Abstract

Background and Aims

Previous studies have found that in some countries ‘drinking pace’ (number of drinks consumed per hour) increases during the course of an evening. We aimed to provide evidence of this acceleration from a culture in which binge drinking is prevalent and to test whether this is consistent across gender, day of week and in high‐risk drinkers.

Design

Event‐level data collected on Thursday, Friday and Saturday evenings over 5 consecutive weeks.

Setting

The Netherlands.

Participants

A total of 197 young adult frequent drinkers (48.7% women, mean age = 20.8).

Measurements

High‐risk drinking (assessed by the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test) and gender were measured at baseline, and questionnaires were sent to participants’ smartphones every hour between 9 p.m. and 1 a.m. A total of 7185 questionnaires during 1589 evenings were used for the analyses.

Findings

Multi‐level latent growth curve models revealed an acceleration in drinking on days of the week tested [throughout all evenings; b = 0.430, standard error (SE) = 0.045, P < 0.001], which stabilized as the evening progressed (b = −0.072, SE = 0.008, P < 0.001). The temporal pattern did not differ between the days or gender, but men started with a higher number of drinks at the beginning of the evening (b = 0.465, SE = 0.099, P < 0.001). High‐risk drinking was related to more alcoholic drinks at the beginning of an evening (b = 0.032, SE = 0.011, P = 0.003) and a steeper acceleration during the subsequent hours (b = 0.021, SE = 0.009, P = 0.024).

Conclusions

Young adults in the Netherlands appear to show an increase in drinking pace during the course of an evening's drinking, with high‐risk drinkers showing a greater increase.

Keywords: Acceleration, alcohol use, binge drinking, event‐level, weekend drinking, young adults

Introduction

Heavy drinking occurs most often at the weekend, when individuals have no responsibilities the next day 1. Consuming large amounts of alcohol in a short period of time, also called binge drinking, can lead to substantial adverse consequences such as accidents, injuries and unwanted and unprotected sexual encounters 2.

Contemporary assessment techniques enable researchers to gather event‐level data, minimizing recall bias and capturing consumption patterns over (short periods of) time. Using such a method, previous studies in Switzerland revealed an acceleration of drinking during the course of the evening; that is, an increasing number of alcoholic drinks consumed per hour 3, 4, 5. Moreover, the studies revealed that this increasing drinking pace stabilized somewhat, i.e. there was a ceiling effect after about 11 p.m. Differences were found according to gender; that is, men increased their drinking rate more quickly than women, and accelerated drinking occurred on Saturday evenings rather than Thursday or Friday evenings.

The aim of the current study was to investigate whether this acceleration of drinking is a robust phenomenon and can also be found among frequent drinkers in a country with a different drinking culture and alcohol policy. The Netherlands is one of the European countries with a high prevalence of binge drinking 6 and which experienced an increasing percentage of young adult (15+ years) binge‐drinkers between 2010 and 2016 7. Compared to Switzerland, young adults aged between 15 and 19 years show more heavy episodic drinking, while legal age limits for beer and wine are 18 years in the Netherlands instead of 16 years in Switzerland 7. Given that heavy drinking common in this country we expect that acceleration is also common, i.e. consistent across gender and days. We aimed to test (1) whether there is an acceleration in the drinking pace during the evening (i.e. an increase in the drinks consumed per hour, similar to 3, 4); (2); whether there is a ceiling effect; that is, a ‘stabilizing’ of the drinking pace and an eventual decrease later in the evening (similar to 3); (3) whether any differences between drinking days and gender can be found with respect to this acceleration (similar to 4) and (4) whether the acceleration during the evenings is more pronounced among those with more harmful drinking habits.

