Abstract

Purpose

To identify the proportion of older adults with a high anticholinergic/sedative load and to identify patient subgroups based on type of central nervous system (CNS)‐active medication used.

Methods

A cross‐sectional study of a nationwide sample of patients with anticholinergic/sedative medications dispensed by 1779 community pharmacies in the Netherlands (90% of all community pharmacies) in November 2016 was conducted. Patients aged older than 65 years with a high anticholinergic/sedative load defined as having a drug burden index (DBI) greater than 1 were included. Proportion of patients with a high anticholinergic/sedative load was calculated by dividing the number of individuals in our study population by the 2.4 million older patients using medications dispensed from study pharmacies. Patient subgroups based on type of CNS‐active medications used were identified with latent class analysis.

Results

Overall, 8.7% (209 472 individuals) of older adults using medications had a DBI greater than 1. Latent class analysis identified four patient subgroups (classes) based on the following types of CNS‐active medications used: “combined psycholeptic/psychoanaleptic medication” (class 1, 57.9%), “analgesics” (class 2, 17.9%), “antiepileptic medication” (class 3, 17.8%), and “anti‐Parkinson medication” (class 4, 6.3%).

Conclusions

A large proportion of older adults in the Netherlands had a high anticholinergic/sedative load. Four distinct subgroups using specific CNS‐active medication were identified. Interventions aiming at reducing the overall anticholinergic/sedative load should be tailored to these subgroups.

Keywords: aged, drug burden index, drug utilisation research, hypnotics and sedatives, latent class analysis, muscarinic antagonists, pharmacoepidemiology

KEY POINTS.

A large proportion of older community‐dwelling patients in the Netherlands had a high load of anticholinergic/sedative medication.

According to the type of CNS‐active medications used, four distinct patient subgroups with high anticholinergic/sedative loads were identified using latent class analysis.

Interventions aiming at reducing the cumulative anticholinergic/sedative load can be targeted to these patient subgroups.

1. INTRODUCTION

Despite their adverse effects on physical and cognitive function,1, 2 anticholinergic and sedative medications are frequently prescribed to older patients.3, 4 Some medications are deliberately prescribed for their anticholinergic or sedative effect, for example, inhaled anticholinergics for chronic airway diseases or benzodiazepines for insomnia. However, for most medications, the anticholinergic/sedative effect is a side effect.5 Anticholinergic/sedative medications mostly act on the central nervous system (CNS) and include psycholeptics, psychoanaleptics, and analgesics.6 So far, most research has focused on quantifying the cumulative exposure of multiple anticholinergic/sedative medications in older patients with polypharmacy.7 Little is known about the prevalence of combinations of multiple anticholinergic/sedative medications resulting in a high load or whether subgroups of these patients based on types of anticholinergic/sedative medications used can be identified.

Latent class analysis (LCA) is a person‐centred approach, which identifies underlying patterns within populations that cannot be directly measured or observed.8 In a population of older adults having a high anticholinergic/sedative load, LCA has the potential to identify subgroups of patients based on specific medication patterns or types of anticholinergic/sedative medications used. This is a novel approach to investigate medication use. In this study, we will firstly determine the proportion of older adults having a high cumulative anticholinergic/sedative load, and secondly, we will perform an LCA to identify subgroups of patients based on the most likely type of CNS‐active medications used.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and setting

A cross‐sectional study on a nationwide sample of patients with prescriptions for anticholinergic/sedative medications dispensed by community pharmacies in the Netherlands in November 2016 was conducted. Data were provided by the Foundation for Pharmaceutical Statistics (Stichting Farmaceutische Kengetallen [SFK]),9 which identified 783 540 older patients aged 65 years and over from 1779 community pharmacies (90% of total Dutch community pharmacies) using at least one anticholinergic/sedative medication in the study period. The SFK collects exhaustive data about medications dispensed by more than 95% of all community pharmacies in the Netherlands.9 Dutch community pharmacies keep complete electronic medication records of their patients, and patients usually register with a single pharmacy for medication supply (a closed pharmacy system).10 Our data therefore provide a good approximation of patients' overall medication use.

