Abstract

Background

For patients with intermediate‐thickness melanoma, surveillance of regional lymph node basins by clinical examination alone has been reported to result in a larger number of lymph nodes involved by melanoma than if patients had initial sentinel node biopsy and completion dissection. This may result in worse regional control. A prospective study of both regular clinical examination and ultrasound surveillance was conducted to assess the effectiveness of these modalities.

Methods

Between 2010 and 2014, patients with melanoma of thickness 1·2–3·5 mm who had under‐gone wide local excision but not sentinel node biopsy were recruited to a prospective observational study of regular clinical and ultrasound nodal surveillance. The primary endpoint was nodal burden within a dissected regional lymph node basin. Secondary endpoints included locoregional or distant relapse, progression‐free and overall survival.

Results

Ninety patients were included in the study. After a median follow‐up of 52 months, ten patients had developed nodal relapse as first recurrence, four had locoregional disease outside of an anatomical nodal basin as the first site of relapse and six had relapse with distant disease. None of the patients who developed relapse within a nodal basin presented with unresectable nodal disease. The median number of involved lymph nodes in patients undergoing lymphadenectomy for nodal relapse was 1 (range 1–2; mean 1·2).

Conclusion

This study suggests that ultrasound surveillance of regional lymph node basins is safe for patients with melanoma who undergo a policy of nodal surveillance.

Introduction

The most common site of initial spread from cutaneous melanoma is to the regional draining lymph nodes, which occurs at a median of 18 months after initial presentation1. There are a number of options for managing patients with a clinically normal regional lymph node basin (no palpable nodes). Options include regular evaluation by clinical examination alone2, regular surveillance by imaging such as ultrasonography3, 4, or prophylactic surgery to the lymph node basin performed at the same time as wide excision of the primary melanoma. This is usually sentinel node biopsy (SNB) with or without subsequent completion lymph node dissection (CLND) for patients with a positive SNB5, 6.

SNB is a minimally invasive surgical procedure that provides accurate prognostic information for patients beyond that which is available from analysis of the primary melanoma. In the final report of Multicentre Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT) I7, which randomized patients to SNB with CLND if indicated compared with clinical observation alone, sentinel node status was the most important prognostic factor for death from melanoma (hazard ratio 2·40, 95 per cent c.i. 1·61 to 3·56; P < 0·001). In the era of effective adjuvant therapy, risk stratification on the basis of a positive sentinel node may determine whether patients benefit from adjuvant treatment or be considered for entry into further clinical trials.

The role of SNB as a therapeutic procedure over and above providing prognostic information remains an area of debate. For patients with intermediate‐thickness melanoma (1·2–3·5 mm), the nodal burden in dissected regional lymph nodes after a positive SNB was lower than that in patients who underwent CLND after clinical detection of involved lymph nodes (1·4 versus 3·3 nodes involved)8. No difference in melanoma‐specific survival (MSS) was demonstrated between SNB and clinical observation in MSLT‐I (5‐year MSS 87·1 versus 86·6 per cent). However, direct comparison of the 122 of patients who were sentinel node‐positive and underwent CLND and the 78 patients who underwent total lymph node dissection after clinical detection demonstrated a substantial difference in MSS, although this subgroup analysis may have inherent bias as the groups were not randomized9. Furthermore, the SNB‐positive group excluded 26 patients with a false‐negative result, who developed nodal disease after a negative SNB, a group with a particularly poor outlook in terms of nodal burden and MSS.

High‐resolution ultrasound imaging coupled with fine‐needle aspiration (FNA) cytology has been demonstrated to detect involvement of lymph nodes by melanoma effectively, and has much greater sensitivity and specificity than clinical examination alone3, 4, 10. Two recent RCTs5, 6 have analysed clinical follow‐up including ultrasound examination of the regional lymph nodes with CLND in patients who were previously found to have a positive SNB. Both studies showed no difference in MSS between study arms, and did not report any negative outcome in terms of regional nodal basin control when regular ultrasound examination was used as the method of surveillance.

To further clarify the role of clinical examination and high‐resolution ultrasound surveillance in detecting regional lymph node metastases, a prospective observational cohort study was conducted in patients who had wide excision for intermediate‐thickness melanoma (Breslow thickness 1·2–3·5 mm) but did not have SNB.

Methods

Eligible patients were aged at least 18 years with histologically proven stage I or II cutaneous melanoma at any anatomical site, with a Breslow thickness between 1·2 and 3·5 mm, awaiting wide local excision. All patients had been offered SNB at a referring institution, but had declined the procedure. Patients who had already undergone wide local excision elsewhere or who were deemed unfit for lymphadenectomy should the need arise were excluded, as were those with any malignancy diagnosed within the previous 5 years. The histopathology specimens from the primary diagnostic excision, if available, were reviewed.

