Abstract

Although the mouse strain Murphy Roths Large (MRL/MpJ) possesses high regenerative potential, the mechanism of tissue regeneration, including skeletal muscle, in MRL/MpJ mice after injury is still unclear. Our previous studies have shown that muscle-derived stem/progenitor cell (MDSPC) function is significantly enhanced in MRL/MpJ mice when compared with MDSPCs isolated from age-matched wild-type (WT) mice. Using mass spectrometry–based proteomic analysis, we identified increased expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) 1α target genes (expression of glycolytic factors and antioxidants) in sera from MRL/MpJ mice compared with WT mice. Therefore, we hypothesized that HIF-1α promotes the high muscle healing capacity of MRL/MpJ mice by increasing the potency of MDSPCs. We demonstrated that treating MRL/MpJ MDSPCs with dimethyloxalylglycine and CoCl2 increased the expression of HIF-1α and target genes, including angiogenic and cell survival genes. We also observed that HIF-1α activated the expression of paired box (Pax)7 through direct interaction with the Pax7 promoter. Furthermore, we also observed a higher myogenic potential of MDSPCs derived from prolyl hydroxylase (Phd) 3–knockout (Phd3−/−) mice, which displayed higher stability of HIF-1α. Taken together, our findings suggest that HIF-1α is a major determinant in the increased MDSPC function of MRL/MpJ mice through enhancement of cell survival, proliferation, and myogenic differentiation.—Sinha, K. M., Tseng, C., Guo, P., Lu, A., Pan, H., Gao, X., Andrews, R., Eltzschig, H., Huard, J. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) is a major determinant in the enhanced function of muscle-derived progenitors from MRL/MpJ mice.

Keywords: stem cell potency, muscle progenitor cells, myogenic differentiation, tissue regeneration

Murphy Roths Large (MRL/MpJ) mice, also known as super healer mice, have the ability to remarkably repair a variety of musculoskeletal tissue injuries throughout their lifespan, including ear wounds, bone lesions, and articular cartilage lesions (1–3). A previous study has linked the superior healing capacity of MRL/MpJ mice to various processes, including decreased scar tissue formation, modified inflammatory reactions, reduced cell apoptosis, increased cell proliferation and differentiation, improved remodeling, and enhanced stem cell function (4). In addition, up-regulation of genes involved in repair processes such as angiogenesis, DNA repair and replication, protein synthesis, glycolysis, and cell adhesion have been reported for MRL/MpJ mice (5, 6). However, some studies have found that the healing capacity of MRL/MpJ mice is not enhanced in amputated digit or cardiac infarction injuries (7), and transplantation of MRL/MpJ bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells does not improve articular cartilage healing in normal mice (8), although recent studies indicated that breeding of MRL/MpJ mice with dystrophic mice reduces fibrosis and increases muscle regeneration (5, 6). Nevertheless, the skeletal muscle regenerative potential of MRL/MpJ mice and the role of MRL/MpJ muscle progenitor cells remain unclear.

It is well known that stress, including free radical accumulation and oxidative stress induced during degenerative diseases such as sarcopenia, has adverse impacts on cellular function, leading to apoptosis of stem/progenitor cells and, consequently, depletion and defects in stem cell pools (9). In order to improve the function of aged stem cells and age-related conditions, circulating factors such as Notch ligands, fibroblast growth factor 2, and growth differentiation factor 11 have been used to rejuvenate defective stem cell niches and regenerate aged tissues through parabiotic pairing or via blood transfer from young to old animals (10–13). Circulating rejuvenating factors include growth factors, cytokines, hormones, and other signaling factors, as well as RNA protein complex–containing exosomes (microRNAs) (14). Because of an inherent ability to spontaneously regenerate various tissues, the MRL/MpJ mouse provides an excellent animal model to study circulating rejuvenating factors that can improve conditions of tissue-specific stem cell niches and their ability to regenerate tissue upon injury.

Circulating factors can act in a paracrine manner to stimulate quiescence and potency of adult stem cells. Hypoxic conditions are best for maintaining the quiescence of adult stem cells, which, upon interaction with certain stimuli, are activated to proliferate and differentiate (e.g., during tissue regeneration processes). Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) 1α plays a central role in activation of glycolytic enzymes to provide a source of energy for quiescence, survival, and potency of adult stem cells, especially in hypoxic microenvironments (15, 16). In fact, HIF-1α is an oxygen-regulated protein and functions as part of a heterodimeric transcription factor that translocates to the cell nucleus upon signaling. This complex binds to DNA, resulting in transcriptional activation of >100 genes (17). These genes are important for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration processes, including neovascularization through angiogenesis, tissue remodeling, and glycolysis for supply of nutrients and metabolites. Adenosine is a metabolite that accumulates in hypoxic conditions and tissue injury sites and, through adenosine-specific cellular receptors, activates several molecular processes, including up-regulation of HIF-1α, which plays an anabolic role in musculoskeletal tissue regeneration and wound healing (18–20). HIF-1α directly binds to the promoter region of certain genes and activates the transcription of these genes in both hypoxia and normoxia. Stabilization of HIF-1α with prolyl hydroxylase (PHD) inhibitor down-regulates collagen deposition, reduces scar tissue formation, and increases vascularity, all of which would be beneficial for skeletal muscle repair (21–23). HIF-1α has been reported to be a central molecule involved in enhanced tissue regeneration and repair after ear punch injury in the MRL/MpJ mouse (24). However, it is still unclear whether HIF-1α plays a role in the improvement of skeletal muscle healing in MRL/MpJ mice. We have isolated a population of muscle-derived stem/progenitor cells (MDSPCs), which have the capacity to differentiate into skeletal muscle, bone, and cartilage during tissue repair (25–30). Hence, we sought to examine the role of HIF-1α in MDSPC potency and modulation of myogenic differentiation in the MRL/MpJ mouse.

In this study, we examined whether the potency and myogenic capacity of MDSPCs in MRL/MpJ mice depend on HIF-1α activity. Mass spectrometry (MS)–based proteomic analysis of circulating serum factors from control wild-type (WT) and MRL/MpJ mice indicated that glycolysis and stress response pathways were activated in MRL/MpJ mouse serum, thus suggesting a potential role for HIF-1α in enhancing tissue healing capacity by improving stem cell function. HIF-1α activity was found to enhance the survival of MRL/MpJ mouse MDSPCs, which consequently led to better myogenic capacity than WT mouse MDSPCs. Moreover, MDSPCs isolated from mice with genetically deleted Phd3, the product of which is a physiologic inhibitor of HIF-1α stability, expressed higher levels of stem cell markers, including paired box (Pax)7. Altogether, our results suggest that HIF-1α is a major determinant in the enhanced function of MDSPCs from MRL/MpJ mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of sera and MS

Mouse sera was obtained from 12-wk-old MRL/MpJ mice and C57B6 mice (WT). Serum samples were pooled from 3 mice per group (MRL/MpJ serum pool and WT serum pool). Trypsin digests of equal amounts of sera from C57BL/6 and MRL/MpJ mice were analyzed by liquid chromatography–MS in order to identify and compare the levels of various circulating serum proteins.

Isolation of MDSPCs, cell culture methods, and preparation of cell lysates

A population of slowly adhering cells (called MDSPCs) from skeletal muscle was isolated using the preplate technique as previously described by Zheng et al. (31). Culture of MDSPCs was performed in a proliferation medium containing basal DMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum, 10% horse serum, 0.5% chicken embryo extract, and antibiotics. MDSPCs isolated from young WT mice were treated with 10% serum derived from both WT and MRL/MpJ mice in proliferation medium. Cell lysates were prepared with RIPA lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM 1 M Tris, pH 8.0, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS) and supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Western blot analysis was performed to validate the MS data using specific antibodies.

Quantitative gene expression analysis

Isolation of total RNA and cDNA was performed with a Cell to CT kit (4399002; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative gene expression analysis was done with cDNA and SYBR green primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA) or Taqman-based primer probes (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using 18S RNA or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase as an internal control.

Myogenic and differentiation of MDSPCs

For myogenic differentiation, cultured MDSPCs were grown in proliferation medium to 80% confluence and then induced with a medium containing low serum (2%) for 3–5 d. Cells were then immunostained for myosin heavy chain (MyHC) to analyze myotube formation. Cells were washed with cold PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, and then permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 5 min. Blocking and incubation steps with primary and secondary antibodies were performed using a Maxpack Immunostaining Media Kit (15251; Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cells were incubated with mouse anti-MyHC fast type antibody (1:500, M4276; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) overnight at 4°C. The primary antibody was detected with an Alexa 594–conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (A21203, 1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min followed by incubation with DAPI (D9542; MilliporeSigma) for nuclei staining.

