSP supported the Government of Malawi, MOH, from January 2016 to February 2018 in the revitalization and scale‐up of BFHI in 54 health facilities in all 28 districts of the country. A programme impact pathway was applied to understand and improve breastfeeding support and practices (Figure 2) under BFHI. Fifteen of the hospitals were selected to build on other programme efforts around maternity care implemented under the USAID‐funded Support for Service Delivery Integration project, which worked to strengthen health services in Malawi. In order to include smaller tier hospitals located in the community, centres of excellence were part of implementation activities. The selection criteria for participation in BFHI were hospitals or health facilities with a maternity ward, which provide basic emergency obstetric care and have the highest volume of births of health facilities in Malawi, ranging from 350 to 900 births per month.

Figure 2.

Malawi BFHI programme impact pathway

Throughout the implementation of BFHI programming efforts, ongoing documentation occurred via MCSP progress reports and collection of routine monitoring data. In addition, in March 2018, MCSP led a two‐day writing workshop in Lilongwe, Malawi, with the MOH, WHO, and a key member of the pool of BFHI master trainers. These key stakeholders were part of the introduction of BFHI in Malawi from 1993 to 2004 and worked with MCSP on the BFHI revitalization and scale‐up process from 2016 to 2018, which aided in distilling lessons learned.

To ascertain the progress in revitalization of BFHI, key government documents, MCSP programme documentation, and routine monitoring data were reviewed during the workshop. These documents included: (a) MOH BFHI training tools and job aids (Malawi MOH, 2016a); (b) MOH BFHI external assessment protocols; (c) national health and nutrition policies and strategies pertaining to IYCF, including the Malawi Child Health Strategy 2014–2020 (Malawi MOH, 2013), the Malawi National Nutrition Policy 2016–2020 (Malawi MOH, 2016d), and the National Strategic Plan for HIV and AIDS 2015–2020 (National AIDS Commission Malawi, 2014); (d) MCSP quarterly and annual reports providing programme implementation documentation; and (e) BFHI monitoring data, which included an indicator tracked through the MOH at the health facility level via District Health Information System 2 (DHIS 2), with the remaining indicators supported and tracked by MCSP.

With regard to routine MOH data and MCSP programme data, the following indicators were monitored under BFHI:

Tracked through MOH via DHIS 2:

-

i

Early initiation of breastfeeding—proportion of infants born at a BFHI‐trained health facility who are put to the breast within 1 hr of birth

MCSP‐supported BFHI indicators:

-

ii

Number of mothers who receive counselling on EBF upon discharge from a BFHI‐trained health facility following giving birth

-

iii

Number of health facilities trained on BFHI

-

iv

Number of master trainers refreshed and/or trained on BFHI

-

v

Number of health facility staff—clinical and support—trained on BFHI

-

vi

Number of community volunteers trained on BFHI

-

vii

Number of stakeholders oriented on BFHI

-

viii

Number of Area Development Committee (ADC) members oriented on BFHI

-

ix

Number of health surveillance assistants (HSAs) trained on BFHI

-

x

Number of district health management team members oriented on BFHI

-

xi

Number of health facilities that have undergone a successful external assessment by the MOH

-

xii

Number of health facilities designated Baby‐Friendly

Monitoring data for these indicators were tracked from May 2016 to February 2018. Data on indicators (i) and (ii) were recorded in the maternity registers at the health facility level by facility staff prior to data entry in the DHIS 2 by MOH data clerk staff. Indicators (iii) through (xii) were collected as part of the MCSP BFHI monitoring and evaluation package and reported in MCSP quarterly and annual reports. “Orientation” to BFHI is defined as bringing awareness to the initiative through education and advocacy to key individuals, groups, and/or organizations to gain support from those who are not directly involved in providing breastfeeding counselling and support but play an important role in acting as gatekeepers and/or policymakers at the community, district, or national level. “Training” on BFHI is defined as provision of education on the BFHI 20‐hr (Malawi MOH, 2016a), 5‐day course to individuals who will be directly involved with providing breastfeeding counselling and support to pregnant women and mothers and those responsible for supervising these staff.

3. RESULTS

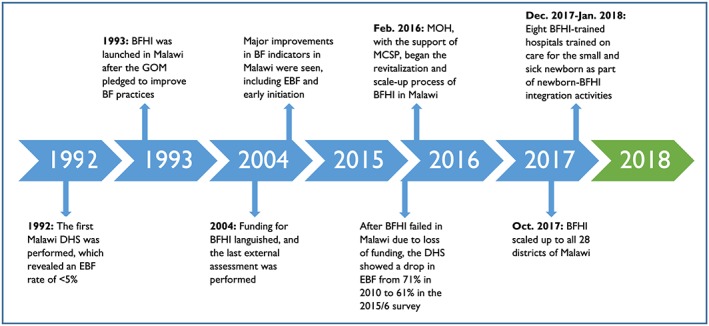

MCSP, alongside the MOH, led the implementation activities of the revitalization and scale‐up of BFHI in Malawi from February 2016 to March 2018 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

History of BFHI in Malawi

3.1. Attaining support for BFHI from the government and key stakeholders

Given the deterioration of BFHI following loss of funding in 2004 as well as the decreased EBF rate from 2010 to 2015/2016 (National Statistical Office Malawi, & IFC Macro, 2011; National Statistical Office Malawi & ICF Macro, 2017), the MOH expressed a strong desire to improve breastfeeding practices in Malawi. Because of significant advancements seen in breastfeeding practices following the introduction of BFHI in Malawi, they were committed to revitalizing BFHI and scaling‐up across the country. This served as the impetus for a June 2016 stakeholders meeting led by MCSP in partnership with the WHO and Malawi's IYCF Technical Working Group—which included physicians, nurses, and former BFHI master trainers for BFHI from 1993 to 2004. The meeting ascertained BFHI progress to date and put in place a timeline and plans for BFHI implementation in targeted hospitals.