Study design

This was a prospective, non‐randomized, single‐centre cohort study. Ethical approval was granted from the institutional ethics committee (CCR3228). Patients were assigned to a programme of ultrasound surveillance comprising ultrasound assessment of the regional lymph node basin at baseline and at every 3 months in the first year, every 4 months in the second and third years, and every 6 months in the fourth and fifth years. Ultrasound examinations were done by one of two consultant radiologists using a high‐resolution ultrasound scanner (Logiq™ E9; GE Healthcare, Amersham, UK) with a 10–15‐MHz transducer.

At each examination, the location, size, shape, number, position, cortical thickness, and presence of peripheral vascularity in the regional lymph nodes were recorded. Where there was suspicion of metastatic disease (according to the above criteria), ultrasound‐guided FNA was performed. If relapsed melanoma was confirmed on FNA, patients were offered lymphadenectomy. Equivocal ultrasound and cytological assessments were repeated after 4–6 weeks, in accordance with normal clinical practice.

The primary endpoint was the nodal burden (number of positive lymph nodes) at the time of lymphadenectomy, should it be required. Secondary endpoints included the percentage of patients developing regional lymph node metastases, the percentage of patients presenting with unresectable regional lymph node metastases, the percentage of patients developing distant metastases, and the percentage of patients developing a wound infection or lymphoedema following lymphadenectomy.

Patients who developed either a nodal or distant relapse were subsequently treated along a normal melanoma pathway, either with ongoing surveillance and regular cross‐sectional imaging for patients with fully resected stage III disease, or with immunotherapy or targeted therapy for patients with stage IV disease. If patients developed an in‐transit metastasis between the primary melanoma and the draining regional nodal basin as the first site of relapse, ongoing ultrasound surveillance according to the study protocol was permitted.

Statistical analysis

It was hypothesized that the nodal burden in regional lymph node metastases detected by ultrasound surveillance would be the same as that in patients undergoing SNB. In the MSLT‐I trial7, the mean nodal burden of patients undergoing SNB was 1·1 positive nodes. However, in the 22 per cent of patients randomized to the observation arm who later developed regional lymph node metastases, the mean nodal burden was 3·3 positive nodes. The planned sample size for this study was 90 patients. Assuming that 20 per cent of these patients would develop regional lymph node metastases, this would provide 90 per cent power for a two‐sided α of 5 per cent. The nodal burden rate was compared using an independent t test. Five‐year rates of nodal metastasis and distant metastasis were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method11. All statistical analyses were done using Stata® release 13 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

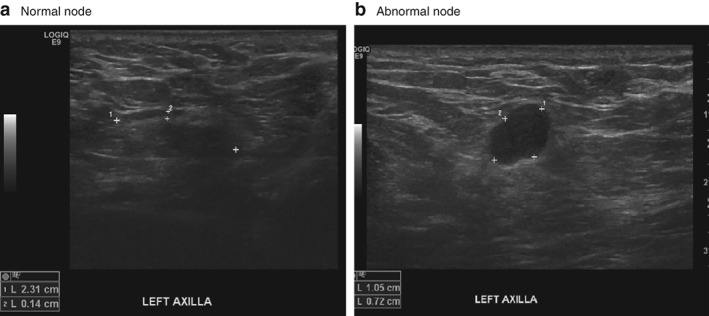

Between August 2010 and November 2014, 90 patients were recruited to the study. One was excluded after pathological review, in whom the Breslow thickness was found to be 8 mm having originally been reported as 3 mm. A further patient had the Breslow thickness reclassified from 1·2 to 1·11 mm on pathological review, but was retained in the study. Baseline characteristics of 89 patients included are shown in Table 1. Examples of normal and abnormal appearances of regional lymph nodes on ultrasound are shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| No. of patients* | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) † | 60 (48–69, 22–91) |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 45 : 44 |

| Breslow thickness ‡ | 1.9 (1·1–3·5) |

| Ulceration (n = 70) § | |

| Ulcerated | 12 (17) |

| Non‐ulcerated | 58 (83) |

| Clark level (n = 65) § | |

| 1 | 1 (2) |

| 2 | 0 (0) |

| 3 | 19 (29) |

| 4 | 44 (68) |

| 5 | 1 (2) |

| Anatomical location | |

| Arm | 18 (20) |

| Legs | 32 (36) |

| Trunk | 25 (28) |

| Head/neck | 13 (15) |

| Vulval perineum | 1 (1) |

With percentages in parentheses unless indicated otherwise; values are

median (i.q.r., range) and

median (range).

Percentages based on number of patients with data available.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound images of normal and abnormal appearances of regional lymph nodes a Normal node in left axilla, characterized by an ovoid shape, central hilar fat and less than 2 mm peripheral lymphoid tissue. b Abnormal metastatic node in left axilla, characterized by hypoechoic attenuation, loss of hilar sinus fat and a more circular configuration.

