Abstract

Objectives

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) are groups of healthcare providers responsible for quality of care and spending for a defined patient population. The elimination of low-value medical services will improve quality and reduce costs, and therefore, ACOs should actively work to reduce the use of low-value services. We set out to identify ACO characteristics associated with implementation of strategies to reduce overuse.

Study Design

Survey analysis

Methods

We used the National Survey of ACOs to determine the percentage of responding ACOs aware of Choosing Wisely and to what degree ACOs have taken steps to reduce the use of low-value services. We identified characteristics of ACOs associated with implementing low-value care reducing strategies using three statistical models (Stepwise and Lasso logistic regression, Random Forest).

Results

Responding executives of 155 out of 267 ACOs (58%) were aware of Choosing Wisely. 84 ACO leaders said that their ACOs also actively implemented strategies to reduce the use of low-value services, largely through educating physicians and stimulating shared decision making. All three models identified the presence of at least one commercial payer contract and prior, joint experience pursuing risk-based payment contracts as the most important predictors of an ACO actively implementing strategies to reduce low-value care.

Conclusions

In the first year of implementation, only one third of ACOs had taken steps to reduce the use of low-value medical services. Safety-net ACOs and those with little experience as a risk-bearing organization need more time and support from healthcare payers and the Choosing Wisely campaign to prioritize the reduction of overuse.

Keywords: ACO, overuse, payment reform, Choosing Wisely

Précis

Experience with risk-based contracting best predicts active engagement of ACOs in reducing low-value medical services, mainly through physician education and encouraging shared decision making.

Introduction

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) are voluntary groups of provider organizations that are collectively held accountable for both quality of care and total spending for a defined group of patients through payment contracts. A promising strategy to improve quality and financial sustainability involves the reduction of low-value medical services. Indeed, prior research shows a modest decrease in the use of low-value care, and thus in spending rates, for ACOs when compared to non-ACO providers with predominantly fee-for-service payment models.1 While utilization and related spending have decreased in ACOs, quality scores and care satisfaction have remained similar, or improved compared to other organizations.2,3,4 However, it is not clear what strategies ACOs deploy to lower unnecessary care, nor what features predict a commitment towards overuse reduction.

One way to tackle low-value care is to embrace the Choosing Wisely campaign.5 Choosing Wisely aims to reduce the delivery of low-value medical services by promoting conversations between patients and physicians on the appropriateness of care. Over seventy U.S. specialty societies have defined concise lists of five to ten wasteful interventions that “physicians and patients should question.”5 The synergies of ACOs and Choosing Wisely regarding care improvement and overuse reduction suggest that ACOs committed to reducing low-value care should be aware of this campaign and also prone to actively lower the utilization of these medical services. In this study, we analyze data from the National Survey of ACOs (NSACO) to determine which strategies are used to reduce low-value care and identify the ACO characteristics that predict the use of such methods.

Methods

The National Survey of ACOs

The National Survey of ACOs is an online survey designed by researchers at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and the University of California, Berkeley. It questions ACOs (Medicare Shared Savings ACOs, Medicare Pioneer ACOs, state Medicaid ACOs, and commercial payer ACOs), on their composition, characteristics, contracts and capabilities.6,7 A total of 752 ACOs were identified through public documents, provider surveys, scientific literature and certification by the National Committee for Quality Assurance and invited to participate. Senior ACO executives including Chief Executive Officers, Executive Directors, and Chief Medical Officers filled out the survey. At the time of our analysis, the survey was fielded in three consecutive waves, with each wave questioning newly formed ACOs (Wave 1: Oct 2012 – May 2013; Wave 2: Sept 2013 – March 2014; Wave 3: Nov 2014 – May 2015). The median duration between the implementation of the ACO contract to the time of the survey was 11.6 months (interquartile range: 7.1 - 13.2 months).7 Over all three waves, 64% of ACOs filled out the survey. Wave 2 and Wave 3 of the survey were more elaborate and therefore ACOs from Wave 1 were approached with a follow-up survey asking additional questions during the fielding of Wave 3. Questions about Choosing Wisely were not asked in Wave 1, excluding from our analysis 93 ACOs that participated in the first wave but not in the follow-up survey. Survey questions related to Choosing Wisely included the following: 1) “Are you aware of the Choosing Wisely program?”, and if the response was positive, 2) “What steps have you taken to reduce the use of Choosing Wisely tests and procedures?”