Construction of the Pax7–green fluorescent protein reporter gene, transfection, and analysis of green fluorescent protein expression

A mouse genomic fragment spanning −1150 to +50 bp of the Pax7 gene with 2 putative HIF response elements, ACGTG, was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies and cloned into a pLVX-IRES-ZSgreen [green fluorescent protein (GFP)] plasmid vector (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA, USA) at ClaI and EcoRI sites. The sequence of the plasmid containing the Pax7 promoter was then validated with DNA sequencing. The Pax7-GFP reporter was transiently transfected into C2C12 and human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells, which were treated with 1 mM dimethyloxalylglycine (DMOG) for 24 h. Analysis of GFP expression was viewed with a Leica fluorescent microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Approximately 1 × 106 MRL/MpJ mouse MDSPCs treated with 1 mM DMOG for 24 h were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde in a serum-free medium for 20 min, followed by quenching with 125 mM glycine as previously described by Sinha et al. (32). After washing with cold PBS, cells were resuspended in 10 volumes of cell lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% Na-deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 0.5 mM PMSF, and protease inhibitor cocktail). Whole-cell lysate was then sonicated and cleared by centrifugation. Sonicated chromatin was diluted in lysis buffer without SDS to bring the final concentration of SDS to 0.05%. Antibodies specific for HIF-1α (MAB5382; MilliporeSigma) and mouse IgG (for control) were first conjugated to magnetic-coated protein G beads (Magnetic Dynabeads-Protein G; Thermo Fisher Scientific), which were previously blocked with 0.5% bovine serum albumin in PBS. Chromatin was incubated overnight with antibody at 4°C with rotation, and then immune complexes were collected using a magnetic stand and eluted with 1% SDS and 100 mM NaHCO3 followed by reverse cross-linking at 65°C overnight. Immunoprecipitated DNA was purified using phenol:chloroform and then precipitated and resuspended in low-concentration Tris-EDTA buffer. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed with 500 nM primers, 7.5 μl 2× SYBR green I PCR master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 5 μl DNA in a total reaction volume of 15 μl. The gene-specific primer sequences are listed in Table 1. Results were computed as percent antibody bound/input. At least 3 independent experiments were performed for chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays, and qPCR was performed in triplicate assays. Primers used for qPCR were tested first with input DNA to analyze a linear range of amplification.

TABLE 1.

List of gene-specific primers used in this study

| Gene | Primer sequence, 5′–3′ |

|

|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | |

| Pax3 | GCCCTCCAACCCCATGA | GTGGTTGGTCAGAAGTCCCATT |

| Notch3 | CATGCAGGACAGCAAGGAAGA | GAGATGATCCAGCAGCAGCTT |

| Hes1 | AGAAGGCAGACATTCTGGAAATG | GCGCGGCGGTCATCT |

| P57 | AGCTGAAGGACCAGCCTCTCT | TTCTCCTGCGCAGTTCTCTTG |

| GAPDH | TCCATGACAACTTTGGCATTG | TCACGCCACAGCTTTCCA |

| IL-6 | GGAAATCGTGGAAATGAG | GCTTAGGCATAACGCACT |

| Myogenin | TCCCAACCCAGGAGATCATTT | GACGTAAGGGAGTGCAGATTGTG |

| MyoD | CATCCCTAAGCGACACAGAACA | GCACCTGATAAATCGCATTGG |

| Phd3 | GTCAGACCGCAGGAATCCA | TCATAGCGTACCTGGTGGCATA |

| Pax7 | TCTCCAAGATTCTGTGCCGAT | CGGGGTTCTCTCTCTTATACTCC |

| Runx2 | AGCCAGGCAGGTGCTTCA | CGGCTCTCAGTGAGGGATGA |

| Sox9 | GCGAGCACTCTGGGCAATC | AGATCAACTTTGCCAGCTTGCA |

| Glut1 | GGCTGTGCTGTGCTCATGAC | GGCCACGATGCTCAGATAGG |

| Hk2 | ACCTGCGCACAGTGTTTGAC | CCGCTGATCATCTTCTCAAACC |

| Pkm | GGATGCCGTGCTGAATGC | GACCACATCTCCCTTCTTGAAGA |

| Ldh | CGGCGTCTCCCTGAAGTCT | TTGATCACCTCGTAGGCACTGT |

| Vegfa | GCAGACCAAAGAAAGACAGAACAA | ACAGTGAACGCTCCAGGATTTAA |

| Nos2 | CGAGGAGCAGGTGGAAGACT | GGAAAAGACTGCACCGAAGATATC |

| Tgf-b3 | CAGGCCCTTGCCCATACC | TCTGGGTTCAGGGTGTTGTATAGTC |

| Igf2 | TGTCTACCTCTCAGGCCGTACTT | TCCAGGTGTCATATTGGAAGAACTT |

| Id2 | CCGACGATCGCATCTTGTG | GGGAACCGAGAGCACTTTTTT |

| Ccnd1 | CGCACTTTCTTTCCAGAGTCATCA | CTCCAGAAGGGCTTCAATCTGTT |

| Primers for ChIP | ||

| Pax7-Prox | CGGCAGCCGGTGTCAT | GCGACAAGGAAGTTCAAACAAA |

| Pax7-1.2kb | TAGTCCAGGAGGCCAGAGATAGC | TCTGCCCGCTGTGTAGGAA |

| Pax7-3′UTR | TCTTGGTATAAAATGGGACTTGTGTT | GACAGATTCACAAAAGCATGAGACA |

| Glut1 | GCAGCCAGGGCTCTATAGTGA | GGTCTAATAGTCTCCTCCTGATTTGAA |

| Vegfa | GCAGGCTGCTGTAACGATGA | CTGCATGGTGATGTTGCTCTCT |

GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

RESULTS

Circulating serum factors from MRL/MpJ mice regulate function of WT MDSPCs through modulation of gene expression

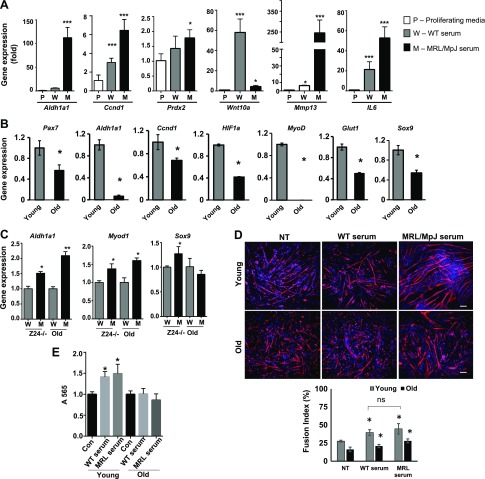

A previous study has shown that circulating factors from young mice contain several rejuvenating factors that can improve stem cell function and tissue regeneration through paracrine activities in old mice (13). Similarly, to test if MRL/MpJ mouse serum harbors rejuvenating factors that could potentially improve stem cell function and regenerative capacity in a paracrine manner, we evaluated the effect of MRL/MpJ serum on young WT MDSPCs cultured in proliferation medium supplemented with 10% serum from MRL/MpJ mice for 3 d. We analyzed the expression levels of candidate genes that have roles in stem cell function and tissue remodeling. Quantitative gene expression analyses indicated that MRL/MpJ serum modulated gene expression in WT MDSPCs. Higher levels of expression of the stem cell marker aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member A1 (Aldh1a1), cell proliferation marker cyclin D1 (Ccnd1), antioxidant peroxiredoxin 2, tissue remodeling marker matrix metalloproteinase 13, and inflammatory and regenerative marker IL-6 were induced by MRL/MpJ mouse serum relative to WT serum (Fig. 1A), demonstrating the potential of the MRL/MpJ serum to regulate MDSPC function. However, Wnt10a expression was down-regulated in MDSPCs by MRL/MpJ serum. Recently, it was reported that Wnt10−/− mice have delayed wound healing in a skin-injury model (33). Next, we asked whether MRL/MpJ serum has a similar effect on aged MDSPCs. First, we isolated MDSPCs from a naturally aged (2-yr-old) and a progeroid mouse model, Z24−/−, that has deletion of the zinc metalloproteinase gene Zmpste24. We compared the gene expression levels between young and old MDSPCs (Fig. 1B). The transcript levels of Pax7, Aldh1a1, HIF-1α, and glucose transporter 1 (Glut1) (for quiescence), Ccnd1 (for proliferation), myogenic differentiation 1 (MyoD1) (for myogenic), and sex-determining region Y-box 9 (Sox9) (for chondrogenic) markers were decreased in aged (old) MDSPCs compared with young MDPSCs isolated from 3-wk-old young mice, indicating a decreased myogenic potential of old MDSPCs. However, the mRNA levels of at least Aldh1a1 and MyoD1 expression were higher in progeroid and aged MDSPCs when incubated in medium containing MRL/MpJ mouse serum (Fig. 1C) than those in WT mouse serum. However, levels of the chondrogenic marker Sox9 were elevated only in Z24−/− MDSPCs by MRL/MpJ serum. Aldh1a1 is a stem cell marker that promotes adult stem cell survival under stress. Myogenic capacity of both young and old MDSPCs was increased when incubated with MRL/MpJ serum compared with WT serum. The cells were treated with sera (MRL/MpJ and WT) before cultivation in myogenic differentiation medium, and the myogenic potential was analyzed by immunostaining for MyHC (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, both WT and MRL/MpJ sera were able to promote proliferation of young MDSPCs but not old MDSPCs as assayed with MTT assay (Fig. 1E). These results indicate that MRL/MpJ mouse serum, through paracrine activities, plays a role in regulating the function of MRL/MpJ MDSPCs and improving their potency, differentiation, and regenerative potentials.