2.2. Anticholinergic and sedative load

Anticholinergic/sedative medication load was quantified with the drug burden index (DBI).11 Previous studies have identified that a higher DBI was associated with an increased risk of medication harm among older populations.12 The DBI was calculated using the following formula:

where D = prescribed daily dose and δ = the minimum recommended daily dose according to Dutch pharmacotherapeutic reference sources.13, 14

All prescription medications dispensed by the pharmacy with mild or strong anticholinergic and/or sedative (side) effects with a usage date in the study period (1 month) were included in the DBI calculation. Medications without known prescribed daily dose and preparations for which daily dose could not be determined were excluded from the DBI calculation. These comprised dermatological, gastro enteral, nasal, rectal, and vaginal preparations, oral fluids, oral and sublingual sprays, oral drops, parenteral medications and “as needed” medications. Our database did not include data of medications dispensed “over the counter”.

We included all medications classified as anticholinergic by Duran et al.6 Then, we systematically reviewed all other medications used in the Netherlands and included those with anticholinergic or sedative properties and those with frequently reported sedative side effects reported in Dutch pharmacotherapeutic reference sources.13, 14

Following the formula above, the DBI per medication ranged between 0 and 1, depending on the prescribed daily dose. If the prescribed daily dose was similar to the minimum recommended daily dose, the DBI for that medication would be 0.5. In our study, we include patients with a DBI greater than 1. A DBI above this threshold was considered a high anticholinergic/sedative load.

2.3. Study population

All older adults, aged older than 65 years, with a high anticholinergic/sedative load, that is a DBI greater than 1, were identified from medication dispensing records and included in the study.

We excluded 16 498 patients (2.1% of all patients) from 32 pharmacies (1.8% of all pharmacies in database) using a pharmacy information system with a specific software package, as this software was known for reporting errors in dispensing dates. We also excluded 868 patients with unknown gender and/or age or reported age older than 110 years (0.11%).

2.4. Data source

The dataset contained demographic patient data that were collected by SFK, such as anonymous patient identification code, age, gender, anonymous pharmacy code, and medication data including generic name, daily defined dose, preparation form, and World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code (2016).15

2.5. Outcomes and statistics

The proportion of older adults having a high anticholinergic/sedative load was calculated by dividing the number of individuals in our study population by the number of older adults (aged ≥65 years) who were dispensed at least one medication with a usage date within the study period from one of the community pharmacies included in our study.

Identification of subgroups of patients with a high anticholinergic/sedative load was examined with LCA in M‐Plus version 7.4.16 Subgroup identification was based on most likely type of CNS‐active medications (ATC code starting with N) used by a patient within each subgroup (class). We focused on CNS‐active medications as these included most anticholinergic/sedative medications. CNS‐active medications were grouped by ATC code level 2 and were included in the analysis if used by at least 5% of the study population. Use of CNS‐active medications per patient was treated as a categorical variable (dispensed/not dispensed). LCA was performed in a successive forward manner. We started with a single class model with the assumption that all patients used the same types of CNS‐active anticholinergic/sedative medications. This corresponds to a standard descriptive analysis of the medication use of the whole study population. Then, successive LCA models were performed, adding one class extra at a time. The most likely number of patient subgroups (classes) was identified by evaluating the statistical “goodness of fit” of the different models with n‐classes. Various goodness of fit statistics are available for LCA. We inspected the Bayesian inspection criterion (BIC), the Lo–Mendell–Rubin Likelihood ratio test (LMR), and the entropy. For the best fitting model, the BIC value should be lowest. The LMR tested whether the current model with n‐classes was better than the previous model with n‐1 classes. Improvement was deemed significant if the associated p value was less than 0.05. Higher entropy, which is a quality indicator of classification ranging from 0 to 1, indicated a better classification. Entropy values greater than 0.8 were acceptable. To identify clinically relevant classes, alongside goodness of fit, we only considered models with patient subgroups (classes) that consisted of at least 5% of the study population.8 As convergence of local solutions is a common issue of LCA, we increased the number of random starts when necessary to get global solutions. We fixed thresholds of parameter estimates to the observed probabilities if necessary. Following these criteria above, we identified the best fitting model with n‐classes and subsequently assigned patients to their most likely class based on model probabilities. Demographic descriptives of all patients and of patients within each class were derived in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Proportion of older adults with high anticholinergic/sedative load

