Abstract

Optimal complementary feeding practices, a critical component of infant and young child feeding, has been demonstrated to prevent micronutrient deficiencies, stunting, overweight, and obesity. In Kenya, while impressive gains have been made in exclusive breastfeeding, progress in complementary feeding has been slow, and the country has failed to meet targets. Recent 2014 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey reveal that only 22% of Kenyan children, 6–23 months, met criteria for a minimum acceptable diet. This case study describes key actions for complementary feeding put in place by the Kenya Ministry of Health as well as approaches for improving and monitoring complementary feeding within existing health platforms. Experience from USAID's Maternal and Child Survival Program and Ministry of Health on development of 23 complementary feeding recipes through application of a national guide for recipe development and Trials of Improved Practices is described. Challenges in how to prepare, modify, and cook foods, including meat, for young children 6–23 months of age was relayed by mothers. Addressing cultural beliefs around complementary feeding meant providing reassurance to mothers that young children are developmentally able to digest fruit and vegetables and ready to consume animal‐source protein. Through the Baby Friendly Community Initiative platform, cooking demonstrations and key hygiene actions were integrated with complementary feeding messages. Future programming for complementary feeding should consider development of context specific counselling messages on consumption of animal source foods, strengthen production and use of local foods through agriculture‐nutrition linkages, and include complementary indicators through routine health monitoring systems to track progress.

Keywords: baby friendly community initiative, complementary feeding, infant and young child feeding, Kenya, programme implementation, recipes

Key messages.

Address cultural beliefs and taboos on complementary feeding, specifically children's ability to consume animal source foods or meat and digest fruits and vegetables through context‐specific counselling.

Use the national guide for complementary feeding to adapt and roll out these recently developed complementary feeding recipes to other parts of Kenya through BFCI.

Build upon ongoing efforts to improve complementary feeding, through community and backyard gardens, cooking demonstrations, and reinforcement of key hygiene behaviours as part of BFCI.

Monitor complementary feeding indicators via the routine health information systems to ensure complementary feeding data are available at facility and community level.

1. INTRODUCTION

Complementary feeding is defined by World Health Organization (WHO)/Pan American Health Organization as the “process when breastmilk is no longer sufficient to meet the nutritional requirements of the infant, and other foods and liquids are needed alongside breastmilk, from 6‐24 months of age” (Pan American Health Organization [PAHO] & World Health Organization [WHO], 2003). Complementary feeding is a critical component of infant and young child feeding practices (IYCF), and optimal complementary feeding practices have been demonstrated to prevent micronutrient deficiencies, stunting, overweight, and obesity (Bégin & Aguayo, 2017). Although global guidance recommends that mothers and families should introduce complementary foods with sufficient meal frequency and portions' sizes, dietary diversity, appropriate food texture, and safe food preparation and storage (PAHO & WHO, 2003), complementary feeding is also largely dependent not only on what is fed but also on how, when, where, and by whom (PAHO & WHO, 2003). Globally, available data on complementary feeding practices reveal low and stagnant rates of minimum diet diversity, minimum meal frequency, and minimum acceptable diet (United Nations Children's Fund [UNICEF], 2018a, 2018b). A recent analysis of data from 39 countries showed that children aged 6–23 months who consumed only one food group the previous day had a 1.37 higher likelihood of being stunted in comparison with children who consumed greater than five food groups per day (Krasevec, An, Kumapley, Bégin, & Frongillo, 2017). Countries in sub‐Saharan Africa (SSA) report the lowest minimum acceptable diet scores and high rates of children over 8 months of age who have not consumed solid foods the previous day (White, Bégin, Kumapley, Murray, & Krasevec, 2017). Moreover, about half of children residing in SSA do not consume animal‐source foods (White et al., 2017).

1.1. Progress in Kenya on nutrition and health

Kenya is a middle‐income country, which has experienced improved economic growth in recent years and a consistently improving GDP. Between 2011 and 2016, Kenya's GDP increased by nearly 68% (World Bank, 2018). The Government of Kenya has provided universal health care at public facilities (World Bank, 2018), and the country has seen substantial reductions in under‐five mortality—from 2010 to 2017 (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics et al., 2014; UNICEF, 2018b), see Box 1. Kenya is the only country to be on track for all World Health Assembly undernutrition targets (International Food Policy Research Institute, 2015, 2016) and has seen remarkable improvements in nutritional status of children under 5 years of age between 1998 and 2014, with reductions in stunting (from 38 to 26%), wasting (7–4%), and underweight (18–11%) during this time (Kenya National Council for Population and Development, 1999; Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) Kenya, Ministry of Health (MOH) Kenya, and ORC Macro, 2004; Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Kenya Ministry of Health, National AIDS Control Council/Kenya, Kenya Medical Research Institute, National Council for Population and Development/Kenya, 2014). According to the latest (2011) Kenya National Micronutrient Survey, 21.8% of children 6–59 months of age suffer from iron deficiency, whereas iron deficiency anaemia affects 13.3% of children (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Kenya Ministry of Health, & Kenya Medical Research Institute, 2011). Iron deficiency affects more than one quarter of infants 6–11 months of age, while iron deficiency peaks at 12–23 months of age (34.6%; Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Kenya Ministry of Health, & Kenya Medical Research Institute, 2011).

