Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the lipid‐lowering efficacy and safety of evolocumab combined with background atorvastatin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and hyperlipidaemia or mixed dyslipidaemia.

Materials and methods

BERSON was a double‐blind, 12‐week, phase 3 study (NCT02662569) conducted in 10 countries. Patients ≥18 to ≤80 years with type T2DM received atorvastatin 20 mg/d and were randomised 2:2:1:1 to evolocumab 140 mg every 2 weeks (Q2W) or 420 mg monthly (QM) or placebo Q2W or QM. Co‐primary endpoints were the percentage change in low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) from baseline to week 12 and from baseline to the mean of weeks 10 and 12. Additional endpoints included atherogenic lipids, glycaemic measures, and adverse events (AEs).

Results

Overall, 981 patients were randomised and received ≥1 dose of study drug. Evolocumab significantly reduced LDL‐C versus placebo at week 12 (Q2W, −71.8%; QM, −74.9%) and at the mean of weeks 10 and 12 (Q2W, −70.3%; QM, −70.0%; adjusted P < 0.0001 for all) when administered with atorvastatin. Non‐high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, apolipoprotein B100, total cholesterol, lipoprotein (a), triglycerides, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, and very low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol improved significantly with evolocumab versus placebo. The overall incidence of AEs was similar between evolocumab and placebo‐treated patients, and there were no clinically meaningful differences in changes over time in glycaemic variables (fasting serum glucose and HbA1c) between the two groups.

Conclusions

In patients with T2DM and hyperlipidaemia or mixed dyslipidaemia on statin, evolocumab significantly reduced LDL‐C and other atherogenic lipids, was well tolerated, and had no notable impact on glycaemic measures.

Keywords: dyslipidaemia, evolocumab, hyperlipidaemia, phase 3, type 2 diabetes

1. INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is a major risk factor for myocardial infarction, stroke, and other cardiovascular disease (CVD), and has been associated with increased risk for cardiovascular death compared with adults without diabetes.1 China has the highest prevalence of diabetes of all countries worldwide, with over 114 million estimated cases in 2017.2 In China, the risk of developing CVD among patients with diabetes is consistent with that in Western populations.3

Elevated low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) has been associated with cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).4, 5 Statins are the first‐line therapy for LDL‐C reduction and primary and secondary prevention of atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) events in patients with and without T2DM.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 The Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' Collaborators meta‐analysis showed that every mmol/L reduction in LDL‐C is associated with a 21% reduction in the incidence of any major vascular event, and the effect is similar in patients with or without diabetes.13 However, an unmet medical need remains for patients who are unable to reach recommended LDL‐C levels with a statin alone, who are unable to take an effective dose, or who are statin intolerant.12, 14, 15, 16, 17 Thus, additional lipid‐lowering therapies for achieving recommended LDL‐C levels and reducing cardiovascular risk are needed for this high–CVD risk patient population.

In phase 2 and 3 clinical studies, evolocumab, a human monoclonal antibody to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9), consistently reduced LDL‐C levels in patients on background statin alone or in combination with lipid‐lowering therapy.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 In the Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research with PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects with Elevated Risk (FOURIER) trial (NCT01764633), evolocumab reduced the risk of major cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke, and coronary revascularization) in patients with or without diabetes.24 In the evolocumaB Efficacy for LDL‐C Reduction in subjectS with T2DM On background statiN (BERSON) study, we assessed the efficacy and safety of evolocumab combined with background atorvastatin in reducing LDL‐C and improving other lipid levels in a global population of patients with T2DM and hyperlipidaemia or mixed dyslipidaemia. Of note, unlike post hoc and pooled analyses of evolocumab in patients with T2DM, this study included patients with worse diabetes control at baseline (e.g. elevated HbA1c). Approximately 50% of the patients in BERSON were enrolled at centres in China; a prespecified analysis of the efficacy and safety of evolocumab in the China population is reported by Chen at al.25

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and participants

BERSON (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02662569) was a 12‐week, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 study conducted at 98 centres in 10 countries (Argentina, Brazil, Canada, China, Colombia, France, Republic of Korea, Russian Federation, Turkey, and the United States). This global study was designed to recruit one half of its patients from China. The design and rationale of the study have been described in detail previously.26 The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the efficacy versus placebo of 12 weeks of subcutaneous evolocumab administered every 2 weeks (Q2W) or monthly (QM) combined with oral atorvastatin 20 mg once daily (QD) on the percentage change from baseline in LDL‐C level.

Eligible patients were ≥18 to ≤80 years of age with T2DM, were receiving stable pharmacological therapy for diabetes for ≥6 months, and had HbA1c ≤10% and fasting triglycerides ≤4.5 mmol/L (≤400 mg/dL). Patients on statin therapy at screening were required to have an LDL‐C of ≥2.6 mmol/L (≥100 mg/dL); those not on statin therapy at screening were required to have an LDL‐C of ≥3.4 mmol/L (≥130 mg/dL). Lipid‐lowering therapy status had to be unchanged for ≥4 weeks before LDL‐C screening. Key exclusion criteria were medical contraindications to receiving 20 mg atorvastatin; New York Heart Association (NYHA) III or IV heart failure; myocardial infarction, unstable angina, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass graft, or stroke within 6 months before randomization; eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2 at screening. Full exclusion criteria are provided in Supporting Information Table S1.

2.2. Ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines on good clinical practice and with ethical standards for human experimentation established by the Declaration of Helsinki. An independent review board or independent ethics committee at each study site reviewed the study and approved the protocol and the subsequent amendments to the study protocol. An external, independent data monitoring committee (DMC) periodically reviewed study data, and analyses for the DMC were provided by an independent biostatistical group. All patients provided written, informed consent before participation.