We found 766 174 older adults who were dispensed at least one anticholinergic/sedative medication from one of 1747 community pharmacies in the Netherlands (88% of total). Of this population, 11 758 patients (1.5%) were excluded, as for these patients, the DBI could not be calculated. A total of 544 944 (71.1%) had a DBI between 0 and 1, and 209 472 (27.3%) had a DBI greater than 1. Patients with a DBI greater than 1 were slightly more female (66.9% versus 62.3 and 60.7%), (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients aged 65 years and over using at least one anticholinergic/sedative medication, those having a DBI between 0 and 1, and those having a DBI greater than 1

| Patients Aged 65 years and Over | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Using at least one anticholinergic/sedative medication | Having a DBI between 0 and 1 | Having a DBI ≥ 1 (study population) | |

| Number of patients (%) | 766 174 (100)a | 544 944 (71.1) | 209 472 (27.3) |

| Gender (% female) | 62.3 | 60.7 | 66.9 |

| Age (mean [SD]) | 75.9 (7.7) | 75.8 (7.7) | 75.9 (7.8) |

| Number anticholinergic/sedative medications (mean [SD]) | 1.5 (0.9) | 1.1 (0.3) | 2.6 (1.0) |

| Top 5 used anticholinergic/sedative medications by ATC code level 3 (ATC code, % of patients) | Antidepressants (N06A, 26.1) | Antidepressants (N06A, 18.6) | Antidepressants (N06A, 46.7) |

| Hypnotics and sedatives (N05C, 19.2) | Drugs for obstructive airway disease (R03B, 15.0) | Hypnotics and sedatives (N05C, 33.4) | |

| Anxiolytics (N05B, 16.5%) | Hypnotics and sedatives (N05C, 14.1) | Anxiolytics (N05B, 33.2) | |

| Drugs for obstructive airway disease (R03B, 16.1) | Anxiolytics (N05B, 10.4) | Opioids (N02A, 22.6) | |

| Opioids (N02A, 13.1) | Opioids (N02A, 9.2) | Antiepileptics (N03A, 18.6) | |

| Patients using anticholinergic medications (number, %) | 543 652 (71.0) | 351 502 (64.5) | 184 604 (88.1) |

Abbreviations: ATC, anatomical therapeutic chemical; DBI, drug burden index; SD, standard deviation.

Of this population, 11 758 patients (1.5%) were excluded, as for these patients, the DBI could not be calculated.

About 2.4 million older people were dispensed at least one medication within the study period from one of the 1747 study pharmacies. Therefore, 31.9% of the Dutch older adults using medication were dispensed at least one anticholinergic/sedative medication, and 8.7% had a high anticholinergic/sedative load (DBI ≥ 1).

3.2. Identification of patient subgroups (classes) using LCA

Types of CNS‐active medications used by at least 5% of the study population were psycholeptics (including antipsychotics, anxiolytics, and hypnotics/sedatives [ATC N05, 62.6%]), psychoanaleptics (including antidepressants, psychostimulants, and combinations of psycholeptics/psychoanaleptics [ATC N06, 48.7%]), analgesics (ATC N02, 23.4%), antiepileptics (ATC N03, 18.6%), and anti‐Parkinson medication (ATC N04, 8.4%). On these medication types, an LCA for a two‐, three‐, four‐ and five‐class model was performed. Goodness of fit statistics indicated that the population was most likely comprised of four classes. The BIC was lowest for the four‐class model, the p values of the LMR indicated that the four‐class model was better than a three‐class and a five‐class model, and it had the clearest classification indicated by the highest entropy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Goodness of fit statistics of latent class analysis

| Lo–Mendell–Rubin | Percentage of Patients in Class | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | BIC | 2LL | p value | Entropy | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| 2 | 1099816 | 16928 | 0.000 | 0.520 | 52.1 | 48.0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 3 | 1093340 | 11551 | 0.000 | 0.691 | 37.7 | 37.4 | 24.9 | ‐ | ‐ |

| 4a | 1089137 | 339641 | 0.000 | 0.961 | 57.9 | 17.9 | 17.8 | 6.3 | ‐ |

| 5 | 1093671 | 87912 | 0.333 | 0.830 | 35.7 | 25.0 | 13.7 | 13.0 | 12.6 |

Abbreviations: BIC, Bayesian information criterion; 2LL, two log likelihood value.

