Abstract

Effective management of publicly funded services matches the provision of needed services with cost-efficient payment methods. Payment systems that recognize differences in care needs (eg, case-mix systems) allow for greater proportions of available funds to be directed to providers supporting individuals with more needs. We describe a new way to allocate funds spent on adults with intellectual disabilities (ID) as part of a system-wide Medicaid payment reform initiative in Arkansas. Analyses were based on population-level data for persons living at home, collected using the interRAI ID assessment system, which were linked to paid service claims. We used automatic interactions detection to sort individuals into unique groups and provide a standardized relative measure of the cost of the services provided to each group. The final case-mix system has 33 distinct final groups and explains 26% of the variance in costs, which is similar to other systems in health and social services sectors. The results indicate that this system could be the foundation for a future case-mix approach to reimbursement and stand the test of “fairness” when examined by stakeholders, including parents, advocates, providers, and political entities.

Keywords: Assessment, intellectual disability, interRAI, payment systems

Effective management of health and social services programs matches the appropriate provision of needed services with cost-efficient methods of paying for these services. In many health care sectors, beginning with acute care hospitals1 and then nursing homes,2,3 the development of need measures—often termed “acuity” or “case mix”—has led to improved governmental payment systems that explicitly recognize differing care needs across a given population and direct a greater proportion of available funding to individuals with “heavier” needs.

Case-mix systems in the health arena vary in the measurement of resource use, identification of personal characteristics, and overall structure. Initial work carried out in acute care hospitals, called diagnosis-related groups, used an easily obtained but coarse measure of resource use (hospital length of stay) and a limited available set of patient descriptors (primarily diagnoses, procedures, age, etc—but without measures of physical of cognitive function) to design an episode-based payment system. In nursing homes, using length of stay to represent resource use made little sense; rather, measurement of the per diem cost via staff time-and-motion studies added substantially to the complexity of developing a case-mix system. However, the emergence of robust assessment systems—and, in particular, the United States National Nursing Home Resident Assessment Instrument/Minimum Data Set4,5—provided a broad and accurate source of person-level characteristics for the development of the nursing home Resource Utilization Groups2 system (most recently, Version IV).5 Parallel systems have been implemented in home care6 and other sectors.7,8

All these referenced systems are designed to identify unique groups of individuals with similar resource use. An alternative approach, an “index” system such as the Illinois Determination of Need,9 accumulates specific weights (eg, “points”) to individual characteristics or service provision and typically is derived from statistical regression analysis. One major problem with an index approach is the awkwardness of exploring multiple, high-order statistical interactions that often occur when a particular characteristic is important only for a certain type of individual, but not for others (eg, behavior problems may not be as time-consuming for individuals with little functional capability). Developing groups based on classification analysis (eg, automatic interactions detection, or AID)10 directly addresses this issue, while also providing clinically meaningful and distinct groups of individuals. Associated with each unique group is a case-mix index (CMI) that reflects the relative resource use among persons in that particular group. For instance, a person in a group with a CMI of 1.20 has, on average, 20% higher resource use than a person in a group with a CMI of 1.00.

When we use case-mix algorithms prospectively in payment systems, they can change the behavior of service providers by creating incentives and disincentives. More specifically, providers may seek out certain types of persons, use certain types of interventions, or search for clinical signs associated with higher reimbursement levels. Accordingly, in developing a case-mix system, we must consider not only how a given variable influences the study results, but also how it will influence day-to-day service delivery if used as a basis for reimbursement. Therefore, in addition to statistical issues (eg, variance explanation, homogeneity of groups, size of terminal groups, and clinical appropriateness), system “gaming” is also an important consideration.2 As such, it is critical to consider carefully whether to include measures that rely on subjective interpretation (eg, happy, cheerful expressions) and service variables (eg, the provision of sensory simulation).