2.3. Randomization and study procedures

After undergoing screening procedures, including laboratory assessments and a single screening placebo injection with auto‐injector (AI/Pen), eligible patients underwent a lipid stabilization period of up to 8 weeks with oral atorvastatin 20 mg QD; all other lipid‐lowering therapies were discontinued before initiating atorvastatin 20 mg QD. Patients were then randomised 2:2:1:1 to receive subcutaneous evolocumab 140 mg Q2W, evolocumab 420 mg QM, placebo Q2W, or placebo QM for 12 weeks. These doses of evolocumab are the approved and commercially available doses for the treatment of adults with primary hypercholesterolaemia or mixed dyslipidaemia and adults with established ASCVD.27, 28 Given that approximately half of the patients were recruited at centres in China, atorvastatin 20 mg QD was selected for the study based on Chinese dyslipidaemia guidelines and the anticipated LDL‐C response in Chinese patients.29, 30 Justification for the study length was described previously.26 The last dose of evolocumab or placebo was administered at week 8 for QM patients and week 10 for Q2W patients. The final study visit was at week 12 for QM patients and by telephone follow‐up at week 14 for Q2W patients.

Randomization was based on a computer‐generated randomization sequence with an interactive voice response system and was stratified by entry statin therapy (no statin use vs. non‐intensive statin use) and the study centre's geographic region. Treatment assignment was blinded to the sponsor study team, investigators, site staff, and patients throughout the study.

2.4. Study assessments

The assessment of fasting levels of lipids [total cholesterol, LDL‐C, triglycerides, very low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL‐C), non‐high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (non‐HDL‐C), and high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C)] were collected at screening, at the end of lipid stabilization, and at study visits on day 1 and at weeks 2, 8, 10, and 12. Apolipoprotein B100 (ApoB100) was measured on day 1 and at weeks 10 and 12. Blood chemistry, including fasting serum glucose (FSG; GLUC3, Roche, Basel, Switzerland), was assessed at screening, at the end of lipid stabilization, and at study visits on day 1 and at weeks 8 and 12. HbA1c was assessed at screening and at week 12 (VARIANT II; Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Lipid variables were assessed by a central laboratory; results of the lipid panel and lipoproteins were not reported to the investigator or sponsor study team postscreening and remained blinded until unblinding of the clinical database. Investigators and site staff could not perform lipid panels until 12 weeks after a patient's last dose of evolocumab or end of study, whichever occurred later. Serum lipids and ApoB100 were measured by Medpace (Cincinnati, Ohio; Leuven, Belgium).31 For all analyses related to LDL‐C, unless specified otherwise, a reflexive approach was used where the calculated LDL‐C based on the Friedewald equation was used unless the calculated LDL‐C was <1.0 mmol/L (40 mg/dL) or triglycerides were >4.5 mmol/L (400 mg/dL), in which case preparative ultracentrifugation LDL‐C was performed. FSG and HbA1c were assessed as part of chemistry by Q2 Solutions (Valencia, California; Livingston, UK).

Adverse events (AEs) were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 20.1. Blood samples for the assessment of antievolocumab antibodies were assayed on day 1 and at week 12.32

2.5. Statistics

The co‐primary endpoints were the percentage change from baseline in LDL‐C at week 12 and the percentage change from baseline in LDL‐C at the mean of weeks 10 and 12. Secondary endpoints included but were not limited to the change from baseline in LDL‐C and the percentage change from baseline in non‐HDL‐C, ApoB100, total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL‐C, VLDL‐C, and achievement of target LDL‐C < 1.8 mmol/L (70 mg/dL). Safety endpoints included patient incidence of treatment‐emergent AEs, laboratory values, and the incidence of binding and neutralizing antievolocumab antibodies.

A sample size of 900 (300 per evolocumab regimen and 150 per placebo regimen) was expected to provide ≥98% power to detect a ≥ 35% reduction in LDL‐C in both evolocumab groups compared with placebo, assuming a common standard deviation (SD) of 20%, that 2% of patients would not be treated, and after accounting for an estimated 15% study drug discontinuation rate.

Efficacy and safety were assessed for all randomised patients who received ≥1 dose of study drug [full analysis set (FAS)]; an additional pre‐specified subgroup analysis was performed for patients who were randomised at study centres in China. The efficacy of evolocumab was compared with placebo at the co‐primary endpoints (percentage change from baseline in LDL‐C at week 12 and the mean of weeks 10 and 12), and the efficacy of continuous co‐secondary endpoints were compared using repeated‐measures linear mixed‐effects models, which included terms for treatment group, stratification factors [statin therapy at study entry (none vs. non‐intensive vs. intensive), the site's geographic region (China, Republic of Korea, or other country)], scheduled visit, and the interaction of treatment with the scheduled visit. Analyses for the co‐primary and co‐secondary endpoints were adjusted for multiplicity to preserve the family‐wise error rate at 0.05.33 Baseline covariates included stratification factors, age, sex, race, baseline LDL‐C, family history of premature coronary heart disease, baseline PCSK9, body mass index, hypertension, current smoker, ≥2 baseline CHD risk factors, and triglycerides. The co‐secondary endpoint of LDL‐C target achievement was assessed using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test adjusted by the stratification factors. Safety assessments were summarized descriptively.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patients

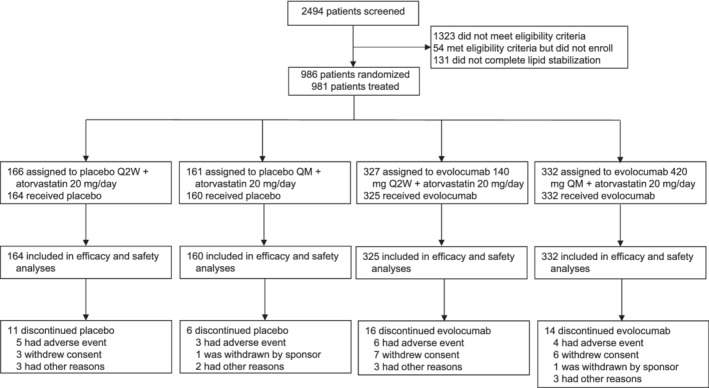

The study was conducted from 14 April 2016 through 6 December 2017. Of the 2494 patients screened, 986 were randomised (Figure 1), 981 received at least one dose of study drug (the FAS), and 934 (94.7%) completed treatment. Atorvastatin 20 mg/d was initiated in 984 patients, and 943 (95.6%) completed treatment.