Best fitting model.

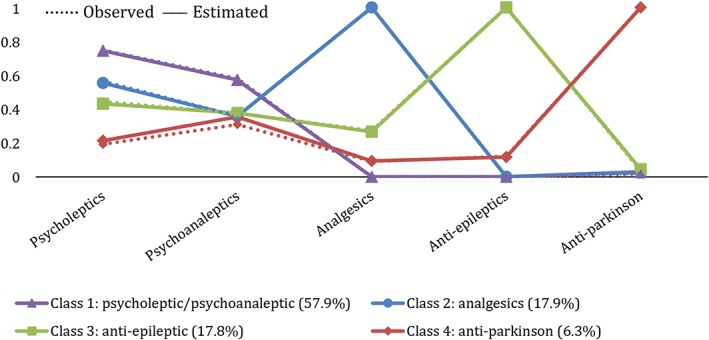

The four patient subgroups (classes) were described after their most likely type of CNS‐medications used, namely, “combined psycholeptic/psychoanaleptic medication” (class 1, 57.9%), “analgesics” (class 2, 17.9%), “antiepileptic medication” (class 3, 17.8%), and “anti‐Parkinson medication” (class 4, 6.3%), (Figure 1). Probabilities of a patient within each class to use a medication from the five types of CNS‐active medications were derived from the LCA. Estimated probabilities were comparable with observed probabilities.

Figure 1.

Estimated and observed probabilities of a patient within each class to use a medication from the five types of central nervous system (CNS)‐active medications [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Distribution of characteristics across the four identified patient subgroups (classes).

The four patient subgroups (classes) differed in age, gender, DBI, and mean number of anticholinergic/sedative medications (Table 3). Analgesics users (class 2) were oldest (77.3, SD 8.3), and antiepileptic medication users (class 3) had the highest number of anticholinergic/sedative medications (3.0, SD 1.2). Anti‐Parkinson medication users (class 4) and antiepileptic medication users (class 3) had the lowest proportion of females. Antidepressants (ATC N06A) were the most commonly used medication group across all four classes, whereas the most frequently used individual medications in each class were oxazepam (class 1, 23.9%), fentanyl (class 2, 37.8%), pregabalin (class 3, 40.1%), and levodopa with carbidopa or benserazide (class 4, 65.1%). A list of the top 10 most used anticholinergic/sedative medications is shown in Table S1.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the study population and the four identified classes

| Characteristic | Class 1: Psycholeptic and Psychoanaleptic | Class 2: Analgesics | Class 3: Antiepileptic | Class 4: Anti‐Parkinson |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 121 306 | 37 575 | 37 343 | 13 238 |

| Size of class (%) | 57.9 | 17.9 | 17.8 | 6.3 |

| Age (mean [SD]) | 75.9 (7.7) | 77.3 (8.3) | 74.7 (7.3) | 75.7 (7.0) |

| Gender (% women) | 69.4 | 71.0 | 60.8 | 50.4 |

| DBI (mean [SD]) | 1.5 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.7) | 1.5 (0.5) |

| Number of anticholinergic/sedative medications (mean [SD]) | 2.4 (0.7) | 2.8 (1.0) | 3.0 (1.2) | 2.7 (0.8) |

| Medications used by at least 5% of study population included in latent class analysis | ||||

| Antidepressants (N06A) | 55.8 | 35.0 | 36.7 | 24.3 |

| Hypnotics and sedatives (N05C) | 39.4 | 33.4 | 22.4 | 9.8 |

| Anxiolytics (N05B) | 41.4 | 27.6 | 21.2 | 7.2 |

| Opioids (N02A) | 0.0 | 96.2 | 26.6 | 9.0 |

| Antiepileptics (N03A) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 12.2 |

| Antipsychotics (N05A) | 15.8 | 6.7 | 10.8 | 5.3 |

| Dopaminergic anti‐Parkinson (N04B) | 1.7 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 98.7 |

| Medications used by at least 5% of study population not included in latent class analysis | ||||

| Anticholinergic inhalants (R03B) | 20.3 | 15.1 | 11.6 | 7.9 |

| Antihistamines for systemic use (R06A) | 10.0 | 5.9 | 5.2 | 3.4 |

| Urologicals (G04B) | 8.5 | 6.0 | 6.8 | 10.0 |

| Cough suppressants (R05D) | 7.7 | 4.8 | 3.7 | 3.2 |

Abbreviations: DBI, drug burden index; SD, standard deviation.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Key findings