As part of a system-wide Medicaid payment reform initiative in Arkansas, the Division of Developmental Disability Services (ARDDS) asked us to investigate a new way to allocate the funds spent on adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) in home and community settings, using a case-mix approach. This article describes the development of the case-mix methodology for this target population.

Methods

Study sample

In late 2013, ARDDS undertook a statewide census of the characteristics and needs of all current clients, across all living settings. A total of 4618 adults were assessed: 2700 living in private homes (eg, alone, with parents, spouse, siblings, relatives, or nonrelatives); 231 sharing a private home with staff (called “staff homes” in Arkansas); 419 in group homes; 1249 in institutions, including state Human Development Centers and privately operated intermediate care facilities (ICF) for IDD; 2 who were homeless; and 17 coded as living in “other” arrangements. We use these data to describe the characteristics of the population, including the case-mix distribution across all settings.

To derive a “cost” variable—the dependent variable to be explained in the case-mix analysis—we linked each assessment record with paid claims from July 2011 to June 2013 for specific home and community-based services. At the request of ARDDS, we derived the case-mix classification system using only the 2700 persons living in private homes, of whom 2525 (93.5%) had usable claims. For clarity, in the derivation of our classification system, we thus excluded all persons who resided in licensed group homes and ICF/IDD for any part of the research window, as most care in these settings is paid on a bundled, per diem rate basis and could not be attributed to individual characteristics. While those living in staff homes (n = 223 with usable claims) were also excluded from derivation of the classification system at the request of ARDDS, they were included in the calculation of CMIs, so as to include all settings where claims would be most representative of the services people receive in their own homes.

Instrumentation

The ARDDS used the interRAI intellectual disabilities (interRAI ID)11 instrument to assess all service users. This tool has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties12 and is part of the interRAI integrated suite of assessment instruments.13 Individual interRAI instruments have been adopted across 26 US states and 3 dozen countries worldwide; New York State and Israel currently mandate the interRAI ID.

InterRAI ID assessment items relate to major life domains, including individuals’ strengths, preferences, employment status, social life, natural supports (ie, unpaid caregivers, like family and friends), functioning, communication, cognition, behavior, and physical and mental health. Individual items are combined in algorithms that inform on status and trigger action. The most influential scale here was the functional hierarchy.14 This scale represents an amalgamation of the instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) hierarchy and activities of daily living (ADL) hierarchy,15 and informs on the individual’s ability to independently perform ADL (ie, personal hygiene, locomotion, toilet use, and eating) and IADL (ie, meal preparation, housework, managing finances, and transportation). (The full logic for the calculation of this scale is available from the authors.) Evidence of scale validity (eg, associative analyses with cognitive status, hours of informal and formal care) is provided elsewhere. Other scales of particular importance to this work included the Cognitive Performance Scale,16 the Depression Rating Scale,17 and the Aggressive Behavior Scale.18 These scales have been shown to be valid for persons with intellectual disability and for the interRAI ID.19

Resource use

We matched each assessment record to 2 years of Medicaid paid service claims (July 2011-June 2013). From all service types, ARDDS selected a specific set of Medicaid state plan and waiver services, including supportive living, environmental modifications (eg, house ramps, enlarged doors), adaptive equipment, specialized medical supplies, respite, and consultation. After the derivation based on these selected claim types, we tested the resulting system on a revised set of claims we preferred, adding claims for crisis intervention to the prior list and dropping those for environmental modifications. (A list of the specific services considered and HCPCC codes is available from the authors.) These adjustments were associated with quite rare cost centers, and reduced the per diem cost by only $0.04 (0.03%) per day; nevertheless, we included them in the calculation of the CMIs reported here. We considered including the time spent by unpaid caregivers (natural supports), but this did not improve the models; unpaid caregiving/natural supports was not associated with formal care either positively or negatively. Furthermore, no personal characteristics were predictive of natural support/caregiver time. Omitting unpaid care time from our model also makes the intended use of the case-mix system—to help assign resources based on the person’s needs—substantially easier.