Median follow up was 52 (range 42–92) months. After 5 years, the overall survival rate in the study was 94 (95 per cent c.i. 85 to 97) per cent; the progression‐free survival rate was 73 (60 to 83) per cent and the risk of nodal metastasis 13 (7 to 23) per cent (Fig. S1 , supporting information).

In total, 20 patients (22 per cent) developed a proven relapse; ten patients (11 per cent) presented with a lymph node metastasis within a nodal basin as the site of first recurrence. Four patients (4 per cent) had locoregional relapse outside a defined nodal basin (in‐transit disease) and six (7 per cent) had relapse at distant sites as the site of first recurrence. One patient had a suspicious lymph node in the right postauricular region, cytology from which demonstrated numerous atypical cells that were consistent morphologically with malignant melanoma; however, subsequent histology from an ultrasound‐guided excision biopsy and then selective neck dissection failed to demonstrate any evidence of melanoma. The patient remains free from disease.

Of the ten patients who presented with a lymph node basin relapse as the site of first recurrence, five had a clinically normal examination immediately before ultrasound surveillance, which then demonstrated a morphologically abnormal lymph node. Cytology performed under ultrasound guidance demonstrated metastatic melanoma in all five patients. Of these, four had disease within the axilla and one in the groin. The other five patients had a clinically abnormal lymph node identified by the examining physician or self‐reported a mass that was then confirmed by clinically guided or ultrasound‐guided cytology. Of these, two were in the neck, two in the axilla and one in the groin. One of these patients had been recalled on the basis of a suspicious ultrasound examination but normal cytology 6 weeks earlier.

Of the ten patients presenting with nodal relapse, nine proceeded immediately to nodal dissection. One patient was identified to have synchronous widespread distant disease and had chemotherapy without nodal dissection. Among the nine patients who underwent nodal dissection, the median number of involved lymph nodes was 1 (range 1–2; mean 1·2) (Table 2). Four of these patients subsequently developed distant metastatic disease after a median further interval of 11 (range 2–37) months. Of the remaining five patients, four remain disease‐free, whereas one has no reported follow‐up after surgery. Postoperative complications were noted in three of the nine patients undergoing lymphadenectomy; two developed a wound infection requiring oral antibiotics and one mild persistent lymphoedema (1 per cent).

Table 2.

Lymphadenectomies and nodal burden for patients with relapse in regional lymph nodes as first site of disease, identified by clinical examination and ultrasound surveillance

| No. of patients* | |

|---|---|

| Lymphadenectomy | 9 |

| Inguinal | 2 |

| Axilla | 6 |

| Neck | 1 |

| Total no. of nodes removed | |

| Mean | 23·1 |

| Median (i.q.r.) | 20 (15–25) |

| No. of positive nodes removed | |

| Mean | 1·2 |

| Median (i.q.r.) | 1 (1–1) |

Unless indicated otherwise.

Of the four patients who presented with in‐transit disease as the first site of relapse, two have not subsequently developed nodal disease and remain under surveillance. One patient presented with a palpable local recurrence immediately adjacent to the original melanoma scar, and subsequently developed extensive bulky in‐transit disease in the leg. This patient was treated with induction vemurafenib followed by surgery, and remains in complete remission. The remaining patient presented with an in‐transit deposit on the chest wall from a truncal melanoma and developed subsequent axillary nodal disease treated with lymphadenectomy, but then went on to develop distant disease.

Of the six patients who presented with distant disease, five were investigated for self‐reported symptoms. The remaining patient, with a melanoma on the lower back, presented with a left supraclavicular (Virchow's) node identified on clinical examination and was then found to have wide‐spread intra‐abdominal disease on staging investigations.

Discussion

This analysis of a cohort of patients with intermediate‐thickness melanoma who did not undergo SNB demonstrated that a programme of regular high‐resolution ultrasound and clinical examinations resulted in a nodal burden rate at operation that was equivalent to that reported previously for patients with equivalent Breslow thickness who underwent SNB and CLND8. The median number of involved lymph nodes in this study was 1. Approximately half of the patients who presented with nodal disease as the first site of relapse were identified by ultrasound imaging, the majority of whom had disease in the axilla.

In the UK, the current national guidance2 is that SNB should be offered to all patients with cutaneous melanoma greater than 1 mm in thickness, but in the context of a discussion regarding the advantages and disadvantages of the procedure. Given the uncertainty about a proven survival benefit for patients undergoing SNB versus clinical observation, the principal focus of guidance is in the value of the prognostic information provided by SNB balanced against the small morbidity associated with SNB. One of the concerns raised with omitting SNB is that the tumour burden in the regional lymph node basin may be three times higher by the time metastatic lymph nodes become palpable8. The present results would appear to show that the addition of regular ultrasound examination at the time of follow‐up visits can avoid a higher nodal burden rate.