Box 1.

Kenya in a snapshot: Relevant indicators (source: World Bank, 2018 and Global Nutrition Report, 2017)

| Indicators | 2000 | 2010 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population, million | 31.50 | 41.35 | 48.46 |

| Total life expectancy at birth, years | 51 | 63 | 67 |

| Maternal mortality ratio, per 100,000 live births | 759 | 605 | 510 |

| Under‐five child mortality rate, per 1,000 live births | 104.5 | 58.4 | 40.8 |

| Prevalence of stunting among children under five, % | 41 | 35.5 | 26 |

| Gini index score[Link] | 45 | 46.5 | 49 |

| Urban population, % | 20 | 24 | 26 |

The Gini index score measures income distribution or wealth distribution among a population. This is a common measure of economic inequality.

1.2. Government actions for IYCF with a focus on complementary feeding

Progress for nutrition can be attributed, in part, to key actions implemented by the Government of Kenya, which prioritized nutrition in the 2010 revision of the Constitution of Kenya (Government of the Republic of Kenya, 2010). Article 43 (1) states that “every person has the right to be free from hunger and to have adequate food of acceptable quality,” and Article 53 (1c) reinforces this notion that “every child has the right to basic nutrition, shelter and health care.” IYCF practices are often influenced by economic, political, social, and environmental factors (UNICEF, 2018a), and Kenya is no different. Key government actions have translated into half of sub‐counties implementing community breastfeeding and IYCF programmes, the enactment of national legislation for the Code of Marketing of Breast‐Milk Substitutes, as well as the national legislation mandating 13 weeks of paid maternity leave (Global Breastfeeding Collective, UNICEF, & WHO, 2017). Within a 10‐year period, Kenya has experienced dramatic increases in exclusive breastfeeding, from 13% in 2003 to 61% in 2014 (CBS Kenya, MOH Kenya, and ORC Macro, 2004; Kenya National Bureau of Statistics & ICF Macro, 2010; Kenya National Bureau of Statistics et al., 2014).

While impressive gains have been made in exclusive breastfeeding, complementary feeding progress has been slow, and the country has failed to meet targets. The National Nutrition Action Plan (Kenya Ministry of Health, 2012a) sets targets on complementary feeding to improve “proportion of children 6 to 23 months consuming 3+ or 4+ food groups in a day (dietary diversity) from 39% (2008) to 67% (2017; Kenya Ministry of Health, 2011). This is supported by the National Strategy for Maternal Infant and Young Child Nutrition (MIYCN; 2012–2017), which highlights “timely, appropriate adequate and safe complementary feeding” for children 6–23 months (Kenya Ministry of Health, 2012b), the Ministry of Health (MOH). National Dietetics Unit (NDU) also developed the MIYCN National Operational Guidelines for health workers that enabled operationalization of the MIYCN strategy by outlining comprehensive interventions for optimal MIYCN.

The 2014 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) revealed that approximately half of Kenyan children 6–23 months of age met minimum meal frequency and 41% met minimum dietary diversity criteria, whereas only 22% had a minimum acceptable diet, which declined from previous levels of 39% in 2010 (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics et al., 2010, 2014). Foods commonly fed to Kenyan children 6–23 months of age include grains (80%), vitamin‐A‐rich fruits and vegetables (64%), roots and tubers (38%), and other fruits and vegetables (33%; Kenya National Bureau of Statistics et al., 2014). Yet gaps remain in protein and calcium intake, as only about 20–25% of children, 6–23 months of age, are fed with legumes and nuts, fish, meat, poultry, or eggs, and only 13% of children are fed with milk products (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics et al., 2014). Aside from breast milk, according the Kenya DHS, the majority of children (67%), by 12–17 months of age, are fed with liquids, such as juice, juice drinks, clear broth, other nonmilk liquids, which may displace consumption of solid and semi‐solid nutritious foods. Recent multivariate analysis of complementary feeding data revealed that children aged 6–23 months (n = 2,740) in Kenya received an average of 2.9 food groups and one animal‐source food group (which was analysed according to consumption of eggs, meat, or dairy; Krasevec et al., 2017), according to 24‐hr intake. Given the Kenya target is consumption of at least four food groups per day by children 6–23 months of age, these data suggest that accelerated efforts are needed to improve complementary feeding.