Multivariate statistical modeling

We divided our sample into two groups: 1) ACOs not aware of the Choosing Wisely campaign or aware but not taking steps to support it, and 2) ACOs taking steps to actively reduce the use of low-value medical services.

We compiled an a priori list of 62 survey responses that could be associated with the decision to take steps to support Choosing Wisely (see Table, Supplemental Data 1, which lists these characteristics). Based on existing hypotheses about how these characteristics might affect an ACO’s decision to take steps to reduce overuse, and on simple pairwise significance tests, we then selected a subset of 22 variables from this list. We excluded ACO characteristics on quality behavior in order to prevent potential reverse causality with waste reducing efforts. To identify the main drivers behind the decision to take steps to reduce overuse within those 22 variables, we used both logistic regression (stepwise regression and LASSO regression) and classification techniques (Random Forest).8 Stepwise logistic regression was performed both backward and forward. LASSO imposes shrinkage constraints on the variables, resulting in an optimal model with only those characteristics that have a coefficient > 0. Random Forest stratifies the predictor space in regions with non-linear boundaries between variables, producing multiple decision trees that are combined into a single consensus prediction. The three different statistical approaches identified three sets of prediction variables and we subsequently assessed consistency of associations across these three models. Furthermore, we evaluated the relative predictive merits of each model by comparing their ROC curves and confusion matrices on the basis of their implied misclassification rates (fraction of false positives and false negatives).

Savings and Medicare Shared Savings Program quality scores

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) publicly report shared savings payments and the outcomes of 33 quality measures per performance year for each participating ACO. The quality scores are in four domains: patient experience (including a measure on shared decision making), care coordination, at-risk measures, and preventive care. We calculated an overall quality score and a quality score per domain for the first two performance years of each ACO (the year in which the ACO filled out the survey) using the CMS sliding scale approach as described elsewhere.7,9 We compared these quality scores and the savings per beneficiary attributed to the ACO according to CMS in the first two years with reference to historical expenditure benchmarks, between ACOs taking steps to reduce overuse and ACOs not taking steps, using a two-sample t-test.

Results

Characteristics of ACOs taking steps to reduce overuse

Out of 305 potential ACOs (Wave 1 follow-up: 82 ACOs; Wave 2: 95 ACOs; Wave 3: 128 ACOs), survey respondents for 267 ACOs answered the question “Are you aware of the Choosing Wisely program?”. Of these, 58% (155 ACOs) reported awareness of Choosing Wisely but only 31.5% (84 ACOs) said they had also taken steps to reduce the use of low-value services (see Table, Supplemental Data 1, which characterizes these ACOs). Consequently, 183 ACOs (68.5%) did not take such steps, partly because they were not aware of the Choosing Wisely campaign.

Compared to ACOs not taking steps, ACOs who had implemented strategies to reduce waste included more hospitals in their largest contract (p<0.01), and were significantly more likely to consider themselves an integrated delivery system (p<0.01) (see Table, Supplemental Data 1., which compares these two groups). Provider organizations within ACOs implementing those strategies more often jointly pursued risk-based payment contracts in the past (p<0.01), and this group of ACOs had previously participated in a higher number of payment reform efforts than ACOs that did not take steps (p<0.01). More ACOs taking steps to reduce waste had at least one commercial contract (p<0.01) and Medicare contracts were less prevalent (p=0.03). While their commercial contracts were more often characterized by both bonus and downside risk (p=0.02) than by a bonus only (p=0.03), this bonus was less often constituent upon quality metrics (p=0.02). In addition, ACOs that actively reduced low-value services were more likely to allocate shared savings bonus payments across participating members (p=0.04), compensate physicians based on clinical quality measures (p=0.01) and share cost measures amongst their physicians (p=0.02). A larger proportion of ACOs that were not aware or not actively reducing waste were safety net organizations (p<0.01), defined as more than 25% uninsured or Medicaid beneficiaries.