Analytic Methods

We used AID within the SAS Enterprise Guide (Data Miner analytic package, Version 4.3) to sort individuals into unique, clinically relevant groups (the classification system) and provide a standardized relative measure of the cost of the services provided to each group (the CMIs). In AID clustering, the full set of data points within an assessment is partitioned recursively into subgroups by a set of splits. Each split is based on the values of a particular independent variable (person characteristic), and chosen to maximize the prediction (ie, variance explanation) of the dependent variable (resource use). A major advantage of this approach is that the resulting groups reflect specific person characteristics that related to resource use in different subpopulations—eg, persons with higher or lower levels of instances of physical abuse (eg, others were hit, shoved, or scratched). At every split, we considered all possible variables in the assessment data; however, AID allows us to use only measures that make “clinical” sense. We also avoided variables that characterized the setting (eg, type of residence), measures that would not make sense in an institutional setting (eg, constant observation), and those that could provide negative incentives if part of a resource allocation system (eg, mechanical restraint). Our prior experience in developing case-mix systems showed that it is not always advantageous to choose the variable that provides the most variance explanation, especially in early splits of the whole sample; thus, we developed multiple analyses considering a variety of initial splits. There were sufficient data to allow us to perform the initial analysis on a subsample of three-quarters of the usable sample, and independently validate it on the remaining one-quarter validation sample. However, we also used the full sample of community-living adults to derive the CMIs, including people living in staff homes, and included the additional claim types mentioned previously. The CMIs were calculated as the mean cost for all observations in a particular group, normed to a relative value by dividing by the mean cost for a selected, numerous group. Finally, we used the data set of all assessments—including those in institutional settings and those with no claims records—to examine the distribution of the resulting groups, dubbed “Case-Mix Groups for Developmental Disability” (CMGDD), across all Arkansas settings.

We did not perform statistical tests for comparisons of the characteristics of care recipients, given that data are population level; rather, we report on the substantiality of any differences.

Results

Table 1 shows selected characteristics of the overall population by residential setting. The average age was approximately 38 years, highest in group homes, institutions, and “other” living arrangements and lowest in staff homes. There were slightly more men than women in all settings except institutions. The qualifying diagnoses varied across settings, although “intellectual disability” (cause unspecified) was the most prevalent in all settings. There were more individuals with cerebral palsy and Down syndrome in private homes and staff homes; autism was more frequent in private homes. Institutions had the largest proportion of individuals with the most severe documented levels of intellectual impairment (75%).

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of persons, by residential setting.

| Private home | Staff home | Group home | Institutions | Other | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 2700 | 231 | 416 | 1229 | 19 | 4618 |

| % assessments | 58.5 | 5.0 | 9.1 | 27.1 | 0.4 | 100.0 |

| Mean age, in years | 37.0 | 35.0 | 47.2 | 43.7 | 43.8 | 39.6 |

| % female | 41.1 | 45.7 | 51.2 | 40.2 | 42.1 | 42.0 |

| Qualifying diagnosis | ||||||

| Intellectual disability | 68.7% | 74.2% | 87.8% | 94.1% | 94.7% | 77.8% |

| Down syndrome | 5.8% | 7.6% | 3.4% | 1.9% | 0.0% | 4.6% |

| Autism spectrum | 8.5% | 4.4% | 0.5% | 1.9% | 0.0% | 5.7% |

| Cerebral palsy | 13.4% | 12.4% | 6.3% | 1.9% | 0.0% | 9.5% |

| Severe or profound level of intellectual impairment | 24.8% | 39.5% | 24.2% | 74.4% | 26.3% | 39.8% |

| Substantial cognitive impairment (CPS ⩾ 4) | 37.2% | 56.7% | 30.6% | 66.3% | 26.3% | 45.4% |

| Substantial physical dysfunction (functional hierarchy ⩾ 6) | 55.1% | 67.1% | 46.1% | 71.1% | 42.1% | 59.2% |

| Severe aggressive behavior (ABS ⩾ 6) | 10.2% | 15.6% | 6.4% | 8.3% | 0.0% | 9.6% |

| Depression (DRS ⩾ 3) | 55.1% | 55.4% | 55.4% | 30.4% | 47.4% | 48.4% |

Abbreviations: ABS, Aggressive Behavior Scale; CPS, Cognitive Performance Scale; DRS, Depression Rating Scale.