1.3. Government actions to accelerate complementary feeding: National Guide for Development of Complementary Feeding Recipes

Recognizing these identified gaps in complementary feeding, the MOH, NDU developed guidance to accelerate key actions for complementary feeding (see Figure 1 for timeline of activities). In 2018, a National Guide to Complementary Feeding 6–23 Months (Kenya Ministry of Health, 2018) provided a simplified way of distilling WHO standards on complementary feeding. The objective of the guide is to improve communication to caregivers of children 6–23 months of age on complementary feeding practices, as well as provide recommendations on how to develop and roll‐out complementary feeding recipes using locally available foods. The guide was designed to assist counties' health workforce, including community health extension workers, community health volunteers/workers (CHVs), home economics, agricultural extension workers, and development and implementing agencies working with families and community groups, on how to interpret WHO recommendations on complementary feeding (Kenya Ministry of Health, 2018).

Figure 1.

Timeline of roll‐out of policies, guidance, and activities related to complementary feeding, Kenya

National guidance on complementary feeding for children 6–23 months of age provides the following:

Instructions for health workers on how to counsel mothers and communities on preparing recipes for young children using locally sourced and safe foods;

Information on when and how to introduce complementary foods;

Guidance on food safety and hygiene;

Guidance on food preparation and food preservation methods;

Guidance on household measurements for appropriate serving portions by age group; and

Information on how to include a greater variety of nutrient‐rich foods in children's diets.

The six basic criteria for complementary feeding—frequency, amount, texture, variety, adequacy, active feeding, and hygiene (FATVAAH) according to child age and health status are reinforced in the national guide, alongside identification of locally available foods, cultural beliefs, and traditional practices affecting food choice (Table 1).

Table 1.

Frequency, amount, texture, variety, active feeding, and hygiene (FATVAH) criteria for complementary feeding, Kenya

| Frequency: The meal frequency should be based on the age appropriate recommendations. |

| Amount: The amount of food given to the young child at each meal should be adequate for the age and provide sufficient energy, protein, and micronutrients to meet the growing child's nutritional needs. |

| Texture: The food consistency should be age appropriate and adapted to the child's requirements and abilities. |

| Variety: A child should eat a variety of foods that provide different nutrients to meet the child's nutritional needs. |

| Active feeding: Encouraging and support a child to eat enough food at each meal. |

| Hygiene: Foods should be hygienically prepared, stored, and fed with clean hands using clean utensils—Bowls, cups, and spoons. |