Of the 84 ACOs that reported using strategies to reduce low-value care, only 57 ACOs (68%) were asked to specify the steps they had taken, because this question was added to the survey after wave 2. On average, these ACOs took three different steps. The most frequently reported waste lowering strategies included: educating physicians on low-value tests and procedures (82.5% of ACOs), encouraging discussions between physicians and patients about appropriate care (73.7%) and disseminating Choosing Wisely material (68.4%) (Table 1). Other strategies included handing out decision guides for patients, pop-ups reminding physicians of the low value of certain tests and procedures in the electronic health record, and audit-and-feedback on individual physician performance. Few ACOs (3.5%) reported taking steps to reduce waste by changing physician payment incentives.

Table 1.

Steps taken to reduce low-value services by 57 ACOs that were asked to specify which actions they had undertaken.

| ACOs taking steps (%) | |

|---|---|

| Educate physicians on low value tests/procedures | 47 (82.5) |

| Encourage patient-physician discussion on appropriate care | 42 (73.7) |

| Disseminate Choosing Wisely materials | 39 (68.4) |

| Provide decision guides for patients | 23 (40.4) |

| Incorporate computer decision support | 20 (35.1) |

| Feedback and benchmark reports to physicians on individual utilization of low-value tests/procedures | 13 (22.8) |

| Change physician payment incentives | 2 (3.5) |

ACO: Accountable Care Organization

Predictors for implementing strategies to reduce low-value care

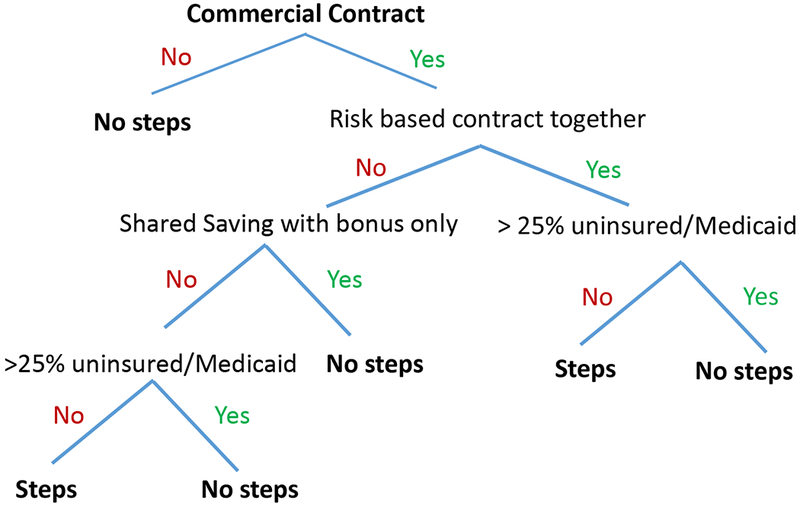

Backward and forward stepwise logistic regression identified the same six variables and similar importance for predicting the use of low-value care reducing strategies (Table 2). ‘The presence of at least one commercial contract’ and ‘prior participation of all provider organizations within the ACO in risk-based payment contracts’ were the most important factors. These were also the two most significant predictors in the LASSO model (see Figure, Supplemental Data 2). This model gave only one negative predictor, predicting an ACO would not actively seek waste reduction. The characteristic, namely ‘more than 25% uninsured or Medicaid patients’, was fourth in order of importance, and also one of the six characteristics in the stepwise regression (Table 2). In the consensus prediction tree from the Random Forest, the third model we used, the same two variables (‘at least one commercial contract’ and ‘prior joint experience with risk-based payment contracts’) were the two highest branches in the decision tree (Figure 1). Similarly, ‘having more than 25% uninsured or Medicaid patients’ was the most influential negative predictor in this model. In conclusion, our working model to predict which ACOs would deploy strategies to reduce low-value care consisted of two positive predictors indicating joint experience in risk-taking in the form of financial models, and one negative predictor, namely a large contingent of safety net patients.

Table 2.

Predicting variables for taking steps to reduce the use of low-value tests and procedures by ACOs from the National Survey of Accountable Care Organizations; Logistic regression model, stepwise approach.

| Variable | Estimate | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| The ACO has a commercial contract | 1.75 | < 0.0001* |

| All organizations in the ACO have pursued a risk-based payment contract together in the past | 1.14 | 0.002* |

| Physicians are compensated based on clinical quality measures | 1.12 | 0.03* |

| Shared savings in commercial contract with bonus only | − 1.00 | 0.01* |

| >25% of patients in the ACO are uninsured or Medicaid beneficiaries | − 2.06 | 0.002* |

| ACO is led either by physicians, or jointly by physicians and hospital | − 0.47 | 0.27 |

ACO: Accountable Care Organization

Figure 1.