Nearly one in 10 Dutch older adults using medications had a high anticholinergic/sedative load. We identified four subgroups (classes) of patients based on their most likely used type of CNS‐active medications, described as patients using combined psycholeptic/psychoanaleptic medication, analgesics, antiepileptic medication, and patients using anti‐Parkinson medications.

4.2. Strengths and limitations

This was an innovative study identifying patients with high anticholinergic/sedative loads and providing insight into the type of medication contributing to this high load in individual patients. A key strength of this study is the use of LCA to explore patterns of anticholinergic/sedative medication use in a large nation‐wide study sample of older adults. The following limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, we analysed medications with a usage date within the study period of 1 month. This included not only medications taken for the whole period but also medications taken for only part of the month. This may have overestimated the total daily anticholinergic/sedative load for an individual, while medications dispensed “over the counter” were not available. This may have led to an underestimation of the anticholinergic/sedative load. Second, like in other pharmacoepidemiological studies using similar data sources, medication‐dispensing data are an approximation of actual medication use.17 Third, we classified medications by its ATC code level 2. We did not have access to details on patient comorbidities or the indications for medications included in our analysis. For example, (national) prescribing guidelines for neuropathic pain recommend medications for a range of different therapeutic subgroups, such as tricyclic antidepressants (ATC code N06AA) and antiepileptics (ATC code N03).18, 19 Furthermore, antiepileptic medications are prescribed for behavioural disorders.20 Within the group of antiepileptic medication users, we therefore could not distinguish between patients with epilepsy, neuropathic pain, or behavioural disorders. Finally, there is no international consensus about which medications have anticholinergic/sedative properties.21 A first attempt has been the systematic review on anticholinergic medications where we based our list of anticholinergic medications on.6 For sedative medications, this is lacking. While anticholinergic effects are a result of muscarinic receptor blocking,5 different pharmacological pathways lead to sedation, of which most pathways are still unknown.22 Therefore, we based our list of sedative medications on a systematic analysis of relevant frequently reported (side) effects in relevant reference sources. More work needs to be done, to come to an evidence‐based list of medications. This may limit the comparability of studies using the DBI.23 Furthermore, although anticholinergic and sedative medications are pharmacologically different, they have similar negative consequences. 2 This is why we quantified the combined load of anticholinergic and sedative medications. Other tools are available, which were restricted to anticholinergic medications, amongst those, one that shows promising results.24, 25

4.3. Interpretations and other studies

We found that in the population of Dutch older adults using medications, about one third used at least one anticholinergic/sedative medication and one in 10 had a high anticholinergic/sedative load. This is in line with other studies,26, 27 but exact numbers are difficult to compare because of differences in study populations and definitions used. Most patients in our study used psycholeptic and psychoanaleptic medications (class 1). While the use of these medications may be appropriate for some older adults, potentially inappropriate use of these medications has been widely reported.28 We distinguished a subgroup of patients with pain, using strong opioids (class 2). Yet, antiepileptic medications are also prescribed for the management of pain, particularly neuropathic pain,18, 19 but are not used by patients in class 2. As such, the class of antiepileptic users (class 3) may also include a considerable number of patients treated for pain. In particular, this could be the group of 26.6% of patients in this class using opioids. But despite this probable overlap, antiepileptic users were more likely to be male compared with the total study population, suggesting that most antiepileptic medications were used to manage epilepsy rather than other symptoms or diseases, as epilepsy is more common in men than women aged 65 years and older.29 We found a high proportion of males in the anti‐Parkinson medication class (class 4), which is also in line with the national prevalence of Parkinson's disease.30 The small number of antipsychotics in this class might indicate that it includes predominantly patients suffering from Parkinson's disease, as most antipsychotics are contraindicated in these patients.31 The small number of antipsychotics in this class may actually reflect patients who have drug‐induced Parkinsonism caused by antipsychotics.32