Figure 1.

Patient enrolment and disposition

Demographics and baseline clinical characteristics were generally balanced between the evolocumab and placebo groups (Table 1). Most patients (57.3%) were female, and the mean age was 61.3 years. As anticipated, approximately half (49.9%) of patients were Asian, with 45.9% of patients enrolled at centres in China. Baseline lipid variables were generally consistent between treatment groups (Table 1). The mean (SD) serum concentration of LDL‐C at baseline was 2.4 (0.9) mmol/L. Median HbA1c, FSG, and insulin use at baseline were imbalanced between the evolocumab and placebo groups [median (Q1, Q3) HbA1c, 7.1% (6.4, 8.2) vs. 6.9% (6.2, 7.9); median FSG, 7.4 (6.1, 9.2) vs. 7.0 (5.9, 8.6) mmol/L; insulin use, 32.1% vs. 28.1%).

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics and lipid values

| Characteristics | Placebo | Evolocumab |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 324) | (n = 657) | |

| Baseline demographics | ||

| Median age (range), y | 62 (35‐80) | 62 (33‐80) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 195 (60.2) | 367 (55.9) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| Asian | 160 (49.4) | 330 (50.2) |

| White | 139 (42.9) | 278 (42.3) |

| Black | 13 (4.0) | 29 (4.4) |

| Other | 12 (3.4) | 20 (3.0) |

| Baseline clinical characteristics | ||

| Mean systolic blood pressure (SD), mmHg | 130.4 (13.9) | 129.8 (13.6) |

| Mean body mass index (SD), kg/m2 | 28.3 (5.6) | 28.5 (5.3) |

| Mean waist circumference (SD), cm | 96.6 (13.3) | 97.3 (12.2) |

| Statin therapy, n (%) | 186 (57.4) | 374 (56.9) |

| Intensive statin usea | 14 (4.3) | 36 (5.5) |

| Non‐intensive statin useb | 172 (53.1) | 338 (51.4) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 239 (73.8) | 478 (72.8) |

| Cerebrovascular or peripheral arterial disease, n (%) | 91 (28.1) | 180 (27.4) |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 97 (29.9) | 191 (29.1) |

| Baseline diabetes‐related medication use, n (%) | 323 (99.7) | 654 (99.5) |

| Alpha‐glucosidase inhibitors | 36 (11.1) | 110 (16.7) |

| Biguanides | 223 (68.8) | 454 (69.1) |

| Dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors | 32 (9.9) | 56 (8.5) |

| Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists | 5 (1.5) | 7 (1.1) |

| Insulin | 91 (28.1) | 211 (32.1) |

| Meglitinides | 12 (3.7) | 31 (4.7) |

| Sodium‐glucose co‐transporter‐2 inhibitors | 10 (3.1) | 19 (2.9) |

| Sulfonylureas | 120 (37.0) | 223 (33.9) |

| Thiazolidinediones | 14 (4.3) | 19 (2.9) |

| Other | 3 (0.9) | 11 (1.7) |

| Mean baseline lipid values (SD) | ||

| LDL‐C, mmol/L | 2.4 (0.8) | 2.4 (0.9) |

| Non − HDL‐C, mmol/L | 3.1 (1.0) | 3.1 (1.0) |

| ApoB100, g/L | 0.83 (0.23) | 0.85 (0.22) |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.3 (1.0) | 4.4 (1.0) |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.6 (1.4) | 1.6 (0.7) |

| HDL‐C, mmol/L | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.3) |

| VLDL‐C, mmol/L | 0.72 (0.40) | 0.73 (0.33) |

| Lp(a), nmol/L | 69.4 (93.6) | 69.4 (94.3) |

| Median baseline glucose metabolism measures (Q1, Q3) | ||

| HbA1c, % | 6.9 (6.2, 7.9) | 7.1 (6.4, 8.2) |

| Fasting serum glucose, mmol/L | 7.0 (5.9, 8.6) | 7.4 (6.1, 9.2) |

Abbreviations: ACC/AHA, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; ApoB100, apolipoprotein B100; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lp(a), lipoprotein (a); SD, standard deviation; VLDL‐C, very low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Patient had at least one of the following recorded for the last 4 weeks before screening: atorvastatin ≥40 mg QD; rosuvastatin ≥20 mg QD; simvastatin ≥80 mg QD [simvastatin 80 mg QD is not approved in some countries (e.g. United States)]; and any statin (atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pitavastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin, and simvastatin) QD plus ezetimibe.

Patient had been taking any dose of a statin at least weekly for the last 4 weeks before screening and was not included in the intensive statin usage.