Figure 1.

Effects of MRL/MpJ mouse serum on regulation of gene expression in WT MDSPCs and aged MDSPCs. A) Quantitative gene expression analysis using SYBR buffer for the respective genes as indicated. WT MDSPCs were cultured in proliferation medium (P) supplemented with 10% serum from WT C57BL/6J (W) and MRL/MpJ (M) mice. B) qRT-PCR to analyze gene expression levels in young WT MDSPCs and old MDSPCs. C) qRT-PCR for gene expression levels in MDSPCs from progeroid mice [Zmpste24 (Z24−/−)] and naturally aged old mice after treatment with C57BL/6J (W) and MRL/MpJ (M) mouse sera. D) Myogenic differentiation capacity of young and old MDSPCs untreated (NT) and treated with WT and MRL/MpJ sera. Fusion index is shown in the right panel. Scale bars, 100 μm. E) MTT assay for cell proliferation of young and old MDSPCs treated with WT and MRL/MpJ (MRL) sera. Mmp13, matrix metalloproteinase 13; ns, not significant; Prdx2, peroxiredoxin 2. Error bars indicate means ± sem from triplicates (P < 0.05). *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001.

MS analysis of serum proteins from MRL/MpJ and WT mice

To identify and compare serum factors in WT and MRL/MpJ mice, we performed a tandem MS–based proteomic analysis. We identified the 270 highest-ranked proteins with peptide scores (not an absolute quantitative score but an estimation of relative abundance) in both MRL/MpJ and WT mouse sera. More than 50 proteins (20–30%) were found exclusively in MRL/MpJ mouse serum. Table 2 shows a list of those proteins whose levels were higher in MRL/MpJ mouse serum and are involved in anaerobic glycolysis and antioxidative stress. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of up-regulated proteins in MRL/MpJ mouse serum revealed increased activation of oxidative stress, glycolysis, and superoxide radical scavenger pathways in the MRL/MpJ mice when compared with WT mice. Western blot analysis with lysates of MRL/MpJ and WT mouse MDSPCs further confirmed that levels of Glut1, superoxide dismutase 1, and enolase C (muscle specific) were higher in MRL/MpJ than WT MDSPCs (Fig. 2). These data suggest that the high healing capacity of MRL/MpJ mice might be due to high levels of antioxidants and stress-related regulators that enhance stem cell function. Hgh levels of glycolytic factors in MRL/MpJ mice therefore demonstrate the key role of HIF-1α in survival, proliferation, and maintenance of multipotent MDSPCs under hypoxia.

TABLE 2.

Relative peptide score of representative proteins identified in sera of MRL/MpJ and WT mice by MS

| Protein ID | Protein name | Peptide score |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| MRL/MpJ | WT | ||

| O70362 | Phosphatidylinositol-glycan-specific phospholipase D | 701 | 425 |

| P08228 | Superoxide dismutase | 238 | 0 |

| Q923D2 | Flavin reductase (NADPH) | 175 | 0 |

| P05064 | Fructose-bisP aldolase A | 160 | 0 |

| P15327 | Bisphosphoglycerate mutase | 147 | 0 |

| P63017 | Heat shock 71 kDa protein | 141 | 0 |

| P35700 | Peroxiredoxin-1 | 57 | 0 |

| P24270 | Catalase | 76 | 0 |

| P13634 | Carbonic anhydrase 1 | 398 | 0 |

| P07310 | Creatine kinase M | 259 | 0 |

| Q61171 | Peroxiredoxin-2 | 252 | 0 |

| P35441 | Thrombospondin-1 | 391 | 0 |

| P06684 | Complement C5 | 933 | 1858 |

| P01029 | Complement C4-B | 0 | 1193 |

ID, identifier.

Figure 2.

MS analysis of serum protein from WT and MRL/MpJ mice. Western blot analysis with respective antibodies as indicated in the panel of whole-cell lysates of WT and MRL/MpJ MDSPCs. Eno, enolase; Sod1, superoxide dismutase 1; Runx2, runt-related transcription factor 2.

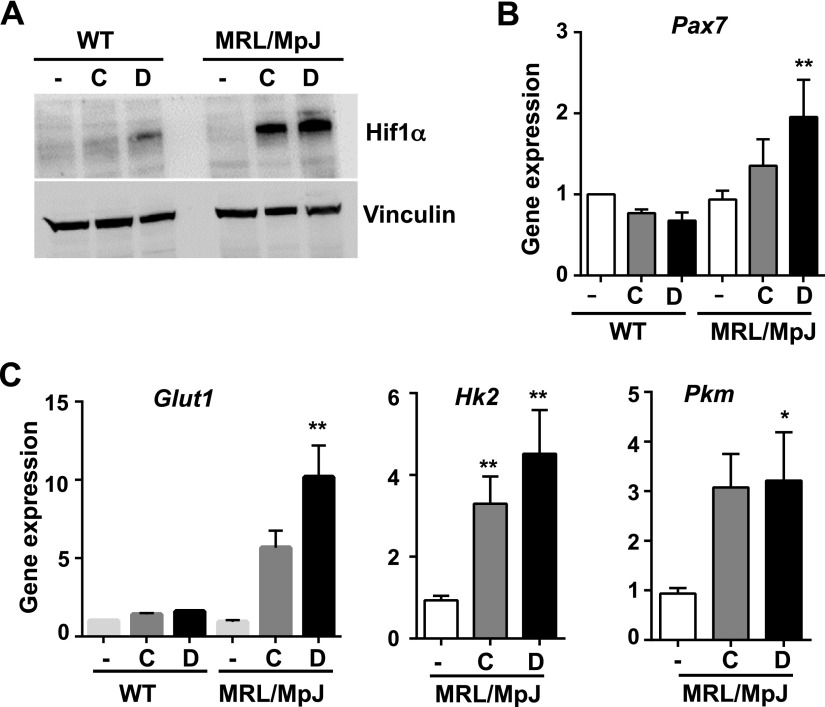

HIF-1α stability is greater in MRL/MpJ MDSPCs than WT MDSPCs and activates Pax7 expression

HIF-1α is known to play a central role in activation of glycolytic enzymes to provide a source of energy for survival and potency of adult stem cells, especially in hypoxic conditions (16, 34). Based on our findings of higher glycolytic pathway proteins in MRL/MpJ mouse serum, we hypothesized that HIF-1α activity might be higher in MRL/MpJ mice to maintain the improved potency of MRL/MpJ MDSPCs when compared with WT MDSPCs. To test this, MDSPCs from WT and MRL/MpJ mice were treated with HIF-1α inducers: 200 μM CoCl2 and 1 mM dimethyl oxyglycin (DMOG) for 24 h. CoCl2 is a chemical compound that mimics hypoxia, and DMOG is a chemical compound that inhibits PHD (an inhibitor of HIF-1α stability). Western blot analysis with an antibody specific for HIF-1α showed the expression levels of HIF-1α were higher in the lysates of MRL/MpJ MDSPCs than those of WT MDSPCs (Fig. 3A). Gene expression analysis showed that levels of Pax7 mRNA, a classic marker of myogenic precursor MDSPCs, increased with DMOG treatment in MRL/MpJ MDSPCs, thereby suggesting that Pax7 is a potential novel HIF-1α target gene (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Higher levels of HIF-1α and expression of glycolytic genes were found in MRL/MpJ MDSPCs than WT MDSPCs. A) Western blot analysis of the levels of HIF-1α in the lysates of WT MDSPCs and MRL/MpJ MDSPCs after treatment with DMOG (1 mM) and CoCl2 (200 μM) for 24 h. B, C) qRT-PCR for gene expression analysis in untreated and treated WT MDSPCs and MRL/MpJ MDSPCs for HIF-1α target genes, including Pax7, Glut1, Hk2, and Pkm. Error bars indicate means ± sem from triplicates (P < 0.05). *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001.