4.4. Implications for practice

Our findings give insight into the extent of anticholinergic/sedative medication use and the different types of medications used that contribute to a high anticholinergic/sedative load. We found that the majority of patients with a high anticholinergic/sedative load used combinations of psycholeptic and psychoanaleptic medications. These medications are often inappropriately used among older adults, increasing the risk of medication related harm, such as falls and hospitalisation, and therefore should be considered for deprescribing where appropriate.33, 34 So far however, few interventions have been effective in reducing a patient's anticholinergic/sedative load. In our recent randomised controlled trial, we found that medication reviews were not effective in reducing a high anticholinergic/sedative load among older community‐dwelling patients. As a consequence, different strategies for identifying those patients who are in greatest need for medication optimisation and who could benefit from intervention are needed.35 Targeting specific anticholinergic/sedative medications and tailoring interventions to specific subgroups of patients might be the most successful strategy to reduce the overall anticholinergic/sedative load.

5. CONCLUSIONS

A large proportion of older adults in the Netherlands had a high anticholinergic/sedative load. Four distinct subgroups were identified. Interventions aiming at reducing the overall anticholinergic/sedative load should be tailored to these subgroups.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The authors state that no ethical approval was needed.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.W., K.T., and H.v.d.M. initiated the study, and H.v.d.M., L.P., H.W., M.T., and F.G. contributed to the study conception and design. F.G. obtained data. H.v.d.M., H.W., L.P., and K.T. reviewed the study parameters and contributed to the analysis plan. H.v.d.M. and H.W. did the statistical analysis with input from K.T. and L.P. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results. H.v.d.M. drafted the manuscript. All the authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

FUNDING

None.

Supporting information

Appendix Table 1: Top 10 used anticholinergic/sedative medications per class identified with the latent class analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to the Royal Dutch Pharmacists Association and, in particular, Ton Schalk from the Foundation for Pharmaceutical Statistics for facilitating this research.

van der Meer HG, Taxis K, Teichert M, Griens F, Pont LG, Wouters H. Anticholinergic and sedative medication use in older community‐dwelling people: A national population study in the Netherlands. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28:315–321. 10.1002/pds.4698

Prior postings and presentations: Oral presentation at the 34th International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic Risk Management, August 22 to 26 2018, in Prague, Czech Republic.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fox C, Smith T, Maidment I, et al. Effect of medications with anti‐cholinergic properties on cognitive function, delirium, physical function and mortality: A systematic review. Age Ageing. 2014;43(5):604‐615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Park H, Satoh H, Miki A, Urushihara H, Sawada Y. Medications associated with falls in older people: Systematic review of publications from a recent 5‐year period. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71(12):1429‐1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holvast F, van Hattem BA, Sinnige J, et al. Late‐life depression and the association with multimorbidity and polypharmacy: A cross‐sectional study. Fam Pract. 2017;34(5):539‐545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bell JS, Mezrani C, Blacker N, et al. Anticholinergic and sedative medicines—Prescribing considerations for people with dementia. Aust Fam Physician. 2012;41(1‐2):45‐49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nishtala PS, Salahudeen MS, Hilmer SN. Anticholinergics: Theoretical and clinical overview. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15(6):753‐768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Duran CE, Azermai M, Vander Stichele RH. Systematic review of anticholinergic risk scales in older adults. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(7):1485‐1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Taxis K, Kochen S, Wouters H, et al. Cross‐national comparison of medication use in Australian and Dutch nursing homes. Age Ageing. 2017;46(2):320‐323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equ Modeling. 2007;14(4):535‐569. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Foundation for pharmaceutical statistics: Foundation for pharmaceutical statistics. Available at https://www.sfk.nl/english. Accessed April, 2018.

- 10. Buurma H, Bouvy ML, De Smet PA, Floor‐Schreudering A, Leufkens HG, Egberts AC. Prevalence and determinants of pharmacy shopping behaviour. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2008;33(1):17‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hilmer SN, Mager DE, Simonsick EM, et al. A drug burden index to define the functional burden of medications in older people. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(8):781‐787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wouters H, van der Meer H, Taxis K. Quantification of anticholinergic and sedative drug load with the drug burden index: A review of outcomes and methodological quality of studies. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73(3):257‐266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Farmacotherapeutisch Kompas: Dutch pharmacotherapeutic reference source. Available at https://www.farmacotherapeutischkompas.nl/. Accessed April, 2018.