3.2. Updating key country‐level BFHI documents to reflect changes in global guidance on IYCF and HIV

To prepare for the roll‐out of BFHI, in May 2016, the MOH, MCSP, and WHO adapted key country‐level training materials on IYCF and PMTCT for national use, based on the Ten Steps and training materials from the 2009 BFHI training package (WHO & UNICEF, 2009a, 2009b, 2009c). BFHI stakeholders agreed that involvement of BFHI master trainers, who were involved in BFHI efforts with the MOH during the 1990s and early 2000s, would be critical to the success of the revitalization process. These original BFHI master trainers led training and mentorship of Malawian health facility staff during the BFHI revitalization.

Prior to BFHI roll‐out, the following updates to country‐level training materials occurred:

In May 2016, a core team of 11 BFHI master trainers updated existing key messages and behaviour change communication (BCC) materials. They were revised to reflect the latest WHO and MOH guidelines on PMTCT (WHO, 2010b), include messages on the lactational amenorrhea method (LAM), and improve illustrations to be easier to interpret. This package of BCC materials was distributed to all hospitals trained on BFHI in Malawi.

In June 2016, 25 BFHI master trainers—including the original 11 BFHI master trainers—revised the WHO Breastfeeding Promotion and Support in a Baby‐Friendly Hospital: A 20‐hour Course for Maternity Staff (WHO & UNICEF, 2009a), as well as the external assessment protocols and monitoring tools for continued adherence to the Ten Steps. The revisions focused on PMTCT and LAM, to reflect WHO and MOH guidance. These adapted materials were compiled into a package (Table 2) for application in the training and mentoring of clinical and nonclinical health facility staff as well for undergoing facility assessments for Baby‐Friendly designation.

Table 2.

Components of the BFHI training package and use for application

| Document | Objectives and application for Malawi | Target group |

|---|---|---|

| Strengthening and sustaining the Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative: A Course for Decision‐Makers (Malawi Ministry of Health, 2016b) | The adapted course provides guidance for decision makers on how they can support health facilities to institutionalize BFHI into routine systems and obtain baby‐friendly designation. | Hospital decisions‐makers (directors, administrators, key managers, etc.) and policymakers. |

| Breastfeeding Promotion and Support in a Baby‐Friendly Hospital: A 20‐hour Course for Maternity Staff (Malawi Ministry of Health, 2016a) | Within BFHI in Malawi, it is intended that every hospital staff member who has direct patient care with mothers and babies will attend the course to strengthen knowledge and skills towards successful implementation of the Ten Steps. The short‐term course objectives are (a) to help equip the hospital staff with the knowledge and skills to transform their health facilities into baby‐friendly institutions though implementation of the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding and (b) to sustain policy and practical changes at the health facility level. | Clinical and nonclinical health facility staff |

| Hospital Self‐Appraisal and Monitoring Tools (Malawi Ministry of Health, 2016c) | These tools provided guidance to managers and health facility staff in Malawi for monitoring their facility's adherence to the Ten Steps and confirming readiness for external assessment. Once facilities are designated as Baby‐Friendly, these tools serve to monitor continued adherence to the Ten Steps. | Managers, clinical and nonclinical health facility staff |

| External Assessment and Reassessment Package | A package of guidelines and tools to assess whether hospitals and health facilities meet the global criteria and, thus, fully comply with the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding. The package was applied in Malawi to provide guidance around assessing and reassessment a facility for Baby‐Friendly certification. | Managers, clinical and nonclinical health facility staff, external assessors |

| The National Breastfeeding Policy (2013) | The National Breastfeeding Policy was also assessed and revised as part of the BFCI revitalization process. The new policy provided up to date guidance on PMTCT, WHO breastfeeding guidelines, and the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes. | Stakeholders and policymakers |

3.3. Assessing the status of BFHI prior to roll‐out

To ascertain the status of BFHI in Malawi and to better understand challenges health providers faced with supporting recommended breastfeeding practices, MCSP performed a rapid health facility assessment at 18 public hospitals to undergo BFHI training, some of which were designated as Baby‐Friendly from 1993 to 2004. These rapid assessments were performed while utilizing the WHO Hospital External Assessment Tool (WHO & UNICEF, 2009c). Findings revealed that facility‐based health providers had no IYCF training, were beyond preservice training on the basics of breastfeeding, or had not received an in‐service training update in many years. Through observations and discussions, it was found that lack of training on breastfeeding prevented health providers from being adequately equipped to provide mothers support and counselling on early initiation of breastfeeding < 1 hr after birth and EBF for the first 6 months of life.

Common barriers to recommended breastfeeding practices noted from during the rapid assessment included

poor positioning and attachment,

difficulties with initiation of breastfeeding within 1 hr of birth,

water and other fluids are often given in the first months of life, due to the belief that “the baby is thirsty” and/or “the mother's breast milk is insufficient,”

phala ufawoyera (watery refined porridge) is often given when the infant is 3–4 months of age, due to cultural tradition, and

belief that when a baby cries it is from hunger, often because of thinking the mother's breast milk is insufficient.

These identified breastfeeding challenges were addressed intensively during both BFHI provider trainings and counselling sessions with mothers and caretakers.

3.4. Leveraging the existing pool of BFHI master trainers to build a new pool of master trainers

The original 25 master trainers underwent a 5‐day training of trainers on the revised BFHI training package from May to June 2016, utilizing the updated BFHI 20‐hr course (Malawi MOH, 2016a). In July 2017, the MOH with MCSP and the original BFHI master trainers built the capacity of a group of 30 new BFHI master trainers, who were primarily nutritionists and nurse midwives, selected by MOH for their expertise in infant feeding and/or involvement in previous BFHI efforts in‐country.

