Abstract

During tendon healing, it is postulated that tendon cells drive tissue regeneration, whereas extrinsic cells drive pathologic scar formation. Tendon cells are frequently described as a homogenous, fibroblast population that is positive for the marker Scleraxis (Scx). It is controversial whether tendon cells localize within the forming scar tissue during adult tendon healing. We have previously demonstrated that S100 calcium-binding protein A4 (S100a4) is a driver of tendon scar formation and marks a subset of tendon cells. The relationship between Scx and S100a4 has not been explored. In this study, we assessed the localization of Scx lineage cells (ScxLin) following adult murine flexor tendon repair and established the relationship between Scx and S100a4 throughout both homeostasis and healing. We showed that adult ScxLin localize within the scar tissue and organize into a cellular bridge during tendon healing. Additionally, we demonstrate that markers Scx and S100a4 label distinct populations in tendon during homeostasis and healing, with Scx found in the organized bridging tissue and S100a4 localized throughout the entire scar region. These studies define a heterogeneous tendon cell environment and demonstrate discrete contributions of subpopulations during healing. These data enhance our understanding and ability to target the cellular environment of the tendon.—Best, K. T., Loiselle, A. E. Scleraxis lineage cells contribute to organized bridging tissue during tendon healing and identify a subpopulation of resident tendon cells.

Keywords: S100a4, myofibroblast, heterogeneity, regeneration, tenocyte

Tendon is a dense connective tissue that transmits force from muscle to bone. The transmission of force is facilitated by the tendon’s structure, which consists of an aligned and organized type I collagen extracellular matrix. Following adult acute tendon injury, tendon function is disrupted by the generation of scar tissue, a highly disorganized extracellular matrix consisting of primarily type III collagen. The scar tissue fails to be fully remodeled during healing, impeding tendon function and increasing the incidence of postoperative tendon rupture. Despite the prevalence of acute tendon injuries, the cellular components and molecular mechanisms driving scar formation during tendon healing have not been extensively characterized.

Localization and function of the various cell populations present during tendon healing are still contested. Better understanding of the intrinsic tendon cell population (i.e., resident tendon fibroblasts) and extrinsic populations (i.e., inflammatory cells, nontendon mesenchymal cells) during tendon healing could inform identification of biologic therapeutics. Fetal and neonatal tendons have increased recruitment of native tendon fibroblasts (tenocytes) to the defect site and exhibit regenerative capacities following an acute injury (1–3), whereas injuries in adult animals exhibit a decreased recruitment of intrinsic cells and heal with scar (3). Therefore, it is often the extrinsic cells that are implicated in scar tissue formation, increasing interest in how to harness the regenerative capabilities of intrinsic tendon cells. Despite the potential role of tenocytes in tendon regeneration, the localization of these cells during healing is debated.

Tenocytes are typically regarded as a homogenous population positive for the marker Scleraxis (Scx). Scx is a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor that directs expression of extracellular matrix components and is necessary for the proper development of force-transmitting tendons (4–6). The localization of Scx+ cells during healing differs greatly between specific tendons and injury models, with some studies showing Scx+ cells localized within the defect site (7, 8), whereas others exhibit a complete absence of Scx+ cells within the scar (3). No studies have extensively characterized Scx lineage cell (ScxLin) localization in either a flexor tendon injury model or a model of complete transection and repair.

In potential contradiction to the notion of a homogeneous resident tendon cell population, we have recently demonstrated that S100 calcium-binding protein A4 (S100a4) marks a high proportion of intrinsic tendon cells (9, 10). However, the relationship between the Scx and S100a4 populations is unclear both during tendon homeostasis and in response to injury. We hypothesized that in a model of complete transection and repair of the flexor tendon, Scx+ populations will localize within the scar tissue and that Scx would mark a separate population from the S100a4 cells during homeostasis and healing. In the current study, we characterized the localization of adult ScxLin during tendon healing, using different temporal labeling schemes to assess a variety of Scx+ populations. In addition, we have examined the relationship between Scx+ and S100a4+ cells during homeostasis and throughout tendon healing and assessed the potential of ScxLin to take on a terminal myofibroblast fate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal ethics

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA). All animal procedures were approved by the University Committee on Animal Research at the University of Rochester.

Mouse models

Scx-CreERT2 and Scx-GFP mice were generously provided by Dr. Ronen Schweitzer (Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, USA). C57Bl/6J (000664), ROSA-Ai9 (007909), and S100a4-GFP (012893) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). ROSA-Ai9 mice express Tomato red fluorescence in the presence of Cre-mediated recombination (11). S100a4-GFP mice express endogenous green fluorescent protein (eGFP) under control of the S100a4 promoter (12). Scx-CreERT2 mice were crossed to the ROSA-Ai9 to trace Scx-expressing cells (ScxAi9). ScxAi9 animals received three 100 mg/kg intraperitoneal tamoxifen (TAM) injections at the times outlined in all figures.

Flexor tendon repair

At 10–12 wk of age, mice underwent complete transection and repair of the flexor digitorum longus (FDL) tendon in the hindpaw as previously described in Ackerman et al. (13). Briefly, mice were injected prior to surgery with 15–20 μg of sustained-release buprenorphine. Mice were then anesthetized with Ketamine (60 mg/kg) and Xylazine (4 mg/kg). Following sterilization of the surgery region, the FDL tendon was transected at the myotendinous junction to reduce early-stage strain-induced rupture of the repair site and the skin was closed with a 5-0 suture. A small incision was then made on the posterior surface of the hindpaw, the FDL tendon was located and completely transected using micro spring-scissors. The tendon was repaired using an 8-0 suture and the skin was closed with a 5-0 suture. Following surgery, animals resumed prior cage activity, food intake, and water consumption.