Higher levels of anaerobic glycolytic factors in MRL/MpJ mice are positively regulated by HIF-1α

In hypoxic milieu with limited metabolism, nutrient, and energy supply, adult stem cells depend on anaerobic glycolysis for energy sources to support their survival, maintenance, and proliferation. Several glycolytic genes are transcriptional targets of HIF-1α, which activates these genes through its interactions with the gene promoters (16, 34). Consistent with this, we found that CoCl2 and DMOG treatment stimulated higher expression levels of the genes Glut1, hexokinase 2 (Hk2), and pyruvate kinase (Pkm) in MRL/MpJ MDSPCs than in WT MDSPCs (Fig. 3C). These genes are the key regulators of the glycolysis pathway. The levels of these genes, particularly Hk2 and Pkm, remained unchanged in WT MDSPCs because HIF-1α levels were not as stimulated in WT as in MRL/MpJ MDSPCs, based on Western blot analysis (Fig. 3A). In proteomics analysis, the levels of hexokinase and pyruvate kinase were apparently higher in sera of MRL/MpJ mice than WT mice, suggesting a higher level of HIF-1α activity in MRL/MpJ mice. These results indicate that, like other stem cells under hypoxic conditions, HIF-1α activation in MRL/MpJ MDSPCs may support their survival and proliferation by promoting the glycolytic pathway, which supplies energy to stem cells.

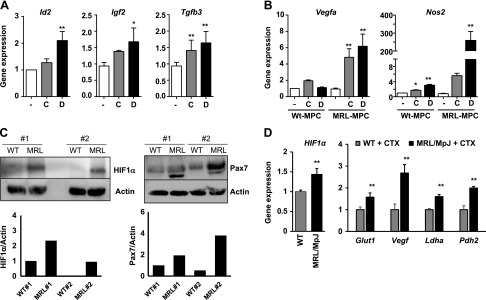

HIF-1α stimulates expression of genes involved in stem cell survival, proliferation, and angiogenesis

Among several other HIF-1α target genes, we also investigated the inhibitor of differentiation 2 (Id2), Igf2, and TGF3 (Tgfb3) as potential genes involved in cell survival and proliferation (35–37). We found that expression levels of these genes were more induced in CoCl2- and DMOG-treated MRL/MpJ MDSPCs than untreated cells (Fig. 4A). However, the expression levels of these genes in WT MDSPCs remained unchanged (unpublished results). This supports the notion that increased HIF-1α activity in MRL/MpJ MDSPCs results in higher survival and proliferation of these MDSPCs through activation of these genes. Also, HIF-1α is an important regulator for neovascularization during tissue repair through transcriptional activation of specific genes (38). Upon HIF-1α stabilization, MRL/MpJ MDSPCs were found to have relatively higher levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (Vegf) A and NO synthase 2 (Nos2) (inducible NO) mRNA compared with WT MDSPCs (Fig. 4B). The Nos2 gene is highly activated during muscle regeneration upon injury in skeletal muscle (39). These data strongly suggest that HIF-1α may be a key regulator in activation of Vegfa and Nos2 in MRL/MpJ mice, which may improve skeletal muscle regeneration through promotion of angiogenesis. We have recently shown that muscle regeneration and angiogenesis were increased in cardiotoxin-injured MRL/MpJ mice when compared with WT mice (40). Consistent with these data, in the current study, we also observed that in cardiotoxin-induced muscle injury, at 24 h post-injury to both WT and MRL/MpJ mice, elevated levels of HIF-1α protein were observed in the skeletal muscle tissue of MRL/MpJ mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 4C). In parallel with this, Pax7 protein levels also increased in injured muscles of MRL/MpJ mice compared with WT mice, suggesting a potential accumulation of Pax7+ progenitor cells following muscle injury (Fig. 4C). Increased HIF-1α levels also correlated with higher levels of HIF-1α target genes Glut1, Vegf, lactate dehydrogenase A, and Pdh2 in MRL/MpJ mouse skeletal muscle (Fig. 4D). Altogether, our findings suggest that HIF-1α activity is increased in MRL/MpJ mice to improve the multipotent function of MRL/MpJ MDSPCs and their regenerative potential during tissue repair.

Figure 4.

Activation of HIF-1α stimulates expression of proliferation and survival genes for stem cells in MRL/MpJ MDSPCs. A, B) Quantitative gene expression analysis of stem cell survival and proliferation marker genes, including Id2, Igf2, and Tgfb3 (A) and angiogenic marker genes Vegfa and Nos2 (B). C) Levels of HIF-1α and Pax7 24 h after CTX-injured skeletal muscle from WT and MRL/MpJ mice (n = 2). Actin was used as loading control. Densitometry is shown below each panel. D) Quantitative gene expression showing mRNA levels of HIF-1α expression and target genes in skeletal muscle after 5 d post-CTX injury in WT and MRL/MpJ mice. CTX, cardiotoxin. Error bars indicate means ± sem from triplicates (P < 0.05).

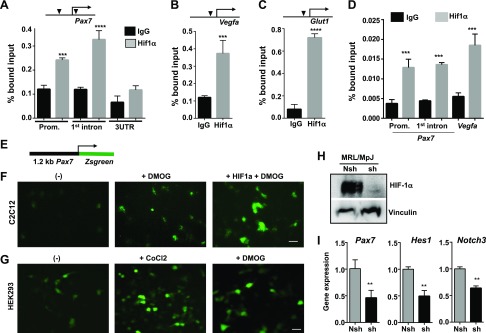

HIF-1α binds to the Pax7 promoter and activates Pax7 expression in MRL/MpJ MDSPCs

To examine whether Pax7 is a direct transcriptional target of HIF-1α activation, we performed ChIP assays to study the interaction of HIF-1α and its target genes using chromatin prepared from DMOG-treated MRL/MpJ mouse MDSPCs. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated with HIF-1α−specific antibody and rabbit IgG (as a control). Immunoprecipitated DNA samples were used for qPCR using primers to amplify the region with potential HIF-1α binding sites. In silico analysis of the mouse Pax7 gene promoter revealed 2 potential binding sites containing ACGTG: 1 at −1.2 kb from the transcriptional start site (TSS) and another at +45 bp downstream of the TSS. Both regions were amplified with respective primer sets by qPCR, suggesting that HIF-1α interacts with the Pax7 gene promoter at these 2 sites but not at the 3′UTR region, which is a control region without an HIF-1α binding site (Fig. 5A). Next, we analyzed binding of HIF-1α at the promoters of Vegfa and Glut1, known targets of HIF-1α. Our results showed a strong interaction of HIF-1α with the promoters of Vegf and Glut1 (Fig. 5B, C). These findings suggest a novel mechanism for the high regenerative capacity of MRL/MpJ mice through HIF-1α, which directly interacts with the Pax7 promoter and activates Pax7 expression in MRL/MpJ MDSPCs and maintains Pax7+ progenitors in hypoxic conditions. Although both CoCl2 (hypoxia mimetic) and DMOG (nonspecific PHD inhibitor) stabilize HIF-1α in normaxia, there are different effects of those treatments (CoCl2 and DMOG) in the expression of the HIF-1α target genes (41). In addition, the possibility of different kinetics in the induction of the hypoxic-related genes by these chemicals cannot be ruled out. Our results suggest that DMOG appears to be more effective in inducing the expression of Pax7, Igf2, and Nos2 than CoCl2 when treated for 24 h. However, ChIP data indicate that HIF-1α also interacted with the promoter of Pax7 and Vegfa in CoCl2-treated MRL/MpJ MDSPCs (Fig. 5D), similar to DMOG-treated cells (Fig. 5A, B), suggesting that transcription of Pax7 might be HIF-1α–independent.

Figure 5.