3.5. Orienting district‐level leadership to BFHI

MCSP and the MOH oriented all DHMT (n = 118) members from all districts across Malawi on BFHI from May 2016 to September 2017. DHMTs oversee health services in their district, and the orientation was a way of garnering their support to have facilities trained on BFHI. The two‐day orientations used the Strengthening and Sustaining the Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative: A Course for Decision‐Makers (WHO & UNICEF, 2009a) to discuss how BFHI would be implemented in targeted health facilities, and the expected role of the DHMTs.

3.6. Training health facility staff on the Ten Steps

A minimum of 20% of each facility's maternity ward clinical staff were trained on‐site by master trainers using the 20‐hr course. This proportion was chosen with the expectation that trained staff would provide mentorship and on‐the‐job training to their colleagues who did not undergo the training. First, 1,310 staff were trained in 18 hospitals from August to September 2016. At each of these hospitals, between 30 and 60 clinical (i.e., physicians, nurse midwives, nurses, and clinicians) and support staff (i.e., patient attendants, security guards, and cleaners) from the maternity ward were trained. In August 2017, 630 clinical staff at 36 hospitals were trained. In total, 1,330 clinical and 610 support staff were trained across the 54 hospitals.

3.7. BFHI Task Force for monitoring progress on implementing the Ten Steps

During the trainings, a BFHI Task Force at each hospital was established. The BFHI Task Force is composed of maternity ward staff who hold regular meetings for planning, implementation, and monitoring of BFHI activities as well as mentoring to maternity ward staff on BFHI. It is led by the BFHI Coordinator, who is responsible for spearheading and supervising the process of obtaining and maintaining Baby‐Friendly designation. The BFHI Coordinator for each facility was usually a nurse midwife at that facility and was selected by the MOH following BFHI trainings.

3.8. Mentoring and supportive supervision of BFHI

MOH and MCSP worked with facilities trained in BFHI to observe their progress in implementation of the Ten Steps, utilizing the WHO Hospital Self‐Appraisal and Monitoring Tool (WHO & UNICEF, 2009c). Mentoring and supportive supervision were tailored to the needs of each facility and focused on the steps requiring additional attention. Two‐day facility visits aided each facility to make progress in obtaining Baby‐Friendly designation. At the end of these visits, the MOH and MCSP met with the BFHI Task Force at each facility to discuss the findings from their visit, including areas needing further attention for improving breastfeeding practices.

3.9. Engaging community leadership in BFHI

Each district is composed of multiple ADCs, which aid in the development work within their community. They are led by the Traditional Authority and also include local village heads and volunteers for any key community‐based organizations operating in that catchment area. ADC members of eight districts that are prone to natural disasters, and are thus eligible for food and nutrition assistance, were oriented over a 2‐day period in June 2017 on BFHI. These orientations covered the Ten Steps, promoting the importance of early and EBF within their communities, and potential harms of BMS and preventing them in their communities, unless medically indicated. The ADC members, 352 oriented in total, were informed of the facilities within their district that had or would be undergoing BFHI training. They were also tasked with acting as gatekeepers—meaning they were assigned with educating their communities on avoiding BMS and promoting early and EBF to 6 months of age. ADCs had a key role in protecting adherence to the International Code of Marketing of Breast‐milk Substitutes (the Code) (WHO, 1981) by speaking with organizations that distribute BMS about not donating to mothers within their communities and instead giving these products to orphanages, where breastfeeding is not feasible given the babies at these facilities are without parents.

3.10. Self and external assessments for Baby‐Friendly certification

The BFHI Task Force, according to the global BFHI implementation guidelines (WHO & UNICEF, 2009b), is responsible for internal monitoring of its facility's BFHI activities and is expected to conduct regular self‐assessments, to evaluate its facility's adherence to the Ten Steps, using the WHO Hospital Self‐Appraisal and Monitoring Tool (WHO & UNICEF, 2009c). External assessment was conducted by BFHI master trainers through observing the hospital's compliance to the Ten Steps using the WHO Hospital External Assessment Tool (WHO & UNICEF, 2009c) and conducting interviews with mothers who received maternity care at that BFHI‐trained facility. After results of the assessment were provided to the BFHI Task Force and for MOH review by external assessors, MCSP supported the MOH in organizing a facility‐level ceremony for Baby‐Friendly designation. The MOH, with the support of MCSP, designated three health facilities as Baby‐Friendly in August 2017. In addition to these three facilities, two facilities underwent successful external assessments and are awaiting Baby‐Friendly designation with a ceremony to be led by the MOH.

To maintain Baby‐Friendly designation, the MOH is responsible for conducting a reassessment at each Baby‐Friendly facility every 6 months. This reassessment process mimics that of the external assessment performed to obtain the certification. No reassessments were performed under MCSP given it had not yet been 6 months since the time of Baby‐Friendly designation by the close of the programme.

3.11. Integration of BFHI and other health areas

MCSP worked to integrate breastfeeding promotion into other health areas, with these efforts extending beyond the facility and into the community. As part of its integrated health efforts, MCSP developed an immunization‐nutrition initiative and trained village heads, community volunteers, and HSAs engaged in MCSP‐supported immunization‐tracking activities in Dowa district from February to March 2017 to promote breastfeeding. Community volunteers and village heads were supervised by HSAs in their community, who were trained to provide supervision and support to these cadres under MCSP. Specifically, the village heads were trained to act as BFHI champions in their communities through discussing with mothers the harms of providing BMS or other foods or liquids before the age of 6 months if they were seen within their community to not be exclusively breastfeeding. The community volunteers were trained to promote early and EBF and provide counselling and support for mothers experiencing breastfeeding challenges within community care groups (CCGs; Perry et al., 2015). These CCGs were engaged by MCSP under immunization activities, through which these BFHI‐related messages were integrated during routine immunization visits.

