Abstract

Many individuals with autism report generally low quality of life (QoL). Identifying predictors for pathways underlying this outcome is an urgent priority. We aim to examine multivariate patterns that predict later subjective and objective QoL in autistic individuals. Autistic characteristics, comorbid complaints, aspects of daily functioning, and demographics were assessed online in a 2‐year longitudinal study with 598 autistic adults. Regression trees were fitted to baseline data to identify factors that could predict QoL at follow‐up. We found that sleep problems are an important predictor of later subjective QoL, while the subjective experience of a person's societal contribution is important when it comes to predicting the level of daily activities. Sleep problems are the most important predictor of QoL in autistic adults and may offer an important treatment target for improving QoL. Our results additionally suggest that social satisfaction can buffer this association. Autism Research 2019, 12: 794–801. © 2019 International Society for Autism Research, Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Lay Summary

Many individuals with autism report generally low quality of life (QoL). In this study, we looked at factors that predict long‐term QoL and found that sleep problems are highly influential. Our results additionally suggest that social satisfaction can buffer this influence. These findings suggest that sleep and social satisfaction could be monitored to increase QoL in autistic adults.

Keywords: autistic adults, quality of life, regression tree analysis, sleep problems, large‐scale longitudinal data

Introduction

Low quality of life (QoL) is a primary problem in autistic adults [Van Heijst & Geurts, 2015; Ayres et al., 2017] and improving scientific insight into this phenomenon is urgent. Our current understanding of longitudinal trajectories of QoL in autistic adults, however, remains limited [Drmic, Szatmari, & Volkmar, 2018]. This is the case for at least two reasons.

The first concerns the lack of good data. Although the past decade has featured intensive investigation into the identification of characteristics involved in outcomes of autistic adults, reported findings are variable and sometimes even contradictory [e.g., Moss, Mandy, & Howlin, 2017; Van Heijst & Geurts, 2015]. Additionally, existing studies were mostly cross‐sectional in nature [but see Moss et al., 2017; Woodman, Smith, Greenberg, & Mailick, 2016] and focused on the relationship between specific characteristics and “objective” QoL (e.g., independent living or the level of employment) instead of subjective QoL, that is, the subjective evaluation of one's QoL. This focus risks neglecting the lived experience of autistic adults as an equally important source of information. Thus, currently available data omit important aspects of QoL or lack longitudinal information necessary to identify predictors of QoL. The autism research community has therefore advocated the collection of large‐scale longitudinal data on this population (see, e.g., goals of the EU‐AIMS Longitudinal European Autism Project) to illuminate the relationship between behavioral measures, demographics, and later QoL in autistic adults.

A second problematic issue is that impaired QoL, as observed in autistic adults [Moss et al., 2017], exhibits a highly complicated and heterogeneous causal background: a host of cognitive, social, environmental, biological, and health‐related variables likely contribute to lower QoL, and do so in multiple time‐dependent patterns of reciprocal interactions. Given this highly complex etiology, identifying predictors for pathways underlying QoL in the autism population requires the use of advanced multivariate statistical methodology that so far has not been employed.

The current study meets the above problems by applying a data‐driven approach to uncovering subtypes in multivariate patterns associated with longitudinal changes in QoL. The analysis is executed on unique longitudinal data from the Netherlands Autism Register (NAR). The NAR is a register that contains repeated assessments of behavioral traits, life events, and health history of a comparatively large sample of autistic individuals. Using a data‐driven methodology in this cohort, which covers the entire adult lifespan (17–83 years), we investigate whether we can identify characteristics that predict later QoL in autistic adults from patterns in autistic characteristics, comorbid complaints, aspects of daily functioning, and demographics.

Methods

Participants

Participants were volunteers of the NAR (www.nederlandsautismeregister.nl/english/) which is a large longitudinal database that collects information from over 2,000 autistic individuals with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnosis of DSM‐IV or DSM‐5 on a broad range of health history, life events, and psychological traits [Begeer et al., 2013; Burke, Koot, & Begeer, 2015; Deserno et al., 2015]. Participants are invited to complete a battery of questionnaires on an annual basis. In the present study, we included N = 598 participants for the analysis with subjective QoL as an outcome variable and N = 544 for the analysis with objective QoL as an outcome variable. These sample sizes differ because the statistical analyses we chose do not allow for missing values in the outcome variable. All participants completed at least two waves of the NAR assessment themselves (i.e., instead of a proxy) and reported an ASD diagnosis. Participants self‐reported the result of their most recent IQ test, with 40% missingness (4% reported IQ <70, 17% reports IQ between 70 and 115, 39% reports IQ >115). While all participants confirmed having a clinical diagnosis and disclosed when, where, by whom, and how (ADOS/ADI‐R) they received their diagnosis, we did not conduct additional diagnostic assessments ourselves. We were able to obtain official proof of the individual diagnosis in a third of the cases and found similar overall patterns of function in this group compared to the rest of the sample. Analyses in the present manuscript used data from two waves of data collection spanning 2 years (2015–2017) and focuses on multiple potential predictors. The sample included twice as many participants as comparable studies with similar analyses [e.g., Lever et al., 2015].