1.4. Development of local complementary feeding recipes in Western Kenya through trials of improved practices

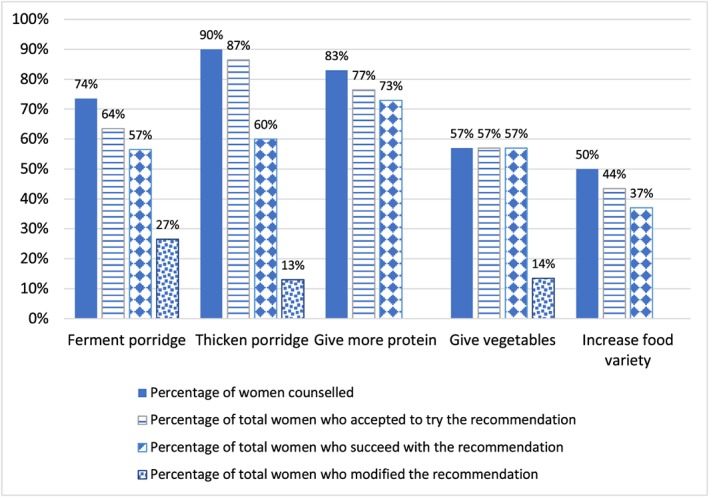

Using the National Guide to Complementary Feeding 6–23 Months (Kenya Ministry of Health, 2018), United States Agency for International Development's (USAID's) Maternal and Child Survival Programme (MCSP) developed local complementary feeding recipes for Migori and Kisumu counties in Western Kenya, together with the Ministry of Agriculture, MOH nutritionists, and community health volunteers. Trials of improved practices (TIPs)—a formative research technique using a participatory approach to test actual practices—were utilized to develop culturally appropriate complementary feeding recipes, hand in hand with the national guide (Dicken, Griffiths, & Piwoz, 1997; Manoff Group, 2005). Through the use of TIPs and a series of three household visits, in‐depth interviews were conducted with 30 mothers of children, 6–23 months of age, and selected feeding challenges were identified through discussion (Visit 1). Mothers were provided culturally relevant “small” doable recommendations (Visit 2), based on the challenges they faced, and counselled by MOH nutritionists to make small changes in feeding practices, over a 1‐week period (between Visits 2 and 3; see Figure 2). Following a 1‐week period, mothers were visited in their homes (Visit 3) to gain feedback on the experience (i.e., succeeded or modified recommendation). Most mothers succeeded with following recommendations (Figure 2). Common feeding challenges identified through TIPs included provision of watery, thin porridge, lack of fermentation of porridge to release key nutrients, low consumption of animal‐source foods, and low dietary diversity in Migori and Kisumu communities.

Figure 2.

Kisumu and Migori—Main outcomes by % of mothers with children 6–23 months (N = 30)

1.5. Approaches for improving and monitoring complementary feeding in existing health platforms

Through the development of 23 local recipes, MCSP was able to address concerns, which mothers raised with understanding of which foods are best for complementary feeding. Some mothers relayed challenges in the lack of information on how to prepare, modify, and cook foods for young children 6–23 months of age. Mothers discussed the need for information on how to thicken porridge, which foods to introduce and when, and how to prepare meat to prevent choking among children (see Table 2). Addressing cultural beliefs around complementary feeding meant providing mothers' reassurance that young children are developmentally able to and “ready” to digest fruit and vegetables at this age, feeding eggs would not cause delays in speech or hinder teeth development, and children are ready to consume animal‐source protein/meat, and liquids, such as broth, alone were not sufficient. Cooking demonstrations carried out through mother‐to‐mother support groups in all 53 MCSP supported Baby‐Friendly Community Initiative (BFCI) communities, which gave mothers an understanding of the seven food groups and how to prepare and feed locally available healthy meals and snacks for their young children (n = 20 in Kisumu and 33 in Migori counties). BFCI, a high impact nutrition intervention for Kenya, is an extension of the 10th step of the Ten Steps of Successful Breastfeeding and provides support for both breastfeeding and complementary feeding at the community level (Kavle et al., 2019). Cooking demonstrations carried out through these support groups provided practical guidance for mothers on how to prepare and modify foods, such as mashing, dicing, grating, and shredding foods according to feeding recommendations based on age (see Table 2). In addition, BFCI implementation enabled routine monitoring of complementary feeding indicators on a monthly basis at community and sub‐county levels by community health volunteers. Through BFCI, two indicators were tracked: proportion of children 6–8 months introduced to solid and semi‐solid foods and the proportion of children 6 months–1 year of age receiving animal‐source/iron‐rich foods in the last 24 hr (Kavle et al., 2019).

Table 2.

Key counselling messages on complementary feeding, children 6–23 months, by feeding problem, recommendation, and motivation, Migori and Kisumu counties, Kenya (source: Maternal and Child Survival Program, 2017)

| Feeding problem | Recommendation | Motivation |

|---|---|---|

| Child has not been introduced to complementary foods, as mother does not have information on foods that are appropriate for child. |

• Add other foods to “complement” breast milk. • Start feeding baby soft, mashed foods two times per day. • Food should be thick, not watery (should not fall‐off a spoon easily), for example, mashed vegetables (carrot, potato, tomato, green leafy vegetables—like spinach, sweet potato) and fruits (banana, mango, orange, etc.). • Introduce one food at a time. • Start with two tablespoons at each feed and increase to three tablespoons in the third to fourth week as the baby needs time to get used to new food. • Use a separate plate to feed the baby to make sure he or she eats all the food given. • Breastfeed before giving other foods. |

• At this age, breast milk alone is not enough for your baby's development; your baby needs more food. • By 6 months, your baby is hungry for food. • Your baby needs other food in addition to breast milk to continue to grow well physically and mentally. • Baby can swallow well by now if foods are soft or mashed. • Feeding your baby with nutritious foods protects your baby against many illnesses. |

| Child is eating less than the required quantities of food per day and fed fewer times. |

• Increase the frequency based on the age. • Feed the baby in their own bowl to ensure the baby eats all the food given. • Breastfeed between meals and at night. • Give the baby a variety of foods, including fruit, vegetables, cereals, meat, eggs, and dairy products (e.g., milk, fermented milk, and yogurt). |