Histology: frozen

Hindpaws from ScxAi9, ScxAi9;S100a4GFP, and Scx-GFP animals were harvested uninjured for frozen sectioning. Additionally, ScxAi9 hindpaws were harvested at 7 d postrepair, and both ScxAi9 and ScxAi9;S100a4GFP hindpaws were harvested at d 14 and 21 for frozen sectioning. Hindpaws were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (fixative) for 24 h at 4°C, decalcified in 14% EDTA for 4 d at 4°C, and processed in 30% sucrose for 24 h at 4°C to cryo-protect the tissue. Samples were then embedded in Cryomatrix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and sectioned into 8 µm sagittal sections using a cryotape-transfer method (14). Sections were mounted on glass slides using 1% chitosan in 0.25% acetic acid and counterstained with the nuclear stain DAPI. Endogenous fluorescence was imaged on a VS120 Virtual Slide Microscope (Olympus, Waltham, MA, USA). Images are representative of 3–6 specimens per time point and contribute to Figs. 1–5 and Supplemental Fig. S2.

Figure 1.

ScxLin localize within the forming scar tissue during flexor tendon healing. A) Scx-CreERT2 mice were crossed to ROSA-Ai9 reporter (ScxAi9) to trace adult ScxLin at homeostasis and throughout healing (ScxLin). B) Mice were injected with TAM for 3 consecutive days followed by a 4-d WO prior to tendon injury and repair. C–F) Tendons were harvested uninjured (C) and at d 7 (D), 14 (E, E′), and 21 (F, F′) postrepair. Nuclear stain DAPI is blue. Tendon is outlined by white dotted lines and scar tissue by yellow dotted lines. White arrows indicate ScxLin with wavy morphology. N = 3–4 specimens per time point. Scale bars, 50 μm (E′, F′), 100 μm (C, D), 200 μm (E, F).

Figure 5.

Scx10−12 and S100a4GFP differentially localize during tendon healing. A, B) ScxAi9; S100a4GFP mice were injected with TAM on d 10–12 postrepair (A) to generate Scx10−12; S100a4GFP mice and were harvested at d 14 (B). C, D) Scx10−12 cells were detected at the tendon stub (C) and bridging tissue (D). Tendon is outlined by white dotted lines and scar tissue by yellow dotted lines. E, F) Quantification of ScxAi9, S100a4GFP, and ScxAi9;S100a4GFP % total area fluorescence at d 14 for both bridging tissue (E) and total scar tissue (F) area. Scale bars, 100 μm (B), 20 μm (C, D). *P < 0.05.

Quantification of fluorescence

Fluorescent images obtained from the virtual slide scanner were processed using Visiopharm image analysis software v.6.7.0.2590 (Visiopharm, Hørsholm, Denmark). Automatic segmentation via a threshold classifier was used to define discrete cell populations based on fluorescent channel. A double constraint was defined to determine colocalization of ScxAi9 and S100a4GFP fluorescence. Regions of interest were drawn to include only the bridging tissue (alignment tissue between tendon stubs consisting of ScxAi9 bridging cells) or the entire scar tissue region for processing. The area of each fluorescent signal was calculated, and these values were used to determine overall percentage of each cell type. An n = 3 was used for quantification.

Four samples were used for the quantification of uninjured ScxLin;S100a4GFP and 6 samples were used for uninjured Scx-GFP fluorescence. Fluorescent cells in uninjured sections were manually counted.

Histology: paraffin

Hindpaws were harvested from ScxLin mice uninjured and at d 14 postrepair and from C57Bl/6J mice at d 7 postrepair for paraffin sectioning. Hindpaws were fixed in 10% formalin for 72 h at room temperature, decalcified in 14% EDTA for 2 wk, processed and embedded in paraffin. Three-micron sagittal sections were cut, dewaxed, rehydrated, and probed with antibodies for red fluorescent protein (RFP) (1:500, ab62341; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), α–smooth muscle actin (αSMA)-CY3 (1:200, C6198; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA), and S100a4 (1:2000, ab197896; Abcam). A Rhodamine Red-X AffiniPure secondary antibody (1:200, 711-296-152; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) was used to fluorescently label RFP and S100a4. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI and imaging was performed using a VS120 Virtual Slide Microscope (Olympus). Paraffin histology contributed to Fig. 6 and Supplemental Figs. S1 and S3. Following imaging, coverslips were gently removed in PBS from ScxLin sections depicted in Fig. 6B and samples were stained with Masson’s trichrome to visualize collagen content.