Measures

Selection procedure

We selected a set of potential predictors covering autism‐specific characteristics, comorbid problems, aspects of daily functioning, and demographics. For the analysis, we selected only those 25 predictors with less than 40% missing values. As we aimed to cover as many behavioral facets of autism as possible, we chose to include all standardized questionnaires in the NAR study. In addition, our choices regarding the measures being used were motivated by three factors. First, we based our choice on results of previous studies in which we mapped the multivariate system of predictors of QoL [Deserno et al., 2015]. We selected those measures that these networks showed to be central and directly related to QoL in the autistic population. Second, we involved an expert panel of autistic adults, parents of autistic children, and clinicians working with people with autism in making these choices. Third, we avoided variables for which there were too few available observations within the NAR data, that is., variables with many missing data points.

Within the NAR, not all variables are assessed at each assessment wave. Ideally, the time window between the measurement of each of the predictors and QoL assessments would be similar. However, differences between waves resulted in a set of predictors from both T0 and T1 within the current study. Our choice to include predictors from both time points was driven by the interest in each variable's ability to predict QoL at T2, regardless of whether they were measured at T0 or T1. There could be causal relationships between variables measured at T0 and T1, but these were not included in the current model.

Included measures

First, we included the five subscales of the Autism Quotient [Baron‐Cohen, Wheelwright, Skinner, Martin, & Clubley, 2001], assessing communication, social skills, imagination, attention to detail, and attention switching. Second, we included the five subscales of the Sensory Perception Quotient [Tavassoli, Hoekstra, & Baron‐Cohen, 2014], that is, vision, hearing, touch, smell, and taste. Third, we added the seven items of the Insomnia Severity Index [Bastien, Vallières, & Morin, 2001], that is, severity of sleep‐onset and sleep‐maintenance difficulties, satisfaction with current sleep pattern, interference with daily functioning, noticeability of impairment attributed to the sleep problem, and the degree of distress caused by the sleep problem. Participants were asked to rate these items on a 5‐point Likert scale: (a) not at all, (b) a little, (c) somewhat, (d) much, and (e) very much.

All three questionnaires have been assessed within the 2015 wave of the NAR study, here referred to as T0. We furthermore selected a set of eight single items to cover a wide range of domains related to QoL [Mason et al., 2018; Deserno et al., 2015], such as comorbid mental and physical diagnoses, subjectively perceived societal contribution, educational context, living situation, satisfaction with social contacts, gender, and age. These domains were all separately assessed within the 2016 wave of the NAR study, here referred to as T1. Subjective QoL was measured with an item assessing how satisfied participants were with their own life [Begeer et al., 2017; Bartels & Boomsma, 2009]. This item was answered on a 5‐point Likert scale: (a) always or almost always happy, (b) more happy than unhappy, (c) equally happy and unhappy, (d) more unhappy than happy, or (e) always or almost always unhappy. We selected an item assessing level of daily activities as an operationalization of objective QoL based on a 4‐point scale: (a) unemployed, (b) supported daily activities, (c) unpaid daily activities, and (d) paid daily activities. Data on these items were available at multiple time points. To use the longitudinal information about autistic adults, we ran the analyses with assessments of these outcome variables at a later wave (i.e., 2017, here referred to as T2). In other words, we investigated whether characteristics at T0 and T1 predict someone's response value to (a) satisfaction with one's life at T2 or (b) level of daily activities at T2.