3.2. Efficacy

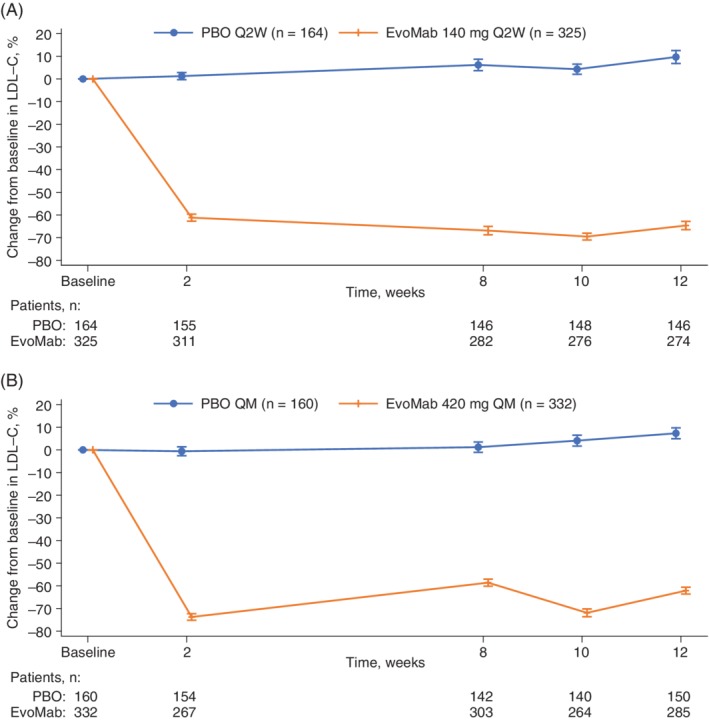

Compared with placebo, evolocumab treatment reduced LDL‐C by a least‐squares mean of 71.8% (95% CI, −77.6 to −65.9; P < 0.0001) with Q2W dosing and 64.9% (−70.0 to 59.9; adjusted P < 0.0001) with QM dosing at week 12, and by 70.3% (−75.4 to −65.2; adjusted P < 0.0001) with Q2W dosing and 70.0% (−74.7 to −63.4; adjusted P < 0.0001) with QM dosing at the mean of weeks 10 and 12 (Table 2). The treatment effect in LDL‐C by scheduled visits and treatment groups for Q2W and QM regimens is shown in Figure 2. LDL‐C concentrations were reduced to below 70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L) in 88% and 90% of patients in the evolocumab Q2W and QM groups, respectively, at week 12, and in 90% and 91% of patients in the evolocumab Q2W and QM groups, respectively, at the mean of weeks 10 and 12 (Table 2). Subgroup analyses of the co‐primary endpoints showed treatment effects that were consistent with those observed in the global study population.

Table 2.

Efficacy results at week 12 and at the mean of weeks 10 and 12

| Week 12 | Mean of weeks 10 and 12 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | PBO Q2W(n = 164) | EvoMab 140 mg Q2W(n = 325) | PBO QM(n = 160) | EvoMab 420 mg QM(n = 332) | PBO Q2W(n = 164) | EvoMab 140 mg Q2W(n = 325) | PBO QM(n = 160) | EvoMab 420 mg QM(n = 332) |

| LDL‐C | ||||||||

| n | 148 | 288 | 150 | 295 | 157 | 312 | 155 | 320 |

| Least squares mean change from baseline (SE), % | 7.1 (3.7) | −64.7 (3.2) | 2.6 (3.4) | −62.3 (3.0) | 4.9 (3.5) | −65.4 (3.1) | 1.0 (3.3) | −69.1 (3.0) |

| Mean change from baseline, mmol/L | −0.01 | −1.66 | −0.19 | −1.71 | −0.05 | −1.67 | −0.23 | −1.86 |

| 95% CI | −0.22, 0.20 | −1.84, −1.47 | −0.40, 0.02 | −1.90, −1.53 | −0.26, 0.15 | −1.86, −1.49 | 0.43, −0.02 | −2.05, −1.68 |

| Mean treatment differencea (SE), % | — | −71.8 (3.0) | — | −64.9 (2.6) | — | −70.3 (2.6) | — | −70.0 (2.4) |

| 95% CI | −77.6, −65.9 | −70.0, −59.9 | −75.4, −65.2 | −74.7, −63.4 | ||||

| Adjusted P valueb | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Achievement of 1.8 mmol/L, n (%) | 31 (20.9) | 254 (88.2) | 32 (21.3) | 266 (90.2) | 34 (21.7) | 281 (90.1) | 30 (19.4) | 292 (91.3) |

| Least squares mean change from baseline for secondary endpoints (SE), % | ||||||||

| Non‐HDL‐C | 5.9 (3.2) | −55.8 (2.8) | 1.3 (3.0) | −52.9 (2.7) | 4.3 (3.1) | −56.6 (2.7) | 0.3 (3.0) | −59.1 (2.6) |

| ApoB100 | 3.2 (3.4) | −53.9 (3.1) | −0.3 (3.0) | −49.7 (2.8) | 2.0 (3.3) | −55.0 (3.1) | −1.5 (3.0) | −56.4 (2.7) |

| Total cholesterol | 4.4 (2.4) | −37.8 (2.1) | 0.7 (2.2) | −35.2 (2.0) | 2.9 (2.3) | −38.6 (2.0) | −0.3 (2.2) | −39.7 (2.0) |

| Lp(a) | 26.5 (21.8) | −35.9 (16.5) | 7.5 (10.4) | −37.9 (9.0) | 16.9 (17.5) | −38.6 (13.7) | 8.5 (9.5) | −52.3 (8.5) |

| Triglycerides | 10.5 (5.4) | −5.9 (4.8) | 8.1 (4.6) | −4.2 (4.1) | 11.5 (5.3) | −6.5 (4.7) | 8.5 (4.5) | −7.2 (4.0) |

| HDL‐C | 2.6 (2.3) | 8.5 (2.0) | 6.0 (2.2) | 14.2 (2.0) | 1.3 (2.2) | 7.6 (2.0) | 5.9 (2.1) | 13.8 (1.9) |

| VLDL‐C | 8.6 (4.8) | −14.2 (4.2) | 7.5 (4.6) | −9.5 (4.1) | 9.6 (4.7) | −17.6 (4.2) | 7.9 (4.4) | −16.1 (4.0) |

Abbreviations: ApoB100, apolipoprotein B100; CI, confidence interval; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lp(a), lipoprotein (a); SE, standard error; VLDL‐C, very low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Treatment difference is from the repeated measures linear effects model, which included treatment group, stratification factors, scheduled visit, and the interaction of treatment with scheduled visit as covariates for all endpoints except LDL‐C achievement.