In an effort to strengthen newborn care into BFHI, MCSP provided training on care and feeding for the small and sick newborn, utilizing Essential Care for Small Babies, Provider Guide (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2014). Focusing on eight hospitals previously trained on BFHI under MCSP, this training was given to clinical maternity ward staff and provided education as well as hands‐on demonstrations on the following topics: skin‐to‐skin care, hand expressing breast milk, providing cup feeds, providing breast milk via nasogastric feeds, and providing general clinical care to the sick and/or small newborn. As a result of this integrated training, 112 clinical maternity ward staff—including nurses, midwives, clinicians, and nurse midwives—were trained on care and feeding of the small and sick newborn.

3.12. Advocacy

Midway through implementation of the BFHI revitalization, the MOH, MCSP, and WHO held Malawi's first‐ever BFHI Stakeholders' Workshop during World Breastfeeding Week in August 2017. Key stakeholders were brought together, including from UNICEF, MCSP, USAID, relevant breastfeeding and IYCF partners, and other key governmental and non‐governmental partners. More than 200 policymakers, managers, and nutrition partners from the national and district levels were brought together to discuss BFHI progress from the past and review midcourse gains and lessons during MCSP, including BFHI monitoring data, gaps in institutionalizing BFHI in Malawi, and successes and challenge with BFHI in Malawi. Key action points for institutionalizing BFHI in Malawi were developed, with stakeholders pledging to move forward in three areas to allow for the success of the initiative:

Strengthening the integration of BFHI indicators, including EBF to 6 months of age, into the Health Management Information System to better monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of BFHI in Malawi in improving breastfeeding practices.

Integrating BFHI in routine systems, the continuum of care, and quality improvement mechanisms and strengthen advocacy with parliament and at all levels.

Incorporating financing for BFHI into district and health facility annual budgets and work plans.

3.13. Successes and challenges with implementing the Ten Steps

Challenges with implementation of the Ten Steps and how they were overcome as well as successes are demonstrated in Table 3. These were ascertained through ongoing discussions throughout the programme with key health facility and programme staff during mentoring and supportive supervision visits.

Table 3.

Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding—Successes and challenges

| Step | Successes | Challenges | How these challenges were overcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Have a written breastfeeding policy that is routinely communicated to all health care staff. |

|

|

|

| 2. Train all health care staff in skills necessary to implement this policy. |

|

|

|

| 3. Inform all pregnant women about the benefits and management of breastfeeding. |

|

|

|

| 4. Help mothers initiate breastfeeding within 0.5 hr of birth. |

|

|

|

| 5. Show mothers how to breastfeed, and how to maintain lactation even if they should be separated from their infants. |

|

|

|

| 6. Give newborn infants no food or drink other than breast milk unless medically indicated. |

|

|

|

| 7. Practise rooming in—allow mothers and infants to remain together—24 hr a day. |

|

|

|

| 8. Encourage breastfeeding on demand. |

|

|

|

| 9. Give no artificial teats or pacifiers (also called dummies or soothers) to breastfeeding infants. |

|

|

|

| 10. Foster the establishment of breastfeeding support groups and refer mothers to them on discharge from the hospital or clinic. |

|

|

|

3.14. Monitoring of BFHI indicators

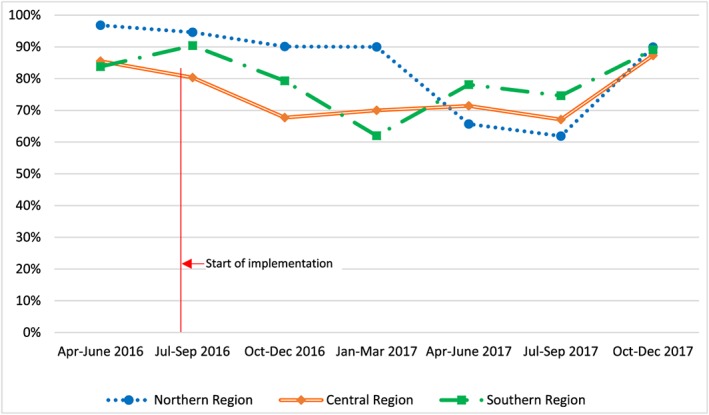

While this programme was not able to carry out an impact evaluation to determine the effects the programme had on breastfeeding outcomes, due to the limited time frame of the programme, routine DHIS 2 data were tracked through the Malawi health system. Figure 4 illustrates the trends for early initiation of breastfeeding < 1 hr after birth from preimplementation to postimplementation for the 18 hospitals included in the initial implementation efforts from August 2016 to December 2017, shown by the three regions of Malawi. In the Central and Southern regions, the early initiation rates increased from 85.5% to 87.3% and from 83.8% to 89.1%, respectively, from April 2016 to December 2017. In the Northern region, this rate dropped 96.8% to 89.9%. Given these data are routine MOH data that do not control for other contributing factors, we are unable to provide attribution directly to the programme on these rates. We do note that intensive efforts on BFHI did take place in these areas, which may have contributed to these increased rates.

Figure 4.