Consensus tree by Random Forest

Consensus tree being deduced from multiple decision trees produced by the Random Forest method. ‘Having a commercial contract’ and ‘having pursued a risk-based payment contract together in the past’ are most decisive in the prediction for an ACO to take steps or not. More than 25% uninsured or Medicaid patients leads to ‘no steps’.

The three models exhibited similar minimum misclassification rates on their Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves. The lowest possible misclassification rate for both stepwise regression and LASSO was 24% (see Figure, Supplemental Data 3, which shows the true and false positive rates for the minimum misclassification of each model), while it was 26% for Random Forest (data not shown). This attributes these models a power to identify 33% to 39% of true positives, or ACOs that take steps to reduce low-value care.

Relationship between taking steps and CMS data on quality and savings

Waste reducing strategies were not associated with differences in CMS quality measures or savings per beneficiary for the 158 ACOs for which CMS data were available in performance year 1 (46 ACOs taking steps, 112 ACOs not taking steps) (Table 3). Furthermore, changes in these parameters from performance year 1 to year 2 were similar (32 and 70 ACOs respectively; data not shown).

Table 3.

CMS outcomes and savings per beneficiary for 158 ACOs linked to CMS data, out of 267 ACOs that answered the question ‘Are you aware of Choosing Wisely?’

| ACOs unaware, or not taking steps (112 ACOs) | ACOs taking steps (46 ACOs) | χ2 univariate logistic regression (p value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall quality score (means, performance year 1) a | 70.8 | 73.2 | 0.13 |

| Patient experience | 86.9 | 88.8 | 0.20 |

| Shared decision making only | 74.4 | 74.9 | 0.21 |

| Care coordination | 67.4 | 71.5 | 0.08 |

| Preventive health | 69.3 | 72.1 | 0.22 |

| At risk population (Cardiovascular/Diabetes) | 59.6 | 60.3 | 0.79 |

| Savings per beneficiary (mean $, performance year 1) | 79.7 | −58.40 | 0.13 |

overall quality scores for performance year 1, as calculated with the quality points and domain weight of the 33 individual CMS measures out of 4 domains: patient/caregiver experience; care coordination/patient safety/preventive health/at-risk population (see Medicare Shared Savings Program quality measure benchmarks for the 2014 reporting year9)

ACO: Accountable Care Organization; CMS: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

Conclusions

Based on three waves of the National Survey of ACOs, we show that only a third of all ACOs are taking steps to reduce low-value care. The best predictors for an ACO to deploy strategies for waste reduction were consistent across the three models with various statistical approaches. ACOs with a commercial contract and those whose provider organizations have jointly pursued risk-based payment contracts in the past are more likely to actively reduce overuse. Our finding is consistent with a recent study wherein ACOs with commercial payer contracts were more actively implementing efficiency measures when compared to ACOs with public payer contracts only.7

We found that ACOs with a large contingent of uninsured or Medicaid patients probably do not take steps to reduce overuse. However, the delivery of low-value care is as common among uninsured or Medicaid patients as among the privately insured.10 In prior research, minorities and those with poor and fair health were notably at a higher risk of receiving wasteful medical services.11,12 Both groups are overrepresented in the Medicaid population.13,14 Therefore, safety net ACOs should pay attention to overuse of medical services. However, with relatively fewer resources for quality improvement, these ACOs may be prioritizing underuse of high-value practices over limiting low-value practices.