Statistical Analyses

To investigate whether we could predict inter‐individual differences in QoL at a later measurement occasion, we used regression trees [Strobl, Malley, & Tutz, 2009]. Classification and regression trees have been proposed as a data‐analytic tool for (theory‐guided) exploration of empirical data. Partitioning of the covariate space (of all predictor variables) is used to generate a final set of predictor variables and cutoff values within those predictors to derive non‐overlapping groups of subjects with similar values of a selected response variable. Group membership can then be determined by running through the hierarchy of decision nodes, which are defined as those predictors that best explain heterogeneity in the cohort. This is based on a so‐called greedy approach, which means that the best split is made at each step, rather than taking future steps into account. Each split in the regression tree is based on the idea of impurity reduction, selecting the exact cutoff value in the parent node that maximizes the isolation of subjects with different response patterns in the two daughter nodes.

We set stopping criteria in estimating a regression relationship between every two variables based on multiplicity adjusted (Bonferroni) P‐values and required P < 0.001 for a split to be implemented. Regression tree analyses were performed using the R (version 3.4.0) package “party” [Hothorn, Hornik, & Zeileis, 2006]. Please note that the regression tree algorithm used here employs P‐values to select predictors, rather than either initially selecting many predictor variables and pruning the tree later or tweaking a variable selection parameter using cross‐validation. We did perform an additional check with the exact same predictors using a random forest algorithm to estimate the stability of the regression tree solution with the R‐package “randomForest” [Liaw & Wiener, 2002]. Random forests are sets of independently grown regression trees, where each tree is weighted in order to calculate each predictor's importance.

Results1

Subjective QoL

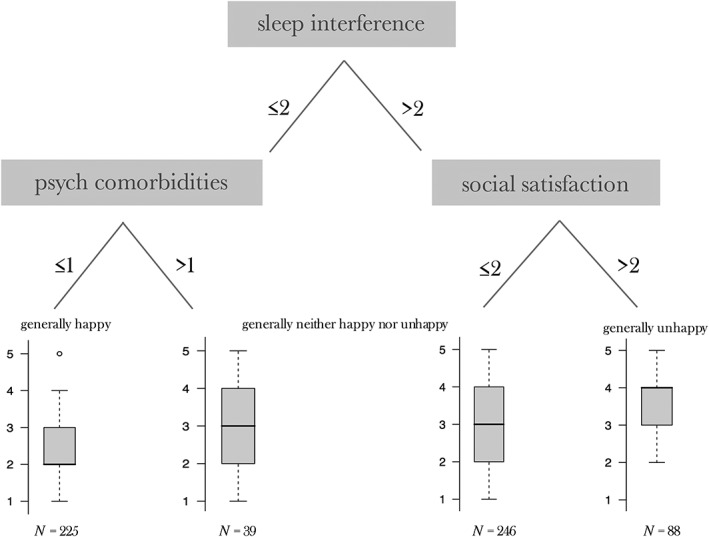

Exploratory regression tree analyses yielded four subgroups, with distinct patterns of values on the predictor and outcome variables. The first subgroup is generally happy (subgroup 1, N = 225, 38%). Two subgroups are generally neither happy nor unhappy (subgroups 2 and 3, N = 39 and 246, 6% and 41%, respectively). The last subgroup is generally unhappy (subgroup 4, N = 88, 15%). The first split shows that having sleep problems that interfere with daily functioning is the most important predictor for different response values on subjective QoL over time. In other words, sleep problems separate a subgroup of participants who were generally unhappy to neither happy nor unhappy from those that were neither happy nor unhappy to generally happy. The decision nodes are the degree to which your sleep problems interfere with your daily functioning, the number of comorbid (psychological) diagnoses, and social satisfaction. The stability of these decision nodes was underlined by the results of the random forest algorithm: All three variables ranked among the four most important predictors (with the addition of the degree to which you worry about your sleep problems) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Regression tree based on the NAR sample, grown with a requirement of P < 0.001 for a split to be implemented. The response node in this tree is the five‐point scale of the satisfaction with one's life item at a later assessment wave of the NAR study. The P‐values stem from binary association tests for variable and cutoff value selection. A low P‐value equals high impurity reduction.

Specifically, the first split divided the sample into two daughter nodes based on whether they felt their sleep problems were either not at all/a little/somewhat interfering (≤2) or much/very much interfering (>2). For the severe interference group, a second split was based on whether they reported to be satisfied/neutral (≤2) or unsatisfied about their social contacts (>2). Among those who experienced mild or no interference through their sleep problems a second split was made based on whether they reported no or at least one comorbid psychopathological condition. In summary, we found four groups: (a) a subgroup of generally unhappy participants with sleep problems and low social satisfaction, (b) a subgroup of generally happy participants without sleep problems and comorbid disorders and two subgroups of generally neither happy nor unhappy participants who (c) either report sleep problems, but are socially satisfied, or (d) do not report sleep problems, but do report comorbid disorders. Table 1 depicts general descriptives for the whole sample.