Early initiation of breastfeeding < 1 hr after birth before and after BFHI implementation, by region of Malawi

4. DISCUSSION

Using a programmatic lens, we describe the process and results of the scale‐up of BFHI within the context of a global integrated health project. Though routine data did show improvements in early initiation of breastfeeding in two regions of Malawi—a 2.1% increase in the Central region and 6.3% increase in the Southern region—we did not control for other factors and are unable to state whether these improvements were due to our programme. These increases were shown across 18 hospitals trained on BFHI from August 2016 to December 2017. The capacity of 1,940 health facility staff at 54 facilities was developed in breastfeeding knowledge and skills, resulting in greater than 80,000 women receiving counselling on EBF prior to discharge from the hospital following childbirth. Moreover, 352 ADCs, 118 DHMTs, and 205 national stakeholders were oriented on BFHI, building their knowledge in BFHI and the importance of breastfeeding and leading to increased support from leaders at the community, district, and national levels. The MOH with MCSP designated three hospitals as Baby‐Friendly in August 2017. In addition, two hospitals underwent successful external assessments and are awaiting Baby‐Friendly designation, with a ceremony to be led by the MOH.

Although these indicators are not systematically tracked in Malawi's health system, adherence to the Ten Steps is well documented to have a positive impact on EBF < 6 months of age and continued breastfeeding in several settings. The study by Sinha et al. evaluating the effects of the Ten Steps on breastfeeding practices demonstrated clearly that adherence to the Ten Steps resulted in dramatic and significant increases in EBF < 6 months, continued breastfeeding, and any breastfeeding: EBF increased by 44%; continued breastfeeding up to 23 months increased by 63%; and any breastfeeding increased by 30% (Sinha et al., 2015). This is reinforced by data from other countries. A cluster randomized‐controlled study conducted in the Democratic Republic of the Congo that evaluated the effects of attending antenatal care (ANC) visits and giving birth in a health facility following implementation of BFHI's Steps 1–9 of the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding versus a facility that had not implemented any of the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding showed promising results for EBF. At 14 weeks, EBF prevalence was 2.24 times higher in the study group implementing than in the control group (65% vs. 29%) and 3.0 times higher at 6 months (36% vs. 12%; Yotebieng et al., 2015).

In Malawi, where 91% of births take place in a health facility and 95% of women receive ANC (National Statistical Office Malawi & ICF Macro, 2017), our programme experience reveals that BFHI builds upon existing platforms through which to promote and support early and EBF. Despite the key successes of BFHI, sustaining these efforts at the community level, as outlined in the 10th step, remains a challenge. In Malawi, MCSP and the MOH linked with CCGs and trained community volunteers on BFHI to improve community support, as a part of immunization‐nutrition integration activities in one MCSP‐supported area. In other programme areas, health facilities provided mothers with contact information upon discharge from the hospital after childbirth for a community health worker, community nutritionist, or nurse midwife in their community to speak with if they had questions regarding breastfeeding at home. An impact evaluation following BFHI implementation in maternity wards in Brazil showed positive effects on EBF during the first 48 hr after birth, but no effects were seen on EBF at 6 months (Coutinho, De, Lima, Ashworth, & Lira, 2005). The study in Croatia following the national revitalization of the initiative, which demonstrated improvements in EBF in the hospital, showed BFHI had no effect on EBF rates at 3, 6, or 12 months following birth, further driving home the need for strong community support structures (Zakarija‐Grković et al., 2017). There were several key factors for BFHI's success in its second iteration in Malawi. MCSP worked closely with and built the capacity of local leadership as well as MOH at the national and district levels, who led the process, with MCSP taking a supporting role. This aided in the government harnessing ownership of BFHI, enhancing its chances for sustainability.

Additionally, with capacity building of and support from community leaders, including village heads, BFHI improved linkages of care from the hospital to community level. This helped strengthen Step 10, which is key to the success of BFHI (Kavle et al., 2018). Evidence has shown that, without proper support at the community level, improvements in breastfeeding are limited. Another major success was the revising of country‐level BFHI documents to include updated content around PMTCT (WHO, 2010b). Given the confusion that had existed around infant feeding in HIV‐infected mothers prior to the revitalization efforts, these updates to training and BCC materials worked to ensure consistent messaging around this topic.

4.1. Challenges and limitations

Malawi faces understaffing at health facilities and a lack of financial resources (Bradley et al., 2015). The MOH and MCSP addressed this issue through task shifting from clinical to support staff of key BFHI‐related responsibilities—including breastfeeding counselling to mothers and monitoring maternity wards to ensure BMS and artificial nipples were not brought into the facility. This aided in ensuring adherence to the Ten Steps. A limitation of this is that although support staff were included in the trainings of the 18 hospitals trained from August to September 2016, they were not included in the 36 hospitals trained in August 2017. This was due to waning funds given MCSP activities were nearing close‐out in Malawi. Furthermore, mentoring and supportive supervision were not provided by the MOH and MCSP to the 36 hospitals trained in August 2017, with the expectation that implementing partners working in the catchment area of these facilities would provide support to the facilities following the close‐out of MCSP in the country.

Despite the key successes of BFHI, sustaining these efforts at the community level, as outlined in the 10th step, remains a challenge. In Malawi, MCSP and the MOH linked with CCGs and trained community volunteers on BFHI to improve community support, as a part of immunization‐nutrition integration activities, in one MCSP‐supported area. A randomized‐controlled trial in Malawi evaluating the effects of women's groups and volunteer peer counselling demonstrated the importance of these community structures in improving breastfeeding outcomes (Lewycka et al., 2013). This study showed that women randomized to the women's group with peer health counselling that included breastfeeding promotion and support were at a 2.44 (95% CI [1.49, 3.99]) higher adjusted odds than were those in the control group.

Many districts in Malawi, however, do not have existing community support group structures, such as CCGs, making it difficult to adequately implement Step 10. In programme areas without these structures, health facilities provided mothers with contact information upon discharge from the hospital after childbirth for a community health worker, community nutritionist, or nurse midwife trained on BFHI in their community to speak with if they had questions regarding breastfeeding at home. Although this mechanism ensured that mothers had a resource on breastfeeding in the community, it did not provide ongoing breastfeeding counselling and support. Moreover, though MCSP and the MOH built linkages from the facility to community intensively in Dowa district through engaging CCGs and in other districts through engaging village heads and HSAs, the amount of communities reached and/or volunteers was not tracked.