- 14. KNMP Kennisbank: Dutch pharmacotherapeutic reference source. Available at https://kennisbank.knmp.nl/. Accessed April, 2018.

- 15. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology: ATC/DDD index. Available at https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/. Accessed March, 2018.

- 16. Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus User's guide. 8th ed. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sodihardjo‐Yuen F, van Dijk L, Wensing M, De Smet PAGM, Teichert M. Use of pharmacy dispensing data to measure adherence and identify nonadherence with oral hypoglycemic agents. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73(2):205‐213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Verenso: Multidisciplinary guideline pain in older people. Available at https://www.verenso.nl/_asset/_public/Richtlijnen_kwaliteit/richtlijnen/database/VER‐003‐32‐Richtlijn‐Pijn‐deel1‐v5LR.pdf. Accessed May, 2018.

- 19. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): Neuropathic pain in adults. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg173/resources/neuropathic‐pain‐in‐adults‐pharmacological‐management‐in‐nonspecialist‐settings‐pdf‐35109750554053. Accessed May, 2018.

- 20. National Healthcare Institute (Zorginstituut Nederland): Anti‐epileptics. Available at https://www.farmacotherapeutischkompas.nl/bladeren/groepsteksten/anti_epileptica. Accessed September, 2018.

- 21. Pont LG, Nielen JT, McLachlan AJ, et al. Measuring anticholinergic drug exposure in older community‐dwelling australian men: A comparison of four different measures. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(5):1169‐1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yu X, Franks NP, Wisden W. Sleep and sedative states induced by targeting the histamine and noradrenergic systems. Front Neural Circuits. 2018;12:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Faure R, Dauphinot V, Krolak‐Salmon P, Mouchoux C. A standard international version of the drug burden index for cross‐national comparison of the functional burden of medications in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(7):1227‐1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wauters M, Klamer T, Elseviers M, et al. Anticholinergic exposure in a cohort of adults aged 80 years and over: Associations of the MARANTE scale with mortality and hospitalization. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;120(6):591‐600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Klamer TT, Wauters M, Azermai M, et al. A novel scale linking potency and dosage to estimate anticholinergic exposure in older adults: The muscarinic acetylcholinergic receptor ANTagonist exposure scale. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;120(6):582‐590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Hartikainen S, et al. Impact of high risk drug use on hospitalization and mortality in older people with and without alzheimer's disease: A national population cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e83224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wilson NM, Hilmer SN, March LM, et al. Associations between drug burden index and physical function in older people in residential aged care facilities. Age Ageing. 2010;39(4):503‐507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tommelein E, Mehuys E, Petrovic M, Somers A, Colin P, Boussery K. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in community‐dwelling older people across europe: A systematic literature review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71(12):1415‐1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. National Institute of Public Health and the Environment: Prevalence of epilepsy in general practice. Available at https://www.volksgezondheidenzorg.info/onderwerp/epilepsie/cijfers‐context/huidige‐situatie. Accessed May, 2018.

- 30. National Institute of Public Health and the Environment: Prevalence of parkinson's disease in general practice. Available at https://www.volksgezondheidenzorg.info/onderwerp/ziekte‐van‐parkinson/cijfers‐context/huidige‐situatie. Accessed May, 2018.

- 31. Divac N, Stojanovic R, Savi Vujovic K, Medic B, Damjanovic A, Prostran M. The efficacy and safety of antipsychotic medications in the treatment of psychosis in patients with parkinson's disease. Behav Neurol. 2016;2016:4938154:1‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lopez‐Sendon J, Mena MA, de Yebenes JG. Drug‐induced parkinsonism. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2013;12(4):487‐496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. By the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American geriatrics society 2015 updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227‐2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. O'Mahony D, O'Sullivan D, Byrne S, O'Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213‐218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. van der Meer HG, Wouters H, Pras N, Taxis K. Reducing the anticholinergic and sedative load in older patients on polypharmacy by pharmacist‐led medication review: A randomized controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e019042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix Table 1: Top 10 used anticholinergic/sedative medications per class identified with the latent class analysis.