Furthermore, we did not find correlations between taking steps to reduce overuse and CMS quality measures (including the use of shared decision making), nor between steps and overall savings for ACOs participating in the Medicare Shared Savings Program in the first two performance years. Indeed, although waste in healthcare is ubiquitous,15 quality measures and savings are determined by many other factors than waste reduction alone. In addition, the effect of strategies lowering low-value care, other than clinical decision support and performance feedback, may be limited, certainly if not addressing both patient and provider roles.16 For example, audit-and-feedback methods are efficient in reducing unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions, but only if the intervention is perpetuated.17 Decision aids –but not shared decision making or the dissemination of educational materials— have moderate effect on the use of discretionary surgery.18 Although not yet extensively studied, certain pay-for-performance models have resulted in only modest improvements in care processes and outcomes.19 In our study, only half of ACOs aware of Choosing Wisely took active steps to reduce low-value care and in most of those ACOs, the interventions were low-impact and did not include the most promising strategies for waste-reduction, namely decision aids, computer decision support, and audit-and-feedback on individual physician behavior. To be meaningful, increasing awareness of Choosing Wisely should go hand-in-hand with practical advice for provider-organizations on how to enhance appropriate use of care efficiently. Therefore, more research is needed to determine the correct design of strategies reducing low-value care, the potential to lower utilization of such care in ACOs, and the numeric effect of reductions on quality and savings in the long run.

Several limitations to studies involving NSACO data have been recognized,6,7 notably the fact that survey questions were answered by ACO executives who may not have been aware of efforts to reduce low-value care in their organization and the short period (less than one year) between the start of the ACO contract and the survey. Within this timeframe, ACOs may not yet have been able to initiate strategies to reduce low-value care. Of note, previous comparisons of ACOs filling out the NSACO survey with those who failed to respond have not shown a significant non-response bias in terms of beneficiary or provider composition, organizational structure, overall quality, or saving distribution.6,20,21

Physicians are an important source of low-value care utilization. It explains the focus chosen by Choosing Wisely on conversations between physicians and patients on appropriate care. However, collective risk-taking in financial contracts influences ACOs to actively reduce low-value care more than physician-leadership. It is also possible that other, unobserved characteristics in linkage with risk-bearing experience are influencing an ACO’s decision to seek a reduction in low-value care. In addition, reverse causality (ACOs most confident in their capacity to reduce waste signing risk-bearing contracts) cannot be excluded. However, this would not negatively affect the relationship we detected between collective risk-taking and waste reduction.

The positive influence of risk-bearing on efforts to reduce low-value care may be explained by a combination of resources, incentives and opportunity. First, ACOs contracting with commercial payers may have more stringent contracting requirements that force them to prioritize waste reduction and more resources dedicated to quality improvement than ACOs involved exclusively in public payer contracts. Second, ACOs with prior experience in risk-based contracting may have been able to develop the culture, systems, and technical know-how to tackle challenging issues such as overuse over time. Consequently, ACOs with less experience in risk-bearing and safety net ACOs will likely start prioritizing overuse as they acquire more risk. In the meantime, those ACOs should be otherwise stimulated to reduce overuse, and specifically targeted by advocacy efforts of healthcare payers and the Choosing Wisely campaign. Furthermore, researchers, policy-makers and the Choosing Wisely campaign should focus on defining waste-reducing efforts that are efficient and practical in use, with special attention to audit-and-feedback mechanisms on individual physician performance for both underuse and overuse. With U.S. healthcare spending as high as 18% of GDP, and health care outcomes in the U.S. lagging behind in comparisons with other high-income countries,22 all ACOs should use available levers for waste reduction, including Choosing Wisely materials, and implement strategies with proven efficacy in reducing low-value care to lower costs and increase the quality of health care.

Supplementary Material

Take-away points.

Collective risk-taking in financial contracts is the most influential determinant for ACOs in taking steps to reduce unnecessary care. Safety net ACOs are not likely to take steps such as educating physicians on low-value medical services and encouraging shared-decision-making. ACOs with less experience in risk-bearing likely may prioritizing overuse as they acquire more risk.

-

-

ACOs with little experience in risk-bearing and safety net ACOs should be specifically stimulated to reduce overuse with targeted advocacy efforts of healthcare payers and the Choosing Wisely campaign.

-

-

Research should focus on identifying efficient strategies for waste reduction with specific attention to audit-and-feedback mechanisms on overuse and underuse.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Commonwealth Fund (New York): grant 20160616, personal grants to M.H.H. and D.P. (Harkness fellows 2015-2016, M.H.H. sponsored by the Dutch Ministry of Health Welfare and Sport); and AHRQ: grant R01HS023812.