Although improvements in early initiation of breastfeeding were observed in the Central and Southern regions (Figure 4), numerous challenges exist with the quality of DHIS 2 data in Malawi. First, per protocol, early initiation of breastfeeding data is to be entered into the maternity register by the nurse midwife caring for the mother at time of delivery. However, maternity wards in Malawi are chronically overburdened and under‐resourced nurse midwives are often challenged with immediately tending to another birth after one mother has given birth (Bradley et al., 2015). Because of this, data often do not get entered in the maternity register at all or it gets entered incorrectly. This lack of time for data entry that maternity ward staff often face means that data clerks under the MOH often enter these data into the maternity registers. This is problematic given that data clerks are not the ones providing care to mothers and are unable to accurately report the care provided to mothers. It was outside the scope of this programme's resources and activities to train the data clerks on data management, though this is an area for improvement in the future. Another challenge is that early initiation of breastfeeding data requires manual data entry from the maternity registers into DHIS 2. This added step for data entry brings another vulnerability for errors to be made in the data.

Implemented as part of an integrated health programme, the revitalization and scale‐up of BFHI was strengthened by its ability to integrate into other health areas under MCSP, including newborn care, immunization, and family planning at the health facility and community levels. A weakness of these integration activities is the lack of data around how outcomes in nutrition integrated into other health areas were improved through the programme. However, we showed that BFHI messaging can be successfully integrated into other health areas.

4.2. Lessons learned

In the context of the revised BFHI implementation guidance released by WHO and UNICEF in 2018, which outlines key considerations for ensuring the sustainability of country‐level BFHI platforms (WHO & UNICEF, 2018), key actions must be taken to ensure the long‐term success of BFHI in Malawi. BFHI must be integrated into Malawi's standards of practice; breastfeeding and maternal, infant, and child health and nutrition policies and guidelines; and training protocols to improve compliance and attitudes towards the initiative. This should include budgetary commitments by the MOH and donor organizations to include routine financing in the national budget for BFHI, but with the expectation that MOH grows its financial commitments to BFHI over time. In addition, training on BFHI should be a part of preservice training in medical, nursing, and midwifery schools to ensure that BFHI is integrated into the routine training of clinical staff.

To better monitor and evaluate BFHI in relation to breastfeeding indicators, improving data availability and quality is vital. During preservice and in‐service training of health facility providers, additional guidance regarding data entry, data use, and data for decision making, with ongoing mentorship on data quality management and interpretation, is warranted (UNICEF & WHO, 2017). Further, although early initiation of breastfeeding is tracked in the health system, EBF from 0 to 5 months of age is not included as an MOH‐tracked indicator, which should be regularly monitored as part of BFHI roll‐out.

4.3. The future of BFHI in Malawi

In the future, incorporation of the updated WHO/UNICEF BFHI implementation guidance into Malawi's BFHI guidelines and training package is a critical next step to harmonizing global and country guidelines and materials (WHO & UNICEF, 2018). BFHI should be expanded throughout all facilities providing maternity care in Malawi, which is supported by the MOH. It is necessary to institutionalize the initiative through the integration of BFHI into preservice training curricula for health providers, standards of practice, protocols, clinical policies and guidelines, MOH budgeting for nutrition, and coordination of BFHI activities with other breastfeeding promotion initiatives. To further scale‐up BFHI, an increased focus on providing support to women at the community level is important (Coutinho et al., 2005). Despite most mothers in Malawi receiving ANC (National Statistical Office Malawi & ICF Macro, 2017), long distances to health facilities affect the number of times a woman is exposed to breastfeeding counselling during ANC visits, a critical time point for facilitating EBF (Kavle, LaCroix, Dau, & Engmann, 2017; MCSP, 2018b; WHO, 2016). Improving community support through CCGs would serve to create better linkages between the facility and community to support the continuum of care (Perry et al., 2015).

While breastfeeding is clearly a priority for Malawi, strengthening of its legislation around the Code is needed. Marketing of BMS leads to higher rates of bottle feeding and negatively affects breastfeeding rates (Alfaleh, 2014; Phoutthakeo et al., 2013; Yee & Chin, 2007). Enhanced legislation and enforcement of the Code will be critical to maintaining an environment that promotes and protects breastfeeding (WHO, 1981). With the incorporation of full compliance with the Code as a component of Step 1 in the revised BFHI Implementation Guidance (WHO & UNICEF, 2018), improved legislation in Malawi will be necessary for obtaining and maintaining Baby‐Friendly certification. In 2004, Malawi last enacted legislation that includes regulation of marketing of infant formula, pacifiers, feeding bottles, and teats (WHO, UNICEF, & IBFAN, 2016). Yet, to date, Malawi does not have a formal mechanism in place to monitor and enforce compliance with the Code, limiting its ability to detect violators and take relevant actions (WHO, UNICEF, & IBFAN, 2016). The NetCode Toolkit, developed by the WHO and UNICEF, provides a set of protocols that could be utilized by Malawi to assist with putting in place a monitoring system to enforce its legislation around the Code (WHO & UNICEF, 2017).

To ensure sustainability for BFHI in Malawi, continued advocacy with the MOH, donor agencies, professional associations, TWGs, and other partners is necessary. In Malawi, external funding accounts for 74% of all health expenditures. Diversification of funding sources and partnerships for BFHI to ensure continued funding, with increasing government commitments, will be necessary to ensure the sustainability of BFHI in Malawi.

In order to monitor the country's achievements and strengthen future roll‐out of interventions for improved breastfeeding promotion and support, it is essential that Malawi routinely track its progress in the scale‐up of BFHI. The World Breastfeeding Trends Index and the Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly Index are two evidence‐based tools that can assist countries with assessing their progress in breastfeeding interventions (IBFAN, 2018; Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2018).