Adjusted P value is based on a combination of sequential testing, the Hochberg procedure, which is a fallback procedure to control the overall significance level for all primary and secondary endpoints. Each individual adjusted P value is compared with 0.05 to determine statistical significance.

Figure 2.

Mean percentage change in LDL‐C from baseline to scheduled visits in LDL‐C for (A) Q2W dosing and (B) QM dosing. Vertical lines represent the standard error around the mean. No imputation was used for missing values. When the calculated LDL‐C was <1.0 mmol/L or triglycerides were >4.5 mmol/L, calculated LDL‐C was replaced with ultracentrifugation LDL‐C from the same blood sample, if available

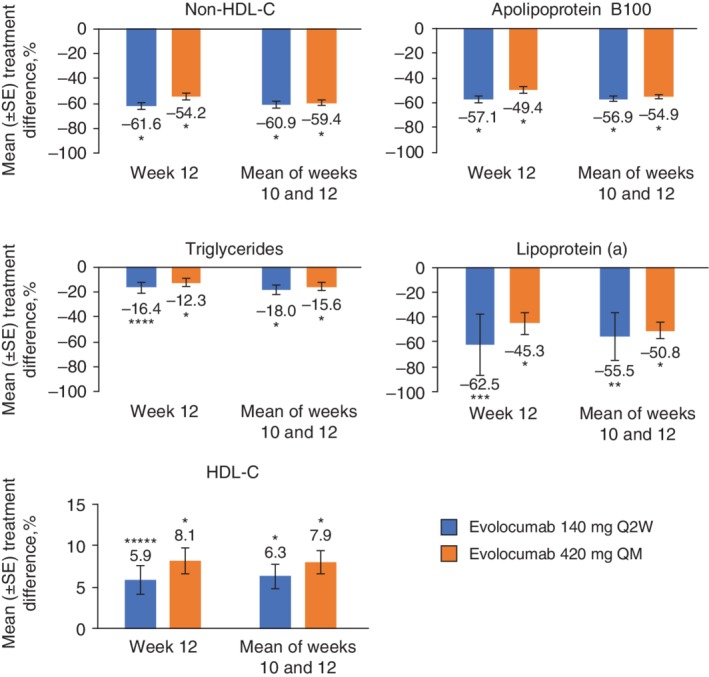

Changes from baseline in secondary lipid variables are summarized in Table 2. Treatment with evolocumab, compared with placebo, similarly resulted in statistically significant improvements in non‐HDL‐C from baseline to week 12 (Q2W, −61.6%, adjusted P < 0.0001; QM, −54.2%, adjusted P < 0.0001) and to the mean of weeks 10 and 12 (Q2W, −60.9%, adjusted P < 0.0001; QM, −59.4%, adjusted P < 0.0001; Figure 3). Treatment with evolocumab also resulted in significant improvements in ApoB100, triglycerides, Lp(a), and HDL‐C.

Figure 3.

Mean percentage treatment difference for evolocumab versus placebo in non‐HDL‐C, apolipoprotein B100, triglycerides, lipoprotein (a), and HDL‐C. Treatment difference is from the repeated measures linear effects model, which included treatment group, stratification factors, scheduled visit, and the interaction of treatment with scheduled visit as covariates for all endpoints except LDL‐C achievement. Error bars show standard error. HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol. *P < 0.0001 versus placebo; **P = 0.004 versus placebo; ***P = 0.0001 versus placebo; ****P = 0.0002 versus placebo; *****P = 0.0003 versus placebo

3.3. Safety and immunogenicity

The overall incidence of AEs was similar between patients who received evolocumab and placebo, with 288 (43.8%) and 138 (42.6%) patients, respectively, having an AE (Table 3). Most were grade 1 (placebo, 13.6%; evolocumab, 14.0%) or 2 (placebo, 23.5%; evolocumab, 21.9%). The most common AEs in the evolocumab group were diabetes mellitus (describing exacerbation or worsening of pre‐existing diabetes), upper respiratory tract infection, nasopharyngitis, and hypertension.

Table 3.

Incidence of treatment‐emergent adverse events

| Characteristics | Placebo(n = 324) | Evolocumab(n = 657) |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with AE, n (%) | 138 (42.6) | 288 (43.8) |

| Patients with serious AE, n (%) | 11 (3.4) | 32 (4.9) |

| Patients with AEs leading to treatment discontinuation, n (%) | 7 (2.2) | 10 (1.5) |

| Fatal AEs, n (%) | 0 | 0 |

| Common AEsa, n (%) | ||

| Diabetes mellitusb | 8 (2.4) | 38 (5.8) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 11 (3.4) | 23 (3.5) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 12 (3.7) | 20 (3.0) |

| Hypertension | 10 (3.1) | 13 (2.0) |

| Dizziness | 2 (0.6) | 10 (1.5) |

| Urinary tract infection | 5 (1.5) | 9 (1.4) |

| Back pain | 4 (1.2) | 8 (1.2) |

| Headache | 3 (0.9) | 8 (1.2) |

| Blood uric acid increased | 3 (0.9) | 8 (1.2) |

| Cough | 6 (1.9) | 7 (1.1) |

| Toothache | 3 (0.9) | 7 (1.1) |

| Peripheral oedema | 0 | 7 (1.1) |

| Median change from baseline in glycaemic measures (Q1, Q3) | ||

| HbA1c, % | 0.1 (−0.2, 0.5) | 0.1 (−0.3, 0.6) |

| Fasting serum glucose, mmol/L | 0.1 (−0.6, 0.9) | 0.1 (−0.7, 1.2) |

| Abnormal laboratory tests, n (%) | ||

| Creatine kinase >5× ULN | 1 (0.3)c | 1 (0.2)d |

| Alanine aminotransferase >3 × ULN | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase >3 × ULN | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Occurring in at least 1% of patients in evolocumab treatment group.