Approximately 45% of Arkansas service recipients had substantial cognitive impairment and about 59% had substantial functional impairments. Rates of substantial cognitive impairment and functional dependence were highest for persons living in institutions; this setting also had the lowest level of depression. Persons living in staff homes had the highest rate of severe aggressive behavior.

Case-Mix Classification System

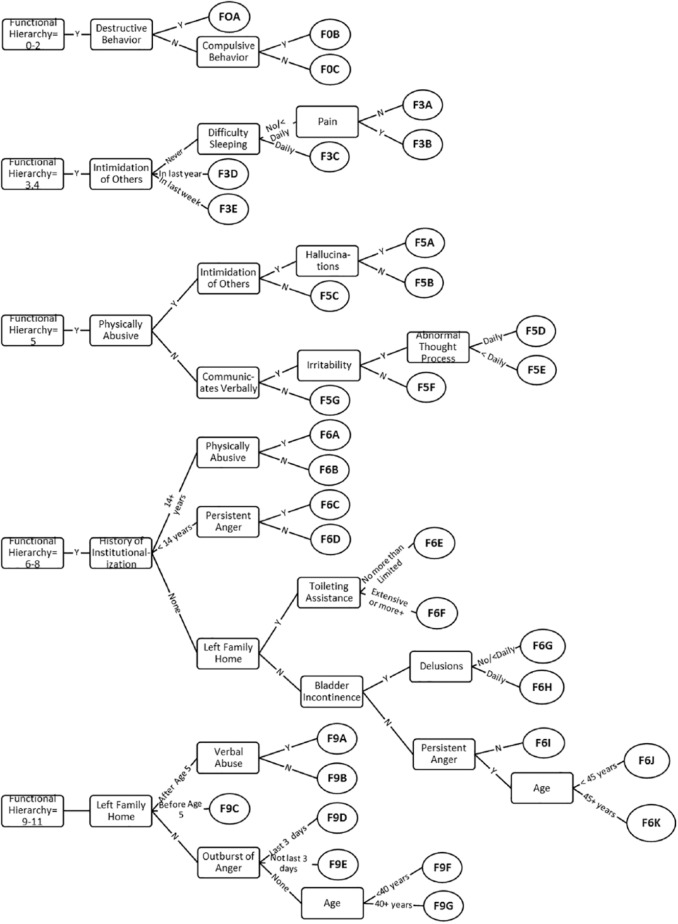

Using the 2700 individuals in their own homes, for which we had both descriptive characteristics and per diem costs, we modeled a number of different personal characteristics as initial “splits” to define groups, including ARDDS qualifying diagnosis, level of cognitive impairment, and functioning. By far, the most powerful variable in explaining per diem costs was the functional hierarchy. When split into 5 distinct categories (Figure 1), the functional hierarchy explained 10.2% of the variance in our cost variable.

Figure 1.

The Case-Mix Groups for Developmental Disability classification system.

Subsequent splits were made using personal characteristics that had both statistical significance and real-world meaning, including daily aggressive behavior, frequent outbursts of anger, intimidation of others (eg, threatening gestures, explicit threats of violence), communication (use of verbal vs nonverbal communication), frequency and type of psychiatric symptoms, whether the person left their family home for another residential setting (eg, on their own, in an institution, in a group home), and functional characteristics (eg, continence and toileting). The final CMGDD system has 33 distinct final groups, represented by the ovals in Figure 1, and named in part by the functional hierarchy group to which they belong.