Recent publications12, 13, 14, 15 from a number of RCTs of adjuvant immunotherapy and targeted therapy for melanoma have showed considerably improved melanoma relapse‐free survival. Thus, it is seems likely that in the future most patients with intermediate‐thickness primary melanoma will be advised to have SNB as a higher risk stratification would direct potentially effective adjuvant treatment. There may be circumstances where, even when effective adjuvant therapy is available, prognostic information gained from SNB does not alter management. This may be the case for patients with high‐risk primary melanoma (thicker than 4 mm and ulcerated), who can have a worse prognosis than those who have intermediate‐thickness melanomas and are SNB‐positive but do not have any other adverse prognostic features1. Hence for thick, ulcerated primary melanomas, adjuvant treatment would be indicated and sentinel node status may not be relevant.

For patients with intermediate‐thickness melanoma in whom sentinel node status is likely to provide information that may govern adjuvant treatment, the role of ultrasound imaging is less clear. Patients not eligible or appropriate for adjuvant therapy may choose not to undergo SNB to avoid the morbidity of the procedure. Although the risk of complications is small, in the recent MLST‐25 lymphoedema was seen in 6 per cent of the observation arm, compared with 24 per cent of patients who underwent CLND. The rate of lymphoedema was very low in the present study (1 per cent) as 90 per cent of patients avoided any surgical procedure and only one of nine who underwent lymphadenectomy for low‐volume disease developed lymphoedema.

Some criticisms could be applied to the present study. First, the study was performed in a tertiary melanoma referral centre and recruited a significant proportion of patients from secondary centres where SNB was performed routinely in patients with intermediate‐thickness melanoma. This is likely to have introduced selection bias. It may well be the case that the patients who opted into this surveillance protocol would be more likely than the whole population to attend regularly for follow‐up. Second, even though the entry criteria in terms of Breslow thickness were identical, the actual rate of nodal positivity here was lower than that in the observation arm of MLST‐I (11 versus 16 per cent), which may be because the rate of ulceration was lower in the present study (17 versus 27 per cent).

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Kaplan–Meier survival curves

Acknowledgements

The lead author (the manuscript's guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, Thompson JF, Atkins MB, Byrd DR et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 6199–6206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Macbeth F, Newton‐Bishop J, O'Connell S, Hawkins JE; Guideline Development Group . Melanoma: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2015; 351: h3708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bafounta ML, Beauchet A, Chagnon S, Saiag P. Ultrasonography or palpation for detection of melanoma nodal invasion: a meta‐analysis. Lancet Oncol 2004; 5: 673–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blum A, Schlagenhauff B, Stroebel W, Breuninger H, Rassner G, Garbe C. Ultrasound examination of regional lymph nodes significantly improves early detection of locoregional metastases during the follow‐up of patients with cutaneous melanoma: results of a prospective study of 1288 patients. Cancer 2000; 88: 2534–2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Faries MB, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, Andtbacka RH, Mozzillo N, Zager JS et al. Completion dissection or observation for sentinel‐node metastasis in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 2211–2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leiter U, Stadler R, Mauch C, Hohenberger W, Brockmeyer N, Berking C et al.; German Dermatologic Cooperative Oncology Group (DeCOG). Complete lymph node dissection versus no dissection in patients with sentinel lymph node biopsy positive melanoma (DeCOG‐SLT): a multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: 757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, Mozzillo N, Nieweg OE, Roses DF et al.; MSLT Group. Final trial report of sentinel‐node biopsy versus nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 599–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, Mozzillo N, Elashoff R, Essner R et al.; MSLT Group. Sentinel‐node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 1307–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. A'Hern RP. Sentinel‐node biopsy in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Voit C, Mayer T, Kron M, Schoengen A, Sterry W, Weber L et al. Efficacy of ultrasound B‐scan compared with physical examination in follow‐up of melanoma patients. Cancer 2001; 91: 2409–2416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 1958; 53: 457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weber J, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M, Gogas HJ, Arance AM, Cowey CL et al. Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1824–1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Long GV, Hauschild A, Santinami M, Atkinson V, Mandalà M, Chiarion‐Sileni V et al. Adjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib in stage III BRAF‐mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1813–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandala M, Long GV, Atkinson V, Dalle S et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 1789–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eggermont AM, Chiarion‐Sileni V, Grob JJ, Dummer R, Wolchok JD, Schmidt H et al. Prolonged survival in stage III melanoma with ipilimumab adjuvant therapy. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1845–1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Kaplan–Meier survival curves