Includes preferred terms of diabetes mellitus (placebo, 1.9%; evolocumab, 4.6%) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (placebo, 0.6%; evolocumab, 1.2%).

Patient was assigned to QM dosing, reported at week 8 visit, remained asymptomatic, and returned to baseline at week 12.

Patient was assigned to QM dosing, reported at week 8 and 12 visits, remained asymptomatic.

A majority of diabetes mellitus AEs were mild in severity (grade 1 or 2) and were managed with medication and/or diet and exercise counselling. Study drug treatment was not withdrawn or discontinued for any patient with an AE of diabetes mellitus. No meaningful changes from baseline in glycaemic variables occurred in either treatment group during the study, as median (Q1, Q3) changes from baseline to week 12 in HbA1c were 0.1% (−0.3, 0.6) in the evolocumab group and 0.1% (−0.2, 0.5) in the placebo group, and median changes from baseline to week 12 in FSG were 0.1 mmol/L (−0.7, 1.2) in the evolocumab group and 0.1 mmol/L (−0.6, 0.9) in the placebo group (Table 3).

Serious AEs (SAEs) occurred in 32 (4.9%) patients in the evolocumab group and 11 (3.4%) patients in the placebo group. There were no single SAEs reported in ≥1% of patients in either the evolocumab or placebo groups. SAEs were considered not related to study drug by the investigators, except for gastric ulcer (one patient, evolocumab) and lacunar stroke (one patient, evolocumab). No deaths occurred during the study. One patient in the evolocumab QM group tested positive for antievolocumab binding antibodies at baseline; no patients tested positive for binding or neutralizing antibodies during the study.

4. DISCUSSION

BERSON is the largest (n = 986) dedicated T2DM study with a PCSK9 inhibitor to date. Treatment with evolocumab 140 mg Q2W and 420 mg QM, compared with placebo, with moderate intensity background atorvastatin, led to significant reductions in LDL‐C concentrations over 12 weeks. For diabetic patients with ASCVD or without ASCVD and at least one additional risk factor, The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology and American Diabetes Association guidelines recommend the addition of ezetimibe or a PSCK9 inhibitor when recommended LDL‐C levels (<1.8 mmol/L) are not achieved with maximally tolerated statin therapy.11 In BERSON, evolocumab treatment allowed the vast majority of patients to achieve LDL‐C levels <1.8 mmol/L (Q2W, 88%‐90%; QM, 90%‐91%). A mean absolute reduction in LDL‐C of 1.62 and 1.64 mmol/L, Q2W and QM, respectively, was observed in the evolocumab group versus the placebo group. In FOURIER, a mean absolute reduction of 1.45 mmol/L at 48 weeks was associated with a 16% (95% CI, 4 to 26) risk reduction in the composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke, and the magnitude of the risk reduction increased beyond the first year.34 Furthermore, robust improvements in non‐HDL‐C and ApoB100 were observed with evolocumab compared with placebo on background atorvastatin, both targets for therapy in patients with T2DM and in whom the addition of a non‐statin therapy is recommended when desired levels are not achieved with maximally tolerated statin therapy.11

The reductions in LDL‐C and non‐HDL‐C observed in BERSON are consistent with the results of the BANTING study (also a dedicated type 2 diabetes trial), as well as previous prespecified and post hoc (DESCARTES) analyses of other phase 3 evolocumab studies. In the 12‐week, randomised, double‐blind phase 3 BANTING study, treatment with evolocumab decreased LDL‐C by 65% and non‐HDL‐C by 56% versus placebo in patients with T2DM and hypercholesterolaemia or mixed dyslipidaemia on background statin therapy.35 In a meta‐analysis of three 12‐week phase 3 studies of patients with hypercholesteraemia and T2DM, evolocumab reduced LDL‐C by 60% and non‐HDL‐C by 55% compared with placebo.36 Similar results were observed in a post hoc analysis by baseline glycaemic status from the 52‐week DESCARTES study in patients with hypercholesterolemia.18 In the prespecified analysis of patients with (n = 11 031) and without (n = 16 533) diabetes from the long‐term FOURIER cardiovascular outcomes study, significant reductions in LDL‐C and other atherogenic lipids have also been observed with evolocumab combined with statin therapy (almost 70% on high‐intensity and 30% on moderate intensity).24 Of note, the LDL‐C lowering effect significantly reduced cardiovascular risk with similar efficacy in patients with and without diabetes; however, because of the higher baseline risk, the absolute risk reduction was greater in patients with diabetes.24 Likewise, significant LDL‐C and non‐HDL‐C reductions were seen after 24 weeks of treatment with the PCSK9 inhibitor alirocumab in patients with T2DM.37, 38