Material and methods

Study design

Participants were recruited through (online) advertisements via a University website (for a detailed description of the study design, see 8, 9). Inclusion criteria were (1) being aged between 18–25 years; (2) drinking alcohol at least weekly; and (3) owning a smartphone with 3G internet access. The Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) data collection started on Thursdays following a baseline assessment. Six e‐mails, with alerts, were sent to participants’ smartphones (at 9 p.m., 10 p.m., 11 p.m., midnight, 1 a.m. and the next morning at 11 a.m.) every Thursday, Friday and Saturday for 5 consecutive weeks. Each message contained a link to a short online questionnaire.

Participants who successfully completed the baseline assessment and at least 66% of the EMA questionnaires received €50 (US$53) as an incentive. The Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social Sciences at Radboud University (ECG2013–1308‐117) approved the study, and all participants gave their informed consent. Data collection was conducted between September 2013 and January 2014.

Sample and data selection

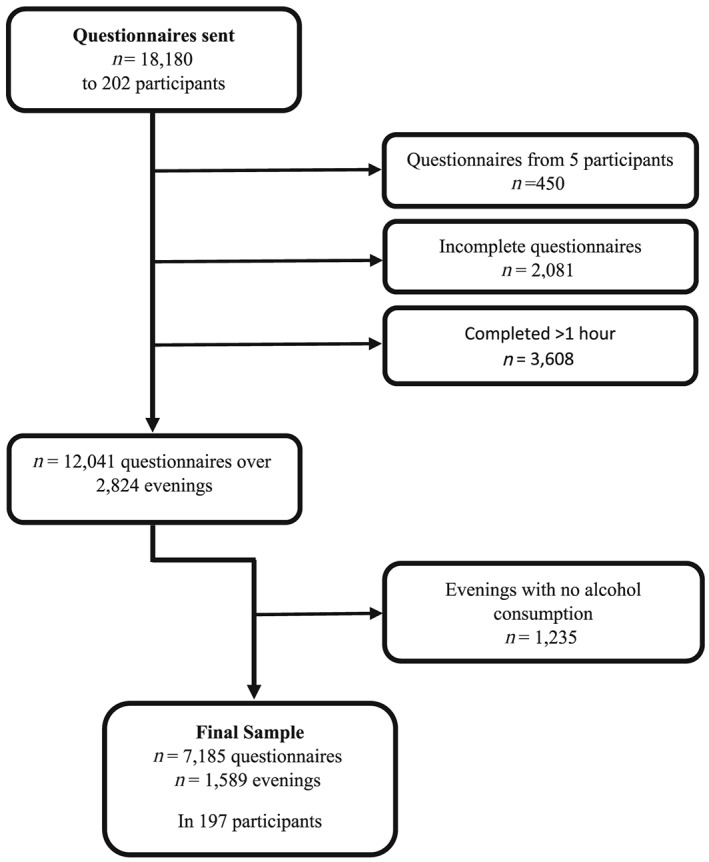

The original sample consisted of 202 participants and a total number of 18 180 questionnaires were sent. Data pertaining to five participants were excluded, as they had completed less than one‐third of all questionnaires. To ensure reliable data, incomplete questionnaires (n = 2081, 11.7%) and questionnaires completed more than 1 hour after distribution (n = 3608, 20.39%) were excluded from the analyses. The median response time for completion of the questionnaires was 7.31 minutes [standard deviation (SD) = 13.65, interquartile range (IQR) = 15.28]. For the growth curve analyses, evenings with no alcohol consumption (n = 1235, 43.7%) were excluded. The final sample consisted of 197 participants (96 women, 48.7%, medianage = 20.8, SD = 1.7) and 7185 assessments over 1589 evenings (see Fig. 1). The 2349 missing assessments in the remaining data set (1589*6)–7185; 15.4%) were taken into account by the full information maximum likelihood feature of Mplus statistical software. There were no major differences in the number of missing or excluded questionnaires between the days and gender. The missing data did not correlate with the level of harmful drinking, measured with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT 10, r = −0.056, P = 0.432), or the total amount of alcohol consumed during the data collection period (r = −0.051, P = 0.480). Also, there were no correlations between the excluded data and the AUDIT (r = −0.019, P =0.796) or the total amount of alcohol consumed during the data collection period (r = −–0.038, P = 0.600).