5. CONCLUSION

This paper supports the global evidence that the BFHI positively impacts early initiation of breastfeeding. It also provides a programmatic case study for “how” BFHI can be implemented within the health system and suggests opportunities for integrating with other health areas. Additionally, it underscores challenges with scaling‐up BFHI and ensuring its sustainability. To achieve full integration of BFHI into the health system, improved data monitoring and quality, inclusion of BFHI in preservice training for health providers, improved financial investments, and expansion of CCGs and other community volunteer structures to improve breastfeeding support at the community level are of critical importance.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. Although USAID provided reviews of the content in this article, authors had intellectual freedom to incorporate feedback, as needed.

CONTRIBUTIONS

JAK and PRW conceptualized and led the writing of the paper. FB, KN, JG, NM, SS, and SK were involved in writing of paper. All authors were involved in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

FUNDING

This publication is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the US Agency for International Development (USAID), under the terms of cooperative agreement number AID‐OAA‐A‐14‐00028. The contents are the responsibility of the MCSP and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Albertha Nyaku for her technical assistance to support implementation of BFHI in Malawi.

Kavle JA, Welch PR, Bwanali F, et al. The revitalization and scale‐up of the Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative in Malawi. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15(S1):e12724 10.1111/mcn.12724

Footnotes

A centre‐of‐excellence hospital in Malawi is defined as a lower tier hospital that exists in a community setting but that has high volumes of patients and adheres to national standards and clinical care guidelines.

DHIS 2 is an open‐source platform for reporting and monitoring data from health programmes.

A CCG is composed of community‐based volunteers, typically 10–15, who receive supervision and are responsible for educating their neighbours on a particular behaviour. Each volunteer within the CCG is responsible for regularly visiting 10–15 neighbouring households, which can create a multiplying effect for reaching beneficiaries within the community.

REFERENCES

- Alfaleh, K. (2014). Perception and knowledge of breast feeding among females in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 9(2), 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics (2014). Helping Babies Survive Essential Care for Every Baby: Provider Guide (pp. 1–68). Washington: American Academy of Pediatrics. [Google Scholar]

- Aryeetey, R. , & Dykes, F. (2018). Global implications of the new WHO and UNICEF implementation guidance on the revised Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative . Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14(3), e12637 10.1111/mcn.12637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowatte, G. , Tham, R. , Allen, K. , Tan, D. , Lau, M. , Dai, X. , & Lodge, C. (2015). Breastfeeding and childhood acute otitis media: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatrica, International Journal of Paediatrics, 104, 85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, S. , Kamwendo, F. , Chipeta, E. , Chimwaza, W. , de Pinho, H. , & McAuliffe, E. (2015). Too few staff, too many patients: A qualitative study of the impact on obstetric care providers and on quality of care in Malawi. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15(65), 65 10.1186/s12884-015-0492-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinkonde, J. , Hem, M. , & Sundby, J. (2012). HIV and infant feeding in Malawi: Public health simplicity in complex social and cultural contexts. BMC Public Health, 12(700). 10.1186/1471-2458-12-700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho, S. , De, M. , Lima, C. , Ashworth, A. , & Lira, P. (2005). The impact of training based on the Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative on breastfeeding practices in the Northeast of Brazil. Jornal de Pediatria, 81(6), 471–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott, J. , Alderman, H. , Behrman, J. , Haddad, L. , & Horton, S. (2013). The economic rationale for investing in stunting reduction. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 9(2), 69–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horta, B. , Loret De Mola, C. , & Victora, C. (2015). Long‐term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatrica, 104, 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horta, B. , & Victora, C. (2013). Short‐term effects of breastfeeding: a systematic review on the benefits of breastfeeding on diarrhoea and pneumonia mortality. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- International Baby Food Action Network . (2018). The Guide Book World Breastfeeding Trends Index.

- Kavle, J. A. , Ahoya, B. , Kiige, L. , Mwando, R. , Olwenyi, F. , Straubinger, S. , & Mkiwa, C. Submitted for publication September(2018). Baby Friendly Community Initiative –From National Guidelines to Implementation: A multi‐sectoral platform for improving infant and young child feeding practices and integrated health services in Kenya. Maternal & Child Nutrition. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavle, J. A. , LaCroix, E. , Dau, H. , & Engmann, C. (2017). Addressing barriers to exclusive breast‐feeding in low‐ and middle‐income countries: a systematic review and programmatic implications. Public Health Nutrition, 20(17), 3120–3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M. , Aboud, F. , Mironova, E. , Vanilovich, I. , Platt, R. , Matush, L. , … Shapiro, S. (2008). Breastfeeding and Child Cognitive Development New Evidence From a Large Randomized Trial for the Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT) Study Group. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(5), 578–584. 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbok, M. (2012). Global Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative Monitoring Data: Update and Discussion. Breastfeeding Medicine, 7(4), 210–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewycka, S. , Mwansambo, C. , Rosato, M. , Kazembe, P. , Phiri, T. , Mganga, A. , … Costello, A. (2013). Effect of women's groups and volunteer peer counselling on rates of mortality, morbidity, and health behaviours in mothers and children in rural Malawi (MaiMwana): A factorial, cluster‐randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 381, 1721–1735. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61959-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malawi Ministry of Health (2013). Malawi Child Health Strategy: For survival and health development of under‐five children in Malawi 2014–2020. Lilongwe: Malawi Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Malawi Ministry of Health (2016a). Malawi Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative: Revised, Updated,and Expanded for Integrated Care—Breastfeeding Promotion and Support in a Baby‐Friendly Hospital, a 20‐Hour Course. Lilongwe: Malawi Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Malawi Ministry of Health (2016b). Malawi Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative: Section 2: Strengthening and sustaining the Baby‐friendly Hospital Initiative: A course for decision‐makers. Lilongwe: Malawi Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Malawi Ministry of Health (2016c). Malawi Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative: Section 4: Hospital Self‐Appraisal and Monitoring. Lilongwe: Malawi Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Malawi Ministry of Health (2016d). Malawi National Nutrition Policy 2016–2020. Lilongwe: Malawi Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Malawi National AIDS Commission (2014). National Strategic Plan for HIV and AIDS 2015–2020. Lilongwe: Malawi National AIDS Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Maternal and Child Survival Program . (2018a). USAID's Flagship Maternal and Child Survival Program Retrieved from https://www.mcsprogram.org/.