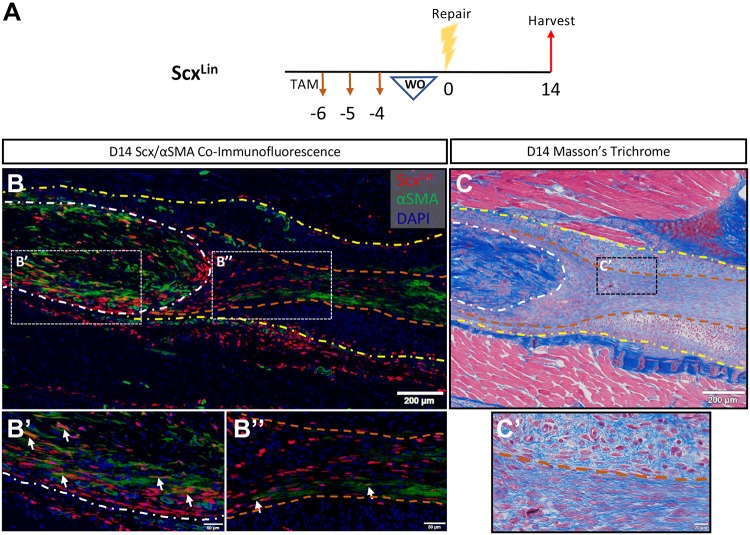

Figure 6.

ScxLin do not substantially differentiate into myofibroblasts. A) ScxAi9 mice were injected with TAM for 3 d and allowed to WO for 4 d (ScxLin). B) Coimmunofluorescence of ScxLin (RFP, labels tdTomato of ROSA-Ai9) and αSMA (myofibroblast marker) on ScxLin d 14 postrepair sections reveals minimal differentiation of ScxLin cells into myofibroblasts. Differentiation occurs primarily within the native tendon (B′) and not within the scar tissue (B″). C, C′) Nuclear stain DAPI is blue. Samples were then stained with Masson’s trichrome to analyze localization of organized collagen deposition at the repair site . Tendon is outlined by white dotted lines and scar tissue by yellow dotted lines. Demarcation of the organized-disorganized collagen boundary labeled with orange dotted lines. Scale bars, 200 μm (B, C), 50 μm (B′, B″), 20 μm (C′).

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are presented here as means ± sem. A 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used to analyze ScxLin, S100a4GFP, and ScxLin;S100a4GFP quantitative data (Fig. 4F, G). A 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used to analyze ScxLin, S100a4GFP, ScxLin;S100a4GFP quantitative data (Fig. 5E, F).

Figure 4.

ScxLin and S100a4GFP populations differentially localize during tendon healing. A) ScxAi9; S100a4GFP mice were injected with TAM on 3 consecutive days and allowed to WO for 4 d prior to repair. B, C) ScxLin; S100a4GFP mice were harvested at 14 (B) and 21 (C) d postrepair. D, E) D 21 bridging (D) and peripheral scar tissue (E) exhibit differential cell contribution and morphology. The tendon is outlined by the white dotted lines and the scar tissue by yellow dotted lines. F, G) Quantification of ScxAi9, S100a4GFP, and ScxAi9;S100a4GFP % total area fluorescence at d 14 (B) and d 21 (C) for both bridging tissue (F) and total scar tissue (G) area. Scale bars, 200 μm (B, C), 20 μm (D, E). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

RESULTS

ScxLin contribute to highly organized bridging tissue within scar during flexor tendon repair

To label the Scleraxis lineage (ScxLin) population prior to injury, ScxAi9 mice were injected with TAM for 3 d followed by a 4-d washout (WO) period immediately prior to surgery (Fig. 1A). Specimens were harvested at d 7, 14, and 21 postsurgery (Fig. 1B). In uninjured tendons, ScxLin cells represented the majority of the total tendon cell population (Fig. 1C). By 7 d following repair, ScxLin cells resided within the tendon body and were not found in the scar tissue (Fig. 1D). At d 7 postrepair, the scar tissue consisted of a heterogenous population of cells, including S100a4+ cells and αSMA+ myofibroblasts (Supplemental Fig. S1). By d 14, ScxLin cells were organized into an aligned bridging tissue that spanned the width of the scar tissue (Fig. 1E, E′). At 21 d postrepair, ScxLin cells were still localized to the tendon stubs and bridging scar tissue and had acquired a wavy morphology (Fig. 1F, F′).