In this study, evolocumab combined with moderate intensity atorvastatin was well tolerated and the overall incidence of AEs was consistent with previous reports.35, 36 The imbalance in AEs of diabetes in the evolocumab group was not surprising given that, at baseline, insulin use was higher and glycaemic control was worse in the evolocumab group than in the placebo group, as evidenced by the greater baseline median HbA1c and FPG levels. In the BANTING study, where FSG, HbA1c, and insulin use were balanced between groups, no difference in diabetes AEs was observed (placebo, 3.5%; evolocumab, 2.9%).35 Because there were no established criteria for reporting diabetes as an AE in BERSON, a more meaningful assessment of the effect of evolocumab on glucose homeostasis is the review of HbA1c and FSG. Notably, no changes from baseline in HbA1c or FSG were observed during the study in either treatment group. These results are similar to those of previous double‐blind phase 3 studies and open‐label extension studies in which treatment with evolocumab had no notable effect on measures of glycaemic control in patients with or without diabetes.24, 39, 40, 41 Likewise, an open‐label study and two pooled analyses of ODYSSEY phase 3 studies showed that treatment with alirocumab had no notable effect on measures of glycaemic control (HbA1c or FPG) in patients with or without diabetes.37, 42, 43 In a systematic review and meta‐analysis including 18 randomised studies with evolocumab or alirocumab in patients without diabetes (n = 26, 123), there was no difference in new‐onset diabetes, fasting glucose, or HbA1c between patients who received a PCSK9 inhibitor (alirocumab or evolocumab) versus control.44

The limitations of this study include the 12‐week duration for the assessment of safety, the sustained LDL‐C lowering effect, and the relatively small number of patients (n = 981) enrolled. However, consistent efficacy and safety data have been shown in patients with T2DM in post hoc and prespecified analyses of evolocumab with a larger sample size and/or longer follow‐up.18, 24, 36 An additional limitation is the use of a non‐intensive statin (atorvastatin 20 mg/d), which represents standard practice in China, is more conservative than that used in other regions, and limits the comparison of these results with other global studies.

BERSON is the largest dedicated evolocumab clinical study in patients with T2DM and the results from this randomised, double‐blind study supplement the data already available from a prespecified subgroup analysis of the large cardiovascular outcomes FOURIER study, as well as other post hoc and prespecified analyses of patients with diabetes from phase 3 studies.

In conclusion, the results of BERSON showed that in patients with T2DM with hyperlipidaemia or mixed dyslipidaemia, evolocumab on background atorvastatin significantly reduced LDL‐C, allowed the vast majority of patients to achieve LDL‐C levels <1.8 mmol/L, and significantly improved other atherogenic lipid variables. Evolocumab had no notable effect on measures of glycaemic control and was safe and well tolerated.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

A.J.L. has served as an advisory board and steering committee member for and has received research grants and speaker fees from Amgen Inc. F.G.E. has served as a speaker for and has received grants for research from Amgen Inc., Sanofi, Boehringer, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and AstraZeneca. M.L.M., N.W., and A.W.H. are employees of and own stock in Amgen Inc. Y.C., J.L., A.B., and J.G. have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author contributions

A.J.L. acquired and interpreted the data. F.G.E. acquired the data. Y.C. acquired the data. J.L. acquired the data. A.B. acquired the data. M.L.M. acquired and interpreted the data. N.W. acquired and interpreted the data. A.W.H. acquired and interpreted the data. J.G. acquired the data. All authors are responsible for the work described in this paper. All authors either drafted the manuscript or critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work insuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Supporting information

Table S1. Full exclusion criteria

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Xiaoyan Ye, PhD (Paraexel), for programming support. Medical writing end editorial support was provided by Ben Scott, PhD (Scott Medical Communications, LLC; funded by Amgen Inc.), and Annalise M. Nawrocki, PhD, of Amgen Inc.

Lorenzatti AJ, Eliaschewitz FG, Chen Y, et al. Randomised study of evolocumab in patients with type 2 diabetes and dyslipidaemia on background statin: Primary results of the BERSON clinical trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:1455–1463. 10.1111/dom.13680

Peer Review The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/dom.13680.

Funding information This study was funded by Amgen Inc.

Data Availability: Qualified researchers may request data from Amgen clinical studies. Complete details are available at the following: http://www.amgen.com/datasharing.

Data availability

Qualified researchers may request data from Amgen clinical studies. Complete details are available at the following: http://www.amgen.com/datasharing.