In the derivation sample of only persons in private homes, the CMGDD system explained 30.0% of the variance in total per diem costs. This was somewhat lower in the validation sample (24.7%), potentially in part from the smaller sample size. When we applied the system to the combined sample of all persons in private homes, the variance explanation was 26.9%, very close to the variance explanation when applied to persons in both private homes and staff homes (26.2%).

Case-mix weights

To develop the CMIs, we applied the system to all 2597 persons living in the community, both in private homes and in staff homes, who had sufficiently complete data to assign to groups. We normalized the mean per diem costs for each group by dividing by the mean cost for a frequent group with per diem cost near the mean for the population. We chose the group F6G, with 254 individuals and a mean per diem cost of $147.87, to be normalized to 1.00 (see the row in bold in Table 2). Note that the choice of a normalization constant has no effect on any payment system or other use of CMIs, as CMIs represent relative values only.

Table 2.

CMGDD groups, CMIs, and CV.

| CMGDD | N | Mean per diem cost | CMI | CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F0A | 24 | $109.32 | 0.74 | 0.69 |

| F0B | 13 | $108.60 | 0.73 | 0.51 |

| F0C | 86 | $66.61 | 0.45 | 0.79 |

| F3A | 180 | $90.45 | 0.61 | 0.58 |

| F3B | 96 | $112.23 | 0.76 | 0.49 |

| F3C | 26 | $134.92 | 0.91 | 0.66 |

| F3D | 55 | $131.64 | 0.89 | 0.62 |

| F3E | 21 | $184.66 | 1.25 | 0.42 |

| F5A | 40 | $249.19 | 1.69 | 0.38 |

| F5B | 105 | $181.80 | 1.23 | 0.52 |

| F5C | 58 | $151.43 | 1.02 | 0.51 |

| F5D | 19 | $179.49 | 1.21 | 0.38 |

| F5E | 262 | $133.86 | 0.91 | 0.52 |

| F5F | 164 | $113.30 | 0.77 | 0.53 |

| F5G | 19 | $183.91 | 1.24 | 0.45 |

| F6A | 21 | $264.61 | 1.79 | 0.38 |

| F6B | 28 | $185.94 | 1.26 | 0.39 |

| F6C | 56 | $201.96 | 1.37 | 0.35 |

| F6D | 83 | $166.91 | 1.13 | 0.38 |

| F6E | 161 | $170.28 | 1.15 | 0.39 |

| F6F | 81 | $222.31 | 1.50 | 0.28 |

| F6G | 254 | $147.87 | 1.00 | 0.48 |

| F6H | 14 | $214.67 | 1.45 | 0.67 |

| F6I | 187 | $112.53 | 0.76 | 0.47 |

| F6J | 37 | $137.86 | 0.93 | 0.50 |

| F6K | 82 | $147.11 | 0.99 | 0.40 |

| F9A | 23 | $236.74 | 1.60 | 0.41 |

| F9B | 75 | $225.09 | 1.52 | 0.32 |

| F9C | 43 | $182.51 | 1.23 | 0.40 |

| F9D | 39 | $202.54 | 1.37 | 0.43 |

| F9E | 48 | $193.89 | 1.31 | 0.48 |

| F9F | 161 | $157.05 | 1.06 | 0.48 |

| F9G | 36 | $197.58 | 1.34 | 0.51 |

| Total | 2597 | $150.07 | 1.01 | 0.55 |

Abbreviations: CMGDD, Case-Mix Groups for Developmental Disability; CMI, case-mix index; CV, coefficient of variation.

The CMIs had a 4-to-1 range. Persons with a functional hierarchy score of 6 to 8, with a lifetime history of 14 or more years in an institutional setting, and with a known history of being physically abused, are in the most expensive group (groups F6A, with CMI = 1.79). In contrast, individuals with no ADL or IADL impairment and neither destructive (eg, throwing objects) nor compulsive behavior are in the least expensive group (group F0C, with CMI = 0.45). Overall, the CMGDD system reduced the coefficient of variation (CV) for groups, a measure of the dispersion of costs; only 6 groups had CVs larger than that of the total population.