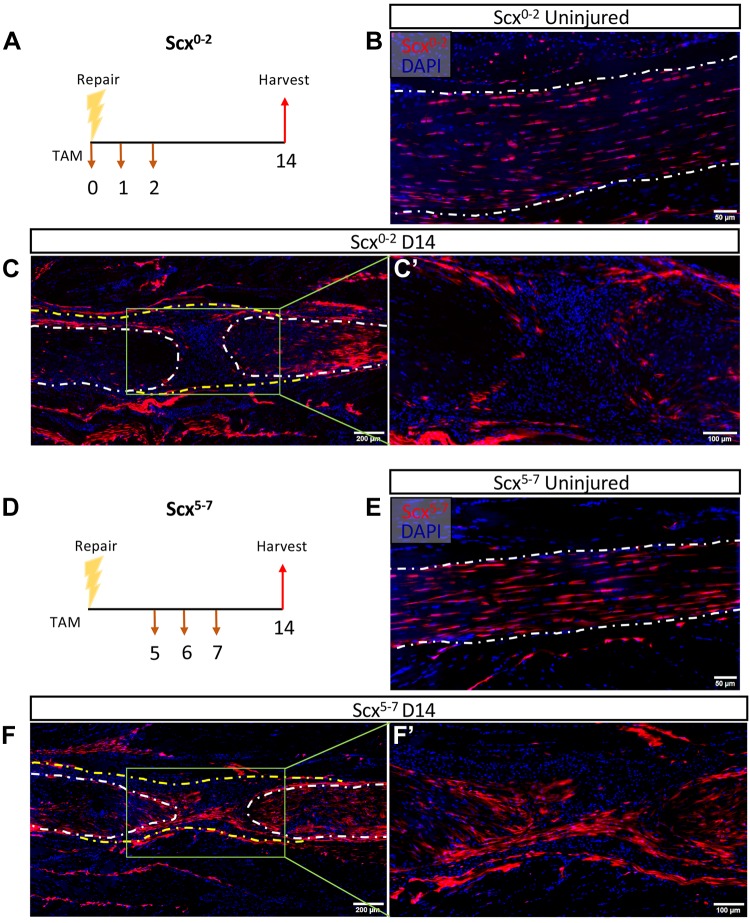

Alterations in Scx expression throughout early tendon healing

To assess the localization of cells expressing Scx immediately after injury, mice were injected with TAM on d 0–2 following repair [Scx-expressing cells labeled on d 0–2 postrepair (Scx0−2)] (Fig. 2A). The localization of Scx0−2 was comparable to ScxLin in the uninjured contralateral control tendon (Fig. 2B). No Scx0−2 cells were found within the scar tissue in 3 out of 4 samples and there were fewer Scx0−2 cells altogether compared with ScxLin (Fig. 2C, C′). To assess localization of cells expressing Scx in the early proliferative stage of healing, mice were injected with TAM on d 5–7 following repair [Scx-expressing cells labeled on d 5–7 postrepair (Scx5−7)] (Fig. 2D). Localization of Scx5−7 in the contralateral control tendon was also comparable to ScxLin (Fig. 2E). At 14 d following repair, Scx5−7 cells were found within the scar tissue at the injury site, similar to ScxLin (Fig. 2F, F′). Thus, different induction schemes demonstrate changes in Scx expression patterns and localization of Scx+ populations postrepair.

Figure 2.

Alterations in Scx expression throughout early tendon healing. A) ScxAi9 mice were injected with TAM on d 0–2 postrepair to trace cells expressing Scx shortly after repair (Scx0−2). B–D) Scx0−2 mice were harvested uninjured (B) and 14 d postrepair (C, C′). ScxAi9 mice were injected with TAM on d 5–7 postrepair to trace cells expressing Scx later in healing (Scx5−7) (D). E, F) Scx5−7 mice were harvested uninjured (E) and 14 d postrepair (F, F′). Nuclear stain DAPI is blue. Tendon is outlined by white dotted lines and scar tissue by yellow dotted lines. N = 3–4 specimens per induction scheme per time point. Scale bars, 50 μm (B, E), 100 μm (C′, F′), 200 μm (C, F).

Scx and S100a4 label distinct and overlapping tendon cells, demonstrating that tenocytes are a heterogenous population

ScxLin cells clearly mark an adult resident tendon cell population, and we have previously demonstrated that S100a4 is also expressed by many of these cells (9, 10); however, the relationship between these 2 populations is unclear. To address this, ScxAi9 mice were crossed to S100a4GFP mice to generate ScxAi9S100a4GFP animals (Fig. 3A). In this model, cells expressing Scx fluoresce red following TAM injection, whereas all cells actively expressing S100a4 fluoresce green. To assess the resident tendon cell populations independent of injury, uninjured contralateral tendons were used. Mice were injected with TAM 3 times and allowed to WO for 18 d before harvest (ScxLinS100a4GFP) (Fig. 3B). Four individual tendon cell populations were identified: ScxLin (17.4%), S100a4GFP (19.4%), ScxLin;S100a4GFP (50.8%), and a dual-negative population (12.4%) (Fig. 3C, D). ScxLin cells accounted for ∼68% of the total population and S100a4GFP cells for ∼70% of the populations (Fig. 3E). In contrast, Scx cell populations quantified from Scx-GFP animals suggested that ∼90% of tendon cells are Scx+ (Supplemental Fig. S2). These data highlight previously unappreciated heterogeneity within the adult tendon cell population.

Figure 3.

Dual tracing of ScxLin and S100a4GFP cells exhibits tendon cell heterogeneity. A) ScxAi9 mice were crossed to S100a4GFP mice (ScxAi9;S100a4GFP) to allow dual tracing of Scx lineage and S100a4+ cell populations. B) ScxAi9;S100a4GFP mice were injected with TAM on 3 consecutive days and harvested 18 d following the final injection. C) Contralateral (opposite foot taken for d 14 repair) ScxAi9;S100a4GFP tendons exhibit 4 distinct cell types with colored arrows indicating examples of each: ScxLin (red arrow), S100a4GFP (green arrow), ScxLin; S100a4GFP (yellow arrow), and dual-negative populations (blue arrow). Nuclear stain DAPI is blue. Scale bars, 20 μm. D, E) Quantification of individual and total Scx and S100a4 populations. N = 4.