Table 1.

Descriptives for All Autistic Adults in the NAR Cohort Participating at T0, T1, and T2

| Variable | Descriptives | Subjective QoLa (N = 598) | Objective QoL (N = 544) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | Mean/SD/range | 42.8/15.5/17–83 | 44.2/14.5/17–82 |

| Gender | Male/female | 310/288 | 270/274 |

| Employment | % Unemployed/% supported/% unpaid/% paid | 20%/11%/27%/41% | 17%/13%/30%/40% |

| AQb | Mean/SD/range | 82.6/11.7/50–110 | 82.5/11.9/50–110 |

| SPQc | Mean/SD/range | 44.4/15.4/3–93 | 44.3/15.5/3–93 |

| ISId | Mean/SD/range | 9.2/5.9/0–24 | 9.2/5.9/0–24 |

QoL = quality of life.

AQ = autism quotient.

SPQ = sensory perception quotient.

ISI = insomnia severity index.

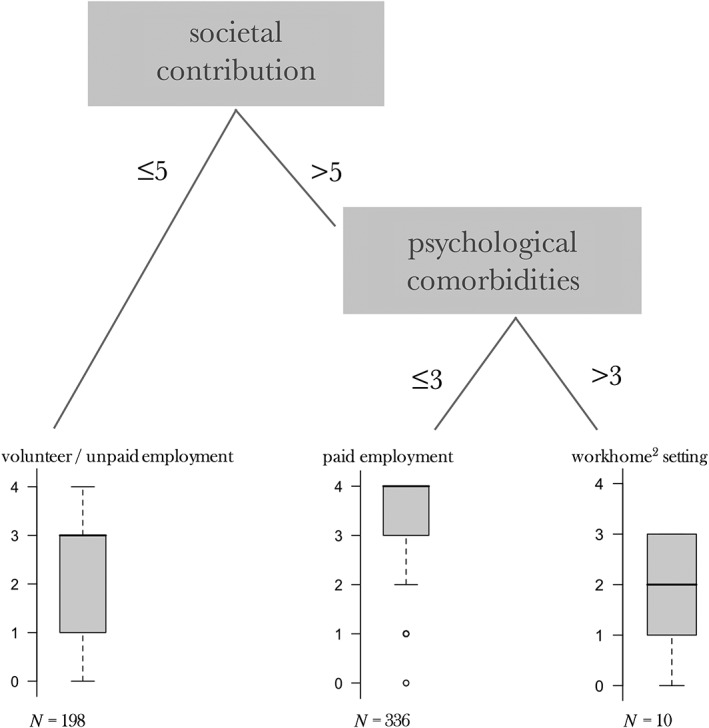

Objective QoL

Exploratory regression tree analyses yielded a tree with two decision nodes (see Fig. 2), resulting in three terminal nodes representing three response values: a subgroup of participants who do work but in an unpaid employment setting, for example, as an intern or volunteer (N = 196); a subgroup of participants who work in a paid employment setting (N = 336); and a smaller subgroup of participants who work in a so‐called workhome2 setting (N = 10). The first decision node (i.e., first split) shows that an individual's subjectively perceived societal contribution is the most important predictor for different response values on their level of daily activities 1 year later. The number of psychological comorbidities is the second decision node. The random forest algorithm, too, ranked these variables as most important predictors for an individual's level of daily activities.

Figure 2.

Regression tree based on the NAR sample, grown with a requirement of P < 0.001 for a split to be implemented. The response node in this tree is the five‐point scale of level of daily activities at a later assessment wave of the NAR study. The P‐values stem from binary association tests for variable and cutoff value selection. A low P‐value equals high impurity reduction.

Specifically, the first split separated the autistic adults in two subgroups: those that have the feeling they are unsuccessful in their contribution to society (≤5) or those that feel successful in their societal contribution (>5). Among those that evaluated themselves as successful in their societal contribution, the regression tree analyses resulted in a second split based on whether they reported three or less than three comorbid psychological diagnoses or more than three comorbid diagnoses.

Discussion

This study shows that experiencing sleep problems is associated with lower later subjective QoL, while the feeling that one cannot contribute to society and reporting psychological comorbidities predict a lower level of daily activities 1 year later.