REFERENCES

- 1. Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart disease and stroke Statistics‐2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e67‐e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. International Diabetes Federation . IDF Diabetes Atlas. 8th ed.; Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Foundation; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bragg F, Li L, Yang L, et al. Risks and population burden of cardiovascular diseases associated with diabetes in China: a prospective study of 0.5 million adults. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration , Di Angelantonio E, Sarwar N, et al. Major lipids, apolipoproteins, and risk of vascular disease. JAMA. 2009;302:1993‐2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stamler J, Vaccaro O, Neaton JD, Wentworth D. Diabetes, other risk factors, and 12‐yr cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:434‐444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. American Diabetes A . 9. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: standards of medical care in diabetes‐2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(suppl 1):S86‐S104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fox CS, Golden SH, Anderson C, et al. Update on prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus in light of recent evidence: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Circulation. 2015;132:691‐718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Colhoun HM, Betteridge DJ, Durrington PN, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with atorvastatin in type 2 diabetes in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS): multicentre randomised placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:685‐696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shepherd J, Barter P, Carmena R, et al. Effect of lowering LDL cholesterol substantially below currently recommended levels in patients with coronary heart disease and diabetes: the Treating to New Targets (TNT) study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1220‐1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. American Diabetes A . 8. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical Care in Diabetes‐2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(suppl 1):S73‐S85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm ‐ 2018 executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2018;24:91‐120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S1‐S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Collaborators CTT, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, et al. Efficacy of cholesterol‐lowering therapy in 18,686 people with diabetes in 14 randomised trials of statins: a meta‐analysis. Lancet. 2008;371:117‐125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. European Association for Cardiovascular P, Rehabilitation , Reiner Z, et al. ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: the task force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur Heart J. 2011;32(14):1769‐1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang H, Plutzky J, Skentzos S, et al. Discontinuation of statins in routine care settings: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:526‐534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mora S, Wenger NK, Demicco DA, et al. Determinants of residual risk in secondary prevention patients treated with high‐ versus low‐dose statin therapy: the Treating to New Targets (TNT) study. Circulation. 2012;125:1979‐1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Banach M, Rizzo M, Toth PP, et al. Statin intolerance ‐ an attempt at a unified definition. Position paper from an international lipid expert panel. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11:1‐23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Blom DJ, Hala T, Bolognese M, et al. A 52‐week placebo‐controlled trial of evolocumab in hyperlipidemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1809‐1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koren MJ, Giugliano RP, Raal FJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of longer‐term administration of evolocumab (AMG 145) in patients with hypercholesterolemia: 52‐week results from the open‐label study of long‐term evaluation against LDL‐C (OSLER) randomised trial. Circulation. 2014;129:234‐243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koren MJ, Lundqvist P, Bolognese M, et al. Anti‐PCSK9 monotherapy for hypercholesterolemia: the MENDEL‐2 randomised, controlled phase III clinical trial of evolocumab. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2531‐2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Raal FJ, Stein EA, Dufour R, et al. PCSK9 inhibition with evolocumab (AMG 145) in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia (RUTHERFORD‐2): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:331‐340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Robinson JG, Nedergaard BS, Rogers WJ, et al. Effect of evolocumab or ezetimibe added to moderate‐ or high‐intensity statin therapy on LDL‐C lowering in patients with hypercholesterolemia: the LAPLACE‐2 randomised clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1870‐1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stroes E, Colquhoun D, Sullivan D, et al. Anti‐PCSK9 antibody effectively lowers cholesterol in patients with statin intolerance: the GAUSS‐2 randomised, placebo‐controlled phase 3 clinical trial of evolocumab. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2541‐2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sabatine MS, Leiter LA, Wiviott SD, et al. Cardiovascular safety and efficacy of the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab in patients with and without diabetes and the effect of evolocumab on glycaemia and risk of new‐onset diabetes: a prespecified analysis of the FOURIER randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:941‐950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen Y, Yuan Z, Lu J, et al. Randomised study of evolocumab in patients with type 2 diabetes and dyslipidaemia on back ground statin: pre‐specified analysis of the China population from the BERSON clinicaltrial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 10.1111/dom.13700. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lorenzatti AJ, Eliaschewitz FG, Chen Y, et al. Rationale and design of a randomised study to assess the efficacy and safety of evolocumab in patients with diabetes and dyslipidemia: the BERSON clinical trial. Clin Cardiol. 2018;41:1117‐1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. REPATHA (evolocumab) . Full Prescribing Information. Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen Inc.; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28. European Medicines Agency . REPATHA European Public Assessment Report. Summary of Product Characteristics. London, United Kingdom: European Medicines Agency; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lipitor (atorvastatin) . Full Prescribing Information. Dublin: Pfizer Ireland; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Joint Committee for Guideline Revision . 2016 Chinese guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia in adults. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2018;15:1‐29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Myers GL, Cooper GR, Winn CL, Smith SJ. The centers for disease control‐National Heart, lung and blood institute lipid standardization program. An approach to accurate and precise lipid measurements. Clin Lab Med. 1989;9:105‐135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dias CS, Shaywitz AJ, Wasserman SM, et al. Effects of AMG 145 on low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol levels: results from 2 randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, ascending‐dose phase 1 studies in healthy volunteers and hypercholesterolemic subjects on statins. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1888‐1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75;800‐802. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713‐1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rosenson RS, Daviglus ML, Reaven P, et al. Efficacy and safety of evolocumab in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypercholesterolemia or mixed dyslipidemia. Diabetes. 2018;67(suppl 1):128‐OR. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sattar N, Preiss D, Robinson JG, et al. Lipid‐lowering efficacy of the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab (AMG 145) in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta‐analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4:403‐410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ray KK, Leiter LA, Muller‐Wieland D, et al. Alirocumab vs usual lipid‐lowering care as add‐on to statin therapy in individuals with type 2 diabetes and mixed dyslipidaemia: the ODYSSEY DM‐DYSLIPIDEMIA randomised trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:1479‐1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Taskinen MR, Del Prato S, Bujas‐Bobanovic M, et al. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus with or without mixed dyslipidaemia: analysis of the ODYSSEY LONG TERM trial. Atherosclerosis. 2018;276:124‐130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Blom DJ, Koren MJ, Roth E, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy, safety and glycaemic effects of evolocumab (AMG 145) in hypercholesterolaemic patients stratified by glycaemic status and metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19:98‐107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Koren MJ, Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, et al. Long‐term low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol‐lowering efficacy, persistence, and safety of Evolocumab in treatment of hypercholesterolemia: results up to 4 years from the open‐label OSLER‐1 extension study. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:598‐607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sattar N, Toth PP, Blom DJ, et al. Effect of the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor evolocumab on glycemia, body weight, and new‐onset diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120:1521‐1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Colhoun HM, Ginsberg HN, Robinson JG, et al. No effect of PCSK9 inhibitor alirocumab on the incidence of diabetes in a pooled analysis from 10 ODYSSEY phase 3 studies. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2981‐2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ganda OP, Plutzky J, Sanganalmath SK, et al. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab among individuals with diabetes mellitus and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the ODYSSEY phase 3 trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:2389‐2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cao YX, Liu HH, Dong QT, Li S, Li JJ. Effect of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) monoclonal antibodies on new‐onset diabetes mellitus and glucose metabolism: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:1391‐1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Full exclusion criteria

Data Availability Statement

Qualified researchers may request data from Amgen clinical studies. Complete details are available at the following: http://www.amgen.com/datasharing.