Scx and S100a4 cell populations localize differently during flexor tendon repair

We next sought to characterize the localization of these cell populations relative to one another during flexor tendon healing. Mice were injected with TAM using the 4-d WO scheme (Fig. 4A). At 14 d postrepair, the bridging tissue consisted of 29.35% ScxLin cells, 14.40% S100a4GFP, and 28.53% ScxLin;S100a4GFP. The entire scar tissue region, including the bridging tissue, consisted of 13.11% ScxLin, 29.78% S100a4GFP, and 14.12% ScxLin;S100a4GFP (Fig. 4B, F, G). There were significantly more S100a4GFP cells in the total scar tissue compared with ScxLin (P = 0.0186) and ScxLin;S100a4GFP (P = 0.0271) populations at d 14. By 21 d postrepair, the bridging tissue consisted of 55.81% ScxLin, 5.12% S100a4GFP, and 17.54% ScxLin;S100a4GFP (Fig. 4C, F, G). ScxLin cells were significantly more prevalent in the bridging tissue compared with both S100a4GFP (P < 0.0001) and ScxAi9;S100a4GFP (P < 0.0001) populations at d 21. The d 21 ScxLin cell population in the bridging tissue was significantly greater than all other quantified cell types at either d 14 (ScxLin: P = 0.0016, S100a4GFP: P < 0.0001, ScxLin;S100a4GFP: P = 0.0012) or 21 postrepair. At 21 d postrepair, the total scar tissue region consisted of 18.21% ScxLin, 25.34% S100a4GFP, and 25.70% ScxLinS100a4GFP. Interestingly, S100a4GFP cells were found both within the organized bridging scar tissue exhibiting an elongated morphology (Fig. 4D) and throughout the disorganized scar tissue with a rounded morphology (Fig. 4E). To assess if some of the ScxLinS100a4GFP cells were still actively expressing Scx throughout healing, we injected ScxAi9;S100a4GFP mice with TAM at d 10–12 to label cells expressing Scx nearly 2 wk into healing [Scleraxis-expressing cells labeled on d 10–12 postrepair (Scx10−12)] (Fig. 5A). When harvested at 14 d postrepair, Scx10−12 cells were still present within the tendon stubs and bridging tissue (Fig. 5B–D). The bridging tissue consisted of 28.62% Scx10−12, 9.73% S100a4GFP, and 10.62% Scx10−12;S100a4GFP relative to the entire area of the bridging tissue (Fig. 5E). There were significantly more ScxLin cells in the bridging tissue relative to S100a4GFP (P = 0.0285) and ScxLin;S100a4GFP (P = 0.0347) cells. The total scar tissue region consisted of 12.51% Scx10−12, 26.10% S100a4GFP, and 4.84% Scx10−12;S100a4GFP (Fig. 5F). S100a4 cells were significantly more prevalent than ScxLin (P = 0.0269) and ScxLin;S100a4GFP (P = 0.0033) cells in the total scar tissue. Therefore, a subset of cells later in healing are still expressing both Scx and S100a4.

ScxLin cells do not primarily differentiate into myofibroblasts during healing

It has previously been shown that Scx can drive αSMA+ myofibroblast differentiation in the heart (15). To investigate the ability of ScxLin cells in the tendon to differentiate into myofibroblasts, we performed coimmunofluorescence of ScxLin and αSMA on d 14 postrepair sections (Fig. 6A). A small proportion of ScxLin cells expressed αSMA within the tendon stub, with nearly no ScxLin cells expressing αSMA within the bridging scar tissue (Fig. 6B, B′, B″, separated ScxLin and αSMA channels provided in Supplemental Fig. S3A, B). ScxLin cells do not exhibit αSMA+ staining in the uninjured FDL (Supplemental Fig. S3C). Additionally, most αSMA+ myofibroblasts were not expressing RFP, suggesting that the majority of myofibroblasts are not derived from the ScxLin cells. Both ScxLin cells and myofibroblasts were localized to the region of linear, highly organized collagen deposited within the repair site as shown by Masson’s trichrome stain (Fig. 6C, C′), suggesting a relationship between ScxLin cells and the organized bridging collagen scaffold within the scar tissue.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we assessed the localization of ScxLin throughout flexor tendon healing and examined the relationship between Scx and S100a4 cell populations during tendon homeostasis and healing. We have established that ScxLin localize within the scar tissue in a highly aligned and organized manner with alterations in Scx expression occurring shortly after injury in a model of complete transection and repair of the flexor tendon. We have also shown that although Scx and S100a4 are both expressed in a subset of resident tendon cells, there are also populations that express only one of these markers, as well as a double negative population, thus identifying much greater heterogeneity of the resident tendon cell population than previously appreciated. In addition, ScxAi9 and S100a4GFP cells localize differently during tendon injury, suggesting differential roles for these populations during tendon healing.

Previous studies focused on elucidating the localization of Scx cell populations during tendon healing have yielded conflicting findings. In a patellar tendon window-defect model, it was demonstrated that cells from the surrounding paratenon proliferated, migrated to the defect site, and became Scx+ by 7 d postinjury, with Scx+ cells bridging the injury site by 14 d (7). Additionally, it has been demonstrated that a subset of αSMA+ lineage cells derived from the paratenon bridge the patellar tendon window injury and become Scx+ 14 d following repair (16). In contrast, a complete transection injury model of the Achilles tendon demonstrated that although Scx+ cells were present in the gap space and could induce regeneration of neonatal tendon, there was a nearly complete absence of Scx+ and ScxLin in the scar tissue formed within the adult tendon gap space (3). Interestingly, a recent study by Sakabe et al. (8) demonstrated that an adult partial Achilles tendon transection had Scx+ cells within the defect site by d 14 postinjury. This suggests that keeping the cut ends of the tendon near one another and the maintenance of tensile force across the defect may be necessary for localization of Scx+ cells within the defect. Consistent with this, although our repair model does result in complete transection of the tendon, the surgical repair both maintains tensile force and tendon stub proximity, likely facilitating the migration of ScxLin in to the bridging tissue of the defect. It has previously been shown that tendon cells lose Scx expression shortly after acute injury (8) and that Scx expression is mechanosensitive (17). Traces of Scx0−2 and Scx5−7 populations revealed differential Scx expression patterns during healing, with Scx0−2 exhibiting fewer ScxAi9 cells relative to ScxLin and Scx5−7 traces, and an absence of ScxAi9 cells within the scar tissue. The longitudinal changes in Scx expression are likely resulting from the initial loss of physiologic tension at the injury site followed by an increase in tension as the repair begins to heal.