ChIP assay for interactions of HIF-1α at its target genes in MRL/MpJ MDSPCs. Chromatin prepared from DMOG-treated MRL/MpJ MDSPCs was immunoprecipitated with control IgG and HIF-1α antibodies, followed by qPCR with gene-specific primers flanking HIF-1α responsive genomic sequence using ChIP DNA. A–C) Interactions of HIF-1α are indicated by % bound input: 3 regions in Pax7, the promoter region (Prom.), first intron, and 3′UTR as control region (A); the Vegfa promoter (B); and the Glut1 promoter that harbors HIF-1α –responsive genomic sequence and is indicated by a solid triangle (C). D) ChIP assay for HIF-1α occupancy at the Pax gene in CoCl2-treated MRL/MpJ MDPSCs. E) Schematic of a construct containing the 1.2-kb mouse Pax7 promoter driving the expression of Zsgreen (GFP). F, G) Fluorescent microscopic images taken after transient transfection with the Pax7-Zsgreen reporter gene in the myoblast cell line C2C12 (F) and HEK 293 cells (G), each in the presence of DMOG (1 mM) or CoCl2 (200 μM), and coexpression of mutant HIF-1α after transfection as indicated. Scale bars, 10 μm. H) Level of HIF-1α in MRL/MpJ MDSPCs after transducing with lenti-nshRNA and lenti-shRNA followed by precondition to hypoxic conditions for 24 h was analyzed with Western blot using the cell lysates. I) Quantitative gene expression showing mRNA levels of myogenic stem cell markers Pax7, Hes1, and Notch3 in nshRNA and HIF-1α shRNA MDSPCs from MRL/MpJ mice.

We performed an additional set of experiments to further validate that activation of HIF-1α up-regulates Pax7 by stimulating Pax7 promoter activity. We cloned a fragment of the mouse Pax7 promoter containing −1.2 kb to +50 bp upstream of the Pax7 gene and fused it with GFP (Pax7-GFP). In this construct, GFP expression is dependent on Pax7 promoter activity, which can be stimulated by HIF-1α (Fig. 5D). The reporter plasmid was transfected in myoblast-like C2C12 cells for 48 h. Figure 5F shows that treating the transfected cells with DMOG stimulated GFP expression compared with untreated cells, which poorly expressed GFP. Coexpression of mutant HIF-1α (degradation-deficient form), together with DMOG treatment, further increased GFP expression when compared with untreated and DMOG-treated cells. Similar experiments were performed in HEK 293 cells, and treating transfected cells with CoCl2 and DMOG induced higher levels of GFP expression compared with untreated cells (Fig. 5G). These results indicate that HIF-1α positively regulates Pax7 promoter activity. To further confirm that HIF-1α plays an important role in stemness and multipotency of MRL/MpJ MDSPCs, we knocked down HIF-1α with a lentiviral vector expressing HIF-1α–specific short hairpin RNA (shRNA) in MRL/MpJ MDSPCs. HIF-1α protein levels were significantly reduced in shRNA-treated cells (Fig. 5H). Gene expression analysis data showed that stem cell markers Pax7, Hes1, and Notch3 were significantly down-regulated in HIF-1α–shRNA–transduced cells (Fig. 5I), implying that HIF-1α activity is critical for maintaining stem cell potency in hypoxia.

HIF-1α promotes MDSPC stemness partly through down-regulation of WNT pathways and differentiation factors

HIF-1α plays an important role in maintaining the quiescence of Pax7+ satellite stem cells and preventing their proliferation and differentiation through inhibition of the WNT pathway (42–44). To test whether HIF-1α affects the expression levels of WNT target genes in MRL/MpJ mouse MDSPCs, we measured the expression levels of these genes in DMOG-treated MRL/MpJ MDSPCs or cells cultured in hypoxia for 24 h (Fig. 6A). Our data show that HIF-1α stability decreased the levels of WNT target genes, including Wnt1, lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1, Tcf1, and Axin, compared with untreated or control cells cultured in normoxia (Fig. 6A). Because HIF-1α maintains the stemness of adult stem cells but not their differentiation capacity, we analyzed the expression levels of genes encoding differentiation factors. The genes MyoD1, osterix, and Sox9 were analyzed by qPCR, the products of which are transcription factors for differentiation of muscle, bone, and cartilage, respectively (Fig. 6B). DMOG treatment of WT and MRL/MpJ MDSPCs down-regulated the expression levels of Myod1, osterix, and Sox9 but not the Runx2 gene, which is an early bone-specific transcription factor, thereby suggesting that HIF-1α prevents the differentiation capacity of MDSPCs by negatively regulating the expression of tissue-specific differentiation factors. To test the role of HIF-1α during myogenic differentiation, WT and MRL/MpJ MDSPCs were differentiated to myoblasts in the presence of HIF-1α inhibitor PX487, which inhibits HIF-1α expression and activity (45). The myotube formation was increased in PX487-treated cells in a dose-dependent manner compared with untreated cells (Fig. 6C). Strikingly, the myogenic capacity of MRL/MpJ MDSPCs was much higher than that of WT MPCs, which is consistent with our observations that MRL/MpJ MDSPCs always showed an improved myogenic potential. Furthermore, the mRNA levels of MyoD1 and Pax7 genes were higher in PX487-teated MRL/MpJ MDSPCs, further supporting an increased myogenic differentiation capacity in MRL/MpJ MDSPCs (Fig. 6D). It appears that inhibition of HIF-1α during myogenic differentiation relieved the suppression of transcription factors and WNT target genes, resulting in increased proliferation of Pax7+ cells and their subsequent myogenic differentiation. Our data do not exclude the possibility that Pax7 expression is also mediated by an HIF-1α–independent mechanism, particularly in normoxic conditions. Taken together, our data suggest that HIF-1α promotes the self-renewal capacity of MDSPCs through direct activation of the Pax7 gene and helps with maintenance of multipotent MDSPCs with respect to their quiescence during hypoxia. Furthermore, HIF-1α is indispensable for MDSPC multipotency in the undifferentiated state but dispensable for myogenic differentiation.

Figure 6.

HIF-1α inhibits expression of WNT/β-catenin, differentiation factor genes, and myogenic differentiation of WT and MRL/MpJ MDSPCs. A) Quantitative gene expression analysis of untreated and DMOG-treated MRL/MpJ MPCs (left) and MDSPCs cultured in hypoxia (right). B) Levels of differentiation factors in WT and MRL/MpJ MDSPCs after treatment with DMOG in proliferation medium. C) Immunostaining analysis with MyHC-specific antibody and DAPI of myogenic differentiation in untreated (NT) and HIF-1α inhibitor (PX487)–treated MDSPCs. Fusion index is shown in the lower panel. Scale bars, 50 μm. D) Quantitative gene expression analysis for mRNA levels during myogenic differentiation of WT and MRL/MpJ MDSPCs after treatment with PX487. LEF1, lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1; Osx, osterix; Runx2, runt-related transcription factor 2; TCF1- T-cell specific transcription factor 1. Error bars indicate ±SEM from triplicates. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001.

MDSPCs from PhD3-knockout mice have higher myogenic capacities and expression levels of muscle stem cell markers than WT MDSPCs