• Receiving adequate quantities of food protects your baby against many illnesses. • Your baby will be happier, more satisfied, and not hungry. • Your baby needs to eat more now to grow healthy, taller, play well, be active, and learn in school. |

| Baby is not eating enough meat (including beef and chicken). |

• Increase the amount of animal‐source iron‐rich foods in the diet. This includes chicken, fish, beef, and liver. • Cook meat until it is well cooked and soft for the baby to chew. • Modify the meat to enable the child to chew and swallow easily (i.e., grinding, mincing, and cutting the meat into tiny pieces). |

• Meat provides high‐quality protein and micronutrients. • Animal‐source foods are especially good for children to help them grow strong and healthy. |

| Baby's diet is not inclusive of enough fruits and vegetables. |

• Mash the fruits and vegetables to enable the baby to eat comfortably. • Use fruits and vegetables that are available and in season. • If the baby does not like the fruit/vegetable, you can disguise it by adding it to other foods. |

• Fruits and vegetables are rich in vitamins (vitamin C) and minerals to help the child grow well and to keep the child healthy. • Most fruits and vegetables are locally available and affordable when in season. • Green leafy vegetables are rich in vitamins and minerals, such as iron. |

| Baby's porridge is thin and watery in consistency. |

• Porridge should be thick, not watery (should not fall‐off the spoon easily). • Porridge should be “eaten” not “drank.” |

• Thick porridge is dense enough to provide the required energy for the baby. • Thick porridge keeps the baby satisfied for a prolonged period of time. |

| Child's food is not cooked with oil. |

• Start cooking the baby food with a little bit of oil. • Use a moderate quantity of oil (one to two tablespoons) based on the quantity of food being prepared. • Use vegetable (liquid) oil, such as corn oil, olive oil, sunflower oil, which are healthier than cooking fats and margarine. |

• The baby tends to enjoy food that is cooked with oil. • Oil is needed to help with the absorption of nutrients such as vitamins A, D, E, and K into the body as well as making the food energy dense. • The child can eat family foods prepared with oil. • Mother spends less time and money preparing separate foods for child. |

| Child is not eating family foods. |

• Introduce the baby to family foods. • Give balanced diet just like the rest of the family. • As the child grows, change the consistency. • Use responsive feeding approach. • Increase amount of food to meet recommended daily caloric intake. • Avoid unhealthy snacks such as chips, soda, cake, and sweets, and instead, give fruits. |

• Feeding the baby foods prepared for the family cuts down on preparation time. • It is cheaper since you use foods meant for the family and do not buy separate foods. |

| Child is eating unhealthy snacks (e.g., soda, processed juice, or fried potatoes with sauce) and tea given as a meal. |

• Stop giving unhealthy processed “junk” foods, such as soda, processed juice, fried potatoes with sauce, and biscuits. • The healthy snacks recommended included locally available fruits, nuts, and porridge. • Give healthier snacks, such as fruits (e.g., whole bananas, avocado, mangoes, and oranges). • Avoid giving tea (with or without milk) to the baby at any time. • Give milk without mixing it with other foods. |

• Unhealthy snacks only add fats and sugars and no other nutrients. • Unhealthy snacks are more expensive. • These foods will not help your child to grow well and do not contribute to good health. • Healthy snacks have more nutritive value. • Fruits and nuts—such as peanuts—are available locally and affordable. • Fruits improve the appetite of the child. • Tea has little nutritive value for the child. • Milk given separately provides protein and calcium needed for bone growth and strong teeth. |

| Child is eating less than the required quantities of food per day and fed fewer times. |

• Increase the frequency based on the age. • Feed the baby in their own bowl to ensure the baby eats all the food given. • Breastfeed between meals and at night. • Give the baby a variety of foods, including fruit, vegetables, cereals, meat, eggs, and dairy products (e.g., milk, fermented milk, and yogurt). |

• Receiving adequate quantities of food protects your baby against many illnesses. • Your baby will be happier, more satisfied, and not hungry. • Your baby needs to eat more now to grow healthy, taller, play well, be active, and learn in school. |