It has previously been shown that epitenon fibroblasts become highly Scx+ and migrate from the epitenon into the tendon fascicles following addition of physiologic loading via treadmill running (18). In addition, Dyment et al. (7, 16) demonstrate that Scx+ cells originating from the paratenon contribute to tissue bridging in a patellar tendon defect model. Identification of epitenon specific markers will permit better understanding of the function and spatial contribution of epitenon-derived cells during tendon healing, including determination of epitenon cellular contribution to the bridging tissue and peripheral scar tissue.

A trace of adult ScxLin revealed that not all tenocytes are ScxLin during homeostasis, providing evidence that tenocytes are not a homogenous population. It has previously been shown that Scx-GFP mice (19) label most, but not all, tendon cells (8). In this work, we have shown that Scx-GFP mice label ∼90% of intrinsic flexor tendon cells (Supplemental Fig. S2). Additionally, previous work has shown that αSMA lineage cells mark a subset of Scx+ tendon cells in uninjured patellar tendon (16). We have previously discovered that S100a4, which has been implicated in pathologic fibrosis in a variety of tissues, labels a subset of intrinsic tendon cells and is present within the scar tissue during flexor tendon healing (9, 10). Additionally, conditional deletion of prostaglandin E2 receptor 4 (EP4) in S100a4-lineage and ScxLin results in distinct phenotypes during tendon healing, suggesting these may represent discrete cell populations (9). Consistent with this, dual tracing of Scx and S100a4 demonstrated that there are at least 4 distinct tendon cell subpopulations during homeostasis: ScxLin, S100a4GFP, ScxLin;S100a4GFP, and a dual-negative population. Although we reported that ScxLin cells constitute ∼68% of the tendon cell population (Fig. 3D, E), the true number of ScxLin cells is likely higher because TAM-inducible Cre recombination is never 100% efficient (20, 21). Although we found that the Scx-GFP mouse labels ∼90% of flexor tendon cells (Supplemental Fig. S2), Scx-GFP may also not be fully representative of endogenous Scx activity due to persistence of GFP signal or missing regulatory elements in the transgene construct (19). Therefore, we expect that the true percentage of Scx-expressing cells likely exists somewhere between ∼68 and 90%. Despite this discrepancy, these findings demonstrate that intrinsic tendon cells are not a homogenous population. Although future studies will be needed to delineate the potential discrete functions of these populations during tendon homeostasis, the dual-negative cell population may represent a resident nonfibroblast cell population.

Our data also suggest divergence in the spatial localization of S100a4 and Scx cells during healing, suggesting they may be performing discrete functions. By 21 d postrepair, the ScxLin cells were highly specific to the tendon stubs and bridging region of the scar tissue. Interestingly, the S100a4 cell population is found both within the organized bridging scar tissue with an elongated cellular morphology similar to ScxLin cells and within the peripheral scar tissue exhibiting a rounded morphology. The relative contribution of tendon-derived S100a4+ cells and extrinsic S100a4+ cells is currently unknown; however, the differences in cellular morphology may be indicative of discrete S100a4 populations that originate from different sources and perform divergent functions during healing. For example, it has previously been shown that both fibroblasts and macrophages can express S100a4 (22, 23). Further investigation to assess the presence of S100a4+ macrophages during tendon healing is warranted. Understanding the specific contributions of ScxLin, S100a4GFP, and ScxLinS100a4GFP to tendon healing is an exciting research avenue moving forward. We have recently shown that depletion of S100a4+ cells during tendon healing impairs restoration of biomechanical properties during flexor tendon healing (10). However, further speculation of specific functions of these cell types during tendon healing is premature at this time.

Scx drives expression of extracellular matrix components, including fibrillar collagens and fibronectin (4, 5, 24). In pathologic settings, fibroblasts can differentiate into contractile myofibroblasts that produce extracellular matrix proteins and aid in wound closure (25, 26). It has been shown that Scx expression in cardiac fibroblasts directly transactivates the αSMA promoter, resulting in αSMA+ myofibroblast differentiation (15). Recently, it has been demonstrated that Scx can also directly transactivate the Twist1 and Snai1 promoters, 2 transcriptional regulators of epithelial mesenchymal transition, further suggesting that Scx can drive myofibroblast differentiation in cardiac fibroblasts (27). However, the effects of Scx-induced αSMA expression are tissue specific as it has previously been shown that Scx represses αSMA expression in the mesangial cells of the kidney (28). In our flexor tendon repair model, we found that a subset of ScxLin differentiated into myofibroblasts (Fig. 6B). However, the majority of myofibroblasts were derived from a different source, suggesting that Scx may drive the differentiation of another cell population into myofibroblasts instead of directly differentiating themselves. We have recently shown that a subset of S100a4 lineage (S100a4Lin) cells differentiate into αSMA+ myofibroblasts following tendon injury and repair (10). However, S100a4GFP cells are not αSMA+, suggesting that S100a4Lin cells may be down-regulating S100a4 and differentiating into myofibroblasts following injury (10). The influence of Scx on S100a4 myofibroblast differentiation has not been evaluated. Masson’s trichrome staining revealed that ScxLin cells are localized along the highly aligned collagenous scaffold deposited within the repair site. It is currently unclear as to whether ScxLin cells directly produce and deposit this collagen or if ScxLin use the collagen as a migratory guide, although this will be an important area of focus for future studies.