Finally, we applied the classification system to all ARDDS service users, including those in group homes and institutions. It can be expected that the costs of care in these 2 other settings are substantially different (eg, institutional settings will have costs for running the physical plant, such as heating, electricity, depreciation of the building, and that all or almost all care will be by paid workers). However, if some characteristic is shown to be associated with increased need for care in a home setting, it is reasonable to assume that it will be associated with increased need for care in an institutional setting. Thus, applying a case-mix approach can provide some insight into the types of individuals cared for in an allied setting. Using the CMIs derived for those persons who actually lived in home and community settings, as described previously, we calculated the mean case-mix for persons in each setting, to create an “apples to apples” measure of relative acuity across all persons in all settings.

We find that there are substantially more individuals in the higher cost groups in institutions. Correspondingly, with the average CMI for home setting set at 1.00, as described earlier, the average CMI for institutions is 1.26 and that for group homes is 1.06 (not shown). However, there also is considerable overlap: every case-mix “type” of person is found in all 4 settings.

Discussion

The ARDDS serves persons both in institutional and in community settings. We began with modeling a case-mix system for the community setting and applied the system to the population living in institutional settings, to categorize the relative complexity and resource intensity of the state population across all settings.

The CMGDD case-mix classification system explains 26% of the variance in costs for a specified array of home and community-based services provided to persons living in private homes and staff homes in Arkansas. This variance explanation is similar to results obtained for systems in other populations and settings.2,6 Specific to the field of IDD, a study in Louisiana used a different derivation methodology and instrumentation (ie, the Supports Intensity Scale)20 to develop a resource utilization system. This model explained 45.6% of variance in costs, although only 15.6% was explained by personal characteristics as measured in the assessment; the remaining 30% of the variance in costs was attributable to the type of residential setting in which the person lived.21 We intentionally did not consider residential settings in our analysis (and do not have the cost measures to replicate the Louisiana study), instead focusing solely on person-level characteristics and needs. As such, the CMGDD system ensures that we base resource allocation on what individuals need, rather than where they live. The CMGDD has a 4-to-1 range in costs and is able to identify individuals with very costly needs, although they are rare.

As the case-mix groups and the CMIs were both derived based on Arkansas costs for a selected group of services, we do not know whether they fit the cost expenditures of other jurisdictions. However, other governments might wish to retain the CMGDD grouping, but derive their own CMIs using a different set of cost centers. The choice of which cost centers to include can be complicated, however. As an example, should one include claims for environmental modifications? Such reimbursement must be in any payment system, but not the part affected by case mix. In Arkansas, 18 (0.1%) of 2525 persons claimed costs for environment modifications, each with an average annual cost of $2433. The effect of this in the payment for each individual would be to add less than 5 cents ($0.048) to everyone’s per diem payment. A small agency that had one of these individuals would receive insufficient funds to pay for the environmental modification, while other agencies not providing anyone with an environmental modification would get a bonus 5 cents per client per day. It makes more sense to pay any agency that provides environmental modifications outside of the case-mix system, on a case-by-case basis.

Overall, the average CMI is lowest for persons residing in private homes and highest for persons in institutions and staff homes. It is not surprising to see that as one moves from the least restrictive setting (private homes) to the most restrictive (institutions), persons are more often assigned to higher case-mix groups. In the community, those living in staff homes have the highest CMI, which is not surprising given that they have much higher rates of severe cognitive impairment, functional dependence, and severe aggression than do persons living in private homes. Of more interest, however, is that in both community and more restrictive settings, the system identifies individuals in each of the 33 case-mix groups. For example, whereas 4.2% of the persons in private homes are classified into the 2 least costly groups, 1.4% of persons in institutions also fall into these groups; similarly, 3.4% of persons in private homes are in the 2 most costly groups.