Figure 1.

Flow‐chart Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) data

Measures

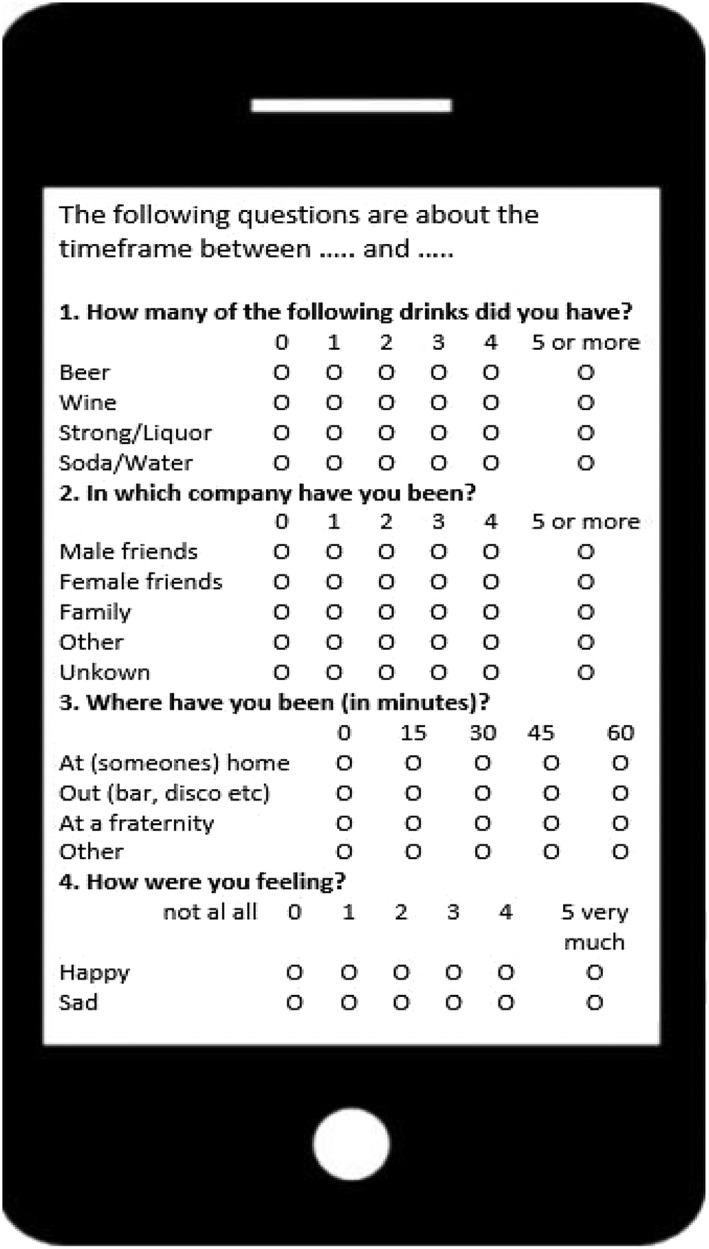

In the baseline questionnaire, participants were asked to indicate their gender and to complete the AUDIT, our measure for harmful drinking habits 10. For illustrative purposes, we divided the AUDIT scores using a median split, with the lower group scoring < 13 and the higher group above 13. In the EMA questionnaires (see Fig. 2), alcohol use was measured separately for each beverage type (‘beer’, ‘wine’ and ‘strong liquor’) by means of the following question: ‘Between [given hourly time‐frame, e.g. 10–11 p.m.], how many of the following drinks have you had?’. Answer categories ranged from ‘0’ to ‘5 or more’ (coded as 5.5). The number of alcoholic drinks (i.e. beer, wine, liquor) per time‐frame was added to generate a total alcohol consumption score for a given hour.

Figure 2.