Footnotes

The authors rapport no potential conflict of interests

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is the pre-publication version of a manuscript that has been accepted for publication in The American Journal of Managed Care® (AJMC®). This version does not include post-acceptance editing and formatting. The editors and publisher of AJMC® are not responsible for the content or presentation of the prepublication version of the manuscript or any version that a third party derives from it. Readers who wish to access the definitive published version of this manuscript and any ancillary material related to it (eg, correspondence, corrections, editorials, etc) should go to www.ajmc.com or to the print issue in which the article appears. Those who cite this manuscript should cite the published version, as it is the official version of record.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Data 1.doc

Supplemental Data 2.ppt

Supplemental Data 3.ppt

References

- 1.Schwartz AL, Chernew ME, Landon BE, McWilliams JM. Changes in low-value services in year 1 of the Medicare pioneer accountable care organization program. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175(11):1815–1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nyweide DJ, Lee W, Cuerdon TT, et al. Association of pioneer accountable care organizations versus traditional Medicare fee for service with spending, utilization, and patient experience. JAMA 2015;313(21):2152–2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McWilliams JM, Chernew ME, Landon BE, Schwartz AL. Performance differences in year 1 of pioneer accountable care organizations. New Engl J Med 2015;372(20):1927–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelleher KJ, Cooper J, Deans K, et al. Cost saving and quality of care in a pediatric accountable care organization. Pediatrics 2015;135(3):e582–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Promoting conversations between providers and patients. Http://www.choosingwisely.org/ Accessed November 11, 2016.

- 6.Colla HC, Lewis VA, Shortell SM, Fischer ES. First national survey of ACOs finds that physicians are playing strong leadership and ownership roles. Health Aff 2014;33(6):964–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peiris D, Phipps-Taylor MC, Stachowski CA, et al. ACOs holding commercial contracts are larger and more efficient than noncommercial ACOs. Health Aff 2016;35(10):1849–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J. The elements of statistical learning Data mining, inference, and prediction. New York: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare&Medicaid Services. Medicare Shared Savings Program quality measure benchmarks for the 2014 reporting year. Baltimore (MD) Https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/downloads/MSSP-QM-Benchmarks.pdf Accessed November 11, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnett ML, Linder JA, Clark CR, Sommers BD. Low-value medical services in the safety-net population. JAMA Intern Med 2017;doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colla CH, Morden NE, Sequist TD, Schpero WL, Rosenthal MB. Choosing Wisely: prevalence and correlates of low-value health care services in the United States. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30(2):221–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schpero WL, Morden NE, Sequist TD, Rosenthal MB, Gottlieb DJ, Colla CH. For selected services, blacks and Hispanics more likely to receive low-value care than whites. Health Aff 2017;36(6):1065–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. State Health Facts. Medicaid enrollment by race/ethnicity, FY: 2011. http://kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-enrollment-by-raceethnicity/?currentTimeframe=0&selectedDistributions=white--black--hispanic--other--total Accessed January 13 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaPar DJ, Bhamidipati CM, Mery CM, et al. Primary payer status affects mortality for major surgical operations. Ann Surg 2010;252(3):544–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US healthcare. JAMA 2012; 307(14):1513–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colla CH, Mainor AJ, Hargreaves C, Sequist T, Morden N. Interventions aimed at reducing use of low-value health services: a systemic review. Med Care Res Rev 2016; 1–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. Effect of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention on broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing by primary care pediatricians: a randomized trial. JAMA 2013; 209(22):2345–2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stacey D, Legare F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;4:CD001431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bardach NS, Wang JJ, De Leon SF, et al. Effect of pay-for-performance incentives on quality of care in small practices with electronic health records: a randomized trial. JAMA 2013; 310(10):1051–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albright BB, Lewis VA, Ross JS, Colla CH. Preventive care quality of Medicare Accountable Care Organizations: Associations of organizational characteristics with performance. Med Care 2016;54(3):326–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu FM, Shortell SM, Lewis LA, Colla CH, Fischer EJ. Assessing differences between early and later adopters of Accountable Care Organizations using taxonomic analysis. Health Serv Res 2016;51(6):2318–2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider EC, Sarnak DO, Squires D, Shah A, Doty MM. Mirror mirror 2017: International comparison reflects flaws and opportunities for better U.S. healthcare. The Commonwealth Fund 2017 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.