Integration of complementary feeding interventions into BFCI was critical. BFCI builds upon the 10th step of BFHI, by creating a comprehensive support system at the community level through the establishment of mother‐to‐mother and community support groups to improve health and nutrition outcomes (World Health Organization & UNICEF, 2009). BFCI provided a platform for mothers to participate in mother‐to‐mother and community support groups, receive home visits from community volunteers, and provide community‐based support for breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices (Kenya Ministry of Health, 2016a, 2016b). Community support groups oversee activities in the community related to breastfeeding and complementary feeding. Mother Support Groups were formed by unpaid CHVs, who mobilize the mothers and meet on a monthly basis to discuss challenges with infant and young child feeding and ways to resolve these problems. The frequency of the meetings varied based on their commitment and the passion of the members and leaders, as no incentives were provided. Engaging champions for BFCI (i.e., CHVs and community leaders) as well as incorporating income generation activities within support groups were key ways to sustain these support groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

National guide to complementary feeding for children 6–23 months of age, Kenya

|

All the food above can be eaten by children from 6 months onwards; however, these foods have to be modified to suit the age of the child. There are various methods of modifying foods for children as listed below: ❖ Mashing, for example, beans, sweet potatoes, butter nut, and fruits; ❖ Shredding of flesh foods, for example, beef, fish, and poultry; ❖ Pounding sardines (i.e., omena); ❖ Grating, for example, carrots, beetroots, and boiled eggs; ❖ Grinding, for example, ground nuts; and ❖ Vertical slicing, dicing, and mincing. There are various methods for modifying foods for children, depending on the age of the child, as denoted below: ❖ At 6 months of age—mashing; ❖ At 7–8 months of age—mashing, pounding, grating, shredding, grinding, and mincing; ❖ At 9–11 months of age—mashing, mincing, grating, shredding, slicing, dicing, finger foods, for example, whole fruits, for example, banana and mango; and ❖ At 12–23 months of age—finger foods, dicing, slicing, mincing, whole foods. |

1.6. Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) integration into complementary feeding sessions

Key messages on hygiene and food safety are an essential component of complementary feeding practices and BFCI. Through the BFCI platform, key hygiene actions were integrated with complementary feeding messages by CHVs during mother‐to‐mother support group meetings and household visits, with focus on the critical times for handwashing. Key WASH messages discussed with communities included the following: (1) Cover food while cooking and during storage to prevent contamination; (2) wash well fruits and vegetables prior to eating and cooking; (3) cook flesh foods and eggs well; and (4) clean utensils and dry‐washed utensils on a dish rack. Mothers were also advised to use latrines, encourage latrine use among other family members, properly dispose of faeces and diapers after the child defecates, and to have clean play areas by keeping animal faeces away from children, which prevents diarrhoea and other illnesses (Kenya Ministry of Health, 2018).

1.7. Future programme considerations for complementary feeding in Kenya

Empower communities to produce and use local foods through strengthened agriculture–nutrition linkages (Muehlhoff et al., 2017). This builds on concerted efforts to improve complementary feeding, through community and backyard gardens, cooking demonstrations, and reinforcement of key hygiene behaviours as part of BFCI (Kavle et al., 2019).

Address any cultural beliefs and taboos through context specific counselling on consumption of animal source, protein‐rich foods, as evidence that providing young children with meat/flesh foods, eggs, and dairy products is particularly influential in the prevention of stunting (Chandrasekhar, Aguayo, Krishna, & Nair, 2017; Krasevec et al., 2017; White et al., 2017).

Using the national guide for complementary feeding adapt these complementary feeding recipes to other parts of the country, according to local cultural context, and available foods (Daelmans et al., 2013; Kenya Ministry of Health, 2013a). These recipes should continue to be delivered via cooking demonstrations and further expansion of BFCI to all community units, which is essential to improving complementary feeding at scale (Maingi, Kimiywe, & Iron‐Segev, 2018).

Monitor complementary feeding indicators systematically through BFCI via the routine health information systems (i.e., District Health Information Software 2, to ensure complementary feeding data are available at all levels, at facility, and community level (Jefferds, 2017; Kavle et al., 2019) utilize tools/software to analyse progress made in complementary feeding indicators on a routine (i.e., quarterly/biannual) basis (Daelmans et al., 2013; Untoro et al., 2017).

Roll‐out of point‐of‐use fortification of local complementary foods with micronutrient powders, as per Kenya National Guidelines (Kenya Ministry of Health, 2013b), is recommended to be part of IYCF counselling and malaria programming to strengthen integrated efforts to address iron deficiency and anaemia (Begin & Aguayo, 2017; Siekmans, Bégin, Situma, & Kupka, 2017; WHO, 2016). In addition, confirmation of the extent of iron deficiency and child anaemia in the population (or subpopulations), as a public health problem, is of importance using recent data, prior to implementation.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

We declare no conflict of interests. USAID provided review of the manuscript; authors had intellectual freedom to include feedback, as needed.