Prototype of the Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) questionnaire sent to participants’ mobile phones

Statistical analyses

In multi‐level latent growth curve models performed in Mplus, the number of alcoholic drinks the participants indicated at each hour during the evenings were used to estimate (1) the intercept (i.e. the number of alcoholic drinks consumed in the first hour, i.e. 8–9 p.m.); (2) the linear slope (i.e. the change during the following hours); and (3) the quadratic slope. The reason for adding the quadratic slope was to provide evidence of a potential ceiling effect or ‘stabilization’ and eventually decrease in drinking pace later at night 3. This model was first estimated for all evenings together, followed by separate models for Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays, for men and women and for those with more or less harmful drinking habits (AUDIT scores). Subsequently, the differences between the days, gender and harmful drinking habits were tested by regressing the intercept and both the linear and quadratic slope on the day (i.e. between level predictor, using two dummy variables), gender (i.e. a dichotomous within‐level predictor) and AUDIT (i.e. a continuous within‐level predictor). The exact Mplus syntaxes are provided in the Supporting information.

Results

Descriptives

The participants were mainly university students (85%) and had average AUDIT scores of 12.79 (SD = 5.57). With an AUDIT cut‐off score of 8 for hazardous drinking, only 31 individuals (15%) were non‐problematic drinkers in our sample 10.

For both men and women, the percentage of drinkers increased considerably between 9 p.m. and 11 p.m. (see Table 1). The median consumption during an evening was 8.0 (IQR = 13.5), 8.0 (IQR = 11.5) and 8.0 (IQR = 11.0) drinks for men and 7.0 (IQR = 7.0), 5.0 (IQR = 6.0) and 4.5 (IQR = 7.05) drinks for women on Thursday, Friday and Saturday evenings, respectively.

Table 1.

Percentage of drinkers and consumed quantities among drinking evenings according to gender, day of the week and time‐period in the evening.

| 8–9 p.m. | 9–10 p.m. | 10–11 p.m. | 11 p.m.—midnight | Midnight—1 a.m. | After 1 a.m. | Total evening | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||||||

| Thursday | |||||||

| Percentage of drinkers | 38.4 | 44.6 | 47.2 | 50.7 | 53.5 | 53.6 | 67 |

| Average quantitya) | 1.24 (1.0/2.0) | 1.43 (1.0/2.0) | 1.78 (1.5/3.0) | 2.04 (2.0/3.0) | 2.32 (1.0/3.0) | 2.80 (1.0/4.38) | 9.27 (8.0/13.5) |

| Friday | |||||||

| Percentage of drinkers | 40 | 44.4 | 52.3 | 55.2 | 51.7 | 45.9 | 68.6 |

| Average quantitya | 1.53 (1.0/2.0) | 1.70 (1.0/2.0) | 2.14 (2.0/1.0) | 2.16 (1.0/2.0) | 2.24 (1.0/2.0) | 2.58 (0.0/5.5) | 10.19 (8.0/11.5) |

| Saturday | |||||||

| Percentage of drinkers | 38.3 | 48.9 | 51.7 | 54.1 | 55.6 | 49.8 | 71.3 |

| Average quantitya | 1.16 (1.0/2.0) | 1.51 (1.0/2.0) | 1.74 (1.0/2.0) | 1.89 (1.0/3.0) | 2.03 (1.0/2.0) | 2.28 (1.0/3.0) | 9.08 (8.0/11.0) |

| Women | |||||||

| Thursday | |||||||

| Percentage of drinkers | 22.6 | 30 | 31 | 38.2 | 44.7 | 43.4 | 46.3 |

| Average quantitya | 0.85 (0.0/1.0) | 1.08 (1.0/1.0) | 1.31 (1.0/1.1) | 1.53 (1.0/1.5) | 1.66 (2.0/2.0) | 1.77 (1.0/2.0) | 6.47 (7.0/7.0) |