This underscores an important point well known to advocates but poorly understood by the general public: individuals with complex needs are being supported in the community, and persons with lower levels of need are living in institutional settings. There is a large body of evidence that demonstrates improvements in quality of life and functioning among adults with IDD who have transitioned from institutional to community settings.22,23 Such evidence has supported commitment to deinstitutionalization in government policies.24 The information in this study provides another opportunity to rethink how and where individuals with complex needs are supported, in discussions both with policymakers and with the person’s family and friends of their choosing, to promote person-centeredness and social inclusion.

Natural supports, usually family and friends, provide substantial care to adults with IDD. Whether measures of that care should be incorporated into a case-mix system, and how best to do that, remains a controversy. Future work should examine how best to include natural supports in the context of a case-mix system for adults with IDD. Furthermore, while this article described the development of a case-mix system for adults with IDD, ARDDS also sought a system for children; we will describe this work in a future publication. Given that children with IDD grow into adults with IDD, there is some value in further examining how and whether these systems relate to one another.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that the CMGDD classification system can be the foundation for a future case-mix approach to reimbursement, to adjust overall service expenditures to account more accurately and equitably for differences in need and capacity across the population of eligible individuals. With a link of characteristics to actual costs and a scientific basis, this system can stand the test of “fairness” when examined by stakeholders, including parents, advocates, professional carers, and political entities.

While the CMGDD system provides a reasonable match to expected average costs at the level of the individual, actual care decisions need to be based on consideration of an individual’s wishes and desires, as well as the availability of informal support and the acceptability of specific paid services. Thus, at the level of the individual, CMGDD is a “decision aid” rather than a strict prescription. At the level of an organization, the fit of CMGDDs to overall resource allocation will improve substantially, as variations at the individual level will “average out” across the enrolled population as a whole.

For publicly funded services, the mandate to assure care must balance against the necessarily limited public funds available. In the US, as in many other nations, mounting pressure to improve the overall efficiency of health services systems has led government agencies away from traditional “fee for service” reimbursement of individual providers to capitated “managed care” models that shift financial risk away from themselves and down to the provider level. Government authorities have loosened the heavy regulatory overlay that accompanied the traditional funding model in return for acceptance of prospective funding that providers (or those who are otherwise responsible for purchasing care) can deploy creatively and in thrifty ways. In exchange, providers are expected to shoulder more of the risk associated with meeting expanded demand. Case-mix offers a method that best ties the projected differential costs of services for discrete categories of individuals to their assessed needs.

The calculation of the CMGDD is a useful byproduct of using the interRAI ID to inform person-centered support planning: there is no additional assessment needed. This is often not the situation with other case-mix systems. For example, the State of Louisiana needed to create a supplement when it adopted the Supports Intensity Scale (called the LA Plus) to capture information needed to support planning and resource allocation. Similarly, in Ontario, the Application for Developmental Services and Supports (ADSS) was created for use alongside the Supports Intensity Scale.25 Such multiple assessment processes subject the person and their natural supports to overlapping, expensive, and potentially intrusive assessment processes. The multiple uses of information generated from the interRAI ID, in conjunction with its established psychometric properties, position it well to help inform individuals, families, organizations, administrators, and decision-makers on the needs of service users with IDD and their associated costs.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Angela Schmorrow, MSW, for her help in preparing this article for publication, and the reviewers to help us clarify our descriptions.

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The research was supported by the Arkansas Universal Assessment Project, Contract No. 4600031762 from the State of Arkansas to the University of Michigan. Nevertheless, the opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not represent the official position of the State of Arkansas.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: The data used in this study were prepared by PSP. All authors were involved in evaluating the statistical analysis, writing, and reviewing the final manuscript.