The finding that sleep problems are highly predictive of subjective QoL resonates with the fact that the role of sleep in autism has become a subject of recent attention in the scientific literature. Between 44 and 86% of children with autism have difficulty falling or staying asleep [Maxwell‐Horn & Malow, 2017; Richdale & Schreck, 2009], which makes sleep problems one of the most urgent concerns in daily life with autism. The current study underscores the importance of these problems as determinants of future QoL. Simultaneously, our results regarding “objective” QoL highlight the importance of establishing an individualized context where autistic adults feel they can contribute to society. Earlier research has pointed in a similar direction: creating a professional context focusing on strengths and interests of autistic individuals boosts self‐esteem and social engagement [Diener et al., 2015; Carter et al., 2013], which, in turn, might help individuals to reach their full potential in meaningful work.

A second important finding in our study contrasts with what one might expect: the severity of autistic symptoms was not selected in the predictive model for QoL. Thus, although it is often hypothesized in the literature that the severity of autistic symptoms predicts later outcome, autism‐specific characteristic did not appear to be a strong predictor for future QoL in this autistic sample. Further studies are necessary to replicate this conclusion, which, if correct, is of considerable importance.

Third, we found that 38% reported that they are generally happy and 15% of the participants actually reported that they are generally unhappy, which seems in contrast with the starting premise of this study that the majority of autistic adults reports a low QoL. However, previous studies have reported similar observations suggesting that measures focusing on subjective QoL instead of objective outcome measures do not show a substantial difference in self‐reported QoL for autistic individuals compared to the general population [Moss et al., 2017; Hong, Bishop‐Fitzpatrick, Smith, Greenberg, & Mailick, 2016].

The clinical utility of multivariate analyses in outcome ultimately rests on their value in helping guide intervention decisions. Since our data‐driven approach yields groups of individuals that share their experience of subjective QoL or their objective QoL, it might offer one way forward for considering new targets with the aim to improve the QoL of autistic adults. It might very well be that comorbid conditions such as depression or anxiety funnel the relationship between autism and QoL. Both conditions are often reported to be triggered by sleep problems in typically developing samples [Alvaro, Roberts, & Harris, 2013]. Our findings highlight the importance of comorbid conditions for both subjective QoL and level of daily activities. The latter has been related to poor sleep in autistic adults in a recently published report [Baker, Richdale, & Hazi, 2018]. In addition, although our findings are correlational, sleep problems may in fact be causally associated with autism symptoms, rendering possibilities for causal intervention. A recent study suggested a relationship between parent‐reported reduced amounts of sleep and increased severity of the classic difficulties associated with autism (social/communication impairment and repetitive behaviors), maladaptive behaviors, and other psychiatric comorbidities in children with autism [Veatch et al., 2017]. The directionality of this relationship is still to be determined and would require large, well‐controlled studies that investigate subsets of autistic participants based on their sleep issues. The results of our study, however, suggest that intervening on the daily consequences of sleep problems and getting back on a regular sleeping schedule might improve QoL for autistic individuals. In addition, our finding that psychological comorbidities matter for the QoL in autistic adults is in line with current care guidelines highlighting that we should treat symptoms of comorbid conditions rather than autism characteristics.

Limitations

One limitation of our study is that we were constrained to a specific set of symptom data and environmental factors for determination of multivariate pathways. For example, the wide range of scores regarding QoL in some subgroups suggest that there might be other predictors, which could result in another informative subgroup split. Moreover, recent studies have highlighted the importance of validating existing measures for outcome in the autism population [McConachie et al., 2018; Ayres et al., 2017; Cottenceau et al., 2012] so that we can make sure study results inform us on appropriate targets. Future research should replicate these findings in an independent sample, expanding the sample size and input features to establish a valid and clinically viable taxonomy for QoL in ASD.

A second limitation might be that often individuals have a long‐term level of happiness to which they always spontaneously return after life events of either valence [Diener & Diener, 1996]. This has implications for the assessment of change in happiness‐related measures in any population. In order to test detailed temporal dynamics, one would need a large number of time points with shorter time intervals. Future research on QoL in autistic adults could explore what impact the identified factors have on the short‐term dynamics of QoL with, for example, experience sampling data. Nonetheless, our results provide first insights that can guide future research on predictors of subjective and objective QoL.