CONTRIBUTIONS

BA and JAK conceptualized and led the writing of the paper. SS and CG were involved in writing of the paper. All authors were involved in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

FUNDING

This article is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of the Cooperative Agreement AID‐OAA‐A‐14‐00028. The contents are the responsibility of the Maternal and Child Survival Program and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

Ahoya B, Kavle JA, Straubinger S, Gathi CM. Accelerating progress for complementary feeding in Kenya: Key government actions and the way forward. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15(S1):e12723 10.1111/mcn.12723

Footnotes

GDP at purchasing power parity increased by 37% between 2000 and 2011.

- Achieve a 40% reduction in the number of children under‐five who are stunted;

- Achieve a 50% reduction of anaemia in women of reproductive age;

- Achieve a 30% reduction in low birthweight;

- Ensure that there is no increase in childhood overweight;

- Increase the rate of exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months up to at least 50%; and

- Reduce and maintain childhood wasting to less than 5%.

This figure is for all breastfed and nonbreastfed children. For breastfed children, minimum meal frequency is receiving solid or semi‐solid food at least twice a day for infants 6–8 months and at least three times a day for children 9–23 months. For nonbreastfed children age 6–23 months, minimum meal frequency is receiving solid or semi‐solid food or milk feeds at least four times a day.

4+ food groups for all children, for food group detail, refer to Kenya DHS 2014.

As defined by WHO for diet diversity (WHO, 2008): flesh food (meat, poultry, fish, and organ meat), dairy products, eggs, grains or tubers, pulses or legumes or nuts, vitamin‐A‐rich fruits and vegetables, and other fruits and vegetables.

The draft complementary feeding guide is in the process of being finalized by the Government of Kenya.

These health workers include community service providers such as community health assistants, community health workers, home economics, agricultural extension workers, and development and implementing agencies from health, education, and community development, local government, and agricultural sectors working directly with families and communities (Kenya Ministry of Health, 2017).

The Maternal and Child Survival Program is a global U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) cooperative agreement to introduce and support high‐impact health interventions in 25 priority countries with the ultimate goal of ending preventable child and maternal deaths (EPCMD) within a generation. The Kenya program built on the previous 5‐year USAID‐funded Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP), which began in 2009 and focused on providing national level technical assistance for maternal and child health and nutrition.

REFERENCES

- Bégin, F. , & Aguayo, V. (2017). First foods: Why improving young children's diets matter. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(Suppl 2), e12528 10.1111/mcn.12528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) Kenya, Ministry of Health (MOH) Kenya, and ORC Macro . (2004). Kenya demographic and health survey 2003. Calverton, Maryland: CBS, MOH, and ORC Macro. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar, S. , Aguayo, V. , Krishna, V. , & Nair, R. (2017). Household food insecurity and children's dietary diversity and nutrition in India. Evidence from the comprehensive nutrition survey in Maharashtra. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(Suppl 2), e12447 10.1111/mcn.12447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daelmans, B. , Ferguson, E. , Lutter, C. , Singh, N. , Pachon, H. , Creed‐Kanashira, H. , & Briend, A. (2013). Designing appropriate complementary feeding recommendations: Tools for programmatic action. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 9(2), 116–130, 130. 10.1111/mcn.12083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicken, K. , Griffiths, M. , & Piwoz, E. (1997). Designing by dialogue: A program planner's guide to consultative research for improving young child feeding. Washington: Support for Analysis and Research in Africa Project. [Google Scholar]