| Friday | |||||||

| Percentage of drinkers | 20 | 30.5 | 38.9 | 39.3 | 44.0 | 33.3 | 51.8 |

| Average quantitya | 0.68 (0.0/1.0) | 0.93 (1.0/1.5) | 1.30 (10/1.5) | 1.23 (1.0/1.5) | 1.28 (1.0/2.0) | 1.34 (0.0/2.0) | 5.49 (5.0/6.0) |

| Saturday | |||||||

| Percentage of drinkers | 23.7 | 30.7 | 38.4 | 39.9 | 41.8 | 38.9 | 56.4 |

| Average quantitya | 0.70 (0.0/1.0) | 0.93 (1.0/1.0) | 1.22 (1.0/1.3) | 1.33 (1.0/2.0) | 1.51 (1.0/2.0) | 1.59 (0.0/2.0) | 5.92 (4.5/7.0) |

Average number of drinks among drinkers (median/interquartile range).

Drinking patterns during the course of the evening

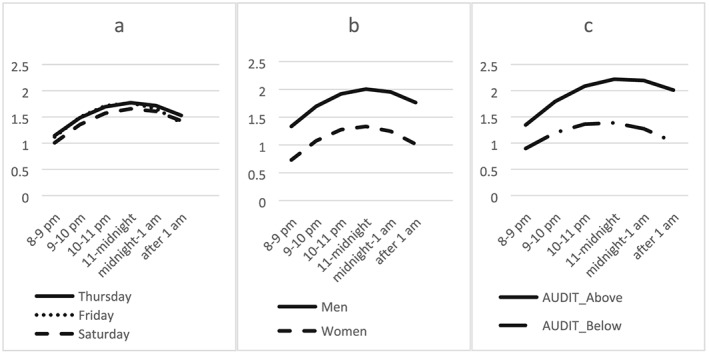

The results from the latent growth curve models (see Table 2) demonstrated that, in general, participants started with approximately one drink on average between 8 and 9 p.m. (=intercept). Subsequently, they tended to increase their number of drinks per hour by one‐third of a drink on average (linear slope). However, as indicated by the negative quadratic slope, this increase in drinking pace ‘stabilized’ as the evening progressed. These results were the same on Thursday, Friday and Saturday evenings (see Fig. 3a). Men and women showed basically the same drinking pattern during the evening, except that men started with approximately half a drink more between 8 and 9 p.m. (intercept difference) than women (see Fig. 3b). Finally, a significant difference was found in the number of drinks between 8 and 9 p.m. (intercept) and the linear slope in relation to the AUDIT score (see Fig. 3c).

Table 2.

Results of two latent growth curve models.

|

Intercept: number of alcoholic drinks in the first hour, 8–9 p.m. |

P |

Linear slope: change in drinking pace across hours |

P | Quadratic slope: curbing of drinking pace | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Across alla | ||||||

| 1.086 (0.055) | < 0.001 | 0.430 (0.045) | < 0.001 | −0.072 (0.008) | < 0.001 | |

| Separate for days | ||||||

| Thursdayb | 1.144 (0.077) | < 0.001 | 0.407 (0.074) | < 0.001 | −0.066 (0.015) | < 0.001 |

| Fridayc | 1.119 (0.091) | < 0.001 | 0.459 (0.070) | < 0.001 | −0.081 (0.014) | < 0.001 |

| Saturdayd | 1.007 (0.073) | < 0.001 | 0.414 (0.063) | < 0.001 | −0.066 (0.011) | < 0.001 |

| Separate for gender | ||||||

| Womene | 0.730 (.058) | < 0.001 | 0.417 (0.061) | < 0.001 | −0.072 (0.012) | < 0.001 |

| Menf | 1.334 (0.075) | < 0.001 | 0.431 (.062) | < 0.001 | −0.069 (0.011) | < 0.001 |

| Separate for AUDIT | ||||||

| Below median (< 13)g | 0.897 (0.064) | < 0.001 | 0.370 (0.056) | < 0.001 | −0.069 (0.011) | < 0.001 |