This study clearly demonstrates that ScxLin cells localize within the scar tissue following flexor tendon repair and that ScxLin cells represent a separate population from the S100a4GFP cells, highlighting tendon cell heterogeneity. However, there are a few limitations that must be considered. First, although we administered several TAM induction schemes to capture varying Scx+ cell populations, a complete assessment of current Scx expression was not evaluated. Secondly, we did not look any later than d 21 postrepair and therefore did not investigate the localization of ScxLin and S100a4GFP later in healing. Lastly, for our ScxLin trace, we allow 4 d for TAM WO before tendon repair. The half-life of TAM is ∼12–16 h (29, 30), resulting in 0.39–1.56% of the original TAM still residing in the ScxLin mice at the time of tendon repair. Due to these trace amounts of TAM, we cannot assume that the ScxLin trace is not labeling a few newly activated Scx+ cells. However, ScxLin and Scx0−2 exhibit vastly different localization patterns, further suggesting that a short TAM WO period is adequate for this study.

Altogether, these data demonstrate that the ScxLin cell population localize within the scar tissue and form a highly aligned bridging tissue that resembles native tendon in its organization. This contrasts with the S100a4GFP population that is disorganized and present throughout the entire scar tissue. This suggests that the intrinsic ScxLin cells may be driving organized regenerative healing, whereas S100a4GFP cells contribute to the formation of scar. Designing strategies to harness intrinsic cells during adult tendon repair may help in driving tendon regeneration, and a better understanding of the discrete intrinsic cell populations within tendon will help inform on targeted therapies to positively affect healing.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Histology, Biochemistry and Molecular Imaging (HBMI; University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA) Core for technical assistance. This work was supported in part by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) (Grants K01AR068386 and R01AR073169 to A.E.L.). The HBMI and BBMTI Cores are supported by NIH/NIAMS Grant P30AR069655. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- αSMA