Third, it is important to mention that we were limited by the online survey context, resulting in an inability to directly verify diagnosis and IQ of the participating individuals. Most individuals, however, were able to provide proof of their official diagnosis upon request. In addition, self‐reported diagnosis in an online autism registry has been shown to highly correlate with independently verified diagnosis [Daniels et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2010]. This does not hold for self‐reported IQ‐scores, which inevitably result in less reliable estimates of cognitive ability than a valid assessment would do [Paulhus et al., 1998].

Fourth, the study sample is characterized by a large age range (17–83). It is unlikely that variables such as employment will have similar workings for individuals on the outer edges of the age spectrum versus the mid‐aged individuals. We would, however, expect the partitioning analysis to show such subgroups if relevant to QoL: that is, if the workings of, for example, paid employment would be more/less relevant to a specific age‐group in this sample, the regression tree analysis would have picked up on this. It aims at finding a nonlinear classification, that is, nonoverlapping groups of subjects with similar values of a selected response variable. It might still be that age is a relevant predictor explaining just a smaller amount of heterogeneity in the cohort. When partitioning the covariate space, however, age does not show up in the top hierarchy of predictors for neither QoL nor the level of daily activities a subgroup has.

In conclusion, this study illustrates how regression tree analyses can be utilized to inform us on what factors should be targeted when aiming to increase QoL in autistic individuals. Our results specifically highlight the importance of sleep problems for subjective QoL, the presence of comorbid diagnoses, and the feeling that one can contribute to society for objective QoL. Using the identified paths, we can further investigate whether targeting malleable factors, such as sleep quality, can indeed improve the lifespan QoL of autistic adults.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding Information

Denny Borsboom is supported by ERC Consolidator Grant No. 647209. Hilde Geurts was supported by the NWO VICI Grant No. 453‐16‐006. This research project is supported by ZonMW Grant No. 70‐73400‐98‐002.

Author Contributions

Data collection was supervised by S. Begeer and K. Mataw. M. K. Deserno performed the data analysis and interpretation under the supervision of D. Borsboom, S. Begeer, J. A. Agelink van Rentergem, and H. M. Geurts. M. K. Deserno drafted the manuscript and J. A. Agelink van Rentergem, D. Borsboom, S. Begeer, and H. M. Geurts provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ellen de Groot, Theo Beskers, Paul Blankert, Peter Boer, Jolanda Lancee, Teresa Zwerver, and Robert van der Gun for their input during our feedback panel sessions on this study.

Endnotes

To improve the interpretation of the reported results we discussed the selection of predictors and all findings with help of a feedback panel consisting of autistic adults and professionals working with people in ASD.

In the Netherlands, “workhome” refers to a supported living environment that also incorporates a supported work environment.