- Maternal and Child Survival Program . (2018b). Maternal Nutrition Programming in the context of the 2016 WHO Antenatal Care Guidelines: For a positive pregnancy experience. Retrieved from https://www.mcsprogram.org

- National Statistical Office Malawi , & ICF Macro (2017). Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2015–16. Zomba: National Statistical Office Malawi and ICF Macro. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Office Malawi , & IFC Macro (2011). Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Zomba: National Statistical Office, Malawi and Macro International. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Office Malawi , & Macro International (1994). Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 1992. Zomba: National Statistical Office, Malawi and Macro International. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Office Malawi , & ORC Macro (2001). Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2000. Zomba: National Statistical Office, Malawi and ORC Macro. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez‐Escamilla, R. , Hromi‐Fiedler, A. J. , Bauermann, G. M. , Doucet, K. , Meyers, S. , & dos Santos Buccini, G. (2018). Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly Index: Development and action for scaling‐up breastfeeding programmes globally. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14, e122596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez‐Escamilla, R. , Martinez, J. , & Segura‐Pérez, S. (2016). Impact of the Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative on breastfeeding and child health outcomes: a systematic review. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 12, 402–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry, H. , Morrow, M. , Borger, S. , Weiss, J. , Decoster, M. , Davis, T. , & Ernst, P. (2015). Care Groups I: An Innovative Community‐Based Strategy for Improving Maternal, Neonatal, and Child Health in Resource‐Constrained Settings. Global Health: Science and Practice, 3(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phoutthakeo, P. , Otsuka, K. , Ito, C. , Sayamoungkhoun, P. , Kounnavong, S. , & Jimba, M. (2013). Cross‐border promotion of formula milk in Lao People's Democratic Republic. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 50(1), 51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins, N. , Bhandari, N. , Hajeebhoy, N. , Horton, S. , Lutter, C. , Martines, J. , … Victora, C. (2016). Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? The Lancet, 387, 491–504. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankar, M. , Sinha, B. , Chowdhury, R. , Bhandari, N. , Taneja, S. , Martines, J. , & Bahl, R. (2015). Optimal breastfeeding practices and infant and child mortality: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatrica, International Journal of Paediatrics, 104(476), 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekar, M. , Kakietek, J. , Eberwein, J. , & Walters, D. (2017). An investment framework for nutrition: Reaching the global targets for stunting, anemia, breastfeeding, and wasting. Washington: World Bank Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, B. , Chowdhury, R. , Sankar, M. , Martines, J. , Taneja, S. , Mazumder, S. , … Bhandari, N. (2015). Interventions to improve breastfeeding outcomes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatrica, 104, 114–134. 10.1111/apa.13127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF , & World Health Organization (2017). Country experiences with the Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative: Compendium of case studies of the Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative. New York: UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C. , Bahl, R. , Barros, A. , França, G. , Horton, S. , Krasevec, J. , … Richter, L. (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet, 387, 475–490. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (1981). International Code of Marketing of Breast‐milk Substitutes. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (1998). Evidence for the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2010a). Breast is always best, even for HIV‐positive mothers. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 88(1), 1–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2010b). HIV and infant feeding: Guidelines on Principles and recommendations for infant feeding in the context of HIV and a summary of evidence. Geneva: World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2016). WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Geneva: World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2017). National Implementation of the Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization , & UNICEF (2009a). Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative: Revised, Updated and Expanded for Integrated Care. Geneva: World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization , & UNICEF (2009b). Section 1: Background and Implementation In World Health Organization, UNICEF, World Health Organization, & UNICEF (Eds.). In Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative ‐ Revised, Updated and Expanded for Integrated Care. Geneva: World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization , & UNICEF (2009c). Section 4: Hospital self‐appraisal and monitoring In World Health Organization, & UNICEF. In Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative: Revised, updated and expanded for integrated care. Geneva: World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization , & UNICEF (2014). Global nutrition targets 2025: breastfeeding policy brief (WHO/NMH/NHD/14.7). Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization , & UNICEF (2017). Netcode toolkit: Monitoring the marketing of breast‐milk substitutes: protocol for periodic assessment. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization , & UNICEF (2018). Implementation guidance: protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services—the revised Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization , UNICEF , & IBFAN (2016, 2016). Marketing of Breast‐milk Substitutes: National Implementation of the International Code: Status Report. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Yee, C. , & Chin, R. (2007). Parental perception and attitudes on infant feeding practices and baby milk formula in East Malaysia. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 31, 363–370. [Google Scholar]

- Yotebieng, M. , Labbok, M. , Soeters, H. , Chalachala, J. , Lapika, B. , Vitta, B. , & Behets, F. (2015). Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding programme to promote early initiation and exclusive breastfeeding in DR Congo: A cluster‐randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 3(9), 546–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakarija‐Grković, I. , Boban, M. , Janković, S. , Ćuže, A. , & Burmaz, T. (2017). Compliance With WHO/UNICEF BFHI Standards in Croatia After Implementation of the BFHI. Journal of Human Lactation, 34(1), 106–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]