References

- 1. Fetter RB, Shin Y, Freeman JL, Averill RF, Thompson JD. Case mix definition by diagnosis-related groups. Med Care. 1980;18:1–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fries BE, Schneider DP, Foley WJ, Gavazzi M, Burke R, Cornelius E. Refining a case-mix measure for nursing homes: resource utilization groups (RUG-III). Med Care. 1994;32:668–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Iowa Foundation for Medical Care. Staff Time and Resource Intensity Verification Project Phase II. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hawes CH, Morris JN, Phillips CD, Fries BE, Murphy K, Mor V. Development of the nursing home Resident Assessment Instrument in the USA. Age Ageing. 1997;26:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. MDS 3.0 for nursing homes and swing bed providers. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/NHQIMDS30.html. Up-dated 2015. Accessed February 25, 2018.

- 6. Björkgren MA, Fries BE, Shugarman LR. A RUG-III case-mix system for home care. Can J Aging. 2000;19:106–125. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stineman MG, Escarce JJ, Goin JE, Hamilton BB, Granger CV, Williams SV. A case-mix classification system for medical rehabilitation. Med Care. 1994;32:366–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. LM Policy Research. Home Health Study and Report. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HomeHealthPPS/Downloads/HHPPS_HHAcasemixgrowthFinalReport.pdf. Up-dated 2011. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 9. Joint Commission on Administrative Rules, State of Illinois Department of Human Services. Service cost maximums. ftp://www.ilga.gov/jcar/admincode/089/08900679sections.html. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 10. Morgan JN, Sonquist JA. Problems in the analysis of survey data, and a proposal. J Am Stat Assoc. 1963;58:415–434. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hirdes JP, Martin L, Curtin-Telegdi N, Fries BE, et al. interRAI Intellectual Disability (ID) Assessment Form and User’s Manual. Version 9.2. Washington, DC: interRAI; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Office for People with Developmental Disabilities, New York State. The coordinated assessment system (CAS): validating the CAS in New York State. https://opwdd.ny.gov/people_first_waiver/coordinated_assessment_system/validity_study. Up-dated 2017. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 13. www.interRAI.org. Accessed February 15, 2017.

- 14. Morris JN, Berg K, Fries BE, Steel K, Howard EP. Scaling functional status within the interRAI suite of assessment instruments. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morris JN, Fries BE, Morris SA. Scaling ADLs within the MDS. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:M546–M553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, et al. MDS cognitive performance scale©. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M174–M182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Burrows AB, Morris JN, Simon SE, Hirdes JP, Phillips C. Development of a minimum data set-based depression rating scale for use in nursing homes. Age Ageing. 2000;29:165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Perlman CM, Hirdes JP. The aggressive behavior scale: a new scale to measure aggression based on the minimum data set. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2298–2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Martin L, Hirdes JP, Fries BE, Smith TF. Development and psychometric properties of an assessment for persons with intellectual disability, the interRAI ID. J Policy Prac Intell Disabil. 2007;4:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thompson JR, Bryant BR, Campbell EM, et al. Supports Intensity Scale (SIS). Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fortune J, Agosta J, Auerback K, et al. Developing reimbursement levels using the supports intensity scale (SIS) in Louisiana. Humans Services Research Institute. http://www.nasuad.org/sites/nasuad/files/hcbs/files/158/7869/SISLA.pdf. Up-dated 2009.

- 22. Kim S, Larson SA, Lakin KC. Behavioural outcomes of deinstitutionalisation for people with intellectual disability: a review of US studies conducted between 1980 and 1999. J Intell Develop Disabil. 2001;26:35–50. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lemay RA. Deinstitutionalization of people with developmental disabilities: a review of the literature. Can J Commun Mental Health. 2009;28:181–194. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mansell J. Deinstitutionalisation and community living: progress, problems and priorities. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2006;31:65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Government of Ontario. Developmental Services Ontario—the application form. http://www.dsontario.ca/the-application-form. Up-dated 2018. Accessed February 15, 2018.