PHDs are inhibitors of HIF-1α stability through hydroxylation and ubiquitination followed by degradation of HIF-1α during normoxia (46). HIF-1α is protected from degradation and stabilized in Phd3−/− mice in normoxia compared with WT mice. We isolated MDSPCs from Phd3−/− mice by the preplate technique and showed a reduction of Phd3 mRNA by more than 75% in Phd3−/− MDSPCs relative to WT MDSPCs (Fig. 7A), confirming the genetic deletion of the Phd3 gene in Phd3−/− MDSPCs. Next, we tested the effects of the functional loss of Phd3 in potency and myogenic capacity of MDSPCs from WT and Phd3−/− mice. Our results indicate that expression levels of Pax3, Pax7, Notch3, Notch1, Hes1, and p57 genes were higher in Phd3−/− MDSPCs than WT MDSPCs (Fig. 7A). These genes (in particular, Notch signaling genes) are known to play roles in maintaining the stemness of muscle stem cells (47–49). Furthermore, levels of the myogenic marker genes Myod1 and myogenin and myotube formation were also increased in Phd3−/− MDSPCs when compared with WT MDSPCs (Fig. 7A, B). DMOG treatment to inhibit other PHDs also induced myotube formation in both WT and Phd3−/− MDSPCs (Fig. 7B). When the levels of HIF-1α were compared in hypoxic cultures of MDSPCs from WT, Phd3−/−, and MRL/MpJ mice, we observed that HIF-1α levels were expectedly higher in Phd3−/− MDSPCs than the other MDSPCs (Fig. 7C). Levels of Pax7 were much higher in MRL/MpJ MDSPCs than the other MDSPCs; however, Glut1 levels were moderately increased in Phd3−/− MDSPCs. Pax7 levels did not correlate with HIF-1α, which might be due to a ubiquitination-dependent degradation of Pax7 in WT and Phd3−/− MDPSCs (50, 51). Treatment of CoCl2 and DMOG to Phd3−/− MDSPCs further increased the levels of HIF-1α, Pax7, and Glut1 proteins compared with untreated cells (Fig. 7D); these observations are positively correlated with increased binding of HIF-1α with the promoters of the Pax7 and Glut1 in CoCl2-treated cells (Fig. 7E). Intriguingly, neither CoCl2 nor DMOG induced an increase in mRNA levels of Pax7 in Phd3−/− MDSPCs, but Glut1 expression was induced (Fig. 7F). CoCl2 and DMOG-induced Pax7 expression was only observed in MRL/MpJ MDSPCs (Fig. 3B), indicating that HIF activators may have different mechanisms depending on cell type, albeit the precise mechanism is still unclear. Nevertheless, our results suggest that either pharmacological use of an HIF-1α activator (DMOG) or genetic ablation of HIF-1α inhibitor PHD3 stimulates the myogenic differentiation capacity of MRL/MpJ MDSPCs. This is most likely done through HIF-1α, which potentiates the stemness and undifferentiated state of multipotent MDSPCs in hypoxia through activation of the Notch signaling pathway and muscle stem cell markers.

Figure 7.

Inactivation of Phd3 stimulates expression of stem cell markers and myogenic capacity of MDSPCs. A) Levels of gene expression in WT and Phd3-knockout (Phd3−/−) MDSPCs during myogenic differentiation. B) Myotube formation analysis with MyHC staining in WT and Phd3-knockout MDSPCs with and without DMOG treatment prior to myogenic differentiation. Fusion index is shown in the right panel. Scale bars, 50 μm. C) Western blot showing the levels of proteins in whole-cell lysates of WT, Phd3-knockout, and MRL/MpJ MDSPCs cultured in proliferation medium under hypoxic condition. D) Western blot shows the levels of HIF-1α, Pax7, and Glut1 expression in untreated and treated Phd3−/− cells. E) ChIP assays for HIF-1α interaction with the promoter of Pax7 (left) and Glut1 (right) in untreated and CoCl2-treated Phd3−/− MDPSCs. F) Quantitative gene expression for Pax7 and Glut1 in untreated (NT) and treated MDPSCs. C, CoCl2; D, DMOG; KO, knockout; Myog, myogenin. Error bars indicate ±SEM from triplicates. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

The process of tissue regeneration and repair following injury, disease, and aging depends on the functionality of adult stem cells or progenitors, which includes their activation, proliferation, and differentiation capacities. These tissue-specific stem cells are maintained in their dormancy or quiescence in hypoxic conditions and are activated for tissue regeneration. Therefore, the presence of a large pool of quiescent and potent stem cells in hypoxia is a major determinant for tissue repair and regeneration. MRL/MpJ mice have been known to spontaneously repair various tissues, including cartilage, skin, and cornea, after injury (5, 52). However, the skeletal muscle healing capacity of this mouse strain is largely unknown, with the exception of 1 study that indicated an improvement in muscle healing and reduced fibrosis in dystrophic mice when bred with MRL/MpJ mice (6).

Recently, we have shown that MRL/MpJ mice possess a high skeletal muscle regenerative potential and that MDSPC function is significantly enhanced in MRL/MpJ mice relative to MDSPCs isolated from age-matched WT mice [Tseng et al. (40)]. Because we have previously isolated a population of MDSPCs, which have the ability to differentiate into various musculoskeletal tissues, including skeletal muscle (25, 28, 29), our current study investigated the function of MDSPCs with respect to HIF-1α in the MRL/MpJ mice.

Several studies have demonstrated that circulating serum factors have rejuvenating potential and improve stem cell function, most likely through paracrine activities and regulation of gene expression (10–14). We found that exogenous addition of MRL/MpJ mouse serum to WT mouse MDSPCs influences the expression levels of several genes. Importantly, expression levels of the stem cell marker Aldh1a1 were significantly increased by MRL/MpJ serum, thereby suggesting that MRL/MpJ serum might have the ability to improve stem cell function. MS analysis of circulating factors in WT compared with MRL/MpJ mouse sera revealed that the levels of serum proteins involved in glycolysis and antioxidative stress were elevated in the MRL/MpJ mice. Because these proteins are known to protect cells against inflammation, oxidative stress, and free radical accumulation as well as maintain the quiescent stem cells in hypoxia, it is conceivable that MRL/MpJ mice can be protected by these circulating factors upon various stresses.

HIF-1α is a hypoxia-inducible transcription factor that maintains the proliferation capacity and stemness of adult stem cells in hypoxia through activation of glycolytic, angiogenic, and survival genes (16, 53–56). Our data provide evidence of higher levels of HIF-1α expression and its target genes, including those encoding glycolytic factors, in MRL/MpJ relative to WT mouse MDSPCs, thereby allowing for maintenance of improved functional MRL/MpJ MDSPCs that promote the high regenerative capacity of this mouse strain. Zhang et al. (24) have shown that DMOG-treated MRL/MpJ mice have accelerated cartilage injury repair and increased levels of HIF-1α and stem cell markers, including Pax7, at the injury site. However, transcriptional activation of Pax7 by HIF-1α has not been previously reported. We have shown that HIF-1α positively regulates expression of Pax7 in MRL/MpJ MDSPCs through direct interaction with the promoter of this gene. Furthermore, there are 2 putative HIF response elements containing ACGTG (−1065 and +45 bp from the TSS).

The role of HIF-1α in myoblast differentiation and muscle tissue repair is still unclear. One study showed that HIF-1α promotes stem cell quiescence while down-regulating the WNT/β-Catenin pathway and inhibits myogenesis by degrading the early muscle-specific transcription factor MyoD1 (42), whereas another report has indicated that deletion of both HIF-1α and HIF-2α impairs satellite function and, subsequently, skeletal muscle regeneration (43). Furthermore, a very recent study indicated that activation of HIF-1α promotes myogenesis through the noncanonical WNT pathway (57). Our results demonstrated that inactivation of HIF-1α with the inhibitor PX487 during myogenic differentiation of WT and MRL/MpJ MDSPCs led to increase in myotube formation, which is consistent with other reports and suggests an inhibitory role of HIF-1α in myogenic differentiation. However, reducing the levels of HIF-1α in hypoxia led to decreased expression levels of myogenic stem cell marker genes. These data indicate that HIF-1α activity is necessary for proliferation and activation of MDSPCs prior to their differentiation during regeneration processes. We have recently reported that the number of Pax7 + cells and vessel density was higher in MRL/MpJ muscle than WT muscle (40), and HIF-1α and Pax7 protein levels were also increased in injured muscles of MRL/MpJ mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 4C). Nevertheless, these findings support a role for HIF-1α in activating Pax7+ muscle progenitors in MRL/MpJ mice, which may be a mechanism responsible for the high muscle repair capacity in MRL/MpJ mice (40). In normoxia, HIF-1α is degraded by PHDs, which hydroxylate HIF-1α and mediate ubiquitination-dependent degradation (46, 58). Levels of HIF-1α expression were higher in MDSPCs from Phd3−/− mice, which consequently stimulated expression of stem cell and myogenic markers as well as myogenic differentiation markers. This further corroborates our notion that higher HIF-1α levels might play a role in the increased potency of MDSPCs and the high skeletal muscle regenerative capacity of MRL/MpJ mice compared with WT mice. Adult stem cell potency and numbers decline during aging and disease progression, leading to their decreased regenerative potential. Therefore, HIF-1α may be considered a potential therapeutic candidate to improve tissue repair after injury, disease, and aging. Several studies have reported that HIF-1α promotes proliferation, self-renewal, and mobilization of hematopoietic and embryonic stem cells (59, 60). Our findings that HIF-1α stability with pharmacological use of HIF-1α activator may improve tissue regeneration by improving aged and defective stem cell function.