- Global Breastfeeding Collective, United Nations Children's Fund . (2017). Global breastfeeding scorecard, 2017: Tracking progress for breastfeeding policies and programmes. New York: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Republic of Kenya . (2010). The Constitution of Kenya. 193. Nairobi: Government of the Republic of Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- International Food Policy Research Institute . (2015). Global nutrition report 2015: Actions and accountability to advance nutrition and sustainable development. Washington: International Food Policy Research Institute. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Food Policy Research Institute . (2016). Global nutrition report 2016: From promise to impact: Ending malnutrition by 2030. Washington: International Food Policy Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferds, M. (2017). Government information systems to monitor complementary feeding programs for young children. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(Suppl 2), e12413 10.1111/mcn.12413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavle, J. A. , Ahoya, B. , Kiige, L. , Mwando, R. , Olwenyi, F. , Straubinger, S. , & Mkiwa, C. (2019). Baby friendly community initiative—From national guidelines to implementation: A multisectoral platform for improving infant and young child feeding practices and integrated health services. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 15(Suppl 1), e12747 10.1111/mcn.12747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenya Ministry of Health . (2012a). National nutrition action plan 2012–2017. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya Ministry of Health . (2012b). National strategy for maternal, infant and young child nutrition 2012–2017. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya Ministry of Health . (2013a). National maternal, infant and young child nutrition: Policy guidelines. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya Ministry of Health . (2013b). National policy guideline on home fortification with micronutrient powder for children 6–23 months in Kenya. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya Ministry of Health . (2016a). Baby friendly community initiative external assessment protocols. 60. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya Ministry of Health . (2016b). Baby friendly community initiative implementation guidelines. 72. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya Ministry of Health . (2018). A guide to complementary feeding 6 to 23 months. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics and ICF Macro . (2010). Kenya demographic and health survey 2008–09. Calverton: KNBS and ICF Macro. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Kenya Ministry of Health, & Kenya Medical Research Institute . (2011). Kenya national micronutrient survey 2011. Nairobi. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Kenya Ministry of Health, National AIDS Control Council/Kenya, Kenya Medical Research Institute, National Council for Population and Development/Kenya, a . (2014). Kenya demographic and health survey key indicators 2014. Calverton: Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Health/Kenya, National AIDS Control Council/Kenya, Kenya Medical Research Institute, National Council for Population and Development/Kenya, and ICF International. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National Council for Population and Development Central Bureau of Statistics (Office of the Vice President and Ministry of Planning and National Development) [Kenya] . (1999). Kenya demographic and health survey 1998. Calverton: NDPD, CBS, and MI. [Google Scholar]

- Krasevec, J. , An, X. , Kumapley, R. , Bégin, F. , & Frongillo, E. (2017). Diet quality and risk of stunting among infants and young children in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(Suppl 2), e12430 10.1111/mcn.12430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maingi, M. , Kimiywe, J. , & Iron‐Segev, S. (2018). Effectiveness of baby friendly community initiative (BFCI) on complementary feeding in Koibatek, Kenya: A randomized control study. BMC Public Health, 18, 600 10.1186/s12889-018-5519-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoff Group . (2005). Trials of improved practices (TIPs): Giving participants a voice in program design some recent applications of the TIPs methodology. Washington: Manoff Group. [Google Scholar]

- Maternal and Child Survival Program . (2017). A counselling guide for complementary feeding for children 6–23 months in Kisumu and Migori, Kenya: Based on results of the trials of improved practices (TIPs) complementary feeding assessment. Washington: Maternal and Child Survival Program. [Google Scholar]

- Muehlhoff, E. , Wijesinha‐Bettoni, R. , Westaway, E. , Jeremias, T. , Nordin, S. , & Garz, J. (2017). Linking agriculture and nutrition education to improve infant and young child feeding: Lessons for future programmes. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(Suppl 2), e12411 10.1111/mcn.12411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) & World Health Organization (WHO) . (2003). Guiding principles for complementary feeding of the breastfed child. Washington: PAHO. [Google Scholar]

- Siekmans, K. , Bégin, F. , Situma, R. , & Kupka, R. (2017). The potential role of micronutrient powders to improve complementary feeding practices. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(Suppl 2), e12464 10.1111/mcn.12464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children's Fund . (2018a). Adopting optimal feeding practices is fundamental to a child's survival, growth and development, but too few children benefit. Retrieved from Adopting optimal feeding practices is fundamental to a child's survival, growth and development, but too few children benefit: http://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/infant-and-young-child-feeding/

- United Nations Children's Fund . (2018b). UNICEF data: Monitoring the situation of children and women—Malnutrition data. Retrieved from UNICEF Data: Monitoring the Situation of Children and Women: https://data.unicef.org/data/malnutrition/

- Untoro, J. , Childs, R. , Bose, I. , Winichagoon, P. , Rudert, C. , Hall, A. , & de Pee, S. (2017). Tools to improve planning, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of complementary feeding programmes. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(Suppl 2), e12438 10.1111/mcn.12438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, J. M. , Bégin, F. , Kumapley, R. , Murray, C. , & Krasevec, J. (2017). Complementary feeding practices: Current global and regional estimates. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(Suppl 2), e12505 10.1111/mcn.12505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . (2018). The World Bank in Kenya: Kenya overview. Retrieved from World Bank: http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/kenya/overview

- World Health Organization . (2016). WHO guideline: Use of multiple micronutrient powders for point‐of‐use fortification of foods consumed by infants and young children aged 6–23 months and children aged 2–12 years. 66. Geneva: World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, & UNICEF. (2009). Baby‐friendly hospital initiative: Revised, updated and expanded for integrated care. Geneva: World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, & United Nations Children's Fund. (2003). Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]