| Above median (> 13)h | 1.345 (0.086) | < 0.001 | 0.528 (0.074) | < 0.001 | −0.079 (0.014) | < 0.001 |

| Interaction effectsi | ||||||

| Friday (versus Thursday) | −0.002 (0.110) | 0.987 | 0.085 (0.095) | 0.374 | −0.022 (0.018) | 0.232 |

| Saturday (versus Thursday) | −0.081 (0.085) | 0.343 | −0.048 (0.077) | 0.534 | 0.015 (0.015) | 0.297 |

| Male (versus female) | 0.465 (0.099) | < 0.001 | 0.073 (0.095) | 0.438 | 0.011 (0.018) | 0.542 |

| AUDIT | 0.032 (0.011) | 0.003 | 0.021 (0.009) | 0.024 | −0.002 (0.002) | 0.235 |

Figures shown are unstandardized regression coefficients (standard errors in parentheses). Significant effects are shown in bold type. aModel fit: comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.962, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.953, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.059, 90% confidence interval (CI) (0.047, 0.072), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.035; bmodel fit: CFI = 0.927, TLI = 0.908, RMSEA = 0.083, 90% CI (0.061, 0.107), SRMR = 0.048; cmodel fit: CFI = 0.944, TLI = 0.931, RMSEA = 0.067, 90% CI (0.045, 0.090), SRMR = 0.052; dmodel fit: CFI = 0.965, TLI = 0.957, RMSEA = 0.059, 90% CI (0.038, 0.082), SRMR = 0.033; emodel fit: CFI = 0.908, TLI = 0.885, RMSEA = 0.078, 90% CI (0.059, 0.098), SRMR = 0.055; fmodel fit: CFI = 0.970, TLI = 0.963, RMSEA = 0.055, 90% CI (0.039, 0.072), SRMR = 0.035; gmodel fit: CFI = 0.946, TLI = 0.932, RMSEA = 0.059, 90% CI (0.043, 0.076), SRMR = 0.042; hmodel fit: CFI = 0.957, TLI = 0.946, RMSEA = 0.066, 90% CI (0.046, 0.086), SRMR = 0.041; imodel fit: CFI = 0.9550.TLI = 0.927, RMSEA = 0.043, SRMR(within) = 0.035, SRMR(between) = 0.016.

Figure 3.

Model‐based estimates of number of alcoholic drinks consumed per hour across the evening, separate for (a) days, (b) gender, (c) Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (using a median split; AUDIT_below < 13, AUDIT_above > 13)

Discussion

Aiming to provide evidence on an acceleration of drinking pace during the evening among frequently drinking young adults in the Netherlands, our results are consistent with previous findings revealing such an acceleration, i.e. the later the evening, the more alcohol was consumed per hour 4. While this acceleration was previously only found on Saturday evenings 4, our results show that this acceleration is even more common in the Netherlands, as it was present on all 3 days and for both men and women. These results, therefore, provide evidence for the robustness of this phenomenon of acceleration of (‘speeding up’) drinking pace, particularly at the beginning of the evening. Additionally, we revealed that this acceleration was more pronounced among those with more harmful drinking habits.

An explanation for the more common acceleration found in this study compared to previous studies could be the inclusion of participants who consumed excessive amounts of alcohol. Participants reported consuming on average six drinks for women and nine drinks for men during a drinking evening and an average baseline AUDIT score of 12, which is far above the cut‐off for hazardous and harmful alcohol use 10. This may be because our sample largely consisted of university students among whom heavy drinking is highly prevalent, whereas the previous studies also included participants from other educational settings 3, 4, 5. However, the presence of acceleration in drinking pace throughout all 3 days and gender groups could also be related to the Dutch drinking culture, in which binge drinking is common. Indeed, we found a more pronounced acceleration among those with more harmful drinking habits (as expressed by higher AUDIT scores). However, as there were only a few non‐problematic drinkers in our sample, we cannot draw conclusions about the general and mostly moderate drinking population. Future research should use a more diverse sample including individuals not only in terms of drinking habits, but also with lower education, different age groups and from different countries.