References

- Alvaro, P. K. , Roberts, R. M. , & Harris, J. K. (2013). A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep, 36(7), 1059–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayres, M. , Parr, J. R. , Rodgers, J. , Mason, D. , Avery, L. , & Flynn, D. (2017). A systematic review of quality of life of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism, 22(7), 774–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, E. K. , Richdale, A. L. , & Hazi, A. (2018). Employment status is related to sleep problems in adults with autism spectrum disorder and no comorbid intellectual impairment. Autism, 23(2), 531–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron‐Cohen, S. , Wheelwright, S. , Skinner, R. , Martin, J. , & Clubley, E. (2001). The autism‐ spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high‐functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(1), 5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, M. , & Boomsma, D. I. (2009). Born to be happy? The etiology of subjective well‐being. Behavior Genetics, 39(6), 605–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastien, C. H. , Vallières, A. , & Morin, C. M. (2001). Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Medicine, 2(4), 297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begeer, S. , Mandell, D. , Wijnker‐Holmes, B. , Venderbosch, S. , Rem, D. , Stekelenburg, F. , & Koot, H. M. (2013). Sex differences in the timing of identification among children and adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(5), 1151–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begeer, S. , Ma, Y. , Koot, H. M. , Wierda, M. , van Beijsterveldt, C. T. , Boomsma, D. I. , & Bartels, M. (2017). Brief Report: Influence of gender and age on parent reported subjective well‐being in children with and without autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 35, 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, D. A. , Koot, H. M. , & Begeer, S. (2015). Seen but not heard: School‐based professionals' oversight of autism in children from ethnic minority groups. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 9, 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, E. W. , Harvey, M. N. , Taylor, J. L. , & Gotham, K. (2013). Connecting youth and young adults with autism spectrum disorders to community life. Psychology in the Schools, 50(9), 888–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottenceau, H. , Roux, S. , Blanc, R. , Lenoir, P. , Bonnet‐Brilhault, F. , & Barthélémy, C. (2012). Quality of life of adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: Comparison to adolescents with diabetes. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 21(5), 289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, A. M. , Rosenberg, R. E. , Anderson, C. , Law, J. K. , Marvin, A. R. , & Law, P. A. (2012). Verification of parent‐report of child autism spectrum disorder diagnosis to a web‐based autism registry. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(2), 257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deserno, M. K. , Borsboom, D. , Begeer, S. , & Geurts, H. M. (2015). Multicausal systems ask for multicausal approaches: A network perspective on subjective well‐being in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 21(8), 960–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. , & Diener, C. (1996). Most people are happy. Psychological Science, 7(3), 181–185. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, M. L. , Anderson, L. , Wright, C. A. , & Dunn, M. L. (2015). Sibling relationships of children with autism spectrum disorder in the context of everyday life and a strength‐based program. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(4), 1060–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Drmic, I. E. , Szatmari, P. , & Volkmar, F. (2018). Life course health development in autism spectrum disorders In Handbook of life course health development (pp. 237–274). Cham: Springer. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J. , Bishop‐Fitzpatrick, L. , Smith, L. E. , Greenberg, J. S. , & Mailick, M. R. (2016). Factors associated with subjective quality of life of adults with autism spectrum disorder: Self‐report versus maternal reports. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(4), 1368–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn, T. , Hornik, K. , & Zeileis, A. (2006). Unbiased recursive partitioning: A conditional inference framework. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 15(3), 651–674. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H. , Marvin, A. R. , Watson, T. , Piggot, J. , Law, J. K. , Law, P. A. , … Nelson, S. F. (2010). Accuracy of phenotyping of autistic children based on internet implemented parent report. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics, 153(6), 1119–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lever, A. G. , Werkle‐Bergner, M. , Brandmaier, A. M. , Ridderinkhof, K. R. , & Geurts, H. M. (2015). Atypical working memory decline across the adult lifespan in autism spectrum disorder? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(4), 1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw, A. , & Wiener, M. (2002). Classification and Regression by randomForest. R News, 2(3), 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, D. , McConachie, H. , Garland, D. , Petrou, A. , Rodgers, J. , & Parr, J. R. (2018). Predictors of quality of life for autistic adults. Autism Research, 11, 1138–1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell‐Horn, A. , & Malow, B. A. (2017). Sleep in autism. Seminars in Neurology, 37(4), 413–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConachie, H. , Mason, D. , Parr, J. R. , Garland, D. , Wilson, C. , & Rodgers, J. (2018). Enhancing the validity of a quality of life measure for autistic people. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(5), 1596–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss, P. , Mandy, W. , & Howlin, P. (2017). Child and adult factors related to quality of life in adults with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(6), 1830–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus, D. L. , Lysy, D. C. , & Yik, M. S. (1998). Self‐report measures of intelligence: Are they useful as proxy IQ tests? Journal of Iersonality, 66(4), 525‐554. [Google Scholar]

- Richdale, A. L. , & Schreck, K. A. (2009). Sleep problems in autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, nature, & possible biopsychosocial aetiologies. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 13(6), 403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobl, C. , Malley, J. , & Tutz, G. (2009). An introduction to recursive partitioning: Rationale, application, and characteristics of classification and regression trees, bagging, and random forests. Psychological Methods, 14(4), 323–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavassoli, T. , Hoekstra, R. A. , & Baron‐Cohen, S. (2014). The sensory perception quotient (SPQ): Development and validation of a new sensory questionnaire for adults with and without autism. Molecular Autism, 5(1), 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Heijst, B. F. C. , & Geurts, H. M. (2015). Quality of life in autism across the lifespan: A meta‐analysis. Autism, 19(2), 158–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veatch, O. J. , Sutcliffe, J. S. , Warren, Z. E. , Keenan, B. T. , Potter, M. H. , & Malow, B. A. (2017). Shorter sleep duration is associated with social impairment and comorbidities in ASD. Autism Research, 10(7), 1221–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman, A. C. , Smith, L. E. , Greenberg, J. S. , & Mailick, M. R. (2016). Contextual factors predict patterns of change in functioning over 10 years among adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(1), 176–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]