Our data show that HIF-1α promotes the high muscle healing capacity of MRL/MpJ mice by increasing the potency of MDSPCs. We demonstrated that treating MRL/MpJ mouse MDSPCs with DMOG and CoCl2 increased the expression of HIF-1α and target genes, including angiogenic and cell survival genes. We also observed that HIF-1α activates the expression of Pax7 through direct interaction with the Pax7 promoter. Furthermore, we showed higher myogenic potential of MDSPCs derived from Phd3−/− mice, which display higher stability of HIF-1α. Taken together, our results suggest that HIF-1α is a major determinant in the increased MDSPC function of MRL/MpJ mice through an enhancement of cell survival, proliferation, and, subsequently, myogenic differentiation. HIF-1α, together with antioxidants, should further potentiate the survival of adult stem cells in different stress conditions, enabling enhanced tissue repair processes for better tissue repair after injury, disease, and aging.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Ling Zhong (University of Texas Health Science Center) for microscopy work, and Dr. Mary A. Hall (University of Texas Health Science Center) for editorial assistance. This research was supported, in part, by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute on Aging (PO1AG043376, to J.H.) and the NIH National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (RO1AR065445, to J.H.), and institutional startup funding from the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, McGovern Medical School, University of Texas Health Science Center–Houston. Funding for H.E. comes from NIH National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants R01-DK097075 and R01-DK109574, POI-HL114457, R01-HL109233, and NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01-HL119837, and R01-HL133900. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- Aldh1a1

aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member A1

- Ccnd1

cyclin D1

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- DMOG

dimethyloxalylglycine

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- Glut1

glucose transporter 1

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- Hk2

hexokinase 2

- Id2

inhibitor of differentiation 2

- MDSPC

muscle-derived stem/progenitor cell

- MRL/MpJ

Murphy Roths Large

- MS

mass spectrometry

- MyHC

myosin heavy chain

- MyoD1

myogenic differentiation 1

- Nos2

NO synthase 2

- Pax

paired box

- PHD

prolyl hydroxylase

- Pkm

pyruvate kinase

- qPCR

quantitative PCR

- ShRNA

short hairpin RNA

- Sox9

sex-determining region Y-box 9

- TSS

transcriptional start site

- Vegf

vascular endothelial growth factor

- WT

wild type

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K. M. Sinha, C. Tseng, and A. Lu designed the study; K. M. Sinha, C. Tseng, and R. Andrews performed the experiments; P. Guo prepared the plasmid constructs; H. Pan isolated muscle-derived stem/progenitor cells; X. Gao provided mouse serum; K. M. Sinha and C. Tseng analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; H. Eltzschig provided prolyl hydroxylase 3–knockout mice; K. M. Sinha, C. Tseng, P. Guo, A. Lu, and J. Huard reviewed and finalized the manuscript; and the study was conducted under the supervision of J. Huard.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fitzgerald J. (2017) Enhanced cartilage repair in ‘healer’ mice-New leads in the search for better clinical options for cartilage repair. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 62, 78–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ueno M., Lyons B. L., Burzenski L. M., Gott B., Shaffer D. J., Roopenian D. C., Shultz L. D. (2005) Accelerated wound healing of alkali-burned corneas in MRL mice is associated with a reduced inflammatory signature. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46, 4097–4106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwiatkowski A., Piatkowski M., Chen M., Kan L., Meng Q., Fan H., Osman A. K., Liu Z., Ledford B., He J. Q. (2016) Superior angiogenesis facilitates digit regrowth in MRL/MpJ mice compared to C57BL/6 mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 473, 907–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zins S. R., Amare M. F., Anam K., Elster E. A., Davis T. A. (2010) Wound trauma mediated inflammatory signaling attenuates a tissue regenerative response in MRL/MpJ mice. J. Inflamm. (Lond.) 7, 25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heydemann A. (2012) The super super-healing MRL mouse strain. Front. Biol. (Beijing) 7, 522–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heydemann A., Swaggart K. A., Kim G. H., Holley-Cuthrell J., Hadhazy M., McNally E. M. (2012) The superhealing MRL background improves muscular dystrophy. Skelet. Muscle 2, 26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leonard C. A., Lee W. Y., Tailor P., Salo P. T., Kubes P., Krawetz R. J. (2015) Allogeneic bone marrow transplant from MRL/MpJ super-healer mice does not improve articular cartilage repair in the C57Bl/6 strain. PLoS One 10, e0131661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner N. J., Johnson S. A., Badylak S. F. (2010) A histomorphologic study of the normal healing response following digit amputation in C57bl/6 and MRL/MpJ mice. Arch. Histol. Cytol. 73, 103–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haigis M. C., Yankner B. A. (2010) The aging stress response. Mol. Cell 40, 333–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falick Michaeli T., Laufer N., Sagiv J. Y., Dreazen A., Granot Z., Pikarsky E., Bergman Y., Gielchinsky Y. (2015) The rejuvenating effect of pregnancy on muscle regeneration. Aging Cell 14, 698–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinha M., Jang Y. C., Oh J., Khong D., Wu E. Y., Manohar R., Miller C., Regalado S. G., Loffredo F. S., Pancoast J. R., Hirshman M. F., Lebowitz J., Shadrach J. L., Cerletti M., Kim M. J., Serwold T., Goodyear L. J., Rosner B., Lee R. T., Wagers A. J. (2014) Restoring systemic GDF11 levels reverses age-related dysfunction in mouse skeletal muscle. Science 344, 649–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villeda S. A., Plambeck K. E., Middeldorp J., Castellano J. M., Mosher K. I., Luo J., Smith L. K., Bieri G., Lin K., Berdnik D., Wabl R., Udeochu J., Wheatley E. G., Zou B., Simmons D. A., Xie X. S., Longo F. M., Wyss-Coray T. (2014) Young blood reverses age-related impairments in cognitive function and synaptic plasticity in mice. Nat. Med. 20, 659–663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conboy I. M., Conboy M. J., Wagers A. J., Girma E. R., Weissman I. L., Rando T. A. (2005) Rejuvenation of aged progenitor cells by exposure to a young systemic environment. Nature 433, 760–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corrado C., Raimondo S., Chiesi A., Ciccia F., De Leo G., Alessandro R. (2013) Exosomes as intercellular signaling organelles involved in health and disease: basic science and clinical applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 5338–5366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park H. S., Kim J. H., Sun B. K., Song S. U., Suh W., Sung J. H. (2016) Hypoxia induces glucose uptake and metabolism of adipose-derived stem cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 14, 4706–4714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Miguel M. P., Alcaina Y., de la Maza D. S., Lopez-Iglesias P. (2015) Cell metabolism under microenvironmental low oxygen tension levels in stemness, proliferation and pluripotency. Curr. Mol. Med. 15, 343–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benita Y., Kikuchi H., Smith A. D., Zhang M. Q., Chung D. C., Xavier R. J. (2009) An integrative genomics approach identifies Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1 (HIF-1)-target genes that form the core response to hypoxia. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 4587–4602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haskó G., Antonioli L., Cronstein B. N. (2018) Adenosine metabolism, immunity and joint health. Biochem. Pharmacol. 151, 307–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leibovich S. J., Chen J. F., Pinhal-Enfield G., Belem P. C., Elson G., Rosania A., Ramanathan M., Montesinos C., Jacobson M., Schwarzschild M. A., Fink J. S., Cronstein B. (2002) Synergistic up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in murine macrophages by adenosine A(2A) receptor agonists and endotoxin. Am. J. Pathol. 160, 2231–2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montesinos M. C., Shaw J. P., Yee H., Shamamian P., Cronstein B. N. (2004) Adenosine A(2A) receptor activation promotes wound neovascularization by stimulating angiogenesis and vasculogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 164, 1887–1892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan Q., Bleiziffer O., Boos A. M., Sun J., Brandl A., Beier J. P., Arkudas A., Schmitz M., Kneser U., Horch R. E. (2014) PHDs inhibitor DMOG promotes the vascularization process in the AV loop by HIF-1a up-regulation and the preliminary discussion on its kinetics in rat. BMC Biotechnol. 14, 112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill P., Shukla D., Tran M. G., Aragones J., Cook H. T., Carmeliet P., Maxwell P. H. (2008) Inhibition of hypoxia inducible factor hydroxylases protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 19, 39–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gumucio J. P., Flood M. D., Bedi A., Kramer H. F., Russell A. J., Mendias C. L. (2017) Inhibition of prolyl 4-hydroxylase decreases muscle fibrosis following chronic rotator cuff tear. Bone Joint Res. 6, 57–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y., Strehin I., Bedelbaeva K., Gourevitch D., Clark L., Leferovich J., Messersmith P. B., Heber-Katz E. (2015) Drug-induced regeneration in adult mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 290ra92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao X., Usas A., Lu A., Tang Y., Wang B., Chen C. W., Li H., Tebbets J. C., Cummins J. H., Huard J. (2013) BMP2 is superior to BMP4 for promoting human muscle-derived stem cell-mediated bone regeneration in a critical-sized calvarial defect model. Cell Transplant. 22, 2393–2408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao X., Usas A., Proto J. D., Lu A., Cummins J. H., Proctor A., Chen C. W., Huard J. (2014) Role of donor and host cells in muscle-derived stem cell-mediated bone repair: differentiation vs. paracrine effects. FASEB J. 28, 3792–3809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao X., Usas A., Tang Y., Lu A., Tan J., Schneppendahl J., Kozemchak A. M., Wang B., Cummins J. H., Tuan R. S., Huard J. (2014) A comparison of bone regeneration with human mesenchymal stem cells and muscle-derived stem cells and the critical role of BMP. Biomaterials 35, 6859–6870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuroda R., Usas A., Kubo S., Corsi K., Peng H., Rose T., Cummins J., Fu F. H., Huard J. (2006) Cartilage repair using bone morphogenetic protein 4 and muscle-derived stem cells. Arthritis Rheum. 54, 433–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li H., Lu A., Tang Y., Beckman S., Nakayama N., Poddar M., Hogan M. V., Huard J. (2016) The superior regenerative potential of muscle-derived stem cells for articular cartilage repair is attributed to high cell survival and chondrogenic potential. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 3, 16065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumoto T., Cooper G. M., Gharaibeh B., Meszaros L. B., Li G., Usas A., Fu F. H., Huard J. (2009) Cartilage repair in a rat model of osteoarthritis through intraarticular transplantation of muscle-derived stem cells expressing bone morphogenetic protein 4 and soluble Flt-1. Arthritis Rheum. 60, 1390–1405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng B., Cao B., Crisan M., Sun B., Li G., Logar A., Yap S., Pollett J. B., Drowley L., Cassino T., Gharaibeh B., Deasy B. M., Huard J., Péault B. (2007) Prospective identification of myogenic endothelial cells in human skeletal muscle. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 1025–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sinha K. M., Yasuda H., Coombes M. M., Dent S. Y., de Crombrugghe B. (2010) Regulation of the osteoblast-specific transcription factor Osterix by NO66, a Jumonji family histone demethylase. EMBO J. 29, 68–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang K. Y., Yamada S., Izumi H., Tsukamoto M., Nakashima T., Tasaki T., Guo X., Uramoto H., Sasaguri Y., Kohno K. (2018) Critical in vivo roles of WNT10A in wound healing by regulating collagen expression/synthesis in WNT10A-deficient mice. PLoS One 13, e0195156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen H. C., Lee J. T., Shih C. P., Chao T. T., Sytwu H. K., Li S. L., Fang M. C., Chen H. K., Lin Y. C., Kuo C. Y., Wang C. H. (2015) Hypoxia induces a metabolic shift and enhances the stemness and expansion of cochlear spiral ganglion stem/progenitor cells. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 359537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simon M. C., Keith B. (2008) The role of oxygen availability in embryonic development and stem cell function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 285–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaufman D. S. (2010) HIF hits Wnt in the stem cell niche. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 926–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mannello F., Medda V., Tonti G. A. (2011) Hypoxia and neural stem cells: from invertebrates to brain cancer stem cells. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 55, 569–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J. (2003) Regulation of angiogenesis by hypoxia: role of the HIF system. Nat. Med. 9, 677–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rigamonti E., Touvier T., Clementi E., Manfredi A. A., Brunelli S., Rovere-Querini P. (2013) Requirement of inducible nitric oxide synthase for skeletal muscle regeneration after acute damage. J. Immunol. 190, 1767–1777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tseng C., Sinha K., Pan H., Cui Y., Guo P., Lin C. Y., Yang F., Deng Z., Eltzschig H. K., Lu A., Huard J. (2019) Markers of accelerated skeletal muscle regenerative response in Murphy Roths large mice: characteristics of muscle progenitor cells and circulating factors. Stem Cells 37, 357–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Befani C., Mylonis I., Gkotinakou I. M., Georgoulias P., Hu C. J., Simos G., Liakos P. (2013) Cobalt stimulates HIF-1-dependent but inhibits HIF-2-dependent gene expression in liver cancer cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 45, 2359–2368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Majmundar A. J., Lee D. S., Skuli N., Mesquita R. C., Kim M. N., Yodh A. G., Nguyen-McCarty M., Li B., Simon M. C. (2015) HIF modulation of Wnt signaling regulates skeletal myogenesis in vivo. Development 142, 2405–2412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang X., Yang S., Wang C., Kuang S. (2017) The hypoxia-inducible factors HIF1α and HIF2α are dispensable for embryonic muscle development but essential for postnatal muscle regeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 5981–5991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jash S., Adhya S. (2015) Effects of transient hypoxia versus prolonged hypoxia on satellite cell proliferation and differentiation in vivo. Stem Cells Int. 2015, 961307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun K., Halberg N., Khan M., Magalang U. J., Scherer P. E. (2013) Selective inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α ameliorates adipose tissue dysfunction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 904–917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Myllyharju J., Koivunen P. (2013) Hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl 4-hydroxylases: common and specific roles. Biol. Chem. 394, 435–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quattrocelli M., Costamagna D., Giacomazzi G., Camps J., Sampaolesi M. (2014) Notch signaling regulates myogenic regenerative capacity of murine and human mesoangioblasts. Cell Death Dis. 5, e1448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu W., Wen Y., Bi P., Lai X., Liu X. S., Liu X., Kuang S. (2012) Hypoxia promotes satellite cell self-renewal and enhances the efficiency of myoblast transplantation. Development 139, 2857–2865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wen Y., Bi P., Liu W., Asakura A., Keller C., Kuang S. (2012) Constitutive Notch activation upregulates Pax7 and promotes the self-renewal of skeletal muscle satellite cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 2300–2311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.González N., Moresco J. J., Cabezas F., de la Vega E., Bustos F., Yates J. R., III, Olguín H. C. (2016) Ck2-dependent phosphorylation is required to maintain Pax7 protein levels in proliferating muscle progenitors. PLoS One 11, e0154919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bustos F., de la Vega E., Cabezas F., Thompson J., Cornelison D. D., Olwin B. B., Yates J. R., III, Olguín H. C. (2015) NEDD4 regulates PAX7 levels promoting activation of the differentiation program in skeletal muscle precursors. Stem Cells 33, 3138–3151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rai M. F., Sandell L. J. (2014) Regeneration of articular cartilage in healer and non-healer mice. Matrix Biol. 39, 50–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Palomäki S., Pietilä M., Laitinen S., Pesälä J., Sormunen R., Lehenkari P., Koivunen P. (2013) HIF-1α is upregulated in human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 31, 1902–1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang C. C., Sadek H. A. (2014) Hypoxia and metabolic properties of hematopoietic stem cells. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 20, 1891–1901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aranha A. M., Zhang Z., Neiva K. G., Costa C. A., Hebling J., Nör J. E. (2010) Hypoxia enhances the angiogenic potential of human dental pulp cells. J. Endod. 36, 1633–1637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harms K. M., Li L., Cunningham L. A. (2010) Murine neural stem/progenitor cells protect neurons against ischemia by HIF-1alpha-regulated VEGF signaling. PLoS One 5, e9767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cirillo F., Resmini G., Ghiroldi A., Piccoli M., Bergante S., Tettamanti G., Anastasia L. (2017) Activation of the hypoxia-inducible factor 1α promotes myogenesis through the noncanonical Wnt pathway, leading to hypertrophic myotubes. FASEB J. 31, 2146–2156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van der Horst I. W., Rajatapiti P., van der Voorn P., van Nederveen F. H., Tibboel D., Rottier R., Reiss I., de Krijger R. R. (2011) Expression of hypoxia-inducible factors, regulators, and target genes in congenital diaphragmatic hernia patients. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 14, 384–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Speth J. M., Hoggatt J., Singh P., Pelus L. M. (2014) Pharmacologic increase in HIF1α enhances hematopoietic stem and progenitor homing and engraftment. Blood 123, 203–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takubo K., Goda N., Yamada W., Iriuchishima H., Ikeda E., Kubota Y., Shima H., Johnson R. S., Hirao A., Suematsu M., Suda T. (2010) Regulation of the HIF-1alpha level is essential for hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 7, 391–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]