In addition, both a linear increase and a stabilization later in the evening was found on each of the 3 days included (see Fig. 3a). This finding is surprising, given that, in the literature, heavy drinking tends to occur on Friday and Saturday evenings rather than on Thursdays 1. However, we included Thursdays as it is a popular night to go out for (heavily drinking) students in the Netherlands, and indeed found no significant difference between the days.

A major strength of this study is the large amount of event‐level information we collected in participants’ natural environments. A limitation concerns the self‐reports, which may be inaccurate, particularly later in the evening when participants are becoming increasingly tired or intoxicated. The use of transdermal alcohol monitors may be a promising way to overcome this limitation in future research. Moreover, as alcohol use rarely occurs in isolation, the drinking pace is likely to be affected by characteristics of the social and physical environment 5, 11. In this study, we focused on the consistency of this acceleration in drinking pace and the relation to heavy drinking habits.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence that frequently drinking young adults in the Netherlands tend to accelerate their alcohol consumption on evenings at the end of the week, i.e. consume more and more drinks per hour, and indicates that this is consistent across gender and days. Additionally, we provide evidence that this tendency is even more pronounced for those with harmful drinking habits. From a public health perspective, raising awareness of this acceleration appears promising to reduce heavy drinking among young adults, especially among more heavy and harmful drinkers. This is urgently needed, given that, with a median consumption of six drinks among women and eight drinks among men, the current sample largely exceeds binge drinking thresholds when consuming alcohol on any given evening and are thus at risk of experiencing substantial adverse consequences 2.

Declaration of interests

None.

Supporting information

Data S1 Supporting information.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Rutger Engels and Maartje Luijten for their involvement in designing the study and comments on an earlier version of this manuscript and Megan Cook for English copy‐editing.

Groefsema, M. , and Kuntsche, E. (2019) Acceleration of drinking pace throughout the evening among frequently drinking young adults in the Netherlands. Addiction, 114: 1295–1302. 10.1111/add.14588.

References

- 1. Kuntsche E., Gmel G. Alcohol consumption in late adolescence and early adulthood—where is the problem? Swiss Med Wkly 2013; 143: 13826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kuntsche E., Kuntsche S., Thrul J., Gmel G. Binge drinking: health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychol Health 2017; 32: 976–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kuntsche E., Otten R., Labhart F. Identifying risky drinking patterns over the course of Saturday evenings: an event‐level study. Psychol Addict Behav 2015; 29: 744–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kuntsche E., Labhart F. Investigating the drinking patterns of young people over the course of the evening at weekends. Drug Alcohol Depend 2012; 124: 319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thrul J., Kuntsche E. The impact of friends on young adults’ drinking over the course of the evening—an event‐level analysis. Addiction 2015; 110: 619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bräker A. B., Soellner R. Alcohol drinking cultures of European adolescents. Eur J Public Health 2016; 26: 581–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization (WHO) . Global status report on alcohol and health. WHO: Geneva; 2018.

- 8. Smit K., Groefsema M., Luijten M., Engels R., Kuntsche E. Drinking motives moderate the effect of the social environment on alcohol use: an event‐level study among young adults. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2015; 76: 971–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Groefsema M., Engels R., Kuntsche E., Smit K., Luijten M. Cognitive biases for social alcohol‐related pictures and alcohol use in specific social settings: an event‐level study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2016; 40: 2001–2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Babor T. F., Higgins‐Biddle J. C., Saunders J. B., Monteiro M. G. AUDIT: the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: guidelines for use in primary care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Monk R. L., Heim D., Qureshi A., Price A. ‘I Have no clue what I drunk last night’: using smartphone technology to compare in‐vivo and retrospective self‐reports of alcohol consumption. PLOS ONE 2015; 10: e0126209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1 Supporting information.