α–smooth muscle actin

- FDL

flexor digitorum longus

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- RFP

red fluorescent protein

- ROSA-Ai9

mouse model that expresses red fluorescent protein

- S100a4

S100 calcium-binding protein A4

- S100a4GFP

S100a4-expressing cells

- Scx

Scleraxis

- Scx0−2

Scx-expressing cells labeled on d 0–2 postrepair

- Scx5−7

Scx-expressing cells labeled on d 5–7 postrepair

- Scx10−12

Scx-expressing cells labeled on d 10–12 postrepair

- ScxAi9

Scx-expressing cells

- ScxLin

Scleraxis lineage cells

- TAM

tamoxifen

- WO

washout

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K. T. Best and A. E. Loiselle are responsible for study conception and design; K. T. Best is responsible for acquisition of data; K. T. Best and A. E. Loiselle are responsible for analysis and interpretation of data; K. T. Best and A. E. Loiselle are responsible for drafting the manuscript; and K. T. Best and A. E. Loiselle are responsible for the revision and approval of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Favata M., Beredjiklian P. K., Zgonis M. H., Beason D. P., Crombleholme T. M., Jawad A. F., Soslowsky L. J. (2006) Regenerative properties of fetal sheep tendon are not adversely affected by transplantation into an adult environment. J. Orthop. Res. 24, 2124–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beredjiklian P. K., Favata M., Cartmell J. S., Flanagan C. L., Crombleholme T. M., Soslowsky L. J. (2003) Regenerative versus reparative healing in tendon: a study of biomechanical and histological properties in fetal sheep. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 31, 1143–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howell K., Chien C., Bell R., Laudier D., Tufa S. F., Keene D. R., Andarawis-Puri N., Huang A. H. (2017) Novel model of tendon regeneration reveals distinct cell mechanisms underlying regenerative and fibrotic tendon healing. Sci. Rep. 7, 45238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Léjard V., Brideau G., Blais F., Salingcarnboriboon R., Wagner G., Roehrl M. H., Noda M., Duprez D., Houillier P., Rossert J. (2007) Scleraxis and NFATc regulate the expression of the pro-alpha1(I) collagen gene in tendon fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 17665–17675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Espira L., Lamoureux L., Jones S. C., Gerard R. D., Dixon I. M., Czubryt M. P. (2009) The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor scleraxis regulates fibroblast collagen synthesis. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 47, 188–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murchison N. D., Price B. A., Conner D. A., Keene D. R., Olson E. N., Tabin C. J., Schweitzer R. (2007) Regulation of tendon differentiation by scleraxis distinguishes force-transmitting tendons from muscle-anchoring tendons. Development 134, 2697–2708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyment N. A., Liu C. F., Kazemi N., Aschbacher-Smith L. E., Kenter K., Breidenbach A. P., Shearn J. T., Wylie C., Rowe D. W., Butler D. L. (2013) The paratenon contributes to scleraxis-expressing cells during patellar tendon healing. PLoS One 8, e59944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakabe T., Sakai K., Maeda T., Sunaga A., Furuta N., Schweitzer R., Sasaki T., Sakai T. (2018) Transcription factor scleraxis vitally contributes to progenitor lineage direction in wound healing of adult tendon in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 5766–5780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ackerman J. E., Best K. T., O’Keefe R. J., Loiselle A. E. (2017) Deletion of EP4 in S100a4-lineage cells reduces scar tissue formation during early but not later stages of tendon healing. Sci. Rep. 7, 8658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ackerman J., Studentsova V., Best K., Knapp E., Loiselle A. (2019) Cell non-autonomous functions of S100a4 drive fibrotic tendon healing. bioRxiv, 516088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madisen L., Zwingman T. A., Sunkin S. M., Oh S. W., Zariwala H. A., Gu H., Ng L. L., Palmiter R. D., Hawrylycz M. J., Jones A. R., Lein E. S., Zeng H. (2010) A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwano M., Plieth D., Danoff T. M., Xue C., Okada H., Neilson E. G. (2002) Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest. 110, 341–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ackerman J.E., Loiselle A.E. (2016) Murine flexor tendon Injury and repair surgery. J. Vis. Exp. 115, e54433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dyment N.A., Jiang X., Chen L., Hong S. H., Adams D. J., Ackert-Bicknell C., Shin D. G., Rowe D. W. (2016) High-throughput, multi-image cryohistology of mineralized tissues. J. Vis. Exp. 115, e54468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bagchi R. A., Roche P., Aroutiounova N., Espira L., Abrenica B., Schweitzer R., Czubryt M. P. (2016) The transcription factor scleraxis is a critical regulator of cardiac fibroblast phenotype. BMC Biol. 14, 21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dyment N. A., Hagiwara Y., Matthews B. G., Li Y., Kalajzic I., Rowe D. W. (2014) Lineage tracing of resident tendon progenitor cells during growth and natural healing. PLoS One 9, e96113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maeda T., Sakabe T., Sunaga A., Sakai K., Rivera A. L., Keene D. R., Sasaki T., Stavnezer E., Iannotti J., Schweitzer R., Ilic D., Baskaran H., Sakai T. (2011) Conversion of mechanical force into TGF-β-mediated biochemical signals. Curr. Biol. 21, 933–941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendias C. L., Gumucio J. P., Bakhurin K. I., Lynch E. B., Brooks S. V. (2012) Physiological loading of tendons induces scleraxis expression in epitenon fibroblasts. J. Orthop. Res. 30, 606–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pryce B. A., Brent A. E., Murchison N. D., Tabin C. J., Schweitzer R. (2007) Generation of transgenic tendon reporters, ScxGFP and ScxAP, using regulatory elements of the scleraxis gene. Dev. Dyn. 236, 1677–1682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weng D. Y., Zhang Y., Hayashi Y., Kuan C. Y., Liu C. Y., Babcock G., Weng W. L., Schwemberger S., Kao W. W. (2008) Promiscuous recombination of LoxP alleles during gametogenesis in cornea Cre driver mice. Mol. Vis. 14, 562–571 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu J., Willet S. G., Bankaitis E. D., Xu Y., Wright C. V., Gu G. (2013) Non-parallel recombination limits Cre-LoxP-based reporters as precise indicators of conditional genetic manipulation. Genesis 51, 436–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato F., Kohsaka A., Takahashi K., Otao S., Kitada Y., Iwasaki Y., Muragaki Y. (2017) Smad3 and Bmal1 regulate p21 and S100A4 expression in myocardial stromal fibroblasts via TNF-α. Histochem. Cell Biol. 148, 617–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y., Bao J., Bian Y., Erben U., Wang P., Song K., Liu S., Li Z., Gao Z., Qin Z. (2018) S100A4+ macrophages are necessary for pulmonary fibrosis by activating lung fibroblasts. Front. Immunol. 9, 1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bagchi R. A., Lin J., Wang R., Czubryt M. P. (2016) Regulation of fibronectin gene expression in cardiac fibroblasts by scleraxis. Cell Tissue Res. 366, 381–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pakshir P., Hinz B. (2018) The big five in fibrosis: macrophages, myofibroblasts, matrix, mechanics, and miscommunication. Matrix Biol. 68–69, 81–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baum J., Duffy H. S. (2011) Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts: what are we talking about? J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 57, 376–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Hattab D. S., Safi H. A., Nagalingam R. S., Bagchi R. A., Stecy M. T., Czubryt M. P. (2018) Scleraxis regulates Twist1 and Snai1 expression in the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 315, H658–H668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abe H., Tominaga T., Matsubara T., Abe N., Kishi S., Nagai K., Murakami T., Araoka T., Doi T. (2012) Scleraxis modulates bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4)-Smad1 protein-smooth muscle α-actin (SMA) signal transduction in diabetic nephropathy. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 20430–20442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson S. P., Langan-Fahey S. M., Johnson D. A., Jordan V. C. (1991) Metabolites, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics of tamoxifen in rats and mice compared to the breast cancer patient. Drug Metab. Dispos. 19, 36–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danielian P. S., Muccino D., Rowitch D. H., Michael S. K., McMahon A. P. (1998) Modification of gene activity in mouse embryos in utero by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre recombinase. Curr. Biol. 8, 1323–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.